Abstract

Stress changes the food preferences of individuals, causing an increase in the intake of sweet food, and consequently, the total energy. Stress also leads to a short-term reduction in the appetite. These two contrary scenarios result in nutritional problems in the affected population. In this context, a validity and reliability study was conducted for the Salzburg Stress Eating Scale (SSES) adapted for children and adolescents and presented here. The study was designed as a methodological, descriptive, and correlational study, conducted with 9–18-year-old students (n = 257). A socio-demographic information form and the SSES were used for data collection. The collected data were evaluated based on factor analysis, discriminatory power, McDonald’s omega, Cronbach’s alpha, and the item–total score. The contribution of the ten-item scale to total variance was determined to be 48.869%. The factor loadings of the scale determined based on the exploratory factor analysis and the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) were above 0.30. The fit indices were found to be well matched and the questionnaire had a one-factor structure. The McDonald’s omega and Cronbach’s alpha values determined for the scale were 0.884 and 0.881, respectively. The correlation analysis of the items with the scale’s total score revealed values ranging between 0.470 and 0.757. Accordingly, it was concluded that the SSES was a valid and reliable measurement tool for Turkish-speaking students in the 9–18 age group. Therefore, the SSES is applicable for the assessment of stress eating among children and adolescents aged 9–18 in the general population. It is recommended to adapt the scale in different cultures to determine the level of direct stress eating in children and adolescents and the affecting factors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Stress is defined as a condition of strain exceeding the individual’s physical and psychological limits, which arises due to the negative emotions he/she experiences while adapting to his/her environment (Oral & Ersan, 2017). The concept of stress is not relevant and confined to just the adult population (Wible, 2013), and children and adolescents also experience stress similar to adults (Thompson, 2014). According to the literature, stress weakens the ability of children to concentrate, remember the desired things, control their thoughts, and focus (Thompson, 2014), thereby adversely impacting the healthy brain development and cognitive development in the affected children (Middlebrooks & Audage, 2008; Levitt, 2015). Stress also impacts nutrition in the affected population, and this may be viewed from both individual and situational aspects. Food intake may increase or decrease due to stress (Gibson, 2006; O’Connor et al., 2008; Harvard Health Publishing, 2021), while cases with no changes in food intake have also been reported (Gibson, 2006; O’Connor et al., 2008). The phenomenon of changes in the food intake in individuals under stress is referred to as “stress eating” (Verbiest et al., 2021). Stress eating is considered a subset of emotional eating. Stress is reported as one of the causes of emotional eating (Wallis & Hetherington, 2009). Emotional eating is defined as eating according to mood, without feeling hungry, outside of meals, or without social obligation (Erkorkmaz et al., 2013; Croker et al., 2011).

Childhood and adolescence are developmental periods, in which social relationships play a vital role in shaping self-identity. Children experience stress, in particular, when attempting to adapt to situations such as exam anxiety and rapid changes occurring during this phase of life (Derks et al., 2018). Adolescence is also a period when an individual begins to gain autonomy in several aspects of life, including food-related choices. Numerous physiological, behavioral, and psychological changes begin to occur at the onset of adolescence (Alberga et al., 2012). Children and adolescents reportedly reduce their consumption of fruits and vegetables and become inclined to emotion-driven food consumption, which results in frequent high-calorie intake and low nutrition, particularly during stressful periods (Van Strien et al., 2012; Tate et al., 2015). Studies have reported changes in the food preference (Epel et al., 2001) and increases in the intake of sweet food (Zellner et al., 2006) and total energy (Rutters et al., 2009; Van Strien et al., 2012) during stress. Therefore, it is important to determine the eating situations caused by stress and the factors driving such scenarios in children and adolescents to plan and develop future intervention studies for the management of stress eating.

The effects of stress on emotional eating have been reported in many studies (Seki Öz & Bayam, 2022; Braden et al., 2018). However, the scale that can directly measure stress eating is limited in the literature. There is the Salzburg Stress Eating Scale (SSES), which measures stress eating in adults (Meule et al., 2018). SSES is used for the assessment of emotional eating, although it comprises items that refer only to stress. Importantly, the scale includes a change in the eating trend (Meule et al., 2018). Later, Verbiest et al. (2021) performed the Dutch/English adaptation of the SSES in Belgian children and adolescents (9–18 years old) and introduced the scale to the literature. However, the scale has not yet been adapted in different languages. In Türkiye, adolescents are under intense stress due to the fear of academic failure, especially due to the high school entrance exam in the 8th grade and the university exam in the 12th grade. Measuring the level of stress-related eating in children and adolescents provides significant benefits at both individual and social levels. These measurements have a critical role in supporting the healthy development of children, preventing possible psychological and physical problems, and improving the overall quality of life (Hsu & Raposa, 2021). Considering that there is no scale for the evaluation of stress eating in Turkish society, it is of great importance to have a scale for the evaluation of the effect of stress eating in a sample of children and adolescents. Early detection of stress-related eating habits in children ensures that necessary interventions are made in a timely manner and helps prevent such negative consequences (Paltoglou et al., 2021).

The Turkish literature contains a long version of the Emotional Eating Scale (EES), and the validity and reliability of this scale for application in the children and adolescent population were studied by Bektaş et al. (2016). However, the EES includes all sub-dimensions of emotional eating. It does not directly measure stress eating. At the same time, the SSES, which we conducted the adaptation study, has fewer items (10 items) and is more convenient to use. Another point that should be emphasised is that only EES is used in the studies since there is only one scale in Turkish related to emotional eating for children and adolescents. In this context, the adaptation of the SSES to Turkish will contribute to the diversity of scales and a more specific measurement tool will be introduced to the literature considering that the SSES consists only of items involving stress eating. In addition, this study will create a new point of reference for discussions on the psychometric properties of the SSES and will also contribute to international scientific studies through research using this scale. Therefore, this research aims to assess the reliability and validity of the SSES scale.

Study objective

The present study aimed to assess the Turkish validity and reliability of the Salzburg Stress Eating Scale for children and adolescents aged 9–18.

Methodology

Procedure

The present study was designed as a descriptive, methodological, and correlational one, conducted with a population of students from the 4th, 5th, 6th, 7th, 8th, 9th, 10th, 11th, and 12th grades from the primary, secondary, and high schools located in a city in the west of Türkiye. The assessment was conducted via an online survey, and the links of the Google Forms created for the survey by researchers were sent to the parents of the participants using a simple random method, skipping one branch, over a message application developed by the classroom teachers and school administrators. The individuals who provided their consent along with the parental consent via the online survey link were included in the study. Students who volunteered to participate in the study completed the questionnaires in the survey on their mobile phones/tablet computers/computers. During the data collection phase of the research, simple random sampling method was first used to send surveys to parents from class groups, and then voluntary sampling method was used as volunteer children were asked to fill out the online survey (Murairwa, 2015). All completed questionnaires were collected in e-tables via Google Drive. The survey could be completed in approximately 5–10 min by each student.

De Vellis (2012) recommended, including a minimum of 200 participants, as the sample size, in the study for the scale item number of 40 or less. Accordingly, 257 students who volunteered their participation were included in the present study.

Inclusion criteria

Age 9–18, ability to read and understand Turkish, no communication issues, and volunteering to participate in the study.

Exclusion criteria

Children under nine years of age, adults, and those with chronic diseases or eating disorders were excluded.

The general procedure of the research was as follows. In the first stage, permission was obtained from the owner of the scale by via e-mail for Turkish adaptation. Then, ethics committee permission was obtained. For the language validity of the scale, Dutch/English-Turkish translation and back-translation of the scale were carried out by two independent translators. Later, the scale was presented to 10 experts. Following expert opinion, a pilot study was conducted and the necessary final adjustments were made. Finally, the research data collection process began. The assessment was conducted via an online survey.

Data collection dates

The research data were collected between April 2023 and May 2023.

Language validity of the scale

When adapting a scale developed for a particular language to another language for implementation in the other language, certain rules have to be followed. The desired assessment of a phenomenon using a scale relies on the correct development of the scale. Any errors in the translation of a scale from one language to another may lead to invalid or misleading research outcomes (Hançer, 2003). Therefore, during scale adaptation to another language, the most appropriate sentence structure and idioms of the target language must be used, and items that are completely foreign to the target culture must be changed. In this context, the Salzburg Stress Eating Scale was adapted to Turkish, and written permission was received via e-mail from the researcher in the research team for this adaptation and the subsequent implementation in the context of the Turkish population. Thereafter, two independent linguists from Turkish-Dutch translation company, translated the scale from Dutch and English into Turkish. The scale, translated into Turkish, was translated back into its original languages [Dutch and English], and after this back-translation process, a Turkish language scientist evaluated the scale based on the Turkish grammar and spelling rules.

Expert opinion stage

In scale adaptation studies, obtaining the opinions of at least three and a maximum of 20 experts from the field related to the scale text is recommended, and the language validity must be reported in the literature (Akgül, 2003; Şencan, 2005; Yurdugül, 2005). The scale, translated from Dutch and English into Turkish, was sent to 10 experts from the fields of Pediatrics Nursing (PhD-min.10, max. 20 years of experience in pediatric nursing), Psychiatric Nursing (PhD-29 years of experience in psychiatric nursing), and Family Medicine (Medical Doctor, Professor-37 years of family medicine specialty experience). The experts were requested to assess the suitability of the scale items (1 = very suitable, 2 = suitable, 3 = requires little change, 4 = requires a considerable amount of changes). Later, the items in the scale were reviewed according to the opinions of these experts, and necessary changes were incorporated. The Content Validity Index (CVI) was utilized in the evaluation of expert opinions. When the item-based CVI values varied between 0.99 and 1.00, the scale-based content validity index was calculated to be 0.99.

Pretesting stage

After receiving the expert opinions, the scale to be adapted must be applied to a sample of 10–20 people who have characteristics similar to the people who would be included in the assessments conducted using the scale, although these people are not included in that sample (Akgül, 2003; Şencan, 2005). In the present study, the scale generated after receiving and incorporating expert opinions was applied to a sample of 20 students – 10 children and 10 adolescents – who matched the sample characteristics. A pilot study was then conducted, which revealed that the scale ’s comprehensibility was sufficient. Afterward, the validity and reliability of the scale were evaluated by applying the scale to the entire sample.

Measurements

Questionnaire form

The questionnaire form was prepared by the researchers in line with the literature (Bektaş et al., 2016; Oral & Ersan, 2017; Hill et al., 2018; Verbiest et al., 2021). It contained seven questions to retrieve information on the age, gender, family type, perceived economic level, academic achievement, height, and weight of the subjects in the sample.

Salzburg Stress Eating Scale (SESS) adapted for children and adolescents

The Salzburg Stress Eating Scale (SSES) for adults is developed ten-item questionnaire assessing eating in response to stress by Meule et al. (2018). The items describe stressful situations (e.g., “When I feel things are out of control”) and ask individuals how such situations affect their eating (Meule et al., 2018). The scale was later adapted for children and adolescents by Verbiest et al. (2021). The scale, comprises ten items and a single subscale, with the following response categories: “1 = I eat much less than usual, 2 = I eat less than usual, 3 = I eat just as usual, 4 = I eat more than usual, 5 = I eat much more than usual”. The lowest attainable score on the scale is 10, while the highest score is 50. In the original study, the psychometric properties and the correlations of the SSES were evaluated in a sample of Dutch-speaking adolescents (general population; N = 244, age 9–18 years, adjusted BMI range = 71–189%, M = 103%) and also in an inpatient sample of adolescents with obesity (obesity sample; N = 100, age 9–16 years, adjusted BMI range = 151–310%, M = 194.5%). The EFA of the scale when applied to the general population, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy (KMO = 0.855), and the Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity [χ2(45) = 876.6, p < 0.001] revealed that the scale explained 44.4% of the total variance. The factor loadings ranged from 0.41 to 0.75. In the obesity sample, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy (KMO = 0.883) and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity [χ2(45) = 549.7, p < 0.001] revealed that the scale explained 54.1% of the variance. The factor loadings ranged from 0.48 to 0.83 (Verbiest et al., 2021). In the original study on the scale, Cronbach’s α value for the scale was determined to be 0.85 for the general population and 0.90 for the sample of obese adolescents (Verbiest et al., 2021).

Data analysis

All data were analyzed statistically using the IBM SPSS Statistics 25 and IBM SPSS AMOS 25 software packages. Descriptive statistics were included in the analysis of the socio-demographic data of the participants. The Body Mass Index (BMI) of each participant was calculated based on the participant’s height (m) and weight (kg) using the formula: BMI = Weight/Height2. It is recommended that in children, the percentile values should be compared according to age and gender after calculating the BMI. If a child’s BMI is above the 95th percentile according to age and gender, he/she should be classified as obese. If the BMI is between the 85th and 95th percentile, he/she should be classified as being overweight (at risk for obesity or being overweight). If the BMI is between 85 and 5, he/she should be classified as having a normal weight, and a BMI below 5 should be considered underweight (Neyzi et al., 2008). In the present study, the above BMI classification method was used for all participants. The subsequent validity analysis was performed based on the content validity index (CVI), exploratory factor analysis (EFA), confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), average variance extracted (AVE), composite reliability (CR) (for convergent validity), and linear regression analysis (for predictive validity). The reliability analysis was performed based on the item-total score, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, and McDonald’s omega coefficient, which determined the internal consistency of the scale. The statistical methods used in the present study are presented in Fig. 1. The margin of error used in the data evaluation was p = 0.05.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Scientific Research and Publication Ethics Committee of a university (Date-Number: 03.03.2023-159483). The institutional permission for the study was obtained from the Provincial Directorate of National Education after acquiring permission from the owner of the scale used in the study via e-mail. Written consent was acquired online from all participants of the study and their parents. The research was carried out in accordance with the rules of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

The demographic data of the participants revealed the following: 60.7% of the participants were female and 39.3% were male; 86% had a nuclear family, 7.8% had an extended family, and 6.2% had a fragmented family; 77.8% reported their perceived economic level as medium, 18.3% reported their perceived economic level as good, and 3.9% reported their perceived economic level as poor; 50.6% regarded their achievements at school as average, 42.8% regarded their achievements at school as good, and 6.6% regarded their achievements at school as poor; 8.6% had a percentile value above 95% (obese), 10.9% had a percentile value between the 85th and 95th percentile (overweight), 13.2% had a percentile value below the 5th percentile (underweight), and 67.3% had a percentile value between the 85th and 5th percentile (normal); the mean age of the participants was 13.83 ± 2.38 years (minimum = 9.00 and maximum = 18.00).

Construct validity

The construct validity of the scale was evaluated using the exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA).

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA)

The “Principal Component Method” was used as the factor extraction method in EFA. Varimax factor rotation was used. In order to examine the factor structure, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test was conducted to determine sample adequacy and Bartlett’s test was conducted to determine whether the factor analysis could be conducted for the scale (Watkins, 2018).

Prior to the exploratory factor analysis, the KMO test was conducted to determine the suitability of the sample size for factorization. The analysis revealed a KMO value of 0.91, according to which the sample size was “perfectly sufficient” to conduct the factor analysis (Watkins, 2018). Further, an analysis of the results of Bartlett’s test of sphericity revealed that the determined chi-square value was significant [χ2 (45) = 1006.544, p < 0.01]. Therefore, it was inferred that the data were derived from a multivariate normal distribution (Table 1). The EFA revealed the presence of a component with an eigenvalue above 1.0 for 10 items, and this component contributed 48.86% to the total variance (Table 1). In scale adaptation studies, the acceptance level for factor loading values is reported to be 0.30, according to the exploratory factor analysis conducted to determine a scale’s factor pattern (Finch, 2019). In the present study, the factor loadings of the scale varied between 0.43 and 0.77 (Table 1).

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics at the item level. The item means ranged from 2.35 to 2.95 (on a 5-point scale). The skewness and kurtosis values were between − 1 and + 1. According to the literature, the skewness and kurtosis values should be between − 2 and + 2 (George & Mallery, 2010). Item-based skewness and curtosis values of the scale were found to be between − 0.07 and 0.54, -0.51-0.00, respectively. The discriminatory power for the 10 items was determined to be in the range of 0.69–0.75.

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA)

The measurement model established to confirm the ten-item, single-factor structure was subjected to CFA. The results revealed that the structural equation model of the scale was significant at the level of p = 0.000, and the 10 items constituting the scale were related to the entire scale structure. In accordance with the measurement model, the items constituting the scale and the standardized regression coefficients of the paths on the one-way arrows were observed. The determined factor loading was above 0.30 (Marsh et al., 2020) and ranged between 0.38 and 0.74 (Fig. 2).

The goodness-of-fit index values determined for the scale were as follows: χ2 2.41 (p = 0.000); CFI 0.95; AGFI 0.90; RMSEA 0.07; GFI 0.94; SRMR 0.04 (Table 2).

Convergent validity

The AVE determined for the SSES was 0.44, and the CR was 0.82. The CR value was, therefore, greater than AVE (Table 3).

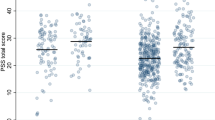

Predictive validity

In the linear regression analysis, a model was created according to the relationship between the body mass index-percentile values. In the model, body mass index-percentile value of the child explained 4% of the SSES. As the body mass index-percentile value of the children increased, the SSES score increased by 0.201 (β = 0.201). When the beta coefficient value, t value and significance level of the independent variable are analysed, it is seen that the body mass index-percentile value has a statistically significant and positive effect on SSES (t = 3.280, p < 0.05) (Table 4).

Reliability

The Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega values determined for the scale were 0.88 and 0.88, respectively. The split-half analysis revealed a Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.76 for the first half and 0.81 for the second half. The Spearman–Brown coefficient was 0.87, Guttman’s split-half coefficient was 0.87, and the correlation coefficient between the two halves was 0.77. In regard to the overall scale, the floor effect was 0.77%, and the ceiling effect was 6.2% (Table 3).

Item–total score analysis of the scale

Item-total score analysis explains the correlation between the scores obtained from every item of a scale and the scale’s total score, indicating whether the items in the scale measure the desired quality (DeVellis, 2012; Jonhson & Christensen, 2014). It is recommended that this correlation value be greater than 0.30 and as close to 1 as possible (Jonhson & Christensen, 2014). In the present study, the correlation of the items with the scale’s total score was determined to be in the range of 0.47–0.76 (Table 1).

Discussion

Salzburg Stress Eating Scale (SSES) was developed by Meule et al. (2018) for the evaluation of stress eating in adults. The Dutch version of SSES was later developed, based on the adult version of this scale, by Verbiest et al. (2021) for children and adolescents aged 9–18 (Verbiest et al., 2021; Meule et al., 2018). SSES assesses the changes in eating behavior without reference to basic emotions and comprises items that refer only to stress. It also considers the trend of changes in eating behavior; for instance, certain people eat more while others eat less when under stress (Verbiest et al., 2021). The literature does not contain any study validating any version of SSES other than the Dutch version. Therefore, the present study aimed to develop a version of the Salzburg Stress Eating Scale (SESS) for Turkish adolescents aged 9–18 and compare the total SSES scores among the participants with a different BMI classification.

In the first stage of the study, the obtained scale adaptation results were compared with those reported in the literature.

In the present study, the item-based content validity index value was determined to be 0.99–1.00 and the total content validity index value was 0.99. The literature also reports the item and scale-based content validity index values above 0.80 for this scale. Therefore, the fact that these values in this study are as suggested by the literature indicates the harmony between expert opinions (Polit et al., 2007) and that the scale adequately measures the subject.

The scale’s construct validity is determined by evaluating the suitability and adequacy of the data for factor analysis using Bartlett’s test of sphericity and KMO analysis. In the factor analysis, the results of Bartlett’s test of sphericity must be at a statistically significant level. Furthermore, the KMO value must be 0.60 or above (Boateng et al., 2018). The findings of the exploratory factor analysis conducted in the present study (Table 2) demonstrated that the sample size of the present study was adequate for conducting a factor analysis. In the original study reporting the scale (Verbiest et al., 2021), the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin value and Bartlett’s test of sphericity results were similar to those obtained in the present study.

The explained variance ratio is considered one of the essential indicators of construct validity in scale development and adaptation studies. It is suggested that this ratio should be above 40% (Finch, 2019). The explained variance ratio obtained in the present study was 48.88%, which indicates an acceptable level of construct validity. In the original study reporting the scale, the explained variance ratio was determined to be 44.4% for the general population and 54.1% for the obese sample group (Verbiest et al., 2021), results which are similar to those obtained in the present study.

The literature suggests that the item factor loading should be 0.30 or higher, and the t items with factor loading values below 0.30 should be removed from the scale(Finch, 2019). In the present study, the factor loadings of the scale items were found to be above 0.4 (Table 1). Which is consistent with the results obtained in the original study (Verbiest et al., 2021), indicating a strong factor structure of the scale.

It is generally recommended to calculate the discriminatory power values of scale items in scale development/adaptation studies. The literature suggests that the items with a discriminatory power value of “0.39 or above” should be considered to be at a excellent level (Escudero et al., 2000). Accordingly, the present study concluded that the discriminatory power values of all items of the evaluated scale were excellent. Since the original study reporting the scale did not provide the discriminatory power values for the scale, a comparison was not possible.

The literature also recommends that the factor structure determined based on the exploratory factor analysis should be investigated using confirmatory factor analysis (Brown, 2015; Xia & Yang, 2019). The confirmatory factor analysis conducted in the present study confirmed the unidimensional structure of the scale. According to the existing literature, the model fit indices higher than 0.90 are accepted as an indication of an excellent fit. Moreover, the χ2/df value below 3 and the RMSEA value below 0.08 are considered excellent (Brown, 2015; Marsh et al., 2020). Accordingly, the present study concluded that the fit index values were excellent (Table 2). It was not possible to compare these results with the original study reporting the scale, as that study did not provide these values.

The convergent validity of the measurement model may be assessed based on AVE and CR. AVE reflects the level of variance captured by a construct relative to the level of variance due to measurement error. CR, on the other hand, is a less biased estimate of reliability compared to Cronbach’s alpha value, and a CR value of 0.6 or above is considered acceptable (Fornell & Larcker, 1981; Cheung et al., 2023). The CR value of 0.82 obtained in the present study indicated that the evaluated scale had good stability in terms of reflecting the measurement results and indicates composite reliability (Hair et al., 2017). The AVE value of SSES was determined to be 0.44. For convergent validity, AVE should be equal to or higher than 0.50 but lower than CR (Fornell & Larcker, 1981; Huang et al., 2013; Netemeyer et al., 2003). But, according to Fornell and Larcker (1981) criterion, AVE less than 0.50 but CR greater than 0.60 indicates that convergent validity is achieved.

Within the scope of predictive validity, the effect of participants’ BMI-percentile values on the SSES total score was examined. It was revealed that as the percentile value increased, the average SSES score of the participants increased. A study conducted with children between the ages of 5–12 showed that stress can increase emotional eating behavior in children and lead to excessive weight gain (Michels et al., 2012). Özer et al. (2014) reported that the average emotional eating score was higher in obese children. Another study stated that stress sensitivity encourages unhealthy eating and emotional eating in children and increases the intake of high-fat/carbohydrate-containing snacks accompanied by strong cortisol reactivity (Wijnant et al., 2021). Therefore, the results of this study are consistent with the literature, and it can be interpreted that the SSES provides predictive validity over the BMI-percentile variable.

In regard to the reliability of the scale, the alpha coefficient is a measure of the homogeneity of the scale items. A higher alpha coefficient of a scale indicates that “the scale items are consistent with each other and examine the elements of the same feature or that all scale items work together”. Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega (ω) values are rarely different. Therefore, McDonald’s omega (ω) coefficient, also referred to as construct reliability (Yurdugül, 2006; Hayes & Coutts, 2020), was also calculated within the scope of reliability analysis in the present study. The literature recommends that Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega coefficients should be higher than 0.70 (Alpar, 2014; Soysal, 2023). In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha (α) reliability coefficient was determined to be 0.88, and McDonald’s omega (ω) reliability coefficient was 0.88. In the original study reporting the scale, Cronbach’s α value was determined to be 0.85 for the general population and 0.90 for the obese sample group (Verbiest et al., 2021). Accordingly, it was inferred that the reliability of the scale adapted in the present study was sufficient, and construct reliability was provided. In addition, Cronbach’s alpha values of the scale determined using the split-half method for the determination of reliability were higher than 0.70 and a strong and significant correlation existed between the halves. Spearman-Brown and Guttman’s split-half coefficients were 0.872 and 0.87, respectively. Since the split-half values were not reported in the original study, a comparison was not possible. Further, the floor effect value of the scale was determined to be 0.77% in the present study, while the ceiling effect was 6.2%. These values indicated that the scale was a reliable measurement tool and could adequately measure the concept desired to be measured (DeVellis, 2012; Karagöz, 2019). It was not possible to compare these result values with the original study as the latter did not report these values.

The item–total score analysis is another evaluation considered important for scale validity and reliability studies. This analysis confirms whether the scale items measure the variable desired to be measured. Accordingly, the relationship between the scores obtained from the different items in the scale and the scale’s total score is revealed (Jonhson & Christensen, 2014). The literature suggests that this value should be 0.30 or higher and as close to 1.0 as possible, with a positive correlation (Jonhson & Christensen, 2014). In the present study, these values were above 0.40, with a positive correlation. It was not possible to compare these result values with the original study, which did not provide these values.

Limitations

The fact that the height and weight data of the participants were recorded according to their statements could be a limitation of the present study. Another limitation is that the study was conducted with the general population and so the number of obese participants was low.

Conclusions

SSES is a valid and reliable assessment tool for the Turkish-speaking sample and could, therefore, be used effectively to evaluate stress eating in children and accordingly develop effective interventions for stress-related eating disorders. Nurses and other health professionals working with children can use this measurement tool for the early detection of stress-related eating disorders during the process of taking anamnesis from the child and his/her family (data collection phase), after determining the child’s BMI classification. It is also recommended for use in the follow-up of children and adolescents who are physically diagnosed as clinically obese and overweight.

Since the research was conducted on the general population, the number of obese groups was small. Studied in focus groups is recommended. As a result of this study, in addition to the Dutch version of SSES, the Turkish version was also added to the literature. It is recommended to adapt the scale in different cultures to determine the level of direct stress eating in children and adolescents and the affecting factors. It is also recommended to conduct methodological and cross-sectional or intervention (Randomized Controlled Study) studies in different BMI groups using SSES.

Data availability

The data provided in the present report are part of an ongoing project. Therefore, for privacy or ethical concerns, the primary data have not been provided publicly.

References

Akgül, A. (2003). Tıbbi Araştırmalarda İstatistiki Analiz Teknikleri “SPSS Uygulamaları” (2 Baskı). Emek Ofset Ltd Şti.

Alberga, A. S., Goldfield, G. S., Kenny, G. P., Hadjiyannakis, S., Phillips, P., Prud'Homme, D., ... & Sigal, R. J. (2012). Healthy Eating, Aerobic and Resistance Training in Youth (HEARTY): Study rationale, design and methods. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 33(4), 839–847. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2012.04.004

Alpar, R. (2014). Spor, Sağlık ve Eğitim Bilimlerinden Örneklerle Uygulamalı İstatistik ve Geçerlik- Güvenirlik-SPSS’de Çözümleme Adımları Ile Birlikte (3 Baskı). Detay Yayıncılık.

Bektas, M., Bektas, I., Selekoğlu, Y., Kudubes, A. A., Altan, S. S., & Ayar, D. (2016). Psychometric properties of the Turkish version of the emotional eating scale for children and adolescents. Eating Behaviors, 22, 217–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2016.06.021

Boateng, G. O., Neilands, T. B., Frongillo, E. A., Melgar-Quiñonez, H. R., & Young, S. L. (2018). Best practices for developing and validating scales for health, social, and behavioral research: A primer. Frontiers in Public Health, 6, 149. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2018.00149

Braden, A., Musher-Eizenman, D., Watford, T., & Emley, E. (2018). Eating when depressed, anxious, bored, or happy: Are emotional eating types associated with unique psychological and physical health correlates? Appetite, 125, 410–417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2018.02.022

Brown, T. A. (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research (2nd ed.). The Guilford Press.

Cheung, G. W., Cooper-Thomas, H. D., Lau, R. S., & Wang, L. C. (2023). Reporting reliability, convergent and discriminant validity with structural equation modeling: A review and best?practice recommendations. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 1–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-023-09871-y

Croker, H., Cooke, L., & Wardle, J. (2011). Appetitive behaviours of children attending obesity treatment. Appetite, 57(2), 525–529. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2011.05.320

Derks, I. P., Sijbrands, E. J., Wake, M., Qureshi, F., Van Der Ende, J., Hillegers, M. H., ... & Jansen, P. W. (2018). Eating behavior and body composition across childhood: a prospective cohort study. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 15, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-018-0725-x

DeVellis, R. F. (2012). Scale development, theory and applications. SAGE Publication Inc.

Epel, E., Lapidus, R., McEwen, B., & Brownell, K. (2001). Stress may add bite to appetite in women: A laboratory study of stress-induced cortisol and eating behavior. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 26(1), 37–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0306-4530(00)00035-4

Erkorkmaz, Ü., Yılmaz, R., Demir, O., Sanislioğlu, S. Y., Etikan, İ, & Özçetin, M. (2013). Analysis of the correlation between children’s eating behavior and parent’s feeding style using canonical correlation analysis. Turkiye Klinikleri Journal of Medical Sciences , 33(1), 138–148.

Escudero, E. B., Reyna, N. L., & Morales, M. R. (2000). The level of difficulty and discrimination power of the Basic Knowledge and Skills Examination (EXHCOBA). Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa, 2(1), 2.

Finch, H. W. (2019). Exploratory factor analysis. SAGE Publications.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18, 39–50.

George, D., & Mallery, M. (2010). SPSS for windows step by step: A simple guide and reference, 17.0 update (10a ed.). Pearson.

Gibson, E. L. (2006). Emotional influences on food choice: Sensory, physiological and psychological pathways. Physiology & Behavior, 89(1), 53–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.01.024

Hair, J., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed.). Sage.

Hançer, M. (2003). Ölçeklerin yazım dilinden başka bir dile çevirileri ve kullanılan değişik yaklaşımlar. Balıkesir Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi, 6(10), 47–59.

Harvard Health Publishing. (2021). Why stress causes people to overeat. https://www.health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/why-stress-causes-people-to-overeat. Accessed 30.18.2023.

Hayes, A. F., & Coutts, J. J. (2020). Use omega rather than Cronbach’s alpha for estimating reliability. But? Communication Methods and Measures, 14(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2020.1718629

Hill, D. C., Moss, R. H., Sykes-Muskett, B., Conner, M., & O’Connor, D. B. (2018). Stress and eating behaviors in children and adolescents: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Appetite, 123, 14–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2017.11.109

Hsu, T., & Raposa, E. B. (2021). Effects of stress on eating behaviours in adolescents: A daily diary investigation. Psychology & Health, 36(2), 236–251.

Huang, C. C., Wang, Y. M., Wu, T. W., & Wang, P. A. (2013). An empirical analysis of the antecedents and performance consequences of using the moodle platform. International Journal of Information and Education Technology, 3(2), 217–221.

Jonhson, B., & Christensen, L. (2014). Educational research: Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed approaches. SAGE Publication Inc.

Karagöz, Y. (2019). SPSS-AMOS-META Uygulamalı İstatistiksel Analizler (2 Baskı). Nobel Yayıncılık.

Levitt, P. (2015). Toxic stress and its impact on early learning and health: Building a formula for human capital development. Wisconsin Family Impact Seminars. https://www.purdue.edu/hhs/hdfs/fii/wpcontent/uploads/2015/07/s_wifis32c02.pdf. Accessed 10.09.2023.

Marsh, H. W., Guo, J., Dicke, T., Parker, P. D., & Craven, R. G. (2020). Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), exploratory structural equation modeling (ESEM), and set-ESEM: Optimal balance between goodness of fit and parsimony. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 55(1), 102–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2019.1602503

Meule, A., Reichenberger, J., & Blechert, J. (2018). Development and preliminary validation of the Salzburg stress eating scale. Appetite, 120, 442–448. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2017.10.003

Michels, N., Sioen, I., Braet, C., Eiben, G., Hebestreit, A., Huybrechts, I., & De Henauw, S. (2012). Stress, emotional eating behaviour and dietary patterns in children. Appetite, 59(3), 762–769. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2012.08.010

Middlebrooks, J. S., & Audage, N. C. (2008). The effects of childhood stress on health across the lifespan. http://health-equity.pitt.edu/932/1/Childhood_Stress.pdf. Accessed 10.09.2023.

Murairwa, S. (2015). Voluntary sampling design. International Journal of Advanced Research in Management and Social Sciences, 4(2), 185–200.

Netemeyer, R. G., Bearden, W. O., & Sharma, S. (2003). Scaling procedures: Issues and applications. Sage Publications.

Neyzi, O., Günöz, H., Furman, A., Bundak, R., Gökçay, G., & Darendeliler, F. (2008). Türk çocuklarında vücut ağırlığı, boy uzunluğu, baş çevresi ve vücut kitle indeksi referans değerleri. Çocuk Sağlığı ve Hastalıkları Dergisi, 51(1), 1–14.

O’Connor, D. B., Jones, F., Conner, M., McMillan, B., & Ferguson, E. (2008). Effects of daily hassles and eating style on eating behavior. Health Psychology, 27(1), 20–31. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.27.1.S20

Oral, T., & Ersan, C. (2017). Adaptation of the perceived stress scale in children (8–11 years) into Turkish. Selçuk Üniversitesi Edebiyat Fakültesi Dergisi, 37, 419–428. https://doi.org/10.21497/sefad.328629

Özer, S., Bozkurt, H., Sönmezgöz, E., Bilge, S., Yilmaz, R., & Demir, O. (2014). Obezite tanılı çocuklarda yeme davranışının değerlendirilmesi. Çocuk Dergisi, 14(2), 66–71.

Paltoglou, G., Chrousos, G. P., & Bacopoulou, F. (2021). Stress management as an effective complementary therapeutic strategy for weight loss in children and adolescents with obesity: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Children, 8(8), 670.

Polit, D. F., Beck, C. T., & Owen, S. V. (2007). Focus on research methods: Is the CVI an acceptable indicator of content validity? Appraisal and recommendations. Research in Nursing and Health, 30(4), 459–467. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.20199

Rutters, F., Nieuwenhuizen, A. G., Lemmens, S. G., Born, J. M., & Westerterp-Plantenga, M. S. (2009). Acute stress‐related changes in eating in the absence of hunger. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.), 17(1), 72–77. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2008.493

Seki Öz, H., & Bayam, H. (2022). The relationship of perceived stress and loneliness to emotional eating in young adults. Sağlık Bilimleri Dergisi (Journal of Health Sciences), 31(2), 176–183.

Şencan, H. (2005). Sosyal ve Davranışsal Ölçümlerde Güvenirlilik ve Geçerlilik (2 Baskı). Seçkin Yayıncılık.

Soysal, S. (2023). Çok Boyutlu Test Yapılarında Alfa, Tabakalı Alfa Ve Omega Güvenirlik Katsayılarının Karşılaştırılması. Ahmet Keleşoğlu Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi (AKEF) Dergisi, 5(1), 213–236. https://doi.org/10.38151/akef.2023.51

Tate, E. B., Spruijt-Metz, D., Pickering, T. A., & Pentz, M. A. (2015). Two facets of stress and indirect effects on child diet through emotion-driven eating. Eating Behaviors, 18, 84–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2015.04.006

Thompson, R. A. (2014). Stress and Child Development. https://www.fcdus.org/assets/2014/07/24_01_02.pdf. Accessed 10.09.2023.

Van Strien, T., & Koenders, P. G. (2012). How do life style factors relate to general health and overweight? Appetite, 58(1), 265–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2011.10.001

Verbiest, I., Blechert, J., Debeuf, T., Verbeken, S., Klosowska, J. C., Michels, N., De Henauw, S., & Braet, C. (2021). Is there stress eating in children and adolescents? A first validation of the Dutch version of the Salzburg stress eating Scale. Appetite, 167, 105657. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2021.105657

Wallis, D. J., & Hetherington, M. M. (2009). Emotions and eating. Self-reported and experimentally induced changes in food intake under stress. Appetite, 52, 355–362.

Watkins, M. W. (2018). Exploratory factor analysis: A guide to best practice. Journal of Black Psychology, 44(3), 219–246. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095798418771807

Wible, C. (2013). Why you should fake a smile: How your emotions affect your student’s learning. http://www.opencolleges.edu.au/informed/features/contagious-emotions/. Accessed 10.09.2023.

Wijnant, K., Klosowska, J., Braet, C., Verbeken, S., De Henauw, S., Vanhaecke, L., & Michels, N. (2021). Stress responsiveness and emotional eating depend on youngsters’ chronic stress level and overweight. Nutrients, 13(10), 3654.

Xia, Y., & Yang, Y. (2019). RMSEA, CFI, and TLI in structural equation modeling with ordered categorical data: The story they tell depends on the estimation methods. Behavior Research Methods, 51(1), 409–428. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-018-1055-2

Yurdugül, H. (2005). Ölçek Geliştirme Çalışmalarında Kapsam Geçerliği için Kapsam Geçerlik İndekslerinin Kullanılması. XIV. Ulusal Eğitim Bilimleri Kongresi.

Yurdugül, H. (2006). Paralel, eşdeğer ve konjenerik ölçmelerde güvenirlik katsayılarının karşılaştırılması. Ankara Üniversitesi Eğitim Bilimleri Fakültesi Dergisi, 39(1), 15–37. https://doi.org/10.1501/Egifak_0000000127

Zellner, D. A., Loaiza, S., Gonzalez, Z., Pita, J., Morales, J., Pecora, D., & Wolf, A. (2006). Food selection changes under stress. Physiology & Behavior, 87(4), 789–793. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.01.014

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the children and their families for their collaboration with the study.

Funding

Open access funding provided by the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Türkiye (TÜBİTAK).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study design: -HZ, AAK; Data Collection and / or Processing, Analysis and / or Interpretation:- HZ, AAK; Preparation of the Manuscript, Critical Review and / or Revision: - HZ, AAK. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical considerations of the study

The study’s ethics approval was received from a University Ethics Committee (Date-Number: 03.03.2023-159483).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zengin, H., Akdeniz Kudubes, A. Validity and reliability study of the Turkish version of the Salzburg Stress Eating Scale for children and adolescents. Curr Psychol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-06312-x

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-06312-x