Abstract

Decision-making for patients with stroke in neurocritical care is uniquely challenging because of the gravity and high preference sensitivity of these decisions. Shared decision-making (SDM) is recommended to align decisions with patient values. However, limited evidence exists on the experiences and perceptions of key stakeholders involved in SDM for neurocritical patients with stroke. This review aims to address this gap by providing a comprehensive analysis of the experiences and perspectives of those involved in SDM for neurocritical stroke care to inform best practices in this context. A qualitative meta-synthesis was conducted following the methodological guidelines of the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI), using the thematic synthesis approach outlined by Thomas and Harden. Database searches covered PubMed, CIHAHL, EMBASE, PsycINFO, and Web of Science from inception to July 2023, supplemented by manual searches. After screening, quality appraisal was performed using the JBI Appraisal Checklist. Data analysis comprised line-by-line coding, development of descriptive themes, and creation of analytical themes using NVivo 12 software. The initial search yielded 7,492 articles, with 94 undergoing full-text screening. Eighteen articles from five countries, published between 2010 and 2023, were included in the meta-synthesis. These studies focused on the SDM process, covering life-sustaining treatments (LSTs), palliative care, and end-of-life care, with LST decisions being most common. Four analytical themes, encompassing ten descriptive themes, emerged: prognostic uncertainty, multifaceted balancing act, tripartite role dynamics and information exchange, and influences of sociocultural context. These themes form the basis for a conceptual model offering deeper insights into the essential elements, relationships, and behaviors that characterize SDM in neurocritical care. This meta-synthesis of 18 primary studies offers a higher-order interpretation and an emerging conceptual understanding of SDM in neurocritical care, with implications for practice and further research. The complex role dynamics among SDM stakeholders require careful consideration, highlighting the need for stroke-specific communication strategies. Expanding the evidence base across diverse sociocultural settings is critical to enhance the understanding of SDM in neurocritical patients with stroke.

Trial registration This study is registered with PROSPERO under the registration number CRD42023461608.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A stroke is a sudden neurological deficit or loss of function caused by acute focal injury to the central nervous system, primarily due to cerebrovascular disorders [1]. Globally, stroke remains the third-leading cause of combined death and disability, imposing a substantial burden on individuals, families, and society as a whole [2, 3]. Severe stroke cases often require neurocritical care, wherein comprehensive medical care and specialized neurological support are provided to patients with life-threatening stroke conditions. This is a well-organized subspecialty provided in dedicated units or designated beds within general intensive care units (ICUs) [4].

Decision-making for patients with stroke in the neurocritical phase poses unique challenges. Firstly, there’s considerable uncertainty in forecasting the outcome, ranging from complete recovery to varying degrees of functional impairment [5]. This uncertainty necessitates careful consideration of potential outcomes and their implications. Additionally, patients with stroke in neurocritical care often experience reduced decision-making capacity or challenges in communicating their decision preferences due to impaired consciousness or sedation. Very often, patients and treating health care professions rely on surrogate decision-makers, typically family members, to express decision-making preferences, adding complexity to the process [6, 7]. Moreover, the sudden onset of stroke may leave both the patient and surrogate unprepared for decision-making, leading to heightened stress and emotional burden, further complicating the process [5, 7].

Shared decision-making (SDM) is an increasingly endorsed model for health care decision-making [8]. In critical care, SDM is defined as “a collaborative process that allows patients, or their surrogates, and clinicians to make health care decisions together, taking into account the best scientific evidence available, as well as the patient’s values, goals, and preferences” [9]. According to synthesized guidelines from the World Stroke Organization (WSO), it is recommended that at all levels of stroke services, the management of patients with severe stroke should involve the patient (if possible) and their family in SDM, considering the anticipated prognosis of functional recovery [10]. Guidance from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association (AHA/ASA) and the Neurocritical Care Society (NCS) also underscores the importance of sharing early, timely, and tailored information with critically ill patients with stroke and their surrogates and incorporating their preferences in decisions [11,12,13].

Decision-making for patients with stroke during neurocritical care often pertains to the continuation or limitation of life-sustaining treatments (LSTs), which greatly impact mortality rates [5, 14]. Furthermore, individuals’ subjective evaluation of the acceptability of disability versus death varies widely, making these decisions highly preference sensitive and necessitating a careful approach to SDM [6, 7]. In the context of neurocritical care, SDM involves various stakeholders, including patients, surrogate decision-makers, and health and social care professionals (HSCPs), each facing distinct challenges [5,6,7]. Patients with decision-making capacity may differ in their readiness to receive information and ability to process it amid significant health changes [15, 16]. Family members, often supporting patients’ decision-making capacity or acting as surrogate decision-makers, may endure emotional and physical burdens due to the irreversible consequences of decision outcomes [17, 18]. HSCPs, encompassing a diverse range of professionals such as doctors, nurses, rehabilitators, and social workers, encounter challenges in prognostic communication and conflict resolution, leading to emotional distress when navigating inappropriate decision-making options [19, 20]. Throughout this article, “surrogates” and “families” are used interchangeably to denote those involved in SDM on behalf of the patient.

Understanding the experiences and perspectives of those involved in decision-making in neurocritical stroke care is crucial for elucidating how effectively SDM can facilitate goal-concordant care while alleviating decision-making burdens. However, there is a noticeable gap in systematically synthesizing evidence regarding the experiences and perceptions of key stakeholders in neurocritical care decision-making. This review aims to address this gap by using a qualitative meta-synthesis approach to answer the following question: What are the experiences and perceptions of key stakeholders engaged in SDM for neurocritical patients with stroke? Through a comprehensive exploration of stakeholder experiences, this study seeks to provide some critical insight on the essential elements, relationships, and behaviors influencing the complex phenomenon of SDM in contexts of neurocritical care.

Methods

Design

This review followed the methodological guidelines provided by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) for systematic reviews of qualitative evidence [21]. Additionally, the thematic synthesis approach outlined by Thomas and Harden [22] was employed, emphasizing transparent connections between the review’s findings and primary studies. This study was registered with PROSPERO (registration number: CRD42023461608), and comprehensive reporting was ensured by adhering to the updated Preferred Reporting Items for Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist [23].

Eligibility Criteria

This review included individuals with cerebrovascular-origin ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke, primarily including cerebral infarction, intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH), or subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH). To ensure relevance and comprehensiveness, studies related to neurological disorders that specifically address the stroke population or cover patients with stroke were considered for inclusion. Evidence discussing decision-making scenarios involving HSCPs, patients with stroke, and/or their family or decision-supporters was included to align with the concept of SDM. We included studies exploring the experiences, emotions, viewpoints, and perceived challenges and obstacles encountered by stakeholders during the SDM process. The study context encompassed the neurocritical care phase, typically corresponding to the acute phase of stroke care. Locations varied and included dedicated neurocritical care units or general/medical/surgical ICUs, depending on local practice. This review analyzed qualitative data from various methodologies, including phenomenology, grounded theory, ethnography, and mixed-method studies. Detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria are outlined in Table 1.

Search Strategy

A senior librarian at University College Dublin (DS) guided the development of the search strategy. Following the PICo mnemonic [21] (population, phenomena of interest, and context), three search strings were created. Initially, the keywords were searched in PubMed and CINHAL to identify subject terms and more relevant keywords. Subsequently, searches were conducted across five databases, PubMed, CIHAHL, EMBASE, PsycINFO, and Web of Science, using a combination of subject terms and keywords tailored to each database, with a last search date of August 22, 2023. Additionally, a manual search was performed on Google Scholar and the official websites of relevant international organizations, including WSO, AHA/ASA, NCS, and the International Shared Decision-Making Society, to uncover potentially unsearched and gray literature. Furthermore, during the full-text search phase, the reference lists of included studies were reviewed, and a forward citation search was conducted to identify any additional eligible studies.

Considering the language proficiency of the research team, the included studies were limited to those published in English and Chinese, without restrictions on publication dates. The detailed search strategy and record is provided in Appendix A1.

Selection Process

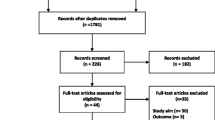

The Covidence software facilitated the selection process [24]. Initially, a team of three reviewers (HZ, DOD, and CD) conducted a pilot screening of 50 documents to ensure a consistent understanding of inclusion criteria based on a shared definition of the target population, phenomenon of interest, and context (see Table 1). Subsequently, HZ screened titles and abstracts, with any uncertainties proceeding to full-text screening. The full texts of all potentially eligible articles were obtained for further assessment. Independent full-text assessments were conducted by HZ and DOD. Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion or consultation with the third reviewer, CD. Reasons for excluding articles during the full-text evaluation were carefully documented in the PRISMA flowchart (Fig. 1) [23].

This flowchart represents the process of literature inclusion following the standard PRISMA format. It provides a clear overview of the data sources and the literature screening steps. A total of 94 articles were screened in full text, with 76 being excluded for not meeting the inclusion criteria. This left 18 articles that were ultimately included in the final meta-synthesis. The flowchart also details the specific reasons for excluding articles during the full-text assessment stage. PRISMA Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses, SDM shared decision-making

Data Extraction

A preliminary data charting form was developed to extract relevant information related to the research question, encompassing details such as author and publication year, country, aims, study design, data collection methods, stroke types, decision options, and main findings (see Table 2). Prior to formal data extraction, three documents were selected for pilot extraction to ensure accuracy. Based on the pilot results, the charting form was revised to enhance clarity and comprehensiveness. Subsequently, HZ conducted data extraction from the included literature, and DOD verified the accuracy of the extracted information.

Quality Appraisal

The JBI Appraisal Checklist for Qualitative Research [25] was employed, comprising ten items that assess methodology, research objectives, data collection, data analysis, findings, researcher’s cultural or theoretical positioning, researcher’s influence, participant representation, ethical considerations, and conclusions. Each item was evaluated, and responses were categorized as “yes,” “no,” “unclear,” or “not applicable.” HZ performed the critical appraisal, and DOD conducted a thorough cross-verification of the assessment results. In cases of discrepancies, CD facilitated discussions and led to a consensus on the assessment outcomes.

Data Synthesis

Thomas and Harden’s thematic synthesis approach involves three steps: initial line-by-line coding, development of descriptive themes, and creation of analytical themes [22]. NVivo 12 software supported the analysis process [26]. Initially, HZ meticulously read and reread each article to gain a comprehensive understanding of the data. The results section of each article was coded line by line. These initial codes were then grouped to form descriptive themes involving the examination of commonalities and disparities among the codes. These descriptive themes were refined through discussions (HZ, DOD, and CD). Subsequently, the descriptive themes were synthesized into analytical themes, aligning with our research goal of exploring the experiences, perceived challenges, and interrelationships of all stakeholders involved in the SDM process. Identification of analytical themes emerged through iterative dialogues among the three researchers, in which theoretical and logical connections between themes were discussed and clarified.

Results

Search Results

The initial search yielded 7,492 articles. After deduplication, 3,590 articles underwent title and abstract screening. Of these, 94 articles underwent full-text screening. Seventy-six articles were excluded for not meeting inclusion criteria, leaving 18 articles for the final meta-synthesis. Refer to Fig. 1 for the search and screening process.

Characteristics of Studies

The included articles originate from five countries, with publication dates spanning 2010 to 2023. Sample sizes varied between 11 and 499 participants. These studies involved patients [16], surrogate decision-makers (referred to as families, family members, relatives, surrogates, or next-of-kin) [17, 18, 27,28,29], and diverse HSCPs, including physicians, intensivists, neurosurgeons, neurologists, stroke consultants, nurses, enrolled nurses, palliative care specialists, physiotherapists, speech and language therapists, and social workers [19, 20, 30,31,32]. Seven studies involved multiple decision-making participants [15, 33,34,35,36,37,38].

Primary decision types included LST (various terms were used, such as “life-prolonging,” “life-supporting,” “life-extending,” or “life-saving”), palliative care, and end-of-life care, with LST being the most prevalent. Treatment options mentioned encompassed admission to the neuro-ICU, hemicraniectomy, resuscitation, tracheal intubation, mechanical ventilation, enteral tube feeding, parenteral fluids, antibiotics, and intermittent pneumatic compression. Two studies specifically focused on tracheotomy and tube feeding [33, 34]. See Table 2 for detailed study information.

Quality Appraisal Results

Overall, the studies provided adequate descriptive data for an evaluation of rigor. Five studies met all criteria [15, 16, 18, 27, 33]. All research adhered to ethical requirements with formal ethical approval or exemption. The research methodology and data collection methods aligned with the stated research questions and objectives. Data analysis was well delineated, often using an iterative approach combining deduction and induction to enhance credibility. Extensive quoting of participants’ statements ensured effective representation of their voices, grounding conclusions in data.

However, a common weakness was the absence of clear philosophical perspectives. Researchers often conducted qualitative studies based solely on interpretive perspectives without explaining their philosophical assumptions, making it challenging to align philosophical outlooks with methodological choices. Explicit cultural or theoretical orientations were also often missing. Moreover, half of the studies did not critically examine the researchers’ roles and potential impacts during data collection and analysis [19, 20, 28, 31, 32, 34,35,36,37]. Despite these shortcomings, all studies were considered eligible for inclusion in the meta-synthesis. An overview of the quality appraisal is presented in Table 3.

Findings

The synthesis revealed four analytical themes encompassing ten descriptive themes, as outlined in Table 4. Each of these themes is described in detail in this article. Furthermore, a conceptual model (Fig. 2) was developed to visually represent the interrelationships among these themes, providing an abstract depiction of the complex phenomenon of SDM in this context.

This conceptual model diagram illustrates the complex dynamics of SDM in neurocritical stroke care. At its base is prognostic uncertainty, which acts as the fulcrum around which other SDM elements revolve. Above this foundation, the three key parties involved in SDM (patient, family, and HSCPs) operate within a broader sociocultural context. Prognostic uncertainty serves as the fulcrum for the balance board, and the difficulty of finding equilibrium depends on the level of uncertainty. As time progresses and prognostic uncertainty decreases, the complexity of this balancing process tends to ease. The model also underscores the complex role dynamics and information exchange among the three SDM parties. The thicker line in the diagram indicates that family members and HSCPs typically have more frequent direct interactions, whereas patients may engage less directly. However, the preferences of patients, whether explicitly stated or inferred, remain central to the decision-making process. These interactions are significantly influenced by the sociocultural context, which impacts the experiences of decision-makers, ultimately affecting the outcomes of SDM. HSCPs health and social care professionals, SDM shared decision-making

Prognostic Uncertainty: Navigating the Unknown

Prognostic Uncertainty Emerges as the Primary Challenge

Thirteen of the 18 articles placed special emphasis on prognostic uncertainty, which was described as the “central challenge,” “most frequently reported concern,” or “a red thread through all the themes” [15, 17,18,19,20, 28, 30, 31, 34,35,36,37,38]. This uncertainty has a fundamental influence on the experience of SDM in neurocritical care, profoundly impacting the decision-making process and behaviors of all involved parties.

HSCPs often hesitate to offer prognostic outcomes because of the complex nature of stroke and concerns about these potential outcomes having an undue influence on decisions [19, 20]. Conversely, families seek prognostic estimates to aid in decision-making and future planning [15, 18]. This disparity in information needs leads to frustration and distress for HSCPs and heightened fear, anxiety, and helplessness for surrogates, despite their acknowledgment of the inherent medical uncertainty [15, 18,19,20, 28, 35, 37]. Given the unpredictability of outcome, some individuals find decision-making to be exceptionally challenging, whereas others feel compelled to proceed with a “just do it” mentality [18, 27, 34]. One study even concluded that “prognostic uncertainty almost transcends the notion of choice” [18].

It’s still really hard to predict what happens from here, and I usually try and say that, you know, some people deteriorate very quickly, some people deteriorate very slowly, some people stabilize and don’t deteriorate particularly. (HSCPs) [35]

It made me anxious. I guess that is probably the best way to describe it. I wanted answers and they really were not able to give me answers. (Families) [28]

Time is Crucial for Resolving Uncertainty

Because of the sudden onset of disease characteristics of stroke, patients and families often feel “shocked, overwhelmed, and emotionally unprepared” [15,16,17, 19, 27, 30]. Consequently, early decision-making is described as “mechanical, passive, and intuitive,” lacking thorough rational considerations [16, 17, 27]. In some cases, discussions about LST decisions occur in advance, particularly for the older population with multiple comorbidities, anticipating potential deterioration in health status. This proactive approach facilitates making early and clear decisions for all SDM participants [27, 33].

However, in most instances, both health care providers and users stress the importance of time, advocating for a cautious approach and advising against rushing into decisions [15, 17, 37, 38]. They recognize that hasty decisions may result in regrettable outcomes. Instead, all involved parties prefer to allow time to serve a supportive role in the decision-making process. They adopt a “wait and see” approach until the minimum acceptable level of recovery becomes evident and the patient’s prognosis is clearer [15, 18, 20, 27, 30, 33, 34]. This approach allows for reassessment and the formulation of new decisions as necessary.

It’s a difficult decision to make, to answer, you need time to think about it, weigh the situation up, and discuss with family members. (HSCPs) [37]

We will give some food and then we will have to wait three days and see how it goes.… And then we can always still say: we will continue feeding, or we stop it. That is also possible. (Families) [33]

Multifaceted Balancing Act: Negotiating Complex Trade-Offs

Balance Between Maintaining Hope and Realism

Hope serves as a crucial coping mechanism, providing faith during desperate times while realistic information helps set reasonable expectations. Families often desired encouraging messages to maintain optimism but were distressed by a lack of honest and forward-looking information, which left them unprepared and led to regrettable decisions [15, 34,35,36,37]. HSCPs grappled with balancing hope and avoiding false hope [19, 20]. In the patient-only study, patients retrospectively wished for realistic information in the early phase; however, they initially wanted positive information favoring functional recovery, even if it was inaccurate, a phenomenon termed the “hope-information paradox” [16]. More importantly, patients and families seek uplifting words to cope with stressful circumstances and resent overly negative messages [16, 18, 28, 34].

I want to know I’m going to get back to a hundred percent;… I think it’s vital to move forward…even if it’s not completely true. (Patients) [16]

I got one doctor that just kept saying “never, none, zero” and that was just upsetting. I just personally don’t feel that those words should ever be used in a medical area. (Families) [28]

Balance Between Participation and Responsibility

Patient and family involvement in SDM varies, with some feeling excluded and others avoiding it because of the high burden. Patients’ and families’ willingness and self-efficacy to participate in SDM differ widely, requiring HSCPs to adapt their roles as facilitators, collaborators, or directors as needed [15, 17, 37]. In neurocritical care, in which decisions often concern life and death, making decisions may be seen as “playing the role of God” and disrupting the course of nature [33]. Families may hesitate to assume the role of decision-maker, preferring to defer to the “expert knowledge” of physicians [17, 29, 33, 35]. This reluctance may stem from a fear of decision-making accountability and responsibility [17, 29]. Given insights from families’ experiences and dilemmas, HSCPs grapple with balancing participation and responsibility. They often strive to ensure families feel engaged in decision-making without bearing sole accountability, balancing this with the risk of being perceived as paternalistic [30, 32].

You are like now making a decision for somebody else. We do not resuscitate you, that means nobody’s gonna try to help you…they already told me there’s no recovery, but it’s still a hard decision to make, say do not bring this person back.… It’s like I’m trying to be God…I don’t want that role. (Families) [18]

When the situation threatens that the family is forced to decide, you should always try to avoid that, people should not get the feeling that they have to decide about the death of their father or husband. We should take those feelings of guilt away, one way or another. Yes, it is our decision; that’s always the trick. (HSCPs) [32]

Balance Between Overtreatment and Premature Withdrawal

Decision-makers face a challenge to balance the intensity of intervention, avoiding both overtreatment and premature withdrawal. Families may express concerns about treatments causing excessive suffering or leaving the patient in an unacceptable state alongside fears of choosing less aggressive measures that may hinder potential recovery [18, 29, 37]. HSCPs share these concerns. They are cautious because of growing awareness of prognostic uncertainty, acknowledging that some patients may recover more extensively than initially predicted. Moreover, the “disability paradox” highlights that certain survivors, despite significant disabilities, express satisfaction with their quality of life. However, HSCPs may also experience moral distress when they perceive patients receiving intervention that they consider inappropriate or unnecessary [15, 20, 30, 31].

The worst part is worrying about her and trying to make decisions about what she would want and the likelihood of her getting back to a life that would be acceptable to her. (Families) [18]

Perhaps the person just has not been allowed to die from an end-of-life event. We are intervening inappropriately to prolong a dying process. (HSCPs) [20]

Tripartite Role Dynamics and Information Exchange

Patients are Often Invisible but Central

Typically, there’s more interaction between family members and HSCPs, with the patient having less direct involvement. Nevertheless, the patient’s preferences and interests remain central to decision-making. Patients with some cognitive capacity may participate directly, whereas those who have diminished decision-making capacity can assert their preferences through preestablished directives, though this is rarely practiced [15, 16, 18, 29, 32, 33, 38].

Frequently, families advocate for patient preferences and make substitute judgments based on their recollections and narratives of the patient’s life stories [18, 27, 29, 30, 32, 33, 38]. Occasionally, patient responses to external stimuli, such as “opening mouth,” “moving hand,” or “pulling out a tube,” are observed to indicate patient preferences and support their involvement in decision-making [15, 27, 28, 33]. Conflicts may be inevitable in some decision-making interactions, arising within health care teams, among family members, and between families and health care teams. In such cases, the patient’s interests should take precedence in conflict resolution [30, 32, 38].

I think [patient] was telling us that by removing the feeding tube and…telling us again by removing the oxygen. (Families) [27]

My task isn’t to please the doctor. I’m speaking for the patient’s best and then there might be conflicts for that reason between me and the doctor because I have a different view…I certainly can fight. (HSCPs, nurse) [30]

Family Members Assume Multiple Roles

Because of the impaired or diminished decision-making capacity of neurocritical patients with stroke, family members assume various roles in the SDM process. They act as “supporters” or “surrogates,” playing an active role in SDM on behalf of the patient. In this capacity, they serve as “informants,” conveying patient preferences, advocating for their best interests, and often engaging with HSCPs as “negotiators” for treatment decisions [15, 32].

Additionally, as families navigate changes and potentially face the loss of a loved one, they are also regarded as “sufferers.” Consequently, they become recipients of care themselves [15, 30, 32]. Furthermore, given their potential role as providers of the patient’s future care, family members may be deeply impacted by the decisions made during the SDM process. Therefore, their involvement may be influenced by their own perspectives and interests, further complicating decision-making [15, 30, 32, 38].

Often the next-of-kin would say, “My mum never wanted to become a vegetable, she has said so explicitly,” and some of them say, “Well, mum is so active she is going to live forever.” (HSCPs) [30]

They will have to recognize themselves [in what is decided]. They are the ones who have to live with the decision to fight [for the patients’ life] or not. (HSCPs) [32]

Effective Information Delivery is Essential

Patients and families expect to receive useful but not overwhelming information, particularly during the acute phase of illness [15, 16, 32, 37]. They find value in receiving information that includes probabilities and scenario descriptions, such as statements like “never get out of bed” or “20%…she will come back” [15]. It is crucial to tailor information to a level that is easily comprehensible; terms such as “pneumology,” “hospice,” and even “stroke” can unintentionally confuse service users [15, 28, 32, 34].

HSCPs report strategies that promote effective communication, such as repeating key statements and conducting conversations in quiet, private spaces [15, 19, 30]. Additionally, computed tomography scans are a simple yet effective method to help patients and families understand the severity of a stroke [19, 32]. Empathetic and compassionate communication is highly valued by patients and families. They recognize and appreciate supportive communication characterized by kindness and patience, emphasizing the importance of HSCPs not merely treating decision-making as a routine task [34, 35, 37]. HSCPs have faced criticism for their condescending and impersonal communication styles, such as referring to patients as numbers [18, 34, 37]. Importantly, all parties stress the need for clear, consistent, and unified information, as anything less can exacerbate the difficulty of an already challenging decision or even directly influence the choice made [19, 28, 30, 34, 35, 38].

So, it is confusing when you are seeing five different people and they are all telling you five different things. (Families) [28]

I can’t stand doctors that talk down to you. They need to come to your level and explain things if you don’t understand them. And not talk over you, not talk around you, like you’re not in the room. (Families) [34]

Sociocultural Context: Shaping Perspectives and Choices

Social and Relational Factors Influence Decision-Making Dynamics

The patient’s care support system is one of the important considerations in decision-making for HSCPs, with strong support often influencing treatment decisions [32, 33]. HSCPs may gather patient information from various sources beyond the hospital setting, such as general practitioners or home care nurses [32]. Additionally, HSCPs value multidisciplinary discussions with colleagues, finding them beneficial in aiding decision-making processes [15, 38].

Frequently, surrogate decision-makers seek advice and support from a broader network of relationships, including family members, relatives, and friends [27, 28, 37, 38]. Observing and comparing the recovery of peer groups can impact patient and family choices regarding treatment, even though such references may not always align with the perspective of HSCPs [15, 16, 19].

If there is someone who knows the patient well and loves him and says, “Well, if he has a chance of 10 percent [of being able to manage a wheelchair and eat without help] then we should go for it,” yes, that’s decisive. (HSCPs) [32]

In a small community, many of them know other stroke survivors who have made very good recoveries - they assume all strokes are the same and expect their family member to also recover. (HSCPs) [19]

Cultural and Religious Factors Impact Preferences and Decisions

Cultural diversity significantly influences treatment preferences among decision-makers from different racial groups, with varying priorities such as valuing individual independence or familial orientation [29]. Individuals from racial minority groups may encounter miscommunication and struggle to establish trust with HSCPs, impacting the SDM process [36].

Religious, spiritual, and faith-based factors also play a significant role in SDM. Patients and family members can find comfort and strength in their faith, aiding them in navigating the challenging decision-making process [15, 18, 36]. However, religious beliefs can sometimes lead individuals to choose certain measures over medical advice, posing challenges for HSCPs involved in the SDM process [15].

Relationships Between Themes

The conceptual model in Fig. 2 illustrates the relationships between the analytical themes. In the realm of neurocritical patients with stroke, the SDM process unfolds as a multifaceted balancing act deeply rooted in prognostic uncertainty. This involves navigating complex role dynamics and information exchange among the tripartite decision-making body, heavily influenced by the broader sociocultural environment.

Prognostic uncertainty emerges as the primary challenge shaping the trajectory of the SDM process. In the conceptual model, it acts as the fulcrum around which other SDM elements revolve. Given the unpredictable nature of prognosis, time becomes critical in resolving uncertainty and reaching conclusive decisions. Decision-makers navigate challenging trade-offs on a balance board, with prognostic uncertainty as the central pivot. As time progresses and prognostic uncertainty decreases, the complexity of this balancing process may ease.

The SDM process features intricate role dynamics and information exchange among the tripartite decision-makers. Family members and HSCPs interact more directly, depicted by the thicker black line in Fig. 2, whereas patients may have fewer direct interactions but remain central to the decision-making process through their expressed or inferred preferences. Because of the impaired or lost decision-making capacity of neurocritical patients with stroke, family members are actively involved in the SDM process, often assuming multiple roles. The way information is exchanged holds significant importance, frequently having a greater impact on decision-makers’ experiences than the content of the information itself.

These dynamic interactions occur within a broader sociocultural context, comprising factors such as social, relational, cultural, and religious influences. These factors have direct or indirect effects on the experiences of decision-makers and ultimately shape the final outcomes of the SDM process.

Discussion

This qualitative meta-synthesis is the first to present a conceptual model that illuminates the key elements, relationships, and behaviors influencing SDM in neurocritical care for patients with stroke. The model is based on a systematic synthesis of 18 studies focused on the experiences and perspectives of patients, families, and HSCPs involved in SDM for patients with stroke in neurocritical care. Using a thematic synthesis approach, the study identified four intersecting analytical themes that encapsulate the essence of SDM in this context. These findings align with prior qualitative meta-syntheses on surrogate decision-makers and palliative/end-of-life care in stroke, in which prognosis uncertainty and cohesive communication are similar themes [39, 40]. However, the present study provides additional insights into participants’ role dynamics, multifaceted balancing processes, and the influence of contextual factors.

In this study, prognostic uncertainty was recognized as the key driver shaping the experience of SDM. For neurocritically ill patients, including those with stroke, prognostic uncertainty is well documented, with outcomes ranging from potential full recovery to mortality [39, 41]. Uncertain prognoses complicate the decision-making process significantly and can lead some decision-makers to believe that discussing options is impractical [18, 27, 34]. This hinders efforts to improve the SDM process. Thus, allowing time to play a crucial role is essential for decision-makers to adapt, accept, and make more deliberated decisions based on a clearer prognosis. All parties in the included studies endorsed time as a valuable buffer and support mechanism for SDM [15, 17, 32, 34]. This aligns with professional recommendations for a time-limited observation period to improve prognosis accuracy, given that most stroke-related deaths occur after withholding or withdrawing LST [11, 13]. Consequently, SDM in neurocritical care is not solely about reaching an immediate decision but rather is a process that supports families and patients in adapting, reflecting, and grieving [18, 34]. Over time, repeated conversations can occur based on the patient’s evolving condition and the changing perspectives of the decision-makers.

Effective information exchange is central to SDM [37]. The findings of this synthesis align with research on general critically ill patients regarding the need for consistent, respectful, and understandable information delivery [40, 42]. However, in neurocritical care settings, where considerable prognostic uncertainty prevails, more skillful information delivery strategies are required [5, 41]. Balancing the need for hope as a coping mechanism with avoiding unrealistic expectations is a delicate and challenging task [43]. To address the “hope-information paradox,” various communication strategies used in oncology have been proposed as potential solutions. These include methods such as the “ask-tell-ask” approach, in which HSCPs ask patients about their understanding, provide information, and then ask again to ensure comprehension [44]. Additionally, strategies such as the “hope for the best, plan for the worst” approach aim to balance optimism with realistic planning. “I wish” statements are used to express empathy and acknowledge the patient’s emotional experience during difficult conversations [45, 46]. However, their applicability to stroke remains unclear because of different disease trajectories, necessitating further research.

In SDM, incorporating patient preferences is essential. This study discovered that SDM participants validate the preferences of patients with diminished decision-making capacity through various methods, including advance directives (ADs), reconstructing the patient’s wishes, and observing their responses to stimuli, with ADs being prioritized. Some surrogates find reassurance when ADs are clearly documented, viewing them as authoritative guidance during overwhelming times [15, 33]. However, ADs are often unavailable, and when they are available, they may not align with the patient’s current clinical situation [18, 29, 32, 38]. This is consistent with the findings of quantitative studies conducted in neurocritical care settings where ADs accessibility was low and had little discernible influence on the choice of treatment regimen, especially in formal documentation [47,48,49]. To address these challenges, stroke-specific ADs have been developed [50]. However, as Morrison [51] noted, health care decisions are not simple, logical, or linear; they are complex, uncertain, emotionally charged, and subject to rapid change as the clinical situation evolves. Therefore, the emphasis should be on discussions on the conditions under which life is deemed worth living and collaborative assessment and deliberation among stakeholders at the moment of decision-making [48, 49].

This study described how key stakeholders perceive each other’s roles and their interactions in the SDM process, highlighting the multiple roles of family members. Although ADs, substituted judgment, and patient’s best interests are theoretically or legally valid standards for surrogate decision-making [52], family surrogates are inevitably influenced by their own cognitive and emotional factors, sometimes incorporating self-interest into their decisions [53, 54]. This can lead to irrational decisions not in the patient’s best interests, adding challenges for HSCPs. Additionally, family surrogates may face family vicissitudes and require care themselves [32, 55]. Thus, driven by clinical morality, HSCPs strive to provide support while balancing participation and responsibility to alleviate the emotional burden of decision-making on families [30, 32]. Researchers emphasized the importance of careful trade-offs when addressing the multiple roles of family members in SDM [15, 30, 32, 33, 47]; however, there is limited research on role dynamics among stakeholders in neurocritical care SDM, prompting further exploration.

The included studies revealed the significant role of religious and cultural factors in decision-making [15, 18, 29, 36]. On the positive side, patients and families often draw strength and hope from their religious faith. However, these beliefs can also lead to differences of opinion among those involved in SDM [15, 18]. In a review of LST in patients with disorders of consciousness, the authors highlight that religious beliefs provide both support and a source of conflict [56]. Regional and racial variations in LST practices and palliative care have also been observed in previous studies [57, 58]. Understanding the impact of sociocultural contexts is crucial to promote mutual understanding and prevent conflicts in SDM. It is worth noting that all 18 studies in this review are from Europe and the United States, indicating cultural homogeneity in the current research landscape. Compared to Western countries, the typical cultural characteristics of Confucianism, such as “familism” and “filial piety,” may significantly influence stakeholders’ behavior, resulting in distinct SDM patterns [59]. In addition, economic conditions, accessibility of health resources, and legislative and regulatory factors can significantly impact the decision-making process [60, 61]. Therefore, there is an urgent need for further research in socioculturally diverse settings to enrich the evidence on SDM in neurocritical patients with stroke.

This review has several limitations. Firstly, this study synthesized primary qualitative research through a rigorous process, but it does acknowledge there is a level of interpretation within both the primary and the synthesized findings. Secondly, the process was not conducted entirely in parallel by research team members, despite efforts to minimize potential bias through pilot methods and multiple rounds of team checks and discussions. Thirdly, language limitations within the research team constrained the literature search to English and Chinese, potentially overlooking valuable relevant literature published in other languages. Lastly, as discussed earlier, all included articles were from Europe and the United States, which may limit their applicability to sociocultural contexts outside these regions.

Conclusions

For neurocritical patients with stroke, the SDM process is a complex balancing act heavily influenced by prognostic uncertainty. This process involves managing intricate role dynamics and facilitating information exchange among a tripartite decision-making body, all while being shaped by a broader sociocultural environment. Further research on stroke-specific communication strategies is urgently needed, particularly regarding the delivery of prognostic information. The complex role dynamics among SDM stakeholders, especially the multiple roles of family members, demand careful attention. The conceptual model developed from this review offers a valuable theoretical framework for researchers to further explore and understand SDM in neurocritical care settings. We recommend using this model as a foundation for additional empirical studies to build a more robust evidence base, particularly in diverse sociocultural contexts.

References

Sacco RL, Kasner SE, Broderick JP, et al. An updated definition of stroke for the 21st century: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2013;44(7):2064–89.

Tsao CW, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2022 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2022;145(8):e153–639.

Feigin VL, Stark BA, Johnson CO, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of stroke and its risk factors, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Neurol. 2021;20(10):795–820.

Busl KM, Bleck TP, Varelas PN. Neurocritical care outcomes, research, and technology: a review. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76(5):612–8.

Goostrey K, Muehlschlegel S. Prognostication and shared decision making in neurocritical care. BMJ. 2022;377:e060154.

Visvanathan A, Dennis M, Mead G, Whiteley WN, Lawton J, Doubal FN. Shared decision making after severe stroke—How can we improve patient and family involvement in treatment decisions? Int J Stroke. 2017;12(9):920–2. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747493017730746.

Cai X, Robinson J, Muehlschlegel S, et al. Patient preferences and surrogate decision making in neuroscience intensive care units. Neurocrit Care. 2015;23:131–41.

Aoki Y, Yaju Y, Utsumi T, et al. Shared decision-making interventions for people with mental health conditions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007297.pub3.

Kon AA, Davidson JE, Morrison W, Danis M, White DB. Shared decision-making in intensive care units. Executive summary of the American college of critical care medicine and American thoracic society policy statement. Am Thoracic Soc. 2016;193:1334–6.

Mead GE, Sposato LA, Sampaio Silva G, et al. A systematic review and synthesis of global stroke guidelines on behalf of the World Stroke Organization. Int J Stroke. 2023;18(5):499–531.

Greenberg SM, Ziai WC, Cordonnier C, et al. 2022 Guideline for the management of patients with spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: a guideline from the American heart association/American stroke association. Stroke. 2022;53(7):e282–361.

Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, et al. Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: 2019 update to the 2018 guidelines for the early management of acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2019;50(12):e344–418.

Souter MJ, Blissitt PA, Blosser S, et al. Recommendations for the critical care management of devastating brain injury: prognostication, psychosocial, and ethical management: a position statement for healthcare professionals from the neurocritical care society. Neurocrit Care. 2015;23:4–13.

Holloway RG, Benesch CG, Burgin WS, Zentner JB. Prognosis and decision making in severe stroke. JAMA. 2005;294(6):725–33.

Göcking B, Biller-Andorno N, Brandi G, Gloeckler S, Glässel A. Aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage and clinical decision-making: a qualitative pilot study exploring perspectives of those directly affected, their next of kin, and treating clinicians. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(4):3187.

Visvanathan A, Mead G, Dennis M, Whiteley W, Doubal F, Lawton J. Maintaining hope after a disabling stroke: a longitudinal qualitative study of patients’ experiences, views, information needs and approaches towards making treatment decisions. PLoS One. 2019;14(9):e0222500–e0222500.

de Boer ME, Depla MFIA, Wojtkowiak J, et al. Life-and-death decision-making in the acute phase after a severe stroke: interviews with relatives. Palliat Med. 2015;29(5):451–7.

Goss AL, Voumard RR, Engelberg RA, Curtis JR, Creutzfeldt CJ. Do they have a choice? Surrogate decision-making after severe acute brain injury. Crit Care Med. 2023;51(7):924–35.

Doubal F, Cowey E, Bailey F, et al. The key challenges of discussing end-of-life stroke care with patients and families: a mixed-methods electronic survey of hospital and community healthcare professionals. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2018;48(3):217–24.

Mc Lernon S, Werring D, Terry L. Clinicians’ perceptions of the appropriateness of neurocritical care for patients with spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH): a qualitative study. Neurocrit Care. 2021;35(1):162–71.

Aromataris E, Munn Z (Editors). JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis [Internet]. JBI 2020. Available at: https://jbi-global-wiki.refined.site/space/MANUAL

Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8(1):1–10.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int J Surg. 2021;88: 105906.

Covidence systematic review software, Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia. Available at www.covidence.org.

Lockwood C, Munn Z, Porritt K. Qualitative research synthesis: methodological guidance for systematic reviewers utilizing meta-aggregation. JBI Evid Implement. 2015;13(3):179–87.

NVivo qualitative data analysis software, QSR International Pty Ltd. Version 12, 2018.

Visvanathan A, Mead GE, Dennis M, Whiteley WN, Doubal FN, Lawton J. The considerations, experiences and support needs of family members making treatment decisions for patients admitted with major stroke: a qualitative study. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2020;20(1):98–98.

Zahuranec DB, Anspach RR, Roney ME, et al. Surrogate decision makers’ perspectives on family members’ prognosis after intracerebral hemorrhage. J Palliat Med. 2018;21(7):956–62.

Lank RJ, Morgenstern LB, Ortiz C, Case E, Zahuranec DB. Barriers to surrogate application of patient values in medical decisions in acute stroke: qualitative study in a biethnic community. Neurocritical Care. 2023;40(1):1–10.

Rejnö Å, Berg L, Danielson E, et al. Ethical problems: In the face of sudden and unexpected death. Nurs Ethics. 2012;19(5):642–53.

Tolsa L, Jones L, Michel P, Borasio GD, Jox RJ, Rutz VR. ‘We have guidelines, but we can also be artists’: neurologists discuss prognostic uncertainty, cognitive biases, and scoring tools. Brain Sci. 2022;12(11):1591.

Seeber AA, Pols AJ, Hija A, Willems DL. How Dutch neurologists involve families of critically ill patients in end-of-life care and decision-making. Neurol Clin Pract. 2015;5(1):50–7.

Frey I, De Boer ME, Dronkert L, et al. Between choice, necessity, and comfort: deciding on tube feeding in the acute phase after a severe stroke. Qual Health Res. 2020;30(7):1114–24.

Lou W, Granstein JH, Wabl R, Singh A, Wahlster S, Creutzfeldt CJ. Taking a chance to recover: families look back on the decision to pursue tracheostomy after severe acute brain injury. Neurocrit Care. 2022;36(2):504–10.

Kendall MMAP, Boyd KP, Murray SAMD, et al. Outcomes, experiences and palliative care in major stroke: a multicentre, mixed-method, longitudinal study. Can Med Assoc J. 2018;190(9):E238–46.

Kiker WA, Rutz Voumard R, Andrews LIB, et al. Assessment of discordance between physicians and family members regarding prognosis in patients with severe acute brain injury. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(10):e2128991–e2128991.

Payne S, Burton C, Addington-Hall J, Jones A. End-of-life issues in acute stroke care: a qualitative study of the experiences and preferences of patients and families. Palliat Med. 2010;24(2):146–53.

Tran LN, Back AL, Creutzfeldt CJ. Palliative care consultations in the neuro-ICU: a qualitative study. Neurocrit Care. 2016;25(2):266–72.

Connolly T, Coats H, DeSanto K, Jones J. The experience of uncertainty for patients, families and healthcare providers in post-stroke palliative and end-of-life care: a qualitative meta-synthesis. Age Ageing. 2021;50(2):534–45.

Su Y, Yuki M, Hirayama K. The experiences and perspectives of family surrogate decision-makers: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Patient Educ Couns. 2020;103(6):1070–81.

Fleming V, Muehlschlegel S. Neuroprognostication. Crit Care Clin. 2023;39(1):139–52.

Boyd EA, Lo B, Evans LR, et al. “It’s not just what the doctor tells me:” factors that influence surrogate decision-makers’ perceptions of prognosis. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(5):1270.

Clayton JM, Hancock K, Parker S, et al. Sustaining hope when communicating with terminally ill patients and their families: a systematic review. Psycho-Oncol J Psychol Soc Behav Dimens Cancer. 2008;17(7):641–59.

Back AL, Arnold RM, Quill TE. Hope for the best, and prepare for the worst. Am College Phys. 2003;138:439–43.

Campbell TC, Carey EC, Jackson VA, et al. Discussing prognosis: balancing hope and realism. Cancer J. 2010;16(5):461–6.

Quill TE, Arnold RM, Platt F. “I wish things were different”: expressing wishes in response to loss, futility, and unrealistic hopes. Am College Phys. 2001;135:551–5.

De Kort FAS, Geurts M, de Kort PLM, et al. Advance directives, proxy opinions, and treatment restrictions in patients with severe stroke. BMC Palliat Care. 2017;16:1–6.

Lank RJ, Shafie-Khorassani F, Zhang X, et al. Advance care planning and transitions to comfort measures after stroke. J Palliat Med. 2021;24(8):1191–6.

Stachulski F, Siegerink B, Bösel J. Dying in the neurointensive care unit after withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy: associations of advance directives and health-care proxies with timing and treatment intensity. J Intensive Care Med. 2021;36(4):451–8.

McGehrin K, Spokoyny I, Meyer BC, Agrawal K. The COAST stroke advance directive: A novel approach to preserving patient autonomy. Neurol Clin Pract. 2018;8(6):521–6.

Morrison RS. Advance directives/care planning: clear, simple, and wrong. J Palliat Med. 2020;23(7):878–9.

Buchanan A, Brock DW. Deciding for others. Death, dying and the ending of life, Vol I and II 2019:205-282

Ho A. Relational autonomy or undue pressure? Family’s role in medical decision-making. Scand J Caring Sci. 2008;22(1):128–35.

Trees AR, Ohs JE, Murray MC. Family communication about end-of-life decisions and the enactment of the decision-maker role. Behav Sci. 2017;7(2):36.

Wendler D, Rid A. Systematic review: the effect on surrogates of making treatment decisions for others. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154(5):336–46.

Lissak IA, Young MJ. Limitation of life sustaining therapy in disorders of consciousness: ethics and practice. Brain. 2024;147(7):2274–88.

Avidan A, Sprung CL, Schefold JC, et al. Variations in end-of-life practices in intensive care units worldwide (Ethicus-2): a prospective observational study. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9(10):1101–10.

Singh T, Peters SR, Tirschwell DL, Creutzfeldt CJ. Palliative care for hospitalized patients with stroke: results from the 2010 to 2012 national inpatient sample. Stroke. 2017;48(9):2534–40.

Badanta B, González-Cano-Caballero M, Suárez-Reina P, Lucchetti G, de Diego-Cordero R. How does confucianism influence health behaviors, health outcomes and medical decisions? A scoping review. J Relig Health. 2022;61(4):2679–725.

Raposo VL. Lost in ‘Culturation’: medical informed consent in China (from a Western perspective). Med Health Care Philos. 2019;22(1):17–30.

Lewis A. International variability in the diagnosis and management of disorders of consciousness. La Presse Médicale. 2023;52(2): 104162.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by the IReL Consortium. This study was funded by the 2023 Jining City Key R&D Program (Soft Science Project) (2023JNZC163).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors made substantial intellectual and practical contributions to this study. HZ, DOD, CD, and DS collaborated on the review’s conception. HZ, DOD, CD, and DS participated in formulating the search strategy. HZ and DS performed the literature search. HZ and DOD conducted the literature screening and quality assessment. HZ conducted the primary meta-synthesis, validated by DOD. All authors engaged in extensive discussions, refinement, and analysis validation. HZ drafted the initial manuscript, and DOD and CD reviewed and made revisions. All authors reached a consensus on the final manuscript for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Keywords used in each string.

Population | AND | Phenomena of Interest | AND | Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Stroke* | Shared Decision Making | Neurocritical Care | ||

OR | OR | OR | ||

Cerebral Infarction* | Decision mak* | Intensive care | ||

OR | OR | OR | ||

Brain Infarction* | Decision Support* | Critical care | ||

OR | OR | OR | ||

Cerebral Hemorrhage* | Decision Aid* | Acute phase* | ||

OR | OR | OR | ||

Cerebral Haemorrhage* | Preference* | Acute Care* | ||

OR | OR | OR | ||

Intracerebral Hemorrhage* | Choice* | Acute stroke care* | ||

OR | OR | OR | ||

Intracerebral Haemorrhage* | Participation | ICU | ||

OR | OR | OR | ||

Brain Hemorrhage* | Surrogate* | HDU | ||

OR | OR | OR | ||

Brain Haemorrhage* | goal of care* | Higher Dependen* | ||

OR | OR | OR | ||

Subarachnoid Hemorrhage* | goals of care* | Palliative care | ||

OR | OR | OR | ||

Subarachnoid Haemorrhage* | goal-setting | Terminal care | ||

OR | OR | OR | ||

Cerebrovascular Accident* | uncertainty | Life support Care | ||

OR | ||||

Cerebrovascular Disorder* | ||||

OR | ||||

Acute brain injur* |

Search record.

PubMed: 22.08.23.

# | Query | Results |

|---|---|---|

#1 | "Stroke"[Mesh] OR "Cerebral Infarction"[Mesh] OR "Cerebral Hemorrhage"[Mesh] OR "Subarachnoid Hemorrhage"[Mesh] OR Stroke* OR “Cerebral Infarction*” OR “Brain Infarction*” OR “Cerebral Hemorrhage*” OR “Cerebral Haemorrhage*” OR “Intracerebral Hemorrhage*” OR “Intracerebral Haemorrhage*” OR “Intracranial Hemorrhage*” OR “Intracranial Haemorrhage*” OR “Brain Hemorrhage*” OR “Brain Haemorrhage*” OR “Subarachnoid Hemorrhage” OR “Subarachnoid Haemorrhage” OR “Cerebrovascular Accident*” OR “Cerebrovascular Disorder*”OR “acute brain injur*” | 538,724 |

#2 | "Decision Making"[Mesh] OR "Decision Support Techniques"[Mesh] OR "Patient Participation"[Mesh] OR "Patient Preference"[Mesh] OR “shared decision making” OR “decision mak*” OR “Decision Support*” OR “Decision Aid*” OR “Surrogate*” OR “preference*” OR Choice* OR “participation” OR “goal of care” OR “goals of care*” OR goal-setting OR uncertainty | 1,387,629 |

#3 | "Critical Care"[Mesh] OR "Intensive Care Units"[Mesh] OR ("Life Support Care"[Mesh:NoExp]) OR "Terminal Care"[Mesh] OR "Palliative Care"[Mesh] OR “Neurocritical Care*” OR “Critical care*” OR “intensive care*” OR “Acute phase*” OR “Acute Care*” OR “acute stroke care” OR ICU OR HDU OR “Higher Dependen*” OR “Palliative care*” OR “life support care*” OR “terminal care*” | 783,512 |

#4 | #1 AND #2 AND #3 | 2,190 |

#5 | Filters: Chinese, English | 2,080 |

CINAHL: 22.08.23.

# | Query | Results |

|---|---|---|

S1 | (MH "Stroke") OR (MH "Intracranial Hemorrhage") OR Stroke* OR “Cerebral Infarction*” OR “Brain Infarction*” OR “Cerebral Hemorrhage*” OR “Cerebral Haemorrhage*” OR “Intracerebral Hemorrhage*” OR “Intracerebral Haemorrhage*” OR “Intracranial Hemorrhage*” OR “Intracranial Haemorrhage*” OR “Brain Hemorrhage*” OR “Brain Haemorrhage*” OR “Subarachnoid Hemorrhage” OR “Subarachnoid Haemorrhage” OR “Cerebrovascular Accident*” OR “Cerebrovascular Disorder*” OR “acute brain injur*” | 164,626 |

S2 | (MH "Decision Making") OR (MH "Goal-Setting") OR (MH "Patient Preference") OR “shared decision making” OR “decision mak*” OR “Decision Support*” OR “Decision Aid*” OR “Surrogate*” OR “preference*” OR Choice* OR “participation” OR “goal of care” OR “goals of care*” OR goal-setting OR uncertainty | 463,024 |

S3 | (MH "Critical Care") OR (MH "Acute Care") OR (MH "Life Support Care") OR (MH "Terminal Care") OR (MH "Palliative Care”) OR “Neurocritical Care*” OR “Critical care*” OR “intensive care*” OR “Acute phase*” OR “Acute Care*” OR “acute stroke care” OR ICU OR HDU OR “Higher Dependen*” OR “Palliative care*” OR “life support care*” OR “terminal care*” | 253,971 |

S4 | S1 AND S2 AND S3 | 648 |

S5 | Narrow by Language: English and Chinese | 632 |

EMBASE: 22.08.23.

# | Query | Result |

|---|---|---|

#1 | 'cerebrovascular accident'/exp OR 'brain infarction'/exp OR 'brain hemorrhage'/exp OR 'subarachnoid hemorrhage'/exp OR Stroke* OR “Cerebral Infarction*” OR “Brain Infarction*” OR “Cerebral Hemorrhage*” OR “Cerebral Haemorrhage*” OR “Intracerebral Hemorrhage*” OR “Intracerebral Haemorrhage*” OR “Intracranial Hemorrhage*” OR “Intracranial Haemorrhage*” OR “Brain Hemorrhage*” OR “Brain Haemorrhage*” OR “Subarachnoid Hemorrhage” OR “Subarachnoid Haemorrhage” OR “Cerebrovascular Accident*” OR “Cerebrovascular Disorder*” OR “acute brain injur*” | 854,618 |

#2 | 'shared decision making'/exp OR 'decision support system'/exp OR 'patient participation'/exp OR 'patient preference'/exp OR “shared decision making” OR “decision mak*” OR “Decision Support*” OR “Decision Aid*” OR “Surrogate*” OR “preference*” OR Choice* OR “participation” OR “goal of care” OR “goals of care*” OR goal-setting OR uncertainty | 1,780,557 |

#3 | 'intensive care unit'/exp OR 'intensive care'/exp OR 'terminal care'/exp OR “Neurocritical Care*” OR “Critical care*” OR “intensive care*” OR “Acute phase*” OR “Acute Care*” OR “acute stroke care” OR ICU OR HDU OR “Higher Dependen*” OR “Palliative care*” OR “life support care*” OR “terminal care*” | 1,813,821 |

#4 | #1 AND #2 AND #3 | 7,490 |

#5 | [embase]/lim NOT ([embase]/lim AND [medline]/lim) | 3,511 |

#6 | ([chinese]/lim OR [english]/lim) | 3,403 |

PsycINFO: 22.08.23.

# | Query | Result |

|---|---|---|

S1 | DE "Cerebrovascular Accidents" OR DE "Cerebral Infarction" OR DE "Cerebral Hemorrhage" OR DE "Subarachnoid Hemorrhage" OR Stroke* OR “Cerebral Infarction*” OR “Brain Infarction*” OR “Cerebral Hemorrhage*” OR “Cerebral Haemorrhage*” OR “Intracerebral Hemorrhage*” OR “Intracerebral Haemorrhage*” OR “Intracranial Hemorrhage*” OR “Intracranial Haemorrhage*” OR “Brain Hemorrhage*” OR “Brain Haemorrhage*” OR “Subarachnoid Hemorrhage” OR “Subarachnoid Haemorrhage” OR “Cerebrovascular Accident*” OR “Cerebrovascular Disorder*”OR “acute brain injur*” | 55,628 |

S2 | DE "Decision Making" OR DE "Decision Support Systems" OR DE "Client Participation" OR DE "Uncertainty" OR “shared decision making” OR “decision mak*” OR “Decision Support*” OR “Decision Aid*” OR “Surrogate*” OR “preference*” OR Choice* OR “participation” OR “goal of care” OR “goals of care*” OR goal-setting OR uncertainty | 569,050 |

S3 | DE "Intensive Care" OR DE "Critical Period" OR DE "Palliative Care" OR “Neurocritical Care*” OR “Critical care*” OR “intensive care*” OR “Acute phase*” OR “Acute Care*” OR “acute stroke care” OR ICU OR HDU OR “Higher Dependen*” OR “Palliative care*” OR “life support care*” OR “terminal care*” | 55,552 |

S4 | S1 AND S2 AND S3 | 244 |

S5 | Narrow by Language: English | 236 |

Web of Science: 22.08.23.

# | Query | Results |

|---|---|---|

#1 | Stroke* OR “Cerebral Infarction*” OR “Brain Infarction*” OR “Cerebral Hemorrhage*” OR “Cerebral Haemorrhage*” OR “Intracerebral Hemorrhage*” OR “Intracerebral Haemorrhage*” OR “Intracranial Hemorrhage*” OR “Intracranial Haemorrhage*” OR “Brain Hemorrhage*” OR “Brain Haemorrhage*” OR “Subarachnoid Hemorrhage” OR “Subarachnoid Haemorrhage” OR “Cerebrovascular Accident*” OR “Cerebrovascular Disorder*” OR “acute brain injur*” | 506,653 |

#2 | “shared decision making” OR “decision mak*” OR “Decision Support*” OR “Decision Aid*” OR “Surrogate*” OR “preference*” OR Choice* OR “participation” OR “goal of care” OR “goals of care*” OR goal-setting OR uncertainty | 2,826,611 |

#3 | “Neurocritical Care*” OR “Critical care*” OR “intensive care*” OR “Acute phase*” OR “Acute Care*” OR “acute stroke care” OR ICU OR HDU OR “Higher Dependen*” OR “Palliative care*” OR “life support care*” OR “terminal care*” | 384,347 |

#4 | #1 AND #2 AND #3 | 1,199 |

#5 | #1 AND #2 AND #3 and English (Languages) | 1,141 |

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, H., Davies, C., Stokes, D. et al. Shared Decision-Making for Patients with Stroke in Neurocritical Care: A Qualitative Meta-Synthesis. Neurocrit Care (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12028-024-02106-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12028-024-02106-y