Abstract

Atopic dermatitis often begins in infancy and follows a chronic course of exacerbations and remissions. The etiology is complex and involves numerous factors that contribute to skin barrier defect and inflammation. In the Middle East, the burden of atopic dermatitis is understudied. Epidemiological data specific to the Gulf region are scarce but reveal a prevalence of up to about 40% in the United Arab Emirates. Region-specific factors, such as the climate and the frequency of consanguineous marriages, may affect atopic dermatitis incidence, prevalence, and evolution over time. A panel of experts predominantly from the United Arab Emirates analyzed the evidence from published guidelines, and considered expert guidance and local treatment practices to develop clear recommendations for the management of atopic dermatitis in the United Arab Emirates. They encourage a systematic approach for the diagnosis and treatment, using disease severity scores and quality-of-life measurement tools. Treatment recommendations take into consideration both established therapies and the approved systemic biologics dupilumab and tralokinumab, and the Janus kinase inhibitors baricitinib, upadacitinib, and abrocitinib.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a common skin disease that is often associated with co-morbidities such as respiratory allergy and susceptibility to the overgrowth of certain microorganisms (e.g., Staphylococcus aureus, herpes simplex virus). |

Major pathogenetic factors operative in AD include type 2 inflammation, a disturbed skin barrier function, a dysbalanced cutaneous microbiome, and a perturbed neuro-immune axis. |

While AD is usually diagnosed clinically, solid and robust criteria exist, which confirm the diagnosis and allow differentiation of AD from other forms of dermatitis/eczema (e.g., contact dermatitis, seborrheic dermatitis, nummular dermatitis); in addition, physician-based and patient-based scoring systems exist for assessing disease severity and the impact of AD on the quality of life of affected people. |

Mild AD can usually be managed by the regular use of skin care measures (i.e., moisturizers, emollients, humectants), as well as topical therapies including corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, and phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitors. |

Moderate-to-severe AD often requires systemic approaches that include conventional therapies (phototherapy, systemic corticosteroids, cyclosporine, methotrexate), biologic agents that directly inhibit the major mediators of type 2 inflammation (dupilumab, tralokinumab, lebrikizumab), and small molecules (Janus kinase inhibitors) that interfere with the immunopathogenic signal transduction cascade. |

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a frequently encountered, non-contagious inflammatory disease of the skin characterized by pruritic eczematous lesions [1, 2]. The condition often begins in infancy and follows a chronic course of exacerbations and remissions. The etiology of AD is complex and involves numerous factors that contribute to skin barrier defect and inflammation, including genetics, altered immune responsiveness, microbiology, environment, and (neuro)immunity [3].

Many individuals with AD, particularly those with a family history, have atopic diathesis [4]; that is, a hereditary predisposition to develop, alone or together, diseases such as atopic dermatitis, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, asthma, and food allergy. All these diseases are characterized by type 2 inflammation and a predominance of T cells producing interleukin (IL)-4, IL-5 and, particularly, IL-13 [4, 5].

In addition, patients with AD have (1) an impaired skin barrier caused by loss of function mutations or downregulation of barrier proteins (e.g., filaggrin and claudin); (2) an altered cutaneous microbiome that is less diverse than that of healthy persons; (3) an enhanced exposure to noxious substances (e.g., pollutants, irritants, and pathogenic microorganisms); and (4) and increased levels of the additional neuroimmune factor IL-31, which has been shown to promote growth of itch-related sensory nerves [3, 6,7,8]. Currently, it is not entirely clear whether these individual factors occur independently of each other or influence each other.

In a large European cohort of individuals with a history of moderate-to-severe AD, 45% continued to be living with moderate-to-severe disease despite current treatments, and, in the majority, AD significantly impacted their quality of life (QoL) [9]. In the Middle East, the burden of AD is understudied, with most data from Saudi Arabia. Using appropriate assessment tools, the studies demonstrate that dermatologic diseases, predominantly AD, adversely influence the QoL of affected individuals and their families [10, 11]. Furthermore, studies from the Middle East and other countries established a relationship between AD and non-atopic comorbidities such as diabetes, hypertension, and psychiatric conditions, namely depression, stress, and anxiety [5, 11,12,13,14].

According to key epidemiological studies, the incidence and prevalence of AD in both children and adults varies across the world [15]. In the multinational Epidemiology of Children with Atopic Dermatitis Reporting on their Experience (EPI-CARE) study, conducted in 65,661 children (aged 6 months to < 18 years) across 18 countries in 2018–2019, the prevalence of diagnosed AD ranged from 2.7% to 20.1% and that of reported AD ranged from 13.5% to 41.9% [16]. Respective prevalence rates for the United Arab Emirates (UAE; N = 958) were 16.7% and 39.1% [16], suggesting that AD is more common in the UAE than in many other countries, likely because consanguinity is not uncommon in the UAE.

Data from older or more diverse populations are more limited. Among 255 undergraduate university students from around the globe (mean age 20.1 years; 12.2% UAE nationals; 21.2% other Middle Eastern and 34.1% Asian) who completed a questionnaire in Ajman, UAE, 14.9% had eczema [17].

Until recently, the therapeutic armamentarium for treating AD consisted primarily of moisturizers, topical anti-inflammatories, phototherapy, and systemic therapies such as immunosuppressants. The availability of novel treatment modalities prompted revisions of management guidelines and expert recommendations globally. Taking into account specific challenges faced by local patients and treatment availability, these consensus recommendations aim to provide practical guidance for the optimal management of AD in the UAE.

Methods

An expert panel comprised of dermatologists, predominantly from the UAE, with expertise in the treatment of AD met on September 5, 2019 to discuss recent advances in the field. Following this initial discussion, a series of follow-up teleconferences and face-to-face meetings were attended by groups of up to 12 dermatologists between June 8, 2022 and November 22, 2023. The objective of these meetings was to develop up-to-date consensus recommendations to aid healthcare providers with the management of AD in the UAE.

Relevant statements from previously published clinical guidance recommendations addressing AD definitions, diagnosis, disease severity, treatment, comorbidities, QoL, and patient education were initially reviewed by a UAE steering committee. Consensus discussions then followed. The final consensus recommendations take into consideration published guidelines and expert guidance on AD, relevant literature published up to March 2023, registered treatments and their respective labels in each emirate, and local treatment practices.

The main sources of evidence included:

-

Atopic dermatitis in adults: An Australian management consensus (2019) [18].

-

Understanding the burden of atopic dermatitis in Africa and the Middle East (2019) [3].

-

Consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (AD) in adults and children (2022) [19].

All discussions were recorded and written up into a full manuscript draft by a professional medical writer. Members of the expert panel reviewed, edited, and commented on the outline and drafts of the manuscript until a final version was reached and approved by all panel members.

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors. Ethical approval was not required.

Recommendations for Evaluation of AD

Definitions and Diagnosis

AD occurs more commonly in children but it also affects many adults. It has an age-specific typical morphology and distribution [20]. Although usually first diagnosed in infancy, AD often goes into remission during childhood; in some cases, AD can persist into adulthood or first develop in adults, taking a heterogeneous clinical course [21]. AD is often associated with an overproduction of immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibodies and a personal and/or family history of allergic conditions such as allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, asthma, and/or food allergies [22].

Given the lack of specific biomarkers for the diagnosis of AD, the diagnosis depends on clinical features. These vary by age, with exudative lesions and seborrhea-like features more common in pediatric patients, and phenotypic features (e.g., lichenification and erythroderma), and hand and foot dermatitis, more common in adults. Children are more likely than adults to have AD of the eyelid, auricular area, and ventral aspect of the wrist, whereas the disease course in adults is more affected by emotions and/or environmental factors [20]. Flexural eczema is common, but not specific to AD [23]. After the onset of AD, many of those affected experience the “atopic march,” the serial development of allergic diseases such as food allergy, asthma, and allergic rhinoconjunctivitis [5]. In addition to this atopic march, AD is associated with a number of comorbidities, including severe bacterial and viral infections (including eczema herpeticum), obesity, cardiovascular disease, and neuropsychiatric disorders (e.g., depression and anxiety) [5]. The presence of elevated IgE levels can also assist with the diagnosis of AD.

Panel members agreed that validated diagnostic criteria by Hanifin and Rajka [24] (Table 1) should be used for the complete evaluation of AD, and to exclude differential diagnoses such as other chronic inflammatory skin conditions (e.g., contact allergic dermatitis, seborrheic dermatitis, and nummular dermatitis), immunodeficiencies associated with eczematoid rashes (e.g., Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome), infectious diseases and infestations (e.g., scabies), and neoplasia (e.g., cutaneous T-cell lymphoma) [1].

Given the chronic relapsing nature of AD, the panel agreed on defining flares as the acute, clinically substantial worsening of signs and symptoms of AD requiring therapeutic intervention with increased strength of anti-inflammatory therapy, or escalation to more potent immunosuppressive treatment, or hospitalization. This also means that intensity scoring should not be used to define disease flares due to the wide inter-individual variability in the level of tolerance of symptoms, particularly pruritus.

In the UAE, patients with AD would first be seen by a general practitioner (GP) or a dermatologist. If seen by a GP, panel members reached consensus on the following criteria that should prompt referral of a patient with AD to a dermatologist or immunologist:

-

The patient experiences frequent flares.

-

The dermatitis does not respond to standard treatment.

-

The dermatitis causes significant distress and is interfering with activities of daily living such as sleep, school, or work.

-

If an allergy is suspected and/or if there are recurrent bacterial or viral infections.

Disease Severity

Disease severity can vary from mild to moderate-to-severe; it is based on clinical features and response to first-line topical therapies and avoidance of irritants and disease triggers (Table 2). The treatment approach for AD should be guided by disease severity and its impact on the individual’s QoL. Additionally, atopic comorbidities (e.g., asthma) and the risk of complications (e.g., recurrent skin infections or eczema herpeticum) should be considered when deciding on the optimal treatment. Due to the discordance between physician- and patient-reported disease severity in AD [25], the panel unanimously agreed that effective communication between patients and physicians should be encouraged to ensure that the management of AD is directed toward the needs of the patient.

The expert panel agreed that serial measurements of disease severity over time, as opposed to a single baseline measurement, provide more robust information about flares and treatment response. With most disease severity and QoL scoring systems designed for the research setting or lacking validation, it can be difficult to select tools that can be routinely used in clinical practice [22]. The expert panel recommended the SCORing Atopic Dermatitis index (SCORAD) [26], the body surface area (BSA) method [22], the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) [27], and the patient-reported Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) [28] for the assessment of disease severity and QoL (Table 3).

The SCORAD index has a maximum score of 103 and assesses the extent and intensity of the disease, combined with subjective symptoms of pruritus and sleep loss [26]. When assessing disease severity, a score of < 25 is considered mild disease, 25–50 is moderate disease and ≥ 50 is severe disease [26].

A simpler way of measuring disease severity, the BSA method uses the “rule of nines” (a chart that divides the body into sections, each representing 9% of the total BSA) [22]. More than 10% BSA affected can be considered moderate-to-severe AD, although the features and location of lesions should also be considered (e.g., facial or genital lesions, or particularly itchy lesions can have a notable effect on the patient’s QoL and should be assigned higher severity) [22].

The EASI, which is scored from 0–72, is a fast-to-administer, validated scoring system for measuring the extent and intensity of the physical signs of AD [27]. According to Hanifin et al. [27], an EASI score of 0 indicates clear or no AD, 0.1 to 1.0 indicates almost clear, 1.1 to 7 indicates mild disease, 7.1 to 21 indicates moderate disease, 21.1 to 50 indicates severe disease, and > 50 indicates very severe disease. However, these cut-off values are not universal. For example, Chopra et al. [29], define AD as clear (score of 0), mild (0.1–5.9), moderate (6.0–22.9), or severe (23.0–72). In addition, the EASI is one of two recommended core instruments for measuring signs in AD clinical trials (the other being SCORAD) [27, 30]. Most recent clinical trials evaluating the efficacy of new treatments in patients with moderate-to-severe AD included patients with an EASI ≥ 16.

The DLQI is a widely used and validated measure of the impact of the disease on the patient’s QoL. It is a 10-item questionnaire that assesses the effects of skin disease over a period of 1 week on symptoms, feelings, daily activities, work/school, personal relationships, and treatment [28]. A score of 0–1 indicates no effect of their skin disease on the patient’s life, 2–5 indicates a small effect on the patient’s life, 6–10 indicates a moderate effect on the patient’s life, 11–20 indicates a very large effect on the patient’s life, and 21–30 indicates an extremely large effect on the patient’s life [31]. A pediatric version of the DLQI, the Children's Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI) questionnaire, is also available for evaluating the impact of AD in children [32].

Based on the established interpretation of these four scores, the panel members agreed that moderate-to-severe AD could be measured by DLQI ≥ 10 points, BSA ≥ 10%, SCORAD ≥ 25 points, and EASI ≥ 7 points.

If DLQI/CDLQI is not used to assess the subjective component of disease severity, a patient account of pruritus can be taken using relatively simple scales. The visual analogue scale (VAS) and the numerical rating scale (NRS) can help patients quantify their pruritus within the last week on a scale from 0 (no itch) to 100 or 10, respectively, (worst imaginable itch) [33]. The validated Investigator Global Assessment scale for Atopic Dermatitis (vIGA-AD) can also be used to categorize the severity of AD based on the overall appearance of the lesions at a given time point using a 5-point scale (0–4) [34, 35]. A score of 0 indicates clear or no AD, 1 indicates almost clear AD, 2 indicates mild AD, 3 indicates moderate AD, and 4 indicates severe AD.

Finally, when determining disease severity, a simplified method to diagnose moderate-to-severe AD could take into consideration other elements including the type of skin lesions (acute, sub-acute, chronic), their location (hands, face, genitals, scalp), the frequency of flares and hospital admissions due to flares, and the impact on QoL [22]. This method should be considered complementary to the aforementioned methods.

There are no validated biomarkers of disease severity in AD. The total serum IgE level has been extensively studied but a meta-analysis by Thijs et al. showed only a moderate correlation between IgE levels and disease severity [36]. Therefore, the expert panel agreed that it should not be used to determine or monitor disease severity, although IgE levels can assist in the diagnosis of AD.

Recommendations for the Treatment of Atopic Dermatitis

General Measures

Unless the impact on QoL is substantial on initial consultation, physicians should optimize general measures and topical therapy before considering systemic medications for AD. However, the presence of comorbidities or increased risk of AD-related complications must also be considered. Moisturizers are the mainstay of AD management as they can improve skin barrier function and reduce the need for anti-inflammatory therapies [3, 19]. Moisturizers contain varying amounts of emollient and humectant that lubricate and soften the skin [2]. Moisturizing is the primary treatment in patients with mild AD and is an important part of disease management in those who have moderate-to-severe AD [2, 19].

Other topical treatments that can enhance the barrier effect include bath oils, shower gels, emulsions, or micellar solutions.

Several environmental factors have been shown to elicit AD flares in adults and children. These include chemical irritants, allergens, microbes, and stress. However, with the exception of pollen, dust mite, animal dander, and tobacco smoke avoidance, there are no evidence-based recommendations for environmental trigger avoidance measures in patients with AD [2, 19].

Topical Therapy

The pharmacological treatment of AD should be approached systematically. Topical anti-inflammatory medications are the first line of treatment and are typically introduced after failure of lesions to respond to adequate skin care. Anti-inflammatory therapies commonly used in the UAE include topical corticosteroids (TCS), topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCI) and the phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor crisaborole. There is not enough evidence from randomized controlled trials to demonstrate the efficacy of topical antihistamines, and their use for the treatment of patients with AD is not recommended because of the risk of absorption and irritant contact dermatitis [2, 19]. Globally and in the UAE, topical antibacterial and antiviral preparations are not generally recommended in the management of AD unless there is evidence of a true infection [2, 19].

The potency of TCS varies and different classifications exist [2, 37]. Potency in relation to the body area to which the agent will be applied should be considered. Sensitive areas such as the face, neck, and skin folds should preferably be treated with mild TCS. For other body areas, mid- to high-potency agents could be used for brief time periods to treat flares then tapered or switched to a lower-potency TCS to avoid or minimize side effects [2, 19]. During long-term use of TCS, patients should be monitored for the most common cutaneous side effects, including skin atrophy, purpura, telangiectasia, striae, focal hypertrichosis, acneiform or rosacea-like eruptions, and tachyphylaxis. While the risk of hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis suppression is low in adults, it increases with prolonged continued use of potent TCS [2].

Tacrolimus ointment and pimecrolimus cream are TCI approved for the treatment of AD in children aged ≥ 2 years and adults, and can be used as steroid-sparing agents on actively affected areas [38]. Skin irritation, such as stinging, burning, itching, and redness, is common at the application site [2, 38]. Initial treatment with TCS should be considered in patients with an acute flare to reduce the risk of these events [2, 19]. TCI may be preferable to TCS in cases of steroid recalcitrance, steroid-induced skin atrophy, after long-term uninterrupted use of TCS, and for sensitive areas of the body [2]. Care must be taken to minimize exposure of skin to sunlight or other sources of ultraviolet light while using TCI. Although systemic absorption of TCI is uncommon, additional care is recommended if TCI are used for an extended period in those with extensive skin involvement, especially when treating children [38].

Crisaborole is a topical phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, approved for the treatment of mild-to-moderate AD in children aged ≥ 3 months and in adults [39]. The efficacy of crisaborole relative to TCS and TCI is unclear, and it appears that it may be similar to that of mild TCS or pimecrolimus [19]; this ointment may therefore be of limited value in patients with more severe disease. Crisaborole should be administered as a thin layer over affected skin. It is generally well tolerated but has been associated with local hypersensitivity reactions, some of which are serious [39].

In recent years, a proactive approach to maintenance involving intermittent application of either TCI or TCS twice- to three-times weekly has proven effective in reducing AD relapses [2, 19]. The recommended regimen for topical treatment with TCS and TCI is:

-

Application 2–3 times weekly at sites prone to recurrence for preventative treatment.

-

In selected patients and at specific body sites, longer treatment durations may be necessary.

Treatment response will likely differ between patients, depending upon disease severity and location. Patients who fail to respond to optimized topical therapy should be evaluated for exacerbating factors (e.g., cutaneous infection, psychiatric or behavioral issues) and for alternative diagnoses (e.g., allergic contact dermatitis). The expert panel agreed with Boguniewicz et al. [22] on the optimal duration of 2–4 weeks of a trial of TCS before an inadequate response can be considered a treatment failure. However, they decided to extend the duration of trial for TCI to 4–6 weeks due to the slower anti-inflammatory effect of TCI and the rarity of side effects in patients treated beyond 4 weeks.

Panel members also agreed on definitions of treatment intolerance and resistance. Intolerance to topical treatment can be defined as a patient’s opinion of worsening lesions after 1–2 weeks of therapy with a new topical treatment, or any difficulty associated with drug application, including pain, burning, or an uncomfortable sensation. Resistance to topical treatment was defined as an unchanged or aggravated clinical score after a minimum of 4 weeks of appropriately dosed and applied treatment, in the absence of an acute adverse reaction.

Adherence to a daily topical regimen can be challenging for some patients. Furthermore, treatment adherence can be impacted by corticophobia (fear of the use of TCS), lack of education and treatment boredom, and concerns related to the black-box warning mandated for TCI by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2005. Appropriate counselling that addresses patient fears and concerns is paramount to treatment adherence and prevention of early discontinuation.

Systemic Therapy

Prior to escalating treatment to systemic therapy, the expert panel agreed on the importance of ascertaining whether failure of topical treatment is due to the severity of the disease (lack of efficacy of topical therapy), incorrect usage (dose/application), intolerance, or lack of adherence to the treatment. The decision to start systemic therapy should then be based on disease severity, impact of AD on the patient’s QoL, and the risks and benefits of systemic therapies for the individual patient. The choice of systemic therapy depends on several patient-related factors, including age and the presence of comorbidities. As well as the therapies discussed here, patients with skin infections, such as staphylococcal infections and eczema herpeticum, may require systemic antimicrobial therapy. Additionally, there are other systemic therapies which, according to anecdotal reports, may be of benefit for certain patients (e.g., alitretinoins, interferon gamma, and high-dose immunoglobulin).

Phototherapy

Phototherapy is recommended as second-line treatment or adjuvant therapy in children and adults with moderate-to-severe AD [40]. Although several trials have demonstrated the efficacy of phototherapy in patients with AD, this modality may not be available or practical for many patients in the UAE. Across the country, the most common ultraviolet light used for phototherapy in patients with AD is narrow-band ultraviolet light B (NB-UVB). It is well tolerated by most patients, but adherence to the treatment schedule—often requiring clinic visits 2–3 times weekly—can be difficult. The expert panel agreed that if no response is seen with 12–16 weeks of phototherapy, or if AD recurrently flares during treatment course, a modification to the treatment regimen is recommended.

The incidence of adverse events with phototherapy in AD is considered low [40]. Actinic damage, local erythema and tenderness, pruritus, burning, and stinging are common side effects of phototherapy. Treatment should not be administered with cyclosporine or other systemic treatments (e.g., azathioprine) and should not be initiated in patients receiving TCI as combined use may increase the risk of adverse events.

Systemic Immunomodulating Agents

Until recently, a limited number of options for systemic therapy were available—primarily systemic immunosuppressants. However, several novel systemic agents have become available in recent years for the treatment of moderate-to-severe AD. These include the biologics dupilumab and tralokinumab, and the Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors baricitinib, upadacitinib, and abrocitinib. The most commonly used systemic medications for AD are summarized in Table 4.

In the UAE, mycophenolate and azathioprine are seldom used because they are not approved for the treatment of AD. Furthermore, there is limited evidence to formulate recommendations with these agents and their use is associated with potentially serious side effects. Immunosuppressive therapy in patients with AD has traditionally been cyclosporine and methotrexate. Although cyclosporine is not indicated for AD in children [41], when used in this population it has shown real-world effectiveness and guidelines recommend it as a treatment option for children and adults with acute flares or severe AD refractory to conventional topical treatment [19]. The panel agreed that treatment should not exceed a 2-year continuous regimen, and careful monitoring for potential severe side effects must be performed. Use should be initiated with care in elderly patients and restricted to those with disabling AD and normal renal function [41].

There are very limited efficacy and safety data on the use of methotrexate for the treatment of AD. However, many continue to use it with good response and the adverse event profile does not appear to vary from that reported in patients taking methotrexate for other indications. Hepatotoxicity and teratogenicity are the main areas of safety concern [19].

Glucocorticoids are other immunosuppressants widely used in AD despite a paucity of controlled trials. While very effective in the treatment of AD when used appropriately, they are also associated with significant short- and/or long-term side effects that include skin atrophy, weight gain, emotional lability, Cushing’s syndrome, osteoporosis, hypertension, and diabetes [19]. Ultimately, the risk/benefit ratio of long-term systemic steroid therapy in AD is unfavorable. These agents should be used only for adults requiring short bouts (bursts) of treatment (1–3 weeks), with use limited to bridging, rescue of flares, anticipation of a major life event, or in patients with severe AD. If to be prescribed, treatment should be robust and short, rather than weak and prolonged.

With greater understanding of the molecular pathogenesis of AD focusing on barrier dysfunction, cutaneous and systemic immune abnormalities, and the role of the microbiome, novel targeted therapies have been developed. These include biologic therapies, with a slow but pathway-specific mode of action, and small molecules with rapid but broader activity than biologics. Biologics may be more adapted for long-term control of AD, whereas small molecules can provide rapid relief in pruritus and inflammation and are well tolerated. However, the benefit–risk ratio of small molecules remains a significant pharmacovigilance issue [42].

IL-4 and IL-13 are major drivers of human type 2 inflammatory diseases, such as AD. These cytokines rely on JAK for signaling. Currently, recommended biologics that decrease many of the mediators of type 2 inflammation are the recombinant fully human immunoglobulin (Ig)G4 monoclonal antibody dupilumab, which inhibits IL-4 and IL-13 signaling (for patients with AD aged ≥ 6 months) [43], the fully human IgG4 monoclonal antibody tralokinumab, which specifically binds to IL-13 and inhibits its interaction with IL-13 receptors (for patients with AD aged ≥ 12 years) [44], and the soon-to-be approved high-affinity IgG4 monoclonal antibody lebrikizumab that targets interleukin-13 (for patients with AD aged ≥ 12 years) [45]. Recommended small molecules are the oral selective JAK inhibitors, baricitinib, which inhibits JAK1 and JAK2 (for patients with AD aged ≥ 2 years) [46], and upadacitinib and abrocitinib, which inhibit JAK1 (for patients with AD aged ≥ 12 years) [47, 48].

Dupilumab has shown efficacy and safety in large randomized, placebo-controlled phase IIb and III trials. It is effective in treating AD skin signs and symptoms, while providing overall improvement of QoL, as monotherapy or in combination with TCS in patients with moderate-to-severe AD and an inadequate response to TCS, or when used as monotherapy in those with intolerance to TCS [49,50,51]. Treatment response was maintained for at least 1 year of continuous treatment in 65% of patients, and the drug had acceptable safety [51]. Dupilumab was also shown to have acceptable safety and sustained efficacy for up to 4 years in an open label study [52]. The most common adverse events with dupilumab were infections, injection site reactions, and headache, with a higher incidence of conjunctivitis and injection site reactions in patients receiving dupilumab compared with those receiving placebo [50,51,52,53]. In addition, paradoxical, mainly asymptomatic, head and neck erythema has been reported with dupilumab treatment [54]. Dupilumab is also approved as an add-on maintenance treatment for adults and children aged 6 years and older with moderate-to-severe asthma characterized by an eosinophilic phenotype or with oral corticosteroid dependent asthma [55].

Tralokinumab was effective and safe for controlling the signs and symptoms of moderate-to-severe AD as monotherapy in adult patients with an inadequate response or medical contraindication to TCS or in combination with “as needed” TCS in phase III, randomized, placebo-controlled trials [56, 57]. In patients receiving tralokinumab as monotherapy, efficacy was maintained at 1 year in 51–60% of patients depending on the outcome [57]. Tralokinumab dosed every 4 weeks may be an option for patients who achieve clear or almost clear skin or EASI-75 at week 16 with initial two-weekly dosing [56, 57]. In these trials, tralokinumab also significantly improved patient-reported outcomes such as QoL, itch, and sleep [56,57,58]. Similar clinical and patient-reported outcome results were observed in a phase III adolescent trial [59]. The long-term efficacy (4 years) of tralokinumab in adults with moderate-to-severe AD has also been demonstrated in an ongoing open-label extension trial [60]. Adverse events were generally mild or moderate, non-serious, and occurred with a similar frequency in placebo-treated patients, although conjunctivitis, injection site reactions, headache, and upper-respiratory tract infections were more common with tralokinumab [56, 57]. Integrated analysis of safety data collected over a period of up to 4.5 years (N = 2693) revealed a safety profile and pattern of adverse events that were consistent with the placebo-controlled data, with no new safety signals identified [61].

Lebrikizumab was effective and safe as monotherapy in adolescents and adults with moderate-to-severe AD and an inadequate response or medical contraindication to topical therapies in randomized, placebo-controlled trials [62], with responses maintained for periods of up to 1 year [63]. Similarly, lebrikizumab was associated with improved outcomes at 16 weeks in adolescents and adults with moderate-to-severe AD when administered with TCS compared with TCS alone [64]. Adverse events were generally mild or moderate in severity and did not lead to treatment discontinuation, and most frequently included conjunctivitis and nasopharyngitis [63, 65]. At the time of writing, lebrikizumab was approved for treating moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis in adults and adolescents aged 12 years or more with a body weight of > 40 kg in the European Union [45], but was not yet available in the UAE.

Baricitinib is an oral selective JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor that has demonstrated efficacy and safety as monotherapy in patients with moderate-to-severe AD and an inadequate response to, or intolerance of, topical therapy (TCS or TCI) in randomized, placebo-controlled studies [66, 67]. Monotherapy with the drug rapidly reduced itch and other symptoms, resulting in an improvement in the QoL of patients with AD [66], and the efficacy and safety of monotherapy and combination therapy were maintained for at least 1 year [68, 69].

Upadacitinib is an oral selective JAK1 inhibitor that has shown efficacy and safety as monotherapy in patients with moderate-to-severe AD and an inadequate response or medical contraindication to topical therapy (TCS or TCI) [70], or prior topical or systemic therapy [71], in randomized, placebo-controlled studies, with maintained efficacy and tolerability at 1 year [72]. In a randomized head-to-head trial, upadacitinib demonstrated statistically significantly superior short-term (week 16; primary time point) efficacy and numerical greater week 24 efficacy versus dupilumab, as measured by ≥ 75% improvement in EASI score (EASI 75), in patients with moderate-to-severe AD and an inadequate response or medical contraindication to topical therapy (TCS or TCI), or prior systemic therapy [73].

Abrocitinib is also an oral selective JAK1 inhibitor. In randomized, placebo-controlled trials, abrocitinib as monotherapy demonstrated efficacy and safety, as well as improving symptoms of itch, and QoL, at 12 weeks in patients with moderate-to-severe AD and an inadequate response or medical contraindication to topical therapy (TCS or TCI), or prior systemic therapy [74,75,76]. Abrocitinib was more efficacious than dupilumab for the co-primary endpoints of a 4-point or higher improvement in Peak Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale (PP-NRS4) at week 2, achieved by 48% and 26% of patients, respectively, and ≥ 90 improvement in EASI score (EASI 90) response at 4 weeks, achieved by 29% and 15% of patients, respectively. The secondary endpoint of EASI 90 response at 16 weeks also demonstrated greater efficacy for abrocitinib, with a significantly larger proportion of patients (54%) reaching the endpoint versus the dupilumab group (42%) [77].

JAK inhibitors require regular patient monitoring, are associated with an increased risk of herpes and serious infection, and may be associated with adverse major cardiovascular events, venous thromboembolism, or malignancy; however, the risk of these latter events appears low [72, 78, 79]. Indeed, a meta-analysis of 35 randomized phase III clinical trials including 20,651 patients with a mean age of 38.5 years found that the use of JAK inhibitors was not associated with an increased risk of major adverse cardiovascular events plus all-cause mortality, or venous thromboembolism compared with placebo/active comparators over a mean follow-up of 4.9 months [80]. Nevertheless, careful consideration should be given to the risks of treatment in patients with active, chronic, or recurrent infections (including tuberculosis), or malignancy, and in those at risk of venous thromboembolism. Risk factors to consider in determining the patient's risk for venous thromboembolism before initiating JAK inhibitors include: older age; obesity; a medical history of venous thromboembolism; prothrombotic disorder; use of combined hormonal contraceptives or hormone replacement therapy; patients undergoing major surgery; or prolonged immobilization. Treatment should be discontinued and patients should be evaluated promptly, followed by appropriate treatment if features of venous thromboembolism present. In addition, JAK inhibitors should only be used in patients aged 65 years or above, those at increased risk of major cardiovascular problems (such as heart attack or stroke), those who smoke or have done so for a long time in the past, and those at increased risk of cancer if no suitable treatment alternatives are available [81].

Time to response with systemic therapies can vary according to the systemic agent used, as well as disease severity, disease location, and patient-specific factors. When considering treatment with systemic therapies, the optimal duration of treatment before an inadequate response can be considered a treatment failure is:

-

Cyclosporine: 6 weeks [40]

-

Dupilumab: 16 weeks [82]

-

Tralokinumab: 16 weeks [44]

-

Baricitinib: 8 weeks [46]

-

Upadacitinib: 12 weeks [48]

-

Abrocitinib: 12 weeks [47]

Treatment failure despite appropriate dose, duration, and adherence to a therapeutic agent may be defined by either (1) inadequate clinical improvement; or (2) failure to achieve stable long-term disease control; or (3) the presence of ongoing impairment (e.g., pruritus, pain, loss of sleep, and poor QoL) while on treatment; or (4) unacceptable adverse events or poor tolerability experienced with the treatment.

The efficacy of all the biologics and JAK inhibitors now available for AD is greater than that historically reported with cyclosporine or other immunomodulatory agents. Currently, few clinical trials have directly compared the novel systemic treatments for AD, and the panel agreed that the choice of biologic/JAK inhibitor will depend on the patient. Factors to consider include: patient preference, as some patients (and physicians) may prefer oral to injectable therapy; and the presence of any risk factors for adverse events specific to each agent.

Measuring Treatment Success

Success of systemic treatment can be defined by achievement of minimal disease activity according to agreed outcome measures. These measures should include at least one clinician-rated outcome and at least one patient-reported outcome, and should be measured using both subjective and objective criteria (Table 5). Outcome measures include DLQI and/or BSA and/or SCORAD and/or EASI and/or NRS (for pruritis/itch, pain, sleep) [83, 84]. The panel recommend that prior to achieving these goals, clinically meaningful improvement should be measured after 6–16 weeks (depending on treatment) against baseline. When treatment success is achieved, appropriate maintenance therapy can be commenced.

The Atopic Dermatitis Control Tool (ADCT) is another brief, validated, practical, and simple tool that patients can use to evaluate the control of their AD [85]; it can be used to facilitate meaningful patient–physician discussions.

To reflect patient preferences and shared decision-making when deciding how to measure treatment success, we suggest that patients/caregivers should be asked to choose one or more AD features that are most important to them that can be used. This will allow the physician to choose the most appropriate patient-reported outcome measures (that reflect the patient’s/caregiver’s choice of AD features) to measure treatment success. The physician should also choose at least one objective clinical measure that gives an overall picture of the patient’s disease (EASI, SCORAD, or BSA) for ongoing assessments.

Medication Strategy for AD

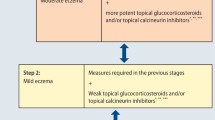

The panel agreed to develop treatment algorithms based on AD classification to aid with the systematic and pragmatic management of the disease (Figs. 1 and 2).

Management of mild AD. a Choice of treatment is based on the age of the patient and sensitivity of area being treated (face, neck, and skin folds should preferably be treated with mild TCS or TCI). For other body areas, mid- to high-potency agents could be used for brief time periods to treat flares then tapered or switched to a lower-potency TCS to avoid or minimize side effects. During long-term use of TCS, patients should be monitored for the most common cutaneous side effects, including skin atrophy, purpura, telangiectasia, striae, focal hypertrichosis, acneiform or rosacea-like eruptions, and tachyphylaxis. While the risk of hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis suppression is low in adults, it increases with prolonged continued use of potent TCS. TCI may be preferable to TCS in cases of steroid recalcitrance, fear of TCS therapy, steroid-induced skin atrophy, after long-term uninterrupted use of TCS, and for sensitive areas of the body. b Crisaborole is recommended as a suitable topical treatment for children. Use of potent TCS is not recommended for children. AD atopic dermatitis; BSA body surface area; DLQI dermatology life quality index; EASI Eczema Area and Severity Index; SCORAD SCORing atopic dermatitis; NB-UVB narrowband ultraviolet B; TCI topical calcineurin inhibitors; TCS topical corticosteroids

Management of moderate-to-severe AD. a Recommended systemic agents are cyclosporine, dupilumab, tralokinumab, baricitinib, upadacitinib, and abrocitinib (see Table 4). Choice of systemic therapy should be based on a risk–benefit assessment for each patient and take such factors as patient age and comorbidities into consideration. Tralokinumab or dupilumab may influence the immune response against helminth infections so treatment may need to be delayed or interrupted until any such infections are resolved [38, 43]. When considering Janus kinas inhibitor therapy (baricitinib, upadacitinib, and abrocitinib), careful consideration should be given to the risks of treatment in patients with active, chronic or recurrent infections, including tuberculosis, or malignancy. Risk factors to consider in determining the patient's risk for venous thromboembolism include older age, obesity, a medical history of venous thromboembolism, prothrombotic disorder, use of combined hormonal contraceptives or hormone replacement therapy, patients undergoing major surgery or prolonged immobilisation. Treatment should be discontinued and patients should be evaluated promptly, followed by appropriate treatment if features of venous thromboembolism present. b In children, the only approved systemic options are dupilumab, which is approved for those aged 6 months to 11 years with severe AD, or phototherapy, although access can be limited in the UAE; for adolescents with moderate-to-severe AD, dupilumab, tralokinumab, upadacitinib, and abrocitinib, all of which are approved for those aged 12 years, and phototherapy, are recommended. In women considering or who are pregnant, the preferred systemic options are phototherapy and dupilumab, for which the potential benefit must justify the potential risk to the foetus. The following treatments are contraindicated/not recommended for pregnant women or during breast-feeding: cyclosporine, tralokinumab, baricitinib, upadacitinib, and abrocitinib. c Treatment periods before reassessment for efficacy: Cyclosporine: 6 weeks, Dupilumab: 16 weeks, Tralokinumab: 16 weeks, Baricitinib: 8 weeks, Upadacitinib: 16 weeks, Abrocitinib: 12 weeks. AD atopic dermatitis; BSA body surface area; DLQI dermatology life quality index; EASI Eczema Area and Severity Index; SCORAD SCORing atopic dermatitis; NB-UVB narrowband ultraviolet B; TCI topical calcineurin inhibitors; TCS topical corticosteroids

Recommendations for Treatment During Pregnancy and Breast-Feeding

During pregnancy, non-potent TCS can be used, with TCI preferably used on the face and intertriginous areas and on abdominal, breast, and thigh skin, where the risk of striae formation increases with excessive use of TCS [19].

If topical treatments are not sufficient to control AD, phototherapy is a suitable treatment during pregnancy and breast-feeding [19]. Most other systemic treatments have not been adequately evaluated in these patients, and are therefore either contraindicated, or not recommended during pregnancy, or for those planning pregnancy, or if the patient is breast-feeding [41, 44, 46,47,48]. Use of cyclosporine (pregnancy category C) [41] during pregnancy should be carefully considered by the treating physician, but the panel considers that it may be a safe alternative for patients refractory to conventional treatment. Women of childbearing potential must use effective contraception during and for at least 1 week after baricitinib treatment and 4 weeks after upadacitinib or abrocitinib; no such recommendations are available for tralokinumab. Limited data are available concerning the use of dupilumab in pregnancy, although animal studies suggest a lack of negative effect of the drug regarding reproductive toxicity [82].

Recommendations on Patient Perspectives

Comorbidities and QoL

Although AD primarily affects the skin, associated atopic and non-atopic comorbid conditions are well documented, reflecting the systemic nature of the disease. Usually developing early, allergic diseases that represent the atopic march (food allergies, asthma, and allergic rhinoconjunctivitis) often follow AD [5]. AD is associated with an increased risk of infections (including Staphylococcus aureus infection and eczema herpeticum), neuropsychiatric disorders (depression, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, anxiety), cancer (lymphoma, leukemia but not other neoplasms), and cardiovascular disease [5, 22, 86]. Prevalence data from the Middle East highlight the psychological distress of patients with skin diseases, including AD. A cross-sectional study of Saudi Arabian dermatology patients with psoriasis, vitiligo, AD, acne vulgaris or “other” found that the prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress was 12.6%, 22.1%, and 7.5%, respectively [11]. At least one of these negative emotional conditions was present in 24.4% of the cohort. Those with poor QoL were 3.5 times more likely to suffer from depression, anxiety, and stress. Abolfotouh et al. found comorbidities in 31.4% of patients with skin disease (sebaceous and apocrine gland disorders, pigmentary disorders, eczematous dermatitis, cutaneous infections, papulosquamous disorders [e.g., psoriasis], disorders of the hair follicles and connective tissue and immunological disorders) in central Saudi Arabia [12]. The most common were diabetes and hypertension (43.8% and 47.2%, respectively), followed by heart disease (22.5%), thyroid disease (21.3%), and psychiatric disorders (20.2%). In a study of 414 Iranian patients with various dermatological diseases (psoriasis, pemphigous, vitiligo, eczema, acne, alopecia, mycosis fungoides, or “other”), a majority (51.3%) suffered from psychiatric comorbidities [14].

Patients with AD should be routinely screened for psychological symptoms and QoL impairment. Currently available scales for eliciting information on itch, sleep, impact of AD on daily activity, and persistence of disease should be used when practical. Psychiatric counselling should be provided when appropriate.

Patient Education

The complex interplay of factors that affect disease control in AD may prove difficult to manage for some patients and may negatively impact treatment adherence and outcomes. Patients should be provided with comprehensive education to actively participate in treatment decisions. The expert panel agreed that early and frequent follow-up of patients along with written action plans may promote treatment adherence. In adult patients with moderate-to-severe AD, structured patient education programs have been shown to improve disease severity and QoL [25].

Discussion

This article presents the consensus recommendations of a dermatology expert panel for the management of AD in the UAE. While well-respected international guidelines on the management of patients with AD exist, they do not provide regional or local insights and practical advice for patients in the UAE. Region- or country-specific consensus recommendations are important because they guide clinical practice through evidence-based recommendations while considering available treatment modalities, as well as local practices and challenges. This can be reassuring to local practitioners who might have uncertainties about their treatment approach. Local expert recommendations written by peers may also be more readily accepted and implemented by all local practitioners who care for patients with AD. Given the complexity of the UAE healthcare system and the multiple stakeholders involved, clear, simple, and authoritative recommendations may improve efficiency of care, foster interdisciplinary communication, and help government bodies and third-party payers by providing valid evidence in support of reimbursement claims. From a research perspective, this document shines a light on the paucity of epidemiological and clinical data on AD in the UAE. Region-specific factors—such as the climate and the frequency of consanguineous marriages—may affect AD incidence, prevalence, and evolution over time. The issue of consanguinity is particularly important because family history is the strongest risk factor for AD. A better understanding of local epidemiology could help to more efficiently allocate healthcare resources. Consensus recommendations such as these may assist with the development of much-needed research protocols.

In developing these consensus recommendations, the UAE dermatology expert panel aims to provide an easily accessible guide for AD management. They encourage a systematic approach to the diagnosis and treatment of AD using disease severity scores and QoL measurement tools. Although there may be benefits to providing separate recommendations for moderate and severe AD, as some treatments may be preferred in those with severe AD, such recommendations cannot be supported by head-to-head studies, so they have not been put forward. Treatment recommendations take into consideration both established therapies and recently available systemic agents. Members of the expert panel acknowledge that these recommendations should be used alongside clinical judgement, and they encourage the development of collaborative projects across the UAE to monitor clinical outcomes of the treatment of AD.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

Weidinger S, Novak N. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet. 2016;387:1109–22.

Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Berger TG, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: Management and treatment of atopic dermatitis with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:116–32.

Al-Afif KAM, Buraik MA, Buddenkotte J, et al. Understanding the burden of atopic dermatitis in Africa and the Middle East. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2019;9:223–41.

Novak N, Bieber T. Allergic and nonallergic forms of atopic diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;112:252–62.

Brunner PM, Silverberg JI, Guttman-Yassky E, et al. Councilors of the International Eczema Council. Increasing comorbidities suggest that atopic dermatitis is a systemic disorder. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137:18–25.

Bin L, Leung DY. Genetic and epigenetic studies of atopic dermatitis. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2016;12:52.

Osawa R, Akiyama M, Shimizu H. Filaggin gene defects and the risk of developing allergic disorders. Allergol Int. 2011;60:1–9.

Kantor R, Silverberg JI. Environmental risk factors and their role in the management of atopic dermatitis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2017;13:15–26.

Ring J, Zink A, Arents BWM, et al. Atopic eczema: burden of disease and individual suffering – results from a large EU study in adults. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33:1331–40.

Al-Hoqail IA. Impairment of quality of life among adults with skin disease in King Fahad Medical City. Saudi Arabia J Family Community Med. 2009;16:105–9.

Ahmed AE, Al-Dahmash AM, Al-Boqami QT, Al-Tebainawi YF. Depression, anxiety and stress among Saudi Arabian dermatology patients: cross-sectional study. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2016;16:e217–23.

Abolfotouh MA, Al-Khowailed MS, Suliman WE, et al. Quality of life in patients with skin diseases in central Saudi Arabia. Int J Gen Med. 2012;5:633–42.

AlShahwan MA. The prevalence of anxiety and depression in Arab dermatology patients. J Cutan Med Surg. 2015;19:297–303.

Arbabi M, Zhand N, Samadi Z, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity and quality of life in patients with dermatologic diseases. Iran J Psychiatry. 2009;4:102–6.

Deckers IA, McLean S, Linssen S, et al. Investigating international time trends in the incidence and prevalence of atopic eczema 1990–2010: a systematic review of epidemiological studies. PLoS ONE. 2012;7: e39803.

Silverberg JI, Barbarot S, Gadkari A, et al. Atopic dermatitis in the pediatric population: a cross-sectional, international epidemiologic study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2021;126:417-28.e2.

John LJ, Ahmed S, Anjum F, et al. Prevalence of allergies among university students: a study from Ajman. United Arab Emirates ISRN Allergy. 2014;2014: 502052.

Smith S, Baker C, Gebauer K, et al. Atopic dermatitis in adults: an Australian management consensus. Australas J Dermatol. 2020;61:23–32.

Wollenberg A, Kinberger M, Arents B, et al (2022) EuroGuiDerm guideline on atopic eczema. [cited 2023Feb10]. Available from: https://guidelines.edf.one//uploads/attachments/clbm6nh6x07tw0d3qtyb1ukrt-0-atopic-eczema-gl-full-version-dec-2022.pdf

Yew YW, Thyssen JP, Silverberg JI. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the regional and age-related differences in atopic dermatitis clinical characteristics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:390–401.

Garmhausen D, Hagemann T, Bieber T, et al. Characterization of different courses of atopic dermatitis in adolescent and adult patients. Allergy. 2013;68:498–506.

Boguniewicz M, Alexis AF, Beck LA, et al. Expert perspectives on management of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: A multidisciplinary consensus addressing current and emerging therapies. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5:1519–31.

Jacob SE, Goldenberg A, Nedorost S, Thyssen JP, Fonacier L, Spiewak R. Flexural eczema versus atopic dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2015;26:109–15.

Hanifin JM, Rajka G. Diagnostic features of atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol Suppl (Stockh). 1980;92:44–7.

Heratizadeh A, Werfel T, Wollenberg A, et al. Effects of structured patient education in adults with atopic dermatitis: multicentre randomized controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140:845-53.e3.

Oranje AP. Practical issues on interpretation of scoring atopic dermatitis: SCORAD Index, objective SCORAD, patient-oriented SCORAD and three-item severity score. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2011;41:149–55.

Hanifin JM, Baghoomian W, Grinich E, Leshem YA, Jacobson M, Simpson EL. The eczema area and severity index-a practical guide. Dermatitis. 2022;33:187–92.

Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)–a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:210–6.

Chopra R, Vakharia PP, Sacotte R, et al. Severity strata for Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI), modified EASI, Scoring Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD), objective SCORAD, atopic Dermatitis Severity Index and body surface area in adolescents and adults with atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:1316–21.

Schmitt J, Langan S, Deckert S, et al. Assessment of clinical signs of atopic dermatitis: a systematic review and recommendation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132:1337–47.

Hongbo Y, Thomas CL, Harrison MA, Salek MS, Finlay AY. Translating the science of quality of life into practice: What do dermatology life quality index scores mean? J Invest Dermatol. 2005;125:659–64.

Lewis-Jones MS, Finlay AY. The Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI): initial validation and practical use. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:942–9.

Phan NQ, Blome C, Fritz F, et al. Assessment of pruritus intensity: prospective study on validity and reliability of the visual analogue scale, numerical rating scale and verbal rating scale in 471 patients with chronic pruritus. Acta Derm Venereol. 2012;92:502–7.

Simpson E, Bissonnette R, Eichenfield LF, et al. The Validated Investigator Global Assessment for Atopic Dermatitis (vIGA-AD): the development and reliability testing of a novel clinical outcome measurement instrument for the severity of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:839–46.

Bissonnette R, Simpson E, Eichenfield LF, et al. The vIGA-AD scale for atopic dermatitis: uptake in the past 5 years and position of the International Eczema Council. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2024;38:e291–5.

Thijs J, Krastev T, Weidinger S, et al. Biomarkers for atopic dermatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;15:453–60.

Niedner R. Therapie mit systemischen glukokortikoiden. Hautarzt. 2001;52:1062–71.

European Medicines Agency (2021) Protopic 0.03% ointment - Summary of product characteristics (SPC) [cited 223 Feb 22]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/protopic-epar-product-information_en.pdf

Pfizer Laboratories Div Pfizer Inc. EUCRISA- crisaborole ointment. Prescribing Information. [Cited 2022 July 1]. Available from: https://labeling.pfizer.com/showlabeling.aspx?id=5331

Sidbury R, Davis DM, Cohen DE, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis. Management and treatment with phototherapy and systemic agent. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:327–49.

European Medicines Agency (2013) Sandimmun and associated names - Summary of product characteristics (SPC). [cited 2023 Feb 23]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/referral/sandimmun-article-30-referral-annex-iii_en.pdf

Bieber T. Atopic dermatitis: an expanding therapeutic pipeline for a complex disease. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2022;21:21–40.

European Medicines Agency (2022) Dupixent - Summary of product characteristics (SPC). [cited 2023 Feb 23]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/dupixent-epar-product-information_en.pdf

Medicines.org.uk. Adtralza 150 mg solution for injection in pre-filled syringe – Summary of product characteristics (SPC). 2021 [cited 2022 June 23]. Available from: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/12725/smpc

European Medicines Agency (2023) Ebglyss - Summary of product characteristics (SPC). [cited 2023 Nov 27]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/ebglyss-epar-product-information_en.pdf

Medicines.org.uk Olumiant 4 mg Film-Coated Tablets – Summary of product characteristics (SPC). 2022 [cited 2022 June 23]. Available from: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/7486/smpc

Medicines.org.uk. Cibinqo 200 mg film-coated tablets – Summary of product characteristics (SPC). 2021 [cited 2022 June 23]. Available from: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/12874/smpc

European Medicines Agency. Rinvoq - Summary of product characteristics (SPC). 2022 [cited 2023 Feb 1]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/rinvoq-epar-product-information_en.pdf

Simpson EL, Gadkari A, Worm M, et al. Dupilumab therapy provides clinically meaningful improvement in patient-reported outcomes (PROs): a phase IIb, randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial in adult patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (AD). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:506–15.

Simpson EL, Bieber T, Guttman-Yassky E, et al. Two phase 3 trials of dupilumab versus placebo in atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:2335–48.

Blauvelt A, de Bruin-Weller M, Gooderham M, et al. Long-term management of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis with dupilumab and concomitant topical corticosteroids (LIBERTY AD CHRONOS): a 1-year, randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389:2287–303.

Beck LA, Deleuran M, Bissonnette R, et al. Dupilumab provides acceptable safety and sustained efficacy for up to 4 years in an open-label study of adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23:393–408.

de Bruin-Weller M, Thaçi D, Smith CH, et al. Dupilumab with concomitant topical corticosteroid treatment in adults with atopic dermatitis with an inadequate response or intolerance to ciclosporin A or when this treatment is medically inadvisable: a placebo-controlled, randomized phase III clinical trial (LIBERTY AD CAFÉ). Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:1083–101.

de Wijs LEM, Nguyen NT, Kunkeler ACM, et al. Clinical and histopathological characterization of paradoxical head and neck erythema in patients with atopic dermatitis treated with dupilumab: a case series. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:745–9.

Regeneron. DUPIXENT® (dupilumab) injection, for subcutaneous use. Prescribing information. 2022 [cited 2023 Nov 27]. Available from: https://www.regeneron.com/downloads/dupixent_fpi.pdf

Silverberg JI, Toth D, Bieber T, et al. Tralokinumab plus topical corticosteroids for the treatment of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: results from the double-blind, randomized, multicentre, placebo-controlled phase III ECZTRA 3 trial. Br J Dermatol. 2021;184:450–63.

Wollenberg A, Blauvelt A, Guttman-Yassky E, et al. Tralokinumab for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: results from two 52-week, randomized, double-blind, multicentre, placebo-controlled phase III trials (ECZTRA 1 and ECZTRA 2). Br J Dermatol. 2021;184:437–49.

Langley R, Reich K, Simpson E, et al (2022) Long-term improvements in disease severity, itch, and quality of life after 3 years of tralokinumab treatment in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. Presented at 4th Annual Revolutionizing Atopic Dermatitis (RAD) Conference, Baltimore, Maryland, April 9–11. Poster Presentation #241.

Paller AS, Flohr C, Cork M, et al. Efficacy and safety of tralokinumab in adolescents with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: the Phase 3 ECZTRA 6 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2023;159:596–605.

Blauvelt A, Langley R, Peris K, et al. Continuous tralokinumab treatment over 4 years in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis provides long-term disease control (abstract 4551). Presented at the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV) Congress 2023. Berlin, Germany. 11–14 October. [cited 2024 Jan 15]. Available from: https://eadv.org/wp-content/uploads/scientific-abstracts/EADV-congress-2023/Atopic-dermatitis-eczema.pdf

Reich K, Langley R, Silvestre JF, et al. Safety of tralokinumab for the treatment of atopic dermatitis in patients with up to 4.5 years of treatment: an updated integrated analysis of eight clinical trials. Presented at the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV) Congress 2023. Berlin, Germany. 11–14 October. [cited 2024 Jan 15]. Available from: https://eadv.org/wp-content/uploads/scientific-abstracts/EADV-congress-2023/Atopic-dermatitis-eczema.pdf

Silverberg JI, Guttman-Yassky E, Thaçi D, et al. Two phase 3 trials of lebrikizumab for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2023;388:1080–91.

Blauvelt A, Thyssen JP, Guttman-Yassky E, et al. Efficacy and safety of lebrikizumab in moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: 52-week results of two randomized double-blinded placebo-controlled phase III trials. Br J Dermatol. 2023;188:740–8.

Simpson EL, Gooderham M, Wollenberg A, et al. 2023 Efficacy and safety of lebrikizumab in combination with topical corticosteroids in adolescents and adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a randomized clinical trial (ADhere). JAMA Dermatol. 2023;159:182–91.

Stein Gold L, Thaçi D, Thyssen JP, et al. Safety of lebrikizumab in adults and adolescents with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: an integrated analysis of eight clinical trials. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2023;24:595–607.

Simpson EL, Lacour JP, Spelman L, et al. Baricitinib in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis and inadequate response to topical corticosteroids: results from two randomized monotherapy phase III trials. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:242–55.

Simpson EL, Forman S, Silverberg JI, et al. Baricitinib in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: Results from a randomized monotherapy phase 3 trial in the United States and Canada (BREEZE-AD5). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:62–70.

Silverberg JI, Simpson EL, Wollenberg A, et al. Long-term efficacy of baricitinib in adults with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis who were treatment responders or partial responders: an extension study of 2 randomized clinical trials. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:691–9.

Bieber T, Reich K, Paul C, et al. Efficacy and safety of baricitinib in combination with topical corticosteroids in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis with inadequate response, intolerance, or contraindication to cyclosporine: results from a randomized, placebo-controlled, phase III clinical trial (BREEZE-AD4). Br J Dermatol. 2022;187:338–52.

Guttman-Yassky E, Thaçi D, Pangan AL, et al. Upadacitinib in adults with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: 16-week results from a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;145:877–84.

Guttman-Yassky E, Teixeira HD, Simpson EL, et al. Once-daily upadacitinib versus placebo in adolescents and adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (Measure Up 1 and Measure Up 2): results from two replicate double-blind, randomized controlled phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2021;397:2151–68.

Simpson EL, Papp KA, Blauvelt A, et al. Efficacy and safety of upadacitinib in patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: analysis of follow-up data from the Measure Up 1 and Measure Up 2 randomized clinical trials. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:404–13.

Blauvelt A, Teixeira HD, Simpson EL, et al. Efficacy and safety of upadacitinib vs dupilumab in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:1047–55.

Silverberg JI, Simpson EL, Thyssen JP, et al. Efficacy and safety of abrocitinib in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:863–73.

Simpson EL, Sinclair R, Forman S, et al. Efficacy and safety of abrocitinib in adults and adolescents with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (JADE MONO-1): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2020;396:255–66.

Bieber T, Simpson EL, Silverberg JI, et al. Abrocitinib versus placebo or dupilumab for atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1101–12.

Reich K, Thyssen JP, Blauvelt A, et al. Efficacy and safety of abrocitinib versus dupilumab in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a randomised, double-blind, multicentre phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2022;400:273–82.

Bieber T, Thyssen JP, Reich K, et al. Pooled safety analysis of baricitinib in adult patients with atopic dermatitis from 8 randomized clinical trials. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:476–85.

Simpson EL, Silverberg JI, Nosbaum A, et al. Integrated safety analysis of abrocitinib for the treatment of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis from the phase II and phase III clinical trial program. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2021;22:693–707.

Ingrassia JP, Maqsood MH, Gelfand JM, et al. Cardiovascular and venous thromboembolic risk with JAK inhibitors in immune-mediated inflammatory skin diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2024;160:28–36.

European Medicines Agency. Janus kinase inhibitors (JAKi)( 2023) [cited 2023 Oct 5]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/referrals/janus-kinase-inhibitors-jaki

Medicines.org.uk. Dupixent 300 mg solution for injection in pre-filled syringe – Summary of product characteristics (SPC). 2019 [cited 2020 March 9]. Available from: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/8553/smpc [accessed on 09 March 2020].

Silverberg JI, Gooderham M, Katoh N, et al. Optimizing the management of atopic dermatitis with a new minimal disease activity concept and criteria and consensus-based recommendations for systemic therapy. Presented at the Revolutionizing Atopic Dermatitis (RAD) Virtual Conference; December 11, 2022 [cited 2023 June 2]. Available from: https://djbpnesxepydt.cloudfront.net/radv/December2022/Dec2022Posters/327_AD-CQP-MDA-Concept-and-Recs_Silverberg-et-al_Poster_1670622881445.pdf

Machovcová A, Cetkovská P, Fialová J, Gkalpakiotis S, Kojanová M. Atopická dermatitida: soucasná doporucení pro diagnostiku a lécbu. Cást II Ces-slov Derm. 2023;98(3):123–49.

Simpson E, Eckert L, Gadkari A, et al. Validation of the Atopic Dermatitis Control Tool (ADCT©) using a longitudinal survey of biologic-treated patients with atopic dermatitis. BMC Dermatol. 2019;19:15.

Ren Z, Silverberg JI. Association of atopic dermatitis with bacterial, fungal, viral, and sexually transmit- ted skin infections. Dermatitis. 2020;31:157–64.

Schmitt J, Schmitt N, Meurer M. Cyclosporin in the treatment of patients with atopic eczema - a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:606–19.

Simpson EL, Bruin-Weller M, Flohr C, et al. When does atopic dermatitis warrant systemic therapy? Recommendations from an expert panel of the International Eczema Council. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:623–33.

European Medicines Agency. Sandimmun Neoral - Summary of product characteristics (SPC). 2013 [cited 2023 March 2] Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/referral/sandimmun-neoral-article-30-referral-annex-iii_en.pdf

Roekevisch E, Spuls PI, Kuester D, et al. Efficacy and safety of systemic treatments for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a systematic review. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:429–38.

Accessdata.fda.gov RINVOQTM (upadacitinib) extended-release tablets, for oral use – Product information. 2019 [cited 2022 June 23]. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/211675s000lbl.pdf

European Medicines Agency. Cibinqo - Summary of product characteristics (SPC). 2022 [cited 2023 Feb 10]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/cibinqo-epar-product-information_en.pdf

European Medicines Agency. Olumiant - Summary of product characteristics (SPC) (2023) [cited 2023 Dec 19]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/olumiant-epar-product-information_en.pdf

European Medicines Agency. Adtralza - Summary of product characteristics (SPC) (2023) [cited 2024 Jan 15]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/adtralza-epar-product-information_en.pdf

Acknowledgements

Springer Healthcare is not responsible for the validity of guidelines it publishes.

Medical Writing Assistance

Initial medical writing support for the development of this manuscript was provided by Sonia Laflamme. Updates to the manuscript following the 2022 teleconferences were completed by Caroline Spencer (Rx Communications, Mold, UK), funded by the Emirates Dermatological Society.

Funding

Medical writing support, and Open Access fees were funded by the Emirates Dermatological Society.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ahmed Ameen, Ahmed Al Dhaheri, Ashraf M. Reda, Ayman Alnaeem, Fatima Al Marzooqi, Fatima Albreiki, Huda Rajab Ali, Hussein Abdel Dayem, Jawaher Alnaqbi, Mariam Al Zaabi, Mohammed Ahmed, Georg Stingl and Muna Al Murrawi contributed to the interpretation of the data and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Ahmed Ameen has received honorarium as speaker and/or advisor and/or principal investigator from AbbVie, Ego Pharma, Galderma, Janssen, LEO Pharma, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, and Sanofi. Hussein Abdel Dayem has received honoraria from Abbvie, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Medpharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi, and UCB. Georg Stingl has received consultation and/or lecture fees from Almirall, AOP Health, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Evommune, LEO Pharma, Lilly, Marinomed AG, Novartis, and Sanofi/Regeneron. Ahmed Al Dhaheri, Ashraf M. Reda, Ayman Alnaeem, Fatima Al Marzooqi, Fatima Albreiki, Huda Rajab Ali, Jawaher Alnaqbi, Mariam Al Zaabi, Mohammed Ahmed, and Muna Al Murrawi have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Approval

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors. Ethical approval was not required.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ameen, A., Dhaheri, A.A., Reda, A.M. et al. Consensus Recommendations for the Management of Atopic Dermatitis in the United Arab Emirates. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 14, 2299–2330 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-024-01247-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-024-01247-4