Abstract

This paper interrogates the belief in toolkitting as a method for translating AI ethics theory into practice and assesses the toolkit paradigm’s effect on the understanding of ethics in AI research and AI-related policy. Drawing on a meta-review of existing ‘toolkit-scoping’ work, I demonstrate that most toolkits embody a reductionist conception of ethics and that, because of this, their capacity for facilitating change is limited. Then, I analyze the features of several ‘alternative’ toolkits–informed by feminist theory, posthumanism, and critical design–whose creators recognize that ethics cannot become a box-ticking exercise for engineers, while the ethical should not be dissociated from the political. This analysis then serves to provide suggestions for future toolkit creators and users on how to meaningfully adopt the toolkit format in AI ethics work without overselling its transformative potential: how different stakeholders can draw on the myriad of tools to achieve socially desirable results but reject the oversimplification of ethical practice that many toolkits embody.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In the late 2010s, AI professionals appeared ‘aware of the potential importance of ethics in AI,’ but were left with ‘no tools or methods for implementing ethics’ in their work [24, p. 2148]. It is in response to this apparent lack of appropriate resources that researchers have started to investigate the needs of industry practitioners [16] and analyze potential strategies for translating the theory of AI ethics–conceptions of accountability, fairness, transparency, trustworthiness, and justice, among other ideas and values–into AI development and deployment practice [22]. To meet the pronounced need for ‘tools for implementing ethics’ in AI, numerous teams in industry, academia, and civil society organizations have started to release various kinds of toolkits for responsible, ethical AI.

The OECD’s Catalogue of Tools and Metrics for Trustworthy AI is the biggest collection of such tools, toolkits, guidelines, frameworks, and standards–meant to ‘help AI actors develop and use trustworthy AI systems and applications that respect human rights and are fair, transparent, explainable, robust, secure and safe’ [26]. Some of the tools included in the Catalogue are categorized as technical, intended for machine learning engineers and data scientists, to help, for instance, with assessing the quality of the data used to train a given model; some are procedural, guiding those who oversee the development process to, for example, conduct an assessment of the end product’s impact on human rights; and some are educational, introducing development teams to concepts such as ‘trustworthiness’ and explaining how they relate to specific design decisions. While the OECD repository was created to help disseminate already available toolkits for ethical AI and allow for their classification and comparative analysis, I refer to it at the outset because it points to the diversity of formats adopted by different teams in response to the challenge of translating AI ethics theory into responsible AI practice: ranging from interactive, web-based applications, to static documents featuring checklists, sets of instructions, or lists of issues to consider, aiming to intervene at different stages of the development process and targeting different stakeholder groups. Despite the classification system proposed by the OECD, we lack a clear and consistent definition of a ‘toolkit’ in AI ethics research and practice, or how it differs from a ‘method,’ a singular ‘tool,’ or ‘guideline.’ Since terms such as ‘responsible’ ‘ethical,’ ‘trustworthy,’ or ‘human-centered,’ are also used largely interchangeably in the AI ethics discourse, for the purposes of this paper an AI ethics toolkit refers to any type of document, product, or website whose explicit aim is to facilitate change in the ways in which AI systems are designed, deployed, or governed and to ensure that the results of development lead to desirable social consequences.

The OECD Catalogue also serves as a poignant illustration of what we could call the ‘toolkittifcation’ trend in AI ethics [15]. If only a few years ago there seemed to be a lack of relevant tools and resources for producers of AI systems to consider ethics throughout development, now, at the time of writing, the OECD collection features more than seven hundred toolkits that promise to facilitate precisely the difficult work of translating AI ethics theory into practice. Despite various critiques of the toolkit format as a method for addressing complex ethico-political questions in design [3, 15, 23, 29], the sheer number of available responsible AI toolkits attests to the dominance of the toolkit seen as a tangible, operationalizable, and effective instrument of ethics for technology design–a means to an ‘ethical’ end.

The main objectives of this paper are, then, to interrogate the belief in toolkitting as a viable method for reorienting AI practice towards socially desirable goals and to assess its effect on the understanding of ‘ethics’ in AI research and policy; to analyze the features of several toolkits whose creators recognize that the conception of the ethical that presupposes the toolkits’ creation can never be truly dissociated from the political, while ethics cannot be turned into a box-ticking exercise for engineers; and to provide recommendations for future toolkit creators and users on how to meaningfully adopt the toolkit format in ethical AI work without overselling its transformative potential. In Part 2, I start by exploring the ethico-political assumptions that underly most ethical AI toolkits. Through a meta-critique of toolkits (drawing on a review of existing ‘toolkit-scoping’ work), I demonstrate that a reductionist conception of ethics, seemingly dissociated from politics, that informs most efforts at reshaping AI development standards, results in the creation of toolkits whose capacity for facilitating change and challenging the status quo is limited. Then, in Part 3, I analyze several ethical AI toolkits that have emerged as alternatives to those most widely adopted in industry–toolkits that draw on intersectional feminist critique, posthuman theory, and decolonial theory, and that remain absent from the OECD Catalogue and unaccounted for by the ‘toolkit-scoping’ papers that inform the meta-critique of the toolkit ‘landscape’ in Part 2. I refer to these ‘alternative’ toolkits to argue that the role that toolkits may play in reorienting technology design towards socially desirable outcomes relates to their potential for facilitating power-sensitive conversations between different stakeholder groups and epistemic communities. Finally, in the concluding section, referring to broader theories and critiques of toolkitting as a method for structuring the design process, I suggest how different stakeholders can draw on the myriad of available tools, ranging from big tech companies’ guidelines to feminist design ideation cards, to achieve positive, socially desirable results, while rejecting the oversimplification of ethical practice and technosolutionism that many responsible AI toolkits embody.

2 The ethico-politics of AI ethics toolkits

2.1 Analyzing the toolkits ‘landscape’

It is precisely because of the abundance of ethical AI toolkits–overwhelming for any design team in search of an appropriate tool or guideline–that ‘toolkit-scoping’ has become a sub-genre of AI ethics scholarship. Numerous articles aim to analyze various aspects of ‘the landscape’ of ethical AI toolkits to uncover trends in what is already available and highlight what is still missing. Some studies examine the convergences of the values, principles, and goals–across institutions, sectors, countries, or regions–that the toolkits foreground as crucial to ensuring that AI development is carried out responsibly [4, 11, 19, 20, 30]. Some analyses focus on the question of the toolkits’ usability [21, 24, 32] or compare the toolkits’ formats and the methods they introduce to their intended users [5, 31]. Other surveys reveal consistencies in how the toolkits’ creators envision the work of ethics in AI design: what traditions of ethics, if any, the toolkits draw upon [4, 12, 13, 35]; what stage of development this work is meant to be carried out at [4, 5]; and which stakeholder groups are to be involved in the process [5, 12].

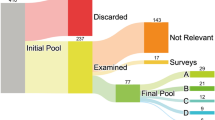

While these studies adopt different analytical angles and use distinct selection criteria for ethical AI toolkits to be taken into consideration, collectively–as I will explain in what follows–they point to several, consistent categories of shortcomings in the design of the toolkits themselves. To prepare a systematic meta-critique of the AI ethics toolkits landscape, I looked for academic papers published in 2019 or later, presenting the findings of reviews or surveys of at least twenty responsible/ethical/trustworthy AI guidelines/toolkits/tools. I searched several databases (Google Scholar, the ACM Digital Library, Web of Science, SSRN, and arXiv) by terms such as ‘AI guidelines,’ ‘AI toolkits,’ ‘AI ethics toolkit review,’ ‘ethical ML toolkit review,’ and variations of these. Eight papers met the criteria for inclusion in the meta-critique [4, 5, 13, 19, 20, 24, 30, 35]; two other articles [11, 12] that did not come up in the database search but were cited by nearly all the initial eight papers were also included in the meta-critique collection. Three other papers repeatedly showed up in the search [21, 31, 32], but did not meet all the criteria for inclusion, as they present in-depth comparative analyses of a smaller number of toolkits.

The primary goal of the meta-critique is to reveal that, despite the sheer number of available options, most ethical AI toolkits are informed by the same set of ethico-political assumptions–ideas about ethical reasoning as it relates to the conceptions of agency, power, and individual as well as collective responsibility–that negatively impact the toolkits’ potential to reorient practice towards socially desirable outcomes. When surveying the papers for consistencies in what the papers’ authors highlight as limiting the toolkits’ positive influence on design practice and in what they recommend to future toolkit creators, I considered the following questions: What conceptions of ‘ethics’ do the toolkits refer to, explicitly or implicitly? Which values, principles, or goals do the toolkits foreground as key to responsible AI development that they promise to facilitate? Whom do they address as the agents of change? To what extent is the transformation of practices–that the toolkits are meant to enable–envisioned as a matter of individual responsibility of designers? Are stakeholders other than designers accounted for? If so, do the toolkits present any methods for engaging these stakeholders?

2.2 Meta-critique of AI ethics toolkits: the toolkits’ limitations

In this section, I present the results of the meta-critique of the toolkits landscape, pointing to several types of limitations that determine the outcomes of most attempts at ‘toolkittifying’ AI ethics. These limitations relate to: the toolkits’ foundational ‘deficiencies,’ reflective of the omissions in the lists of values and principles they are meant to help translate into practice; a reductionist, technosolutionist conception of ethics–seemingly dissociated from politics–that most toolkits embody; and the co-optation of concepts and methods derived from critical studies of design and technology (such as participatory or inclusive design) decontextualized in ways that foreclose their meaningful, power-sensitive implementation in the AI development process.

The majority of responsible AI toolkits carry foundational ‘deficiencies’ because they are bound to reflect the limitations of the lists of values and principles that underlie their creation. While most toolkits feature values such as accountability, privacy, trustworthiness, or fairness [11, 19, 20], the ideals and goals of solidarity, or the prioritization of human co-flourishing as opposed to ‘radical individualism’ [19], environmental sustainability, or the commitment to minimizing the negative effect of technological development on the environment [19, 20], as well as labor rights or the rights of children [20] are consistently omitted. Several studies also highlight how design values and principles statements–that the toolkits are supposed to help translate into action–frame the quest for responsible AI as a universal, species-wide concern, failing to acknowledge that the values in question might be interpreted differently around the globe, and that the available lists of principles exclude the values prioritized by societies and groups underrepresented in mainstream AI ethics–as embodied by ethical AI toolkits [12, 19, 20].

We could argue that most ethical AI toolkits incorporate a reductionist conception of ethics because far too often they frame ethical practice as a matter of compliance with already existing standards and regulations–on the part of developers/designers/data analysts–rather than an inquiry into the motivations behind development, or an analysis of wider, socio-environmental consequences of technological production. Several studies emphasize the ‘technosolutionist’ character of ethical AI toolkits, as the majority of available tools approach ethical reasoning as directly translatable into immediate technological and procedural ‘fixes’ [13, 35] to the already established development pipeline. Informed by this form of technosolutionism, the majority of toolkits for ethical AI not only overlook the full complexity of the decision-making processes at play [24], but also leave no space for questioning the justifiability of starting a given development project in the first place. It is precisely this focus on what is immediately and visibly ‘fixable’ at the product development stage that results in the toolkits’ failure to prompt the questioning of business strategies behind particular technical decisions [4, 12], as well as to draw attention to–and provide guidance on mitigating–the undesirable, indirect social and environmental costs of technology development [13, 20, 30].

Numerous toolkits and guidelines gesture towards the need for ‘inclusion’ of diverse ‘stakeholders’ in design as a matter of ensuring that development leads to desirable outcomes. These calls for stakeholder engagement, however, often point to external experts, such as lawyers [12], rather than those minoritized stakeholder groups who bear the brunt of the new technologies’ harmful impacts–stakeholders referred to (problematically, but suggestively) as ‘voiceless’ in one toolkit-scoping paper, a category comprising both the ‘[t]raditionally marginalized groups with limited voice in society’ and ‘the environment’ [5, p. 412]. Several studies emphasize that even the toolkits that do prescribe minoritized stakeholders’ participation in the design process fail to account for–and help navigate through–the difficulties of facilitating power-sensitive conversations between those who are already present at the metaphorical design table and those whose voices have been excluded or ignored in the past [5, 35]. This constitutes an especially concerning limitation of the available toolkits, since the calls for participatory technology design, when approached this way, are more likely to encourage ‘participation-washing’ rather than ‘participation as justice’ [33]: a genuine attempt to actively include, not extract insights from, minoritized stakeholder groups. Indeed, even when ethical AI toolkits operationalize the language of social justice, this is more likely to be a sign of corporate co-optation of the critical terminology than that of genuine commitment to aligning business and design processes with the goals of equitable human co-flourishing and environmental sustainability – the normative ends of the critical work from which the terminology derives [12, 33].

2.3 Meta-critique of AI ethics toolkits: recommendations for future toolkit makers

As I demonstrated in the previous section, consistent patterns of critique emerge in various surveys evaluating ethical AI toolkits, pointing to several types of limitations in the design of the toolkits themselves. These toolkit-scoping reviews also converge on a set of recommendations for future toolkit creators.

If most ethical AI toolkits overlook the values of solidarity (or human co-flourishing) and environmental sustainability, as well as other values and principles prioritized by communities underrepresented in mainstream AI ethics, then the solution to these foundational ‘deficiencies’ appears to lie in engaging with the ethical and epistemological frameworks from which the missing values originate when designing new toolkits. Future toolkit creators are encouraged to consider, for instance, feminist ethics, ethics of care, decolonial theory, and Indigenous epistemologies [4, 35]–a recommendation that echoes a growing number of calls for AI ethicists to draw on relational philosophies in their work [6, 9]. This suggestion for future toolkit makers also points to a belief inscribed in the toolkit as a means of ‘reforming’ dominant design practices: a belief that, by exposing themselves to ‘alternative’ ethical and epistemological positions, toolkit makers might conceive of ‘alternatives to the dominant paradigm of the toolkit’ [35, p. 16], and that, by developing such alternatives, they might then enable a wider shift in design without requiring–and this is key–individual designers or design teams, the intended users of most responsible AI toolkits, to directly engage with these positions.

Since most responsible AI toolkits embody a reductionist understanding of ethics–with the checklist as its primary ‘instrument’ [13]–the recommendation for future toolkits makers is to adopt different formats that reflect the complexity of ethical reasoning in design, accounting for the indirect social and environmental costs of AI development. To depart from the technosolutionism implicit in most available toolkits, new, alternative toolkits are supposed to prompt design teams to draw on non-technical expertise and to consult with representatives of groups that are most likely to experience the negative consequences of AI development [5, 13, 35]–to only then consider and implement strategies for mitigating the undesirable impact. This second set of recommendations also points to another, somewhat paradoxical feature of the toolkit conceived as a means of transforming design practices: while toolkits are meant to make the difficult, often uncomfortable critical work of assessing and mitigating socio-environmental harms of technology development more easily executable, the format of the toolkit itself should never make the task at hand appear straightforward and free from friction. A good toolkit, it seems, should reflect, rather than reduce, the full complexity of the process of identifying and addressing ethical challenges in design–even if the toolkit aims to facilitate this process by giving it structure.

Finally, as the majority of available toolkits fails to guide development teams through the exercise of meaningfully including the so-called ‘voiceless’ [5]–or, more appropriately, ignored or silenced–stakeholders in design ideation and testing, and to enable participation as justice, future toolkit makers are encouraged to create toolkits that ‘structure the work of AI ethics as a problem for collective action’ [35, p. 17] undertaken not only by professional designers within technology companies, but also the communities most likely to be impacted by AI. The recommendation for future toolkit makers is to create toolkits that not only make designers already present at the ‘design table’ aware of broader power dynamics that either enable or foreclose ethical technology design but also, and more importantly, empower a wider array of stakeholders to challenge these preexisting relations, as well as verbalize their needs and demand change [5, 30, 35]. A good, effective design toolkit in this framing is supposed to lead stakeholders through the challenges of building new systems responsibly and, simultaneously, building new movements–within and outside of tech companies–that make attempts at transforming design practices both possible and consequential. The vision that emerges from this final set of recommendations is that of the toolkit as a means of structuring the design process and affecting political change–approaching responsible technology development not only as a matter of ethics but also, and perhaps more importantly, that of politics.

3 The wider landscape of AI ethics toolkits

3.1 Toolkitting otherwise

Although the toolkit-scoping articles that informed my meta-critique of the toolkit ‘landscape’ collectively point to the need for ‘alternatives’ to the dominant paradigm of the ethical AI toolkit as if such alternatives were not available, in Part 3 I refer to examples of toolkits produced by critical design theorists and practitioners that constitute precisely such alternatives–alternatives excluded by the OECD database and all the toolkit-scoping papers that informed my meta-critique of the toolkits ‘landscape’ in Part 2. Drawing on interventions in intersectional feminism, decolonial theory, post-development studies, and posthuman theory, among other fields, critical design scholars point out that universalist approaches to design, practices that aim to streamline and standardize the design process and its products, in reality cater to the dominant groups in society and thus ‘erase certain groups of people, specifically those who are intersectionally disadvantaged or multiply burdened under white supremacist heteropatriarchy, capitalism, and settler colonialism’ [8, p. 19]. To deliver socially (and environmentally) desirable outcomes, design practice, they argue, can no longer be conceived of as ‘an expert-driven process focused on objects and services within a taken-for-granted social and economic order’ [10, p. 53] but instead must be reimagined from the standpoint of those marginalized and minoritized groups. For this reorientation to happen, practices and methods that are ‘participatory, socially oriented, situated, and open ended and that challenge the business-as-usual mode of being, producing, and consuming’ [10, p. 53] should be brought to the fore. This is precisely what the ‘alternative’ toolkits that I focus on in this section aim to achieve.

While Part 2 served as a meta-critique of the ‘landscape’ of responsible AI toolkits, Part 3, rather than a comprehensive survey of ‘alternatives,’ is an analysis of two toolkits informed by broadly understood critical design theory. The first, the Intersectional AI Toolkit [17], is a website created by the artist and scholar Sarah Ciston in 2021 and maintained–thanks to its wiki-style format–by a community of contributors; it comprises downloadable design ideation workshop materials and short explainers on both intersectional feminism and machine learning for non-experts. The second, the Notmy.ai website [25], is an ongoing attempt at developing ‘a feminist toolkit to question AI systems’ [34] by the Brazilian feminist organization Coding Rights, led by the researcher and activist Joana Varon in partnership with the activist Paz Peña, gathering resources such as instructions on how to investigate the harms perpetuated by AI systems already in use and design ideation cards helping marginalized stakeholders to conceive of new technologies and systems.

The meta-critique of the toolkits landscape revealed that future toolkit makers are consistently encouraged to consider ‘alternative’ philosophical foundations–feminist ethics and decolonial theory, among others–as the basis for AI ethics toolkittification projects; the two selected toolkits stem precisely from such ‘alternative’ foundations. The Intersectional AI Toolkit, as the name suggests, explicitly draws on intersectional feminist critique to ensure that ‘queer, antiracist, antiableist, neurodiverse, feminist communities’ can bring to bear on what kinds of systems are seen as desirable. The Notmy.ai Toolkit departs from the assumption that ‘decolonial feminist approaches to life and technologies are great instruments to envision alternative futures and to overturn the prevailing logic in which A.I. systems are being deployed.’ In my reading of the ‘alternative’ toolkits, I elucidate what these toolkits do differently as a result of their creators’ ethico-political commitments–how the toolkits restructure the relationships between different actors involved in the design process and between individual tools and methods to ensure that their adoption leads to socially desirable outcomes, where the understanding of the desirable is tied to the goals of social justice. I aim to ‘distill’ the qualities of the ‘alternative’ toolkits that could, potentially, inform the design (or re-design) of other AI ethics toolkits.

3.2 Multiplying the sites of intervention

Remarkably, the primary goal of the alternative toolkits is to gather people not tools. The Notmy.ai Toolkit promises to ‘build bridges’ between different activist groups, including organizations defending women’s and LGBTIQ+ rights, to collectively voice objection against the use of AI in specific domains (for instance, to manage access to public services) and to facilitate the process of co-imagining alternative applications that empower, rather than harm, vulnerable groups. The Intersectional AI Toolkit, a community-maintained repository of collaboratively produced materials–an explicit reference to ‘the 90s zine aesthetics and politics’–similarly aims to bring together ‘some of the amazing people, ideas, and forces working to re-examine the foundational assumptions built into these technologies’; it does so not to align different stakeholders’ views or needs, but rather to facilitate conversations and ‘engage tension.’ The alternative toolkits thus depart from the premise that responsible technological development is not a matter for technology executives or design leads to ‘solve’ internally; that it is conditional on the involvement of civil society and minority rights organizations; and that it is only through surfacing friction–potential conflicts between the interests of these different groups–that ethical practice becomes possible. The toolkits constitute ‘alternatives’ to the ‘mainstream’ ones analyzed in Part 2 precisely because, through their staging of collective deliberation and attending to conflict, they attempt to repoliticize both ‘ethics’ and ‘design’–by contrast with AI ethics toolkits that approach certain challenges, such as those related to ‘algorithmic bias,’ as technical, rather than deeply ethico-political.

One of the tools from the Notmy.ai collection, the Oppressive AI Framework, in particular illustrates how toolkittification of AI ethics can serve to reinscribe the political into ‘ethical’ tech design–ensuring that the understanding of ethical practice in this context is not limited to interrogating particular design decisions but rather extends to questioning broader socio-political arrangements that make only some AI development projects appear realizable or desirable, and to whom. The Oppressive AI Framework introduces users to feminist theory-informed ‘categories of harms,’ such as ‘embedded racism’ or ‘colonial extraction,’ perpetuated by AI. Accompanied by real-life examples of AI applications in South America analyzed through the Framework, the tool demonstrates how users can examine injustices related to AI development and deployment as a basis for seeking redress and questioning the justifiability of certain AI projects. Toolkittification in this framing does not foreclose available options by turning ‘ethics’ into a finite list of actions to be carried out and ticked off during development, but rather leads to their multiplication, where a decision not to design or deploy a given system is also considered viable.

This sort of multiplication is what sets the ‘alternative’ toolkits apart from the ‘mainstream’ ones. In her Cloud Ethics, Louise Amoore points to the distinction between an encoded ethics, delineating what humans or algorithms can or cannot do, and a relational ethics–an ‘ethics of the orientation one has to oneself and to others’ [1, p. 165]–to argue it is the latter that we should consider to determine what constitutes ‘responsible’ technology design. This approach to ethics, what Amoore calls cloud ethics, does not aim to encode rules for human designers or algorithms, but rather attend to how algorithms devise their own ethical patterns and how these patterns impact the ways in which we relate ‘to ourselves and to others’ [1, p. 6]. While most ethical AI toolkits embody the former approach (as the meta-critique of the toolkits landscape confirms), the alternative toolkits give an indication of what relational ethics might look like in technology design practice: how we can give this kind of critical work structure, while rejecting formulaicity and reductionism implicit in most attempts at AI ethics toolkittification. For Amoore, cloud ethics in practice would take on the form of ‘a crowded court in the sense that my approach multiplies the possible sites of intervention and responsibility’ [1, p. 25]; we could say that, in their attempt to gather people, not only tools, the alternative toolkits aim to convene precisely the kind of ‘crowded court’ that Amoore gestures towards. In contrast to the ‘mainstream’ toolkits, however, the ‘alternative’ toolkits not only underscore the importance of assembling a diverse array of voices to widen participation in AI design but also, and more importantly, offer insights into how such conversations can be staged in a power-sensitive way.

3.3 Facilitating power-sensitive conversations

To allow for meaningful, power-sensitive inclusion of diverse stakeholders in the ‘crowded court’ of design, the alternative toolkits prioritize empowering the so-called ‘voiceless’ (or, more appropriately, silenced) stakeholders to formulate and communicate their concerns, needs, and ideas for development. While the Intersectional AI Toolkit offers accessible resources on coding and machine learning principles for non-experts, the Notmy.ai Toolkit directs users to the Oracle for Transfeminist Technologies, a deck of tarot-styled cards prompting players to consider values such as ‘solidarity,’ ‘decoloniality,’ ‘multispeciesm,’ or ‘socio-environmental justice’–to co-imagine how AI could be applied in a desirable future ‘where technologies are designed by people who are too often excluded from or targeted by technology in today's world.’ Designers often work with card-based tools to scope ideas [28] and indeed there are cards decks that introduce professionals to Kimberlé Crenshaw’s intersectionality framework to help them question who it is they are designing for, highlighting intersecting characteristics such as race, age, gender, or disability to support designers in thinking critically about the intended users of their products (see: [18]). However, by catering specifically to those typically excluded from the design process but disproportionately impacted by technological development, the Intersectional AI Toolkit and the Notmy.ai Toolkit not only encourage the interrogation of who constitutes the generic ‘user’ at the center of design but also, and more importantly, challenge and expand the understanding of the ‘designer.’ By providing their target audience with an introduction to the technical principles behind machine learning and to the capabilities and limitations of AI, as well as by encouraging the reimagining of AI from the standpoint of marginalized groups, the toolkits aim to ensure that ‘inclusive’ practices lead not to further extraction of insights from the most vulnerable in society but rather to the redistribution of power at the metaphorical design table.

This is not to suggest that the alternative toolkits would not prove beneficial to those who already have a seat at the table. Most toolkits aimed at advancing diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) in AI development focus on persuading those in positions of power of the value, including direct financial value, of inclusivity in AI design [15]. Rather than merely providing information on the benefits of diversity in design, alternative toolkits for business decision-makers, software engineers, or design leads could function as training grounds for cultivating what design theorist Ahmed Ansari refers to as ‘epistemic humility’–a ‘sensitivity to difference’ that, as he argues ‘design research and practice need, in order to move toward making [a more just and equitable] world possible’ [2, p. 19]. The Oracle cards aim to nurture precisely this kind of sensitivity by guiding players to ‘reflect on who you are’ instead of ‘pretending that you are someone else and you know what they need’; they pose questions like ‘What body do you inhabit? Where are you situated? What privileges and burdens accompany your body and surroundings?’–and make clear that these are fundamental to ethical design practice. It is precisely because of this function–prompting critical introspection and the acknowledgment of partiality of knowledge on the part of the toolkit users–that the alternative toolkits could be said to provide ground for translation between different stakeholder groups. Translation should be understood here in terms of Donna Haraway’s work on feminist epistemologies: translation as ‘always interpretive, critical, and partial’ and, as such, enabling ‘power-sensitive, not pluralist, “conversation[s]”’ [14, p. 589]. It is this conception of translation, as enabling power-sensitive conversations, that underlies the design of the alternative toolkits and that departs from the misapprehension of participatory methods as tactics for fulfilling visible diversity quotas.

The alternative toolkits make clear that ‘responsible’ AI can only take shape through such conversations. As they aim to empower those whose voices usually do not bring to bear on business and design decisions behind tech development and to guide those in positions of power to cultivate epistemic humility as the basis for ethical work, the toolkits give an indication of how such conversations should be structured to ensure that pre-existing power relations do not foreclose the positive effect of participatory and inclusive practices. Unlike most AI ethics toolkits that lack concrete guidance on meaningful ‘stakeholder involvement,’ the alternative toolkits–precisely because they focus on ensuring that conversations in these new design constellations are power-sensitive–point to how participation can become the means for reorienting design towards justice, how participation understood this way is justice.

3.4 Foregrounding the need for ‘ongoingness’ of ethics work

If the toolkits facilitate the process of questioning and restructuring the relationship between users and designers on a broader scale, this process is mirrored in the design of the toolkits themselves. The Intersectional AI Toolkit is ‘showing rough edges and edit marks, in the belief that no text is final, all code can be forked, and everything is better with friends.’ As a wiki page where users can trace the evolution of different sections, the Toolkit not only invites users to become co-designers, to comment on and remix content, but also to delve into the project’s archive–making the process of toolkittification itself transparent and open-ended. Similarly, the Notmy.ai Toolkit emphasizes that the tools it contains are not to be seen as ‘written in stone’ but rather as ‘a work in process,’ and that depending on when and where they are used, they will be ‘re-shaped according to the particular context and its oppressions.’ The Toolkit also actively invites users to directly contribute to its toolkittification project, to collaboratively develop new application cases, and to provide feedback on individual tools and the Toolkit as a whole. The alternative toolkits thus make clear that the ownership over the tools and resources they gather is dispersed, that they belong to the community that has helped to co-create them–the community they aim to foster and empower; that ethics work demands negotiation and conversations, and that it rests in making these negotiations and conversations visible; and that no tool or toolkit is ever finalized–that ethics work must remain continuous, ‘in progress.’

The alternative toolkits thus indicate that the process of toolkittification must itself be seen as open-ended, a forever ongoing negotiation of the ethics and politics that should shape practice. Indeed, as the creator of the Intersectional AI Toolkits emphasizes, responsible AI cannot be defined by a ‘singular ethic or aesthetic–but rather a meta-ethics of multiplicity and intersubjective relations’ [7, p. 5]. In this perspective, toolkittification–the creation, selection, and utilization of toolkits–does not imply foreclosure, simplification, or reductionism; rather, it fosters multiplicity, negotiation, and collective mobilization. It becomes an exercise in meta-ethics of design, challenging assumptions about who has the authority to design and where interventions should extend beyond the design process itself. Toolkittification in this framing is not only an expression of care for how technologies are made but also how they are imagined and who gets to partake in that imagining. And it is within this mirroring between the design of the toolkits themselves and the kind of design they aim to facilitate that lies a hint of what we can glean from the alternative toolkits to understand the broader process of toolkittification in AI ethics: how producing and using toolkits may help designers achieve socially desirable results without the oversimplification of ethical practice that many toolkits embody.

4 Towards a conclusion: after toolkittification

In this article, I have drawn on the meta-critique of the AI ethics toolkit landscape to demonstrate that that the ethico-political assumptions that underpin most endeavors to ‘kittify’ AI ethics also limit the resulting toolkits’ potential for facilitating change in how new technologies are conceived, developed, and deployed. These limitations, as I have argued, are tied to several categories of suggestions on how to improve toolkits put forward by AI ethics researchers. The meta-critique of the toolkit landscape reveals that toolkit makers are urged to address the foundational ‘deficiencies’ of existing toolkits by incorporating ‘alternative’ ethical and epistemological frameworks, such as feminist ethics or indigenous epistemologies. It emphasizes that toolkits should reflect, rather than simplify, the full complexity of the process of identifying and addressing ethical challenges in design, while still providing structure to this process. It also advocates for toolkits that encourage the participation of a wider array of stakeholders, enabling them to articulate their needs and demand change in how technologies are developed and adopted. Finally, the meta-critique also points to the need for reframing responsible technology design as a matter of collective action–the need for reinscribing politics into the ethics of AI.

These suggestions would certainly resonate with many critical design theorists and practitioners. This is because the limitations of AI ethics toolkits identified in the meta-critique might relate not to the challenges of translating the theory of ethics into AI development practice specifically, but to the pitfalls of toolkittifcation as a means of reforming design generally: a form of myopia that toolkittifcation embodies. Precisely in response to this critical view of toolkittification, Ansari has argued that we do not need toolkits ‘nor their “universal” definitions of design thinking or their processes’ but rather ‘new, diverse philosophies and frameworks that are tied to local knowledge and practice, informed by local politics and ethics’ [3, p. 428]. In Ansari’s understanding, design toolkits reaffirm the ethico-political assumptions underlying dominant design paradigms instead of challenging them; the organizing logic they represent and enforce is that of scale and repetition and thus also of erasure–erasure of practices that are not suitable for scaling up, that are situated, deeply contextual. In her essay on design toolkits, media theorist Shannon Mattern echoes this, paraphrasing the work of Audre Lorde, saying that ‘tools forged through a particular politics […] might not be able to undermine that political regime’ [23, non pag.]. In this framing, a toolkit as a means of structuring design activities incorporates the universalizing principles of the Western modernist tradition–a tradition that critical design scholars, as mentioned earlier, aim to depart from; toolkits foreclose certain modes of resistance to development and production because they reflect a worldview that sees technological advancement as inevitable, while disregarding modes of being and knowing that do not ‘lend themselves to standardization, measurement, and “kittification”’ [23].

Without questioning the underlying ethico-politics of design toolkits (whether for AI or any other application area) their creators are bound to repeat the mistakes that critical design theorists and practitioners have been warning against ever since toolkits, that initially emerged as frameworks for ‘bringing more self-reflexivity and rigor into designers’ own processes’ out of the design methods movement of the 1960s, evolved into ‘formulaic, self-contained packages’ [3, p. 419] that they are now. However, the historical trajectory of design toolkits that Ansari is referring to also indicates that the belief in the toolkit as a means of facilitating change in design might not be entirely misguided. Indeed, Mattern argues that precisely in the context of rapid technological change and in contrast ‘with the machines automatically harvesting mountains of data,’ some design toolkits may allow for ‘a slower, more intentional, reflective, site-specific, embodied means of engaging with research sites and subjects’ [23]. I expanded the ‘landscape’ of AI ethics toolkits in my discussion to include the ‘alternative’ toolkits–toolkits overlooked by other ‘toolkit-scoping’ and ‘toolkit-collecting’ projects–to demonstrate what they do differently to enable the kind of practice that Mattern suggests is still possible. Rather than facilitate the translation of ‘theory’ into ‘practice,’ these toolkits help translate between people, between different stakeholder groups and epistemic communities–they strive to stage power-sensitive conversations and allow for engaging tension. Instead of encouraging inclusion measured against visible markers of ‘diversity,’ they prioritize participation as justice. They foreground ethics work as continuous, perpetually ‘in progress,’ rather than a finite list of issues to be resolved. The result of this analysis is, therefore, not so much a set of clear-cut recommendations for future makers and users of AI ethics toolkits or an ‘endorsement’ of the selected ‘alternative’ toolkits, as a renewed sense of orientation: from toolkittification as automation, delegation, and simplification of ethics work in design, towards toolkittification as a meta-ethics of design.

This is also to emphasize that my critical interrogation of ‘toolkittfication’ is not a call to abandon toolkits but rather to explore and acknowledge both the affordances and limitations of the modes of acting (and knowing) that toolkits, in their multiplicity, enable and enforce. While specific types of tools–be they ideational, educational, procedural, or technical–can help address particular aspects of broader challenges related to responsible technology development, it is essential to make visible what is lost in ‘translation,’ what gets obfuscated when toolkits are embraced as the primary response to the demands of AI ethics, understood broadly as both a research and regulatory space. The European Union’s newly adopted AI Act mandates that developers assess the impact of their AI systems on fundamental rights and values, such as dignity, in high-risk areas of application like recruitment and public services. This is no easy feat, and we can expect new guidelines and toolkits to multiply to make compliance with new regulation more easily executable. Thinking critically about AI ethics through ‘toolkittification’ will help ensure that these efforts, while much needed, do not lend themselves to a checklist mentality and oversimplification of the ethics work discussed in this article.

Indeed, my critique of the AI ethics toolkits landscape was conducted concurrently with a practice-oriented project that aimed to develop precisely such a toolkit: intended to help development teams not only comply with the AI Act but also adopt a pro-justice approach to design–an approach that informs the ‘alternative’ toolkits analyzed in this article. While a discussion of how the approach to toolkittification as a meta-ethics of design has influenced the development of a specific toolkit (and what compromises have been made in the process) is beyond the scope of this paper–and will be addressed elsewhere–the hope is that the scaffolding proposed here, which helped our team test the limits of the toolkit format, will also help others consider what should become of AI ethics work after toolkittification.

Data availability

Not applicable.

Reference

Amoore, L.: Cloud Ethics: Algorithms and the Attributes of Ourselves and Others. Duke University Press, Durham (2020)

Ansari, A.: Decolonizing design through the perspectives of cosmological others: arguing for an ontological turn in design research and practice. XRDS 26, 2 (2019)

Ansari, A.: Global Methods, Local Designs. In: Resnick, E. (ed.) Social Design Reader. London, Bloomsbury (2019)

Attard-Frost, B., Delos Ríos, A., Walters, D.R.: The ethics of AI business practices: a review of 47 AI ethics guidelines. AI Ethics 3, 389–406 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43681-022-00156-6

Ayling, J., Chapman, A.: Putting AI ethics to work: are the tools fit for purpose? AI Ethics 2, 405–429 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43681-021-00084-x

Birhane, A.: Algorithmic injustice: a relational ethics approach. Patterns (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patter.2021.100205

Ciston, S.: Intersectional AI is essential: polyvocal, multimodal, experimental methods to save artificial intelligence. J. Sci. Technol. Arts. 11(2), 3–8 (2019). https://doi.org/10.7559/citarj.v11i2.665

Costanza-Chock, S.: Design Justice: Community-Led Practices to Build the Worlds We Need. MA, and London, MIT Press, Cambridge (2020)

Dignum, V.: Relational Artificial Intelligence, arXiv:2202.07446. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2202.07446 (2022). Accessed 04/02/2022

Escobar, A.: Designs for the Pluriverse: Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds. Duke University Press, Durham and London (2018)

Fjeld, J., Achten, N., Hilligoss, H., Nagy, A., and Srikumar, M.: Principled Artificial Intelligence: Mapping Consensus in Ethical and Rights-Based Approaches to Principles for AI Berkman Klein Center Research Publication (2020). https://ssrn.com/abstract=3518482

Greene, D., Hoffmann, A.L., & Stark, L.: Better, Nicer, Clearer, Fairer: A Critical Assessment of the Movement for Ethical Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning. Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (2019)

Hagendorff, T.: The ethics of AI ethics: an evaluation of guidelines. Mind. Mach. 30, 99–120 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11023-020-09517-8

Haraway, D.: Situated Knowledges: the science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective. Fem. Stud. 14(3), 575–599 (1988). https://doi.org/10.2307/3178066

Hollanek, T., & Ganesh, M. I.: ‘Easy wins and low hanging fruit.’ Blueprints, toolkits, and playbooks to advance diversity and inclusion in AI. In: Neves, J. and Steinberg, M. (eds.), In/Convenience: Inhabiting the Logistical Surround.. Amsterdam, Institute of Network Cultures (2024)

Holstein, K, Wortman Vaughan, J., Daumé, H., Dudik, M. and Wallach, H.: Improving Fairness in Machine Learning Systems: What Do Industry Practitioners Need? In Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI '19). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, Paper 600, 1–16 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1145/3290605.3300830

Intersectional AI Toolkit. https://intersectionalai.miraheze.org/wiki/Intersectional_AI_Toolkit (2024). Accessed 20/02/24

Intersectional Design Cards. https://intersectionaldesign.com (2024). Accessed 20/02/24

Jobin, A., Ienca, M., Vayena, E.: The global landscape of AI ethics guidelines. Nat Mach Intell 1, 389–399 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-019-0088-2

Kluge Corrêa, N., Galvão, C., Santos, J.W., Del Pino, C., Pontes Pinto, E., Barbosa, C., Massmann, D., Mambrini, R., Galvão, L., Terem, E., de Oliveira, N.: Worldwide AI ethics: a review of 200 guidelines and recommendations for AI governance. Patterns (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patter.2023.100857

Lee, M. S. A. and Singh, J.: The Landscape and Gaps in Open Source Fairness Toolkits. In Proceedings of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI '21). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, Article 699, 1–13 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1145/3411764.3445261

Madaio, M. A., Stark, L., Wortman Vaughan, J., and Wallach, H.: Co-Designing Checklists to Understand Organizational Challenges and Opportunities around Fairness in AI. In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI '20). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 1–14 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1145/3313831.3376445

Mattern, S.: Unboxing the Toolkit. Toolshed, https://tool-shed.org/unboxing-the-toolkit/ (2021). Accessed 10/10/23

Morley, J., Floridi, L., Kinsey, L., et al.: From what to how: an initial review of publicly available AI ethics tools, methods and research to translate principles into practices. Sci. Eng. Ethics 26, 2141–2168 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-019-00165-5

Notmy.ai Toolkit. https://notmy.ai/news/algorithmic-emancipation-building-a-feminist-toolkit-to-question-a-i-systems/ (2024). Accessed 20/02/24

OECD. Catalogue of Tools & Metrics for Trustworthy AI. https://oecd.ai/en/catalogue/overview (2023). Accessed: 20/02/24

Oracle for Transfeminist Technologies. https://www.transfeministech.codingrights.org (2024). Accessed 20/02/24

Peters, D., Loke, L., Ahmadpour, N.: Toolkits, cards and games – a review of analogue tools for collaborative ideation. CoDesign 17(4), 410–434 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2020.1715444

Petterson, A., Cheng, K., and Chandra, P.: Playing with Power Tools: Design Toolkits and the Framing of Equity. In Proceedings of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI '23). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, Article 392, 1–24 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1145/3544548.3581490

Prem, E.: From ethical AI frameworks to tools: a review of approaches. AI Ethics 3, 699–716 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43681-023-00258-9

Qiang, V., Rhim, J., Moon, A.: No such thing as one-size-fits-all in AI ethics frameworks: a comparative case study. AI & Soc. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-023-01653-w

Richardson, B. Garcia-Gathright, J., Way, S.F., Thom, J., and Cramer, H.: Towards Fairness in Practice: A Practitioner-Oriented Rubric for Evaluating Fair ML Toolkits. In Proceedings of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI '21). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, Article 236, 1–13 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1145/3411764.3445604

Sloane, M., Moss, E, Awomolo, O., and Forlano, L. Participation Is not a Design Fix for Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the 2nd ACM Conference on Equity and Access in Algorithms, Mechanisms, and Optimization (EAAMO '22). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, Article 1, 1–6 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1145/3551624.3555285

Varon, J. and Peña, P.: Building a Feminist toolkit to question A.I. systems, Notmy.ai (2021). Accessed 20/02/24

Wong, R. Y., Madaio, M A. and Merrill, N. Seeing Like a Toolkit: How Toolkits Envision the Work of AI Ethics. Proc. ACM Hum.-Comput. Interact. 7, CSCW1 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1145/3579621

Funding

This work was funded by the Stiftung Mercator GmbH grant no. 200446.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interests

No competing interests to declare.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hollanek, T. The ethico-politics of design toolkits: responsible AI tools, from big tech guidelines to feminist ideation cards. AI Ethics (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43681-024-00545-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43681-024-00545-z