Abstract

This paper investigates how early career academics interpret and respond to institutional demands structured by projectification. Developing a ‘frame analytic’ approach, it explores projectification as a process constituted at the level of meaning-making. Building on 35 in-depth interviews with fixed-term scholars in political science and history, the findings show that respondents jointly referred to competition and delivery in order to make sense of their current situation. Forming what I call the project frame, these interpretive orientations were legitimized by various organizational routines within the studied departments, feeding into a dominant regime of valuation and accumulation. However, while the content of the project frame is well-defined, attempts to align with it vary, indicating the importance of disciplines and academic age when navigating project-based careers. Furthermore, this way of framing academic work and careers provokes tensions and conflicts that junior scholars try to manage. To curb their competitive relationship and enable cooperation, respondents emphasized the outcome of project funding as ‘being lucky.’ They also drew on imagined futures to envision alternative scripts of success and worth. Both empirically and conceptually, the article contributes to an understanding of academic career-making as a kind of pragmatic problem-solving, centered on navigating multiple career pressures and individual aspirations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

One of the most notable features of contemporary academia is the role played by projects. Projects are the standard format for organizing research activities and the division of labor at departments (Ylijoki 2016). Moreover, competitive project funding is the most common method used to determine which research projects are deemed worthy of receiving funding and which are not (Bloch et al. 2014). This process of projectification has deeply influenced the social (Franssen and de Rijcke 2018) and temporal (Vostal 2019) structures of academia, with an increase of short-term employment and hyper-competition, especially evident among early career academics (Fochler et al. 2016). For this particular group, projects not only characterize precarious working conditions, but are the very material upon which academic careers are structured, built, and assessed (Bloch et al. 2014; Herschberg et al. 2018).

This article explores how early career academics experience and navigate project-based careers. How do they make sense of their work, careers, and identities becoming increasingly shaped by projectification? What conceptions of worth come to the foreground? And how are such normative understandings negotiated? To address these questions, I draw upon 35 in-depth interviews with fixed-term scholars in political science and history working at four research-intensive universities in Sweden. Whereas prior studies have shown that junior scholars without stable employment are particularly sensitive to the norms and values of academic reward and career systems, the primary focus thus far has been on parts of the natural and life sciences (see e. g. Fochler et al. 2016; Müller 2014). This article extends the literature to disciplines within the social sciences and humanities, exploring how the experiences and practices of early career academics in political science and history are organized in the context of project-based careers.

Adopting a ‘frame analytic’ approach (Goffman 1974), the study contributes a perspective on projectification as a process centrally constituted at the level of meaning-making. Findings show that early career academics in political science and history jointly refer to competition and delivery in order to make sense of their current situation. Forming what I call the project frame, these interpretive orientations feed into a dominant regime of valuation and accumulation. However, while the content of the project frame is well-defined, attempts to align with it vary, indicating the importance of disciplines and academic age when navigating project-based careers. Furthermore, this way of framing academic work and careers provokes tensions and conflicts that junior scholars seek to manage. To curb their competitive relationship and enable cooperation, respondents emphasized the outcome of project funding as “being lucky.” They also drew on imagined futures in order to envision alternative scripts of success and worth. By analyzing how scholars navigate career demands and value conflicts within the project frame, this article contributes to an understanding of academic career-making as a kind of pragmatic problem-solving, centered on balancing between multiple career pressures and individual aspirations.

Impacts of Projectification: Early Career Academics as a Case in Point

While the definition of “early career academics” varies, it generally refers to academics in a phase of transition (Haddow and Hammarfelt 2019). Due to the increasing number of PhD and other temporary staff members compared to permanent positions in recent decades, the transition phase has extended in terms of time (Franssen and de Rijcke 2019) and has become subject to hyper-competition (Fochler et al. 2016). Therefore, the present study employs a rather extensive definition, including scholars who have received their PhD within the previous eight years and who are yet to obtain a permanent position.

Working on temporary contracts, previous research indicates that early career academics is a group particularly affected by the projectification of academic work and careers. As part of the re-organization of academic institutions along the lines of new public management, it is a process entangled with increasing career pressures from, among other things, expanded accountability and performance management (Haddow and Hammarfelt 2019), heightened precarity (Gill 2016), and changing temporalities characterized by an acceleration of work pace (Vostal 2016). The project format is thus not considered “a mere technical organizational tool.” Instead, it “challenges and reshapes research practices and ideals” (Ylijoki 2016: 13), structuring the conditions under which early career academics are socialized (Fochler et al. 2016; Nästesjö 2021; Roumbanis 2019).

Focusing on the mechanisms through which project funding affects the social structures of research groups, Franssen and de Rijcke 2019 argue that the rise in temporary positions as well as the extended length of the temporary career phase means that early career academics must interact with the job and grant market much more often. This impels junior scholars to continuously try to increase their research time, which leads to a differentiation between research intensive and teaching intensive career scripts (see also Ylijoki and Henriksson 2017). Furthermore, introducing competition as a mode of governance, project funding enforces competitive behavior (Müller 2014) while outsourcing epistemic authority to funding bodies and project leaders (Herschberg et al. 2018). Taken together, Franssen and de Rijcke (2019: 146) contend that these features of project-based careers continuously “establish and reaffirm the individual as the primary epistemic subject,” pushing early career academics “towards entrepreneurial behavior.” This, in turn, shapes junior scholars’ approach to their work (Hakala, 2009) and how they construct academic identities (Archer 2008), although not in a one-dimensional way (Nästesjö, 2023).

These observations are part of a larger trend characterized by the individualization of precarity (Gill 2016) and narrowing valuation regimes (Fochler et al. 2016). Under the impact of project-based careers, much of the responsibility for dealing with uncertainty about the future, whether in terms of funding or research, has shifted from the organizational level to the individual researcher (Cannizzo 2018). Exploring the narrativization of success and failure among fixed-term academics in the UK, Loveday (2018) argues that this shift has resulted in a contradictive sense of agency. While success was pictured as “being lucky,” indicating a lack of agency, failure was considered one’s own responsibility, thus conforming to the notion of individualized “enterprise subjects.” Moreover, studying life science postdocs, Sigl (2016) claims that the project format creates a structural link between social and epistemic uncertainties. As a response, junior scholars develop modes of coping often centered on the reduction of risk and the securing of individual merits. According to Sigl, these coping strategies become part of the tacit governance of project-based research cultures. Similar findings have been reported in numerous studies of life science postdocs. This includes how productivity concerns and evaluative metrics shape research practices (Müller and de Rijcke 2018), how the impact of prioritizing first-authorship can hinder collaboration (Müller 2012), and how the competitive structures of project-based careers lead to a narrow conception of worth focused on high-impact publication output and grant money (Fochler et al. 2016; Müller 2014).

With notable exceptions (see e.g. Franssen and de Rijcke 2019; Haddow and Hammarfelt 2019; Steffy and Langfeldt 2022), the life sciences have thus far been the primary focus in studies of how the working practices of junior scholars are influenced by the changing structures and valuation of academic careers. However, an important question is how such changing framework conditions are experienced and dealt with in settings that are shaped quite differently. Hence, one of the contributions of this article is extending the literature to the evaluative contexts of political science and history in Sweden.

Empirical Settings and the Contexts of Projectification

Sweden offers a good example of “how university management has moved towards a managerialist model emphasizing accountability and marketization” (Roumbanis 2019: 198). On a general level, this includes an increasingly formalized research evaluation system emphasizing publication output and external grants (Hammarfelt and de Rijcke 2015) as well as a shift away from block funding to competitive project-based funding (Roumbanis 2019). A significant consequence of evaluating and organizing research in this way is that external funding has shifted from being an additional funding source to being the main source. By affecting who has the right to research time, previous studies of Swedish academia demonstrate how this shift affects authority relations in research (Krog Lind et al. 2016) and the division of labor within departments (Benner 2016). In essence, which obligations and working tasks one has does not depend on the title of their position, but how their position is funded. Moreover, Müller and Kaltenbrunner (2019: 496) argue that the rise of standardized research evaluation and project-based funding feed into formal career incentives at Swedish universities, further emphasizing “the ideals of the individual high-performing academic who publishes in disciplinary journals and attracts the most selective grants.” Such hierarchizations of publication outlets and funding programs mean that junior scholars in Sweden not only have to navigate increasingly precarious working conditions (Roumbanis 2019), but also an intricate game of status (Edlund 2024).

According to Roumbanis (2019: 199), the lack of a common national career system and the growing dependence on competitive project-based funding mean that career paths in Sweden “have become both narrower and less clear.” Whereas the postdoc phase is viewed as a bottleneck in the system (Frølich et al. 2018), what tasks this phase actually contains and how it is funded varies. As it generally takes seven to twelve years for junior scholars in Sweden to reach a tenured position (Swedish Research Council 2015), the early career is often a pie-like arrangement with multiple funding sources. In the social sciences and humanities, these long series of fixed-term contracts tend to involve both research and teaching responsibilities. Still, career advancement is highly dependent on individuals’ success in the funding market (Roumbanis 2019). This is particularly true for early career academics at more prestigious research-intensive universities, such as the respondents in this study. Within these settings, the competiton for project-based funding and future positions are heavily intertwined.

The empirical settings of this study include three history departments (hereafter H1, H2, and H3) and two political science departments (hereafter PS1 and PS2) located at four research-intensive universities in Sweden. Regarded as high-status fields within the humanities and the social sciences, respectively, the competition for funding and tenured positions is fierce. Consequently, early career academics at the studied departments work on temporary contracts for a long period of time and career advancement is synonymous with success in the funding market. However, as disciplines, political science and history also differ in meaningful ways. While political science in Sweden to a large extent has adapted to what is framed as “international standards” regarding, for example, publishing preferences and favored publication language, the history field has only recently begun to adapt to this trend. Therefore, their practices for doing and valuing research have been described as “in flux” (Salö 2017; see also Nästesjö 2021). Additionally, whereas scholars in history almost exclusively work alone or in pairs of two, collaboration is much more common in political science. In contrast to the three history departments, collaborative research groups working in joint projects were considered a standard at the two political science departments. Still, the size of research groups as well as the extent to which they influenced the organizational structures of the departments differed. At PS1, junior scholars tended to work both individually and collaboratively, and the research groups were usually rather small, depending on short-term projects connected to specific grants. At PS2, junior scholars more often worked in larger and formalized research groups or centers. Because these were not only linked to a specific project or grant, but a shared epistemic focus and developed infrastructures for research work – such as joint datasets, budgets, practices for co-authoring, seminars, events, and informal gatherings – these groups or centers to a greater extent shaped the organizational structures and working routines at the department. Because they tended to recruit junior scholars early in their career, the respondents from PS2 had usually been part of a group or a center for a relatively long period of time when being interviewed.

Both at a disciplinary level and at a department level there are factors that create different contexts of projectification. Hence, not only does the present study extend the focus to the under-studied evaluative contexts of political science and history, it also provides an opportunity to make comparisons between and within these empirical sites. This will provide new insights into the meanings and dynamics of navigating project-based careers.

A Frame Analytic Approach

This article introduces a conceptual approach to the study of academic work and careers focusing on how scholars navigate institutional demands by drawing on interpretive frames of meaning. More specifically, I argue that the project may be understood as a particularly dominant frame through which early career academics make sense of themselves and their careers. Because a frame is “characterized not by its content but rather the distinctive way in which it transforms the content’s meaning” (Zerubavel 1991: 11), this is a conceptual approach aiming to investigate projectification as a process constituted at the level of meaning-making. In contrast to previous studies focusing on certain aspects of different types of grants (Edlund 2024; Müller and Kaltenbrunner 2019), this approach seeks to broaden the analytical focus to how the experiences of early career academics more generally are organized in the context of project-based careers.

Initially defined as “schemata of interpretations” (Goffman 1974: 21), frames organize actors’ experience and subjective involvement in a given aspect of social life. Framing is thus centered on answering the question “What is happening here?”. According to Persson (2018: 48), “the idea of posing precisely that question is that the answer is often not a given.” Rather, it must be negotiated with others. However, actors do not have complete freedom to negotiate afresh in each situation. While framing involves the interpretation and application of frames, actors are also constrained by frames. Following Scott (2015: 76), “frames act as blueprints for social conduct, by providing a set of shared meanings [and] understandings of the rules, roles, and rituals to be followed.” From this perspective, the concept of frames answers the additional question “What applies here?” and points to the dynamics between individual’s experience, other people’s expectations, and the patterning of norms and values across situations that governs orderly conduct (Persson 2018: 128). Frames are thus never simply personal choices, but available to people as more or less institutionalized parts of social life – rooted in groups, organizational routines, power, and structures. Furthermore, the prominence of a specific frame is maintained through the use of various procedures that anchor frame activity (Goffman 1974: 247–251).

The concept of frames focuses attention to how the sharedness of a social world is an ongoing accomplishment. Yet, this does not preclude tension. People may have conflicting understandings of what is going on and what is applied, and these disagreements often implicate asymmetry and inequality (Scott 2015: 79). Moreover, Goffman (1974: 45) uses the concept of keying to describe how actors can alter the meanings of activities by transforming them into something patterned. In this way, frames can be laminated or superimposed upon each other, creating multiple layers of interpretation which operate simultaneously (Goffman 1974: 82). To theorize this kind of vulnerability, framing processes may be conceptualized as an ongoing interplay between alignment and disruption (Tavory and Fine 2020). While alignment encompasses actors’ attempt to act in accordance with a shared definition of a situation, disruption is a perceived misalignment forcing actors to rethink what is going on and what is applied. As argued by Tavory and Fine (2020), both alignment and disruption are linked to culturally shaped expectations and presumptions, and as such, they reflect analytically distinct moments that are crucial for actors’ practices and their sense of self.

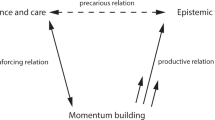

Previous research indicates that the early academic career requires attending to multiple demands, “including intellectual development, gaining reputation in the field, and securing good working conditions” (Steffy and Langfeldt 2022: 321; see also Laudel and Gläser 2008). A key institutional challenge within the Swedish context is to meet these demands while navigating an increasingly projectified career landscape (Roumbanis 2019). Exploring the life worlds of early career academics, this article argues that the project functions as a particularly dominant frame through which junior scholars make sense of themselves and their careers. Analytically, this is done in three steps. First, I analyze the content of the project frame which organizes how early career academics experience institutional career demands. Second, I focus on how they strategically attempt to align with this frame in their research and career practices. Finally, I explore how junior scholars, in the face of tensions and conflicts, negotiate the normative meanings of the project frame through acts of keying.

Method

The study draws upon 35 in-depth interviews with early career academics in political science and history conducted between February and June of 2019. As mentioned, all respondents held temporary contracts. These were mostly project-based research positions limited to one to three years with some teaching responsibilities. Whereas all of the respondents expressed an aspiration to continue with an academic career, they mainly pictured themselves as competing on a national or Scandinavian labor market. In part, this is because only a few ‘international postdocs,’ having received their PhD abroad, worked at the studied departments.

To build a sampling frame, I selected five departments at four research-intensive universities in Sweden and constructed a list of scholars in political science and history having received their PhD degree between 2011 and 2019. Based on descriptive information from CVs and online profiles,Footnote 1 I selected a diverse group of respondents regarding their experience of research, teaching, and administration as well as publishing, mobility, and collaborative work. The selection criteria also ensured variation in terms of academic age, ranging from half a year up to eight years since PhD completion, with a majority of the respondents having spent two to five years at the early career level. Of the final 35 interviews, 30 were conducted face-to-face and five were conducted online. Considering disciplinary background and gender, the numbers are balanced.Footnote 2 The interviews were conducted in Swedish or English and lasted between 90 and 140 minutes. All interviews were recorded and fully transcribed. Informed consent was obtained before each interview, ensuring the respondents about voluntary participation and anonymity. Therefore, some details have been amended slightly or left out of the empirical sections. All names are assigned pseudonyms.

The interviews had a reflexive-biographical character and were conducted across three sections. I began with a set of in-depth questions about the respondents’ individual trajectories, starting with their first fascination with research and the unfolding of their careers. Second, I asked about their current situation, focusing on their practical engagements and the contexts in which these are embedded. Third, I asked about the respondents’ future hopes and dreams, what they ought to do in order to succeed within their field, and what kind of futures were communicated to them by others. Across these sections, the interviews were constructed to explore how the respondents acknowledged or claimed certain standards of evaluation while distancing themselves from or ignoring others. I continuously “ethnographized” the interviews (Pugh 2013), eliciting talk about specific situations and examples of when evaluative standards come into play. Rather than revealing “objective” life courses, the aim of using reflexive-biographical interviews was to shed light on scholars’ biographical work; that is, how they perceive and make sense of their situation and how they relate to it (Sigl 2016). Much of these narratives revolved around navigating the institutional demands of project-based careers.

For theories pointing to the social construction of realities as perceived and understood by actors, language is central. Through their choice of words and gestures, actors define situations, accomplish social actions, and perform identities. Hence, “language constitutes the world(s) it purports merely to describe” and “can be studied in terms of what it does [..] for people and situations” (Scott 2015: 80). Following this line of reasoning, the analysis of the respondents’ biographical work and their narratives about themselves and their careers focused on identifying features of talk that indicate the frames through which they viewed their world. Given the emphasis on projects and project funding in structuring their day-to-day activities and how they made sense of which expectations are applicable in the context of being an early career academic, I began by coding instances in which respondents talked about the significance of projects. Whereas this involved specific practices (such as writing grant applications and conducting project-based research), situations (for example, when receiving a grant or when failing to), and structures (of the project format, etc.), it also included more general accounts of working as a fixed-term scholar and adjusting to career demands. Indeed, the competition for project positions and project funding was constantly linked to the competition for prestige and future employment positions. Finally, I considered variations in the sample depending on contextual factors such as disciplinary background, workplace, and academic age.Footnote 3

The coding procedure allowed me to analyze how the meanings respondents attributed to themselves and their practices were shaped by projectification; that is, how they depended on the project frame that was put around them. While the narratives entailed different attempts to align with such a frame, they also involved experiences of conflicts and contradictions, opening up possibilities for negotiating its normative meanings.

The Project Frame

During the interviews, early career academics in political sciences and history tended to highlight two interpretive orientations according to which they made sense of their current situation: competition and delivery. Together, these form what I call the project frame. Deeply intertwined in shaping scholars’ understanding of career structures and their social identity as fixed-term scholars, competition primarily concerned meanings attributed to social relations and status, whereas delivery mainly involved meanings attributed to research practices.

Competition and Status

In both disciplines, the respondents talked at length about their frequent job and grant market participation. About to enter the final year of her postdoc position, Steph (H1) explained how the “the life of a postdoc is all about competing for resources that will enable you to stay a couple more years in academia, getting the chance to strengthen your CV before applying again.” Similarly, Eric stated:

Since the completion of my PhD, everything is about projects and the competition involved. Coming up with projects, writing project applications, learning how to compete for project funding. And if not getting any money, work on someone else’s project and be better prepared the next time. (Eric, PS2)

Across the interviews, respondents continuously talked about their situation as characterized by competition. From the perspective of project-based careers, almost everything seemed to concern competition and whether or not they would be able to handle it. Such a frame defines academia as a state of rivalry, pushing early career academics to constantly think about how to increase their competitive performance by strengthening their CV. Indeed, many respondents described entering the postdoc phase as adapting to a competitive logic according to which “you can always do more and be better” (Amy, H2).

Competing successfully for project funding was pictured as the main, and sometimes only, way to build an academic career. While the aspect of securing an income was mentioned as important from a private point of view, career-making revolved around the symbolic status of project funding. Consider this quote from an early career academic in political science who had spent several years at the early career level:

Today, research is carried out in projects. Having ongoing funded projects is therefore extremely important. I would say that it’s the main factor deciding who you are at the department. Your role, how you’re perceived by others. […] When I got my first grant, I became someone here. I became a researcher; I was someone to count on. (Peter, PS1)

According to Peter, obtaining project funding shapes the identity and worth of people at his workplace. As a status trait, it serves as a symbolic attribute of success separating winners from losers and establishing who may rightfully claim the identity of a researcher. Whereas previous studies have shown that the move towards competitive project funding changes how academics think about who has the right to research time (Franssen and de Rijcke 2019), my findings suggest that the normative meanings established by the project frame more deeply change how research, as a legitimate and recognized practice, symbolically exists. For example, William (H3) stated that “if it’s not a funded project, it just feels like it’s something I do in my spare time, it’s not real in the same sense.” Nedeva (PS2) supported this view when she said that securing funding for a project “makes it recognizable to others. […] You have survived the competition and now people expect you to deliver. If you talk about projects without funding, people tend to not take you very seriously.”

In general, the symbolic value of projects relied upon a strong hierarchization between research and teaching, representing two very different career paths. According to Thomas (H1), “it’s about positive and negative circles. As soon as you get a grant, you can publish, get citations, apply for more money. All the things you struggle with when stuck teaching.” Furthermore, the function of grants as a distinction was supported by various organizational procedures which effectively anchored the project frame (Goffman 1974: 247 − 51). This involved pedagogical activities, such as seminars and lectures, aimed at educating junior scholars in the art of getting funded, as well as different kinds of ceremonial rituals. For example, Philip (PS2) told me about the pressure he felt due to the custom of “funding cake” at the department, rendering his “own work as a teacher, and that of others, invisible, worth nothing […] we would never celebrate teaching like that.” Likewise, Maria emphasized that grants equal visibility and recognition:

It’s something that is communicated very clearly, from the head of department and others with influence. It’s all about getting grants. […] As soon as someone receives money for a project, everybody gets an email about it. These emails, they sort of state that this is success, this is what counts. And of course, everybody wants to be a name that is mentioned in those emails, getting everybody’s attention… So yeah, money is important, very important. Because people tend not to know how much you publish and they certainly don’t know what your research is about. But everybody knows if you got funding or not. (Maria, PS1)

These mundane ceremonial rituals were mentioned by a vast majority of the respondents, especially the emailing routine, and were referred to as shared signs of success and recognition shaping the everyday talk and interactions at the departments. In this regard, the project frame entails a narrow definition of what constitutes worth at the early career stage. This involves a strong hierarchization between working tasks and academic roles, based on a status order of winners and losers. Certainly, what makes this frame so dominant is the fact that navigating these rules of recognition is highly emotional, including positive feelings of pride, self-worth, and belonging among those who succeed and negative feelings of ignorance and unfairness among those who fail. While some respondents expressed feelings of envy or bitterness, they generally emphasized the importance of controlling negative emotions and being polite towards others. Following Bloch (2012: 41), friendliness is “a necessary strategy given the particular structure of academia,” especially if “one’s position is insecure.” Hence, navigating project-based careers entails scholars pursuing a ‘politics of friendliness’ in which emotions are managed and expressed in certain ways (see also Nästesjö 2023).

Delivery and Pace

Respondents in both disciplines acknowledged the symbolic power of projects and how they framed academic life as competition. Additionally, their understandings of their identities and research practices referred more specifically to the socio-temporal structures of projects. In virtually every interview, the ‘funding circle’ was a recurrent topic, referring to the cycle of publications-grant-data-publications-citations needed in order to sustain a research-intensive career; or indeed, sustain an academic career at all. In this way, the principles of delivery and pace were consistently evoked as junior scholars made sense of what was expected of them. Reflecting upon his time as a postdoctoral researcher, Thomas stated:

Thomas (H1): Working in these temporary projects, it’s all about being able to get things out there. When I first got funding, it was a three-year project, I said to myself that I have to make this count.

Jonatan: What did that mean to you, “make this count”?

Thomas (H1): Frankly, it meant getting as many peer-reviewed articles published as possible. It sounds bad, I know. But that was how I made sense of it. Just trying to get things out there.

Similarly, Anna talked about the importance of “keeping up the pace” and to avoid “working on projects that won’t be profitable for a long time.” When asked if she could be more specific, she stated:

I need to prioritize some sort of certainty that a project pays off. I need publications. That’s just how it is. Therefore, I try to avoid being part of projects or collaborations that are slow and where the outcomes are uncertain. […] At the end of the day, working as a postdoc is about adding things to your CV, showing others that you can deliver. Because in one to two years, I am up against all these great scholars again. (Anna, PS1)

The narratives of Anna and Thomas revolve around a specific type of project performance relating to career demands shaped by project time. Accordingly, their research practices and academic identities must be adjusted to the individual need for visible and measurable results, to be used as ‘capital’ next time there is a funding call or a position available. Hence, by privileging competition and delivery, the project frame feeds into a “dominant regime of valuation” as well as “one of accumulation” (Falkenberg 2021: 426). Nevertheless, ensuring the accumulation of academic capital involves aligning with the project frame. This will be the focus of the next section.

Aligning with the Project Frame

Respondents from both disciplines jointly described projectification as an epistemic condition according to which they made adjustments in their research. Given the previous emphasis on strengthening one’s competitive performance by delivering measurable outputs, these adjustments mainly concerned the reduction of risk and to focus on publishing peer-reviewed journal articles. For example, in order to “make things count,” Thomas (H1) explained how the need to “get things out there […] meant playing it safe, trying not to take too many risks.” In practice, he “recognized how many papers might come out of this rather limited empirical material” and then he “just started working.” In a similar fashion, Nedeva described how “the need to quickly demonstrate results” made it obvious that “books are a bad investment.” While this privileged the short journal article as publication format, she also described how it was tailoring her research process:

Looking back, it has pushed me towards questions that can be answered by the existing methods and the existing data quickly and still be publishable in a good journal. In that sense, it affects what questions I work with, how I work with them, and how I present the results. Because the publication comes first, something has to come out of it. And after a while, you sort of learn that, ok, this is too explorative, engaging with too big questions, or this is too risky, no journal cares about this. (Nedeva, PS2)

The accounts of Nedeva and Thomas are illustrative examples of how early career academics attempt to align their research practices in accordance with the project frame. These attempts concern what types of research questions to pursue, what methods to use, and decisions about publication formats. Generally, these findings are in line with evidence from studies of how junior scholars in, for example, economics (Steffy and Langfeldt 2022) and the life sciences (Müller 2014; Sigl 2016) cope with the demands of project-based careers. However, practices of frame alignment also varied among the respondents. In the following, I provide two examples based on disciplinary background and academic age.

Disciplinary Conflicts and Epistemic Alignment

As argued by Laudel (2017: 365), research in history is highly individualized, relying upon “personal perspectives on the state of the art and empirical material.” Because there is usually no division of labor and the cost of equipment is low, the most important requirements concern time. In this regard, the same epistemic behavior that was incentivized by the project frame challenged certain conventions and ideals rooted in the discipline. Talking about the temporal structures of projects, Gary stated:

A high ideal within our discipline is to carry out large and detailed archival work, where you really dig deep, going through a lot of source material. That’s what a really good historian does. But the way research is funded today, in these small, short projects, there’s no possibility to live up to that standard. No way. (Gary, H2)

Similar tensions between project time and disciplinary conventions were a recurrent topic in the interviews with junior scholars in history and point to how frame alignment is an ongoing and contingent activity. When subject to conflict, action is necessary. Within the history field, two strategic responses are noticeable. First, respondents who had earned several grants of different sizes described how they started to modify the ‘funding circle’ by collecting data before applying for funding; that is, collecting data for project B when working on project A. Being an example of what Virtová and Vostal (2021: 365–367) call “temporal stretching,” in which “the research project and the research process do not share the same temporal window,” it is a tactical repertoire also used in political science. Yet, while political scientists mainly used it as a strategy to secure continuity between projects, historians specifically tried to manufacture the temporal structures of projects in a way that would enable them to carry out extensive archival work while securing a steady flow of publications. In part, this was made possible by the heterogenous funding landscape of the Swedish humanities, consisting of a relatively high number of smaller, short-term scholarships or stipends which can be combined with grants of different sizes.

Second, to meet the demands of productivity, some respondents in history described how they had started to ‘team up,’ beginning to co-author journal articles and book chapters. Working in a discipline in which time pressure usually cannot be compensated for by employing research personnel (Laudel 2017), teaming up on specific publications aligns with the temporal structures of project-based research. However, because of the highly individualized character of the history field, these respondents often commented on the uncertainty of the routines for and the valuation of such publications:

There is little to no experience at the department of working in joint projects or publishing together. That gives us a lot of freedom I think and I kind of like that. However, it also means that no one really knows how it will be evaluated in the future. Other disciplines, they seem to have very clear rules for this, first and last author and all that. But in history, does it matter if your name is first, second, third, or last? I don’t know… There is no knowledge or established praxis. (Susie, H3)

In contrast to history, political science is a field in which co-authoring is a well-established practice and the level of interdependency between scholars is generally higher. This is especially evident in quantitative-based and method-driven parts of the discipline (Lamont 2009: 95–100). For young political scientists working in collaborative research groups with such a focus, the dynamics of frame alignment differed. Relying on project leaders to bring in funding to the group, these respondents described how their individual opportunities to accumulate worth heavily depended on how well they matched up with the research focus of dominant agents at the department. Talking about a particularly successful research group at his workplace, Victor (PS2) explained how he, during his PhD education, “got a sense of what questions and methods were highly valued” and that he therefore tried “to focus on working in that specific area of research.” Likewise, Rachel stated:

My future in research depends very much on being part of this group. It gives me access to data, expertise, and collaborations on publications and stuff like that. So of course, I do my best to fit in and make a valuable contribution. I really want to stay. (Rachel, PS2)

As argued by Franssen and de Rijcke 2019, one way in which project funding shapes the social structures of academia is by outsourcing epistemic authority to project leaders, and indirectly, to funding bodies. When competitive resources are concentrated over time, the demands on researchers and groups to comply with certain epistemic and organizational standards increase. Thus, what comes across in the statements from Victor and Rachel is that aligning with the project frame equals aligning with the epistemic focus of successful researchers at their department. Understood as a way of navigating project-based careers, it signifies not only a major difference between the two disciplines, but also the two political science departments, in which the organizational structures of PS2 to a greater extent were shaped by collaborative research groups or centers having accumulated competitive funding for a long period of time.

Academic Age and Trajectoral Thinking

In the section above, aligning with the project frame involves attempts in which scholars seek to ensure accumulation of academic capital to strengthen their competitive capability. Yet, what counts as CV improvements is not self-evident. Rather, it gradually changes as junior scholars become more ‘senior’ postdocs. For example, at the same time as political scientists working in large collaborative research projects talked about the significance of their group membership, they also mentioned the importance of ‘splitting up’ in order to demonstrate independence. One example is Helena (PS2), who had been working in the same research group since she was a doctoral student and had never obtained funding herself. While she stated that “my biggest challenge right now is to start publishing on my own rather than collaborating on every paper, because that is needed in order to have the chance to succeed within the discipline,” she underlined that the informal rules of the group did not make it easy:

I’m funded within the center and that makes my work more collaborative in nature. And because of that, it is hard to start writing and publishing on my own. Both because it’s fun and intellectually rewarding to collaborate, and it sure gives me the possibility to be more productive, but it’s also hard because it’s just how you work here, collaborating is the norm. I don’t want to break the rules and be viewed as keeping things to myself. (Helena, PS2)

These aspects of group membership were linked to more formal aspects of working in joint projects:

It’s also a question of authority and ownership. I mean, can I publish on my own using the data we have collected within the group? I’m not sure if that would be OK. (Helena, PS2)

What Helena describes is how the dynamics between disciplinary conventions and academic age shape how institutional career demands are experienced. In order to earn recognition and advance in her career, she needs to show progress, but what counts as progress depends on her social position and research biography. For political scientists working in joint projects, this involved issues of independence, both in terms of publishing and competing successfully for grant money – something that was not always easily achieved due to organizational constraints. Among the respondents who had spent several years at the early career level, it also entailed navigating a game of status in which they sought to obtain more prestigious grants. While both historians and political scientists agreed that the most important distinction between junior scholars was if they had grant money or not, they were aware that not all funding is the same. Amy (H2) told me that “there is fancy money and there is ugly money,” exemplifying with a distinction between a local postdoc grant which she had received at the beginning of her postdoc career and the high-status international postdoc grant from the Swedish Research Council. Similarly, as Peter talked about how to improve his current position and to increase his chances of obtaining stable employment, he stated:

I feel like the bar is constantly rising. As I said before, I’ve been quite successful in obtaining funding and I’ve published a lot. But to take the next step, to really make a difference, then it would have to be an ERC grant or something like that. You know, something that says: wow! (Peter, PS1)

These findings echo previous studies on Swedish academia which demonstrate that individual funding sources are ranked hierarchically by scholars, for example in terms of their (inter)disciplinary character (Müller and Kaltenbrunner 2019) or the level of competition and experts involved in grant evaluations (Edlund 2024). In addition, the narratives of Peter and Helena bear evidence of how such status distinctions become entangled in a specific kind of ‘trajectoral thinking’; that is, a mode of thinking characterized by linear and proportional progress (Hammarfelt et al. 2020). Indeed, the structures of project-based careers invite such ‘trajectionism’ (Nästesjö 2023), and helps junior scholars to make sense of what is expected of them. At the same time, the mismatch between an ideal career trajectory and the lived lives of scholars spurs anxieties and feelings of inadequacy.

Keying the Project Frame

Privileging a narrow regime of valuation and accumulation, the project frame defines academic work as a state of rivalry, pushing fixed-term scholars towards entrepreneurial behavior (Franssen and de Rijcke 2019) and an entrepreneurial self (Loveday 2018; Müller 2014). In this regard, the project frame not only yield career incentives but also contradictions and tensions. In many of the accounts above, there is an underlying frustration among the respondents of constantly having to compete with each other and to compromise in their research. This provokes identity conflicts and value struggles. In the final empirical section, I will focus specifically on how early career academics in political science and history deal with such tensions by keying the project frame; that is, by altering its normative meanings to something patterned that creates multiple layers of interpretation (Goffman 1974: 45).

Identification and Luck

The first tension to consider is that of social bonds within the project frame. While the principles of competition and delivery provide a highly individualistic career script recognized by the respondents, they commonly described it as damaging for peer-to-peer relationships. As newcomers, junior scholars depend on each other’s help, for example, in learning how to apply for funding and commenting on each other’s applications and ongoing research projects. They may also offer each other important support in difficult times. Yet, when continuously engaging in competitions for limited resources, junior scholars are framed – both structurally and interactionally – as competitors rather than helpful colleagues. To many of the respondents, this represented a major conflict in their daily lives, potentially leading to ambiguity or hostility.

To curb their competitive relationship, early career academics in political science and history frequently talked about themselves as a particularly vulnerable group in the science system. If such a narrative was shared intersubjectively, it modified the experience of competition by tying junior scholars together. Still, differentiating themselves from others was often not enough. To alter the meaning of competition within the group of early career academics, respondents also reframed the outcome of grant applications as a matter of luck. Describing how he and his colleagues had been “helping each other out for years,” Thomas concluded that:

Nobody knows who will receive funding, the competition is ridiculous. It’s like a lottery, nobody knows and no one can influence who will get money in the end. So yeah, we’re in the same boat. Might as well help each other. (Thomas, H1)

Likewise, Douglas talked at length about the emotionally charged situation project funding creates and how to handle it:

Douglas (PS1): It’s sensitive, talking about who got money and who didn’t. But I think we’re rather good at sticking together, we don’t want it to take over too much. In a negative way, I mean.

Jonatan: How do you do that; can you give an example?

Douglas (PS1): Yeah sure. Ehm… When I got my recent grant, everybody congratulated me and stuff like that. I said thanks and that I was proud of it, but it’s like, I was lucky. Luck plays an important role here. Yes, it’ s a competition, yes you need to have a strong application, but it’s also a matter of coincidence. Who sits in these panels and stuff like that. And if we acknowledge that it becomes easier.

According to Douglas, this let him and his peers create conditions for cooperation:

Douglas (PS1): We help each other out, in informal meetings and at seminars and stuff. […] When you think about it, it’s a fucking strange situation, sitting there, trying to strengthen the application of your competitor. But it’s like, you give and you receive. That’s the rule. One time, you help someone and the next time you’re the one getting help.

Jonatan: Ok, but what if you’re not helping others?

Douglas (PS1): Then you become kind of isolated, you’re not really part of the group. […] I feel like those who don’t contribute to the work of others are also those who usually keep things for themselves, you know, as a competitive advantage, and that’s like, it’s not really fair. People don’t like that. You become isolated.

Framing the outcome of project funding as luck, while at the same time altering the meaning of competition through identification, helps early career academics to establish a working consensus according to which they can simultaneously compete and support each other. As is evident in the above quotations, this involves junior scholars adhering to certain informal rules on how earning the help of colleagues depends on one’s own investment in commenting on the work of others. While such moral commitment does not eliminate or erase conflict stemming from the competitive structures of project-based careers, it provides strategies for temporarily resolving it through the negotiation of action based on common values. Indeed, conceptualized as acts of keying, the project frame is not broken or replaced, but laminated (Goffman 1974: 45). At the same time, these efforts to manage the potential disruptions of social bonds within the project frame convey important cracks in this particular way of framing academic work and careers. These cracks not only constitute interactional vulnerabilities but also interactional resources by which early career academics negotiate their normative meanings. This is because criticized elements of the project frame become sites of boundary-making, opening up for rethinking situations and what is expected of those involved (Tavory and Fine 2020). In this process, alternative identity positions and a sense of (weak) community are envisioned.

Imagined Futures and Slowing Down

The second tension to consider concerns the dynamics between research practices and a sense of self-worth. Respondents in both disciplines frequently commented critically upon the regime of valuation structured by a projectified academic landscape. In particular, they described the feeling of unease when adapting their research practices to such a narrow script of success. When probed about their own aspirations and notions of success, the respondents therefore envisioned futures that combined tenets of hard work and adaptation to institutional demands with wider definitions of worth. This would let them key the project frame, transforming its normative meanings and their own subjective involvement. For example, when asked to reflect upon what is needed of him in order to succeed in academia, John stated:

It’s a struggle, of course. It feels like I need to do as much as possible but I have no idea what’s enough. […] At times, I feel like such a typical postdoc, absorbed by this instrumental mindset. […] But it’s like, ok, if I do this properly, if I can deliver results now, then I will get the chance to do it differently in the future. Slow down, focus on the things I really like the most. (John, H2)

According to John, short-term contracts and the constant competition on the basis of individual merits create immense pressure to achieve and maintain a high pace while delivering measurable results. However, nobody seems to know what is good enough. To deal with the tensions involved in this process, John defines his current situation as temporary and the future as different. In this way, he connects his short- and long-term goals in academia while at the same time creating a moral distance between them. This lets him balance between adapting to instrumental career demands and validating his sense of self.

Alternative ways of visualizing and conceptualizing the future were a recurrent topic in the interviews. Still, it was most widespread among the group of respondents who had spent several years at the early career level. These scholars felt exhausted by pressures to achieve narrow definitions of success and the competitive attitude associated with it. When talking about the flexibility and pace needed in order to work on a series of short-term contracts, Amy (H2) said, “I have done this for many years now and I feel exhausted. If I am going to continue working as an academic, in the long run, I need to start doing things differently.” In a similar vein, Peter elaborated upon his future life in research:

I’ve been part of this postdoc race for a long time, I have published a lot and been able to obtain funding for some projects. You know, I have done the right things, I think… So recently, I’ve felt like it’s time to slow down a bit, try to focus more on impact than on quantity. I mean, If I’m honest, I’m not very proud of everything I’ve done in recent years and I would really like to change focus a bit. (Peter, PS1)

Often, these imagined futures had certain epistemic aspects:

I feel like, fuck this. I’ve done these obligatory postdoc publications and now I can slow down. Before, I had two, three, four articles under review almost all the time, but now I have one. So, it’s about slowing down and to increase the quality. Involve more empirical work, be more systematic in my approach. Instead of dividing things I want to think things together, you know, synthesize. […] I want to feel proud about my work. (Peter, PS1)

As we learn from other studies, imagined futures are not about actualizing what is yet to come in any objective sense (Mische 2009). Instead, future-narrating is a practice of the present; a kind of problem-solving embedded in structures inviting people to imagine different futures at specific moments (Zilberstein et al. 2023). In the above statements, imagined futures are narrated when scholars face certain conflicts or contradictions when navigating project-based careers. As a result of having spent several years at the postdoc level, Amy and Peter grapple with tensions between having to adapt their research practices to a logic based on pace and productivity, and to engage with research in a way that can maintain a sense of aspiration and self-worth. For Peter, this involves a conflict between what we may call ‘personal research projects’ and ‘the projectification of research,’ representing two very different temporal windows and modes of thinking about research.

Conceptualized as acts of keying, imagining futures may be regarded as an attempt to negotiate the normative meanings of the project frame. By acting upon the cracks of this particular way of framing academic work and careers, they are part of mobilizing alternative scripts of success and worth which can validate scholars’ sense of self. However, neither imagined futures nor a desirable sense of self are to be understood as strictly an individual endeavor. Instead, they are linked to culturally shaped expectations and presumptions (Tavory and Fine 2020). Given that scholars are accountable to multiple regimes of worth (Rushforth et al. 2019), keying the project frame is as much about justifying self-worth as it is about balancing the contradictions of recognition and reward in academic life (Nästesjö 2023).

Discussion

In this article, I have explored how early career academics experience and navigate project-based careers. Contrary to much earlier research, the study includes two social sciences and humanities disciplines, namely, political science and history in Sweden. Findings reveal that respondents in both disciplines referred to competition and delivery in order to make sense of their current situation, forming what I call the project frame. This frame feeds into a dominant regime of valuation and accumulation (Falkenberg 2021; Fochler et al. 2016), and had an impact on respondents’ research practices and their social identity as early career academic. Not least, this was evident in a strong focus on minimizing risk and increasing productivity within limited timeframes. In this regard, there are similarities between how junior scholars across different disciplinary settings make sense of and cope with project-based careers (Müller 2014; Sigl 2016; Steffy and Langfeldt 2022). Yet, whereas the content of the project frame was well-defined across the interview sample, attempts to align with it varied. For instance, the temporal structures of projects challenged certain disciplinary conventions and definitions of worth in the field of history. At the same time, it opened up for new collective epistemic practices, evident in historians beginning to ‘team up’ on publications and projects, aiming to speed up the research process. Interestingly, under certain circumstances, this logic was reversed in political science. Among political scientists who had worked in collaborative research groups throughout their careers, the need to ‘split up’ in order to show independence was emphasized – both in terms of publishing and obtaining grants. Additionally, such ‘trajectoral thinking’ was common among more ‘senior’ postdocs who actively ranked the status of different grants, describing career advancement as dependent on them earning more prestigious ones.

Previous research on projectification has pointed to its standardizing or colonizing effects (Felt 2016), arguing that “disciplinary differences have become increasingly blurred” (Ylijoki 2016: 8). By focusing on the dynamics between frame content and frame alignment, this article compliments such picture by showing how the organization of research and careers around the project format means both convergence and divergence between political science and history. Importantly, the findings stress that the interaction between disciplinary conventions and academic age are important to consider when studying how junior scholars navigate institutional demands structured by projectification.

Influencing the social (Franssen and de Rijcke 2019) and temporal (Vostal 2016) structures of academia, the rise of project funding and the evaluations produced in funding decisions have been described as “status-bestowing events” (Edlund and Lammi 2022), providing long-lasting status advantages for individual scholars (Bloch et al. 2014). By adopting a frame analytic approach, the present study adds another layer of understanding, focusing attention to the symbolic meanings of projects and project funding in the everyday life of early career academics. Respondents in both disciplines described project funding as a distinction. In addition to monetary value and the certification that their research is better than others, they thus emphasized the symbolic value of project funding for being recognized as a full-worthy member of the research community. Such framing was anchored by pedagogical activities like lectures and seminars, as well as ceremonial rituals such as 'the funding cake’ and emailing routines. Together, these organizational routines established and confirmed the project frame, functioning as a subtle form of power in academic socialization processes. Understood as a social and cultural process centrally constituted at the level of meaning-making, this is to say that projectification takes place around the creation of shared categories and classifications through which scholars make sense of themselves and the world of early career academics. As a frame, it sorts out people and practices, distributing both material and nonmaterial resources, becoming an integral part of the early career as a distinct “status passage” in academic life (Laudel and Gläser 2008).

Whereas the project frame organizes how early career academics experience career demands, it is not without disruptions or conflicts. Rather, respondents continuously described how this dominant framing of academic work and careers created tensions and frustration among them. In particular, they felt uneasy about having to align with the entrepreneurial and competitive logic enforced by it – both in terms of research practices and identity positions. Indeed, much empirical work on the consequences of projectification focuses on the alignments and misalignments experienced by researchers. However, this article contributes a perspective on how early career academics actually deal with such conflicts by keying the project frame. Drawing upon Goffman (1974: 45), frameworks are keyed when their meanings are transformed into something patterned on them. In this way, frames are laminated, creating multiple layers of interpretation. Two different forms of keying have been identified.

First, to curb their competitive relationship, respondents framed the outcome of project funding as ‘being lucky.’ While attributing success to luck have been interpreted as a lack of agency among fixed-term academics (Loveday 2018) or as evidence of the contingencies shaping both knowledge production and the trajectories of those engaged in it (Davies and Pham 2023), my findings point to a very social form of luck. At a general level, attributing failure and success to luck may be seen as a strategy for managing contradictions within a competitive funding system, where chance and arbitrariness are pivotal (Roumbanis 2017). More specifically, though, emphasizing luck created conditions for identification and cooperation among junior scholars – a kind of moral commitment central to their understanding of their work and their sense of self. To further explore the role played by luck in academia, future research should be attentive to the many ways in which luck might be evoked by scholars and what representations of legitimacy are thereby produced. This does not just involve attempts to alter the meaning of competition. Luck may be used as a strategic resource to justify how scholars qualify for the positions they obtain (see e.g. Ye and Nylander 2021); strategies that are likely to differ depending on the social position of academics as well as gender and class background.

Second, as a response to the narrow script of success privileged by the project frame, respondents drew on imagined futures. This would let them work toward a future in academia, adapting to certain institutional demands of the early career, while committing to wider definitions of worth. This adds to previous analyses of the postdoc period as characterized by a narrowing of valuation regimes toward a single form of academic worth based on high-impact publications and grant money (Fochler et al. 2016; Müller 2014). While such tendencies were present in the respondents’ narratives about what makes a successful academic career, they also critically reflected on the achievability and desirability of the models of the future embedded in such a valuation regime. As a result of having spent several years on early career level, the ‘senior’ postdocs in political science and history grappled with tensions between adapting to short-term career demands and to maintain a sense of long-term aspiration and self-worth. Understood as a conflict between ‘the projectification of research’ and ‘personal research projects,’ imagined futures thus become important cultural tools for scholars to transcend the temporal structures of project-based careers and to envision research as a broader endeavor or commitment. Paying more attention to how scholars draw on imagined futures in order to define their identities, aspirations, and goals could broaden our understanding of scholars’ ability to keep several definitions of worth in play and how this is both a practical and a moral project. To better understand how such abilities are shaped by disciplinary cultures and the social position of scholars is critical for advancing our knowledge of the interplay between valuation, temporality, and identity in contemporary academia.

Overall, the study aligns with recent works on academic socialization focusing on how junior scholars navigate the multiple and sometimes contradictory demands of academic careers. Rather than signs of “incoherence” (Hakala 2009), scholars’ diverse response to career pressures are here conceptualized as a kind of pragmatic problem solving. For example, Steffy and Langfeldt (2022) have shown that skillfully drawing on cultural repertoires help junior economists to respond to certain challenges within their field. Similarly, Ylijoki and Henriksson (2017) identified a diverse set of collective career stories available to junior scholars when making sense of how to build an academic career. Still, my findings offer an important extension by pointing out the potentially productive aspects of tensions or conflicts. Forcing early career academics to rethink situations and their own practical engagements – including who they are and who they wish to become – tensions and conflicts serve as critical moments in socialization processes. They are crucial for scholars’ personal research projects, their sense of self, and the building of relationships. This is evident in the empirical examples of keying, in which rejected or criticized elements of the project frame become sites of boundary-making, defining and envisioning alternative identity positions and scripts of success. In particular, these examples stress the importance of morality as a site of and motivation for pragmatic problem-solving, as junior scholars deal with tensions arising from balancing career demands, individual aspirations, and competing conceptions of worth.

Data Availability

Not applicable.

Notes

Such as the department’s website, personal websites, Google Scholar, and network platforms such as ResearchGate and LinkedIn.

Political Science: 11 male and 7 female. History: 9 male and 8 female.

Although not included in this article, I also considered variations in terms of class and gender.

References

Archer, Louise. 2008. Younger academics’ constructions of ‘authenticity’, ‘success’ and professional identity. Studies in Higher Education 33(4): 385–403.

Benner, Mats. 2016. Karriärstrukturen vid svenska universitet och högskolor - en historik. In Trygghet och Attraktivitet - En Forskarkarriär För Framtiden. SOU 29: 155–168.

Bloch, Charlotte. 2012. Passion and Paranoia. Emotions and the Culture of Emotion in Academia. Routledge.

Bloch, Carter, Ebbe Graversen Krogh, and Heidi Skovgaard Pedersen. 2014. Competitive research grants and their impact on career performance. Minerva 52(1): 77–96.

Cannizzo, Fabian. 2018. Tactical evaluations: Everyday neoliberalism in academia. Journal of Sociology 54(1): 77–91.

Davies, Sarah R., and Bao-Chau Pham. 2023. Luck and the ‘situations’ of research. Social Studies of Science 53(2): 287–299.

Edlund, Peter. 2024. More than euros: Exploring the construction of project grants as prizes and consolations. Minerva 62(1): 1–23

Edlund, Peter, and Inti Lammi. 2022. Stress-inducing and anxiety-ridden: A practice-based approach to the construction of status-bestowing evaluations in research funding. Minerva 60: 397–418.

Falkenberg, Ruth. 2021. Re-invent Yourself! How demands for innovativeness reshape epistemic practices. Minerva 59: 423–444.

Felt, Ulrike. 2016. Of timescapes and knowledgescapes: Retiming research and higher education. In New Languages and Landscapes of Higher Education, eds. Peter Scott, Jim Gallacher, and Gareth Parry, 129–148. Oxford University Press.

Fochler, Maximilian, Ulrike Felt, and Ruth Müller. 2016. Unsustainable growth, hyper-competition, and worth in life science research: Narrowing evaluative repertoires in doctoral and postdoctoral scientists’ work and lives. Minerva 54(2): 175–200.

Franssen, Thomas, and Sarah de Rijcke. 2019. The rise of project funding and its effect on the social structure of academia. In The Social Structure of Global Academia, eds. Fabian Cannizzo and Nick Osbaldiston, 144–161. Routledge.

Frølich, Nicoline, Kaja Wendt, Ingvild Reymert, Silje Maria Tellmann, Mari Elken, and Svein Kyvik. 2018. Academic career structures in Europe. Perspectives from Norway, Denmark, Sweden, Finland, the Netherlands, Austria and the UK. 2018: 4. Nordic Institute for Studies in Innovation, Research and Education (NIFU).

Gill, Rosalind. 2016. Breaking the silence: The hidden injuries of neo-liberal academia. Feministische Studien 34(1): 39–55.

Goffman, Erving. 1974. Frame Analysis: An Essay in the Organization of Experience. Harvard University Press.

Haddow, Gaby, and Björn Hammarfelt. 2019. Early career academics and evaluative metrics: Ambivalence, resistance and strategies. In The Social Structure of Global Academia, eds. Fabian Cannizzo and Nick Osbaldiston, 125–143. Routledge.

Hammarfelt, Björn, and Sarah de Rijcke. 2015. Accountability in context: Effects of research evaluation systems on publication practices, disciplinary norms and individual working routines in the faculty of Arts at Uppsala University. Research Evaluation 24(1): 63–77.

Hammarfelt, Björn, Alexander Rushforth, and Sarah de Rijcke. 2020. Temporality in Academic Evaluation: ‘Trajectoral Thinking in the Assessment of Biomedical Researchers. Valuation Studies 7(1): 33–63.

Hakala, Johanna. 2009. The Future of the Academic Calling? Junior Researchers in the Entrepreneurial University. Higher Education 57(2): 173–190.

Herschberg, Channah, Yvonne Benschop, and Marieke van den Brink. 2018. Precarious postdocs: A comparative study on recruitment and selection of early-career researchers. Scandinavian Journal of Management 34(4): 303–310.

Krog Lind, Jonas, Hege Hernes, Kirsi Pulkikinen, and Johan Söderlind. External research funding and authority relations. In Reforms, Organizational Change and Performance in Higher Education: A Comparative Account from the Nordic Countries, eds. Rómulo Pinheiro, Lars Geschwind, Hanne Foss Hansen, and Kirsi Pulkkinen, 145–180. Palgrave Macmillan.

Lamont, Michèle. 2009. How Professors Think: Inside the Curios World of Academic Judgment. Harvard University Press.

Laudel, Grit. 2017. How do National Career Systems Promote or Hinder the Emergence of New Research Lines? Minerva 55: 341–369.

Laudel, Grit, and Jochen Gläser. 2008. From apprentice to colleague: The metamorphosis of early career researchers. Higher Education 55(3): 387–406.

Loveday, Vik. 2018. Luck, chance, and happenstance? Perceptions of success and failure amongst fixed-term academic staff in UK higher education. The British Journal of Sociology 69(3): 758–775.

Mische, Ann. 2009. Projects and Possibilities: Researching Futures in Action. Sociological Forum 24(3): 694–704.

Müller, Ruth. 2012. Collaborating in Life Science Research Groups: The Question of Authorship. Higher Education Policy 25(3): 289–311.

Müller, Ruth. 2014. Racing for What? Anticipation and Acceleration in the Work and Career Practices of Academic Life Science Postdocs. Forum: Qualitative Social Research 15(3): 162–184.

Müller, Ruth, and Wolfgang Kaltenbrunner. 2019. Re-disciplining academic careers? Interdisciplinary practice and career development in a Swedish environmental sciences research center. Minerva 57: 479–499.

Müller, Ruth and Sarah de Rijcke. 2018. Thinking with indicators. Exploring the epistemic impacts of academic performance indicators in the life sciences. Research Evaluation 27(3): 283–283.

Nästesjö, Jonatan. 2021. Navigating Uncertainty: Early Career Academics and Practices of Appraisal Devices. Minerva 59(2): 237–259.

Nästesjö, Jonatan. 2023. Managing the rules of recognition: how early career academics negotiate career scripts through identity work. Studies in Higher Education 48(4): 657–669.

Persson, Anders. 2018. Framing Social Interaction: Continuities and Cracks in Goffman’s Frame Analysis. Routledge.

Pugh, Allison J. 2013. What good are interviews for thinking about culture? Demystifying interpretive analysis. American Journal of Cultural Sociology 1(1): 42–68.

Roumbanis, Lambros. 2017. Academic judgments under uncertainty: A study of collective anchoring effects in Swedish research council panel groups. Social Studies of Science 47(1): 95–116.

Roumbanis, Lambros. 2019. Symbolic violence in academic life: A study on how junior scholars are educated in the art of getting funded. Minerva 57(2): 197–218.

Rushforth, Alexander, Thomas Franssen, and Sarah de Rijcke. 2019. Portfolios of worth: Capitalizing on basic and clinical problems in biomedical research groups. Science, Technology, & Human Values 44(2): 209–236.

Salö, Linus. 2017. The Sociolinguistics of Academic Publishing: Language and the Practices of Homo Academicus. Palgrave Macmillan.

Scott, Susie. 2015. Negotiating Identity: Symbolic Interactionist Approaches to Social Identity. Polity.

Sigl, Lisa. 2016. On the tacit governance of research by uncertainty: How early stage researchers contribute to the governance of life science research. Science, Technology, & Human Values 41(3): 347–374.

Steffy, Kody, and Liv Langfeldt. 2022. Research as discovery or delivery? Exploring the implications of cultural repertoires and career demands for junior economists’ research practices. Higher Education 86: 317–332.

Swedish Research Council. 2015. Forskningens Framtid! Karriärstruktur Och Karriärvägar i Högskolan. Vetenskapsrådets Rapporter.

Tavory, Ido, and Gary Alan Fine. 2020. Disruption and the theory of the interaction order. Theory and Society 49(3): 365–385.

Virtová, Tereza, and Filip Vostal. 2021. Project work strategies in fusion research. Time & Society 30(3): 355–378.

Vostal, Filip. 2016. Accelerating Academia: The Changing Structure of Academic Time. Palgrave Macmillan.

Ye, Rebecca, and Erik Nylander. 2021. Deservedness, humbleness and chance: Conceptualisations of luck and academic success among Singaporean elite students. International Studies in Sociology of Education 30(4): 401–421.

Ylijoki, Oili-Helena. 2016. Projectification and Conflicting Temporalities in Academic Knowledge Production. Theory of Science/Teorie vědy 38(1): 7–26.

Ylijoki, Oili-Helena, and Lea Henriksson. 2017. Tribal, proletarian and entrepreneurial career stories: junior academics as a case in point. Studies in Higher Education 42(7): 1292–1308.

Zerubavel, Eviatar. 1991. The Fine Line: Making Distinctions in Everyday Life. The University of Chicago Press.

Zilberstein, Shira, Michèle Lamont, and Mari Sanchez. 2023. Recreating a plausible future: Combining cultural repertoires in unsettled times. Sociological Science 10(1): 348–373.

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank the respondents for kindly taking the time to talk with me about the world of academia. Additionally, I thank Björn Hammarfelt, Fredrik Åström, Anders Sonesson, Max Persson, Julian Hamann, and Alexander Villiers for their insightful comments on earlier drafts of this paper. Finally, I would like to express my gratitude for the constructive comments provided by the anonymous reviewers.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Lund University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Not applicable.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no Conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nästesjö, J. Between Delivery and Luck: Projectification of Academic Careers and Conflicting Notions of Worth at the Postdoc Level. Minerva (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11024-024-09541-3

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11024-024-09541-3