Abstract

Academic researchers have recently recognised the impact of family firms’ idiosyncrasies and characteristics on financial accounting practices, and identified distinctions between family and non-family businesses. However, this issue still needs appropriate systematisation and discussion. It is important to understand how family businesses’ features shape financial accounting phenomena, but the most authoritative review on the topic dates back more than 10 years. We therefore conducted a systematic review of 133 articles on financial accounting in family firms published in peer-reviewed journals up to 2023. We aimed to assess what scholars have explored so far on this topic, interpreting findings using three levels of analysis: family, business, and individual. The novelty of our paper comes from using this framework to create a thematic map that provides a comprehensive overview of the current research on this topic and developing an extensive research agenda for future studies. The article also provides practical implications for family firm managers, practitioners, and regulators by clarifying the influence of characteristics of family businesses on accounting practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Family businesses play a significant role in the economy (Ferramosca & Ghio, 2018). In the USA, they make up 33% of S&P 500 Industrials firms and 48% of S&P 1500 firms (Khalil & Mazboudi, 2016). Their presence is even more relevant in European and Asian markets. More than 60% of all EU companies (Family Firm Institute, 2018), over 80% of Middle Eastern companies, and 85.4% of all Chinese private entities (Ferramosca & Ghio, 2018) are family firms. The top 750 family businesses in the world produce about $9.1 trillion in revenue and some report total sales higher than the GDP of some countries (Calabrò et al., 2020; Family Capital, 2020; ECODA, 2010; Ferramosca & Ghio, 2018).

This important worldwide presence has prompted scholars in interdisciplinary studies, especially the fields of management, economics, and finance, to study these entities (Siebels & zu Knyphausen‐Aufseß, 2012) and to decipher ‘family dimension as a determinant of business phenomena’ (Songini et al., 2013, p. 362). Family firms strongly differ from non-family businesses (Mengoli et al., 2020) because the relationships between the three interdependent systems of family, business and individuals (family and non-family) complicate and shape business decisions and outcomes (Dyer & Whetten, 2006; Lin & Shen, 2015).

The implications of the peculiarities of family firms for firm decisions and outcomes have also been questioned in the realm of financial accounting. This is the set of activities and practices designed to produce information that is useful for (external) stakeholders by translating firm operations and transactions into a standardised format (e.g., financial statements) following formal criteria from accounting bodies, agencies or local government bodies (e.g., the International Accounting Standard Board, IASB) (e.g., Beaver & Demski, 1974; Songini et al., 2013).

Interest in this form of communication with external stakeholders, such as investors, creditors, or suppliers (Prencipe et al., 2014), was triggered by several notorious scandals involving family businesses from the 2000s to the present. These include Parmalat in Italy, Pescanova in Spain and Adelphia in the USA (Holt et al., 2018). They have prompted scholars to explore whether and how the unique behaviours and characteristics of family businesses influence their financial accounting decisions and outcomes (Bardhan et al., 2015). The academic literature offers competing views of the interaction between family businesses and financial accounting (Ferramosca & Ghio, 2018). For instance, following the agency theory, some scholars have suggested that concentrating ownership in the hands of a controlling family implies lower principal–agent problems (I-Type agency problems) (Cascino et al., 2010; O’Boyle et al., 2010). Family businesses are therefore less likely to manipulate financial reporting for control benefits. However, they may instead face principal–principal problems (II-Type agency problems) (Prencipe et al., 2008) and still engage in bad (or merely specific) financial accounting practices to hide losses and debts, extracting private rents (Prencipe et al., 2014). Additional frameworks have been developed (and applied) specifically for family businesses to understand their financial accounting behaviours. The stewardship theory suggests that (family) managers and (family) owners are driven by more than economic interest, and frequently behave altruistically for the good of the overall organisation and related stakeholders (Anderson & Reeb, 2003). The resource-based view sheds light on the specificities in accounting and financial reporting choices of family businesses. It underlines the value of family capital as a strategic resource for overall business management (Chrisman et al., 2013). The socio-emotional wealth framework (Gomez-Mejia et al., 2011) suggests that the financial accounting behaviours of family businesses might also depend on non-economic factors such as reputation, social capital, the persistence of control, and emotional attachment to the business (Cruz & Justo, 2017; Gomez-Mejia et al., 2014). This may drive family firms to engage in specific accounting practices to preserve ‘non-financial affect-related values’ (Prencipe et al., 2014, p. 366), or to enhance transparency to safeguard family and firm image (Suprianto et al., 2019).

Some scholars have pointed out that ‘accounting research has been somewhat slower in examining the specifics of family businesses’ and that this area of research can be considered ‘still in its infancy’ (Hiebl et al., 2018, p. 277). However, some authoritative literature reviews on the topic have emerged (e.g., Carrera, 2017; Paiva et al., 2016; Prencipe et al., 2014; Salvato & Moores, 2010; Sandgren et al., 2023; Songini et al., 2013). These studies provide meaningful contributions to the field, but also highlight the persistence of significant gaps in the research.

Previous literature reviews have often been characterised by a limited time period. The most recent review on financial accounting of family businesses is more than 10 years old, in contrast to the situation in other accounting fields (e.g., management accounting, auditing). Previous scholars have also focused on a single aspect within financial accounting in family businesses (e.g., earnings management) (Paiva et al., 2016). There is therefore little comprehensive understanding across the whole of financial accounting. However, an increasing number of studies examining financial accounting practices in family businesses have emerged. Moreover, accounting scholars have pointed out the importance of considering financial accounting as a strand in its own right (e.g., Beattie, 2005; Beatty & Liao, 2014). This highlights the need for an up-to-date review of research on financial accounting in family businesses to inform the academic debate.

Perhaps more importantly, the authors of previous reviews have attempted some classification of the reviewed articles. However, no previous review has used a framework that is specifically designed for family businesses, such as that proposed by Habbershon et al (2003). This framework considers family businesses as systems composed of three interdependent components or levels: the controlling family, the business, and the individuals (Habbershon et al., 2003). Several literature reviews on family businesses have used this framework (Bettinelli et al., 2017; Campopiano et al., 2017; Carbone et al., 2021), but none are about accounting.

This article therefore aims to conduct a systematic literature review to analyse and organise the existing knowledge on financial accounting in family businesses. It considers two research questions:

RQ1

What do we know about financial accounting in family businesses in terms of levels (family, business, individual), theories and main streams?

RQ2

What are the unexplored issues in terms of levels, theories and methodology that past research leaves to future research?

To address these research questions, we drew on three databases (ISI Web of Science, Scopus and EBSCO) and systematically reviewed 133 articles on the topic published in academic peer-reviewed journals to 2023. We addressed RQ1 through an extensive in-depth analysis of the reviewed articles, organising them across three levels (i.e., family, business, individual). This approach allows us to decipher the dynamic of the financial accounting phenomenon in terms of investigated objects and outcomes for family businesses, depicting this in a thematic map. We then answer RQ2 by identifying existing gaps and outlining potential directions for future research. This includes levels of analysis, theoretical frameworks, and methodological approaches.

The article provides several contributions to research and practice. From a scholarly standpoint, it advances the family business debate. It is the first attempt (in the last decade) to systematise the main results of financial accounting studies in the family business context by separating the study variables (for empirical studies) and concepts (for qualitative studies) across three coexisting levels (family, business, individual) of analysis in family businesses. Moreover, we detail our literature review across different subfields, i.e., earnings management, accounting quality, financial reporting quality and accounting choices. The thematic map also makes a useful academic contribution, and offers a comprehensive picture of the explored relationships between drivers, moderators and outcomes within financial accounting. Building on this, the study also provides a useful tool for future scholars by suggesting new research questions to be addressed and the methodology and theoretical frameworks that could be used to do so. From a practical viewpoint, the article addresses family managers, practitioners and regulators in evaluating financial accounting determinants and implications in family businesses.

The remainder of the paper is organised as follows: Sect. 2 provides an overview of previous literature reviews on accounting in family businesses, and the main differences between these and our work. Section 3 describes the methodology used to identify and analyse our selected papers. Section 4 presents the literature review findings. Section 5 discusses the results, provides the thematic map and suggests open issues for future studies. Finally, Sect. 6 concludes and provides the main contributions, limitations, and practical implications.

2 Background

Before presenting our analysis, it is helpful to give a brief overview of previous review articles on accounting in family businesses. This section, therefore, provides a summary of the existing knowledge on this topic, and is also useful in considering the identification of future research avenues. We chose to focus on literature reviews on financial accounting, either independently or alongside related research fields such as management accounting and auditing. We have therefore excluded commendable reviews (e.g., Gil et al., 2024; Brunelli et al., 2024; Dasanayaka et al., 2021; Kapiyangoda & Gooneratne, 2021; Quinn et al., 2018; Heinicke, 2018; Helsen et al., 2017; Trotman & Trotman, 2010; Senftlechner & Hiebl, 2015) that explored other accounting topics distinct from financial accounting.

Table 1 summarises six relevant literature reviews on the topic, analysing them in terms of study time period, number of reviewed articles, accounting area, approach to collecting articles and type of analysis. Our comparative analysis leads to the following considerations.

Salvato and Moores (2010) could be considered the pioneering literature review on accounting issues in family businesses. Their review covers an extensive timespan (approximately 30 years) and a copious number of contributions (over 45), spanning three main areas (financial accounting, management accounting, and auditing). They explored the implications of unique characteristics of family businesses, and suggested a broad range of potential areas for future research requiring the distinction between family businesses and concentrated ownership, the adoption of alternative theoretical frameworks and more consistent models.

Songini et al. (2013) provided an extension of Salvato and Moores’ work, albeit over a shorter time period (2010–2013). They clarified the distinctions between financial and managerial accounting and examined the peculiarities of family businesses by summarising the current academic debate.

Prencipe et al. (2014) covered the same time period as Salvato and Moores (2010), but applied stricter criteria for defining family businesses. Their analysis delves into different theoretical frameworks (such as agency theory, stewardship theory, the resource-based view, and socio-emotional wealth), and discusses several definitions of family businesses.

Paiva et al. (2016) focused on earnings management within family businesses, categorising studies into those comparing family and non-family businesses and those exploring the impact of the different types of family businesses on earnings management.

In the same period, Carrera (2017) extended the reviews by Salvato and Moore (2010), Songini et al. (2013), and Prencipe et al. (2014), covering the years 2014–2017 and introducing the specific field of accounting history.

Finally, Sandgren et al. (2023) analysed the specific role of accountants in family businesses. They also discussed the influence of these accountants on financial accounting practices, and examined studies across an extensive timeframe.

Our work builds upon previous literature reviews, but differs in three significant ways.

Firstly, in the selection process, we did not apply any temporal filter, allowing for a broader range of studies, from the earliest work in 2000 (Filbeck & Lee, 2000) to those published by December 2023 (e.g., Chen et al., 2023; Liao et al., 2023), the time at which we performed our search.

Second, in recent years, numerous in-depth reviews have focused largely on the fields of management accounting and auditing. We therefore found it useful to focus our analysis on contributions related to financial accounting. The most authoritative reviews in this field date back more than 10 years, even though this field has probably seen more contributions than many others.

Third, the main characteristic of our comprehensive literature review is the use of the framework proposed by Habbershon et al. (2003) to analyse the articles reviewed. This approach views family businesses as systems made up of three components: the controlling family, the business, and the individuals. This perspective has also been recently adopted in a special issue on family businesses. Daspit et al., (2024, p. 11) noted that considering different levels of analysis and the interplays among them allows for a better understanding of the dynamics of family firms and is ‘essential to expanding knowledge about the unique aspects of family businesses’. We considered the findings of the studies that we reviewed by examining family-level elements concerning different types of family involvement in family businesses (Chrisman et al., 2013). We also captured papers discussing elements at the business level, such as factors concerning the firm itself (Chua et al., 2012), usually company features (e.g., objectives, governance system, resources, or structures) that go beyond the firms’ status as family businesses. Finally, we considered the individual level, usually elements related to individual characteristics, taking into account that individuals can act in the interest of the company, the family, and themselves, depending on whom they represent (Dawson, 2012). This process allowed us to assess how the relationships between the family, business, and individuals (family and non-family) shape financial accounting practices.

3 Method

3.1 Collection procedure

To explore and critically discuss the literature on financial accounting in family businesses, we used the systematic literature review method (Hiebl, 2023; Massaro et al., 2016). Our review was systematic in the collection of the articles, because we adopted a transparent and replicable process, providing an audit trail of the steps in the process (Andreini et al., 2022). We selected the literature by focusing on peer-reviewed papers (including “in press” articles) published in scientific journals considered as certified knowledge to ensure the reliability of our findings (Calabrò et al., 2019). We limited the searches to documents in English, but placed no restrictions on the publication date. We aimed to include all relevant papers published (or available online ahead-of-print) up to December 2023.

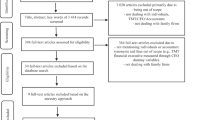

Our selection strategy followed four steps, summarised in Fig. 1 in the form of a PRISMA flowchart (Moher et al., 2009). In the first step, we identified all articles relevant for review, drawing from the Scopus database, ISI Web of Science internet library source and EBSCO Business Source Complete, which are all generally accepted sources for literature reviews (Calabrò et al., 2019; Magnacca & Giannetti, 2023). We used a Boolean search, with a truncated combination of two groups of the strings listed in Fig. 2. The search followed an inclusive collection strategy: the first part covered financial accounting, and the second part considered family businesses (Brunelli et al., 2024; Carbone et al., 2021). For both keyword groups, we used asterisks to catch and include suffixes (Gil et al., 2024). The analysis was conducted for all papers whose title, abstract and/or keywords included at least a search string for each set. The search returned a total of 3256 articles (1051 from Scopus, 1443 from ISI Web, and 762 from EBSCO). After the deletion of duplicates, 2034 unique documents were included in the screening step.

In the second step, two authors independently screened all titles, abstracts and keywords to determine whether the document was relevant to our research aim. In total, 1736 articles were excluded because they were outside the scope, or they did not deal with either financial accounting or family businesses.

In the third step, we assessed the consistency with the topic of the remaining 298 papers. We read the full text of each publication and adopted double-inclusion criteria for eligibility: one for the focus of the article and one for the ranking-based quality (Abatecola et al., 2013; Carbone et al., 2021). First, an article was included if it focused on financial accounting, either as a concept or dependent variable and it was based on family businesses, as a setting or an influencing factor (not just a control variable). In case of disagreement, a third independent expert ensured the accuracy of the choice (Cirillo et al., 2018). Second, in line with previous review studies (e.g., Gil et al., 2024; Sandgren et al., 2023), the article needed to meet specific journal quality criterion to be included (Solomon et al., 2003). This required inclusion in the Academic Journal Guide (2021) of the Chartered Association of Business Schools (ABS). This ensured that the inclusion/exclusion process, as well as being even more transparent, takes into account a minimum level of applied research rigor and excludes potentially predatory journals (Kraus et al., 2020a, 2020b). This process led us to exclude a further 174 articles, leaving 124 articles for inclusion in our literature review.

In the fourth step, we hand-searched and tracked by citation additional articles, to avoid missing significant papers (Magnacca & Giannetti, 2023). We examined highly ranked top journals in the accounting, governance, entrepreneurship, finance, and management fields. This ‘ancestry approach’ supplemented our collection with a further nine papers. We therefore had a final collection of 133 articles published in 71 high-ranked journals.

3.2 Analysis

Having completed the dataset of articles, we then performed a literature analysis. First, we classified papers using a set of items informed by previous reviews (Calabrò et al., 2019; Carbone et al., 2021; Gil et al., 2024). Two authors independently read all the articles and coded them on the basis of theoretical framework, study design, setting, family focus and research subfield. In case of disagreement in classification, we discussed the coding or involved an external scholar to provide a final interpretation (Carbone et al., 2021). For the theoretical framework, we classified the papers by their theoretical lens (e.g., agency theory, socio-emotional wealth theory). On study design, we considered the sample size, time period and company type (e.g., listed and unlisted firms). For the setting, we distinguished the articles on the basis of the geographical context (e.g., Italy, USA, multiple countries). The focus of the papers allowed us to understand if an article investigated only family businesses or compared them with other firms. Finally, the research subfield was identified according to the financial accounting concept or variable explored.

After the classification of articles, in line with previous literature reviews (e.g. Bettinelli et al., 2017; Campopiano et al., 2017; Carbone et al., 2021), we qualitatively systematised the literature by interpreting its findings through three levels of analysis: (i) family, (ii) business, and (iii) individual level. We independently analysed the papers and extracted the ‘level’ information as follows: we identified (i) variables or (ii) main issues addressed by empirical and qualitative studies, and classified them as at the family, business, or individual level. Once this information was gathered, we were able to assess the levels of analysis investigated and their relationships, distinguishing the driver and outcome variables in each research field. For empirical articles, we classified the paper into the family level when it: (i) provides a comparison between family and non-family businesses on financial accounting; (ii) investigates how family heterogeneity influences financial accounting; (iii) investigates how family business status/heterogeneity shapes the relationship between an element at business/individual level and financial accounting. We classified a paper as being at the business (or individual) level when it: (i) investigates the influence of business (or individual) elements on financial accounting within family businesses, or (ii) investigates how a business (or individual) element shapes the relationship between family business status/heterogeneity and financial accounting.

4 Findings

4.1 Descriptive findings

Before discussing the findings of our qualitative analysis, we briefly offer a descriptive overview of the articles included in our review. Figure 3 shows the trend of the papers on financial accounting in family businesses by providing the number per year and cumulatively from 2000 to 2023. The number of papers grew from 22 in the first decade of analysis (2000–2010) to 111 in the last twelve years (2011–2023), suggesting that there is growing academic interest in this research domain. Indeed, significant changes in accounting standards (e.g., IFRS 10, 11, 12) and regulatory measures (e.g., Sarbanes–Oxley Act, EU Transparency Directive) have followed accounting scandals around the world (e.g., Olympus in 2011, Tesco in 2014, Toshiba in 2015), some of which also involved family businesses (e.g., Satyam Computer Services in 2009; Tony Goetz in 2018). Accounting researchers have therefore also focused increasingly on family businesses. This is partly because family businesses are the most widespread organisational form (Carney et al., 2017) but also because their peculiarities have been found to affect all business dimensions (De Massis et al., 2018), including financial accounting (Salvato & Moores, 2010).

The papers in our collection were published in 71 top-ranking journals on the ABS list. Most articles were published in the accounting area (71 papers) compared to the family business one (20 papers). However, the most popular journals, in terms of the number of papers published, are in the family business field: Family Business Review (8 papers), Journal of Family Business Strategy (5), and Journal of Family Business Management (7), suggesting that the push towards the topic of financial accounting in family businesses comes from scholars on the family business side.

Table 2 provides a description of the articles by the other classification criteria. Agency theory was the main theoretical perspective used (64 papers). The literature on financial accounting in family businesses tends to explore the implications of the convergence (divergence) of interests between owners and managers (family shareholders and minority shareholders) and how the “alignment effect” (“entrenchment effect”) influences the quality of accounting choices and practices. Another relevant perspective is socio-emotional wealth (17 papers). Using this framework, papers interpret family businesses’ accounting choices as ways to reach non-economic goals, such as control, transgenerational success, social capital, business and reputation, and suggested that these were part of an emotional connection. Other relevant theoretical lenses were also used including legitimacy theory, and stewardship theory, and these approaches were often combined to consider all the peculiarities of family businesses in the analysis.

Shifting attention to the study design, most of the articles are empirical research (130 papers), mainly using panel data analysis (109). There were very few qualitative articles, with just one case study, and two conceptual research papers. The main settings covered are China (20 papers), USA (18) and Italy (12), followed by a smaller concentration of articles in other countries or across several countries.

Most of the papers investigate the differences in financial accounting between family and non-family businesses (i.e., family business status; 101 papers). Fewer concentrate only on the characteristics of family businesses (i.e., family heterogeneity; 26 papers). Some authors looked first for a difference between family and non-family businesses and then analysed the peculiarities of the family businesses only (6 papers).

Finally, our analysis highlights that the literature on financial accounting in family businesses can be organised into four subfields: earnings management (68 papers), accounting quality (34), financial reporting quality (23) and accounting choices (8).

4.2 Analytical findings

The next few sections present the qualitative findings of our review across the four sub-fields identified (earnings management, accounting quality, financial reporting quality, and accounting choices) and each level of analysis (family, business and individual).

4.2.1 Earnings management

Articles in this subfield focus on managerial discretion to use flexible accounting practices to influence reported earnings, alter financial reports and maximise corporate value (Healy & Wahlen, 1999).

Most studies in this subfield investigate the family level. We identified three research streams. The first is whether and how family and non-family businesses differ in terms of earnings management. With some exceptions (e.g., Vieira, 2016), research largely supports the assumption that family business status matters for earnings management practices. Following the socio-emotional wealth approach, family businesses are less likely to manipulate earnings to avoid economic and socio-emotional wealth losses and protect the firm position and reputation (Liu et al., 2017; Martin et al., 2016). Alongside, according to the agency theory and the ‘alignment perspective’, the family nature of the controlling shareholder is consistent with better monitoring of managers (Jiraporn & DaDalt, 2009), a long-term investment horizon (Borralho et al., 2020a), reputation concerns (Tong, 2007), and less opportunistic rent extraction (Fan et al., 2023). That is, there is generally a low level of earnings management practices (Borralho et al., 2020b) because family businesses tend to be seen as assets to be transferred to heirs (Bona Sánchez et al., 2007).

The ‘entrenchment hypothesis’, however, states that family businesses tend to engage in earnings management practices (Bonacchi et al., 2018; Cherif et al., 2020) to expropriate minority shareholders (La Rosa et al., 2020; Jara Bertin & Lopez Iturriag, 2014; Paiva et al., 2019) and retain transgenerational control (Prencipe et al., 2008). This facilitates family shareholders’ pursuit of their objectives (Chi et al., 2015; Jara-Bertin & Sepulveda, 2016; Zhao & Millet-Reyes, 2007).

Family business status also influences the choice of earnings management type, although again the results are mixed (Alhebri & Al-Duais, 2020; Attig et al., 2020; Khosravipour & Yaghoobi, 2017). Most papers show that family businesses engage more in accrual-based earnings management activities (i.e., through estimation and accounting methods that have no direct impact on cash flow) (Al-Begali & Phua, 2023). This is because they are able to control accounting reporting policies (Chi et al., 2015; Yang, 2010) and can therefore improve results for family/individual benefits (Sérgio Almeida-Santos et al., 2013) and business survival (Achleitner et al., 2014). However, there are some exceptions (e.g., Liu et al., 2017), when family business status hampers accrual-based earnings manipulations, like income smoothing practices (Prencipe et al., 2008; 2011), less opportunistic behaviours in rent extraction (e.g., Attig et al., 2020) and socio-emotional wealth preservation (e.g., Calabrò et al., 2020).

Some studies suggest that family businesses are less likely to engage in real-earnings management (i.e., through operational activities that directly affect cash flow) (e.g., Alhebri & Al-Duais, 2020). The shareholder’s effective control discourages discretionary behaviours from management (Al-Begali & Phua, 2023; Eng et al., 2019; Ghaleb et al., 2020) to avoid future implications for company survival and reputation (Al-Duais et al., 2022) and transgenerational sustainability (Achleitner et al., 2014). However, other studies found that family business status may positively influence the use of real-earnings management (e.g., Al-Begali & Phua, 2023; Attig et al., 2020) to facilitate the rent extraction in family-controlled firms (Alhebri et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2023; Razzaque et al., 2016). This happens especially in critical situations for the business, for instance, during the COVID-19 pandemic (Rahman et al., 2023).

The second line of inquiry analyses how family businesses’ heterogeneity shapes earnings management.

Some studies investigate the effect of family involvement in ownership and management. An increase in family shares makes the II-Type agency problem significant (Stockmans et al., 2013) and fosters an incentive to manipulate earnings and achieve private benefits of control (Ghaleb et al., 2020). Similarly, family managerial involvement increases earnings manipulation up to a certain level, after which mutual monitoring and reputational risks reduce earnings management practices (Ferramosca & Allegrini, 2018; Mohammad & Wasiuzzaman, 2019).

With regard to family generation, family businesses controlled by the first generation prioritise family interests to avoid any risky actions that could damage the family image and name, like earnings management practices (Suprianto et al., 2019). The involvement of younger generations is also acknowledged to reduce earnings manipulation because of the limited role of socio-emotional wealth in later generations (Stockmans et al., 2010; Tommasetti et al., 2020).

Still from the socio-emotional wealth perspective, an increase in socio-emotional wealth orientation among owners and managers enhances earnings manipulation to maintain the family’s dominant position (Gomez-Mejia et al., 2014; Corten et al., 2021). This remains true even if it might lead to avoiding manipulation to protect the family image (Gomez-Mejia et al., 2014; Calabrò et al., 2020). Specifically, family business eponymy, as a proxy for identity and reputational concerns in socio-emotional wealth dimensions, emphasises the identification of the family with the firm and generates a negative effect on earnings management activities (Sundkvist & Stenheim, 2021).

As for succession, earnings management tends to be used in the pre-succession phase by the incumbent owners. In the case of intra-family succession, e.g., a transfer to the children of the owner, there will be less earnings management, to obtain a fair price according to socio-emotional wealth considerations. However, when the ownership is transferring to external, non-family members, e.g., one or more employees, the earnings management effort will increase to negotiate a higher sale price for their shares (Umans & Corten, 2023).

The third line of inquiry at the family level explores how family dimensions influence the effect of corporate and leadership characteristics on earnings management. Some scholars have explored the moderating effect of family business status. The family nature of the business, denoted by family ownership and/or family presence on the board, can foster the use of earnings management practices. The appointment of family members to corporate governance bodies reduces their monitoring effectiveness on earnings manipulation activities, through characteristics such as board (Jaggi et al., 2009; Prencipe & Bar-Yosef, 2011; Vyas, 2011) and audit committee (Mohammad & Wasiuzzaman, 2019; Jaggi & Leung, 2007) independence. Family business status puts pressure on management to engage in earnings manipulation by positively influencing the effect of leadership features such as CEO duality and CEO financial expertise (Oussii & Klibi, 2023), on earnings management, to provide family benefits. Finally, company behaviours, especially corporate social responsibility (CSR) (Rahman & Zheng, 2023) and related-party transactions (Gavana et al., 2023), and practices of voluntary disclosure (Boubaker et al., 2022), are earnings management-oriented by the nature of family businesses, to preserve shareholder wealth.

Family business status can also disincentivise engagement in earnings manipulation. It negatively moderates the positive effect of political connections (Baig et al., 2023) and strengthens the negative effect of CSR and environmental, social and governance (ESG) disclosure (Kumala & Siregar, 2020; Borralho et al., 2022) and activities (López-González et al., 2019) on earnings management. This is designed to preserve family businesses’ long-term goals and socio-emotional endowments.

Lastly, in terms of family heterogeneity, scholars questioned the moderating effect of generation. They suggested that the negative relationship between family business status and earnings management is strengthened by the presence of second or later generations. These younger generations tend to be sensitive to family image and reputation concerns, with effects on the quality of financial information (Borralho et al., 2020a, 2020b).

Shifting the focus to the business level, our analysis identified two main research streams. The first one investigates the role of firm internal governance in earnings management. Studies have explored both the board of directors and the ownership structure. Concerning the former, most studies suggest that large boards with CEO duality, audit committee ineffectiveness and low levels of independence (Al-Okaily et al., 2020; Chi et al., 2015; Fan et al., 2023; Gavana et al., 2023) result in a high concentration of family power and support opportunistic activities in managing earnings. The opposite is true when there are good board practices. The presence of female (Borralho et al., 2020a, 2020b; Mnif & Cherif, 2020) and independent (Alhebri et al., 2021; Chi et al., 2015) directors, the lack of CEO duality (Borralho et al., 2020a, 2020b) and the directors’ compensation (Alhebri et al., 2021) limit managers’ discretion and reduce their incentive to manipulate earnings. The positive implications of the board of directors in reducing family businesses’ earnings management practices occur both with these board structures and characteristics but also in the presence of a board that is service-oriented (Corten et al., 2021) or that has proper expertise and experience (Ferramosca & Allegrini, 2018). Shifting attention to the role of the ownership structure, some articles suggest that the presence of control-enhancing mechanisms, such as business group affiliation and dual-class shares (Chen et al., 2023; Marisetty & Moturi, 2023; Martin et al., 2016) drive family businesses to increase their earnings management practices. However, most articles have found the opposite, suggesting that group affiliation (Khan & Kamal, 2022; Kim et al., 2022) and large and bank ownership (Jara Bertin & Lopez Iturriag, 2014; Zhao & Millet-Reyes, 2007) limit the financial accounting outcome under scrutiny.

Going a step further in our discussion, the second stream of research investigates the role of external governance in earnings management. These articles suggest that firm demand for external debt influences the level and type of earnings management within family businesses (Attig et al., 2020; Avabruth & Padhi, 2023; Kim et al., 2022). Auditors and analysts also provide external influence. Studies have shown that the presence of large auditors (Borralho et al., 2020a, 2020b) and a high level of auditor–client economic bonding (Al-Okaily et al., 2020) is more likely to be associated with earnings management practices, because of the limited external controls. Concerning analyst coverage, some authors document the benefits to family businesses of being followed by a significant number of analysts for earnings management (Paiva et al., 2019). However, other studies show the opposite (Fan et al., 2023). Finally, still on the external governance mechanisms at the business level, a group of studies suggests that the institutional setting (Attig et al., 2020; Eng et al., 2019) and industry features (Zhong et al., 2022) differently shape the influence of family businesses on earnings management practices.

At the individual level, we found two research streams. The first investigates the role of family leadership for earnings management in family businesses. Even if the founder leader as CEO or chairman could be strongly averse to socio-emotional wealth losses, and therefore avoid earnings management (Zhong et al., 2022; Martin et al., 2016; Wu et al., 2024), there might be an incentive to maximise firm performance through earnings manipulation (Stockmans et al., 2010; Wong et al., 2016). In the same vein, family businesses with a family CEO are more likely to use discretionary accruals to maintain family control, even if they are audited by Big-4 firms (Ntokozi et al., 2022). This is also the case for descendant CEOs, especially with low seniority (Wong et al., 2016). Their lower incentive to preserve socio-emotional wealth results in upward earnings management (Stockmans et al., 2010).

Finally, the second research stream explores the role of non-family decision-makers in implementing earnings management. In the case of external (non-family member) CEOs, studies have found that family businesses have a higher level of earnings management (Stockmans et al., 2010). This is because of the CEO’s willingness to achieve personal goals connected to short-term performance (Yang, 2010) or to a desire to impress the market (Wong et al., 2016). However, within family businesses, professional CEOs (Wu et al., 2024) and accounting experts on audit committees (Suprianto et al., 2019) negatively influence earnings manipulation.

4.2.2 Accounting quality

This subfield includes articles focused on the quality of accounting, defined as the informativeness of the reported numbers (Schipper & Vincent, 2003).

At the family level, articles were grouped into three research streams.

The first one analyses how family business status and heterogeneity affect accounting quality. Aside from some exceptions (e.g., Weiss, 2014), most articles claim that, compared to non-family businesses, family businesses provide high accounting quality (Wang, 2006; Mengoli et al., 2020; Cascino et al., 2010; Jung & Kwon, 2002; Srinidhi et al., 2014; Chen et al., 2008; Ali et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2017; Dal Magro et al., 2017). The alignment of interests, family culture and related value social system (Boonlert-U-Thai & Sen, 2019), and engagement in CSR activities (Brahem et al., 2022) foster better management practices and reduce the probability of accounting misstatements (Duréndez & Madrid-Guijarro, 2018; Ma et al., 2016) and forecast errors (Nowland, 2008). However, some scholars have found no significant difference in the financial reporting quality between family and non-family businesses (Sue et al., 2013). Others found that the number of layers between parent firm and subsidiaries in family businesses is negatively related to earnings quality (Hsu & Liu, 2016).

Findings are not conclusive when looking at family heterogeneity and accounting quality. Some studies agree that accounting quality is particularly high in the presence of family governance involvement (Hashmi et al., 2018), but others argue that family power reduces transparency in order to expropriate minority shareholders (Duréndez & Madrid-Guijarro, 2018; Huang et al., 2014), and therefore negatively affects the accounting quality (Pazzaglia et al., 2013).

The second research stream investigates how family business status and heterogeneity guide conservative accounting practices. With some exceptions (Lin, 2018), most studies consider family businesses to be less conservative than non-family businesses (Basu et al., 2005; Ding et al., 2011; Marzuki & Wahab, 2016). However, family ownership (Marzuki & Wahab, 2016) and directors (Chen et al., 2014) seem to support conservative financial reporting to mitigate agency conflicts and protect long-term viability and reputation. Some scholars have argued that CSR compliance increases conditional accounting conservatism less for family than non-family businesses (Shankar Shaw et al., 2021).

Finally, the third line of inquiry at the family level explores what tone family businesses use in earnings announcements and forecasts. Family businesses are optimistic in their earnings (Huang & Kang, 2019) and cash flow (Nagar & Sen, 2016) announcements. They tend to disseminate more dispersed, less accurate and more optimism-biased forecasts (Zhang et al., 2017), to improve investors’ expectations. Their book values are therefore poorly expressive of the real value of assets without considering the amount of intangible assets (Hasso & Duncan, 2013).

Turning the attention to the business level, we identified two research streams.

The first examines whether business factors influence accounting conservativism in family businesses. On the one hand, CEO duality and cash–vote divergence increase conflicts and agency costs, negatively affecting conservative accounting (Hsu et al., 2021; Lin, 2018). On the other hand, outside board members (Lin, 2018) reduce the information asymmetry and “entrenchment effects” within family businesses, supporting accounting conservatism.

Still at the business level, scholars have also analysed how internal characteristics and institutional context moderate accounting quality in family businesses. Drivers of high quality are good governance practices (e.g., strong board independence, low cash–vote divergence, audit quality choice, absence of dual-class shares) (Ali et al., 2007; Cascino et al., 2010; Chen et al., 2021; Srinidhi et al., 2014) and high level of leverage (Cascino et al., 2010). These all promote monitoring by enhancing transparency, information credibility and high degree of accounting quality compliance (Cascino et al., 2010; Che-Ahmad et al., 2020). The presence of politically connected boards enhances the disclosure of qualitative earnings information to signal value to the market (Bona-Sánchez et al., 2019). Even the institutional context in which family businesses operate could positively affect earnings informativeness. Indeed, while institutional development reduces family businesses’ need to hide their performance by managing reported earnings (Mengoli et al., 2020), the high legal protection of investors limits their interest in manipulating accounting information (Nagar & Sen, 2016).

At the individual level, we identified a single stream of research analysing how relevant governance figures affect earnings quality in family businesses. With a few exceptions (e.g., Che-Ahmad et al., 2020), concerning the influence of the CEO, the literature suggests that family CEOs tend to reduce the quality of earnings information (Pazzaglia et al., 2013). Some authors found a negative relationship between CEO career horizon and earnings quality (Che-Ahmad et al., 2020). Regarding the figure of the founder, her/his ongoing presence ensures accounting information transparency (Boonlert-U-Thai & Sen, 2019). However, when the founder also holds the position of CEO, the tone for earnings announcements tends to be optimistic (Huang & Kang, 2019). Founder CEOs may also pursue personal interests without being hindered by conservatism (Chen et al., 2014).

The influence of CFOs on earnings quality is also analysed and found positive: thanks to their formal value correctness, they ensure sustainability, persistence and conservative estimation of net income in family businesses (Glaum, 2020).

4.2.3 Financial reporting quality

Articles in this subfield deal with the way firms disclose their financial information to stakeholders (Cascino et al., 2010).

At the family level, our review showed three research streams.

The first one investigates how family business status impacts annual report quality. A few studies follow the ‘entrenchment hypothesis’ and suggest that family businesses are less transparent in their annual reports (Esparza-Aguilar et al., 2016), increasing the risk of accounting fraud (Krishnan & Peytcheva, 2019). This is because family principals tend to obscure financial statements for extractive purposes. Other studies follow the ‘alignment perspective’ and highlight that (family) shareholders’ and managers’ overlapping interests reduce the informational gap between them, increasing financial reporting quality (Hutton, 2007) and reducing lead times to financial statements disclosure (Lourenço et al., 2018). The less pronounced I-Type agency costs make family businesses less prone to negatively influence the financial reporting process, resulting in better reporting quality. This leads to lower audit risk and effort than in non-family businesses (Ghosh & Tang, 2015; Mousavi Shiri et al., 2018).

Some studies have found that family business status is a moderating factor. In particular, the family nature of the business, denoted by high family involvement in ownership, negatively affects corporate governance effectiveness, e.g., reducing board independence (Chen & Jaggi, 2000), in internal monitoring of financial reporting quality (Bardhan et al., 2015; Dashtbayaz et al., 2019).

A second research strand analyses how family control affects annual report readability. The literature reports that on average, family businesses issue more readable annual reports than non-family businesses for socio-emotional wealth reasons (e.g., Liao et al., 2023). The socio-emotional wealth perspective suggests that both family power (Drago et al., 2018) and identity (Moreno & Quinn, 2023) increase financial reporting quality in terms of readability to incentivise and maintain the family and firm’s reputation. On the same line, when family branches emerge in later generations, identification with the company diminishes, and future generations tend to publish less readable annual reports (Drago et al., 2018). What remains debated is the effect of family eponymy on the annual report readability of family businesses. Drago et al. (2018) reported that the relationship is negative, because an excessive emphasis on the ‘family identity’ dimension hampers virtuous communication. However, Liao et al. (2023) found that family eponymy fosters the positive effect of family business status on financial reporting readability.

The third line of inquiry explores the level of voluntary disclosure in family businesses, and offers mixed findings. From an ‘entrenchment perspective’, controlling families (both in terms of ownership and family members on the board) lead their firms to disclose less voluntary information (Ho & Wong, 2001), especially about earnings forecasts (Chen et al., 2008), to maintain their power and dominant position (Gomez-Mejia et al., 2014; Al-Akra & Hutchinson, 2013; Darmadi & Sodkin, 2013). Family business status offsets the positive relationship of CEO stock-based incentives on voluntary disclosure (Golden & Kohlbeck, 2017). Moreover, family businesses tend to consider ‘control and influence’ and ‘firm dynasty succession’ as important elements of their socio-emotional wealth, negatively influencing the quality of voluntary disclosure of key performance indicators (Boujelben & Boujelben, 2020).

Conversley, family businesses seem to disclose more (voluntary) information, just in case a professional judgment about external factors, global conditions, and financial warnings is required (Md Zaini et al., 2020). The stewardship view and socio-emotional wealth approach both suggest that family businesses have an incentive to voluntarily disseminate information (e.g., in terms of derivatives, historical and credible information), to improve reputation of the business and family (Kota & Charumathi, 2018; Gomez-Mejia et al., 2014). Moreover, family businesses are also more likely to warn of earnings shortages through earnings management forecasts (Ali et al., 2007).

As a result, scholars considering family business heterogeneity suggest that a limited level of family ownership (25% or less) provides a lower degree of voluntary disclosure. Above the 25% threshold, higher levels of family control result in an increase in the quality of voluntary disclosure (Chau & Gray, 2010).

Moving to the business level, we found one research stream that explores how governance drivers moderate the relationship between family business status and financial reporting quality. Governance encourages annual report quality, representing an effective monitoring factor that reduces agency costs and information asymmetry in family businesses. The presence of institutional investors in ownership promotes voluntary information disclosure (Darmadi & Sodikin, 2013) and audit committee strength reduces the risk of fraud in financial statements (Krishman & Peytcheva, 2019). However, the use of control-enhancing mechanisms, like dual-class shares (Bardhan et al., 2015), and weaker board governance (Liao et al., 2023), reduces the quality of internal control over financial reporting, supporting the extraction of private benefits by family members.

Finally, at the individual level, we found one research stream considering the role of leaders in financial reporting quality. Some articles highlight that the appointment of an independent chair in family businesses positively influences voluntary disclosure (Chau & Gray, 2010). The presence of a founder/family manager also encourages annual report readability (Liao et al., 2023). Other studies, by contrast, found that a family CEO strengthens the negative effect of family business status and voluntary reporting, for entrenchment goals (Chen et al., 2008).

4.2.4 Accounting choices

Articles in this subfield discuss decisions whose primary purpose is to influence accounting system output, including both financial statements published in accordance with GAAP and regulatory filings (Fields et al., 2001).

At the family level, our review showed two research streams.

The first concerns the differences between family and non-family businesses in accounting practices. For long-lived assets, if the pre-write-off earnings are already negative, family businesses determine impairment to protect the reputation of both the firm and the family, limiting write-off manipulation (Greco et al., 2015). They are also more likely to recognise goodwill impairment loss to expropriate minority shareholders by reporting poor performance (Omar et al., 2015). Focusing on disclosure issues, other studies showed that companies considered family businesses because of the high presence of family members on the board are more inclined to provide broader information about the primary sectors in which they operate by adopting the related accounting principle (FRS 114) before it was mandatory (Wan-Hussin, 2009).

In organisational terms, some authors (Rieg et al., 2021) demonstrated that family influence does not significantly affect the formal separation choices between management and financial accounting. Instead, this effect is primarily negatively influenced by organisational pressure (difficult economic conditions and consequent lack of resources), and this impact is partially mitigated by family presence in the firm’s ownership.

The second research strand explores how family businesses engage in IFRS accounting standards. The literature agrees that family businesses are less likely to voluntarily adopt IFRS because extensive disclosure may compromise emotional endowment preservation (Alfraih, 2016; Chen et al., 2016). The adoption of new accounting principles that involve the inclusion of ‘rented’ assets and future payment commitments on the balance sheet can have particularly significant effects on family businesses, worsening the leverage ratio and their financial position more generally. Family businesses might therefore be less inclined to adopt these accounting solutions, instead preferring conservative strategies that contain the level of indebtedness (Fitò et al., 2013). This behaviour is often driven by the desire to maintain family control and protect the business from excessive risks, particularly in terms of indebtedness.

At the business level, only one article considered this line of analysis. It investigates the role of corporate characteristics in the application of financial management techniques in family businesses. Filbeck and Lee (2000) showed that larger family businesses with an external board of directors commonly use more modern and sophisticated practices in their financial accounting techniques than their smaller and less governance-established counterparts.

Similarly, only one paper investigated the individual level, considering the leadership role in the application of financial management techniques in family businesses. Filbeck and Lee (2000) found that family businesses appointing a non-family member in the financial decision-making role use modern and sophisticated financial accounting techniques.

5 Discussion and future avenues

5.1 Thematic map

Figure 4 shows relationships among drivers and dimensions of financial accounting in family businesses to show the current situation set out in the literature, and provide a basis for future investigation. The thematic map represents the family business system as having three components—the controlling family, the business and the individuals. It shows how each of the financial accounting subfields (earnings management, accounting quality, financial reporting quality and accounting choices) is directly and indirectly influenced by factors at these three levels of analysis.

At the family level, both family business status and heterogeneity have been found to be direct and moderating drivers of financial accounting. That is, elements that denote the family nature of the business (such as family ownership or family appointments on the board), and peculiar traits of family businesses, which make them different from each another (such as different levels of family involvement in the business, generational issues and socio-emotional wealth dimensions), have been analysed to assess their influence on financial accounting practices.

At the business level, the literature suggests that the main drivers of financial accounting in family businesses are related to governance mechanisms. These may be internal (e.g., board composition and functioning, control enhancing mechanisms) and external (e.g., leverage, audit firm features), and have been widely investigated. Structural features of the business, such as industry and size, have been identified as moderating drivers only.

Finally, the analysis at the individual level shows leadership roles, such as CEO and Chair, and their family and non-family traits, directly and indirectly affect family businesses’ relationship with financial accounting.

This overview enables us to outline possible future directions by starting from the level(s) (family, business, individual) of analysis and propose suitable methodologies to use and theoretical umbrellas to address these issues.

5.2 Open issues

The thematic map shows that there is ample room for further research. We can identify several research questions to be considered in future studies (Table 3).

First of all, while family business status has been extensively explored, few studies have assessed the role of family heterogeneity in financial reporting strategies. Several studies have attempted to analyse financial accounting practices in terms of socio-emotional wealth considerations and provided conflicting arguments (e.g., Corten et al., 2021; Drago et al., 2018; Tommasetti et al., 2020). However, these studies failed to directly capture the multi-dimensionality of socio-emotional wealth, which completely encompasses the role of the family’s non-financial goals (Laffranchini et al., 2020). Indeed, the categorization of socio-emotional wealth into restricted and extended (e.g., Miller & Le Breton-Miller, 2014; Bauweraerts et al., 2024) calls for research questions at the family level. These might include what is the relationship between restricted socio-emotional wealth and financial accounting? What is the effect of extended socio-emotional wealth on financial accounting? Restricted socio-emotional wealth types include short-term family outcomes and benefits (such as nepotism, extraction of privileged benefits, and granting of privileges). This subordinates strategic decisions to the achievement of goals that fuel the family’s current wealth, even though this attitude may harm the firm in the long run (e.g., Tsao et al., 2021). It is expected, therefore, that in these cases the family will lean towards less transparent financial accounting policies that lead to immediate financial benefits, increasing their current wealth and well-being. By contrast, extended socio-emotional wealth focuses on transgenerational considerations and long-term benefits for the company and stakeholders (Bauweraerts et al., 2024). In this case, the family is very sensitive to the potential reputational damage that the company and the family would suffer if unfair financial accounting practices were discovered, and higher quality financial reporting is therefore expected. To answer these questions, researchers should follow Miller and Le Breton-Miller’s (2014) theoretical categorisation of socio-emotional wealth, and use longitudinal quantitative analysis to capture changes in preferences.

Also from a family heterogeneity perspective, there is a need to focus on non-economic attributes going further than the socio-emotional wealth paradigm. First, it might be meaningful to introduce the concept of morally binding values into the ongoing debate. It is well established that family businesses are values-driven organisations, resulting from the interaction between the family and corporate systems (Distelberg & Sorenson, 2009). However, scholars have recently shown interest in the domain of morally binding values such as religion and spirituality and their interaction with the family business system (e.g., Kellermanns, 2013; Discua Cruz, 2013). These values provide a set of principles that guide business practices and stakeholder relations toward an ethical approach (Azouz et al., 2020; Balog et al., 2014). This is especially true in family businesses, in which the relevance of moral values drives all decisions and behaviours at the interface between family and professional logic (Astrachan et al., 2020). This potentially reaches the boundaries of financial accounting and certainly has implications for it. At the individual level, a possible future research question is: what is the impact of family decision-makers’ binding values for financial accounting? Similarly, at the family level, the research question could be: how does the interaction of morally-binding values and the family business system affect financial accounting practices? Morally-binding values should strengthen the propensity of family businesses to act in an ethically correct way, increasing the quality of financial reporting (the management of profits would decrease). The theoretical umbrellas that might be useful are the theory of spiritual leadership (Fry, 2003) and the topic of social capital (Bourdieu, 1985). Empirically, structural equation modelling (SEM) and multiple case studies may be useful ways to investigate these research questions.

There is also potential to increase knowledge of the image view of the family business brand as a unique source of competitive advantage in family businesses (Blombäck & Botero, 2013). Family firm brand management aims to ensure that stakeholders’ perceptions are different (and more favourable) for family than non-family businesses (Binz et al., 2013). However, whether and how the business owners and leaders choose to portray the family nature of their business to stakeholders within and outside of the business is still an open issue (Astrachan & Botero, 2018). It leads to the following research question: does image view complement family ownership in affecting financial accounting? At both family and individual levels, the issue behind this question is that family owners might strategically communicate a specific family image (‘family promise’) to stakeholders (family as more responsible) and this, in turn, might moderate financial accounting outcomes in either direction. Here, theoretical support can be found in signalling theory (Spence, 1973), and content analysis would be a suitable empirical method.

Lastly, the concept of family philanthropy, or family wealth transfer of net income to stakeholders (Campopiano et al., 2014), would add interesting and unexplored perspectives to the accounting field. Philanthropic initiatives are coherent with a (family) firm’s willingness to act as a good member of the community in which it operates, developing connections with stakeholders (Feliu & Botero, 2016). The ongoing accounting debate is in the attempt to identify factors influencing the accountability of these behaviours (Kimbrough et al., 2024; Maas & Liket, 2011). The suggested research question, at the business level, could be: is there a strategic relationship between philanthropy and financial accounting? At the family level, studies might ask: how do family philanthropic initiatives affect the relationship between philanthropy and financial accounting? The more philanthropic initiatives, the more the family is socially responsible/stakeholder-oriented, and the more (or less) quality of financial reporting (earning management) is expected. Philanthropic initiatives might be used to engage in more earnings management, decreasing its negative effects. The investigation of this research question could benefit from the organisational identity theory (Hatch & Schultz, 2002) and, empirically, from content analysis and multiple case studies.

Shifting the attention to aspects that transcend the focus on family businesses or comparison with non-family businesses, most studies have explored the role played by firm governance features. However, some aspects are still unknown. First, an interesting and relevant—but understudied—topic is the role played by the CFO, generally considered the second-in-command to the CEO (Caglio et al., 2018; Almeida & Lemes, 2020). Two main research questions might be identified at the individual level. The first one is how do CFO family traits influence financial accounting? The literature has explored the traits of family CEOs, but less is known about the CFO role. However, both scholars and practitioners have suggested that CFOs have enlarged their main tasks from the supervision of financial reporting to the development of corporate strategic and financial plans (Datta & Iskandar-Datta, 2014; Firk et al., 2019), with potential implications for financial accounting processes. To properly address these research questions, characteristics such as the family nature of the CFO, CFO generational stage and CFO ownership might be considered. The second avenue related to CFOs might be what is the effect of the CFO’s background on financial accounting in family businesses? Upper-echelon proponents argue that top managerial accounting choices are susceptible to many influences in terms of the individual’s psychological constructs, values, and beliefs (Hambrick, 2007). The assumption is that these unobservable elements are generally the outcome of managerial characteristics and attributes, in terms of past experience and professional path (Hambrick & Mason, 1984). Human capital intangibles owned by family businesses are unique because of the simultaneous involvement of individuals in both the family and the business system (Sirmon & Hitt, 2003), and the alignment of ability (knowledge, skills) and willingness (interest) to perform (Dawson, 2012). It might therefore be interesting to explore how CFOs’ human capital characteristics, proxied by educational level, functional background, firm expertise and industry expertise, might shape the financial accounting process and outcome within family businesses (Almeida & Lemes, 2020). For the first research question on family traits of the CFO, it could be useful to use the behavioural agency model (Wiseman & Gómez-Mejía, 1998). For the second research question, the upper-echelon theory could be more helpful (Hambrick & Mason, 1984). Scholars might leverage surveys and longitudinal panel data methods to investigate both questions.

Another issue insufficiently investigated by governance scholars is the study of social capital impact on financial accounting practices within family businesses. Scholars have defined social capital as ‘the set of resources an individual or organization is able to acquire through a network of relationships, regardless of their degree of formalization’ (Bourdieu, 1985, p. 2). A common proxy for social capital is the number and intensity of connections between board members of distinct companies, commonly known as interlocking directorates (Romano et al., 2020; Rossoni et al., 2018). Studies have explored the effect of interlocking directorates on corporate performance, but yielded inconsistent findings. Some authors have shown that the presence of interpersonal ties enhances better long-term results, increasing the value of the company (Horton et al., 2012; Larcker et al., 2013). Others have highlighted that relationships among board members of companies can promote the exchange of knowledge (Hillman & Dalziel, 2003) and mitigate the negative effects of uncertainty (Beckman et al., 2004; Braun et al., 2019). Conversely, the presence of well-connected directors may adversely affect business performance (Croci & Grassi, 2014) because it can reduce the time and resources of its directors (Fich & White, 2003), weaken control mechanisms (Fich & Shivdasani, 2006), and facilitate opportunistic behaviours (Nam & An, 2018). A few studies have also investigated the specific relationships between the centrality of board members (particularly the CEO) and the adoption of dubious accounting practices, such as tax avoidance or aggressive earning management (Huang & Kang, 2019; Brown & Drake, 2014; Cai et al., 2014; Chiu et al., 2013). None of the cited articles have delved into these issues for family businesses.

The relationship between social capital and financial accounting practices within family businesses may be examined from either a business or individual perspective. From a business standpoint, studies could consider the question: How does family firms’ network centrality affect financial accounting? From an individual perspective, future studies could consider: How does CEOs’ (or board members’) social network centrality shape financial accounting practices in family businesses? Does the impact vary for family and non-family CEOs? The answers are unclear for both business and individual perspectives, given the uncertainties from studies focusing on businesses more generally. The characteristics of family businesses (both tangible and intangible) may also exacerbate these results, sometimes in counterintuitive ways. These proposed research avenues could be grounded in agency theory (Jensen & Meckling, 1976) or the resource-based view (Barney, 1996) and pursued through longitudinal studies incorporating social network analysis, or using surveys and case studies.

Looking beyond governance, less is known about other (non-governance-related) organisational elements. This is the case with the use of digital technologies and the related digital transformation process, which may completely shape financial accounting choices and behaviour. The proposed research question is: what is the impact of digital transformation on financial accounting in family businesses? Previous studies have suggested that family businesses are less likely to invest in digital technologies (Ceipek et al., 2021), because they have ‘little to gain in terms of financial wealth and much to lose in terms of socio-emotional wealth’ (Liu et al., 2023, p. 3). However, the financial reporting and accounting professions have undergone significant metamorphosis because of the rapid integration of digital technologies (Alles et al., 2018). The adoption of artificial intelligence, machine learning, blockchain and big data has led to a paradigm shift, redefining how financial data are processed, analysed, and reported (Abhishek et al., 2024). It could be interesting to explore how, at the business level, the digital transformation of financial accounting takes place within family businesses. At the family level, it could be relevant to address if and how differences among family businesses, especially the generational stage, might influence digital transformation. The research question is: is the generational stage a driver of digital transformation in financial accounting in family businesses? Later generations are often more inclined toward digital technologies (Bürgel & Hiebl, 2023), and are expected to foster digital transformation in financial accounting practices. Both these research avenues might use socio-emotional wealth theory (Gómez-Mejia et al., 2007) and be developed through surveys and case studies.

Another crucial overlooked aspect is the impact of CSR on financial accounting. CSR is a company’s commitment to acting ethically and contributing positively to society and the environment (Carroll & Shabana, 2010; Epstein & Roy, 2003). It can contribute to sustainable business practices, influencing financial accounting procedures and posing challenges in measurement and reporting (Wang, 2006). This topic is crucial to understanding how family businesses integrate sustainability into their operations and how this influences reporting procedures (Stock et al., 2024). Future research could explore various aspects. At the family level, investigations could focus on the following questions: what are the effects of sustainable practices on financial accounting in family businesses compared to non-family businesses? Do these positively or negatively influence the quality of disclosure in family and non-family businesses? (Cuadrado-Ballesteros et al., 2015; Stawinoga & Velte, 2015). Another research avenue could be: how do family businesses incorporate sustainable practices into their financial accounting processes? This would explore whether and how sustainability affects reporting procedures. These topics could be investigated to examine the characteristics of family businesses (family involvement in ownership, management and board positions) that influence sustainability initiatives and financial reporting practices (Broccardo et al., 2019; Campopiano & De Massis, 2015). From a business level perspective, studies could address the moderating effect of business factors on the relationship between sustainable practices and financial reporting disclosure. The research question could be: how do board characteristics moderate the relationship between sustainable practice and accounting quality in family businesses? Studies might explore how sustainable practices influence compliance with accounting standards or the transparency and comprehensiveness of financial accounting and how board characteristics moderate this relationship. Finally, at the individual level, future studies could delve into the attitudes, beliefs and behaviours of family members on sustainability and financial accounting practices. The research questions could be: how do perceptions of sustainability among family leaders influence their involvement in financial reporting decisions in family businesses, and how does the role of family leaders drive sustainability initiatives within financial accounting? This could involve analysing leadership styles, values, culture and strategies of key individuals in promoting sustainable practices and the effect on financial accounting in family businesses (Kariyapperuma & Collins, 2021). All these research avenues could apply the behavioural agency model (Wiseman & Gomez-Mejía, 1998), the socio-emotional wealth theory (Gomez-Mejia et al., 2007) and signalling theory (Spence, 1973), and be explored through surveys and case studies.

Finally, another important factor involving organisational elements besides governance rests in a particular trait of family businesses: resilience (e.g., Kraus et al., 2020a, 2020b; Pont & Simon, 2024). This concept has gained importance recently, as scholars have explored factors contributing to family business longevity and resilience in response to situations threatening both business and family continuity (Beech et al., 2020; Calabrò et al., 2021). The preservation of family legacy, leveraging long-term family ownership, emotional and family interactions, and willingness to hand over the firm to the next family generation, are all part of a robust mix of resources that allow family businesses to exhibit enhanced crisis resilience (Salvato et al., 2020). Given the importance of resilience in family businesses, the proposed research question at the business level is: what is the impact of crises on resilient family businesses in terms of their financial accounting? Resilient family businesses should be more conservative, more likely to maintain a high standard of reporting quality and less willing to manage earnings. This research question could use the socio-emotional wealth and the upper echelon theories, and panel data analysis and multiple case studies would offer solid empirical methodology.

6 Conclusions

Over the years, scholars’ interest in financial accounting in family businesses has increased, making this a promising avenue for future investigations. Motivated by the interesting focus on family businesses in general, and their financial accounting decisions in particular, this study systematically scrutinised 133 peer-reviewed articles published to 2023 to provide a comprehensive picture of the research domain and present a model to steer future research. The paper provides several contributions to both theory and practice.

From a theoretical standpoint, the paper fully unpacks the potential of financial accounting phenomena within family businesses. Our work is the most up-to-date attempt in the last decade to systematise the literature on financial accounting in family businesses without applying any temporal filter. It contributes to the family business debate by considering the literature using a framework of analysis specific to family businesses (Habbershon et al., 2003). It qualitatively analyses the main results of financial accounting studies in family businesses using the three co-existing and interdependent levels in a family business (i.e., family, business, and individual).

It also offers new insights into the accounting literature by considering financial accounting as a stand-alone strand, following the suggestions of accounting scholars (e.g., Beattie, 2005; Beatty & Liao, 2014). It assesses what shapes the relationship between family business features and dimensions of financial accounting by clustering existing contributions into four research subfields (i.e., earnings management, accounting quality, financial reporting quality, and accounting choices).

The paper also provides a thematic map that summarises the main issues and relationships that have been studied. This is a relevant contribution to the interface of family business and accounting literature. This overview shows the interplay between the levels of family business analysis and financial accounting subfields, showing what is known and new areas for investigation. The article then highlights several gaps in research across different levels of analysis, and offers scholars a rich research agenda for the future, calling for a more in-depth deciphering of the role of the ‘family’ in financial accounting. The paper also suggests open research questions, and suitable methodology and theoretical frameworks.

The paper also has practical implications. The role of idiosyncratic family business systems in financial accounting choices and the underlying motivations have been addressed theoretically and empirically. This is beneficial for managers of family businesses, to increase understanding about how the overlapping issues of the family unit, business entity, and individuals can influence the effectiveness of financial accounting practices. The study may therefore expand the capacity and ability of family managers to make a comprehensive assessment of financial accounting determinants and the consequent implications of their behaviour.