Abstract

Background

Palmoplantar pustulosis (PPP), a refractory skin disease characterized by repeated eruptions of sterile pustules and vesicles on palms and/or soles, involves interleukin-17 pathway activation. Brodalumab, a fully human anti-interleukin-17 receptor A monoclonal antibody, is being investigated for use in PPP treatment.

Objective

The aim was to assess the efficacy and safety of brodalumab in Japanese PPP patients with moderate or severe pustules/vesicles.

Methods

A phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial was conducted between July 2019 and August 2022, at 41 centers in Japan. Patients aged 18–70 years with a diagnosis of PPP for ≥ 24 weeks, a PPP Area Severity Index (PPPASI) score of ≥ 12, a PPPASI subscore of pustules/vesicles of ≥ 2, and inadequate response to therapy were included. Participants were randomized 1:1 to receive brodalumab 210 mg or placebo, subcutaneously (SC) at baseline, weeks 1 and 2, and every 2 weeks (Q2W) thereafter until week 16. Changes from baseline to week 16 in the PPPASI total score (primary endpoint) and other secondary skin-related endpoints and safety endpoints were assessed.

Results

Of the 126 randomized patients, 50 of 63 in the brodalumab group and 62 of 63 in the placebo group completed the 16-week period. Reasons for discontinuation were adverse event (n = 6), withdrawal by patient/parent/guardian (n = 3), progressive disease (n = 3), and lost to follow-up (n = 1) in the brodalumab group and Good Clinical Practice deviation (n = 1) in the placebo group. Change from baseline in the PPPASI total score at week 16 was significantly higher (p = 0.0049) with brodalumab (least-squares mean [95% confidence interval {CI}] 13.73 [10.91–16.56]) versus placebo (8.45 [5.76–11.13]; difference [95% CI] 5.29 [1.64–8.94]). At week 16, brodalumab showed a trend of rapid improvement versus placebo for PPPASI-50/75/90 response (≥ 50%/75%/90% improvement from baseline) and Physician’s Global Assessment 0/1 score: 54% versus 24.2%, 36.0% versus 8.1%, 16.0% versus 0.0%, and 32.0% versus 9.7%, respectively. Infection was the dominant treatment-emergent adverse event (TEAE); the commonly reported TEAEs were otitis externa (25.4%/1.6%), folliculitis (15.9%/3.2%), nasopharyngitis (14.3%/4.8%), and eczema (14.3%/12.9%) in the brodalumab/placebo groups, respectively. The severity of most TEAEs reported was Grade 1 or 2 and less frequently Grade ≥ 3.

Conclusions

Brodalumab SC 210 mg Q2W demonstrated efficacy in Japanese PPP patients. The most common TEAEs were mild infectious events.

Trial Registration

NCT04061252 (Date of Trial Registration: August 19, 2019)

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In this phase 3, randomized, double-blind trial, brodalumab demonstrated significantly higher reduction from baseline in the Palmoplantar Pustulosis Area and Severity Index (PPPASI) score versus placebo at week 16. |

Achievement of PPPASI-50/75/90 responses (corresponding to ≥ 50%/75%/90% improvement from baseline in the PPPASI total score) and Physician’s Global Assessment 0/1 score were higher in the brodalumab group. |

Infection was numerically the most common adverse event reported. A higher dropout rate was observed in the brodalumab group, which may be at least partially related to adverse events. The most common severity grade of adverse events was 1–2. |

1 Introduction

Palmoplantar pustulosis (PPP) is a chronic refractory inflammatory skin disease characterized by repeated eruptions of sterile pustules on the palms and/or soles [1]. It presents as chronic or recurrent erythematous hyperkeratotic plaques, with involvement of the palms (5–15%), soles (17–18%), or both (67–77%) [2, 3]. National prevalence of PPP in Japan between April 2010 and March 2011 was 0.12% [4], which is substantially higher than the 0.01–0.05% annual prevalence reported in Western countries [5, 6]. Though the reasons for the difference in the disease burden in Japan and Western countries remain unknown, genetic and epigenetic factors may play a role [7]. The disease definitions of PPP are different across countries and are confusing. In Western countries, there is a view that PPP is a psoriasis-related disease (type B) having its origin in the report from Barber in 1930 [8]. The paper stated that four out of five cases were pustular psoriasis [8]. However, there is a proposal by the International Psoriasis Council (IPC) that PPP should be regarded as a separate entity to psoriasis (type A) [9]. The view on this disease in Japan is similar to that of the IPC and originates from the report from Andrews in 1935 [10], wherein PPP is considered as a distinct disease entity to psoriasis [11].

Epidemiological studies indicate a clear preponderance of women: 62–83% of PPP patients are women; moreover, a majority (54–95%) are current or former smokers [2, 3, 6, 12,13,14]. The average age of disease onset is > 40 years [2, 3, 12,13,14]. It is widely known that focal infections and smoking are involved in the development and exacerbation of PPP, and their management is important to treat PPP [15]. Indeed, dental procedures and tonsillectomy have been reported to improve PPP symptoms, and smoking has been reported to be an aggravating factor for PPP, and such factors should be considered in the management of PPP [16].

PPP is also treated using topical agents (dermocorticoids, vitamin D), phototherapy (psoralens plus long-wave ultraviolet radiation [PUVA], ultraviolet A1), and systemic treatments (retinoids, ciclosporin, biologics, etretinate + PUVA therapy combined, and antibiotics) [1]. Generally, therapeutic options for PPP are similar to those for psoriasis. According to a retrospective study of Japanese insurance claims data including 5162 adults with PPP [17], 47.8%, 46.4%, and 5.4% of PPP patients were prescribed systemic nonbiologic drugs, topical therapy, and phototherapy, respectively, and 0.4% of patients were eligible for prescribed biologics.

Recently, several therapeutic agents, such as agents targeting phosphodiesterase-4 (PDE4) or Janus kinase (JAK), are being investigated [18,19,20,21,22,23]. Moreover, some agents targeting the IL-23–IL-17 axis are also under investigation, and guselkumab and risankizumab have been already approved [24, 25]. Interleukin (IL)-17 pathway activation is involved in the pathology and progress of PPP [7, 26]. Patients with PPP have increased T helper (Th)17 cell count and IL-17A concentration in the blood compared with healthy adults [27, 28]. Furthermore, Th17 cell accumulation and high IL-17 mRNA expression are seen in the affected cutaneous tissues [26, 28,29,30]. There is a case series showing that bimekizumab, an anti-IL-17A and IL-17F antibody, was effective for PPP [31]. Therefore, IL-17 inhibitors are expected to be a new treatment target.

Brodalumab is a fully human immunoglobulin G2 monoclonal antibody that has a high affinity for IL-17 receptor A (IL-17 RA) [32]. Selective binding of brodalumab to IL-17 RA inhibits signaling by multiple IL-17 ligands such as IL-17A, IL-17C, IL-17E, IL-17F, and IL-17A/F [33]. Given the involvement of IL-17 pathway activation in PPP coupled with the proven efficacy and safety of brodalumab as an anti-IL-17 RA monoclonal antibody especially for patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis, brodalumab is expected to be an effective therapeutic agent for PPP as well. There have been case reports of brodalumab being prescribed for palmoplantar pustular psoriasis, yet there have been no previous reports on PPP [34, 35]. The present study is the first to report a randomized controlled trial demonstrating the efficacy of an IL-17 inhibitor in PPP and was the basis for the approval of brodalumab in Japan. We present the results of a phase 3, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial assessing the efficacy and safety of brodalumab in Japanese patients with PPP with moderate or severe pustules/vesicles, especially focusing on the primary and key secondary endpoints up to week 16.

2 Materials and Methods

2.1 Study Design

This phase 3, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study was conducted between July 2019, and August 2022, at 41 centers in Japan. The study consisted of the screening period (from the day of consent until before initiating study intervention, ≤ 30 days), the 16-week, double-blind period, and the 52-week, open-label extension period (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04061252; Online Resource 1, see the electronic supplementary material).

Eligible PPP patients were randomized at the case enrollment center in a 1:1 ratio to the brodalumab 210 mg group or the placebo group during the screening period by using a dynamic allocation scheme after considering the following factors: PPP Area and Severity Index (PPPASI) total score at enrollment (< 21, ≥ 21 and < 31, ≥ 31), presence or absence of pustulotic arthro-osteitis, smoking status (active smoker or nonsmoker) at enrollment, and the investigating site. In this double-blind trial, both physicians and patients were blinded to the treatment assignment. The respective interventions, either brodalumab 210 mg or the placebo, were subcutaneously (SC) administered at baseline, at weeks 1 and 2, and every 2 weeks (Q2W) thereafter during the double-blind period. At week 16, all patients entered a 52-week, open-label, extension phase and received brodalumab 210 mg SC Q2W until week 68.

2.2 Participants

Those included were patients aged ≥ 18 to ≤ 70 years, able to provide voluntary written informed consent, with a diagnosis of PPP (with or without osteoarticular lesions) for ≥ 24 weeks, and having a PPPASI total score ≥ 12 and a PPPASI severity score of pustules/vesicles on the palms or soles of ≥ 2 both at pre-examination and enrollment examination (details in Online Resource 2, see the electronic supplementary material). Briefly, patients had to meet all the following criteria for diagnosis of PPP: (1) pustules on the palms, soles, or both; (2) progression from vesicles to pustules; and (3) repeated occurrence of lesions at the same sites. Patients with a diagnosis of plaque psoriasis, pustular psoriasis, drug-induced PPP, or pompholyx were excluded. Moreover, patients with a known focal infection at the time of informed consent who had not received appropriate treatment or patients who had received treatment for focal infection (e.g., tonsillectomy and dental treatment) or treatment for metal allergy (e.g., change of dental materials) within 6 months before the start of the intervention were also excluded. Patients who used systemic antibiotics within 4 weeks before the start of the intervention were also excluded.

Concomitant use of topical medicines (except emollients) and systemic therapy with or without biologics for PPP, as well as phototherapy, were not permitted during the study period.

2.3 Endpoints

The primary efficacy endpoint was change from baseline in PPPASI total score at week 16. Secondary efficacy endpoints assessed at week 16 included the following: achievement of PPPASI-50/75/90 response (corresponding to 50%/75%/90% or greater improvement from baseline in the PPPASI total score), change from baseline in PPP Severity Index (PPP-SI) total score (Online Resource 2), PPP-SI-50/75/90 (corresponding to 50%/75%/90% or greater improvement from baseline in the PPP-SI total score), change from baseline in each PPP-SI component score, achievement of a Physician’s Global Assessment (PGA) score of 0 or 1, change in Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) score from baseline, change from baseline in Numerical Rating Scale (NRS)-PPP pain score, change from baseline in NRS-PPP itch score, and change from baseline in pustule/vesicle severity score. Additionally, subgroup analyses comparing the improvement at 16 weeks from baseline PPPASI total score between brodalumab and placebo groups were performed by baseline characteristics. These included analyses by gender (male or female), age (< 65 or ≥ 65 years), body weight (< median or ≥ median), disease duration (< median or ≥ median), PPPASI total score at enrollment (< 21, ≥ 21 to < 31, or ≥ 31), change in PPPASI total score from screening to baseline (improved, unchanged, or deteriorated), presence of pustulotic arthro-osteitis (yes or no), smoking habit at enrollment (yes or no), body mass index (BMI) (< 25 or ≥ 25), PPP-SI total score at enrollment (≥ 4 to ≤ 9 or > 9), PGA at enrollment (< 4 or ≥ 4), pustule/vesicle severity score at enrollment < 3 or ≥ 3, nail findings at enrollment (yes or no), period at enrollment (January–March, April–June, July–September, or October–December), history of previous non-biological systemic treatment (yes or no), history of previous biological treatment (yes or no), previous systemic treatment (yes or no), topical treatment (yes or no), previous phototherapy (yes or no), previous therapy for focal infection (yes or no), history of granulocyte and monocyte absorption apheresis (yes or no), and treatment for metal allergy (yes or no).

For PPPASI scoring, the palms and soles were divided into four areas: right palm (RP), left palm (LP), right sole (RS), and left sole (LS), which account for 20%, 20%, 30%, and 30%, respectively, of the total surface area of the palms or soles. Each area is comprehensively evaluated for erythema (E), pustule/vesicle, including crusts, i.e., dried pustules (P), and desquamation/scales (D), each rated on a 5-point scale of none (0), mild (1), moderate (2), severe (3), and very severe (4). The total score, calculated as PPPASI = (E + P + D) area × 0.2 (RP) + (E + P + D) area × 0.2 (LP) + (E + P + D) area × 0.3 (RS) + (E + P + D) area × 0.3 (LS), ranges from 0 to 72, and a higher score indicates severe disease.

Key safety endpoints were evaluated after the administration of drugs as treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) and drug-related TEAEs. Clinical laboratory test results, vital signs (systolic and diastolic blood pressures, pulse rate, respiratory rate, and body temperature), anti-brodalumab antibodies, Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS), and Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ)-8 were reviewed to identify TEAEs.

2.4 Statistical Analysis

The target sample size of 120 was set based on data from the previous phase 3, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of guselkumab in patients with PPP [18]. Assuming the mean value of change in the PPPASI total score of − 15.0 and − 8.0 in the brodalumab and placebo groups, respectively, with a standard deviation (SD) of 11.5 in both groups and an absolute mean difference between the two groups of 7.0, at week 16, the sample size was calculated to be 58 patients per group for the primary endpoint at a significance level of 0.05 (two-sided) and 90% or greater power.

The patients who dropped due to Good Clinical Practice (GCP) deviations were excluded from both safety and efficacy analyses if the patients had not provided consent as specified in the protocol. For descriptive analysis of efficacy data, quantitative variables were summarized as mean (SD), while qualitative variables were summarized as number (%). Changes from baseline in the PPPASI and PPP-SI total scores at week 16 were compared between the groups using a mixed model for repeated measures (MMRM), with fixed effects for the treatment group, time point, PPPASI total score at baseline, eligibility for pustulotic arthro-osteitis evaluation (yes/no), smoking habit (yes/no), and interaction of treatment groups with time points. The treatment effect for the brodalumab group compared to the placebo group at week 16 was estimated based on the least-squares (LS) mean differences; a t test was performed for these LS mean differences between the groups at week 16 at a significance level of 0.05 (two-sided). Additional exploratory analyses were conducted for evaluating the possible association between improvement from baseline DLQI, NRS-PPP itch, and NRS-PPP pain scores at week 16 and the achievement of PPPASI-50/75/90 responses.

For missing efficacy data at week 16 for PPPASI total score and PPP-SI total score, imputation was not performed, and only observed data were used as a part of the MMRM analysis. For the other missing continuous data, the baseline observation carried forward (BOCF) approach was used. For missing categorical (binary) data, nonresponder imputations (NRI) were performed.

All randomized patients who received an administration of the investigational drug were included in the modified intention-to-treat (mITT) population, with modification to exclude patients with ITT who had discontinued between informed consent and treatment initiation, and the efficacy was analyzed in the mITT population. The safety analysis population was set as the same as the mITT population. For the safety analysis, important identified risks and important potential risks of brodalumab were evaluated as adverse events (AEs) of special interest. Specifically, events related to neutrophil count decrease, serious infection, serious hypersensitivity, malignancy, inflammatory bowel disease, and suicide/self-injury-related events were evaluated. TEAEs were summarized by the treatment group using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) (version 22.0) System Organ Class and Preferred Terms.

2.5 Ethical Compliance

The study (NCT04061252) was conducted in compliance with the protocol, the Declaration of Helsinki (World Medical Association [WMA]) [36], the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS) International Ethical Guidelines [37], the International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH) Good Clinical Practice Guidelines [38], and other applicable laws and regulations. It was approved by the concerned institutional review board. All participants gave written informed consent.

3 Results

3.1 Participant Flow

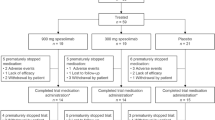

A total of 126 patients were randomized 1:1 to receive brodalumab 210 mg (n = 63) or placebo (n = 63) (Fig. 1). Of these, 50 patients in the brodalumab group and 62 patients in the placebo group completed the 16-week, double-blind phase, while 13 and one patient, respectively, discontinued by week 16. The reasons for discontinuation in the brodalumab group were AEs (n = 6), including four infections, one of which was a focal infection, periodontitis (Online Resource 2, see the electronic supplementary material), withdrawal by patient/parent/guardian (n = 3), progressive disease (n = 3), and lost to follow-up (n = 1). Most discontinuations happened relatively early, with three patients discontinuing between week 2 and week 4, and four more patients discontinuing between week 4 and week 6, though the reasons for discontinuation were not substantially associated with the timing of discontinuation. One patient from the placebo group with GCP deviation (n = 1) was excluded from both efficacy and safety analyses. In this study, no patients dropped out before initiation of post-randomization medication. Both the mITT and safety profile population were 125 people (63 for brodalumab, and 62 for placebo).

3.2 Baseline Characteristics

Patient characteristics were generally comparable between the two groups, except for lower BMI (mean [SD] 23.8 [4.0] vs 25.1 [5.0] kg/m2), more biological treatment (12.7% vs 1.6%), and higher DLQI score (mean [SD] 9.1 [6.3] vs 7.6 [5.0]) in the brodalumab group versus the placebo group, respectively (Table 1). There were 37 patients (58.7%) who had a smoking habit in the brodalumab group and 36 (58.1%) in the placebo group at baseline. Two patients (one each from brodalumab and placebo groups) achieved smoking cessation during the 16-week, double-blind phase of the trial. All (100%) patients were Asian; all patients had used topical treatment in the past, and none had used granulocyte and monocyte adsorption apheresis.

3.3 Efficacy

PPPASI total score showed a trend of improvement (reduction in score from baseline) in the brodalumab group starting as early as week 2 (treatment difference [95% confidence interval {CI}] − 6.18 [− 4.01 to − 8.36]), and the improvement was consistently seen until week 16 (− 5.29 [−1.64 to − 8.94]) (Fig. 2). Reduction in the PPPASI total score from baseline through week 16 was significantly higher (p = 0.0049) in the brodalumab group (LS mean [95% CI] 13.73 [10.91–16.56]) compared to the placebo group (8.45 [5.76–11.13]); score reduction in the brodalumab group was significantly greater when compared to that in the placebo group at week 16 (5.29 [1.64–8.94]). Furthermore, the trend of rapidly achieving PPPASI-50/75 response was observed in the brodalumab group (PPPASI-50: 54.0% [brodalumab] vs 24.2% [placebo] at week 16; PPPASI-75: 36.0% vs 8.1% at week 16) (Online Resource 3, see the electronic supplementary material).

LS mean of change from baseline in PPPASI total score. Note: The brodalumab (210 mg) group had 63, 63, 56, 53, and 50 patients at week 2, 4, 8, 12, and 16, respectively. The placebo group had 62 patients for all timepoints. A t test was performed, and p values were estimated for the LS mean difference at week 16 between the 2 groups, using an MMRM. Error bars in the figure indicate 95% CI. CI confidence interval, LS least-squares, MMRM mixed model for repeated measures, PPP palmoplantar pustulosis, PPPASI PPP Area and Severity Index

Similarly, by week 16, 16.0% versus 0.0% of patients in the brodalumab group versus placebo group achieved PPPASI-90 response (Table 2). PPP-SI total score, PPP-SI-50/75/90 response, and PGA 0/1 (0 or 1 of PGA score) response showed a higher improvement in the brodalumab group versus the placebo group (− 3.7 [brodalumab] vs − 1.9 [placebo], 48.0% vs 14.5%, 18.0% vs 1.6%, 8.0% vs 0.0%, and 32.0% vs 9.7% each). PPP-SI component scores (erythema: − 1.4 vs − 0.7, pustules/vesicle: − 1.4 vs − 0.4, desquamation/scale: − 1.1 vs − 0.7), pustule/vesicle severity score (− 1.3 vs − 0.4), NRS-PPP pain score (− 1.7 vs − 2.2), and NRS-PPP itch score (− 1.4 vs − 1.6) also showed numerically more improvement in the brodalumab group versus the placebo group (Table 2). Similar results were observed from our analyses using the NRI and BOCF approach (Online Resource 4). A subgroup analysis demonstrated that the change from baseline in the PPPASI total score at week 16 (MMRM) was generally similar to the overall results across the subgroups (Online Resource 5). The changes in the brodalumab group versus the placebo group were similar to those seen in the overall population (13.73 vs 8.45) when analyzed in those with systemic non-biological treatment (15.90 vs 10.17), smokers at enrollment (12.35 vs 8.82), those with BMI < 25 (12.77 vs 8.11), and without therapy for focal infection (14.68 vs 8.88). There were larger improvements in the brodalumab group versus the placebo group for females (14.91 vs 8.65), those younger than 65 years (14.29 vs 7.21), and those with a baseline PPPASI total score ≥ 31 (26.69 vs 13.45) or a baseline PPP-SI total score > 9 (26.32 vs 11.51). Although comparisons by previous use of biologic agents were difficult to make because of the smaller number of patients who had previously used biologics, our results did not demonstrate any reduction in the efficacy of brodalumab in patients who had used biologic agents previously.

The mean change from baseline in the DLQI score at week 16 was comparable in the brodalumab and placebo groups (− 2.8 vs − 2.7) (Table 2). Our exploratory analyses showed that among those who achieved PPPASI-50 response, both the brodalumab and placebo groups had numerically higher mean [SD] improvement in DLQI score (brodalumab: − 5.0 [6.22]; placebo: − 3.7 [2.85]) (Online Resource 6). On the other hand, among those who did not achieve a PPPASI-50 response, improvement in DLQI score was numerically lower (brodalumab: − 0.3 [6.00], placebo: − 2.4 [5.36]).

3.4 Safety

A total of 92.1% of patients in the brodalumab group versus 58.1% of patients in the placebo group experienced TEAEs (Table 3). Infections dominated the TEAEs; as per MedDRA classifications, the commonly reported TEAEs in the brodalumab/placebo groups, respectively, were otitis externa (25.4%/1.6%), folliculitis (15.9%/3.2%), nasopharyngitis (14.3%/4.8%), and eczema (14.3%/12.9%). The severity of most TEAEs reported was Grade 1 or 2 and less frequently Grade ≥ 3. The proportion of drug-related TEAEs was 47.6% in the brodalumab group versus 12.9% in the placebo group (Table 3). Commonly reported drug-related TEAEs in the brodalumab/placebo groups included otitis externa (12.7%/0.0%), eczema (7.9%/1.6%), and folliculitis (6.3%/0.0%). No deaths or suicide/self-injury-related events were observed. One patient (1.6%) in each group developed AEs of special interest. In the brodalumab group, one patient developed a serious infection, pneumonia, which was defined by the sponsor as “infections and infestations (MedDRA System Organ Classes) and serious AE” in the statistical analysis plan. In the placebo group, one patient developed an inflammatory bowel disease, duodenal ulcer, which was one of the 72 MedDRA Preferred Terms to be handled as “inflammatory bowel disease” in the statistical analysis plan as defined by the sponsor.

In this study, otitis externa occurred in 17 patients (16 in the brodalumab group and one in the placebo group). The severity was Grade 2 for all patients, and no patient withdrew from the study due to otitis externa. Thirteen patients received antibiotics, ten patients received steroids (of which eight also received antibiotics), and two patients received no medication. In most of the patients treated, otitis externa was treated only with topical therapy, and four patients received oral antibiotics. While some patients did not recover during the study period, all patients were ultimately confirmed to have recovered.

4 Discussion

This is the first report of a randomized controlled trial demonstrating the efficacy of an IL-17 inhibitor in PPP. Our results provided the efficacy and safety information of brodalumab SC (210 mg) Q2W treatment in Japanese PPP patients with moderate or severe pustules/vesicles. The primary endpoint was met. At week 16, the reduction from baseline in the PPPASI total score was significantly higher in the brodalumab versus the placebo group. Other secondary efficacy endpoints such as achievement of PPPASI-50/75/90 response, PPP-SI total score, PPP-SI-50/75/90 response, and PGA 0/1 also demonstrated substantial improvement in the brodalumab group compared to the placebo group. Infections were the most commonly reported TEAEs. It is difficult to assess generalizability because both the type A and type B views exist in Western countries. Although a case series from Germany suggested the potential efficacy of brodalumab for palmoplantar pustular psoriasis in Western patients [34], further studies are needed to determine whether brodalumab is effective in Western patients as well as in Japanese patients with PPP.

The efficacy of brodalumab demonstrated in this study was comparable to other biologics such as anti-IL-23 inhibitors. Importantly, brodalumab showed a characteristic of early onset of action. Notably, head-to-head comparator trials with brodalumab and other agents are not available and therefore it is not possible to conclude on the efficacy of brodalumab versus other agents. Nevertheless, compared to other agents [39], the difference in the change in PPPASI score from the brodalumab group to the placebo group was greater in the early stage of the present study. In PPP, IL-23 stimulates IL-17 production by activating Th17 cells, thereby stimulating cytokine production, neutrophil infiltration, and pustule formation [7, 15, 26, 28, 40]. Specifically, abnormal antimicrobial peptide in the acrosyringium triggers inflammation of intraepithelial vesicles, inducing inflammation associated with production of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-17C. Additionally, this process leads to neutrophil migration via production of chemokines such as C-X-C motif ligand (CXCL)1 and CXCL2. Furthermore, IL-8 induces pustule formation in vesicles; IL-17A produced by Th17 cells stimulates keratinocytes and induces inflammatory cytokines such as IL-17C and IL-8, thereby maintaining and enhancing the inflammatory state in formation of pustules from blisters [26, 29, 41, 42]. Being an IL-17 RA blocker, brodalumab blocks signals from multiple IL-17 cytokines, including IL-17A, IL-17C, IL-17E, and IL-17F. IL-17 being downstream of IL-23 may be a reason for improvement seen as early as 2 weeks in the present study.

The mean improvement in DLQI scores at week 16 from baseline was comparable in the brodalumab and placebo groups in this study. This may be the result of the fact that PPP has a natural process of chronic remission and exacerbation, and DLQI, pain, and itch scores may not improve until PPP is almost completely resolved [7, 43]. Indeed, patients with higher improvement in PPPASI had higher improvement in DLQI, NRS-PPP itch, and NRS-PPP pain, which was demonstrated by our ad hoc exploratory analyses. It is possible that DLQI will also improve if a higher improvement in PPPASI is observed.

The brodalumab group, in comparison with the placebo group, had more TEAEs (92.1% vs 58.1%) and drug-related TEAEs (47.6% vs 12.9%). Previous trials reported a higher proportion of infections for brodalumab 210 mg groups; Papp et al. reported nasopharyngitis (9.5%) and upper respiratory tract infection (8.1%) in 12 weeks [44], while Nakagawa et al. reported nasopharyngitis (10.8%) and folliculitis (5.4%) in 12 weeks [45] as common AEs when used for patients with psoriasis. Similarly, in the present trial, infections were the most commonly reported AEs by 16 weeks, though the proportion of infections was higher than in other studies and more frequently reported compared to other AEs. In particular, the occurrence of otitis externa was more frequent than in previous studies targeting other diseases. Both in mice and in humans, IL-17 signal is known to be involved in the skin microbiome and barrier function [46, 47]. Differences in the pathogenesis of psoriasis and PPP [5, 48] may have contributed to the higher proportion of infections in PPP. Although the mechanism of infection development is not known, careful attention should be paid when administering brodalumab, as the infections may be disease specific. Moreover, in PPP, focal infections are known to be associated with the development and worsening of PPP [49]. There is a possibility that some patients with subclinical infection became symptomatic after trial initiation. The higher proportion of TEAEs probably resulted in more discontinuations in the brodalumab than the placebo group. Indeed, six of 13 discontinuations in the brodalumab group were due to AEs (four AEs were infections; for one of these, there is a possibility that subclinical focal infection became symptomatic). Other reasons for discontinuation included patient withdrawal (3/13), progressive disease (3/13), and lost to follow-up (1/13). It may be speculated that some dropouts were due to insufficient efficacy of brodalumab monotherapy under the prohibition of concomitant use of several drugs. The focal infection-related discontinuation might have resulted from the prohibition of antibiotics for systemic use during the intervention and assessment period. The reported TEAEs were mostly of Grade 1 or 2 severity. Moreover, the infections found in this study were within the current risk profile of brodalumab. However, it should be kept in mind that there are features of TEAEs that are unique to PPP, such as focal infections, which may have led to discontinuation in some patients.

Some limitations of the present study should be acknowledged. This study provides data over a short treatment period. With restrictions on the concomitant use of most medicines except emollients, the efficacy and safety of brodalumab when used concomitantly with other common medicines such as topical corticosteroids cannot be assessed. Some of the baseline characteristics were somewhat imbalanced between the groups. This should be noted while interpreting the results. Details of previous biological treatment and the timing/reasons for discontinuation were not captured. Also, the time taken for the treatment of focal infection to take effect remains unknown.

5 Conclusions

Brodalumab SC 210 mg Q2W treatment for 16 weeks was demonstrated to have therapeutic potential in Japanese PPP patients in this phase 3, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Brodalumab demonstrated significant improvement in the PPPASI total score and other efficacy endpoints. Since the brodalumab group showed a numerically higher dropout rate and infectious AEs than the placebo group, administration of brodalumab should be considered based on a risk–benefit balance.

References

Obeid G, Do G, Kirby L, Hughes C, Sbidian E, Le Cleach L. Interventions for chronic palmoplantar pustulosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;1:CD011628.

Brunasso AMG, Puntoni M, Aberer W, Delfino C, Fancelli L, Massone C. Clinical and epidemiological comparison of patients affected by palmoplantar plaque psoriasis and palmoplantar pustulosis: a case series study. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:1243–51.

Wilsmann-Theis D, Jacobi A, Frambach Y, Philipp S, Weyergraf A, Schill T, et al. Palmoplantar pustulosis - a cross-sectional analysis in Germany. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030.

Kubota K, Kamijima Y, Sato T, Ooba N, Koide D, Iizuka H, et al. Epidemiology of psoriasis and palmoplantar pustulosis: a nationwide study using the Japanese national claims database. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e006450–e006450.

de Waal AC, van de Kerkhof PCM. Pustulosis palmoplantaris is a disease distinct from psoriasis. J Dermatol Treat. 2011;22:102–5.

Löfvendahl S, Norlin JM, Schmitt-Egenolf M. Prevalence and incidence of palmoplantar pustulosis in Sweden: a population-based register study*. Br J Dermatol. 2021;185:945–51.

Murakami M, Terui T. Palmoplantar pustulosis: Current understanding of disease definition and pathomechanism. J Dermatol Sci. 2020;98:13–9.

Barber HW. Acrodermatitis continua vel perstans (Dermatitis repens) and Psoriasis pustulosa. Br J Dermatol. 1930;42:500–18.

Griffiths CEM, Christophers E, Barker JNWN, Chalmers RJG, Chimenti S, Krueger GG, et al. A classification of psoriasis vulgaris according to phenotype. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:258–62.

Andrews GC. Pustular bacterids of the hands and feet. Arch Dermatol. 1935;32:837.

Asumalahti K, Ameen M, Suomela S, Hagforsen E, Michaëlsson G, Evans J, et al. Genetic analysis of PSORS1 distinguishes guttate psoriasis and palmoplantar pustulosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;120:627–32.

Benzian-Olsson N, Dand N, Chaloner C, Bata-Csorgo Z, Borroni R, Burden AD, et al. Association of clinical and demographic factors with the severity of palmoplantar pustulosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:1216–22.

Oktem A, Uysal PI, Akdoğan N, Tokmak A, Yalcin B. Clinical characteristics and associations of palmoplantar pustulosis: an observational study. An Bras Dermatol. 2020;95:15–9.

Sarıkaya Solak S, Kara Polat A, Kilic S, Oguz Topal I, Saricaoglu H, Karadag AS, et al. Clinical characteristics, quality of life and risk factors for severity in palmoplantar pustulosis: a cross-sectional, multicentre study of 263 patients. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47:63–71.

Freitas E, Rodrigues MA, Torres T. Diagnosis, screening and treatment of patients with palmoplantar pustulosis (PPP): a review of current practices and recommendations. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2020;13:561–78.

Mrowietz U, van de Kerkhof PCM. Management of palmoplantar pustulosis: do we need to change? Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:942–6.

Miyazaki C, Sruamsiri R, Mahlich J, Jung W. Treatment patterns and healthcare resource utilization in palmoplantar pustulosis patients in Japan: A claims database study. PLoS ONE. 2020;15: e0232738.

Terui T, Kobayashi S, Okubo Y, Murakami M, Zheng R, Morishima H, et al. Efficacy and safety of guselkumab in Japanese patients With palmoplantar pustulosis: A phase 3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:1153–61.

Rahbar Kooybaran N, Tsianakas A, Assaf K, Mohr J, Wilsmann-Theis D, Mössner R. Response of palmoplantar pustulosis to upadacitinib: A case series of five patients. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2023;21:1387–92.

Haynes D, Topham C, Hagstrom E, Greiling T. Tofacitinib for the treatment of recalcitrant palmoplantar pustulosis: a case report. Australas J Dermatol. 2020;61:e108–10.

Koga T, Sato T, Umeda M, Fukui S, Horai Y, Kawashiri S-Y, et al. Successful treatment of palmoplantar pustulosis with rheumatoid arthritis, with tofacitinib: impact of this JAK inhibitor on T-cell differentiation. Clin Immunol. 2016;173:147–8.

Mössner R, Hoff P, Mohr J, Wilsmann-Theis D. Successful therapy of palmoplantar pustulosis with tofacitinib-Report on three cases. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33: e13753.

Wang YA, Rosenbach M. Successful treatment of refractory tumor necrosis factor inhibitor-induced palmoplantar pustulosis with tofacitinib: Report of case. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:115–8.

Pang Y, D’Cunha R, Winzenborg I, Veldman G, Pivorunas V, Wallace K. Risankizumab: Mechanism of action, clinical and translational science. Clin Transl Sci. 2024;17: e13706.

Okubo Y, Morishima H, Zheng R, Terui T. Sustained efficacy and safety of guselkumab in patients with palmoplantar pustulosis through 1.5 years in a randomized phase 3 study. J Dermatol. 2021;48:1838–53.

Bissonnette R, Nigen S, Langley RG, Lynde CW, Tan J, Fuentes-Duculan J, et al. Increased expression of IL-17A and limited involvement of IL-23 in patients with palmo-plantar (PP) pustular psoriasis or PP pustulosis; results from a randomised controlled trial. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:1298–305.

Torii K, Saito C, Furuhashi T, Nishioka A, Shintani Y, Kawashima K, et al. Tobacco smoke is related to Th17 generation with clinical implications for psoriasis patients. Exp Dermatol. 2011;20:371–3.

Murakami M, Hagforsen E, Morhenn V, Ishida-Yamamoto A, Iizuka H. Patients with palmoplantar pustulosis have increased IL-17 and IL-22 levels both in the lesion and serum. Exp Dermatol. 2011;20:845–7.

Hagforsen E, Hedstrand H, Nyberg F, Michaëlsson G. Novel findings of Langerhans cells and interleukin-17 expression in relation to the acrosyringium and pustule in palmoplantar pustulosis. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:572–9.

Kim DY, Kim JY, Kim TG, Kwon JE, Sohn H, Park J, et al. A comparison of inflammatory mediator expression between palmoplantar pustulosis and pompholyx. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1559–65.

Passeron T, Perrot J-L, Jullien D, Goujon C, Ruer M, Boyé T, et al. Treatment of Severe Palmoplantar Pustular Psoriasis With Bimekizumab. JAMA Dermatol. 2024;160:199.

Greig SL. Brodalumab: First Global Approval. Drugs. 2016;76:1403–12.

Menter A, Bhutani T, Ehst B, Elewski B, Jacobson A. Narrative review of the emerging therapeutic role of brodalumab in difficult-to-treat psoriasis. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2022;12:1289–302.

Pinter A, Wilsmann-Theis D, Peitsch WK, Mössner R. Interleukin-17 receptor A blockade with brodalumab in palmoplantar pustular psoriasis: report on four cases. J Dermatol. 2019;46:426–30.

Nakao M, Asano Y, Kamata M, Yoshizaki A, Sato S. Successful treatment of palmoplantar pustular psoriasis with brodalumab. Eur J Dermatol. 2018;28:538–9.

WMA The World Medical Association. WMA Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/. Accessed 16 Jan 2024

Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences. International ethical guidelines for health-related research involving humans. Available from: https://cioms.ch/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/WEB-CIOMS-EthicalGuidelines.pdf. Accessed 16 Jan 2024

International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH). ICH Official web site : ICH. Ich.

Fukasawa T, Yamashita T, Enomoto A, Yoshizaki-Ogawa A, Miyagawa K, Sato S, et al. Optimal treatments and outcome measures of palmoplantar pustulosis: A systematic review and network meta-analysis-based comparison of treatment efficacy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2024;38:281–8.

Liu T, Li S, Ying S, Tang S, Ding Y, Li Y, et al. The IL-23/IL-17 pathway in inflammatory skin diseases: from bench to bedside. Front Immunol. 2020;11: 594735.

Murakami M, Ohtake T, Horibe Y, Ishida-Yamamoto A, Morhenn VB, Gallo RL, et al. Acrosyringium is the main site of the vesicle/pustule formation in palmoplantar pustulosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:2010–6.

Murakami M, Kaneko T, Nakatsuji T, Kameda K, Okazaki H, Dai X, et al. Vesicular LL-37 contributes to inflammation of the lesional skin of palmoplantar pustulosis. PLoS ONE. 2014;9: e110677.

Misiak-Galazka M, Wolska H, Rudnicka L. What do we know about palmoplantar pustulosis? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;31:38–44.

Papp KA, Reich K, Paul C, Blauvelt A, Baran W, Bolduc C, et al. A prospective phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of brodalumab in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:273–86.

Nakagawa H, Niiro H, Ootaki K. Brodalumab, a human anti-interleukin-17-receptor antibody in the treatment of Japanese patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: efficacy and safety results from a phase II randomized controlled study. J Dermatol Sci. 2016;81:44–52.

Sparber F, LeibundGut-Landmann S. Interleukin-17 in antifungal immunity. Pathogens. 2019;8:54.

Floudas A, Saunders SP, Moran T, Schwartz C, Hams E, Fitzgerald DC, et al. IL-17 receptor A aaintains and protects the skin barrier to prevent allergic skin inflammation. J Immunol. 2017;199:707–17.

Yamamoto T. Similarity and difference between palmoplantar pustulosis and pustular psoriasis. J Dermatol. 2021;48:750–60.

Akiyama T, Seishima M, Watanabe H, Nakatani A, Mori S, Kitajima Y. The relationships of onset and exacerbation of pustulosis palmaris et plantaris to smoking and focal infections. J Dermatol. 1995;22:930–4.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients and the investigators who participated in this clinical trial. We thank Vidula Bhole, MD, MHSc of MedPro Clinical Research for providing medical writing support for this article, which was funded by Kyowa Kirin Co., Ltd.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This study was sponsored by Kyowa Kirin Co., Ltd.

Competing Interests

Y Okubo reports grants from Kyowa Kirin during the conduct of the study and grants and/or personal fees from AbbVie, Amgen Inc., Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Janssen Pharma, Jimro, Kyowa Kirin, LEO Pharma, Maruho, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi, Shiseido, Sun Pharma, Taiho Pharmaceutical, Torii Pharmaceutical, and UCB Pharma outside the submitted work. SK reports grants from Kyowa Kirin during the conduct of the study and personal fees from AbbVie, Janssen Pharma, and Taiho Pharmaceutical outside the submitted work. MM reports grants from Kyowa Kirin during the conduct of the study and grants and/or personal fees from AbbVie, Amgen Inc., Aristea Therapeutics, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Janssen Pharma, Kyowa Kirin, Maruho, Novartis Pharma, Taiho Pharmaceutical, and Torii Pharmaceutical outside the submitted work. SS reports grants from Kyowa Kirin during the conduct of the study and grants and/or personal fees from AbbVie, Amgen Inc., Eisai, Eli Lilly, Janssen Pharma, Kaken Pharmaceutical, Kyowa Kirin, Maruho, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Nippon Kayaku, Nippon Zoki Pharmaceutical, Sanofi, Sun Pharma, Taiho Pharmaceutical, Torii Pharmaceutical, and UCB Pharma outside the submitted work. NK is an employee of Kyowa Kirin. Y Ouchi is an employee of Kyowa Kirin. TT reports personal fees from Kyowa Kirin during the conduct of the study and grants and/or personal fees from AbbVie, Amgen Inc., Boehringer Ingelheim, Maruho, and Taiho Pharmaceutical outside the submitted work.

Ethics Approval:

The study (NCT04061252) was conducted in compliance with the protocol, the Declaration of Helsinki (World Medical Association [WMA]), the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS) International Ethical Guidelines, the International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH) Good Clinical Practice Guidelines, and other applicable laws and regulations. It was approved by the concerned institutional review board.

Consent to Participate and Publish

All participants gave written informed consent to participate in the research and publish the results.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study will be available in the Vivli repository (https://vivli.org/ourmember/kyowa-kirin/) as long as conditions of data disclosure specified in the policy section of the Vivli website are satisfied. Individual participant data (text, tables, figures, and appendices) that provide the basis for the results reported in this paper will be deidentified and shared.

Author Contributions

All authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article. Conceptualization: All authors contributed equally. Investigation: All authors contributed equally. Data curation: NK and Y Ouchi. Formal analysis: Y Ouchi. Methodology: NK and Y Ouchi. Writing: All authors contributed equally. Review/editing: All authors contributed equally. All authors have given their approval for this version to be published and are in agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work as a whole.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Okubo, Y., Kobayashi, S., Murakami, M. et al. Efficacy and Safety of Brodalumab, an Anti-interleukin-17 Receptor A Monoclonal Antibody, for Palmoplantar Pustulosis: 16-Week Results of a Randomized Clinical Trial. Am J Clin Dermatol 25, 837–847 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40257-024-00876-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40257-024-00876-x