Abstract

Many tree species show pronounced masting patterns, i.e. high inter-annual variability in seed production, which is strongly synchronised across large areas. Yet, when observing fructification intensity at the individual level, substantial intra-annual variability between trees becomes apparent. The drivers of this variability have so far been only investigated in studies of few species, individuals and/or over short time periods. In this study, we thus analysed potential predictors of individual fructification intensity for eight tree species common in central Europe (Fagus sylvatica, Quercus petraea/robur, Acer pseudoplatanus, Fraxinus excelsior, Picea abies, Abies alba, Pinus sylvestris, Pseudotsuga menziesii) across 15 years (2006–2020) and the area of Southern Germany. We utilised a comprehensive forest monitoring dataset, for which fructification intensity and crown condition are assessed visually each year for thousands of trees at fixed positions. Employing generalised additive models, fructification at the tree level was modelled best when considering predictors related to weather as well as tree age, crown condition and social position. The probability of (strong) fructification was higher in dominant trees, and did also increase as trees became older until a certain species-specific age had been reached, with the effect ultimately turning negative in very old trees. High crown defoliation had a negative effect on the probability of (strong) fructification in almost all species. Yet, in some species (e.g. Fagus sylvatica), weak crown defoliation had a positive effect on fructification intensity, potentially indicating different life strategies between species.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tree regeneration is a prerequisite for forest ecosystem functioning and development. The production of seeds is thus an essential part of the tree life cycle (Bazzaz et al. 2000) and a strong carbon sink (Seifert and Müller-Starck 2009; Mund et al. 2020). In temperate forests, many tree species show high inter-annual variability in seed production that is highly synchronised within and across populations — so-called mast seeding (Kelly and Sork 2002; Nussbaumer et al. 2016). This phenomenon has been at least partly attributed to the Moran effect, such that resource accumulation and pollination efficiency are linked to specific weather conditions, which are themselves spatially correlated (Koenig 2002; Pearse et al. 2016), although it has recently been shown that this effect varies between species (Bogdziewicz et al. 2023a). In Fagus sylvatica, a species showing particularly strong inter-annual variability and spatial synchrony in seed production, strong fructification has been linked to a sequence of weather patterns that is driven by the North Atlantic oscillation (Piovesan and Adams 2001; Vacchiano et al. 2017; Fernández-Martínez et al. 2017b; Ascoli et al. 2021; Bogdziewicz et al. 2021b), although with increasing temperatures due to climate change, this relationship became weaker and thus reduced synchrony between trees (Bogdziewicz et al. 2021a). The links between environmental cues and seed production are further complicated by the relationships potentially being non-linear in nature (Fernández-Martínez et al. 2017a). Further, while high inter-series correlations of seed production between individual trees and stands justify their aggregation at larger geographical scales (Vacchiano et al. 2017), intra-specific variability within years can still be rather high. For instance, a “mast year” has been defined as a year in which at least 50% of the trees within an observational plot show common or abundant fruiting (Nussbaumer et al. 2016). Thus, even if reproduction is synchronised across trees and stands over large distances, there is high intra-specific and intra-annual spatial variability at small scales (Gratzer et al. 2022). The few studies that have investigated potential underlying causes indicate that tree size (Seifert and Müller-Starck 2009; Davi et al. 2016; Minor and Kobe 2017; Hacket-Pain et al. 2019; Wion et al. 2023), age (Genet et al. 2009; Wion et al. 2023), crown transparency (Innes 1994; Davi et al. 2016; Oddou-Muratorio et al. 2021), competition (Minor and Kobe 2017; Wion et al. 2023), and site factors such as elevation (Davi et al. 2016) influence individual differences in fructification intensity. However, these studies were typically based on single species, short time periods and/or few individuals. Yet, the necessity to include such factors is emphasised by a study on the long-term changes of the proportion of seed-producing trees across the main tree species in Poland, which concluded that the observed increase was mainly driven by increasing stand age and not by changes in temperature and precipitation linked to climate change (Pesendorfer et al. 2020). These findings highlight the importance of considering tree and stand characteristics when investigating tree reproduction as well as its response to climate change (Hacket-Pain and Bogdziewicz 2021). Especially when flowering and fruiting intensity is to be accounted for in forest growth models (Vacchiano et al. 2018), knowledge on individual variability and its predictors are of great importance to increase the reliability of such models.

In this study, we aimed to find out if and how tree and site characteristics affect fructification intensity at the tree level. By considering trees across a large region (Southern Germany), we aimed to find general species-specific relationships for the most important tree species in central European forests, including species about which there is no broad knowledge on the drivers of fructification available yet. In addition, we aimed to find potential non-linear effects of tree- and site-related but also weather-related predictors.

Material

Data on fructification and tree characteristics

Annual data on fructification was provided by the forest research institutes of the German federal states of Baden-Wuerttemberg (Forstliche Versuchs- und Forschungsanstalt Baden-Wuerttemberg) and Bavaria (Bayerische Landesanstalt für Wald und Forstwirtschaft). These data were collected as part of the forest health monitoring and the monitoring of Level II plots within the ICP network and cover the larger area of Southern Germany. Each year in late July/early August, fructification intensity and crown status are assessed by observation teams according to a standardised procedure (Wellbrock et al. 2018; Eichhorn et al. 2020). Fructification is quantified based on a scale with four levels, and is classified according to the following criteria: Fructification is determined absent (0) if even the extensive observation of the crown with binoculars results in no signs of fructification, scarce (1) if there is sporadic fructification that is however not noticeable at first sight, common (2) if fructification is clearly visible to the naked eye and influences the appearance of the tree, and abundant (3) if fructification dominates the appearance of the tree (Eichhorn et al. 2020). For conifers it is important to note that only cones produced in the respective year are to be considered. Crown defoliation is assessed visually in 5% classes, so as to address needle and leaf loss. The procedure is constantly reconciled between the federal states to ensure common standards, and the observation teams are regularly trained accordingly to warrant comparability within and across states (Wellbrock et al. 2018).

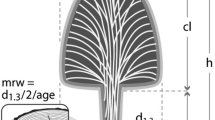

For each observed tree, information on its social position in the canopy (in classes dominant (1), co-dominant (2), intermediate (3)), age and geographic position are available. For our analysis, we took all observations for the species Fagus sylvatica, Quercus robur/Quercus petraea (pooled for analysis), Acer pseudoplatanus, Fraxinus excelsior, Picea abies, Abies alba, Pinus sylvestris, Pseudotsuga menziesii between 2006 and 2020 into account. Note that we use the term fructification for both broadleaved and coniferous trees throughout our study, thus referring to both fruits and cones, even though the latter are no fruits in a strict botanical sense.

Climate and site data

Monthly values of mean daily temperature and precipitation sum were obtained for each tree location based on gridded data (1 × 1 km) obtained from the German Weather Service (DWD Climate Data Center (CDC)). Information on available water capacity in the rooting zone was obtained as gridded geodata (NFKWe1000_250 V1.0, (c) BGR, Hannover, 2015).

Methods

Data cleaning and preparation

The annual observations provided for the years 2006–2020 in Bavaria and 2003–2020 in Baden-Wuerttemberg were first checked for missing observations and plausibility. Only records for which all required variables (cf. Table 1) were available were retained. If information on social position and age was missing for specific years, the data were filled based on the values available. For crown defoliation, the mean value of the three preceding years was calculated for each year so as to gain an estimate of crown status that is not dominated by inter-annual variability. To account for the inter-annual variability in fructification, the 1st order lagged value was obtained. This procedure resulted in at least 1372 observations of a minimum of 170 individual trees at at least 38 locations per tree species (Table 2). The species-specific fructifcation patterns in the observed period are shown in Fig. 1.

Selection and calculation of weather variables

In order to characterise average climatic site conditions, average mean daily temperature and precipitations sums were calculated for the vegetation period (March-August) and the time period 1981–2010. We reviewed the literature to identify the most important climatic variables for the prediction of fructification in our studied species. Accordingly, temperature and precipitation of the two previous summers (June, July, August) and the current spring (March, April, May) were selected. As the average climatic conditions cover a wide range for the observed trees (average mean daily temperature between March and August ranges from 6 to 15 °C, average precipitation sum from 315 to 1576 mm; 1981–2010) we calculated annual values as deviations from the long-term average (1981–2010). For temperature, this deviation was obtained by calculating the difference in °C, for precipitation it was obtained by division and is thus unitless (values > 1 represent more precipitation than average, values < 1 less than average).

Ordinal generalised additive modelling

For our study, an adequate modelling approach required the possibility to have an ordinal response variable to be able to address the ordinal fructification intensity records. It further required to include random effects due to repeated observations within the same tree, to include potentially non-linear effects and to account for potential spatial and temporal autocorrelation. Ordinal generalised additive models (GAMs) fulfill all these requirements (Wood 2017; Pedersen et al. 2019).

For each species, an ordinal GAM was constructed with fructification intensity as the response variable and the following predictors: Social status (SoSt) and fructification intensity of the previous year (FIt-1) as categorical variables, tree age (aget), mean crown defoliation in the three preceding years (CDt-1_3) and available water capacity (AWC) as smooth effects, as well as precipitation and temperature of June, July and August two years before (P-JJAt-2, T-JJAt-2), one year before (P-JJAt-1, T-JJAt-1) and in March, April and May of the current year (P-MAMt, T-MAMt) and long-term average precipitation and temperature (P-MAMJJAav, T-MAMJJAav) as a tensor product smooth each (Table 2). To account for further spatiotemporal variability, a tensor product smoothing spline of latitude and longitude (UTM) and year was included. Anisotropic smoothing splines were employed as variables differed in their scales. A random intercept for tree ID was included to account for repeated measurements on the same tree. For the variable year a cubic regression spline was used, for all other smoothing effects thin-plate splines were employed (Wood 2003; Eickenscheidt et al. 2019). The maximum number of basis dimensions (k) was set to 15 for the geographic coordinates to enable a good enough fit. For all other smoothing variables, models were first run with a low number of basis dimensions (k = 4) to prevent overfitting and erroneous oscillation of the splines and to increase interpretability by carving out generic patterns. The reasoning for this approach is that we expect the relationships to be either linear, exponential, logarithmic, sigmoidal or gaussian in shape (Fernández-Martínez et al. 2017a). We evaluated the choice of k based on the biological plausibility of the effect shapes on the one hand, and based on the model diagnostics of the basis dimensions. Especially, if the k index was < 1 and the p value for k as well as the difference between the effective degrees of freedom and k-1 low, we increased k to re-evaluate the fit of the predictor. Thus, for the predictors aget and the tensor product smooths of the temperature and precipitation variables, k was set to 5. So as to ensure that this choice in k did not lead to underfitting, we also ran each model with k = 10 for all predictors and visually compared the effects to those of the chosen model. Please see the supplementary material for a comparison of k diagnostics (Table S1) and the respective effect plots for each predictor (Figs. S1–S5). To further restrict the wigglyness of the smoothing splines, gamma was set to 1.4. We employed the double penalty approach to allow for an additional penalty in the null space (Marra and Wood 2011). We intentionally kept the number of predictors low so as to avoid concurvity. Still, an inspection of concurvity showed high values for some variables and species (e. g. for CDt-1_3 and aget as well as the deviation of temperature/precipitation of the preceding years). We thus ran the models without the strongly concurved predictors and compared the effects of the remaining predictors to those in the “full” model. As these did only differ marginally, we deemed the “full” model suitable and estimated effects plausible and valid despite concurvity. Finally, the residuals of each model were checked based on simulations for deviations from the expected distribution, spatial and temporal autocorrelation using package DHARMa in R (Hartig 2022; R Core Team 2023). In less than 2% of all trees, temporal autocorrelation was present in the residuals. As adding a correlation structure to the model did not result in any improvement, it was not incorporated into the model, which seemed justified based on the small share of trees with slightly autocorrelated residuals. All models were run with the function bam of the package mgcv in R (Wood 2011; R Core Team 2023).

Model comparison

In order to find out if tree and site characteristics are useful to explain the variability in fructification intensity, we compared the full model described above to a set of models with a limited number of predictors, thus retaining predictors for either only weather and tree, weather and site, weather, tree and site as well as a minimal model with lagged fructification intensity only (Table 3). For each model, we obtained the AIC to identify the best model.

Results

Model comparison and selection

For all species, the model with the lowest AIC was the one which includes predictors on weather and tree characteristics (Table 4). For this model, the deviance explained ranged from 22.76% in P. sylvestris to 48.34% in P. menziesii. For each species, the FIt-1 only model had the highest ΔAIC, followed by the models without weather-related predictors. The order concerning the models combining weather-, tree- and site-related predictors varied between species.

Based on the AIC, only the effects of the model with weather- and tree-related predictors were regarded further for all species. An overview of the model results is given in Table 5. In the ordinal models, the probability of each level of fructification intensity was estimated for each observation (Fig. 2). Especially for F. excelsior and P. sylvestris, high observed fructification intensity was underestimated by the model.

Visual comparison of observed and estimated fructification intensity based on the modelled probabilites in the selected models. Numbers represent the share (%, rounded to integers) of estimated fructification intensity levels (0–3) for each level of observed fructification intensity (each column sums to 100%)

Parametric effects of the selected models

Social status of the tree (SoSt)

In all of the investigated species, the probability of (high) fructification decreased with decreasing dominance of the tree in the canopy layer, although for Q. spp. and F. excelsior as well as for the intermediate class in P. menziesii, this effect was not significant at p < 0.05 (compared to reference level of dominant class). The effect of decreasing probability in trees of lower social status was especially prominent in F. sylvatica, P. abies and A. alba, and particularly for intermediate trees, while the difference between dominant and co-dominant trees was less pronounced (Table 5).

Fructification intensity in the previous year (FIt-1)

In F. sylvatica, P. abies, A. alba and P. menziesii, fructification of any intensity (i. e. scarce, common or abundant) in the previous year significantly lowered the probability of (strong) fructification in the current year, with the decrease being almost linear on the linear predictor scale with increasing intensity in the previous year. In Q. spp. and A. pseudoplatanus, only common and abundant fructification in the previous year induced such a negative effect, while for F. excelsior, the negative effect was only significant for scarce fructification. Contrary to all the other species, there was a positive effect of scarce and common fructification intensity in the previous year in P. sylvestris (Table 5).

Smooth effects of the selected model

Tree age (aget)

In all of the investigated tree species, the effect of tree age on fructification intensity was clearly non-linear on the linear predictor scale and often showed a plateau or turning point. There first was a more or less steep increase from the juvenile stage to an age of ~ 75 to 100 years, depending on the species. Then, the curve flattened and turned into a negative effect in most species, with the age related to this change in direction and the slope varying between species. The threshold between the fructification intensity of “none” to “scarce” is at -1 (dashed horizontal line in Fig. 3), such that the age associated with this threshold can be regarded as the age of maturity, i.e. the age at which fructification or coning occurred for the first time. This age corresponded to ~ 40 to 50 years in F. sylvatica, A. pseudoplatanus, P. abies, A. alba and P. menziesii, and to ~ 25 years in Q. spp., F. excelsior and P. sylvestris.

Mean crown defoliation in the three preceding years (CDt-1_3)

In all species except A. pseudoplatanus the effect of mean crown defoliation in the preceding years was significant, and in all those species except for P. menziesii, this effect was non-linear. In F. sylvatica, Q. spp., P. abies and A. alba, the model showed a positive effect of increasing crown defoliation until reaching values around ~ 30–40%, from when on the effect turned negative. In P. menziesii, the effect was negative throughout the whole range of values for crown defoliation, while in F. excelsior and P. sylvestris, this negative effect only set in at values around 25% (Fig. 4).

Temperature and precipitation in June, July and August of t-2 (P/T-JJAt-2)

The combined effect of temperature and precipitation (introduced as a tensor product smoother in the model) of June, July and August two years before the observation is shown in Fig. 5. Brown colours show a positive effect on the probability of (strong) fructification while green colours depict a negative effect, the colour intensity corresponding to the strength of the effect. The pattern looks roughly similar for F. sylvatica, Q. spp. and P. abies. Temperatures much higher than average had a negative effect, while low temperatures had a positive effect, mostly regardless of precipitation. This pattern was overall similar in A. pseudoplatanus, P. sylvestris and P. menziesii, and to some extent also in A. alba, although here, the effect was generally less strong. In F. excelsior, especially a combination of lower than average precipitation and slightly higher than average temperatures showed a positive effect.

Temperature and precipitation in June, July and August of t-1 (P/T-JJAt-1)

For summer weather in the preceding year, the patterns looked less clear within species and also less coherent between species. The effect occurred to be strongest in F. sylvatica, with a particularly positive effect of substantially higher than average temperatures, which were mostly accompanied by lower than average precipitation. Such positive effect of presumed drought conditions was also observed to some extent in A. pseudoplatanus, A. alba as well as in P. sylvestris, even though especially in the latter species, high temperatures had a positive effect regardless of precipitation. In contrast, such conditions had a negative effect in P. abies, for which only a small set of combinations of temperature and precipitation appeared positive. In Q. spp., especially higher than average precipitation had a positive effect, as was the case for F. excelsior, when accompanied by high temperatures. In P. menziesii, both high temperatures and average precipitation as well as high precipitation and low temperature had a positive effect (Fig. 6).

Temperature and precipitation in March, April and May (P/T-MAMt)

The effects of spring weather were equally strong in F. sylvatica, Q. spp. and P. abies and also showed a similar pattern between these species — higher than average temperature in March, April and May had a positive effect, regardless of precipitation. Though less strong, the effect was similar in A. pseudoplatanus. On the contrary, in F. excelsior, especially cold and wet spring weather had a positive effect, while in A. alba, especially warm and dry spring weather had a positive effect. In P. sylvestris and P. menziesii, specific combinations of temperature and precipitation had positive effects. In P. menziesii, a negative effect was associated with both very high and very low temperature (as long as precipitation was not higher than average), while in P. sylvestris, both average temperature conditions and warm and dry spring had a positive effect (Fig. 7).

Partial effect of the tensor product smooth of temperature and precipitation deviation from long-term (1981–2010) means in March, April and May of the current year t. Brown colours indicate a positive effect, green colours a negative effect with the strength of the effect indicated by colour intensity

Discussion

Model comparison

First of all, our aim was to compare different sets of models to find out if tree and/or site characteristics are valuable predictors for fructification intensity, especially compared to or in combination with weather-related variables, which are known to be important predictors. For all species, excluding available water capacity and average climate resulted in better models according to AIC, when (lagged) weather conditions and tree characteristics were included, indicating that these site-related variables are negligible. Similarly, variables related to water holding capacity but also soil nutrition and other site and stand characteristics were not selected in a random forest approach by Lebourgeois et al. (2018) as predictors of fructification intensity in F. sylvatica and Q. spp. in France. Instead, the mentioned study concluded that temperature plays an essential role in pollen load and thus in fruit production, which fits with a number of studies that clearly show the dominant role of environmental cues for fructification (Selås et al. 2002; Pearse et al. 2016; Vacchiano et al. 2017; Fernández-Martínez et al. 2017b; Nussbaumer et al. 2018). As expected, our models including lagged fructification intensity as the only predictor, performed worst for all species. Yet, between 13 and 33% of deviance were explained with this simple model, with particularly high values in P. menziesii, F. sylvatica and A. pseudoplatanus, which showed both high intra-specific synchrony and a strong almost biennial pattern (Fig. 1). While explained deviance of the models including weather- and tree-related predictors was similar to that of the models with weather- and site-related predictors, the former were favoured in terms of AIC, presumably due to the complexity of the tensor product smooth of long-term averages of precipitation and temperature.

Comparing the explained deviance of our selected models between species shows that, with the exception of P. menziesii, which had the highest value overall (48%), the angiosperm species reached higher values than the gymnosperms. Similarly to our study, models for F. sylvatica generally yielded relatively high measures of goodness of fit, which were also higher than those for Q. spp. in previous studies (Lebourgeois et al. 2018; Nussbaumer et al. 2018), even though the differences reported previously were larger than in our study, in which deviance explained for oak in the chosen model was still 35%. Also similarly as reported by Nussbaumer et al. (2018) for Germany (but at stand level), deviance explained in our study was higher in P. abies than in P. sylvestris, which had the lowest value (23%) overall. These comparisons show that predictability of fructification intensity differs between species, and that these differences are not solely due to our statistical approach or selection of predictors as the aforementioned studies employing different methods and other/additional predictors came to similar conclusions. Thus, the largest share of variance remains unexplained and the underlying factors of tree-individual fructification require further study, especially considering differences between species.

Effects of weather on fructification intensity

A multitude of studies found a great number of environmental predictors for fructification intensity, mostly concerned with masting at the population or species level based on data aggregated over large areas (e.g. Vacchiano et al. 2017; Fernández-Martínez et al. 2017b; Nussbaumer et al. 2018; Bogdziewicz et al. 2021b). Our aim with this study was thus not to identify the “best” weather-related predictors but to include the most common environmental cues so as to account for the large effect of weather on seed production, and to consider these as non-linear smooth effects (Fernández-Martínez et al. 2017a). In addition, we looked at tensor product smoothers of temperature and precipitation deviation in order to be able to determine singular effects of either variable as well as joint effects, particularly drought. The results show that this approach gives valuable insight into the complex non-linear patterns of weather conditions and especially into potential optima of precipitation and temperature for a high probability of (strong) fructification. Yet, combining this approach with a larger set of predictors seems necessary, especially also considering late frost events, which was not possible due to lack of data in the present study.

Deviation from precipitation sum/mean temperature JJAt-2 (P/T-JJAt-2)

It has been reasoned that the weather conditions in the vegetation period two years before flowering play an essential part as favourable conditions support the uptake of nutrients necessary for reproduction (Mund et al. 2020). In our study, there was a negative effect of the mean summer temperature in the year before the previous year on fructification intensity in all species except F. excelsior. This was true regardless of the deviation of precipitation from the long-term mean. Such a negative effect of rather hot summer conditions has already been observed in F. sylvatica (Vacchiano et al. 2017), Q. robur and Q. petraea (Nussbaumer et al. 2018) as well as P. abies (Selås et al. 2002; Nussbaumer et al. 2018). For F. sylvatica, a positive effect of summer precipitation t-2 has been observed as well (Vacchiano et al. 2017; Nussbaumer et al. 2018; Mund et al. 2020), which was only partly confirmed in our analysis as high precipitation had a positive effect if temperature was not too high but lower than average precipitation could also have a positive effect if temperatures were slightly higher than average, i.e. under presumably dry conditions, which is partly contradictory. This is, however, in line with the results of a study carried out in individual trees in Northern Germany (Müller-Haubold et al. 2015), underlining that the response of beech to certain weather cues two years before fructification is not entirely uniform, especially when considering individual trees. For P. sylvestris, we also found a positive effect of high precipitation in JJAt-2 as has previously been reported (Nussbaumer et al. 2018), however this effect was strongest when accompanied by lower than average temperatures.

Deviation from precipitation sum/mean temperature JJAt-1 (P/T-JJAt-1)

F. sylvatica overall showed the strongest effect of the interaction of the deviation of precipitation and temperature in JJA in the previous year. High temperatures (and low precipitation) had a positive effect while low temperatures, especially in combination with high precipitation, had a negative effect, which is in accordance with various studies showing a positive effect of summer drought (Piovesan and Adams 2001; Mund et al. 2020) as linked to NAO phases (Ascoli et al. 2021), and specifically a negative effect of summer precipitation (Müller-Haubold et al. 2015; Nussbaumer et al. 2018) and positive effect of summer temperature (Müller-Haubold et al. 2015; Vacchiano et al. 2017; Bogdziewicz et al. 2019). In contrast, the effect on fructification intensity was very weak and less distinct in oak, which is in accordance with a previous study that did not find significant effects for Q. robur and Q. petraea (Nussbaumer et al. 2018). We can also confirm the positive effect of summer temperature found for P. abies (Selås et al. 2002; Nussbaumer et al. 2018), especially in combination with low precipitation. While no significant effects of previous summer weather have been reported for P. sylvestris (Nussbaumer et al. 2018), we did find a clearly positive effect of high temperatures, regardless of precipitation. Such effect was also present in A. pseudoplatanus, for which no previous studies are available to our knowledge. Higher temperatures also had a mostly positive effect in A. alba and P. menziesii but depending on precipitation this effect turned negative, just as for F. excelsior, where distinct combinations of temperature and precipitation had negative or positive effects that are difficult to generalise. In F. excelsior, the share of trees producing seeds has been found to be higher the lower the temperature of the previous summer, even though the relation was only weak and not significant (Tapper 1992), which is similar to the effect of temperature we found if precipitation in the same time period was low but contradicts the positive effect of summer temperature we found when precipitation was around average or slightly higher.

Deviation from precipitation sum/mean temperature MAMt (P/T-MMAt)

For F. sylvatica, Q. spp. and to a lesser extent A. pseudoplatanus and P. abies, a strong positive effect of high temperature in spring was visible, largely independent of concomitant precipitation levels, which is in accordance with previous studies on oak (Journé et al. 2021), beech (Nussbaumer et al. 2018) and spruce (Nussbaumer et al. 2018). High temperature in the period after the start of pollen emission (April) has been associated with higher fruit biomass in Q. spp., with a particularly non-linear effect and specific temperature thresholds (Lebourgeois et al. 2018). For Q. petraea, the correlation of seed production with spring temperature was particularly strong at colder sites, indicating that in this “fruit masting” species (opposed to “flower masting” species such as F. sylvatica), pollination success is largely driven by high spring temperature, which enables synchronised flowering particularly at colder sites (Bogdziewicz et al. 2019).

Concerning precipitation, especially very low values (i. e. large negative deviations from the long-term average) had a negative effect on fructification intensity in F. sylvatica, Q. spp., A. pseudoplatanus, P. abies, and P. menziesii, which confirms previous findings for F. sylvatica (Müller-Haubold et al. 2015; Mund et al. 2020) but contradicts findings for F. sylvatica by Nussbaumer et al. (2018). High precipitation is assumed to impede pollen dispersal in spring (Ascoli et al. 2021), yet a clear negative effect of high precipitation in spring is not visible but rather the opposite, especially for F. sylvatica, A. pseudoplatanus, F. excelsior, P. sylvestris and P. menziesii, though depending on temperature. Presumably, negative effects of precipitation on pollen dispersal become visible at finer time scales and potentially also regard the frequency of precipitation events (within the time period of pollen dispersal) rather than the overall precipitation amount (relative to long-term sums), so that this effect may not be possible to show through our approach. In P. sylvestris, the overall response to spring weather was very diverse, with positive effects related to distinct combinations of temperature and precipitation, which is likely reflected in the lack of significant effects of spring weather found by Nussbaumer et al. (2018).

Effects of tree characteristics on fructification intensity

Social status of the tree (SoSt)

Within a stand, the social position of each tree reflects differences in stem diameter and overall above- and belowground biomass but, directly related, also differences in the level of competition and resource availability. When interpreting the effect of the social status it is thus important to consider both of these factors.

In all of the investigated species, apart from Q. spp. and F. excelsior, the social position of a tree had a significant effect, such that the probability of (strong) fructification was highest in dominant trees and then decreased for co-dominant and intermediate trees (with the exception of P. menziesii, for which there was only a significant decrease for co-dominant but not intermediate trees compared to the reference level of dominant trees). A close relation between tree diameter and fruit production has also been found for a range of tree species in North America (Minor and Kobe 2017; Wion et al. 2023), as well as A. alba in Southeast France (Davi et al. 2016). Seifert and Müller-Starck (2009) reported that the larger tree diameter classes produced consistently more cones in P. abies in a German study at individual tree level. Such strong variability in fruit production within stands has been explained with the existence of “super-producers”, such that few trees within a population are responsible for a high proportion of the overall amount of seeds produced, which has been found in various angiosperms in North America (Minor and Kobe 2017) as well as in P. abies in Northern Italy (Hacket-Pain et al. 2019). The ability of these large trees to consistently produce high amounts of seeds may be explained by having high soil nutrient availability and little competition, even though these factors did not affect seed production in trees that were no “super-producers” (Minor and Kobe 2017). In Rocky Mountain ponderosa pine, seed production was highest in open-grown trees (Wion et al. 2023), underlining the role of competition. Further, it has generally been found that in stands with high nutrient availability, fructification intensity and frequency is higher and a larger share of the gross primary production (GPP) is devoted to fruit net primary production (NPP; Fernández-Martínez et al. 2017c), and this relation may also be transferable to individual trees to some extent. In F. sylvatica, larger trees also showed earlier reproductive phenology, which was linked to a higher amount of flowers and fruits produced (Westergren et al. 2023). Dominant trees in the upper canopy layer receiving more light may thus give them an advantage connected to earlier budburst, as in shaded seedlings of F. sylvatica, Q. robur and F. excelsior budburst in spring occurred later than in seedlings receiving full sun (Vitasse et al. 2021). Yet, a recent study has shown that the intensity of seed production cannot be directly translated into fecundity as pollination efficiency has been observed to decrease with increasing diameter, especially within the last decade (Bogdziewicz et al. 2023b). Still, in F. sylvatica, the 10% of the trees with the lowest competition or highest stem diameter were associated with 27% and 36%, respectively, of the total female fecundity (Oddou-Muratorio et al. 2021), indicating that large, dominant trees are strong drivers of tree regeneration. Further, the degree of inter-annual variability and between-tree synchrony also seems to be linked to tree size (Wion et al. 2023), which highlights the role of stand composition with regard to the overarching reproduction strategies (e. g. pollination efficiency, predator satiation, economies of scale; Kelly and Sork 2002; Pearse et al. 2016). In F. excelsior, we did not find a significant effect of social status on fructification intensity, which adds to findings from Sweden, where fruiting frequency did not differ between large trees and trees with a diameter of less than 20 cm, indicating an overall small effect of tree size on fruiting activity in this species (Tapper 1992).

Tree age (aget)

Tree age is an important factor as trees only produce seeds once they have reached maturity. As our dataset contains a wide range of ages, including the juvenile stage, we can infer the age of maturity from the first cut point (at y = -1) estimated by the model that marks the age where the transition from the level of “no fructification” to “scarce fructification” occurs. This threshold is reached at ~ 25 years in Q. spp., F. excelsior and P. sylvestris, ~ 40 years in F. sylvatica, A. pseudoplatanus, P. abies and A. alba and ~ 50 years in P. menziesii, which is roughly in line — though slightly earlier, especially for Q. spp. — with general numbers given in the literature (Schütt et al. 2002). The positive effect on the probability of (strong) fructification steeply increases until the age of ~ 80 years in most of the investigated species (~ 100 years for P. menziesii), followed by a flattening of the curve and a negative effect starting from ages ~ 100–200 years, depending on the species. In F. sylvatica, this generally matches previous findings of trees first investing into reproduction at 58 years and absolute and relative investment into seed biomass increasing with stand age (Genet et al. 2009). This effect was also shown indirectly as stem diameter growth was most strongly correlated to the maximum temperature of July in the year before fructification in older F. sylvatica trees, as these presumably invested more into seed production (Hacket-Pain et al. 2015). Higher cone production in older trees was also observed in Rocky Mountain ponderosa pine, concomitant with lower inter-annual variability and lower between-tree synchrony (Wion et al. 2023). In P. abies, the positive effect of age on female fecundity peaked around an age of 160 years and then became negative (Avanzi et al. 2020), as older (larger/taller) trees in wind-pollinated species seem to invest more into male than female flowers (Burd and Allen 1988; Fox 1993). As the visual inspection of cones is the basis in or study, a decrease in female flowers would become apparent as reduced fructification intensity. A similar effect has been found for fecundity in relation to tree size in North America, where the positive relation turned negative once a certain tree diameter had been reached (Clark et al. 2021). Our study reveals that the age effect can be split into three phases across species: (1) Once maturity has been reached, there is a steep increase in fructification intensity in the following decades, before (2) the effect reaches a plateau where any further ageing hardly plays a role and then (3) turns negative as a species-specific age has been reached. Considering this ontogenetic process in studies of fructification is necessary, as shown by Pesendorfer et al. (2020), who found that an increase in the proportion of seed-producing trees over the recent decades can mostly be attributed to the increasing stand age of the investigated trees. Likewise, any potential decline associated with further aging would also have to be accounted for, as well as general stand dynamics if fructification/masting intensity is aggregated at larger scales.

Mean crown defoliation in the three preceding years (CDt-1_3)

Crown density and fructification are strongly related, and those relations have different directions of cause and effect. Especially in beech, higher fruit production is known to be concomitant with lower leaf area index/leaf biomass (Müller-Haubold et al. 2013; Mund et al. 2020; Stolz et al. 2023), resulting at least to a certain extent from the replacement of leaf buds with fruit buds (Innes 1994). Due to both fructification and crown defoliation being highly temporally autocorrelated (Seidling et al. 2012; Nussbaumer et al. 2018) as well as inter-related (Müller-Haubold et al. 2013; Nussbaumer et al. 2018; Mund et al. 2020), it is difficult to fully disentangle cause and effect. In general, partial crown defoliation is regarded as an unspecific indicator of tree condition that integrates a wide range of abiotic and biotic factors that are however difficult to fully discern (Bussotti et al. 2024). Based on our dataset, we were thus not able to infer the causes of defoliation and only inferred to its degree as a predictor for fructification without considering concomitant mechanisms, where a cause of defoliation may also directly affect fructification. By averaging the assessment of the preceding three years we aimed at getting an image of overall crown status not directly linked to causes for inter-annual variability. In all studied species except A. pseudoplatanus, crown defoliation had a significant effect on the probability of (strong) fructification. Three different effect patterns emerged: (1) A linear effect: P. menziesii was the only species to show a linear effect, such that an increase in crown defoliation went along with a decreasing probability for (strong) fructification. In a study on cone production and tree-ring width, P. menziesii showed a strong negative relation, which indicates a “resource-switching” strategy that relies on currently assimilated carbon for cone production (Eis et al. 1965). In combination, even slight defoliation may lead to a shift in priorities for resource allocation away from reproduction. (2) A non-linear, monotonically decreasing effect: A mostly negative effect of crown defoliation but with different slopes at different degrees of crown defoliation was visible for F. excelsior and P. sylvestris. In these two species, the negative effect was particularly strong once defoliation reached ~ 25 to 30% and then flattened again once levels of ~ 65% were reached. The underlying mechanisms are probably similar to those observed in P. menziesii, although the effect is only apparent once crown defoliation has reached a certain threshold, thus indicating a higher priority of reproduction despite slightly declining crown condition, or defoliation not being concomitant with a (substantial) resource limitation that may induce the need for a trade-off. (3) An optimum curve: In F. sylvatica, and to a lesser extent in Q. spp., P. abies and A. alba, the probability of (strong) fructification at first increased with increasing defoliation and the effect only turned negative once a certain threshold of 30–35% defoliation had been reached. In these species, declining crown status could thus trigger a shift in priority to reproduction. Similarly, at two sites in Southeast France, A. alba trees with crown defoliation rates between 15–30% and 30–45%, respectively, showed the highest cone production (Davi et al. 2016); While in this mentioned study crown defoliation and cone production were assessed in the same respective years, such that cause and effect cannot be entirely disentangled, assuming a certain temporal autocorrelation in the crown status of coniferous trees such as A. alba, these results match very well with the “optimum” observed in our study. Similar results have been reported from monitoring masting activity and crown condition in England, where fruit production in beech trees in a pronounced masting year was lower in those trees for which more than 30% crown defoliation had been recorded in the preceding year (Innes 1994). In a range of deciduous and coniferous tree-species in France, a significant reduction in basal area increment has been observed at defoliation rates around 15–30% (Ferretti et al. 2021), indicating that vegetative growth is also affected once a certain threshold of defoliation has been reached. Moreover, across species, an exponential increase in tree mortality has been found in trees in which crown defoliation in the previous year exceeded 20% (Dobbertin and Brang 2001). Thus, if increasing crown defoliation can be regarded as an indicator of decreasing vitality, the concept of “fight or flight” (Lauder et al. 2019) could come into play, where stressed trees either invest more in growth and defence (“fight”) or more into reproduction to secure regeneration rather than survival of a particular individual (“flight”). It has been observed in both beech and spruce that drought-stressed trees showed a substantial growth decline but higher relative share of carbon allocated to reproduction than non-stressed trees (Hesse et al. 2021), indicating a potential “flight” strategy under stress. German foresters coined the term “Angstfruktifikation” for this phenomenon, meaning that substantially stressed trees will increase fructification and coning in anticipation of potential mortality. Thus, an increase in crown defoliation, if indicator of increased “stress” of some kind, may trigger such “flight” behaviour in beech, oak, spruce and fir, with an increase in fructification intensity. While studies on the effect of defoliation on fructification are scarce, a study of beech in the Pyrenees revealed complex interactions between crown condition, tree size, growth level, competition and female fecundity (Oddou-Muratorio et al. 2021). While, concomitant with our findings, there was an overall negative effect of defoliation on female fecundity, a trade-off between growth and female fecundity that depended on defoliation was found, i.e. in non-defoliated trees there was a positive correlation, in defoliated trees a negative correlation between growth and female fecundity, which implies a resource limitation in the latter (Oddou-Muratorio et al. 2021). In order to test how resource-switching and flight-or-fight-mechanisms are part of our results, further investigations incorporating growth levels, fructification intensity and crown condition at the individual scale but over large datasets are necessary. However, our results indicate that crown condition might explain intra-specific differences in fructification intensity to some degree, and that the effect of defoliation on fructification intensity is species-specific.

Different fructification strategies between species

Species with a high inter-annual variability in seed crop can generally be divided into those species, in which the variability in flower production is high (“flower masting”) and those species, in which a rather constant amount of flowers is produced each year but pollination and seed maturation have large variability (“fruit maturation masting”; Pearse et al. (2016)). However, it has recently been shown that female flowering intensity is highly variable between years in Q. spp., which has previously been regarded as a species with a fruit maturation masting strategy (Fleurot et al. 2023). As our data on fruit abundance were based on observations in late July/early August, we were not able to differentiate between the abundance of flowers and the abundance of fruit but can only assess effects on the latter. Further, species are categorised based on their resource dynamics: If a “resource-matching” strategy is employed, it is assumed that conditions are favourable for both growth and reproduction, resulting in high seed production and primary/secondary growth. On the other hand, in species with a “resource-switching” strategy, in a year with good conditions for reproduction, generative growth is prioritised over vegetative growth, which shows as a trade-off (Kelly and Sork 2002; Nussbaumer et al. 2021). Strong negative autocorrelation of fructification is an indicator of resource-switching (Kelly and Sork 2002), especially seen in F. sylvatica, P. abies, A. alba and P. menziesii in our study, where the effect of increasing fructification intensity of the previous year almost linearly decreased the probability of (strong) fructification in the current year. This has also been found in individual P. abies trees in Bavaria, especially in the particularly dry year 2003, emphasising the role of resource limitation as well as the strict prioritisation of generative over vegetative growth (Seifert and Müller-Starck 2009). Concerning P. menziesii, our findings do however contradict those for this species from various European, mainly French, sites, where autocorrelation (lag = 1) was almost zero, and also smaller in P. abies and A. alba than in F. sylvatica (Fernández-Martínez et al. 2017c).

In contrast to abovementioned species, Q. spp. is regarded to employ a resource-matching strategy, evidenced by a positive correlation between fruit production and stem diameter growth (Lebourgeois et al. 2018), which indicates that there is no general resource limitation. This is contradicted by recent findings of Nussbaumer et al. (2021), who found that resource depletion did occur in the year succeeding a mast event. This also matches our finding of common or abundant fructification decreasing the probability of (strong) fructification in the following year. However, we found this effect to be much weaker than for the abovementioned species, and also overall no strong pattern of inter-annual variability or intra-specific synchrony (Fig. 1), which may indicate that presumed resource-matching results in rather individual patterns, which would also explain the comparably low model performance in our and previous studies (Lebourgeois et al. 2018; Nussbaumer et al. 2018). It has recently been shown that flowering intensity and synchrony affect fructification intensity in Q. petraea, and that these relations are influenced by the climatic conditions of the populations studied, indicating complex and diverse mechanisms of masting in oak (Fleurot et al. 2023). The effect of previous years’ fructification intensity in Q. spp. is similar to the one we observed in A. pseudoplatanus, and given that the seeds of this species are comparably light, it can be assumed that resource depletion is not as substantial as in other species with high fruit costs, even though we are not aware of any related studies with regard to A. pseudoplatanus. Contrary to oak, this species however showed an almost biennial pattern and very high intra-annual synchrony, which indicates that there must be strong endo- or exogenous cues to fruit production in this species, as is supported by the relatively high explained deviance of the selected model. In F. excelsior, which also produces rather light seeds, the effect of previous year’s fructification intensity is only significant if it was scarce, which also seems difficult to explain. Overall, modelled fructification intensity was underestimated in this species (Fig. 2), indicating that fructification in this species must be influenced by factors other than those we were able to consider. Yet, the pattern found for F. excelsior is consistent with results from Sweden, where most of the studied trees showed fructification in consecutive years, and fructification in one year increased the probability for fructification in the succeeding year (Tapper 1992). The effect of previous year’s fructification intensity stood out entirely in P. sylvestris, which is consistent with the results of previous studies (Bisi et al. 2016; Nussbaumer et al. 2018). This could partly stem from difficulties in assessing current year’s seeds in this species, in which cone development takes places over two growing seasons. Yet, a positive effect of previous year’s intensity has also been reported based on observations of flowering (Meng et al. 2022). The lack of a clear (negative) effect of the fructification intensity of the previous year is particular surprising when considering that in P. sylvestris a relatively large share of GPP is devoted to fruit NPP (Fernández-Martínez et al. 2017c). This may be part of the reproductive strategy of P. sylvestris as a pioneer species — similar as in A. pseudoplatanus and F. excelsior, which can also show pioneer character — in contrast to late-successional species such as F. sylvatica, A. alba or P. menziesii, which is then also connected to the early age of maturity reached in P. sylvestris and F. excelsior.

Conclusion

For all species, fructification at the tree level was modelled best when considering predictors related to weather and tree-related variables, and including these tree-related characteristics did increase the explained deviance of the models, with the degree varying between species. This shows that, while weather is the main cue for fructification (extrinsic effect), the response to these cues is mediated by factors such as social position in the canopy, tree age and crown status (intrinsic effects). Thus, when aggregating fructification at coarser scales, or comparing fructification intensity and strategies within and across species or time periods, differences in stand composition and tree condition should be taken into account. Eventually, while the assessment of fructification intensity at the tree level provides important information about the drivers of reproduction in trees, further factors influence how this translates into fecundity and regeneration at the stand level. Thus, concerning forest stand dynamics, analysing the individual and common drivers of fructification is only the first step.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Code availability

Code is not publicly available.

References

Ascoli D, Hacket-Pain A, Pearse IS et al (2021) Modes of climate variability bridge proximate and evolutionary mechanisms of masting. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2020.0380

Avanzi C, Heer K, Büntgen U et al (2020) Individual reproductive success in Norway spruce natural populations depends on growth rate, age and sensitivity to temperature. Heredity (Edinb) 124:685–698. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41437-020-0305-0

Bazzaz FA, Ackerly DD, Reekie EG (2000) Reproductive allocation in plants. In: Fenner M (ed) Seeds: the ecology of regeneration in plant communities, 2nd edn. CAB International, Oxford, pp 1–29

Bisi F, von Hardenberg J, Bertolino S et al (2016) Current and future conifer seed production in the Alps: testing weather factors as cues behind masting. Eur J for Res 135:743–754. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10342-016-0969-4

Bogdziewicz M, Szymkowiak J, Fernández-Martínez M et al (2019) The effects of local climate on the correlation between weather and seed production differ in two species with contrasting masting habit. Agric for Meteorol 268:109–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2019.01.016

Bogdziewicz M, Hacket-Pain A, Kelly D et al (2021a) Climate warming causes mast seeding to break down by reducing sensitivity to weather cues. Glob Chang Biol 27:1952–1961. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.15560

Bogdziewicz M, Hacket-Pain A, Ascoli D, Szymkowiak J (2021b) Environmental variation drives continental-scale synchrony of European beech reproduction. Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.3384

Bogdziewicz M, Journé V, Hacket-Pain A, Szymkowiak J (2023a) Mechanisms driving interspecific variation in regional synchrony of trees reproduction. Ecol Lett 26:754–764. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.14187

Bogdziewicz M, Kelly D, Tanentzap AJ et al (2023b) Reproductive collapse in European beech results from declining pollination efficiency in large trees. Glob Chang Biol 29:4595–4604. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.16730

Burd M, Allen TFH (1988) Sexual allocation strategy in wind-pollinated plants. Evolution (n Y) 42:403–407. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1558-5646.1988.tb04145.x

Bussotti F, Potočić N, Timmermann V et al (2024) Tree crown defoliation in forest monitoring: concepts, findings, and new perspectives for a physiological approach in the face of climate change. For an Int J for Res. https://doi.org/10.1093/forestry/cpad066

Clark JS, Andrus R, Aubry-Kientz M et al (2021) Continent-wide tree fecundity driven by indirect climate effects. Nat Commun 12:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-20836-3

DWD Climate Data Center (CDC) Raster der Monatssumme der Niederschlagshöhe für Deutschland, Version v1.0

DWD Climate Data Center (CDC) Raster der Monatsmittel der Lufttemperatur (2m) für Deutschland, Versionv1.0.

Davi H, Cailleret M, Restoux G et al (2016) Disentangling the factors driving tree reproduction. Ecosphere 7:1–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.1389

Dobbertin M, Brang P (2001) Crown defoliation improves tree mortality models. For Ecol Manage 141:271–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-1127(00)00335-2

Eichhorn J, Roskams P, Potočić N, et al (2020) Part IV: visual assessment of crown condition and damaging agents. In: Centre UIFPC (ed) Manual on methods and criteria for harmonized sampling, assessment, monitoring and analysis of the effects of air pollution on forests. Thünen Institute of Forest Ecosystems, Eberswalde, p 55

Eickenscheidt N, Augustin NH, Wellbrock N (2019) Spatio-temporal modelling of forest monitoring data: modelling German tree defoliation data collected between 1989 and 2015 for trend estimation and survey grid examination using GAMMs. Iforest 12:338–348. https://doi.org/10.3832/ifor2932-012

Eis S, Garman EH, Ebell LF (1965) Relation between cone production and diameter increment of Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii (Mirb.) Franco), Grand fir (Abies grandis (Dougl.) Lindl.), and Western white pine (Pinus monticola Dougl.). Can J Bot 43:1553–1559. https://doi.org/10.1139/b65-165

Fernández-Martínez M, Bogdziewicz M, Espelta JM, Peñuelas J (2017a) Nature beyond linearity: meteorological variability and Jensen’s inequality can explain mast seeding behavior. Front Ecol Evol 5:1–8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2017.00134

Fernández-Martínez M, Vicca S, Janssens IA et al (2017b) The North Atlantic Oscillation synchronises fruit production in western European forests. Ecography 40:864–874. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.02296. (Cop)

Fernández-Martínez M, Vicca S, Janssens IA et al (2017c) The role of nutrients, productivity and climate in determining tree fruit production in European forests. New Phytol 213:669–679. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.14193

Ferretti M, Bacaro G, Brunialti G et al (2021) Tree canopy defoliation can reveal growth decline in mid-latitude temperate forests. Ecol Indic. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2021.107749

Fleurot E, Lobry JR, Boulanger V et al (2023) Oak masting drivers vary between populations depending on their climatic environments. Curr Biol 33:1117-1124.e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2023.01.034

Fox JF (1993) Size and sex allocation in monoecious woody plants. Oecologia 94:110–113. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00317310

Genet H, Bréda N, Dufrêne E (2009) Age-related variation in carbon allocation at tree and stand scales in beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) and sessile oak (Quercus petraea (Matt.) Liebl.) using a chronosequence approach. Tree Physiol 30:177–192. https://doi.org/10.1093/treephys/tpp105

Gratzer G, Pesendorfer MB, Sachser F et al (2022) Does fine scale spatiotemporal variation in seed rain translate into plant population structure? Oikos. https://doi.org/10.1111/oik.08826

Hacket-Pain A, Bogdziewicz M (2021) Climate change and plant reproduction: trends and drivers of mast seeding change. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2020.0379

Hacket-Pain AJ, Friend AD, Lageard JGA, Thomas PA (2015) The influence of masting phenomenon on growth-climate relationships in trees: explaining the influence of previous summers’ climate on ring width. Tree Physiol 35:319–330. https://doi.org/10.1093/treephys/tpv007

Hacket-Pain A, Ascoli D, Berretti R et al (2019) Temperature and masting control Norway spruce growth, but with high individual tree variability. For Ecol Manage 438:142–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2019.02.014

Hartig F (2022) Residual Diagnostics for Hierarchical (Multi-Level/Mixed) Regression Models. R package version 0.4.6

Hesse BD, Hartmann H, Rötzer T et al (2021) Mature beech and spruce trees under drought–Higher C investment in reproduction at the expense of whole-tree NSC stores. Environ Exp Bot 191:104615. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envexpbot.2021.104615

Innes JL (1994) The occurrence of flowering and fruiting on individual trees over 3 years and their effects on subsequent crown condition. Trees 8:139–150. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00196638

Journé V, Caignard T, Hacket-Pain A, Bogdziewicz M (2021) Leaf phenology correlates with fruit production in European beech (Fagus sylvatica) and in temperate oaks (Quercus robur and Quercus petraea). Eur J for Res 140:733–744. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10342-021-01363-2

Kelly D, Sork VL (2002) Mast seeding in perennial plants: why, how, where? Annu Rev Ecol Syst 33:427–447. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.33.020602.095433

Koenig WD (2002) Global patterns of environmental synchrony and the Moran effect. Ecography (Cop) 25:283–288

Lauder JD, Moran EV, Hart SC (2019) Fight or flight? Potential tradeoffs between drought defense and reproduction in conifers. Tree Physiol 39:1071–1085. https://doi.org/10.1093/treephys/tpz031

Lebourgeois F, Delpierre N, Dufrêne E et al (2018) Assessing the roles of temperature, carbon inputs and airborne pollen as drivers of fructification in European temperate deciduous forests. Eur J for Res 137:349–365. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10342-018-1108-1

Marra G, Wood SN (2011) Practical variable selection for generalized additive models. Comput Stat Data Anal 55:2372–2387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csda.2011.02.004

Meng F, Yuan Y, Jung S et al (2022) Long-term flowering intensity of European tree species under the influence of climatic and resource dynamic variables. Agric for Meteorol 323:109074. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2022.109074

Minor DM, Kobe RK (2017) Masting synchrony in northern hardwood forests: super-producers govern population fruit production. J Ecol 105:987–998. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2745.12729

Müller-Haubold H, Hertel D, Seidel D et al (2013) Climate responses of aboveground productivity and allocation in Fagus sylvatica: a transect study in mature forests. Ecosystems 16:1498–1516. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-013-9698-4

Müller-Haubold H, Hertel D, Leuschner C (2015) Climatic drivers of mast fruiting in European beech and resulting C and N allocation shifts. Ecosystems 18:1083–1100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-015-9885-6

Mund M, Herbst M, Knohl A et al (2020) It is not just a ‘trade-off’: indications for sink- and source-limitation to vegetative and regenerative growth in an old-growth beech forest. New Phytol 226:111–125. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.16408

Nussbaumer A, Waldner P, Etzold S et al (2016) Patterns of mast fruiting of common beech, sessile and common oak, Norway spruce and Scots pine in central and northern Europe. For Ecol Manag 363:237–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2015.12.033

Nussbaumer A, Waldner P, Apuhtin V et al (2018) Impact of weather cues and resource dynamics on mast occurrence in the main forest tree species in Europe. For Ecol Manag 429:336–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2018.07.011

Nussbaumer A, Gessler A, Benham S et al (2021) Contrasting resource dynamics in mast years for European beech and oak—a continental scale analysis. Front for Glob Chang 4:1–17. https://doi.org/10.3389/ffgc.2021.689836

Oddou-Muratorio S, Petit-Cailleux C, Journé V et al (2021) Crown defoliation decreases reproduction and wood growth in a marginal European beech population. Ann Bot 128:193–204. https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcab054

Pearse IS, Koenig WD, Kelly D (2016) Mechanisms of mast seeding: resources, weather, cues, and selection. New Phytol 212:546–562. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.14114

Pedersen EJ, Miller DL, Simpson GL, Ross N (2019) Hierarchical generalized additive models in ecology: an introduction with mgcv. PeerJ. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.6876

Pesendorfer MB, Bogdziewicz M, Szymkowiak J et al (2020) Investigating the relationship between climate, stand age, and temporal trends in masting behavior of European forest trees. Glob Chang Biol 26:1654–1667. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.14945

Piovesan G, Adams JM (2001) Masting behaviour in beech: linking reproduction and climatic variation. Can J Bot 79:1039–1047. https://doi.org/10.1139/b01-089

R Core Team (2023) R: a language and environment for statistical computing

Schütt P, Schuck HJ, Stimm B (eds) (2002) Lexikon der Baum- und Straucharten : das Standardwerk der Forstbotanik: Morphologie, Pathologie, Ökologie und Systematik wichtiger Baum- und Straucharten. Nikol Verlagsgesellschaft mbH & Co. KG, Hamburg

Seidling W, Ziche D, Beck W (2012) Climate responses and interrelations of stem increment and crown transparency in Norway spruce, Scots pine, and common beech. For Ecol Manage 284:196–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2012.07.015

Seifert T, Müller-Starck G (2009) Impacts of fructification on biomass production and correlated genetic effects in Norway spruce (Picea abies [L.] Karst.). Eur J for Res 128:155–169. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10342-008-0219-5

Selås V, Piovesan G, Adams JM, Bernabei M (2002) Climatic factors controlling reproduction and growth of Norway spruce in southern Norway. Can J for Res 32:217–225. https://doi.org/10.1139/x01-192

Stolz J, Forkel M, van der Maaten E et al (2023) Through eagle eyes—the potential of satellite-derived LAI time series to estimate masting events and tree-ring width of European beech. Reg Environ Change 23:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-023-02068-5

Tapper P (1992) Irregular fruiting in Fraxinus excelsior. J Veg Sci 3:41–46. https://doi.org/10.2307/3235996

Vacchiano G, Hacket-Pain A, Turco M et al (2017) Spatial patterns and broad-scale weather cues of beech mast seeding in Europe. New Phytol 215:595–608. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.14600

Vacchiano G, Ascoli D, Berzaghi F et al (2018) Reproducing reproduction: how to simulate mast seeding in forest models. Ecol Modell 376:40–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2018.03.004

Vitasse Y, Baumgarten F, Zohner CM et al (2021) Impact of microclimatic conditions and resource availability on spring and autumn phenology of temperate tree seedlings. New Phytol 232:537–550. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.17606

Wellbrock N, Eickenscheidt N, Hilbrig L et al (2018) Leitfaden und Dokumentation zur Waldzustandserhebung in Deutschland. Thünen Work Pap 84:97

Westergren M, Archambeau J, Bajc M et al (2023) Low but significant evolutionary potential for growth, phenology and reproduction traits in European beech. Mol Ecol. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.17196

Wion AP, Pearse IS, Rodman KC et al (2023) Masting is shaped by tree-level attributes and stand structure, more than climate, in a Rocky Mountain conifer species. For Ecol Manag 531:120794. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2023.120794

Wood SN (2003) Thin plate regression splines. J R Stat Soc Ser B Stat Methodol 65:95–114. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9868.00374

Wood SN (2011) Fast stable restricted maximum likelihood and marginal likelihood estimation of semiparametric generalized linear models. J R Stat Soc Ser B Stat Methodol 73:3–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9868.2010.00749.x

Wood SN (2017) Generalized Additive Models. In: An introduction with R, 2nd Edn. Chapman & Hall/CRC, Boca Raton

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the field teams who carry out the annual forest monitoring. We would also like to thank Alexandra Wauer, Hans-Peter Dietrich and Michael Heym for their support concerning data provision and interpretation.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. MH was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation)–454840041.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MH and TS conceived the study. MH carried out the analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. TS revised the original draft. HP and HK provided the monitoring data and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Communicated by Martin Ehbrecht.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hirsch, M., Puhlmann, H., Klemmt, HJ. et al. Modelling fructification intensity at the tree level reveals species-specific effects of tree age, social status and crown defoliation across major European tree species. Eur J Forest Res 144, 1505–1522 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10342-025-01822-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10342-025-01822-0