Abstract

Cooperatives are an important organizational form that operate under seven principles (Voluntary and Open Membership; Democratic Member Control; Member Economic Participation; Autonomy and Independence; Education, Training, and Information; Cooperation among Cooperatives; Concern for Community). Concern for Community was the last formally stated cooperative principle in 1995, after decades of discussion within the International Cooperative Alliance (ICA). The statement of this “new” principle has provoked questions for cooperatives and the cooperative movement more generally, regarding their definition, scope, and implementation. This article employs a systematic literature review to examine the academic understanding of Concern for Community that has emerged over the past 30 years. The review analyzes 32 academic journal articles from an initial dataset of 438 articles generated by a two-string search (“concern for community” and “cooperative principles”). Five themes are identified: cooperative principles, defining Concern for Community, adoption of Concern for Community, antecedents of Concern for Community, and outcomes. Comparing these themes with the normative instructions proposed by the ICA, the article develops a framework for future research. The review also finds that there is not an established clear difference between Concern for Community and corporate social responsibility in the extant literature, which carries the implication that constructs from the latter can be integrated into the analysis and development of the 7th principle.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

According to the International Cooperative Alliance (ICA 2024), cooperatives are autonomous associations of people aspiring to achieve their common economic, social, and cultural objectives “through a jointly-owned and democratically-controlled enterprises”. Today, cooperative businesses can be found in nearly all countries. There are estimated to be more than 1 billion individual members of over 3 million cooperatives in the world, operating in almost every sector of the economy, including agriculture, financial services, education, transportation, healthcare, housing, employment services, food retailing, and utilities (ICA 2023). According to the World Co-operative Monitor (2023), the top 300 cooperatives in the world reported a total turnover of more than $2,409 billion USD in 2021.

The cooperative model is built upon the premise of bringing people together to achieve a shared objective through the operation of a democratically controlled business entity. They train and educate their members and promote collective effort to address both individual and community needs, as well as create employment opportunities and build capital in communities where they are located (Nelson et al. 2016). Cooperatives are distinct from other forms of business entities, as they are organized around their fundamental values and seven specific principles established by the ICA in its Statement on the Co-operative Identity. “Co-operatives are based on the values of self-help, self-responsibility, democracy, equality, equity, and solidarity. In the tradition of their founders, co-operative members believe in the ethical values of honesty, openness, social responsibility and caring for others” (ICA 2016:ii). The seven ICA principles include: (1) Voluntary and Open Membership, (2) Democratic Member Control, (3) Member Economic Participation, (4) Autonomy and Independence, (5) Education, Training, and Information, (6) Cooperation among Cooperatives, and (7) Concern for Community.

The 7th principle, Concern for Community states that “co-operatives work for the sustainable development of their communities through policies approved by their members” (ICA 2016:85). Prior to its adoption by the ICA in 1995, concern for community was understood as implicit and implied in the existing cooperative principles. Following the Brundtland Report (1987), however, there was growing recognition that certain cooperative values, such as social responsibility and solidarity, could be more adequately represented with an additional principle. Since the adoption, the wording of the principles have been challenged for their clarity, leading to the development of a formal guidance of cooperative principles in 2016 (ICA 2016). Academic research has developed alongside, as a response, to understand both the principles and their impacts.

To assess the success of the 7th cooperative principle we conducted this systematic literature review. The review analyzes themes in the prevailing commentary and scholarship, evaluates the principle in relation to ICA norms, and establishes directions for future research. The Statement on Cooperative Identity adopted in 1995 is strongly rooted in normative values (Caceres & Lowe, 2000), which means that researchers must consider the social missions of cooperatives in addition to their economic goals. In this sense, our article seeks to address a significant gap in the literature, and to verify and compare how academia and the ICA understand the 7th principle. The cooperative model is built upon principles and the 7th principle is the only one clearly addressing the social role and objective of a cooperative. Consequently, we believe it is of extreme importance that the guidance and practice of the ICA (an independent and nongovernmental association that unites, represents, and serves cooperatives worldwide) is aligned to research-informed findings. Misinformation or disinformation around this principle will bring the cooperative movement into disrepute, because a cooperative might be considered as just another form of profit-driven firm with more partners.

Hence, our work provides a comprehensive review of academic publications that relate normative cooperative values to their socio-economic goals and compare them to the Guidelines published by the ICA, particularly around the 7th principle.

2 Methods

To fulfil the objective of assessing the state-of-art thinking from the academic discourse on Concern for Community as a cooperative principle, a systematic literature review (SLR) was undertaken, which is a method widely adopted in management and organization studies to explore complex and ambiguous phenomena to identify future research agendas (e.g., Clark et al. 2023; Santos et al. 2023; Vern et al. 2024). Notably, SLR has been adopted in recent research around sustainability and social responsibility (i.e., Johnson et al. 2023; Qamar et al. 2023; Yassin and Beckmann 2024).

With a comprehensive search in the Scopus database, the two search strings, “concern for community” and “cooperative principles” (in English, Spanish and Portuguese) generated 92 and 346 results, respectively. Five articles were removed due to lack of accessibility. The former was narrowed down to ten by limiting the results to business, social sciences, or interdisciplinary journals, and removing the majority of articles concerned with medical practice in which “concern for community” referred to a motivation for action, but had no conceptual definition. A further article was removed because it is not related to cooperatives. The latter, “cooperative principles” produced 346 results, which was narrowed down to 263 when limiting the results to business, social sciences, economics, or multidisciplinary journals. After analyzing several articles as a pilot, it became apparent that the same string was used in communications literature referring to language studies, largely with Grice (1975) as a source. As this work is irrelevant to our target articles, we excluded any citing Grice, providing 111 articles for review. Further exclusions were made for specific human cooperative behavior (cooperative principles unrelated to organizations), or principles other than “concern for community”, or legal aspects (principles in general). Following further full-text reading, eleven articles were excluded for their lack of relevance to cooperatives as an organizational form.

Therefore, the final pool of literature contains 32 articles, which are coded and categorized into five themes for in-depth thematic analysis.

Figure 1 presents the article selection and screening process. Table 1 indicates the five main themes with illustrative first-order codes from the final 32 papers’ research objectives and the findings.

To strength our findings and achieve the research aim, we applied additional codes from the ICA’s 2016 Guidance regarding cooperative principles into another theme to be incorporated in our discussion. This is summarized in Table 2.

3 Results & discussion

The literature on Concern for Community has grown considerably since 2016, while the first article mentioning this principle dates back to 1996. Applying the Scimago SJR criteria, we find only six papers (19%) in the first-quartile quality journals. Following principles of responsible research metrics (Anderson et al. 2021), we propose two factors affecting the chances of publication in higher ranked outlets. The first is language; nine (28%) are written in Spanish, diminishing the citation possibility. The second is the literature imbalance towards qualitative studies, 47% versus 19% quantitative, as the top-ranked business journals tend to publish more of the latter.

3.1 Cooperative principles

One set of articles (Miranda 2014, 2017, Nilson, 1996; Leca et al. 2014) focus mainly on the concept of cooperative principles - their development, their importance to cooperatives, and their classification as cooperative principles.

Presenting a historical evolution, Miranda (2014) suggests the ICA Vienna Congress in 1930 as the source of investigations into cooperative principles, where a number of principles were established and discussed: one member one vote; cash sales, dividends on the basis of volume bought; elimination of price benefits; dividends limited to capital; and political neutrality. Nevertheless, four years later in London, these universal cooperative principles were amended. Three mandatory principles (i.e., free membership, democratic control, and dividends based on patronage and capital) were approved along with several action and organization methods (e.g. political and religious neutrality, cash sales, and education). Then, at the ICA Paris Congress in 1937, it was resolved that an authentic cooperative should follow four principles: free membership, democratic control, dividends based on transactions and limited interest on capital, and political and religious neutrality. Cash sales and education, even though considered important, were regarded as secondary (Miranda 2014). A period of discussion commenced at the ICA Bournemouth Congress in 1963, leading to the inclusion of the principle of Cooperation among Cooperatives in the 1966 Vienna Congress. This was executed in honor of the Rochdale pioneers, who were determined to collaborate in developing a cooperative colony and be self-sufficient. Consensus at the ICA Manchester Congress 1995 mandated that henceforth all principles be treated as core commitments and cooperatives be evaluated against all of them (ibid.).

By definition, a principle is a structured system of ideas, thoughts or norms that subordinate all other ideas, thoughts and norms (Miranda 2017). Further, a principle is no guarantee of better economic, political or social conditions, but merely a moral guide (ibid.), so, it is essentially a moral framework that ought to steer attitudes and behaviors in an organization. Nilsson (1996) categorizes principles into (1) business principles, describing relationships among members (such as cooperation between cooperatives, concern for community, autonomy and independence), and (2) society principles, dealing with the social dynamics of cooperation (such as voluntary and open membership, member control, and member economic participation, education, training, and information). Therefore, Concern for Community is regarded as a business principle, in fact one that reduces transaction costs or addresses market failures (ibid.).

According to Miranda (2017), principles are mandates of optimization, which means that they are normative and must be carried out to the greatest extent that is legally and practically possible. In practice, principles are optimized in a recursive way and can be viewed as rules that optimize behaviors (ibid.). Specifically, cooperative principles are “rules stating how the cooperative society/enterprise shall behave in relation to its members and how the members should behave in relation to each other” (Nilsson 1996:647). In a minimal definition, following the principles of user-ownership, user-control, and user benefit are necessary and sufficient to define an organization as a cooperative (Nilsson 1996). In other words, principles are the cornerstone and a distinctive characteristic of cooperative organizations.

While Miranda (2017) takes principles as antecedents of behaviors with no a priori end state other than the fulfillment of themselves, Nilsson (1996) also understands principles, at least cooperative principles, as a means to reduce transaction costs for cooperative organizations. Cooperative principles guide the institutional expression of cooperative values, and while cooperative values are espoused by individual members, cooperative principles are attributes of cooperative organizations (Nilsson 1996). In contrast, Miranda (2014) proposes that cooperative principles are enactment of or the practical expression of cooperative values, thereby they guide behavior. The key difference between the two authors is that Nilsson (1996) understands values as individual and principles as organizational characteristics, while Miranda (2014) does not make this distinction.

To focus on members’ individual values in isolation from their corporate grounding can lead to a common mistake, which “is to believe that cooperative ideology is linked with certain political, religious or other convictions” (Nilsson 1996:639). For Nilsson (1996), cooperation (the most fundamental cooperative value) is not a socialist phenomenon, nor a defining feature of a liberal organization, nor even a special or distinct form of capitalism; rather he regards all these contrasting ideologies as potentially present within cooperation. It follows that a cooperative ideology should never be an excuse for commercial failure.

The coding of themes related to cooperative principles is summarized in Table 3. In sum, cooperative principles are normative rules giving moral direction to cooperative organizational behaviors and rooted in shared values. Indeed, they can be derived from member’s values (individual or shared) and are enacted through organizational behaviors. On the one hand, cooperative principles can be seen as ends in themselves (Miranda 2017), while on the other hand, they can be understood as antecedents to organizational ends, like transaction cost reduction (Nilsson 1996).

3.2 Defining concern for community

The Concern for Community principle is expressed in various ways. Broad speaking, it is associated with either the achievement of social goals or behavior oriented towards community engagement. With regard to social goals, the quintessence of a cooperative is mutuality, whether internal or external (Gios and Santuari 2002). External mutuality, the quest to satisfy the goals of external stakeholders, relates to an increase in collective welfare. It follows that, by fulfilling Concern for Community, cooperatives aim to improve social welfare. Demonstrably achieving such positive contributions is important because many countries provide special legal and tax treatments for cooperatives (ibid.).

The behavioral goals of Concern for Community can be determined by contextual, ideological, and social factors (Vo, 2016). Contextual factors examine whether the cooperative is acting out of necessity and/or self-interest. Ideological factors explore whether it is following cooperative values as an intrinsic concern, reinforced by other causal factors (e.g., seeking national economic development). Sociological analysis explores whether members seek to strengthen ties within a homogeneous community (social bonding) and/or a heterogeneous community (social bridging).

According to Battaglia et al. (2015), the primary motivations to engage in social activities are strategic or economic – meeting the needs of powerful stakeholders like customers or members. The secondary driver is responsible behavior, serving to deliver impacts for stakeholder organizations. This is consistent with the proposition of Cançado et al. (2014), that the Concern for Community principle is grounded on the basis of gift, namely that actions are made because reciprocity is the norm and there is no self-interest a priori. The third motivation is institutional pressure, with the goal of maintaining or improving the cooperative’s reputation. Agreeing with Vo (2016), Battaglia et al. (2015) highlight contextual factors (economic and strategic pressure), ideological factors (responsible behavior) and social factors (instrumental social accounting initiatives not motivated by gift).

Vo (2016) studies three Costa Rican farmer cooperatives and finds that social effort evolved over time, from initially having an economic motivation, to moving towards the provision of social goods, and finally to centering on political mobilization of the community. The kind of social and political outcomes a cooperative manifest appears to be a matter of organizational maturity. At a basic level, this is about solving market failure by providing commercial services (e.g. gas stations and grocery stores), fair pricing and job creation. Here, cooperatives are a guardian of fair market prices. At a higher level, it involves education and training, both in agricultural practices and formal education, for example on the provision of goods (e.g. housing) or a forum to discuss environmental concerns. At an even higher level, Concern for Community is enacted to provide infrastructure (e.g. roads) for the community and as a means to political engagement (Vo, 2016).

Oczkowski et al’s (2013) qualitative research exploring Australian cooperatives finds that Concern for Community is mainly manifest in local community activity, such as sport and its sponsorship, welfare, schools, and community groups. This result is comparable to the second and third levels of community engagement identified by Vo (2016), that is, social and political. In contrast, Nilsson (1996) proposes that Concern for Community is expressed through the improvement of economic conditions, such as the response to market failure, which can be linked to the first level offered by Vo (2016).

Across the papers, there is dispute on what community means. While some cooperatives consider themselves to be part of broader communities, others consider just their members as their community (Oczkowski et al. 2013). Nonetheless, the ICA (2016) identifies community as both the immediate community (not just the members) and the global community. In line with this broader vision, Concern for Community should be enacted through actions that address social, economic, and environmental domains (ibid.). In this sense, we locate a gap in understanding between normative ICA assumptions and the academic literature.

Academic theorization could benefit if basic nominal categories are identified to inform a typology for the Concern for Community principle. Even though we consider that Vo (2016) has established the foundation, more studies are needed to clarify whether his typology of contextual, ideological, and social factors is a fair representation of the diverse cooperative realities. Also, it is yet to be clarified whether cooperatives evolve to fulfill the levels of the typology, or whether the categories are not levels at all, but simply distinct idiosyncratic approaches of each cooperative. The coding of themes related to “defining concern for community” is summarized in Table 4.

3.3 Adoption of concern for community

There are 5 empirical papers (Alves et al. 2019; Badiru et al. 2016; Martínez-Carrasco Pleite 2017; Corrigan & Rixon, 2017; Bustamante Salazar 2019) focusing on the uptake and application of the Concern for Community principle, either sitting solely or among other cooperative principles. The main aim of this body of research is gauging the consciously perceived relevance of cooperative principles (Oczkowski et al. 2013).

With a case study approach spotlighting five Brazilian mining cooperatives, Alves et al. (2019:59) conclude that most principles are not being applied, and Concern for Community, defined as “development policies toward sustainable development envisaging the social welfare of local populations”, is not practiced because cooperatives are not aware of this principle. Badiru et al. (2016), with a survey of 126 Nigerian farmer cooperatives, resonate with this and find that, on average, cooperatives adhere to a mere half of the cooperative principles because of a lack of awareness of them.

With empirical evidence from 22 Spanish agricultural cooperatives, Guerra and Quesada-Rubio (2014) find that the majority of members perceived that the principles are not put into practice, because of credibility, managerial and ideological problems. In the same vein, Egia and Etxeberria (2019) find that changes in collective thinking from a new generation of digitally engaged workers, with their expectations and preferences, have given rise to an evolution among cooperatives. Cooperative values are being forgotten and education is suggested as the main solution (ibid.).

A mixed picture emerges from a survey of 321 Spanish citizens by Martínez-Carrasco Pleite and Eid (2017), which reveals that when compared to other organizations cooperatives are regarded as more ethical and having greater concern for society, but worse in terms of profitability, quality, leadership, innovation, and employee treatment. Nevertheless, when compared to other organizational forms, especially large investor-owned firms but also political parties, confidence in cooperatives is the second highest, behind small and medium sized enterprises (Martínez-Carrasco Pleite and Eid 2017). The results are even more revealing when we learn that over 10% of respondents are cooperative members and more than 50% have family or friends as members (ibid.). Taken together, these results depict robust citizens’ trust in cooperative organizations, but with a caveat around their technical ability.

It becomes apparent that most studies with an insider perspective point to an absence of principle compliance, while others point to high levels of confidence from external stakeholders. This gap is yet to be fully understood, remaining hitherto unaddressed in the literature. Researchers could perhaps compare the image of cooperatives across different stakeholder points of view, using the standardized definition from the key conceptual constructs, to disregard any influence from semantic variation. While it could be conceded that certain studies do articulate a binary vision in conceiving Concern for Community practice, it is very unlikely that an organization would have absolute zero application of the principle, even if it is self-interested. Clearly, the literature could benefit more from nuanced measurement of Concern for Community than from a binary view. Presenting a more granular concept for Concern for Community and comparing responses to it would indeed be a promising route.

Focused on aspects of management, Corrigan and Rixon (2017) learn that electricity cooperatives’ key performance indicators (KPIs) are not linked to the cooperative principles. In the same vein, studying three insurance cooperative cases in developed countries, Beaubien and Rixon (2014) find that cooperative principles influence organizational culture, but they fail to permeate strategic planning and are not reflected in KPIs. They propose that their absence in strategic planning and reporting indicates a deviation from cooperative identity and a sole focus on financial goals (Corrigan & Rixon, 2017). Drawing a similar conclusion, Battaglia et al. (2015) reveal that implementing sustainability accounting tools can drive a participatory social plan. Notwithstanding this, they also show that middle managers remain unconvinced that investing in this type of control is useful. The managers even associate sustainability accounting tools with hostility and systemic attempts to control staff. Thus, there is evidence that Concern for Community action is, at some level, avoided by managers.

Nevertheless, it remains entrenched and systematically applied across certain forms. Studying three Colombian worker cooperatives, Bustamante Salazar (2019) proposed that solidarity capability, informed by Concern for Community, develops through a process starting with information (data about the cooperative and surroundings), followed by formation (development of abilities), and finally by participation (member influence on cooperative management). Capabilities that influence the whole organization can be developed when a cooperative seeks to foster actions that expressly concern the community.

The literature exploring the influence of management on Concern for Community is underdeveloped. Apart from research that demonstrates managerial resistance to the adoption of methods and controls that address the community, little else is known. The implicit assumption is that if Concern for Community is embraced by individual members it will be embraced at the level of the organization, which might not be the case. To broaden this limited thread, future studies might usefully explore how organizational structure, internal relationships, and resources relate to the implementation of Concern for Community. Finally, when there is conflict between Concern for Community and other principles, the question arises as to its optimal resolution. For example, there may be a dilemma over distributing surplus and whether democratic decisions override greater social concerns, or vice versa. The answers to how cooperatives cope with these questions remain vague in the literature. The coding of themes related to the adoption of concern for community is summarized in Table 5.

3.4 Antecedents of concern for community

Bustamante Salazar (2019) identifies three clear levels of driver in the implementation of cooperative principles: (1) personal conditions – education level, family, and health status of members; (2) organizational conditions – work methods and relationships with managers; (3) external conditions – norms and rules in place. We employ this classification as a framework for presenting more other relevant findings.

Oczkowski et al. (2013), also identify three such levels in their qualitative research on Australian cooperatives. On the personal level, they show cooperatives’ adherence to the ICA principles is guided by the passion and motivation of the board, because board members are ultimately responsible for applying the principles. In a study using citizens as the level of analysis, Tak (2017) finds cooperative members have a 69% chance of helping in the community. Participating in weekly member meetings increases the chance of community engagement by 480%. He also found that having higher income, having children, being older, being married, and being unemployed all increase the chances of being engaged in community affairs. However, gender and level of education does not predict one’s community engagement. Novkovic and Power (2005) propose that member willingness to retain cooperative values are paramount for principle-based management. That is, member responsibility is central to organizational discipline, otherwise the cooperative will be prone to coercion to offer particular benefits and suboptimal pricing (Decker 2010).

Organizationally, the presence of strategic planning as well as education and training are drivers of the principles adoption, because members need to understand the significance of the principles and, as a cooperative develops, it must stay loyal to its founding motivations (Oczkowski et al. 2013). Other studies also throw light on the organizational conditions for adherence to Concern for Community. For example, Heras-Saizarbitoria (2014) interviewed 27 members of a Spanish worker cooperative, demonstrating that the youngest and most recent members tend to participate less in key decision-making. According to Battaglia et al. (2015), social performance is improved if an organization implements sustainability accounting (through formal reporting). Finally, Novkovic and Power (2005:70) suggest that cooperative values and principles should be nurtured within organizations through catalyst mechanisms – “mechanisms in their daily business that will automatically lead to that goal”.

External conditions, social orientation, and social goals are not enough to drive social responsibility because it remains important to understand contextual industry dynamics (Decker 2010). For example, rural cooperatives tend to adhere to cooperative principles more than urban ones do, and the larger the cooperative, the harder it is to feel part of a community (Oczkowski et al. 2013).

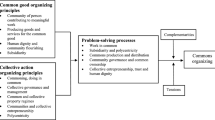

For greater clarity, some studies present Concern for Community embedded within more general principles (Fig. 2), while others present the specific antecedents (Fig. 3). In both figures, there is a clear preference to explain the phenomena from an individual perspective; all the roots for Concern for Community and almost half of the antecedents of all the principles (including Concern for Community) are individual-based. Thus, the literature has not adequately identified organizational factors leading to Concern for Community. Given that the achievement of the cooperative principles is compromised in the absence of factors like financial resourcing, training, and reporting, we can infer Concern for Community would be no different.

There are several theories pointing to the importance of contextual factors that influence organizations. For example, Bustamante Salazar (2019) suggests that norms and rules affect behaviors exhibiting the principles. This argument is consistent with institutional theory, but for Concern for Community, we still lack clarity on what kind of norms and rules could benefit or hinder its attainment. Although we know that rural cooperatives tend to practice the principles more than their urban counterparts, we have little understanding of why.

Future research could also perhaps demarcate any distinctions in levels of Concern for Community between cooperatives in different industries (Decker 2010), and among different types of cooperatives (such as product versus service, or worker versus producer). Elucidating this would help generate recommendations to practitioners and contribute toward the management literature on cooperatives.

3.5 Outcomes of concern for community

As with the antecedents, the outcomes of Concern for Community considered in the literature are not disentangled from those of other principles. Consistent with the ICA (2016), Beaubien and Rixon (2014) and Guerra and Quesada-Rubio (2014) propose that the implementation of the principles is what differentiates cooperatives from other types of legal organization. It seems evident that principle adoption is a strategic asset for cooperatives. According to Oczkowski et al. (2013), adopting them leads to economies of scale, non-monetary goals (such as empowering the community), sustainability, and positive personal impact for members. Principles adherence, however, may also result in surplus retention, deviation from business best practices, slow decision-making, difficulties in hiring directors, and limited ability to raise capital (ibid.).

Guzmán, Santos, and Barroso (2020) surveyed 155 working cooperatives in Spain to find that practicing cooperative principles not only increases employment and wellbeing, but also performance and sales growth. They also found that entrepreneurial orientation is a mediator in the relationship between the principles practice and performance because, through seeking answers to social needs, cooperatives can find new market opportunities. Further, because cooperatives are more concerned with the wellbeing of members and less influenced by the pressures of centralization, they are strategically well positioned to form virtual enterprises (Depaoli and Za 2016).

Principles oriented cooperatives tend not to exploit employees and they pay higher wages, which suggests that, ceteris paribus, cooperative employees apply greater effort in work than those in investor-owned firms (Altman 2015). That is, cooperatives enjoy social capital, which facilitates coordinated actions and increases organizational efficiency (Akahoshi and Binotto 2016). In economic crises, cooperative employees tend to accept lower wages without reducing their effort (Altman 2015). Therefore, in theory, principles-driven cooperatives should have lower transaction costs than their counterparts.

Figure 4 displays the positive outcomes of adopting cooperative principles, in considering Concern for Community. We can broadly identify two outcome groupings: economic and social. Economic outcomes accrue in the form of productivity, economies derived from lower transaction costs, and employment. Social outcomes arise from developing solidarity and social capital, leading to sustainable business and cooperatives being closer to their core values.

Figure 5 outlines the undesirable consequences the literature reports. These are mainly managerial problems, such as slow decision-making, deviation from best practices, and recruiting talent. It can be inferred, therefore, that managers may struggle to apply cooperative principles and managerial tools simultaneously. In line with Leca et al. (2014), we speculate that adverse outcomes may be linked to scarce knowledge and managerial training on cooperatives.

Notwithstanding the relevance of the above walk through the impacts of all the principles, there is a stream of the literature focused on outcomes solely from the Concern for Community principle. For example, Figueiredo and Franco (2018) show that members are more interested in participating in decisions and promoting well-being in their communities than in financial surpluses. Thus, we can infer that the more Concern for Community a cooperative has, the more satisfied the members will be.

In a critical study, Azurmendi et al. (2013) point to, and unpack, the incidence of degeneration in some cooperatives. They report that degeneration occurs when cooperative workers lose their labor rights, when cooperatives change their initial goals to pursue maximization, or when the cooperative is controlled by a small number of managers. They argue that cooperatives can regenerate through using multidisciplinary self-managed teams, focused on certain aspects of the market, and also through the principle of solidarity and self-management. Perhaps cooperatives developing more solidary activity (such as Concern for Community behaviors) can bring about regeneration.

Linking this specific principle with economic outcomes, Liang et al. (2015) and Bontis et al. (2018) present a positive relationship between Concern for Community and financial performance (Guzmán et al. 2020). Agahi and Karami (2013) posit that this link is explained by the social capital derived from Concern for Community and its consequences in production success.

Consistent with the observation that bonding social capital leads to over-embeddedness hindering innovation (Uzzi, 1997), Leca et al. (2014) find that the effort made by cooperatives to nurture close relations with the community may prevent the diffusion of the cooperative model. Even though corporate image is often regarded as its main market outcome, there is evidence that social actions do not improve all the dimensions of reputation (Figueiredo and Franco 2018; Prasad and Holzinger 2013).

Summarized in Fig. 6, this literature review shows that practicing Concern for Community can enhance member satisfaction with cooperatives, thereby creating social capital. As a key element of production success, social capital helps to lower transaction and agency costs, especially in monitoring. With better production, financial results are achieved. Nonetheless, excessive attention to communities could be detrimental to cooperative model diffusion because of the time spent in these activities, and thus in opportunity costs.

We notice the absence of studies linking Concern for Community with community results: social outcomes or environmental outcomes. Even ICA reports are economically driven, asserting the benefits of the 7th principle to include “the acquisition of new members, increased turnover, and higher surpluses that reinforce a co-operative’s economic success” (ICA 2016:96). The sparse literature on Concern for Community is fundamentally focused on explaining economic outcomes. Nonetheless, Concern for Community behaviors can indeed aid the regeneration of cooperatives, reinforcing their links with core cooperative values.

Comparing the literature threads focused on Concern for Community with those focused on principles in general, some inconsistencies become apparent. A number of related questions arise, for example whether Concern for Community behavior negatively affects the ability to hire good managers, or to raise capital. Most scholarly works would label these as the undesirable outcomes of democratic governance, but perhaps we could challenge the perception that investors and managers are not willing to do business with cooperatives because of their socio-environmental principles. If this is a valid line of questioning, obvious further dilemmas appear, such as the boundary conditions: it might be worth considering under what conditions capable managers might wish to be part of cooperatives. All these questions have yet to be addressed in the research literature.

Moreover, we can ask whether Concern for Community is the root of job creation, job satisfaction, and a greater focus on sustainability. Even though this is a normative assertion of the ICA (2016), more research is needed to explain both the outcomes of Concern for Community and how these may be assured. Extant research only focuses on social capital as the outcome from which every other outcome is derived. Researchers and practitioners would benefit from a more granular explanation.

Therefore, future research could consider focusing on delineating the study of Concern for Community from the other principles, and perhaps on describing and measuring how Concern for Community affects socio-environmental outcomes. Future research could also usefully explore the unmet objectives of the 7th principle such as publicizing the challenges of sustainable development and setting goals for it, as indicated by the ICA (2016).

3.6 Discussion: concern for community and corporate social responsibility (CSR)

The 2016 ICA Guidance Notes on principles mentions social responsibility exclusively in relation to the 7th principle. On this basis alone, we may conclude that CSR is entirely within the scope of the 7th principle. The ICA Guidance Notes does not provide or recommend a method of measuring the 7th principle, but notes: “Following best practice of corporate social responsibility, many co-operatives now provide social responsibility reports to their members” (ICA 2016:88). Responding to this omission, Molina et al. (2018) have pioneered a sustainability report, which they call a social responsibility web system. They present a table of social balance models, which include metrics to measure CSR, but notably these are mapped against the cooperative principles. Therefore, measuring the cooperative principles is equivalent to measuring CSR.

In contrast, Vo (2016) and Cançado et al. (2014) hold that commitment to the ICA values and principles differentiates cooperative community engagement from CSR. The latter is motivated by the desire to: (1) “serve their long-term self-interest”, (2) “improve their public image”, and (3) “increase viability of business, among other reasons” (Vo, 2016:72). Therefore, the motivation underpinning the action differs. We analyze the arguments of both papers below.

First, Vo (2016) defines CSR following McWilliams and Siegel (2001:117) as “actions that appear to further some social good, beyond the interests of the firm and that which is required by law”. If, within the definition used, CSR is beyond the interests of the firm, it is logically as altruistic as Concern for Community and could not be regarded as long-term self-interest, hence being virtually the same construct.

For a similar argument, Polo and Vázquez (2014:9) conceptualize social responsibility as “the voluntary integration, by enterprises, of social and environmental concerns in their commercial operations and their relationship with partners”. They posit that cooperative organizations are not economic organizations with social sensitivity, but organizations that place people first and develop economic activities from this paradigm. To them, each principle would induce some aspect of social responsibility, with the Concern for Community principle being the root of environmental concern, impact on surrounding communities, and responsibility towards workers. Self-interest and altruistic motivations are co-present, but the difference is found in the sequencing; while in investor-owned firms (IOF) the primary orientation is economic and CSR a secondary consideration, the core orientation in cooperatives is social, with economic matters regarded merely as instrument. Nonetheless, it is clear that some cooperatives primarily seek economic goals, which is consistent with the lowest level of Concern for Community (Vo, 2016).

Pointedly, Cançado et al. (2014) argue that the Concern for Community principle inherently contains the notions of CSR, but it manifests in different ways. They delineate these as four dimensions: (1) the reasoning of action; (2) the method of decision-making; (3) territoriality; (4) participation in the implementation. We discuss these below.

For the first dimension, Cançado et al. (2014) assert that the true motivation of CSR is marketing or tax planning, arguing that altruism is an impossibility for IOF and implying that any efforts made by cooperatives should be regarded as altruistic, for which we have not found support in the literature. We contend that both motivations (altruistic and self-interested) can be in place when an organization presents Concern for Community. With the logic that even altruistically motivated actions should not jeopardize the economic sustainability of organizations, an economic calculation should then be made about the positive and negative financial outcomes, beyond the social outcomes. If this logic is correct, altruistic, and self-interested Concern for Community actions would occur simultaneously.

The second dimension, the method of decision-making, is a key distinction between cooperatives and IOFs. The assumption is that democratic decisions (involving members and stakeholder groups) would be more assertive in seeking to benefit the community than CSR. In fact, it could be contended that this difference is most clear in information gathering and processing: in cooperatives, more stakeholder information is usually used to make decisions. However, an IOF should be able to mimic this by garnering information among its stakeholders.

Explaining the third dimension, Cançado et al. (2014) suggest that Concern for Community is conducted in the same territory that the cooperative operates within, although this is not a rule (for example, considering Fairtrade in international commodities). In the same vein, Decker (2010) argues that locally run businesses are less likely to exploit or pollute their communities. Cançado et al. (2014:202) qualifies this understanding when arguing that “there is no guarantee that the actions of Social Responsibility will continue in these territories”. There is certainly no guarantee that every action on local communities made by cooperatives will endure. The wider literature expands the geographical scope of the 7th principle when highlighting the fact that global cooperative initiatives are designed to connect distant local communities; for example, connecting producers and consumers through fairtrade certifications (Meemken et al. 2019). Nevertheless, the literature demonstrates that most cooperative actions addressing the 7th principle are geographically parochial, because the concept of community has tended to be restricted to members’ local communities and those in near proximity.

Finally, Cançado et al. (2014) propose that the “broad” benefits of not-for-profit actions are valued by cooperative members for their contribution to reciprocating social relations within the logic of a gift economy. There are symbiotic relationships among members, community, and cooperative and the actions of each affect the others. The obligation of giving without an economic return is denied in IOFs by their “narrow” mandate to maximize value for shareholders.

After analyzing each of these positions, we conclude there are more aspects in common than there are differentiating CSR from Concern for Community. Yet, if any differences should be highlighted, they are those concerned with where actions are conducted and to whom they are addressed, rather than with the motivations of the actions.

Some authors compare CSR with the cooperative principles generally, rather than Concern for Community alone. For Bustamante Salazar (2019), because of the very existence of the principles, socially responsible actions are more readily enacted in cooperative organizations; yet this is done through actively employing the principles and not by their mere existence. Therefore, the enactment of the principles could be theorized as CSR actions.

In the same vein, the ICA (2006) defines seven dimensions of social responsibility for cooperatives in The Global 300 project (Decker 2010). The dimensions are people, products, principles, environment, community, democracy, and development. By comparing cooperative principles with CSR principles, Decker (2010:279) states that “democratic member control, member economic participation, Concern for Community, and sustainable development resonate closely with CSR principles”. Thus, the concept of CSR appears to be wider than Concern for Community, but it could also be within the set of cooperative principles. Further, Decker (2010) finds that CSR is mostly related to the Concern for Community issues of morality and social justice. The fundamental question to address in discussions of justice is the definition of the human being, which leads to questions of who defines and determines the goods that can be enjoyed by human beings, and how those goods are distributed fairly (Sandel 1982). This is why the good requires metaphysical grounding, which is also why the most legitimate way to agree on what is good is through political democratic cooperation. Afterall, it is rare that human beings agree on the metaphysical grounds for the definition of the nature of the good and how it should be realized and distributed.

We would also argue that multistakeholder cooperatives are the most effective cooperative organizational form that brings stakeholders and their legitimate moral concerns within the organization to inform decisions. This democratic potential in the multistakeholder cooperative form, provides a vital difference to IOFs and single user dominated member cooperatives. By bringing multiple stakeholders into membership, the enactment of the first six ICA principles has a greater potential to influence the enactment of the 7th principle (Imaz et al., 2023). In this sense, we suggest a call for future research into multistakeholder cooperatives and how this organizational form has the structural design that can achieve Concern for Community or CSR in practice.

We conclude that there is an open conversation in the literature about the connections between the cooperative principles, especially Concern for Community, and CSR. The first consequence is that authors writing about Concern for Community should seek greater clarity on how they approach these constructs. Further, as the ICA Guidance is relatively recent, there exist research opportunities to understand whether and to what extent organizations may be aligning with its normative propositions. Second, recent research suggests that there are gaps in our understanding of social entrepreneurship more generally, which could equally apply to research into the cooperative Concern for Community (Klarin and Suseno 2023). Most notably, the connection between the micro and macro level needs to be better understood in relation to the enactment of Concern for Community. Individual agency (e.g. leadership) is overlooked in the discussions of universal frameworks and organizational enactment of principles, despite a rich tradition of historical research highlighting the influence of pioneers that worked towards Concern for Community when it was an implicit rather than an explicit goal (for example, see Cohen 2020). It is noteworthy that the ICA (2016) Guidance acknowledges the contributions of numerous individuals. Third, if the principles are to be maximally optimized (Miranda 2017), then more research needs to focus on issues of downscaling (Turner and Wills 2022); that is, the way in which global frameworks are locally institutionalized. Fourth, the recursive framing of Concern for Community by the ICA will need to engage with strong definitions of sustainability (e.g. Raworth 2017) and proposals for de-growth that highlight the limits of planetary boundaries and the dependency of economic and social value creation on environmental systems (Cunico et al. 2022). The ICA Guidance reflects the reasoning of the Brundtland Report and influence of the Rio process (see Purvis, 2019), when suggesting that the: “Economic viability of co-operatives is key to economic, environmental and social sustainability” (ICA 2016:92). Research is emerging that explores different approaches to scaling and downscaling in locally rooted cooperatives, which are commensurate with the growing awareness of environmental limits and offer an alternative role for economic development within Concern for Community (Chiengkul 2018; Colombo et al. 2023). Finally, Cooperatives are hybrid organizations that serve two missions - a social mission and a commercial mission. These missions can be misaligned, and “tension can form between them as the commercial and social value creating activities compete for the limited resources available” (Armstrong and Saartjie Grobbelaa 2023:787). Therefore, the underlying motivations of pro-social acts could usefully be researched; instead of drawing a line between altruistic and self-interested actions, researchers could seek to explain which factors favor whom and the range of outcomes accrued from various actions. This opportunity could be explored through the theoretical lens of duality, multiple logics, and paradox theory, which provide a framework to explore how the presence of contradictory and interrelated elements are negotiated (Novkovic et al. 2022).

Our proposed framework (Fig. 7) serves as a guide to understanding the 7th cooperative principle. Based on our findings the principle is essential to the cooperative business model, but currently it is being overlooked by cooperatives even though they understand that it is a vital part of the cooperative identity and has the potential to enhance social, economic, and environmental performance. As Krome & Pidun (2022) suggest, divergence from traditional organizational models should be examined through different lenses, and CSR should be the link to the 7th principle full adoption and differentiation. In this sense, exploring this possible link is a future research direction that we propose.

4 Conclusion

The objective of this article was to assess the most relevant literature streams on the Concern for Community principle, compare it to the normative guidelines from the ICA, and attempt to draw future directions for its research. We find specific streams of studies on Concern for Community to be underdeveloped, with most merely mentioning it in the context of all the cooperative principles. Research with a fine-grained view of Concern for Community being so scarce, therefore, suggests an opportunity for future research.

We also find that the ICA’s view of Concern for Community is more widely encompassing than the extant literatures generally. In the ICA (2016) Guidance, the concept of CSR is included within the 7th principle by making the explicit link to the value of social responsibility. The literature has a more nuanced view, differentiating CSR and Concern for Community by motivation, locus, timespan, and target public.

4.1 Future Research

To develop the field of research into Concern for Community, a number of bridges need to be constructed to enable more nuanced theoretical reflection and empirical investigation. First, in relation to praxis, more research is needed into how principles are translated into practice. As the ICA Guidance is relatively new (as of 2016), future research will need to explore how their normative recommendations are being received and enacted by cooperatives. In this endeavor, researchers cannot assume that consistency models (cognitive, behavioral or positivist) will offer explanations for how the principles or ideals influence practice, which means paying more attention to how decisions are made in the context of uncertainty, genuine dilemmas, and paradox (Hoffmann 2018). Exploration of Concern for Community will benefit from insights that stress “the communicative constitution of a paradox of conflictual, intermingled and dynamic extrinsic and intrinsic CSR motives” (Frerichs and Teichert 2023:253).

Second, in relation to sustainability, the ICA states that economic, social, and environmental dimensions are essential considerations to Concern for Community, but few existing studies explore their perceived interrelation, in terms of their equivalence or hierarchical prioritization, and how they are conceived influences practice. Paradox theories may help to explain how different conceived interrelationships between the three dimensions of sustainability may be co-present within cooperatives as they engage with Concern for Community principle.

Third, a bridge needs to be built to the social enterprise literature that explores social responsibility within the competitive environment (Yosun & Cetindamar, 2023), exploring how the cooperative principles influence competitive strategy and decision making (e.g., quality, price, differentiation, level of service).

Fourth, there are works presenting a dichotomy between the presence or absence of Concern for Community in cooperatives, but we urge more nuanced measures that could unpack its drivers and consequences. At this point, the literature regards individual characteristics (such as age, marital status, and family type) as the main antecedents of Concern for Community. Some studies have presented organizational factors (strategic planning or the presence of KPIs) as antecedents of principles adoption, but there is no specific reference to Concern for Community. Industry factors (Porter 1991) and institutional factors (North 1990; Lusch & Vargo 2014;) are major influences on organizations, but these have yet to be engaged with in the Concern for Community literature. In terms of measuring outcomes and impacts, research into Concern for Community is inclined toward economic perspectives. It remains unknown how Concern for Community affects the social and environmental indicators of their communities (both local and national).

4.2 Limitations

This article has several limitations. First, we did not explore the CSR literature to create a comparative inverse path, trying instead to route it to Concern for Community. Second, we did not present specific foundational theories (industry, organization, institutionalism), which could have helped in the development of the review. Third, the Scopus database could have been supplemented with additional databases to provide a more comprehensive and exhaustive search of the extant literature (Wanyama et al. 2022). Finally, given our design decisions, we chose to review papers referring to Concern for Community as part of a broad set of cooperative principles, which could potentially have steered some of the analysis.

Data availability

The authors confirm that all data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this manuscript. Furthermore, sources and data supporting the findings of this study were all publicly available at the time of submission.

References

Agahi H, Karami S (2013) A study of Factors Effecting Social Capital Management and its impact on success of production cooperatives. Middle East J Sci Res 3(8):4179–4188. https://doi.org/10.5829/idosi.mejsr.2013.15.6.11312

Akahoshi WB, Binotto E (2016) Cooperatives and social capital: the Copasul case, Mato Grosso do sul state. Manage Prod 23(1):104–117. https://doi.org/10.1590/0104-530X532-13

Altman M (2015) Cooperative organizations as an engine of equitable rural economic development. J Co-Op Organ Manage 3(1):14–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcom.2015.02.001

Alves W, Ferreira P, Araújo M (2019) Mining co-operatives: a model for establishing a network for sustainability. J Co-Op Organ Manage 7(1):51–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcom.2019.03.004

Anderson V, Elliott C, Callahan JL (2021) Power, powerlessness, and journal ranking lists: the marginalization of fields of practice. Acad Manage Learn Educ 20(1):89–107. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2019.0037

Armstrong RM, Saartjie Grobbelaa SS (2023) Sustainable business models for social enterprises in developing countries: a conceptual framework. Manage Rev Q 73(2):787–840. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-022-00260-1

Azurmendi B, Etxezarreta E, Morandeira J (2013) Regeneration of the Social economy enterprises. REVESCO Revista De Estudios Cooperativos 112:152–175. https://doi.org/10.5209/rev-REVE.2013.v112.43064

Badiru IO, Yusuf KF, Anozie O (2016) Adherence to Cooperative principles among Agricultural cooperatives in Oyo. J Agricultural Ext 20(1):142–152. https://doi.org/10.4314/jae.v20i1.12

Barney J (1991) Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J Manag 17(1):99–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/01492063910170010

Battaglia M, Bianchi L, Frey M, Passetti E (2015) Sustainability reporting and corporate identity: action research evidence in an Italian retailing cooperative. Bus Ethics: Eur Rev 24(1):52–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/beer.12067

Beaubien L, Rixon D (2014) Intentions, observations, and decisions: Metrics in insurance co-operatives. Adv Public Interest Acc 17:113–127. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1041-706020140000017004

Bontis N, Ciambotti M, Palazzi F, Sgro F (2018) Intellectual capital and financial performance in social cooperative enterprises. J Intellectual Capital 19(4):712–731. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIC-03-2017-0049

Brundtland GH (1987) Our common future—call for action. Environ Conserv 14(4):291–294. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0376892900016805

Bustamante Salazar MA (2019) Socially responsible human management in Colombian associated work cooperatives. CIRIEC-ESPANA REVISTA DE ECONOMIA PUBLICA SOCIAL Y COOPERATIVA 95:217–255

Caceres J, Lowe JC (2000) Cooperation and globalization: mutation or confrontation. J Rural Cooperation 28(2):101–119. https://doi.org/10.22004/ag.econ.60903

Cançado AC, de Fátima Arruda Souza M, Rigo AS, Silva Júnior JT (2014) Principle of concern for community: beyond social responsibility in cooperatives. Boletín De La Asociación Int De Derecho Cooperativo = Int Association Coop Law J 48:191–204. https://doi.org/10.18543/baidc-48-2014pp191-204

Chiengkul P (2018) The Degrowth Movement: Alternative Economic practices and relevance to developing countries. Alternatives 43(2):81–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/0304375418811763

Clark WR, Clark LA, Williams RI, Raffo DM (2023) Using a systematic literature review to clarify ambiguous construct definitions: identifying a leader credibility definitional model. Manage Rev Q. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-023-00378-w

Cohen R (2020) Margaret Llewelyn Davies: with women for a New World. Merlin

Colombo LA, Bailey AR, Gomes MV (2023) Scaling in a post-growth era: learning from Social Agricultural cooperatives. Organization 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/13505084221147480

Corrigan LT, Rixon D (2017) A dramaturgical accounting of cooperative performance indicators. Qualitative Res Acc Manage 14(1):60–80. https://doi.org/10.1108/QRAM-08-2016-0060

Cunico G, Deuten S, Huang IC (2022) Understanding the organisational dynamics and ethos of local degrowth cooperatives. Clim Action 1(11). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44168-022-00010-9

Decker OS (2010) Exploring the corporate social responsibility agenda of British credit unions: a case study approach. Int J Bank Acc Finance 2(3):275–294. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJBAAF.2010.033501

Depaoli P, Za S (2016) The Possible Evolution of the Co-operative Form in a Digitized World: An Effective Contribution to the Shared Governance of Digitization? In: Borangiu, T., Dragoicea, M., Nóvoa, H. (eds). Exploring Services Science. IESS 2016. Lecture Notes in Business Information Processing, vol 247. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-32689-4_16

Egia EG, Etxeberria GM (2019) Training of cooperative values as a decisive element in new jobs to be created by 21st century cooperatives. Boletín De La Asociación Int De Derecho Cooperativo 54:97–114. https://doi.org/10.18543/baidc-54-2019pp97-114

Figueiredo V, Franco M (2018) Factors influencing cooperator satisfaction: a study applied to wine cooperatives in Portugal. J Clean Prod 191:15–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.04.177

Frerichs IM, Teichert T (2023) Research streams in corporate social responsibility literature: a bibliometric analysis. Manage Rev Q 73(1):231–261. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-021-00237-6

Gios G, Santuari A (2002) Agricultural cooperatives in the County of Trento (Italy): economic, organizational and legal perspectives. J Rural Cooperation 30(1):3–12. https://doi.org/10.22004/ag.econ.60951

Grice P (1975) Logic and conversation. In: Cole P, Morgan J (eds) Speech acts. Academic, New York, pp 41–58

Guerra IR, Quesada-Rubio JM (2014) The cooperative principles as intangible capital before the challenges of cooperativism. Intangible Capital 10(5):897–921. https://doi.org/10.3926/ic.406

Guzmán C, Santos FJ, Barroso O, M (2020) Analyzing the links between cooperative principles, entrepreneurial orientation and performance. Small Bus Econ 55(4):1075–1089. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-019-00174-5

Liang Q, Huang Z, Lu H, Wang X (2015) Social capital, member participation, and cooperative performance: evidence from China’s Zhejiang. Int Food and Agribus Manage Rev, 18(1), 49–77. https://doi.org/10.22004/ag.econ.197768

Heras-Saizarbitoria I (2014) The ties that bind? Exploring the basic principles of worker-owned organizations in practice. Organization 21(5):645–665. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508414537623

Hoffmann J (2018) Talking into (non)existence: denying or constituting paradoxes of corporate social responsibility. Hum Relat 71(5):668–691. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726717721306

ICA (2016) Guidance Notes to the Co-operative Principles. https://www.ica.coop/en/media/library/research-and-reviews/guidance-notes-cooperative-principles

ICA (2023) Facts and Figures. https://ica.coop/en/cooperatives/facts-and-figures#:~:text=More than 12%25 of humanity,World Cooperative Monitor (2023). Accessed 29 December 2023

ICA (2024) Cooperative identity, values & principles https://ica.coop/en/cooperatives/cooperative-identity#:~:text=Cooperatives are based on the,responsibility%20and%20caring%20for%20others. Accessed 22 February 2024

Imaz O, Freundlich F, Kanpandegi A (2023) The governance of multistakeholder cooperatives in Mondragon: the evolving relationship among purpose, structure and process. In: Humanistic governance in democratic organizations: the cooperative difference. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp 285–330.

Johnson MP, Rötzel TS, Frank B (2023) Beyond conventional corporate responses to climate change towards deep decarbonization: a systematic literature review. Manage Rev Q 73:921–954. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-023-00318-8

Klarin A, Suseno Y (2023) An integrative literature review of social entrepreneurship research: mapping the literature and future research directions. Bus Soc 62(3):565–611. https://doi.org/10.1177/00076503221101611

Krome MJ, Pidun U (2023) Conceptualization of research themes and directions in business ecosystem strategies: a systematic literature review. Manage Rev Q 73:873–920. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-022-00306-4

Leca B, Gond JP, Barin Cruz L (2014) Building ‘Critical performativity engines’ for deprived communities: the construction of popular cooperative incubators in Brazil. Organization 21(5):683–712. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508414534647

Martínez-Carrasco Pleite F, Eid M (2017) The level of knowledge and social reputation of cooperative enterprises. CIRIEC-ESPANA REVISTA DE ECONOMIA PUBLICA SOCIAL Y COOPERATIVA 91:5–29

Mcwilliams A, Siegel D (2001) Corporate social responsibility: a theory of the firm perspective. Acad Manage Rev 26(1):117–127. https://doi.org/10.2307/259398

Meemken EM, Sellare J, Kouame CN, Qaim M (2019) Effects of Fairtrade on the livelihoods of poor rural workers. Nat Sustain 2(7):635–642. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-019-0311-5

Miranda JE (2014) From the propedeutics of cooperative principles to intercooperation as a pillar of cooperativism. Boletín De La Asociación Int De Derecho Cooperativo 48:149–163. https://doi.org/10.18543/baidc-48-2014pp149-163

Miranda JE (2017) From voluntary adherence to half-open doors: arbitrariness in compliance with a cooperative principle. Boletín De La Asociación Int De Derecho Cooperativo = Int Association Coop Law J 51:63–77

Molina EC, Poveda MP, Córdova JD, Nuela D, Meza EZ, Tobar C (2018) Social Responsibility Web System as a Management and Dissemination Tool for Cooperative Principles. International Conference on eDemocracy & eGovernment (ICEDEG), Ambato, Ecuador, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICEDEG.2018.8372313

Nelson T, Nelson D, Huybrechts B, Dufays F, O’Shea N, Trasciani G (2016) Emergent identity formation and the co-operative: theory building in relation to alternative organizational forms. Entrepreneurial Identity Identity Work 28(3–4):286–309. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315193069-6

Nilsson J (1996) The nature of cooperative values and principles: transaction cost theoretical explanations. Annals Public Coop Economic 67(4):633–653. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8292.1996.tb01411.x

Nonaka I, Takeuchi H (1995) The knowledge-creating company: how Japanese companies create the dynamics of innovation. Oxford University Press, Oxford

North DC (1990) Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Novkovic S, Power N (2005) Agricultural and rural cooperative viability: a management strategy based on cooperative principles and values. J Rural Cooperation 33(1):67–78. https://doi.org/10.22004/ag.econ.59695

Novkovic S, Puusa A, Miner K (2022) Co-operative identity and the dual nature: from paradox to complementaries. J Co-Op Organ Manage 10(1):100162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcom.2021.100162

Oczkowski E, Krivokapic-Skoko B, Plummber K (2013) The meaning, importance and practice of the co-operative principles: qualitative evidence from the Australian co-operative sector. J Co-Op Organ Manage 1(2):54–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcom.2013.10.006

Polo FC, Vázquez DG (2014) La revelación social en sociedades cooperativas: una visión comparativa de las herramientas más utilizadas en la actualidad. REVESCO: Revista De Estudios cooperativos, n. 114, p. 7–34, https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=4679750

Porter ME (1991) Towards a dynamic theory of strategy. Strateg Manag J 12:95–117

Prasad A, Holzinger I (2013) Seeing through smoke and mirrors: a critical analysis of marketing CSR. J Bus Res 66(10):1915–1921. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.02.013

Qamar F, Afshan G, Rana SA (2023) Sustainable HRM and well-being: systematic review and future research agenda. Manage Rev Q. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-023-00360-6

Raworth K (2017) Doughnut Economics: seven ways to think like a 21st-Century economist. Random House

Sandel MJ (1982) Liberalism and the limits of Justice. Cambridge University Press

Santos C, Coelho A, Marques A (2023) A systematic literature review on greenwashing and its relationship to stakeholders: state of art and future research agenda. Manage Rev Q. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-023-00337-5

Tak S (2017) Cooperative membership and community engagement: findings from a latin American survey. Sociol Forum 32(3):566–586. https://doi.org/10.1111/socf.12349

Turner RA, Wills J (2022) Downscaling doughnut economics for sustainability governance. Curr Opin Environ Sustain 56:101180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2022.101180

Uzzi B (1997) Social structure and competition in interfirm networks: the paradox of embeddedness. Administrative Sci Q 42(1):37–69. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393808

Vargo SL, Lusch RF (2014) Service-dominant logic: what it is, what it is not, what it might be. In: Lusch RF, Vargo SL (eds) The service-dominant logic of marketing. Routledge, New York, pp 61–74

Vern P, Panghal A, Mor RS, Kamble SS (2024) Blockchain technology in the agri-food supply chain: a systematic literature review of opportunities and challenges. Manage Rev Q. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-023-00390-0

Vo S (2016) Concern for community: a case study of cooperatives in Costa Rica. J Community Pract 24(1):56–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705422.2015.1127304

Wanyama SB, McQuaid RW, Kittler M (2022) Where you search determines what you find: the effects of bibliographic databases on systematic reviews. Int J Soc Res Methodol 25(3):409–422. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2021.1892378

World Co-operative Monitor (2023) Exploring the Cooperative Economy: Report 2023. EURICSE-ICA, Available online https://www.uk.coop/sites/default/files/2024-01/wcm_2023_2.pdf. Accessed 22 February 2024

Yassin Y, Beckmann M (2024) CSR and employee outcomes: a systematic literature review. Manage Rev Q. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-023-00389-7

Yin RK (2015) Qualitative Research from Start to Finish, Second Edition. The Guilford Press, New York

Yosun T, Cetindamar D (2022) A typology of competitive strategies for Social enterprises. J Social Entrepreneurship. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2022.2148268

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Compliance with ethical standards

Hereby, I Tomas Sparano Martins assure that for the present manuscript the following is fulfilled:

1) This material is the authors’ own original work, which has not been previously published elsewhere.

2) The paper is not currently being considered for publication elsewhere.

3) The paper reflects the authors’ own research and analysis in a truthful and complete manner.

4) The paper properly credits the meaningful contributions of co-authors and co-researchers.

5) The results are appropriately placed in the context of prior and existing research.

6) All sources used are properly disclosed.

7) All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Flávio Luiz Von Der Osten, Tomas Sparano Martins, Hao Dong and Adrian R. Bailey. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Flávio Luiz Von Der Osten and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

8) Sources and data supporting the findings of this study were all publicly available at the time of submission.

9) The research did not involve Human Participants and/or Animals.

Funding and conflict of interest statements

1) The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

2) The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

3) The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

4) All authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

5) The authors have no financial or proprietary interests in any material discussed in this article.

I declare that this submission follows the policies of Management Review Quarterly as outlined in the submission guidelines.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Osten, F.L.V.D., Martins, T.S., Dong, H. et al. What does the 7th cooperative principle (concern for community) really mean?. Manag Rev Q (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-024-00421-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-024-00421-4