Abstract

Prioritising sustainable development goals (SDGs) is one of the fundamental approaches to achieving global sustainability objectives, as it helps efficient resource allocation, addresses urgent needs, enhances policy coherence, and measures impact. Despite existing efforts, there remains an unclear understanding of the key factors needed for effective SDG prioritisation, presenting challenges for strategic planning and decision-making. This study provides an evidence-based analysis of these critical factors by examining relevant literature, conducting surveys, and employing Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP)-based Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA). The study identifies four primary factors for SDG prioritisation: SDG interrelations, performance, scope, and alignment. The findings confirm that national prioritisation have more priority compared to global, regional, and sub-national systems, and that prioritisation is more valuable at the indicator level rather than at the goal or target levels. Additionally, prioritisation should initially focus on off-track SDGs. Notably, academia ranks SDG prioritisation based on relationships and performance highly, while government officials emphasise alignment and relevance. Moreover, the results indicate that academia prefers target-level prioritisation, while government officials lean towards indicator level. However, both groups favour national scale over global and regional scales.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The concept of Sustainable Development (SD) has gained significant attention in recent years (Mensah 2019). It has become increasingly evident that our current development pathways need substantial enhancements to promote development that is environmentally, socially, and economically sustainable (Niemets et al. 2021). To address this challenge, the sustainable development goals (SDGs) were established by the United Nations in 2015 as a set of 17 interconnected goals that aim to address global challenges such as poverty, inequality, climate change, and environmental degradation (UN 2015). The SDGs are intended to be accomplished by 2030 and beyond, and their successful completion is imperative for the planet's sustainable future.

Several authors have raised criticisms of the SDGs. For instance, there is an argument that the SDGs fail to address the underlying drivers of environmental degradation and social inequality, suggesting that they are more focused on economic growth than genuine sustainability (Scholtz and Barnard 2018). Similarly, Spaiser et al. (2017) contend that the SDGs often present conflicting goals, where progress in one area may undermine efforts in another, thus complicating the pursuit of comprehensive sustainability. SDGs are also being criticised for their broad and sometimes vague targets, which can lead to challenges in implementation and measurement (Biermann and Kanie 2017). Despite these criticisms, the SDGs have been recognised as an effective roadmap to measure and improve sustainability (Weitz et al. 2015).

Since the adoption of SDGs, countries have employed various approaches to institutional mechanisms for coordinating and implementing them as reported by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP 2017). Despite the effort, achieving SDGs is complicated by the scarcity of resources, competing national priorities, the need to address fallout from global crises like the COVID-19 pandemic, and the complicated nature of the goals. As a result, the simultaneous achievement of all SDGs is an unrealistic proposition (Allen et al. 2019a, b; Collste et al. 2017). The UN promotes equal attention to all 17 SDGs, yet this does not imply equal distribution of resources among them (Xiao et al. 2022). Moreover, given the vast scope of the SDGs, it is essential to identify which goals and targets should be prioritised to achieve the greatest impact and ensure the most efficient use of limited resources. This raises questions about which SDGs should be at the forefront (Ruiz-Morales et al. 2021).

SDG prioritisation serves as a compass, guiding policy decisions and investments on both national and international stages (Bandari et al. 2022). In this way, governments, international organisations, and donors can leverage prioritisation to allocate resources, design effective policies and programs, and monitor progress towards the SDGs (Kunčič 2019). Prioritising certain SDGs allows for targeted interventions that can create the most significant positive change in a shorter period. This approach ensures that efforts are concentrated on areas where they can make the most substantial impact (Asadikia et al. 2021). Beyond that, clear priorities can help mobilise stakeholders, including governments, businesses, and civil society, around common goals. This alignment can enhance cooperation, foster partnerships, and ensure that efforts are coordinated and complementary (Soberón et al. 2020). Furthermore, prioritisation facilitates dialogue and engagement among different sectors, including civil society, private sector, academia, and local communities, paving the way for more inclusive and effective sustainable development strategies (Koch et al. 2019; Mohd Salleh et al. 2023; Yaw Ahali 2022).For instance, managing cross-sectoral coordination in accelerating the sustainable development agenda is highlighted in the work by Berawi (2021), which discusses how prioritisation allows for effective engagement among different sectors, ensuring that the SDGs are implemented more inclusively and effectively.

There is evidence of SDGs prioritisation at both governmental level (e.g. Horn and Grugel 2018; UN 2020) and within organisations (e.g. Heras-Saizarbitoria et al. 2022). Yet, this prioritisation often hinges on political preferences or, at times, seems to be lacking any clear guiding criteria. It is also important to note that making progress towards one SDG target can sometimes negatively affect others due to their interconnectedness (Nilsson et al. 2016). This raises questions about the strategic considerations underlying SDG prioritisation, knowing that without an effective prioritisation, resources may be scattered across too many goals or allocated to less impactful areas, leading to slower progress overall (Lomborg 2015). To ensure that efforts are directed towards the most impactful areas, avoiding negative impacts on the overall progress of SDGs, and effective implementation of SDGs by developing a systematic and evidence-based prioritisation approach is crucial.

While numerous studies have highlighted the need for an effective prioritisation system to achieve the SDGs (e.g. Weitz et al. 2018), there remains a lack of clarity regarding the essential factors that should be involved in such an approach. This ambiguity contributes to the absence of a robust prioritisation mechanism, a deficiency often recognised as a key obstacle in accomplishing the targets and indicators of the SDGs (Oliveira et al. 2019). This knowledge gap intercepts optimum allocation of resources and can result in suboptimal outcomes in operational planning for improving the progress of SDGs. To address this challenge, there is an urgent need for a comprehensive and evidence-based understanding of the factors that are essential to effectively prioritise SDGs. This understanding will help scholars to design a prioritisation system which assists decision-makers to identify and set policies that have the most significant potential for impact and allocate resources accordingly.

This study aims to bridge the identified knowledge gap by identifying, categorising, and ranking the critical factors to consider in an SDG prioritisation system. This article endeavours to answer two pertinent questions: (a) What are the factors for prioritising SDGs? and (b) What are their priority to be involved in a SDGs prioritisation system?

In carrying out this investigation, we initially extracted factors related to SDG prioritisation through a comprehensive and systematic review of existing literature. Subsequently, the analytical hierarchy process (AHP)-based multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) model was designed to determine the relative importance and priority of those factors. This study aims to advance the understanding of SDG prioritisation factors using structured and evidence-based methods.

Methods and materials

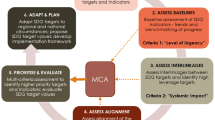

This research employed three main stages (Fig. 1) to identify factors and their relative importance that should be involved in an SDG prioritisation system. This section explains all the stages in detail.

Stage one: literature search

To identify the required factors for a prioritisation system, the question of “What are the suggested factors for SDGs prioritisation?" served as the foundation of the literature review process, helping to identify relevant literature and guide the analysis. By "factors" in this context, we refer to the key aspects and considerations that influence the prioritisation of SDGs. In this stage, relevant scientific research was discovered through literatures found in two leading academic databases [Scopus and Web of Science (WoS)]. Both WoS and Scopus are among the most well-known scientific database that index the majority of English academic journals as the leading databases for citation and bibliographical searching (Meho and Yang 2007). These platforms are comprehensive search engines that provide scholars, and professionals with access to a vast collection of articles, conference proceedings, and other academic resources. Since our objective is to explore the factors for SDG prioritisation, we focus exclusively on articles published after the introduction of the SDG framework (2015). To collect related articles, we conducted a search across both platforms, focusing on English language academic articles and conference papers published from 2015 to 2022. To refine our search, we employed a Boolean query as ‘("sustainable development goal*" OR "sdg*") AND "priorit*"’ which were applied to all fields. We also excluded unrelated categories such as medicine and art.

Following the collection of articles, a citation analysis was performed using VOSviewer to determine the most relevant articles. We used direct citation analysis since it is identified as one of the most accurate representations of the taxonomy of scientific and technical knowledge (Klavans and Boyack 2017). It also uncovers relationships between articles, revealing potential connections and assists researchers in excluding documents that are not connected (van Eck and Waltman 2017). Moreover, employing citation analysis software mitigates the potential for human error when identifying relevant articles. This analysis was conducted for collected articles from both Scopus and WoS separately to exclude disconnected documents.

Next, duplicated articles were excluded using EndNote software and the remaining are passed to the pre-screening stage. Then articles with irrelevant titles and abstracts that used the word "priorit*" for concepts unrelated to SDGs were excluded: for instance, an article (Hosseinpoor et al. 2015) mentioning health equity as a priority, but lacks evidence of SDGs as a priority. The remaining articles undergo full-text screening using six guiding questions listed in Table 1. An article was excluded if none of the questions receive a 'yes' answer. We then extracted factors suggested in those articles for SDGs prioritisation.

Then reference mining using the backward snowballing technique was conducted from the filtered articles to identify other potentially relevant documents that might have been missed. These newly identified documents were collected and then returned to the pre-screening stage, and if relevant, moved to full-text screening.

Stage two: factor extraction

In stage two, we carried out factor extraction through synthesis and frequency analysis (FA) to identify the most commonly cited factors. The factors extracted from full-text screening were refined by grouping related terms together and counting the occurrences of each unique term. For our frequency analysis, we set a threshold of three, thus concentrating on factors that were mentioned or suggested more than three times.

Stage three: AHP framework development

To identify the relative importance of factors for SDGs prioritisation, we utilised the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), which is one of the Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) methods proposed by Saaty (1977, 1988), to aid in decision-making. AHP determines the relative importance of a set of criteria by conducting pairwise comparisons between them. The fundamental concept of AHP involves breaking down a complex problem into a hierarchical structure (Saaty 1988). Criteria within a specific hierarchical level are compared in pairs to evaluate their relative preferences concerning the criteria in the next higher level. This method is identified as one of the popular methods in the SDGs field (Koasidis et al. 2021) and MCDA (Vaidya and Kumar 2006). In this article, we use the term "criteria" for the extracted keywords when applying the AHP-based MCDA method. Outside of this method, we refer to them as "factors" to align with the paper's purpose of identifying key aspects for SDGs prioritisation.

Moreover, AHP does not mandate making choices among all criteria, reducing the likelihood that respondents will resort to mental shortcuts by concentrating excessively on a single attribute or level (Saaty 1977, 1988).This method has demonstrated its usefulness in addressing complex problems related to sustainability such as designing alternative future outcomes for developing countries (Amer and Daim 2011), evaluating policies (Shi et al. 2008) and strategies (Lee et al. 2001), allocating energy resources (Ramachandran 2004; Wang et al. 2009), and sustainable development area (e.g. Han et al. 2023; Krajnc and Glavic 2005; Lee et al. 2009; Sengar et al. 2022; Seuring 2013).

Another significant advantage of the AHP lies in its ability to function effectively without necessarily relying on a statistically significant sample size (Dias and Ioannou 1996). This characteristic eliminates the need for intricate survey designs (Whitaker 1987). Since input data is derived from expert judgements, a single input typically represents a group of individuals within the sample data (Golden et al. 1989). This method is frequently employed to rank decision criteria, typically to determine the most favourable alternative. However, in this study, the focus is on identifying the relative importance of criteria rather than decision alternatives. Therefore, similar to studies that used AHP to prioritise criteria and sub-criteria (e.g. Hashim et al. 2021; Numata et al. 2020; Sengar et al. 2022), we have intentionally excluded alternatives. This simplification not only streamlines the process, but also enhances its comprehensibility. Subsequently, through pairwise comparison, we evaluate the relative importance of each criterion and sub-criterion.

In this research, the problem involves applying AHP on two levels: (1) estimating the relative importance of the primary criteria, and (2) estimating the relative importance of sub-criteria within the main criterion.

To apply AHP, a matrix representing the relative importance of all criteria is defined as:

In this definition, 'n' denotes the number of criteria present at the same hierarchical level, thus facilitating the comparison and analysis of their relative significance.

The comparative significance of a criterion within the same hierarchical level is obtained using Eq. (1).

where \(W={\left({\omega }_{1}, {\omega }_{2},{\omega }_{3},\dots ,{\omega }_{n}\right)}^{T}\) is the priority vector (weights), which can be obtained by solving the linear system \(AW=\uplambda W, {e}^{T} W=1,\) where \(\uplambda\) is the principal eigenvalue of the matrix.

Two methods that are deemed highly effective in AHP group decision-making processes include the consolidation of individual judgements and the combination of individual priorities (Dong et al. 2010). Since it is observed that consolidation of individual judgements might violate the Pareto principle of social choice theory (Ramanathan and Ganesh 1994), we used the combination of individual priorities method to obtain the collective priority vector.

Suppose we set P = \(\{{p}_{1},{p}_{2},\dots , {p}_{m}\}\) to be the set of participants, and \(\uplambda =\{{\uplambda }_{1},{\uplambda }_{2},\dots , {\uplambda }_{m}\}\) symbolising the weight vector associated with these participants, where for each participants \({\uplambda }_{k}\) is non-negative, and \(\sum_{k=1}^{m}{\uplambda }_{k}=1\).

Let us assume that \({A}^{(k)}=({a}_{ij}^{\left(K\right)}{)}_{n\times n}\) stands for the judgement provided by each participant \({p}_{k }(k=\text{1,2},\dots ,m)\).

In the combination of individual priorities method, we assume that \({W}^{(k)}=({W}_{1}^{\left(K\right)},\dots ,{W}_{n}^{\left(K\right)}{)}^{T}\) represents the individual priority vector that results from the individual judgement matrix \({A}^{(k)}\) through the eigenvalue method. Then, the group priority vector acquired by applying the combination of individual priorities is calculated based on Eq. (2).

where

We then designed and developed a questionnaire as a tool for assessing the relative importance of the criteria with the AHP model. The questionnaire comprises three sections, namely Participant's Information (Section A), Pairwise Comparison (Section B), and Other Suggested Criteria (Section C). Section B, which is the core of the questionnaire, was further divided into two sub-sections: pairwise comparison between criteria (Section B1) and pairwise comparison between sub-criteria (Section B2). Through this questionnaire, the study aimed to collect data to facilitate the application of the AHP-based MCDA model and evaluate the relative importance of factors to the primary objective.

We used original relative importance scales suggested by Saaty (1980) for the pairwise comparison as shown in Table 2.

In Section C, we incorporated open-ended questions as listed in Table 3, and also invited participants to suggest any other factors not mentioned in Section B.

To disseminate the survey, potential participants were identified from several sources. Primarily, the corresponding authors of highly cited journal articles relating to SDGs prioritisation, as determined in Stage 1 of the methodology, were targeted. Additionally, online platforms and social media, such as LinkedIn and ResearchGate, were employed to locate individuals from various sectors with expertise in SDGs. Particular attention was given to those who may be involved in decision-making processes (e.g. SDG policy advisor, SDG strategy consultant, SDG project coordinator).

Furthermore, potential participants were identified among attendees of workshops and seminars focused on sustainable development or related fields, facilitating connections with individuals interested in the subject matter. In total, the questionnaire was distributed to 92 potential candidates, ensuring a diverse and representative sample of perspectives from academia, government, and industry.

When applying the AHP, inconsistencies may emerge in pairwise comparisons due to various factors, such as insufficient knowledge, inappropriate hierarchy conceptualisation, or an inadequate sample size (Dong et al. 2010). Upon completing the pairwise comparisons, a consistency ratio is generated for each prioritised scale, which serves to assess the coherence of the judgements. The consistency ratio is determined by dividing the consistency index for a specific set of judgements by the average random index shown in Eq. (3).

Here, \({\lambda }_{\text{max}}\) represents the maximum eigenvalue, while 'n' represents the size of the judgement matrices. The values of RI for different sizes of judgement matrices are listed in Table 4 based on values suggested in the original method by Saaty (1977, 1988).

Saaty (1980) suggested that an acceptable consistency ratio (CR) must be less than or equal to 0.10, regardless of the problem's nature, to indicate tolerable inconsistency. If this criterion is not met, it is advisable to revise the comparisons. A consistency index of zero, which corresponds to a consistency ratio, would represent perfectly consistent judgements (Whitaker 1987). It is crucial to emphasise that an acceptable CR ensures that no unacceptable discrepancies exist within the comparisons made, and that the decision is logically sound, rather than a product of arbitrary prioritisation in the AHP.

Result

The research question, "What are the proposed factors for SDGs prioritisation?" formed the basis for this study facilitating the identification and analysis of relevant literature as explained in "Methods and materials". Figure 2 illustrates the outcomes of stage one, which pertain to extracting factors from the systematic literature review.

A total of 2051 articles were extracted from both the Scopus and WoS databases, with citation analysis performed separately for each dataset. Figure 3 illustrates the results of citation analysis. Articles with numerous connections to others form the centre of the depiction, while those with fewer or no connections sit on the periphery. For our study, we included documents that were either cited by other articles or contained citations found within our established citation network. As a result, any articles completely lacking connections within the citation network were systematically excluded (1455 articles). Among the connected articles, 119 were found to be duplicates and were excluded.

The iterative process of pre-screening, full-text review, and reference mining resulted in a total of 107 documents. These included articles with and without the selected keywords, as well as documents from grey literature, all of which related to SDGs prioritisation. It is important to acknowledge that certain articles delve into the complexities of interrelationships among the SDGs, enhancing our understanding of these connections (e.g. McGowan et al. 2019; Putra et al. 2020), yet without specifically focusing on SDG prioritisation. For instance, one of the pioneering studies examining SDG connections analysed the strength of goal linkages (Le Blanc 2015), but did not explicate that enhancement of these particular SDGs might significantly drive overall SDG progression.

There are also articles which prioritise policies, but not the SDGs (e.g. Moyer and Bohl 2019; Obersteiner et al. 2016) which have not been incorporated into our final list. Additionally, we identified eight articles (e.g. Chan 2020; Chapman and Shigetomi 2018) that carried out SDG prioritisation without suggesting specific factors for such prioritisation. These studies primarily employed pairwise comparison or relied on subjective preferences for prioritisation, and consequently, they have been excluded in the stage 1 of the methodology.

The factors proposed by the examined articles were combined into four main categories: (i) relationships and interlinkages, (ii) performance, (iii) alignment and relevance, and (iv) other. Table 5 provides a detailed enumeration of these factors, alongside the frequency of appearance in literature. It also shows the growing scholarly interest in the prioritisation of SDGs in recent years.

To clarify these categories, "Relationships and Interlinkage" refers to the interconnectedness and interactions between different SDGs, highlighting the impact that SDGs have on each other, both synergies and trade-offs. Synergies occur when actions taken towards one SDG mutually benefit progress towards other SDGs. For example, positive progress in achieving SDG 4 and SDG 3 can significantly enhance the achievement of other SDGs (Asadikia et al. 2021). Conversely, trade-offs happen when advancing one SDG might hinder progress on another. For instance, intensive industrial growth (SDG 9) might lead to environmental degradation (SDG 15), posing a challenge to sustainable development.

"Performance" as a factor for SDG prioritisation refers to the current status and progress in achieving specific SDGs. This performance is evaluated based on measurements and reports of relevant indicators, targets, and goals and how much they are being met over time. In other words, it involves assessing how well a country or region is doing in terms of reaching the established benchmarks for each SDG. By examining these indicators and reports, decision-makers can identify which goals are on track and which need more attention.

"Alignment and Relevance" as a factor for SDG prioritisation refers to how well each SDG aligns with the specific goals, needs, and priorities of a country or region. This factor assesses the relevance of each SDG to the local context, considering factors such as national development plans, policy frameworks, and socio-economic conditions. To clarify, the alignment involves ensuring that the SDGs resonate with the existing policy environment and development agendas at various governmental levels, thus facilitating smoother implementation and integration.

It is noteworthy that certain articles suggested multiple factors, hence, they might appear more than once in the table, each time associated with a different factor.

Factors mentioned more than a threshold (3 times) have formed the hierarchy for the AHP analysis. Table 6 lists the hierarchy structure of criteria and sub-criteria. In this study, the primary objective is to identify influential factors for SDGs prioritisation. Consequently, the main objective, "Most Influencing factors in Prioritising SDGs " is positioned at the top of the analytical hierarchy in level 0. The three main factors of "Alignment and Interlinkage", "Alignment and Relevance", and "Current Performance" have been allocated as criteria. Since each of those factors are used to identify SDGs priorities at different scopes (Global, Regional, National, Sub-national) the "Collaborative Scope" is also considered as a criterion to identify its importance when designing a prioritisation system. Then after the main objective in level zero, for the second level (level 1) four main criteria are included as Alignment and Relevance (C1), Relationships and Interlinkage (C2), Collaborative Scope (C3), and Current Performance (C4). To have more specific details for the SDGs prioritisation system, the next level of hierarchy incorporates three sub-criteria for C2 as "Synergetic Goals", "Synergetic Targets", and "Synergetic Indicators", four sub-criteria for C3 as "Global", "Regional", "National", and "Sub-national", and two sub-criteria for C4 (Current Performance) as "off-track" or "on-track but needs improvement".

Table 6 itemises each criterion and sub-criteria along with their respective descriptions, and their source. There is no universally correct hierarchy for a given system, and multiple hierarchies can be constructed based on differing perspectives.

Following the establishment of the analytical hierarchy, the subsequent step entails pairwise comparison of the criteria and sub-criteria at the same level to assess the relative contribution of these factors to the primary objective.

The responses of participants who met the following criteria were included in the analysis: (i) having over a year of work experience in this domain or conducting research related to SDGs, (ii) maintaining a reasonable level of involvement with SDGs in their professional or research activities (at least fairly involved), and (iii) demonstrating an acceptable consistency ratio (CR) (less than or equal to 0.10) in their responses. The question about whether the participant is a decision-maker shows that the majority (90%) of decision-makers work in the government sector (See Appendix). This observation aligns with expectations, as there is no dedicated industry or academic department that leads the SDG decision-making process. Although universities provide valuable insights into improving SDG achievements, key policies are formulated and implemented at the government level. The responses to Section A of the questionnaire (Participant Information) are provided in the Appendies (Tables 9 and 10).

A MCDA process based on AHP was conducted on the three categories of respondents: Government, Academia, and All Participants. A separate analysis was not conducted for respondents from the 'Industry' category due to the low number of participants from this group who met the aforementioned criteria. The lack of consistency in their responses may indicate a low level of involvement and knowledge of SDGs prioritisation within the industry sector. Note that the ‘All Participants’ include all three categories of Government, Academia, and Industry.

The first MCDA process based on AHP was conducted on the level 1 of the hierarchy to identify the priority level of the criteria which were identified through the systematic literature review: C1: alignment and relevance, C2: relationships and interlinkage, C3: collaborative scope, and C4: current performance. In the next stage, for C2, C3, and C4, to obtain more granular results, we performed the same process on the sub-criteria level of the hierarchy. The SDGs prioritisation factors with their relative importance is illustrated in Fig. 4.

An analysis of the results reveals two key categories 'Relationships and Interlinkage' and 'Current Performance' that stand out as critical for the SDGs prioritisation system. These categories not only exhibit the highest relative importance, thereby securing the first rank, but they also underscore their vital role in the effective prioritisation of SDGs. Closely following is the 'Alignment and Relevance' category, which takes the second spot in influencing factors. Coming in at the third rank is the 'Collaborative Scope' category. However, it is important to note that the difference in priority of these factors is less than 10%. This emphasises the importance of all these factors.

The detailed results of AHP-based MCDA process are presented in Table 7 separated by different groups of experts, 'Academia', 'Government', and 'All Participants' (Academia, Government, and Industry).

To visualise the similarities and differences between the importance of criteria and the corresponding sub-criteria for designing a prioritisation system from the Government and Academia perspectives, the results of MCDA process based on AHP analysis is also depicted in a number of radar charts.

With respect to comparing the perspectives of respondents regarding the criteria (level 1) for designing a SDGs prioritising system, it can be observed that the respondents form the Government category have indicated the following importance level: 'Alignment and Relevance' (30.8%), 'Current Performance' (29.2%), 'Relationships and Interlinkage' (20.9%), and 'Collaborative Scope' (19.1%). The opinion of the respondents from the Government category differ from those in Academia regarding 'Relationships and Interlinkage' (31.1%), 'Current Performance' (27.4%), 'Alignment and Relevance' (21.8%), and 'Collaborative Scope' criteria. Both groups agree that 'Current Performance' is a crucial criterion, while 'Collaborative Scope' (19.7%) is considered less important compared to the other criteria. The key similarities are related to the 'Current Performance', and on the other hand, it is very interesting to observe that for two criteria of 'Alignment and Relevance' and 'Relationships and Interlinkage', there is a mismatch between the two categories of respondents (Fig. 5).

Government executives believe that 'Alignment and Relevance' should be considered with higher priority compared to the 'Relationships and Interlinkage', whereas Academics have reported the opposite priority consideration. It is also informative to compare these finding with the 'All Participants' category which include the participants who are active in an industry which is relevant to managing SDGs: 'Relationships and Interlinkage' and 'Current Performance' (28.6%), 'Alignment and Relevance' (23.5%), and 'Collaborative Scope' (19.3%). This suggests that in the results of 'All Participants' category, the magnitude of difference between categories is fairly moderated; however, the reported importance levels are similar to the category of Academia.

Moving to the next level of AHP hierarchy (sub-criteria level), first, we review the pairwise comparison for the sub-criteria of 'Relationships and Interlinkage'. Reviewing the reported priority level which has been indicated by the Government executive shows the following preferences: 'Synergetic Indicator' (45.2%), 'Synergetic Target' (29.7%), and 'Synergetic Goal' (25.1%). This is a clear indication that for the Government category who are the key decision-makers in allocating resources for improving the SDG achievements, the details (indicator-level drivers) are crucial for developing a prioritisation system. This is however not identical with the order of priority levels which has been reported by the Academia: 'Synergetic Target' (50.8%), 'Synergetic Indicator' (30.9%), and 'Synergetic Goal' (18.3%). This outcome still confirms that extra attention should be paid to the synergetic indicators, and targets compared to goals. However, it strongly stresses that the main driver for designing a prioritisation system should be synergetic targets. Visual inspection of Fig. 6 also confirms that there is a considerable gap between the opinion of Government executives and Academics to employ the synergetic indicators or targets as the key design driver of a prioritisation system. Finally, considering the responses of all participants including the category of Industry, it can be seen that under the criterion of 'Relationships and Interlinkage', both 'Synergetic Indicators' (42.6%) and Targets (38.2%) are nominated to be the crucial factors, whereas focusing on solely 'Synergetic Goals' (19.2%) is not an appealing design driver.

Regarding the sub-criterion of 'Collaborative Scope', respondents were requested to perform a pairwise comparison between the importance of considering the scale of designing a prioritisation system in either 'Global', 'Regional', 'National', or 'Sub-national' levels.

This is the first design driver criterion that all three categories of Government executives, Academia, and 'All Participants' have a consensus on the most important sub-criteria as a driver for designing a prioritisation system. All three categories of participants outlined that considering the 'National' (41.4, 40.2, 41.1%) and 'Sub-national' (30.0, 33.5, 35.4%) scales for the scope of design is more crucial compared to the 'Global' (12.7, 12.8, 12%) and 'Regional' (15.9, 13.5, 12%) scales, respectively. This finding can be readily observed in Fig. 7 as the direction of decision is relatively similar for all categories of respondents; however, designing a prioritisation system in the 'National' level is strongly supported.

The last sub-criteria (level 2) which are investigated in this study are related to the criterion (level 1) of 'Current Performance'. Two viewpoints have been assessed in this part of the analysis regarding the current rate of progress towards SDG achievements. Is it more important to pay attention to the goals, targets, or indicators with progress that is currently off-track, or the items for which their progress is on-track but needs further improvement to be achieved by the designated year? Note that the answer to this question is not trivial, as the current progress level of an on-track item does not guarantee meeting the threshold in the remaining time. In other words, although the progress level of a goal, target, or an indicator is currently satisfactory, to meet the final objective, performing further improvements is crucial. Regarding the two sub-criteria of 'Current Performance', the magnitude of priority levels is not quite similar for the three respondents’ categories (Government executives, Academia, and all participants); however, the same sub-criterion of considering the off-track items (83.3, 66.7, 75.0%) is recommended for designing a productive prioritisation system in contrast to focusing on the sub-criterion of 'On-track but needs improvement' (16.7, 33.3, 25.0%). Figure 8 also confirms this finding on a two-dimensional radar chart. This visualisation, however, demonstrates that the group of Academia values 'On-track but needs improvement' more than Government and Industry groups.

Alongside the structural framework used in this study to examine the pairwise importance of criteria and sub-criteria gathered through the systematic literature review phase, we also posed some open-ended questions that offered further insights, as shown in Table 8.

The survey responses revealed an overwhelming consensus among experts on the necessity of a prioritisation system for optimally utilising limited resources to achieve the SDGs. Most respondents categorised it as "absolutely necessary and important". Some emphasised that such a system could provide a decisive path for decision-makers by identifying priority areas. There were also perspectives on the impossibility of achieving all SDGs simultaneously, making prioritisation crucial. Additionally, one response highlighted that prioritisation is a concept already widely used in other sustainability reporting, such as the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI). However, GRI are provided subjectively without any specific method to measure the impact of SDGs. While several respondents highlighted the critical role of national and regional affluence in identifying priorities, they also stressed the need for a holistic and systematic approach to prioritisation, rather than cherry-picking objectives. When asked whether incorporating a prioritisation system into the decision-making process could improve progress towards achieving the SDGs, the majority of the experts responded affirmatively. However, they stipulated that the system's efficiency is critical to its effectiveness. Some experts highlighted the need for the prioritisation system to take into account not just the SDGs themselves, but also their relative demands for resources. While some warned against the pitfalls of 'picking winners', arguing for a holistic approach to consider the SDGs, they also acknowledged that prioritisation could serve as a good starting point, provided it was accompanied by rigorous implementation and follow-up. Thus, the responses largely support the view that an efficient, holistic prioritisation system could significantly enhance the progress towards achieving the SDGs.

Discussion

It is fundamental for entities at various governmental levels to implement an efficient system for SDG prioritisation. This practice aids in optimising the allocation of constrained resources (Pineda et al. 2021), thereby maximising progress towards the attainment of the SDGs without necessitating additional resources. In the absence of efficient prioritisation, resources might be dispersed among numerous objectives or directed towards areas with lower impact, which could result in a decelerated overall progress (Asadikia et al. 2023; Lomborg 2015). Therefore, it is essential to establish a prioritisation system to ensure that public policies and resource allocations for the implementation of SDGs lead to significant and meaningful outcomes.

The current study has tried to explore the influencing factors for designing an effective SDGs prioritisation system. In the first part of the study, a systematic literature review was conducted to identify factors which were recommended by scholars for prioritising SDGs in the current body of knowledge. Then, the results of the first stage were used in the second part of the investigation, using the MCDA process based on AHP method, to identify which criterion and sub-criteria were considered to be more important in designing a SDGs prioritisation system from the perspective of three respondents’ groups: Government, Academia, and All (Government, Academia, and Industry).

Our findings strongly reinforce the significance of incorporating SDG performance, relationships, and alignment as critical factors in an effective SDG prioritisation system. While the pairwise comparisons indicate a lower priority for 'Collaborative Scope', it is important to note that the other highly ranked criteria heavily rely on the specific scope in which they are identified and measured.

To elaborate further, the relationships and interlinkage between SDGs exhibit variations across different scopes, including Global, Regional, National, and Sub-national (Asadikia et al. 2022; Ionascu et al. 2020; Miola et al. 2019). Similarly, the alignment and relevance of prioritised SDGs can vary depending on the specific scope and context (Antwi-Agyei et al. 2018). It is worth considering that the relevance of SDGs prioritised at the national scope may differ from those deemed relevant at the sub-national level. Take SDG 6, 'Ensure access to water and sanitation for all', for example. While it may be a priority at the national scale, particularly for vulnerable and regional areas, its relevance may not be as significant when considering a sub-national scale, such as an urban area. Consequently, when assessing the importance of alignment, relationships, and performance, the collaborative scope also holds considerable influence. This highlights the need to consider the specific contexts and scopes when prioritising SDGs.

There are however some interesting findings if we look into the sub-criteria level of the 'Collaborative Scope'. Our results also emphasise the importance of a prioritisation system for the national scope. This may be due to some reasons. To begin with, national governments have greater control and authority over policy decisions and resource allocation within their own jurisdictions and it enables better alignment with existing national policies, plans, and strategies (Kostetckaia and Hametner 2022). Next, prioritising SDGs at the national scale fosters local ownership and encourages active engagement from various stakeholders, including civil society, private sector, and local communities (Koff et al. 2020). Additionally, national-scale prioritisation benefits from the availability of localised data and statistics (Allen et al. 2020), which facilitates better monitoring and evaluation of progress. At this scale, countries can integrate the SDGs into their existing frameworks and adapt them to suit their specific development agendas. This alignment ensures coherence between national goals and the SDGs, promoting effective implementation and monitoring.

The outcomes also highlight the crucial role of the 'Current Performance' in designing a SDGs prioritisation system. This confirms that envisioning any improvement plan for SDGs should be based on the current performance of SDGs and developing a prioritisation system without taking into account the existing performance of the SDGs would be inefficient. To be more precise, all parties concur that within the 'Current Performance' sub-criteria, it is substantially more crucial to concentrate on SDGs with 'off-track' progress rate when developing a prioritisation system. If we also consider the priority of 'Relationships and Interlinkage' sub-criteria, synergetic SDG indicators that are off-track receive higher priority to be involved in a prioritisation system. However, it should be noted that we need to be careful regarding this recommendation as it may vary depending on the current marginal improvement attempts which are required to keep an on-track item to stay above the minimum threshold. If this margin would be so small, this type of on-track but synergetic indicators may receive extra priority in the SDGs prioritisation system.

Another interesting finding of this study, is the observed discrepancy between the perspectives of Government and Academia regarding the importance of criteria for developing a prioritisation system, specifically related to the 'Alignment and Relevance' and 'Relationships and Interlinkage' criteria. This divergence in views can be attributed to several factors. One reason could be the knowledge gap within governments regarding the complex nature of SDG implementation and the potential influence of interrelationships among goals. In academia, a significant number of scholars investigate the relationships and interlinkages between SDGs (see Bennich et al. 2020) and recognise their importance. However, this understanding might not be effectively communicated within government circles. Another reason could be the prioritisation of national interests over the broader SDG agenda. Additionally, the gap between government and academia may arise from the separation between academic research and SDG decision-making processes within government entities.

It is essential for Academia to consider that decision-makers value alignment and relevance, and a prioritisation system solely based on relationships, interlinkage, or performance may not be practical for implementation in the decision-making process. For instance, it would be reasonable for a government executive to assign less weight to the 'Life Below Water' goal if their country has limited or no marine resources. Similarly, in some countries, addressing obesity may take precedence over SDG 2 (Zero Hunger), making it less relevant to their prioritisation system. Another example is the indicator of 'Controlling Tropical Diseases', which may be irrelevant to many countries and less aligned with proposals to improve SDG achievements. Therefore, it is important to recognise that even if certain SDGs are highly synergetic or exhibit low performance, their relevance to a specific context must be carefully considered for their prioritisation. It is also noteworthy that a prioritisation system can be established at different scopes and levels, such as Global, Regional, National, or Sub-national, and what is relevant and aligned with one level's plan may be less applicable to other levels within the decision-making hierarchy.

This finding is highly significant, as it highlights an aspect that has been overlooked in many academic studies, which often focused solely on 'Relationships and Interlinkage' or 'SDG performance' as the sole factors for prioritisation. Our insight suggests that a filtering phase should be incorporated at the outset of an academic project to screen out irrelevant, less relevant, and misaligned goals, targets, or indicators. Future studies can explore quantifying the degree of relevance or alignment that should be considered during the screening stage without compromising the indivisible nature of the SDGs. However, while filtering is necessary, caution should be exercised to avoid politically motivated prioritisation or cherry-picking of SDGs based on the perceived level of implementation complexity. Scholars should approach the filtering process with care, ensuring that it aligns with the broader objectives of the SDGs and the principles set by the UN.

Drilling further down into the sub-criteria of ‘Relationships and Interlinkage’ also provides interesting insights. Although both government and academia sectors concur that the ‘Synergetic Goal’ is of lesser importance than targets and indicators, government executives suggest that prioritising synergetic indicators are the most influential factor in a prioritisation system, whereas academics indicate that synergetic targets hold this position. From the government’s perspective, the most practical way of improving a system is to develop action plans and policies for the most detailed level in network with complex interlinkages to address the issues of the corresponding level. Therefore, since the indicator level is the most tangible component of the SDGs network (Allen et al. 2017), it would be more practical for the government executives to formulate a policy to improve the status of a particular indicator. Moreover, the implementation of SDGs and the development of strategies and policies to improve specific indicators facilitate the identification of relevant stakeholders and the allocation of necessary resources. This approach adopts a bottom-up perspective, empowering stakeholders at various levels to actively participate in the process and contribute to the achievement of SDG targets.

However, it is important to note that SDGs indicator-level prioritisation may not be the most attractive aspect for academics due to certain constraints. For instance, the scarcity of available data at the indicator level and the wide variety of indicators may present challenges and limitations in the prioritisation process. To address this, we suggest a collaborative approach between government and academia to improve prioritisation accuracy. Governments could assist with data collection, and academics could apply advanced methods to better use indicators in system design. However, data availability remains a challenge in many countries.

The survey also provided a platform for experts to suggest their own criteria and sub-criteria for SDG prioritisation. Among the suggested criteria were factors such as politics, religion, and personal motives including the maintenance of wealth or shareholdings. This introduces an element of real-world pragmatism, acknowledging that decision-makers' personal and political biases often influence prioritisation. Another suggested criterion was the cost–benefit analysis of implementation, suggesting that decision-makers should weigh the potential benefits of each goal against its implementation cost. The potential for leveraging additional resources, finance, or partnerships, and the minimisation of potential trade-offs were also considered critical considerations. For the suggested sub-criteria, respondents offered a range of thoughtful suggestions. The 'ability to impact' was proposed as a sub-criterion of relevance, especially for sub-national entities such as local governments or companies. They argued that these entities might have limited ability to impact some of the goals in a meaningful way relative to other goals. Therefore, it might make more sense for these entities to prioritise those SDGs where they can achieve a more significant impact per resource invested. Another sub-criterion suggested was political stability. Here we discuss that this factor cannot be considered as a criterion to prioritise SDGs because political stability does not inherently determine the importance or urgency of individual goals. To clarify, political stability might influence the pace or success of SDG implementation, but it does not change the inherent significance of the goals themselves. These suggestions underline the complexity of SDG prioritisation and point towards a multi-faceted approach that considers a wide range of criteria and sub-criteria, acknowledging both practical and strategic factors in the decision-making process.

Despite our efforts to clearly define the terminologies used in our study, we acknowledge that there is a possibility some participants might have their own interpretations of criteria terminologies. This variation in understanding could lead to inconsistencies in how participants evaluate and prioritise factors.

To conclude this discussion, it's crucial to clarify a common misconception: prioritising specific SDGs doesn't mean ignoring the rest. This strategy is about focusing on efforts optimisation. It delineates a clear path towards addressing particular sustainability issues, without diminishing commitment to the entirety of the SDGs. The evidence presented in this study underscores the value of such a focused approach in facilitating progress towards these globally significant goals. It is also important to recognise the potential risks associated with SDG prioritisation. It is crucial to adopt strategies that mitigate power imbalances, corruption, and the neglect of context-specific needs. Inclusive and participatory approaches are essential, engaging local communities, civil society organisations, and other stakeholders in decision-making processes to ensure that prioritisation reflects diverse perspectives and local realities (Georgeson and Maslin 2018). Additionally, transparency and accountability mechanisms, such as open data initiatives and regular audits, can help reduce corruption and ensure that resources are used effectively (OECD 2024).

Conclusion

Prioritising SDGs is crucial for governments and organisations to effectively allocate resources and maximise the impact of their efforts. Numerous efforts have been undertaken to create and implement prioritisation systems for SDGs using a range of quantitative and qualitative approaches. However, to establish a solid basis for developing such a system, it is essential to first identify the influential design drivers. This study makes two key contributions: identifying the factors essential for formulating a prioritisation system and investigating the significance of them from the perspectives of government executives, academics, and industry experts.

This study presents five significant practical implications. (i) The systematic literature review section provides a list of four criteria (Alignment and Relevance, Relationships and Interlinkage, Collaborative Scope, and Current Performance) for decision-makers and policy designers as the key influential factors which should be considered in formulating an effective SDGs prioritisation system. (ii) By providing detailed information on the comparative importance of factors, decision-makers can estimate the weights of driving factors and make informed decisions during the design stage of a prioritisation framework for the SDGs. (iii) The results of this study pinpoint the areas where there is a gap between the viewpoints of government executives and academics regarding the importance level of SDGs design drivers for a prioritisation system, and highlights opportunities for collaborations that can enhance SDGs achievements. (iv) When designing a SDGs prioritisation system, decision-makers should give careful consideration to the current status of goals, targets, and indicators that are off-track, in order to prioritise actions that can effectively address these areas of concern. (v) The divergent opinions of government officials and academics on the relative importance of 'Alignment and Relevance' versus 'Relationships and Interlinkage' highlight the need to carefully filter out irrelevant or less relevant goals, targets, and indicators when implementing a prioritisation system. By prioritising SDGs indicators that are most relevant, have the greatest potential for synergetic effects, and are underperforming, decision-makers can effectively allocate resources and maximise their investment outcome.

Given that the SDGs framework was introduced in September 2015, the articles included in this systematic literature review were collected from the most comprehensive databases between 2015 and 2022, which is expected to cover the relevant years. However, it is worth noting that the field of SDGs research is rapidly evolving, and new studies are being published each year. Therefore, future studies could benefit from including studies published in 2023 and beyond to ensure that the most up-to-date and relevant insights are included in the review. The second limitation of the literature review section is that only backward reference mining was conducted, which means that only studies that had been previously published and cited were included in the review. Therefore, it is recommended that future studies apply both backward and forward reference mining to identify any new and influential SDG prioritisation design drivers.

It is important to note that an essential aspect of this prioritisation process is its capacity to facilitate dialogue and foster inclusivity by providing a structured framework for engagement among diverse stakeholders. This involves actively involving representatives from civil society, the private sector, academia, and local communities, particularly marginalised groups, to ensure that their voices are heard and considered. Ensuring that the prioritisation process is inclusive, transparent, and accountable is crucial to mitigate the risks of power imbalances and to ensure that the process leads to more equitable and effective sustainable development strategies. Moreover, transparency ensures that all stakeholders understand the criteria and rationale behind prioritisation decisions, fostering trust and collaboration. Furthermore, accountability mechanisms should be established to monitor the progress and impact of prioritised actions, allowing for adjustments and improvements over time. Additionally, it is important to recognise that prioritisation is an ongoing process that requires regular review and adaptation. As new challenges and opportunities emerge, the prioritisation system must be flexible enough to incorporate these changes while maintaining its core principles of inclusivity, transparency, and accountability. By continuously involving a broad spectrum of stakeholders and maintaining a commitment to these principles, the prioritisation process can contribute significantly to the successful implementation of the SDGs and the broader goal of sustainable development.

In conclusion, our study primarily addresses the question of "What factors should be considered in a prioritisation system?" rather than delving into "How do we implement them?" By identifying the critical factors for effective prioritisation, our work lays the foundation for subsequent studies that can explore the practical methodologies and frameworks necessary for implementation, ensuring that these factors are applied in a manner that maximises impact and equity.

Data availability

Everything is included in the paper, systematic literature review, demographic of participants and the result. There is no other data.

References

Akenroye TO, Nygård HM, Eyo A (2018) Towards implementation of sustainable development goals (SDG) in developing nations: a useful funding framework. Int Area Stud Rev 21(1):3–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/2233865917743357

Allen C, Nejdawi R, El-Baba J, Hamati K, Metternicht G, Wiedmann T (2017) Indicator-based assessments of progress towards the sustainable development goals (SDGs): a case study from the Arab region. Sustain Sci 12(6):975–989. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-017-0437-1

Allen C, Metternicht G, Wiedmann T (2019a) Prioritising SDG targets: assessing baselines, gaps and interlinkages. Sustain Sci 14(2):421–438. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-018-0596-8

Allen C, Metternicht G, Wiedmann T, Pedercini M (2019b) Greater gains for Australia by tackling all SDGs but the last steps will be the most challenging. Nat Sustain 2(11):1041–1050. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-019-0409-9

Allen C, Reid M, Thwaites J, Glover R, Kestin T (2020) Assessing national progress and priorities for the sustainable development goals (SDGs): experience from Australia. Sustain Sci 15(2):521–538. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-019-00711-x

Al-Saidi M (2022) Disentangling the SDGs agenda in the GCC region: priority targets and core areas for environmental action. Front Environ Sci. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2022.1025337

Aly E, Elsawah S, Ryan MJ (2022) Aligning the achievement of SDGs with long-term sustainability and resilience: an OOBN modelling approach. Environ Model Softw. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsoft.2022.105360

Ament JM, Freeman R, Carbone C, Vassall A, Watts C (2020) An empirical analysis of synergies and tradeoffs between sustainable development goals. Sustainability. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208424

Amer M, Daim TU (2011) Selection of renewable energy technologies for a developing county: a case of Pakistan. Energy Sustain Dev 15(4):420–435. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esd.2011.09.001

Anderson CC, Denich M, Warchold A, Kropp JP, Pradhan P (2022) A systems model of SDG target influence on the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. Sustain Sci 17(4):1459–1472. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-021-01040-8

Antwi-Agyei P, Dougill AJ, Agyekum TP, Stringer LC (2018) Alignment between nationally determined contributions and the sustainable development goals for West Africa. Clim Policy 18(10):1296–1312. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2018.1431199

Asadikia A, Rajabifard A, Kalantari M (2021) Systematic prioritisation of SDGs: machine learning approach. World Dev 140:105269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105269

Asadikia A, Rajabifard A, Kalantari M (2022) Region-income-based prioritisation of sustainable development goals by gradient boosting machine. Sustain Sci 17(5):1939–1957. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-022-01120-3

Asadikia A, Rajabifard A, Kalantari M (2023) A systems perspective on national prioritisation of sustainable development goals: insights from Australia. Geogr Sustain 4(3):255–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geosus.2023.06.003

Baffoe G, Zhou X, Moinuddin M, Somanje AN, Kuriyama A, Mohan G, Takeuchi K et al (2021) Urban–rural linkages: effective solutions for achieving sustainable development in Ghana from an SDG interlinkage perspective. Sustain Sci 16(2004):1341–1362. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-021-00929-8

Bali Swain R, Ranganathan S (2021) Modeling interlinkages between sustainable development goals using network analysis. World Dev 138:105136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105136

Bali Swain R, Yang-Wallentin F, Swain RB, Yang-Wallentin F, Bali Swain R, Yang-Wallentin F (2020) Achieving sustainable development goals: predicaments and strategies. Int J Sust Dev World 27(2):96–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504509.2019.1692316

Bandari R, Moallemi EA, Lester RE, Downie D, Bryan BA (2022) Prioritising sustainable development goals, characterising interactions, and identifying solutions for local sustainability. Environ Sci Policy 127(September):325–336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2021.09.016

Barasa E, Nguhiu P, McIntyre D (2018) Measuring progress towards sustainable development goal 3.8 on universal health coverage in Kenya. BMJ Glob Health. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000904

Barbier EB, Burgess JC (2019) Sustainable development goal indicators: analyzing trade-offs and complementarities. World Dev 122:295–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.05.026

Bennich T, Weitz N, Carlsen H (2020) Deciphering the scientific literature on SDG interactions: a review and reading guide. Sci Total Environ 728:138405. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138405

Berawi MA (2021) Managing cross-sectoral coordination in accelerating the sustainable development agenda. Int J Technol. https://doi.org/10.14716/ijtech.v12i2.4868

Bersaglio B, Enns C, Karmushu R, Luhula M, Awiti A (2021) How development corridors interact with the sustainable development goals in East Africa. Int Dev Plan Rev 43(2):231–256. https://doi.org/10.3828/idpr.2020.7

Bidarbakhtnia A (2020) Measuring sustainable development goals (SDGs): an inclusive approach. Glob Policy 11(1):56–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.12774

Biermann F, Kanie N (2017) Governing through goals: Sustainable Development Goals as governance innovation. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/10894.001.0001

Breu T, Bergoo M, Ebneter L, Pham-Truffert M, Bieri S, Messerli P, Bader C et al (2021) Where to begin? Defining national strategies for implementing the 2030 Agenda: the case of Switzerland. Sustain Sci 16(1):183–201. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-020-00856-0

Çağlar M, Gürler C, Caglar M, Gurler C, Çağlar M, Gürler C, Gurler C et al (2022) Sustainable development goals: a cluster analysis of worldwide countries. Environ Dev Sustain 24(6):8593–8624. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-021-01801-6

Castañeda G, Chávez-Juárez F, Guerrero OA, Castaneda G, Chavez-Juarez F, Guerrero OA, Guerrero OA et al (2018) How do governments determine policy priorities? Studying development strategies through spillover networks. J Econ Behav Organ 154:335–361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2018.07.017

Cernev T, Fenner R (2020) The importance of achieving foundational sustainable development goals in reducing global risk. Futures. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2019.102492

Chan P (2020) Assessing sustainability of the capital and emerging secondary cities of Cambodia based on the 2018 commune database. Data 5(3):1–36. https://doi.org/10.3390/data5030079

Chapman A, Shigetomi Y (2018) Developing national frameworks for inclusive sustainable development incorporating lifestyle factor importance. J Clean Prod 200:39–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.07.302

Chaudhary A, Gustafson D, Mathys A (2018) Multi-indicator sustainability assessment of global food systems. Nat Commun. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-03308-7. (WE-Science Citation Index Expanded (SCI-EXPANDED))

Collste D, Pedercini M, Cornell SE (2017) Policy coherence to achieve the SDGs: using integrated simulation models to assess effective policies. Sustain Sci 12(6):921–931. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-017-0457-x

Dawes JHP, Zhou X, Moinuddin M (2022) System-level consequences of synergies and trade-offs between SDGs: quantitative analysis of interlinkage networks at country level. Sustain Sci 17(4):1435–1457. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-022-01109-y

Dias A, Ioannou PG (1996) Company and project evaluation model for privately promoted infrastructure projects. J Constr Eng Manag-ASCE 122:71–82

Dong Y, Zhang G, Hong WC, Xu Y (2010) Consensus models for AHP group decision making under row geometric mean prioritization method. Decis Support Syst 49(3):281–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2010.03.003

Dörgo G, Sebestyén V, Abonyi J, Dorgo G, Sebestyen V, Abonyi J, Abonyi J et al (2018) Evaluating the interconnectedness of the sustainable development goals based on the causality analysis of sustainability indicators. Sustainability. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10103766

Elavarasan RM, Pugazhendhi R, Shafiullah GM, Kumar NM, Arif MT, Jamal T, Dyduch J et al (2022) Impacts of COVID-19 on sustainable development goals and effective approaches to maneuver them in the post-pandemic environment. Environ Sci Pollut Res 29(23):33957–33987. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-17793-9

Fartash K, Khayatian M, Ghorbani A, Sadabadi A (2021) Interpretive structural analysis of interrelationships of the sustainable development goals (SDGs) in Iran. Int J Sustain Dev Plan 16(1):155–163. https://doi.org/10.18280/ijsdp.160116

Forestier O, Kim RE (2020) Cherry-picking the sustainable development goals: goal prioritization by national governments and implications for global governance. Sustain Dev 28(5):1269–1278. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.2082

Fourie W (2018) Aligning South Africa’s national development plan with the 2030 agenda’s sustainable development goals: guidelines from the policy coherence for development movement. Sustain Dev 26(6):765–771. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.1745

Gao L, Bryan BA (2017) Finding pathways to national-scale land-sector sustainability. Nature 544(7649):217–222. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature21694

Garcia MCF, De Nicolas VLD, Blanco JLY, Fernandez JL, Fariña García MC, De Nicolás De Nicolás VL, Fernández JL et al (2021) Semantic network analysis of sustainable development goals to quantitatively measure their interactions. Environ Dev. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envdev.2020.100589

Georgeson L, Maslin M (2018) Putting the United Nations sustainable development goals into practice: a review of implementation, monitoring, and finance. Geo Geogr Environ. https://doi.org/10.1002/geo2.49

Golden BL, Wasil EA, Harker PT (1989). In: Golden BL, Wasil EA, Harker PT (eds) The analytic hierarchy process. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-50244-6

GRI U (2018) Disclosing how to prioritise the SDGs: examples of corporate reporting practices. Retrieved from https://d306pr3pise04h.cloudfront.net/docs/publications%2FSDG_Reporting_Prioritization_Cemex_Maersk_Nutresa_FINAL.pdf

Guerrero OA, Castañeda G (2020) Policy priority inference: a computational framework to analyze the allocation of resources for the sustainable development goals. Data Policy 2:e17. https://doi.org/10.1017/dap.2020.18

Guerrero OA, Castañeda G, Trujillo G, Hackett L, Chávez-Juárez F (2022) Subnational sustainable development: the role of vertical intergovernmental transfers in reaching multidimensional goals. Socio-Econ Plan Sci. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seps.2021.101155

Han D, Kalantari M, Rajabifard A (2023) Identifying and prioritizing sustainability indicators for China’s assessing demolition waste management using modified Delphi—analytic hierarchy process method. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734242X231166309

Hashim M, Nazam M, Abrar M, Hussain Z, Nazim M, Shabbir R (2021) Unlocking the sustainable production indicators: a novel TESCO based fuzzy AHP approach. Cogent Bus Manag. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2020.1870807

Hazarika R, Jandl R (2019) The nexus between the Austrian Forestry Sector and the sustainable development goals: a review of the interlinkages. Forests 10(3):205. https://doi.org/10.3390/f10030205

Heras-Saizarbitoria I, Urbieta L, Boiral O (2022) Organizations’ engagement with sustainable development goals: from cherry-picking to SDG-washing? Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag 29(2):316–328. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.2202

Horan D (2020) National baselines for integrated implementation of an environmental sustainable development goal assessed in a new integrated SDG index. Sustainability. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12176955

Horn P, Grugel J (2018) The SDGs in middle-income countries: setting or serving domestic development agendas? Evidence from Ecuador. World Dev 109:73–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.04.005

Hosseinpoor AR, Bergen N, Schlotheuber A (2015) Promoting health equity: WHO health inequality monitoring at global and national levels. Glob Health Action 8(1):29034. https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v8.29034

Huan Y, Zhu X (2022) Interactions among sustainable development goal 15 (life on land) and other sustainable development goals: knowledge for identifying global conservation actions. Sustain Dev 31(1):321–333. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.2394

Huan YZ, Liang T, Li HT, Zhang CS (2021) A systematic method for assessing progress of achieving sustainable development goals: a case study of 15 countries. Sci Total Environ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141875

Huan Y, Wang L, Burgman M, Li H, Yu Y, Zhang J, Liang T (2022) A multi-perspective composite assessment framework for prioritizing targets of sustainable development goals. Sustain Dev 30(5):833–847. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.2283

Ionascu E, Mironiuc M, Anghel I, Huian MC, Ionaşcu E, Mironiuc M, Huian MC et al (2020) The involvement of real estate companies in sustainable development—an analysis from the SDGs reporting perspective. Sustainability. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12030798

Jaramillo F, Desormeaux A, Hedlund J, Jawitz J, Clerici N, Piemontese L, Åhlén I et al (2019) Priorities and interactions of sustainable development goals (SDGs) with focus on wetlands. Water 11(3):619. https://doi.org/10.3390/w11030619

Karaşan A, Kahraman C (2018) A novel interval-valued neutrosophic EDAS method: prioritization of the United Nations national sustainable development goals. Soft Comput 22(15):4891–4906. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00500-018-3088-y

Karnib A (2020) Interlinkages between SDG6 and the SDGs: a regional perspective. Desalin Water Treat 176:430. https://doi.org/10.5004/dwt.2020.25555

Khalid AM, Sharma S, Dubey AK (2018) Developing an indicator set for measuring sustainable development in India. Nat Res Forum 42(3):185–200. https://doi.org/10.1111/1477-8947.12151

Klavans R, Boyack KW (2017) Which type of citation analysis generates the most accurate taxonomy of scientific and technical knowledge? J Am Soc Inf Sci 68(4):984–998. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.23734

Koasidis K, Karamaneas A, Kanellou E, Neofytou H, Nikas A, Doukas H (2021) Towards sustainable development and climate co-governance: a multicriteria stakeholders’ perspective, pp 39–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-89277-7_3

Koch F, Krellenberg K, Reuter K, Libbe J, Schleicher K, Krumme K, Kern K et al (2019) How can the sustainable development goals be implemented? Challenges for cities in Germany and the role of urban planning. DisP Plan Rev 55(4):14–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/02513625.2019.1708063

Koff H, Challenger A, Portillo I (2020) Guidelines for operationalizing policy coherence for development (PCD) as a methodology for the design and implementation of sustainable development strategies. Sustainability. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104055

Kolmar O, Sakharov A (2019) Prospects of implementation of the UN SDG in Russia. Int Organ Res J 14(1):189–206. https://doi.org/10.17323/1996-7845-2019-01-11

Kostetckaia M, Hametner M (2022) How sustainable development goals interlinkages influence European Union countries’ progress towards the 2030 agenda. Sustain Dev 30(5):916–926. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.2290

Krajnc D, Glavic P (2005) A model for integrated assessment of sustainable development. Resour Conserv Recycl 43(2):189–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2004.06.002. (WE-Science Citation Index Expanded (SCI-EXPANDED))

Krishna VR, Paramesh V, Arunachalam V, Das B, Elansary HO, Parab A, El-Sheikh MA et al (2020) Assessment of sustainability and priorities for development of Indian West Coast Region: an application of sustainable livelihood security indicators. Sustainability. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208716

Kumar P, Ahmed F, Singh RK, Sinha P (2018) Determination of hierarchical relationships among sustainable development goals using interpretive structural modeling. Environ Dev Sustain 20(5):2119–2137. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-017-9981-1

Kunčič A (2019) Prioritising the sustainable development goals using a network approach: SDG linkages and groups. Teorija in Praksa 56(3 Special Issue);418–437. Retrieved from https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85074700385&partnerID=40&md5=a120cd6a2b9231b71f73c1b43be91d56

Laumann F, von Kugelgen J, Uehara THK, Barahona M (2022) Complex interlinkages, key objectives, and nexuses among the sustainable development goals and climate change: a network analysis. Lancet Planet Health 6(5):E422–E430

Le Blanc D (2015) Towards integration at last? The sustainable development goals as a network of targets. Dep Econ Soc Aff 23(3):176–187. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.1582

Leal Filho W, Vidal DG, Chen C, Petrova M, Dinis MAP, Yang P, Neiva S et al (2022) An assessment of requirements in investments, new technologies, and infrastructures to achieve the SDGs. Environ Sci Europe. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12302-022-00629-9

Lee E-K, Ha S, Kim S-K (2001) Supplier selection and management system considering relationships in supply chain management. IEEE Trans Eng Manag 48(3):307–318. https://doi.org/10.1109/17.946529

Lee AHI, Kang HY, Hsu CF, Hung HC (2009) A green supplier selection model for high-tech industry. Expert Syst Appl 36(4):7917–7927. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2008.11.052. (WE-Science Citation Index Expanded (SCI-EXPANDED))

Leone K, LeSage T (2021) Where to start? A tool for thinking about the SDGs and Community Foundation Work. Found Rev 13(4):46–58. https://doi.org/10.9707/1944-5660.1590

Lim MML, Jorgensen PS, Wyborn CA (2018) Reframing the sustainable development goals to achieve sustainable development in the anthropocene—a systems approach. Ecol Soc. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-10182-230322

Lior N, Radovanović M, Filipović S, Radovanovic M, Filipovic S (2018) Comparing sustainable development measurement based on different priorities: sustainable development goals, economics, and human well-being—Southeast Europe case. Sustain Sci 13(4):973–1000. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-018-0557-2

Lomborg B (2015) The U.N. chose way too many new development goals. Time

Lusseau D, Mancini F (2019) Income-based variation in sustainable development goal interaction networks. Nat Sustain 2(3):242–247. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-019-0231-4

Lyytimäki J, Lonkila K-M, Furman E, Korhonen-Kurki K, Lähteenoja S (2021) Untangling the interactions of sustainability targets: synergies and trade-offs in the Northern European context. Environ Dev Sustain 23(3):3458–3473. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-020-00726-w

Mantlana KB, Maoela MA (2020) Mapping the interlinkages between sustainable development goal 9 and other sustainable development goals: a preliminary exploration. Bus Strateg Dev 3(3):344–355. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsd2.100

Mbanda V, Fourie W (2020) The 2030 Agenda and coherent national development policy: in dialogue with South African policymakers on policy coherence for sustainable development. Sustain Dev 28(4):751–758. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.2025

McArthur JW, Rasmussen K (2019) Classifying sustainable development goal trajectories: a country-level methodology for identifying which issues and people are getting left behind. World Dev 123:104608. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.06.031

McGowan PJKK, Stewart GB, Long G, Grainger MJ (2019) An imperfect vision of indivisibility in the sustainable development goals. Nat Sustain 2(1):43–45. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-018-0190-1

Meho LI, Yang K (2007) Impact of data sources on citation counts and rankings of LIS faculty: web of science versus scopus and google scholar. J Am Soc Inform Sci Technol 58(13):2105–2125. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.20677

Mensah J (2019) Sustainable development: meaning, history, principles, pillars, and implications for human action: literature review. Cogent Soc Sci. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2019.1653531

Miola A, Borchardt S, Neher F, Buscaglia D (2019) Interlinkages and policy coherence for the sustainable development goals implementation: an operational method to identify trade-offs and co-benefits in a systemic way. Luxembourg. https://doi.org/10.2760/472928. (JRC115163)

Moallemi EA, Hosseini SH, Eker S, Gao L, Bertone E, Szetey K, Bryan BA (2022) Eight archetypes of sustainable development goal (SDG) synergies and trade-offs. Earth’s Future. https://doi.org/10.1029/2022EF002873

Mohd Salleh K, Sulaiman NL, Puteh S, Jamaludin MA (2023) Impact of community engagement on sustainable development goals (SDGs): the global goals to local implementation. J Tech Educ Train. https://doi.org/10.30880/jtet.2023.15.03.018

Moyer JD, Bohl DK (2019) Alternative pathways to human development: assessing trade-offs and synergies in achieving the sustainable development goals. Futures 105:199–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2018.10.007