Abstract

Objectives

Chronic pain in children and adolescents is often associated with functional, physical, and psychosocial challenges. Intensive interdisciplinary pain treatment (IIPT) programs are effective at helping these youth regain functioning, but little is known about their perspectives prior to and during IIPT participation. This study sought to better understand how children and adolescents experience the process from evaluation to completion of the IIPT program.

Methods

Individual interviews (n = 7) were conducted at three time-points; (1) prior to initial evaluation in a pain clinic, (2) after pain clinic evaluation while considering IIPT, and (3) after completion of an IIPT program.

Results

Participants ranged in age from 13–17 years. Across these time points, participants demonstrated changes in thoughts and perspectives. While Time 1 was associated with ambivalence, skepticism, and some hope, Time 2 was characterized by processing information about the program and resolution of some of their ambivalence. At Time 3, participants described their experience as “challenging” and “intense” and reported recognition that they had benefited from the program. Participants also wished to pass along lessons learned to future potential patients.

Discussion

This study provides information to help clinicians better approach adolescents with chronic pain who may be considering IIPT.

Keypoints

This study, for the first time, characterizes patient experiences as they navigate entry to, beginning, and completion of an intensive interdisciplinary pain treatment program. It highlights adolescents’ thought processes as they weigh whether to engage in and ultimately complete the program, providing insight on changes in their thinking over time.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Approximately 20–35% of children and adolescents experience chronic pain which persists for more than three months [1,2,3]. Chronic pain in young people may present as chronic or recurrent headache, abdominal pain, and localized or widespread musculoskeletal pain [4]. Longer duration of chronic pain is associated with significant functional deficits across multiple modalities, including school, daily activities, and emotional functioning, contributing to poorer quality of life [4,5,6], with 5–8% of youth reporting severe chronic pain and disability [7].

Previous qualitative studies report a variety of ways that children and adolescents’ social, psychological, and daily functioning are hindered by chronic pain, and the detrimental effects of their experience of diagnostic uncertainty. Carter [8] examined the impact of chronic pain on adolescents through analysis of journal writings and structured interviews and found that chronic pain threatened normalcy and relationship-building. Adolescents also identified “referral fatigue” as the repeated cycle of hope and disappointment when medical providers were unable to provide a medical cause for why they were experiencing pain. Patients also reported feeling isolated and different from peers [9]. In structured interviews, adolescents with chronic pain described challenges, including difficulty sharing symptoms of their illness with others and fear of a loss of identity, as well as barriers to communication including stress levels, clinical status, socioeconomic status, personal and cultural views on pain, and perceived lack of clinician understanding [9].

Intensive interdisciplinary pain treatment (IIPT) programs are effective for helping young people who are impaired by chronic pain regain functioning [10, 11]. These programs provide comprehensive treatment focused on the widespread impacts of chronic pain [4]. This comprehensive treatment integrates physical activity and desensitization (often provided by physical and occupational therapists), psychological therapies such as cognitive behavior therapy and acceptance and commitment therapy (provided by a psychologist or counselor), along with biobehavioral and creative/expressive strategies to regulate stress (often provided by music and art therapists, yoga teachers, and nurses), with careful medical oversight [4, 5]. IIPT may be provided as an inpatient or day hospital program, typically including approximately eight hours of treatment per day over several weeks [6, 7]. Within these programs, participants, their families, and the treatment team collaborate to improve functioning and reengagement in activities such as returning to school and physical activity. Completion of this type of program has been shown to restore physical functioning, improve social and school functioning, improve anxiety and depressive symptoms, and promote improvement in pain intensity [4, 5].

Despite research demonstrating the effectiveness of IIPT programs, little is known about the experiences of children and adolescents with chronic pain as they navigate entry into and completion of an IIPT. It is likely that the thoughts, feelings, and concerns of participants may be different prior to their first appointment in an interdisciplinary pain clinic as compared to after completing an IIPT. Indeed, for youth and families who have typically experienced many treatment attempts without improvement, being recommended for such an active and challenging treatment approach may result in mixed feelings and responses. Understanding how children and adolescents experience the treatment process, from their evaluation prior to an IIPT program to completion of the program, provides knowledge of barriers coming into the program as well as how they respond to the intervention. Insights from participant perspectives may guide how and what information is provided to future potential IIPT patients, to better prepare and inform them prior to IIPT, which may in turn improve their individual treatment outcomes.

2 Methods

2.1 Study design

This study used a longitudinal qualitative descriptive design. Longitudinal qualitative research is a useful method to use when you are exploring change over time [12]. In-depth, semi-structured interviews were conducted at three timepoints: (1) one to two days prior to initial evaluation in the pain clinic, (2) within 2 days following the initial evaluation visit and (3) within 2 weeks of completion of the IIPT program (as applicable).

2.2 Ethics approval and consent to participate

All study procedures were approved by the Children’s Mercy, Kansas City Institutional Review Board of (IRB #14010041). Informed consent was obtained from each participant prior to any study related activities. For individuals less than 18 years of age, informed permission and assent of parent and participant was obtained. The manner in which qualitative data were collected, stored, and analyzed was handled in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations for human subjects related research. No experiments were performed in this study, nor were human tissues or samples collected.

2.3 Participants and sampling approach

Our purposive sample included older school-aged children and adolescents scheduled for evaluation for the Rehabilitation for Amplified Pain (RAPS) program. RAPS is an IIPT that provides 8 h of daily treatment, 5 days a week, lasts 4–6 weeks, and includes a variety of treatment modalities (physical and occupational therapy, psychotherapy, yoga and relaxation training, music therapy, and art therapy). Study eligibility requirements included (a) patient age 9–17 years, (b) fluent English speaker; and (c) no developmental delay that would preclude participation in an interview. All interviews were conducted by the first author in a place of the participant’s choosing (home or other location as desired). All participants were interviewed in one-on-one interviews with no one besides the researcher present.

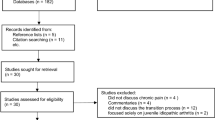

Seven participants enrolled in the study and completed Time 1 and Time 2 interviews. All 7 participants were offered admission to the IIPT, and 4 of the 7 participants then enrolled in the IIPT. Of those, 1 participant dropped out of the treatment program and did not subsequently return study phone calls. The other 3 participants completed the program and the Time 3 interview. The mean age of participants was 15.00 years (range 13–17 years; SD = 1.414) 86% female and 71% white (29% black). These participants reported an average duration of chronic pain of 3.45 years (range of 2–6 years; SD = 1.77). The one male participant (white) and 2 females (1 white and 1 black) did not enroll in the program. Non-starters were similar in age and duration of pain to IIPT participants.

2.4 Procedures

Participants were identified via scheduled appointments in the pain clinic for evaluation of eligibility in the IIPT. Study staff screened families for eligibility and contacted them for potential participation. Parent permission and child assent were obtained prior to the first interview for each participant.

2.5 Analysis

All interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim and checked for accuracy. Interview data were coded individually by timepoint by two of the authors (KS & WRB) using inductive content analysis [13]. Specifically, each coder independently reviewed all transcripts, extracted meaning units from the data and grouped meaning units into categories. After all interviews within each timepoint were coded, categories were compared, modified, and discrepancies resolved through discussion. To increase credibility of results, a third (JC) member of the team read through original transcripts and ensured quotes were well reflected through codes, sub-categories, and categories.

Through this process, 100% agreement was achieved for each timepoint. Then a narrative analysis was developed for each timepoint. When data from all three visits were coded, an overall analysis was conducted to identify and describe the structure of the results across the three visits, allowing for the ability to identify unique categories that were relevant to each visit as well as the overall narrative that unfolded across visits.

3 Results

3.1 Time 1: feeling ambivalence

The first interview occurred within one to two days prior to initial evaluation in the pain clinic. Most participants demonstrated ambivalence, stuck between the status quo (where they at least knew what to expect) and the potential for pain relief. Four categories emerged from Time 1 data including (1) pain is my norm, (2) loss, (3) what helps and what hinders, and (4) searching for relief while doing things anyway.

Pain is my norm Participants reported that having chronic pain was their norm and had been for so long that they could not remember life without it.

“I’ve just always… as long as I remember [had pain]… It’s intensified, of course, but as long as I can remember” (Pt1).

“Even when I was a little, little, little kid, I had really really bad pain in my stomach and they would never figure out what was wrong with me… So I never really know what’s it’s like to not be in pain” (Pt7).

Loss Though these participants had normalized their experience with pain, they were also acutely aware of the limitations it placed on them. This manifested as both exclusion from usual activities and isolation from peers.

“I ended up having to stop doing a lot of sports” (Pt5).

“Missing school, people move, I move. I tried to be a good long-distance friend but there is less and less to talk about” (Pt2).

What helps and what hinders These participants noted behaviors by others that helped them manage as well as behaviors that made the already challenging situation harder. Help at school and teacher/staff understanding of their situation were among the most helpful actions.

“I’ve had really supportive teachers, like one who I never went to her class. She would email me the homework” (Pt5).

Few people understood what they were going through, and this led to experiencing disbelief and invalidation from others.

“None of the people at my school understand, they always say I’m faking my pain” (Pt2).

Doing things anyway Participants detailed things they did to find relief, everything from medication to music with little relief. Many chose to do things anyway, despite the high price they would pay for increased activity.

“It’s sometimes where it’s like if something’s worth it… it’s so much pain, but sometimes you go for it anyway” (Pt5).

Time 1 overview and summary Coming into an appointment for an IIPT program, these participants had experienced chronic pain over an extended period of time. They struggled to engage in “normal” activities, resulting in isolation and lack of understanding from others, who sometimes questioned if their pain was real. Pain had shaped how they perceive their lives: it was so normative to their sense of self that they couldn’t imagine life without it. They had seen many providers and tried many therapies that had not eliminated their pain so they were highly cautious, yet optimistic about the likelihood that this program would help.

“I’m optimistic, but it’s not like I’m going to be disappointed if nothing happens” (Pt1).

3.2 Time 2: processing

The time 2 interview occurred within two days after the initial evaluation. All 7 participants completed Time 2 interviews. Data from the time 2 interviews revealed that this interview functioned in a different way from time 1 (or time 3). The initial intent of the interview had been to explore thoughts and perceptions of the program, but these participants used the interview to process information and their thoughts and emotions regarding potential program participation.

Processing information Participants verbalized understanding how the IIPT program was designed.

“It makes logical sense that it would make me feel better. So that’s obviously a good thing” (Pt6).

“I thought it was good. After hearing everything and getting a better understanding, I think it changed me and my mom's perspective of everything” (Pt7).

They also recognized that the program was a full-time commitment. The time commitment was significant for participants and their families.

“It made me kind of mad because I have to do it over the summer and I had plans and now, I don’t really” (Pt2).

Processing emotions Participants acknowledged mixed feelings about the IIPT program. They received information about the intensity of the program and felt conflicted about whether the effort would be worth it.

“I’m just like whoa busy, you know…It’s more like overwhelmed maybe” (Pt1).

They also wondered if the program would “work” for them.

“Will I get better? That’s probably the one thing that goes through my head” (Pt6).

“It’s like, I don’t really want to do it even though it will help me, that's what they said that it would do, so…I would do it, because I would be at like something at the end, like both, not feeling pain, and like less, supposedly less medicine” (Pt4).

Understanding what would be expected of them left these participants feeling “overwhelmed” (Pt1) and unsure, “afraid of hurting more” (Pt4). Participants noted that “there are no appealing choices” (Pt2) when faced with the choice between continued pain and the emotional, physical, and psychological challenges inherent in program participation.

Program impact and hope Participants generally felt like they needed to participate in the program and recognized the potential impact on their lives.

“Obviously if I am strong enough, I have to do it” (Pt1).

The knowledge that there was something to do for their pain gave participants hope.

“(They) actually explained how it was going to help me get rid of the pain and make it easier. It wasn’t really a cure, but something to really help you” (Pt3).

Processing obstacles and alternatives Some participants perceived barriers, both organizational and personal.

“They only do three people at a time (in the IIPT program), so you have to wait until someone’s graduated and there’s probably a long wait list or something” (Pt5).

Other obstacles included having difficulty accessing materials at home and accessing in-person therapies.

“I can’t like download the relaxing, the CD, that help me relax…I have troubles with that, so I can’t listen to them… and I’m not able to do it (the treatment program) because my mom cannot take time off from work to go and take me… So, we can’t do that” (Pt4).

Participants described the length of the program and certain aspects of the program as potential barriers.

“It’s a not hard choice to do the physical therapy. I would do that… something like that, I would do that all summer. Once, twice a week, I would do that…I could take it for treatment which is for like a week, but three-four weeks?” (Pt2).

“We'll be spending some time in pool and doing, like, yoga. And then exercising. I'm not a pool person” (Pt7).

They also described existing strategies for pain management that they preferred over the ones proposed in the program.

“I'm a bit lazy at points. I have gotten so used to over the last whatever, or just since I had the pain just laying in bed when I'm not feeling good. I keep doing that” (Pt6).

“If I don’t like feel good or something, I usually just go and take a nap… See if that helps… or I get a heating pad” (Pt4).

“I listen to music. I kind of avoid people. Because sometimes people are stressing me out so I just go to my room” (Pt5).

Time 2 overview and summary The second interview gave participants an opportunity to consider their feelings of confusion, hesitation, and ambivalence. They understood the commitment and what would happen in the IIPT program and expressed some hope. At the same time, they identified potential barriers and expressed hesitation to commit without knowing if it would work for them.

3.3 Time 3: moving forward (survive and thrive)

Time 3 interviews came within 2 weeks of participants completing the program. Since this interview occurred after program participation, only three of the 7 participants were interviewed. As noted above, all participants were offered the IIPT program; four enrolled and one dropped out prior to IIPT completion. The 3 remaining participants spoke about their perceptions of it, lessons learned, and words of wisdom for others who might be contemplating participation.

Intense and challenging The program was intense and challenging.

“Probably the hardest thing I have done in my life… It's just been really, really, really challenging” (Pt1).

“(In) the beginning was like they're trying to kill me… it was pretty intense… the workout was intense. Like we're not allowed to sit, we're not allowed to lean against anything, so that was kind of hard on me” (Pt2).

While challenging, participants noticed improvements after the first week or two.

“Well, the first week, it was hard because I was so out of shape and stuff. And the second week it started to get easier but then I started to get pain in more places and the pain was increasing, so that was harder. And then it went pretty smooth. I still had a lot of pain but not as intense, I guess” (Pt7).

When asked if anything could have prepared them for the challenge, one participant noted:

“I don’t know…you kind of just have to be there and do it yourself to understand. ‘Cause for me, the doctor explained as much as she possibly could how hardcore this would be. But it's not really until you’re there and in the moment, where you realize that everything …You instantly want to leave” (Pt7).

Words of wisdom/lessons learned Participants also discussed important lessons they had learned that they wanted to share with future participants. They believed that if they could do it, others could too.

“Well of course they’re going to have a hard time doing it, but it'll get easier” (Pt2).

“It gets a little bit easier, and then the 2 week’s the hardest but, it gets easier after that” (Pt1).

These participants encouraged others to fully commit to the program.

“You should put as much effort into it as you can. If you don’t want to come, and you don’t want to do anything, still come anyway. Because then it’s worse the next day when you do come. Like on the weekends. Mondays are always really hard” (Pt1).

“Don’t just give them goals to help you succeed, give yourself goals … I told myself that, um, my goal basically with myself was no matter my pain, push through it basically. The pain’s gonna be no matter what so it’s just push through it… just give yourself positive thoughts about it” (Pt2).

Ultimately, participants noted benefit as they progressed through the program.

“You’ll start to realize how much it’s helped you and how much you’ve improved as a person. And physically it'll assure you that everything’s gonna be okay” (Pt7).

Participants identified initial resentment for program staff, followed by appreciation for therapists’ ultimate goal to help participants improve.

“Some moments, they [other participants] will not like it. They will feel a lot of dislike towards the people making them do things” (Pt7).

“The best part of the program was the therapists. They, they were harsh, but they were really nice” (Pt2).

“You can always come to them [therapists] whenever you’re feeling all these emotions and stuff and that you can hook on up to them. I guess, knowing that they’re there is easier” (Pt7).

Improved function Participants reported increased confidence and strength.

“Like I can walk upstairs without much trouble… I’m able to sit up straighter and I can get up, like, out of the sitting, like off the couch or out of the chair without really hurting myself. It feels pretty great” (Pt1).

“It feels good to know that my body still works. It definitely worried me a lot” (Pt7).

A few participants specifically noted improved energy and capacity to engage in activities, and decreased pain.

“I'm pretty sure I'm a lot stronger… I feel less tired. I have more energy” (Pt1).

“I've noticed a lot strength-wise how I've improved. So compared to like the first day how I could barely do anything and now I'm doing a lot more” (Pt7).

“When I first went in there, like I was in so much pain. But when I got out, I barely had any pain anywhere, and like I had pain still, but it wasn’t as intense, so like it was kind of fun then, some of the workouts” (Pt2).

They also noted that the pain they experienced had changed.

“It’s just like workout pain, and then I got new pain, and some of the old pain went away… It feels pretty great. My knees don't hurt as much anymore” (Pt1).

Time 3 overview and summary The difficulty and intensity of the IIPT program was a center-point of the conversation. It was also described as effective, and participants acknowledged the challenge plus their own improvement as leading to a desire to pass along knowledge to future participants. This knowledge included encouragement that they could do it, that therapists were helpful (although demanding), and the importance of truly committing to the program.

4 Progression of themes over time

These participants indicated that they came to the pain management clinic with an extended experience with pain. They had become ambivalent because many previous visits to healthcare providers had produced little relief of their pain. They approached this appointment with skepticism tempered with hope. Upon receiving information about the IIPT, these adolescents saw the possibility of improvement but also the intense cost associated with participation.

“(In) the beginning was like they're trying to kill me… it was pretty intense… the workout was intense” (Pt2).

While the study team’s approach to the second interview was not different from the other timepoints, participants used it as a debriefing interview as they processed all the information, considered the costs and benefits, discussed obstacles to participation, and potential next steps. The longitudinal approach allowed participants to consider their previous experience and their future options. Participants who completed the program recognized the change in their pain and functioning while acknowledging the hard work they had done to achieve it.

“You'll start to realize how much it's helped you and how much you've improved as a person. And physically it'll assure you that everything's gonna be okay” (Pt7).

They recognized the need to continue to be active to maintain their improved levels of daily functioning and pain. All participants acknowledged that the program was among the hardest things they had ever done and expressed pride in their accomplishment. They also shared words of wisdom for others who would come after them to complete the program.

“You should put as much effort into it as you can. If you don’t want to come, and you don't want to do anything, still come anyway” (Pt1).

Across the three interviews, early ambivalence gave way to hope for the future that came from learning what to do to manage their pain, and satisfaction in their progress.

5 Discussion

Many studies have evaluated the psychological and psychosocial functioning of pediatric patients with chronic pain, and several studies have quantitatively explored patient reported outcomes after intensive interdisciplinary pain treatment (IIPT) [6, 7]. However, quantitative measures do not capture the nuances of patient experience, such as their thoughts and emotions prior to treatment, and how their impressions change during and after IIPT. This study uniquely followed a small cohort of pediatric patients seen in an outpatient pain clinic in preparation for potential entry into an IIPT program, enabling us to better understand their perceptions before formally being offered the treatment, while waiting for program admission, and after completing intensive treatment. The information shared by these young people provides insight into the evolving thought processes of adolescents experiencing chronic pain and contemplating IIPT.

During their first interview (Time 1), which occurred before their first clinic visit and before they had received diagnosis and treatment recommendations from the IIPT team, participant perspectives were characterized largely by their ambivalence toward treatment, given their previous clinical and treatment interactions, and descriptions of their experiences and attitudes toward pain at that time. Given the unseen or ‘invisible’ nature of chronic pain, pain is often ignored or misattributed to purely a psychological issue [12] and adolescents with chronic pain report experiencing pain-related stigma from school personnel, family members, peers, and even their medical providers [14, 15]. Attitudes diverged somewhat, though, with expressed feelings of loss of activities and life experiences and an accepted new normalcy of living with pain. However, they also expressed continuing to look for relief and ways to manage their pain. At this stage, participants found themselves in a state of tentative optimism and hope. Palermo et al. [16] reported patients having anxious anticipation and hopefulness previous to being seen in a pain clinic for the first time. This “in between” state or straddling has also been found in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis, in which patients reported navigating feelings of hope and fears of disappointment [17]. This has clinical implications, as pediatric patients have endorsed the impact that their medical team and providers have on fostering hope [18]. In the second interview (Time 2), participants clearly utilized this interview as an opportunity to both express and process their own conflicting thoughts about engaging in IIPT. Existing qualitative literature focuses on single timepoint perspectives whereas the use of a longitudinal method allows us to begin to understand how adolescents process information about participation in an IIPT program. This is an area that deserves further investigation.

The use of models of behavioral change provides frameworks for understanding how people think about and make health-related and other behavior changes, as well as the processes that promote and inhibit behavior change. Applying one such model, the Transtheoretical Stages of Change Model, which continues to inform our understanding of behavior change in pediatric pain, Time 1 can be conceptualized as the pre-contemplation or contemplation stage [19,20,21,22].

Participants expressed their experiences with pain at the time of interview, including senses of loss and an accepted reality of pain as the norm, yet also continuing to look for relief, and a commitment to trying to “do things anyway”. Time 2 demonstrates participants navigating a transition between contemplation and preparation. Strategies from Motivational Interviewing have been effective in increasing adolescent adherence and treatment engagement [23] and may be well-suited to help patients in this transition, [24, 25] including an evaluation of their values and ambivalence, evaluating the pros and cons of engaging in pain treatment, and eliciting patients’ expectations and attitudes about pain treatment. In addition to sorting through and talking through the information provided, they also demonstrated an internal tug-of-war as they sorted through benefits contrasted with hesitations and pressures about the program. Some participants also shared their thinking and concerns about specific aspects of the IIPT and their existing preferred strategies, further demonstrating this period of contemplation. By the third interview (Time 3), participants had completed the IIPT and were transitioning from the action phase of the Transtheoretical Model to the maintenance phase. Insights on their experience of being in the program provided some gained retrospection. It is known to the authorship team that the provider team desires to learn from participants to improve and guide how information is provided to future potential IIPT participants. This seems to be a shared value of participants who have completed the program. Of note, participants generally expressed a theme of the program being difficult but ‘worth it’ and wished to share their experiences with those to come after them as both a means of preparing and encouraging them in their journey. Sharing one’s own experience via peer support programs or peer mentorship programs may be a positive experience that solidifies the self-management of their own disease [26] and may be considered as an additional intervention strategy for the maintenance of treatment gains post IIPT.

The results from Time 1 and 2 highlight the difficult history these youth have experienced, as well as the many and creative ways they have learned to accommodate. This has direct implications for how information and education are provided before and during engagement in an IIPT. Direct affirmation of participants’ previous history of seeking help and working to cope may help to resolve some of the pain-related stigma experienced by patients with chronic pain [27]. It is also apparent that while providers are mindful of how and when educational content is provided, this can be improved upon. For example, the results at Time 2 still show some misconceptions about the general approach toward treatment of chronic pain, including an unclear understanding of the differentiation between hurt and harm. Also, given some of the expressed misgivings and hesitancies around the IIPT, there may be benefit to even more directly empowering these young people to take control of this process and choose their treatment. Time 3 provides some insight into potential strategies, such as engaging in peer mentorship of other adolescents either engaged in or preparing to engage in an IIPT. Teach-back strategies have been shown to bolster patient education [28] and are used in IIPT interventions, and other strategies may be useful including greater use of audio-visual media to teach and reinforce content [29].

A unique contribution of the current data is the ability to investigate how thoughts and feelings about IIPT change over the course of that treatment. Across the three interviews, participants demonstrated an evolution in their knowledge about chronic pain and the IIPT, their attitudes toward treatment and management of chronic pain, and showed some persistent skepticism and misunderstanding of pain management. Consistent with existing literature, adolescents demonstrated an acute awareness of factors that inhibit seeking and engaging in positive social support, which affects their ability to cope with pain and pursue more functional activities [30]. Chronic pain places a significant emotional burden on children and adolescent. Higher levels of anxiety are associated with functional impairments, lower satisfaction with health and life, anticipatory anxiety, worry about pain outcomes, and pain catastrophizing [8]. By Time 3, participants that had completed the IIPT reported improvements in both their daily functioning and pain. The longitudinal approach allowed participants to share their temporal situational awareness of their starting point, the experience with IIPT, and the new hope for the future. A strength of this study is that the team members handling the primary analyses of this study (KS, WRB, & JC) were not clinical team members or associated with the pain clinic at the time of data collection. This may have provided a neutral third party for participants to speak to (KS), encouraging greater openness and honesty, while also reducing risk of bias in theme coding by other team members (WB, JC).

6 Limitations

While this study illuminates the experience of adolescents dealing with chronic pain and a rigorous treatment program, several limitations apply. Time 3 included only the 3 participants who completed the program. The participant who started but then dropped out was lost to follow-up, limiting our ability to understand the experiences of patients who withdrew from the program. Future studies could focus on the experiences of those who chose not to participate or did not complete the program in order to better understand what their needs and experiences are. For example, in Time 2, Pt4 and Pt6 expressed several perceived barriers and hesitations to the completion of an IIPT. Though other participants expressed barriers as well, these patients expressed uncertainty about whether the program would “work”. A future mixed-methods design may help explore differences in patient experiences and alignment of qualitative themes with patient reported outcomes and psychosocial factors associated with treatment change, such as readiness to change [31]. The sample size at time 3 was too small to reach convergence of themes so we present themes based upon similar statements that were made by multiple participants; future studies with better power may better allow us to understanding intra-individual barriers and program difficulties that could impact how IIPTs are modified and administered.

Also, while there are a limited number of IIPTs globally, and while they share many treatment characteristics, the patients in this study all completed the same treatment program. As such, it is possible that participants from other programs may have different experiences, highlighting the need for replication of this work in other IIPT samples. Additionally, while this study was designed to capture patient experiences via open-ended questioning, this may be at the cost of treatment and program related specificity. Follow-up studies may explore the ways in which patients would like greater control of their treatment decisions, or specific ways in which they would be interested in engaging in peer mentorship.

7 Conclusions

Intensive interdisciplinary pain treatment is an effective treatment option for many young people with impairment related to chronic pain. At the same time, even considering this kind of approach can be an anxious prospect for a young person whose life has been greatly impacted by pain and who has experienced a number of prior treatments without improvement. These results provide insight on the experience of a small cohort of patients prior to their evaluation for eligibility for IIPT, immediately after that evaluation, and (for a subset of these patients) after completing IIPT treatment. Overall, these results show the uncertainty, fear, hope, strengths, and eventual success of these young people. Exploring the experience through these youths’ words may help the providers directly caring for these youth to empathize with their past experiences, current fears, potential misconceptions, and to provide compassion and hope to families during a stressful time.

Data availability

Data is available upon reasonable request.

References

Goodman JE, McGrath PJ. The epidemiology of pain in children and adolescents: a review. Pain. 1991. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3959(91)90108-A.

King S, Chambers CT, Huguet A, et al. The epidemiology of chronic pain in children and adolescents revisited: a systematic review. Pain. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2011.07.016.

Stanford EA, Chambers CT, Biesanz JC, Chen E. The frequency, trajectories and predictors of adolescent recurrent pain: a population-based approach. Pain. 2008;138:11–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2007.10.032.

Hechler T, Kanstrup M, Lewandowski Holley A. Systematic review on intensive interdisciplinary pain treatment of children with chronic pain. Pediatrics. 2015;136:115–27. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-3319.

Hoffart CM, Wallace DP. Amplified pain syndromes in children: treatment and new insights into disease pathogenesis. Curr Opin Rheum. 2014;26:592–603. https://doi.org/10.1097/BOR.0000000000000097.

Hechler T, Kanstrup M, Holley AL, Simons LE, Wicksell R, Hirschfeld G, Zernikow B. Systematic review on intensive interdisciplinary pain treatment of children with chronic pain. Pediatrics. 2015;136(1):115–27. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-3319.

Claus BB, Stahlschmidt L, Dunford E, Major J, Harbeck-Weber C, Bhandari RP, Baerveldt A, Neß V, Grochowska K, Hübner-Möhler B, Zernikow B, Wager J. Intensive interdisciplinary pain treatment for children and adolescents with chronic noncancer pain: a preregistered systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis. Pain. 2022;163(12):2281–301. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002636.

Tran ST, Jastrowski Mano KE, Hainsworth KR, et al. Distinct influences of anxiety and pain catastrophizing on functional outcomes in children and adolescents with chronic pain. J Ped Psych. 2015;40:744–56. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsv029.

Palermo TM, Kashikar-Zuk S, Lynch-Jordan A. Topical review: Enhancing understanding of the clinical meaningfulness of outcomes to assess treatment benefit from psychological therapies for children with chronic pain. J Ped Psych. 2020;45:233–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsz077.

Carter B. Chronic pain in childhood and the medical encounter: professional ventriloquism and hidden voices. Qual Health Res. 2002;12:28–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/104973230201200103.

Kermani MK, Kanstrup M, Jordan A, Caes L, Guantlett-Gilbert J. Evaluation of an intensive interdisciplinary pain treatment based on acceptance and commitment therapy for adolescents with chronic pain and their parents: a nonrandomized clinical trial. J Ped Psych. 2018;2018(43):981–94. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsy031.

Saldana J. Longitudinal qualitative research: analyzing change through time. Walnut Creek: Altamira Press; 2003.

Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. (2005) Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15:1277–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687.

Wakefield EO, Belamkar V, Litt MD, Puhl RM, Zempsky WT. “There’s nothing wrong with you”: pain-related stigma in adolescents with chronic pain. J Ped Psych. 2022;47:456–68. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsab122.

Wakefield EO, Kissi A, Mulchan SS, Nelson S, Martin SR. Pain-related stigma as a social determinant of health in diverse pediatric pain populations. Front Pain Res. 2022;14:1020287. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpain.2022.1020287.

Palermo TM, Slack M, Zhou C, et al. Waiting for a pediatric chronic pain clinic evaluation: a prospective study characterizing waiting times and symptom trajectories. J Pain. 2019;2019(20):339–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2018.09.009.

Tong A, Jones J, Craig JC, Singh-Grewal D. Children’s experiences of living with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. Arth Care Res. 2012;64:1392–404. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.21695.

von Scheven E, Nahal BK, Kelekian R, et al. Getting to hope: Perspectives from patients and caregivers living with chronic childhood illness. Child. 2021;8:525. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8060525.

Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. The transtheoretical approach: crossing traditional boundaries of therapy. New York: Dow Jones-Irwin; 1984.

Stahlschmidt L, Grothus S, Brown D, Zernikow B, Wager J. Readiness to change among adolescents with chronic pain and their parents: is the german version of the pain stages of change questionnaire a useful tool? Children. 2020;7(5):42. https://doi.org/10.3390/children7050042.

Guite JW, Logan DE, Simons LE, Blood EA, Kerns RD. Readiness to change in pediatric chronic pain: initial validation of adolescent and parent versions of the pain stages of change questionnaire. Pain. 2011;152(10):2301–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2011.06.019.

Feinberg T, Jones DL, Lilly C, Umer A, Innes K. The complementary health approaches for pain survey (CHAPS): validity testing and characteristics of a rural population with pain. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(5): e0196390. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0196390.

Schaefer MR, Kavookjian J. The impact of motivational interviewing on adherence and symptom severity in adolescents and young adults with chronic illness: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;2017(100):2190–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2017.05.037.

Law E, Fisher E, Eccleston C, Palermo TM. Psychological interventions for parents of children and adolescents with chronic illness. Cochrane Datab Syst Rev. 2019;3:CD009660. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009660.pub4.

Simons LE, Basch MC. State of the art in biobehavioral approaches to the management of chronic pain in childhood. Pain Manag. 2016;6:49–61. https://doi.org/10.2217/pmt.15.59.

Kohut SA, Stinson J, Forgeron P, Luca S, Harris L. Been there, done that: The experience of acting as a young adult mentor to adolescents living with chronic illness. J Ped Psych. 2017;42:962–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsx062.

Newton BJ, Southall JL, Raphael JH, Ashford RL. LeMarchand, KA narrative review of the impact of disbelief in chronic pain. Pain Manag Nurs. 2013;14:161–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmn.2010.09.001.

Yen PH, Leasure AR. Use and effectiveness of the teach-back method in patient education and health outcomes. Fed Pract. 2009;36:284–328.

Healey EL, Lewis M, Corp N, et al. Supported self-management for all with musculoskeletal pain: an inclusive approach to intervention development: the EASIER study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2023;24:474. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-023-06452-4.

Meldrum ML, Tsao JC, Zeltzer LK. “I can’t be what I want to be’’: children’s narratives of chronic pain experiences and treatment outcomes. Pain Med. 2009;10:1018–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4637.2009.00650.x.

Simons LE, Sieberg CB, Conroy C, et al. Children with chronic pain: Response trajectories after intensive pain rehabilitation treatment. J Pain. 2018;19:207–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2017.10.005.

Funding

Children’s Mercy Kansas City Faculty Grant (Hoffart).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors participated in the research and development of this manuscript. KS, DW & CH designed the study KS conducted patient interviews KS, WB, JC conducted primary data analysis KS, WB, JC wrote the main manuscript text All authors provided substantive review of the manuscript throughout the draft development process and reviewed the manuscript prior to submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Stegenga, K., Black, W.R., Christofferson, J. et al. Longitudinal qualitative perspectives of adolescents in an intensive interdisciplinary pain program. Discov Psychol 4, 105 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44202-024-00222-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44202-024-00222-6