Abstract

There have been many destructive pluvial and fluvial floods in Poland and the projection of increasing flood hazards in the future is a reason of considerable concern. The maps of river hazard zones are changing over time, and understanding these changes is of primary importance for flood risk reduction and climate change adaptation. This article aims to assess the impact of climate change on the spatial extent and depth classes of flood hazard zones for a selected reach of the River Warta in the western part of Poland. To this end, we integrated the Soil & Water Assessment Tool (SWAT) hydrological model of the Warta River Basin with the 1D hydraulic model HEC-RAS of the selected reach. The climate change effect was quantified based on the coupled model simulations forced with bias-corrected projections from the EURO-CORDEX project. Flood hazard maps were developed for two townships along the River Warta (Oborniki and Wronki), three greenhouse gas concentration scenarios (one for the baseline scenario in the reference period, 1971–2000; one for RCP 4.5 and one for RCP 8.5, for the time horizon 2021–2050) and for three return periods (10-, 100- and 500-year floods). Based on the ensemble mean, the increase in the flooded area projected in the future is more pronounced for RCP8.5 than for RCP4.5. This unique combination of software and data enabled the transformation of climate change impact into the land surface part of the hydrological cycle and assessment of changes in flood hazard and opens the way to assess the potential increases in the economic losses in the future.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Floods are natural disasters that trigger significant environmental and human problems worldwide. Damages caused by extremely large floods might be huge and even irreparable. Moreover, over several decades, economic and environmental losses due to floods have significantly increased (Mohleji and Pielke Jr 2014). This can be explained for at least two reasons. Firstly, due to more frequent and heavier rainfall events observed around the globe in the warming climate (Gu et al. 2017), and secondly, due to the increasing population and the value of assets exposed to floods as a consequence of socio-economic development (Winsemius et al. 2018).

In Poland, floods are the most destructive natural extreme events, costly in both environmental and socio-economic terms (Baran-Zgłobicka et al. 2021; Kalbarczyk and Kalbarczyk 2024). They can result from various generating mechanisms, like intense, long-lasting precipitation (possibly amplified by saturated ground), snowmelt, ice jams, or coastal storms. The July 1997 river (fluvial) flood, predominantly on the River Odra and its tributaries, was the most destructive, all-time natural event in Poland, with 55 fatalities and approximately 2.4% GDP damage (equivalent to 3.6 billion USD), cf. Biedroń and Bogdańska-Warmuz 2012. It is a robust finding that for every 1 °C warming, the atmosphere can hold approximately 7% more water vapor, so that precipitation intensity increases. However, also other atmospheric processes, such as local moisture availability, wind patterns, and dynamics of weather systems, play a role in determining actual rainfall intensity. In recent decades, heavy precipitation spells have been recorded many times in Poland, leading to numerous flash and urban floods (Kundzewicz and Pińskwar 2022).

In general, flood risk combines the consequences of flood hazard, exposure, and vulnerability. European Union’s Floods Directive (EC 2007) was introduced in response to extensive inundations, such as the Odra flood in the Czech Republic, Poland, and Germany in July of 1997, as well as floods on many rivers (including the Elbe and the Danube) in August of 2002. The EU Floods Directive explicitly obliges the EU Member States to prepare flood risk and damage maps and flood risk management plans. Flood hazard maps provide information about flood extent, water depth, and flow velocity and serve as an essential tool enabling a quick visualization of the potential spatial impact of a river flood over a particular area. Finally, based on flood hazard maps, technical measures can be undertaken in advance to mitigate flood consequences. Since the introduction of the EU Floods Directive, Poland has suffered two more major river floods (2010 and September of 2024) and many flash and urban floods occurring in Polish towns almost every summer.

The calculation methods of flood hazards are diverse and depend on the available datasets. However, regardless of the selected approach, the conceptual framework is rather general and follows three significant steps. In the first step, flood quantiles for different probabilities (e.g., p = 1% for a 100-year flood) are calculated, using either observed flow time series from gauging stations or (in case of absence of such records) flow simulations from hydrological models. In a subsequent step, hydrodynamic models of flood wave propagation are used to translate flood quantiles into maximum water levels. Finally, in the last step, the flooded area for a specific return period is determined by combining model-derived maximum water levels with a digital elevation model (DEM), and a flood hazard map is created (de Moel et al. 2009).

Concerns about hydro-climatic extremes and their consequences are rising as climate change is expected to most likely exacerbate flood risk around the world (Wilhelm et al. 2022). Great attention to potential flood risk consequences was raised in consecutive reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), including the most recent AR6 report (Seneviratne et al. 2022), which conveys the message that the increase in heavy precipitation is projected for the future at the global and continental, including European, scales. Another chapter of the IPCC AR6 Report (Douville et al. 2021) states that large floods are projected to become more extreme, even if the link between precipitation and flooding is generally complex. Therefore, research exploring flood risk changes is essential and plays a vital role in helping humans adapt to and cope with the impacts of climate change.

Extreme precipitation is also projected to increase with the warming in Poland. For example, maximum 24 h precipitation totals are projected to increase both under RCP4.5 and 8.5 future greenhouse gas emission trajectories throughout the 21st century (Pińskwar and Choryński 2021). This leads to an increasing risk of pluvial (flash and urban) flooding (Kundzewicz and Pińskwar 2022). However, even if pluvial floods are on the rise in the country, the signal in projections of fluvial (river) flooding is complex. For instance, Piniewski et al. (2017c) found an increase in spatially varied projections of high flow indicators, with the highest increase projected in small and medium-sized lowland rivers in the inner part of the Vistula and Odra basins. Increases in different flood quantiles were also reported by Osuch et al. (2017) across nine catchments located across of Poland. Di Sante et al. (2021) reported an increasing magnitude of future 100-year floods for Poland for EURO-CORDEX-driven projections. Still, the robustness and magnitude of increases were lower than for catchment-scale studies.

There are many scientific publications demonstrating projections of changes in flood risk at a range of spatial scales, from global to continental (Kundzewicz et al. 2017) to regional and local. Numerous regional and catchment-based studies of projections of future flood hazard and flood-risk change where results of climate models were fed to hydrological models are reported worldwide (Aich et al. 2016; Barman et al. 2023; Condon et al. 2015; Lastrada et al. 2020; Liu et al. 2024; Sharma et al. 2021). However, hydrological models may only provide future estimates of some flow statistics but not relevant properties for flood risk assessment, such as inundation area and depth. Deriving them requires coupling of hydrological and hydrodynamic models, which has been far less common in scientific literature to date (Doroszkiewicz et al. 2019; Hayat et al. 2021). Doroszkiewicz et al. (2019) coupled a rainfall-runoff HBV model with a hydrodynamic 1D MIKE11 model for a small mountainous catchment in southern Poland, reporting increases in annual maximum inundation areas.

The objective of this study is to assess the effect of climate change on the spatial extent and depth classes of flood hazard zones for a 39 km reach of the River Warta (Poland). To meet this objective, we coupled a hydrological SWAT model with a hydrodynamic HEC-RAS model and used this modeling chain to propagate dynamically downscaled and bias-corrected climate change scenarios for the time horizon up to 2050. Such a combination of a hydrological and a hydrodynamic model in climate change projections is a methodological novelty.

While many climate change studies focus on the atmospheric part of the hydrological cycle, we propose a method to transfer these impacts to the land surface and use existing methodologies to assess changes in flood hazard. In the present paper, we deliver a detailed map of inundated areas in two examined localities on the River Warta for the historical reference period (1971–2000) as well as for two scenarios (RCP 4.5 and 8.5) in a future horizon, 2021–2050.

2 Materials and Methods

2.1 Study Area

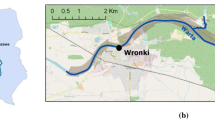

We analyze a reach in the middle course of the River Warta, Poland’s third largest river. The River Warta’s length is 808 km, and its basin area is 54,529 km2. The modeled reach of the River Warta is 39 km, extending from Oborniki to Wronki. There are three gauge stations in the area: Oborniki and Wronki on the River Warta and Kowanówko on the River Wełna, a Warta’s tributary flowing into the River Warta downstream of Oborniki (Fig. 1). The watershed area of the reach varies from 26,822 km2 at the inlet to 30,661 km2 at the outlet, the majority of the land use in the entire Warta catchment is classified as “Agricultural areas” (60%), followed by “Forest and seminatural areas” (33%). The land-cover characteristics of the areas on both sides of the investigated reach of the River Warta differ from those of the entire catchment. The majority of land cover there is forest and semi-natural areas (48%), but the fraction of agricultural areas is almost the same (46%). The class of artificial surfaces along the reach is small (5%) but particularly important from the flood protection point of view. Three towns are located along the modeled reach of the Warta: Oborniki, Obrzycko, and Wronki. Both the Warta and the Wełna rivers have sandy bottoms. No dikes are installed along the Warta, and the Wełna reaches in this part of their courses except for regulations in Wronki town. The width of the Warta River channel varies slightly along the reach, with an average between 80 and 90 m. The maximum depth of bankfull discharge varies within 3–4 m, and the average bottom slope is about 0.17‰. There are seven bridges along the analyzed reach.

Two representative control areas corresponding to Oborniki and Wronki townships, denoted as A and B, were chosen, and two control cross-sections were specified (Fig. 1). The areas represent potentially the most significant flood losses due to the concentration of wealth and population density.

At the Oborniki gauge station, the river flows varied from the absolute minimum of 26.8 m3/s to the absolute maximum of 806.0 m3/s, with an annual mean of about 112 m3/s. In the Wronki gauge station, these values are slightly higher, 37.2 m3/s, 928 m3/s, and mean 122 m3/s, respectively, and for the Kowanówko gauge station 0.53 m3/s, 96.4 m3/s and 8.6 m3/s, respectively. The flood flows may be several times higher than typical flows.

The last major river flood episode on the River Warta was recorded in May 2010. The spring 2010 flood on the Warta, and in much of Poland (especially in the Basin of the Vistula), was caused by heavy rainfall under high antecedent soil moisture contents. Later in the same year, in December 2010, alarm threshold stages on the River Warta, in both Oborniki and Wronki, were also exceeded due to ice phenomena. Dysarz et al. (2019) noted that dangerous flooding on the Warta in Wronki occurs every 2–5 years. The most dramatic floods occurred there in 1979; further flood events were recorded in 1975, 1981, and 2011.

2.2 Input Datasets

The primary input data applied in this research were: (1) GIS data (Digital Terrain Model (DTM) and Database of Topographic Objects); (2) hydrometric data - measurements of cross-sections and bridges; (3) hydrological data (daily flow records). The DTM obtained from the Head Office of Geodesy and Cartography (GUGiK) was prepared based on the airborne laser scanning LIDAR. The applied DTM stored in ESRI GRID format had a 1 m resolution, while the vertical accuracy was 0.15 m for urbanized areas and 0.3 m for forests. To reconstruct the river bathymetry, the data obtained from the ISCPEH project (Information System for Country Protection against Extraordinary Hazards, Polish acronym: ISOK) were used (KZGW). Thirty-five cross-section measurements along the analyzed reach were made. The average distance between them is about 1100 m. There are also measurements of seven bridges. The short reach of the River Wełna, for which four cross-sections with an average distance of 305 m were available, was modeled as a tributary of the main reach. The measurements of the two bridges in the Wełna outlet were also included. The hydrological data consists of daily river flows at mentioned gauge stations. The data available for 1971–2017, comprising 47 hydrological years, were obtained from IMGW-PIB (Institute of Meteorology and Water Management – State Research Institute).

2.3 Soil and Water Assessment Tool (SWAT) Model

Simulations from the SWAT model were used to assess the effect of climate change on river flows in three selected cross-sections in the Warta catchment. The model was previously calibrated and validated for the Vistula and Odra basins (VOB) (Piniewski et al. 2017b), driven by the bias-corrected climate change projections from the EURO-CORDEX dataset (Mezghani et al. 2017), and stored in a publicly available database (Piniewski et al. 2017a). The SWAT model is a process-based, semi-distributed, hydrological model simulating the water balance, and streamflow on a catchment scale (Arnold et al. 1998). It is a suitable tool for investigating the interaction between climate, land use, and water quantity. It enables simulation of long-term impacts of climate change on water flow extremes and flood hazards in catchments with varied topography, land use, and soils. The SWAT model developed by Piniewski et al. (2017b), which was used in this study, has undergone extensive, multi-site calibration and validation, including 110 flow gauges distributed uniformly across the VOB. The model domain was partitioned into 2633 sub-basins for which daily flow hydrographs can be extracted. Three gauge stations in the Warta River Basin selected in our study overlapped spatially with the VOB SWAT model sub-basin outlets. Only one of them (Kowanówko) was included in the calibration protocol reported by Piniewski et al. (2017b). Therefore, the model performance in the remaining two gauging stations was evaluated using the Kling-Gupta efficiency (KGE) (Gupta et al. 2009) in the present study. The SWAT model performance measured by KGE was found satisfactory for all three cross-sections. For Kowanówko, KGE values were 0.66 (calibration) and 0.71 (validation), whereas for Oborniki 0.72 (calibration) and 0.68 (validation), and for Wronki 0.73 (calibration) and 0.72 (validation).

Satisfactory model performance for the historical flows in the selected cross-sections allowed to use the future projections of daily flows driven by the downscaled EURO-CORDEX model ensemble (Piniewski et al. 2017c). Projected river flow time series were then used to estimate the 10-, 100-, and 500-year floods (see Section 3.2).

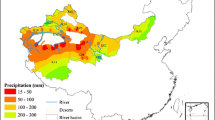

2.4 Climate Change Scenarios

To estimate the future climate change effect on river flows, the SWAT model was driven by climate forcing data at a 5-km resolution from the CHASE-PL Climate Projections dataset (Mezghani et al. 2017). The climate multi-model ensemble consisted of nine GCM-RCM combinations for two Representative Concentration Pathways (RCPs): 4.5 and 8.5 for 2021–2050. For a baseline scenario, which determines a reference point for the projected climate changes, historical (1971–2000) climate model data was used. The quantile mapping method was applied as a bias correction procedure to reduce systematic bias in climate models (Gudmundsson et al. 2012). According to the projections, precipitation in the analyzed region is expected to increase. Projections for two RCPs show a similar direction of change in the future. However, a more pronounced increase is projected for the RCP8.5. Assuming RCP4.5, an increase in average annual mean precipitation by 5% is expected to occur, whereas for RCP8.5 by 8%. The projected mean annual temperature in the region is expected to rise by approximately 1.2 °C above the baseline under the RCP4.5 and by 1.4 °C for RCP8.5.

Before assessing projected climate change impact on maximum river flows can be made, it is essential to determine if the reference point (baseline scenario) mimics maximum observed flows with reasonable accuracy. To this end, we compared the SWAT-based estimations of 10-, 100- and 500-year floods for the reference period 1971–2000 for every climate model from the ensemble based on observations from flow gauging stations in each cross-section.

2.5 Estimation of Flood Quantiles

The flood quantiles were calculated according to statistical methods considered as a Polish standard (KZGW 2017). The Pearson distribution of type III was applied. The calculations were done for three gauging stations considered in this article. The methodology was used to determine three selected flood quantiles, Q10%, Q1%, and Q0.2%, corresponding to recurrence intervals of 10, 100, and 500 years, which are recommended for the preparation of the flood hazard maps by the water authorities in Poland (KZGW 2017). Since the selection of return periods in EU Member States was left to individual States, flood quantiles selected in other countries may differ from Poland. The computational process was first applied to the raw historical data observed in the above-mentioned three gauge stations for 1971–2013. Then, it was applied to 27 scenarios (nine for 1971–2000 and 18 for 2021–2050) obtained from climate models (Figure S1 - Supplementary material).

2.6 River Flow Model – HEC-RAS

A well-known, one-dimensional hydrodynamic model for rivers and water reservoirs, called the HEC-RAS model, was applied in this research, cf. Brunner 2016. In general, 1D and 2D models are used in the studies on flood hazard. In this part of the research, the choice of the software follows Polish regulations, which recommend using 2D models only for specific cases like dike breaks, large cities, etc. Despite the incredible computer development and increased computational power, the 2D simulations are still long-lasting processes and can be applied only for limited areas. The HEC-RAS model is typically used to simulate flow and transport processes in river networks, including floodplains and reservoirs. The modeled flow conditions include steady and unsteady longitudinal flow. The former was applied using the simple energy balance equation to the presented research. The essential elements of the model are terms representing the potential energy of the stream, work of pressure forces, and kinematic energy of the stream, as well as friction losses due to bed and bank influence on flowing water. It also includes the effects of channel contraction and extension. Supplied with the water elevation of the depth in the outlet cross-section, it enables calculation of the depth along the entire channel. In such computations, the discharge plays the role of the equation parameter. The mentioned features make HEC-RAS a very good tool for implementation of EU Flood Directive recommendations (Yannopoulos et al. 2015). For a more detailed description of this model and its implementation, see Brunner (2016).

In the presented research, the reach of the River Warta, shown in Fig. 1, was modeled with HEC-RAS. The base geometry was common for all models and was prepared based on the data read from GIS layers, managed with ArcGIS 10.5.1 developed by ESRI Inc. (Law and Collins 2018) and supported by two additional plug-ins, namely RiverBox (Dysarz 2018) and HEC-GeoRAS (Cameron and Ackerman 2012). The final model consists of 245 computational cross-sections and nine bridges. It was calibrated based on the historical data. The observed and simulated flow hydrographs in the Wronki gauge station were the basis for calibration. The obtained correlation coefficient varied from 0.996 to 0.999, while the total square error was between 0.134 and 0.330. The entire process is described in Dysarz (2020).

2.7 Flood Hazard Zones and Indicators

The SWAT-generated daily river flow time series were classified as one of three variants: (1) baseline, covering the period from 1971 to 2000; (2) nine different GCM-RCMs under RCP4.5; and (3) nine different GCM-RCMs under RCP8.5. In the next step, the 10-, 100-, and 500-year flood quantiles derived from SWAT-simulated flow time series were applied as a basis for steady flow calculations in HEC-RAS. The reason for such a choice is the simplicity of linking hydrodynamic calculations with the GIS software, e.g., ArcGIS, QGIS. The Python scripts were applied to (a) control HEC-RAS simulations (Goodell 2014); (b) transform the results from HEC-RAS specific formats to GIS formats (Dysarz 2018); and (c) generate flood hazard maps (Dysarz et al. 2019).

The computational procedure was automated with scripts written in the Python language (Foundation 2019). The application of ArcPy was aimed at transforming the simulation results into flood hazard maps and then processing these maps. The results obtained from hydrodynamic modeling and geoprocessing are maps of water depths. There were 81 maps generated in this study covering the region under investigation (three sets of nine climate models times three flood quantiles). One additional map represented historical conditions based on observation records. The processing of the results included three steps: (1) averaging water depth rasters across nine ensemble members for each RCP and flood quantile (during this stage of the process, each cell within the raster data was deemed flooded if it experienced flooding in at least 5 out of 9 simulated scenarios); (2) classification of averaged water depths into depth classes routinely used in the flood hazard maps in Poland (for 0.5, 2.0 and 4.0 m thresholds) (KZGW 2017); and (3) zooming into control areas A and B (Fig. 1).

3 Results

3.1 Maximum Flows

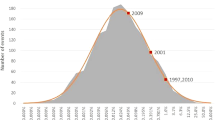

A comparison of flood quantiles derived from the SWAT model forced with RCM simulations and feeding into HEC-RAS with those derived from observation records for three gauging stations is shown in Fig. 1. The maximum flow values calculated based on the observed series of annual maximum discharge for all exceedance probabilities fall precisely into an interquartile range of SWAT-simulated ensemble of flood quantiles. Errors for the simulated flows were in the range of 2–9%, indicating satisfactory agreement. Thus, using SWAT model simulations to calculate future maximum flows is reasonable and justified.

As shown in Fig. 1, future flood quantiles are projected to increase for both gauges on the River Warta, for both considered RCPs. The figure also shows that the spread of flood quantile projections rises with decreasing exceedance probability, both in absolute and relative terms. However, several curves on the graphs are clustered, and just a few (1–3) look like outliers.

3.2 Flood Risk Assessment

Flood hazard maps (with 10-, 100- and 500-year return periods) for the baseline scenario and future time horizons were presented for two selected regions along the River Warta in Fig. 2 and Figures S2-3 (Supplementary material). The maps were derived based on ensemble mean water depths described in Section 2.3–2.7. As expected, the total flooded area in the historical period increases with maximum flow value from 352 km2 (Q10%) to 837 km2 (Q1%) and 1065 km2 (Q0.2%) (Fig. 3). The flood extent is variable and depends on the flooded terrain’s topography (represented by DEM).

Considering the climate change effect on the entire study reach, for all three maximum flow quantiles (Q10%, Q1%, and Q0.2%), the flood extent increases in future projections based on the ensemble mean, and the increase is more pronounced for RCP8.5. For a 10-year flood, the flooded area is projected to increase from the reference value by 40% (to 492 km2) under the RCP4.5 and by 65% (to 582 km2) under RCP8.5. For a 100-year flood, the increase of flooded area for the two corresponding scenarios is 14% (to 953 km2) and 18% (991 km2), while rates of relative increase for a 500-year flood are projected to reach 10% (to 1174 km2), and 14% (to 1223 km2), for RCP4.5, and 8.5, respectively (Fig. 3).

Flood hazard maps, besides the flood extent, allow the assessment of water depths of the flooded area, which in the present study were classified according to guidelines of KZGW (2017). Historically, the fraction of area with inundation depth between 0.5 and 2 m dominates for every flood quantile (Fig. 3). Water depths higher than 2 m cover the smallest area for a 10-year flood (approx. 13%), being over twice as high for a 100-year flood (29%) and the highest for a 500-year flood (39%). Mean water depths for the entire flooded area in the analyzed regions vary from 0.99 m (Q10%) to 1.44 m (Q1%) and 1.84 m (Q0.2%). Both flood area and water depths were noted to increase visibly with maximum flow value.

For future time horizons, directions of changes in the share of flood depth classes are positive for all flood quantiles, with slight differences in the magnitude of change (Fig. 3). Generally, a gradual increase in the share of depth class < 0.5 m and a decrease in the remaining classes is noted for both scenarios.

Climate change effect on the total flooded area extent for a 10-year flood (A), a 100-year flood (B), and a 500-year flood (C) for the entire study reach of the River Warta. Graph bars are portioned into depth classes following the symbology from Fig. 2. The results are based on ensemble mean water depths

4 Discussion

Flood quantiles derived from the SWAT model forced with RCM simulations feeding into the HEC-RAS model were compared with observed flow quantiles at three gauging stations. Because a satisfactory agreement was found, using SWAT model simulations to calculate future maximum flows can be considered plausible and justified.

As expected, the water stage greater than 2 m in the historical baseline period increases with the return period, from the smallest fraction of the inundated area of approximately 13% for a 10-year flood to 29% for a 100-year flood to 39% for a 500-year flood. Also, mean water depths for the entire flooded area in the analyzed regions increase with the return period, from 0.99 m (Q10%) to 1.44 m (Q1%) and 1.84 m (Q0.2%), corresponding to return periods of 10, 100, and 500 years.

A set of 18 flood hazard maps - for two localities, three greenhouse gas concentrations (one for the baseline scenario in the reference period, 1971–2000; one for RCP 4.5 and one for RCP 8.5 (for the time horizon 2021–2050) and for three return periods (10-, 100- and 500-year) were presented for ensemble mean water depths. The total flooded area in the baseline historical period increases with a return period of maximum flow value, from 352 km2 (Q10%) to 837 km2 (Q1%) and 1065 km2 (Q0.2%).

For all three maximum flow quantiles (Q10%, Q1%, and Q0.2%), the flood extent is projected to increase in the future, based on ensemble mean, and the increase is more pronounced for RCP8.5 than RCP4.5. For a 10-year flood, the flooded area is projected to increase by 40% (to 492 km2) under RCP4.5 and 65% (to 582 km2) under RCP8.5. For a 100-year flood, the increase of flooded area for the corresponding scenarios is 14% (to 953 km2), and 18% (991 km2), while for a 500-year flood, it is 10% (to 1174 km2), and 14% (to 1223 km2), for RCP4.5, and 8.5 respectively.

A gradual increase in the share of depth class < 0.5 m and a decrease in the remaining classes is noted for both future scenarios. In contrast, mean water depths of the flooded area in future time horizons are projected to decrease, accompanying the increase of inundated areas.

Although the coupling of hydrological and hydrodynamic models to simulate flood hazards under changing climate has been reported in the literature (Doroszkiewicz et al. 2019; Hayat et al. 2021; Robi et al. 2019), it still has not received the broader attention it deserves. Typically, the modeling scheme in such studies includes (bias-corrected) climate projections, hydrological modeling, hydraulic/hydrodynamic modeling, and flood mapping (Oubennaceur et al. 2021). Besides the differences in the use of climate models and modeling tools, different approaches to calculating flood frequency are evident, which highly impact the final flood extent. Flood hazard mapping requires flood frequency analysis to extract flow values for various return periods and exceedance probability. The range of recurrence intervals reported in studies worldwide is extensive but usually includes 2-100 years (Hayat et al. 2021; Oubennaceur et al. 2021). In European Union countries, due to the Floods Directive implementation (EC 2007) flood hazard mapping should consider flood events with low, medium, and high probability of occurrence. According to a review by Nones (2015) individual EU countries use different return periods to describe each flood type, and the overall span ranges between 5 years (high probability) and 1000 years (low probability). In Poland, 0.2% (500-years return period), 1% (100-years return period), and 10% (10-years return period) exceedance probabilities are used for low, medium, and high probability design floods, respectively. In some studies, empirical flood frequencies are calculated directly from flow hydrographs simulated by a hydrological model (Hayat et al. 2021). However, for very low flood frequencies (like 0.2% in our study), theoretical probability curves prepared following the nationally authorized methods, such as the one of KZGW (2017) in Poland, are more suitable.

While the results presented in this paper have been obtained for ensemble mean water depths, it is necessary to stress that uncertainty can be considerable. It can stem from a range of sources, such as uncertainty of historical information and data sets (used to calibrate the model), uncertainty of climatic scenarios for the future (depending on the efficiency of implementation of international climate policy), uncertainty of climate models (both General Circulation Models / Global Climate Models and Regional Climate Models and the assumptions made in downscaling and bias correction), and uncertainty of hydrological models (Kundzewicz et al. 2018). To ensure reliability, we employed a combination of well-established hydrological (SWAT) and hydraulic (HEC-RAS) models, both of which have been widely validated and are commonly used in flood risk assessment. Our methodology includes the usage of an ensemble of bias-corrected climate projections from the EURO-CORDEX dataset. This approach allows us to account for uncertainty in future climate scenarios by integrating multiple climate models, providing a comprehensive range of potential outcomes. The procedure was further validated by comparing simulated flood quantiles with observed data from gauging stations in the study area. The high degree of agreement between modeled and observed flood events strengthens the credibility of our forecasting process.

5 Conclusions

Many destructive pluvial and fluvial floods have hit Poland, and projections for the future warmer climate indicate increasing flood hazards. In this article, we assessed climate change impact on the spatial extent and depth classes of flood hazard zones for a selected reach of the River Warta in the western part of Poland. Integration of the SWAT hydrological model of the Warta River Basin with the 1D hydraulic model HEC-RAS of the selected reach and use of this modeling chain for propagating dynamically downscaled and bias-corrected climate change scenarios for the time horizon up to 2050, is a novelty, of practical relevance. Such an approach enables direct assignment of the climate change scenarios with increased flood hazard and, in further steps, with potential economic losses. In the present paper, we deliver detailed maps of inundated areas determined via modeling for two examined localities on the River Warta for the historical reference period (1971–2000) as well as for two greenhouse gas concentration scenarios (RCP 4.5 and 8.5) in a future horizon, 2021–2050, for three return periods (10-, 100- and 500-year floods). Based on the ensemble mean, the flooded area is projected to increase, which is more pronounced for RCP8.5 than RCP4.5.

One of the main limitations of the estimation of flood hazard maps using a coupled hydrological-hydrodynamic modeling approach under climate change is still the computational burden related to a high number of runs of hydrological and hydrodynamic models amplified by potentially high numbers of forcings from climate models and considered emission scenarios. Future studies could, therefore, also consider alternative methods for future flood hazard map estimation, such as using lumped-parameter emulators of hydrodynamic models (Doroszkiewicz et al. 2019), runoff correction or lookup methods, applicable only at large scale (Kimura et al. 2023), or GIS methods combined with multi-criteria decision analysis (Toosi et al. 2020).

There are considerable differences in projections of river flood risk in Europe reported in various studies (Kundzewicz et al. 2017). The consistency of flood projections in Poland is lower than in some other regions, such as the British Islands, where the vast majority of studies indicate increases. Therefore, the present article can improve the understanding of flood risk changes in Poland’s study area, which is needed for flood risk management plans that must be regularly updated in line with the EU Floods Directive.

References

Aich V, Liersch S, Vetter T, Fournet S, Andersson JC, Calmanti S, van Weert FH, Hattermann FF, Paton EN (2016) Flood projections within the Niger River Basin under future land use and climate change. Sci Total Environ 562:666–677

Arnold JG, Srinivasan R, Muttiah RS, Williams JR (1998) Large area hydrologic modeling and assessment part I: model development. J Am Water Resour Assoc 34(1):73–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-1688.1998.tb05961.x

Baran-Zgłobicka B, Godziszewska D, Zgłobicki W (2021) The flash floods risk in the local spatial planning (case study: Lublin Upland, E Poland). Resources 10(2):14. https://www.mdpi.com/2079-9276/10/2/14

Barman D, Baruah A, Arjun BM, Aggarwal SP (2023) Hydrological-hydrodynamic nexus for predicting flood plain inundation: a case study in Pagladiya-Putimari catchment. India. Arab J Geosci 16(9):526. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12517-023-11620-w

Biedroń I, Bogdańska-Warmuz R (2012) Powódź 2010-analiza strat i szkód powodziowych w Polsce. Gospodarka Wodna 4:147–153

Brunner GW (2016) HEC-RAS river analysis system: hydraulic reference manual, version 5.0. US Army Corps of Engineers–Hydrologic Engineering Center, 547

Cameron T, Ackerman PE (2012) HEC-GeoRAS GIS tools for support of HEC-RAS using ArcGIS user’s manual. US Army Corps of Engineers, Institute for Water Resources, Hydrologic Engineering Center (HEC). http://www.hec.usace.army.mil/software/hec-georas/documentation/HEC-GeoRAS_43_Users_Manual.pdf

Condon L, Gangopadhyay S, Pruitt T (2015) Climate change and non-stationary flood risk for the upper Truckee River basin. Hydrol Earth Syst Sci 19(1):159–175

de Moel H, van Alphen J, Aerts JCJH (2009) Flood maps in Europe –methods, availability and use. Nat Hazards Earth Syst Sci 9(2):289–301. https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-9-289-2009

Di Sante F, Coppola E, Giorgi F (2021) Projections of river floods in Europe using EURO-CORDEX, CMIP5 and CMIP6 simulations. Int J Climatol 41(5):3203–3221

Doroszkiewicz J, Romanowicz RJ, Kiczko A (2019) The influence of flow projection errors on flood hazard estimates in future climate conditions. Water 11(1):49. https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4441/11/1/49

Douville H, Raghavan K, Renwick J, Allan RP, Arias PA, Barlow M, Cerezo-Mota R, Cherchi A, Gan TY, Gergis J (2021) Water cycle changes.

Dysarz T (2018) Development of RiverBox—An ArcGIS toolbox for river bathymetry reconstruction. Water 10(9):1266

Dysarz T (2020) Development of methodology for assessment of long-term morphodynamic impact on flood hazard. J Flood Risk Manag 13(4):e12654

Dysarz T, Wicher-Dysarz J, Sojka M, Jaskuła J (2019) Analysis of extreme flow uncertainty impact on size of flood hazard zones for the Wronki gauge station in the Warta river. Acta Geophys 67(2):661–676

EC (2007) Directive 2007/60/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council on the assessment and management of flood risks. Official Journal of the European Communities, Brussels

Foundation PS (2019) Python Standard Library, Python 3.6. 8 documentation

Goodell C (2014) Breaking HEC-RAS Code. A User’s Guide to Automating HEC-RAS

Gu X, Zhang Q, Singh VP, Shi P (2017) Changes in magnitude and frequency of heavy precipitation across China and its potential links to summer temperature. J Hydrol 547:718–731

Gudmundsson L, Bremnes JB, Haugen JE, Engen-Skaugen T (2012) Technical Note: Downscaling RCM precipitation to the station scale using statistical transformations– a comparison of methods. Hydrol Earth Syst Sci 16(9):3383–3390. https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-16-3383-2012

Gupta HV, Kling H, Yilmaz KK, Martinez GF (2009) Decomposition of the mean squared error and NSE performance criteria: implications for improving hydrological modelling. J Hydrol 377(1–2):80–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2009.08.003

Hayat H, Saifullah M, Ashraf M, Liu S, Muhammad S, Khan R, Tahir AA (2021) Flood hazard mapping of rivers in snow-and glacier-fed basins of different hydrological regimes using a hydrodynamic model under RCP scenarios. Water 13(20):2806

Kalbarczyk R, Kalbarczyk E (2024) Risk of natural hazards caused by extreme precipitation in Poland in 1951–2020. Water 16(12):1705. https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4441/16/12/1705

Kimura Y, Hirabayashi Y, Kita Y, Zhou X, Yamazaki D (2023) Methodology for constructing a flood-hazard map for a future climate. Hydrol Earth Syst Sci 27(8):1627–1644

Kundzewicz ZW, Pińskwar I (2022) Are pluvial and fluvial floods on the rise? Water 14(17):2612

Kundzewicz ZW, Krysanova V, Dankers R, Hirabayashi Y, Kanae S, Hattermann F, Huang S, Milly PC, Stoffel M, Driessen P (2017) Differences in flood hazard projections in Europe–their causes and consequences for decision making. Hydrol Sci J 62(1):1–14

Kundzewicz ZW, Krysanova V, Benestad R, Hov Ø, Piniewski M, Otto IM (2018) Uncertainty in climate change impacts on water resources. Environ Sci Policy 79:1–8

KZGW (2017) Aktualizacja metodyki obliczania przepływów i opadów maksymalnych o określonym prawdopodobieństwie przewyższenia dla zlewni kontrolowanych i niekontrolowanych oraz identyfikacji modeli transformacji opadu w odpływ. Stowarzyszenie Hydrologów Polskich, Warszawa

Lastrada E, Cobos G, Torrijo FJ (2020) Analysis of climate change’s effect on flood risk. Case study of Reinosa in the Ebro RiverBasin. Water 12(4):1114. https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4441/12/4/1114

Law M, Collins A (2018) Getting to know ArcGIS desktop. ESRI

Liu M, Ding Y, Shen Z, Kong Q (2024) Alternating iterative coupling of hydrological and hydrodynamic models applied to Lingjiang river basin, China. Nat Hazards. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-024-06797-6

Mezghani A, Dobler A, Haugen JE, Benestad RE, Parding KM, Piniewski M, Kardel I, Kundzewicz ZW (2017) CHASE-PL climate projection dataset over Poland–bias adjustment of EURO-CORDEX simulations. Earth Syst Sci Data 9(2):905–925

Mohleji S, Pielke R Jr (2014) Reconciliation of trends in global and regional economic losses from weather events: 1980–2008. Nat Hazards Rev 15(4):04014009

Nones M (2015) Implementation of the floods directive in selected EU member states. Water Environ J 29(3):412–418. https://doi.org/10.1111/wej.12129

Osuch M, Lawrence D, Meresa HK, Napiorkowski JJ, Romanowicz RJ (2017) Projected changes in flood indices in selected catchments in Poland in the 21st century. Stoch Env Res Risk Assess 31:2435–2457

Oubennaceur K, Chokmani K, Gauthier Y, Ratte-Fortin C, Homayouni S, Toussaint J-P (2021) Flood risk assessment under climate change: the petite nation river watershed. Climate 9(8):125. https://www.mdpi.com/2225-1154/9/8/125

Piniewski M, Szcześniak M, Kardel I (2017a) CHASE-PL—Future hydrology data set: projections of water balance and streamflow for the Vistula and Odra Basins, Poland. Data 2(2):14. https://www.mdpi.com/2306-5729/2/2/14

Piniewski M, Szcześniak M, Kardel I, Berezowski T, Okruszko T, Srinivasan R, Schuler V, D., Kundzewicz ZW (2017b) Hydrological modelling of the Vistula and Odra river basins using SWAT. Hydrol Sci J 62(8):1266–1289

Piniewski M, Szcześniak M, Kundzewicz ZW, Mezghani A, Hov Ø (2017c) Changes in low and high flows in the Vistula and the Odra basins: model projections in the european-scale context. Hydrol Process 31(12):2210–2225. https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.11176

Pińskwar I, Choryński A (2021) Projections of precipitation changes in Poland. In: Falarz M (ed) Climate change in Poland: past, present, future. Springer, pp 529–544

Robi MA, Abebe A, Pingale SM (2019) Flood hazard mapping under a climate change scenario in a Ribb catchment of Blue Nile River basin, Ethiopia. Appl Geomatics 11(2):147–160

Seneviratne SI, Adnan M, Badi W, Dereczynski C, Luca AD, Ghosh S, Iskandar I, Kossin J, Lewis S, Otto F (2022) Weather and climate extreme events in a changing climate. In: Masson-Delmotte V, Zhai P (eds) Climate Change 2021: the physical science basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, pp 1513–1766

Sharma S, Gomez M, Keller K, Nicholas RE, Mejia A (2021) Regional flood risk projections under climate change. J Hydrometeorol 22(9):2259–2274

Toosi AS, Doulabian S, Tousi EG, Calbimonte GH, Alaghmand S (2020) Large-scale flood hazard assessment under climate change: a case study. Ecol Eng 147:105765

Wilhelm B, Rapuc W, Amann B, Anselmetti FS, Arnaud F, Blanchet J, Brauer A, Czymzik M, Giguet-Covex C, Gilli A (2022) Impact of warmer climate periods on flood hazard in the European Alps. Nat Geosci 15(2):118–123

Winsemius HC, Jongman B, Veldkamp TI, Hallegatte S, Bangalore M, Ward PJ (2018) Disaster risk, climate change, and poverty: assessing the global exposure of poor people to floods and droughts. Environ Dev Econ 23(3):328–348

Yannopoulos S, Eleftheriadou E, Mpouri S, Giannopoulou I (2015) Implementing the requirements of the European Flood Directive: the case of Ungauged and poorly gauged watersheds. Environ Process 2(1):191–207. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40710-015-0094-2

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: DM-S, TD, Methodology: TD, MP, DM-S, JW-D, Software: TD, Validation: TD, Formal analysis: TD, JW-D, MP, PM, Investigation: TD, MP, PM, Writing - Original Draft: TD, MP, JW-D, PM, ZWK, Visualization: TD, PM, Supervision: ZWK, Project administration: TD, PM.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dysarz, T., Marcinkowski, P., Wicher-Dysarz, J. et al. Assessment of Climate Change Impact on Flood Hazard Zones. Water Resour Manage 39, 963–977 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11269-024-04002-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11269-024-04002-8