Abstract

Using student evaluations of teaching (SETs) as a quality assessment tool have long been a highly debated topic among both practitioners and scholars of higher education teaching. Rather than focus on whether SETs provide reliable measurements of quality, we explore what happens when SETs are implemented as or intended as quality development tools. We report from a qualitative study of how higher education teachers and managers perceive and use SETs as part of developing their own teaching, and focus on how the dialogue around teaching, which was intended as a part of the quality assessment procedure, is actualized (or not) in practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Quality in higher education has become a strategic priority both for higher education institutions (HEIs) and policy makers across Europe, not least because of the Bologna process and the increasing mobility of students, which has intensified the competition for students between nations and institutions. Quality in higher education is, however, an elusive concept (Harvey et al., 2010a, 2010b), and therefore also one that, in its broad sense, seems almost impossible to measure in a sensible way.

Despite this difficulty, many attempts have been made to operationalize and assess higher education quality (Harvey et al., 1993), and not least its sub-construct teaching quality (Crebbin, 1997; Ramsden, 1991). A common way to measure teaching quality in higher education is to use student feedback in the form of student evaluation surveys to evaluate teaching. Such feedback is often used: (1) as provision of feedback, useful for the improvement of teaching practices and programs, (2) as a means to provide recognition to teachers e.g. in relation to tenure and promotion reviews; and, (3) for research purposes e.g. in relation to learning, and educational performance (Clayson et al., 2011; Davies et al., 2007; Marsh, 2007; Wolfer et al., 2003).

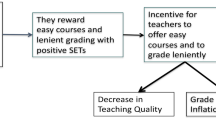

Student evaluations of teaching (SETs) are often collected at the level of programs, or more systematically throughout HEIs, and play, as mentioned above, an increasingly important role in many higher education systems. Some, however, argue that HEIs are misdirected in measuring satisfaction as a proxy for teaching quality (Barrie et al., 2008; Wolfer et al., 2003), e.g. because SETS are assumed to be influenced by other factors than instructional quality, such as the size of classes, study level, elective vs. prerequisite course, student competence, and grade expectation (Young et al. 2019). To the extent that SETs reflect underlying factors rather than teaching quality, it can be problematic for quality systems as SETs may influence decisions such as hiring and promotion.

In the Danish higher education system, which is the focus of the present paper, similar discussions of the usefulness of SETs have arisen, particularly in the wake of a reform of the funding system, which emphasized relevance and quality. In addition, the Danish national guidelines for institutional accreditation require systematic use of SETs, and that institutional quality assurance systems include the use of SETs to assess individual courses and educational programs (Danish Accreditation Institution, 2013). In many cases, SETs are also used in academic promotion cases.

For many years, however, the development of systems for SETs and the implementation of them, have remained idiosyncratic institutional practices, developed within universities and different disciplines - by individual teachers, and usually without reference to each other (Lassesen et al., 2013). In an attempt to break with this tradition, a joint system of SETs was in 2015/16 implemented at one of the largest Danish universities, with the aim of systematically collecting data on the student experience and using this data to enhance the quality of teaching in the university. The questionnaires used in this case focus on aspects of the student experience that are seen as measurable, linked with learning and development outcomes, and for which universities can reasonably be assumed to have responsibility.

In the present article, we report from an in-depth study of this case, in order to move beyond the discussion of whether SETs are a valid measure of quality and explore how/if SETs are perceived as a quality-development tool. We focus particularly on whether SETs are used as a facilitator of dialogue around teaching quality. To this end, we explore how higher education teachers and managers perceive and use SETs as a part of developing teaching.

Background

The evaluation of teaching is an important tool in creating a common dialogue and a shared sense of responsibility for ensuring satisfactory study programs (Ramsden, 1991). The students can help assess whether the teaching academically, pedagogically/didactically, and through its practical organization, provides an opportunity to develop the knowledge, the skills and the competencies contained in the learning objectives, and which will be honored at the exam. In a Danish context, however, SETs have often been used non-systematically and been dependent on individuals (Lassesen et al., 2013).

The present study explores how a systematic implementation of a system of SETs was received at the social science faculty at a Danish university. The SET system was implemented to include the students’ and teachers’ assessment of teaching in the ongoing quality assurance, the development of individual subject elements, as well as the academic profile of the educations. To this end, the expressed aim of the system was to (1) provide an overview of the course/courses as a whole and the ways in which its various elements are perceived to fit together (2) assess whether the teaching, academically and pedagogically/didactically, provides an opportunity to develop the knowledge, the skills, and the competencies contained in the learning objectives, and (3) support the university’s quality assurance policies (University, 2016). The evaluation is based on information contributed by the students through surveys, so that their experiences and ideas can be communicated, discussed, and documented. The questionnaires address issues like clarity of course expectations and requirements, the adequacy of the feedback, and perceptions of the quality of the teaching received, in terms of level, pace, and stimulation of interest.

A specific goal of the implementation of the SET system was to increase the dialogue around teaching, by establishing an “evaluation procedure, which involves the students, teachers, course coordinators, heads of study and boards of study in an ongoing, institutionalized dialogue about students’ learning and their perceived outcome of individual courses…” (University, 2016). This institutionalized dialogue is laid out in the recommended evaluation procedure, where it is emphasized that dialogue should take place both vertically: between students and teachers, and between teaching staff and leadership, as well as horizontally between teachers in the academic community. This dialogue is intended to ensure and incentivize communication with colleagues on educational issues; ability to contribute to the educational development and renewal of the study-program; ability to cooperate with colleagues and management in order to improve integration of courses and to improve progression in the educational program. The system does not prevent teachers from collecting feedback from students at other stages of the course, but is meant to ensure a minimal level of dialogue about teaching.

However, as mentioned in the introduction, SETs may also be used for other purposes, e.g. in connection with decisions on hiring and career progression, which might act as a hindrance to the desired dialogue about teaching. The present study, therefore, explores how teachers and leaders make sense of SETs as an instrument for quality development and how/if dialogue in practice is seen as an important component in this development.

Theory

In the present article, we use the theoretical perspective of sensemaking (Degn, 2015; Helms-Mills, 2003; Weick, 1995) in order to examine how teachers and managers make sense of the SET procedure and how they attempt to integrate it into their daily teaching practices. Sensemaking is based on the key assumption that individuals are continuously, but most often unconsciously, engaged in processes of creating meaning, as they are confronted with new and sometimes conflicting input. Because sensemaking processes often are unconscious, they are also empirically difficult to identify. However, in situations where individuals are confronted with uncertain or ambiguous input, sensemaking becomes more explicit. SETs may be seen as drivers/explicators of sensemaking, as they introduce uncertainty and sometimes ambiguity for teachers and managers, thus driving a need for reducing complexity; for making sense.

The process of sensemaking plays out as the selection of salient cues, which are then connected to a frame, which can be understood as a mental ‘scheme’ used to elaborate the cue and infuse it with meaning. Cues then represent what we pick out from an ongoing flow of information, e.g. events, certain characteristics, specific comments or utterings, and the frames are what we use to connect such cues and create a meaningful story out of events. These stories allows us to act, and once we act upon them, we enact this story into the world (Weick, 1995). By this enactment, we set the premises for future action, and thereby set our own sensemaking on a certain path. A key insight from the sensemaking perspective is that sensemaking processes are highly guided by identity construction; how we see ourselves directs our attention into specific trajectories and allows for certain paths of meaning making. Weick (1995) particularly highlights three “identity needs” as guiding mechanisms: the need for self-enhancement, the need for self-efficacy and the need for self-consistency (Erez et al., 1993).

The sensemaking perspective allows us to focus on how teachers and leaders pick out relevant cues about and from student evaluations, and how they piece together these cues to form plausible stories that enable action. It highlights, e.g., how the identity of teachers may influence the way they perceive the students and their evaluations, and also allows us to tease out the various ways in which institutional contexts may influence how SETs are understood, as it highlights how “sensemaking in organizations is strongly influenced by cognitive frameworks in the form of institutional systems, routines and scripts” (Helms-Mills, 2003). With the sensemaking perspective, we can explore how, e.g., departmental norms and cultures influence how dialogue and evaluation is perceived.

Methods and analytical approach

The paper is based on 32 semi-structured interviews with teachers and management within higher education. At the time of the interviews, all participants were employed at the Faculty of Social Sciences at a Danish university. The research approach sought to recognize that student evaluation of teaching practices are complex cultural activities embedded in institutional history and politics, and incorporate this complexity in the selection of informants.

18 teachers were interviewed for the project, and all but one had both teaching and research responsibilities. Recruitment of teachers ensured diversity in terms of gender, subject field, and whether participants were early career or senior staff (postdoc to full professor level). Further, 14 managers were interviewed. 10 of these were mid-level managers (Study Directors and similar), who also at the time of interviewing had some level of teaching responsibility, and four managers were from higher levels (Department Head and higher). Interview guides for both teachers, mid-level, and high-level management were structured around four common themes: Quality in education, view on the evaluation procedure, culture around evaluation, and the connection between evaluation and quality in education.

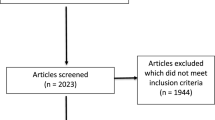

The data analysis was inspired by inductive grounded theory (Glaser et al., 1967) and had three stages. In the first stage, all interview transcripts were read, and common themes were registered and quantified. The second stage consisted of a first-order coding of all interviews, where excerpts were sorted into broad thematic categories derived from the interview guides e.g. management and evaluation, own evaluation praxis, challenges and how to improve. In order to investigate the dialogue practices in the field, select first order codes (see Figs. 1 and 2 below), which contained statements on practices around the evaluation, were further sorted into three dialogue-codes in the second order coding: Dialogue with students, dialogue between teachers, and dialogue with management. Within the second order coding, a sub-coding was made on facilitators and barriers for dialogue. First, all interviews with teachers were analyzed, then all with management. The two data-sets had different first-order codes, but due to a substantial overlap in the themes noted in the first stages, second-order and sub-coding codes were the same.

Analysis

In the following sections, the analysis is presented, which explores if, and under which circumstances, the evaluation tool and procedure facilitates dialogue about quality development between different groups. Further, a specific aim is to examine not only whether a dialogue exists, but also the purported contents of it.

Vertical dialogue: HE teachers and management

A majority of both teachers and management interviewed for the project describes dialogue between teachers and management as primarily happening in response to poor evaluation results. If the evaluation of a course either falls below a certain threshold, or at some departments is close to being below the threshold, managers responsible for teaching activities (Directors of Study) will initiate some sort of contact with the teacher(s) of a course. Either teachers are to provide a written account of how they plan to improve the course, or a dialogue is initiated. As one female professor puts it:

(…) but I have no doubt that the Director of Studies has also used it. (…) That some have been… what to say. Had a chat and the possibility to expand upon [the results of the evaluation]. And of course also, I do not know for sure but, been offered supervision, courses on teaching, so also been lifted up professionally.

Teacher, female professor

Both some managers and some teachers characterize dialogues prompted by poor SET results as a situation where management can offer teaching resources such as supervision, or courses on teaching. These courses are often provided by outsiders and are seen as a tool to be used by the Directors of Study, since they don’t necessarily know how to personally help teachers improve their teaching, or they express not being able to do much, as they do not have direct staff responsibility and thus ‘limited power’ over teachers. The content of this type of dialogue thereby is focused on enhancing teaching by way of offering “outside assistance”.

Relatively often, however, the “poor-results-dialogue” is related as a sort of ‘defense for the results’, e.g., the teacher describing how different circumstances have affected the results in negative ways.

And often, there are good explanations, right. A change of text book, or a whole new team of teachers, or a new subject. Or “we had seven times where class was moved because” or “last fall we had ten times where we could not hear what was said, because there was construction work outside”. So, it can be all sorts. And so far, I have only seen good explanations for it [poor SET results].

Manager, male director of study

As seen in this excerpt, these circumstances can be organizational: lectures happening in suboptimal environments or at less desirable times of day. But circumstances can also be student-based, e.g., the evaluation results reflecting the inability or unwillingness of students to ‘accurately’ assess the teaching quality, and some managers mention personal problems, e.g., a teacher feeling stressed, as a factor that can affect teaching and subsequently SET results.

With the sensemaking perspective, we may see this as an attempt to make sense of a situation which is not as one expected. The cues that are picked out and used in the sensemaking narrative are the circumstances, such as the students’ ability to assess ‘properly’, or the organizational explanations as seen above. Interestingly, we see that the managers’ sensemaking seem to align with the sensemaking of the teachers (like in the quote above, where they are valued as good explanations).

While most departments only initiate teacher-management dialogue based on poor evaluation results, some managers also practice noticing and applauding good evaluation results.

Interviewer (I): But, you do not have for example a dialogue with your Director of Studies about evaluations?

Teacher, female assistant professor: No, not besides that he came around last year and said well done. And that was sweet of him of course, but otherwise, no.

However, as this quote shows, these interactions, while pleasant for the teachers, are mostly made sense of as being about recognition and accolades, rather than as something which inspires action, e.g., initiating an ongoing dialogue about how to hone and harvest the skills of accomplished teachers.

The overall focus on evaluation results and teaching as either ‘poor’ or ‘great’ and thus as sites for correction or accolades rather than development, could be a consequence of the dual function of the SETs, namely that they work both as a quality development tool and a quality assessment tool. The dual functions provide the teachers and managers with multiple types of cues to make sense of and as seen in the quote below, stemming from a Director of Study, the story of “being a pawn in a system” is also constructed:

But this thing about feeling like you are just a pawn in a system where you have to generate some numbers. And then you had to hand in something written if you did not meet the criteria. That has not been a process that inspired to… think about something [in relation to teaching].

Manager, female director of study

We see here that ‘the generation of numbers’ and ‘the system’ are picked out as cues that help this Director of Study make sense of the procedure. When applying these cues, the dialogue is framed in a particular way (as providing something written and, implicitly, as defending bad results), and quality development is not seen as part of this.

The double function of SETs also seems to frame dialogue in other ways. In some departments, the interviewees describe how dialogue becomes a sort of ‘meta-dialogue’ about the usefulness of the evaluations, rather than the results of the evaluations.

Well it is something that is actively discussed. In part, we have had this whole continuous discussion of these evaluation-regimes, for more or less all the years I have been here. I believe we have changed the system and forms multiple times. (…) but of course also, this thing with… evaluations as a quality indication, is something that is continuously discussed.

Teacher, male professor

From a sensemaking perspective, it is interesting how these discussions between teachers and management, and/or more loosely ‘departmental discussions’, are framed as being about the practice of evaluating rather than the “content” of the evaluation. The sensemaking framework works with the basic assumption that sensemaking is stabilizing, i.e. that individuals will choose cues that align with the existing mental schemes and meaning structures (Weick, 1995). This might help understand why teachers in this study tend to emphasize the more general discussion of ‘evaluation-regimes’, rather than the specific content of evaluations. Similarly, as the quote above indicates, the interviewees tend to connect this to an ongoing, institutionalized practice (we have had this discussion for years), thereby limiting the need to change practice. This tendency to frame the discussion as a ‘meta-dialogue’ seems to be connected to teachers’ experiences of ‘being controlled’ or the evaluation functioning as a sort of ‘exam situation’, where teachers are assessed as being either good or bad at teaching.

Horizontal dialogue: Colleagues in HE

When looking at how dialogue between colleagues is described, we see that the extent of dialogue about evaluation results between teachers varies from department to department. The general perception is that when dialogue occurs, it is often reliant on an individual or smaller group of people initiating discussions.

I: But, is it an institutionalized dialogue, this thing where you have meetings in the course teaching team, where you discuss…?

Teacher, male postdoc: No, well it is not institutionalized for the department as a whole. Not at all. It is something the individual course managers completely independently, and well at some courses, you do that. At those courses, you have a culture, and some culture bearers who make it so: “Well, this is just how we do”. At other courses, it does not happen automatically.

In this quote, dialogue between colleagues is made sense of as something that is dependent on culture and culture bearers, i.e. individual teachers, or a group of teachers, decide to share their evaluation results or discuss how to transform feedback from the evaluation into teaching initiatives, which then fosters a dialogue in specific course teams. At some departments, interviewees describe how these individual initiatives create small sub-environments, where dialogue is present and ongoing, and in other places how individuals push for more departmental initiatives focused on fostering a dialogue about how to improve teaching.

However, similarly to the previous section about the vertical dialogue, some of the sensemaking narratives also emphasize ‘established dialogue cultures’ as an ongoing, institutionalized practice, when describing how SETs and the SET system is used. Several teachers describe how they already have ‘a culture’ of sharing and discussing evaluation results. Often this is described in connection with the enactment of other evaluation initiatives, e.g., special fora where teachers, management and students get together and discuss courses, or other evaluation surveys that they also distribute, thereby making sense of the faculty’s evaluation procedure as ‘just another tool in the toolbox’. In this way, the informants draw on existing frameworks and practices to make sense of the instrument.

I: Do you use the evaluation when you talk in the team of teachers? Often there are several teachers for the same course, or at least there is sometimes. (…)

Teacher, male professor: You could probably do that, but I actually think when we talk about something like quality in education, it is more having some seminars where we discuss teaching modes and things that work, things that does not work as well, bring up some examples of new ways of going about it. A lot more than it is actually about using the evaluations.

At departments where dialogue about how to improve teaching is seen as ongoing, the faculty’s SET procedure is not used in the sensemaking narratives as a facilitator of dialogue – more often teachers and management pick out cues such as other evaluation tools or fora where other forms of dialogue between students and management or students and teachers take place.

In the narratives where dialogue is not seen as directly dependent on enterprising individuals or long-established cultures of quality development discussion, it is often described in connection to courses where a team of teachers lecture together or alternating, rather than a course run by a single teacher. In these narratives, close personal ties between colleagues, or at least close collegial relations, as well as teaching teams that are interdisciplinary (crossing department or faculty lines) or comprised of both university and non-university teachers are used as cues, that explain the dialogue, e.g. as seen in the quote below:

I: This process you are describing, where you [as a team] discuss at multiple levels – is it your impression that it is something people do? Or is it just something you do? (…)

Teacher, female assistant professor: I think it is something we do, because well, we teach together. Most people run their own course, so they are on their own with it (…).

What the quote also alludes to, is that many teachers, especially the ones who run a course alone, describe that they do not discuss their evaluation results with other teachers. In the narratives, we see several different ways of making sense of this lack of discussion: some pick out cues such as a lack of formal structures where a dialogue can be initiated, and some of the teachers also explain the lack of a dialogue by referring to a feeling of evaluation results being sensitive or somehow ‘private’. From a sensemaking perspective, this could be understood as ways of maintaining a favorable sense of self – a key driver in sensemaking processes (Weick, 1995). As mentioned earlier, individuals tend to pick out cues that allow them to maintain a positive self-image, and it seems that making sense of evaluations as private, would allow teachers to protect themselves from the risk of dealing with a negative self-image. We see in the interviews that even very favorable evaluation results are not discussed, which emphasizes this narrative of evaluations as private.

The unwillingness to discuss evaluation results also seems to be exacerbated by a very prevalent narrative of comments from students that are unconstructive, personal, or mean:

Well it is not something I myself would want to discuss with others. It really is not, and damn I do not think the others feel like that either. Not when it is loaded with such as … well a bunch of crap, into one such survey. Everything… it is… And I do not know, I do not quite know what should come of it [discussing results with colleagues] either.

Teacher, male associate professor

This narrative about the comments from the students also affects the content of the dialogue between teachers. Dialogue is sometimes described as centered on how to handle the evaluation results, rather than on how to transform evaluation results into improved teaching practices. This type of dialogue is focused on collective ‘identity maintenance’, i.e. how to handle low evaluation scores without it affecting your professional confidence, or how to handle comments from students that come in the form of, or at least feel like, personal attacks.

I: do you remember what you talked about there [at a departmental seminar on evaluation]?

Teacher, female assistant professor: Yes I can, because I was completely coincidentally put in the group where there was a mix of everyone from PhD students to some of the most long-established professors in this places. And some of what we talked about was… well how you handle the results, not scientifically, but how you handle the results personally (…).

This sort of instructional relationship between senior and junior staff, where professors and other advisors help PhD students not ‘take comments personally’ is stressed by teachers as especially important, and in some interviews is the only dialogue mentioned to take place.

Vertical dialogue: students and teachers

While interviews with teachers on their dialogue with students revealed, similarly to the other forms of dialogue, varied practices, more teachers were aware that a dialogue with students was supposed to happen.

Interviewer: (…) do you usually hold an oral follow-up on the evaluation? Or do you evaluate on the last class?

Teacher, female assistant professor: (…) But no, I do not. I could of course, but I actually have a hard time seeing – I do know that they recommend that we do it – but I have a hard time figuring out what to say.

As seen in this excerpt, it varied, whether the dialogue did happen, but teachers had more knowledge or awareness of the intended dialogue, even when they did not adhere to the guidelines themselves. The greater awareness could explain why dialogue between teachers and students was more prevalent than dialogue at other levels.

What then facilitates this dialogue, and what is discussed? Teachers most often describe using the dialogue as a way to get students to elaborate their feedback or critiques, or as a way to get the feedback in a ”more constructive” form. This either means a form of feedback where the focal point is alternative solutions to encountered problems rather than ‘just’ pointing out problem areas, or a feedback that is less harsh, i.e., formulating feedback or critique in ways that teachers find less uncomfortable. This practice is thereby very much in line with the intentions of the instrument.

Well I think it has been fine – so far at least. It is the place where you can, well what is written in text form can be misunderstood, if you read between the lines in erroneous ways. So I think it is at least as important, both for the students to get some feedback on what we might change, but also we can ask: What do you more precisely mean by this? And then get a feel for, okay out of forty students, is it one person saying this or…?

Teacher, male associate professor

As seen in this quote, some teachers also use the dialogue about the evaluation results to assess the prevalence of a critique. Is it only one or a few students, or is it a majority experience? Similarly, as this teacher, some also use the dialogue to let the students know that their feedback will be taken into consideration when planning the next iteration of the course.

While a lot of the dialogue is then (mostly) aimed at operationalizing the feedback, or fostering a better relationship between students and teachers, some of the dialogue is centered on structural limitations or managing expectations.

You can sort of be allowed to answer back a little, or at least explain well: “Why do we not have more exams to practice?” – “Well, because there haven’t been anymore exams”. “Well then why do you not make some?” – “Because resources have not been allocated for that, so you’ll have to complain higher up”. So those kinds of things. It is quite okay to have the talk with them, most of them are actually very understanding.

Teacher, female assistant professor

In this quote, the teacher is both explaining why she cannot meet expectations, and discounting feedback on structural issues as, e.g., the time she has to prepare is (experienced as) outside of her power. A few teachers explained how they use the dialogue to let students know ‘the way of things’, e.g., how many hours they are expected to use to prepare for class, that their comments are (at least for the teacher) unacceptable, or that their demands are unreasonable. While the majority of teachers have some sort of dialogue with students about evaluation results, some also choose to forego dialogue. This seems to be motivated either by lack of time, the temporal placement of the dialogue, or by the teachers’ experience with and/or view of student feedback in the evaluation survey.

Looking at how the teachers make sense of non-dialogue, several teachers use structural conditions to construct a narrative: having a dialogue about the evaluation results with students takes time away from teaching activities in an already densely packed course. The sensemaking then becomes about using the time they have on teaching. This sentiment on the dialogue taking time away from teaching is also shared by some of the teachers that describe actually having a dialogue with their students about the evaluation results.

Some of what I think is challenging is, well of course PARTLY taking time from a very, very sparse teaching, because we do not have that many hours, but that is what it is. But partly, it comes too late in the course, we are missing some sort of halfway evaluation, if there were things that need to be adjusted. A least if you should use it that way.

Teacher, female assistant professor

More than taking away time from teaching, many of the teachers also express that the temporal placement of the dialogue is a factor in why they do not have a dialogue. The dialogue about evaluations is to be held before end of the semester, meaning the feedback can only be applied the next time the course will run, with different students in attendance. The students giving the feedback will then not benefit from any changes to the course. For this reason, many teachers see a dialogue at the end of the semester as superfluous. A number of them react to this by doing some sort of dialogue with students at the midway point of a course, either as a supplement to or a replacement of, the end-of-semester dialogue. This midway point dialogue is not made sense of as part of the SET system and procedure.

Another way of making sense of avoiding a dialogue about evaluation results with students is to use the students’ ability to provide feedback as a cue. Some teachers construct a strong narrative about student feedback as not being particularly useful for improving teaching in ways that optimize learning outcome, and SET results are often described as being a measure of arbitrary student satisfaction, rather than constructive comments. Another strong narrative, also mentioned above, is the one about the proliferation of (myths of) harsh comments in evaluations:

Teacher, male associate professor: I do not think I would do it either [if he had time]. Because those comments, they are simply too… there is a lot of those comments that they give, which are simply to disgusting… for that to be something I want to do.

I: okay so it is… garbage?

Male associate professor: Yes, complete garbage. I simply do not want to do that… I absolutely do not want to discuss it with them. I damn well do not want to do that.

In the interviews, the teachers and managers describe the actual proliferation of personal attacks in evaluations very differently, and it is therefore difficult to assess how prevalent these harsh comments are. However, the narrative of “mean student comments” is quite strong, and these actual or mythical mean comments from students, indeed seems to discourage dialogue with students, and, as seen in the previous section, also the dialogue between colleagues. It should be mentioned that a number of teachers also mention that the comments are the most useful part of the evaluation, but this is not seen in connection with descriptions of dialogue – the usefulness of comments are thus primarily connected with private reflection on one’s own teaching, not as a facilitator of dialogue with the students or colleagues.

Discussion

In this paper, the aim was to explore how/if a systematic procedure of SETs is perceived as a quality-development tool, particularly focusing on their potential for working as a facilitator of dialogue on teaching practices. In this final discussion, the most important findings will be re-iterated and discussed in relation to the existing literature on SETs.

Institutionalized practices

One key finding of the analysis, which warrants further discussion is the strong institutionalized practices that exist at local levels, which seem to work against the implementation of a more systematic evaluation regime. The analysis of the interviews – seen as sensemaking narratives – has demonstrated that dialogue around teaching practices does indeed happen in many cases, but that facilitating such a dialogue is a very difficult and complex task. Looking at the dialogue between different stakeholders has allowed us to explore how sensemaking processes tend to favor existing practices, rather than incorporate SETs as a driver of new cues and changes in practices. Indeed, it has revealed that particularly these institutionalized practices tend to frame the sensemaking in certain ways and allow the teachers to make sense of the faculty’s evaluation procedure as ‘just another tool in the toolbox’, rather than ‘the official procedure’. The sensemaking perspective highlights how individuals tend to apply existing frames when making sense of a new situation (Weick, 1993), rather than adopt new and radically different meanings. This helps us understand why teachers in this study do not seem to include the new SET instrument as a salient cue in their sensemaking – they simply don’t see the need, because they can apply their existing frames and cues.

“Mean comments” and the private nature of teaching

Another main finding of the analysis is the influence the narrative of “mean comments” from students has on the willingness of teachers to engage in dialogue. This echoes a discussion in the literature on the ability of students to evaluate teaching fairly and constructively. It has been argued that students cannot assess what exactly good teaching is due to their lack of knowledge in a specific discipline (Marsh, 2007). According to Gravestock and Gregor-Greenleaf (2008), this especially concerns issues regarding level and accuracy of course content, teacher’s knowledge, or competency in her or his subject. Also, students may have different perceptions of what constitutes good teaching (Davies et al., 2007), and studies show systematic variations between subject areas, i.e. that students from different disciplines differ with respect to what they perceive as important and how they view their learning environment.

Our study indicates that the teachers’ willingness to use SETs as an instrument for quality development is highly influenced by these perceptions of the students, and additionally the fear of mean comments. As mentioned in the analysis, it is debatable whether these comments are mostly mythical, but there seems to be little doubt among the interviewees that the narrative is quite prevalent.

This perception of the students as unreliable evaluators and the fear of personal or mean comments also relate to the perception of teaching as a private enterprise. These two sensemaking narratives complement and reinforce each other and seems to discourage dialogue with students and between colleagues. We have highlighted that this can be understood as a way of maintaining a favorable sense of self and allowing teachers to protect themselves from the risk of dealing with a negative self-image. This may, however, also be detrimental to the use of SETs as a quality development tool. Several studies have paid attention to the role of scholarly communities in supporting and constraining teacher development and educational change, e.g., Lave et al. (1991) who state that new teachers, in particular, can learn and develop educational practices if they experience legitimate peripheral participation in a community of practice. Moreover, it has been suggested that pedagogical practices should be developed more systematically through dialogic social learning activities among the academic staff (Warhurst, 2008), but this endeavor may be quite difficult due to the intertwinement of the narratives mentioned above.

The double function of the instrument

A final finding, which warrants further discussion is the implications of an instrument which functions both as a quality development tool and a quality assessment tool. In the literature, it has been argued that the combination of improvement and administrative purposes in SETs may cause challenges. For many teachers for whom standardized feedback is new, there may be a suspicion or even a fear that such feedback could be used for other purposes (Gravestock et al., 2008). It has been argued that using the same evaluation process for both personal and administrative purposes undermine the usefulness of some instruments (such as self-evaluation), and creates an additional burden on evaluators as their decisions have somewhat conflicting consequences (e.g. tension between improving performance by identifying weaknesses and limiting career progression) (ibid.). Furthermore, the development of university teaching has traditionally been seen as an individual effort; good practices (or less good) are not shared (Stenfors-Hayes et al., 2010). The present study supports this and adds nuance, by highlighting how the symbolic aspects of the instrument (feeling like a pawn in the system) also works against the expressed goal of the instrument. It is thereby not only the fear of repercussions in relation to careers etc., but also a more fundamental disagreement that emerges as an obstacle in using SETs.

Concluding remarks

In this study, we have explored the barriers and enablers of SET-facilitated dialogue as a tool for developing teaching quality. We have demonstrated how institutionalized cultures, strong narratives questioning the usefulness of the evaluations and the ambiguity of the instrument challenge the potential of SETs as a facilitator of dialogue. We have discussed how these findings align with existing literature, but also how it adds nuances to this by highlighting the sensemaking mechanisms involved in the interpretation of a systematic approach to quality development. Our findings thereby point to the need to take these sensemaking frames and mechanisms into account, both in the design and implementation phases of such an instrument.

References

Barrie, S., Ginns, P., & Symons, R. (2008). Student surveys on teaching and learning. Commisioned Report ALTC Teaching Quality Indicators Project, 99–101.

Clayson, D. E., & Haley, D. A. (2011). Are students telling us the truth? A critical look at the student evaluation of teaching. Marketing Education Review, 21(2), 101–112.

Crebbin, W. (1997). Defining quality teaching in higher education: An Australian perspective. Teaching in Higher Education, 2(1), 21–32.

Danish Accreditation Institution (2013). Guide to institutional accreditation.

Davies, M., Hirschberg, J., Lye, J., Johnston, C., & McDonald, I. (2007). Systematic influences on teaching evaluations: The case for caution. Australian Economic Papers, 46(1), 18–38.

Degn, L. (2015). Identity constructions and sensemaking in higher education–a case study of Danish higher education department heads. Studies in Higher Education, 40(7), 1179–1193.

Erez, M., & Earley, P. C. (1993). Culture, self-identity, and work. Oxford University Press.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The Discovery of Grounded Theory; Strategies for Qualitative Research.

Gravestock, P., & Gregor-Greenleaf, E. (2008). Student course evaluations: Research, models and trends. Citeseer.

Harvey, L., & Green, D. (1993). Defining quality. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 18(1), 9–34.

Harvey, L., & Williams, J. (2010a). Fifteen years of quality in higher education. In: Taylor & Francis.

Harvey, L., & Williams, J. (2010b). Fifteen years of quality in higher education (part two). In: Taylor & Francis.

Helms-Mills, J. (2003). Making sense of organizational change. Routledge.

Lassesen, B., Thomsen, H. K., Birkmose, H. S., Kristensen, K. M., Pedersen, J. G., Henriksen, K., & Andersen, N. B. (2013). Forslag til etablering af fælles mål for undervisningsevaluering på Aarhus Universitet. Retrieved from: http://pure.au.dk/portal/da/activities/arbejdsgruppen-til-etablering-af-faelles-maal-for-undervisningsevaluering-paaau(da698b12-4c2d-41a4-81c9-6431158f4476).html

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press.

Marsh, H. W. (2007). Students’ evaluations of university teaching: Dimensionality, reliability, validity, potential biases and usefulness. The scholarship of teaching and learning in higher education: An evidence-based perspective (pp. 319–383). Springer.

Ramsden, P. (1991). A performance indicator of teaching quality in higher education: The Course Experience Questionnaire. Studies in Higher Education, 16(2), 129–150.

Stenfors-Hayes, T., Weurlander, M., Dahlgren, O., L., & Hult, H. (2010). Medical teachers’ professional development–perceived barriers and opportunities. Teaching in Higher Education, 15(4), 399–408.

University (2016). 3 references removed to ensure the integrity of the peer review process.

Warhurst, R. P. (2008). Cigars on the flight-deck’: New lecturers’ participatory learning within workplace communities of practice. Studies in Higher Education, 33(4), 453–467.

Weick, K. E. (1993). The collapse of sensemaking in organizations: The Mann Gulch disaster. Administrative Science Quarterly, 628–652.

Weick, K. E. (1995). Sensemaking in organizations (Vol. 3). Sage.

Wolfer, T. A., & Johnson, M. M. (2003). Re-evaluating student evaluation of teaching: The teaching evaluation form. Journal of Social Work Education, 39(1), 111–121.

Young, K., Joines, J., Standish, T., & Gallagher, V. (2019). Student evaluations of teaching: the impact of faculty procedures on response rates. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 44(1), 37–49.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Aarhus Universitet. This work is part of the project Pathways to Improve Quality in Higher Education (PIQUED), which was supported by the Danish Agency for Science and Higher Education under Grant 7118-00001B..

Open access funding provided by Aarhus Universitet

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Søndergaard, M.K., Degn, L. & Lassesen, B. Thinking or talking about teaching? Student evaluation as an occasion for dialogue or reflection on teaching. Tert Educ Manag (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11233-024-09140-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11233-024-09140-7