Abstract

To adequately examine the impact of job insecurity and unemployment on life satisfaction in the context of increasing de-standardisation of work arrangements, this study distinguishes nuanced forms of perceived job insecurity and unemployment and integrates them into a single scale for employment instability. These forms comprise (1) no perceived job insecurity, (2) some or (3) severe job insecurity, (4) voluntary unemployment, (5) involuntary unemployment, and (6) other reasons for unemployment. Using dyadic data from the German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP) for working-age individuals and their partners, both perceived job insecurity and unemployment lead to decreased life satisfaction, with unemployment having a more pronounced impact on life satisfaction. Involuntary reasons for unemployment are more detrimental to life satisfaction than voluntary reasons. Overall, men suffer more from employment instability than women and their employment instability has a stronger impact on their female spouses’ life satisfaction than vice versa. The results are interpreted through the lens of ‘doing gender’ and ‘gender deviation’ theory.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Employment plays a crucial role in securing people's livelihoods, providing meaning, identity, and strongly influencing individuals’ social participation (Jahoda, 1981). Consequently, past research has extensively documented the detrimental impact of unemployment on other life domains such as family life (Di Nallo et al., 2022; Gonalons-Pons & Gangl, 2021) or health and well-being (Inanc, 2018; Mendolia, 2014). In the scientific literature, employment status has typically been reduced to a simple dichotomy of ‘employed’ versus ‘unemployed’ (Flint et al., 2013; Strandh, 2000), finding that unemployment strongly reduces well-being.

However, this simplified approach fails to account for the increasing diversity within these two categories: Globalization, the expansion of the service sector, and increasing digitalization have considerably changed the labour markets since the end of the last century. This led to an increase in flexible work arrangements, employment instability and an erosion of the male standard employment relationship that was characterized by stable full-time employment at the same employer (Dingeldey & Gerlitz, 2022; Redak et al., 2008). At the same time, women have increasingly entered the labour markets (Dingeldey & Gerlitz, 2022). While some studies have documented an increase in perceived job insecurity during certain periods (Manning & Mazeine, 2022), recent evidence shows a decline in such insecurity in Germany (Clark, 2024; Manning & Mazeine, 2022), suggesting that trends are context-specific and may vary over time. Job insecurity means that individuals fear potential job loss while still employed, which negatively affects their well-being (Kim & von dem Knesebeck, 2016; Klug et al., 2020). However, not only employment but also unemployment needs to be considered in a nuanced way. With the decline of the standard employment relationship, experiences of job loss and unemployment have become more common. In addition, with more women working, dual-earner couples have some flexibility in how they divide paid work and may accommodate periods of either unemployment or inactivity. Therefore, we categorize unemployment by voluntariness (Kassenboehmer & Haisken-DeNew, 2009).

To overcome the dichotomy of ‘employed’ versus ‘unemployed’, it is essential to develop a nuanced indicator integrating various forms of both employment and unemployment. In doing so, this study improves our understanding of the relationship between employment instability and life satisfaction. We refine the subjective component of employment instability into three escalating levels of perceived job insecurity for employed workers—from no worries, indicating stable employment, to some, and finally to severe worries, signifying high anxiety about imminent job loss. Furthermore, we categorize unemployment based on voluntariness, ranging from voluntary causes like resignation, to involuntary causes such as dismissals or plant closures (Kassenboehmer & Haisken-DeNew, 2009). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study using such a fine-grained indicator, which integrates different levels of perceived job insecurity and voluntary and involuntary unemployment. Using such a nuanced indicator provides valuable insights for policymakers and organizations aiming to mitigate the negative impact of employment instability.

Though typically treated as separate strands of literature, some studies have examined perceived job insecurity and unemployment simultaneously. While some have shown stronger negative effects of unemployment on well-being compared to job insecurity (Amick et al., 2002; Flint et al., 2013), others have shown that perceived job insecurity may have a stronger negative impact than actual unemployment (Broom et al., 2006; Burgard et al., 2009; Griep et al., 2016; Kim & von dem Knesebeck, 2016). Notably, individuals experiencing job insecurity may lack institutional support available to the unemployed, such as job search assistance, paid advanced training, money transfers, or severance packages, leading to additional strain on their well-being (Inanc, 2018; Jacobson, 1991). Our nuanced and integrated measure can shed light on the impact of varying levels of employment instability. To better exploit it, we take gender into account and examine possible crossover effects from one partner to the other.

In most countries, men and women face distinct societal role expectations, as suggested by the ‘doing gender’ and ‘gender deviation’ theories (West & Zimmerman, 1987). This is particularly evident in more traditional contexts like Germany, where men have often been expected to be breadwinners, while women have primarily been responsible for caregiving (Scheuring, 2020). In such settings, employment instability tends to have a particularly negative impact on men (Bowman, 2023; Paul & Moser, 2009). However, while employment instability might be more detrimental to men than to women, women might be more affected by their partners’ employment instability (Inanc, 2018; Schatz, 2018). This hypothesis is rooted in the concept of the ‘crossover’ effect, where stress and consequences from one partner's employment instability spill over into the family, impacting the other partner's well-being (Bakker & Demerouti, 2013; Elder et al., 2003). Therefore, it is not only important to use a detailed measure of employment instability, but it is also crucial to account for gender differences.

In the present paper, we explore the following research questions: Do different levels of employment instability affect individuals’ and their partners’ well-being to a different extent? If so, do these associations vary by gender?

Background

Employment Instability and Life Satisfaction

In addition to securing individuals’ and families’ livelihoods, employment fulfils various psychological needs, provides structure to individuals’ lives, defines aspects of their identity and status, and offers opportunities for skill use and competence development (Carr & Chung, 2014; Jahoda, 1981; Luhmann et al., 2014). Moreover, employment facilitates social interactions and is essential for pursuing individual and collective goals (Jahoda, 1981; Pearlin et al., 1981). Therefore, employment plays a crucial role in well-being and life satisfaction.

Perception of Job Insecurity

The perception of job insecurity is characterized by uncertainty about one's future employment. It generates feelings of powerlessness, distress, and strain affecting the individual’s well-being (Greenhalgh & Rosenblatt, 1984; Klandermans & van Vuuren, 1999). Job insecurity is a subjective phenomenon that largely depends on the employee’s perception (De Witte, 2005; Sverke et al., 2002). Accordingly, job insecurity is not necessarily followed by job loss. A distinction is made between cognitive and affective job insecurity (Huang et al., 2010): cognitive insecurity refers to the evaluation of the risk of job loss, while affective insecurity reflects the emotional response to this risk, such as fears and worries. In the empirical part of this article, we will focus on affective job insecurity.

Previous research has consistently shown that perceived job insecurity has a detrimental effect on physical and mental well-being (Kim & von dem Knesebeck, 2016; Klug et al., 2020). However, the strength of the negative reaction depends on the severity of a potential job loss: if, for instance, the job is an important source of identity or provides most or all of a family's livelihood, the negative impact of the threat of job loss is likely to be stronger (Greenhalgh & Rosenblatt, 1984). Hobfoll’s (1989) Conservation of Resources (COR) theory explains that job insecurity depletes well-being by threatening personal and professional resources, causing individuals to defensively tap into personal reserves, which increases stress and diminishes well-being (Vander Elst et al., 2018). The significant decline in well-being in response to perceived job insecurity aligns with ‘stress theory’ (Burgard et al., 2009; Clark et al., 2008; De Cuyper & De Witte, 2006; De Witte, 1999) and longitudinal studies reveal that subjective job insecurity creates lasting decreases in well-being and can lead to prolonged impairment of health (Burgard et al., 2009; Glavin, 2015). From this, we deduce hypothesis 1:

H1: An increase in individuals’ perceived job insecurity is expected to be associated with a reduction in life satisfaction.

Job Loss and Unemployment

Rather than dealing with the stress of threat, uncertainty, and unpredictability caused by perceived job insecurity, individuals who have experienced job loss have to cope with its direct consequences. The pecuniary costs of unemployment, such as income loss, put individuals’ finances at risk, expose them to economic deprivation and erode their living standards (Conger et al., 1990; Winkelmann & Winkelmann, 1995) as unemployment benefits—if available—usually cover only part of the previous salary (Asenjo & Pignatti, 2019). Moreover, unemployment leads to a loss of time structure and social contacts, as well as deterioration of self-esteem and professional identity (Jahoda, 1981; Pearlin et al., 1981). Furthermore, unemployed individuals must search for new employment, which takes time and energy. Unsurprisingly, previous research has widely shown a negative impact of job loss and unemployment on individuals’ physical and mental health (Esche, 2020; Kim & von dem Knesebeck, 2016; McKee-Ryan et al., 2005; Paul & Moser, 2009). However, most of the studies focus on involuntary reasons for job loss such as dismissals, plant closures or mass layoffs, or conceptualize job loss as a broad dichotomy distinguishing between individuals who did versus did not terminate their jobs. In fact, involuntary job losses have been shown to lead to significant reductions in well-being (Clark & Oswald, 1994; Gerlach & Stephan, 1996; Winkelmann & Winkelmann, 1998). Specifically, such job losses often result from an abrupt termination without prior warning, leading to increased stress (Kassenboehmer & Haisken-DeNew, 2009; Mendolia, 2014; Nikolova & Ayhan, 2019). Involuntary job loss encompasses both dismissals—often due to disciplinary reasons or declines in productivity—and redundancies resulting from economic downturns or organizational restructuring (Mendolia, 2014). Both types are characterized by a lack of self-determination of the employee (Di Nallo, 2024). Moreover, dismissal can significantly decrease self-esteem and the sense of control over one’s life, and might be interpreted as personal failure (Mendolia, 2014; Pearlin et al., 1981). Yet, job loss might not necessarily be negative; its impact largely depends on the voluntariness of job termination (Dirksen, 1994; Pearlin et al., 1981). Voluntary forms of unemployment, such as resignations or terminations by mutual agreement, are less likely to affect one’s self-esteem and sense of mastery (Pearlin et al., 1981) as they reflect a higher level of personal choice. These circumstances can offer opportunities for better employment or new paths, such as pursuing further education or venturing into self-employment (Dirksen, 1994). Moreover, voluntary job termination allows workers to prepare for job loss, reducing the risk of well-being deterioration. Preparation may include economic countermeasures like saving money and securing documents to facilitate re-employment, engaging in social activities to strengthen networks that might help seize new job opportunities, and proactive mental responses (Sweet & Moen, 2012). Other reasons for job termination, such as the end of self-employment or a fixed-term contract, might have an intermediate position on the voluntariness spectrum (Di Nallo, 2024). We formulate hypotheses 2 and 3 as follows:

H2: Experiencing unemployment reduces life satisfaction and has a bigger impact than perceiving job insecurity because the former is also characterized by pecuniary costs and direct losses.

H3: Experiencing an involuntary job loss, combining economic costs (e.g., lost salary and skill depreciation) with non-economic costs (e.g., stress, lack of self-esteem and control, etc.), is more detrimental to life satisfaction than a voluntary job termination that has fewer non-economic costs. The residual group, including unemployment after the end of self-employment or a fixed-term contract, is expected to have an impact that falls between the previous two.

Crossover Effects on Partners

The well-being of one partner in a relationship can be influenced by the employment instability experienced by the other. This phenomenon, known as the ‘crossover’ effect, occurs due to the interdependence of partners' lives, with shared financial resources and time management, and common relationships (Elder et al., 2003). The spillover-crossover model (SCM) by Bakker and Demerouti (2013) highlights that work experiences can alter behaviours and social interactions, thereby affecting home dynamics.

The pathways through which employment instability affects the well-being of partners are diverse. Economic strain often mediates these effects by creating financial stress that disrupts relationship stability and increases the likelihood of anxiety and reduced self-esteem (Voßemer et al., 2024). Beyond economic aspects, the strain experienced by one spouse may lead to changes in resource allocation, household responsibilities, and job roles, potentially impacting a couple’s emotional stability (Esche, 2020; Van der Lippe et al., 2018). Additionally, non-financial consequences such as loss of time structure, social connections, collective purpose, and status also play a significant role in shaping couple dynamics (Knabe et al., 2016). Crossover may also operate through empathy, whereby individuals share their partner's emotional state (Westman, 2001). Moreover, under strain, individuals may be less able to support their partner and communicate less constructively (Bodenmann et al., 2015).

In their review of the consequences of job insecurity on family-related outcomes, Mauno et al. (2017) showed significant effects of job insecurity on work-to-family conflicts as well as family-to-work conflicts, marital role quality, and parental stress and dissatisfaction. In line with this, job insecurity reduces the partner’s relationship and life satisfaction (Blom et al., 2020; Hanappi & Lipps, 2019). Furthermore, perceived job insecurity impaired the partner’s mental health status, particularly in single-income couples where financial concerns might be more important as there is no second income that could buffer income losses (Bünnings et al., 2017). Research on the crossover effects of one partner’s unemployment on the other reveals mixed findings, reflecting variations in study design, sample characteristics, and contextual factors. While some studies did not find any significant effects (Bubonya et al., 2017; Siegel et al., 2003; Whelan, 1994), others found moderate (Clark, 2003; Howe et al., 2004; Kim & Do, 2013; Luhmann et al., 2014; Marcus, 2013; Winkelmann & Winkelmann, 1995) to strongly negative effects (Mendolia, 2014; Nikolova & Ayhan, 2019). Nikolova and Ayhan (2019) found that unemployment caused by plant closures strongly reduced life satisfaction, household income satisfaction, and the standard of living of the unemployed partner’s spouse. Similarly, Mendolia (2014) found that husbands’ redundancy decreased both partners’ mental health.

This study aims to complement the existing literature by examining the extent to which different levels of employment instability affect the partners’ life satisfaction. Hypothesis 4 reads as follows:

H4: One partner’s employment instability affects the other partner's life satisfaction, and the more severe the employment instability (ranging from jobs that are somewhat insecure to those that are very insecure, and from voluntary to involuntary unemployment), the stronger the crossover effects.

The Role of Gender

Many societies continue to maintain traditional role expectations for women and men, particularly regarding paid and unpaid work, which may lead to different reactions to employment instability. The 'doing gender' theory suggests that gender-based norms shape the division of labour within households (West & Zimmerman, 1987). In many societies, including Germany, traditional views persist. Men are often seen primarily as main breadwinners, while women are expected to manage household and caregiving responsibilities (Bowman, 2023; Gonalons-Pons & Gangl, 2021; Kowalewska & Vitali, 2024). Consequently, unemployment affects men and women differently. For men, it deviates sharply from expected gender roles, potentially triggering a loss of self-esteem, shame, and stigma. For women, however, unemployment might align more closely with traditional expectations of house- and family work (Heyne & Voßemer, 2023; van der Meer, 2014).

Previous research offers mixed findings regarding gendered responses to employment instability, with some studies indicating similar reactions across genders (e.g. De Witte et al., 2016) and others pointing to gendered effects. In their meta-analysis, Cheng and Chan (2008) showed that the relationship between job insecurity and mental and physical health is the same for men and women. In line with this, Y. Kim et al. (2021) found that job insecurity affected sleep quality regardless of gender. In contrast, Kalil et al. (2010) found that job insecurity had a stronger impact on the physical health of older men than older women, but also a stronger impact on the mental health of women than that of men. Gaunt and Benjamin (2007) suggested that it is not gender that influences the stress response to job insecurity, but individual gender ideology: While traditional women were somewhat protected from the negative effects of job insecurity by the centrality of their family roles, egalitarian women were as affected by job insecurity as men. Also concerning unemployment, findings were mixed. Some studies have found larger negative effects on men's mental well-being compared to women's (Bowman, 2023; Carr & Chung, 2014; Luhmann et al., 2014; Marcus, 2013; Paul & Moser, 2009; van der Meer, 2014). However, others did not find gender differences in subjective well-being in response to unemployment (Hammarström et al., 2011; Leeflang et al., 1992; McKee-Ryan et al., 2005; Nordenmark & Strandh, 1999; Thomas et al., 2005).

The crossover effects of employment instability, in addition to individual responses, may also differ by gender. Due to prevailing gender roles, women have more alternative roles to take on and caring for their families rather than being employed does not necessarily break the social norm (Bowman, 2023; van der Meer, 2014). If a woman loses her employment, she can slip into the homemaker’s role, and her male partner would become the main breadwinner. Although the couple would suffer financial losses, it would still fulfil traditional gender norms (Gonalons-Pons & Gangl, 2021), and conforming to social role expectations may cushion the economic shock somewhat. On the other hand, if the man becomes unemployed, the woman becomes the main breadwinner, and neither the man nor the woman fulfils the prevailing social roles, leading to a decrease in life satisfaction for both partners (Kowalewska & Vitali, 2024). Furthermore, in countries such as Germany, where men usually work full-time, whereas women often have part-time jobs (Lott et al., 2022), the financial losses for a couple are more severe if the man loses his job than if the woman does. Moreover, a married woman’s social status is somewhat dependent on her male spouse's social status (van der Meer, 2014). Therefore, her social status may drop as well if he becomes unemployed.

Previous research has shown that the effect of men’s job insecurity on women’s mental health is more negative and lasts longer than vice versa (Schatz, 2018). Furthermore, women reported lower relationship quality if their spouses experienced job insecurity. Interestingly, insecure men were more satisfied with their relationship if their female spouses also reported job insecurity (Blom et al., 2020). The authors assumed that it is more difficult for men to deal with employment instability if their female partner is in a better job situation, as they deviate more strongly from the prevailing social norm of being the main breadwinner. In contrast, Debus and Unger (2017) showed that men had greater health impairments if their female partners reported medium to high levels of job insecurity, assuming an adverse effect of the male partners’ pressure to secure the main share of household income. Furthermore, Emanuel et al. (2018) found men’s and women’s family life satisfaction to be similarly affected by their partners’ job insecurity. In line with the findings on job insecurity, research indicates that men’s unemployment often has a greater negative impact on their female partners’ well-being than vice versa (Bowman, 2023; Bubonya et al., 2017; Esche, 2020; Inanc, 2018; Marcus, 2013; van der Meer, 2014; Winkelmann & Winkelmann, 1995). However, studies on German couples have found no gendered crossover effects in some well-being markers (Knabe et al., 2016; Luhmann et al., 2014; Nikolova & Ayhan, 2019). In a study distinguishing between different reasons for job termination in the UK, Di Nallo (2024) found that male partners’ involuntary job loss significantly impacted their female partners’ well-being, whereas women’s unemployment had a smaller effect on their male partners. We formulate hypotheses 5 and 6 as follows:

H5: Men are more strongly affected by employment instability than women.

H6: The crossover effects from men to women are more pronounced than from women to men.

Data and Methods

Data

The data (SOEP, 2024) for this study come from the German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP), one of the longest-running household panel surveys that started in 1984 in West Germany and expanded to East Germany in 1990. The survey follows nearly 15,000 households and 30,000 individuals (Goebel et al., 2019), and includes detailed annual information on employment status, job insecurity, and well-being outcomes. An advantage of this data is that it provides independent information from both partners in each couple, as each household member aged 16 or older is interviewed separately. Additionally, the data covers multiple employment transitions, allowing for adequate variability in employment instability.

Sample

The analysis focused on married or non-married cohabiting couples where both partners were active in the labour market (employed or unemployed). The focal respondents’ and their partners’ age range was limited to 20 to 64, representing the working-age population. The study used all available samples and the waves from 1991 to 2022, as full information on the cause of unemployment was available from 1991 onwards. The analysis differentiated between the labour market status of men and women. It is important to note that individuals may have switched jobs between interviews and experienced intermediate periods of unemployment. The analytical sample included 34,996 men and women, contributing 192,814 observations with non-missing life satisfaction. This amounts to about six observations per person on average.

Measurements

The dependent variable was respondents’ self-reported current life satisfaction, measured on a scale from 0 (‘completely dissatisfied’) to 10 (‘completely satisfied’). This measure primarily captured the cognitive component of subjective well-being (Veenhoven, 1996). It was based on the question ‘How satisfied are you at present with your life as a whole’. This measure, along with other global life satisfaction scales, has been shown to be reliable and sensitive to personal changes (Diener et al., 2013). The variable was treated as continuous in the analysis (Ferrer-i-Carbonell & Frijters, 2004).

The key independent variable combined information on the individual’s current work status and the level of perceived job insecurity for those employed. Employment instability was measured by asking respondents (a) whether they were employed, (b) if they had concerns about their job security, (c) if they were registered as unemployed and, if so, (d) the reason for job termination. These pieces of information were combined to generate the main independent variable. The level of job insecurity was measured with the question ‘Do you have worries about losing your job?’ and the answer categories were ‘no worries at all’, ‘some worries’, or ‘severe worries’. Unemployment was based on self-reported employment status and respondents were asked to provide reasons for their unemployment if applicable.Footnote 1 Based on this information, the analysis distinguished between voluntary and involuntary unemployment, in line with Kassenboehmer and Haisken-DeNew (2009). Individuals who reported ‘fired’ (dismissal), or ‘company closure’ were considered ‘involuntarily unemployed’. The category of voluntary unemployment included the circumstances ‘I resigned’, ‘mutual agreement with employer’, and ‘transferred on own request’. Furthermore, a residual category ‘other’ was used for unemployment if it was unknown whether termination was voluntary or involuntary. The variable summarizing employment instability therefore included six categories: (1) employed reporting a secure job (reference group); (2) employed with some job insecurity; (3) employed with severe job insecurity; (4) unemployed after voluntary job termination; (5) unemployed after involuntary job loss, (6) unemployed for undisclosed or other reasons. The employment status of the partner was constructed in the same way as that of the main respondents. Observations were excluded if they could not be classified into one of the six specified categories or if partner information was missing.

The analysis included control variables encompassing age divided by 100 (linear and quadratic) and a dummy variable to distinguish between East and West Germany. We also included year dummies and dummies for the first three observations, as individuals are prone to social desirability bias and may overestimate their life satisfaction in earlier interview waves (Chadi, 2013). To avoid overcontrol bias, we do not include more control variables (Grätz, 2022; Kratz & Brüderl, 2021). Table 1 provides descriptive statistics of the variables included in the multivariate models.

Analyses

Our main specification for both samples is the fixed effects model:

Starting from the usual pooled regression model, each variable is (individually) mean-centered: \(y_{it}\) is the dependent variable for individual \(i\) at time \(t\); and \(\overline{y}_{i}\) is the individual’s mean. Similarly, \(x_{it}\) represents the vector of independent variables, and \(\overline{x}_{i}\) denotes their individual mean. In addition to own employment instability, \(x\) includes the spouse’s employment instability along with all control variables; \(\beta\) is the estimated influence of the variables on the dependent variable. \(e_{it} - \overline{e}_{i}\) is the individually mean-centered residual. By mean-centering, which is equivalent to adding a dummy for each individual, the fixed effects model cancels out all time-constant unobserved heterogeneity that might be correlated with the variables (Brüderl & Ludwig, 2015; Wooldridge, 2009). The direction of causality remains unclear: job insecurity and unemployment may reduce well-being, but individuals with lower well-being might also be more vulnerable to employment instability (Andreeva et al., 2015). All models are estimated separately for men’s and women’s life satisfaction outcomes. Robust standard errors are used, clustered at the individual (couple) level. No weights were used. All statistical analyses and figures were produced with Stata 18 SE.

We adopted a stepwise approach to fit the subjective well-being of women and men separately. In Model 1, the baseline specification includes only the individuals’ employment instability and control variables. In Model 2, the partner’s employment instability indicators were added. Table 3 in the Appendix provides the full results for the models summarized in Table 2. To test gender differences on the impact of own employment instability, we also ran pooled models including interaction terms between gender and each employment instability indicator (see Table 4). However, we could not apply the same approach to partner’s employment instability, as each respondent would appear twice in the data—once as the focal individual and once as the partner—violating the assumptions of the fixed effects model.

Results

Table 2 presents the results for men’s and women’s life satisfaction based on their own and their partner’s employment instability. To test Hypothesis 1 (negative impact of perceived job insecurity on life satisfaction), we turn to Model 1. For both men and women, an increase in perceived job insecurity led to a reduction in life satisfaction, confirming Hypothesis 1. Notably, the coefficients for severe job insecurity were more than twice as large as those for some job insecurity.

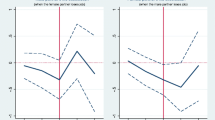

Due to the financial costs and the direct losses (e.g. loss of daily structure, social contacts, decline in self-esteem) that come with unemployment, Hypothesis 2 posited that unemployment would reduce life satisfaction and have a stronger negative impact compared to perceived job insecurity. Model 1 confirms that various reasons for unemployment reduced life satisfaction, with all coefficients being larger than those for perceived job insecurity. Figure 1 shows the predicted effects (based on Model 1) and reveals that all forms of unemployment significantly reduced life satisfaction for men. For women, the results are more complex and provide only partial support for Hypothesis 2: Unemployment after voluntary job termination was only slightly more detrimental than job insecurity. Only involuntary and other reasons for unemployment had a significantly stronger impact on life satisfaction than severe job insecurity. This aligns with Hypothesis 3, which posited that involuntary unemployment, due to higher non-pecuniary costs (e.g. loss of control), is more detrimental to life satisfaction than voluntary unemployment. For both men and women, involuntary reasons for job termination had a stronger negative effect on life satisfaction than voluntary reasons, as shown in Table 2 and Fig. 1. The difference between voluntary and involuntary unemployment was larger for women. Other reasons, such as the end of a fixed-term contract, were somewhere between voluntary and involuntary reasons for unemployment. Notably, for women, ‘other’ reasons for unemployment were closer to voluntary reasons for unemployment, while for men, they aligned more closely with involuntary unemployment. Therefore, Hypothesis 3 is confirmed. Moreover, it is noteworthy that the coefficients for involuntary unemployment are nearly double those for severe job insecurity and over four times larger than those for some job insecurity. Accordingly, involuntary unemployment clearly stands out for its negative impact on life satisfaction.

Before turning to Hypothesis 4 on crossover effects, we discuss Hypothesis 5, expecting stronger effects of employment instability for men than for women. The decline in life satisfaction with increasing severity of employment instability (from ‘some job insecurity’ to ‘involuntary unemployment’) was more linear and pronounced for men than for women. While men and women had similar levels of life satisfaction in the condition of a secure or somewhat insecure job, their levels of life satisfaction diverged once jobs became severely insecure and in the different conditions of unemployment, with men showing lower levels of life satisfaction. This observation is supported by Table 4 in the Appendix, pooling men and women and adding interaction terms for employment instability by gender. Whereas the effects of some job insecurity were the same for men and women, all other interaction terms were statistically significant, suggesting stronger effects of all other forms of employment instability for men compared to women.

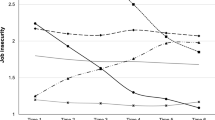

Model 2 in Table 2 reaffirms the previous findings regarding the impact of one’s own employment instability on life satisfaction. Moreover, it shows significant crossover effects from one partner to his/her spouse. Figure 2 illustrates the predicted effects from Model 2, showing that life satisfaction decreased with the spouse’s increasing severity of employment instability. These effects were slightly stronger for male than for female employment instability, indicating some degree of gendered crossover effects. However, this result should be interpreted with caution as it is not possible to back it up with additional analysis comparable to that in Table 4: When partner effects are included, it is not possible to pool men and women, since each respondent would appear twice in the same model (once as the focal respondent and once as the partner). Yet, Model 2 in Table 2 also showed that, for women, the welfare loss due to the male partner’s employment instability was about one half of the loss due to their own employment instability. For men, the corresponding partner effects were smaller, supporting the interpretation of weaker, and thus slightly gendered, crossover effects. Women reported the highest life satisfaction when their partners were employed, with no reported concerns about future job loss, while the lowest life satisfaction was observed when their partners experienced involuntary unemployment. Overall, a similar pattern emerged for female employment instability. Nevertheless, voluntary unemployment of the female spouse had a comparable effect on men as moderate levels of spousal job insecurity. We therefore found some support for Hypotheses 4 and 6, expecting increasing crossover effects with increasing severity of employment instability and stronger effects for male than for female employment instability. Despite significant crossover effects, individuals experienced a greater impact on life satisfaction from their own employment instability compared to their partners’.

Discussion

This study explored the impact of different changes in levels of employment instability on individuals’ and their partners’ life satisfaction, examining whether the effects varied by gender. The construction of a fine-grained indicator of employment instability, encompassing perceived job insecurity and different reasons for unemployment, has offered novel insights into its impact on life satisfaction.

Although job insecurity has received growing attention in the literature, recent evidence from Germany suggests that worries about job loss may have declined over time (Clark, 2024). Yet, the experience of job insecurity remains relevant for well-being. Our study does not focus on time trends but instead provides a comprehensive analysis of the differential consequences of employment instability when it occurs.

Previous studies have often focused on either job insecurity or unemployment, rarely examining them together, despite the interesting insights this approach can provide. For example, some studies showed that perceived job insecurity can be more detrimental to well-being than unemployment (e.g. Knabe & Rätzel, 2010). It is therefore informative and important to look at job insecurity and unemployment together. Moreover, unemployment is usually considered a uniform involuntary condition (Kassenboehmer & Haisken-DeNew, 2009). Yet, there are different reasons for job termination and these presumably have distinct effects on well-being.

Based on longitudinal data from Germany, this study reveals four main findings. First, both job insecurity and unemployment negatively influenced individuals and their partners. Notably, unemployment has stronger negative effects on life satisfaction than perceived job insecurity. In other words, the loss of a job had more significant implications for individuals’ and partners’ well-being compared to anticipating a future job loss. These results align with some previous studies that have examined the effects of unemployment and perceived job insecurity on health and well-being (Amick et al., 2002; Flint et al., 2013). However, they contradict research that has suggested that perceived job insecurity can be equally or more detrimental to well-being than unemployment (Griep et al., 2016; Kim & von dem Knesebeck, 2016; Knabe & Rätzel, 2010).

Second, we have shown that unemployment after involuntary job loss is more detrimental to life satisfaction than unemployment after voluntary job termination. The difference in the impact on life satisfaction between the two conditions is larger for women. However, this is mainly due to the comparatively weak effect of female voluntary unemployment. The existing literature has long debated whether involuntary changes and unexpected stress have more adverse consequences than anticipated stress. In the case of involuntary unemployment, the non-economic costs are higher than in the case of voluntary job termination, as the sudden loss of control over an important area of life, such as employment, is highly detrimental to life satisfaction. In addition, there may be a loss of self-esteem in the case of dismissal for personal reasons (Pearlin et al., 1981). In contrast, voluntary job termination may have a less severe impact compared to involuntary job loss because the worker can exercise more control over the event (Dirksen, 1994; Pearlin et al., 1981) and might be better prepared for job search or career transitions (Sweet & Moen, 2012). Also, individuals who voluntarily quit their jobs presumably have better reemployment expectations, which may explain why their job loss is less detrimental to life satisfaction. This is in line with Knabe and Rätzel (2010), who found that unemployed individuals with high subjective reemployment expectations report higher life satisfaction than both those with low reemployment expectations and even those who remain employed but feel highly insecure about their job. Furthermore, our findings are in line with Di Nallo (2024) who found strong detrimental effects of involuntary reasons for job termination on mental well-being in a British sample. In contrast to involuntary job loss, he found that individuals who reported more voluntary job endings even experienced increased mental well-being. Furthermore, our study showed that other reasons for unemployment that cannot be classified unanimously as voluntary or involuntary strongly affect life satisfaction. The ‘other’-category predominantly contains unemployment after the end of a fixed-term contract (68% for men; 76% for women). For men, the impact was very close to involuntary unemployment, showing that even anticipated career interruptions are very detrimental to their life satisfaction. For women, in contrast, the effects of other reasons for unemployment were closer to voluntary unemployment. Women might have specific attitudes or reasons for temporary work (Casey & Alach, 2004), and therefore, the end of a contract might be less harmful to them than to men.

Third, our study demonstrated that the impact of employment instability on life satisfaction varies by gender. While men and women who did not perceive job insecurity had similar levels of life satisfaction, men’s life satisfaction more strongly decreased the more severe the condition of employment instability was. The more adverse effects on men might be the consequence of the prevailing gender roles. The ‘doing gender’ hypothesis assumes that men and women build their social identity by aligning themselves with the predominant gender norms in which masculinity is highly determined by the professional role and being the main breadwinner in the family (Bowman, 2023; West & Zimmerman, 1987). Accordingly, unemployment means a particularly important deviation from the current gender norm for men, which adversely affects their self-perception and well-being (van der Meer, 2014). Employment appears essential for men to maintain high levels of life satisfaction, with even poor job conditions being preferable to unemployment (van der Meer, 2014). In contrast, women deviate less from the prevailing gender norm if they are not employed, which is reflected in smaller declines in life satisfaction in the case of employment instability. Therefore, the ‘doing gender’ and ‘gender deviation’ theories may partly explain the gendered results. Our study corroborates research that has shown men to be more affected by unemployment than women (e.g. Bowman, 2023; Carr & Chung, 2014; Heyne & Voßemer, 2023; Paul & Moser, 2009). However, it is not in line with a study from the UK showing that men with traditional role attitudes suffer less from unemployment than men with egalitarian attitudes (Longhi et al., 2024). Moreover, women with traditional attitudes, who are more likely to transition into alternative roles, suffer more from unemployment than egalitarian women. The authors explain their findings with traditional women's greater need and difficulty in finding new employment due to their lower labour market prospects and lower household income (Longhi et al., 2024).

Fourth, clear bi-directional crossover effects between partners have been identified. Our study reveals that men’s employment instability affected their female partners’ life satisfaction, though to a lesser extent than one’s own employment instability, and vice versa. The negative impact of employment instability on partners could be driven by various factors, such as increased financial strain, worries about future income, social stigma, and the reallocation of household responsibilities (Esche, 2020; Luhmann et al., 2014). Our findings are in line with previous research based on data from the SOEP or similar surveys from other Western European countries, such as the Swiss Household Panel (SHP) or the British Household Panel Survey (BHPS), showing that employment instability not only affects the concerned individuals but also their spouses (Bünnings et al., 2017; Hanappi & Lipps, 2019; Mendolia, 2014; Nikolova & Ayhan, 2019). Moreover, we showed that men were slightly less affected by their partners’ employment instability than the other way round, especially in the case of female voluntary unemployment. The observed moderate asymmetry of crossover is in line with previous research (e.g. Bowman, 2023; Bubonya et al., 2017; Schatz, 2018) and can be explained by the prevailing social norm in Germany: As men still tend to be breadwinners, their employment instability not only has a stronger impact on their own but also a stronger influence on their partners’ life satisfaction.

The present research established a strong association between employment instability and the life satisfaction of individuals and their partners, using an innovative indicator that accounted for various forms of employment instability, including secure and insecure work, as well as different reasons for unemployment. However, the present study is not without limitations. Firstly, the distinction between voluntary and involuntary unemployment is not entirely indisputable, despite being supported by prior literature (Kassenboehmer & Haisken-DeNew, 2009). Some workers may deliberately attempt to be fired to qualify for unemployment benefits (Mendolia, 2014), while others may quit due to workplace harassment or pressure from a superior. Secondly, the number of observations of unemployment after voluntary job termination is small (673 for women; 490 for men), which leads to large confidence intervals. Employees who voluntarily resign from a job presumably have already found a new job in most cases. The higher number of voluntarily unemployed women might again be explained by the prevailing social norm in Germany. As women often are secondary earners, it is less consequential for the whole family if they are unemployed for some time, and therefore, they have more latitude for this type of career choice. Thirdly, the analyses were limited to cohabiting couples, so the findings cannot be generalized to singles and non-cohabiting couples. Future research might focus specifically on single individuals, who may experience stronger economic pressures as they lack a partner as a backup source of income.

The present study has important policy implications. Firstly, it highlights the negative consequences of employment instability arising from both unemployment and perceived job insecurity, not only for the individuals themselves but also for their partners and possibly other family members. This underlines the importance of welfare state buffers, such as unemployment benefits, and policies to improve the employability of workers. Secondly, the analyses reveal that the impact of employment instability is influenced by gender, particularly when viewed from the perspective of intentionality. Couples’ life satisfaction is contingent on their partners’ labour market conditions, with women appearing more dependent on men’s employment stability than vice versa. Moreover, unemployment, even if voluntary, tends to have a more disruptive effect on men compared to women. These findings emphasize the notion that employment might still be perceived as essential for masculinity in the context of Germany. To address these gender disparities and promote greater equality, initiatives should be supported that empower women in gaining a solid foothold in the workforce to reduce the economic dependency of women, but also the financial burden on men. Additionally, these efforts would help reduce the influence of traditional gender roles.

Data Availability

The data underlying this article were provided by the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW) with a data contract. Interested researchers can apply for the data at https://www.diw.de/en/diw_01.c.601584.en/data_access.html.

Notes

We imputed missing reasons of the previous year with the reason of the current year if the individual was unemployed in the previous year.

References

Amick, B. C. I., McDonough, P., Chang, H., Rogers, W. H., Pieper, C. F., & Duncan, G. (2002). Relationship between all-cause mortality and cumulative working life course psychosocial and physical exposures in the United States labor market from 1968 to 1992. Psychosomatic Medicine, 64(3), 370–381. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-200205000-00002

Andreeva, E., Hanson, L. L. M., Westerlund, H., Theorell, T., & Brenner, M. H. (2015). Depressive symptoms as a cause and effect of job loss in men and women: Evidence in the context of organisational downsizing from the Swedish Longitudinal Occupational Survey of Health. BMC Public Health, 15(1), 1045. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-2377-y

Asenjo, A., & Pignatti, C. (2019). Unemployment insurance schemes around the world: Evidence and policy options (49; Research Department Working Paper). International Labour Office.

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2013). The spillover-crossover model. In J. G. Grzywacz & E. Demerouti (Eds.), Current issues in work and organizational psychology. New Frontiers in work and family research (pp. 54–70). Psychology Press.

Blom, N., Verbakel, E., & Kraaykamp, G. (2020). Couples’ job insecurity and relationship satisfaction in the Netherlands. Journal of Marriage and Family, 82(3), 875–891. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12649

Bodenmann, G., Meuwly, N., Germann, J., Nussbeck, F. W., Heinrichs, M., & Bradbury, T. N. (2015). Effects of stress on the social support provided by men and women in intimate relationships. Psychological Science, 26(10), 1584–1594. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797615594616

Bowman, J. (2023). Whose unemployment hurts more? Joblessness and subjective well-being in U.S. married couples. Social Science Research, 111, 102795. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2022.102795

Broom, D. H., D’Souza, R. M., Strazdins, L., Butterworth, P., Parslow, R., & Rodgers, B. (2006). The lesser evil: Bad jobs or unemployment? A survey of mid-aged Australians. Social Science & Medicine, 63(3), 575–586. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.02.003

Brüderl, J., & Ludwig, V. (2015). Fixed-effects panel regression. In H. Best & C. Wolf (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of regression analysis and causal inference (pp. 327–357). SAGE.

Bubonya, M., Cobb-Clark, D. A., & Wooden, M. (2017). Job loss and the mental health of spouses and adolescent children. IZA Journal of Labor Economics, 6(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40172-017-0056-1

Bünnings, C., Kleibrink, J., & Weßling, J. (2017). Fear of unemployment and its effect on the mental health of spouses. Health Economics, 26(1), 104–117. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.3279

Burgard, S. A., Brand, J. E., & House, J. S. (2009). Perceived job insecurity and worker health in the United States. Social Science & Medicine, 69(5), 777–785. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.06.029

Carr, E., & Chung, H. (2014). Employment insecurity and life satisfaction: The moderating influence of labour market policies across Europe. Journal of European Social Policy, 24(4), 383–399. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928714538219

Casey, C., & Alach, P. (2004). ‘Just a temp?’: Women, temporary employment and lifestyle. Work, Employment and Society, 18(3), 459–480. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017004045546

Chadi, A. (2013). The role of interviewer encounters in panel responses on life satisfaction. Economics Letters, 121(3), 550–554. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2013.10.024

Cheng, G. H. L., & Chan, D. K. S. (2008). Who suffers more from job insecurity? A Meta-Analytic Review. Applied Psychology, 57(2), 272–303.

Clark, A. E. (2003). Unemployment as a social norm: Psychological evidence from panel data. Journal of Labor Economics, 21(2), 323–351. https://doi.org/10.1086/345560

Clark, A. E. (2024). Insecurity on the labour market. Review of Income and Wealth, 70(4), 914–933. https://doi.org/10.1111/roiw.12607

Clark, A. E., Diener, E., Georgellis, Y., & Lucas, R. E. (2008). Lags and leads in life satisfaction: A test of the baseline hypothesis. The Economic Journal, 118(529), F222–F243. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0297.2008.02150.x

Clark, A. E., & Oswald, A. J. (1994). Unhappiness and unemployment. The Economic Journal, 104(424), 648–659. https://doi.org/10.2307/2234639

Conger, R. D., Elder, G. H., Jr., Lorenz, F. O., Conger, K. J., Simons, R. L., Whitbeck, L. B., Huck, S., & Melby, J. N. (1990). Linking economic hardship to marital quality and instability. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 52(3), 643–656. https://doi.org/10.2307/352931

De Cuyper, N., & De Witte, H. (2006). The impact of job insecurity and contract type on attitudes, well-being and behavioural reports: A psychological contract perspective. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 79(3), 395–409. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317905X53660

De Witte, H. (1999). Job insecurity and psychological well-being: Review of the literature and exploration of some unresolved issues. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 8(2), 155–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/135943299398302

De Witte, H. (2005). Job insecurity: Review of the international literature on definitions, prevalence, antecedents and consequences. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 31(4), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v31i4.200

De Witte, H., Pienaar, J., & De Cuyper, N. (2016). Review of 30 years of longitudinal studies on the association between job insecurity and health and well-being: Is there causal evidence? Australian Psychologist, 51(1), 18–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/ap.12176

Debus, M. E., & Unger, D. (2017). The interactive effects of dual-earner couples’ job insecurity: Linking conservation of resources theory with crossover research. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 90(2), 225–247. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12169

Di Nallo, A. (2024). Job separation and well-being in couples’ perspective in the United Kingdom. Socio-Economic Review, 22(2), 883–906. https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwad066

Di Nallo, A., Lipps, O., Oesch, D., & Voorpostel, M. (2022). The effect of unemployment on couples separating in Germany and the UK. Journal of Marriage and Family, 84(1), 310–329. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12803

Diener, E., Inglehart, R., & Tay, L. (2013). Theory and validity of life satisfaction scales. Social Indicators Research, 112(3), 497–527. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-012-0076-y

Dingeldey, I., & Gerlitz, J.-Y. (2022). Labour market segmentation, regulation of non-standard employment, and the influence of the EU. In International impacts on social policy: Short histories in global perspective (pp. 247–260). Springer. https://library.oapen.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.12657/53340/1/978-3-030-86645-7.pdf#page=267

Dirksen, M. E. (1994). Unemployment: More than the loss of a job. AAOHN Journal, 42(10), 468–476.

Elder, G. H., Kirkpatrick Johnson, M., & Crosnoe, R. (2003). The emergence and development of life course theory. In J. T. Mortimer & M. J. Shanahan (Eds.), Handbook of the life course (pp. 3–19). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-306-48247-2_1

Emanuel, F., Molino, M., Presti, A. L., Spagnoli, P., & Ghislieri, C. (2018). A crossover study from a gender perspective: The relationship between job insecurity, job satisfaction, and partners’ family life satisfaction. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1481. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01481

Esche, F. (2020). Is the problem mine, yours, or ours? The impact of unemployment on couples’ life satisfaction and specific domain satisfaction. Advances in Life Course Research, 46, 100354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alcr.2020.100354

Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A., & Frijters, P. (2004). How important is methodology for the estimates of the determinants of happiness? The Economic Journal, 114(497), 641–659. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0297.2004.00235.x

Flint, E., Bartley, M., Shelton, N., & Sacker, A. (2013). Do labour market status transitions predict changes in psychological well-being? Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 67(9), 796–802. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2013-202425

Gaunt, R., & Benjamin, O. (2007). Job insecurity, stress and gender: The moderating role of gender ideology. Community, Work & Family, 10(3), 341–355. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668800701456336

Gerlach, K., & Stephan, G. (1996). A paper on unhappiness and unemployment in Germany. Economics Letters, 52(3), 325–330. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-1765(96)00858-0

Glavin, P. (2015). Perceived job insecurity and health: Do duration and timing matter? The Sociological Quarterly, 56(2), 300–328. https://doi.org/10.1111/tsq.12087

Goebel, J., Grabka Markus, M., Liebig, S., Kroh, M., Richter, D., & Schröder, C. (2019). The German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP). Journal of Economics and Statistics (Jahrbücher Für Nationalökonomie und Statistik), 239(2), 345–360. https://doi.org/10.1515/jbnst-2018-0022

Gonalons-Pons, P., & Gangl, M. (2021). Marriage and masculinity: Male-breadwinner culture, unemployment, and separation risk in 29 countries. American Sociological Review, 86(3), 465–502. https://doi.org/10.1177/00031224211012442

Grätz, M. (2022). When less conditioning provides better estimates: Overcontrol and endogenous selection biases in research on intergenerational mobility. Quality and Quantity, 56(5), 3769–3793. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-021-01310-8

Greenhalgh, L., & Rosenblatt, Z. (1984). Job insecurity: Toward conceptual clarity. Academy of Management Review, 9(3), 438–448.

Griep, Y., Kinnunen, U., Nätti, J., De Cuyper, N., Mauno, S., Mäkikangas, A., & De Witte, H. (2016). The effects of unemployment and perceived job insecurity: A comparison of their association with psychological and somatic complaints, self-rated health and life satisfaction. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 89, 147–162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-015-1059-5

Hammarström, A., Gustafsson, P. E., Strandh, M., Virtanen, P., & Janlert, U. (2011). It’s no surprise! Men are not hit more than women by the health consequences of unemployment in the Northern Swedish Cohort. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 39(2), 187–193. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494810394906

Hanappi, D., & Lipps, O. (2019). Job insecurity and parental well-being: The role of parenthood and family factors. Demographic Research, 40(31), 897–932. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2019.40.31

Heyne, S., & Voßemer, J. (2023). Gender, unemployment, and subjective well-being: Why do women suffer less from unemployment than men? European Sociological Review, 39(2), 301–316. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcac030

Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources. A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513–524. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.44.3.513

Howe, G. W., Lockshin Levy, M., & Caplan, R. D. (2004). Job loss and depressive symptoms in couples: Common stressors, stress transmission, or relationship disruption? Journal of Family Psychology, 18(4), 639–650. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.18.4.639

Huang, G.-H., Lee, C., Ashford, S., Chen, Z., & Ren, X. (2010). Affective job insecurity: A mediator of cognitive job insecurity and employee outcomes relationships. International Studies of Management & Organization, 40(1), 20–39. https://doi.org/10.2753/IMO0020-8825400102

Inanc, H. (2018). Unemployment, temporary work, and subjective well-being: The gendered effect of spousal labor market insecurity. American Sociological Review, 83(3), 536–566. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122418772061

Jacobson, D. (1991). The conceptual approach to job insecurity. In J. Hartley, D. Jacobson, B. Klandermans, T. van Vuuren, L. Greenhalgh, & R. Sutton (Eds.), Job insecurity. Coping with jobs at risk (pp. 23–39). SAGE.

Jahoda, M. (1981). Work, employment, and unemployment: Values, theories, and approaches in social research. American Psychologist, 36(2), 184–191. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.36.2.184

Kalil, A., Ziol-Guest, K. M., Hawkley, L. C., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2010). Job insecurity and change over time in health among older men and women. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 65B(1), 81–90. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbp100

Kassenboehmer, S., & Haisken-DeNew, J. P. (2009). You’re fired! The causal negative effect of entry unemployment on life satisfaction. The Economic Journal, 119(536), 448–462. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0297.2008.02246.x

Kim, M.-H., & Do, Y. K. (2013). Effect of husbands’ employment status on their wives’ subjective well-being in Korea. Journal of Marriage and Family, 75(2), 288–299. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12004

Kim, T. J., & von dem Knesebeck, O. (2016). Perceived job insecurity, unemployment and depressive symptoms: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 89(4), 561–573. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-015-1107-1

Kim, Y., Kramer, A., & Pak, S. (2021). Job insecurity and subjective sleep quality: The role of spillover and gender. Stress and Health, 37(1), 72–92. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2974

Klandermans, B., & van Vuuren, T. (1999). Job insecurity: Introduction. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 8(2), 145–153.

Klug, K., Bernhard-Oettel, C., Selenko, E., & Sverke, M. (2020). Temporal and person-oriented perspectives on job insecurity. In Handbook on the temporal dynamics of organizational behavior (pp. 91–104). Edward Elgar Publishing.

Knabe, A., & Rätzel, S. (2010). Better an insecure job than no job at all? Unemployment, job insecurity and subjective wellbeing. Economics Bulletin, 30(3), 2486–2494.

Knabe, A., Schöb, R., & Weimann, J. (2016). Partnership, gender, and the well-being cost of unemployment. Social Indicators Research, 129(3), 1255–1275. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-1167-3

Kowalewska, H., & Vitali, A. (2024). The female-breadwinner well-being ‘penalty’: Differences by men’s (un)employment and country. European Sociological Review, 40(2), 293–308. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcad034

Kratz, F., & Brüderl, J. (2021). The age trajectory of happiness. OSF.

Leeflang, R. L. I., Klein-Hesselink, D. J., & Spruit, I. P. (1992). Health effects of unemployment—II. Men and women. Social Science & Medicine, 34(4), 351–363. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(92)90295-2

Longhi, S., Nandi, A., Bryan, M., Connolly, S., & Gedikli, C. (2024). Life satisfaction and unemployment—The role of gender attitudes and work identity. Scottish Journal of Political Economy, 71(2), 219–236. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjpe.12366

Lott, Y., Hobler, D., Pfahl, S., & Unrau, E. (2022). Stand der Gleichstellung von Frauen und Männern in Deutschland (72; WSI Report). Hans-Böckler-Stiftung, Wirtschafts- und Sozialwissenschaftliches Institut (WSI).

Luhmann, M., Weiss, P., Hosoya, G., & Eid, M. (2014). Honey, I got fired! A longitudinal dyadic analysis of the effect of unemployment on life satisfaction in couples. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 107(1), 163. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036394

Manning, A., & Mazeine, G. (2022). Subjective job insecurity and the rise of the precariat: Evidence from the United Kingdom, Germany, and the United States. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 1–45. https://doi.org/10.1162/rest_a_01196

Marcus, J. (2013). The effect of unemployment on the mental health of spouses—Evidence from plant closures in Germany. Journal of Health Economics, 32(3), 546–558. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2013.02.004

Mauno, S., Cheng, T., & Lim, V. (2017). The far-reaching consequences of job insecurity: A review on family-related outcomes. Marriage & Family Review, 53(8), 717–743. https://doi.org/10.1080/01494929.2017.1283382

McKee-Ryan, F., Song, Z., Wanberg, C. R., & Kinicki, A. J. (2005). Psychological and physical well-being during unemployment: A meta-analytic study. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(1), 53–76. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.1.53

Mendolia, S. (2014). The impact of husband’s job loss on partners’ mental health. Review of Economics of the Household, 2(12), 277–294. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-012-9149-6

Nikolova, M., & Ayhan, S. H. (2019). Your spouse is fired! How much do you care? Journal of Population Economics, 32(3), 799–844. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-018-0693-0

Nordenmark, M., & Strandh, M. (1999). Towards a sociological understanding of mental well-being among the unemployed: The role of economic and psychosocial factors. Sociology, 33(3), 577–597. https://doi.org/10.1177/S0038038599000

Paul, K. I., & Moser, K. (2009). Unemployment impairs mental health: Meta-analyses. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 74(3), 264–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2009.01.001

Pearlin, L. I., Menaghan, E. G., Lieberman, M. A., & Mullan, J. T. (1981). The stress process. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 22, 337–356.

Redak, V., Weber, B., & Wöhl, S. (2008). Editorial: Prekarisierung und kritische Gesellschaftstheorie. Kurswechsel. Zeitschrift Für Gesellschafts-, Wirtschafts- und Umweltpolitische Alternativen, 1, 3–12.

Schatz, S. G. (2018). Job insecurity and mental health from a spillover-crossover perspective—Multilevel modeling of longitudinal dyadic data [PhD Thesis]. University of Duisburg-Essen.

Scheuring, S. (2020). The effect of fixed-term employment on well-being: Disentangling the micro-mechanisms and the moderating role of social cohesion. Social Indicators Research, 152(1), 91–115. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-020-02421-9

Siegel, M., Bradley, E. H., Gallo, W. T., & Kasl, S. V. (2003). Impact of husbands’ involuntary job loss on wives’ mental health, among older adults. The Journals of Gerontology Series b: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 58(1), S30–S37. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/58.1.S30

SOEP. (2024). Data for years 1984–2022 (SOEP-Core v39, Onsite Edition) (Version Version 39) [CSV,SPSS,Stata (bilingual),SPSS,RData,RData]. SOEP Socio-Economic Panel Study. https://doi.org/10.5684/soep.core.v39o

Strandh, M. (2000). Different exit routes from unemployment and their impact on mental well-being: The role of the economic situation and the predictability of the life course. Work, Employment and Society, 14(3), 459–479. https://doi.org/10.1177/09500170022118527

Sverke, M., Hellgren, J., & Näswall, K. (2002). No security: A meta-analysis and review of job insecurity and its consequences. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 7(3), 242–264. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.7.3.242

Sweet, S., & Moen, P. (2012). Dual earners preparing for job loss agency, linked lives, and resilience. Work and Occupations, 39(1), 35–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/0730888411415601

Thomas, C., Benzeval, M., & Stansfeld, S. A. (2005). Employment transitions and mental health: An analysis from the British Household Panel Survey. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 59(3), 243–249.

Van der Lippe, T., Treas, J., & Norbutas, L. (2018). Unemployment and the division of housework in Europe. Work, Employment and Society, 32(4), 650–669. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017017690495

van der Meer, P. H. (2014). Gender, unemployment and subjective well-being: Why being unemployed is worse for men than for women. Social Indicators Research, 115(1), 23–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-012-0207-5

Vander Elst, T., Notelaers, G., & Skogstad, A. (2018). The reciprocal relationship between job insecurity and depressive symptoms: A latent transition analysis. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 39(9), 1197–1218. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2250

Veenhoven, R. (1996). Developments in satisfaction-research. Social Indicators Research, 37(1), 1–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00300268

Voßemer, J., Baranowska-Rataj, A., Heyne, S., & Loter, K. (2024). Partner’s unemployment and subjective well-being: The mediating role of relationship functioning. Advances in Life Course Research, 60, 100606. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alcr.2024.100606

West, C., & Zimmerman, D. H. (1987). Doing gender. Gender & Society, 1(2), 125–151. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243287001002002

Westman, M. (2001). Stress and strain crossover. Human Relations, 54(6), 717–751. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726701546002

Whelan, C. T. (1994). Social class, unemployment, and psychological distress. European Sociological Review, 10(1), 49–61. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.esr.a036315

Winkelmann, L., & Winkelmann, R. (1995). Happiness and unemployment: A panel data analysis for Germany. Applied Economics Quarterly, 41(4), 293–307. https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-1189

Winkelmann, L., & Winkelmann, R. (1998). Why are the unemployed so unhappy? Evidence from panel data. Economica, 65(257), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0335.00111

Wooldridge, J. (2009). Introductory econometrics: A modern approach (Cengage Learning). https://pascal-francis.inist.fr/vibad/index.php?action=getRecordDetail&idt=24127469

Acknowledgements

This study has been realized using data collected by the German Socio-economic Panel (GSOEP), which is based at the DIW Berlin. The project is financed by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) and by Germany’s state (Länder) governments.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Lausanne

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation and analysis were performed by Oliver Lipps and Alessandro di Nallo. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Florence Lebert and all authors commented on previous versions and participated in the revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics Approval

As a secondary analysis of anonymised data, this study did not require ethical approval.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lebert, F., Lipps, O. & Di Nallo, A. How Perceived Job Insecurity, Voluntary Unemployment and Involuntary Job Loss Shape Couples’ Life Satisfaction. J Fam Econ Iss 46, 985–1001 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-025-10062-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-025-10062-8