Abstract

This study underscores the critical importance of integrating biodiversity considerations into urban planning, demonstrating how diverse urban structures can support bird populations while contributing to the resilience of urban ecosystems. The research investigates whether significant differences exist among urban configurations in terms of species richness and individual abundance. The proposed urban configurations—historic centres, open blocks, and closed blocks—were examined in Valencia, Spain. Urban composition data were obtained from open-access platforms, and bird information was sourced from the SACRE citizen science program. Data were organized hierarchically and analyzed using Generalized Linear Mixed Models (GLMMs), complemented by the AIC criterion and QQ plot residuals. The study recorded 23 bird species, with the lowest richness observed in historic centres (13 species). Significant ecological differences were found among birds that feed in the air, in trees and shrubs, and those that nest in buildings. The findings highlight the ecological value of historic buildings, which offer critical nesting opportunities. Among the three urban habitat types, the most common species were the common swift (Apus apus), rock pigeon (Columba livia), house sparrow (Passer domesticus), and Eurasian collared dove (Streptopelia decaocto). Additionally, this research discusses the decline of European swift populations and house sparrow, linking it to modern building practices that reduce nesting sites. By emphasizing the ecological consequences of urban development and the need for biodiversity-friendly measures, this study contributes to understanding how urban planning can promote conservation and mitigate biodiversity loss in rapidly changing urban landscapes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent decades, there has been worldwide rapid urbanization (Yang et al. 2023). This in turn has had significant effects on biodiversity loss (Zhang et al. 2020; Das et al. 2024; Paniagua-Villada et al. 2024), imapacting habitats (Fariha et al. 2024), natural ecosystems (Vargas-Hernández and Zdunek-Wielgołaska 2021), and species diversity (Santos et al. 2024). Additionally, species which cannot adapt to urban environments are displaced or driven to extinction, leading to a homogenization of urban biota, where survival is only guaranteed to the most adaptable species (Seto et al. 2012).

In a broader macroecological sense, cities generally contain a proportion of each of the three principal land cover typologies: green areas, water, and impervious surfaces (Dobbs et al. 2017). Green areas are closely linked to biodiversity (Huang et al., 2022; Huang et al. 2023) as they provide habitat for species (Yang et al. 2020; Cao et al. 2023; Rahimi-Ardabili et al. 2021). The most important driving forces of the richness of species within a city are the proportion of water cover and tree cover (Callaghan et al. 2021). Therefore, previous studies which have given particular attention to green spaces (Winardi et al. 2023) have been widely analysed in urban contexts, as has the response of birds to landscape features (Cristaldi et al. 2023).

Furthermore, the impervious surfaces in cities are made up of buildings and infrastructure including streets and sidewalks. Studies on biodiversity in cities often focus on how the degree of urbanization affects species (Callaghan et al. 2019; Adams et al. 2020; Yang et al. 2023). Some key factors benefitting biodiversity in urban areas have been identified. Historic centres, with their older and diverse infrastructure, often provide microhabitats that can support greater species diversity, particularly for birds which find opportunities for nesting and shelter in these buildings (Guyot et al. 2021).

Additionally, species dispersion and ecological connectivity are shaped by the spatial arrangement of urban elements, such as city blocks and green spaces (Grimm et al. 2008). A rapid decline in species richness has been observed when the urban green area is below two hectares, with a significant threshold at one hectare (Arca et al. 2012), suggesting that smaller patches may be less effective in supporting biodiversity.

However, relatively little is known about the potential effect on species that specific urban characteristics such as building typologies, age, or façade composition might have. Studies have yet to explore the relationship between urban organization and biodiversity, and thus far they have not attempted to assess the ability of various urban forms to sustain and potentially promote flora and fauna within cities (Flégeau et al. 2021).

Birds can either benefit from or be negatively impacted by human-made structures and potential dangers include tall buildings which can lead to bird collisions and fatalities (Chen et al 2024). However, certain architectural elements can provide habitats or places for perching and nesting, which contribute to the increase of bird populations in urban areas (Murgui and Hedblom 2017). The relationship between birds and urban configurations—and their success within these environments—largely depends on the species’ habits. Insectivorous birds, for example, tend to inhabit intact patches which are highly connected, while omnivorous birds appear to better adapt to the fragmentation caused by urbanization (Wu et al. 2024). Additionally, a positive correlation is found between bird species richness and the size of green spaces, although factors such as edge density and the presence of roads negatively affect the different feeding guilds of birds (Wu et al. 2024). Finally, increased urbanization has been shown to result in decreased nest predation (Ryder et al. 2010).

This study aims to further explore the influence of urban configurations on bird communities. The research addresses this gap by investigating how different urban layouts can affect the presence of birds, classified according to their trophic and nesting ecology. The main objective is to identify any possible differences between specific urban configurations in relation to species richness and individual abundance, and to understand how these differences influence biodiversity. Citizen science is employed as a crucial methodology for the observation and tracking of species.

The proposed urban configurations are the historic centre (HC), the open block (OB) (Carpio-Pinedo 2014), and the closed block (CB) (López 2003). The buildings featured in these configurations display different architectural characteristics which influence the presence of birds. According to preliminary findings, due to their age historic centres provide better indicators of individual density than more modern urban areas. Similarly, a lower presence of individual birds is expected in closed-block configurations due to the limited connectivity and reduced habitat availability resulting from higher urban density. Indicators such as the absence of water sources, the presence of noise, traffic, and pollution also contribute to the absence of urban nesting birds.

Methodology

The methodology was based on the work of Li et al. (2019), combining an urban habitat classification scheme with data from a citizen science program, in this case, from SEO/BirdLife (‘Common Breeding Bird Monitoring,’ SACRE). This method consisted of three steps (Fig. 1). The first step involved the description of the urban configuration, based on cadastral data and open information sources. The second step consisted in the processing of data from the SACRE program, while the third analysed both data sets in order to explore relationships between urban and biological variables. A detailed explanation of these three steps can be found in the following sections.

Step 1: Establishing the study area and urban composition

The central urban area of the city of Valencia, with a size of 63.98 km2 (Fig. 2), has been selected for several reasons. The city is located on the Mediterranean coast, a geographical region identified as one of the most vulnerable in Europe in terms of biodiversity loss and the adverse effects of climate change (Salvia et al. 2021). Valencia, which has been designated the European Green Capital for 2024, is the first Mediterranean city to receive this recognition. The city displays a variety of urban spaces, making it an ideal example for the study model. Additionally, this selection of a city from the Mediterranean basin is expected to aid extrapolation of the study to others with similar climates in future research (Csa climate according to the Köppen–Geiger classification).

The analysis of urban components enables the identification of local particularities in the development of a city (Hermosilla et al. 2014). There are numerous methods for classifying urban configurations, which—depending on their analytical focus—can be broadly divided into qualitative and quantitative approaches (Fleischmann et al. 2022). Quantitative methods can be applied at various scales, including buildings, streets (Guyot et al. 2021; Araldi and Fusco 2019; Hermosilla et al. 2014), and neighbourhood (Soman et al. 2020). In this study, a quantitative approach using 500 × 500 m grids follows the general methodology employed by Ibáñez-Álamo et al. (2024) to contrast urban characteristics with bird presence. For this study the Spanish Inspire Cadastral Downloader was the data source used to obtain information about the building stocks.

The data on bird presence and abundance from the citizen science program SACRE (detailed below) were collected at sampling points distributed irregularly throughout the city. Given that this irregular design is overlaid with a 500 × 500 m grid, not all grid cells contain bird sampling points. For this study, we identified the grid cells with at least three points where SACRE censuses were conducted within the cell, and from these, five cells were selected at random from each of the three urban configurations (Fig. 3). Thus, this work includes 15 grid cells or sampling units (hereafter referred to as “SU”). Various indicators were chosen (Table 1; see source and calculation details in Table S1) and applied to two SUs from each urban configuration to describe the characteristics of each of the three urban configurations.

There are many ways to define urban fabrics and configurations. However, given the interest of this research and based on other explorations (Flégeau et al. 2021), we decided to classify the sampling units (SUs) according to their type of urban configuration: HC, OB, and CB. Urban fabrics are easily identified through planimetry. HCs are characterized by their dense urban form and large numbers of buildings constructed before 1920, with narrow streets. The OB fabrics consist of independent buildings with separate façades, surrounded by open spaces such as gardens or green areas. The CB fabrics are formed by buildings surrounding a shared internal area. Each urban configuration includes a study of its building stock, also detailed in Table S2, which outlines the years of construction and key characteristics of the buildings, as established by other authors (Mestre 2008; Llopis and Ortolá 2000).

Step 2: Data collection

The data were collected within the framework of the citizen science project SACRE, ‘Monitoring of Common Breeding Birds,’ developed by the Spanish Ornithological Society (SEO/BirdLife). With the assistance of volunteer citizens, the project conducts surveys with ten census points, avoiding overlaps between points. In built-up areas, the separation between census points can be up to two blocks. The census points are found in areas with homogeneous habitat, avoiding edges between different habitats. For instance, in an urban environment, points along the boundary between parks and residential areas are avoided.

At each census point, the birds detected (either seen or heard) are recorded over a 5-min period within a radius of 25 m. Each spring, the individual sampling points are visited on two occasions, the first between April 15 and May 15 and the second between May 15 and June 15, maintaining an interval of approximately four weeks between visits to the same point (Ralph et al. 1995; Bibby et al. 2000). The guidelines for performing this type of census state literally “All observations, whether isolated birds or flocks, should be recorded, in the latter case noting the estimated number of birds in the flock” (SEO/BirdLife 2016). It is hoped that the replicates carried out in each sampling unit and the two censuses carried out per season will dilute the possible effects of the chance detection of wandering individuals or the possible biases of gregarious species that may appear overabundant in some places. Due to logistical issues, for some points only one of the two annual visits may have been recorded. Sampling occurs in the morning from dawn until 11:00 a.m. or in the afternoons during the hours leading up to dusk.

Although the SACRE project has been in operation in the city of Valencia since 2010, the number and location of the surveys have varied significantly. For this study, we selected the data from 2019, which provides the highest number of sampling points and the best spatial distribution for the objectives of this work.

Step 3: Data selection and classification and statistical analysis

To correlate the data on the presence and abundance of different bird species with the proposed urban configurations, an initial analysis of the five most abundant bird species was attempted independently. However, the collected data were insufficient for relevant statistical analysis. This work considers all species detected in at least one of the surveys at any of the points. Based on these data and following the methodology used in previous studies (Máthé and Batár 2015), we selected birds feeding or nesting in urban environments (Table S3), excluding incidental species.

Secondly, the bird species detected were classified according to their nesting and trophic ecology (SEO/BirdLife 2024a, 2024b; SEO/BirdLife 2021) (Table 2). Four nesting categories were considered for the species found in this study: in buildings, in trees, in shrubs, and on the ground. Ground-nesting species were omitted in some analyses due to their scarcity and the limited data available on them. For trophic ecology, four groups were considered: species that feed in the air, those that feed in shrubs, and those that feed in trees and shrubs. In the case of species that can nest or feed in more than one of these locations, the option cited as the most frequent was selected (Table 2).

In addressing the statistical analyses, the data are organized hierarchically, bearing in mind that these data are obtained through censuses conducted in different grids, which are in turn covered in various urban configurations. This hierarchy implies that two censuses conducted within the same grid can be considered independently; however, when comparing different urban configurations (technically speaking, the censuses are conditionally independent, conditioned by the grid variable, but not unconditionally dependent) these two censuses should not be assumed to be independent of each other.

Generalized Linear Mixed Models (GLMMs) were used in this analysis in order to identify any differences between the three selected urban configurations in terms of species richness, individual abundance, and diversity. This allows us to appropriately model the dependency between censuses conducted in a single grid while estimating the variability between grids within the same urban configuration. For numerical calculations, we used the R library lmer4 (Bates et al. 2015).

These GLMMs provide a more detailed representation, including the urban category as a “fixed effect,” while the variability between grids is modelled as a “random effect.” The results of the models include (a) an estimated average of the dependent variable based on the urban category for a random grid of that category, and (b) the variability between grids belonging to the same urban category.

A distinct GLMM was selected and estimated for each of the following variables:

-

– General abundance of individuals.

-

– Abundance of individuals by type of feeding.

-

– Abundance of individuals by type of nesting.

-

– Shannon diversity index.

For the first four points, the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) was applied to compare the fit of different probability distributions (Poisson, binomial, and negative binomial). In the case of the Shannon index, a Gaussian distribution was initially assumed. In all cases, the suitability of the models selected was verified using the residual diagnostics calculated with R DHARMa (Hartig 2022). The link functions used for the different probability distributions are the natural ones, namely f(x) = log(x) for the Poisson and Negative Binomial distribution, f(x) = x for the Gaussian distribution, and f(x) = logit(x) for the Binomial distribution.

Finally, the estimates of means and variances of the different models were examined. To establish whether the differences between urban configurations are statistically significant, the p-values of the t-tests associated with the relevant contrasts were calculated and adjusted using the Tukey method to account for multiple comparisons (three), and p-values smaller than 5% were considered as statistically significant; these calculations were performed by means of the R package R emmeans (Lenth 2024). The confidence intervals for model parameters were also computed using the same software.On the other hand, to assess the heterogeneity of the urban configuration in terms of species richness, α, β and γ diversity indices were calculated for the three configurations (HC, OB, and CB) (Begon and Colin 2021). For this purpose, data from three censuses per grid were included in the analysis, covering a total of four grids per urban configuration for the first half of the breeding period, and a total of five grids per configuration for the second half, to ensure an equitable sampling effort across configurations and periods.

Results

Urban composition

Table 3 presents the environmental, urban, and building composition indicators for the six grids (two for each type of urban configuration) selected. The HC configurations stand out for having good air quality, a compact space layout, high noise levels, narrower streets, old low-rise buildings, and a low percentage of sidewalks. The OB configurations have medium noise and traffic levels, a lower percentage of built area, and taller buildings than the other configurations. CB configurations present high noise levels, low and tall vegetation, a greater presence of streets, and a higher number of modern post-1950 buildings.

In the total study area, there are 36,328 buildings. Of these, 26% were built between 1960 and 1975, the period with the highest level of construction activity (Fig. 4), and the OB configuration falls within this range. The HC configurations contain buildings which were constructed before 1920 and form part of the historic centre (Fig. 5). The CB configurations include buildings constructed between 1954 and 1975.

Richness and species diversity

In total, 23 species were recorded (Table 4), all of which were present in previous studies of the city of Valencia (Murgui 2021). In the historic centre, 13 out of the 23 total species were recorded; 21 in the open block configuration; and 20 in the closed block configuration (Fig. 6). Of the 23 species, 12 were present in all three types of urban configuration. The OB and CB configurations shared seven species. The HC is the only configuration where the red-masked parakeet, an exotic species originating from Ecuador and Peru, was recorded (Fierro-Calderón, E and Fierro-Calderón 2020). Additionally, the CB configuration is the only one where individual rose-ringed parakeets, an invasive species, were recorded (Çalışkan 2018). In contrast, the common chaffinch and Sardinian warbler were only found in the OB configuration. No statistical differences in species richness were found between urban configurations (Table S5).

Three intersecting circles represent the OB, HC, and CB urban configurations. Species common to all configurations are placed in the central overlap, those shared by two configurations in the pairwise intersections, and species unique to one configuration in the non-overlapping areas. *Species with fewer than two individuals surveyed

The Shannon Index was 1.04 (0.64–1.22) in HC, 1.25 (0.87–1.63) in OB and 1.48 (1.05–1.90) in CB in the first part of the breeding period, and 0.84 (0.44–1.25) in HC, 1.5 (0.75–1.54) in OB and 1.30 (0.89–1.70) in CB) in the second part, with none of the differences being significant.

The α and β indices (Table 5) are higher in CB than in the other urban configurations in both the first and second half of the breeding period. The lowest values were obtained for HC.

General abundance of birds

Overall, the most abundant species (> 5% of the total individuals on either of the two visits) were the swift, the rock pigeon, the house sparrow, and the Eurasian collared dove, which together accounted for 83% of the individuals detected on the first visit and 86% on the second. The number of swifts is significantly higher compared to the other species, especially in the second half of the breeding period, when they account for nearly 50% of the total individuals found. Throughout the breeding period they are much more plentiful in the historic centre than in the other urban configurations. In keeping with this, the rock pigeon exhibits the same pattern, particularly during the first half of the breeding period. During the first half of the breeding period the house sparrow is the third most abundant species, falling to fourth position during the second half, when similar abundance is found across all three configurations. The Eurasian collared dove is the fourth most abundant species during the first half of the breeding season and the third most abundant during the second half.

As Fig. 7 shows, the number of individuals detected per census differs between the various urban configurations and is higher in the historic centre. This difference, which is identified in both periods of the breeding season (Table S5), is significant between HC and OB.

Abundance of birds according to their foraging location

A large number of birds using shrubs as a food source was observed both on visit 1 and visit 2 (Table S5). A significant number of birds that capture their prey in flight was also found, while those that primarily feed in tree canopies and shrubs were less common.

In the historic centre (HC), individuals that feed in the air are more abundant (Table S4, Fig. 8), and a statistically significant difference is observed between HC and open block (OB) throughout the breeding period (Table S5). The variability between quadrants of the same configuration is high, especially in the first half of the breeding period (Table S6).

Although the number of individuals that feed in trees and shrubs is greater in the closed block (CB) urban configuration than in the historic centre (HC) and open block (OB) configurations, only the difference between CB and HC during the first half of the breeding period is marginally significant (Table S5). There are no statistically significant differences between urban configurations regarding the abundance of birds that feed in shrubs at any stage of the breeding period (Table S6).

Abundance of birds according to their nesting sites

In terms of nesting habits, higher numbers of birds using artificial structures are revealed, followed by those that nest in trees. Since only one species was recorded nesting on the ground, and the number of individuals was very low, this species will not be included in the statistical analyses. The abundance of birds nesting in buildings is greater in the historic centre (HC) than in the other two urban configurations (Fig. 9, Table S5), while the difference between HC and open block (OB) is statistically significant throughout the breeding period and the difference between HC and closed block (CB) is statistically significant only during the second half of the breeding period (Table S5).

We note that it is very likely that the standard deviation of the data corresponding to the second half of the breeding period is not well estimated. It seems that the model of best fit indicates that the variance between quadrilaterals of the same configuration approaches zero, suggesting that we do not have sufficient data to estimate this standard deviation. For the other nesting sites, no significant differences have been found between urban configurations.

The influence of the common swift

Results obtained are probably biased by the large number of swifts counted compared to the rest of the species, with results showing a higher number of swifts in the historic centre (HC) than in the other urban configurations. In order to confirm this, the models were applied to the dataset from visit 2, both with and without swifts. The results obtained only with swifts are very similar to the results presented earlier (Fig. 10, Table S5, and Table S6). Furthermore, the results obtained without swifts do not show significant differences between urban configurations.

Discussion

In terms of urban characteristics, HC configurations stand out for having good air quality, a compact space configuration, a high noise index, narrower streets, low-rise buildings constructed before 1920, and a low percentage of sidewalks. In contrast, OB configurations exhibit a medium noise and traffic level, a lower percentage of built-up area, and taller buildings compared to the other configurations. Finally, CB configurations are characterized by a high noise index, vegetation of varying heights (both low and high), and a greater presence of streets and buildings constructed after 1950.

With respect to avian fauna composition, 23 species were found in total. The CB and OB configurations, together, harbor 22 of the 23 total species recorded. In the HC configuration, only 13 species were recorded, 12 of which are shared with the other two configurations. All the species registered could be considered urban exploiters due their thrive in city environments (Palacio 2020). The relationship between bird species and each type of urban configuration is discussed in more detail below.

Birds of the OB urban configuration

Twenty-one of the 23 total species were recorded, making it the urban configuration with a relatively high diversity and species richness. Many of these birds are granivorous, insectivorous and frugivorous/insectivorous, thus showing a broader dietary niches than urban avoiders (Palacio 2020). Among the most abundant in the sampling units are: rock pigeon, black starling, house sparrow and turtle dove, which are numerous in various urban areas. In this urban category, the barn swallow tends to be more frequent than in the other urban configurations, as these birds require open spaces to fly and forage for insects (Murgui and Hedblom 2017). Such spaces are well provided in open block configurations, which favour the presence of insectivorous birds (Sánchez-Sotomayor et al. 2023).

Our results are consistent with other studies conducted in urban environments, where they found that the dispersed urbanization of open blocks favours the expansion of tree-nesting species with a broad trophic niche (Leveau 2005). The detection of two chaffinches in our study area underlines the importance of these wooded areas, which simulate the conditions of their natural wooded habitats (Recuerda et al. 2023).

Birds of the HC urban configuration

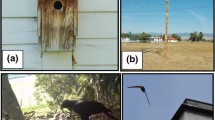

Thirteen of the 23 total species were recorded in this urban configuration. It is the configuration with the lowest species richness but the highest abundance of birds. It is also where there is the highest abundance of birds nesting on buildings. We observed that birds that feed in the air, such as swifts and common planes, are concentrated in areas with old and medium height buildings, such as the HC sampling units E6, F6 and F7.

This concentration of building-nesting birds may be because old buildings, in particular, offer multiple opportunities for nesting (Guyot et al. 2021). In our case, the distribution of birds nesting in buildings is similar to that of those that feed in the air and these are mainly common planes and swifts. This is because they need to feed close to the nest site. It is also the only configuration where red-masked parakeets were recorded. Their presence in Spain is attributed to domestic pets which escaped from their cages (Murgui 2001).

Other studies have shown that architectural design and vegetation significantly influence species diversity, both for nesting and feeding (Murgui and Hedblom 2017). Species such as rock dove and house sparrow have shown a remarkable ability to adapt to dense urban environments (Bernat-Ponce et al. 2018) such as historic centres, hence their abundance in the study.

Birds of the CB urban configuration

With 20 different species detected, this configuration holds the highest richness, and also the highest α diversity. The enclosed structure of this type of urban configuration also provides suitable nesting habitats. Birds nesting in these areas include the rock pigeon, black starling, and house sparrow.

However, it is important to note that modern buildings often do not provide suitable nesting sites, which could limit opportunities for these species (Grünwald et al. 2024). This is the only category where individual rose-ringed parakeets were recorded in the first and second breeding periods.

The presence of omnivorous birds, such as the house sparrow, may be due to their tolerance to human disturbance, which allows them to exploit waste in urban environments and better adapt to urbanization. However, the house sparrow has experienced a marked decline in other cities in the United Kingdom and several Western European countries. This decline could be related to socioeconomic change. According to Shawn et al. (2008), these environmental transformations in more affluent areas appear to negatively impact sparrow survival by affecting their nesting success, foraging opportunities, and predation risk. Although our study did not directly assess this aspect, it is possible that the presence of these species in urban environments is linked to their ability to take advantage of anthropogenic resources.

Our findings suggest that in urban CB settings there are higher numbers of birds feeding in trees and shrubs, indicating that green areas play an important role in these environments. Individuals of certain species have been observed to feed in the air especially in areas where there are buildings constructed between 1939 and 1959 and arranged in half-height linear blocks.

The greater presence of individuals feeding on trees and shrubs in CB configurations, compared to HC, can be explained by the trophic ecology of the species and the structure of both configurations. While open and green spaces are scarce in HCs, the CB structure provides greater refuge when it is surrounded by green areas. These findings are consistent with research highlighting landscape heterogeneity as a fundamental factor for bird diversity (Murgui and Hedblom 2017; Callaghan et al. 2019).Query

The rose-ringed parakeet has established populations in numerous countries, thriving in urban areas due to suitable nesting conditions in building structures and the presence of exotic plants (Butler 2003). While some sources suggest a lack of predators in urban environments, recent studies challenge this view. For example, research has documented the presence of syntopic cavity-nesting birds (Dodaro et al. 2014), indicating potential competition for nesting sites. Like red masked parakeets found in HCs, populations of this species are the result of accidental and deliberate bird escapes (Souviron-Priego et al. 2018).

The particular case of the swift and the low representativeness of other species

The common swift is the species that caused the significant differences between urban configurations, as it recorded 306 individuals in the first half of the breeding season and 657 during the second, with the highest numbers found in the HC. This pattern is similar to that of birds nesting in buildings, but it is also connected to the fact that swifts are migratory and return to the same nest every year (Akesson et al. 2020). Some studies have already associated this species with historical structures such as walls (Corrales et al. 2013) and buildings in ancient cities (Dulisz et al. 2022).

A key factor is the conservation status of the historic centre in Valencia, which still preserves many type A and B buildings (Table S2) that have not been renovated, leaving gaps that allow this species to nest (see Fig. 4). The centre is also directly connected to an urban green area, the second factor influencing the species' abundance. Among all the urban indicators used in the study, building age stands out as a determining factor for species that feed in the air and nest in buildings.

The common swift has experienced a 27.2% decline over the last 22 years (1998–2020), which led to its designation as Bird of the Year in 2021 to promote protective measures (SEO/BirdLife 2021). Additionally, population declines have been observed in other European countries, and these are thought to be partly linked to modern construction techniques that reduce the availability of suitable nesting sites for swifts and other birds (Schaub et al. 2019). Typically, historic centres are subject to regulations requiring conservation, and in Valencia, the centre has been designated as a Comprehensive Rehabilitation Area. However, current regulations do not grant protected status to this species.

Conclusions

Significant differences have been found between urban configurations regarding species richness and individual abundance, and relevant differences in α and β diversity were also found. The results partially confirm the initial hypotheses. It is demonstrated that the historic centre (HC), due to its age and proximity to urban green areas, indeed presents a higher density of birds, especially those that feed in the air and nest in buildings, such as swifts and house martins. Regarding species richness, only 13 of the total 23 species were recorded, which may indicate signs of habitat homogenization. This is also supported by the relatively low α and β diversity indices. On the other hand, the hypothesis regarding the lower presence of individuals in closed block configurations is also confirmed, as the high density of urbanization and construction limits connectivity and reduces habitat availability.

However, it is important to note that both species richness and overall diversity are higher in open and closed blocks than in the historical centre. The absence of species such as the European Robin, the Great Tit, and the Sardinian Warbler, along with the lower number of species count in the historical centre suggests that open and closed blocks provide a greater variety of habitats and breeding opportunities. Nevertheless, this pattern should be interpreted within the broader context of urban avifauna homogenization. As Meffert and Dziock (2013) point out, the urban matrix plays a key role in this process by filtering certain species traits while favoring others. Murthy et al. (2016) further support this idea, highlighting that the increased presence of widespread species in cities and the reduced variation in relative abundances across urban sites contribute to the homogenization of avian communities. This indicates that, while some urban areas may exhibit higher diversity than others, the overall trend in urban environments is toward a more uniform and less diverse species composition compared to natural habitats.

The current study has some limitations. These results could be influenced by the inherent constraints of citizen science. First, the SACRE program relies on volunteers, which introduces variability in effort and skills among participants. Second, different points have been sampled each year, which limited this work to a single year where the number of censuses was sufficient to conduct some analyses reasonably. Third, even within the selected year, there are points that were not sampled during the two planned census periods, making it necessary to divide the analysis into periods, thus preventing a more comprehensive view. These limitations are inherent to citizen science programs.

To enhance the potential of citizen science initiatives, coordinating organizations should ensure the continuity of a critical number of volunteers to maintain a database that is as consistent and reliable as possible. The fourth limitation is that the grids overlaid for the study of urban configurations were independent of the design of the bird censuses. This resulted in not all grids having sufficient census points, even in the year with the highest count. Although we made a random selection among the possible ones (those with at least three census points inside), the selection was not random among all of the grids. Since volunteers choose their census routes, it is not possible to know the extent to which the grids with censuses are a random sample of those available in the city.

These findings were made in Valencia, European Green Capital 2024, and are influenced by its specific configuration. However, the relationships established may differ in other cities due to factors such as land use, the number of green areas, climate, and other environmental and urban aspects (Ibáñez-Álamo et al. 2024). Therefore, it will be necessary to conduct studies at this level of detail in other cities, considering the series of urban and environmental indicators employed in this study, as these may be determining factors when correlating species abundance/richness in the urban configurations of a given geographical region.

Given the decline of the common swift and its relationship with the lack of suitable nesting sites in modern buildings, SEO/Birdlife is already working to ensure that regulations include the creation of specific nesting spaces in new construction projects and building renovations, guaranteeing the installation of nest boxes or preserving structures to prevent the decline of this species.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript and supplementary information files.

References

Adams BJ, Li E, Bahlai CA, Meineke EK, McGlynn TP, Brown BV (2020) Local-and landscape-scale variables shape insect diversity in an urban biodiversity hot spot. Ecol Appl 30(4):e02089. https://doi.org/10.1002/eap.2089

Åkesson S, Atkinson PW, Bermejo A, de la Puente J, Ferri M, Hewson CM, Hedenström A (2020) Evolution of chain migration in an aerial insectivorous bird, the common swift Apus apus. Evolution 74(10):2377–2391. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.14093

AQI Project (2024). Real-time Air Quality Index (AQI) https://aqicn.org/city/algeria/algiers/us-embassy/es/

Araldi A, Fusco G (2019) From the street to the metropolitan region: pedestrian perspective in urban fabric analysis. Environ Plan b: Urban Anal City Sci 46(7):1243–1263. https://doi.org/10.1177/239980831983

Arca E, Battisti C, Fraticelli F (2012) Area-effect in breeding bird communities occurring in an archipelago of urban holm oak fragments (Rome, Central Italy). Vie Et Milieu-Life and enVironment 62(4):159–164

Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker B, Walker S (2015) Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J Stat Softw 67(1):1–48. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01

Begon M, Colin R (2021) Ecology: from individuals to ecosystems. Wiley Blackwell, Hoboken

Bernat-Ponce E, Gil-Delgado JA, Guijarro D (2018) Factors affecting the abundance of House Sparrows Passer domesticus in urban areas of southeast of Spain. Bird Study 65(3):404–416. https://doi.org/10.1080/00063657.2018.1518403

Bibby CJ, Burgess ND, Hill DA, Mustoe SH (2000) Bird Census Techniques. Academic Press, California

Butler CJ (2003). Population biology of the introduced rose-ringed parakeet Psittacula krameri in the UK (Doctoral dissertation, University of Oxford)

Çalışkan ONUR (2018) Rose-ringed parakeets (Psittacula krameri) and geographical evaluation of habitats in Turkey. Marmara Geograph Rev 38:279–294

Callaghan CT, Bino G, Major RE, Martin JM, Lyons MB, Kingsford RT (2019) Heterogeneous urban green areas are bird diversity hotspots: insights using continental-scale citizen science data. Landsc Ecol 34:1231–1246. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-019-00851-6

Callaghan CT, Poore AG, Major RE, Cornwell WK, Wilshire JH, Lyons MB (2021) How to build a biodiverse city: environmental determinants of bird diversity within and among 1581 cities. Biodivers Conserv 30:217–234. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-020-02088-1

Cao Y, Li G, Huang Y (2023) Spatiotemporal evolution of residential exposure to green space in Beijing. Remote Sens 15(6):1549. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs15061549

Carpio Pinedo J (2014) La manzana abierta de Portzamparc como tipología para el paisaje urbano contemporáneo. Planur-e, (3)

Chen K, Kross SM, Parkins K, Seewagen C, Farnsworth A, Van Doren BM (2024) Heavy migration traffic and bad weather are a dangerous combination: bird collisions in New York city. J Appl Ecol 61(4):784–796. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.14590

Corrales L, Bautista LM, Santamaría T, Mas P (2013) Hole selection by nesting swifts in medieval city-walls of central Spain. Ardeola 60(2):291–304. https://doi.org/10.13157/arla.60.2.2013.291

Cristaldi MA, Godoy IN, Leveau LM (2023) Responses of urban bird assemblages to land-sparing and land-sharing development styles in two Argentinian cities. Animals 13(5):894. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani13050894

Das M, Inácio M, Das A, Barcelo D, Pereira P (2024) Mapping and assessment of ecosystem health in the Vilnius functional zone (Lithuania). Sci Total Environ 912:168891. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.168891

Dobbs C, Nitschke C, Kendal D (2017) Evaluación de los factores que configuran los patrones globales de la estructura del paisaje de la vegetación urbana. Sci Total Environ 592:171–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.03.05

Dodaro G, & Battisti C (2014) Rose-ringed parakeet (Psittacula krameri) and starling (Sturnus vulgaris) syntopics in a Mediterranean urban park: evidence for competition in nest-site selection?. Belgian J Zoology 144(1)

Dulisz B, Stawicka AM, Knozowski P, Diserens TA, Nowakowski JJ (2022) Effectiveness of using nest boxes as a form of bird protection after building modernization. Biodiv Conserv. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-021-02334-0

Fariha JN, Miah MT, Limon ZA, Alsulamy S, Kafy AA, Rahman SN (2024) Quantifying spatial dynamics of urban sprawl for climate resilience sustainable natural resource management by utilizing geostatistical and remote sensing techniques. Theor Appl Climatol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00704-024-05000-x

Fierro-Calderón E, Fierro-Calderón K (2020) First record of Psittacara erythrogenys (Psittacidae) in Colombia. Caldasia 42(2):347–349. https://doi.org/10.15446/caldasia.v42n2.78897

Flégeau M, Soubelet H, Carré S, Barot S, Lagurgue X, Bognon S, Clergeau P (2021) What evidence exists on the possible effects of urban forms on terrestrial biodiversity in western cities? A systematic map protocol. Environ Evid 10(1):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13750-021-00243-x

Fleischmann M, Feliciotti A, Romice O, Porta S (2022) Methodological foundation of a numerical taxonomy of urban form. Environ Plan b: Urban Anal City Sci 49(4):1283–1299. https://doi.org/10.1177/23998083211059835

Grimm NB, Faeth SH, Golubiewski NE, Redman CL, Wu J, Bai X, Briggs JM (2008) Global change and the ecology of cities. Science 319(5864):756–760. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.115019

Grünwald J, Auniņš A, Brambilla M, Escandell V, Eskildsen DP, Chodkiewicz T, Reif J (2024) Ecological traits predict population trends of urban birds in Europe. Ecolo Indic 160:111926. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2024.111926

Guyot M, Araldi A, Fusco G, Thomas I (2021) The urban form of Brussels from the street perspective: the role of vegetation in the definition of the urban fabric. Landsc Urban Plan 205:103947. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2020.103947

Hartig F (2022). DHARMa: Residual Diagnostics for Hierarchical (Multi-Level / Mixed) Regression Models. R package version 0.4.6, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=DHARMa

Hermosilla T et al (2014) Using street based metrics to characterize urban typologies. Comput Environ Urban Syst 44:68–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compenvurbsys.2013.12.002

Huang P, Zheng D, Yan Y, Xu W, Zhao Y, Huang Z, Fu W (2022) Effects of landscape features on bird community in winter urban parks. Animals 12(23):3442. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12233442

Huang BX, Li WY, Ma WJ, Xiao H (2023) Space accessibility and equity of urban green space. Land 12(4):766. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12040766

Ibáñez-Álamo JD, Izquierdo L, Mourocq E, Benedetti Y, Kaisanlahti-Jokimäki ML, Jokimäki J, Díaz M (2024) Urban landscape organization is associated with species-specific traits in European birds. Sci Total Environ 908:167937. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.167937

Khiali-Miab A, Grêt-Regamey A, Axhausen KW, van Strien MJ (2022) A network optimisation approach to identify trade-offs between socio-economic and ecological objectives for regional integrated planning. City Environ Interact 13:100078. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cacint.2021.100078

Lenth R (2024). emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, aka Least-Squares Means. R package version 1.10.3, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=emmeans

Leveau CM, Leveau LM (2005) Avian community response to urbanization in the Pampean region, Argentina. Ornitol Neotrop 16:503–510

Li E, Parker SS, Pauly GB, Randall JM, Brown BV, Cohen BS (2019) An urban biodiversity assessment framework that combines an urban habitat classification scheme and citizen science data. Front Ecol Evol 7:277. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2019.00277

Llopis A, Ortolá SD (2000). Arquitectura del siglo XX en Valencia. Institució Alfons el Magnànim

López de Lucio, Ramón. (2003). De la manzana cerrada al bloque abierto”. En el libro “Un siglo de Vivienda Social en España, 1903–2003”, Ed. Ayuntamiento de Madrid/ Ministerio de Fomento

Máthé O, Batáry P (2015) Insectivorous and open-cup nester bird species suffer the most from urbanization. Bird Study 62(1):78–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/00063657.2014.1000262

Meffert PJ, Dziock F (2013) The influence of urbanisation on diversity and trait composition of birds. Landscape Ecol 28:943–957. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-013-9867-z

Mestre Martí M (2008). La arquitectura del modernismo valenciano en relación con el Jugendstil vienés. 1898–1918. Paralelismos y conexiones (Doctoral dissertation, Universitat Politècnica de València)

Murgui E (2001) Factors influencing the distribution of exotic bird species in Comunidad Valenciana (Spain). Ardeola 48(2):149–160

Murgui E, Hedblom M (2017) Ecology and conservation of birds in urban environments. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-43314-1

Murgui E (2021) Atlas de las aves reproductoras e invernantes de València. Ayuntamiento de València

Murthy AC, Fristoe TS, Burger JR (2016) Homogenizing effects of cities on North American winter bird diversity. Ecosphere 7(1):e01216. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.1216

Palacio FX (2020) Urban exploiters have broader dietary niches than urban avoiders. Ibis 162(1):42–49. https://doi.org/10.1111/ibi.12732

Paniagua-Villada C, Garizábal-Carmona JA, Martínez-Arias VM, Mancera-Rodríguez NJ (2024) Built vs. Green cover: an unequal struggle for urban space in Medellín (Colombia). Urban Ecosyst. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11252-023-01443-8

Rahimi-Ardabili H, Astell-Burt T, Nguyen PY, Zhang J, Jiang Y, Dong GH, Feng X (2021) Green space and health in mainland China: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(18):9937. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189937

Ralph CJ, Droege S, Sauer JR (1995) Monitoring Bird Populations by Point Counts. USDA Forest Service.

Recuerda M, Palacios M, Frías O, Hobson K, Nabholz B, Blanco G, Milá B (2023) Adaptive phenotypic and genomic divergence in the common chaffinch (Fringilla coelebs) following niche expansion within a small oceanic island. J Evol Biol 36(9):1226–1241. https://doi.org/10.1111/jeb.14200

Ryder TB, Reitsma R, Evans B, Marra PP (2010) Quantifying avian nest survival along an urbanization gradient using citizen-and scientist-generated data. Ecol Appl 20(2):419–426. https://doi.org/10.1890/09-0040.1

Salvia M, Olazabal M, Fokaides PA, Tardieu L, Simoes SG, Geneletti D, Reckien D (2021) Climate mitigation in the Mediterranean Europe: an assessment of regional and city-level plans. J Environ Manag 295:113146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.113146

Sánchez-Sotomayor D, Martín-Higuera A, Gil-Delgado JA, Gálvez Á, Bernat-Ponce E (2023) Artificial grass in parks as a potential new threat for urban bird communities. Bird Conserv Int 33:e16. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0959270922000119

Santos EG, Wiederhecker HC, Pompermaier VT, Schirmer SC, Gainsbury AM, Marini MÂ (2024) Are acoustic indices useful for monitoring urban biodiversity? Urban Ecosyst. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11252-024-01567-5

Schaub T, Wellbrock AH, Rozman J, Witte K (2019) Light data from geolocation reveal patterns of nest visit frequency and suitable conditions for efficient nest site monitoring in common swifts apus apus. Bird Study 66(4):519–530. https://doi.org/10.1080/00063657.2020.1732862

SEO/BirdLife (2016) Instrucciones de SACRE urbano. https://seo.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/instrucciones-sacre-urbano.pdf

SEO/BirdLife (2021) Tras la votación popular puesta en marcha por SEO/BirdLife para decidir la especie bandera de este año, la ganadora ha resultado ser esta ave frecuente en entornos urbanos con el 49.58 %. SEO/BirdLife. https://seo.org/el-vencejo-comun-es-el-ave-del-ano-2021/

SEO/BirdLife (2024) III Atlas de las aves en época de reproducción en España. https://atlasaves.seo.org/

SEO/BirdLife (2024) Guía de aves. https://seo.org/guia-de-aves/

Seto KC, Güneralp B, Hutyra LR (2012) Global forecasts of urban expansion to 2030 and direct impacts on biodiversity and carbon pools. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109(40):16083–16088. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1211658109

Shaw LM, Chamberlain D, Evans M (2008) The House Sparrow Passer domesticus in urban areas: reviewing a possible link between post-decline distribution and human socioeconomic status. J Ornithol 149(3):293–299. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-008-0285-y

Soman S, Beukes A, Nederhood C, Marchio N, Bettencourt LM (2020) Worldwide detection of informal settlements via topological analysis of crowdsourced digital maps. ISPRS Int J Geo Inf 9(11):685. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi9110685

Souviron-Priego L, Muñoz AR, Olivero J, Vargas JM, Fa JE (2018) The legal international wildlife trade favours invasive species establishment: the monk and ring-necked parakeets in Spain. Ardeola 65(2):233–246. https://doi.org/10.13157/arla.65.2.2018.ra3

Toffoli R, Cucco M (2020) Habitat suitability, connection analysis and effectiveness of protected areas for conservation of the barbastelle bat Barbastella barbastellus in NW Italy. Acta Chiropterologica 22(2):271–281. https://doi.org/10.3161/15081109ACC2020.22.2.004

Ajuntament de València (2017) Mapa estratégico de ruido de Valencia. https://sicaweb.cedex.es/docs/mapas/fase3/aglomeracion/VALENCIA/Resumen_VALENCIA_MER%202017.pdf

Vargas-Hernández JG, Zdunek-Wielgołaska J (2021) Urban green infrastructure as a tool for controlling the resilience of urban sprawl. Environ Dev Sustain 23(2):1335–1354. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11252-023-01452-7

Winarni NL, Nuruliawati N, Anugra BG, Junaid AR, Widayanti S, Aslan A, Wulandari Y (2023) Can cities provide butterfly-friendly habitats? Biodivers J Biol Divers. https://doi.org/10.13057/biodiv/d240447

Wu R, Zhang Q, Hao Z, Li L, Gao B, Li J, Pei N (2024) Insectivorous birds are more sensitive to urban greenspace changes in Guangzhou city China. Urban Forest Urban Green 94:128243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2024.128243

Xu Y, Li C, Sun Z, Jiang L, & Fang J (2019) Tree height explains stand volume of closed-canopy stands: Evidence from forest inventory data of China. Forest Ecol Management 438:51–56

Yang L, Ho JY, Wong FK, Chang KK, Chan KL, Wong MS, Siu JY (2020) Neighbourhood green space, perceived stress and sleep quality in an urban population. Urban Forest Urban Green 54:126763. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2020.126763

Yang M, Gao X, Siddique KH, Wu P, Zhao X (2023) Spatiotemporal exploration of ecosystem service, urbanization, and their interactive coercing relationship in the yellow river basin over the past 40 years. Sci Total Environ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.159757

Zhang W, Chang WJ, Zhu ZC, Hui Z (2020) Landscape ecological risk assessment of Chinese coastal cities based on land use change. Appl Geogr. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2020.102174

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Juan del Moral González, in charge of the SACRE program of SEO/BirdLife, for the data facilitation. Thanks to the SEO/BirdLife staff Mario Giménez, Anna Valentín and Antonio Castelló for their scientific support with the interpretation of the data and the SACRE methodology. Special mention is also owed to Marta Canales at Universitat Jaume I for her help in collecting the building information. We are also deeply grateful to the anonymous reviewer whose valuable suggestions and sources enabled us to significantly improve the manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature. Universitat Jaume I,PREDOC/2022/027,Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación,Plan de Recuperación,Transformación y Resiliencia,TED2021-130813B-I00,TED2021-130813B-I00,Generalitat Valenciana,CIAICO/2023/082,CIAICO/2023/082,ERA-NET Cofund,EU-AEI,PCI2024-155028-2.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CB: wrote the main manuscript draft. JS and EB: conducted the statistical analysis. EB and JAGE: design and supervise the research. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Communicated by David Hawksworth.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Buenaño-Mariño, C.d.P., Sabán, J., Barba, E. et al. Urban form shapes bird niches: insights from the European green capital 2024. Biodivers Conserv 34, 1857–1879 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-025-03050-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-025-03050-9