Abstract

Student bullying behaviours are a significant social issue in schools worldwide. Whilst school staff have access to quality bullying prevention interventions, schools can face significant challenges implementing the whole-school approach required to address the complexity of these behaviours. This study aimed to understand how schools’ capacity to implement whole-school bullying prevention interventions could be strengthened to promote sustainability and improve student outcomes. Qualitative methods were used to observe schools over time to gain insight into their implementation capacity to improve student social and emotional wellbeing and prevent and ameliorate harm from bullying. A four-year longitudinal, multi-site case study intensively followed eight schools’ implementation of Friendly Schools, an Australian evidenced-based whole-school bullying prevention intervention. Regular in-depth interviews with school leaders and implementation teams over four years led to the refinement of a staged-implementation process and capacity building tools and revealed four common drivers of implementation quality: (1) strong, committed leadership; (2) organisational structures, processes and resources; (3) staff competencies and commitment; and (4) translating evidence into local school policy and practice. This paper considers the strengths of qualitative data in understanding how and why bullying prevention interventions work as well as actions schools can take to enhance their implementation and sustainability of complex social interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Student bullying behaviours are increasingly recognised as a covert and complex social problem in schools worldwide (Barnes et al., 2012; Modecki et al., 2014). Involvement in bullying is a significant risk factor affecting young people’s social and emotional wellbeing and mental health (Cross, 2015a; Lester et al., 2013; Moore et al., 2017) and is associated with both immediate and life-long harms (Holt et al., 2015; Farrington & Ttofi, 2011; Ttofi et al., 2016). Despite many evidence-based bullying prevention interventions developed to help reduce these harms, students in need are not being reached due to barriers relating to adoption and inconsistent implementation by schools (Bradshaw, 2015; Hagermoser Sanetti & Collier-Meek, 2019). A critical ‘implementation gap’ exists between what we know works from intervention studies and what is practised in schools to support the learning, mental health and wellbeing of students. Qualitative research methods offer the opportunity to help close this gap, providing an in-depth understanding of the specific implementation challenges faced by schools and what effective, context-driven strategies are required to address them (Liamputtong, 2013).

This ‘implementation gap’ is partly due to the complexity of whole-school approaches aiming to facilitate social and organisational change at multiple levels of a school community. Whole-school interventions typically target all members of the school (students, staff, families, and the wider community) and use multiple components of policy and practice to foster a positive and protective social and physical school environment, teach explicit social and emotional skills and engage parents, as well as targeted intervention and support for students with higher needs. Evidence suggests a whole-school approach is the most effective and non-stigmatizing means to reduce harm from victimization and prevent and manage complex social behaviours like bullying (Gaffney et al., 2021; Langford et al., 2015; Pearce et al., 2011). This approach is supported by socio-ecological theory (Cross et al., 2015b; Espelage, 2014) and reviews of efficacy and effectiveness trials demonstrating positive changes to student outcomes from the implementation of school-wide approaches (Jiménez-Barbero et al., 2016), compared with the implementation of a curriculum or policy alone (Smith et al., 2004). However, the overall effects sizes are modest and somewhat mixed (Evans et al., 2014; Ttofi & Farrington, 2011; Vreeman & Carroll, 2007). Although these smaller than expected effects can be partly explained by methodological issues and increased anti-bullying policy mandates by many countries, intervention studies frequently report effects were limited by insufficient school capacity to adopt and effectively implement these complex whole-school interventions (Ttofi & Farrington, 2011), particularly in effectiveness (real-world) trials (Rapee et al., 2020; Axford et al., 2020).

How well an intervention or practice is applied in real-world school settings is the key concern of implementation science (Lyon, 2017). There is strong empirical support that implementation is a key determinant in improving student outcomes (Dix et al., 2012; Durlak & Dupre, 2008; Smith et al., 2004). For instance, Ttofi and Farrington (2011) found that program duration and intensity (dose) for students and teachers are two of the main factors associated with a significant decrease in rates of bullying others and being bullied. However, they note that most programs fail to provide robust implementation data, making it difficult to assess the moderating effect of this on outcomes (Ttofi & Farrington, 2011). Whilst greater effort is being made to collect program implementation related data, challenges are inherent in standardising measures for comparison when interventions are complex and varied with limited consensus around key constructs within this relatively new field (Martinez et al., 2014).

One construct central to the issue of implementation quality is the degree to which an intervention’s strategies are delivered as intended versus the extent to which adaptions are made to suit the local setting (Gearing et al., 2011; Stains & Vickrey, 2017). Interventions transferred to real-world settings with sufficient fidelity (i.e. as originally used in efficacy studies) are more likely to demonstrate enhanced program success and better outcomes for participants (Durlak & Dupre, 2008). This process is challenging for busy schools with different needs and multiple competing priorities, and time pressures and local adaptations, therefore, seem inevitable. Indeed, such adaptions may be beneficial if they enhance school ownership and commitment to a program and support the ‘goodness-of-fit’ between an intervention and the school in which it is being delivered (Lendrum & Humphrey, 2012; Lendrum et al., 2016). Of course, such adaptations may affect outcomes if the implemented intervention diverges too far from the original intervention (Johander et al., 2021), but rather than ignoring this process, it is essential to monitor these adaptations to interventions and to not mask the complexities in which interventions are put into practice (Greenberg, 2004).

Qualitative studies have helped to ‘unmask’ these complexities and identify factors that appear to enable or inhibit the effective implementation of school-based bullying prevention interventions through a deeper look at the influencing contextual factors and processes (Pennell et al., 2020; Coyle, 2008; O’Donoghue & Guerin, 2017; Young et al., 2017; Locke et al., 2019). Guiding frameworks such as the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (Damschroder et al., 2009) and the Framework for Implementation Quality in School-based Interventions (Domitrovich et al., 2008) have also helped to define potential barriers to quality implementation at individual, organisational and wider-system levels. School leadership engagement, staff commitment and professional characteristics, alignment with school vision and policies and school climate, resourcing and school readiness have been shown to be important factors in influencing implementation quality (Domitrovich et al., 2019; Wanless & Domitrovich, 2015). Despite an abundance of research identifying barriers to successful implementation of school bullying prevention interventions, research into the most effective implementation support strategies to match individual school contextual barriers is still in the early stages (Waltz et al., 2019).

A recent taxonomy of implementation support strategies has been compiled in healthcare (Leeman et al., 2017) and adapted for school-based interventions (Cook et al., 2019). Implementation strategies used in school-based interventions, however, are typically limited to intervention materials and training, with little embedded capacity building for long-term, whole-school change (Roberts-Gray et al., 2007). Effective capacity building goes beyond skills training of individuals to include assessment of leadership, structures and processes, workforce development and resources as well as partnerships within school systems to support teachers, parents and students to implement sustainable strategies over the longer term (Hawe et al., 1997). Capacity-building models highlight the need to focus on general organisational capacity such as structures, roles and systems to increase the capacity of staff and, in turn, their effective use of the specific skills and tools required to implement a new policy, program or practice (Potter & Brough, 2004).

The required capacity building strategies can differ depending on the individuals, organisations and the wider systems in which they operate, as well as the stage of implementation (Aluttis et al., 2014; Wandersman, 2008). The implementation process is said to occur in four main stages: (1) exploration; (2) preparation; (3) implementation; and (4) sustainment (Aarons et al., 2011). Evidence shows that efforts in the pre-implementation stages predict successful intervention start-up and sustained delivery (Saldana et al., 2012). Moreover, the stage of implementation will determine what capacity building strategies are required, with resources varying depending on the nature of the specific barriers and enablers present (Saldana et al., 2014). Assessment tools have been developed to help identify the school-capacity factors most likely to drive successful intervention implementation (Gingiss et al., 2006). However, tools to assist school staff to select tailored capacity building strategies based on these assessments and that meet their specific contextual factors are limited. There is a clear need for the development of practice-based tools and capacity building strategies to assist schools to identify and address their unique drivers and barriers to improve intervention and implementation outcomes.

The Friendly Schools Whole-School Bullying Prevention Intervention

Friendly Schools is an Australian whole-school social and emotional wellbeing, bullying and cyberbullying prevention intervention which has been found to be effective in numerous randomised control trials (Cross et al., 2011, 2012,2016, 2018, 2019). Friendly Schools comprises six core whole-school components addressing schools’: (1) leadership and capacity; (2) policy and procedures; (3) culture; (4) social and physical environment; (5) competencies though student curriculum, staff professional learning and parent communication; and (6) partnerships with families, services, and communities. It includes a developmental social and emotional learning curriculum (ages 4–14 years), cybersafety education for students, teacher training and family activities that aim to improve parental awareness and self-efficacy to help support their children’s social and emotional wellbeing and behaviour online and offline. The intervention also incorporates individual activities that provide targeted support for victimized students and for students who bully others, to help modify behaviour and facilitate links with allied health professionals. Although Friendly Schools had consistently been tested with varying levels of implementation support including school-team trainings and leadership engagement, barriers to whole-school quality implementation were still reported by schools (Cross & Barnes, 2014). Qualitative data from school leaders suggested that a systematic approach with strategies and tools to address identified barriers was required to strengthen the existing implementation support provided in Friendly Schools and enhance the impact on staff and student outcomes (Barnes et al., 2019). This understanding led to the conceptualisation of a longitudinal multi-site investigation on ways to build schools’ capacity to effectively implement Friendly Schools.

Current Study

The Friendly Schools: Strong Schools Safe Kids study aimed to develop and pilot a coherent implementation process and capacity-building tools to strengthen schools’ capacity to effectively implement a whole-school approach to help enhance students’ social and emotional wellbeing and reduce bullying behaviours. This study was part of a five-year project (2010–2015) that involved consultation with education-system stakeholders and school-leadership staff to map the current Australian context in which whole-school bullying prevention interventions operate. Informed by these stakeholder findings and a review of implementation science research, implementation process and capacity supports were developed to be refined and piloted in eight heterogeneous case-study schools. This multi-site case-study design aimed to provide an in-depth understanding of the real-world context and processes that different schools use to plan, prepare and implement whole-school interventions.

The implementation process featured a seven-stage quality improvement cycle and capacity building training and tools to improve implementation quality. The seven-stage cycle comprised the following virtuous cycle of actions: (1) Surveying students, staff and parents; (2) assessing whole-school practice; (3) planning priorities using data; (4) building staff capacity; (5) using whole-school toolkits to respond to priorities; (6) implementing student learning activities; and (7) reviewing changes in practices, processes and student outcomes. The capacity-building training and tools included a one-day school team training (first year of intervention only), two school-team coaching visits per intervention year (approx. 2 hours duration), student and staff online surveys and a ‘map-the-gap’ school policy and practice assessment. A range of toolkits were also provided that supported the school team to plan, monitor and deliver activities to help build staff readiness, commitment and competencies to implement evidence-based practice. This study aimed to understand how schools’ capacity to implement whole-school interventions, such as Friendly Schools, could be strengthened to promote implementation sustainability and improve student outcomes. Specifically, this paper describes schools’ multi-faceted contextual experiences related to their capacity to undertake the staged implementation process and identifies key drivers of implementation quality.

Methods

Whilst quantitative approaches seek to ensure precise and robust identification and measurement of variables through randomisation, imposing strict controls, these methods used in isolation can lack important contextual information which can provide a richer understanding of the data (Guba & Lincoln, 1994). Hence, this in-depth study aimed to explore the nuances and complexities of school-based implementation processes using qualitative inquiry. It also sought to illuminate each school’s unique situational context and associated implications for capacity-building to address social and emotional wellbeing and bullying behaviours.

Research Design

A qualitative longitudinal multi-site case study design was adopted involving eight case study schools in Western Australia, from 2011 to 2014. Case-study approaches are used to investigate phenomena within real-life contexts using multiple sources of evidence (Baxter & Jack, 2008) and have been used elsewhere to evaluate school-based interventions which are complex and school specific (Burns et al., 2019; Vilaça, 2017; Ollis & Harrison, 2016). The multi-site case study design considered variation in school type (secondary vs K-12), sector, location and socio-economic status, whilst allowing for exploration of implementation similarities and differences (Yin, 2014). Mixed methods data collection included online student and staff surveys; interviews with school principals, staff implementation teams, teachers and parents; student focus groups; and school observations to explore the school’s context for implementation of Friendly Schools. This paper describes qualitative data collected through in-depth individual and group interviews with school principals and implementation team staff. In-depth interviews were chosen to understand and explore the school staff’s subjective experiences of their implementation journey. The use of one-on-one interviews allows participants to personally reflect and for rich, detailed and accurate information to be gathered (Liamputtong, 2013). Ethics approval for this project was provided by the Edith Cowan University Human Research Ethics Committee, and approval to conduct this research in schools was provided by the associated education sectors.

Case Study School Recruitment

A list of potential study schools was generated by the research investigators and education system stakeholders who formed the project advisory group. Schools were placed into a ‘context matrix’ to ensure representation from different school education systems (government, catholic, independent), socio-economic status (high, medium, and low), location (metropolitan or rural, within 300 km from Perth, Western Australia), type (kindergarten to grade 12 or secondary only) and size (small or large). Existing Friendly Schools research schools were excluded due to their previous experience in implementing Friendly Schools. The Australian school system comprises three different education sectors: (1) government; (2) catholic; and (3) independent. The first sector is the largest and is free for families to attend, the second sector is based on the philosophies of the catholic religion and the third sector operates independently, although it can share some administration resourcing with the other two sectors. Families self-select and pay fees to attend schools in both the catholic and independent education sectors. Eight schools were purposefully recruited and provided consent to participate in this study across these three education sectors.

Data Collection

Schools nominated a study coordinator and formed a team of staff to lead the implementation of Friendly Schools. Semi-structured (typically lasting one-hour) interviews were conducted by the research team twice a year with school principals and implementation team staff members. Interviews were conducted in person (with full implementation team of 3–12 staff members depending on school size) or via telephone (team coordinator only) in the middle and at the end of the school year. Hence, two interviews per school were conducted during each year of the four-year study to support and monitor the progress of priority actions and enable school teams to provide feedback in the design of the implementation process and tools. Interviews were audio-recorded with participant permission and evidence of school activities implemented (e.g. policies, reporting forms) were also collected in-person by the research team. At each data collection point, interview questions asked about the following: (a) the school’s experiences in implementing the core Friendly Schools intervention components including barriers and enablers; (b) the school’s experiences in using the staged implementation process and tools; and (c) recommendations for improvement and additional strategies/resources needed. Although this study explored the implementation of Friendly Schools as an overall framework for action, it also captured other practices or programs schools’ implemented to address student social and emotional wellbeing and reduce bullying behaviours.

Data Synthesis

Interviews were transcribed verbatim, and each school’s implementation journey was documented into a school case study to track school progress and feedback over time. To maintain dependability and determine credibility (Liamputtong, 2013), transcripts were summarised and participant-checked by all available members of the school’s implementation team to ensure they were a valid reflection of their school’s journey and their implementation barriers and facilitators. Each individual school’s data were used to conduct a cross-case study using Framework Analysis (Ritchie & Spencer, 2002) to identify common and different experiences by schools and the outcomes they achieved. To enhance confirmability, two members of the research team analysed the data by jointly constructing the thematic framework and separately indexing the data to identify themes. Comparison between the two researcher’s indexed themes was conducted, and the framework was refined through consensus between the researchers. Charting and mapping of the data were then completed as per the methods described below. A summary of the school recruitment, data sources and analysis is summarised in Fig. 1.

Framework Analysis

Framework Analysis is a qualitative analytic approach used in applied policy and practice research and evaluation and uses a comparative form of thematic analysis (Ritchie & Spencer, 2002; Goldsmith, 2021). Framework Analysis involves five stages: (1) familiarisation of the data through listing initial themes to provide an overview of the depth and diversity of information; (2) constructing a thematic framework of key concepts emanating from the data and also drawing on a-priori issues; (3) indexing, through systematically applying the thematic framework to the data which is sifted and sorted into the identified themes; (4) charting and rearranging the data according to themes, after ‘lifting’ it from its original context in the individual transcripts; and (5) mapping and interpretation of the data set as a whole to answer the research objectives guiding the qualitative analysis.

The Framework Analysis was facilitated using NVivo (NVivo Qualitative Data Analysis Software; Version 10, 2012). Data collected from case study schools were summarised by case (school) and theme using NVivo in-built framework matrices. These matrices provided an opportunity to see associations between different themes, both within and across cases, and automatically gathered all the information relevant to each particular theme as it was coded (i.e. combining the indexing and charting stages of analysis). The NVivo framework matrices also enable comparison of the viewpoints of different individuals, such as school principals versus implementation team staff perceptions. Essentially, the use of NVivo as a ‘looking glass’ can make transparent the process of indexing, charting and mapping the data into a meaningful form that progresses new understandings in a more timely manner for researchers. (Beekhuyzen et al., 2010).

Results

The characteristics for each of the recruited case study schools is summarised in Table 1. Seven of the eight case study schools undertook the full implementation process and provided sufficient data to evaluate the barriers and enablers to quality implementation and feedback recommendations for improvement. One large metropolitan government-sector school withdrew from the research project in the first year after they were unable to collect sufficient baseline data from students due to difficulties in gaining opt-in parental consent as required by the education sector (case study school 6). This resulted in a total of 56 interviews (two interviews per year for each of the seven case study schools) being conducted over the four study years.

All case-study school staff during baseline interviews described having strategies in place to support student social and emotional wellbeing and reduce bullying behaviours. However, school team members noted these strategies were often uncoordinated, reactive, and ‘fragmented’ (school coordinator, school 3). School team members discussed being overwhelmed about deciding ‘which approach to take’ given the multitude of frameworks and programs available to them (school team member, school 4). They saw benefit in a staged implementation process to help identify their school’s needs, map their current activity against the evidence and improve their capacity to make informed decisions about which new practices to adopt.

Over the four-year study period, all schools made changes to their physical environment and policies and procedures, particularly in relation to cyber safety and bullying behaviours, through delivery of the Friendly Schools core intervention components. They also increased their focus on the systematic delivery of student wellbeing support and the nature of student support structures and services. Common challenges included engaging with parents and the wider community and building staff capacity to effectively implement school-level changes. The cross-case study analysis of the schools’ implementation of these Friendly Schools components revealed four key drivers of quality implementation, as well as perceived impacts on school implementation capacity, including the following: (1) strong, committed leadership; (2) organisational structures, processes and resources; (3) staff competencies and commitment; and (4) translating evidence to the local school context (see summary in Table 2).

Strong, Committed Leadership

In the initial stages of the implementation process, schools were asked to nominate a coordinator and form a team of staff responsible for leading the implementation process. Four schools used their existing student support team structure or leadership/administration team; three schools set up new teams. School implementation teams ranged from 3 to 12 staff members, depending on the school’s size. In schools where the team was embedded as part of the schools’ administration or leadership structure (e.g. head of each grade formed the team, school principal was part of the team), there appeared to be greater capacity to make decisions and consistently implement their chosen priority actions. Schools in which implementation team members responsible for student wellbeing also held a leadership/administration role reported being in a better position to address implementation barriers such as staff turnover. These dual roles were highly valued in these schools with many staff applying when a vacancy arose. For the schools where the team members were not part of the school leadership/administration roles, their efforts appeared to lose momentum, relying heavily on the team coordinator to progress outcomes. Even when using an existing team structure, it was important for school teams to have a clear common goal to work towards and mechanisms for staff input and support, as one school team coordinator stated:

Having a really strong team … staff that work cohesively has been the key to [driving the change process]. We're always in a common goal, and common mindset as well … I think we're all very much on the same pathway [which] has been the real strength in it. (School coordinator, school 3)

The explicit commitment and support of the school principal was considered essential for success and needed to be evident in the provision of resourcing and allocating time to staff to make the planned changes to practice. Schools without this explicit and concrete support from the principal were observed to struggle and often stalled in implementation until it was clear to staff that school leadership was committed. The implementation process and tools were seen to create an opportunity for schools to reflect on current practice as stated by one school principal:

Any program that gives us this opportunity to look at what we are doing and to question our practices … we need to take it on board. (School principal, school 3)

Having a coordinator or ‘staff champion/s’ who drive planning and action as well as skilled staff to support implementation across the school was also considered essential by the school teams:

The important thing is someone to drive it ... [and] now we have our pastoral care team to provide the driver … We are experiencing a considerable change. (School team member, school 2)

The power of greater student responsibility and engagement through existing and new student leadership roles was noted by school teams as crucial to successful implementation. The implementation of cyber safety and cyberbullying prevention strategies needed the active involvement of students to lend credence, as staff and parents were not seen to be sufficiently skilled in this area. Strategies selected and led by student wellbeing teams such as parent presentations often resulted in higher parent engagement. This was illustrated in the following comment by a school coordinator:

We set up a student committee … and gave them … some power and knowledge and information and asked them what they want out of this … how could this be changed or make something come alive for students. (School coordinator, school 7)

Organisational Structures, Processes and Resources

The educational system in which the schools belonged influenced how organisational structures and processes were used. Case study schools within one education system reported the mandatory use of monitoring and review tools that asked for evidence of the school’s student support, wellbeing actions and their effectiveness. This emphasised the wider policy context and validation of the important link between student learning and social-emotional wellbeing, thereby creating accountability that flowed into the school’s strategic plans. Schools independent of the larger education systems reported greater flexibility to select staff who aligned with their strategic vision and greater access to resource support than schools from other education sectors:

Most people here, have been handpicked ... which is an obvious strength, … that empathy and that student care understanding is really high ... on the agenda. (School coordinator, school 3)

Having separate staff involved in student discipline and student support was seen as beneficial as staff indicated it was difficult to cultivate approachability with students if they were also responsible for enforcing consequences for misbehaviour. A designated physical location for a student care ‘hub’ to not stigmatize students seeking help was also reported to increase the school’s capacity to implement effective student care services:

We’ve actually changed the physical look of what student services is … it used to be ad hoc and no building you would call ‘student services’. It has a dedicated administrative assistance, career counsellor, school psychologists, the sick bay, head of year groups have meeting spaces. It’s certainly become a hub for students to come to ... [and it’s] good to see the school has prioritised student care. (School coordinator, school 7)

Having the student support team located in one location also benefitted school strategies that aimed to support students when transitioning, for example from early to mid-secondary school grades. Co-location of the schools’ health services such as the school nurse to the hub was also found to add support and reduce stigma of seeking help for bullying or other mental health concerns as students could be at the hub for any number of reasons.

Regular student support team meetings to facilitate cohesive coordination were found to be helpful to ensure everyone was up-to-date with issues related to implementation, particularly if there were students in need of extra support, and to allow the school to proactively plan to address potential problematic situations. Increased resourcing to student care positions and social and emotional learning activities were observed in most of the case study schools as one school coordinator mentioned:

We’ve certainly increased the staffing and funding for the school counsellors … now we have two full-time counsellors. The school administration has seen the value … and certainly the workload has increased through our pastoral care system and being able to support student wellbeing by having them more available. (School coordinator, school 7)

More importantly, it was critical for these staff to have dedicated time to plan and implement priority strategies in their school, as well as common planning time between team members. In one school, it was a matter of ‘making sure that if we say something’s a priority, we give the supporting time’ (school coordinator, school 8). In several schools, this was illustrated through greater time allocation for senior and leadership positions to support student pastoral care matters.

Positive changes in the schools’ culture due to vertical age-group activities or student support systems (with multiple age groups together) were highlighted by most of the case study schools as creating an environment that encouraged positive interactions between students of different age groups and increased belonging to their school. As illustrated by the following comment of one school coordinator:

Originally being a horizontal school where … heads of grades look after their own age group, you’re not in a vertical system. That vertical culture is starting to really permeate through the school … I have certainly noticed a big shift in culture. (School coordinator, school 7)

Staff Competencies and Commitment

A school-based intervention is unlikely to succeed if the educators themselves do not see a need for it or do not believe it can be effective. Encouraging staff ‘buy-in’ and responsibility for pastoral care and responding to bullying was reported as challenging by all case study schools. For instance, as one school coordinator stated:

[A] major challenge is to get our staff on board to believe that it is their problem as much as it is everyone else’s and they have an obligation to intervene and not just handball anything that's ... an issue. (School coordinator, school 2)

Training and coaching sessions for school teams were seen as an invaluable way to build leadership competencies and build whole-school staff capacity to support priority actions. In particular, staff reported that restorative methods to respond to bullying incidents were necessary but required specific skills to implement and therefore sufficient training and coaching time to learn. One school coordinator reflected on the potential of professional development to build momentum among staff:

The training empowered us to take our capacity for action at a staff level to another level, and we are very excited about trying to take skills and share them amongst the community. (School coordinator, school 4)

Regular communication with all staff across the school was seen to be important in engaging all staff and empowering them to participate in decision-making processes to embed cultural shifts that demanded changing the way they practice. This was discussed by one school principal who stated the value of priority actions being ‘part of our school culture change’ rather than being the sole responsibility of a core group of staff. Essentially:

We are trying to empower all staff to get on board with things. So, we are actively now putting more things out that we are dealing with this as a whole staff. (School principal, school 5)

Engagement of outside agencies to help staff support at-risk or higher-need students in particular was seen as an effective way to reduce pressure and time burden for staff like the school nurse and psychologist with one school coordinator noting ‘it’s just another person that ... the kids can connect with and talk with and … seek help from’ (School coordinator, school 3).

Translating Evidence into Local School Policy and Practice

Several schools raised the importance of the local school context in terms of skills required to review the evidence and determine ‘how will that work in my school?’ (School team member, school 4). There is limited training for school staff to understand the best ways to respond to their students’ social-emotional needs; consequently, it is common to seek outside expertise to inform their decisions. However, this leaves schools unsure of how it can be implemented to suit their own context. As one school principal expressed:

There’s always suspicion of the theoretical … because I think context is so important. So, evidence in context is rare. Some things are sort of true and work generally but how will it work here in this situation, in this school? (School principal, school 1)

In the initial interviews with school implementation teams, it was apparent that schools had different experiences in facilitating whole-school change. Some schools had tried to implement very intense curriculum-based social-emotional programs that left staff feeling burned out. Unsustained programmes not only wasted valuable school resources but also squandered staff willingness to take on future programs. For instance, one school coordinator discussed a program that was implemented previously in the school only to discover later it was too onerous and a poor fit with existing objectives and curriculum:

We required a more flexible program that is appropriate across different ages and academic levels. (School coordinator, school 5)

Finding the balance between prevention approaches and responding to bullying incidents was challenging for all case study schools. Schools indicated some parents expected punishment for bullying behaviours and were impatient with restorative processes. School staff felt the student support hubs were helpful in providing multiple levels of care from promotion of good social-emotional wellbeing to targeted support for at-risk and higher-needs students. As one school leader pondered, there was an ongoing struggle to ‘defend the line’ and find a balance between resolving problems in a restorative way, rather than resorting to disciplinary sanctions:

Our pastoral care office is not a withdrawal centre, it’s a place for kids to go for pastoral care and relationship breakdowns are issues to deal with, they’re not things to punish. (School coordinator, school 1)

Case study school teams acknowledged the significant length of time it takes to truly undertake a whole-school approach to social and emotional issues and embed it into the central fabric of the school. They emphasised that it was not easy, took a long time and required a proactive preventative approach. If they were continually only dealing with issues once they had happened, then they felt they ‘had lost’ and were not helping kids really achieve.

We don’t have the answers for other schools … it’s all about context … it’s not easy … it takes a long time. It’s got to be central and integral … whichever system you use make sure it’s not peripheral, it’s central to what you do. (School coordinator, school 1)

A sustainable prevention-focused program was considered by school teams to be achievable through truly embedded student support programs and practices built into the school’s strategic vision and plans. Programs that were ‘added-on’ were not seen to effectively change the implementation climate to underpin success as recommended by a school coordinator:

You really need to make these things part of your pastoral fabric in the school. (School coordinator, school 2)

Data-driven decision-making tools like student surveys and school policy and practice assessments were ‘really powerful’ in building school staff commitment and capacity and were seen as ‘key agents to change’ (school coordinator, school 4). Individual findings in each case study school were helpful to identify priorities and needs, demonstrate to the whole-school community the need for action, justify leadership roles and responsibilities and provide a strong and relevant call to action. Understanding the needs of their own school community provided staff with in-depth knowledge of students’ strengths and needs and the opportunity to deliver more tailored solutions to meet those needs. The value of this was highlighted by one school coordinator who spoke about how ‘it validates the fact that we need to do something about it’ (school coordinator, school 8). Likewise, another school team member heralded the importance of these on-the-ground insights for driving change:

It clearly raised the profile of bullying and gave impetus to action. Moreover, it helped to show a way forward and added resolve to do so … we were able to look at what the school community was telling us were the issues. (Implementation team member, school 4)

Perceived Impact of the Implementation Process and Capacity Building Tools

After completing the staged implementation process, school teams reported an increased self-efficacy and capacity to facilitate whole-school change, suggesting value in a systematic and incremental approach to school and staff capacity building. As one school principal discussed:

I think there is probably greater self-confidence in our capacity to make change … I think there is an increased perception that we can actually challenge behaviours and stereotypes. (School principal, school 1)

School staff also reported on the positive effect of the staged support process in helping create social change in the school environment. Schools acknowledged that ‘you don’t change attitudes overnight’ and that to address social issues like bullying required working in incremental steps as one school coordinator stated that having a systematic process and tools provided:

A better understanding of what is happening ... by putting it on the table it becomes more real. (School coordinator, school 2)

Importantly, there was acknowledgement of the importance of ‘being reflective as practitioners’ when following a strategic implementation process that focused on both improved implementation quality as well as ‘improve outcomes for students’ (school coordinator, school 7).

It’s definitely been a good move and definitely meant that students have been benefitting and that’s what we are all about. (School principal, school 5)

School staff reported their increased capacity strengthened the support and education provided to all age groups, enabled greater collaboration between staff and improved practices such as engaging with students, parents and external agencies. Importantly, the systematic process was key to securing staff commitment from ‘not only leadership staff but also the whole-school staff’ which, as one school coordinator noted:

It’s a bit of an affirmation of what we are doing is the right thing. (School coordinator, school 7)

Discussion

This paper presents the qualitative findings from a four-year longitudinal multi-site case study that intensively followed seven schools’ systematic implementation of the whole-school social and emotional wellbeing and bullying prevention intervention Friendly Schools (Barnes et al., 2019). Qualitative methods were used to naturalistically observe these schools to deeply understand their staff’s implementation capacity to improve students’ social-and-emotional wellbeing and ameliorate harm from bullying. Data collected as part of regular in-depth interviews with school principals and implementation team staff members over four years led to the refinement of a staged-implementation process and capacity building tools and revealed four common drivers of implementation quality: (1) strong, committed leadership; (2) organisational structures, processes and resources; (3) staff competencies and commitment; and (4) translating evidence into local school policies and practice.

Quality leadership to drive implementation was seen as critical in all case study schools. Having at least one staff champion who was experienced and passionate about student care and wellbeing, with dedicated time to lead, was essential. Additionally, a collaborative leadership team of trained staff, who also had some time release from teaching duties to provide extra support to students and attend regular team meetings, was needed. Whilst an actively engaged and committed school principal was important, most schools engaged in distributed leadership roles and responsibilities.

The critical role of strong leadership commitment in the form of individuals and teams has also been found in bullying prevention related studies (Flygare et al., 2013) and school-based interventions more broadly (Iachini et al., 2013; Locke et al., 2019). Research indicates the foundational role of leadership in mediating the use of implementation strategies and improving implementation outcomes (Choi et al., 2019). In their study of leadership and the implementation of the intervention Multi-Tiered System of Support (MTSS), Choi and colleagues (2019) defined strong quality leadership as having (1) a clear vision for student outcomes, (2) an interdisciplinary team, (3) a consistent meeting structure, (4) reciprocal communication systems and (5) data-based decisions. These qualities support the case study school staff’s experiences in this study with leadership, particularly the need for school data to inform decisions.

Case study school staff highlighted the opportunities for student leadership in social and emotional wellbeing initiatives and identified this as an area to strengthen. Genuine ‘student voice’ and leadership in school’s cyber safety education efforts has been found to be particularly important to address cyberbullying behaviours where teachers and parents are viewed as less credible sources of help for students (Cross et al., 2015c). Students’ active participation in bullying prevention activities was also found by Flygare and colleagues (2013) to be an effective component in bullying prevention interventions, reducing individual student victimization by 40%.

Overall, improved student social-and-emotional wellbeing outcomes in case study schools were observed to have a range of organisational features. The most impactful feature noted by case study school staff was student support structures that formed part of the school administration. This minimised the impact of leadership and staff changes and facilitated action as this team had decision-making power. Flexibility with decisions to select appropriate staff and allocate roles and time to various responsibilities was observed to facilitate implementation more rapidly.

Vertical student pastoral care systems (e.g. multi-age group meetings during the day) or other co-curricular activities that mixed peers across age groups were also highlighted as effective in facilitating positive relationships between students. Likewise, student support staff, who had close contact with the same group of students as they progressed through school, established positive relationships between staff and students. The physical design and location of the student support services into a designated student support ‘hub’ enabled student access to a range of supports and meetings with staff and was considered helpful to destigmatise students seeking help. Dedicated regular meetings times in the ‘hub’ allowed staff to share common learnings and discuss support options for individual students. The common hub — with shared physical health and social-emotional wellbeing staff — may help reduce the stigma of help-seeking by giving students something less embarrassing to tell their peers they are there for, like a headache.

Although reviews of the effectiveness of bullying prevention interventions have not directly identified school organisational structures and processes as a key component, strategies that support schools to develop policies and reporting procedures in response to managing bullying do so indirectly. Whole-school policies were associated with positive reductions in bullying outcomes (Gaffney et al., 2021; Ttofi & Farrington, 2011) and provided a vehicle for schools to define their approach to bullying and set clear behavioural expectations and processes for managing incidents including the involvement of parents and external support agencies. Evidence of ways that school staff structure their student support services and its effects on bullying prevention is lacking and an area for future research.

Together, policy implementation and the structures and processes discussed by the case study schools contribute to the school’s implementation climate and capacity. Like leadership, implementation climate is an identified determinant of implementation outcomes and whilst research on implementation climate has been conducted within the health services sector (Aarons et al., 2014), less has been explored in education settings (Lyon et al., 2018). Newly developed tools that assess school readiness to implement a new evidence-based practice hold promise in their pragmatic use in guiding schools to address these determinants with targeted capacity building that meet their unique context and needs (Wanless & Domitrovich, 2015).

Staff commitment and ‘buy-in’ and responsibility for student wellbeing and responding to bullying were reported as the biggest implementation challenges by all case study schools. Regular communication of information (drip feeding) to staff and professional learning opportunities were helpful to overcome staff resistance to implementation. This helped to foster common student care and bullying prevention and management understandings among staff as well as feelings of responsibility for student wellbeing. Individual staff factors such as self-efficacy, skills and perceived benefit of the new practice are known to influence implementation and are often addressed though training and coaching to build staff competencies (Damschroder et al., 2009). Staff training has been identified as an important feature of bullying prevention interventions (Flygare et al., 2013; Cross et al., 2011), although it is well known to be insufficient alone in improving implementation outcomes (Fixsen et al., 2005). Case study school teams often saw a shift in staff commitment once student data were collected and presented to the whole-school staff. Classroom teachers were more motivated to address social issues or teach social and emotional skills when they knew their students’ strengths and areas requiring development. Partnerships with external agencies strengthened school delivery of student support (particularly for higher need students), reduced staff burden and gave students other skilled professionals with whom to connect.

A key mechanism for the translation of evidence into local school policy and practice was following the systematic implementation process for assessing, planning, implementing and reviewing their actions. A clear process with tools for data collection that informed planning and action, promoted accountability and imposed timelines and justification for staff time and roles was beneficial. However, school teams still required training in this implementation process. Communicating student and staff survey findings and other school data to all staff helped to create ‘buy-in’ and helped staff identify what aspects of implementation were important and why changes were being proposed. Regular follow-up and evaluations of bullying behaviours were also found to help support the effectiveness of bullying interventions (Flygare et al., 2013). Key to embedding best practice evidence into local school contexts was the compatibility to the school’s vision and strategic goals in creating a supportive culture. Schools found that a central integrated approach across the whole-school worked to build sustainability over the longer term and balance preventative, proactive approaches with targeted student support interventions.

In case study schools where implementation stalled for short periods of time, common barriers were identified that required specific capacity building attention to overcome. One example was the balance between staff roles. Some schools experienced a disconnect between leadership teams who wanted all staff to be responsible for student support, versus teaching staff who saw student support as the role of ‘other staff’. In other schools, low levels of responsibility for whole-school action to address bullying behaviours were experienced by staff who did not have a specific pastoral care role. This was often in the initial stages of the implementation where all staff was not fully informed and perhaps could not see the relevance of the intervention to them. Case study school team staff reported they needed more time to prepare themselves and to plan for implementation before approaching the wider whole-school staff. School staff also found this could be fast tracked by collecting student data first and using the findings to engage staff and validate areas of need. Data-driven decision-making tools were seen as the most powerful way to build school and staff capacity.

The initial implementation model developed featured seven stages to guide school staff through the process of implementing Friendly Schools. As a result of feedback from school teams and the challenges observed in ‘getting started’ in the first year, this process was simplified to five stages (collapsing stages 1 and 2 into the stage ‘explore strengths and needs’, stages 3 and 4 into ‘plan for improvement’ and stages 5 and 6 into ‘implement plan’). A dedicated ‘getting ready’ stage of support was added at stage 1 to allow focussed time for school teams to prepare and to secure staff commitment. The critical importance of this preparation stage is increasingly recognised though the development of theory and frameworks of determinants of readiness in organisational and behavioural health care (Weiner, 2009; Scaccia et al., 2015) and is beginning to be applied in education settings (Kingston et al., 2018). Practical measures, however, are still in the early stages of development and there is much work to be done before meaningful and validated tools are available to schools (Weiner et al., 2020).

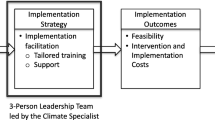

As a result of the findings in this study, two additional elements were added to the model to highlight the importance of building school capacity through (1) the identified drivers of quality implementation (leadership, organisational support and staff competencies) and (2) linking individual schools’ visions and goals to support the translation of evidence into school policy and practice and facilitate sustainability (see Fig. 2). The findings from this study are supported by research by the National Implementation Research Network (NIRN) whose ‘framework of implementation drivers’ provides detailed identification of the core elements within the areas of leadership, competency and organisation drivers (Bertram et al., 2015). Bertram and colleagues (2015) define implementation drivers as ‘the infrastructure elements required for effective implementation that support high fidelity, effective, sustainable programs’ (Bertram et al., 2015, pg. 481).

Strengths and Limitations of Study and Qualitative Framework Analysis

This study sought to describe school staffs’ subjective experiences of their implementation and capacity-building processes through a multi-site case study design. Seven case study schools were drawn from metropolitan and regional areas in Western Australia, but did not include schools from more distant regional areas. The number of schools and their location limits the transferability of the study findings. Social desirability bias may have occurred in school team members’ responses when they reported positive implementation experiences, especially given the positive relationship that developed between the researchers and the school staff over the four-year duration of the study. Other limitations include each school’s previous experiences implementing whole-school interventions and the attrition of one large case study school early in the study. Future research should examine implementation related issues in a larger sample of schools that are more representative of geographical, disadvantage and multicultural factors.

This study highlights the strengths of qualitative methods and data in helping to understand how contextual factors influence implementation of bullying prevention interventions. The use of comprehensive longitudinal qualitative data in this study is unique as intervention studies aimed to reduce bullying behaviours are rarely conducted (or their results reported) for longer than one year (Ttofi & Farrington, 2011). Additionally, the use of a multiple, embedded case study design enabled the collection of qualitative data over eight time periods in four years, across seven heterogeneous sites, adding greater breadth and depth to our understandings compared to a single case study site of interest.

Although the breadth of the data presented data management and synthesis challenges, the Framework Analysis method using NVivo matrices provided an efficient and pragmatic way to determine associations between different themes, both within and across school cases. Additionally, by automatically gathering all the information relevant to each theme as it is coded, this method enabled efficient comparison of the viewpoints of different individuals, such as staff versus principal perceptions. Although efficient in summarising the large volume of qualitative data and providing a way to visualise themes across school case studies and within each school case, the framework matrix can only map a limited number of features. One of the difficulties experienced by the researchers using the Framework Analysis was the ability to track the additional differences between case study schools’ implementation of Friendly Schools across timepoints. Capturing school implementation processes over a significant length of time is particularly important in the sustainability of whole-school bullying prevention which may take longer to deliver and achieve the required behaviour and social change (Ttofi & Farrington, 2011). If the researchers were to do the analysis again, multiple matrices may have been more effective in illuminating the data in different ways to answer questions of interest, although significantly adding to the time and resource burden on the study.

The Framework Analysis was beneficial for this study as it allowed for a combination of inductive and deductive thematic analysis and is not associated with a specific philosophical or theoretical approach (Gale et al., 2013). The case study schools piloted a research-informed implementation process so intentional questions were asked about its usefulness and appropriateness to assist with refinement whilst still openly exploring school staff perspectives of contextual barriers and enablers to successful implementation and tools and supports needed to address them. The NVivo matrices were also critical in providing an audit trail from the original raw data to the final themes as a quality assurance in the process of creating high level summaries of themes from large amounts of qualitative data.

Conclusion

Despite the abundance of research on bullying behaviours and their detrimental impact on the social and emotional wellbeing and mental health of children and young people, limited empirical data are available to determine the most effective ways to support schools’ implementation of interventions to reduce these harms. It is well established that the effectiveness of complex social interventions in schools requires a whole-school approach; however, schools often vary in their capacity to implement this approach with sufficient quality to make a real difference for students. This unique qualitative longitudinal multi-site school case study showed that school staff who use a systematic process and proactive capacity building to implementing a whole-school social and emotional wellbeing and bullying prevention intervention can overcome barriers and support implementation sustainability over time. As identified by Lewis and colleagues (2020), more research is needed to test the mechanisms and process by which implementation strategies affect implementation outcomes, to be tailored to each school’s contextual barriers and maximise the efficient use of scarce school resources. This study illustrated how the Framework Analysis method is a flexible qualitative analytical tool, relevant for applied intervention studies where insights are needed to be summarised from large amounts of contextual process data and aim to evaluate real-world implementation challenges in schools.

Availability of Data and Materials

In order to ensure data integrity, mediated access to the data will be available on request through password-protection, allowing only some data to be used and reused by authorized parties and through the signing of ethical agreements.

Code Availability

N/A.

References

Aarons, G. A., Hurlburt, M., & Horwitz, S. M. (2011). Advancing a conceptual model of evidence-based practice implementation in public service sectors. Administration and Policy in Mental Health. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-010-0327-7.

Aarons, G. A., Ehrhart, M. G., Farahnak, L. R., & Sklar, M. (2014). Aligning leadership across systems and organizations to develop a strategic climate for evidence-based practice implementation. Annual Review of Public Health, 35, 255–274. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182447

Aluttis, C., Van den Broucke, S., Chiotan, C., Costongs, C., Michelsen, K., & Brand, H. (2014). Public health and health promotion capacity at national and regional level: A review of conceptual frameworks. Journal of Public Health Research, 3(1), 37–42. https://doi.org/10.4081/jphr.2014.199

Axford, N., Bjornstad, G., Clarkson, S., Ukoumunne, O. C., Wrigley, Z., Matthews, J., Berry, V., & Hutchings, J. (2020). The effectiveness of the kiva bullying prevention program in Wales, UK: Results from a pragmatic cluster randomized controlled trial. Prevention Science, 21(5), 615–626. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-020-01103-9

Barnes, A., Pearce, N., Erceg, E., Runions, K. C., Cardoso, P., Lester, L., Coffin, J., & Cross, D. (2019). The Friendly Schools Initiative: Evidence-based bullying prevention in Australian Schools. In Peter K Smith (Ed.), Making an impact on school bullying: Interventions and recommendations (pp. 109–131). Routledge Psychological Impacts.

Barnes, Amy, Cross, D., Lester, L., Hearn, L., Epstein, M., & Monks, H. (2012). The invisibility of covert bullying among students: Challenges for school intervention. Australian Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 22(2), 206–226. https://doi.org/10.1017/jgc.2012.27

Baxter, P., & Jack, S. (2008). Qualitative case study methodology: Study design and implementation for novice researchers, 13(4), 544–559.

Beekhuyzen, J., Nielsen, S., & von Hellens, L. (2010). The Nvivo looking glass: Seeing the data through the analysis. QualIT Conference-Qualitative Research in IT & IT in Qualitative Research.

Bertram, R. M., Blase, K. A., & Fixsen, D. L. (2015). Improving programs and outcomes: Implementation frameworks and organization change. Research on Social Work Practice, 25(4), 477–487. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731514537687

Bradshaw, C. P. (2015). Translating research to practice in bullying prevention. American Psychologist, 70(4), 322–332. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039114

Burns, S., Hendriks, J., Mayberry, L., Duncan, S., Lobo, R., & Pelliccione, L. (2019). Evaluation of the implementation of a relationships and sexuality education project in Western Australian schools: Protocol of a multiple, embedded case study. BMJ Open, 9(e023582.). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023582

Choi, J. H., McCart, A. B., Hicks, T. A., & Sailor, W. (2019). An analysis of mediating effects of school leadership on MTSS implementation. Journal of Special Education, 53(1), 15–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022466918804815

Cook, C. R., Lyon, A. R., Locke, J., Waltz, T., & Powell, B. J. (2019). Adapting a compilation of implementation strategies to advance school-based implementation research and practice. Prevention Science, 20(6), 914–935. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-019-01017-1

Coyle, H. E. (2008). School culture benchmarks: Bridges and barriers to successful bullying prevention program implementation. Journal of School Violence, 7(2), 105–122. https://doi.org/10.1300/J202v07n02_07

Cross, D., Lester, L., Barnes, A., Cardoso, P., & K., H. (2015c). If it’s about me, why do it without me? Genuine student engagement in school cyberbullying education. International Journal of Emotional Education, 7(1), 35–51.

Cross, D., Waters, S., Pearce, N., Shaw, T., Hall, M., Erceg, E., Burns, S., Roberts, C., & Hamilton, G. (2012). The Friendly Schools Friendly Families programme: Three-year bullying behaviour outcomes in primary school children. International Journal of Educational Research. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2012.05.004

Cross, D., & Barnes, A. (2014). One size doesn’t fit all: Rethinking implementation research for bullying prevention. . In D. M. (Eds) In Schott R.M. and Søndergaard (Ed.), School bullying: New theories in context. Cambridge University Press.

Cross, D., Barnes, A., Papageorgiou, A., Hadwen, K., Hearn, L., & Lester, L. (2015b). A social-ecological framework for understanding and reducing cyberbullying behaviours. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 23, 109–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2015.05.016

Cross, D., Lester, L., & Barnes, A. (2015a). A longitudinal study of the social and emotional predictors and consequences of cyber and traditional bullying victimisation. International Journal of Public Health, 60(2), 207–217. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-015-0655-1

Cross, D., Monks, H., Hall, M., Shaw, T., Pintabona, Y., Erceg, E., Hamilton, G., Roberts, C., Waters, S., & Lester, L. (2011). Three-year results of the friendly schools whole-of-school intervention on children’s bullying behaviour. British Educational Research Journal. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411920903420024

Cross, D., Runions, K. C., Shaw, T., Wong, J. W. Y., Campbell, M., Pearce, N., Burns, S., Lester, L., Barnes, A., & Resnicow, K. (2019). Friendly Schools Universal Bullying Prevention Intervention: Effectiveness with secondary school students. International Journal of Bullying Prevention, 1(1), 45–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42380-018-0004-z

Cross, D., Shaw, T., Epstein, M., Pearce, N., Barnes, A., Burns, S., Waters, S., Lester, L., & Runions, K. (2018). Impact of the Friendly Schools whole‐school intervention on transition to secondary school and adolescent bullying behaviour. 495–513. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12307

Cross, D., Shaw, T., Hadwen, K., Cardoso, P., Slee, P., Roberts, C., Thomas, L., & Barnes, A. (2016). Longitudinal impact of the Cyber Friendly Schools program on adolescents’ cyberbullying behavior. Aggressive Behavior, 42(2), 166–180. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21609

Damschroder, L. J., Aron, D. C., Keith, R. E., Kirsh, S. R., Alexander, J. A., & Lowery, J. C. (2009). Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science, 4, 50. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-4-50.

Dix, K., Slee, P., Lawson, M., & Keeves, J. (2012). Implementation Quality of Whole-school Mental Health Promotion and Students' Academic Performance. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 17(1), 45–51.

Domitrovich, C. E., Bradshaw, C. P., Poduska, J. M., Hoagwood, K., Buckley, J. A., Olin, S., Romanelli, L. H., Leaf, P. J., Greenberg, M. T., & Ialongo, N. S. (2008). Maximizing the implementation quality of evidence-based preventive interventions in schools: A conceptual framework. Advances in School Mental Health Promotion, 1(3), 6–28.

Domitrovich, C. E., Li, Y., Mathis, E. T., & Greenberg, M. T. (2019). Individual and organizational factors associated with teacher self-reported implementation of the PATHS curriculum. Journal of School Psychology, 76(August 2018), 168–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2019.07.015

Durlak, J. A., & Dupre, Æ. E. P. (2008). Implementation matters: A review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. 327–350. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-008-9165-0

Espelage, D. L. (2014). Ecological theory: Preventing youth bullying, aggression, and victimization. Theory into Practice, 53(4), 257–264.

Evans, C. B. R., Fraser, M. W., & Cotter, K. L. (2014). The effectiveness of school-based bullying prevention programs: A systematic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 19(5), 532–544. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2014.07.004

Farrington, D. P., & Ttofi, M. M. (2011). Bullying as a predictor of offending, violence and later life outcomes. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 21, 90–98.

Fixsen, D. L., Naoom, S. F., Blasé, K. A., Friedman, R. M., & Wallace, F. (2005). Implementation research: A synthesis of the literature. University of South Florida, Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute, The National Implementation Research Network.

Flygare, E., Gill, P. E., & Johansson, B. (2013). Lessons from a concurrent evaluation of eight antibullying programs used in Sweden. American Journal of Evaluation, 34(2), 170–189. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098214012471886

Gaffney, H., Ttofi, M. M., & Farrington, D. P. (2021). What works in anti-bullying programs? Analysis of effective intervention components. Journal of School Psychology, 85(June 2020), 37–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2020.12.002

Gale, N. K., Heath, G., Cameron, E., Rashid, S., & Redwood, S. (2013). Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 13(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-13-117

Gearing, R. E., El-Bassel, N., Ghesquiere, A., Baldwin, S., Gillies, J., & Ngeow, E. (2011). Major ingredients of fidelity: A review and scientific guide to improving quality of intervention research implementation. Clin Psychol Rev, 31(1), 79–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.09.007

Gingiss, P., Roberts-Gray, C., & Boerm, M. (2006). Bridge-It: A system for prediciting implementation fidelity for school-based tobacco prevention programs. Prevention Science, 7(2), 197–207.

Goldsmith, L. J. (2021). Using framework analysis in applied qualitative research. Qualitative Report, 26(6), 2061–2076. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2021.5011

Greenberg, M. T. (2004). Current and future challenges in school-based prevention: The researcher perspective. Prevention Science, 5(1), 5–13. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:PREV.0000013976.84939.55

Guba, E. G., & Lincoln, Y. (1994). Competing paradigms in qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 105–117). Sage.

Hagermoser Sanetti, L. M., & Collier-Meek, M. A. (2019). Increasing implementation science literacy to address the research-to-practice gap in school psychology. Journal of School Psychology, 76(July), 33–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2019.07.008

Hawe, P., Noort, M., King, L., & Jordens, C. (1997). Multiplying health gains: The critical role of capacity building within health promotion programs. Health Policy, 39, 29–42.

Holt, M. K., Vivolo-Kantor, A. M., Polanin, J. R., Holland, K. M., DeGue, S., Matjasko, J. L., Wolfe, M., & Reid, G. (2015). Bullying and suicidal ideation and behaviors: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics, 135(2), e496–e509. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-1864

Iachini, A. L., Anderson-Butcher, D., & Mellin, E. A. (2013). Exploring best practice teaming strategies among school-based teams: Implications for school mental health practice and research. Advances in School Mental Health Promotion, 6(2), 139–154. https://doi.org/10.1080/1754730x.2013.784618

Jiménez-Barbero, J. A., Ruiz-Hernández, J. A., Llor-Zaragoza, L., Pérez-García, M., & Llor-Esteban, B. (2016). Effectiveness of anti-bullying school programs: A meta-analysis. Children and Youth Services Review, 61, 165–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.12.015

Johander, E., Turunen, T., Garandeau, C. F., & Salmivalli, C. (2021). Different approaches to address bullying in KiVa schools: Adherence to guidelines, strategies implemented, and outcomes obtained. Prevention Science, 22(3), 299–310. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-020-01178-4

Kingston, B., Arredondo, S., Allison, M., Elizabeth, D., Monica, S., Shipman, K., Goodrum, S., Woodward, W., Witt, J., Hill, K. G., Elliott, D., & Kingston, B. (2018). Building schools’ readiness to implement a comprehensive approach to school safety. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 21(4), 433–449. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-018-0264-7

Langford, R., Bonell, C., Jones, H., Pouliou, T., Murphy, S., Waters, E., Komro, K., Gibbs, L., Magnus, D., & Campbell, R. (2015). The World Health Organization’s health promoting schools framework: A Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health, 15(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1360-y

Leeman, J., Birken, S. A., Powell, B. J., Rohweder, C., & Shea, C. M. (2017). Beyond “implementation strategies”: Classifying the full range of strategies used in implementation science and practice. Implementation Science, 12(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0657-x

Lendrum, A., & Humphrey, N. (2012). The importance of studying the implementation of interventions in school settings. Oxford Review of Education, 38(5), 635–652. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2012.734800

Lendrum, A., Humphrey, N., & Greenberg, M. (2016). Implementing for success in school-based mental health promotion: The role of quality in resolving the tension between fidelity and adaptation. In Mental health and wellbeing through schools: The way forward. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315764696

Lester, L., Cross, D., Dooley, J., & Shaw, T. (2013). Developmental trajectories of adolescent victimization: Predictors and outcomes. Social Influence, 8(2–3), 107–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/15534510.2012.734526

Lewis, C. C., Boyd, M. R., Walsh-Bailey, C., Lyon, A. R., Beidas, R., Mittman, B., Aarons, G. A., Weiner, B. J., & Chambers, D. A. (2020). A systematic review of empirical studies examining mechanisms of implementation in health. Implementation Science, 15(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-020-00983-3

Liamputtong, P. (2013). The science of words and the science of numbers. In Research method in health: Foundations for evidence-based practice (pp. 3–23). Oxford University Press.

Locke, J., Lawson, G. M., Beidas, R. S., Aarons, G. A., Xie, M., Lyon, A. R., Stahmer, A., Seidman, M., Frederick, L., Oh, C., Spaulding, C., Dorsey, S., & Mandell, D. S. (2019). Individual and organizational factors that affect implementation of evidence-based practices for children with autism in public schools: A cross-sectional observational study. Implementation Science, 14(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-019-0877-3

Lyon, A. R. (2017). Implementation science and practice in the education sector. 1–8. https://education.uw.edu/sites/default/files/ImplementationScienceIssueBrief072617.pdf

Lyon, A. R., Cook, C. R., Brown, E. C., Locke, J., Davis, C., Ehrhart, M., & Aarons, G. A. (2018). Assessing organizational implementation context in the education sector: Confirmatory factor analysis of measures of implementation leadership, climate, and citizenship. Implementation Science, 13(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0705-6

Martinez, R. G., Lewis, C. C., & Weiner, B. J. (2014). Instrumentation issues in implementation science. Implementation Science, 9, 118. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-014-0118-8.

Modecki, K. L., Minchin, J., Harbaugh, A. G., Guerra, N. G., & Runions, K. C. (2014). Bullying prevalaence across contexts: A meta-analysis measuring cyber and traditional bullying. Journal of Adolescent Health, 55(5), 602–611.

Moore, S. E., Norman, R. E., Suetani, S., Thomas, H. J., Sly, P. D., & Scott, J. G. (2017). Consequences of bullying victimization in childhood and adolescence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World Journal of Psychiatry, 7(1), 60. https://doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v7.i1.60

NVivo qualitative data analysis software; Version 10. (2012). QSR International Pty Ltd.

O’Donoghue, K., & Guerin, S. (2017). Homophobic and transphobic bullying: Barriers and supports to school intervention. Sex Education, 17(2), 220–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2016.1267003

Ollis, D., & Harrison, L. (2016). Lessons in building capacity in sexuality education using the health promoting school framework. Health Education, 116, 138–153.

Pearce, N., Cross, D., Monks, H., Waters, S., & Falconer, S. (2011). Current evidence of best practice in whole-school bullying intervention and its potential to inform cyberbullying interventions. Australian Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 21(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1375/ajgc.21.1.1

Pennell, D., Campbell, M., Tangen, D., Runions, K. C., Brooks, J., & Cross, D. (2020). Facilitators and barriers to the implementation of motivational interviewing for bullying perpetration in school settings. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 61(1). https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12502

Potter, C., & Brough, R. (2004). Systemic capacity building: A hierarchy of needs. Health Policy and Planning, 19(5), 336–345. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czh038

Rapee, R. M., Shaw, T., Hunt, C., Bussey, K., Hudson, J. L., Mihalopoulos, C., Roberts, C., Fitzpatrick, S., Radom, N., Cordin, T., Epstein, M., & Cross, D. (2020). Combining whole-school and targeted programs for the reduction of bullying victimization: A randomized, effectiveness trial. Aggressive Behavior, 46(3), 193–209. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21881

Ritchie, J, & Spencer, L. (2002). Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In A. M. Huberman & M. B. Miles (Eds.), Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. The qualitative researcher’s companion. SAGE Publications, Inc. SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412986274

Roberts-Gray, C., Gingiss, P. M., & Boerm, M. (2007). Evaluating school capacity to implement new programs. Evaluation and Program Planning, 30(3), 247–257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2007.04.002

Saldana, L., Chamberlain, P., Bradford, W. D., Campbell, M., & Landsverk, J. (2014). The Cost of Implementing New Strategies (COINS): A method for mapping implementation resources using the Stages of Implementation Completion. Child Youth Serv Rev. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2013.10.006