Abstract

Purpose

Although EPA assessment tools generally allow for narrative feedback, limited data exist defining characteristics and predictors of such feedback. We explored narrative feedback characteristics and their associations with entrustment, case-specific variables, and faculty/trainee characteristics.

Methods

Our general surgery residency piloted an intraoperative Entrustable Professional Activities (EPA) assessment tool in 2022. The tool included an entrustment score, four sub-scores, and narrative feedback. Given strong intercorrelations (r = 0.45–0.69) and high reliability (α = 0.84) between sub-scores, we summed the four sub-scores into a composite score. We coded narrative feedback for valence (reinforcing vs constructive), specificity (specific vs general), appreciation (recognizing or rewarding trainee), coaching (offering a better way to do something), and evaluation (assessing against set of standards). Multivariable regression analyzed associations between feedback characteristics and entrustment score, composite score, PGY level, case difficulty, trainee/faculty gender, gender matching, faculty years in practice, faculty case volume with trainees, faculty evaluation score, and trainees’ under-represented in medicine (URiM) status.

Results

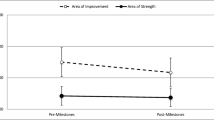

Forty-six faculty completed 325 intraoperative EPA assessments for 44 trainees. Narrative feedback had high valence (82%) and specificity (80%). Comments frequently contained appreciation (89%); coaching (51%) and evaluation (38%) were less common. We found that faculty gender, trainee gender, and gender match predicted feedback characteristics. Generally, entrustment level, composite score, and PGY level correlated with feedback types (Table).

Conclusion

Entrustment and performance relate to the type of feedback received. Gender and gender match resulted in different types of feedback. Evaluative feedback was the least prevalent and warrants further exploration since evaluation is critical for learning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In July of 2023, the American Board of Surgery (ABS) officially announced the transition to a competency-based resident education (CBRE) model, introducing 18 core General Surgery Entrustable Professional Activities (EPAs) [1]. Competency-based surgical education is an educational paradigm that emphasizes residents demonstrating the competencies needed for effective performance in their roles before advancing to the next phase of training [2]. A challenge of CBRE is how to operationalize competency assessment in everyday activities or on performance assessments.

To address this challenge, the ABS has encouraged the use of EPAs as the focus for clinical assessment tools. EPAs were first proposed by Dr. Ten Cate in 2005 and are defined as “a unit of professional practice that can be fully entrusted to a resident, once he or she has demonstrated the necessary competence to execute this activity unsupervised” [3, 4]. Given the transition to CBRE with EPAs, general surgery programs across the country have started implementing EPAs as the focus of their clinical assessment tool.

Most assessment forms contain a narrative feedback section, inviting individualized feedback for the resident. Narrative feedback poses an opportunity to describe performance, provide individualized recommendations, or compare their performance to a set of standards [5]. Narrative feedback can indicate struggling residents and thus provides an opportunity for early intervention and support [6, 7]. Prior studies analyzing narrative feedback, not specific to EPAs, advocate for feedback that incorporates reinforcement or correction, is highly specific, includes examples, or offers actionable suggestions [8, 9].

When analyzing narrative feedback on EPA assessments, prior studies have utilized the Quality of Assessment for Learning (QuAL) as the solitary scoring system to analyze the content and quality of feedback [10, 11]. The QuAL scoring system focuses on identifying if feedback contains evidence, suggestions, or a connection between the two. There is an opportunity for further characterization of narrative feedback given the limited number of feedback principles previously analyzed on EPA assessments [12]. Better understanding the nuances of narrative comments on EPA assessments may help guide faculty development efforts around more effective feedback to facilitate resident growth. Therefore, we aim to identify narrative feedback characteristics on an operative EPA assessment in general surgery and to determine if resident performance, entrustment, or resident/faculty characteristics impact the type of narrative feedback received.

Methods

Study setting and design

We performed a retrospective directed content analysis of narrative feedback on operative EPA assessments at a single large academic teaching hospital system, the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Medical Center. We included assessments completed between June 2022 through July 2023. Faculty were instructed to complete the operative EPA assessment following each operation with a surgical resident. The participants were surgical residents rotating on a general surgery service.

EPA assessment tool

The general surgery program leadership in May 2022 developed an assessment tool for use with intraoperative EPAs. The assessment tool collects demographic information such as resident name, faculty name, and resident postgraduate training level (PGY). Case-specific data such as procedure type and case difficulty (straightforward, moderate, complex) are also collected. There was a total entrustment score that utilized the entrustment supervision (ES) scale recommended by the ABS, ranging from limited participation (1), direct supervision (2), indirect supervision (3), to practice ready (4) [1, 13]. We also included four domains to assess resident performance: Knowledge of Anatomy (1–3), Surgical Technique (1–4), Recognition of Potential Errors (1–4), and Steps of the Operation (1–4). The four domains of resident performance were developed from narratives of the five EPAs on the ABS pilot study, as well as with the expertise of the general surgery program leadership team [13]. The four sub-scores were summed to form a composite score given strong intercorrelations (r = 0.45–0.69) and reliability (α = 0.84) between the domains. The final section of the EPA assessment tool included a required field for narrative feedback.

Additional data collection

Resident and faculty characteristics such as faculty years in practice, faculty/resident self-reported gender, and resident’s Underrepresented in Medicine status (URiM) were collected from the records in the surgical education office. To identify faculty members who most frequently operate with residents, we utilized the ACGME case log data. Finally, we determined the faculty member’s skills as an educator by averaging all resident ratings for the faculty member for the item “providing formative feedback” on the faculty teaching evaluations (where 1 equals ineffective skill and 4 equals exemplary skill).

Feedback characteristics selection

Feedback characteristics included in the study were valence, specificity, appreciation, coaching, and evaluation. We selected characteristics based on prior literature and expertise from the surgical education leadership team [9, 14,15,16,17,18]. High valence feedback was characterized as reinforcing, whereas low valence was corrective. Specificity is defined as specific or general. Appreciation refers to feedback that recognized or rewarded the resident. Feedback with coaching offers a better way to perform a task. Finally, evaluation was defined by feedback that assessed residents against a set of standards.

Data analysis

After data collection, all EPA assessments were de-identified to ensure anonymity of the residents. Two researchers (AM, AG) performed directed content analysis of the narrative feedback from the EPA assessments. Valence and specificity were coded dichotomously. For valence, the feedback was scored as reinforcing or corrective (0 = corrective). For specificity, the feedback was scored as specific or general (0 = general). Appreciation, coaching, and evaluation were coded on a 3-point scale (1 = Not Present, 2 = Somewhat, 3 = Yes). We calculated inter-rater reliability using Cohen’s kappa. In the event of a disagreement between the two researchers performing the content analysis, a third researcher (RB) would analyze the feedback and provide a final decision.

Multivariable logistic regression assessed for associations between feedback characteristics and entrustment score, composite score, PGY level (1–5), case difficulty (1–3), gender of resident and faculty (0 = male), gender matching (1 = alignment), faculty years in practice, resident’s under-represented in medicine (URiM) status (0 = non-URiM), faculty evaluation scores, and number of operative cases with a resident. For appreciation, coaching and evaluation, we converted the 3-point scale to a dichotomous item (0 = not present, 1 = present) to perform logistic regression. All independent variables were standardized to allow direct comparisons across predictors. We performed all analyses in Stata 16.1 for Mac (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Ethical approval

The University of California, San Francisco institutional review board exempted this study from review (IRB 23-39,766).

Results

Descriptive results

From June 2022 to July 2023, faculty members completed 325 assessments for 44 residents. Of these residents, 57% were female (n = 25) and 30% URiM (n = 13). The study included residents from all PGY levels, with a nearly equal distribution across each class (10 PGY1, 9 PGY2, 8 PGY3, 8 PGY4, 9 PGY5). Forty-two faculty from 10 surgical subspecialities completed evaluations. Faculty had an average of 14 years in practice (range: 1–37) and 45% were female (n = 20). On average the faculty operated 133 times with a resident (13–263 cases) in one year. The average teaching evaluation score of the faculty based on the resident-completed performance evaluations was 3.81 ± 0.17. Of the 325 cases included in the study, faculty rated 132 cases as straightforward, 117 cases as moderate, and 76 cases as complex. Average overall entrustment score was 2.51 ± 0.80 and the average composite score was 12.67 (range: 4–18).

In terms of the feedback characteristics, we found 82% of narrative feedback was reinforcing (18% corrective) and 80% was specific (20% general). 89% of feedback contained appreciation, 51% contained coaching, and only 38% contained evaluation (Table 1). Inter-rater reliability was 91% (kappa = 0.84).

Multivariable regression

We standardized the coefficients and performed logistic regression between each of the feedback characteristics and the predictors (Table 2). We found all feedback characteristics contained statistically significant predictors.

Reinforcing feedback, or feedback with high valence, was more prevalent after complex cases (ß = 0.50, 95% CI [0.04, 0.95], p = 0.03). Residents who scored higher on the composite resident performance score were also more likely to receive reinforcing feedback (ß = 0.11, 95% CI [0.25, 0.68], p < 0.01). Feedback was more likely to be corrective for senior level residents (ß = − 0.44, 95% CI [− 0.79, − 0.09], p = 0.02) or when the assessment was completed by a male faculty (ß = − 1.03, 95% CI [− 1.88, − 0.18], p = 0.02).

Both faculty and resident characteristics were statistically significant predictors of specific feedback. Faculty characteristics that predicted more specific feedback included: faculty years in practice, with junior faculty providing more specific feedback (ß = − 0.06, 95% CI [− 0.11, − 0.02], p = 0.01) and faculty with higher evaluation scores (ß = 1.29, 95% CI [1.97, 7.03], p < 0.01). Resident characteristics that predicted specific feedback include increasing PGY level (ß = 0.18, 95% CI [0.25, 0.97], p < 0.01) and resident with lower ES scores (ß = − 0.67, 95% CI [− 1.24, − 0.10], p = 0.02).

Feedback was more likely to contain appreciation when residents scored higher on the composite score of the resident performance domains (ß = 0.47, 95% CI [0.22, 0.73], p < 0.01). Faculty gender was also a significant predictor of appreciative feedback, with male faculty more likely to provide appreciation than their female counterparts (ß = − 1.46, 95% CI [− 2.48, − 0.43], p = 0.01).

Feedback contained coaching when residents received lower ES scores (ß = − 1.01, 95% CI [− 1.52, − 0.49], p < 0.01) and composite scores (ß = − 0.20, 95% CI [− 0.37, − 0.03], p = 0.02). Senior level residents received more coaching as compared to junior level residents (ß = 0.32, 95% CI [0.04 to 0.60], p = 0.03). Both resident and faculty gender played a role in delivery of coaching. Female residents were more likely to receive coaching as compared to male residents (ß = 0.65, 95% CI [0.04, 1.25], p = 0.04) and coaching was more prevalent when there was a match between faculty and resident gender (ß = 0.62, 95% CI [0.03, 1.21], p = 0.04). Faculty characteristics that increased the prevalence of coaching feedback include faculty years in practice with junior faculty providing more coaching (ß = -0.05, 95% CI [− 0.09, − 0.01], p = 0.01) and faculty with higher evaluation scores (ß = 3.32, 95% CI [1.33, 5.32], p < 0.01).

Evaluation was the least prevalent type of feedback received and the only predictors were faculty characteristics. Male faculty were more likely to provide evaluation than their female counterparts (ß = − 1.00, 95% CI [− 1.68, − 0.32], p < 0.01). Faculty with lower evaluation scores were also more likely to include resident evaluation against standards in their narrative feedback (ß = − 3.84, 95% CI [− 5.76 to − 1.93], p < 0.01).

Discussion

We performed retrospective directed content analysis to determine the prevalence and predictors of feedback characteristics in narrative feedback provided on an operative EPA assessment tool. We determined that most of the feedback was reinforcing, specific, and contained appreciation. Coaching, defined as providing a recommendation, was less common with prevalence around 50%. Less than half of the narrative feedback contained evaluation, or compared residents against a set of standards, making it the rarest type of feedback provided. It is reassuring faculty frequently included reinforcing feedback, as positive feedback has been shown to improve resident performance, confidence, and motivation [14, 19]. The relative lack of coaching and evaluation feedback is consistent with prior studies demonstrating a lack of recommendations or suggestions in narrative feedback [10, 11, 20]. Both coaching and evaluation are essential for resident education and progression. Therefore, there is an opportunity to improve future feedback quality by highlighting this deficiency and providing recommendations for faculty development.

Few studies have looked at the narrative feedback on EPA assessments (10, 11). Therefore, it remains unknown how feedback characteristics vary following questions regarding entrustment. Ideally the narrative feedback section would provide the opportunity to explain or defend the overall entrustment and resident performance scores. Our study demonstrated the average ES score was 2.51 out of 4 and the overall composite score was 12.67 out of 18; however less than 50% of feedback contained coaching or evaluation against standards. Therefore, there is a missed opportunity to explain the suboptimal ES score and composite scores within the narrative feedback as most feedback was reinforcing and appreciative. Incorporating actionable recommendations or benchmarking residents against established standards would allow residents to better understand their scores and areas for improvement. With ongoing implementation of assessments of EPAs, faculty development might provide guidance on delivering narrative feedback that includes justification for their score selections.

The multivariable regression revealed multiple interesting predictors of feedback characteristics including both resident entrustment, performance, and case factors, but also resident/faculty characteristics. Residents with lower overall ES scores received more specific feedback and coaching, which is consistent with what residents need and desire. The composite score, composed of resident performance scores such as technical skills, recognition of potential errors, steps of the operation, and anatomy knowledge, was the most common predictor of feedback characteristics. As expected, residents with higher composite scores received more appreciation and reinforcing feedback. Residents with lower composite scores received more specific feedback and coaching. These findings suggest that the type of feedback provided corresponded to resident performance, reinforcing strong performance and correcting areas of weakness.

Another resident factor that predicted type of feedback delivered was PGY level. Junior level residents received more reinforcement, while senior level residents received more specific feedback and coaching. This finding may suggest a desire to provide a positive and supportive environment for junior-level residents, while providing more directed feedback with recommendations for improvement to senior-level residents prior to graduation. In addition, senior residents may have an established relationship with the faculty that allows for more directed feedback. Finally, case difficulty also resulted in more reinforcing feedback, potentially signifying faculty offering support to residents through complex and difficult cases.

We found both resident and faculty gender to be significant predictors for feedback characteristics. An almost equal number of male and female faculty completed the EPA assessments and provided narrative feedback. However, male faculty were more likely to deliver reinforcing, appreciative, or evaluative feedback than their female counterparts. Resident gender also impacted feedback characteristics, with female residents being more likely than male residents to receive coaching. Gender match between the resident and faculty also resulted in more coaching feedback. These results suggest there is a potential effect of gender on the characteristics of feedback delivered. This is consistent with prior studies demonstrating an impact of gender on decisions of entrustment and autonomy [21,22,23]. Future studies should investigate the causality of gender differences given its persistence in surgical education and EPA assessment literature.

Faculty characteristics, such as years in practice and evaluation score, were also significant predictors of feedback characteristics. Junior faculty and faculty with higher evaluation scores were more likely to provide specific feedback and coaching. Interestingly, faculty with lower evaluation scores were more likely to provide evaluation feedback or compare the residents against a set of standards. Interestingly, the volume of operations with a resident was not a significant predictor. This variable was selected as a potential surrogate of identifying a relationship between faculty and residents with the assumption that higher case volumes indicate increased familiarity with residents. The sample size was insufficient to look at direct pairings between faculty and residents to understand the impact of familiarity, which represents a potential focus for future studies.

There are several limitations within our study that moderate our findings. We selected five feedback characteristics based on the literature and expertise of our leadership team; however, this is not an exhaustive list. There are likely other feedback characteristics and scoring systems that could provide additional insight into the types of narrative feedback provided. Another limitation is that this study was conducted during the first year of implementation of EPAs at our institution. Therefore, there was varying levels of completion of the assessment forms across surgical subspecialities and individual faculty. Therefore, the results are not equally representative across surgical divisions and faculty. As well, the narrative feedback section of this EPA assessment tool, while on other assessment tools it is optional. This could influence the type of narrative feedback delivered, as optional feedback might be chosen only when faculty has strong opinions. Finally, we conducted this study at a single large academic medical center; findings most likely apply to similar institutions.

Overall, we identified different feedback characteristics and their predictors including resident entrustment, performance, case factors, and resident/faculty characteristics. Our findings highlight potential areas for faculty development to improve the quality of narrative feedback provided on EPA assessment tools. As well, we identified future areas of study such as the role of gender and the faculty/resident relationship on feedback characteristics.

Data availability

Raw data were generated at University of San Francisco. Derived data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author (ADM) on request.

References

Retrieved 04/19/2024 from American board of surgery, entrustable professional activities (EPAs): https://www.absurgery.org/get-certified/epas/

Lindeman B, Sarosi GA. Competency-based resident education: the United States perspective. Surgery. 2020;167(5):777–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2019.05.059.

Ten Cate O. Entrustability of professional activities and competency-based training. Med Educ. 2005;39(12):1176–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02341.x.

Ten Cate O, Taylor DR. The recommended description of an entrustable professional activity: AMEE Guide No 140. Med Teac. 2021;43(10):1106–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2020.1838465.

Chakroun M, Dion VR, Ouellet K, Graillon A, Désilets V, Xhignesse M, St-Onge C. Narrative assessments in higher education: a scoping review to identify evidence-based quality indicators. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2022;97(11):1699–706. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000004755.

Ginsburg S, van der Vleuten CPM, Eva KW. The hidden value of narrative comments for assessment: a quantitative reliability analysis of qualitative data. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2017;92(11):1617–21. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001669.

Kelleher M, Kinnear B, Sall DR, Weber DE, DeCoursey B, Nelson J, Klein M, Warm EJ, Schumacher DJ. Warnings in early narrative assessment that might predict performance in residency: signal from an internal medicine residency program. Perspect Med Educ. 2021;10(6):334–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-021-00681-w.

Bockrath R, Wright K, Uchida T, Petrie C, Ryan ER. Feedback quality in an aligned teacher-training program. Fam Med. 2020;52(5):346–51.

Solano QP, Hayward L, Chopra Z, et al. Natural language processing and assessment of resident feedback quality. J Surg Educ. 2021;78(6):e72–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2021.05.012.

Leclair R, Ho JSS, Braund H, et al. Exploring the quality of narrative feedback provided to residents during ambulatory patient care in medicine and surgery. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1177/23821205231175734.

Fernandes RD, de Vries I, McEwen L, Mann S, Phillips T, Zevin B. Evaluating the quality of narrative feedback for entrustable professional activities in a surgery residency program. Ann Surg. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000006308.

Burgess A, van Diggele C, Roberts C, Mellis C. Feedback in the clinical setting. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(2):460. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02280-5.

Brasel KJ, Lindeman B, Jones A, et al. Implementation of entrustable professional activities in general surgery: results of a national pilot study. Ann Surg. 2023;278(4):578–86. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000005991.

Kannappan A, Yip DT, Lodhia NA, Morton J, Lau JN. The effect of positive and negative verbal feedback on surgical skills performance and motivation. J Surg Educ. 2012;69(6):798–801. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2012.05.012.

Young JQ, Sugarman R, Holmboe E, O’Sullivan PS. Advancing our understanding of narrative comments generated by direct observation tools: lessons from the psychopharmacotherapy-structured clinical observation. J Grad Med Educ. 2019;11(5):570–9. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-19-00207.1.

Kruidering-Hall M, O’Sullivan PS, Chou CL. Teaching feedback to first-year medical students: long-term skill retention and accuracy of student self-assessment. J Gen Int Med. 2009;24(6):721–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-009-0983-z.

Stone D, & Heen S (2015). Thanks for the feedback. Portfolio Penguin.

Fisher R, Sharp A, & Richardson J (1999). Getting it done: How to lead when you’re not in charge. HarperBusiness.

Kamali D, Illing J. How can positive and negative trainer feedback in the operating theatre impact a surgical trainee’s confidence and well-being: a qualitative study in the north of England. BMJ Open. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017935.

Marcotte L, Egan R, Soleas E, Dalgarno N, Norris M, Smith C. Assessing the quality of feedback to general internal medicine residents in a competency-based environment. Can Med Educ J. 2019;10(4):e32–47.

Meyerson SL, Odell DD, Zwischenberger JB, et al. The effect of gender on operative autonomy in general surgery residents. Surgery. 2019;166(5):738–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2019.06.006.

Padilla EP, Stahl CC, Jung SA, et al. Gender differences in entrustable professional activity evaluations of general surgery residents. Ann Surg. 2022;275(2):222–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000004905.

Sandhu G, Thompson-Burdine J, Nikolian VC, et al. Association of faculty entrustment with resident autonomy in the operating room. JAMA Surg. 2018;153(6):518–24. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2017.6117.

Acknowledgements

The authors received funding for this project through a University of California San Francisco Innovations Funding for Education 2024 Grant. We would like to thank both the faculty and residents who participated in this study for their time and dedication to the implementation of EPAs in the surgical residency program. Finally, we would like to thank the Association for Surgical Education for the opportunity to present our work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Alyssa D. Murillo and Riley Brian participate in the Intuitive-UCSF Simulation-Based Surgical Education Research Fellowship. Camilla Gomes participates in a research fellowship through Johnson and Johnson.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Murillo, A.D., Gozali, A., Brian, R. et al. Characterizing narrative feedback and predictors of feedback content on an entrustable professional activity (EPA) assessment tool. Global Surg Educ 3, 91 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44186-024-00281-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44186-024-00281-2