Abstract

Climate change disproportionately impacts coastal residents in the United States. Existing studies document institutional efforts to adapt to sea level rise through projects like seawalls, beach nourishment, and property acquisitions to protect communities from rising seas. Such studies capture institutional adaptations, but do not include ad hoc adaptations by homeowners impacted by climate change. How are homeowners adapting to climate hazards? This paper analyzes ethnographic and interview data from 100 households in two coastal counties in North Carolina, a state with one of the most climate vulnerable shorelines in the country. This analysis of homeowner response considers ad hoc adaptations along the North Carolina coast. Results show that homeowners recognize climate hazards and regularly adapt on their own within the context of institutionally maintained flood protection infrastructure and transportation access to the places where they live. Residents are aware of and attempt to access support for home adaptations when programs or funds are available to them after disasters and do so with varying levels of success, though the more pervasive adaptations to chronic stress are not supported by government programs or insurance mechanisms. Ad hoc adaptations may provide short-term protection from climate hazards but have questionable long-term efficacy as sea levels rise and storm strength and frequency increases. Leaving communities and households to adapt on their own as chronic climate hazards outpace institutional response exacerbates existing inequalities by relying on residents with different levels of resources and agency to adapt.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

As governments and institutions wrestle with how to both mitigate climate change and manage its effects using development, resilience, and adaptation policies, people are living with the changing climate in their daily lives and adjusting to climate conditions through ad hoc strategies. These individuals shift their habits, routines, and work to accommodate climate conditions, both slow onset and disasters, through everyday adaptations (Castro and Sen 2022). This process occurs within a dialectic of individual ad hoc adaptation actions done independently to one’s home and property and institutional adaptation processes including resilience infrastructure, insurance mechanisms, and funding for disaster recovery.

Though scholars consider the impacts of planned adaptations, individuals’ granular level coping strategies, resilience efforts, and ad hoc adaptations are missing from our understanding of the social effects of climate change. Unlike in areas where planned adaptation hinges on improved infrastructure or coordinated state programs, places without comprehensive climate resilience and adaptation policies leave households to adapt their homes and livelihoods on their own (Adger et al. 2003; Carman and Zint 2020; Smit et al. 2000). This research explores how ad hoc adaptation, individuals’ independent and unplanned adjustments to actual or expected climate conditions, relies on people’s resources to adjust their lives to shifting climate norms.

Communities’ experiences of the changing climate are highly varied (Dunlap and Brulle 2015). Sociologists are captivated by the ways in which individual characteristics, including class, race, gender, and many more, influence people’s exposure to the impacts of climate change in complex ways (Nagel 2015; Pellow 2000). Both disasters and slow-onset environmental stress result in the entrenchment of existing inequality. Those with more resources have greater options for responding and adapting to the changing climate (Siders et al. 2019), and as a result, poor and marginalized communities suffer the most in times of environmental crisis (Dunlap and Brulle 2015; Fussell 2015; Pellow 2000) and during disaster recovery (Gotham and Greenberg 2014; Howell and Elliott 2018). Beyond material inequality, community cohesion and cultural attachment are key determinants in the overall impact of environmental crisis (Bates 2016; Klinenberg 2015) and how communities respond to loss (Elliott 2018).

To better understand how the daily, micro-level climate change experience unfolds, I ask two questions in the paper that follows: first, how are people managing climate change in the absence of comprehensive institutional adaptation efforts? And, second, how are their ad hoc adaptations to climate change reliant on or informed by institutional responses to climate change hazards? I document the ad hoc adaptations of residents in the Outer and Inner Banks region of North Carolina through ethnographic fieldwork and interviews with homeowners in areas with different levels of coastal armoring, floodplain management, and property acquisitions. I find that residents are adapting on their own and have been doing so for decades based on their local knowledge (Geertz 1983). This local knowledge consists of their subjective experiences living with climate risk that informs their risk perceptions and ad hoc adaptation decisions. These decisions are not logical equations of economics, but rather they are about managing daily life despite local climate challenges.

The institutional context in this study area informs decisions to adapt ad hoc in three clear ways. Individuals adapt their homes and properties under the assumption that institutions will provide regular access to their homes through maintained roadways, bridges and ferries as well as flood protections such as dune and levee maintenance along shorelines. In daily life, they inform their everyday adaptations using data on flooding levels and weather in combination with their local knowledge. Finally, individuals invest their resources in ad hoc adaptations for chronic conditions with the knowledge that if a major hurricane occurs they can supplement their recovery with federal and state funds, private insurance, and activate federal flood insurance.

This research empirically demonstrates how people manage climate change hazards by relying on techniques they know and use locally for existing environmental challenges. They adjust their homes to be more resilient and focus on the day-to-day management of hazards rather than the risks of extreme disasters. Successful adaptation relies on deep local knowledge of ecological conditions, landscape, and social practices. For disasters, many hope they occur infrequently and count on the availability of disaster recovery dollars, insurance payouts, and community response in the aftermath. Residents believe their local knowledge to be more nuanced and informative than designations of flood maps or insurance providers, often prompting a personal assumption of risk outside of the insurance mechanisms in place.

The financial and energetic burden of ad hoc adaptation is not boundless, and how long someone is able to adapt in place depends on how much time, money, and energy they have available. In this way, ad hoc adaptation is a mechanism for inequality in which some households are more able to adapt in place than others and the burden of ad hoc adaptation is greater for some than others. Research thus far has focused surprisingly little on how families are experiencing climate change on a day-to-day basis, especially in the context of the United States. Understanding how people adapt with and without local institutional support begins to unpack an important element of the climate change experience and what kinds of adaptation actions may be better supported by policy.

Adaptation Across Scales

Coastal resource managers across institutions invest in a diverse portfolio of adaptation strategies to protect residents and structures vulnerable to climate change. Adaptation strategies range from physical infrastructure investments such as hardening shorelines, levees, pumps, and tide gates, to living shorelines and nature-based solutions, to regular beach nourishment to prevent erosion. The application of these strategies and the level of protection they provide to homes and families is spatially varied. Scenario-based studies predict that adaptation decisions in the future will be rooted in economics – a combination of the tax base and density of a community – naturally placing rural and socioeconomically vulnerable communities at the back of the line for adaptation investments (Lincke and Hinkel 2018; Martinich et al. 2013).

Empirical research makes clear that adaptation investments to date provide greater protection for wealthier communities, entrenching the vulnerability of already marginalized communities (Howell and Elliott 2018; Jin et al. 2015). More affluent communities are also considered more adept at advocating for managed retreat, the intentional and planned relocation of individuals and property from locations facing imminent sea-level rise, for example after Hurricane Sandy on Staten Island (Koslov 2016). Communities that receive FEMA funding for managed retreat tend to be white, wealthy, and politically connected (Hino et al. 2017; Mach et al. 2019; Siders 2019). In contrast, many severely eroding areas have a ‘do nothing’ approach when it comes to rising seas. If residents were to gradually leave these areas on their own, this kind of abandonment would ultimately cost governments less and homeowners more than managed retreat (Hino et al. 2017).

While governments focus long-term on building more resilient places, communities and individuals enact boot-strap resilience. At present, individual resilience efforts are costly, time-limited, and disproportionately burden the most marginalized and vulnerable, ultimately exacerbating existing inequalities (Cutter et al. 2003). This is despite evidence that overall resilience is improved through investing in social, as well as infrastructural, resilience (Aldrich and Meyer 2015; Klinenberg 2018). Disasters alone change the demographic profile of affected communities (Fussell et al. 2017; Logan et al. 2016; Raker 2020), let alone persistent, gradually worsening climate hazards punctuated by more frequent and severe disasters. Populations that experience multiple disasters with different temporalities focus on those that feel more urgent while deprioritizing slower threats (Hernández 2022). Work on climate change vulnerability, Hurricane Katrina, and other disasters that affect different people in very different ways cements the fact that climate stressors exacerbate existing inequality.

Sociological literature on disasters highlights how people at different socioeconomic levels recover at different rates and in different ways. These differential impacts and recoveries are explained based on more vulnerable people being less able to cope with environmental stress (Cutter et al. 2003; Kelly and Adger 2000). This differential ability to recover also manifests in suburban communities with similar socioeconomic status, where factors such as flood insurance and savings facilitate recovery for some (Rhodes and Besbris 2022). What the current literature does not specify, though, are the mechanisms for these outcomes during the climate stressor itself rather than post-disaster.

A growing literature on adaptation and what motivates individual adaptation efforts globally foreshadows the mechanisms for entrenching inequality during chronic climate stress. Everyday adaptations, shifted habits and routines in everyday life in response to climate impacts over time, are limited by individuals’ capacity to adapt (Castro and Sen 2022). In addition, a review of global studies on personal and household adaptation behaviors across 75 countries shows that these behaviors prioritize self-protection and household protection in response to immediate hazards rather than long-term adaptation goals (Carman and Zint 2020). Further clues for the consequences of adapting property to chronic climate stress in the United States may be writing on routine dilapidation. A study of homeowners in Chicago and New Orleans found that regular, routine dilapidation of the physical structure of a house makes housing unaffordable and worsens housing precarity, especially for senior Black women (Bartram 2023). Bartram argues that routine dilapidation exacerbates debt, prevents aging in place, and facilitates displacement and is therefore one way that home ownership counterintuitively produces environmental injustice. This study considers the maintenance required to prevent dilapidation of homes under climate stress, exacerbating the environmental injustice produced by home ownership.

Understanding where, how, and why homeowners use different climate change adaptation strategies is key to predicting the socioeconomic impacts of climate change in the context of larger scale coastal adaptation. Theories of decision-making show how people consider many factors when they make decisions, and this process depends on what they believe about their life situation (Goffman 1974; Thomas and Znaniecki 1919) and what others are doing around them (Nolan et al. 2008). This suggests that if someone’s neighbors or community is proactively adapting to climate change, then they would be more likely to adapt as well. This would equally apply to maladaptation or ignoring climate change risks all together. Sociologists find that in addition to social context, emotions are critically important in the decision-making process. Sociologists push back on classical rational choice models of decision-making by pointing out that people’s preferences change (Lindenberg and Frey, 1993). When a person makes a decision, they consider the opportunities they perceive to be available, the importance of the default option, time pressure and resource constraints, and the choices of others. Individuals usually fail to consider all the elements of available options, sometimes caused by blind spots in their knowledge regarding their options (Krysan and Bader 2009). Rather than being purely rational, people’s relationships, culture, and social interactions are central in shaping their choices (Emirbayer 1997; Pescosolido 1992; Zerubavel 2009).

Empirical work specifically highlights the impact of socioeconomic status on decision-making (Mullainathan and Shafir 2013). For example, the options someone perceives to be available to them differ depending on socioeconomic status (Dawes and Brown 2002, 2005). Considering that people’s choices are highly sensitive to context and broader social environments, it is also likely that decisions would be sensitive to the climate change context. Furthermore, the interaction of climate change and other broad social contexts in people’s lives would be expected to promote different decisions among people facing the same climate risk. Sociological research on hurricane evacuation decisions is consistent with this literature. Evacuations are strongly influenced by the social context of a place and people’s collective consideration of whether to stay or go before a storm strikes. Residents in the path of a storm join to discuss how to respond and whether an evacuation order applies to them. The way these joint decisions are made depends on the characteristics of the people involved in addition to their social context (Brunsma et al. 2010; Perry and Lindell 1991). Thus, in the real-world sociologists demonstrate that even the decision environment itself is socially created (Bruch and Feinberg 2017). In the case of ad hoc adaptation decisions, individuals and households make decisions based on their perceptions of their financial resources, the climate risks at stake, the actions of those in their social networks, their own ability to manage climate hazards, and other options available to them.

Considering the lingering gaps in our understanding of why and how people are adapting to climate change and how that is impacted by institutional adaptation context, I examine how residents in a climate vulnerable region of the United States are managing climate change hazards in their daily lives. Answering this question allows me to consider differences in ad hoc adaptation by socioeconomic vulnerability, climate hazard, and institutional context. Though we often fail to think of micro-level, everyday action when referring to ‘adaptation,’ the daily actions of individuals who shift their lives in response to climate hazards is critical to include in adaptation research (Castro and Sen 2022). Sometimes adaptation at the micro-level is agnostic, adaptive action taken without referring to climate change explicitly (Koslov 2016). Other times, I argue, adaption is ad hoc and autonomous – including the intuitive action individuals take based on their local knowledge of how to get by in places where they live in changing climate conditions. Documenting ad hoc adaptation is a necessary first step to inform institutional adaptation planning and to begin to unpack mechanisms for the social effects of climate change.

Background and Study Site

This research maximizes potential learning about micro-level adaptation, its motivators, and its costs using an in-depth case study analysis of a particularly climate-stressed region of the United States, the Outer and Inner Banks of North Carolina (OBX and IBX). Coastal North Carolina is one of the places most at risk of sea level rise in the United States, facing gradual climate hazards such as saltwater intrusion and erosion punctuated by more extreme hurricane and nor’easter events. A study evaluating adaptations on the North Carolina coast to protect coastal settlements and resources found that shoreline armoring and beach nourishment is correlated with wealthy communities while property acquisitions are more common in lower income, rural, minority communities (Siders and Keenan 2020). Further, research on property acquisitions in North Carolina showed that ‘buyouts,’ federally funded property acquisitions, were associated with the deterioration of existing housing, lower housing growth in those neighborhoods, and White residents moving out of the buyout areas (Martin and Nguyen 2021). Thus, government adaptations are unevenly distributed in relation to wealth in North Carolina and provide greater protection to wealthy, more densely populated areas.

The bulk of the Outer Banks are part of Dare County, the easternmost county in the state of North Carolina, with an estimated population of 37,956 residents in July of 2022. Though North Carolina is a diverse state, Dare County less so – with a population that is 93.5% White (not Hispanic), 2.8% Black, and 7.7% Latino (US Census Bureau 2022). Overall, the county is economically better off than the state average, with a higher median household income ($79,742 compared to $66,186 per year) and a lower poverty rate (8.7% compared to 12.8%) than the rest of the state (US Census Bureau 2022). Because of its proximity to water on all sides, and far eastern location, the tourist destination of Dare County is remote and highly climate vulnerable. While technically the largest county in the state, the territory is 25% land and 75% Pamlico Sound. Dare’s landscape is a thin chain of barrier islands surrounded by water and in the direct path of Atlantic hurricanes. Sunny day flooding through its neighborhoods is a regular occurrence, and major hurricane events are increasing in frequency.

On the Inner Banks, this research focuses on Hyde County which is located directly across the 29-mile-wide Pamlico Sound from the southern Outer Banks. The second-least populous county in North Carolina, Hyde County of approximately 4,576 residents and is almost entirely located in the floodplain. The county lost nearly 500 hundred residents between the 2018 and 2022 Census estimates. Hyde is more diverse than Dare County, having a population that is 68.4% White, 27.7% Black, and 10.2% Hispanic (US Census Bureau 2022). Over the past decade the county has increased in its percentage of White and Hispanic percentage of Black residents, indicating that population loss is occurring among Black residents at a higher rate. The county is more socioeconomically vulnerable than Dare County and the state overall, with a median household income of $43,724 a year and 21% of persons living in poverty.

Hyde county is also highly vulnerable to flooding. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), 83 percent of residents live in what the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) defines as the 100-year floodplain. Like Dare County, Hyde County depends on tourist dollars from visitors to Ocracoke Island as well as for recreational hunting and fishing in their inland territories. Aside from tourism, the Hyde County economy is fueled by agriculture and the fishing industry.

The Outer and Inner Banks of North Carolina is a rich field site for studying climate adaptation. The state implemented one of the first coastal zone management programs in the U.S. (Kittinger and Ayers 2010) and has avoided hardened structures in favor of beach nourishment to prevent erosion along shorelines. In 2003, the North Carolina General Assembly unanimously voted to formally adopt a ban of new permanent erosion control structures, like sea walls and dikes.Footnote 1 In their recent study, Siders and Keenan (2020) mapped the three primary adaptation measures throughout the North Carolina coastal plain. Their analysis demonstrated that the existence of armored shorelines primarily along the sound side of the Outer Banks and beach nourishment along the ocean side, and some armored shorelines on the Inner Banks in Hyde County. Notably, neither Hyde County nor Dare County had any FEMA funded property acquisitions at the time of this analysis.

Many Inner and Outer Banks families are historically rooted in their locations and some claim direct relations to original British settlers or shipwrecked pirates. Parts of the Outer Banks remained so remote for centuries that their dialect closely mimics Elizabethan English. These lifelong residents have long dealt with harsh climate hazards. Native residents talk about how there were homes in the early 1900s that could be placed on logs and rolled away from rising sea waters during severe storms. Many Outer Banks residents are accustomed to living on a sand bar that constantly moves and changes. These familiar environmental hazards that have long affected the region, though, have been intensified by climate change in recent years. Sea level rise predictions are clear – much of the county will be underwater by the end of this century even in the most conservative estimates. Residents, however, rationally explain their desire to adapt in place and live with water until it is completely submerged and inaccessible.

Given hurricanes in recent years and intensifying climate hazards, climate migration projections would predict migration away from the Inner and Outer Banks (Hauer 2017; Hauer et al. 2024). According to US Census data, however, Dare County’s population increased population by 7.6% from 2010 to 2018 while Hyde County’s population decreased by 10% and these trends continued through 2022 (US Census Bureau 2022). In media interviews and community sessions with the first Chief Resilience Officer (Jessica Whitehead) of North Carolina, Outer Banks residents described their eagerness to adapt in place until the region is completely and constantly submerged with water and brainstormed strategies for local and state government to increase the county’s resilience. Somewhat paradoxically, in news interviews and community meetings residents concede that their homes will eventually be underwater but emphasize doing everything they can to maintain life as it is for now. On the heels of Hurricanes Florence (2018) and Dorian (2019), the North Carolina Office of Recovery and Resilience was created to administer disaster recovery dollars and employed unprecedented levels of resilience and mitigation efforts throughout the coast yet how those efforts are perceived and incorporated into people’s daily climate response is unknown.

Methods and Data

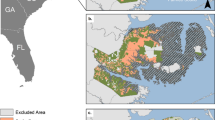

Given that we know so little about the everyday lived experience of climate change, I use mixed qualitative methods to understand why and how homeowners manage climate change impacts in their daily lives. I combined in-depth interviews, key-informant interviews, participant and direct observation, and informal conversations to document adaptations in daily life in two adjacent coastal counties in North Carolina shown in Fig. 1. These counties had different levels of resources and climate risks that allowed me to observe differences in climate change response by social and institutional adaptation context. I collected data over one year from July 2020 through August of 2021. This field work timing spanned three seasons as well as both hurricane and nor’easter season in this climate vulnerable area. In total, I completed 100 in-depth interviews with residents, met with local and community leaders, and conducted ethnographic observation yielding over 100 single-spaced pages of field notes. The unique combination of observation of people’s homes, work on boats and in fields, and on their properties across seasons, spending unstructured time with research participants and in the study area, and interviewing residents at length about their management of climate stressors yields a nuanced picture of why and how residents are autonomously adapting to climate change.

My research design was grounded and iterative. My fieldwork began with key informant interviews with state level experts on resilience and disaster recovery in February of 2020 followed by interviews with coastal hazards experts in Dare and Hyde Counties. After initial interviews, I spent one month conducting participant and direct observation in the coastal study area where I identified the characteristics of different communities throughout the Inner and Outer Banks, collected data on adaptations and responses to hazard events, and used that information to identify three key focus areas for more in-depth research seen in Table 1 below. These areas were selected because within this climate vulnerable region, they experience the most immediate and disruptive climate impacts with the best likelihood for observing an array of household adaptations.

Following the identification of focus areas for research, I recruited participants beginning with a few nodes in each geographic area. I relied on local nonprofit and environmental agencies for providing connections to community leaders and residents within the focus areas for interviews. I also contacted lifelong residents, business owners, farmers, and fisherman as well as residents owning properties listed for sale at the time of this research. Residents were incredibly open to meeting with me for this project, and regularly provided additional contacts for interviews. I interviewed no more than one suggestion from each respondent to prevent biased clustering in my conversations. Through my ethnographic work, I found that communities in the Southern Outer Banks and throughout the Inner Banks are rural and tight-knit. This local character facilitated my recruitment and generated a wealth of rich ethnographic observations.

I made two strategic decisions in my sampling which inform my findings: first to focus on the most climate impacted areas of the study region and second to focus on property owners. My sample of interview respondents represented the diversity of the region by including a mix of White (65%), Black (15%), and Hispanic residents (20%), native-born and immigrant residents, and men and women with a wide range of ages from 30 years old to 97 years old. This sample is more diverse than the overall study region because my research focused on the most climate impacted areas within these two counties which had higher concentrations of Black, Hispanic, and elderly residents than the study area overall. These residents may understand adaptation challenges differently than those who either live in less climate vulnerable areas within the region or different social, political, and financial resources for adaptation. My decision to focus on property owners allowed me to understand both how individuals adapted their lives and their property. This decision does not allow me to speak to the adaptations of renters who live in this region, though my ethnographic observations indicated that the most socioeconomically vulnerable residents lived in highly flood and hurricane vulnerable rental properties in both the Inner and Outer Banks.

I developed my in-depth interview guide informed both by early ethnographic observations and key informant interviews, existing literature on climate change adaptation, and an analysis of transcripts from local participatory resilience planning meetings. It took spending time with people, observing their lives in close detail, to capture shifts in their daily actions in response to the gradual stress of climate change. Interviews and observations informed one another, building on and growing from prior findings and testing theories as they developed inductively. In-depth interviews with residents ranged from two to eight hours during which we discussed personal and migration history, daily life, livelihood stability, climate changes, investments, climate stressors, adaptations, climate hazard experiences, strategies and intentions for staying and migrating, and assistance received among other topics. To focus on the roles of resources in climate response and property ownership, interview sections were included on property ownership as well as on investments in responding and managing climate hazards now and in the future (insurance, home adaptations, hurricane recovery costs, bulkheads, breakwaters, sand shoveling or bagging, etc.). I concluded interviews in each of the three focus areas as I reached saturation indicated by no longer learning new information from additional interviews.

I analyzed interview transcripts and fieldnotes in NVIVO, using first open coding followed by thematic coding of property, lifestyle, and risk adaptations. I also coded residential interviews for mentions of institutional contexts, including disaster recovery policies and programs, government agencies, insurance, and community and financial institutions. Lastly, interviews were coded for residents’ descriptions of climate change, more general ecological change, and future perceptions.

Findings

Like in many places, the climate is changing on the North Carolina coast faster than institutions can adapt as evidenced by chronic flooding and dune breaches. Residents living in climate vulnerable areas are presented with climate changes that impact their lives and homes. As such, this research reveals how people are responding by adapting in ad hoc ways. Residents living on the ‘frontlines’ of climate change base the adaptations they make on local knowledge and the resources available to them. In fact, residents use knowledge from the experience of previous quick-onset disasters as well as how to access federal recovery dollars and programs to facilitate adaptation to climate change. Uncoordinated, ad hoc adaptations are differentially available to people depending on the resources they have and the ways in which policies define where they live as climate “vulnerable.”

Relying on residents to adapt to climate change on their own has consequences. Both counties in this research had a subset of affluent residents that upwardly skewed their median incomes, but even considering this, had lower median household incomes and higher poverty levels than the state of North Carolina. One might consider the ad hoc adaptations they employ and imagine wealthy homeowners spending whatever it takes to live comfortably – in some instances that was the case. In most instances, though, residents investing these dollars were firmly middle class – retired school teachers, forestry service workers, or bank employees. Participants included farmers or fisherman, some wealthier than others, most of whom lived modest lifestyles. Many residents inherited their homes from family or built their own homes in the 1970s – a trend on Hatteras and Ocracoke Islands. The ad hoc adaptations residents made were rarely luxuries and required spending tradeoffs in other areas of their lives.

Ad Hoc Adaptation in Context

Living on a barrier island jutting out into the Atlantic Ocean requires a hardy spirit. The idea of climate change is relatively new to residents, but the reality of adapting to environmental hazards is a way of life. Across the 29-mile Pamlico Sound that sits between Hatteras Island, part of the Outer Banks, and mainland North Carolina is a fertile, eroding landscape. Not unlike the disappearing Southern Louisiana coast, the Inner Banks of North Carolina are waterlogged, battered by hurricanes, and predicted to ultimately be submerged by sea-level rise. These two sides of the Pamlico Sound look entirely different. Hatteras Island is speckled with few trees and strong wind constantly carrying sand across roadways. Across the sound in Hyde County, an open expanse of farmland, pine and cypress trees, marsh, duck impoundments, and nature refuges are bordered by ditches and canals carrying water off fields and out of yards. You can only travel from Hatteras Island directly across the sound to Engelhard (in Hyde County) by driving all the way north up the island, west across bridges through Manteo, and then turning south down the other side of the sound two hours later.

If wind and ocean overwash, a common occurrence, moved sand and water onto NC Highway 12, the famously ‘most repaired roadway in the United States,’ the drive from one side to the other was impossible. Back-hoes and bulldozers wait permanently parked by problem areas of NC Hwy-12, ready to clear sand and water from the road and ‘rebuild’ breached dunes. This process can take days. If the tide stays high, the Department of Transportation can move infinite sand and water and the ocean will continue to put it right back on the road. Residents rely on the state to maintain their access to homes and property through constant maintenance of climate battered roadways, and regularly check NC-DOT roadway updates via Facebook and Twitter posts by the agency on which roads are cleared, open, closed, or have standing water.

The institutional maintenance of dunes, roadways, and ferries was something residents assumed would continue and relied on in their decisions to invest in their homes and properties. When Ocracoke residents were asked what would happen if the state stopped maintaining ferries to the island, every respondent on the island told me that “it would never happen.” After probing, one said “if we can’t get to the island then we’d be screwed.” Outer Banks residents in Dare County expressed outrage when the NCDOT was taking longer than they thought was necessary to clear roads after dune breaches or when they “let the dunes get to low.” Inner Banks residents in Hyde County received the list institutional protections given that these protections are concentrated along beachfronts; however I rode around with many residents who wanted to show me the poor state maintenance of ditches that they believed could prevent chronic inundation with better maintenance that should be done by the state.

Climate Change Adaptations to Homes and Property

“Was it Isabel? Irene? No, it was Isaac…” Sam talked about storms like old friends and, like most people I met on the Outer Banks, keeps waterline marks in Sharpie on a post outside his house – Isabel’03, Irene’11, Dorian’19… the list goes on. Sam’s house had never flooded, sitting atop posts elevating it four feet above the ground gave it just enough clearance above past floodwaters on its soundsideFootnote 2 lot. It took another hour in our meandering conversation about life on Hatteras Island and climate for Sam to realize I was asking him a series of questions about what he has done to make his home storm resistant, unlikely to flood, and wind tolerant. Well into our conversation Sam heard a rumble outside, jumped up, and said, “hold on a minute I’ll be right back.” He returned about fifteen minutes later and we eased back into our conversation about the hurricanes he had weathered on Hatteras Island. “That was Ron who trims trees. He knows whenever he has a load of wood chips to bring them here instead of taking them down the island to the landfill. I use them to fill the yard and lift up my parking spots,” Sam explained, as though it was the most obvious thing in the world. Residents throughout the Outer Banks and Inner Banks buy loads of fill, wood chips, or sand to bring areas around their house up a few inches or a foot – just enough so that water from heavy rain or tidal flooding runs off their property instead of sitting stagnant above the high water table. A few inches of fill often mean floodwater stops at the tops of the tires on a car rather than over the tire, an important distinction over the life of a coastal vehicle.

Buying fill or using one’s social networks to get it for free is a small part of life at sea level. For fill to be worth purchasing, the lot you live on needs to be high. On the Inner and Outer Banks, a lot two feet above sea level is considered high and four feet above sea level is practically mountainside. Locals on the Inner and Outer Banks know to spend the extra money to purchase a high lot and to situate their home on the highest location of their property. Once a house is high enough to sit above a typical flood event, the primary concerns are wind, hurricanes, and functioning septic systems. In Hyde County, fill is almost never enough to keep property above water. Here residents dig deep ditches and canals to carry heavy rainfall and tidal flooding back to the Pamlico Sound. Some residents even self-fund or communally fund small levees to prevent hurricane storm surge from washing across their agricultural fields. Outer and Inner Banks residents living at the waterfront – always soundside waterfront, year-round residents unanimously say they would never live beachfront due to their local knowledge of ocean overwash patterns and the shifting of barrier islands – install private bulkheads, choose to live as far inland on their property as possible leaving wetland plants between their homes and the water, and, if they build their homes, elevate multiple feet above building code.

Residents described deciding how high to elevate by weighing the highest flood level they had experienced, the height that they could afford to elevate, and the number of stairs they felt physically able to climb while carrying groceries. They did not, however, mention checking building codes as a metric. In an interview a building inspector who had worked for years in both Dare and Hyde counties, he confirmed this describing inspecting houses that owners had adapted well beyond building codes based on their own knowledge of flood patterns which provided much more protection than the “run of the mill codes” coming from the counties.

Residents throughout the Outer and Inner Banks speak about changing their homes to adapt to climate conditions as “second nature,” and base their home adaptations on things that have worked through hurricanes in the past. Table 2 below summarizes common adaptions to home and property ethnographically observed among the majority of residents throughout the study area. Those who did not engage in these adaptations cited their lack of resources as the reason for not engaging in these activities, underscoring ad hoc adaptation as a mechanism for inequality in the changing climate.

The adaptations to home and property in Table 2 are common changes to homes rather than unusual upgrades. Homeowners had either done these adaptations if they had the financial resources, discussed observing their neighbors doing and wishing they could, explained saving up for them, or noted that they “had to do them” in the case of lot elevation, bulkhead or levee installation or elevation if their neighbors had completed these actions.Footnote 3

Most homes in the focal areas of study were at least 15 years old, and the majority were 20–30 years old. These homes were built before building codes had been updated to require new elevation heights or elevated septic fields. Residents living in older homes gradually make these ad hoc adaptations to their properties depending on the hazards they face in the location of their homes. Constantly updating building codes to include functioning ad hoc adaptations common in coastal areas is critical to ensuring that newly constructed housing is built to a climate-adaptive standard.

These ad hoc adaptations come from deep local knowledge of managing past environmental hazards. Longtime residents explain “looking out for” new residents by informing them of the adaptation actions that are necessary to live in this climate stressed region. Sheryl, a longtime Hatteras Island resident, recounted approaching a young couple in the process of building a new home across the street from her house tucked back in one of the few wooded areas known to be high ground in Buxton. Looking out from Sheryl’s deck I could see water filling part of her yard where Sheryl and her husband had taken fill from to raise the area they built their house on. Since they removed dirt from that area it had joined the abutting marsh. Sheryl said she crossed the street with a copy of the book Sea Level Rise, by renowned scientist Orrin Pilkey and his son, to gift the new neighbors when she saw the couple stopping by to make plans for building their house after buying the lot. Sheryl explained, “I thought they should know how vulnerable this area is to sea level rise and what kind of flooding they would be dealing with before they started building.” When they were reluctant to hear her concerns, she gave them advice on where to build their house on the lot based on where she regularly saw standing water from across the street. “I’m just worried for them,” Sheryl told me, “I would never build here now with as many storms as we’re having… especially not if I was just starting out.”

Though longtime residents were concerned about climate risks and warned new residents of risks, they did not express concern about their property values decreasing as a result of these risks. On the contrary, residents on the Outer Banks experienced soaring property values during the research period despite climate hazards, drawing residents escaping urban residences during the COVID-19 pandemic to work remotely in this coastal area. Residents on the Inner Banks reported low property values for homes due to economic decline and high property values for large areas of farmland. Respondents did not express concern about property values related to climate risks or flooding risks, though they did note selling for low prices if they had been unable to adapt their home and it had fallen into disrepair.

On the other side of the sound, I met Herbert sitting in his porch rocking chair looking out over his notably dry back yard in Washington, North Carolina, where he had relocated just a year before we met. Herbert said that he left Engelhard, Hyde County when it was time to go – that he was, “tired of pumping water out of the yard.” Prone to storytelling, Herbert chuckled before describing the man who bought his old house who was a local business owner who moved to Engelhard from out of town. The new owner bought Herbert’s old house for $5,000 through a word of mouth deal. To hear him tell it, Herbert was tired of dealing with the water and just wanted out. He had also run up a debt on his Lowe’s Home Improvement credit card, ironically to pay for flood repairs to his home, that he couldn’t pay down without the profits from the house. He told the new owner he had to pump the yard when it rained and even left him the sump pumps he had bought for the property. One day about a month after Herbert agreed to sell the house and moved out, the new owner called him “fussing about the toilet not flushing.” Herbert got in his truck and drove over an hour back to Engelhard to see what was the matter. As he drove up he just shook his head looking at the lake of standing water around the house. “I walked in the door and I told him ‘You idiot, I done told you that you got to pump the water outta the yard.” The new owner scoffed, saying he had bigger problems because “the dern toilet was overflowing.” Herbert laughed out loud retelling how he had to explain “to this grown man” that a toilet will not flush when the septic tank is under standing water. Local knowledge like this is critical to managing the climate throughout the Inner and Outer Banks.

The costliest adaptations were often reserved for business needs and disaster recovery funds. Herbert wanted to elevate his home after his third and final flood insurance claim following a hurricane’s tidal surge that buckled all the floorboards in his one-story house and waterlogged the bottom half of his drywall. He explained that elevating a home would have reduced the need for constant ad hoc adaptations from chronic flooding. FEMA specialists told him, however, he did not qualify for assistance because floodwater had to be over the floor, not just come up through the bottom of the floorboards. Even when limited resilience dollars or state disaster recovery funds did reach Hyde County, the distribution was perceived to be unequal. Black residents said they had less access to those resources. As one Black respondent explained, “Nobody is coming to talk to us about programs. Every time there’s a program seems like all the people the folks at the county are kin to get picked. People take care of their own. That’s the way it is.” This sentiment was repeated by many Black residents who participated in this research, referring to “those at the county” and “their kin” as those that receive aid, all of whom were White residents and families.

Elevating a home above flood levels was the most expensive but also effective adaptation households could undertake for chronic flooding, typically costing approximately $100,000. In this research, White residents with means sometimes elevated their homes with private funds or bought a new lot and relocated their homes over short distances to avoid chronic flooding. These very costly adaptations were sometimes ad hoc, but more often observed with the successful navigation of programs providing disaster recovery dollars to complement the costly relocations or elevations. Residents who had successfully received FEMA dollars to elevate their homes after hurricane flooding often took that opportunity to make additional changes to their home at their own expense, for example, rebuilding an exterior deck, elevating higher than required, or changing interior flooring to be water resistant.

Elevation was differentially available to residents by receipt of disaster recovery assistance as well as by the age and health of household members. Older residents across the entire study area complained about the way elevations limited their mobility. Disaster recovery programs paid for a home elevation and long winding ramps to one entry to the home, but no elevator. Lisa, at 67-years old, contemplated her decision to elevate her home independently but as minimally as possible following hurricanes in Hatteras Island,

I have trouble with my knee now. It's hard for me to get up and down the steps sometimes, and there aren’t that many at my house. We went as low as we could when we raised our house up. When you elevate, some people go as high as they can to feel way above the water. Some people raise it two stories above the level of the road, and you know, then you have the steps to climb and a lot of groceries to carry. And I don't think people are thinking about that when they take it that high. I thought about that.

Further, Black and Hispanic residents in this study were less likely to have received FEMA assistance to elevate their homes after hurricanes. Though home elevation is a resource intensive adaptation, elevating reduced the resources a resident would invest in ad hoc adaptations to flooding. The lack of FEMA assistance for Black and Hispanic households in this research correlated with this residents’ expressions of feeling overburdened by adaptation or, in cases like Herbet’s, relocating to escape the chronic adaptation burden.

In addition to financial resource investments, adapting homes and property to climate impacts also requires time, mental and physical energy, and local knowledge that influence individuals’ routines in everyday life. Pumping water off a person’s yard each day is one among many examples of everyday adaptations in this climate stressed region. I observed residents maintaining and regularly giving one another tips on daily cleaning routines to keep mold and mildew at bay in their homes, describing opening windows and wiping all of their walls with bleach each morning. Individuals explained how they kept uncluttered homes to prevent mildew from spreading and also so that there would be less to clean out if the house flooded. In general, many Outer Banks residents aim to have fewer things. As one resident put it, “when it could all be gone in one storm, you learn to live light.”

Outside of their homes, residents maintained complex information chains as an everyday adaptation to stay informed of roadway flooding, overwash events, and the need to prepare for wind and flood events at their homes. Residents in Hyde County relied on specific institutional infrastructure for flood and weather monitoring. They showed me the different United States Geological Survey (USGS) flood gauges they monitor regularly to predict when and where they can expect flood water. In addition to checking USGS flood gauges, residents also monitor wind speeds and tides and know that a Northwest wind at high tide will cause the worst soundside flooding on Hatteras Island and in Swanquarter, Hyde County. For weather, residents primarily monitored the Duck, NC US Coast Guard Light Station reports. When leaving the house, daily routines ensure that individuals were prepared for climate conditions. Households kept old cars to drive on overwash days that salt could corrode, and no one would buy a new car because they explained that the saltwater and air are too hard on vehicles. I observed phone chains of individuals calling one another to warn about incoming flooding from the sound on both the Inner and Outer Banks.

Daily climate conditions such as wind speeds, tides, and rain patterns determine where and how flooding moves through this study area. Rather than rely only on weather data, residents warned one another about speed and depth of the water in their respective locations to advise on which driving routes to take to work or to pick children up from school based on the daily climate. They also called to inform one another about flooding around different homes so that residents could rush home to tie down outdoor property, move parked cars to high ground areas in town, or bring pets inside before flooding. The hardware store in Engelhard, for example, had the highest parking lot in town. When flooding was imminent residents parked their cars in the general store parking lot rather than at their homes and carpooled back to their homes in local vehicles that were higher off the ground like farm trucks. Local knowledge of flood gauges, elevation levels, wind and tide significance, and ad hoc actions to avoid property loss was key to the daily management of climate conditions throughout this study site. Responding quickly to these local sources of information about climate risk require resources like agency and flexibility in one’s work schedule to return home at a moment’s notice, change routines for picking up children, or reschedule medical or administrative appointments when road conditions complicate a person’s access.

Adaptation Limits

Residents throughout the region had different limits to the bounds of their ad hoc adaptations to home and property. Some such limits are financial, reaching a point where they do not want to invest further in their climate vulnerable home. More often those limits are energetic. Residents get tired of “pumping water out of the yard,” of climbing steps up to their elevated home as they age, or of evacuating more and more frequently as there seems to be less and less time between sitting in hurricanes’ cones of uncertainty. The likelihood that Herbert would have to rip out his floors, replace the insulation under his house, and replace his drywall a fourth, fifth, and who knows how many more times surpassed the limits of his ad hoc adaptation efforts.

What all residents agreed on, though, was that they would adapt in place for as long as they felt they had financial and energetic resources to do so. I pressed this point in interviews, especially when residents mentioned their knowledge of sea-level rise maps, and they were repeatedly “all in” on living where they lived for as long as possible. For the majority they said that meant adapting in place until they could not access their property because it was completely underwater year-round, whenever that might be. They do anticipate that their homes will eventually be underwater but feel unsure of when that will occur and are mostly determined to stick it out until the bitter end.

There were some exceptions, though, and those exceptions were consistently non-native residents of the region. Martha moved away from the Outer Banks in 2020 after living there for more than 30 years. That was not her first move. Ten years before she had relocated from Hatteras Island up to Manteo, finding it more accessible, closer to work, and less vulnerable. As she aged, she increasingly compared the landscape around her to sea-level rise predictions from NOAA. By 2020, she and her husband decided it was time to “tap out.” “We love the Outer Banks. We still love it,” Martha reminisced as she explained her move, “but we’re getting older. And we know how to read the writing on the wall. If we aren’t prepared to access Manteo exclusively by boat in our later years then we shouldn’t live there anymore.” Martha and her husband looked at the map, talked to friends, and planned a move to what they thought would be a similarly small and rural but less vulnerable coastal community halfway up the coast of Maine. “We’re climate migrants,” she told me during a video conversation from her home in Maine.

Though residents on both the Inner and Outer Banks find themselves adapting to climate impacts, this adaptation burden is intrinsically different for residents who chose to move to the Outer Banks barrier islands for the rural, beachside lifestyle in harmony with nature decades ago compared to that of residents descended from generations of ancestors on the Inner Banks who find themselves in a place that has become increasingly more climate vulnerable over time. On the Outer Banks some residents with climate knowledge, the luxury of retirement, and socioeconomic security made forward-looking choices to migrate away from the islands or to buy second home properties in the mountains of North Carolina or Virginia to evacuate to during hurricanes. More socioeconomically advantaged residents throughout the Inner Banks of Hyde County did not consider migrating, and none did so during this period of research. Those who migrated away from the Inner Banks cited the burden of adaptation and left in distress after adapting their properties until they ran out of the energy, psychological and financial, to continue doing so. These residents described being plagued by the consistent dilapidation of their homes from constant water around their properties, distinct from the more typical hurricane or wind-based damage on the Outer Banks.

Dilapidation from chronic climate hazards is not institutionally supported by policy infrastructure in this region, whereas repair of damage from disasters can be supported through the existing federal disaster recovery policy infrastructure. This balance suggests that institutional context is more robust on the Outer Banks, along the barrier island chains, because it is responsive to disasters rather than chronic climate stressors that plague the more socioeconomically vulnerable Inner Banks. Unlike in moments of quick-onset disasters, coastal residents living with sea-level rise, more frequent and intense storms, saltwater intrusion, chronic flooding, and land subsidence independently shoulder the weight of these climate hazards dilatory effects on their property. Throughout this research, the most socioeconomically vulnerable individuals described feeling this weight more acutely, specifically Black residents, the elderly, those on fixed incomes, and undocumented immigrants. These residents also primarily lived on the Inner Banks, where chronic flooding was more common than hurricane damage unlike on the Outer Banks where most damage occurred during hurricanes when everyday adaptations were insufficient.

As the adaptation energy required to maintain a home or property increased, disinvestment in the most vulnerable properties similarly increased throughout the Inner and Outer Banks. Distinct from planned ‘managed retreat,’ residents were autonomously retreating from climate hazards in big and small ways during this period of research. Martha’s family moved further than Herbert’s, but both families relocated away from a level of climate vulnerability they grew tired of managing. Farmers in Hyde County regularly stopped planting the borders of fields along canals where saltwater intrusion left the soil salinized and less productive. At times farmers’ retreat from entirely unproductive fields was both temporary (multiple years to multiple decades) and facilitated by government programs that provided funds for entering unproductive acres into wetland restoration programs. Homeowners also made tradeoffs to manage water on their own property. Many moved dirt from one place to another to shift the topography and facilitate water runoff, while others stopped filling one area on their property and allowed it to be submerged with water to the benefit of the rest of the parcel. When some structures were destroyed by floods, wind, or storm events, owners built them back further from the water to reduce future storm damage. This was most often seen with docks that residents rebuilt further inland from the waterline along the sound, rather than rebuilding them out in the open water where they were more vulnerable to hurricanes.

Older residents in inland Hyde County acknowledged that the population is decreasing and eventually the land they lived on would be completely underwater. They also assumed this would occur after their lifetimes. As one resident remarked, “Oh honey I’ll be long gone before the ocean takes this place.” That acknowledgement caused some to plan for a future where their homes were not inherited by their children. Donald, from Middletown explained,

I’ve started going through things, you know. Getting rid of stuff. Because when we go our kids won’t want this house. My son told me ‘Dad this house will be marsh any time now. I don’t want anything to do with it.’ We don’t want to leave them with a big mess of stuff to sort out when we’re gone. And nobody will want to live here then. It’s just honest.

As Donald recognizes, residents across this coastal region acknowledge the limits to their ad hoc adaptations. If sea levels rise to predicted levels, inland Hyde County is lower will be submerged before Hatteras Island or Ocracoke Island. On the Outer Banks, residents adapt yet also frequently mention that “one bad storm could wipe out the island entirely.” The day-to-day hazards residents believe they can manage, a completely catastrophic storm that cuts inlets through the barrier island and floods higher than base-flood elevation they say will be beyond the limits of their adaptations. In fact, residents make less ad hoc adaptations and often stop carrying funded flood insurance after elevating for two reasons. First, they believe flooding higher than what they elevated would be so catastrophic that the island would no longer be inhabitable and second, because flood insurance does not cover anything below the floorboards of the house itself or that occurs from chronic climate hazards so elevated residents see no reason to continue paying for it. Residents often described flood insurance as “out of touch” with their most urgent adaptation burdens and therefore a low priority investment that only paid off if they experienced a major hurricane. Inland, residents joke with each other about whose house will be an island first. Their houses are elevated and residents closest to the sound say they fully expect their homes to be on stilts above the water within their lifetimes.

Discussion and Conclusions

This study asks how homeowners are adapting to climate change. Using evidence from an ethnographic and interview study of two coastal North Carolina counties, I find that coastal residents recognize the climate hazards impacting their communities and adapt in ad hoc ways using their locally situated knowledge of climate conditions. Residents adapt their homes and properties ad hoc within the context of institutional adaptations such as road and ferry maintenance, dune preservation, beach nourishment and dike installation required for the overall livability and accessibility of this region. Though residents have often received funds through institutions for disaster recovery programs or flood insurance claims after major hurricane events, the bulk of adaptions to homes and property occurred ad hoc to address chronic climate hazards such as overwash, saltwater intrusion, and tidal flooding. Ad hoc adaptations focus primarily on homes and property, and include improving property, managing water, and letting go of pieces of property or retreating from hazards in big and small ways.

Unlike in moments of quick-onset disasters, coastal residents faced with sea-level rise, more frequent and intense storms, saltwater intrusion, and land subsidence constantly manage these climate hazards. This management requires adaptations and accommodations of homes, property, and lifestyle that occurs on the fly – not on the schedule of federal disaster recovery dollars – though they do assume infrastructure adaptations will be implemented by local or state government that maintain access to the region as a whole and provide coastal protection along the beaches. In short, individuals take on the burden of their own property under the assumption that institutions will maintain basic services and access to the places where they live. It is not surprising that homeowners are adapting by spending money and time making their homes and property more resilient to the changing climate. What is surprising, though, is that we know so little about what these adaptations entail. These findings represent a foundational first step in unpacking the ways that people manage the climate change hazards that are now chronic parts of life in climate vulnerable communities.

Adaptation Decision-Making

Residents made different adaptation decisions in this research based on a few factors. The first was the financial, physical and mental, and social resources required to adapt. This was not constant but varied depending on how long someone had been adapting and how much energy they had to continue doing so. Access to credit, debt, and age were all mentioned in individuals’ considerations of what adaptations they might make to their homes – for example, changing flooring material to be impermeable or raising electric outlets higher on the walls. Those with less financial resources available made lower cost adaptations, however those lower cost adaptations were usually less effective over time than a more costly home elevation, change of materials, or installation of roof straps. More socioeconomically vulnerable residents also more frequently decided against purchasing flood insurance “until they could afford it,” a date that often was pushed further and further into the future leaving them at increased risk in a disaster and with a greater reliance on their ad hoc adaptations during hurricanes.

Individuals also considered how others were adapting when making their own decisions. Throughout this fieldwork when family members or their local institutions were relocating, individuals were more likely to decide to do the same. Residents also determined if they needed to add enough fill to raise their lot or raise their bulkhead on the sound based on neighbors’ behavior – if a neighbor raised their lot or bulkhead adjacent properties had to do the same as the water would be pushed onto their property or over their bulkhead otherwise.

Lastly, individuals considered climate risk and how long they could manage it. This factor varied by age, personal ties to place, and subjective climate experiences. Some would consider the adaptations they could afford and whether or not they would be enough for the risks they perceived, while others considered how long they planned to live and whether they thought things would be “bad enough” to force them to move away before or after their lifetime. Still others would decide that there was no real risk to them after elevating their homes as high as possible, and continually make all other adaptations they were aware of to continue maintaining their property in place.

Though respondents universally acknowledged that the places they lived would be permanently submerged by sea level rise eventually, this did not deter the large majority’s ad hoc adaptation. Native residents were resigned to adapting in place until that place was no longer above the waterline all the time. For residents more than 60 years-old, they assumed this would be after their lifetime and, based on that, worried more about their physical resources to continue adapting in place than the place being submerged. For non-native residents, the calculus was based on their own quality of life and resources to move to somewhere providing a similar quality of life. Though it is tempting to assume it rational for awareness of sea level rise and climate change predictions to prompt individual disinvestment in a place, the large majority of residents in this research adapted ad hoc despite the foregone conclusion of future inundation.

There are many reasons that motivate individuals to invest in places despite knowledge of future inundation and this finding is supported by the large literature on place attachment (Adams 2016). Further, residents in the most vulnerable areas within the study region focused on the most imminently pressing challenges of adapting to daily climate impacts rather than future hurricanes or eventually being underwater. Like other research considering communities impacted by multiple simultaneous stressors with varying temporalities, this study shows that populations focus on their most immediate and pressing threats (Hernández 2022). This work extends this conversation by theorizing a case where the slow, chronic threats are more immediate to individuals than the more extreme but less frequent disasters like hurricanes and permanent inundation.

Ad hoc adaptations occurred in the context of institutional adaptations through disaster recovery programs, insurance mechanisms, and state infrastructure and required these supports to facilitate life in this coastal region, but were not informed by local planned adaptations and policies. Residents assumed that they could apply for support to recover after a major hurricane event, especially along the Outer Banks, but otherwise considered their adaptations to chronic climate conditions as their own independent responsibility and the maintenance of local infrastructure and waterfront protections to be the responsibility of institutions. Residents of the Outer Banks expected the Department of Transportation to clear the roadways after overwash so that their properties would be accessible and Ocracoke Island residents, only accessible by ferry, expected the ferries to be maintained and available to them. Along the Inner Banks, residents adapted their own properties but discussed the importance of local and state government maintaining cleaned out ditches and water canals to prevent flooding.

Implications for understanding the Social Effects of Climate Change

This study gives teeth to the literature on the social effects of climate change. Existing literature makes clear that climate change is both unfair, often most severely impacting communities and nations that have contributed the least to carbon emissions, and that it will exacerbate inequality. Scholarship to date is less explicit about how climate change will perpetuate inequalities. I argue that ad hoc adaptations are one mechanism by which existing inequality will be exacerbated by climate change. These findings demonstrate how ad hoc adaptations are a mechanism for climate entrenched inequality. First, ad hoc adaptations require time and money, both resources that are a greater burden to socioeconomically people. Second, these findings support scholarship on everyday adaptations in that knowing how to successfully adapt to climate hazards on your own requires extensive local knowledge of the ecosystem, flood patterns, insurance markets, disaster recovery programs, and social networks (Carman and Zint 2020; Castro and Sen 2022). Lifelong residents and socially and politically connected residents have greater access to local knowledge and connections to facilitate ad hoc adaptations. In addition, many adaptations also rely on social networks, especially those adaptations that are enacted communally such as canal pumping systems or connections for limited construction and fill materials, which is also consistent with the logic of community capacity tenant of everyday adaptation theorized by Castro and Sen (2022).

These realities of independent adaptation are compounded by the pressures of daily life, weighing more heavily on some families than others. Adapting to chronic flooding, shifting your work schedule or rescheduling medical appointments due to overwash, or spending time working on your home all require a certain degree of control over one’s work schedule, time, and energy. Even if someone has the agency to adapt, can they manage climate hazards on top of everything else in their lives? The point at which this calculus becomes too much to handle is different depending on each person’s unique life situation. Without making adaptations to your home, for example, each flood event does more damage and requires more time and resources to recover from. This is consistent with Bartam’s (2023) findings, that routine dilapidation requires constant repair especially in an environmentally stressed area. The risk of not maintaining one’s property, according to Batram’s findings and respondents selling their dilapidated homes at a loss when they moved away with debt in this research, the risk of not doing so could include displacement, debt, and reduced property values. In the short term, this points to the critical importance of both funding programs to support low-income homeowner’s routine maintenance as well as regularly updated building codes in coastal areas. Building codes that include functioning adaptations in a local area can help ensure that structures can sustain high winds from storms and sit above waterlines in chronic floods. They also have the potential to reduce the costs of recovery after climate hazards damage.

Furthermore, disturbing trends emerged among who adapted in what ways. Historically marginalized Black residents on the Inner Banks more often made less expensive but also less successful adaptations, and more often moved away to neighboring counties with slightly less flooding. Elderly residents also moved away from both sides of the Pamlico Sound and cited needing community support before, during, and after flooding and storm events. Is this slow movement away from these areas by Black and elderly residents an example of the ‘displacement through abandonment’ the literature cautions (Hino et al. 2017; Salvesen et al. 2018; Siders 2019)? Given that case-study research finds that managed retreat funding is likely to reach white, wealthy, and politically connected communities (Brady 2015; Klein et al. 2007; Marino 2018), rural areas such as the Inner Banks would be unlikely to receive funding for managed retreat and trends of individual moves for those who cannot adapt can be expected to continue to permeate the region.

As communities experience the slow shifts of climate change, they navigate their own adaptations outside the realm of infrastructure and municipal planning efforts. My findings suggest that ad hoc adaptations provide short-term protection from growing climate hazards, but have questionable long-term efficacy as sea levels rise and storm strength and frequency increases. Leaving communities and households to adapt on their own as climate hazards outpace institutional response requires residents to put their time and resources towards increasing their climate resilience. This process has real costs and places different burdens on those with different levels of socioeconomic resources. Some marginalized or vulnerable residents cut their losses – moving just far enough to be out of harm’s way. At the same time, a select number of residents with means can move ultimately out of the vulnerable area all together and avoid the costs of managing climate impacts. Without supporting communities experiencing climate change now, ad hoc adaptations will be a mechanism through which climate change exacerbates existing inequalities in climate stressed communities.

Notes

‘Soundside’ refers to the side of an island bordering the Pamlico sound. Similarly, ‘Oceanside’ refers to the side of the island closer to the Atlantic Ocean. Typically, soundside and Oceanside refer to whether a property is on the oceanside or soundside of NC Hwy 12.

Once a neighboring property adds fill or installs water protection water is then pushed onto lower lying neighboring properties until they similarly add fill or install a bulkhead or levee to the same height.

References

Adams, Helen. 2016. Why populations persist: Mobility, place attachment and climate change. Population and Environment 37 (4): 429–448.

Adger, W. Neil., Saleemul Huq, Katrina Brown, Declan Conway, and Mike Hulme. 2003. Adaptation to climate change in the developing world. Progress in Development Studies 3 (3): 179–195. https://doi.org/10.1191/1464993403ps060oa.

Aldrich, Daniel P., and Michelle A. Meyer. 2015. Social capital and community resilience. American Behavioral Scientist 59 (2): 254–269. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764214550299.

Bartram, Robin. 2023. Routine dilapidation: How homeownership creates environmental injustice. City & Community 22 (4): 266–285. https://doi.org/10.1177/15356841231172524.

Bates, Diane C. 2016. Superstorm Sandy: The inevitable destruction and reconstruction of the Jersey Shore. Rutgers University Press.

Brady, Alexander F. (Alexander Foster). 2015. Buyouts and beyonds : Politics, planning, and the future of Staten Island’s East Shore after Superstorm Sandy. Thesis. Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Bruch, Elizabeth, and Fred Feinberg. 2017. Decision-making processes in social contexts. Annual Review of Sociology 43 (1): 207–227. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-060116-053622.

Brunsma, David L., David Overfelt, and J. Steven Picou. 2010. The sociology of Katrina: Perspectives on a modern catastrophe. Rowman & Littlefield.

Carman, Jennifer P., and Michaela T. Zint. 2020. Defining and classifying personal and household climate change adaptation behaviors. Global Environmental Change 61: 102062. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2020.102062.

Castro, Brianna, and Raka Sen. 2022. Everyday adaptation: Theorizing climate change adaptation in daily life. Global Environmental Change 75: 102555. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2022.102555.

Cutter, Susan L., Bryan J. Boruff, and W. Lynn Shirley. 2003. Social vulnerability to environmental hazards. Social Science Quarterly 84 (2): 242–261.

Dawes, Philip L., and Jennifer Brown. 2002. Determinants of awareness, consideration, and choice set size in university choice. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education 12 (1): 49–75. https://doi.org/10.1300/J050v12n01_04.

Dawes, Philip L., and Jennifer Brown. 2005. The composition of consideration and choice sets in undergraduate university choice: An exploratory study. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education 14 (2): 37–59. https://doi.org/10.1300/J050v14n02_03.

Dunlap, Riley E., and Robert J. Brulle, eds. 2015. Climate change and society: Sociological perspectives. New York: Oxford University Press.

Elliott, Rebecca. 2018. The sociology of climate change as a sociology of loss. European Journal of Sociology 59 (3): 301–337. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003975618000152.

Emirbayer, Mustafa. 1997. Manifesto for a relational sociology. American Journal of Sociology 103 (2): 281–317. https://doi.org/10.1086/231209.

Fussell, Elizabeth. 2015. The long-term recovery of New Orleans’ population after Hurricane Katrina. American Behavioral Scientist 59 (10): 1231–1245. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764215591181.

Fussell, Elizabeth, Sara R. Curran, Matthew D. Dunbar, Michael A. Babb, Luanne Thompson, and Jacqueline Meijer-Irons. 2017. Weather-related hazards and population change: A study of hurricanes and tropical storms in the United States, 1980–2012. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 669 (1): 146–167. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716216682942.

Geertz, Clifford. 1983. Local Knowledge.

Goffman, Erving. 1974. Frame analysis: An essay on the organization of experience. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Gotham, Kevin Fox, and Miriam Greenberg. 2014. Crisis cities: Disaster and redevelopment in New York and New Orleans. Oxford University Press.

Hauer, Mathew E. 2017. Migration induced by sea-level rise could reshape the US population landscape. Nature Climate Change 7 (5): 321–325. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate3271.

Hauer, Mathew E., Sunshine A. Jacobs, and Scott A. Kulp. 2024. Climate migration amplifies demographic change and population aging. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 121 (3)e2206192119. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2206192119.

Hernández, Maricarmen. 2022. Putting out fires: The varying temporalities of disasters. Poetics 93: 101613. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2021.101613.

Hino, Miyuki, Christopher B. Field, and Katharine J.. Mach. 2017. Managed retreat as a response to natural hazard risk. Nature Climate Change 7 (5): 364–70. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate3252.