Abstract

Recent advancements in computing have led to the development of artificial intelligence (AI) enabled healthcare technologies. AI-assisted clinical decision support (CDS) integrated into electronic health records (EHR) was demonstrated to have a significant potential to improve clinical care. With the rapid proliferation of AI-assisted CDS, came the realization that a lack of careful consideration of socio-technical issues surrounding the implementation and maintenance of these tools can result in unanticipated consequences, missed opportunities, and suboptimal uptake of these potentially useful technologies. The 48-h Discharge Prediction Tool (48DPT) is a new AI-assisted EHR CDS to facilitate discharge planning. This study aimed to methodologically assess the implementation of 48DPT and identify the barriers and facilitators of adoption and maintenance using the validated implementation science frameworks. The major dimensions of RE-AIM (Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, Maintenance) and the constructs of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) frameworks have been used to analyze interviews of 24 key stakeholders using 48DPT. The systematic assessment of the 48DPT implementation allowed us to describe facilitators and barriers to implementation such as lack of awareness, lack of accuracy and trust, limited accessibility, and transparency. Based on our evaluation, the factors that are crucial for the successful implementation of AI-assisted EHR CDS were identified. Future implementation efforts of AI-assisted EHR CDS should engage the key clinical stakeholders in the AI tool development from the very inception of the project, support transparency and explainability of the AI models, provide ongoing education and onboarding of the clinical users, and obtain continuous input from clinical staff on the CDS performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Clinical decision support (CDS) systems are rapidly emerging as a solution to managing the abundance of medical data and delivering patient-specific recommendations to healthcare providers to assist with diagnosis and treatment [1]. CDS comprises both computerized and non-computerized tools and interventions that provide support at one or more stages of the decision-making process including alerting, interpreting, critiquing, assisting, diagnosing, and managing [2]. Studies have shown that CDS systems are effective in improving areas of healthcare delivery such as patient safety, clinical management, and cost containment [3,4,5]. CDS tools are often integrated with electronic health records (EHR) [6]. The widespread adoption of EHR systems has promoted the rise to prominence of CDS in healthcare delivery [7].

Recent advancements in computing have led to the development of artificial intelligence (AI) enabled healthcare technologies [8,9,10]. AI leverages the vast amount of data amassed from several sources, including EHR, medical imaging, laboratory data, and biosensors to forecast a clinical state, such as a diagnosis, result, or risk for CDS [11]. Healthcare providers have utilized AI -assisted CDS to guide their clinical decision-making for rare diseases, cancer, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, sepsis, neurological diseases, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. While these studies demonstrate the benefits of AI-assisted CDS on a wide range of complex medical issues, the integration of these tools brings forth a unique set of challenges including the lack of transparency in the development of the AI model or the “black box” phenomenon, workflow interference, and negative attitudes towards the use of AI [19, 20]. Understanding these barriers is imperative as the successful adoption of AI-based CDS tools may be jeopardized if they are not addressed [21,22,23]. The majority of previous studies focused on the accuracy of ML models, potential sources of bias, fairness, transparency, technical challenges of integrating AI-assisted CDS into commercial EHR, and impact on clinical care [24,25,26,27,28]. With the rapid proliferation of AI-assisted CDS, came the realization that lack of careful consideration of socio-technical issues surrounding the implementation and maintenance of these tools can result in unanticipated consequences, missed opportunities, and suboptimal uptake of these potentially useful technologies [29,30,31,32].

At the Mount Sinai Hospital System (MSHS), a number of internally developed AI-assisted CDS technologies were integrated into Epic EHR and made available to healthcare providers and administrative staff. Among these technologies is a 48-h discharge prediction tool (48DPT), which utilizes a novel machine learning algorithm to predict the discharge date for hospitalized patients using discrete clinical data from Epic EHR. An accurate prediction of patient discharge timeline allows timely engagement of clinical staff, patients, and families in the discharge planning process which is believed to be a crucial aspect of successful transitions of care [33, 34]. The hospitalized patient care plans are reviewed daily at the interdisciplinary rounds (IDR) with collaborative input from a range of hospital professionals including physicians, nurses, social workers, physical and occupational therapists, and pharmacists [35]. While the 48DPT is primarily used by the hospitalist service as part of interdisciplinary rounds, its overall adoption, acceptance, and perceived impact remain unclear.

Research on dissemination and implementation (DI) has shown that if the sociotechnical context of an intervention workflow is not taken into consideration, evidence of efficacy alone will not be sufficient to encourage acceptance and adoption [36, 37]. In DI research, conceptual frameworks are used to improve the "generalizability and interpretability of research findings" [38]. These frameworks are used to aid in understanding the success or failure of the implementation of an intervention as well as identify variables that may impact efficacy [39]. One of the most commonly used DI frameworks is RE-AIM (Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, Maintenance). In a variety of clinical, community, and business contexts, the RE-AIM framework has been utilized to address a broad range of populations, settings, and health challenges [40]. The RE-AIM framework was developed to address the challenges of applying the findings from scientific studies to practical applications and health policy [41]. The five dimensions of RE-AIM serve as an in-depth tool to analyze the development, adoption, and assessment of implementation strategies. RE-AIM provides actionable insights by defining the target audience whose health or behaviors will benefit (Reach), identifying the critical elements influencing the desired outcomes (Effectiveness), outlining relevant aspects of the delivery environment and staff (Adoption), evaluating adherence to established protocols in intervention delivery (Implementation), understanding the conditions that may impact long-term adoption of the intervention [42]. The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) is a widely used framework that offers a comprehensive taxonomy of operationally defined constructs for understanding the barriers and facilitators that influence implementation success [38]. The CFIR framework consists of five major domains with each domain containing sub-domains and constructs: intervention characteristics, outer setting, inner setting, individuals, and process. CFIR constructs have been used to help inform the design, evaluation, and improvement of implementation strategies [38, 39].

The RE-AIM framework has been successfully used for the evaluation of EHR CDS implementation and translation of healthcare informatics interventions into routine clinical care [43, 44]. Recent studies demonstrated the high potential of the CFIR framework in supporting the implementation of new EHR functionalities while accounting for inner and outer settings [45, 46]. The combined application of the RE-AIM and CFIR frameworks for implementation assessment of clinical informatics programs has been shown to provide the most comprehensive insights on barriers and facilitators affecting the program implementation and to support effective organizational optimization [45, 47, 48]. There is a lack of systematic implementation science studies assessing the implementation of AI-assisted EHR CDS in routine clinical practice. The aim of this study was to methodologically assess the implementation of the 48-h Discharge Prediction Tool and identify the barriers and facilitators of adoption and maintenance using the RE-AIM and CFIR frameworks.

Methods

Study Design

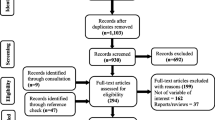

We conducted semi-structured interviews with a participant sample comprised of healthcare workers who represent clinical and administrative stakeholders with a wide range of roles, responsibilities, and years of experience at the Mount Sinai Hospital System (MSHS) in New York City. A purposive sample was recruited from participating hospital units until information saturation or no new relevant information could be identified from the collected data [49]. 24 participants consented and enrolled in the study (See Table 1). The semi-structured interview questions were guided by the Reach, Efficacy, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance (RE-AIM) framework. Questions that pertained to unit-based leadership roles (case manager, social worker, nurse manager, unit medical director, and clinician roles (attending, hospitalist, intern/resident, nurse practitioner, physician assistant were included as part of the Reach and Adoption domains (See Appendix 1: Moderator Guide). The interviews were administered by two trained researchers using video conference software. Each interview was approximately 30 min in duration. The responses to each open-ended interview question were transcribed in Microsoft Word. The study protocol has been approved by the Program of the Protection of Human Subjects (PPHS) at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai (STUDY-20–01955).

Data Analysis

The qualitative data collected from the semi-structured interviews was analyzed using a direct content analysis approach which aims to conceptually validate or expand a theoretical framework or theory [50]. Two researchers thoroughly reviewed the transcripts of each interview and extracted all relevant textual data for input into Microsoft Excel. The raw textual data was organized and deductively coded using a priori codes guided by the five RE-AIM domains: Reach, Efficacy, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance. Additionally, constructs and subconstructs from select CFIR domains (intervention characteristics, inner setting, individual, process, and outcome) were carefully reviewed and mapped onto RE-AIM interview topics (See Appendix 2) [51]. Since the 48DPT was developed and implemented as an internal CDS, the CFIR constructs from the outer setting domain were omitted from the analysis.

Each of the textual data that was coded with a CFIR construct was assigned two ratings, a valence rating (+ , -) based on the perceived positive or negative influence on the implementation of 48DPT, and a strength rating based on the perceived weak (1) strong (2) or neutral (0) influence on the implementation of the 48DPT. Valence and strength ratings were assigned to each construct based on the ratings criteria described by the CFIR framework [52]. Constructs were rated using as having a negative influence (-) were considered as a “barrier” to implementation. Constructs rated as a positive ( +) influence on the implementation of the intervention were considered a “facilitator”. The criteria for the CFIR construct ratings are outlined in Table 1.

The valence and strength ratings across all participants for each CFIR construct were reviewed and identified as a strong facilitator, weak facilitator, strong barrier, weak barrier, and neutral (mixed) based on similar methods and criteria described by Wilson and colleagues [53]. Constructs that received mostly positive valence ratings AND at least 25% of the coded textual data was assigned a strength rating of + 2 were determined to be a “Strong Facilitator”. Constructs that were assigned mostly positive valence ratings but less than 25% of the coded textual data was rated + 2 for strength was considered to be a “Weak Facilitator”. Constructs with mostly negative valence ratings AND at least 25% of the coded textual data was assigned a strength rating of -2 were determined to be a “Strong Barrier” Constructs assigned mostly negative valence ratings but less than 25% of the coded textual data received a -2 strength rating were determined to be a “Weak Barrier”.

Results

A total of 24 participants representing six stakeholder roles including attending, hospitalist/attending, unit medical director, case manager, nurse manager, and social worker.

Participants reported a wide range of years worked at MSHS, 33% have worked for 0 – 1 year, 33% have worked 5 – 10 years, 25% have worked 2 – 4 years, and 9% have worked for more than 10 years (See Table 2).

The results are reported according to the RE-AIM dimensions with relevant CFIR constructs provided for each RE-AIM dimension.

Reach

The Reach domain of the RE-AIM framework examines the motivations for accepting or rejecting the use of the 48DPT. Most participants across stakeholder roles were aware of the existence of the 48DPT. When asked how often the results from the 48DPT are utilized by at least one member of the interdisciplinary team on a given weekday, responses varied by stakeholder role. Among unit-based leadership participants, social workers and case managers reported daily use of the 48DPT. Nurse managers and unit medical director participants rarely used the 48DPT results. Hospitalist/Attending and attending/unit medical director participants also reported minimal use of the 48DPT on a daily basis. The self-report measure of the daily use of the 48DPT aligns with the CFIR construct, Innovation Recipient Impact, which aims to assess the degree to which the innovation impacts the recipients [51]. Since the frequency of use of the 48DPT varied by stakeholder role with social workers and case manager participants reporting daily use and limited use by nurse managers, unit medical director, hospitalists, and attendings, Innovation Recipient Impact was determined to be both a barrier and facilitator (Mixed) of the Reach domain (See Table 3).

When asked if the use of the 48DPT varied by patient factors (e.g., age, race, disease), most participants responded that patient factors had minimal or no influence. Age, disease, and patients with a complicated medical history were reported as factors that may affect the use of the 48DPT. The reported use of the 48DPT in consideration of patient factors aligns with the Innovation Adaptability CFIR construct which assesses the degree to which the intervention can be modified, tailored, or refined to fit local context or needs. Use of the 48DPT may differ based on age and disease as reported by a few participants indicating the presence of the Innovation Adaptability construct. However, since the patient factors did not influence the remainder of the participants, Innovation Adaptability was considered neither a barrier nor facilitator (Mixed) to the reach domain (See Table 3).

Unit-based leadership participants were asked if there are particular clinician groups or teams that are more or less likely to utilize the 48DPT. Responses reveal that social worker and case manager participants were more likely to use the 48DPT. Case managers often used the 48DPT as a reference point to initiate the discussion of a patient who was identified as ready for discharge during interdisciplinary rounds. For social workers, the 48DPT served as a prompt to start preparations for the discharge of a patient. Nursing was reportedly less likely to use the 48DPT and preferred to use Discharge Today, an existing discharge functionality embedded into Epic EHR. The implementation of the 48DPT differed between case managers and social workers as the information generated by them resulted in separate action steps. The varying uses of the 48DPT within different stakeholder roles indicate the presence of the Tailoring Strategies CFIR construct. This construct represents how individuals select and implement strategies to overcome barriers, utilize facilitators, and match context. Findings from the interviews indicate that the presence of the Tailoring Strategies constructs among the stakeholder roles was modest and only associated with case managers and social workers. The construct was absent in hospitalist, attending, unit medical directors, and nurse manager participants. Therefore, Tailoring Strategies was determined to be a weak facilitator to the reach of the 48DPT (See Table 3).

Efficacy

The Efficacy domain of the RE-AIM framework focuses on understanding the overall impact of the implementation process on primary and secondary outcomes. Participants were asked to share their thoughts about the impact of using the 48DPT process on specific outcomes. Assessing the impact of the 48DPT on specific outcomes aligns with the Reflecting & Evaluating CFIR construct. Reflecting & Evaluating is described as the extent to which individuals collect and discuss quantitative and qualitative data concerning implementation progress. The Reflecting & Evaluating construct was expanded to be assessed across five subconstructs; Perceived effectiveness, Personal judgement, Length of Stay, Initiation of discharge process, and Clinical/Patient outcomes.

Regarding how effective or accurate the 48DPT is in determining patients who are medically ready for discharge, unit-based leadership and clinician participants differed in their responses (Reflecting & Evaluating: Perceived effectiveness). Hospitalists responded that the 48DPT was accurate 60 – 70% of the time. Social workers stated that the 48DPT is effective but not consistently accurate and case managers reported that the 48DPT was accurate within an estimated range of 60%—80%. Additional responses included a lack of training or use of the 48DPT and a preference for the Discharge Today, the functionality that existed in Epic before 48DPT implementation.

When asked to compare the accuracy of the 48DPT to their personal/clinical judgment some participants (social workers, case managers, hospitalists) thought the 48DPT was about the same or slightly better at predicting discharge than their personal/clinical judgment (Reflecting & Evaluating: Personal judgment). One participant (unit medical director) thought clinical judgment was better at predicting discharge. A few social workers mentioned that the accuracy of the 48DPT result varies especially when a patient becomes medically active and the case is referred to the medical team for review. Participants were asked if the 48DPT helped decrease the Length of Stay (LOS) (Reflecting & Evaluating: Length of stay). Several participants (hospitalists, attendings, case managers, and nurse manager) responded favorably explaining that it prompts the team to initiate the discharge process earlier. Unit medical directors and social workers did not think the 48DPT helped decrease LOS as social work follow-up is needed for many patients.

Participants were asked if the 48DPT helps initiate the processes needed for discharge (e.g., scheduling appointments, and communication with outpatient providers) (Reflecting & Evaluating: Initiation of discharge process). Several participants (attendings, unit medical directors, case managers, and social workers) responded positively and thought that the 48DPT could help start the discharge process. Additionally, they reported seeing an improvement with the use of the 48DPT when asked if the 48DPT helps improve clinical care or patient outcomes (Reflecting & Evaluating: Clinical/Patient Outcomes). These participants attributed the improvement to the ability to discuss the discharge process and start preparation in a timely manner. In contrast, two attendings did not think the clinical care or patient outcomes would improve with the use of the 48DPT based on their experience.

The responses detailed above indicate the presence of each of the subconstructs for Reflecting & Evaluating as a facilitator or positive influence on the effectiveness of the 48DPT implementation process. However, since several hospitalists/attending participants reported having limited experience with the 48DPT, each of the five subconstructs was determined to be a weak facilitator of the efficacy domain (See Table 4).

The Relative Advantage construct aims to assess the performance of an intervention in comparison to current practices or alternate solutions [38]. The relative advantage construct was expanded into two subconstructs, Familiarity with Discharge Today and Perceived Value compared to Discharge Today, to examine the performance of the 48DPT compared to Discharge Today (DT), an embedded CDS tool available in Epic EHR.

Participants were asked about their awareness and experience with the DT (Relative advantage: Familiarity with Discharge Today). All participants reported being aware of the existence of the “Discharge Today” field in Epic before the study. Hospitalist, attending, unit medical director, and nurse manager participants preferred using DT in their clinical workflow while social worker and case manager participants preferred the 48DPT. These responses suggest that awareness of the DT tool is a negative influence, or barrier, to the implementation of the 48DPT. The Relative advantage: Familiarity with Discharge Today subconstruct was identified as a weak barrier because familiarity with the DT tool did not deter the adoption of the 48DPT by social workers and case managers.

When participants were asked which of the two tools was more beneficial, if the tools were redundant, or whether they each provided unique information, responses across the stakeholder roles were mixed (Relative advantage: Perceived value compared to Discharge Today). Attending, unit medical director, case manager, and nurse manager participants thought that information from the 48DPT differed from the DT tool. In contrast, Hospitalist and Social worker participants stated that information from 48DPT overlaps with information from DT and interdisciplinary rounds (IDR). Two hospitalists responded that interdisciplinary rounds (IDRs) are sufficient in determining which patients are medically ready for discharge and that both the DT tool and the 48DPT are redundant. These findings indicate several participants found the information generated by the 48DPT to be redundant with the information from the DT and IDRs which can negatively influence implementation. However, this did not deter participants from adopting the 48DPT. Therefore, the Relative advantage: Perceived value compared to the Discharge Today subconstruct was rated as a weak barrier to the implementation of the 48DPT (See Table 4).

Adoption

The Adoption domain examines 48DPT usage patterns at the individual and unit levels, as well as the acceptance of participants across medical specialties and levels of clinical experience. Understanding the intended use of an intervention aligns with the Adapting construct which measures the degree to which individuals modify the innovation and/or the Inner Setting for optimal fit and integration into work processes [38]. The Adapting construct was expanded into two subconstructs to assess the Individual intended use and the Unit-based intended use of the 48DPT. When asked about the use of the 48DPT, most participants responded that the 48DPT is used as originally intended (Adapting: Individual Intended Use). A few social worker participants were unsure if the 48DPT was being used as intended. We asked hospitalists if the use of 48DPT varied by unit and one stated that the use of the 48DPT differed across hospital units depending on the role and integration with IDRs (Adapting: Unit-based intended use).

The findings discussed above indicate the presence of both Adapting subconstructs as a facilitator or positive influence on the implementation and adoption of the 48DPT. The Adapting: Individual Intended Use and Adapting: Unit-based intended use subconstructs were identified as weak facilitators of implementation because several hospitalists had awareness of the 48DPT but did not have experience using the tool (See Table 5).

The Knowledge & Beliefs CFIR construct aims to seek to examine the views and the value placed on the intervention including the familiarity with facts, truths, and principles [38]. The Knowledge & Beliefs were adapted to be assessed across four subconstructs; Clinician response to 48DPT, Response to 48DPT by clinician role, Response to 48DPT by specialty or roles, and Response to 48DPT by clinician's time in practice.

Participants in unit-based leadership roles (social workers, case managers, and unit medical directors) were asked to discuss how clinicians might react or respond if a team member announces that a discharge is predicted within the next 48 h (Knowledge & Beliefs: Clinician response to 48DPT). Most unit-based leadership participants reported that team members would be accepting and welcoming to the information. They mentioned that clinician reactions to a 48DPT result may vary depending on the clinician's role (Knowledge & Beliefs: Response to 48DPT by clinician role) and the medical specialty (Knowledge & Beliefs: Response to 48DPT by specialty or roles).

These findings suggest the presence of the Knowledge & Beliefs: Clinician response to 48DPT, Knowledge & Beliefs: Response to 48DPT by clinician role, and Knowledge & Beliefs: Response to 48DPT by specialty or role subconstructs as a facilitator or positive influence on the implementation and adoption of the 48DPT. These subconstructs were recognized as weak facilitators of implementation since some hospitalists and attendings did not use the 48DPT regularly despite having knowledge about the existence of the tool (See Table 5).

When asked if the response to the 48DPT varied according to clinician’s time in practice, two unit-based leadership participants mentioned that newer clinicians are more likely to not be aware of the 48DPT compared to more experienced clinicians (Knowledge & Beliefs: Response to 48DPT by clinician's time in practice). The lack of awareness about the 48DPT by clinicians with limited time in practice was determined to be a barrier to implementation and adoption. Since the limited knowledge did not deter the adoption of the 48DPT by less experienced clinicians, the Knowledge & Beliefs: Response to 48DPT by clinician's time in practice subconstruct was rated as a weak barrier (See Table 5).

Implementation

The Implementation domain of the RE-AIM framework aims to understand the enabling and predisposing factors that support the implementation of the 48DPT. Assessing the enabling and predisposing factors aligns with the Engaging CFIR construct. This construct refers to the degree to which individuals attract and promote involvement in the implementation process and/or the intervention [38]. The Engaging construct was expanded to two subconstructs to examine its presence or absence in Individuals and Interdisciplinary Team Members. Participants were asked if they were involved in developing the process for the use of the 48DPT (Engaging: Individuals). Most participants responded that they were not involved in the development process. These responses reveal that the Engaging: Individuals subconstruct was largely absent. However, the lack of participation in the development did not hinder the adoption of the 48DPT by several participants. Therefore, the Engaging: Individuals subconstruct was rated as a weak barrier to the Implementation domain (See Table 6).

Participants were asked about the involvement of interdisciplinary team members (e.g., case managers, nurse managers, and clinicians) in the development process of the 48DPT (Engaging: Interdisciplinary Team Members). The majority of participants reported having no knowledge of the 48DPT development process or if other team members were involved. A few participants did not think that the interdisciplinary team was adequately involved. Case manager and nurse manager participants responded that the involvement of interdisciplinary team members in the development of the 48DPT was satisfactory. These findings suggest that stakeholder engagement was limited and the lack of involvement of interdisciplinary team members is a negative influence on adoption. Participants were either unaware of the development phase and the involvement of other team members or did not think the efforts to involve team members were sufficient. Therefore, the Engaging: Interdisciplinary Team Members subconstruct was determined to be a strong barrier to implementation (See Table 6).

The Compatibility CFIR construct looks at how effectively the intervention fits with current processes, systems, and practices [38]. When asked if the 48DPT was integrated well into their workflow, the responses across roles were mixed. Several participants (unit medical director, and nurse manager) responded that the 48DPT was not adopted into their workflow. These participants suggested providing training and reminders about the availability of the tool to improve integration. Some hospitalists and attendings thought that the 48DPT was somewhat integrated into their workflow due to a lack of follow-up education and efforts to increase awareness of the 48DPT after the initial rollout. A few case managers and social workers reported that the 48DPT was well-integrated. These varied responses indicate that the Compatibility construct did not have a positive or negative influence on the implementation domain and was determined to be neither a barrier nor a facilitator (Mixed) (See Table 6).

Participants were asked what support services and technical skills are needed by users of the 48DPT. This question corresponds with the Access to Knowledge & Information CFIR construct which seeks to assess the degree to which guidance and/or training are available for intervention implementation. The Access to Knowledge & Information construct was expanded into two subconstructs to evaluate the Training and Support and Computer skills required for the use of the 48DPT. In regard to support services, increasing awareness about the availability of the 48DPT was highlighted by several participants. Additionally, participants suggested providing training and demonstration for each member of the interdisciplinary team and improving the accuracy of the 48DPT. A few participants thought the 48DPT was intuitive to use and did not require additional training or support. These responses indicate the presence of the Access to Knowledge & Information: Training and Support subconstruct as a weak facilitator of the implementation domain (See Table 6).

When asked what computer skills were necessary to successfully use the 48DPT, most participants stated that basic computer skills are needed. Participants were also familiar with the general operation of the 48DPT because of their prior experience using similar programs and in their clinical workflow. These findings reveal the presence of Access to Knowledge & Information: Computer Skills subconstruct as a facilitator or positive influence on the implementation of the 48DPT. Because the majority of participants reported possessing the requisite technical abilities for the successful deployment of the 48DPT, this subconstruct was evaluated as a strong facilitator (See Table 6).

Maintenance

The Maintenance domain of the RE-AIM framework investigates the degree to which the 48DPT is assimilated into organizational culture and routine practice. Examining the factors related to the success of the implementation of an intervention aligns with the Assessing Context CFIR construct. The Assessing Context construct aims to assess the extent to which individuals gather information to recognize and evaluate obstacles and enablers for implementing and delivering the innovation [38]. This construct was broadened to be examined across four subconstructs; Perceived burden, Comparison of perceived benefits to burden, Perceived barriers, and Use of 48DPT over time.

Participants were asked how much of a burden using the 48DPT. Eight participants responded that the use of the 48DPT did not add a burden. When asked to compare the burden of using the 48DPT to the benefits, the majority of participants responded that the benefits outweigh any burden (Assessing Context: Comparison of perceived benefits to burden). Findings from these responses indicate the presence of the Assessing Context: Perceived burden and Assessing Context: Comparison of perceived benefits to burden subconstructs as facilitators or positive influences on the implementation and maintenance of the 48DPT. Overall, participants did not find the 48DPT to be burdensome and agreed that the benefits of using the tool overshadowed any difficulties. Therefore, the Assessing Context: Perceived burden and Assessing Context: Comparison of perceived benefits to burden subconstructs were rated as strong facilitators of 48DPT implementation (See Table 7).

When asked about the barriers to using the 48DPT, participants most frequently mentioned the lack of awareness of the tool (Assessing Context: Perceived barriers). Additional reported barriers were the lack of educational training, limited integration into IDRs, and difficulty communicating with providers. These results reveal the prevalence of the Assessing Context: Perceived barriers subconstruct and barriers such as lack of awareness about 48DPT pose a negative influence on adoption. Therefore, Assessing Context: Perceived barriers were identified as a strong barrier to the implementation of the 48DPT (See Table 7).

Participants were asked if the use of the 48DPT changed over time. Most participants responded that the use of the 48DPT has not changed since their initial use. This question was omitted for participants who reported having limited familiarity with the use of the 48DPT. These responses indicate the absence of the Assessing Context: Use of 48DPT over time subconstruct which is deemed as a barrier. Since a number of participants had minimal experience with the 48DPT, the Assessing Context: Use of 48DPT over time subconstruct was identified as a weak barrier to the implementation and maintenance of the 48DPT (See Table 7).

The Goals & Feedback CFIR construct refers to the degree to which objectives are explicitly stated, acted upon, and given back to team members, as well as the alignment of that feedback with goals [38]. When asked if any efforts were made to obtain feedback about the 48DPT in order to make changes, a few participants reported attempts from leaders. Most participants were not aware of any opportunities to share their feedback about the 48DPT with leaders. The findings from these responses reveal that the presence of the Goals and feedback construct was minimal. The limited efforts to gather feedback and address concerns about the use of 48DPT were determined to be a barrier or negative influence on the implementation process of the 48DPT. Therefore, the Goals & Feedback construct was recognized as a strong barrier (See Table 7).

The Available Resources CFIR construct examines the availability of resources to implement and deliver the innovation. We asked participants if any tools helped improve their use of the 48DPT (e.g., training sessions, individual feedback, unit-based metrics). The unit-based metrics and feedback and discussions with the clinical team about discharge were found to be helpful for some participants. Most participants did not report any tools that were beneficial or did not have extensive experience with the 48DPT. These results highlight the absence of the Available Resources construct which is deemed as a negative influence or barrier to implementation. However, the lack of accessibility to support the use of the 48DPT did not hinder the implementation and adoption. Therefore, the Available Resources construct was recognized as a weak barrier (See Table 7).

Participants were asked how the use of the 48DPT could be improved. This question corresponds with the Assessing Needs: Innovation Recipients construct which aims to examine the extent to which the individual(s) gather information about the priorities, preferences, and needs of recipients to guide the implementation and delivery of the intervention. Increasing awareness and education of the 48DPT was a frequent suggestion, especially among hospitalists, nurse managers, and social workers. Participants also suggested including consideration of social factors as part of the algorithm and improving the accuracy of the 48DPT. This question was omitted for participants who reported having minimal use of the 48DPT. Findings from these responses suggest the presence of the Assessing Needs: Innovation Recipients construct as a facilitator or positive influence on the implementation process. A few participants had minimal experience with the 48DPT, therefore the Assessing Needs: Innovation Recipients construct was rated as a weak facilitator to the implementation and maintenance.

Discussion

The current study sought to methodologically evaluate the implementation of a AI-assisted CDS known as the 48-h discharge prediction (48DPT) which utilizes available patient EHR data to predict readiness for discharge. The RE-AIM (Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance) framework was applied in combination with the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) framework to examine the factors that impact the implementation of the 48DPT. Semi-structured qualitative interviews based on the RE-AIM framework were conducted with 24 healthcare professionals consisting of clinical and administrative stakeholders with a range of roles, duties, and years employed. Guidelines from the CFIR framework informed the analysis of the qualitative interview data using a content analysis methodology. The findings identified several facilitators and barriers which were summarized and reported using the RE-AIM dimensions.

The Reach domain explores the factors related to accepting or rejecting the usage of the 48DPT at an individual level. The variation in the adoption of the 48DPT across stakeholder roles demonstrated differing perspectives, which corresponded with the CFIR construct, Innovation Recipient Impact, and was determined to be neither a facilitator nor barrier factor to implementation. While Hospitalists/Attendings described seldom use of the tool, indicating an inherent challenge, Social Workers and Case Managers reported regular use of the 48DPT, indicating a positive influence. The Capability construct emerged as a strong barrier to implementation due to the reported lack of awareness about the 48DPT. The Innovation Adaptability construct was determined as neither a barrier nor a facilitator in the study, indicating that patient variables had a minimal impact on the use of the 48DPT. The Tailoring Strategies construct was observed among Case Managers and Social workers but not in other stakeholder roles. This absence implies a weak facilitator to adjust the use of the 48DPT to meet the contextual needs of stakeholders.

The overall impact of the implementation of the 48DPT on key outcomes was examined as part of the Efficacy domain. The Reflecting & Evaluating construct was examined across five subconstructs; Perceived effectiveness, Personal judgement, Length of Stay, Initiation of discharge process, and Clinical/Patient outcomes. Each subconstruct was recognized to be a weak facilitator due to the varying perceptions of the effectiveness of the 48DPT across stakeholders. The Relative Advantage construct which compared the performance of the 48DPT with an existing (Discharge Today) was expanded into two subconstructs; Familiarity with Discharge Today and Perceived value compared to Discharge Today). Participants across stakeholder roles were aware of the Discharge Today. Participants in the Hospitalist/Attending, Attendings/Unit Medical Director, Unit Medical Director, and Nurse Manager groups favored employing Discharge Today in their clinical workflow, but participants in the Social Worker and Case Manager groups preferred using the 48DPT. Therefore, the Familiarity with Discharge Today subconstruct was identified as a weak barrier. The Perceived value compared to the Discharge Today subconstruct was determined to be a weak barrier because several participants viewed the information provided by the 48DPT to be redundant with information from the Discharge Today and Interdisciplinary Rounds, which can have a detrimental impact on implementation. These findings highlight the need for clear communication on the unique benefits of the 48DPT.

The Adoption domain investigated the usage patterns and acceptance across medical specialties at the individual and unit levels. The Adapting construct was identified as a weak facilitator at both individual and unit levels, suggesting that stakeholders generally used the 48DPT as intended. The Knowledge & Beliefs construct was examined across four subconstructs. The Clinician response to 48DPT, Response to 48DPT by clinician role, and Response to 48DPT by specialty or roles subconstructs were identified as weak facilitators to implementation revealing positive perceptions and general acceptance of the information provided by the 48DPT. Newer clinicians were reported less likely to.be aware about the 48DPT compared to clinicians with more experience, therefore the Response to 48DPT by clinician's time in practice was recognized Overall, the findings from the Adoption domain emphasize the importance of stakeholder education and awareness for successful adoption.

The Implementation domain focuses on enabling and predisposing factors related to implementation. The Engaging: Individuals and Engaging: Interdisciplinary Team Members subconstructs examined the involvement of stakeholders in the development and implementation process of the 48DPT and were identified as strong barriers. Lack of stakeholder involvement can significantly hinder the implementation and adoption. The Compatibility construct was neither a barrier nor a facilitator, which indicates the clinical workflow integration of the 48DPT varied among participants. The Access to Knowledge & Information construct, which assesses the guidance/training resources necessary for the use of 48DPT, was expanded into two subconstructs. The Training and Support subconstruct was identified as a weak facilitator due to the prevalence of the construct and range of responses including suggestions to increase awareness of 48DPT, improve the accuracy of the 48DPT, provide comprehensive training for each team member, and additional training was not necessary. Participants reported basic computer skills are needed for the use of the 48DPT which was recognized as a strong facilitator to implementation.

Lastly, the Maintenance domain investigates the factors influencing the assimilation of the 48DPT into routine practice. The Assessing Context construct which examines the extent to which feedback is gathered to understand the implementation process to improve delivery and adoption was expanded into four subconstructs. The Perceived burden and Comparison of perceived benefits to burden subconstructs demonstrated positive perceptions of the 48DPT’s benefits outweighing any perceived burden, acting as strong facilitators to implementation. The Perceived barriers subconstruct was identified as a strong barrier due to the reported lack of awareness, lack of educational training, and limited integration. The absence of the Use of 48DPT over time subconstruct was recognized as a weak barrier. The Available Resources construct was identified as a weak barrier, suggesting that despite the absence of accessible s, participants still successfully adopted the 48DPT. The Assessing Needs: Innovation Recipients construct acted as a weak facilitator, indicating the potential for improvement through increased awareness and education. The Goals & Feedback construct revealed the lack of a feedback mechanism and limited efforts to address needs and concerns about the use of 48DPT which was considered to be a strong barrier to implementation.

The combination of the RE-AIM and CFIR frameworks has been applied to assess the implementation planning process. For example, Breathewell, an internally developed intervention for asthma care, has been evaluated in an integrated healthcare organization setting [45]. Breathewell is a technology-based asthma intervention that was planned and implemented by a multi-disciplinary team of researchers and healthcare professionals at Kaiser Permanente Colorado [45]. Researchers selected the RE-AIM framework to investigate the “who, what, where, how, and when” of the implementation outcomes for the Breathewell intervention. Specific domains and constructs were chosen from the CFIR framework to understand “why” the implementation of the Breathewell intervention was successful or unsuccessful [42, 54]. Findings from the assessment highlighted the determinants that supported the diffusion or “pull” factors and the dissemination or “push” factors associated with the implementation of the intervention [42]. Push factors refer to systematic initiatives aimed at eliciting engagement from potential adopters. Pull factors refer to the preexisting perceptions, requirements, and capacities of potential adopters that motivate change and indicate successful diffusion [54].

Applying the RE-AIM and CFIR frameworks in tandem to assess the implementation of the 48DPT allowed for a comprehensive evaluation that integrated both outcome measurement and the identification of factors influencing those outcomes. The RE-AIM framework allowed for the systematic measurement of critical dimensions such as reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, and maintenance. These dimensions are essential for understanding the broader public health impact of an intervention. However, while RE-AIM is robust in addressing these aspects, it does not inherently explain the factors influencing these outcomes. The CFIR framework complemented RE-AIM by offering a structured way to identify and analyze the contextual and organizational factors that could act as barriers or facilitators to successful implementation. By integrating CFIR constructs, we investigated the reasons behind the success or failure of certain RE-AIM outcomes. This allowed us to gather insights into the particular context of the 48DPT implementation, including organizational culture, leadership involvement, and the fit of the 48DPT within existing workflows. The use of a dual-framework approach enabled a deeper understanding of both the effectiveness and the underlying mechanisms that influenced the implementation of the 48DPT. This allows for the development of new strategies to improve the adoption and maintenance of an AI-assisted EHR CDS tool.

The barriers and facilitators identified by the RE-AIM and CFIR frameworks can help improve the development and implementation strategies of an AI-assisted EHR CDS tool. Our findings highlighted a significant need for early engagement of stakeholders. The involvement of a diverse group of clinicians during the initial development phase ensures that the tool fits the needs of varying clinical workflows. Feedback from the end users or the clinicians for whom the tool is intended should guide the design of the CDS interface. A user-focused design approach ensures that the tool is intuitive, integrates seamlessly into existing workflows, and addresses the specific needs and preferences of the end users. Continuous training and education are essential to the successful integration of the tool. Educating clinicians on the CDS tool's overall usage, important AI principles like biases and limitations, and how these technologies can improve clinical decision-making can help empower them to use it more effectively. Establishing a feedback mechanism that continuously gathers input and suggestions from clinicians ensures that the CDS tool remains beneficial and effective. By consistently seeking and integrating user feedback, the tool can be improved over time, becoming more adaptable to the evolving needs of end users and maintaining its overall utility. Highlighting and disseminating successful examples of an AI-assisted CDS in action can greatly encourage its broader adoption. Sharing these use cases via media, presentations, and institutional rounds can help illustrate the practical benefits of the AI-assisted EHR CDS tool. This can help bolster confidence among potential users and promote a culture of innovation. Due to the 'black box' nature of AI applications, a high degree of explainability and transparency is necessary to develop trust in AI-assisted tools. Improving the tool's accuracy and providing clear explanations and visualizations of how the AI makes decisions fosters confidence in the tool. End users are more inclined to trust and integrate the tool into their clinical workflow when they can see how the AI operates internally and comprehend the reasoning behind its recommendations. Maintaining and respecting clinician autonomy in their decision-making is crucial. It is imperative to clearly describe that the AI-assisted CDS is a supplementary tool intended to complement healthcare providers' judgment, not to take its place. Long-term maintenance of the AI-assisted CDS tool requires strong and consistent support from institutional leadership. In addition to providing the infrastructure and resources necessary for adoption, leadership endorsement informs the organization as a whole about the importance of the tool. The successful implementation of an AI-assisted tool requires cultivating a culture that values innovation and continuous learning. An organization is more receptive to change when a philosophy of experimenting, learning from mistakes, and adapting to new technologies is encouraged.

This is the first study that systematically evaluated the implementation process of internally developed AI-assisted EHR CDS aimed at predicting discharge date using a combination of implementation science frameworks RE-AIM and CFIR. Previous studies utilized qualitative interviews for assessing challenges to AI implementation in healthcare without aligning their analyses with existing implementation science frameworks [55,56,57]. The addition of widely recognized dimensions and constructs from implementation science facilitates comparison between various studies and different implementation programs [58, 59]. The results of our study are well aligned with the previous findings emphasizing the crucial importance of sociotechnical factors and specific workflow contexts for long-term success of EHR CDS implementation and its impact on routine clinical care [60, 61]. The systematic assessment of the 48DPT implementation allowed the identification of facilitators and barriers to implementation, such as lack of awareness, lack of accuracy, limited accessibility, and transparency. These findings are summarized in Figs. 1, 2, 3. Based on our evaluation, the factors that are crucial for the successful implementation of AI-assisted EHR CDS are presented in Table 8. Future implementation efforts of AI-assisted EHR CDS should engage the key clinical stakeholders in the AI tool development from the very inception of the project, support transparency and explainability of the AI models, provide ongoing education and onboarding of the clinical users, and obtain continuous input from clinical staff on the CDS performance.

Data Availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Sim I, Gorman P, Greenes RA, et al. Clinical decision support systems for the practice of evidence-based medicine. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2001;8(6):527-534.

Pryor TA. Development of decision support systems. International journal of clinical monitoring and computing. 1990;7(3):137-146.

Jia P, Zhang L, Chen J, Zhao P, Zhang M. The effects of clinical decision support systems on medication safety: an overview. PloS one. 2016;11(12):e0167683.

Kwok R, Dinh M, Dinh D, Chu M. Improving adherence to asthma clinical guidelines and discharge documentation from emergency departments: implementation of a dynamic and integrated electronic decision support system. Emergency Medicine Australasia. 2009;21(1):31-37.

Calloway S, Akilo HA, Bierman K. Impact of a clinical decision support system on pharmacy clinical interventions, documentation efforts, and costs. Hospital pharmacy. 2013;48(9):744-752.

Greenes R. Clinical decision support: the road to broad adoption. Academic Press; 2014.

Sutton RT, Pincock D, Baumgart DC, Sadowski DC, Fedorak RN, Kroeker KI. An overview of clinical decision support systems: benefits, risks, and strategies for success. NPJ digital medicine. 2020;3(1):17.

Harrison P, Hasan R, Park K. State-of-the-Art of Breast Cancer Diagnosis in Medical Images via Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs). J Healthc Inform Res. 2023 Sep 10;7(4):387-432.

Riedel P, von Schwerin R, Schaudt D, Hafner A, Späte C. ResNetFed: Federated Deep Learning Architecture for Privacy-Preserving Pneumonia Detection from COVID-19 Chest Radiographs. J Healthc Inform Res. 2023 Jun 14;7(2):203-224.

Zaghir J, Rodrigues-Jr JF, Goeuriot L, Amer-Yahia S. Real-world Patient Trajectory Prediction from Clinical Notes Using Artificial Neural Networks and UMLS-Based Extraction of Concepts. J Healthc Inform Res. 2021 Jun 5;5(4):474-496.

Topol EJ. High-performance medicine: the convergence of human and artificial intelligence. Nature medicine. 2019;25(1):44-56.

Schaaf J, Sedlmayr M, Schaefer J, Storf H. Diagnosis of Rare Diseases: a scoping review of clinical decision support systems. Orphanet journal of rare diseases. 2020;15(1):1-14.

Yassin NI, Omran S, El Houby EM, Allam H. Machine learning techniques for breast cancer computer aided diagnosis using different image modalities: A systematic review. Computer methods and programs in biomedicine. 2018;156:25-45.

Pawloski PA, Brooks GA, Nielsen ME, Olson-Bullis BA. A systematic review of clinical decision support systems for clinical oncology practice. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2019;17(4):331-338.

Fitriyani NL, Syafrudin M, Alfian G, Rhee J. HDPM: an effective heart disease prediction model for a clinical decision support system. IEEE Access. 2020;8:133034-133050.

Sim LLW, Ban KHK, Tan TW, Sethi SK, Loh TP. Development of a clinical decision support system for diabetes care: A pilot study. PloS one. 2017;12(2):e0173021.

Pedersen M, Verspoor K, Jenkinson M, Law M, Abbott DF, Jackson GD. Artificial intelligence for clinical decision support in neurology. Brain communications. 2020;2(2):fcaa096.

Velickovski F, Ceccaroni L, Roca J, et al. Clinical Decision Support Systems (CDSS) for preventive management of COPD patients. Journal of translational medicine. 2014;12:1-10.

Wang F, Preininger A. AI in health: state of the art, challenges, and future directions. Yearbook of medical informatics. 2019;28(01):016-026.

Khairat S, Marc D, Crosby W, Al Sanousi A. Reasons for physicians not adopting clinical decision support systems: critical analysis. JMIR medical informatics. 2018;6(2):e8912.

Kelly CJ, Karthikesalingam A, Suleyman M, Corrado G, King D. Key challenges for delivering clinical impact with artificial intelligence. BMC Med. 2019 Oct 29;17(1):195.

Ahmed MI, Spooner B, Isherwood J, Lane M, Orrock E, Dennison A. A Systematic Review of the Barriers to the Implementation of Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare. Cureus. 2023 Oct 4;15(10):e46454.

Magrabi F, Ammenwerth E, McNair JB, De Keizer NF, Hyppönen H, Nykänen P, Rigby M, Scott PJ, Vehko T, Wong ZS, Georgiou A. Artificial Intelligence in Clinical Decision Support: Challenges for Evaluating AI and Practical Implications. Yearb Med Inform. 2019 Aug;28(1):128-134.

Musa IH, Afolabi LO, Zamit I, Musa TH, Musa HH, Tassang A, Akintunde TY, Li W. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Cancer Research: A Systematic and Thematic Analysis of the Top 100 Cited Articles Indexed in Scopus Database. Cancer Control. 2022;29:10732748221095946.

Hong JC, Eclov NCW, Stephens SJ, Mowery YM, Palta M. Implementation of machine learning in the clinic: challenges and lessons in prospective deployment from the System for High Intensity EvaLuation During Radiation Therapy (SHIELD-RT) randomized controlled study. BMC Bioinformatics. 2022 Sep 30;23(Suppl 12):408.

Saw SN, Ng KH. Current challenges of implementing artificial intelligence in medical imaging. Phys Med. 2022 Aug;100:12-17.

Khan B, Fatima H, Qureshi A, Kumar S, Hanan A, Hussain J, Abdullah S. Drawbacks of Artificial Intelligence and Their Potential Solutions in the Healthcare Sector. Biomed Mater Devices. 2023 Feb 8:1-8.

Dankwa-Mullan I, Weeraratne D. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Technologies in Cancer Care: Addressing Disparities, Bias, and Data Diversity. Cancer Discov. 2022 Jun 2;12(6):1423-1427.

Cha E, Golden SH, Finkelstein J. Unanticipated consequences of hospital-based insulin management order sets. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2015;216:939.

Janssen A, Kay J, Talic S, Pusic M, Birnbaum RJ, Cavalcanti R, Gasevic D, Shaw T. Electronic Health Records That Support Health Professional Reflective Practice: a Missed Opportunity in Digital Health. J Healthc Inform Res. 2023 Jan 20;6(4):375-384.

Salwei ME, Carayon P. A Sociotechnical Systems Framework for the Application of Artificial Intelligence in Health Care Delivery. J Cogn Eng Decis Mak. 2022 Dec;16(4):194-206.

Bedra M, Hill Golder S, Cha E, et al. Computerized Insulin Order Sets Can Lead to Unanticipated Consequences. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2015;213:53-6. PMID: 26152951.

Campagna V, Nelson SA, Krsnak J. Improving Care Transitions to Drive Patient Outcomes: The Triple Aim Meets the Four Pillars. Prof Case Manag. 2019 Nov/Dec;24(6):297-305.

Kripalani S, Jackson AT, Schnipper JL, Coleman EA. Promoting effective transitions of care at hospital discharge: a review of key issues for hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2007 Sep;2(5):314-23.

Bhamidipati VS, Elliott DJ, Justice EM, Belleh E, Sonnad SS, Robinson EJ. Structure and outcomes of interdisciplinary rounds in hospitalized medicine patients: A systematic review and suggested taxonomy. J Hosp Med. 2016 Jul;11(7):513-23.

Huijg JM, Crone MR, Verheijden MW, van der Zouwe N, Middelkoop BJ, Gebhardt WA. Factors influencing the adoption, implementation, and continuation of physical activity interventions in primary health care: a Delphi study. BMC family practice. 2013;14(1):1-9.

King DK, Neander LL, Edwards AE, Barnett JD, Zold AL, Hanson BL. Fit and feasibility: adapting a standardized curriculum to prepare future health professionals to address alcohol misuse. Pedagogy in Health Promotion. 2019;5(2):107-116.

Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation science. 2009;4(1):1-15.

Keith RE, Crosson JC, O’Malley AS, Cromp D, Taylor EF. Using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) to produce actionable findings: a rapid-cycle evaluation approach to improving implementation. Implementation Science. 2017;12(1):1-12.

Holtrop JS, Estabrooks PA, Gaglio B, et al. Understanding and applying the RE-AIM framework: clarifications and resources. Journal of Clinical and Translational Science. 2021;5(1):e126.

Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. American journal of public health. 1999;89(9):1322-1327.

Glasgow RE, Harden SM, Gaglio B, et al. RE-AIM planning and evaluation framework: adapting to new science and practice with a 20-year review. Frontiers in public health. 2019;7:64.

Masterson Creber RM, Dayan PS, Kuppermann N, Ballard DW, Tzimenatos L, Alessandrini E, Mistry RD, Hoffman J, Vinson DR, Bakken S. Pediatric emergency care applied research network (PECARN) and the clinical research on emergency services and treatments (CREST) network. Applying the RE-AIM framework for the evaluation of a clinical decision support tool for pediatric head trauma: A mixed-methods study. Appl Clin Inform. 2018 Jul;9(3):693–703.

Bakken S, Ruland CM. Translating clinical informatics interventions into routine clinical care: how can the RE-AIM framework help? J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2009 Nov-Dec;16(6):889-97.

King DK, Shoup JA, Raebel MA, et al. Planning for implementation success using RE-AIM and CFIR frameworks: a qualitative study. Frontiers in public health. 2020;8:59.

Touson JC, Azad N, Beirne J, Depue CR, Crimmins TJ, Overdevest J, Long R. Application of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research Model to Design and Implement an Optimization Methodology within an Ambulatory Setting. Appl Clin Inform. 2022 Jan;13(1):123-131.

Aerts N, Van Royen K, Van Bogaert P, Peremans L, Bastiaens H. Understanding factors affecting implementation success and sustainability of a comprehensive prevention program for cardiovascular disease in primary health care: a qualitative process evaluation study combining RE-AIM and CFIR. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2023 Mar 8;24:e17.

Konrad LM, Ribeiro CG, Maciel EC, Tomicki C, Brito FA, Almeida FA, Benedetti TRB. Evaluating the implementation of the active life improving health behavior change program "BCP-VAMOS" in primary health care: Protocol of a pragmatic randomized controlled trial using the RE-AIM and CFIR frameworks. Front Public Health. 2022 Sep 12;10:726021.

Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. sage; 1994.

Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative health research. 2005;15(9):1277-1288.

Damschroder LJ, Reardon CM, Widerquist MAO, Lowery J. The updated Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research based on user feedback. Implementation science. 2022;17(1):75.

Damschroder LJ, Lowery JC. Evaluation of a large-scale weight management program using the consolidated framework for implementation research (CFIR). Implementation Science. 2013;8:1-17.

Wilson HK, Wieler C, Bell DL, Bhattarai AP, Castillo-Hernandez IM, Williams ER, Evans EM, Berg AC. Implementation of the diabetes prevention program in georgia cooperative extension according to RE-AIM and the consolidated framework for implementation research. Prev Sci. 2024;25(Suppl 1):34-45.

Dearing JW, Kreuter MW. Designing for diffusion: how can we increase uptake of cancer communication innovations? Patient education and counseling. 2010;81:S100-S110.

Joshi M, Mecklai K, Rozenblum R, Samal L. Implementation approaches and barriers for rule-based and machine learning-based sepsis risk prediction tools: a qualitative study. JAMIA Open. 2022 Apr 18;5(2):ooac022.

Petersson L, Larsson I, Nygren JM, Nilsen P, Neher M, Reed JE, Tyskbo D, Svedberg P. Challenges to implementing artificial intelligence in healthcare: a qualitative interview study with healthcare leaders in Sweden. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022 Jul 1;22(1):850.

Marcial LH, Johnston DS, Shapiro MR, Jacobs SR, Blumenfeld B, Rojas Smith L. A qualitative framework-based evaluation of radiology clinical decision support initiatives: eliciting key factors to physician adoption in implementation. JAMIA Open. 2019 Feb 22;2(1):187-196.

Finkelstein J, Parvanova I, Xing Z, Truong T-T, Dunn A. Qualitative Assessment of Implementation of a Discharge Prediction Tool Using RE-AIM Framework. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2023 May 18;302:596-600.

Fereday J, Muir-Cochrane E. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. International journal of qualitative methods. 2006;5(1):80-92.

Kawamoto K, Finkelstein J, Del Fiol G. Implementing Machine Learning in the Electronic Health Record: Checklist of Essential Considerations. Mayo Clin Proc. 2023 Mar;98(3):366-369.

Watson J, Hutyra CA, Clancy SM, Chandiramani A, Bedoya A, Ilangovan K, Nderitu N, Poon EG. Overcoming barriers to the adoption and implementation of predictive modeling and machine learning in clinical care: what can we learn from US academic medical centers? JAMIA Open. 2020 Apr 10;3(2):167-172.

Funding

The project was in part funded by the grant R33HL143317 from the National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Joseph Finkelstein, Aileen Gabriel, Susanna Schmer, Tuyet-Trinh Truong, Andrew Dunn contributed equally. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Moderator Guide for Semi-Structured Qualitative Interviews

Respondent Characteristics:

-

1.

Primary unit(s) _____________________

-

2.

Role (Case manager, Social Worker, Nurse Manager, Unit Medical Director, Attending, Intern/Resident, Nurse Practitioner, Physician Assistant) _____________________________________________________________________

-

3.

How long have you worked at MSH? (0–1 year, 2–4 years, 5–10 years, > 10 years) _____________________________________________________________________

Script: State that 48DPT refers to the used during morning interdisciplinary rounds on Mount Sinai wards to predict whether patients will be ready for discharge within 48 h.

RE-AIM Dimension | Questions |

|---|---|

Reach (individual level) | For Unit-based Leadership (Case Manager, Social Worker, Nurse Manager, Unit Medical Director): On a typical weekday, How often does at least 1 member of the interdisciplinary team review the’s result (i.e., ready or not ready for discharge in 48 h)? Are there clinician groups for whom the is less likely to be used, such as from certain departments or teams? If yes, please describe Does use of the 48DPT vary by any patient factors, such as age, race, or disease? If yes, please describe For Clinicians (Attending, Intern/Resident, Nurse Practitioner, Physician Assistant): Are you aware that an electronic is in use, called the 48DPT, to help predict which patients may be able to be discharged within 48 h? On a typical weekday, how often does at least 1 member of the interdisciplinary team review the 48DPT’s result (i.e., ready or not ready for discharge in 48 h)? Does use of the 48DPT vary by any patient factors, such as age, race, or disease? If yes, please describe |

Efficacy / effectiveness (individual level) | How effective is 48DPT in identifying medical readiness for discharge? How often is discharge better predicted by 48DPT as compared to your judgment? Do you feel the 48DPT helps decrease LOS? If yes, please describe Do you feel the 48DPT helps initiate the processes needed for discharge (such as scheduling appointments), earlier? If yes, please describe Do you feel the 48DPT improves clinical care or patient outcomes? If yes, please describe Are you familiar with the “Discharge Today” field in Epic? If yes, do you feel the 48DPT and Discharge Today tool are redundant to each other, or do you feel each offers unique information? If you feel they are redundant, which of these 2 tools do you feel is more valuable? Why? |

Adoption (setting and/or organizational level) | For Case Managers, Social Workers, Nurse Managers: Is 48DPT used as intended? If not, tell us how the use varies How do clinicians react when you or another team member mentions that a discharge is predicted in 48 h? Does the reaction vary by the clinician’s role (NPs, PAs, Attendings, Hou staff)? If yes, please describe Does the response to the 48DPT, such as you or another team member stating that discharge is predicted in 48 h, vary according to specialty (Medicine, Fam Med, etc.), roles (attending, resident, NP, PA)? If yes, please describe Does the response to the 48DPT, such as you or another team member stating that discharge is predicted in 48 h, vary according to clinician’s time in practice? If yes, please describe For Clinicians (Attending, Intern/Resident, Nurse Practitioner, Physician Assistant): Is 48DPT used as intended? If not, tell us how the use varies Does the use of the 48DPT vary by unit? If yes, tell us how use varies |

Implementation (setting and/or organizational level) | Were you involved in developing the process for the use of the 48DPT? Do you feel that the members of the interdisciplinary team, such as CM, SW, Nurse Managers, and the clinicians, were involved adequately in developing the process for the use of the 48DPT? Do you feel 48DPT was integrated well into workflow? If not, how could integration have been improved? What training and support services are needed by 48DPT users? What level of computer skills are needed to use the 48DPT? |

Maintenance (individual and setting levels) | How much of a burden is using the 48DPT for you? Do you feel the benefits of the 48DPT outweigh the burden? What are the main barriers to use of the 48DPT? Have there been any efforts by leaders to receive feedback on the use of the 48DPT in order to make revisions? If yes, please describe Has the use of 48DPT changed over time? If yes, please describe Have any s helped you improve your use of the 48DPT (such as training sessions, individual feedback, unit-based metrics) If yes, please describe How could use of the 48DPT be improved? |

Appendix 2

Table 9

Appendix 3

Table 10

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Finkelstein, J., Gabriel, A., Schmer, S. et al. Identifying Facilitators and Barriers to Implementation of AI-Assisted Clinical Decision Support in an Electronic Health Record System. J Med Syst 48, 89 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10916-024-02104-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10916-024-02104-9