Abstract

Drug-related problems (DRPs) are critical medical issues during transition from hospital to home with high prevalence. The application of a variety of interventional strategies as part of the transitional care has been studied for preventing DRPs. However, it remains challenging for minimizing DRPs in patients, especially in older adults and those with high risk of medication discrepancies after hospital discharge. In this narrative review, we demonstrated that age, specific medications and polypharmacy, as well as some patient-related and system-related factors all contribute to a higher prevalence of transitional DPRs, most of which could be largely prevented by enhancing nurse-led multidisciplinary medication reconciliation. Nurses’ contributions during transitional period for preventing DRPs include information collection and evaluation, communication and education, enhancement of medication adherence, as well as coordination among healthcare professionals. We concluded that nurse-led strategies for medication management can be implemented to prevent or solve DRPs during the high-risk transitional period, and subsequently improve patients’ satisfaction and health-related outcomes, prevent the unnecessary loss and waste of medical expenditure and resources, and increase the efficiency of the multidisciplinary teamwork during transitional care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Transitional care refers to ‘a set of actions designed to ensure the coordination and continuity of patient care and to prevent poor outcomes when patients transfer to different locations or different levels of care within the same location’ [1,2,3,4]. An optimal transitional care requires a multidisciplinary teamwork and may involve participation and lifestyle modifications for patients and their caregivers [5]. For older adults, medication management is one of the most important and challenging components for reducing length of hospital stay, readmissions, healthcare cost and mortality [6,7,8,9], since medication regimens could be significantly altered during hospitalization due to acute medical conditions or new diagnoses. Notably, medication discrepancies (defined as any difference between discharge medication list and medications patients report actually taking post discharge) were observed in more than half (56%) of the elderly patients during the first 48 h post-discharge in cross-sectoral transitional period [10], which may lead to medication errors (defined as failures in the treatment process that (potentially) lead to harm to the patients) [11]. As a matter of fact, nearly half (49%) of the patients have been reported to experience at least one medication error in continuity of care [12]. A successful medication management is not only essential for preventing/terminating medication discrepancies or errors, but also critical for reducing drug waste. Nurses play an important role in medication management during transitional period. The aim of this narrative review was to summarize from existing research the contributing factors for post-discharge drug-related problems (DRPs) and the nurses’ role in transitional care for preventing DRPs, as well as to explore the nurse-led interventional strategies in the hope of supporting them as liaison officers in this multidisciplinary teamwork.

Literature search strategy

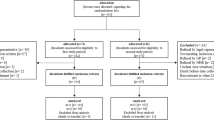

A literature search was performed on PubMed database using keywords ‘transitional care’, ‘medication reconciliation’, ‘drug-related problem’. Specifically, the search strategy was (transitional care) AND ((drug-related problem) OR (medication reconciliation)). A total of 113 English articles on human studies were collected for subsequent screening. Titles and abstracts of these articles were assessed by two authors independently, and those relevant to the searched terms were processed for further detailed review. For any discrepancies occurred, they were evaluated by a third author. Additional articles were selected when applicable based on articles in these searches and selections. Irrelevant topics, reviews, systematic reviews and/or meta-analyses, case reports and case series have all been excluded.

DRPs and their contributing factors

DRPs, as defined by the Pharmaceutical Care Network Europe (PCNE), are a group of events or circumstances involving drug therapy that actually or potentially interferes with desired health outcomes (Fig. 1). According to previous studies, the majority of patients (84%) were observed to be affected by at least one DRPs in geriatric rehabilitation centers [13], whereas an average prevalence of 81% and even a higher occurrence of 94.4% were detected in acute hospitals [14] and in long-term care hospitals [15], respectively. Among the subcategories of DRPs, the drug-drug interaction (34.6%) was the most pronounced one analyzed by a university hospital [16], whereas non-adherence (18%) was the most common one identified by pharmacists from an academic family medicine outpatient clinic [17]. The percentages of identified DRPs occurred before hospital admission, on the ward and during transitional care were 37%, 36% and 27%, respectively [16]. DRPs occurring during transitional period may lead to adverse outcomes ranging from patients’ discomfort or dissatisfaction to adverse drug events (ADEs) [18], which subsequently result in worse prognosis, prolonged hospital stay, elevated occurrence of hospital readmissions, and increased utilization of healthcare resources [19, 20].

Age

Notably, older adults are particularly vulnerable to DRPs following discharge due to multiple factors [21, 22], including chronic comorbid medical conditions, metabolic changes, functional and cognitive impairments, complicated therapeutic regimens administered (often with prescriptions from several medical providers), and extensive changes in their drugs during hospitalization. In a meta-analysis, it displayed that older adults had a three-fold and a seven-fold increase in prevalence of ADEs compared to adult and pediatric patients, respectively [23]. DRPs in older adults may result in frequent readmissions [22], especially during hospital-to-home transitional period, as various information is provided at this stressful time, which makes it difficult for patients and their caregivers to understand and remember [3, 24]. Subsequently at home, the uncertainty of new drugs from the elderly patients may lead to their anxiety and poor adherence to treatment. Therefore, it was critical to find a right timing to provide information on medication management to patients and caregivers at or soon after discharge.

Specific drugs and polypharmacy

As shown by previous studies, drugs that were prescribed more often accounted for approximately half of the medication discrepancies. Specifically for several classes of drugs, anticoagulants accounted for 13%, diuretics accounted for 10%, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) accounted for 10%, and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) accounted for 7% of medication discrepancies generated during transitional care [17]. Moreover, in a prospective analysis of 3695 patient-episodes, it showed that patients experiencing ADRs were more likely to take diuretics, opioid analgesics and anticoagulants, leading to a longer length of hospital stay and a higher financial cost to both patients and healthcare systems [25]. Therefore, these classes of drugs are considered as frequent ones for DRPs during both hospitalization and post-discharge transition. The problem of overprescribing PPIs has been reported in multiple studies [26, 27], which could be significantly prevented by transitional interventions [13] for protecting patients from long-term negative effects such as enteric infections.

In addition, polypharmacy is also regarded as a contributing factor for DRPs. For instance, patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) often take an average of 6 to 12 medications, and the incidence of polypharmacy was approximately 80% in this cohort [28]. Therefore, polypharmacy and/or high-risk drugs (e.g., anticoagulants) are considered as high-risk factors for post-discharge DRPs. The risk of ADEs was increased by 13% when two drugs are used together, by 58% when using five drugs, and reached as high as 82% when using seven or more drugs simultaneously [29]. Such risks of ADEs could be reduced by transitional care interventions utilizing multicomponent approaches and reconciled medications [30].

Patient-related factors

Patient-related factors often include adverse drug reactions (ADRs), intolerance, lack of knowledge about drugs, lack of motivation in taking drugs, as well as financial barriers [31]. Among these factors, 70% were intentional non-adherence, leading to the discrepancies between registered prescriptions and patients’ actual use of drugs [32]. Thus, it is critical for medical professionals to identify each individual’s actual barriers at an earliest timepoint and find out a solution to each barrier to avoid intentional non-adherence.

System-related factors

In a study of participants at the age of 50 + years, the most common contributing factor for system-level medication discrepancies was incomplete or inaccurate discharge instructions (also known as error of omission) [13, 33], which are yet modifiable by careful medical reviews for optimizing in-hospital drugs and for standardizing discharge summaries and medication lists. System-level discrepancies may also occur during the long-term medical care after acute discharge, as noticed in a recent study in Denmark that Shared Medication Record (SMR) was not updated regularly by GPs and information on drug changes was missing after discharge or at referral [34]. Meanwhile, DRPs in SMR including dispensing errors at hospital and missing electronic prescriptions have also been found [34]. In one previous study, it showed that nurses identified more system-level discrepancies (in 69% of participants) than patient-level discrepancies (in 40% of participants) during transitional period [33], whereas in other studies, a nearly equal proportion of these two types of discrepancies have been detected by nurses [17, 35]. Additionally, the presence of conflicting information from different sources or confusion between brand and generic names, which may confuse patients without sufficient guidance or education of relevant knowledge, is another frequent contributing factor for system-level medication discrepancies [33]. In the same study [33], duplication has also been pointed out as one of the most frequent contributing factors, which could be a consequence of (1) an inaccurate medication history collected at admission; (2) failure to reconcile home drugs recorded during admission with drugs shown on discharge summary; (3) ineffective or insufficient discharge education on drugs; (4) multiple prescribers who do not get access to patients’ accurate medication lists; (5) changes during formulary substitution. As studied previously, medication discrepancies identified on transition from a hospital to a skilled nursing facility observed that 19% were therapeutic duplications [36].

Medication reconciliation

Medication reconciliation is a systematic process with a series of steps, which includes listing medications that are currently under and needed, comparing these lists and generating a new list, as well as communicating with patients and care providers subsequently on the new list [37]. The comparison of these medication lists may be performed at admission, transfer or discharge to avoid inconsistencies [38], which plays a critical part in reducing medication discrepancies and preventing DRPs during transitional care. Obtaining the best possible medication history has been revealed to be able to identify medication discrepancies [39]. A wide range of information sources could be acquired to meet the goal, with patients themselves and their caregivers as the main source of information collection. Other sources such as hospital medical records and shared electronic health records may also be utilized to enhance the accuracy of the collected history [40]. Apart from verification of medication history, medication reconciliation also involves in-depth assessment and clarification including reevaluation of drug’s indications and contraindications, appropriate doses for the patient and possible ADEs, by using the evaluator’s specific knowledge. Medication reconciliation also requires documentation of any changes made to the medication list to resolve discrepancies and optimize reconciled medication regimens. In addition, appropriate monitoring whilst taking the drugs, as well as sufficient laboratory tests for determining the continuation, dosage adjustment or termination of the drugs (e.g., as per renal or liver functions), are also parts of the medication reconciliation. It has been demonstrated that patients on Gastroenterology wards may benefit more from drug safety checks, whereas patients on Neurology wards may particularly benefit from drug-drug interaction checks, as compared to those in Urology department [16].

Nurses’ role in transitional care for preventing DRPs

The handling of these DRPs was very time-consuming for healthcare professionals and costly for healthcare resources, therefore, it was widely recommended that more cross-sectoral interdisciplinary resources being put into the transitional care to prevent DRPs instead of solving the problems after they occur. After discharge, efficient communication and adequate follow-up is utmost necessary, since patients may confront adherence problems due to insufficient knowledge on drugs they take or inadequate understanding about their treatment or regimen complexity [41, 42]. Transitional care interventions vary in the cohort they target, the goal they set, the services and duration of support they provide, and the types of service providers. Various health professionals, such as clinical pharmacists and/or clinical pharmacologists, as well as physicians, may be involved in the prevention of DRPs during transitional period [43]. Here, we specifically focus on the nurse-led transitional care interventions targeting older adults in the prevention of DRPs (Table 1) to provide a profound thinking about the optimization of such interventions.

Information collection and evaluation

Documentation of identified discrepancies as well as resolutions of these discrepancies are of profound importance in the medication management during transitional period. It is a common responsibility for nurses to compare and contrast medication lists when a patient is transferred from one setting to another. To complete this task, nursing staff should gather all available medication lists, usually with discharge summary as the primary source. Nurses could assess the quality of discharge letter by using the following definition: a description of the active ingredient and an exemplary brand name, an explanation of drug changes in comparison to the home medication lists, a visualized presentation of the explanation next to each drug, and a recommendation for treatment duration of short-term drugs. Hohmann et al. [60] have conducted a clinical study on 312 patients with stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA) who were randomized into intervention group (education + a detailed medication list) or control group (a brief discharge letter). Within a 3-month follow-up, the intervention group showed a higher rate (90.9%) of medication adherence as compared to that of the control group (83.3%) [60], indicating that the detailed medication list might be a good tool for information collection and evaluation. In addition, Meyer-Massetti et al. [61] have conducted a nurse-pharmacist collaboration study on 100 discharged patients receiving ≥ 4 medications, in which the quality of discharged medication prescriptions was effectively assessed using a PCNE Type 2b Medication Review by nurses.

Notably, patient interview is another main source of information to identify medication discrepancies, and these discrepancies should be incorporated into the final medication list. A home visit is recommended to be paid by a care coordinator within one week post discharge, since preventable ADEs often occur with the first 1–2 weeks post discharge [62, 63]. During the face-to-face visits or telephone calls, the interviewees should be asked to bring all the drugs (both prescribed and over-the-counter) to the visit or near the phone before questioning. Home visits are superior source of information to phone call visits for the following reasons. Firstly, home visits make patients feel more comfortable to share experiences and concerns about their drugs and more receptive to counselling due to face-to-face encounters, which were often used in nurse-pharmacist collaboration studies, either by integrating pharmacists into a home nursing service to identify DRPs [64], or reporting nurse-identified significant DRPs during home visits to community pharmacists [65]. Secondly, some specific risk factors, such as multiple storage locations and inappropriate storage conditions, can be more easily identified in patients’ own surroundings during home visits by nurses [66]. In addition, expired or spare drugs that are no longer prescribed should also be carefully checked to ensure that they are disposed of. The quantity of unused or expired drugs due to non-adherence, overprescribing, change of medical condition or therapeutic regimens could be directly obtained by pill counting or patient’s self-report. Thirdly, difficulties in memorizing or pronouncing drug names or accurately recalling dosage were observed in many participants in different studies, particularly for those with low health literacy and for older adults. The effectiveness in identifying and resolving medication discrepancies in patients during transitional period has been demonstrated by a pharmacist-nurse collaborated intervention [35]. As an alternative approach for post-discharge follow-up, telephone-based nurse-led models have shown some benefits in reducing 30-day rehospitalization rates from 34 to 23% [44] and in yielding estimated net healthcare cost savings of $663 per person [45]. Similarly, it was impressively reported that the post-discharge evaluation for care needs and medication reconciliation delivered by a primary care-based nurse care coordinator has successfully reduced post-discharge costs among 638 Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries in the USA [46]. However, in two large-scaled RCTs on older patients and discharged from the emergency department (ED), a single scripted phone call from a trained nurse did not significantly alter the 30-day unplanned readmission rate, ED return or death [47, 48], indicating that phone call visits alone may be insufficient to produce good health-related outcome for patients discharged from acute conditions.

Furthermore, since duplication of therapy is one of the profound medication discrepancies affecting safety issues for older patients, it should be evaluated via listing drugs by their indications or therapeutic drug class [67]. Although it is frequently seen when a given indication is treated by more than one drug, it is rare to treat with multiple drugs from the same therapeutic drug class.

Several tools have been proposed and developed for further investigation of potential medication discrepancies. At hospital discharge, nursing staff may determine the Medication Regimen Complexity Index (MRCI) [68] based on the discharge prescription, and a higher MRCI represents a more complex regimen. At post-discharge visits, the Medication Discrepancy Tool (MDT) is a tool for identifying medication discrepancies and guiding resolutions particularly during transition between sites of care [33]; whereas the Comprehensive Medication Review (CMR) [69] could be used to evaluate ADRs (e.g., allergies), contraindications, treatment duplication, drug-drug or drug-disease interactions, dosages, treatment durations, abuse or misuse of drugs. Possible ADEs could be assessed by using a trigger list developed by Sino et al. [70] Standardized information collection using certain templates may improve the rates of high-quality documentation and reduce the rates of patients’ mortality within a year after discharge [71]. A structured drug report with an accurate list have been demonstrated in multiple studies to reduce the rate of medication errors and enhance patients’ adherence during the transitional care [72,73,74]. Recently, electronic systems and applications have been developed for the purpose of improving medication management during the transitional care. For instance, mHealth, an app developed for diabetic management, enabled users to view their recent prescriptions, record their daily administration of all drugs, and receive reminder to take drugs [75].

Communication and education

Poor communication has been reported as one of the most important contributing factors for medication discrepancies and readmissions during transitional care [76]. Therefore, a comprehensive medication reconciliation strategy should include effective communication with the patients, their caregivers or responsible person in their institutional facilities, or both. It is frequently the nurses’ role to lead communications among patients/caregivers, hospitals, and the patients’ primary care providers during the transitional period. Direct communication is vitally important for collecting information that may require close monitoring and follow-up, which is a pivotal component when determining the plan of care. During the post-discharge contact, effective communication should enable patients and their caregivers to actively participate and express their beliefs, demands or concerns regarding their drugs [77], identify patient’s goal or preferences and address issues by asking if they have any questions [78]. This is particularly important since patients’ willingness to initiate and continue prescribed drugs is largely determined by their judgement on personal needs for the drug relative to their concerns about taking it [79]. Improved health-related outcomes as well as reduced healthcare costs have been observed when conducting interventions with patients’ goals as key motivators [80]. A combination of strategies emphasizing trust and plain language communications, as well as coordinating post-discharge activities such as medical referral and follow-up appointments may be used. It is necessary to instruct patients about the arrangement and importance of their follow-up appointments with clear verbal instructions. A positive communication involves explanations of the current situation, confirmation of the understanding of the situation and discussion about the future strategies. However, it is noteworthy that for older multi-lingual and cognitively impaired populations, higher-intensity interventions may be applied to improve discharge experience outcomes [50].

In addition, insufficient education and follow-up has been associated with reduced ability of patients to absorb information on drug-related information [81], which may cause misinformation or confusion and raise DRPs. In contrast, patients with a higher level of knowledge showed a better medication adherence and post-discharge behavior, indicating the essentiality of developing interventional programs that focus particularly on promoting patients’ knowledge. The lack of patients’ knowledge on drugs, which could be evaluated based on the study of Kwint et al. [82], may be resolved by follow-up visits during transitional period. It has been demonstrated that a 6-week nurse-led medication self-management intervention significantly improved medication adherence in an RCT on older individuals with multimorbidity [53], and a 20-week nurse-led training program consisting health education and motivational meetings improved medication adherence, health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and health-related indicators (e.g., blood pressure, cholesterol, body mass index (BMI), etc.) [54], suggesting nurses’ important role as a medication educator and motivator during transitional period. Appropriately conducted education with recall-promoting and teach-back techniques may allow for reiteration and refresh of important drug information, which has been shown to be effective in different settings [83]. The teach-back technique requires patients/caregivers to repeat their understanding of the drugs and teach the nurses who have provided the information during the education, otherwise, reeducation may be applied. To fulfill this task, nurses should be cognizant of drugs frequently implicated in discrepancies and be aware of drugs commonly used in the hospital that may not require long-term use. For instance, some drugs are prescribed PRN for pain or nausea should be discontinued on discharge despite frequency of dosing or patient-reported symptoms, which may result in uncontrolled pain or other side effects. Digital technologies such as mobile apps and multimedia have been increasingly employed in patient education. Previous studies have revealed that patients counselled via utilization of tablets were more likely to feel competent to make health decisions with their doctors, and were more willing to follow the doctors’ instructions [84]. In addition, individuals who used tablets for patient education gained more knowledge on self-injection of drugs compared with those receiving conventional explanations from nurses [85]. Furthermore, the self-management education with understandable and culturally-adapted materials was well acceptable and applicable among patients [86], resulting in higher self-efficacy [87].

Enhancement of adherence

Typical medication adherence barriers for patients taking regular drugs for a long term are usually related to patients themselves, lack of appropriate care supports or medical resources, or system issues. Intentional nonadherence was the most common contributing factor for patient-level discrepancies. It was reported that only 78% of all electronic prescriptions and only 72% of new prescriptions were filled [88]. When digging out the reasons behind, most frequently, patients decided not to fill a prescription because they perceived the drugs were not necessary or helpful. Approximately 30% of the patient-level discrepancies were attributed to nonintentional nonadherence [33], which was due to patients not knowing that they were supposed to take a drug or a lack of knowledge about the dose and frequency of taking the drug as prescribed.

Firstly, delineation of patient’s actual drug taking behaviors is critical to identify the self-related adherence barriers. These behaviors include how often the patient misses a dose, whether there is a pattern to the dose missing and whether there is any difficulty administering or tolerating drugs. For instance, some drugs could be difficult to swallow or may cause stomach discomfort, while others (e.g., inhalers or injectables) may have complicated instructions for administration. There might be some other practical barriers for drug intake, e.g., forgetfulness, organizational problems or difficulties with opening pill containers, which can all be detected and solved by follow-up nurses. Notably, drug taking behaviors and adherence may sometimes be associated with individual’s beliefs and cultural background [79]. Occasionally, the patients may not be the best information providers, then interview with caregivers or examination of medical records from the facilities may provide a more accurate picture.

Secondly, enhancement of patient’s medication adherence is the main target with significant effectiveness in multiple nurse-led intervention studies [55]. The adherence could be evaluated and monitored by direct observation of drug consumption, symptomatic improvement, drug concentration in the blood or urine, pill counting and patient interview. Notably, adherence is possibly to be overestimated when using self-reported data compared with registry-reported observations [56]. To reinforce patients’ compliance with actual drugs, patients were taught in group classes (e.g., a fitness program/gym, smoking cessation program or healthy eating classes) regularly to establish lifestyle modification goals and develop personal action plans in the collaboration of responsible nurses [19].

Coordination among healthcare professionals

Depending on the nurses’ scope of practice, his/her role may be as a collaborator to report identified medication discrepancies and DRPs to the patient’s multidisciplinary medical team (specialist, GP, pharmacist, nutritionist, physical therapists, etc.) [61, 66]. Coordination among healthcare professionals from different institutions by nurse coaches was detected as the power frame of the implementation of a health coaching program for stroke survivors and their caregivers [59]. Such coordination may facilitate tight linkages to patient’s specialists, other primary healthcare providers, as well as community care services for older adults and caregivers [89].

Nurses are ideally positioned as ‘Liaison Officers’ who uniquely identify patients at high risk for DRPs and facilitates communications among different disciplines (specialists, pharmacists, primary care physicians, nursing home healthcare workers, etc.) and with patients and their families (Fig. 2). They are often the healthcare providers that contact most directly and frequently with patients and caregivers, and patients often feel more comfortable discussing symptoms and concerns with nurses, enabling earlier detection and report of potential side effects and ADRs, which may have not been identified by other healthcare professionals. Furthermore, nurses are frontline healthcare providers who are frequently involved in drug administration, providing them with a unique opportunity to monitor and record potential ADRs at an early stage [90]. A previously proposed evidence-based nurse-led transitional care model has been verified in multiple settings and medical providers to effectively improve the quality of care for individuals and families while reducing healthcare costs [91, 92], and the use of a transitional care bundle, which was delivered by nursing staff, pharmacy staff and physicians and developed to meet needs of patients, has reduced the medication errors in patients with a high risk of readmissions [93]. Nurses may play a crucial role in delivering this bundle as a ‘coordinator’ during transitional period. Specifically, at admission, how drugs had been taken by the patients would be discussed with nurses and physicians. In addition, education on discharge would also be provided by the nurses [93]. The main target of these interventions is to develop an evidence-based comprehensive and individualized plan of care to improve coordination of care and meet the needs and goals of patients and families, while more large-scaled RCTs are needed to test the effects of these nurse-led interventions.

Conclusions

It has been shown that age, specific drugs and polypharmacy, as well as some patient- and system-related factors all contribute to a higher prevalence of transitional DRPs, most of which could be largely prevented by enhancing nurse-led multidisciplinary medication reconciliation. Nurses are ideally positioned as ‘Liaison Officers’ for preventing DRPs during transitional period, which includes information collection and evaluation, communication and education, enhancement of medication adherence, and coordination among healthcare professionals. Therefore, Nurse-led strategies for medication management can be implemented to prevent or solve DRPs during the high-risk transitional period, and subsequently improve patients’ satisfaction and health-related outcomes, prevent the unnecessary loss and waste of medical expenditure and resources, and increase the efficiency of the multidisciplinary teamwork during transitional care.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Coleman EA (2003) Falling through the cracks: challenges and opportunities for improving transitional care for persons with continuous complex care needs. J Am Geriatr Soc 51:549–555. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51185.x

Naylor MD, Aiken LH, Kurtzman ET et al (2011) The care span: the importance of transitional care in achieving health reform. Health Aff (Millwood) 30:746–754. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0041

Coleman EA, Boult C, American Geriatrics Society Health Care Systems C (2003) Improving the quality of transitional care for persons with complex care needs. J Am Geriatr Soc 51:556–557. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51186.x

Naylor MD, Shaid EC, Carpenter D et al (2017) Components of comprehensive and effective transitional care. J Am Geriatr Soc 65:1119–1125. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14782

Marcuccilli L, Casida JJ, Bakas T et al (2014) Family caregivers’ inside perspectives: caring for an adult with a left ventricular assist device as a destination therapy. Prog Transpl 24:332–340. https://doi.org/10.7182/pit2014684

Balaban RB, Galbraith AA, Burns ME et al (2015) A patient Navigator intervention to Reduce Hospital readmissions among high-risk safety-net patients: a Randomized Controlled Trial. J Gen Intern Med 30:907–915. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-015-3185-x

Laatikainen O, Miettunen J, Sneck S et al (2017) The prevalence of medication-related adverse events in inpatients-a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 73:1539–1549. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-017-2330-3

Montane E, Arellano AL, Sanz Y et al (2018) Drug-related deaths in hospital inpatients: a retrospective cohort study. Br J Clin Pharmacol 84:542–552. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcp.13471

Elliott RA, Camacho E, Jankovic D et al (2021) Economic analysis of the prevalence and clinical and economic burden of medication error in England. BMJ Qual Saf 30:96–105. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2019-010206

Lindquist LA, Go L, Fleisher J et al (2012) Relationship of health literacy to intentional and unintentional non-adherence of hospital discharge medications. J Gen Intern Med 27:173–178. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-011-1886-3

Aronson JK (2009) Medication errors: what they are, how they happen, and how to avoid them. QJM 102:513–521. https://doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcp052

Kripalani S, Jackson AT, Schnipper JL et al (2007) Promoting effective transitions of care at hospital discharge: a review of key issues for hospitalists. J Hosp Med 2:314–323. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.228

Freyer J, Kasprick L, Sultzer R et al (2018) A dual intervention in geriatric patients to prevent drug-related problems and improve discharge management. Int J Clin Pharm 40:1189–1198. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-018-0643-7

Blix HS, Viktil KK, Reikvam A et al (2004) The majority of hospitalised patients have drug-related problems: results from a prospective study in general hospitals. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 60:651–658. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-004-0830-4

Ruiz-Millo O, Climente-Marti M, Galbis-Bernacer AM et al (2017) Clinical impact of an interdisciplinary patient safety program for managing drug-related problems in a long-term care hospital. Int J Clin Pharm 39:1201–1210. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-017-0548-x

Lenssen R, Heidenreich A, Schulz JB et al (2016) Analysis of drug-related problems in three departments of a German University hospital. Int J Clin Pharm 38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-015-0213-1. :119 – 26

Coleman EA, Smith JD, Raha D et al (2005) Posthospital medication discrepancies: prevalence and contributing factors. Arch Intern Med 165:1842–1847. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.165.16.1842

Silva AE, Reis AM, Miasso AI et al (2011) Adverse drug events in a sentinel hospital in the state of Goias, Brazil. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem 19:378–386. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0104-11692011000200021

Borgsteede SD, Karapinar-Carkit F, Hoffmann E et al (2011) Information needs about medication according to patients discharged from a general hospital. Patient Educ Couns 83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2010.05.020. :22 – 8

Mueller SK, Sponsler KC, Kripalani S et al (2012) Hospital-based medication reconciliation practices: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med 172:1057–1069. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2012.2246

Trompeter JM, McMillan AN, Rager ML et al (2015) Medication discrepancies during transitions of care: a comparison study. J Healthc Qual 37:325–332. https://doi.org/10.1111/jhq.12061

Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S et al (2006) The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med 166:1822–1828. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.17.1822

Tache SV, Sonnichsen A, Ashcroft DM (2011) Prevalence of adverse drug events in ambulatory care: a systematic review. Ann Pharmacother 45:977–989. https://doi.org/10.1345/aph.1P627

Cawthon C, Walia S, Osborn CY et al (2012) Improving care transitions: the patient perspective. J Health Commun 17 Suppl. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2012.712619. 3:312 – 24

Davies EC, Green CF, Taylor S et al (2009) Adverse drug reactions in hospital in-patients: a prospective analysis of 3695 patient-episodes. PLoS ONE 4:e4439. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0004439

Schepisi R, Fusco S, Sganga F et al (2016) Inappropriate use of Proton Pump inhibitors in Elderly patients discharged from Acute Care hospitals. J Nutr Health Aging 20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-015-0642-5. :665 – 70

Batuwitage BT, Kingham JG, Morgan NE et al (2007) Inappropriate prescribing of proton pump inhibitors in primary care. Postgrad Med J 83. https://doi.org/10.1136/pgmj.2006.051151. :66 – 8

Evans M, Lopau K (2020) The transition clinic in chronic kidney disease care. Nephrol Dial Transpl 35:ii4–ii10. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfaa022

Prybys KMK, Hanna J, Gee A, Chyka P (2002) Polypharmacy in the elderly: clinical challenges in emergency practice: part 1: overview, etiology, and drug interactions. Emerg Med Rep 23:145–153

Laugaland K, Aase K, Barach P (2012) Interventions to improve patient safety in transitional care–a review of the evidence. Work 41 Suppl 12915–2924. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-2012-0544-2915

Brown MT, Bussell JK (2011) Medication adherence: WHO cares? Mayo Clin Proc 86:304 – 14. https://doi.org/10.4065/mcp.2010.0575

Bulow C, Noergaard J, Faerch KU et al (2021) Causes of discrepancies between medications listed in the national electronic prescribing system and patients’ actual use of medications. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 129:221–231. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcpt.13626

Corbett CF, Setter SM, Daratha KB et al (2010) Nurse identified hospital to home medication discrepancies: implications for improving transitional care. Geriatr Nurs. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2010.03.006. 31:188 – 96

Sorensen CA, Jeffery L, Falhof J et al (2023) Developing and piloting a cross-sectoral hospital pharmacist intervention for patients in transition between hospital and general practice. Ther Adv Drug Saf 14:20420986231159221. https://doi.org/10.1177/20420986231159221

Setter SM, Corbett CF, Neumiller JJ et al (2009) Effectiveness of a pharmacist-nurse intervention on resolving medication discrepancies for patients transitioning from hospital to home health care. Am J Health Syst Pharm 66:2027–2031. https://doi.org/10.2146/ajhp080582

Delate T, Chester EA, Stubbings TW et al (2008) Clinical outcomes of a home-based medication reconciliation program after discharge from a skilled nursing facility. Pharmacotherapy 28:444–452. https://doi.org/10.1592/phco.28.4.444

Aronson J (2017) Medication reconciliation. BMJ 356:i5336. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i5336

Ceschi A, Noseda R, Pironi M et al (2021) Effect of medication reconciliation at hospital admission on 30-day returns to hospital: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open 4:e2124672. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.24672

Kabir R, Liaw S, Cerise J et al (2023) Obtaining the best possible medication history at hospital admission: description of a Pharmacy Technician-Driven Program to identify medication discrepancies. J Pharm Pract 36:19–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/08971900211021254

Oliveira J, Cabral AC, Lavrador M et al (2020) Contribution of different patient information sources to create the best possible medication history. Acta Med Port 33:384–389. https://doi.org/10.20344/amp.12082

Makaryus AN, Friedman EA (2005) Patients’ understanding of their treatment plans and diagnosis at discharge. Mayo Clin Proc 80:991–994. https://doi.org/10.4065/80.8.991

Artinian L (2006) Patients’ lack of knowledge of their medications and diagnosis at discharge. Mayo Clin Proc 81:133 author reply 133. https://doi.org/10.4065/81.1.133-a

Carollo M, Boccardi V, Crisafulli S et al (2024) Medication review and deprescribing in different healthcare settings: a position statement from an Italian scientific consortium. Aging Clin Exp Res 36:63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-023-02679-2

Kind AJ, Jensen L, Barczi S et al (2012) Low-cost transitional care with nurse managers making mostly phone contact with patients cut rehospitalization at a VA hospital. Health Aff (Millwood) 31:2659–2668. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0366

Kind AJ, Brenny-Fitzpatrick M, Leahy-Gross K et al (2016) Harnessing protocolized adaptation in dissemination: successful implementation and sustainment of the veterans affairs coordinated-transitional care program in a non-veterans affairs hospital. J Am Geriatr Soc 64:409–416. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.13935

Kranker K, Barterian LM, Sarwar R et al (2018) Rural hospital transitional care program reduces Medicare spending. Am J Manag Care 24:256–260

Biese KJ, Busby-Whitehead J, Cai J et al (2018) Telephone follow-up for older adults discharged to home from the emergency department: a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 66:452–458. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.15142

van Loon-van Gaalen M, van der Linden MC, Gussekloo J et al (2021) Telephone follow-up to reduce unplanned hospital returns for older emergency department patients: a randomized trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 69:3157–3166. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.17336

Taylor SP, Murphy S, Rios A et al (2022) Effect of a multicomponent sepsis transition and recovery program on mortality and readmissions after sepsis: the improving morbidity during post-acute care transitions for sepsis randomized clinical trial. Crit Care Med 50:469–479. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000005300

Chan B, Goldman LE, Sarkar U et al (2015) The Effect of a care transition intervention on the patient experience of older multi-lingual adults in the Safety net: results of a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med 30:1788–1794. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-015-3362-y

Fuller A, Jenkins W, Doherty M et al (2020) Nurse-led care is preferred over GP-led care of gout and improves gout outcomes: results of Nottingham gout treatment trial follow-up study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 59:575–579. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kez333

Cui X, Zhou X, Ma LL et al (2019) A nurse-led structured education program improves self-management skills and reduces hospital readmissions in patients with chronic heart failure: a randomized and controlled trial in China. Rural Remote Health 19:5270. https://doi.org/10.22605/RRH5270

Yang C, Lee DTF, Wang X et al (2022) Effects of a nurse-led medication self-management intervention on medication adherence and health outcomes in older people with multimorbidity: a randomised controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud 134:104314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2022.104314

Kolcu M, Ergun A (2020) Effect of a nurse-led hypertension management program on quality of life, medication adherence and hypertension management in older adults: a randomized controlled trial. Geriatr Gerontol Int 20:1182–1189. https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.14068

Kes D, Polat U (2022) The effect of nurse-led telephone support on adherence to blood pressure control and drug treatment in individuals with primary hypertension: a randomized controlled study. Int J Nurs Pract 28:e12995. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijn.12995

Haile ST, Joelsson-Alm E, Johansson UB et al (2022) Effects of a person-centred, nurse-led follow-up programme on adherence to prescribed medication among patients surgically treated for intermittent claudication: randomized clinical trial. Br J Surg 109:846–856. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjs/znac241

Lisby M, Klingenberg M, Ahrensberg JM et al (2019) Clinical impact of a comprehensive nurse-led discharge intervention on patients being discharged home from an acute medical unit: randomised controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud 100:103411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.103411

Liang HY, Hann Lin L, Yu Chang C et al (2021) Effectiveness of a nurse-led tele-homecare program for patients with multiple chronic illnesses and a high risk for readmission: a randomized controlled trial. J Nurs Scholarsh 53:161–170. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnu.12622

Lin S, Xie S, Zhou J et al (2023) Stroke survivors’, caregivers’ and nurse coaches’ perspectives on health coaching program towards hospital-to-home transition care: a qualitative descriptive process evaluation. J Clin Nurs 32:6533–6544. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.16590

Hohmann C, Neumann-Haefelin T, Klotz JM et al (2013) Adherence to hospital discharge medication in patients with ischemic stroke: a prospective, interventional 2-phase study. Stroke 44:522–524. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.678847

Meyer-Massetti C, Hofstetter V, Hedinger-Grogg B et al (2018) Medication-related problems during transfer from hospital to home care: baseline data from Switzerland. Int J Clin Pharm 40:1614–1620. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-018-0728-3

Roughead EE, Kalisch LM, Ramsay EN et al (2011) Continuity of care: when do patients visit community healthcare providers after leaving hospital? Intern Med J 41:662–667. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1445-5994.2009.02105.x

Kanaan AO, Donovan JL, Duchin NP et al (2013) Adverse drug events after hospital discharge in older adults: types, severity, and involvement of beers criteria medications. J Am Geriatr Soc 61:1894–1899. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.12504

Lee CY, Beanland C, Goeman D et al (2018) Improving medication safety for home nursing clients: a prospective observational study of a novel clinical pharmacy service-the visiting pharmacist (ViP) study. J Clin Pharm Ther 43:813–821. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpt.12712

Toivo T, Airaksinen M, Dimitrow M et al (2019) Enhanced coordination of care to reduce medication risks in older home care clients in primary care: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Geriatr 19:332. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-019-1353-2

Verweij L, Petri ACM, MacNeil-Vroomen JL et al (2022) The Cardiac Care Bridge transitional care program for the management of older high-risk cardiac patients: an economic evaluation alongside a randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE 17:e0263130. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0263130

Greene HA, Slattum PW (2006) Resolving medication discrepancies. Consult Pharm 21:643–647. https://doi.org/10.4140/tcp.n.2006.643

George J, Phun YT, Bailey MJ et al (2004) Development and validation of the medication regimen complexity index. Ann Pharmacother 38:1369–1376. https://doi.org/10.1345/aph.1D479

Nathan A, Goodyer L, Lovejoy A et al (1999) Brown bag’ medication reviews as a means of optimizing patients’ use of medication and of identifying potential clinical problems. Fam Pract 16:278–282. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/16.3.278

Sino CG, Bouvy ML, Jansen PA et al (2013) Signs and symptoms indicative of potential adverse drug reactions in homecare patients. J Am Med Dir Assoc 14:920–925. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2013.09.014

Blomberg BA, Mulligan RC, Staub SJ et al (2018) Handing off the older patient: Improved Documentation of Geriatric Assessment in transitions of Care. J Am Geriatr Soc 66:401–406. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.15237

Bergkvist A, Midlov P, Hoglund P et al (2009) Improved quality in the hospital discharge summary reduces medication errors–LIMM: Landskrona Integrated Medicines Management. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 65:1037–1046. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-009-0680-1

Midlov P, Holmdahl L, Eriksson T et al (2008) Medication report reduces number of medication errors when elderly patients are discharged from hospital. Pharm World Sci 30:92–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-007-9149-4

Hohmann C, Neumann-Haefelin T, Klotz JM et al (2014) Providing systematic detailed information on medication upon hospital discharge as an important step towards improved transitional care. J Clin Pharm Ther 39:286–291. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpt.12140

Zhang W, Yang P, Wang H et al (2022) The effectiveness of a mhealth-based integrated hospital-community-home program for people with type 2 diabetes in transitional care: a protocol for a multicenter pragmatic randomized controlled trial. BMC Prim Care 23:196. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-022-01814-8

Mora K, Dorrejo XM, Carreon KM et al (2017) Nurse practitioner-led transitional care interventions: an integrative review. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract 29:773–790. https://doi.org/10.1002/2327-6924.12509

Robinson JH, Callister LC, Berry JA et al (2008) Patient-centered care and adherence: definitions and applications to improve outcomes. J Am Acad Nurse Pract 20:600–607. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-7599.2008.00360.x

Ensing HT, Koster ES, Stuijt CC et al (2015) Bridging the gap between hospital and primary care: the pharmacist home visit. Int J Clin Pharm 37:430–434. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-015-0093-4

Linn AJ, van Weert JCM, van Dijk L et al (2016) The value of nurses’ tailored communication when discussing medicines: exploring the relationship between satisfaction, beliefs and adherence. J Health Psychol 21:798–807. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105314539529

McCauley KM, Bixby MB, Naylor MD (2006) Advanced practice nurse strategies to improve outcomes and reduce cost in elders with heart failure. Dis Manag 9:302–310. https://doi.org/10.1089/dis.2006.9.302

Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO et al (2007) Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA 297:831–841. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.297.8.831

Kwint HF, Faber A, Gussekloo J et al (2012) The contribution of patient interviews to the identification of drug-related problems in home medication review. J Clin Pharm Ther 37:674–680. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2710.2012.01370.x

Linn AJ, van Dijk L, Smit EG et al (2013) May you never forget what is worth remembering: the relation between recall of medical information and medication adherence in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis 7:e543–e550. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crohns.2013.04.001

Schooley B, Singh A, Hikmet N et al (2020) Integrated Digital Patient Education at the Bedside for patients with chronic conditions: Observational Study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 8:e22947. https://doi.org/10.2196/22947

Zhitomirsky Y, Aharony N (2023) The Effect of a Patient Education Multimodal Digital Platform on Knowledge Acquisition, Self-efficacy, and patient satisfaction. Comput Inf Nurs 41:356–364. https://doi.org/10.1097/CIN.0000000000000939

Sinclair KA, Zamora-Kapoor A, Townsend-Ing C et al (2020) Implementation outcomes of a culturally adapted diabetes self-management education intervention for native hawaiians and Pacific islanders. BMC Public Health 20:1579. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09690-6

Furukawa E, Okuhara T, Okada H et al (2022) Translation, cross-cultural adaptation, and validation of the Japanese version of the patient education materials assessment tool (PEMAT). Int J Environ Res Public Health 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192315763

Fischer MA, Stedman MR, Lii J et al (2010) Primary medication non-adherence: analysis of 195,930 electronic prescriptions. J Gen Intern Med 25:284–290. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-010-1253-9

Yous ML, Ganann R, Ploeg J et al (2023) Older adults’ experiences and perceived impacts of the aging, community and health research unit-community partnership program (ACHRU-CPP) for diabetes self-management in Canada: a qualitative descriptive study. BMJ Open 13:e068694. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-068694

Schjott J, Pettersen TR, Andreassen LM et al (2023) Nurses as adverse drug reaction reporting advocates. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 22:765–768. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurjcn/zvac113

Hirschman KB, Shaid E, McCauley K et al (2015) Continuity of care: the transitional care model. Online J Issues Nurs 20:1

Rivera S, Behnke L, Henderson MJ (2022) Transitions of care considerations for nephrology patients. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am 34:491–500. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cnc.2022.07.006

Rice YB, Barnes CA, Rastogi R et al (2016) Tackling 30-Day, all-cause readmissions with a patient-centered transitional care bundle. Popul Health Manag 19:56–62. https://doi.org/10.1089/pop.2014.0163

Jankowska-Polanska B, Uchmanowicz I, Dudek K et al (2016) Relationship between patients’ knowledge and medication adherence among patients with hypertension. Patient Prefer Adherence 10:2437–2447. https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S117269

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.H.: Conceptualization; Investigation; Resources; Visualization; Writing-original draftJ.C.: Investigation; Visualization; Writing-original draftY.X.: Project administration; Writing-review & editingP.H.: Project administration; Writing-review & editingL.H.: Conceptualization; Methodology; Supervision; Writing-review & editingAll authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Han, Y., Chen, J., Xu, Y. et al. Nurse-led medication management as a critical component of transitional care for preventing drug-related problems. Aging Clin Exp Res 36, 151 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-024-02799-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-024-02799-3