Abstract

In recent years, significant progress has been made in treatment access for women living with HIV (WLHIV). For example, option B+, which requires that all pregnant persons who test positive for HIV start on antiretroviral treatment, has been instrumental in reducing the risk of vertical transmission. For birthing individuals who have a low HIV viral load, there is a minimized risk of vertical transmission during breastfeeding. However, an alarming rate of WLHIV in South Africa disengage from care during postpartum. Given that work is intricately linked to individuals’ socioeconomic status, and thus health outcomes, and their health-seeking ability, it is important to explore the role of work in decisions that impact HIV-related care for the dyad postpartum. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 26 women living with HIV at 6–8 weeks postpartum in Cape Town, South Africa. A secondary qualitative data analysis was conducted following thematic content analysis. Three themes were identified, spanning participants’ financial considerations, navigating childcare needs, and considerations for exclusive breastfeeding. For many participants, there was often a conflict between returning to work, childcare, and the decision whether or not to breastfeed—in addition to their HIV care. This conflict between participants’ commitments suggests an increased pressure that WLHIV may face postpartum, which could impact their ability to remain engaged in their healthcare and adherent to medication. Although exclusive breastfeeding is an important recommendation for the baby’s health outcomes; there is a need for structural support for WLHIV as they navigate work re-entry during postpartum.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In 2017, 51% of the 36.7 million people living with HIV globally were women [1]. Women in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) are among the most vulnerable populations for HIV acquisition. In 2013, South Africa implemented Option B+ as part of its prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV (PMTCT) efforts [2]. Option B+ is an initiative through which pregnant persons who test positive for HIV are started on lifetime anti-retroviral therapy (ART) regardless of their CD4 count. It has been shown to be effective in promoting viral suppression, therefore protecting the health of pregnant individuals, and reducing the risk of vertical HIV transmission to the child [3].

Despite the positive impact of Option B+, disengagement from care during the postpartum period is of considerable concern [4] and is detrimental to both the mother and child. Some of the health outcomes for disengagement include: immunocompromise, which may increase the risk of medical complications, as well as other complications from mental health and medical comorbidities; and death [5]. Thus, it is important to understand the barriers that hinder care engagement, in order to explore ways to improve care among this vulnerable sub-population.

Research suggests that barriers to care engagement may include transportation access [6], conflicting responsibilities, or structural stigma [7]. In addition, a potentially important issue that affects individuals’ care engagement postpartum is work entry or re-entry, which may impact individuals’ socioeconomic status and health seeking ability [8]. In this paper, work is defined as any income-generating activity that the participants were involved in, and includes both formal and informal employment. For this research, our definition of work did not include uncompensated “mothering” labor, which many of the participants continue to do [9, 10].

Since the data presented in this paper was collected around 6 to 8 weeks after childbirth, some individuals may have been receiving maternity leave funds through the Unemployment Insurance Fund (UIF hereafter). South Africa mandates at least four consecutive months of unpaid maternity leave, and in addition, some types of employment also offer maternity benefits if an individual previously contributed to the UIF [11]. In the context of South Africa, financial resources for low-income individuals could also include the Child Support Grant (referred to as CSG hereafter). The CSG aims to support low-income families with children younger than 18 years, that earn less than ZAR 4000 (~ USD 260) per month for a single-income household or ZAR 8000 (~ USD 520) per month for a dual income household [12]. However, current literature shows that the CSG is usually delayed for first-time mothers due to the complexity of getting approved for, and receiving funding [12]. All three financial mechanisms (income, UIF, and CSG) are mentioned in participant interviews, though to varying extents.

Previous research regarding work return in South Africa has advocated for improved regulations for paid parental leave among informal workers, such as domestic workers [13]. Among various considerations related to maternity protection and work return, feeding practices have been a prevalent factor in the literature: in some instances, mothers changed their feeding choices to facilitate work return [14, 15]. In South Africa, as in many countries in SSA, the WHO recommends exclusive breastfeeding in the first 6 months postpartum. In combination with option B+, the risk of vertical transmission when WLHIV breastfeed is low given optimum adherence and viral suppression [16]. Therefore exclusive breastfeeding is more favored [17].

However, individuals often have to negotiate conflicting responsibilities in their postpartum period, such as when or whether to return to work, their babies’ feeding method, as well as financial challenges [8]. For example, a cohort study by Luthuli and colleagues in Durban, South Africa revealed that due to financial pressures, some mothers were forced to return to work earlier than desired, and had to adapt their work to facilitate childcare (e.g. selling products from home) and feeding [8]. Similarly, a qualitative exploratory study interviewed employed mothers and senior managers in a provincial government setting in South Africa, in order to discuss breastfeeding experiences, facilitators, as well as barriers to breastfeeding for these working women [15]. In the study, the researchers learned that many formal workplaces did not have adequate facilities for individuals who were breastfeeding, and many women stopped breastfeeding right before or just after returning to work as a result.

While existing literature outlines the experiences of, and challenges faced by, individuals as they transition into the labor-force post-partum, our paper looks specifically at the experiences of Women Living With HIV (WLHIV hereafter) in this context. It is crucial to study the interrelation between individuals’ work and other aspects of their lives, which impact their decision or ability to continue seeking care.

Research has noted the alarming rates of disengagement from HIV-related care in the postpartum period [4, 18], and more work is being done to understand the major drivers behind disengagement. This paper uses qualitative data to explore how mothers living with HIV negotiate their return to the workforce, with considerations around their own HIV-related care and that of their newborn.

Methods

This qualitative study is part of a larger study conducted at Gugulethu Midwife Obstetrics Unit (GMOU) in Cape Town, South Africa. It followed participants from pregnancy up to 1-year post-partum. Participants were interviewed during pregnancy (Timepoint 1); at 6–8 weeks post-partum (Timepoint 2), at 4 to 6 months post-partum (Timepoint 3), and at 1-year post-partum (Timepoint 4). This analysis focuses on individuals’ experiences at Timepoint 2: 6 to 8 weeks post-partum, which reflects both the participants’ prior plans for their postpartum period and any changes after childbirth, so it concisely captured mothers’ perceptions of the barriers and facilitators to remaining engaged in care postpartum.

Recruitment and Sampling

The research staff recruited pregnant women attending the GMOU for their antenatal care from the waiting room. Potential participants were told about the study and asked if they would be interested in participating. Individuals interested in the study were led to a private room for screening. Eligibility criteria included women who were: (a) 18 years or older, (b) at 32–35 weeks gestation (8 months), (c) HIV positive as per clinic records, (d) prescribed antiretroviral therapy (ART) at time of enrollment, and (e) able to speak and understand either English or isiXhosa. The exclusion criteria were: (a) women whose pregnancy was categorized as high-risk for reasons other than HIV status (e.g. preeclampsia, preterm labor), (b) self-reported participation in another ART adherence related study, or (c) inability to understand the consent process.

The study used purposeful sampling for maximum variation and intentionally enrolled a diverse group in terms of age (18- to 24-year-old women and women older than 24 years of age); parity (first-time pregnancy and previous pregnancy); as well as education status (women who had completed high school and those who had not). The study captures various experiences of women at different stages of their lives, who had an array of experiences with motherhood, illness, and the interaction between the two.

Data Collection

Thirty women were enrolled in the study; of those, 26 completed time point 2 interviews. As work was not the main focus of the parent study; for 2 participants, work (re-)entry was not discussed at all, either due to the lack of capacity to discuss work or a participant’s prioritization of other questions. In addition, 3 participants were considering going to school instead. As such, a total of five timepoint 2 interviews were not analyzed for the purposes of this paper.

Data collection was done using semi-structured interviews, conducted by a research staff member local to Gugulethu, who is fluent in both isiXhosa and English. Although the analysis and discussion of individuals’ experiences in this paper is based on the entirety of the interview, a question that was specific to work re-entryasked whether participants were planning to return to work, motivations for work re-entry, what childcare would look like, and how women would maintain their treatment adherence in relation to their return to work.Footnote 1 In addition, a follow-up question was asked about receiving financial support from either the participant’s partner or family.

Interviews were conducted in the participants’ preferred language, and if in isiXhosa, were translated into English for analysis. Interview agendas were written in English, translated to isiXhosa, and back-translated to English to ensure that questions would remain consistent between the two languages, and that any cultural meanings on either side would be preserved. Individuals who participated in the study received ZAR 100 (which was equivalent to US$10.00 at the time) after the completed interview.

Data Analysis

For data analysis, thematic content analysis was followed [19] and NVivo™ software was used to manage the data [20]. The analysis was modelled following guidelines provided by Green and Thorogood [21]. JP and MK referenced existing literature to develop an apriori codebook, which included codes related to childcare, travel, and feeding practices. MK then read through the transcripts and used open coding to redefine and add on to the initial codes. Following this iterative process, MK and JP cross-referenced the codebook with colleagues through two rounds of peer-review (with a research team of female-identifying doctoral, master’s and undergraduate students). Major themes were identified from iterative coding of the transcripts and were revised according to discussion and review with the research team.Footnote 2

Results

At the time of data collection (around 6 to 8 weeks postpartum), none of the participants were actively working. Transcript data showed that three of the participants were on maternity leave at that time, and one additional participant was in between contracts—not on maternity leave. The majority of the participants (81%) were not employed at this time. Some were planning on looking for jobs by 3 months postpartum or earlier, many planned on looking for jobs at 6 months postpartum, while only 2 wanted to wait until the newborn had turned a year old to return to the workforce. Based on the breakdown of average monthly income and data from South African income classifications in 2018, the participants were in low-income households [22] (Table 1).

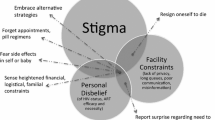

Figure 1 maps the relationships between the themes. Importantly, this is not a causal or correlation pathway. The weight of the arrow indicates the relative prevalence of the relationship based on the interviews with participants. The major themes developed from our analysis were impacted by financial considerations, decisions around breastfeeding as well as navigating childcare needs. In relationship (a), the decision to return to work or start looking for work was driven by the need for increased financial support during the postpartum period. Relationship (a) is explored in detail in theme 1: financial considerations. However, in many cases, the timing of work return was nuanced by the need to get reliable, healthcare-conscious, yet affordable childcare for the newborn—relationship (c). Considerations for appropriate HIV-related care for the newborn impacted childcare considerations in two ways, which are explored in theme 2: navigating childcare needs. In relationships (g) and (e), many mothers opted for exclusive breastfeeding as was advised at the healthcare setting, but this meant that they had to think about expressing breastmilk if they sent their baby to daycare, or to avoid childcare altogether for fear that the child carer may feed the newborn inappropriately. Relationship (f) was less salient for most participants but was crucial to the analysis in cases where it came up. For newborns who were on preventative HIV medication/prophylaxis, mothers had to consider whether a potential child carer would administer medication as needed to the newborn. In regard to relationship (d), many participants had to think about their preferred feeding method in relation to their planned timeline for work return. Theme 3: feeding choices shows that some participants decided to look for jobs 6-months after exclusive breastfeeding, while others decided to introduce formula feeding earlier to facilitate work return. As seen in the figure, financial considerations and their impact on the decision and timing for work return was the most salient among participant responses.

Theme 1: Participants’ decisions for engaging in care were preceded by financial considerations about childcare and feeding methods

While theme 1 is not directly about participants’ HIV status, it has inextricable implications for the health of the mother and the newborn. Interview data revealed that baby clinic appointments and the mothers’ HIV-care appointments were not always on the same day, which necessitated travelling to the clinic on two separate occasions within a short period of time—hence an increased financial burden related to their HIV care.

Participants’ financial motivations for returning to work were twofold: first, they felt empowered by the prospect of financial independence (either from their partner or family member), and second, the potential to take care of the baby, by paying for their healthcare, buying diapers, and/or buying food for the family. Mothers cited that they wanted to take care of [their] kids (P107), which indicated a link between their own perception of motherhood and the need for financial independence from family. I have to take care of my kids because one day my mom and my mother-in-law will pass on.… I have to stand up on my own and do the best I can for my kids. […] What will help me is to go out and look for jobs when my new baby has reached the stage where he will be able to eat baby food….I will be proud to be an independent mother….I want to meet half way my family. (P107 single never married, not employed, will start looking for jobs at 6 months).

This suggests that being an independent mother meant the ability to make an income, and lessening the financial burden of their partners or family members. Participants felt a need to contribute toward the baby’s care financially, and were therefore eager to start looking for work, or to return to their jobs. As one mother expressed, I wish I could do the best for my children instead of depending [on] their father. For example: If I ask my baby boy about who bought clothes for him? His reply is ‘my father bought them for me’ although I took him out for shopping…He believes everything comes from his dad. (P118 living with partner, not employed). This data helps to understand that for many of our participants, their lack of employment at the time of data collection significantly impacted their financial security, which could have implications for their ability to seek HIV-related care for themselves and their newborn.

Four of the mothers reported being formally employed at enrollment, among whom, three discussed going “back to work” in their interviews. For the formally employed mothers in the sample, there was less discussion about financial security. For example, when asked who supports you financially?, P126, who was on a 3-month maternity leave replied: it’s the father of the baby and I am also getting UIF (Unemployment Insurance fund), […] now. (P126 single never married, employed, on 3-month maternity). Among the many individuals who were not in formal employment at the time, some talked about the prospect of applying for the child support grant and receiving financial support from their partner and/or family. For example, P112—whose partner was unemployed at the time—had started applying for the child support grant by the interview date, another challenge is that my partner is unemployed. […] I started to apply [for the child support grant] last week on Monday.[…] I was informed that I will start receiving the money on the 9 … of next month. (P112 single never married, not employed, will start looking after 7 months). These alternative forms of financial support are discussed in more detail in another paper.

As seen in Fig. 1, financial empowerment influenced decisions about childcare and deciding on the appropriate feeding method for the newborn. In addition to these relationships, theme 1 lays the groundwork for understanding the needs that mothers living with HIV may have at this time, and ways in which they can be supported. Given the increase in costs during the postpartum period coupled with the decrease in sources of income, it is understandable that most participants wanted to go back to work to help alleviate the financial burden on their family and/or intimate partners.

Theme 2: Childcare Considerations and HIV-Related Care for Both Mother and Baby Influenced the Timing of Work Re-entry

When asked about their return to work, many mothers immediately discussed worries about childcare, which were compounded by their HIV status. Participants worried about a caregiver’s ability to take care of their child as needed. For example, mothers and caregivers had to know which HIV prophylaxis medication to give to the baby, and the correct time to administer it. Newborn babies to WLHIV may be given antiretroviral prophylaxis such as Nevirapine (AZT/sdNVP) to further reduce the risk of vertical transmission [23]. P108 mentioned, I give her Nevirapine … She takes it once daily at eleven in the morning (11:00 am). I give her five centimetres daily [5ml]…: I got them here in this MOU after giving birth (P108 single never married, not employed, looking to change jobs). Thus, mothers justifiably worried about potential caregivers’ ability to adhere to clinic recommendations, given the need for adequate caution to limit HIV risk in the newborn.

This worry influenced a mother’s timing for her return to work, as well as her decision on the baby’s feeding method (which will be discussed in the next theme). The quote below encapsulates P111’s concerns about childcare, potential HIV disclosure, and feeding choices, [If I went back to work earlier] I would ask my sister who I am very close with to look after my baby. We share everything together and she knows about my medications. My child would be safe under my sister’s care (P111 married, plans to look for employment). Given the aforementioned considerations, some mothers decided to delay their return to work. P111 continued, I am breastfeeding my baby and now I think the workers at crèche might feed her with food they are not supposed to feed her with. [… As a result,] I am thinking of raising her until she is 3 months old and go back to business. I will breast[feed] her until she is 6 months old and I will stop breast feeding and I will be able to send her to the crèche (P111 married, plans to look for employment).

From the interviews, it was apparent that clinic recommendations about breastfeeding, especially for HIV positive mothers, were often strict, and that mothers feared that not following the recommendations would result in their newborn acquiring HIV. I was shouted [at] by the nurse who attended to me today at the clinic because of breaking rules/instructions/clinic recommendations. […] I will blame myself if my baby could end up being infected with HIV. I am so anxious; I can’t wait to see her get tested for HIV and to receive her HIV results. (P105 living with partner, not employed, willing to start work as early as 3-months postpartum). P105’s worry about her baby contracting HIV if she does not follow clinic recommendations explains the conflict in mothers’ decision between having a paid caregiver or nanny, taking the baby to a crèche/nursery, and leaving the baby with a trusted family member –the latter was often preferred.

Theme 3: The Recommended Exclusive Breastfeeding Acted as a Barrier for Mothers Thinking About the Timing of Their Work Return and Other Competing Responsibilities

As seen in theme 2, participants did not always find it easy to follow the health policy recommendation for exclusive breastfeeding (referred to as EBF hereafter). For many mothers, this seemed like a choice whether or not to delay their work (re-)entry until the baby was 6 months old. … So I am breastfeeding nowadays because I am just- I just want to prevent the baby from getting infected before the six months. And I am not yet prepared to get the job because I am [waiting] until six months. I can just- if I get money I can just buy things and sell, buy things and sell, ay. Until six months. So that I will be able to go for work, the baby will be grown up. (P125 married, not employed, will start business until 6-month mark).

An alternative was to completely stop breastfeeding the baby at an earlier age to facilitate transition into the workforce. P130: I was not comfortable to continue with breastfeeding my baby because I was going back to work and I was going to hire a nanny to take care of her. I had a feeling that a nanny could possibl[y] mix feed my baby so I decided to stop breastfeeding her and start feeding her with formula milk. I went to report to the [clinic] when I started to feed my baby with formula milk and they were fine with my decision. (P130 single never married, employed, returns to work at 3 months postpartum).

Given that a majority of the mothers were not engaged in formal employment, they could negotiate their re-entry time into the workforce more flexibly than their formally employed counterparts, and often preferred to return after the 6-months period of recommended EBF. However, they were less likely to have paid maternity leave, and in reality, went back to work earlier than planned (which is seen at a later timepoint and discussed in another paper). For mothers that had ample social and financial support—especially from family and their partner—it was more feasible to delay return to work, and therefore breastfeed the baby and administer their medication as needed.

P110, for example, decided to delay her return to work, at which point she would be able to take him to a creche, “I had a conversation with my partner yesterday”, she said, “[and] I prefer to go back to work when he is one year old”. (P110 single never married, not employed, not looking until 1 year). In some scenarios, family members and/or participants’ intimate partners could not provide financial support but were able to help with caring for the baby, which alleviated the stress of finding childcare when they returned to work. P101 in one part of the interview said, “I can go back to work as soon as I get a job because I need money// My mother can take of my baby”, then later in the interview commented, it doesn’t matter if my partner is not working as long as he is there to support me. For example, when I go to the clinic; it would be a great feeling to have his company so that he learns how to take our baby to the clinic if I cannot make it (P101, single, never married, looking for jobs). This decision was not only about the need for a breastfeeding-friendly work environment but about childcare and HIV-related care.

Discussion

The findings suggest that mothers living with HIV in our sample had three major considerations in deciding to either return to work or look for jobs, namely: financial considerations, navigating childcare needs, and feeding choices. In our data, financial considerations had a strong impact on the decision and timing to return to work and to start looking for jobs postpartum. However, this relationship was nuanced by the need for affordable childcare that would not place the baby’s health at risk, and the mother’s choice regarding exclusive breastfeeding. For many mothers who wished to follow clinic recommendations and exclusively breastfeed for the first 6 months, that would mean returning to work later and losing out on potential sources of income during that time. While many of our participants were extremely anxious about being good patients: taking their medication as needed, and following EBF as recommended at the clinic, this was not often feasible—given other competing responsibilities that they had to navigate. Eventually, some mothers returned to work earlier and had to re-negotiate the baby’s feeding method. In this study, the need for work was pronounced since many of the women were not in the formal sector, and thus were at higher risk of financial insecurity postpartum.

Results from our study echo findings from broader literature. A similar study based in Durban, South Africa, explored the postpartum experiences of women in the informal workforce—though not among WLHIV [8]. The researchers found that informal workers sometimes had to opt for formular feeding to accommodate earlier return to work. Our work extends this analysis by focusing on the experiences of WLHIV. We found that for WLHIV, decisions around work are arguably more complicated given the caregiver’s ability to administer medication to the baby as needed and to adhere to the mother’s chosen feeding method. Our results propose that returning to work in order to gain financial independence is not as straightforward a decision for most mothers; they also need to weigh the decision with other competing interests, such as childcare and clinic recommendations.

Given this complication, the discussion about work is not merely about having money, but about social position, power, and agency. For our participants, their socioeconomic status (tied to their employment type) placed them at an increased financial pressure during the postpartum transition, which restricted some individuals’ decisions about when to return to work. They had to navigate choices about their own health and the health of their newborns amidst limiting socio-economic circumstances. An intersectionality lens [9, 24,25,26] demands that individuals (in this case, WLHIV) be accommodated by health recommendations in parallel with the social, economic, political and structural backgrounds within which they live. Granted, exclusive breastfeeding would be ideal for promoting a baby’s health while also maintaining low risk of vertical transmission [27,28,29], however, there is currently insufficient support for WLHIV who wish to breastfeed. The CSG was not discussed in detail in the interviews, but given its importance, future research needs to examine the impact/role of the Child Support Grant in the postpartum experience of WLHIV.

Implications of the Research

These findings are important to thinking about global women’s health in general, and in regard to the management of HIV in women. It is through understanding the social context of individuals’ lives that health recommendations and policies can be applied. While Option B+ and EBF have been pivotal in preventing vertical transmission and promoting good health in WLHIV, there is a need for further research and programming that addresses the needs of WLHIV during the postpartum transition, specifically related to the tension between recommendations around EBF which can impede return to work, and the motivation of new mothers to return to work and gain financial independence.

Strengths and Limitations

A key strength of this research is the use of qualitative research to center the experiences of WLHIV, and to explore their perception of barriers and facilitators for work (re-)entry. This research builds on findings from a previous project to compare the experiences of WLHIV during pregnancy with their postpartum experience; and adds nuance to current, relevant research by showing ways in which the experiences of work re-entry differ for the average low-income woman in South Africa given her HIV status.

One of the limitations of this study is that a distinction was not made in the demographic surveys between informal and formal work. However, the researchers read through the transcripts to infer the type of employment that was referenced by the participants. Perhaps future demographic questionnaires could make the distinction between the type of work individuals are involved in, and future research could also look into other forms of uncompensated labor. It is the hope that this research does not contribute to the privileging of certain types of work (such as formal, regularly paid work) over others, but rather, serves to expand the view of health beyond a healthcare setting, and into individuals’ daily lives. It would be important to have a longitudinal analysis that looks at how (if any) changes occur throughout postpartum, and what support looks like for postpartum WLHIV.

Conclusion

This paper aimed to explore women’s experiences with work re-entry post-partum, how this relates with engaging in HIV care and, more generally, decisions that impact the health of individuals and their newborns. The main argument, that work re-entry is intricately linked to a mother’s health experience and health-seeking ability, has been demonstrated by drawing the link between the need for financial independence, complexities in seeking adequate childcare, and the timing of work return to accommodate exclusive breastfeeding recommendations. In essence, work is central to thinking about the health of WLHIV during the postpartum period, and ought to be accounted for in the development and implementation of health recommendations.

Notes

Find the interview guide on socio-economic status in appendix, file 1.

Find the final codebook exported from NVivo submitted as part of supplementary material.

References

UNAIDS, Women, Adolescent girls and the HIV response. 2020. https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/presscentre/pressreleaseandstatementarchive/2020/march/20200305_weve-got-the-power

Maskew M, et al. Implementation of Option B and a fixed-dose combination antiretroviral regimen for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in South Africa: a model of uptake and adherence to care. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(8): e0201955. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0201955.

Etoori D, et al. Challenges and successes in the implementation of option B+ to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV in southern Swaziland. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):374. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5258-3.

Phillips T, Thebus E, Bekker L-G, McIntyre J, Abrams EJ, Myer L. Disengagement of HIV-positive pregnant and postpartum women from antiretroviral therapy services: a cohort study. J Int AIDS Soc. 2014;17(1):19242. https://doi.org/10.7448/IAS.17.1.19242.

Scott RK. Adherence among post-partum women living with HIV. Lancet HIV. 2020;7(3):e152–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(19)30403-5.

Boehme AK, Davies SL, Moneyham L, Shrestha S, Schumacher J, Kempf M-C. A qualitative study on factors impacting HIV care adherence among postpartum HIV-infected women in the rural southeastern USA. AIDS Care. 2014;26(5):574–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2013.844759.

Buchberg MK, et al. A mixed-methods approach to understanding barriers to postpartum retention in care among low-income, HIV-infected women. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2015;29(3):126–32. https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2014.0227.

Luthuli S, Haskins L, Mapumulo S, Rollins N, Horwood C. ‘I decided to go back to work so I can afford to buy her formula’: a longitudinal mixed-methods study to explore how women in informal work balance the competing demands of infant feeding and working to provide for their family. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1847. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09917-6.

Hill Collins P, Bilge S. Intersectionality. In Key concepts series. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2016.

Flowers NZ. Fruits of momma’s labor: a qualitative analysis of motherwork in Los Angeles. Sociology, UC Santa Barbara. 2019. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7n17z3pv. Accessed 02 Apr 2022

Basic Conditions of Employment Act of 1997. 1998. https://www.gov.za/documents/basic-conditions-employment-act

Luthuli S, Haskins L, Mapumulo S, Horwood C. Does the unconditional cash transfer program in South Africa provide support for women after child birth? Barriers to accessing the child support grant among women in informal work in Durban, South Africa. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):112. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-12503-7.

Pereira-Kotze C, Faber M, Doherty T. Knowledge, understanding and perceptions of key stakeholders on the maternity protection available and accessible to female domestic workers in South Africa. PLoS Glob Public Health. 2023;3(6): e0001199. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0001199.

Horwood C, et al. Attitudes and perceptions about breastfeeding among female and male informal workers in India and South Africa. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):875. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09013-9.

Mabaso BP, Jaga A, Doherty T. Experiences of workplace breastfeeding in a provincial government setting: a qualitative exploratory study among managers and mothers in South Africa. Int Breastfeed J. 2020;15(1):100. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13006-020-00342-4.

West NS, et al. Infant feeding by South African mothers living with HIV: implications for future training of health care workers and the need for consistent counseling. Int Breastfeed J. 2019;14(1):11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13006-019-0205-1.

Tuthill E, McGrath J, Young S. Commonalities and differences in infant feeding attitudes and practices in the context of HIV in sub-Saharan Africa: a metasynthesis. AIDS Care. 2014;26(2):214–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2013.813625.

Myer L, Phillips TK. Beyond ‘Option B+’: understanding antiretroviral therapy (ART) adherence, retention in care and engagement in ART services among pregnant and postpartum women initiating therapy in sub-Saharan Africa. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;75:S115. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000001343.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

QSR International Pty Ltd. NVivo 2020. 2020. https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home

Green J, Thorogood N. Qualitative methods for health research, 4th edition. in Introducing qualitative methods. Los Angeles: SAGE; 2018.

Maphupha P. The reliability of public transport: a case study of Johannesburg. Public Transp. 2018;1:1–64.

Chappell CA, Cohn SE. Prevention of perinatal transmission of human immunodeficiency virus. Infect Dis Clin N Am. 2014;28(4):529–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.idc.2014.08.002.

Davis AY. Women, race and class. London: Women’s Press; 1994.

Roberts DE. Killing the black body: race, reproduction, and the meaning of liberty. 1st ed. New York: Pantheon Books; 1997.

Crenshaw K. On intersectionality: essential writings. New York: New Press; 2019.

Kafulafula UK, Hutchinson MK, Gennaro S, Guttmacher S. Maternal and health care workers’ perceptions of the effects of exclusive breastfeeding by HIV positive mothers on maternal and infant health in Blantyre, Malawi. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14(1):247. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-14-247.

Lawani L, Onyebuchi A, Iyoke C, Onoh R, Nkwo P. The challenges of adherence to infant feeding choices in prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV infections in South East Nigeria. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2014. https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S61796.

UNAIDS. 2012 UNAIDS Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic. 2012. https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2012/20121120_UNAIDS_Global_Report_2012. Accessed 02 Apr 2022.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our interviewer, Zanele Rini, also affectionately addressed as sis Zan by the participants. We are thankful to the mothers who participated in this research, who were vulnerable, authentic, and open in sharing their experiences.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health (Grant number: K01MH112443). Parts of this paper have been submitted for an Honors thesis, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduating with the degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors in the Public Health Concentration, School of Public Health, at Brown University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

aParticipant 107.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kopeka, M., Laws, M.B., Harrison, A. et al. “I Have to Stand Up on My Own and Do the Best I Can for My Kids”a: Work (Re-)entry Among New Mothers Living with HIV in Cape Town, South Africa. AIDS Behav (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-024-04478-w

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-024-04478-w