Abstract

This paper proposes a semantics of anaphora in attitude contexts within the framework of Discourse Representation Theory (DRT). The paper first focuses on intentional identity, a special kind of cross-attitudinal anaphora. Based on the DRT semantics of attitude reports summarized by Kamp et al. (in: D. Gabbay and F. Guenthner (Eds.), Handbook of philosophical logic, 2011), the author proposes a semantics of intentional identity that implements the following two ideas: (1) indefinites and pronouns appearing in attitude contexts introduce metadiscourse referents, which represent one’s mental files and record appearances of discourse referents in attitude contexts; and (2) what underlies the relevant kind of anaphoric links between indefinites and pronouns across attitude contexts is the coordination relation between mental files, which is represented by using metadiscourse referents. Next, the paper expands the semantics to cover de re anaphora, in which an anaphoric pronoun in an attitude context takes as its antecedent an expression appearing outside any attitude context.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

As Geach (1967) points out, cases of intentional identity, that is, cases of cross-attitudinal anaphora as illustrated in (1), where ‘she’ in the second sentence is anaphoric to ‘a witch’ in the first sentence, have a reading in which both attitude reports are true.

For example, (1) is true in the following situation (cf. Edelberg, 1986, p. 2):

The Hob–Nob case: In a village, because of an epidemic, many livestock are blighted and dead. The village newspaper spreads a rumor that a witch (exactly one witch) is threatening the village and trying to kill the livestock there. Both Hob and Nob read the newspaper and believe the rumor. Hob finds Bob’s mare getting sick and believes that a witch blighted it. Nob finds Cob’s sow dead and then believes that a witch killed it.

It is far from obvious how to semantically analyze such a reading of (1). First, it is often claimed that the anaphoric relation between ‘a witch’ and ‘she’ in the reading in question cannot be properly explained by analyzing ‘she’ as an individual variable bound by an existential quantifier corresponding to its antecedent ‘a witch’. Consider (2) (for simplicity, throughout this paper, I ignore the complexity in VPs in the embedded sentences of (1) and the like, and treat them as simple predicates):

(2a) entails that a witch exists,Footnote 1 but the reading of (1) in question does not (Geach, 1967, p. 628; Edelberg, 1986, pp. 2–3). (2b) entails that there exists some particular object about which Hob’s and Nob’s beliefs are, but the reading of (1) in question does not (Geach, 1967, pp. 628–629).Footnote 2

Neither the E-type analysis of pronouns appropriately explains the reading of (1) in question (Geach, 1967, p. 630; Edelberg, 1986, pp. 3–4). (1) can be true even when Nob believes nothing about Hob, Bob, and his mare, but (3) cannot.

Another attempt focuses on the fact that in the Hob–Nob case, Hob’s belief and Nob’s belief contain the same concept witch. For example, one may propose the following second-order analysis of the reading of (1) in question.

However, neither is this attempt correct, since for the reading of (1) in question to be true, it is not sufficient that the descriptive contents of Hob’s belief overlap the descriptive contents of Cob’s (Edelberg, 1986, pp. 8–9). For instance, suppose that no rumor concerning a witch crisis has spread in the village. When Hob finds that Bob’s mare got sick, the belief that a witch blighted it happens to come to his mind. Independently, Nob finds Cob’s sow dead and happens to believe that a witch killed it. In this case, even though their beliefs contain the same descriptive content, say, witch, (1) is not true—at least it sounds quite weird.Footnote 3

An important feature of Hob’s and Nob’s mental states that is responsible for the truth of the reading of (1) in question is missed in these attempts. According to Geach, (1967, p. 627), for the reading of (1) in question to be true, Hob’s belief and Nob’s belief should be “about the same thing” in the sense that their beliefs have, so to speak, “a common focus, whether or not there actually is something at that focus.” Asher uses the term ‘coordination’ to describe such a relation among beliefs and other kinds of mental states, claiming that it underlies the cross-attitudinal anaphora:

As Geach already intimated (Geach, 1967), such links [= anaphoric links exemplified by (1)] only make sense if the agents’ attitudes are coordinated together, whether by means of communication or some other mechanism, in such a way that the two agents can be said to have the “same” individual in mind. (Asher, 1987, p. 127, my emphasis)

As Asher points out, for some reasons—communication is a good reason, but not the unique reason—a mental state is coordinated with another mental state, in the sense that the former shares a ‘common focus’ with the latter. For example, suppose that John told Mary about a man whom he had met yesterday, and Mary believed what John said. In this case, even if John’s report was based on a daydream and he met no one yesterday, Mary’s belief is reasonably regarded as having the same focus as John’s mental state. In the Hob–Nob case, Hob’s belief and Nob’s belief are coordinated because their beliefs are based on the common source of information—the local newspaper. For another example, suppose that, while exploring a desert together, John and Mary see a mirage of an oasis and run toward the place where they see it. It is quite natural to describe this situation as the one where John’s perceptual experience (and his actions based on it) and Mary’s are directed toward a common focus. It is not difficult to find or think up other examples where two mental states are coordinated in the relevant sense. Somehow, a mental state can be coordinated with some other mental state without being about a particular existent object.Footnote 4\(^{,}\)Footnote 5 Geach and Asher point out that such coordination between mental states is crucial for the truth of the cases of cross-attitudinal anaphora such as (1).

The first aim of this paper is to explore a way to develop a semantics of cross-attitudinal anaphora in which coordination among mental states of a certain kind, that is, coordination among mental files, plays a central role.Footnote 6 I show that by incorporating the coordination relation between mental files into semantics as its primitive notion (like incorporating the accessibility relation between worlds into possible world semantics as its primitive notion), we can obtain a relatively simple and adequate semantics of cross-attitudinal anaphora of the kind in question. By extending DRT semantics for propositional attitude reports summarized by a useful survey of DRT (Kamp et al., 2011), I claim the following: indefinites and pronouns appearing in attitude contexts introduce metadiscourse referents, which represent one’s mental files and record appearances of discourse referents in attitude contexts; furthermore, assuming that coordination is a relation between mental files, cross-attitudinal anaphoric links between indefinites and pronouns are recorded by using metadiscourse referents and the coordination predicate, which represents the coordination relation between mental files.

The second aim of this paper is to show how metadiscourse referents are used to obtain a semantics of de re anaphora. In cases of intentional identity, an anaphoric pronoun appearing in an attitude context takes as its antecedent a term in another attitude context. An anaphoric pronoun appearing in an attitude context can take as its antecedent a term outside any attitude context as well, as illustrated in (5):

Let us call such anaphora de re anaphora. Kamp et al. (2011) explains how DRT analyses cases of de re anaphora using the notion of external anchoring, which links one’s mental representation with an external object. I show that it is easy to incorporate external anchoring into the DRT semantics with metadiscourse referents so that it properly explains de re anaphora.

This paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 reviews a DRT semantics of propositional attitude reports and cross-attitudinal anaphora based on Kamp et al. (2011). We will see that the semantics surveyed by Kamp et al. (2011) can explain, at best, intrapersonal cross-attitudinal anaphora (cases involving two attitude reports with the same reportee), but it does not properly explain interpersonal cross-attitudinal anaphora like the Hob–Nob sentences. We also confirm the importance of incorporating the coordination relation into the semantics of intentional identity. Section 3 proposes the basic account of the semantics for cross-attitudinal anaphora using DRT extended with metadiscourse referents and the coordination predicate. Section 4 discusses the relation between the coordination relation and the logic of cross-attitudinal anaphora. Section 5 expands the semantics to cover de re anaphora, in which an anaphoric pronoun in an attitude context takes the antecedent appearing outside any attitude context.

2 Kamp et al. (2011) on cross-attitudinal anaphora

Let us begin by reviewing the DRT semantics of attitude reports and cross-attitudinal anaphora summarized by Kamp et al. (2011), which is a useful survey of DRT.

At the beginning of the DRT history, Kamp expressed the view that DRSs are mental representations that a hearer of a discourse constructs as her interpretation of the discourse (Kamp, 1981). In particular, discourse referents are taken as entity representations, that is, mental representations of entities that hearers have (Kamp et al., 2011, pp. 326–327). Even though the idea of DRS as mental representation is not a core DRT doctrine, it has motivated DRT semantics for propositional attitude reports that describes mental states of reportees of attitude reports by using DRSs.

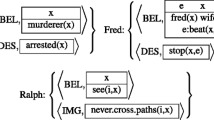

A mental state (type) is described as a pair of its attitudinal mode such as belief, desire, or hope and a DRS that specifies the content of the state. For example, a belief that a delegate arrived is described as (6), where BEL is the indicator of the attitudinal mode of believe.

An attitude ascription ascribes one or more mental states to a subject. For example, one may ascribe to Mary a belief that a delegate arrived and a hope that the same delegate registered. The following DRS condition corresponds to this attitude ascription (I use ‘HOPE’ as the mode indicator for hope).

\(Att(s, \{ \langle \varPhi , K \rangle , \dots \} )\) is an attitude ascription condition that means that a subject s has a mental state whose mode—belief, desire, intention, hope, and so on—is \(\varPhi \) and whose content is specified by DRS K. The set of ordered pairs of an attitude mode and a DRS in an attitude ascription condition is called attitude description set (ADS). Note that the exposition in this section omits the complexity concerning the notion of external anchor (Kamp et al., 2011, pp. 332–343). This is just for simplicity: external anchors play no role in explaining cases of intentional identity. However, we need external anchors to treat cases of de re ascription. We incorporate external anchors into the account—although in a slightly different manner than Kamp et al. (2011)—in Sect. 5, where we discuss de re ascriptions.

We now consider a case where Mary holds a belief that a delegate arrived and a hope that the same delegate registered. According to terminology of Kamp et al. (2011, pp. 331–332, 338), these two mental states are internal-referentially connected: they are taken by her as being about the same object, at least, internally or psychologically. As Kamp et al. (2011) emphasize, internal/psychological referential connectedness between mental states of a subject neither entails nor presupposes that these mental states are actually about the same external object. So, internal referential connectedness between two mental states need to be represented in DRSs without appealing to their common external object. In Kamp et al. (2011, p. 331), the internal referential connectedness between mental states “is captured by the occurrences of the same discourse referent” in each of DRSs used to describe them. More precisely, two DRSs, \(K_1\) and \(K_2\), are internally referentially connected with respect to a discourse referent x if and only if x appears both in \(Con_{K_1}\) and \(Con_{K_2}\) and x appears in at most one of \(U_{K_1}\) and \(U_{K_2}\)—the occurrences of x must be free at least in \(Con_{K_1}\) or \(Con_{K_2}\). In (7), the discourse referent x appears in the DRS paired with BEL and in the DRS paired with HOPE.

According to Kamp et al. (2011), the intrapersonal cross-attitudinal anaphora like (8a) is supported by the internal referential connectedness of mental states of a subject.

(8b) is the DRS for (8a). The anaphoric link between the indefinite DP ‘a man’ in its first sentence, and the anaphoric pronoun ‘he’ in its second sentence is recorded by the identity ‘\(u=x\)’ in the condition of the DRS in the second attitude ascription. Here, it is crucial that the discourse referent x is shared by the DRS specifying the content of Phoebe’s belief and the DRS specifying the content of her hope. This fact represents the internal/psychological referential connection between her belief and her hope.

Kamp et al. (2011) hold that the internal/psychological referential connectedness among mental states, which is supposed to be captured by their sharing of the same discourse referent, is intrapersonal. Now, (1) is a case of interpersonal cross-attitudinal anaphora—anaphora between an indefinite and a pronoun in the embedded sentences of two attitude reports whose reportees are different. As the same mental representation of an entity can appear only in the mental states of the same subject, the anaphoric link must be supported by something different from the internal/psychological referential connectedness described above.

Kamp et al. (2011) claim that in cases of interpersonal cross-attitudinal anaphora such as (1), what supports the anaphoric link in question is that two subjects have some mental state with the same content:

Clearly, the anaphoric relation between [‘a witch’] in the first and [‘she’] in the second sentence of [(1)] makes no sense unless there is some mental content which Nob shares with Hob. What is needed, therefore, is an accommodation according to which some of what the first sentence attributes to [Hob] is also part of the beliefs of [Nob]. (Kamp et al., 2011, p. 383)

In the Hob–Nob case, both Hob and Nob believe that there is a witch, and this is supposed to support the anaphoric link between ‘a witch’ and ‘she’ in (1). Based on these considerations, Kamp et al. (2011) propose an analysis of interpersonal cross-attitudinal anaphora illustrated by (9) for (1).

In (9), the second attitude ascription to Nob is an accommodation that ensures that Nob has a belief whose content is the same as the one of Hob’s beliefs.

However, as we have seen in Sect. 1, sharing the same descriptive content in this sense is not sufficient for interpersonal cross-attitudinal anaphora. In the passage quoted in Sect. 1, Asher claims that the anaphoric links across attitude contexts of the kind in question need to be supported by coordination between mental states, which can be interpersonal. Furthermore, (9) is not sensitive to this information of coordination among the agent’s attitudes because there are no DRS conditions that record the link between x and u. This insensitivity is witnessed by the fact that (9) is basically the same as a DR-theoretic translation of (10), which can be true even when Hob’s belief and Nob’s belief are not coordinated.

Because of this insensitivity, (9) fails to properly represent the anaphoric link between ‘a witch’ in the first sentence and ‘she’ in the second sentence of (1).

The question is, then, how to represent coordination between mental states in DRSs. The DRT semantics summarized by Kamp et al. (2011) does not offer a sufficient machinery to describe the coordination relation supporting cross-attitudinal anaphora. In (9), the discourse referent x can be regarded as representing Hob’s mental representation of a witch, and \(x'\) (and u) as representing Nob’s representation of a witch. Given this, it seems natural to represent coordination between Hob’s belief and Nob’s belief by using a relation between x and \(x'\). However, within the framework of DRT summarized in the previous section, it is difficult to record information about coordination between attitudes by using these discourse referents.

To make this point clear, let us introduce the notions of matrix DRS and content DRS: a matrix DRS is a DRS containing some attitude ascription condition as its DRS condition, and a content DRS is a DRS that appears in an attitude ascription condition and represents the content of some mental state. In the DRT semantics summarized by Kamp et al. (2011), information about linguistic anaphora between an indefinite and a pronoun is recorded by the identity statement between the discourse referents they introduce. Within this framework, there are only two ways to record anaphoric links. The first one is to put the identity statement in question in a content DRS, and the second one is to put it in a matrix DRS. Unfortunately, both ways cannot properly treat cases of interpersonal cross-attitudinal anaphora.

According to the first option, the condition \(x=x'\) appears in the content DRS that specifies the content of Hob’s belief or one that specifies the content of Nob’s belief. If the former was the case, then Nob’s mental representation would appear in Hob’s mental state, but this is impossible. What can appear in Hob’s mental state is a representation of Nob’s mental representation (and this is useless in the present context because the truth of the reading of (1) in question does not require that Hob believe anything about Nob). The same problem would arise if the latter was the case. Moreover, the coordination relation is a relation that can hold without being represented by any subjects. As we have seen, some objective facts that two mental states have a common informational source and so on are crucial for them to be coordinated. Taking this into consideration, the coordination relation between mental states should be represented outside content DRSs. However, it is also problematic to put the identity \(x = x'\) in a matrix DRS. First of all, if we put \(x=x'\) in the matrix DRS of (9), then x and \(x'\) are unbound because they do not appear in the universe of the matrix DRS. This makes the DRS not being proper and its truth in a model undefined (see Kamp et al., 2011, pp. 146–149). To avoid this, one may add x and \(x'\) to the universe of the matrix DRS. But this does not work. As they appear in the universe of the matrix DRS rather than the universe of the content DRSs, they represent individual objects. If so, \(x = x'\) represent the identity of individual objects, not mental representations, and thus \(x = x'\) fails to do the expected job to describe the coordination relation between mental states.

How to avoid this predicament? The first step would be

Second, because two mental states/representations need not be identical to be coordinated (indeed, in many cases, they are different), the identity symbol is not suitable for representing the coordination relation outside content DRSs. A straightforward way to accommodate this would be

In the next section, I propose a way to furnish the DRT framework by Kamp et al. (2011) with such a machinery and condition. Concerning (A), I introduce metadiscourse referents, a new kind of discourse referents for representing one’s mental states (more properly, mental files, in the terminology of the present paper), rather than external object, which appear in the universe of matrix DRSs. Concerning (B), I introduce the coordination predicate to represent the coordination relation between mental states. The coordination predicate, together with metadiscourse referents, enables us to represent the coordination relation in a quite straightforward manner in matrix DRSs (i.e., outside the scope of one’s attitudes), and we can use it to record anaphoric links across attitude contexts.

3 DRT with metadiscourse referents and the coordination predicate: basic account

In Sect. 3.1, I extend the DRT language so that anaphoric links are recorded by metadiscourse referents and the coordination predicate in matrix DRSs, and give an informal exposition of what extended DRSs means by appealing to the notion of mental files. It is shown that these new elements can be straightforwardly combined with the presuppositional account of pronouns using the preliminary representation (see Kamp et al., 2011). In Sect. 3.2, I define a model theoretic semantics for DRSs containing metadiscourse referents and the coordination predicate.

The account developed in this section does not treat de re ascriptions. Specifically, it says nothing about de re anaphora, where an anaphoric pronoun in an attitude context takes a term that does not appear in any attitude context as its antecedent. How to extend the theory to cover de re cases is discussed in Sect. 5.

It should be noted that, as the first explanation of a new account, the discussion in this paper continues under substantial simplifications and restrictions. We mainly focus on first-order belief reports. In addition to belief reports, we mention hope reports to illustrate how the new account can deal with different kinds of attitudes and how it differs from Recanati’s (2012) account of mental files. The semantics of higher-order attitude reports that embed other attitude reports is not discussed in this paper. To generalize the account in this paper to fully treat attitude verbs in general and embedding of attitude reports is a topic left for further research.

3.1 Syntax and an intuitive exposition of how to interpret DRSs with metadiscourse referents and the coordination predicate

Let us consider an extensional DRT language, for example, one defined by Kamp et al. (2011), and add attitude ascription conditions of the form Att(r, ADS) to it, where ADSs are restricted in the following way. As attitudinal modes, we consider only BEL and HOPE, and as content DRSs, we consider only DRSs in which no attitude ascription condition appears. In what follows, we show how to further extend the language with metadiscourse referents and the coordination predicate.

Suppose that r is a discourse referent. Then, [r] is a metadiscourse referent of r—metadiscourse referents are named so because they are discourse referents of discourse referents. Metadiscourse referents are used for two purposes. First, they are used to register which discourse referents appear in content DRSs: whenever a discourse referent r appears in the universe of a content DRS in a matrix DRS, its metadiscourse referent [r] is introduced in the universe of the matrix DRS. Second, they are used to represent coordination among mental files and to record anaphoric link across attitude contexts. Let me explain these points by using (1):

First, whenever a discourse referent appears in the universe of a content DRS, its appearance is registered by introducing its metadiscourse referent into the universe of the matrix DRS whose condition contains the content DRS. The introduction rule of metadiscourse referents is thus as follows:

For example, when the first sentence of (1) updates the empty DRS, we have the following DRS.

x in the content DRS is introduced by the indefinite DP ‘a witch’ in the embedded sentence. [x] in the universe of the matrix DRS is the metadiscourse referent of x that registers an appearance of the discourse referent x in the universe of the content DRS.

What do metadiscourse referents and DRSs containing them represent? Even though there could be different ways of answering this question, I present here an intuitive answer to it by appealing to the notion of mental file.Footnote 7 Informally speaking, in (12), [x] represents a mental file whose possessor and contents are specified in the attitude ascription condition in (12). More specifically, (12) is true iff there is a mental file of Hob that contains the information of being a witch and blighted Bob’s mare with the attitudinal mode of belief. Note that this is nothing more than an intuitive and informal understanding of what metadiscourse referents and DRSs containing them represent. The precise model theoretic interpretation of DRSs containing metadiscourse referents is defined in the next section. However, it would still be useful to explore this informal picture in more detail.

It is common to assume mental files to explain object-oriented information processing by cognitive systems (see Recanati, 2012). Philosophers, linguists, and cognitive scientists have used a mental file as a psychological storage of information so that pieces of information in it are taken as being about the same object by an individual who uses it. If two or more pieces of information are taken by a subject as being about the same object, then, it is said that they are stored in the same mental file. For example, suppose that by seeing an apple in front of her, Mary thinks that it is red and round. In this case, she has a perceptual mental file for the apple that contains information of being red and information of being round. If, as Kamp has suggested, DRSs are mental representations hearers construct during interpreting discourses, then, for a DRS \(\langle U, Con \rangle \), any pair of a discourse referent in U and its conditions in Con can be seen as a temporal mental file constructed and used to interpret the discourse in question by its hearer.Footnote 8 These files are temporal ones in the sense that they are sustained only during perceiving something or interpreting of discourses. However, some files are sustained for a long period, which would be in subjects’ long-term memories. For example, I take many pieces of information as being about the Empire State Building (being located in Manhattan, having elevators, etc.), and this means that I have a mental file for it containing these pieces of information. Many mental files are properly connected to a particular object, but this is not necessarily the case. Some files fail to have any particular referent (e.g., the Vulcan file Le Verrier had); some files contain pieces of information whose sources are different objects (e.g., the Madagascar file Marco Polo had). It is a common assumption that mental files are connected to understanding of referential terms such as proper names, indexicals, demonstratives, and definite descriptions. However, this needs not be the case, given that the DRS \(\langle \{ x\} , \{ delegate'(x) , arrive'(x) \} \rangle \) is a mental file that a hearer constructs when she interprets the sentence ‘a delegate arrived’ (cf. Cumming, 2014b on descriptive files).

Mental files are something functionally characterized by their role in object-oriented information processing by cognitive system. A mental file is thus a psychological entity in mind in the sense that a mental file is a part of one’s cognitive system. Simultaneously, a mental file is something in the real world, to the extent that our cognitive systems are parts of our reality. Mental states such as beliefs or hopes are usually regarded as parts of the real world in this sense. So are mental files.

Now I propose that an attitude ascription condition Att(s, ADS) can be used to represent a mental file(s), as a part(s) of the real world, of the agent s. More precisely, each discourse referent r in the universe of a content DRS in an attitude ascription condition represents a mental file whose contents are partially described by the conditions of r specified in the content DRS. For example, x of \(\langle \{ x\} , \{ delegate'(x) , arrive'(x) \} \rangle \) appearing inside Att(s, ADS) represents a mental file of the subject s containing information of being a delegate and arrived (and probably more). Metadiscourse referents are the devices for representing such mental files outside attitude ascription conditions. A metadiscourse referent [x] is in the universe of a matrix DRS represents a mental file represented by x in a content DRS, that is, one whose contents are (partially) specified by the content DRS with the discourse referent x, and whose subject is specified by the attitude ascription condition containing the content DRS.Footnote 9

Another element in an attitude ascription condition are the modes of mental states. How are they related to the idea that a discourse referent in a content DRS and a metadiscourse referent in a matrix DRS represent a mental file? To answer this question, I propose that each piece of information in a mental file is accompanied by some attitudinal mode. In (12), the content DRS is paired with the mode of belief, which can be interpreted as meaning that in the mental file represented by x in the content DRS, the information of being a delegate and that of arrived are associated with the mode of belief. It may be the case—indeed, it is often the case—that a mental file contains pieces of information having different attitudinal modes. For example, suppose that a subject s believes that a delegate arrived and hopes that she registered. In this case, she has a mental file containing the information associated with the mode of belief and the one associated with the mode of hope. [x] in the following DRS is used to represent such a mental file of s:

It is worthwhile mentioning that the semantics presented in the next section ensures that the metadiscourse referent [x] and two occurrences of x in the universes of the different content DRSs of (13) represent the same mental file that the subject s has.

Assuming that each piece of information in a mental file is associated with an attitude mode, the present account allows a mental file to contain different pieces of information associated with different attitude modes. This is a crucial difference between the present account and Recanati’s (2012) account of mental files, according to which a mental file contains (Mentalese) predicates without any label for attitude modes. As Maier (2016, p. 489) has already pointed out, “[t]he crucial difference between Kampian ADSs and Recanati’s mental files is that an ADS represents the different attitudes (belief, desire, imagination) separately, as distinct DRS boxes that all [share the same discourse referents].”Footnote 10

Comparing Kampian DRT account of mental states and Recanati’s account of mental files, Maier (2016) proposes that in Kampian DRT account of mental states, (internal) anchors play the role of object-oriented information processing, by which the present account characterizes the notion of mental files. According to Maier (2016, p. 489), “anchors are, as Ninan puts it, ‘mental representations whose primary function is to carry information about objects.’ ” The content of an anchor (as a kind of mental file) is specified by ADSs that share the same discourse referent with the anchor (that is, ones that have internal referential connectedness with the anchor). According to this framework, for example, the mental file represented by (13) is represented as (14):

where \(\phi \) specifies the way the subject s (thinks that s) is acquainted with the object x. A crucial difference between Maier’s account and the present one is as follows: by replacing anchors with metadiscourse referents, the present account provides machinery to represent mental files outside ADSs and attitude ascription conditions, which is essential for representing the interpersonal coordination relation between mental states of different subjects.

Let us move to the second purpose of using metadiscourse representations: to represent the coordination relation between mental files and to register anaphoric link across attitude contexts. The basic ideas go as follows. First, as usual discourse referents are, metadiscourse referents in the universe of a DRS as a context of interpretation serve as possible antecedents for anaphoric pronouns in subsequent sentences. The following two factors determine which metadiscourse referent is available as a possible antecedent of a subsequent anaphoric pronoun in an attitude context: accessibility and the presuppositions triggered by anaphoric pronouns. So far resolution of cross-attitudinal anaphora proceeds in a quite standard manner, except that now it involves metadiscourse referents. Another new element coming into the account is the coordination predicate: the cross-attitudinal anaphora like in (1) is recorded not by using the identity symbol and discourse referents, but by using the coordination predicate and metadiscourse referents. Let us see how these ideas work.

(17) is the preliminary representation corresponding to the second sentence of (1).Footnote 11 (For simplicity, I ignore the presupposition triggered by the proper name ‘Nob’.)

u in the context DRS of (17) is a discourse referent introduced by ‘she’ in the embedded sentence of the second sentence of (1). We assume that the presuppositions triggered by ‘she’ in the embedded sentence are adjoined to the content DRS so that they constitute a preliminary representation, and that the preliminary representation appears as an element of the attitude ascription condition in question (see Kamp et al., 2011, p. 362).Footnote 13 Again, [u] registers the appearance of the discourse referent u in the universe of the content DRS of (18) and represents a mental file the agent of the attitude in question—in this case, Nob—has.

In the standard DRT framework, finding a suitable antecedent for a pronoun amounts to finding a discourse referent such that (i) it is accessible from the discourse referent introduced by the pronoun in question, and (ii) it satisfies (maybe by accommodation) the presupposition(s) triggered by the pronoun, whose content is specified in the presuppositional part of the preliminary representation in question.Footnote 14 To deal with cross-attitudinal anaphora, let us expand this basic strategy of anaphora resolution in the following way. A way to find a suitable antecedent for a pronoun in the embedded sentence of an attitude reportFootnote 15 is to find a metadiscourse referent \([r']\) such that

According to (18b), when anaphora is resolved in this manner, the presupposition \(\phi \) triggered by an anaphoric pronoun is embedded in an attitude context in the following sense: an attitude report (a belief report or a hope report, in the present account) whose complement contains the anaphoric pronoun as a whole presupposes that in the context of interpretation, there is a mental file where the information \(\phi \) is associated with some mode (belief or hope, in the present account).Footnote 16 Note that such mental file needs not be a file that the reportee in question has. As we will see soon, in the Hob–Nob sentences, the presupposition triggered by ‘she’ in its second sentence whose subject is ‘Nob’ is satisfied by its context of interpretation because in the context, there is a mental file of Hob that contains the information specified by the presupposition. In this sense, embedding of the kind in question is subject-free.

In (1), (12) is the context of interpreting (17). To find a suitable antecedent for ‘she’ in (1) in accordance with (18) is to find a metadiscourse referent that is accessible from [u] and satisfies the presupposition triggered by ‘she’. [x] in (12) is such a metadiscourse referent because it is accessible from [u], and [x] records the appearance of x in the content DRS associated with the mode of belief, which contains the condition \(witch'(x)\) (assuming that being a witch entails being a female). The presupposition triggered by ‘she’ in the second sentence of (1) is thus properly resolved by taking [x] in (12) as the antecedent of [u] in (17).

Now, to record presupposition resolution of this kind, let us introduce the coordination predicate > for metadiscourse referents, assuming that the coordination relation underlying the cross-attitudinal anaphoric linkage in question is a relation between mental files. \([r] > [r']\) indicates that the mental file represented by [r] is coordinated with the one represented by \([r']\). If [r] takes \([r']\) as its antecedent, this information is recorded as \([r] > [r']\) in the condition of the matrix DRS. In the present case, [x] is the antecedent of [u], and therefore this information is recorded as \([u] > [x]\) in the condition of the matrix DRS of (17). Thus, we obtain (19) as the result of the presupposition resolution of (17).

Finally, merging this DRS with (12) results in the following DRS, which is a DRS translation of (1).Footnote 17

Informally speaking, (20), and thus the reading of (1) in question, is true iff (i) there are two subjects, Nob and Hob; (ii) there are two mental files X (represented by [x]) and U (represented by [u]) such that X is Hob’s file containing the information of being a witch and the one of blighted Bob’s mare associated with the mode of belief, and U is Nob’s file containing the information of killed Cob’s sow associated with the mode of belief; and (iii) Nob’s mental file U is coordinated with Hob’s mental file X.Footnote 18\(^,\)Footnote 19

In the next section, we define a model-theoretic semantics for DRSs with metadiscourse referents and the coordination predicate that implements this informal exposition of the truth condition.

3.2 Semantics

Let us begin by pointing out three distinctive ideas behind the semantics. First, the present semantics takes at face value the idea that metadiscourse referents in matrix DRSs and discourse referents in content DRSs represent mental files. As we have seen, mental files are something in the reality. These kinds of discourse referents are about mental files as something in the reality. The semantics directly reflects this idea by incorporating into the model a set of mental files as one of its primitive components. Second, a mental file per se is a kind of representation too: it has contents. It contains different pieces of information with different attitude modes, which are supposed to be about an object. To explain the representational contents of mental files, the semantics introduces the notion of m-information states. In a nutshell, metadiscourse referents in matrix DRSs and discourse referents in content DRSs are representations of representations of the world, and mental files are not only what represents, but also what is represented. Finally, coordination is a relation between mental files. By using a set of mental files in a model, the semantics straightforwardly models coordination as a relation on the set of mental files.

A model M is any seven-tuple \(\langle D, A, W, MF, C, \rhd , V \rangle \) that satisfies the following conditions.

D is a set of individual objects.

A is a set of agents (bearers of propositional attitudes), which is a subset of D.

W is a set of worlds. For simplicity, we assume that the domain is constant across worlds.

MF is a set taken as a set of mental files. For each w, \(MF _w\) is the set of mental files that agents have in w. MF must be disjoint from the set of discourse referents constituting the basic vocabulary of DRSs.Footnote 20

C is a function that specifies the contents of agents’ mental files. More precisely, for any world w and agent a, C assigns attitude-relative contents to all of a’s mental files in w. To explain this, first we need to introduce the notion of information state (Kamp et al., 2011, pp. 157–158). Standardly, an intensional semantics for a language L assigns to each formula of L a set of possible worlds, that is, the set of all possible worlds where the formula is true. Instead of a set of possible worlds, intensional semantics for DRSs assigns to each proper DRS an information state. An information state assigned to a proper DRS K relative to an intensional model \(M = \langle D, W, V \rangle \), in symbols \([\![K]\!] ^s _M\), is a set of pairs of a possible world w and an embedding function \(f : U_K \rightarrow D\) such that every condition in \(Con_K\) is verified by f in w with respect to M.

All embedding functions appearing in \([\![K]\!] ^s _M\) have the same domain, that is, \(U_K\). Therefore, the information state assigned to K registers information about the universe of K, and thus about candidates of antecedents of anaphoric pronouns.

Now let us introduce the notion of m-information state by modifying the definition of information states. An m-information state is a set of pairs of a world and a function that maps a mental file to a member of the domain D. An m-information state serves as a formal model of what information a mental file contains, in a similar way that a function from sentences to sets of worlds serves as a formal model of which proposition a sentence expresses. Suppose that I is an m-information state such that m is a member of the common domain of all functions in I and, for any \(\langle w, i \rangle \), \(\langle w, i \rangle \) in I only if i(m) is a delegate in the world w. According to I, m contains the information of being a delegate. (Note that this is a rough characterization to give an initial idea of how m-information states work. In particular, for simplicity, here I ignore the fact that a mental file contains a piece of information only relative to a world and a mode. The precise characterization is stated in the next paragraph.) The domain of the functions in an m-information state needs not to be a singleton. If all functions in an m-information state I have \(\{ m_1, m_2, \dots , m_n \}\) as their common domain, then I serves as a formal model of which contents each of \(m_1\), \(m_2\), \(\dots \), and \(m_n\) has.Footnote 21

Of course, this is not the whole story. Each piece of information in a mental file must be associated with an attitude mode, and the content of a mental file a subject has will be different in different worlds. C treats these features. The range of C is the set of m-information states. C assigns an m-information state to each ordered triple of an agent \(a \in A\), a world w, and an attitudinal mode \(\varPhi \). For example, consider C(John, w, BEL). First, C(John, w, BEL) specifies the totality of what John believes in w: \(w'\) is in a member of C(John, w, BEL) iff \(w'\) is a world that realizes everything John believes in w. Moreover, C(John, w, BEL) specifies which mental file of John contains which information with the mode of belief in w in the following sense: C is a function according to which, in w, John has a mental file m that contains the information of being a delegate with the mode of belief iff it is the case that, for any \(\langle w', i \rangle \), \(\langle w', i \rangle \in C(John, w, BEL)\) only if i(m) is a delegate in \(w'\). In the same way, C(John, w, HOPE) specifies which mental file of John contains which information with the mode of hope in w in the following sense: C is a function according to which, in w, John has a mental file m that contains the information of registered with the mode of hope iff it holds that for any \(\langle w', i \rangle \), \(\langle w', i \rangle \in C(John, w, HOPE)\) only if i(m) registered in \(w'\). Generally speaking, C is a function according to which a subject a has a mental file m that contains the information of P associated with the mode of \(\varPhi \) in w iff it holds that, for any \(\langle w', i \rangle \), \(\langle w', i \rangle \in C(a, w, \varPhi )\) only if i(m) satisfies P in \(w'\). It is required that all functions in the members of the m-information state \(C(a, w, \varPhi )\) share the same domain, which is a subset of \(MF_w\). Let us call this domain the base of \(C(a, w, \varPhi )\).Footnote 22 We also require that the base of C(a, w, BEL) is identical to the base of C(a, w, HOPE). (Once the language is extended to contain attitudinal modes other than BEL and HOPE, we require that for any attitudinal modes \(\varPhi \) and \(\varPsi \), the base of \(C(a, w, \varPhi )\) is identical to the base of \(C(a, w, \varPsi )\).) This shared base is the set of all mental files the agent a has in w. Let us call it \(MF_{w} ^a\). Finally, it is required that for any agents a and b, \(MF_{w} ^a\) be disjoint from \(MF_{w} ^b\). This reflects the intuition that no two agents can share the same mental file.

\(\rhd : W \rightarrow \mathcal {P}(MF \times MF)\) determines coordination among mental files in each world. For each world w, \(\rhd _w\) is a binary relation on \(MF_w\), where ‘\(m \rhd _w m'\)’ means that a mental file m is coordinated with a mental file \(m'\) in w. When m and \(m'\) are mental files of the same agents, that \(m \rhd _w m'\) is a case of intrapersonal coordination, and when m and \(m'\) are mental files of different agents, that \(m \rhd _w m'\) is a case of interpersonal coordination. We discuss whether any restriction should be placed on the coordination relation in the next section.

V is an interpretation function assigning a model theoretic meaning to each non-logical vocabulary, which is defined as usual.

Let us move to the definition of verification. Usually, an embedding function is a function from the universe of a DRS to the domain of the model. Now the universe of a DRS may contain not only discourse referents but also metadiscourse referents. As discussed, a metadiscourse referent represents one’s mental file. More precisely, a metadiscourse referent [x] represents a mental file whose possessor and contents are specified in the attitude ascription condition whose content DRS contains a discourse referent x in its universe. The semantics implements this idea by assigning a mental file to a metadiscourse referent in two steps. First, it is required that any embedding function assign a discourse referent x to each metadiscourse referent [x] in the universe of the relevant DRS (so the range of an embedding function is the union of D and the set of discourse referents). In addition, we need functions that map each discourse referent appearing in the universe of a content DRS to a member of MF. Let us call such a function an m-embedding function. When g is an embedding function and h is an m-embedding function, h(g([x])) is the mental file that [x] represents according to g and h.

Verification of the coordination predicate and attitude ascription conditions depends not only on embedding functions but also m-embedding functions. Verification of the coordination predicates is straightforwardly defined. Suppose that g is an embedding function and h is an m-embedding function, then,

The basic idea of verification of attitude ascription conditions is that an attitude attribution condition \(Att(x, \{ \langle \varPhi , K \rangle \} )\) is verified in w by an embedding function g and an m-embedding function h iff the m-information state that specifies the totality of what the subject g(x) \(\varPhi \)s in w, that is, \(C(g(x), w, \varPhi )\) “carries at least as much information as” the information state assigned to K, that is, \([\![ K ]\!]^s _M\) under h.Footnote 23 For this condition to hold, it is not sufficient that any world that realizes everything the subject g(x) \(\varPhi \)s in w is also a world in which K is satisfied: in addition, it must be the case that any discourse referent in K is associated with a mental file of g(x) in an appropriate manner—in a way that the conditions of a discourse referent r in K at least partially describe the pieces of information in the mental file associated with r—via h. Modifying the definition by Kamp et al. (2011) of the carrying-at-least-as-much-information-as relation between two information states, let us formally define the carrying-at-least-as-much-information-as relation between the m-information state \(C(d, w, \varPhi )\) and the information state \([\![ K ]\!]^s _M\) under an m-embedding function h as follows:

The definition of (25) leads us immediately to the following verification condition of attitude ascription conditions: suppose that g is an embedding function and h is an m-embedding function. Then,

Note that whenever an attitude ascription condition Att(x, ADS) appears in a DRS \(K'\) as its DRS condition, for any discourse referent r in the universe of K in the ASD, the corresponding metadiscourse referent [r] appears in the universe of \(K'\) and \(g([r]) = r\).

Figure 1 illustrates how the functions in (25) and (26) are intended to work in verification.

How the functions in the definition (25) are intended to work in verification. The composite function \(h\circ g\) determines the representation relation between metadiscourse referents and mental files. In Fig. 1, [r] in the matrix DRS represents the mental file m. The m-embedding function h determines the representation relation between discourse referents and mental files. In Fig. 1, r represents m. The content DRS is assigned the information state as defined in (23). Each f in the information state assigned to the content DRS maps r to an object d. Finally, i is in a member \(\langle w', i \rangle \) of C(g(x), w, BEL), which specifies which mental file of the agent g(x) contains which information associated with the mode belief. That i maps m to an object d means that d satisfies the information associated with the mode of belief in m in \(w'\). For verification, i(m) must satisfy the information attributed to f(r) by the content DRS: formally, for any such i(m), there is an f(r) such that i(m) = f(r)

For other types of conditions, \(g, h \models _{M , w} \) is defined as \(g \models _{M, w}\).

Finally, truth condition and entailment are defined as follows: a DRS K is true with respect to the model M in w iff there are an embedding function g and an m-embedding function h that verify all conditions in \(Con_K\) with respect to M in w. Entailment is defined by truth-preservation in all models in the usual manner.

The next section discusses the relation between the coordination relation and the logic of cross-attitudinal anaphora.

4 The structure of the coordination relation and the logic of cross-attitudinal anaphora

4.1 Two perspectives for investigating the coordination relation

The semantics defined in the previous section has no restriction on the coordination relation \(\rhd \). Should any restriction be placed on the coordination relation? There are two perspectives for answering this question. The first perspective is the logic of cross-attitudinal anaphora. The semantics defined in the previous section is weak. For example, the semantics invalidates all of the following inferences.

The semantics is like the modal logic K. K has no restriction on the accessibility relation. Restricting the accessibility relation in different ways leads to different modal logics. Similarly, the semantics defined in the previous section has no restriction on the coordination relation, and restricting the coordination relation in different ways leads to different logics of cross-attitudinal anaphora. The question of the coordination relation above is thus inseparable from the investigation of the correct logic of cross-attitudinal anaphora. We should restrict the coordination relation in the way the resulting semantics leads to the correct logic of cross-attitudinal anaphora.

Let us call this first perspective the inferential perspective. The inferential perspective gives us an indirect route to investigating the coordination relation via the logic of cross-attitudinal anaphora. However, one may directly investigate what the coordination relation should be. Let us call this second perspective the conceptual perspective.

Let us begin the investigation from the conceptual perspective. In the Introduction section, following Geach and Asher, I gave the following rough characterization of the notion of coordination: a mental state X is coordinated with a mental state Y in the sense that X shares a common focus with Y. For a mental file X to be coordinated with a mental file Y is thus for X to share a common focus with Y. I do not present this as the definition of the coordination relation. However, this, together with the examples we have seen so far, gives us an intuitive understanding of the relation. In particular, this rough characterization of the coordination relation as sharing a common focus induces the following natural presumptions. The coordination relation is reflexive: given the main role of mental files is to explain object-oriented information processing, and thus, any mental file is supposed to be directed toward an object, any mental file has a focus and shares the focus with itself. Therefore, any mental file is coordinated with itself. The coordination relation is symmetric: if X shares a common focus with Y, then Y shares the focus with X. Therefore, if X is coordinated with Y, then Y is coordinated with X. The coordination relation is not transitive: a focus that X and Y share and a focus that Y and Z share may be different, and X and Z may not share any focus. If this is the case, X is coordinated with Y and Y is coordinated with Z, but X is not coordinated with Z. In sum, characterizing coordination as sharing a common focus suggests the following structural properties of the coordination relation:

In what follows, we examine how this hypothesis obtained from the conceptual perspective can fit some data obtained from the inferential perspective, focusing on (27).

4.2 Reflexivity and intrapersonal cross-attitudinal anaphora

First, let us consider (27a), repeated below.

The inference from (29a) to (29b) instantiates this inferential pattern.

The inferences of the form (27a) are apparently valid when the presupposition of a personal pronoun is appropriately accommodated.

It is easily confirmed that the reflexivity of the coordination relation ensures the validity in question. First, (29a) is translated as (30):

Second, (29b) is a case of intrapersonal cross-attitudinal anaphora, which consists of two sentences with the same reportee. Even though the main example discussed so far is the Hob–Nob sentences, which is a case of interpersonal cross-attitudinal anaphora, the semantic machinery proposed in Sect. 3 can deal with not only interpersonal cross-attitudinal anaphora but also intrapersonal cases. (29b) is translated as (31) (for simplicity, I ignore the possible complexity induced by two occurrences of ‘Phoebe’).

(30) is true if Phoebe has a mental file that contains the information of being a person, the one of arrived, and the one of registered, associated with the mode of belief. Call this mental file of Phoebe X. Suppose that the information of being a female is property added to X as presupposition accommodation. Now, given the reflexivity of the coordination relation, X is coordinated with itself. Therefore, (31) is true under any embedding that assigns X to [x] and [u]. This way of reasoning validates any inferences of the form (27a).Footnote 24

Next, consider (27b), repeated below.Footnote 25

This form of inference appears to be valid. If this is indeed valid, the reason would be that if two mental files that a single subject has are coordinated, then the pieces of information in those files with the mode of belief must be able to be put together in a single file. Neither the reflexivity nor the symmetricity of the coordination relation ensures that this holds, and indeed, neither of them validates (27b). We thus need another way of restricting the coordination relation to ensure that this holds. As one way to do this, I propose to restrict the coordination relation in the following way: if two different files that a single subject has are coordinated, then, they are linked in the sense of Recanati (2012, p. 43), where “[w]hen two files are linked, information can flow freely from one file to the other, so informational integration/exploitation becomes possible.”

4.3 Symmetricity, transitivity, and Edelberg’s Arsky–Barsky case

Let us consider (27c), repeated below:

The inference from (33a) to (33b), taken from Edelberg (1986, 1992), gives us an example of this inferential pattern.

According to the present account, (33a) and (33b) are paraphrased as (34a) and (34b), respectively.

Given those paraphrases, the restriction that the coordination relation is symmetric validates the inferences of the pattern of (27c).

Is (27c) valid? Now, consider the following scenario:

The Arsky–Barsky case: Two detectives, Arsky and Barsky, recently investigated an apparent murder on Chicago’s south side. [...] They discussed the case at length, and jointly concluded that Smith was murdered by a single person, but neither has anyone in mind as a suspect. Yesterday, the two detectives investigated another apparent murder, this time on Chicago’s north side. [...] Arsky and Barsky each inferred that Jones was murdered by a single person. Barsky thinks that the man who murdered Smith is the same person as the man who murdered Jones. Arsky disagrees. She thinks that Smith and Jones were murdered by two different people, though she has no one in mind as a suspect for either case. The two detectives argue at length over whether the man who murdered Smith is the same person as the man who murdered Jones. [...] In reality, neither Smith nor Jones was murdered. (Edelberg, 1992, p. 577)

Edelberg points out that under their natural readings, (33a) is true, but (33b) is false in the Arsky–Barsky case (Edelberg, 1986, 1992). Doesn’t this mean that (27c) is invalid?

Not necessarily. In addition to the datum above, Edelberg points out that there is a minor, less natural reading in which (33b) is true in the Arsky–Barsky case (Edelberg, 1992, p. 583). This shows that the Arsky–Barsky case does not invalidate (27c). Moreover, (35) is true in the Arsky–Barsky case (Edelberg, 1992, p. 579).

Those data fit the following description of the Arsky–Barsky case from the conceptual perspective. Arsky has two different mental files. One contains the information of being-a-murderer-of-Smith with the belief mode (henceforth, X), and the other contains the information of being-a-murderer-of-Jones with the belief mode (henceforth, Y). However, Barsky has one mental file that contains the information of being-a-murderer-of-Smith and the information of being-a-murderer-of-Smith with the belief mode (henceforth, U). X and U share a common focus (‘the murderer of Smith’, so to speak), based on the fact that Arsky and Barsky together investigated and discussed the apparent murder on Chicago’s south side. X and U are thus coordinated. Y and U share a common focus (‘the murderer of Jones,’ so to speak), based on the fact that Arsky and Barsky together investigated and discussed the apparent murder on Chicago’s north side. Y and U are thus coordinated. However, because Arsky concluded that Smith and Jones were murdered by two different persons, X and Y do not have any common focus. Therefore, X and Y are not coordinated. (36) summarizes the coordination relation among Arsky’s and Barsky’s mental files in this description.

As Arsky believes that the one who murdered Smith is not a murderer of Jones, X contains the information of not-being-a-murderer-of-Jones with the belief mode. Similarly, Y contains the information of not-being-a-murderer-of-Smith with the belief mode. It is natural to deem that the truth of (33a) is underlain by X and U, and that U is coordinated with X. The fact that X is coordinated with U and X contains the information of not-being-a-murderer-of-Jones is naturally taken as responsible for the truth of (35). Simultaneously, since X is coordinated with U, (33b) is true. The natural false reading of (33b) is obtained when one focuses on the fact that Y, which is coordinated with U, does not contain the information of being-a-murderer-of-Smith.

According to this description, the reason for the falsity of a natural reading of (33b) in the Arsky–Barsky case is not that X (Arsky’s mental file for a murderer of Smith) is not coordinated with U (Barsky’s mental file of a murderer of Smith and Jones). Rather, the reason is that Y (Arsky’s mental file for a murderer of Jones) is coordinated with U and does not contain the information of being-a-murderer-of-Smith. Why is the false reading of (33b) significantly more natural than its true reading? The above description suggests that this is because using X to interpret the second sentence of (33b) is less natural than using Y to interpret it. Why is this so? Let me suggest the following pragmatic story. In the present case, if the embedded sentence of the first sentence is ‘someone murdered Jones,’ then, the mental files that contain the information of being-a-murderer-of-Jones become salient. This makes using Y more natural than using X to interpret the second sentence of (33b). More generally, the information stated in the embedded sentence that contains the antecedent makes it more natural to use, if any, mental files that contain the same information in interpreting a subsequent anaphora than to use mental files that do not—technically, we may suppose that the information stated in the embedded sentence containing the antecedent tends to implicitly restrict the domain of quantification over mental files to include only such files unless the domain is empty.

Consequently, those data are compatible with the view that the coordination relation is symmetric.

Finally, consider (27d), which is instantiated by the inference from (37a) and (37b) to (37c).

The Arsky–Barsky case invalidates (27d). As we have seen, in the Arsky–Barsky case, (37a) and (37b) are true, and the present semantics correctly predicts so. However, there seems to be no true reading of (37c).

The Arsky–Barsky case also witnesses the view that the coordination relation is not transitive: X is coordinated with U, U is coordinated with Y, but X is not coordinated with U. Given this, together with the following translation of (37c), the present semantics correctly predicts that (37c) is false (again, for simplicity, I ignore the possible complexity induced by two occurrences of ‘Arsky’).

In the next section, let us consider de re cases.

5 De re interpretations

5.1 De re anaphora

So far, we have concentrated on cases of intentional identity: cross-attitudinal anaphora in which both an anaphoric pronoun and its antecedent appear in attitude contexts and whose truth does not depend on mental states’ being about any external objects. However, an anaphoric pronoun in an attitude context can be de re, in the sense that it takes as its antecedent a term appearing outside any attitude context. To repeat the example in the introduction:

Let us call such anaphora de re anaphora. In this section, I sketch a way to extend the DRT account of cross-attitudinal anaphora presented in the previous sections to cover de re anaphora.

The DRT account in Kamp et al. (2011) explains de re anaphora of the kind illustrated by (5) by using external anchoring, which constitutes the third component of attitude ascription conditions. Within the present framework, metadiscourse referents allow us to describe external anchoring by the following new DRS condition:

which is read as ‘the metadiscourse referent [r] is externally anchored to the discourse referent x.’ Roughly speaking, EA([r], x) means that the mental file represented by [r] is about an object represented by x. Formally, V(EA)(w) is a partial function from \(MF_w\) to \(D_w\).

This condition is used to register the anaphoric link between an antecedent outside an attitude context and an anaphoric pronoun in an attitude context as follows. The first sentence of (5) is translated as (40a), which constitutes the context of interpreting its second sentence. The second sentence of (5) is translated as the preliminary representation (40b).

To deal with cases of de re anaphora, in addition to the rule specified as (18), I introduce the following new rule for anaphora resolution: a way to find a suitable antecedent for a pronoun in the embedded sentence of an attitude report is to find a discourse referent \(r'\) such that:

Contrary to anaphora resolution by (18), when anaphora is resolved in accordance with (41), the presupposition \(\phi \) triggered by an anaphoric pronoun in an attitude context is not embedded, in the sense that the attitude report whose complement contains the pronoun as a whole presupposes that something satisfies \(\phi \) in the context of interpretation.

In (5), (40a) is the context of interpreting (40b). To find a suitable antecedent for ‘she’ in accordance with (41) is to find a discourse referent that is accessible from [y] and that satisfies the presupposition triggered by ‘she’. x in (40a) is such a discourse referent because (i) it is accessible from [y], (ii) the condition pers(x) is entailed by the condition \(delegate'(x)\), and (iii) the condition female(y) can be added to (40a) by accommodation. The presupposition triggered by ‘she’ in the second sentence of (5) is thus properly resolved by taking x in (40a) as the antecedent of [y] in (5b).

The information that x is the antecedent of [y] is registered by adding the DRS condition EA([y], x) to the matrix DRS whose universe contains [y]. We then obtain (42) as the result of the presupposition resolution of (40).

and merging them results in (43), which is a DRS translation of (5).

Let us summarize two different strategies of anaphora resolution in attitude contexts. An anaphoric pronoun occurring in an attitude context introduces a metadiscourse referent that must be associated with an appropriate standard or metadiscourse referent as its antecedent. On the one hand, when the antecedent is a metadiscourse referent, the presupposition trigged by the pronoun is embedded in an attitude context in a ‘subject-free’ manner, and the anaphoric link is registered by using the coordination predicate. This yields cases of intentional identity, which can be regarded as a kind of de dicto interpretation. On the other hand, when the antecedent is a standard discourse referent, the presupposition trigged by the pronoun is not embedded, and the anaphoric link is registered by using the external anchoring relation EA. This yields cases of de re anaphora.

5.2 Specific and opaque readings, de re readings, and external anchoring

For cases of intentional identity, so far we have considered de dicto readings of the first sentences of them, that is, attitude reports whose complements contain indefinites. Before closing this section, it is worthwhile considering how the additional resource of the external anchoring can be used to explicate other readings of such attitude reports and how they complicate the interpretation of subsequent attitude reports that contain anaphoric pronouns. Here we consider specific and opaque readings in the sense of Szabó (2010) and de re readings (specific and transparent readings). The specific and opaque reading of, for example, (44a) is one paraphrased as (44b), and the de re reading of (44a) is one paraphrased as (44c).

Within the present framework, the specific and opaque reading of an attitude report can be articulated as a reading where (i) the restrictor of the indefinite in the attitude report is interpreted as contributing the corresponding condition to the content DRS, and (ii) the metadiscourse referent, [x], introduced by the indefinite, is described as EA([x], y) in the matrix DRS, where y is a standard discourse referent. Thus, the specific and opaque reading of (44a) is represented as (45).

Even though it is not entirely clear how such a reading is obtained, based on the present account, we can speculatively give the following pragmatic explanation. According to the present account, (44a) is semantically interpreted as follows (its de dicto reading).

I speculate that the specific and opaque reading in question is obtained through pragmatically enriching (46) by adding a discourse referent y to the universe of the matrix DRS and EA([x], y) to its condition. This enables us to explain specific and opaque readings without appealing to split quantifier raising that Szabó (2010) assumes to explain them.

The de re reading of (44a) can be represented as follows (I owe this point to an anonymous reviewer):

How to obtain such a reading? The present account does not provide a basis for such an easy pragmatic story as one presented for specific and opaque readings. A possible, again speculative, explanation would appeal to quantifier raising. Before semantic interpretation, the indefinite ‘a delegate’ can raise to take scope over the subject ‘John,’ leaving a trace. The result can be represented as (48a). By assimilating traces with anaphoric pronouns, one can first translate (48a) as the preliminary representation (48b). To track the connection between a raised DP and its trace, which is represented by coindexing in (48a), it is required that a moved DP and its trace, which are coindexed in a logical form, introduce discourse referents with the same index. We further add to the resolution rule (41) a new requirement that the antecedent of \([r_i]\) must be \(r'_i\) or \([r'_i]\) (the antecedent of \(r_i\) must be \(r'_i\)). Then, we obtain (47) from (48b) (with suitable ‘variable’ replacement).

Finally, how do de re readings and specific and opaque readings complicate the interpretation of anaphoric pronouns in subsequent attitude contexts? Given two different strategies of anaphora resolution in attitude contexts discussed so far, both de re readings and specific and opaque readings open two different possibilities of anaphora resolution. The metadiscourse referent [x] introduced by an indefinite in a preceding attitude report can still be used as an antecedent, which results in intentional identity. Moreover, the discourse referent y that serves as the external anchor of [x] is also available as an antecedent. This results in a de re interpretation of the subsequent attitude report.

6 Conclusion

This paper proposed a DRT account of anaphora in attitude contexts, based on the idea that coordination between subjects’ mental files plays a crucial role in cross-attitudinal anaphora. This idea was implemented by introducing metadiscourse referents and the coordination predicate into the DRT language—in models, they correspond to mental files and the coordination relation between them, which are taken as primitive in the semantics—and using them to record anaphoric linkage across attitudinal contexts. It was confirmed that the characterization of the coordination relation as sharing a common focus suggests that the coordination relation is reflexive and symmetric, but not transitive, and how the proposed semantics, together with this restriction, explains some inference patterns of cross-attitudinal anaphora. In addition, the proposed semantics is expanded to cover de re anaphora, where an anaphoric pronoun in an attitude context takes the antecedent appearing outside any attitude context, by introducing the external anchoring relation into the semantics. Consequently, there are two different strategies of anaphora resolution in attitude contexts, one resulting in intentional identity, and the other resulting in de re anaphora.

Before ending this paper, I would like to specify what it could not discuss. First, the proposed account has many similarities with some seminal works on intentional identity. In particular, Asher (1987), Edelberg (1992), Dekker (1997), Dekker and van Rooy (1998), and van Rooy (2000) share with the present account the core idea that the coordination relation or some similar relation underlies cross-attitudinal anaphora. It is thus important to compare it with those similar approaches. Second, this paper has mainly focused on cases of anaphora across belief reports and only marginally discussed cases involving attitudes other than belief. We have also focused on cases of first-order attitude reports in which no attitude report is embedded in an attitude report. Yet arguably, the present account seems to have good resources to construct semantics of cross-attitudinal anaphora in general. Thus, it is also important to discuss how to extend the basic account presented in this paper to cover higher-order attitudes and attitudes other than belief. Due to space limitations, I have to leave the discussion of these important issues for future research.

Notes

This is so if we understand \(\exists \) as existential quantifier in the standard manner. One may wonder whether the problem will be solved by introducing existentially unloaded quantifier à la Meinongianism (Parsons, 1980; Zalta, 1988; Priest, 2016). Unfortunately, as Edelberg (1986) shows, existentially unloaded quantifiers are not sufficient for obtaining a correct analysis of cross-attitudinal anaphora.

This does not mean that such overlap is not required. For example, suppose Nob believes that a wolf-man and not a witch killed Cob’s sow. In such a case, I tend to say that (1) is not true. But, in this paper, I leave open the question of how much overlap is required. Note also that it is still the case that, in some situations where the reading of (1) is true, Hob and Nob may disagree on what a witch did (Geach, 1967, p. 632). For example, add to the Hob–Nob case the assumption that Nob denies that a witch blighted Bob’s mare because he thinks that the witch harms only cows. (1) is true even in the case of this additional assumption.

This does not exclude the possibility that two mental states being about the same object are coordinated. Indeed, such cases are more common than cases such as the Hob–Nob case. Consider a case where John told Mary about a man he actually met yesterday (he was not daydreaming in this case) and Mary believed what John said. In contrast, for two mental states to be coordinated their being about the same existent object is not sufficient. Consider the case where John and Mary met the same man yesterday, but they do not talk about their private meeting.

Coordination can be intrapersonal. For example, when you see an apple in front of you and think that it looks delicious, your thought is reasonably regarded as sharing a common focus with your perceptual experience. The same holds even when you hallucinate about an apple.

There is a growing interest in the notion of coordination in recent philosophy of language and linguistics (see Fine, 2007; Recanati, 2012; Cumming, 2014a; Moltmann, 2015). However, different authors characterize the notion differently. This can be illustrated by pointing out different opinions in what are the relata of the coordination relation. Like in the passage quoted at the beginning of this paper, Asher takes coordination as a relation between attitudes of agents. Cumming (2014a) takes it as a relation between mental symbols in a certain kind. Fine (2007) takes it as a relation between occurrences of expressions. Moltman (2015) takes it as a relation between intentional referential acts. In this paper, I take coordination as a relation between mental files. Even though these theorists seem to have certain common points, it is not clear exactly how they are related to each other. In this paper, I focus on developing my own account and leave it to future research to elucidate how it is (and is not) related to other theories appealing to the notion of coordination.

The notion of entity representation or the one of conceptual individual might do well, too. I leave it to the readers to consider how the present proposal can be expounded based on these notions.

Precisely speaking, DRSs and discourse referents are not mental representations (for example, DRSs are set-theoretic entities that are abstract but not mental). They are theoretical entities postulated by linguists as a kind of ‘scientific model/representation’ (in the sense in philosophy of science) of linguistic interpretation. More specifically, they can be understood as parts of a scientific model/representation of the psychological process of linguistic interpretation, in particular, as scientific models/representations of mental representations that hearers construct during the interpretation of discourse. In this paper, to avoid unnecessary complexity, I blur this distinction between a scientific model/representation and the phenomena that it models and speak as if DRSs and discourse referents were mental representations they model.

Again, I blur the distinction between DRSs and discourse referents as models and the mental files they model (see fn. 8). If we keep the distinction precisely instead of saying that metadiscourse referents are representations of mental files, we should carefully state the claim in the following way. When a hearer interprets a belief report such as ‘Mary believes that a delegate arrived,’ they construct a mental file that is about a mental file that Mary has, and metadiscourse referents are parts of a scientific model of such mental files that a hearer constructs.

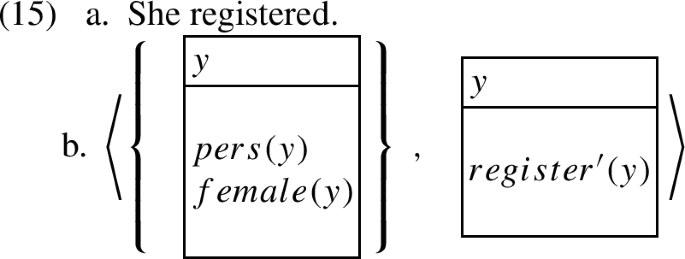

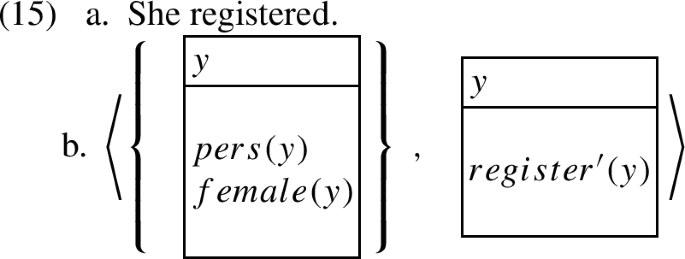

A preliminary representation consists of a presuppositional part (sets of DRSs) and a non-presuppositional, assertive part (a DRS). Consider (15) (cf. Kamp et al., 2011, Sect. 2.3):

In this case, ‘she’ is a presupposition trigger and it requires a discourse referent as its antecedent, which satisfies the conditions being a person and being a female in the context. If x is such a discourse referent in the context of interpretation of (15a), then we can delete the presuppositional part of (15b) and record information of anaphoric link by adding the identity \(x = y\) in the condition set in its non-presuppositional part:

After resolving the presupposition, the non-presuppositional, assertive part is merged with its context to update it. Note that a presuppositional part can be embedded in the condition of the non-presuppositional part of a preliminary representation, as we will see in the cases of attitude reports.

Again, for simplicity, I treat proper names as non-presuppositional.

This presupposes the following expansion of the notion of attitude ascription condition defined in Sect. 2: \(\varPsi \) in an attitude ascription condition \(Att(s, \{ \langle \varPhi , \varPsi \rangle , \dots \} )\) is a DRS or a preliminary representation.

If two or more discourse referents satisfy both (i) and (ii), some pragmatic consideration is required to fix which one of them is the antecedent of the pronoun in question. For simplicity, this paper focuses on cases where (i) and (ii) are enough to fix it.