Abstract

Given a lack of knowledge about the work happiness of PhD graduates across a range of jobs, we explored which employment sectors graduates were entering, their work happiness and what factors influenced their happiness. We surveyed PhD graduates from two US and one New Zealand university. Analysis of 120 graduate responses revealed that nearly 60% were employed in higher education, mostly in precarious positions. Eighteen percent were employed in government and 18% in the private sector (for-profit), with the remainder in private sector (not-for-profit) and teaching. Approximately 82% were happy with their work, with no significant difference between those inside or outside academia. Qualitative analysis revealed the main factors influencing work happiness were having fulfilling work, a good and supportive work environment, work security, a match between the work, their skillset and career expectation, and a desirable location. The study identifies implications for doctoral training and employers of PhD graduates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

With fierce competition for tenure-track academic jobs in most western countries, many PhD graduates seeking academic positions end up in precarious roles (OECD, 2021; Schafer, 2022). Other graduates, either through a lack of success in academic job searches, or through choice, are entering a range of careers in government and private sector organisations (Germain-Alamartine et al., 2021; Hancock, 2021). Yet the training of PhD students often remains focused on producing future academics (ACOLA, 2016), and several researchers have found that, despite the realities of the job market, many PhD students still have a strong desire to attain academic positions (Hauss et al., 2015; Spronken-Smith et al., 2023). With PhD graduates entering a range of jobs, what is poorly understood is how graduates feel about their employment, especially given a potential mismatch of expectations. Are they happy in positions within or beyond academia? The aim of this article is to explore the jobs PhD graduates entered and determine their happiness and experiences of these jobs. Before describing the research methods, we first define some key terms, and outline research that has investigated levels of work happiness or satisfaction in PhD graduates.

Definitions

Although the terms ‘job’, ‘work’, ‘career’ and ‘employment’ can be used interchangeably, they do have distinct meanings. A job is a specific position or role, while work is a broader and subjective construct, recognising that work may not be for financial gain (contrary to traditional definitions), but serve a range of purposes and meanings (Van der Laan et al., 2023). The term career has been described as an “evolving sequence of a person’s work experience over time” (Arthur et al., 1989, p. 9), thus encompassing a developmental notion. Employment refers to being in paid work, and can include both jobs and careers.

In an overview of the philosophical background and research on happiness, Kesebir and Diener (2008) note the difficulty philosophers have had in defining happiness, with social scientists using the term “subjective well-being (SWB)” as a way to capture happiness. SWB is a broader concept than happiness, encompassing both cognitive and affective evaluations of people’s lives (Diener, 2000, p. 4). The cognitive evaluation includes how we consider our overall (global) satisfaction with life, as well as satisfaction with particular aspects, such as work. The affective evaluation—often equated with happiness—is concerned with our emotional experiences—with frequent experiences of positive emotions and infrequent experiences of negative emotions leading to higher levels of SWB and happiness.

PhD Graduate Views on Happiness in Their Careers

Synthesising research on work happiness is challenging given the range of measures used for happiness, and a lack of studies reporting on perceptions of happiness from graduates in a range of jobs as most studies focus on employment in specific roles. Past research reveals broad agreement on the main influences on work satisfaction amongst PhD graduates: benefits and salary (especially having a permanent contract), promotion opportunities, having work related to the field of specialisation, working conditions, social status, intellectual challenge, degree of independence, location, contribution to society, and level of responsibility (e.g., Cyranoski et al., 2011; Escardibul & Afcha, 2017).

For graduates entering roles in higher education, happiness with work varies greatly, depending on the role obtained. Graduates are happier in secure positions, especially tenured ones (Alfano et al., 2021; Paolo, 2016; Escadibul & Afcha, 2017). Sutherland (2017) found that graduates in academic positions expressed happiness related to their contribution to society, freedom, job satisfaction, and influencing students, while Paolo (2016) also noted the importance of a good match between doctoral skills and their job. Those in precarious roles in academia (e.g., post-doctoral and other fixed-term positions) are less satisfied, commonly citing frustration over a lack of stability and salary (Holley, 2017; McAlpine & Turner, 2012), as well as some feeling unwelcome and isolated (McAlpine & Turner, 2012; Miller & Feldman, 2015).

For PhD graduates going into professional staff roles in higher education, findings indicate graduates being mostly satisfied with their jobs (Berman & Pitman, 2010; Ewing-Cooper & Gallien, 2022). However, some had difficulty gaining professional positions due to perceptions of applicants holding a PhD not being a good fit, or not feeling fully valued, and having fewer possibilities for progression (Berman & Pitman, 2010; Ewing-Cooper & Galline, 2022). Most felt that they were able to use their skillset in their job—in fact one had expected to be devastated by leaving academia, but was happily surprised (Ewing-Cooper & Galline, 2022, p. 105).

PhD graduates in positions involving research (inside or outside academia) are generally happier than those not undertaking research. For example, Hnatkova et al. (2022) analysed employment and interview data for PhD graduates in Europe. They found at least 50% of graduates were engaged in research across all sectors, with higher satisfaction related to intellectual development and opportunities for advancement, a degree of independence, and level of responsibility; there was lower satisfaction with salary and benefits.

Graduates working in the private sector may be the most satisfied with their salary and promotion opportunities, but can find the job content less rewarding, and reportedly a lower match to their doctoral skills (Paolo, 2016). Some studies reporting on graduates in the public sector suggest low levels of work happiness. For example, Paolo (2016) found that graduates in the public sector scored the lowest on all indicators of work satisfaction (earnings, promotion opportunities, job content, and job-skills match).

Given that most studies have focused on only part of the employment sector, with the majority concerning jobs in academia, an opportunity arose amidst a broader study to explore how happy PhD graduates were with their jobs in different employment sectors. The broader study investigated the career readiness of PhD graduates from three research-intensive universities: two in the United States, and a New Zealand university (see Spronken-Smith et al., 2024). During analysis, we noticed some rich data relating to work happiness, which became the focus for this article. Here we address three specific research questions:

-

(1)

Which employment sectors were PhD graduates working in?

-

(2)

What were PhD graduates’ ratings of work happiness in the different employment sectors?

-

(3)

What were the key factors influencing work happiness?

Methods

The broader study of career preparedness used an explanatory sequential mixed methods approach with a survey and follow-up interviews. Here we focus on the survey data only. We recruited PhD graduates from three universities – two in the United States (USU1 and USU2) and one from New Zealand (NZU), which were chosen for pragmatic reasons as the lead author (from NZU) visited the US universities as part of a Fulbright Scholar award. Although the Doctor of Philosophy degree is a universal qualification, the doctoral education system varies globally. In the two US universities, students can enter doctoral study with a Bachelor or Master’s degree and typically engage in one or two years coursework, followed by supervised research for another 3–4 years. In NZ, students enter with a Bachelor of Honours degree (including substantive research) or a Master’s degree and go straight into supervised research, completing in 3–4 years. All three institutions in the study have professional and career development support available for doctoral students.

Two PhD graduating cohorts were selected for study—2011/2012 and 2016/17—as these did not interfere with ongoing PhD career outcomes research by the US Council of Graduate Schools. By choosing two cohorts we hoped to contrast experiences of graduates who had been in employment longer, with those recently employed. Ethical approval was granted by the NZU Human Ethics Committee (Ref: 17/147), with approval for the study obtained from USU1 and USU2.

Our survey was adapted from the US Council of Graduate Schools PhD Career Pathways survey (S. Ortega, pers. comm; see https://cgsnet.org/project/understanding-phd-career-pathways-for-program-improvement/) and comprised six sections, with the section on employment (title of position, name of employer, weekly hours of employment, employment contract, sector and work activities) and work happiness the focus of this article. Participants rated their work happiness using a five-point Likert scale: 1 (very happy) to 5 (very unhappy). This rating was followed by a freeform question asking them to tell us why they gave their happiness rating.

Using institutional databases and contacts, in 2018 we emailed nearly 700 alumni from Humanities and Social Science (HASS) and Science disciplines. We obtained 136 survey responses (19.4% response rate) comprising 84 US graduates and 52 from NZU. Just over half (52.9%) were from the earlier graduating cohort (2011/12), and 55.1% were from Science disciplines (44.8% HASS). Just over half were female (53.6%) and most were domestic students (82.9%). Of the 136, 120 gave employment details, with 85.3% in full-time work and 7.8% part-time.

The employment sectors for participants were categorised as follows: permanent/tenured faculty position; tenure-track; academic professional permanent (e.g., research management or student support roles); academic fixed-term (e.g., postdoctoral fellows, teaching or research fellows); government/public sector; private sector not-for-profit; private sector for-profit (including those establishing their own business); and teaching below tertiary level.

Descriptive statistics were used to show the characteristics of participants, and Fisher’s exact test was used to explore associations between their happiness score and (1) employment sector (academic or outside academia); (2) employment status (permanent or temporary); (3) broad disciplinary area (HASS or Science); (4) year of graduation (2011/12 or 2016/17); and (5) university of study (US1, US2 and NZU). To determine the main factors influencing work happiness, the first author did a conventional content analysis of the freeform responses in the survey data, drawing on the method of Hsieh and Shannon (2005). Coding of the 94 responses generated 261 codes, as graduates could comment on more than one positive or negative factor. These codes were then clustered into subthemes, and then main themes (n = 8), noting whether they were positive or negative experiences. If the ratio of positive to negative comments is higher, then subjective wellbeing (SWB) and happiness should be higher. Quotes were selected to illustrate the positive and/or negative aspects of each theme. Key words were listed from each quote to ascertain word frequencies, with word clouds generated from the lists using ATLAS.ti.

Results

First, we report on employment pathways for survey respondents, then consider perceptions of work happiness, factors influencing work happiness, and finally experiences of jobs in different employment sectors.

Employment Pathways

Of the 120 graduates who provided information about their employment, a third were employed in academic fixed-term positions, with 17.5% in both government positions and private sector (for-profit) (Table 1). Only 9.2% were in permanent or tenured faculty positions, but a further 13.3% were in tenure-track positions. Less common employment was in the private sector (not-for-profit) (4.2%), teaching (2.5%), and permanent academic professional roles (2.5%). Overall, 47.5% were in permanent positions; 52.5% were in temporary roles.

Perceptions of Work Happiness

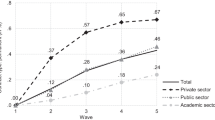

Of those giving employment data, 118 also rated how they felt about their work, with 82.2% being either ‘very happy’ or ‘somewhat happy’, 7.6% were ‘neutral’, and 10.2% were either ‘somewhat unhappy’ or ‘very unhappy’. Of those permanently employed, 49 (46%) reported being ‘very happy’ or ‘somewhat happy’, which is higher than would be expected if there was no relationship between employment status and happiness (Chi-square test, p = 0.003). Table 2 displays the average ratings of happiness according to employment sector. The small sample sizes in the different sectors precluded comparisons, so we created broader categories. Statistical analysis showed no evidence of an association between work happiness and (1) academic and non-academic employment, (2) graduating cohort (i.e. no difference in happiness between those who graduated in 2011/12 or 2016/17), (3) broad discipline area (HASS/Science) and (4) university of study.

Factors Influencing Work Happiness

Figure 1 shows a word cloud of the positive (a) and negative (b) comments. The most frequent positive aspects were interesting, colleagues, developing skills, environment, and research, with the negative aspects dominated by nonpermanent, workload, career goals, salary, and imbalance (in the components of their work). presents the factors influencing work happiness and how these were manifest across the employment sectors.

Eight main themes were identified relating to work happiness, and are ranked from most to least mentioned:

-

1.

Work fulfilment (including interest, enjoyment, passion, challenge, degree of autonomy, importance of work, impactful and stimulating);

-

2.

Work environment (including workload, salary, benefits, bureaucracy and space);

-

3.

Relational aspects of work (e.g., leadership, collegiality and culture);

-

4.

Support and development opportunities (e.g., research funding support, collaborative opportunities, possibility for advancement);

-

5.

Work security – whether permanent or temporary;

-

6.

Match to skillset;

-

7.

Match to career goals; and.

-

8.

Location.

A ninth category of ‘other’ was created to capture comments that did not fit into other themes such as those related to visa status, employment pathways, and dislike of the company.

As Table 3 shows, the most prevalent theme was work fulfilment. Of the 85 comments, 73 were positive, mainly related to passion and enjoyment of their position, the interest or challenge of their work, and making an impact. The second most common theme was ‘work environment’, with graduates quite evenly split on whether this was perceived as positive or negative. Key aspects included salary, benefits and workload, which could be viewed positively or negatively depending on what the position entailed. The third theme involved relational aspects, which were mainly a positive influence, and included good leadership, good colleagues and a good work culture. Fourth was support and development opportunities, which were also mostly positive, with resourcing, funding and training the main aspects. The fifth theme was work security and this was overwhelmingly negative, with those in precarious roles being uncertain about their future. The sixth and seventh themes were match to skill set and match to career goals respectively. The match to skill set was perceived more positively, with most comments pertaining to how the skills developed were used in their work. In terms of match to career goals, the comments were evenly split between positive (if they were on track with their goals) and negative (if the position was not in alignment with their goals). Comments about location were mainly negative due to a long commute or not living in a location they found desirable.

Experiences of Work in Different Employment Sectors

In this section, we report on graduate experiences of their work and what contributed to their work happiness.

Tenured Academic Position

Five graduates in tenured or permanent faculty positions provided comments about their happiness, with more positive (8) than negative (3) responses (graduates could identify more than one factor). Three were ‘very happy’ with their position; the other two were ‘somewhat happy’. Of those being ‘very happy’, one commented: “There are very few jobs available in my field and I’m privileged to have one of them. This is exactly the job that I trained for and hoped to get once I finished my studies.” Another said “I can always contribute my knowledge in education to the society”, and two mentioned opportunities to further develop their skills and their career. For the two who were ‘somewhat happy’, one found the job rewarding, with a very collegial atmosphere and “very much enjoys both teaching and research”. However, both they and the other graduate raised workload issues and a lack of time, e.g., “too much work, too little time”. Although there was a sense of work fulfilment among these graduates, their happiness seemed to be tempered by the realities of the job, which they discovered could be very demanding.

Tenure-Track

Fourteen graduates on tenure-track provided comments about work happiness, with 32 positive comments versus 16 negative ones. Six were ‘very happy’, four were ‘somewhat happy’, two were ‘neutral’, one was ‘unhappy’, and one was ‘very unhappy’.

One ‘very happy’ graduate commented “I feel like I’ve won the academic lottery”, securing a tenure-track position in a competitive field, loving teaching, having great colleagues and in a desirable location. Among the others: three commented that their positions were part of their career goal to attain tenured positions; three enjoyed the role with the mix of teaching and research, and five discussed having good colleagues. Three commented about being in good locations. Of the four who were ‘somewhat happy’, they all said they enjoyed the job. The matter of workload and a lack of training to prepare them (e.g., project budget, managing people) arose for one, while another mentioned anxiety about the tenure process, and one disliked the location.

Of the two who were ‘neutral’ about their position, one liked the job but not the location, and the other was concerned about their teaching load and administrative load and institutionalised racism/inequality. Workload again proved to be a factor for one of the ‘somewhat unhappy’ graduates, who perceived that they were “working the equivalent of two full-time jobs and getting paid for one.” The other commented about conditions:

My salary is low (just over NZD50,000 with a PhD! ); over-work (7 papers/courses per year! ); a lack of leadership, micro-management of our CEO; not valuing research outputs….

There were conflicting feelings regarding work happiness for this group. Although they were advancing towards their career goal and enjoyed their work, the pathway to happiness (a tenured job) was somewhat marred by the realities of the job, especially workload and poor working conditions.

Academic Fixed-Term

Thirty-three of the graduates in academic fixed-term positions provided feedback on their happiness ratings. Six were ‘very happy’, 19 ‘somewhat happy’, three ‘neutral’ and five ‘somewhat unhappy’. More negative (49) than positive (35) comments were given, indicating lower levels of SWB. The main positive factors included interest and enjoyment of their work, as well as a supportive work environment through mentoring, networking and development opportunities. One commented “I’m growing a lot and feel this is preparing me for a future in academia. I love the culture and research environment.” Five comments were positive about relational aspects such as a collegial work environment, being included, and having good leadership, and some found the work environment offered good pay and good workloads.

However, 16 commented on the precarity of fixed-term positions, with one saying:

I am happy to be gainfully employed by a research university, but the temporary nature of my position has drawbacks. It would be nice to put down roots somewhere, and to feel like I am a stronger part of the university community.

Alongside wanting to feel settled and belonging to the university community, others were concerned about uncertainty and stress due to the temporary nature of their position. For example, one said “I work from contract to contract (project to project), depending on the external research funding I can attract. I love my job, but it is unsettling not to have a permanent position and to always be applying for my next grant.”

Nine discussed the poor conditions in terms of salary and/or workload, and for some a lack of benefits such as insurance. Some had become disillusioned with academia:

I am unhappy with academia. I think academics (both permanent staff and fixed-term research staff like myself) work far more hours than is reasonable. I am employed for 35 h a week on my contract, but I work 45 usually…This has a big impact on mental health, and there is little being done to address it…. I enjoy doing science, though.

Given the difficulties experienced in these precarious positions and an uncertain academic pathway, it is not surprising this group were less happy than some permanent or tenure-track academic colleagues.

Academic Professional

Three of the survey sample were in permanent academic professional positions: one was an Academic Skills Development Manager, one was a Research Coordinator, and one was an Advising Coordinator. They gave eight positive comments, and one negative comment. Two were ‘very happy’ with the role, with the Manager commenting it was interesting and challenging with good benefits. The Advising Coordinator said “I am able to continue working with undergraduates in a capacity that is similar to teaching, and uses skills that I gained during the Ph.D. I like the collaborative and warm culture of my unit and my co-workers.” The Research Coordinator was ‘somewhat happy’ and commented that a lot of administration was required in their role.

Government/Public Sector

Of the 14 graduates working in the government or public sector who gave comments, seven were ‘very happy’, five were ‘somewhat happy’, one was ‘neutral’ and one ‘somewhat unhappy’. Overall, their comments were mostly positive (28 cf. 12 negative). Many found the job interesting and/or enjoyable and there were four positive comments about the work environment. For example, one said “The department has a very humane work culture and it allows me an excellent work/life balance.” Four commented on gaining a sense of fulfilment and making an impact, with one saying “Putting political science research to work to make a difference in the real world”. Three noted the opportunities for growth, and two commented how they could apply the skills learned, with one saying “I feel that I get to apply my specialised skills and also learn more about more general skills that I can apply to most policy jobs in the government.”

The negative comments mainly related to precarity as three were in temporary jobs, and a perception that their PhD qualification did not really count in the job. Regarding the latter, one said, “I could have qualified for this job straight out of high school, so it is frustrating to be in this position.” One commented that they were “initially very unhappy to take a government position rather than an academic one, but I enjoy the work and the (much) lower degree of pressure.” This last comment illustrates that this employment sector, whilst not the one initially desired, could be surprisingly satisfying.

Private Sector for-Profit

Eighteen graduates employed in this sector provided comments on work happiness, with most positive (40 c.f.11 negative). Eleven were ‘very happy’, four ‘somewhat happy’, one ‘neutral’, one ‘somewhat unhappy’, and one ‘very unhappy’. The two main factors influencing feelings of happiness were fulfilment with work (19) and the work environment (10). Many comments noted the interesting and enjoyable work, as well as mentioning good salaries and benefits, flexible hours and workload. For example, one commented: “Autonomous, able to work closely with my spouse, able to make a difference for people and our natural world, feelings of contributing to something worthwhile”, while another said “I earn a lot of money and get great benefits, and people actually occasionally care about what I’m working on”. A new subtheme of a sense of stimulation and excitement was found, and others reported the positive aspect of being able to apply skills gained in their PhD, with one saying “I get to apply my scientific training in different and creative ways, translating (sometimes dry) scientific findings into educational and technical materials relevant to the healthcare and pharmaceutical industries.”

Of the 11 negative comments, two said their work was not their desired job, one said it was unrelated to the field of their PhD and others disliked aspects of the work culture and company ethos, workload and/or a lack of opportunities for advancement. The only graduate who was ‘very unhappy’ said “I hate my job. There is no opportunity for advancement, and the company is ruled by seniority, not capability and merit.” So, although not experienced by all as a satisfying option, it is apparent that working in the private sector for-profit, can be a stimulating, exciting and impactful option for many.

Private Sector not-for-Profit

In this sector, four graduates provided comments, with eight positive and three negative responses. One, who was ‘very happy” said “Outstanding direct manager. Clear applied aspects with high demand for services / skills. Collaborative development of IP. Freedom to conduct primary research. Great salary.” Two were ‘somewhat happy’, with one citing the ability to apply skills learned during their PhD, but the fourth was ‘somewhat unhappy’ due to a long commute and their job not requiring any social interaction.

Teaching

All three teachers in the sample provided feedback, with two positive comments and five negative ones, giving the lowest level of SWB. One graduate who was ‘somewhat happy’ loved the teaching but not the administration, and recognised the lack of progression opportunities unless they went into management. The graduate who was ‘neutral’ thought it was a “comfortable gig” but it was not part of their long term career goals, while the third graduate who was ‘somewhat unhappy’ was “constantly stressed about the number of teaching contact hours” and a lack of planning time. None of these graduates were very happy indicating that this pathway is possibly less preferred and likely to be less satisfying, but because of small numbers, further research is required.

Discussion

First, we synthesise our findings across the different employment sectors, and then consider factors influencing work happiness, followed by implications and then the strengths and limitations of this study.

Synthesis of Findings

Nearly 60% of the 120 graduates who provided employment information were working in academia in higher education, with most in precarious fixed-term positions—mainly postdoctoral fellows. Only 9.2% were in permanent or tenured faculty positions, with 13.3% in tenure-track positions. These figures confirm the long time it can take for graduates to secure tenured positions. The percentage working in higher education is higher than many other studies who report only 40–50% of graduates working in higher education (e.g., McCarthy & Wienk, 2019; OECD, 2021). It is possible our sample is biased to those who are employed in higher education, given the stigma of taking jobs outside academia (McKenzie, 2021). Such graduates may be more likely to respond to a survey.

Overall, the alumni in our sample were mostly ‘happy’ or ‘very happy’ with their work. We recognise that our data represent a snapshot in time, and that happiness is likely to vary due to the work situation. Our analysis showed no evidence of an association between work happiness and whether graduates were in academic or non-academic employment. This is contrary to some past research, which has reported less satisfaction of PhD graduates in work outside academia (e.g., Alfano et al., 2021; Paolo, 2016). Moreover, there was no evidence for differences in happiness between the two graduating cohorts or the university of study, nor for those from HASS or Science disciplines. However, those in permanent positions were happier with their work than those in temporary positions.

Factors Influencing Work Happiness

Our analysis generated eight main themes relating to work happiness: the need for work to be fulfilling; the work environment; relational aspects of the workplace; support and development opportunities; work security; match to skill set; match to career goals; and location. Recall that when positive experiences outweigh negative ones, subjective well-being and happiness should be higher (Diener, 2000).

Regarding work fulfilment, many graduates wanted work to be enjoyable and/or of interest, or something they were passionate about. For some working outside academia, the enjoyment was perhaps pleasantly surprising, as they had not anticipated being happy in a role different to their initial career expectations. This finding was noted by Ewing-Cooper and Gallien (2022), in reference to graduates working in academic administrative positions, but the literature on transitions of doctoral graduates into careers beyond academia is lacking exploration of this emotive aspect. Fisher (2010) found that those feeling engaged with their work through aspects such as enthusiasm, dedication, absorption and pride, are likely to be happier. Some graduates in either government or the private sector (for-profit) identified making an impact as positive – an aspect aligned with job engagement and satisfaction. It was interesting that this aspect came up in employment outside academia, perhaps revealing a perception that those in academia are making less of an impact. Such a conjecture would require further research.

Our definition of work environment included workload, salary, benefits and space. Like others (e.g., Cyranoski et al., 2011; Escardibul & Afcha, 2017), we found that graduates were happier when on permanent contracts with a good salary and benefits. Regarding workload, it was noticeable that most perceptions of high workloads came from those working in academia; many in positions outside academia commented on favourable workloads.

The themes of relational aspects of work and support and development opportunities were closely related. Having good work colleagues led to positive emotions and happiness in the workplace. Conversely, unhappiness arose where someone felt isolated and not part of a community (more common in academic fixed-term roles). The absence of a sense of belonging by academics in precarious positions was found by McAlpine and Turner (2012), and, given Fisher’s (2010) views about the importance of belonging to an organisation for workplace happiness, it is not surprising that those feeling isolated were less happy.

Regarding work security, our statistical analysis showed that graduates in temporary positions were less happy. Our qualitative analysis confirmed this finding, with those in precarious positions relating some very unhappy emotions. Precarity was more prevalent in academic fixed-term positions, which past researchers such as Holley (2017) and Acker and Haque (2017) have discussed, but was also experienced by a few employed in government jobs. Given that 52.5% of graduate respondents identified being employed in temporary roles, precarity is a factor of work unhappiness that many manage.

As expected from past research (e.g., Alfano et al., 2021; Escardibul & Afcha, 2017), we found that graduates were more positive when their job matched their expectations. This was particularly evident in those on tenure-track or in tenured positions, and noticeably absent from those in academic fixed-term positions. For those in government and the private sectors, many were positive about using skills learned during doctoral study, with some surprised this was the case. Conversely, a position that did not match their doctoral skills contributed to a sense of unhappiness. We suspect that because the training of PhD graduates is largely focused on preparation for an academic career (e.g., ACOLA, 2016), and the fact this career is seldom obtained, there is greater importance of the job-skills match as a key factor in work happiness for this particular cohort.

Lastly was the importance of location in relation to work happiness. When the location was perceived as desirable – often in relation to commute times and proximity to family and friends – graduates were happier. The aspect of location has been noted by others as an important aspect of job selection (e.g., McAlpine & Turner, 2012).

Implications

Our research has revealed key factors that PhD graduates might find important in realising work happiness, and has implications for both doctoral education and employers. It was noticeable that some graduates were surprised that they enjoyed work outside academia (similar to a finding by Ewing-Cooper & Galline, 2022), implying that there were unaware of how satisfying and enjoyable these pathways could be. Consequently, it is important that doctoral programmes include career preparation covering the range of possible careers, and the benefits and challenges of the various pathways. In some related research with this cohort (Spronken-Smith et al., 2024), we noted a tendency of some supervisors and departments to privilege academic pathways, suggesting academia was the only successful outcome for graduates. Such behaviour whether unintentional or overt, needs to change to support and celebrate all career pathways. Moreover, PhD candidates need to develop greater awareness of the transferrable nature of the skills and attributes fostered or enhanced through doctoral study. Requiring individual development plans and conversations with career advisers would better prepare PhD graduates to consider various pathways, and better position them for the job application process and potential precarity in the employment environment. Fostering networking skills and career agency as well as enabling networks with industry, is also important to help graduates transition beyond academia (Germain-Alamartine et al., 2021).

Given the well-trodden pathway of PhD graduates into academic fixed-term positions while in pursuit of securing tenure-track positions, it is imperative that higher education institutions provide better support for these graduates. These graduates are mostly in precarious roles, often on poor salaries, have few benefits and some report having no sense of belonging to the university community. For those in casual teaching roles, who Ryan et al. (2017) referred to as the ‘invisible faculty’ (p.61), they are largely ignored or neglected by management, despite significant reliance on them for their contributions to teaching. At the very least, institutions should be welcoming such employees into the university community, highly valuing them, encouraging peer support groups, and providing access to professional and career development support.

Strengths and Limitations of the Study

Strengths of our study included the broad base approach looking at graduates’ job experiences across different employment sectors, as well as gaining data from graduates in two different countries and from two different cohorts. With the universal nature of the PhD degree, it is unsurprising that graduates from the US and NZ report similar experiences of the jobs they enter – both the highs and lows. Moreover, our survey instrument captured both quantitative data for rating of work happiness, as well as qualitative data through freeform comments, which many offered. However, we did not initially set out to focus on work happiness – it was simply part of the US survey we adapted in the broader study. If we had purposefully set out to measure work happiness, we would have designed a different study, better informed by theory, with multiple measures, as well as capturing work happiness over time, given it can vary. A further limitation is that our sample was small, with only 118 providing both employment and happiness data.

Conclusion

Our research aimed to determine which employment sectors PhD graduates were working in, how happy they were in their job, and key factors influencing their work happiness. The majority of graduates (82.2%) were happy with their jobs, those in permanent positions were happier, and we found no evidence of a difference in work happiness between graduates within or outside academia. Graduates in tenured or tenure-track positions were generally very happy pursuing their career goal, and being passionate and interested in their work, but the work environment proved challenging for many. Those working in permanent academic professional roles enjoyed applying their doctoral skills, working with students or staff and having good benefits and workload. Graduates in the private sector (for-profit) seemed to be very stimulated and excited about their work, and those in government often found their work surprisingly satisfying. Graduates in academic fixed-term roles and teaching reported more negative than positive experiences.

Overall, the main factors influencing happiness were the need for work to be fulfilling (congruent with passions or interests), the need for a supportive work environment (including reasonable workloads, good salaries and benefits), positive relational aspects with good leadership and colleagues, strong support and development opportunities, work that was secure with a good match with skill sets and career expectations, and in a desirable location.

We cannot help but note that universities seem to be benevolent receivers of PhD graduates who feel grateful to get an academic position where they can pursue their dreams. But internationally, universities are casualising their workforce, meaning poor working conditions for many. Possibly through a lack of awareness of options, PhD graduates continue to seek precarious academic roles, hoping these will lead to permanent positions. This is despite the fact that many tenured academics report difficult working environments. Universities need major cultural shifts to promote healthier working conditions for all, especially those in precarious positions, seeing them as valued members of the work community entitled to a range of support mechanisms.

Doctoral programmes should be promoting a range of employment options for PhD candidates, and not privilege academic pathways. Doctoral candidates need to be aware of the pros and cons of various jobs, and how their skills and attributes can translate into many settings. Most importantly they need to know that they can be very happy in jobs outside academia!

Further research is needed to better capture the experiences of PhD graduates going into work outside academia. Using qualitative and longitudinal approaches, we could learn more about PhD graduates’ experiences of this transition and use findings to inform doctoral training and career advising, as well as informing employers regarding how they can best support graduates taking on such roles.

References

Acker, S., & Haque, E. (2017). Left out in the academic field: Doctoral graduates deal with a decade of disappearing jobs. Canadian Journal of Higher Education, 47(3), 101–119.

Alfano, V., Gaeta, G., & Pinto, M. (2021). Non-academic employment and matching satisfaction among PhD graduates with high intersectoral mobility potential. International Journal of Manpower, 42, 1202–1223.

Arthur, M. B., Hall, D. T., & Lawrence, B. S. (1989). The handbook of career theory. Cambridge University Press.

Australian Council of Learned Academies (ACOLA). (2016). Review of Australia’s research training system. ACOLA.

Berman, J. E., & Pitman, T. (2010). Occupying a ‘third space’: Research trained professional staff in Australian universities. Higher Education, 60, 157–169.

Cyranoski, D., Gulbert, N., Ledford, H., Nayar, A., & Yahia, M. (2011). The PhD factory: The world is producing more PhDs than ever before. Is it time to stop? Nature, 472, 7343.

Diener, E. (2000). Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. The American Psychologist, 55, 34–43.

Escardibul, J-O., & Afcha, S. (2017). Determinants of the job satisfaction of PhD holders: An analysis by gender, employment sector, and type of satisfaction in Spain. Higher Education, 74, 855–875.

Ewing-Cooper, A., & Gallien, K. N. (2022). Off the tenure-track: Experiences of PhD graduates in academic administrative positions. Perspectives: Policy and Practice in Higher Education, 26, 102–108.

Fisher, C. D. (2010). Happiness at work. International Journal of Management Reviews, 12, 384–412.

Germain-Alamartine, E., Ahoba-Sam, R., Moghadam-Saman, S., & Evers, G. (2021). Doctoral graduates’ transition to industry: Networks as a mechanism? Cases from Norway, Sweden and the UK. Studies in Higher Education, 46(12), 2680–2695.

Hancock, S. (2021). What is known about doctoral employment? Reflections from a UK study and directions for future research. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 43, 520–536.

Hauss, K., Kaulisch, M., & Tesch, J. (2015). Against all odds: Determinants of doctoral candidates’ intention to enter academia in Germany. International Journal for Researcher Development, 6(2), 122–143.

Hnatkova, E., Degtyarova, I., Kersschot, A., & Boman, J. (2022). Labour market perspectives for PhD graduates in Europe. European Journal of Education, 57, 395–409.

Holley, K. A. (2017). The longitudinal career experiences of interdisciplinary neuroscience PhD recipients. The Journal of Higher Education, 89, 106–127.

Hsieh, H-F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288.

Kesebir, P., & Diener, E. (2008). In pursuit of happiness: Empirical answers to philosophical questions. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3, 117–125.

McAlpine, L., & Turner, G. (2012). Imagined and emerging career patterns: Perceptions of doctoral students and research staff. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 36, 535–548.

McCarthy, P., & Wienk, M. (2019). Who are the top PhD employers? Melbourne: The University of Melbourne. Accessed June 23, 2024. https://amsi.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/advancing_australias_knowledge_economy.pdf

McKenzie, L. (2021). Un/making academia: Gendered precarities and personal lives in universities. Gender and Education, 34(3), 262–279.

Miller, J. M., & Feldman, M. P. (2015). Isolated in the lab: Examining dissatisfaction with postdoctoral appointments. The Journal of Higher Education, 86, 697–724.

OECD (2021). Reducing the precarity of academic research career. OECD Science, Technology and Industry Policy Papers, May 2021, No. 113.

Paolo, A. D. (2016). Endogenous) occupational choices and job satisfaction among recent Spanish PhD recipients. International Journal of Manpower, 37, 511–535.

Ryan, S., Connell, J., & Burgess, J. (2017). Casual academics: A new public management paradox. Labour & Industry: A Journal of the Social and Economic Relations of work, 27(1), 56–72.

Schäfer, G. (2022). Spatial mobility and the perception of career development for social sciences and humanities doctoral candidates. Studies in Continuing Education, 44(1), 119–134.

Spronken-Smith, R., Brown, K., Cameron, C., McAuliffe, M., Riley, T., & Weaver, K. (2023). COVID-19 impacts on early career trajectories and mobility of doctoral graduates in Aotearoa New Zealand. Higher Education Research and Development, 42(6), 1510–1526.

Spronken-Smith, R., Brown, K., & Cameron, C. (2024). Retrospective perceptions of support for career development amongst PhD graduates from US and New Zealand universities. Studies in Graduate and Postdoctoral Education, 15(3). https://doi.org/10.1108/SGPE-05-2023-0048

Sutherland, K. A. (2017). Constructions of success in academia: An early career perspective. Studies in Higher Education, 42(4), 743–759.

Van der Laan, L., Ormsby, G., Fergusson, L., & McIlveen, P. (2023). Is this work? Revisiting the definition of work in the 21st century. Journal of Work-Applied Management, 15(2), 252–272.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. Thanks are due to Fulbright New Zealand for funding the visit of the first author to the US and to the deans and managers of graduate research at the participating universities for assisting in ethics and data collection.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Spronken-Smith, R., Brown, K. & Cameron, C. Work Happiness of PhD Graduates Across Different Employment Sectors. NZ J Educ Stud (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40841-024-00339-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40841-024-00339-1