Abstract

The use of prosthetic mesh to augment suture repair of large paraoesophageal hernias is widespread but controversial. Our aim was to identify the risk of mesh-specific complications from a large series of consecutive patients undergoing hiatal hernia repair augmented with a lightweight polypropylene mesh (TiMesh) over a 12-year period. A case series review of patients who have had prosthesis-reinforced hiatal repair with TiMesh between February 2005 and October 2017. Pre-operative, intra-operative, and post-operative data were collected for all patients undergoing hiatal repair. In total, 393 patients had TiMesh augmented hiatal repair between February 2005 and October 2017. There were no intraoperative mesh-specific complications. Mesh was explanted in one patient (1/393, 0.25%) who underwent emergency paraoesophageal hernia repair complicated by sepsis. Asymptomatic mesh erosion was found in two patients (2/393, 0.51%) at endoscopy 3 and 9 years following surgery, respectively. No cases of oesophageal or hiatal strictures were identified. From our large series, albeit without routine endoscopic and radiological follow-up, we demonstrate acceptably low rates of mesh-related complications. We identified two cases of asymptomatic erosion during 393 TiMesh repairs, and the rate of mesh-specific complications in this patient series is low. This unit will continue to perform selective TiMesh hiatal repair in cases where a suture repair only is felt to be inadequate at the time of surgery. For the purposes of patient consent and ongoing discussion, we report the risk of mesh erosion and mesh explantation to be 0.51% and 0.25%, respectively.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The use of prosthetic mesh to augment suture repair of large paraoesophageal hernias is widespread but controversial. Several meta-analyses have demonstrated that crural reinforcement with non-absorbable mesh increases the durability of repair of a large hiatus hernia [1,2,3,4,5]. More recent meta-analyses that include randomised controlled trials only have shown no durability benefit when TiMesh is used [6,7,8]. Surgeon surveys in the USA and Europe indicate preparedness by surgeons to utilise both absorbable and non-absorbable mesh to augment hiatal repair [9,10,11]. The risk of mesh-related complications provides an additional tempering influence on the universal uptake of mesh augmentation. Mesh-specific complications appear infrequent but may be catastrophic [12,13,14]. Our aim was to identify the risk of mesh-specific complications from a large series of consecutive patients undergoing hiatal hernia repair augmented with a lightweight polypropylene mesh (TiMesh) (PFM Medical, Koln, Germany) over a 12-year period. We hypothesise that mesh augmentation of sutured hiatal repair is possible to be performed with acceptable short-term mesh-specific complications.

Patients and Methods

A single unit case series review of patients undergoing hiatal hernia repair was undertaken. For the purposes of our ongoing audit, patients were divided into (1) elective paraoesophageal hernia repair, (2) emergency paraoesophageal hernia repair, (3) elective fundoplication, and (4) revision hiatal repair. All patients undergoing prosthesis-reinforced hiatal repair with TiMesh between February 2005 and October 2017 were identified. Pre-operative, intra-operative, and post-operative data were collected for all patients undergoing hiatal repair. Patients were routinely followed up at 1 month and as required thereafter. Delayed complication rates and outcomes of interest were identified on a review of case notes. The primary outcome of interest was the rate of mesh-specific complications, namely mesh fixation–related injuries, mesh erosion, oesophageal or hiatal strictures and stenosis, and mesh explantation. Routine endoscopic and radiological follow up was not performed in this cohort. Patients were seen in our clinic 1 month post-operatively and then as clinically required. No long-term symptomatic or quality-of-life data is presented. Categorical variables were presented as counts and percentages, and continuous variables were expressed as a median and range. This study was approved by the Northern Sydney Local Health District Human Research Ethics Committee (2022/ETH02380).

Operative Technique

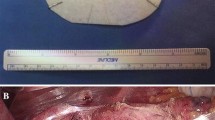

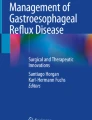

Our operative technique has previously been reported [15, 16]. All operations were performed by the senior authors or trainees under their supervision. The hernia sac was dissected from its mediastinal attachments using ultrasonic shears (ultrasonic coagulating shears, Ethicon Endosurgery Inc., Cincinnati, OH, USA). A posterior sutured hiatoplasty was performed with interrupted polyester sutures (0 Ethibond Ethicon, Johnson & Johnson, Cincinnati, OH, USA) placed 1 cm apart. In cases where the hiatal aperture was particularly large, the hiatal pillars were attenuated, or hiatal closure was performed under tension, and a posterior onlay mesh reinforcement was performed. Onlay mesh reinforcement was performed with TiMesh (PFM Medical, Köln, Germany) and fixed with helical screws (ProTack 5 mm; Covidien, Mansfield, MA, USA). The mesh was cut to size. Typically, the configuration is a rectangular piece measuring 3 × 4 cm with a shallow concavity superiorly to confirm with the hiatal aperture. The mesh was fixed to the hiatal repair, ensuring that the mesh did not come into contact with the posterior aspect of the distal oesophagus (Fig. 1). The mesh did not extend anteriorly beyond the posterior cruroplasty. Fixation screws were, therefore, not placed anterior to the hiatal aperture. A posterior partial (Toupet) fundoplication was then performed routinely.

Results

A total of 393 patients underwent TiMesh augmented hiatal repair between February 2005 and October 2017. Patient characteristics are summarised in Table 1. The median age for patients undergoing paraoesophageal hernia was 71 years of age (range 31–93), with a preponderance of women. Patients undergoing fundoplication for gastro-oesophageal reflux were younger, with a median age of 53 (range 16–83). The predominant indication for the use of TiMesh was for paraoesophageal hernia repair. Mesh was used less frequently in patients undergoing hiatal repair and fundoplication for gastro-oesophageal reflux.

There were no mesh-specific complications in the perioperative period, and particularly, no instances of fixation-associated injury. In this series, seven patients underwent up front open repair, six who had previously undergone open hiatal repair and one patient with an acute gastric obstruction. Four patients underwent laparoscopic converted to open repair: two who had undergone previous open hiatal repair, one converted for splenic capsular bleed, and another obese patient due to difficult posterior hiatal access. Mesh was explanted in one patient (1/393, 0.25%) who underwent emergency paraoesophageal hernia repair complicated by sepsis following an oesophageal leak. Mesh erosion was incidentally found in two patients (2/393, 0.51%) at 3 years (41 months) and 9 years (115 months) following surgery, respectively. Both patients underwent endoscopy at other institutions, one for investigation of iron deficiency anaemia and the other for post-fundoplication symptoms. Neither patient required mesh explantation, and both remain asymptomatic. No cases of oesophageal or hiatal strictures were identified. Perioperative complications are presented in Table 1. There were two perioperative deaths. An 88-year-old woman undergoing elective repair with Ti-Mesh suffered an oesophageal injury at the cardioesophageal junction due to traction with a nylon sling. This was recognised and repaired at the time of surgery. The patient underwent a thoracotomy for an empyema presumably related to an ongoing leak from the repair. The patient refused further active treatment and succumbed. An 82-year-old woman underwent repair with Ti-Mesh for acute gastric volvulus. The patient returned to the operating theatre 12 days postoperatively for gastroscopy to investigate postoperative dysphagia. The patient failed to regain consciousness and ultimately succumbed to a basal ganglia infarct.

Discussion

The increasingly widespread use of prosthetic mesh to reinforce hiatal repair has been demonstrated in recent surveys of American and European gastrointestinal surgeons [7,8,9]. These studies have also highlighted the large diversity in practice and approach to using prostheses at the hiatus, where the indication for use, mesh type, configuration, and placement technique vary. The advantage of prosthetic mesh in preventing hiatal hernia recurrence is not conclusively established. Five meta-analyses examining mesh-reinforced hiatal repair versus suture-only repair demonstrated a lower recurrence rate in patients undergoing a non-resorbable mesh-reinforced repair at short- to medium-term follow up [1,2,3,4,5]. However, more recent meta-analyses involving randomised controlled trials have not shown this benefit [6,7,8]. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials demonstrated no benefit of mesh augmentation with respect to recurrence rates, both in the short and long term. Quite reasonably, the authors conclude that ‘as both techniques delivered comparable clinical outcomes, a suture technique for primary hiatus hernia repair is simpler and should be recommended’ [6]. It is worth noting that the prosthetic materials used in the included studies varied, and some may no longer be in widespread use. This is particularly the case with expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE), which was shown to decrease recurrence rates in one randomised trial [17]. There are two prospective randomised trials comparing TiMesh augmentation to primary closure [18, 19], with 5-year follow up recently published for one trial [20]. Neither study reported a benefit in recurrence rate with TiMesh repair compared to primary suture repair.

Reports of complications with various types of mesh and fixation techniques illustrate that mesh repair at the hiatus is not without risk. Cardiac vascular injury may occur at the time of mesh fixation, resulting in bleeding or cardiac tamponade [20,21,22,23]. Mesh erosion may require foregut resection, which may be technically difficult and result in compromised patient quality of life and nutrition [12,13,14, 24, 25]. It must be noted that various mesh types have different physical characteristics that influence tissue incorporation and propensity to erode [26], and not all case reports of complications identify the type of mesh utilised. While mesh-related complications appear to be rare, their true incidence is unknown. Complications such as these probably suffer from natural publication and reporting bias against poor outcomes [27]. Secondly, complication reporting has primarily been the focus of case reports and small case series, which lack denominators through which incidence can be calculated.

In a survey of European surgeons, approximately one-third of the 165 respondents had seen one or more complications related to mesh use in hiatal repair during their careers [11]. From a survey of SAGES members, the authors propose the mesh-related complication rate to be approximately 2 to 4 patients per 1000, reporting an incidence for erosion and strictures of 0.27% and 0.20%, respectively [9]. The authors recognise this should be taken only as an estimate of real-world results as the respondents’ data could not be verified, but it does appear to align with other reports of mesh complications. A systematic review of the literature calculated the incidence of oesophageal erosion and dense fibrosis causing oesophageal stenosis as 0.2% and 0.5%, respectively [2].

Our reported rate of mesh erosion of 0.51% appears to be consistent with previously reported rates of mesh complications. In both cases, the patients were asymptomatic and did not require mesh explantation. We believe our erosion cases reflect inadequate fixation of the mesh to the diaphragm, resulting in incomplete incorporation. Our single case of explantation occurred in a patient who had undergone laparoscopic repair of an acute hernia. A subsequent laparotomy was performed to address an unrecognised oesophageal perforation, and at that time, the mesh was explanted. There were no cardiac or vascular injury related complications relating to fixation screws in this series. Cardiac injuries are likely to be avoided if mesh is placed posteriorly over the hiatal repair, obviating the need to place screws anteriorly.

The most obvious limitation in a study such as this is the lack of long-term symptomatic and objective follow-up with either contrast study or endoscopy. Routine anatomical follow-up with either of these modalities outside the context of a clinical trial on a cohort this large would prove challenging from a logistical viewpoint. With that in mind, we are unable to report rates of asymptomatic hernia recurrence or mesh erosion.

Conclusion

Whether there is a role for non-absorbable mesh in repairing hiatal defects remains to be seen. In the absence of supportive data, the use of suture repair should remain the standard of care for large hiatus hernias. Whether particularly large defects or defects closed under tension stand to benefit from mesh augmentation should be the subject of further studies. We have used TiMesh lightweight polypropylene mesh as our standard hiatal augmentation for selected cases since 2002. While there are various configurations and materials used in mesh-augmented repair, we have limited our use of mesh over the study period to a posterior onlay repair using TiMesh. From our large series, albeit without routine endoscopic and radiological follow-up, we demonstrate, we believe, acceptably low rates of mesh-related complication. Two cases of asymptomatic mesh erosion were incidentally identified in the course of 393 TiMesh repairs, and mesh was explanted in one patient. For the purposes of patient consent and ongoing discussion, we report the risk of mesh erosion and mesh explantation to be 0.51% and 0.25%, respectively.

References

Castelijns PSS, Ponten JEH, van de Poll MCG, Nienhuijs SW, Smulders JF (2018) A collective review of biological versus synthetic mesh-reinforced cruroplasty during laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication. J Minim Access Surg 14:87–94

Furnee E, Hazebroek E (2013) Mesh in laparoscopic large hiatal hernia repair: a systematic review of the literature. Surg Endosc 27:3998–4008

Huddy JR, Markar SR, Ni MZ et al (2016) Laparoscopic repair of hiatus hernia: does mesh type influence outcome? A meta-analysis and European survey study. Surg Endosc 30:5209–5221

Sathasivam R, Bussa G, Viswanath Y et al (2019) ‘Mesh hiatal hernioplasty’ versus ‘suture cruroplasty’ in laparoscopic para-oesophageal hernia surgery; a systematic review and meta-analysis. Asian J Surg 42:53–60

Zhang C, Liu D, Li F et al (2017) Systematic review and meta-analysis of laparoscopic mesh versus suture repair of hiatus hernia: objective and subjective outcomes. Surg Endosc 31:4913–4922

Petric J, Bright T, Liu DS, Wee Yun M, Watson DI (2022) Sutures verses mesh-augmented hiatus hernia repair: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ann Surg 275(1):e45-51

Memon MA, Memon B, Yunus RM, Khan S (2016) Suture cruroplasty versus prosthetic hiatal herniorrhaphy for large hiatal hernia: a meta-analysis and systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Ann Surg 263(2):258–266

Tam V, Winger DG, Nason KS (2016) A systematic review and meta-analysis of mesh vs suture cruroplasty in laparoscopic large hiatal hernia repair. Am J Surg 211:226–238

Frantzides CT, Carlson MA, Loizides S et al (2010) Hiatal hernia repair with mesh: a survey of SAGES members. Surg Endosc 24:1017–1024

Pfluke JM, Parker M, Bowers SP, Absun HJ, Smith DC (2012) Use of mesh for hiatal hernia repair: a survey of SAGES members. Surg Endosc 26:1843–1848

Furnee EJ, Smith CD, Hazebroek EJ (2015) The use of mesh in laparoscopic large hiatal hernia repair: a survey of European surgeons. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 25:307–311

Nandipati K, Bye M, Yamamoto SR, Pallati P, Lee T, Mittal SK (2013) Reoperative intervention in patients with mesh at the hiatus is associated with high incidence of esophageal resection - a single-center experience. J Gastrointest Surg 17:2039–2044

Parker M, Bowers SP, Bray JM et al (2010) Hiatal mesh is associated with major resection at revisional operation. Surg Endosc 24:3095–3101

Stadlhuber RJ, Sherif AE, Mittal SK et al (2009) Mesh complications after prosthetic reinforcement of hiatal closure: a 28-case series. Surg Endosc 23:1219–1226

Hazebroek E, Ng A, Yong DH, Berry H, Leibman S, Smith GS (2008) Clinical evaluation of laparoscopic repair of large hiatal hernias with TiMesh. ANZ J Surg 78:914–917

Gordon AC, Gillespie C, Son J, Polhill T, Leibman S, Smith GS (2018) Long-term outcomes of laparoscopic large hiatus hernia repair with nonabsorbable mesh. Dis Esophagus 31:1–6

Frantzides CT, Madan AK, Carlson MA, Stavropoulos GP (2002) A prospective, randomized trial of laparoscopic polytetrafluoroethylene (PTEE) patch repair vs simple cruroplasty for large hiatal hernia. Arch Surg 137:649–652

Oor JE, Rok DJ, Koetje JH et al (2018) Randomized clinical trial comparing laparoscopic hiatal hernia repair using sutures versus sutures reinforced with non-absorbable mesh. Surg Endosc 32:4579–4589

Watson DI, Thompson SK, Devitt PG et al (2015) Laparoscopic repair of very large hiatus hernia with sutures versus absorbable mesh versus nonabsorbable mesh: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg 261:282–289

Watson DI, Thompson SK, Devitt PG et al (2020) Five year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial of laparoscopic repair of very large hiatus hernia with sutures versus absorbable mesh versus nonabsorbably mesh. Ann Surg 272(2):241–247

Makarewicz W, Jaworski L, Bobowicz M et al (2012) Paraesophageal hernia repair followed by cardiac tamponade caused by ProTacks. Ann Thorac Surg 94:e87-89

Thijssens K, Hoff C, Meyerink J (2002) Tackers on the diaphragm. Lancet 360(9345):1586

Zugel N, Lang RA, Kox M, Hüttl TP (2009) Severe complication of laparoscopic mesh hiatoplasty for paraesophageal hernia. Surg Endosc 23:2563–2567

De Moor V, Zalcman M, Delhaye M, Nakadi IE (2012) Complications of mesh repair in hiatal surgery: about 3 cases and review of the literature. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 22:e222-225

Fenton-Lee D, Tsang C (2010) A series of complications after paraesophageal hernia repair with the use of Timesh: a case report. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 20:e95-96

De Maria C, Burchielli S, Salvadori C et al (2016) The influence of mesh topology in the abdominal wall repair process. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater 104:1220–1228

Tatum RP, Shalhub S, Oelschlager BK, Pellegrini CA (2008) Complications of PTFE mesh at the diaphragmatic hiatus. J Gastrointest Surg 12:953–957

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the Northern Sydney Local Health District Human Research Ethics Committee (2022/ETH02380).

Disclosures

All authors have reviewed and are in agreement with the content of the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This manuscript has not been published previously and is not under consideration for publication elsewhere.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Drane, A., Bhimani, N., Sarich, P. et al. Hiatal Repair Using Non-absorbable Mesh: Short-Term Outcome Analysis of 393 Consecutive Cases with a Focus on Prosthetic-Specific Complications. Indian J Surg (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12262-024-04147-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12262-024-04147-1