Abstract

To support broader efforts to empower military personnel to improve their health and wellbeing, the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) have implemented numerous mental wellbeing programs and resources. The aim of the present study was to better understand factors that may drive awareness and use of these programs/resources. Data from the Your Say Survey, which is routinely administered to CAF members to assess their perceptions of policies and programs, were analyzed to identify key predictors of awareness and use of programs and resources promoting positive mental health at the individual, unit leader, and organizational levels. The survey was completed in 2021 by a stratified random sample of 1,743 Regular Force members, which was weighted to be representative of the CAF Regular Force population. Awareness of most programs/resources that were considered was found to be quite high, whereas use was comparatively low. Results of logistic regression analyses revealed that program/resource awareness was generally lower among younger CAF members, those who were single and had no dependent children, and those who indicated their supervisors infrequently demonstrated positive behaviours around mental health. Awareness also varied depending on the organizational command in which CAF members worked. It was found that CAF members were generally more likely to have used the program/resource if they reported poorer self-rated mental health and were older. Similar to program/resource awareness, use varied significantly depending on CAF members’ organizational command. The potential implications of these findings for enhancing awareness of mental wellbeing programs and resources in the CAF, and in occupational settings as a whole, are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Mental health disorders are a major global health concern with a consistent pre-pandemic world-wide prevalence of approximately 13% (World Health Organization [WHO], 2022a). In 2019 an estimated 970 million people lived with some form of mental health disorder, with estimates of approximately 36 million living with drug use disorders and estimates of approximately 283 million living with alcohol use disorder in 2016 (WHO, 2022a). Moreover, over 700,000 people are estimated to have died by suicide in 2019 alone (WHO, 2021). Importantly, mental health is highly affected during public health emergencies, with the most notable recent emergency being the COVID-19 pandemic (WHO, 2022a). Indeed, the rates of mental health disorders increased dramatically in the year following the start of the pandemic, with major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders increasing by 28% and 26%, respectively (WHO, 2022a). Rates of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts also increased during the pandemic, despite a slight downward trend in actual deaths by suicide (Yan et al., 2023). There are many possibilities as to how the pandemic has led to an increase in mental health disorders, such as reduced availability of mental health resources with the health systems overrun, and fear/isolation stopping those in need from accessing needed support (WHO, 2022a).

The mental health statistics cited above underscore the need for programs to support mental health and build resilience to mitigate the impacts of crises, like the COVID-19 pandemic. Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study, a resource that has examined global injury, disability, and mortality rates by diseases across regions and demographics of note since 1990, reveal that the burden of most disabilities, measured in total years lived with disability and including mental disorders, are mainly concentrated in those who are working-aged (Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, 2018). This highlights the importance of the work environment in providing mental health support measures for employees. Indeed, more and more employees are expecting their employers to consider mental wellness and provide supports such as mental health days and better mental health benefits (Bloznalis, 2022), and many employers have started to provide programs and resources aimed at mental wellness and health promotion (Mattke et al., 2015).

However, the benefits of these programs depend on participation. Unfortunately, many studies examining use of employer-initiated mental wellness programs reveal that these are often under-utilized (Bensa & Sirok, 2023; Mattke et al., 2015; Ryde et al., 2013). A recent scoping review examining workplace wellbeing participation rates revealed that over half of the articles examined reported participation rates of less than 50% (Bensa & Sirok, 2023). While there are many potential barriers to employees’ use of workplace wellness programs and resources, one that often stands out in the literature is lack of awareness. The current study focuses on predictors of program awareness and participation in a sample of Canadian military members, although the findings may also have implications for broadening the reach and impacts of these supports among other populations.

Mental wellbeing programs and resources in the Canadian Armed Forces

Like many organizations, the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) have implemented numerous programs and resources in response to mental health concerns in the Canadian military. Such programs and resources may be especially valuable in military organizations given the high-risk nature of the occupation. Military personnel - particularly those that have deployed and experienced combat - have demonstrated high prevalence rates of mental health disorder across the world, including post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, panic and anxiety disorders, and increased alcohol use (Crum-Cianflone et al., 2016; Fikretoglu et al., 2022; Stevelink et al., 2018; Zamorski et al., 2014). This is in part due to the unique stressors they face, including separation from family due to deployment, frequent relocations, long-hours, and the inherent dangers of high-risk operations (Sareen et al., 2007).

Although providing military personnel with mental health programs and resources is part of the overarching strategy to improve health and wellness in the CAF (Department of National Defence, 2022), implementing such programs and resources in the military context can be challenging, given the complex structure of the organization. The CAF are comprised of multiple commands, including the Canadian Army (CA), Royal Canadian Navy (RCN), Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF), and Military Personnel Command (MPC), among others, which may result in varying needs and preferences. It may also be difficult to monitor the extent and manner in which programs and resources are being rolled out in these commands, given the wide geographical dispersion of units. For instance, members of the CA and RCAF tend to be dispersed throughout the entire country, including in larger cities and much smaller less-populated communities, while those of the RCN tend to be concentrated in some of the larger cities along the coastline. Importantly, while the commands often experience similar challenges, they also face unique concerns that can affect the promotion of, and emphasis on, various wellbeing programs and initiatives, potentially leading to differing degrees of awareness. Finally, all these commands have unique training requirements and deployment schedules, with varying times away from their home bases, adding to the difficulty in accessing some CAF programs and services. For instance, MPC tends to be more centrally located in the capital city, Ottawa, as they are the command responsible for personnel management, including the provision of support, training, and education for members, and the development of various personnel-related policies and programs. Indeed, many of the health and wellbeing initiatives offered by the CAF are being developed by the Strengthening the Forces (StF) health promotion program under MPC (National Defence and the CAF, 2023). Specific health promotion programs are researched and developed centrally by subject matter experts within Canadian Forces Health Services and delivered by local staff at bases and wings across Canada (National Defence and the CAF, 2023). These challenges may have an impact on the overall reach of these programs, in addition to other factors discussed in the next section.

Factors impacting awareness and participation

Very little research exists examining awareness of mental wellness programs and resources in a military context. Limited research in the CAF has indicated that 72% of Regular Force personnel reported being aware of the overall StF health promotion program (Thériault et al., 2016). Of note, some studies have pointed to potential group differences based on demographic and military characteristics (Gottschall, 2022; Thériault et al., 2016). Specifically, findings from a study examining program awareness among RCN personnel revealed lower awareness of various CAF StF programs by young, single members of lower military ranks (Gottschall, 2022). Although older, a similar study examining awareness of StF programs also reported higher awareness among females and RCAF personnel, compared to RCN and CA personnel (Thériault et al., 2016). These survey results did not address demographic differences in participation, but previous civilian research has identified demographic differences in participation in workplace health promotion programs (e.g., Hall et al., 2017).

Additionally, having an effective communication strategy has been identified as a key factor for workplace wellbeing program success, and civilian research indicates that organizational leaders and supervisors can play a critical role in increasing awareness of available resources for employees (Mattke et al., 2013). The same may be said for military leaders and supervisors. For example, recent survey results indicated that one of the most common ways that CAF members learned about the Canadian Armed Forces – Veterans Affairs Canada Joint Suicide Prevention Strategy, which includes a number of initiatives and programs to reduce risk factors and increase protective factors in order to prevent suicide, was a briefing from their unit leader (Gottschall, 2020). Survey research conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic also indicated that supervisors were important sources of information to help subordinates navigate their challenges (Goldenberg & Lee, 2020).

Aside from providing information about available mental wellbeing programs and resources, the civilian literature has noted that managers have the ability to act as advocates for their employees’ wellbeing through numerous mechanisms, by encouraging them to take some time away from work to participate in these programs and helping them manage their workloads so that they feel more able to take the time to participate (Santos, 2019). Managers can even go as far as providing “mandatory wellbeing time”, essentially temporarily releasing employees from any work demands, where they are encouraged to fully leave their work responsibilities to participate in mental wellbeing activities (Santos, 2019). By implementing this “mandatory wellbeing time”, the manager both nullifies the employee’s need to seek permission to attend and use such programs and resources and any feelings of guilt about neglecting their work for their own mental wellbeing (Santos, 2019). Military leaders may have a similar influence on their subordinates, which may even be amplified given the especially hierarchical structure of military organizations.

Research has also indicated that participation may be influenced by a perceived need for support. In a study examining interest in participating in workplace wellness programs by civilian employees who had returned to work following a work-related permanent impairment, those who reported past-year depression and poorer current health status were more likely to indicate interest in these programs (Sears et al., 2022). Within a military context, research has indicated that a greater need for support was linked to greater use of relevant supports for ill and injured members transitioning out of the military (Lee et al., 2020). However, since mental health promotion programs are marketed to the general population rather than specifically targeting those already experiencing health issues, initial awareness of these programs may not be expected to be linked to current health needs.

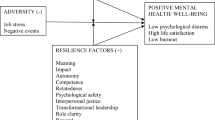

Finally, when considering participation rates, the program or resource style and offering themselves seem to make a difference. A multi-component intervention approach has been shown to increase participation in wellness programs, possibly because wellbeing can be very individualized. Therefore, having more options may lead to greater participation (Robroek et al., 2009). A focus on multiple behaviours has similarly been associated with greater participation rates (Robroek et al., 2009). Both findings demonstrate the importance of variety in mental wellbeing program and resource offerings. Broader guidance for health promotion from the WHO identifies multiple action areas for interventions, such as building healthy public policy, creating supportive environments, and developing personal skills through health education (WHO et al., 1986). Further, multi-level interventions targeting risk and protective factors at individual, relational, community and societal levels have been recommended for a broad range of public health issues, such as suicide prevention (Cramer & Kapusta, 2017). Within the CAF, a modified Social Ecological Framework informed the current physical performance strategy to promote positive health behaviours at different levels of intervention within the military organization, including the individual, family and friends, base/wing/unit, command, and CAF-wide (Department of National Defence, 2018a). The StF health promotion program also includes mental wellbeing resources that would fit into different levels of intervention, such as individual stress management training, training for leaders and those in supervisory roles to intervene and support members within their units, and awareness campaigns to reduce stigma and promote a healthier culture within the broader organization (Department of National Defence, 2018b, 2021).

Study purpose and hypotheses

The purpose of the current study was to build on previous research with military and civilian populations and examine predictors of both awareness and participation/use of employer-provided mental wellbeing programs and resources offered at different levels of intervention (individual, supervisor/leader, organizational) through a multivariable analysis to examine the influence of a range of predictors with survey data collected from a large representative sample of CAF members. The following hypotheses based on the extant literature guided the analyses:

-

Hypothesis 1

Members who report awareness and participation of mental wellbeing programs and resources will be demographically distinct (e.g., older) from members who are not aware of these programs and resources.

-

Hypothesis 2

Support from leaders will be associated with awareness and use of these programs and resources.

-

Hypothesis 3

Members reporting poorer mental health would report greater use of the mental wellbeing programs and resources given their greater need for support.

Methods

Participants and procedure

Participants were 1,743 Regular Force members who completed the 2021 Your Say Survey (response rate of 38.6%), an anonymous, cross-sectional survey that is administered annually to CAF Regular Force and Primary Reserve members, although only Regular Force members were included in the current report. The purpose of the survey is to provide CAF members with the opportunity to communicate their opinions, attitudes, and experiences on a range of topics that affect military personnel. The survey was administered electronically between 11 March and 26 May, 2021 to a randomly selected sample based on 40 strata, defined by four rank groups (junior and senior non-commissioned members [NCMs], and junior and senior officers) and five organizational commands within the CAF and the Department of National Defence (CA, RCN, RCAF, MPC, or other command). The sample was also selected so that gender and years of service would be proportional to the targeted population.

The first page of the electronic survey provided information on the purpose and voluntary nature of the survey, and members were informed that they were consenting to participate by clicking to continue to the survey questions on the next page. Participants had the choice of completing the survey in either English or French and at any time of day that was convenient. The survey was approved by the Department of National Defence Social Science Research Review Board (SSRRB #1943/20F).

As presented in Table 1, the majority of survey respondents were men (81.7%). Most respondents were between the ages of 25 and 44 years (71.5%), and most reported English as their first official language (72.5%). Two-fifths of respondents were married or in a common-law relationship with dependent children living part-time or full-time in the household (39.1%). Over half of participants were junior NCMs (54.4%), and 35.7% reported that their organizational command was the CA.

Measures

Demographic characteristics

Respondents were asked a wide range of demographic questions. However, only gender, age group, first official language, family status, rank group, and organizational command were considered in the present analysis. For the purposes of the analysis, gender was recoded into woman and not woman (including response options of man, prefer not to answer, and other) and rank assessed whether respondents were officers (i.e., commissioned personnel who plan, organize, and command units and crews on ships or aircrafts) or non-commissioned members (NCMs; that is, any member other than a commissioned officer or officer cadet who is enrolled in the CAF). Family status was assessed based on participants’ marital status (married/common-law versus single [never married, separated, divorced, or widowed]) and whether they had any dependent children under the age of 18 years living in their household part-time or full-time. This resulted in four categories: married with dependent children, married without dependent children, single with dependent children, and single without dependent children.

Leadership support

Participants reported the frequency (i.e., never, seldom, sometimes, often, or always; don’t know) to which the leadership in their unit encourages members to seek help for stress-related problems, with responses grouped into three categories: never/seldom, sometimes, and often/always.

Mental health status

Participants were asked to rate their current mental health status using a 5-point scale (poor, fair, good, very good, or excellent), with responses grouped into three categories: poor/fair, good, and very good/excellent.

Awareness and use of mental wellbeing programs and resources

A list of mental wellbeing programs and resources was presented within the survey. Participants were asked to indicate whether they were aware of each program/resource (i.e., aware, not aware) and, if so, they were then asked whether they had participated in or used the program/resource (i.e., used/participated, not used/not participated). The mental health programs and resources used in the present analysis are described in the following section.

Mental wellbeing programs and resources for the CAF

A wide range of mental wellbeing programs and resources are available to members under the Canadian Armed Forces – Veterans Affairs Canada (CAF-VAC) Joint Suicide Prevention Strategy and the Suicide Prevention Action Plan (Government of Canada, 2017), and the overarching Total Health and Wellness Strategy (Department of National Defence, 2022). Some key mental wellbeing resources include health promotion programs, such as Stress: Take Charge and Mental Fitness and Suicide Awareness, and some broader mental health awareness campaigns. These three initiatives represent efforts to promote positive mental health at the individual, unit leader, and organizational levels within the CAF. Thus, these were selected for examination in the current study from among the many mental wellbeing programs and resources available to CAF members.

Stress: Take Charge is a stress management course, which teaches participants about stress in a military context and builds their resilience through self-awareness, behaviour changes and skill-building (Department of National Defence, 2018b). The course “emphasizes the process by which stress occurs, personal perception of what is stressful, and how to incorporate stress management strategies as one means to create a healthy lifestyle” (Born et al., 2015, p. 2). Mental Fitness and Suicide Awareness is designed for military leaders or members in supervisory roles, which can include NCMs and officers. The course provides training on building resilience, reducing stigma, and practicing suicide intervention using the “Ask, Care, Escort” (ACE) model (Department of National Defence, 2018b). Mental health awareness campaigns include a variety of in-person or virtual activities designed to raise awareness and address misconceptions about mental health among CAF members more broadly, such as Mental Health Week activities in the first full week of May each year (e.g., Department of National Defence, 2023). Past Mental Health Week activities have included panel discussions and information sessions, webinars, and social media messaging for the overall community (e.g., Department of National Defence, 2021).

Statistical analyses

All analyses were completed with the Complex Samples module of SPSS v. 26 to account for the stratified sampling design, and the data were weighted to the CAF population to ensure the results would be generalizable to the population. Six multivariable logistic regressions were conducted to predict awareness and use/participation for each of the three mental wellbeing programs and resources separately (i.e., Stress: Take Charge, Mental Fitness and Suicide Awareness, mental health awareness campaigns). Demographic and military characteristics, and leader support, were entered as explanatory variables for program/resource awareness. Self-reported mental health was added as an explanatory variable for program/resource use/participation, and these analyses were restricted to those respondents who had indicated that they were aware of the program or resource. All variables were entered in the models simultaneously. Data were screened for errors and missing values before proceeding with analyses. No errors were identified, and there was a limited amount of missing data per variable used in each regression (i.e., less than 15% of the appropriate sample after filters were applied). The minimum number of cases with complete data for the planned regressions was 1,199 for the regression predicting participation in Stress: Take Charge! The regressions for program participation were expected to have smaller samples, as respondents were not asked about participation if they indicated they were not aware of a given program. Given the minimal amount of missing data, large sample sizes and adequate statistical power, listwise deletion was used for these regressions. Regression outputs were examined to ensure the assumptions of logistic regression were met (e.g., adequate case-to-variable ratio, absence of multicollinearity). A Type I error rate of 5% was adopted for these analyses, and adjusted odds ratios were calculated for significance tests, demonstrating the magnitude of each effect.

Results

Most Regular Force members reported that their mental health was good (32.5%; 95% CI = 29.8, 35.3) or excellent/very good (23.9%; 95% CI = 21.5, 26.4), although 43.6% (95% CI = 40.7, 46.6) indicated that they were experiencing poor or fair mental health at the time of survey administration in 2021. Two-thirds of members (65.7%; 95% CI = 62.7, 68.6) reported that leaders in their unit often/always encourage members to seek help for stress-related problems. Results pointed to generally high levels of awareness of mental wellbeing programs and resources, with 81.8% (95% CI = 79.3, 84.0) of Regular Force members indicating they were aware of Stress: Take Charge!, 90.8% (95% CI = 88.9, 92.4) reporting they were aware of Mental Fitness and Suicide Awareness, and 90.8% (95% CI = 88.8, 92.4) reporting awareness of mental health awareness campaigns. In contrast to high levels of awareness of mental wellbeing programs and resources, levels of use were somewhat more modest, with only 37.8% (95% CI = 34.7, 41.0) of Regular Force members who were aware of Stress: Take Charge! indicating they had used it, 54.5% (95% CI = 51.5, 57.5) of those who were aware of Mental Fitness and Suicide Awareness reporting they had used it, and 46.3% (95% CI = 43.3, 49.4) of those who were aware of mental health awareness campaigns reporting they had participated in them.

Mental wellbeing program and resource awareness

The results of the three logistic regressions examining awareness of the mental wellbeing programs and resources (Stress: Take Charge!, Mental Fitness and Suicide Awareness, and mental health awareness initiatives) on demographic and military characteristics and support from leaders can be found in Table 2.

Awareness of the Stress: Take Charge! program was significantly associated with gender, age, family status, command, and support from leaders. Women and those 35 years and older were more likely to be aware of the program than those that do not identify as women and those 34 years and younger, with the older group having 2.7 times the odds of being aware than the younger group. Those members who were married or common-law and had dependent children were more likely to be aware of this program than those who were single and had no dependent children. Members of the MPC were more likely to be aware of the program than RCN members and members from Other commands. Finally, those who reported their leadership as often/always encouraging members to seek help for stress-related problems were more likely to be aware of the program than those reporting their leadership as never/seldom encouraging this.

Age, family status, and support from leaders were all associated with awareness of the Mental Fitness and Suicide Awareness program. Those 35 years and older had 2.2 times the odds of being aware of the program than their younger cohorts, with members who were married or common-law and had dependent children also being more likely to be aware of this program than those who were single and had no dependent children. Those who reported their leadership as often/always encouraging members to seek help for stress-related problems were more likely to be aware of the program than those reporting their leadership as sometimes or never/seldom encouraging this. While the Wald F test for command was significant, none of the individual comparisons examining MPC against each of the other commands were significant. This indicates that the difference(s) was/were likely between two commands that did not include MPC. In examining the 95% confidence intervals, it appears likely that the differences were between CA compared to RCN and CA compared to Other commands; however, these comparisons were not tested.

Awareness of the third mental wellbeing initiative examined in this study (i.e., a collection of mental health promotion activities and campaigns designed to raise awareness and address misconceptions about mental health) was significantly associated with age, first official language, command, and support from leaders. Those 35 years and older and those who reported French as their first official language were more likely to be aware of these activities than those 34 years and younger and those who reported English as their first official language. Members of the MPC were also more likely to be aware of these activities than members of the RCN, the RCAF, and members from Other commands. Finally, those who reported their leadership as often/always encouraging members to seek help for stress-related problems were more likely to be aware of these activities than those reporting their leadership as sometimes or never/seldom encouraging this.

Mental wellbeing program and resource use

The results of the three logistic regressions examining use of, and participation in, the mental wellbeing programs and resources (Stress: Take Charge!, Mental Fitness and Suicide Awareness, and mental health awareness initiatives) on demographic and military characteristics, support from leaders, and self-rated mental health can be found in Table 3.

Reporting having used the Stress: Take Charge! program was significantly associated with age, first official language, rank, and command. Those 35 years and older and those who reported French as their first official language were more likely to have used the program than those 34 years and younger and those who reported English as their first official language. Similarly, NCMs were more likely to report having used the program than officers. Finally, members of the MPC were more likely to report using the program than members of the RCN.

Age, rank group, command, and self-rated mental health were all associated with reporting having used the Mental Fitness and Suicide Awareness Training program. Those 35 years and older and NCMs were more likely to have used the program than those 34 years and younger and officers. The program was reported as being used more by members of MPC than members from the RCN, the RCAF, and members from Other commands. Those whose self-reported mental health was poor/fair were more likely to have used the Mental Fitness and Suicide Awareness Training program than those who reported their mental health as excellent/very good.

Reporting having participated in CAF mental health awareness initiatives was associated with gender, support from leaders, and self-rated mental health. Women were more likely than those that do not identify as women to have participated in these initiatives. Additionally, those who reported their leadership as often/always encouraging members to seek help for stress-related problems were more likely to have participated than those reporting their leadership as sometimes or never/seldom encouraging this. Finally, those who reported their mental health was poor/fair were more likely to have participated in CAF mental health awareness initiatives than those whose self-reported mental health was excellent/very good.

Discussion

Key findings and implications

The purpose of the current study was to identify predictors of awareness and use of three mental wellbeing programs and resources among CAF members: an individual stress management course, training for unit leaders to support their subordinates and intervene when necessary, and CAF-wide mental health awareness campaigns. Although most of the sample reported good to excellent mental health, almost half of members reported poor to fair mental health, which likely reflects the significant mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic at the time (e.g., WHO, 2022a). The context of the pandemic may also help to explain why most members reported that leaders often/always encouraged members to seek help for stress-related problems. The reported mental health needs highlight the importance of offering mental wellbeing programs. The current results point to generally high awareness of the programs and resources, although their use (among those who were aware of them) was comparatively modest, in line with other CAF survey results regarding awareness and participation in health promotion programs (Gottschall, 2022).

Consistent with the hypotheses, a number of demographic and military characteristics were associated with both awareness and use. In particular, older members were generally more likely to report awareness and participation compared to younger members across the programs and resources studied, which is consistent with previous research on awareness in military samples (Gottschall, 2022; Thériault et al., 2016). Adapting outreach and communication strategies to fit this demographic group (i.e., young members) could help with uptake. For example, greater use of social media and technological tools rather than traditional health education courses may be beneficial. It was notable that the only regression in the current study where age did not predict participation was for the mental health awareness campaigns, which can involve a variety of activities, including social media messaging, a medium generally adapted more readily by younger people. While program delivery style was not directly measured in the current work, this finding suggests that future research should explore the method of program delivery and its effect on program use.

Married/common-law members with children were also more likely to report awareness and use of the two health promotion programs, Stress Take Charge! and Mental Fitness and Suicide Awareness, compared to single members with no children. This is consistent with previous research on awareness of health promotion programs among RCN personnel (Gottschall, 2022), where married members were more aware of the RCN Health and Wellness Strategy and individual health promotion programs than their single counterparts. These findings may be linked to the reported age differences given younger members are generally more likely to be single. However, this would not account for all the observed differences in program awareness and use given that age was included in the analysis. Another possible explanation is that individuals who are married, and similarly those with dependents, feel a greater sense of responsibility in their lives, recognizing that maintaining their own health is not just beneficial to themselves, but necessary for the added benefit and protection of their dependents. This increased sense of responsibility may lead these married members to be more likely to seek out and use wellness programs.

Additionally, women were more likely to report awareness and use for some programs and resources, which may be expected given previous findings regarding awareness in the CAF (Thériault et al., 2016) and in the civilian literature (Hall et al., 2017; Robroek et al., 2009). This finding may be associated with the fact that women are more willing to seek out health care services in general (Oleski et al., 2010) and may thus be more willing to seek out mental wellness resources available in the workplace.

Command was often significantly associated with awareness and use across the programs and resources examined. RCN personnel often had lower odds ratios compared to personnel from MPC. Previous survey research with CAF members has also indicated that the RCN had lower awareness of the overall StF health promotion program compared to members in the RCAF (Thériault et al., 2016), and survey research with a sample of exclusively RCN personnel indicated that overall awareness levels were lower than those reported for the overall CAF using other survey data (Gottschall, 2022). RCN members face several stressors associated with Naval life, including long periods away at sea, shiftwork, long hours, and interrupted sleep. Given these unique demands, it may be beneficial to explore ways to better reach these members with health promotion efforts. This could include matching health promotion course and event scheduling to sailing schedules and bringing these events to the members where they work so they have easier access to these resources, as suggested by a participant in a recent qualitative study with RCN members (Frank et al., 2023).

Greater awareness and/or use of mental wellbeing programs and resources among MPC personnel (relative to other commands) may have resulted from the proximity to, or engagement in, personnel policy and program development by such personnel, due to the nature of their occupation. Indeed, MPC is responsible for the overall personnel management of the CAF, which includes the provision of training and education and support to CAF personnel and their families, and many of the overarching policies and programs supporting this mission are developed under MPC.

While no differences were observed in the awareness of mental wellbeing programs and resources by rank group, results showed that NCMs were more likely to have participated in them. Results of past studies have pointed to an association between lower/non-officer rank and mental health problems among CAF members (e.g., Zamorski & Boulos, 2014). Greater use of mental wellbeing programs and resources among NCMs may therefore have resulted from higher levels of need for such programs and resources in this group.

Greater awareness and use of the mental wellbeing programs and resources among Francophone personnel compared to Anglophone personnel are difficult to interpret but may reflect geographical differences and the positive influence of a supportive health environment, given overall improvements to mental health services available to military members in Quebec, a Francophone province (CBC News, 2014, February 12). Importantly, leadership can play a significant role in influencing the health environment. As noted above, leadership that is supportive of help-seeking is believed to contribute to reduced stigma around help-seeking and increased use of mental wellbeing resources (Adler et al., 2014). Indeed, the significant association between leaders encouraging help-seeking and awareness of mental wellbeing resources, as well as participation in mental health awareness campaigns, was consistent with this hypothesis and with previous civilian research linking workplace wellness program participation with perceived support from supervisors (Santos, 2019). Although leaders encouraging help-seeking was not directly linked to participation for the two health education courses, participation was impossible without awareness, which was linked to leader support for all three resources. The overall pattern of results highlights the important role that leaders, or those in supervisory roles, can play in disseminating information to their subordinates about resources and creating conditions that are favourable to participation (e.g., Mattke et al., 2013; Santos, 2019).

Finally, the significant association between poorer self-reported mental health and mental wellbeing program and resource use was hypothesized given previous research (e.g., Lee et al., 2020). This suggests that members accessed relevant resources when they needed them, which is encouraging. However, given the focus of health promotion efforts on prevention, this finding also indicates that more could be done to connect with members before they reach the point where they are experiencing poor mental health. The current findings regarding demographic and military characteristics linked to awareness and participation can be used to identify members that could be important targets for outreach efforts, and the suggestions provided in this discussion to reach these members could be explored further. The findings linking leader support to mental wellbeing awareness, as well as participation in mental health awareness campaigns also provides a clear indication of the important role that leaders can play in these efforts.

Strengths, limitations and future directions

The current study fills a gap in the literature by identifying predictors of mental wellbeing program and resource awareness and use within a military environment. The results are based on analyses with a large sample, and the data were weighted for analysis to ensure the sample was representative of the CAF population in terms of key demographic and military characteristics. However, the cross-sectional survey data cannot show causal relationships and may reflect potential reporting biases based on non-response and social desirability. The current results are also based on secondary analyses of existing survey data that were collected for a different purpose, which limited the variables that could be examined.

It is important to note that health promotion can include a range of activities, of which personal skill development and health education is only one (WHO et al., 1986). Canada’s Defence Team Total Health and Wellness Strategy includes a variety of initiatives to promote balance between work, personal, and individual health needs (physical, mental, and spiritual). The strategy takes a holistic approach to health promotion and recognizes a range of determinants of health (Department of National Defence, 2022). For example, it includes a line of effort devoted to cultivating a positive work environment consistent with the National Standard of Canada for Psychological Health and Safety in the Workplace (Canadian Standards Association, & Bureau de normalisation du Québec, 2013). The current results regarding awareness and use of three specific mental wellbeing programs and resources may help to inform efforts to increase the reach and uptake of broader health promotion initiatives.

Of course, it is not enough to reach participants, these programs and resources would also need to be effective to successfully improve the health and wellbeing of military members, and the current study results do not address effectiveness. However, a program evaluation of the Stress Take Charge! course showed promising results, with participants improving their stress management knowledge and abilities (Born et al., 2015). A broader situational assessment of the overall StF health promotion program is also underway to examine if the program is addressing key health needs in the CAF population and is consistent with best practices (e.g., Gottschall, 2019). Engaging in a process of continual improvement is recommended to ensure that the CAF’s health promotion efforts, including mental wellbeing programs and resources, are achieving their objectives and improving the health and wellbeing of military members.

Conclusion

Results of this analysis have helped shed light on key variables associated with the awareness and use of mental wellbeing programs and resources among CAF Regular Force personnel. While overall awareness of the programs and resources that were considered was generally high among personnel, significant variations were noted across subgroups. Specifically, awareness of all three mental wellbeing programs and resources was higher for older members who reported their leadership encouraged members to seek help for stress-related problems. Married members and those belonging to MPC also reported higher awareness of the two programs (Stress: Take Charge! and Mental Fitness and Suicide Awareness). Recognizing these subgroup differences is an important step toward developing strategies to address factors that might be contributing to disparities in program awareness across segments of the CAF population. The role of leaders in this regard is especially critical, given the positive influence their messaging and behaviours have been found to have on the perceptions of their personnel in both this and past studies (Adler et al., 2014). Overall, participation and use of these mental wellbeing programs and resources was higher for older members, NCMs, those belonging to MPC, and those who reported their mental health as poor/fair. This last point indicates that the population that requires the training most (those with poor mental health) appears to be accessing it. However, these programs are designed as part of a broader health promotion strategy, with an intention to reach all members, and not just those already experiencing mental health challenges. As such, it would be beneficial for the CAF to ensure the messaging and promotion of these programs and resources allows for a broader reach to all members.

Lastly, although the current study was conducted on a population of military members, many of the strategies identified in this work are generalizable to civilian occupational settings. For instance, the importance of leadership in influencing the health environment can be adopted by managers in most work settings, through encouraging help-seeking, as well as awareness and use of mental wellbeing resources. Similarly, this work demonstrates that civilian workplaces could potentially reach younger employees through adapting their outreach and tools to include greater use of social media and technology. Finally, although some of the findings are more military-specific (e.g., differences in program awareness and use across military command), future research with civilian populations could benefit from exploring the impact of organizational structures and potentially sub-cultures within organizations on awareness and participation.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available and are owned by the Government of Canada. Researchers must follow appropriate procedures to be provided access by the Government of Canada.

The survey was approved by the Department of National Defence Social Science Research Review Board (SSRRB #1943/20F).

References

Adler, A. B., Saboe, K. N., Anderson, J., Sipos, M. L., & Thomas, J. L. (2014). Behavioral health leadership: New directions in occupational mental health. Current Psychiatry,16, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-014-0484-6

Bensa, K., & Sirok, K. (2023). Is it time to re-shift the research agenda? A scoping review of participation rates in workplace health promotion programs. Environmental Research and Public Health,20, 2757. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032757

Bloznalis, S. (2022). Human workplace index: The evolution of mental health and wellbeing at work. Workhuman, Massachusetts, USA. Retrieved September 20, 2023, from https://www.workhuman.com/blog/human-workplace-index-the-evolution-of-mental- health-and-well-being-at-work/

Born, J., Lee, J. E. C., Dubiniecki, C., & Pierre, A. (2015). Summary report on the 2011–2012 evaluation of the ‘Stress: Take Charge!’ course. Surgeon General Report. SGR-2015- 001. Department of National Defence.

Canadian Standards Association, & Bureau de normalisation du Québec (CSA Group/BNQ) (2013). Psychological health and safety in the workplace– Prevention, promotion, and guidance to staged implementation (CSA Publication No. CAN/CSAZ1003– 13/BNQ9700–803/2013). Retrieved May 3, 2018, from https://www.healthandsafetybc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/CAN_CSA-Z1003-13_BNQ_9700−803_2013_EN.pdf

CBC News (2014). Quebec soldiers’ access to mental health care among fastest in Canada. Retrieved September 30, from https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/quebec-soldiers-access-to-mental-health-care-among-fastest-in-canada-1.2532990

Cramer, R. J., & Kapusta, N. D. (2017). A social-ecological framework of theory, assessment, and prevention of suicide. Frontiers in Psychology,8, 1756. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01756

Crum-Cianflone, N. F., Powell, T. M., Leard Mann, C. A., Russel, D. W., & Boyko, E. J. (2016). Mental health and comorbidities in U.S. military members. Military Medicine, 181(6), 537–545. https://doi.org/10.7205/MILMED-D-15-00187

Department of National Defence. (2018a). Balance: The Canadian Armed Forces physical performance strategy.

Department of National Defence. (2018b). Social Wellness. Retrieved September 8, 2023, from https://www.canada.ca/en/department-national-defence/services/benefits-military/health-support/staying-healthy-active/social-wellness.html

Department of National Defence. (2021). Defence Team Mental Health Week– May 3–9. Retrieved September 8, 2023, from https://www.canada.ca/en/department-national-defence/campaigns/covid-19/mental-health/mental-health-week-2021.html

Department of National Defence. (2022). Defence Team Total Health and Wellness Strategy. Retrieved March 4, 2022, from https://www.canada.ca/en/department-national-defence/corporate/reports-publications/total-health-and-wellness-strategy.html

Department of National Defence. (2023). Surgeon General message– Mental Health Week 2023. Retrieved September 8, 2023, from https://www.canada.ca/en/department-national-defence/maple-leaf/defence/2023/05/surgeon-general-message-mental-health-week-2023.html

Fikretoglu, D., Sharp, M., Adler, A. B., Bélanger, S., Benassi, H., Bennett, C., Bryant, R., Busuttil, W., Cramm, H., Fear, N., Greenberg, N., Heber, A., Hosseiny, F., Hoge, C. W., Jetly, R., McFarlane, A., Morganstein, J., Murphy, D., O’Donnell, M., & Pedlar, D. (2022). Pathways to mental health care in active military populations across the five-eyes nations: An integrated perspective. Clinical Psychology Review,91, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2021.102100

Frank, C., Gottschall, S., & D’Agata, M. (2024). Work-life conflict among Royal Canadian Navy personnel: Challenges to sustaining work-life balance and solutions to mitigate work-life conflict (Director General Military Personnel Research and Analysis Scientific Report DRDC-RDDC-2024-R091). Defence Research and Development Canada.

Goldenberg, I., & Lee, J. E. C. (2020). COVID-19 Defence Team Survey: Top-line findings (Director General Military Personnel Research and Analysis Scientific Report DRDC- RDDC-2020-R084). Defence Research and Development Canada.

Gottschall, S. (2019). Health promotion delivery staff survey. Part I: Course characteristics, suggestions, and comments (Director General Military Personnel Research and Analysis Letter Report DRDC-RDDC-2019-L338). Defence Research and Development Canada.

Gottschall, S. (2020). Assessing the Canadian Armed Forces—Veterans Affairs Canada (CAF—VAC) Joint Suicide Prevention Strategy: CAF member awareness, perceptions, and other potential indicators of implementation and effectiveness (Director General Military Personnel Research and Analysis Scientific Report DRDC-RDDC-2020-R108). Defence Research and Development Canada.

Gottschall, S. (2022). Health promotion in the Royal Canadian Navy: Select results from the Royal Canadian Navy Resilience Survey (RCNRS) (Director General Military Personnel Research and Analysis Letter Report DRDC-RDDC-2022-L173). Defence Research and Development Canada.

Government of Canada. (2017). Canadian Armed Forces and Veterans Affairs Canada joint suicide prevention strategy. Government of Canada. Retrieved September 20, 2023, from https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2017/mdn-dnd/D2-392-2017-eng.pdf

Hall, J. L., Kelly, K. M., Burmeister, L. F., & Merchant, J. A. (2017). Workforce characteristics and attitudes regarding participation in worksite wellness programs. American Journal of Health Promotion,31(5), 391–400. https://doi.org/10.4278/ajhp.140613-QUAN-283

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. (2018). Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Seattle, WA: IHME. Retrieved September 20, 2023, from https://www.healthdata.org/sites/default/files/files/policy_report/2019/GBD_2017_Booklet.pdf

Lee, J., Coulthard, J., Morrow, R., Skomorovsky, A., Williams, L., & Saravanamuthu, G. (2020). Experiences of ill/injured military personnel and their families during military to civilian transition: Use and perceptions of transition programs and services. (Director General Military Personnel Research and Analysis Letter Report DRDC-RDDC-2020-L011). Defence Research and Development Canada.

Mattke, S., Kapinos, K., Caloyeras, J. P., Taylor, E. A., Batorsky, B., Liu, H., Van Busum, K. R., & Newberry, S. (2015). Workplace wellness programs: services offered, participation, and incentives. RAND Health Quarterly,5(2), 7.

Mattke, S., Liu, H., Caloyeras, J. P., Huang, C. Y., Van Busum, K. R., Khodyakov, D., & Shier, V. (2013). Workplace wellness programs study: Final report. RAND Corporation.

National Defence and the Canadian Armed Forces. (2023). Strengthening the Forces: The CAF’s health promotion program. Retrieved September 30, 2023, from http://cmp-cpm.mil.ca/en/health/caf-members/health-promotion.page

Oleski, J., Mota, N., Cox, B. J., & Sareen, J. (2010). Perceived need for care, help seeking, and perceived barriers to care for alcohol use disorders in a national sample. Psychiatric Services,61(12), 1223–1231. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.2010.61.12.1223

Robroek, S. J., van Lenthe, F. J., van Empelen, P., & Burdorf, A. (2009). Determinants of participation in worksite health promotion programmes: a systematic review. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity,6, 26. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-6-26

Ryde, G. C., Gilson, N. D., Burton, N. W., & Brown, W. J. (2013). Recruitment rates in workplace physical activity interventions: characteristics for success. American Journal of Health Promotion,27(5), e101–e112. https://doi.org/10.4278/ajhp.120404-LIT-187

Santos, E. (2019). Introducing the Workplace Well-Being Program Implementation Model: A model to inform the establishment of organizational well-being programs; University of Pennsylvania: Philadelphia, PA, USA. Retrieved September 20, 2023, from https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/228110725.pdf

Sareen, J., Cox, B. J., Afifi, T. O., Stein, M. B., Belik, S.-L., Meadows, G., & Asmundson, G. J. G. (2007). Combat and peacekeeping operations in relation to prevalence of mental disorders and perceived need for mental health care: Findings from a large representative sample of military personnel. Archives of General Psychiatry,64(7), 843–852. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.64.7.843

Sears, J. M., Edmonds, A. T., Hannon, P. A., Schulman, B. A., & Fulton-Kehoe, D. (2022). Workplace wellness program interest and barriers among workers with work-related permanent impairments. Workplace Health Safety,70, 348–357. https://doi.org/10.1177/21650799221076872

Stevelink, S. A. M., Jones, M. M., Hull, L., Pernet, D., MacCrimmon, S., Goodwin, L., MacManus, D., Murphy, D., Jones, N., Greenberg, N., Rona, R. J., Fear, N. T., & Wessely, S. (2018). Mental health outcomes at the end of the British involvement in the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts: A cohort study. European Journal of Psychotraumatology,213(6), 690–697. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2018.235

Thériault, F. L., Gabler, K., & Naicker, K. (2016). Health and Lifestyle Information Survey of Canadian Armed Forces personnel 2013/2014– Regular Force report. B.A. Strauss & J. Whitehead (Eds.), Ottawa, Canada: Department of National Defence.

World Health Organization. (2021). Suicide worldwide in 2019: Global health estimates. Geneva, Switzerland. Retrieved September 20, 2023, from https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240026643

World Health Organization. (2022a). World mental health report; Transforming mental health for all. Geneva, Switzerland. Retrieved September 20, 2023, from https://archive.hshsl.umaryland.edu/handle/10713/20295

World Health Organization, Health and Welfare Canada, & Canadian Public Health Association. (1986). Ottawa charter for health promotion. Retrieved September 29, 2023, from https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/phac-aspc/documents/services/health-promotion/population-health/ottawa-charter-health-promotion-international-conference-on-health-promotion/charter.pdf

Yan, Y., Hou, J., Li, Q., & Yu, N. X. (2023). Suicide before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review with meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health,20(4), 3346. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043346

Zamorski, M.A., & Boulos, D. (2014), The impact of the military mission in Afghanistan on mental health in the Canadian Armed Forces: a summary of research findings. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 5(1). https://doi.org/10.3402/ejpt.v5.23822

Zamorski, M. A., Rusu, C., & Garber, B. G. (2014). Prevalence and correlates of mental health problems in Canadian Forces personnel who deployed in support of the mission in Afghanistan: Findings from postdeployment screenings, 2009–2012. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry,59(6), 319–326. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371405900605

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Statements and Declarations

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Therrien, M.E., Gottschall, S., Wang, Z. et al. Awareness and use of Canadian Armed Forces mental wellbeing programs and resources among Regular Force personnel. Curr Psychol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-06607-z

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-06607-z