Abstract

In learning journals, prompts were shown to increase self-regulated learning processes effectively. As studies on effects of long-term prompting are sparse, this study investigates the effects of prompting cognitive and metacognitive self-regulation strategies short-term and long-term in learning journals on learners’ strategy use, self-efficacy, and learning outcome. Therefore, 74 university students kept a weekly learning journal as follow-up course work over a period of eight weeks. All students’ learning journals included prompts for a short-term period, half of the students were prompted long-term. While self-efficacy was assessed via self-reports, strategy use was measured with self-reports and qualitative data from the learning journals. Learning outcomes were assessed via course exams. Short-term prompting increased self-reported cognitive and metacognitive strategy use, and the quantity of cognitive strategy use. Yet, it did not affect self-efficacy, which predicted the learning outcome. Irrespective whether prompting continued or not, self-reported cognitive and metacognitive strategy use, and self-efficacy decreased. Qualitative data indicate that the quantity of learners’ cognitive strategy use kept stable irrespective of the condition. The results indicate that short-term prompting activates cognitive and metacognitive strategy use. Long-term prompting in learning journals had no effect on strategy use, self-efficacy, and performance. Future research should investigate possible enhancers of long-term prompting like feedback, adaptive prompts or additional support.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Self-regulated learning is important in learning situations that offer high degrees of freedom to learners, like university settings (e.g., Cassidy, 2011). One possibility to enhance students’ self-regulated learning activities are learning journals including prompts (Bangert-Drowns et al., 2004; Berthold et al., 2007). Learning journals are instructional means to reflect upon the learning process and its outcomes (Bangert-Drowns et al., 2004; Fabriz et al., 2014; Schmitz & Wiese, 2006). Externalizing what is learned can help learners to further develop their thoughts as well as to recognize possible knowledge gaps. Beside fostering the cognitive processes learning journals can also be used to reflect on the learning process itself. This metacognitive function of learning journals can stimulate self-regulated learning activities. However, as suggested by many prior studies (for an overview see Nückles et al., 2020) instructional support is needed to unfold the potential of learning journals. Nückles et al. (2020, page 1102) summarize that “journal writing without instructional support resulted in almost absent metacognitive strategies and clear deficits in the use of cognitive strategies. Prompts can be used to address such deficits.”

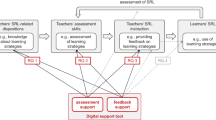

Prompts additionally stimulate self-regulation activities and activate learners to engage in productive self-regulated learning processes (Bannert & Reimann, 2012; Hübner et al., 2006). Enactive self-regulated learning processes stimulated by prompts were shown to increase learners’ performance (e.g., Berthold et al., 2007). Through this, prompting cognitive and metacognitive self-regulation strategies should also affect learners’ self-efficacy: When learners experience that their intensified use of strategies for self-regulated learning is effective, they can attribute their success to their own effort, what makes them feel self-efficacious (Komarraju & Nadler, 2013). Self-efficacy as a motivational variable is included in many models of self-regulated learning. Yet, studies are lacking which investigate the effects of learning journals including prompts on motivational variables of self-regulated learning. Additionally, while many studies investigate the effects of prompts in learning journals within one learning session only, there has been little research on the effects of long-term prompting on learners’ self-regulated learning and learning outcomes. A teacher may wonder how long students need the instructional support of prompts for effective journal writing and hence for self-regulated learning. She could decide to use learning journals including prompts over the whole course to stimulate students’ self-regulated learning activities or to include prompts in single learning journals only. Therefore, the overall research question of the present study is to investigate the effects of short-term and long-term prompting in learning journals on learners’ strategy use, the motivational variable self-efficacy, and learning outcomes.

In the following, self-regulated learning will be introduced as a theoretical framework for the present study. Cognitive and metacognitive learning strategies as well as the motivational variable self-efficacy will be explained more deeply as these variables are not only important for self-regulated learning but are particularly in the focus of the present study. On this theoretical basis, learning journals with prompts will be introduced as means to stimulate self-regulated learning processes. The introduction will be complemented by empirical findings on the effects of learning journals with prompts on learners’ strategy use, motivation, and learning outcomes. Based on this, the current research gaps will be identified. To fill the existing research gaps, our hypotheses and the research design of the present study be outlined.

Self-regulated learning

Self-regulated learning is a theoretical framework which has evolved during the last five decades. It was developed to integrate cognitive, metacognitive, emotion-affective, and motivational aspects of learning. Models of self-regulated learning often highlight either the structure (Boekaerts, 1999) or the dynamic processes of self-regulated learning (Panadero, 2017; Schmitz & Wiese, 2006; Zimmerman, 2005).

Following Zimmerman, self-regulation “refers to self-generated thoughts, feelings, and actions that are planned and cyclically adapted to the attainment of personal goals” (2005, p. 14). Zimmerman (2005) describes self-regulated learning as a cyclical process including three phases: forethought, performance, and self-reflection. During forethought, task analysis including goal setting takes place. Further, the learning process is planned, and cognitive learning strategies are selected. These cognitive learning strategies are applied in the performance phase to study the learning contents. The learning progress is monitored to compare the current state to its learning goal. In the self-reflection phase, the learning process is judged and regulation strategies are selected to adapt the learning process to achieve the desired goal. This results in affective reactions and consequently influences self-motivational beliefs (e.g., self-efficacy) and task analyses in future forethought phases. Therefore, self-regulated learning is a process which unfolds over time as previous learning experiences influence future learning processes within and across learning situations (Zimmerman, 2005). The Zimmerman (2005) model serves as a basis for the present longitudinal study since it allows not only to investigate the development of self-regulation over time in a university course but also to investigate effects on the development of cognitive, metacognitive, and motivational components as a consequence of short-term and long-term prompting.

Components of self-regulated learning

Zimmerman’s (2005) self-regulation model equally combines cognitive, metacognitive, emotion-affective, and motivation components. These components are also present in other models of self-regulated learning (e.g., Boekaerts, 1999; Schmitz & Wiese, 2006, for an overview see Panadero, 2017).

Since Zimmermans’ and many other models highlight the importance of cognitive and metacognitive learning strategies for self-regulated learning (Boekaerts, 1999; Panadero, 2017; Schmitz & Wiese, 2006; Zimmerman, 2005), the role of learning strategies will be explained further. Moreover, motivational variables, and in particular self-efficacy, are often included in self-regulation models since self-efficacy influences the selection of learning strategies and learning outcomes (Diseth, 2011; Efklides, 2011; Greene et al., 2004; Panadero, 2017; Sitzmann & Yeo, 2013). Therefore, the role of self-efficacy for self-regulated learning will also be explained in more detail.

Cognitive learning strategies Cognitive learning strategies aid learning by facilitating deep-level processing of the learning contents and knowledge construction (e.g., Chi, 2009; Mayer, 2009; Roelle et al., 2017). In their taxonomy of learning strategies, Weinstein and Mayer (1983) identified three cognitive learning strategies: rehearsal, organization, and elaboration. Rehearsal strategies deal with repeating the learning contents, e.g., through re-reading. Organization strategies aim at identifying important aspects of the learning contents and structuring them meaningfully. Mayer (1984) regards the organization of learning contents as “building internal connections” since logical connections between parts of the learning contents are being built. Elaboration strategies support learners’ integration of the learning contents and can be described as building external links, i.e., links between the learning contents and other information outside the learning contents (Mayer, 1984). Thus, elaboration strategies include linking new learning contents to ones’ prior knowledge or finding examples for given concepts. In sum, cognitive learning strategies enable deep comprehension of new learning contents and storage in memory to retrieve the information when needed. Consequently, cognitive learning strategies are important predictors of learning outcomes (Dent & Koenka, 2016).

Metacognitive learning strategies Metacognitive learning strategies aid learners to actively regulate and control the cognitive learning processes (De Bruin & Van Gog, 2012; Efklides & Vauras, 1999; Flavell, 1979; Roelle et al., 2017). Metacognitive processes involve planning, monitoring and regulation. In the planning phase, when learners are exposed to a learning situation, they set up their learning goal. To achieve this goal, learners engage in planning activities like selecting cognitive learning strategies. In the performance phase, learners monitor their learning process with respect to their learning goal. When gaps between learners desired learning goal and their current state are identified, regulation strategies are applied. Finally, learners current state should match their desired goal state. Highlighting the importance of metacognition for self-regulated learning, metacognitive strategies are found in all phases of Zimmerman’s (2005) self-regulation model. Moreover, they influence other components of self-regulated learning and learning outcomes (Dent & Koenka, 2016; Efklides, 2011; Vrugt & Oort, 2008).

Self-efficacy Self-efficacy is a well-known motivational factor (Murphy & Alexander, 2000) and part of the motivational variables found in many models for self-regulated learning (Efklides, 2011; Zimmerman, 2005). Self-efficacy refers to “beliefs in one’s capabilities to organize and execute the courses of action required to produce given attainments” (Bandura, 1997, p. 3). In the present study, we conceptualize self-efficacy as the belief in one’s capabilities regarding the successful completion of a university course and thus we investigate how self-efficacy develops over several weeks in a university course setting when being prompted while studying.

Being influenced by Bandura’s (1986) social-cognitive perspective, self-efficacy is included as one of the variables of forethought in Zimmerman’s self-regulation model (2005). Self-efficacy affects central self-regulation processes and learning outcomes (Diseth, 2011; Greene et al., 2004; Sitzmann & Yeo, 2013; Wäschle et al., 2014). During forethought learners form assumptions regarding their self-efficacy with respect to a specific learning goal. Believing to be capable to achieve a learning goal influences learners’ motivation to engage in the learning process (Greene et al., 2004). Highly self-efficacious learners will apply deep level cognitive and metacognitive learning strategies in the performance phase to accomplish the learning task (Diseth, 2011; Moos, 2014; Moos & Azevedo, 2009). Confronted with obstacles, the belief to be able to achieve the learning goal will influence learners’ persistence and vigor until succeeding in the task (Bandura, 1997; Komarraju & Nadler, 2013). Consequently, learners’ self-efficacy was identified to influence learning outcomes positively (Honicke & Broadbent, 2016; Sitzmann & Ely, 2011; Talsma et al., 2018).

When evaluating their learning process, highly self-efficacious learners will experience high goal achievement. These experiences of goal achievement and mastery will in turn influence learners’ self-efficacy in future learning tasks (Wäschle et al., 2014). Following Bandura (1997), experiences of mastery achievement represent a major source influencing learners’ self-efficacy since they provide authentic real-life evidence of learners’ capabilities. As a form of mastery, self-efficacy can be influenced by high degrees of perceived goal achievement (Wäschle et al., 2014; Williams & Williams, 2010), learning outcomes (Sitzmann & Yeo, 2013; Talsma et al., 2018), and enactive self-regulation (Bandura, 1997). Experiencing previous learning processes as successful heightens learners’ self-efficacy, while experiences of failure lower learners’ self-efficacy. As a consequence of these self-regulation processes, self-efficacy is in turn affected by them (e.g., van Dinther et al., 2011). Yet, intervention studies showed that multiple and successive experiences are needed to affect learners’ self-efficacy (e.g., van Dinther et al., 2011, Gentner & Seufert, 2020). This supports the theoretical assumption that self-efficacy perceptions develop over time (Bandura, 1997; Chen & Usher, 2013; Usher & Pajares, 2008).

Self-regulated learning and learning outcomes

Across learning situations, self-regulated learning was identified as an important factor influencing learning outcomes (Dent & Koenka, 2016; Panadero, 2017; Sitzmann & Ely, 2011; van der Graaf et al., 2022). This highlights the importance of self-regulation for learning outcomes, a relationship that we will also investigate in the present study. However, students show difficulties in applying effective cognitive and metacognitive learning strategies during learning which results in comprehension problems and diminished learning outcomes (Azevedo, 2009; Chi et al., 1989; Nückles et al., 2004). Thus, instructional support is needed to assist or even activate learners’ self-regulatory activities.

Prompts

Prompts are instructional aids designed to activate learners’ self-regulated learning strategies and induce productive learning processes (Bannert, 2009; Engelmann, Bannert, & Melzner, 2021; Hübner et al., 2006; King, 1992; Pressley et al., 1992). As questions or hints, prompts are designed to incite learners to use learning strategies which they are capable of, but do not demonstrate to a satisfactory degree during learning. Following Reigeluth and Stein (1983), prompts can be perceived as strategy activators, since they do not teach new strategies. Rather, they enable known learning strategies that would not spontaneously be used. Therefore, prompts should indicate learners during learning when and which learning strategies to use (Thillmann et al., 2009). In university and school settings, prompts can be included in learning journals, a method to record students’ learning processes both, in form of a questionnaire (standardized learning journals), and in textual form (open-ended learning journals). As providing prompts in learning journals can be useful to support deep-level processing and knowledge construction in university and school settings (Bangert-Drowns et al., 2004; Nückles et al., 2004), we presented prompts to activate learning processes in the present study. These activated and intensified learning processes were shown to increase learning outcomes (see the meta-analysis of the Freiburg Self-Regulated-Journal-Writing Approach, Nückles et al., 2020).

Prompts in learning journals

The positive effects of prompts in learning journals on strategy use on the one hand and learning outcomes on the other hand were replicated and expanded in different learning scenarios and different combinations of cognitive and / or metacognitive prompts (Fung et al., 2019; Glogger et al., 2012; Hübner et al., 2006; Nückles et al., 2009, 2020). Roelle et al. (2017) found that presenting metacognitive prompts first, followed by cognitive ones resulted in increased strategy use and learning outcomes compared to learning journals in which the sequence of the prompts was reversed. In sum, including cognitive and metacognitive prompts in learning journals fosters cognitive and metacognitive strategy use and learning outcomes. Studies on learning journals including prompts focused mainly on cognitive and metacognitive aspects of self-regulation but research investigating the effects of open-ended learning journals including prompts on motivational factors is rare (e.g., Schmidt et al., 2012). Therefore, the present study investigates the effects of learning journals including prompts on cognitive, metacognitive, and the motivational variable self-efficacy.

Why should learning journals including prompts affect learner’s self-efficacy? As indicated in the section “Self-efficacy”, it is assumed that enactive self-regulation can be regarded as a successful learning experience and may reflect mastery, a major source of self-efficacy (Bandura, 1997; Panadero et al., 2017; Usher & Pajares, 2008). By making the self-regulation process more transparent, learning journals should create more experience of enactive self-regulation and consequently more experiences of mastery. As prompts should increase productive learning processes and through this learning outcomes, they contribute to the creation of mastery experiences when included in learning journals. Additionally, conceptualized to induce productive self-regulation processes, prompts do not only affect effective self-regulation via strategy use, but also show learners their repertoire of skills. This might increase learners feeling of being well-equipped to master the learning task. Consequently, prompts support enactive and successful self-regulation processes, one possibility to experience mastery and a major source of self-efficacy. In a hypermedia environment, learners’ self-efficacy increased across learning situation when cognitive and metacognitive prompts were presented (citation blinded). Moreover, recent research also indicates that prompting cognitive and metacognitive learning strategies may increase learners’ self-efficacy even when no effects on strategy use and learning outcomes can be found (citation blinded). As a consequence of the theoretical assumptions and research evidence prompts and self-efficacy, the question arises whether including prompts in learning journals affects learners’ self-efficacy. Therefore, the present study expands current research on the effects of learning journals including prompts by investigating the effects of prompts in learning journals on learners’ self-efficacy.

However, to investigate the effects of prompts in learning journals on learners’ self-efficacy, one should consider that learners’ perceptions of self-efficacy develop over time (see section “Self-efficacy”). Therefore, a longitudinal study is needed in which enactive self-regulation and/or mastery can be experienced multiple times. Structured learning journals were often administered over a longer period in university or school settings to measure the development of learners self-regulated learning activities (Fabriz et al., 2014; Schmitz & Perels, 2011; Schmitz & Wiese, 2006). Yet, many studies on open-ended learning journals including prompts focused on one single journal entry (Berthold et al., 2007; Hübner et al., 2006, 2010) and current research lacks studies in which learning journals including prompts are administered in more than one single learning situation. Therefore, the question is: how does short- and long-term prompting in learning journals affect learners’ self-regulation processes?

Effects of short-term and long-term prompting

When prompts were administered more than once, we differentiate between effects of short-term prompting in learning journals (i.e., prompts were administered in in interventions lasting 1 to 1.5 months), and effects of long-term prompting in learning journals (i.e., prompts were administered in interventions longer than 1.5 months). A longer period of prompting can either be necessary as ongoing assistance for strategy use or it can be disturbing, as once activated strategies might no longer need additional nudges. To get an overview of the existing research, it will be presented in the following.

Nückles et al. (2010) investigated effects of short-term cognitive and metacognitive prompts in weekly open-ended learning journals on university students’ strategy use, interest in the learning contents as one motivational variable, and learning outcomes. For the first six learning journals, writing learning journals including cognitive and metacognitive prompts compared to learning journals without prompts increased students’ cognitive and metacognitive strategy use, interest, and learning outcomes. Analysis revealed that short-term prompting in learning journals intensified learners’ strategy use, increased learners’ interest, and heightened students’ learning outcomes. Also, Schmidt et al. (2012) investigated the effects of prompts in six weekly open-ended learning journals on learners’ strategy use, learning motivation and learning outcomes. When learners received the prompts as part of their learning journal, strategy use, learning motivation, and comprehension of the learning contents increased over time. Hence, the studies support the positive effects of prompts found in studies with one single learning journal and learning session.

Additionally, the studies showed that motivational factors (e.g., interest) can be positively influenced by prompts. Yet, the effects on self-efficacy were not investigated. As prompts can generally affect learners’ motivation (Nückles et al., 2010 (experiment 1); Schmidt et al., 2012), it is possible that prompting in learning journals also affects learners’ self-efficacy. Yet, while Nückles et al. (2010) used cognitive and metacognitive prompts, Schmidt et al. (2012) used motivational prompts in addition to cognitive and metacognitive ones. Moreover, although all learning journals were analyzed individually, the development of learners’ strategy use, and motivation is not reported continuously over time. Viewing self-regulated learning as a process, continuous measurements over time and analyses sensitive to identify the development of self-regulated learning components are crucial. Therefore, continuous assessment and analyses of the components of self-regulated learning are important (Schmitz & Perels, 2011). Thus, a study is needed which investigates the effects of prompting cognitive and metacognitive learning strategies short-term on the development of learners’ strategy use, and self-efficacy. In a comparable university setting, the present study wants to replicate the previously found effects of short-term prompting on learners’ strategy use and learning outcomes. Additionally, it expands the previous literature by reporting the development of learners’ strategy use and the effects of short-term prompting on learners’ self-efficacy.

As learning journals including prompts might be implemented over a longer time, particularly in university classes or online courses, it is relevant to investigate the effects of long-term prompting. In their study, Nückles et al. (2010) indicated that including prompts in learning journals over twelve weeks resulted in decreased strategy use, motivation, and learning outcomes, compared to those students whose learning journals included prompts only for six weeks. This indicates that long-term prompting may hamper learners to autonomously apply their knowledge to new learning situations (Nückles et al., 2010). Nückles et al. (2010) argue that prompts might initially help learners to internalize the prompted learning strategies until they become experts and apply these strategies spontaneously during learning. Experienced learners may not need the support provided by the prompts and may feel distracted by prompts from pursuing their individual learning goal and their planned learning activities (Nückles et al., 2010). This may not only affect learners’ strategy use and learning outcomes, but also self-efficacy. Feeling distracted from following ones’ learning path may not result in experiences of productive self-regulation and mastery. This should affect learners’ self-efficacy negatively. In contrast to the study of Nückles et al. (2010), Fung et al. (2019) found that including metacognitive prompts in weekly learning journals over a period of ten weeks increased learners’ cognitive and metacognitive strategy use and overall self-regulated learning competence. Thus, inconsistent results regarding effects of long-term prompting in learning journals exist.

How can these inconsistent results regarding the effects of long-term prompting be explained? Although both studies investigated the effects of learning journals including prompts on learners’ self-regulated learning in university settings over a longer period, there are some differences. While Nückles et al. (2010) used open-ended learning journals and analyzed the trace data in form of texts in a qualitative way, Fung et al. (2019) used standardized learning journals and analyzed the self-report data. It is possible that the learners did overrate their strategy use in the Fung et al.’s (2019) standardized learning journal, which may result in the different findings. The learning journal in the present study therefore consisted of an open-ended and a standardized part. Moreover, Fung et al. (2019) used only metacognitive prompts which were weekly adapted to the lecture contents. In contrast, Nückles et al. (2010, experiment 1) presented the same cognitive and metacognitive prompts to their learners. It is also possible that the presentation of the prompts caused these different effects. The present study therefore used similar cognitive and metacognitive prompts as Nückles et al. (2010). Using a comparable research design as previous research, the present study replicates and extends previous research by investigating the effects of short- and especially long-term prompting on learners’ strategy use, self-efficacy and learning outcomes.

Research questions and hypotheses

The research question of the present study investigates is whether short-term and long-term prompting in learning journals has effects on learners’ self-regulated learning in terms of strategy use and self-efficacy, as well as the learning outcomes. Recent research showed that including prompts in learning journals short-term increased learners’ strategy use and learning outcomes (e.g., Berthold et al., 2007; Nückles et al., 2010). Effects of prompts on learners’ self-efficacy, a motivational variable central to many self-regulation models, were not investigated yet. To replicate and expand the literature basis, we investigated the effects of prompts on learners’ strategy use, self-efficacy, and learning outcomes when prompted short-term only (Research questions Q1 to Q3) and when prompted long-term in comparison to short term (Q4 to Q6).

Regarding the effects of short-term prompting, we first asked if including prompts in learning journals short-term will increase learners’ cognitive and metacognitive strategy use (Q1). We hypothesized that learning journals including prompts short-term will increase learners’ cognitive and metacognitive strategy use (H1). Second, we asked if including prompts in learning journals short-term will increase learners’ self-efficacy (Q2). We assumed that including prompts in learning journals short-term will increase learners’ self-efficacy (H2). Third, we questioned whether learners’ strategy use and self-efficacy predict learning outcomes (Q3). Based on the effects of strategy use and self-efficacy on learning outcomes outlined above we expected learners’ strategy use and self-efficacy to influence the learning outcomes. We thus hypothesized, that learners’ cognitive and metacognitive strategy use as well as their self-efficacy predict subsequent learning outcomes positively (H3).

Regarding the comparative effects of short-term versus long-term prompting (Q4 to Q6) we face inconsistent results of previous studies for long-term prompting on learners’ strategy use and learning outcomes (e.g., Fung et al., 2019; Nückles et al., 2010). Therefore, the study also investigates the effects of prompting cognitive and metacognitive self-regulation strategies in learning journals long-term on learners’ strategy use, self-efficacy and learning outcome. As studies showed positive and negative effects of long-term prompting (e.g., Fung et al., 2019; Nückles et al., 2010), we refrained from formulating directed hypotheses. We asked whether including prompts in learning journals short-term affects the development learners’ cognitive and metacognitive strategy use differently compared to learners who received prompts long-term (Q4). Further, we questioned whether including prompts in learning journals short-term affects the development of learners’ self-efficacy differently compared to learners who received prompts long-term (Q5). Finally, we asked whether learning outcomes of learners whose learning journals included prompts short-term differ from those of learners whose learning journal included prompts long-term (Q6).

Following the conceptualization of self-regulated learning as a process, which unfolds over time, we will use self-reports and qualitative trace data of the learning journals to analyse the development of the variables over time. Doing so, we will also expand previous research which measured learners self-regulated learning continuously over time but only analysed and reported the data accumulated over multiple measure points (cf. Nückles et al., 2010, Schmidt et al., 2012).

Methods

Study design

To make the study comparable to previous research by Nückles et al. (2010), the experiment was incorporated into the university course “Introduction to educational science” at a German university. The university course was part of the curriculum to become a professional teacher. It represents the first university course for all teacher students focussing on central concepts of learning and teaching as well as learning and teaching methods relevant for their professional teacher life. Due to this high relevance for all teacher students, the course was selected. Weekly learning journals accompanied the lectures as compulsory follow-up course work. Besides supporting the students, this was implemented to provide all students with a self-experience of an instructional means designed to recapitulate and reflect upon the learning contents.

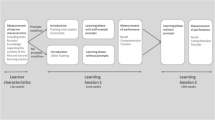

The university course consisted of thirteen lectures. The lectures were divided into three units. The study took place during the first two units of the course (see Fig. 1). The units represented logical topics: the first unit dealt with “Basic concepts of Education: Learning, Teaching, Development” (blue part in Fig. 1) and the second unit focussed on “Philosophical Aspects of Learning and Teaching” (green part in Fig. 1). The respective first lectures of each unit included a 45-minute introductory lecture, to which the learning journal served as a baseline (yellow parts of Fig. 1) to assess learners’ strategy use while journal writing and their self-efficacy. The introductory lecture was followed by three 90-minute lectures in the subsequent weeks. The units ended with an exam after these four lectures. Lectures were videotaped and uploaded to the university’s online learning platform.

The mixed study design was incorporated in the university course and contained both between- and within-subjects factors. The between-subjects factor represents the instructional manipulation: students who received learning journals including prompts short-term, i.e. four times (short-term group in Fig. 1) and students who received learning journals including prompts over the complete study time, i.e. seven times during both units. (long-term group in Fig. 1). The within-subjects factor, time, represents the weekly assessments (t1, t2, …, t8). Dependent variables were learners’ cognitive and metacognitive strategy use and their self-efficacy. These variables were continuously measured in the weekly learning journals. Further, the learning outcome was measured at the end of every unit in form of an exam.

Participants

All students enrolled int the course “Introduction to educational science” were informed about the experiment and invited to participate at the beginning of the semester. 85 students volunteered to participate in this study and gave their written informed consent (92% of the students enrolled in the course). This means that students agreed that we could assess, read, and analyse the individual learning journals as part of a scientific study and request learners’ exam grades from the lecturer. After data collection, eleven students were excluded from the final sample since they dropped out of the course or completed less than half of the learning journals. The final sample comprised N = 74 students (45.9% in the short-term group). Students were M = 20.62 years (SD = 2.56) and 50% of the participants were female. All students were enrolled in a university program to become STEM teachers at German secondary schools. Most students were in their first semester (80%), 13% in their second or third semester, and 7% were in their fourth to seventh semester. Students’ self-reported average school leaving examination grade was M = 2.19 (SD = 0.57, 1 = excellent, 5 = fail). Participants were randomly assigned to the short-term and long-term prompting group.

Learning journal

The learning journal was implemented in the university’s online learning platform. Learning journals consisted of an open-ended and a standardized part, which were to be processed in the presented sequence. The learning journals were compulsory for the course in a way that having completed and submitted at least 75% of the learning journals was a necessary requirement to be admitted for the exams, i.e., 3 out of 4 learning journals per unit had to be completed.

Open-ended part of the learning journal

The open-ended part consisted of a general instruction on the use of a learning journal. The instruction was the following: “Greetings from this week’s “Introduction to educational science” lecture! Some time has passed since the lecture ended. Take half an hour to write a learning journal about the material covered in the lecture “Introduction to educational science”. You ask yourself why to write a learning journal? The aim of a learning journal is to achieve a deeper understanding of the learning content. Please take full advantage of the available time of 30 minutes.”, see Appendix A for a picture of the instruction implemented it the online learning platform. Below the instruction, there was a textbox in which learners could write for thirty minutes. After 30 min, the text was automatically saved, and no further editing of the text was possible. The time was restricted to 30 min to help learners focus on the central aspects of the lecture. Moreover, keeping the time constant helped to make the learning journals more comparable throughout the experiment and more comparable to other studies which used the same time for journal writing (e.g., Berthold et al., 2007).

When the learning journal contained prompts (see study design in Fig. 1), in addition to the general instruction, there was a paragraph introducing the prompts (“When writing the learning protocol, be guided by the following key questions. These should help you to get an overview of the content of the last lecture and to link the new learning content to your already existing knowledge. They also help you to reflect and control your learning behavior.”). Subsequently, three metacognitive and three cognitive prompts were presented (Roelle et al., 2017). Prompts were always presented in the same order to prevent possible confounding due to stage setting effects of the prompts presented (cf., Roelle et al., 2017), and make the study more comparable to the previous literature (e.g., Nückles et al., 2010; Schmid et al., 2012). A screenshot of the open-ended part of the learning journal including prompts can be seen in Appendix A.

Cognitive prompts The cognitive prompts were designed to activate organization strategies (“How can you best organize the structure of the learning content? You can for instance use headings, lists, sketches, diagrams or a mind map.”, “How can you reproduce the central points and their context in your own words so that a fellow student who missed the last lecture could understand this content well?”) as well as elaboration strategies (“Which examples can you think of that illustrate, confirm, or conflict with the learning contents?”). The cognitive prompts were selected based on previous articles by Berthold et al. (2007) and Roelle et al. (2017).

Metacognitive prompts Two monitoring prompts intended to activate monitoring strategies (“Which main points have I already understood well?”, “Which main points haven’t I understood yet?”), and one planning-of-remedial-strategies prompt were presented. The latter was selected to encourage students to think of possibilities to regulate the learning process by using remedial cognitive strategies (“What possibilities do I now have to overcome my comprehension problem?”). The metacognitive prompts were used previously in studies investigating the effects of learning journals including prompts on learners’ strategy use and learning outcomes (Berthold et al., 2007; Nückles et al., 2010).

Standardized part of the learning journal

The standardized part of the learning journal consisted of two questionnaires: one to assess learners’ strategy use and one to measure students’ self-efficacy.

Learning strategies questionnaire For economic reasons (time filling up the questionnaire) a short learning strategies questionnaire was used to assess students’ strategy use. The questionnaire was developed on the theoretical concepts of the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire (MSLQ; Pintrich et al., 1993). The questionnaire contained three items assessing cognitive strategies (organization, elaboration, rehearsal) e.g., “While learning for the next educational psychology exam, I thought of specific examples regarding certain learning contents“, and three items on metacognitive strategies (planning, monitoring, regulation), e.g., “While learning for the next educational psychology exam, I monitored my learning progress” (see Appendix A). Items were selected from established questionnaires and/or learning journal studies and were slightly adjusted to make sure they were specific to the learning situation (citation blinded; Boerner et al., 2005; Perels et al., 2007; Wild & Schiefele, 1994). The items were answered on a 5-point Likert-type scale (0 = not at all true of me, 4 = very true of me). Reliabilities of the scale were calculated for each measure point and a meta-analysis of the coefficient alpha over all eight time points was done based on formulas presented by Rodriguez and Maeda (2006). This resulted in acceptable to good reliabilities for the cognitive (α = .62) and metacognitive (α = .82) learning strategies subscale.

Self-efficacy questionnaire To measure students’ self-efficacy regarding the successful completion of the university course, the self-efficacy scale of the MSLQ was used (Pintrich et al., 1993). The scale consists of eight items (e.g., “I’m confident I can learn the basic concepts taught in this course.”) which are answered on a seven-point Likert-type scale (1 = not at all true of me, 7 = very true of me). A meta-analysis of the coefficient alpha over all eight measure points was calculated and showed good reliabilities (α = 0.91) which are comparable to previous studies (Pintrich et al., 1993).

Learning outcomes

Learning outcomes were measured via exams after each lecture unit and contributed equally to the course grade. The exams lasted 30 min and included 9 questions for the first unit and 10 questions for the second unit, each with multiple choice and open-ended questions. An example of a question of the first unit is to relate examples from school to the concepts of negative and positive reinforcement or punishment. An example of a question of the second exam is to describe what Kant means with “dignity of humans” and to illustrate this description with an example from school. For each exam learners could reach 30 points, with 1 to 4 points for each task reflecting their weighed difficulty. Points were transformed into grades with 30 points for grade 1,0 (excellent), 15 points for the lowest grade 4,0 (sufficient) and less than 15 points for grade 5 (fail). The grades have been differentiated into 1.0, 1.3, 1.7, 2.0, 2.3 and so forth until 4,0. Students’ exams were evaluated by the lecturer, who was blind to students’ experimental condition and who transferred the respective grades for those students who gave their consent to do so. Average grades and standard deviations of the first and the second exam are Mexam_1 = 2.40, SDexam_1 = 0.97, Mexam_2 = 2.54, SDexam_2 = 0.83. To make the interpretation easy, exam grades were later multiplied by − 1 to recode it. For future analyses, higher exam grades reflect higher learning outcomes, whereas lower exam grades reflect lower learning outcomes.

Coding of the qualitative data from the learning journal

To analyse the qualitative data from the open-ended part of the learning journal, the written answers of each journal were coded, as recommended by Mayring (2015) and Kuckartz (2016). The coding scheme was developed, both inductive and deductive, in order to assess the learning strategies reported by the students (see Appendix C). The final coding scheme contained three main categories: cognitive, metacognitive and resource management strategies.

Before coding the individual learning journals, they were segmented into single statements which represented the coding units. Therefore, all texts written in the learning journals were divided into smaller units based on grammatical and/or organizational markers like “and”, “or”, “because”, “for instance”, or “for example”. Every segment was classified as one of the categories listed in the coding scheme. The learning journals were coded by two raters. After 10% of the material both raters discussed possible disagreements and adjusted the coding scheme. The interrater reliability was identified via Cohens Kappa (κ = 0.85).

After coding the individual learning journals, the coded segments per category were counted. This resulted in the quantity (amount) of coded segments per category for every learning journal and student. On average, we identified Msegments = 28.92 (SDsegments = 15.13) segments per learning journal. Further, Mcognitive = 87.54% of the segments (SDcognitive = 23.63) were categorized as cognitive strategy use and Mmetacognitive = 11.62% of the segments (SDmetacognitive = 22.48) were categorized as metacognitive strategy use. The remaining segments (< 1%) included statements concerned students’ management of internal and external resources (e.g. additional learning material) were thus categorized as resource management strategies (< 1%).

Rationale of analysis

Our research questions and hypotheses focussed on different aspects of the study. While the first three research questions (Q1-Q3) refer to effects of prompting short term on the three dependent variables strategy use, self-efficacy and learning outcomes, the latter three (Q4-Q6) refer to the comparison of short-term and long-term prompting on the same three dependent variables.

In research questions 1 and 2 (H1 and H2, respectively) we addressed the development of learners’ strategy use and self-efficacy over time during unit one., i.e. during the short term prompting phase. As all learners received the same treatment (learning journal including prompts during t2 – t4), we did not differentiate between the groups. Given the sample size and the number of measure points, we calculated one-way repeated measures ANOVAs to investigate whether learners’ strategy use developed over time (from the baseline measure t1 to the last measure in the first unit t4). The analyses were repeated for cognitive and metacognitive strategy use, each based on self-report data and on qualitative data. The development of learners’ self-efficacy was also analysed by a one-way repeated measures ANOVA. For learning outcomes (H3), we only had one point of measurement after the first unit (exam 1). As both groups received the same treatment, we did not analyse whether the two groups differ but in which way strategy use and self-efficacy affect learning outcomes for all learners in this phase. Thus, for H3 we analysed the relationship between strategy use, self-efficacy, and learning outcomes by calculating a regression analysis.

To investigate our research questions Q4 and Q5 on the differences in the development of learners’ strategy use and self-efficacy between the short-term and long-term group, we calculated mixed ANOVAS. The between-subjects factor was learners’ experimental group while the within-subjects factor was the time with 4 points of measurement during the second unit (t5 to t8). For strategy use, the analyses have been again repeated for cognitive and metacognitive strategy use, each based on self-report data and on qualitative data. Finally, for investigating the effects of short-term and long-term prompting on learning outcomes (Q6) we again had only one point of measurement at the end of unit 2 (exam 2). For the results of this exam, we calculated a t-test to see if learning outcomes differ between the learners who received prompts short-term and learners who received prompts long-term.

Results

First, we investigated whether a-priori differences between the groups with short-term and long-term prompting existed. No differences were found between groups regarding demographic data such as age, t(72) = -0.39, p = .70, school leaving examination grade, t(72) = -0.84, p = .40, and semester, t(45) = 1.32, p = .19. Further, t-tests were calculated from learners’ self-report and qualitative data at the baseline time-point (t1). Results indicated no differences between both groups regarding self-reported cognitive strategy use, t(72) = -1.67, p = .10, self-reported metacognitive strategy use, t(72) = 0.14, p = .89, the quantity of cognitive strategy use, t(65) = -0.60, p = .55, the quantity of metacognitive strategy use, t(65) = -0.16, p = .88, and self-efficacy, t(72) = 0.33, p = .75. Descriptive statistics of all measure points can be seen in Tables 1 and 2.

Short-term effects of prompts

On the development of strategy use

The first hypothesis addressed the short-term development of learners’ cognitive and metacognitive strategy use (blue marking in Fig. 1). We calculated a one-way repeated measures ANOVA using learners’ cognitive strategy use reported in the standardized part of the learning journals t1 – t4 as the dependent variableFootnote 1. Mauchly’s test indicated that the assumption of sphericity had been violated for the main effect of time W = 0.783, p = .004, ε = 0.85. Therefore, degrees of freedom were corrected using Greenhouse-Geisser estimates of sphericity. There was a main effect of time, F(2.55,186.42) = 15.95, p < .001, ηp² = 0.18. This indicates a significant increase in cognitive strategy use over time (see Fig. 2).

Second, the development of learners’ metacognitive strategy use was investigated with a one-way repeated measures ANOVA. Learners’ metacognitive strategy use reported in the standardized part of the learning journals t1 – t4 was used as the dependent variable. As the assumption of sphericity had been violated for the main effect of time, W = 0.706, p < .001, ε = 0.83, degrees of freedom were corrected using Greenhouse-Geisser estimates of sphericity. There was again a main effect of time, F(2.49,181.95) = 31.35, p < .001, ηp² = 0.30. The results indicate an increase in metacognitive strategy use over time; see Fig. 3.

In addition to the self-reports, we analysed the development of the quantity of cognitive strategy use in the open-ended part of the learning journals. A repeated measures ANOVA was calculated with the quantity of cognitive strategy use in the open-ended learning journals at t1 – t4 as dependent variable. The assumption of sphericity was violated for the main effect of time, W = 0.66, p < .001, ε = 0.78. Thus, degrees of freedom were corrected using the Greenhouse-Geisser estimates of sphericity. Analysis revealed a main effect of time, F(2.35,133.97) = 14.78, p < .001, ηp² = 0.21. The results indicate a significant increase in the number of segments coded as cognitive strategy use over time, see Fig. 4.

Finally, we analysed the quantity of metacognitive strategy use coded in the open-ended part of the learning journal. Again, a repeated measures ANOVA was calculated. The dependent variable was the number of segments coded as metacognitive strategy use in learning journals at t1 – t4. The analysis indicated no main effect of time, F(3,171) = 0.75, p = .52, ηp² = 0.01. The results suggest that the quantity of metacognitive strategy use did not change over time, see Fig. 5.

On the development of learners’ self-efficacy

The second hypothesis addressed the development of learners’ self-efficacy after short-term prompting in learning journals. A one-way repeated measures ANOVA was calculated using learners’ self-reported self-efficacy in the learning journals of unit 1, t1 – t4, as the dependent variable. The assumption of sphericity was violated for the main effect of time W = 0.85, p = .04, ε = 0.91. Therefore, degrees of freedom were corrected using the Greenhouse-Geisser estimates. Analysis indicated no main effect of time, F(2.72,198.68) = 2.27, p = .09, ηp² = 0.03. The results indicate no change in learners’ self-reported self-efficacy during unit 1, see Fig. 6.

Effects of strategy use and self-efficacy on learning outcomes

The third hypotheses dealt with the effects of learners’ self-reported strategy use and self-efficacy on the learning outcomes. To investigate the hypothesis, a multiple regression was calculated. Therefore, learners’ cognitive and metacognitive strategy-use, and their self-efficacy reported in the closed part of the learning journal before the first exam (t4) were entered as predictors. The analysis revealed that neither students’ self-reported cognitive nor their metacognitive strategy use predicted learning outcomes. Learners’ self-efficacy predicted students’ grade in the first exam indicating that higher self-efficacy resulted in better learning outcomes, see Table 3.

Effects of long-term prompting

On the development of learners’ strategy use

To answer research question four, we investigated whether long-term prompting would affect learners’ strategy use differently compared to learners, who received prompts only short-term. A t-test was calculated to identify whether groups differed regarding the use of cognitive learning strategies reported in the journal t5 (second baseline, see Fig. 1). No differences between groups regarding cognitive strategy use were found, t(72) = -1.39, p = .17. Next, we calculated a mixed ANOVA with the condition (short-term group vs. long-term group) as the between groups factor and learners’ self-reported cognitive strategy use at the time points t5 – t8 as the within-subjects factor. Mauchly’s test of sphericity indicates that the sphericity assumption had been met for the main effect of time, W = 0.870, p = .08. The analysis indicated a main effect of time, F(3,216) = 11.05, p < .001, ηp² = 0.13, but no main effect of condition, F(1,72) = 2.34, p = .13. No interaction of time × condition was found, F(3, 216) = 0.23, p = .87. Learners’ self-reported cognitive strategy use decreased during unit two irrespective of the condition, see Fig. 7.

As groups did not differ regarding their self-reported metacognitive strategy use at t5 (second baseline, see Fig. 1), t(72) = -0.69, p = .49, we investigated the development of metacognitive strategy use in the long-term group and in the short-term group during unit 2. Calculating a mixed ANOVA, the condition was used as a between-subjects factor and self-reported metacognitive strategy use in the learning journals t5 – t8 was the within-subjects factor. As that the assumption of sphericity had been violated for the main effect of time, W = 0.811, p = .01, ε = 0.88, degrees of freedom were corrected using Greenhouse-Geisser estimates of sphericity. There was a main effect of time, F(2.65,190.69) = 7.82, p < .001, ηp² = 0.10, but no main effect of condition, F < 1, and no time × condition interaction, F < 1. Learners’ self-reported metacognitive strategy use decreased over time irrespective of the condition in unit two, see Fig. 8.

In addition to the self-reports, we analysed the qualitative data to investigate whether differences in the development of learners’ quantity of cognitive strategy use between the groups who were prompted short-term and long-term existed. Groups did not differ regarding the quantity of cognitive strategy use at the baseline measure t5, t(70) = -0.05, p = .96. Therefore, a mixed ANOVA was calculated. Learners experimental condition (short-term vs. long-term prompting) was used as a between-subjects factor, the quantity of cognitive strategy use in the learning journals t5 – t8 was the within-subjects factor. As the assumption of sphericity had been violated for the main effect of time, W = 0.62, p < .001, ε = 0.82, degrees of freedom were corrected using Greenhouse-Geisser estimates of sphericity. There was neither a main effect of time, F(2.47,148.15) = 1.84, p = .15, ηp² = 0.03, nor main effect of condition, F < 1, nor a time × condition interaction, F(2.47,148.15) = 1.02, p = .38, ηp² = 0.02. In sum, analyses revealed no changes over time, no differences between groups, and no different temporal development regarding the quantity of cognitive strategy use between the groups, see Fig. 9.

Further, we investigated whether differences in the development of learners’ metacognitive strategy use between the two groups existed. No differences regarding the quantity of metacognitive strategy use in learning journal t5 were found, t(70) = -0.59, p = .56. A mixed ANOVA was calculated with learners’ experimental condition as the between-subjects factor. The within-subjects factor was the quantity of metacognitive strategy use in the learning journals t5 – t8. The assumption of sphericity had been violated for the main effect of time, W = 0.60, p < .001, ε = 0.76. Therefore, degrees of freedom were corrected using Greenhouse-Geisser estimates of sphericity. There was a main effect of time, F(2.27,135.90) = 4.42, p = .01, ηp² = 0.07, but no main effect of condition, F < 1, and no time × condition interaction, F < 1. The number of metacognitive learning strategy segments in learners’ open-ended part of the learning journal changed over time irrespective whether learners received prompts short-term or long-term, see Fig. 10.

On the development of learners’ self-efficacy

The next research question (Q5) addressed whether differences regarding self-efficacy occur when learners’ experience short-term prompting or long-term prompting. We calculated a mixed ANOVA using the experimental condition as the between-subjects factor and learners’ self-reported self-efficacy in learning journals t5 – t8 as the within-subjects variable. No differences regarding learners’ self-efficacy existed at t5, t(72) = -1.22, p = .23. As the assumption of sphericity had been violated for the main effect of time, W = 0.733, p = .001, ε = 0.87, degrees of freedom were corrected using Greenhouse-Geisser estimates of sphericity. There was a main effect of time, F(2.61,187.57) = 11.52, p < .001, ηp² = 0.14, but no main effect of condition, F(1,72) = 2.84, p = .10, ηp² = 0.04, and no time × condition interaction, F(2.60,187.57) = 1.47, p = .23, ηp² = 0.02. Learners’ self-efficacy decreased over time irrespective of the condition, see Fig. 11.

On learning outcomes

The last research question (Q6) concerned differences between short- and long-term prompting in learning journals on students’ learning outcomes, i.e. learners’ grade in the second exam. The short-term group had an average grade of M = 2.50 (SD = 0.69) while the long-term group had an average grade of M = 2.41 (SD = 0.80) in the second exam. An independent t-test indicated that no differences between the groups regarding the exam grades existed, t(72) = 0.53, p = .60.

Discussion

The present study investigated effects of prompting cognitive and metacognitive self-regulation strategies short- and long-term in learning journals on learners’ cognitive and metacognitive strategy use, self-efficacy, and learning outcomes. Therefore, we implemented learning journals as follow-up course work in a university course and those learning journals included prompts either in the first half or all the time. Effects were analysed using self-reports and qualitative data.

With respect to Zimmerman’s (2005) model of self-regulated learning the study illustrates that cognitive, metacognitive, and motivational components of self-regulated learning develop over time and that these components can partly be influenced by cognitive and metacognitive prompts. Moreover, results highlight the role of the motivational self-regulated learning component self-efficacy for learning outcomes. Thus, the study supports the processual view of self-regulated including cognitive, metacognitive and emotion-motivational components.

Short-term effects of prompts

The first three hypotheses addressed the short-term effects of prompts in learning journals. The results of the self-reports and qualitative data analyses confirm the first hypothesis that including prompts in learning journals short-term increased learners’ cognitive strategy use. The findings are in line with previous research, where prompts included in learning journals fostered cognitive strategy use (Berthold et al., 2007; Hübner et al., 2006; Nückles et al., 2010). As suggested by Reigeluth and Stein (1983), prompts may have exerted the function of activating cognitive learning strategies. However, while self-reports indicated that metacognitive strategy use increased, the analysis of the qualitative data did not show any changes in the quantity of metacognitive strategy use. The difference between self-report and qualitative data may be due to their different foci. While qualitative data represent the quantity of strategy use during journal writing, self-reports focussed on learning for the exams in general. It is possible that learners’ metacognitive strategy use during learning for the first exam increased but strategies were reported less while writing the learning journals. Similarly, most participants were freshmen, starting to adjust to the new learning situation at university with increased autonomy and need for metacognition (Dignath-van Ewijk et al., 2015). Therefore, the results could possibly indicate student deficits. The question whether learners’ strategy use increased when prompts were part of the learning journal is supported by three of the four measures.

Next, the results did not confirm the second hypotheses regarding the effects of including prompts short-term in learning journals on self-efficacy. As self-efficacy is affected by mastery experiences (Bandura, 1997), the self-regulated learning processes activated by the prompts may not have been enough to create mastery experiences necessary to increase learners’ self-efficacy. Van Dinther et al. (2011) suggest that for experiences to affect self-efficacy, the length of the intervention and its authenticity are important. Since the intervention supported students’ self-regulated learning of a compulsory university course in study program, the length and authenticity of the intervention should be given. It is possible that learners needed feedback on their learning journals to experience mastery. Since learners had no reference whether they performed well in writing their learning journal, the necessary feedback to evaluate their performance and learning process was missing (Bandura, 1997). To test this hypothesis, learning journals with/without prompts and with/without feedback on their performance in the learning journal should be integrated in a university course.

The third hypothesis dealt with the effects of strategy use and self-efficacy on learning outcomes. We assumed that strategy use and self-efficacy predicted learning outcomes positively. The missing effects of strategy use on learning outcomes contrast previous findings which highlight the relevance of cognitive and metacognitive strategies for learning outcomes (Dent & Koenka, 2016; Glogger et al., 2012). Yet, a recent study which investigated effects of prompts in a flipped classroom setting, found changes in the learning behaviour but not in the learning outcomes (van Alten et al., 2020). With respect to Bloom’s taxonomy (1956), a possible reason is that learners focussed on other levels than required by the exam questions. Since the exam contained numerous transfer questions, it is possible that learners focussed on levels such as recall or comprehension and used learning strategies to achieve these levels. Further research should therefore examine how learning journals and prompts affect the different levels of learning with respect to Bloom’s taxonomy (1056). Moreover, although the extent to which learning strategies are used often predicts learning outcomes (Dent & Koenka, 2016; Vrugt & Oort, 2008) it is also possible that learners may have applied more of the prompted strategies but in a low quality and thus, learning outcomes were not affected. Glogger et al. (2012) found that prompting learners while journal writing increased the quantity of learning strategies, but not their quality. Monitoring and regulation processes are needed to ensure that learning strategies are successfully applied (Leutner et al., 2007). Thus, it is possible that strategy use was increased (quantity) but the quality of the learning strategies, affecting learning outcomes, may not have been affected by the prompts and examine more deeply how the quality and the quantity of learners’ strategy use affects learning outcomes.

Regarding the second part of the hypothesis: Self-efficacy predicted learning outcomes significantly. The results are in line with previous studies indicating positive effects of self-efficacy on learning outcomes (Diseth, 2011). Since self-efficacy was not affected by the prompts, the effects of self-efficacy on performance cannot be attributed to the effects of prompts. Thus, they reflect the general importance of self-efficacy for learning outcomes in university settings (Robbins et al., 2004). Given the importance of self-efficacy, interventions to foster self-efficacy in academic settings should be implemented early at university (Bandura, 1997).

Effects of long-term prompting

Three research questions addressed the effects of prompting short-term compared to long-term in learning journals on learners’ cognitive and metacognitive strategy use, self-efficacy, and learning outcomes.

First, we focussed on the effects of short-term prompting compared to long-term prompting in learning journals on students’ strategy use (Q4). Contrasting previous studies which indicated positive and negative effects of long-term prompting (Fung et al., 2019; Nückles et al., 2010), self-reports indicated that learners’ cognitive and metacognitive strategy use decreased in both groups. Our qualitative data suggested that cognitive strategy use was stable while metacognitive strategy use first increased and then decreased back to the starting level, irrespective of the group. In sum, data indicate (a) that long-term prompting had no effect on strategy use, and (b) that learners’ who were prompted short-term partly internalized their self-regulated learning strategies and applied them continuously. How can these effects be explained?

To explain why a) long-term prompting had no effect on strategy use, it is possible that learners disregarded the instruction of the learning journals after some time. As suggested in other prompting studies, the effect of prompts might depend on learners’ compliance with the prompts (Bannert et al., 2015). Since in the long-term group, the instructions including the prompts were the same over several weeks, the missing effect on strategy use can be regarded as a reduced compliance with the instruction. Consequently, the development of learners’ strategy use when prompts were given long-term did not differ from the strategy use of learners who received prompts short-term. Another possibility is that students of both groups talked to each other about their learning journals. It is possible that some students of the short-term group told the students in the long-term group that their learning journals did not include the prompts anymore. Thus, the prompts may have been regarded as irrelevant for the learning journal. It is also possible that the group who still received prompts informed the other group that it is still worth using them so they might have revisited their previous learning journals including prompts. With respect to other studies on the effects of long-term prompting (e.g., Fung et al., 2019; Nückles et al., 2010), it is also possible that the length of the intervention in combination with learners’ aptitudes is crucial to whether prompting affects learning positively, negatively, or not at all. Taken together, the present research and the research by Nückles et al. (2010) and Fung et al. (2019) indicate that prompts do not immediately change from fostering strategy use to harming it. Whether or not prompting continues to be helpful might be considered for instance with respect to learners’ compliance with the prompts, their aptitudes, and their deficiencies (see subsequent paragraph). Thus, future research should investigate the effects of short-term and long-term prompting with respect to learners’ characteristics.

Next, we need to discuss why b) learners’ who were prompted short-term did only partly internalize their self-regulated learning strategies. Contrasting Nückles and colleagues’ (2010) assumption, short-term prompting in learning journals did only partly lead to the internalization and automated application of learning strategies. The qualitative data indicate that prompts helped learners to activate cognitive strategy use during journal writing and keep them continuously on a higher level. Their general increased cognitive strategy use (self-reports) could not be maintained. Maintaining metacognitive activities seems to be more demanding (cf. Nückles et al., 2010, experiment 2). Since learners were mainly freshmen and used to more structured learning at school, the results might indicate that students may not necessarily have a production deficit but rather a utilization deficiency (cf. Hübner et al., 2010; Miller, 2000). Providing more direct instruction of self-regulated learning including conditional knowledge about when and why to apply certain strategies in form of training or mentoring programs might help learners to internalize and automate strategy use and self-regulated learning skills (Fabriz et al., 2014; Pressley et al., 1990). In school settings, trainings were successfully used to teach self-regulated learning strategies (Dignath & Büttner, 2008). Given the increased autonomy and need for metacognition at university, training learners explicitly might be useful when starting at university (Dignath-van Ewijk et al., 2015).

The next research question addressed effects of short-term versus long-term prompting on learners’ self-efficacy (Q5). Analyses indicated that, irrespective whether learners were prompted short-term or long-term, self-efficacy decreased during unit two. It is possible that learners perceived little success in the first exam, which might have influenced learners’ self-efficacy. As stated in their meta-analysis, past performance strongly influences self-efficacy (Sitzmann & Yeo, 2013). Maybe this first learning outcome feedback had a stronger impact on learners’ subsequent self-efficacy than the self-regulated learning processes triggered by the prompts. Unfortunately, in this field study we could not suspend this possible interference of achievement feedback. In sum, these findings support our missing effects of short-term prompting on strategy use. Moreover, providing feedback to learners regarding the quality of their learning journal might have helped to create other sources of feedback for learners to influence their self-efficacy.

The last research question was concerned with the effects of short-term and long-term prompting on learning outcomes (Q6). Analyses indicated no differences between both groups regarding learning outcomes. The results contrast previous findings which indicate negative effects of long-term prompting compared to short-term (fading) prompts on learning outcomes (e.g., Nückles et al., 2010). Since in the present study, prompts had no effects on learners’ strategy use and motivation, long-term prompting failed to activate productive self-regulation processes. As a result, learning outcomes did not differ between groups.

Overall, this study brought light into the diverse empirical results regarding long-term prompting in learning journals. Thereby the study does not support the previous findings suggesting negative effects of prolonged prompting (e.g., Nückles et al., 2010). Analysis of the qualitative data indicated that prompts helped learners initially to increase cognitive strategy use to a certain degree on which learners’ cognitive strategy use kept stable. With respect to learners’ metacognitive strategy use, results indicate that learners might profit from more direct instruction. Self-efficacy was not affected by the prompts but represented a powerful motivational variable associated with learning outcomes.

Strengths, limitations, and implications

Investigating the effects of short- and long-term prompting in learning journals on learners’ strategy use, self-efficacy, and learning outcomes, the study took a closer look at the development of these variables over time. Thus, the contributions of the present study are in different ways: (a) the study investigated effects of prompts in learning journals on cognitive, metacognitive, and motivational aspects in a university setting, (b) the study broadened the literature basis on the effects of long-term prompting in learning journals, and (c) the present study combined self-reports and qualitative data. Based on these three major aspects, strength, limitations and implications for future research and practise will be discussed.

One strength of the present study is that the study investigates well-known positive effects of prompts in a real university setting and daily life of mostly freshman students. Thus, the study supports findings from previous laboratory experimental research on the effects of prompts in the field. This comes at the cost of a limited flexibility regarding the design and variables investigated. Given the large number of research supporting the positive effects of prompts in learning journals (e.g., Berthold et al., 2007) and research questions focussing on the effects of short- and long-term prompting, we refrained from having a “control group” without prompts. From an ethical perspective in this setting where exam results mattered, we could not advantage one group of learners over another, given that we hypothesized that the intervention affected learning outcomes.

Another strength of the study is that we focussed not only on cognitive and metacognitive effects of prompts but also on the motivational variable self-efficacy as first steps towards a deeper understanding of motivational factors in self-regulated learning interventions. The present study supports the importance of self-efficacy as a significant predictor of learning outcomes (cf. e.g. Sitzman & Yeo, 2013). Thus, it seems crucial to investigate strategies that increase learners’ self-efficacy beliefs. Further, since it is assumed that self-efficacy and metacognition are closely linked (Efklides, 2011), investigating interaction effects of metacognition and self-efficacy in more detail seems important not only for practical implications, but also for theory development (Efklides, 2011; van Dinther et al., 2011; Zimmerman, 2005). Additionally, for ecological reasons, we focussed on one motivational variable only. Besides the expectancy component, value is also a highly relevant motivational facet (cf. expectancy-value perspective, Wigfield & Cambria, 2010). Investigating the effects of prompts on cognitive, metacognitive, and motivational variables in more detail will help to develop a more thorough understanding of the processes triggered by prompts.

The third strength is that, contrasting previous studies (e.g. Berthold et al., 2007; Nückles et al., 2009), the present study investigated not only effects of short-term prompting but also of long-term prompting in learning journals. While other studies found positive or negative effects of long-term prompting (e.g., Fung et al., 2019; Nückles et al., 2010), results of the present study indicate neither positive nor negative effects of long-term prompting compared to short-term prompting on strategy-use, self-efficacy, and learning outcomes. Future research should add to our research and analyse the effects of long-term prompting more systematically. Long-term interventions may last for a whole university term (Nückles et al., 2010), ten weeks (Fung et al., 2019), or seven weeks (present study). Further, adapting prompts individually to learners or letting learners design prompts by themselves may be fruitful methods to promote sustainable strategy use and high compliance (Pieger & Bannert, 2018; Schwonke et al., 2006). Additionally, motivational prompts could be beneficial, as we found decreasing self-efficacy after the first learning outcome feedback. As previous research indicates, motivational prompts can be used in university settings to increase learners’ strategy use, motivation, and learning outcomes (Daumiller & Dresel, 2018; Schmidt et al., 2012).

Another strength of the present study is that we used qualitative data and self-report data. Given that self-reports do not always mirror learners’ actual learning behaviour (e.g., Winne & Jamieson-Noel, 2002), the present study used also qualitative trace data by analysing the quantity of strategy use in the open-ended parts of the learning journalsFootnote 2. Comparable to students notes, these data can be regarded as trace data (cf. Hadwin et al., 2007). This is especially important since the reliability of the questionnaire on cognitive learning strategies was only acceptable (α = 0.62 across all measure points). Although the two measures of learners’ strategy use (questionnaire data and qualitative data) had different foci, the measures for learners’ cognitive strategy use were correlated (see Appendix D). This indicates that learners were able to adequately report their cognitive strategy use. Still, future research could add up to our approach by using for example experience sampling methods (citation blinded). In addition, trace data on learners’ navigation in the university’s online learning platform might help to get more insight into students’ learning activities by relying on so-called objective data. Moreover, although qualitative data helped to gain more insight into how students learned, the analysis did not cover the quality of the strategy use. Analysing the quality and the quantity of the strategies might help to get a better insight into how well learners processed the learning contents (e.g., Glogger et al., 2012). Thus, future studies should investigate learners’ strategy use with respect to their quality and quantity. Also, we focused, as most previous research, on the strategy use rather than self-regulation knowledge (cf. e.g., Gidalevich & Kramarski, 2019). Future research could investigate how learners’ strategy knowledge develops when prompted over a longer period.

Moreover, it is possible that in university settings, the method of writing a learning journal is insensitive to analyse metacognitive learning strategies. As learners are used to write summaries, applying cognitive strategies while writing a learning journal should feel natural. Writing about metacognitive processes, however, might be unfamiliar and unintuitive to learners. In computer-based learning scenarios, the think-aloud method has successfully been used to measure learners’ metacognitive activities (for an overview Azevedo et al., 2010). In the future, methods should be used to sensitively assess the quality and quantity of learners’ strategy use.

Finally, our study has practical implications, especially for teaching university classes with a high amount of freshman students. Results of the present study support the use of prompts in learning journals short-term as a follow-up activity for university courses. However, prompts need to be carefully designed to support productive self-regulations processes. In modern digital learning environments, they could even be adaptable to learners needs and progresses (e.g. Guo, 2022). Thus, prompts should activate learning strategies during learning that match the level of educational objectives assessed during exams. Further, more direct instructional interventions, e.g. training, mentoring, or feedback, should be used if practitioners want to increase self-efficacy at the beginning of the learner’s life at university.

Conclusion