Abstract

Background

Immediate and efficient Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) increases both survival rate and post-arrest quality of life. Continual updated knowledge and practices of healthcare professionals regarding cardiopulmonary resuscitation were crucial to save lives. In limited resource countries like Ethiopia, there is scarce data describing the basic knowledge and practice of CPR among Healthcare providers (HCP).

Objectives

To assess health care professionals’ knowledge, practice, and associated factors toward CPR.

Methods

Institutional-based descriptive survey study design was used. The study was conducted from March to April 2022 in Addis Ababa Ethiopia, A total of 163 individuals were randomly selected from Tikur Anbesa Hospital. St. Paul’s Hospital and Yekatit 12 Hospital. The data was collected using a pre-tested structured questionnaire. The descriptive statistics frequency, percentage, median, and range were computed. Inferential statistics Bivariate and multivariate logistic regression were analyzed. Ethical approval was received from the Institutional Review Board.

Result

Out of 162 respondents, 81(50%) were nurses followed by 59 (36.4%) residents. The participants’ ages ranged from 24 to 49 years, median age of 29 years. More than half, 89(54.9%) of participants were female. Ninety (55.6%) participants had good knowledge of CPR. The majority of 126(79.6%) responded correctly about chest compression. Occupation type (AOR = 3.15, 95% CI 1.193–5.834) and participating in mock (AOR = 8.33, 95% CI 1.53–45.45) were associated with knowledge of health care professionals, Routinely reviewing data (COR = 3.3, 95% CI 1.41–7.82), and time of participating in mock codes (COR = 5.05, 95% CI 1.43–17.85) were associated with practice of health care professionals.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the level of knowledge and practice of health professionals towards CPR was suboptimal. Having a higher educational level and participating in mock codes were associated with good knowledge, whereas gender, routinely reviewing the data, and participating in mock codes were associated with good practice. Therefore; healthcare professionals must continuously improve their knowledge and skills in CPR for the sake of professionalism and patient safety.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Background

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is an emergency procedure consisting of chest compressions often combined with artificial ventilation, or mouth-to-mouth to maintain circulatory flow and oxygenation during cardiac arrest [1,2,3]. CPR is performed within the first six minutes of heart-beat stops until the heartbeat returns to normal or the patient is declared dead. CPR prevents Permanent death or brain injury [4,5,6,7,8,9]. CPR is initiated by looking in the patient’s mouth for a foreign body blocking the airway before beginning ventilations [1]. Then, after 30 chest compressions, 2 breaths are given (the 30:2 cycle of CPR); Chest compressions are to be delivered at a rate of 100 to 120 per minute. Then perform the head-tilt chin-lift maneuver to open the airway and determine if the patient is breathing. This process is repeated until a pulse returns or the patient is transferred to definitive care [10, 10,11,12,13,14].

Basic life support includes first identifying an event, calling 911, administering early cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), and using a publicly available automated external defibrillator (AED) device [1]. In the in-hospital setting or when a paramedic or other advanced provider is present, Advanced Cardiovascular Life Support (ACLS) guidelines call for a more robust approach to the treatment of cardiac arrest, including Drug interventions, ECG monitoring, Defibrillation, and Invasive airway procedures [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26].

There is a responsible group referred to as the Resuscitation Education Science Writing Group comprised of a diverse team of experts with backgrounds in resuscitation education, clinical medicine, nursing, pre-hospital care, health services, and education research. Writing group members are American Heart Association (AHA) volunteers with an interest and recognized expertise in resuscitation and are selected by the AHA Emergency Cardiovascular Care (ECC) Committee [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. Every year, millions of providers receive basic and advanced life support training [1]. Resuscitation training programs incorporate evidence-based content while providing opportunities for learners to practice lifesaving skills in individual and team-based clinical environments [1].

Previous exposure to cardiac arrest cases significantly influenced the CPR knowledge of health professionals. Those who have been exposed to cardiac arrest cases were more knowledgeable than those who have not been exposed [13]. The study indicates that the practice of cardiopulmonary resuscitation among health workers was low. The poor practice of cardiopulmonary resuscitation among health workers is attributed to low CPR knowledge [26]. The study revealed that doctors had higher levels of expertise than nurses. The study also found that nurses were performing more than doctors in caring out clinical practice [11]. It also revealed that both healthcare workers had completed CPR training. The study shows participants working in different wards were more knowledgeable compared with participants working in only one ward [14].

Studies in Nepal, Iran, and Pakistan show that health professional has good knowledge of resuscitation [18, 19, 22]. In contrast, other studies in Tanzania, Sweden, and different hospitals in Ethiopia (Debre Markos Hospital, Gonder University Hospital) had poor knowledge of resuscitation [3, 20, 24, 25]. In a study carried out in Ethiopia at Debre Markos Referral Hospital majority of respondents (88.9%) had unsafe practices regarding cardiopulmonary [24]. Studies revealed that HCPs having spent a longer number of hours in the emergency service, being a physician, or being a nurse and recently attending CPR training were associated with higher knowledge of CPR [13, 14, 20, 27, 28]. Studies find that there is an association between resuscitation and adequate resuscitation training [5, 29, 30].

In Ethiopia, a study revealed that training and previous exposure were factors associated with the good practice of CPR [31]. There is a scarcity of studies conducted on the level of knowledge and practice of CPR among healthcare professionals in developing countries, including Ethiopia. Therefore, this study quantifies the level of healthcare professional CPR capacity and factors that contribute to the accurate performance of CPR Fig 1.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study design and period

We conducted an institutional-based cross-sectional descriptive study conducted among healthcare professionals selected from three selected tertiary hospitals in Addis Ababa City, at the Emergency Department. This study was conducted from March to April 2022.

2.2 Study area

The study was conducted in Addis Ababa City, the capital city of Ethiopia and where the African Union and the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA) is headquartered. The study was conducted in three tertiary public hospitals (Tikur Anbesa, St. Paulo’s, and Yekatit 12 Hospitals) selected from 13 public hospitals in Addis Ababa City. These hospitals currently provide tertiary level emergency care services in Addis Ababa where CPR provider heath care professionals mainly situated.These are teaching and tertiary hospitals in the City, where many patients who require resuscitation are visited, admitted, and treated [32,33,34].

2.3 Source population

All healthcare professionals who were working in the emergency departments of the selected hospitals.

2.4 Study population

Healthcare professionals who practice Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation activity at emergency department of selected hospitals and fulfilled the selection criteria were the study population.

2.5 Eligibility criteria

Healthcare professionals (residents and nurses) who were assigned to emergency departments during the data collection period were included in the study.

A healthcare professional who was critically ill during the study period and those on annual/maternity leave were excluded from the study.

2.6 Sample size determination and sampling procedure

2.6.1 Sample size determination

The sample size of this study was determined by using a single population proportion formula. The prevalence (50%) was taken from another similar country. The sample size was computed as:

N = (Z a/2)2 xPx (1-P) = (1.96)2 × 0.5 x (1–0.5) = 384.16 ⁓ 385.

Where N = the required sample size, Z = standard score corresponding to 95% confidence interval 1.96, P = the estimated proportion, d = the margin of error 5% and d2 (0.05)2.

The population of health workers in our study area was less than 10,000, the finite population correction formula wias:

nf = ni / [1 + {(ni—1) / N}] = 242/ (1 + {(242—1) /384}] = 148.

Considering a 10% non-response rate, the final sample size becomes 163.

Therefore, by using the correction formula, the actual sample size calculated was 148. After considering the 10% non-response rate, the sample size was 163.

2.7 Sampling techniques and procedures

All healthcare professionals working in the emergency department of Tikur Anbesa Specialized Hospital, St. Paul’s Hospital, and Yekatit 12 Hospital have been counted and a proportional sample size was allocated to the healthcare professionals.

Ninety-eight healthcare professionals were working in the emergency department of TASTH. St. Paulo’s Hospital had 94 healthcare professionals in the emergency department. In Yekatit 12 Hospital, 50 healthcare professionals were working in emergency departments.

Schematic presentation of sampling procedure of TASH, St. Paulo’s, and Yekatit 12 Hospitals presented as follows:

2.8 Data collection instrument and procedure

The questionnaire was derived from a standard reference American Heart Association.

(AHA) guidelines for CPR and emergency cardiac care [1]. Consequently, a self-administered structured questionnaire which was adopted from the previous studies [19, 21, 24, 31]. After obtaining the necessary permits, and after advance notification, the personnel were asked for consent to participate in the study about the knowledge and practice of emergency healthcare professionals in a private setting.

The tool has four parts which include:

-

Socio-demographic characteristics

-

Facility and work related characterstics

-

Knowledge of Health care professionals, and

The practice of Health Care Professionals towards CPR The knowledge section contained 14 multiple-choice items while the practical section included 7 multiple-choice items. Knowledge questions were scored as binary variables; correct answers were given 1 point and 0 points for incorrect responses. Practical questions were awarded 1 point for a correct response, while incorrect answers and “do not know” responses were given 0 points.

The data was collected after written consent was taken at the site upon the data collection, the data collector instructed the participants to fill out the questionnaire independently to maintain the transmission of information between the participants. Participants were also asked to answer the questionnaire without consulting any materials or textbooks and to answer according to their current, best knowledge and practice.

2.9 Operational definition

For this study, good knowledge is the level of CPR conception of participants who scored above the mean value among the given correctly answered knowledge questions [36]. Good practice is the level of CPR performance of participants who scored above the mean value among the given correctly answered practice questions. Those who scored below the mean score value of correctly answered questions were labeled as poor [35].

2.10 Data quality control

This study used a structured questionnaire in English version adopted from various literature. Pre-testing was done one week before data collection started at Zewditu Memorial Hospital. The training was given to three data collectors, and 2 supervisors, before data collection. Supervisors and the principal investigator conducted supervision to test the inter-rater reliability of data collectors,

2.11 Data processing and analysis

The collected data was checked for completeness, coded, and entered into a computer. The data cleaning was computed for outliers. The entered data were analyzed by using Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 25 software. The data was described using frequency, mean, median, and range. Bivariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis is used to identify variables having significant association with the dependent variables. The variable variables with a p-value of < 0.02 from the bivariate logistic regression model were again analyzed by multivariate logistic regression to see the effect of independent variables on the dependent variable. Based on OR with 95%CI the output of multivariate logistic regression analysis identifies variables that have statistically significant associations.

2.12 Ethical consideration and consent

The study was performed based on the ethical standards of put down in the declaration of Helsinki. Ethical clearance was obtained from the institutional ethical review committee of the School of Nursing and Midwifery College of Health Science at Addis Ababa University. The study has an ethical clearance letter protocol number of 44/22/SMN/2022.

After a written official letter was provided to the three hospitals, permission to conduct the study was secured from each hospital official. The study participants were briefly informed about the questionnaire and the aim of the study. The written consent obtained from each study participant. Confidentiality of the individual participant was anonymously maintained. The participants also informed that they had the right to withdraw from the study at any phase of the study.

3 Results

3.1 Socio-demographic Characteristics of healthcare professionals

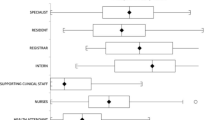

A total of 162 participants (giving a response rate of 99%). were involved in the study. The participants’ ages ranged from 24 to 49 years, with a median age of 29 years. The majority of the respondents were in the age group of 20 to 30 years, 117(72.2%). More than half, 89(54.9%) of the participants were female. Half of the respondents, 81(50%) were nurses followed by 59 (36.4%) residents (Table 1). With regard to qualifications, 74(45.7%) were BSc followed by 59(36.4%) Medical doctors. Concerning years of experience, the majority of participants 116(71.0%) had less than 5 years of health facility experience. Most of the participants 156(96.3%) had less than five years in the emergency department.

3.2 Facility, work-related characteristics of emergency health care professionals

The majority of respondents accounting for, 126(77.8%) of individuals had more than 5 times exposure to cardiac arrest patients. Regarding CPR training, 76(46.9% of the respondents had previously received CPR training during the last 6 months. More than half 107(66.1%) of the study participants had updated their CPR awareness by reading CPR guidelines and protocols. Regarding unnecessary interruptions accounting, 62(38.3%) respondents were interrupted by chest compressions during resuscitation of a cardiac arrest except on time defibrillation and pulse checks. More than half 108(66.7%) of cardiac arrest data were not reviewed routinely by a hospital committee or in a conference. Regarding mock code, more than half 105(64.8%) of participants had no set schedule (Table 2).

3.3 Knowledge level of health care professionals about adult CPR

On average more than half 90 (55.6%) of participants had good knowledge about adult CPR. The most correctly answered question by study participants was an abbreviation of “Basic Life support (BLS) 143 (88.3%), followed by pulse check 142(87.7%). The least answered question was the first step for CPR for an adult having food in a canteen and suddenly starts expressing symptoms of choking 35(21.6%), followed by an abbreviation of Automated External Defibrillator (AED) 41(25.3%) (Table 3).

3.4 Healthcare professionals’ cardiopulmonary resuscitation practical performance

Of the 162 healthcare providers, 151(93.2%) responded correctly about how they ventilated and compressed the chest. The majority 126(79.6%) of respondents correctly performed chest compression at a rate of 100–120 per minute. Participants accounting for, 115(71.0%) operated a defibrillator correctly. Regarding the depth of compression and site chest compression 96(59.3%) and 84(51.9%) of respondents correctly differentiated the depth of compression and located the site of compression respectively (Table 4).

3.5 Factors associated with knowledge of emergency health care professionals

In the bi-variable logistic regression analysis, variables such as professional occupation, participation in CPR training, and participation in mock codes were significant. However, in multivariable logistic regression, only Professional occupation and participating in mock codes were significantly associated with good knowledge.

Health professionals having a specialty field of resident educational status were 3.024 Times (AOR = 3.024, 95% CI 1.029–8.881) more likely to have good knowledge as adjusted for non-specialty. Accordingly, critical care spatiality nurse educational status was 2.638 times (AOR = 2.64, 95% CI 1.19–5.83) more likely to have good knowledge as adjusted for non-specialty nurse. The study also revealed that the likelihood of having good knowledge of adult CPR was 8.343 times (AOR: 8.334, 95% CI 1.528–45.45)) higher among health professionals who had participated at least every 2 to 3 months of mock codes as compared with mock cod not participated, participate annually (Table 5).

3.6 Factors associated with the practice of healthcare professionals

Bivariate logistic regression was used to establish the crude odds ratio of emergency health professional practical performance. Health professional occupation, period of participation training, data routinely reviewed, and time of participating in mock codes were significantly associated with practical skills. However, in multivariable logistic regression, only data routinely reviewed and time of participating in mock codes were significantly associated with practical skill (Table 6).

In an adjusted odd ratio, emergency health professionals who had routinely reviewed cardiac arrest data were 3.3 times more likely to have good practice (COR = 3.3, 95% CI 1.41–7.82) than those who had not been routinely reviewed. Health professionals with at least monthly participation in suit mock cod were 5.05 times more likely to have practical skills [COR = 5.05, 95% CI (1.43–17.85)] than those who did not participate.

4 Discussion

The study found that the health professionals had low knowledge and practical skills in CPR. Specifically, the current study revealed that knowledge of emergency health care professionals towards CPR was 55.6%; this finding was higher than the study conducted in Gondar (25.1%) [25] and less than the study conducted in Nepal (68%)[18]. The possible reason might be, in Gondar’s study above average cut-off point (80%) was used as a pass mark for good knowledge of health professions.

Only 21.6% of survey participants were aware of the first action that should be taken for a victim who suddenly displayed a sign of choking while eating. In this study (38.3%), participants were aware of signs of severe airway obstruction. Our findings are higher than a study in Gondar (32.3%) [25]. The difference may be related to the study’s use of a variety in the context and time frame of the study.

In a multivariable regression analysis, the participant’s level of education was found to be significantly associated with good knowledge of CPR. In this regard, having a master’s and resident was found to be 2.64 times more to have good knowledge as compared with non-specialized nurses. This finding was supported by the study conducted in Gondor [25]. A possible explanation might be that educational advancement can increase the knowledge of CPR. Therefore, healthcare professionals’ educational development increases CPR knowledge which in turn benefits the patient who suffers from cardiac arrest.

The participants who participated in mock codes were found to have 8.3 times higher knowledge than those who had not participated. This finding was in line with the study done in Peru [21]. The possible explanation might be that training and mock participation can allow the engagement of all personnel and resources applicable to real arrests. In our study, 40.1% of healthcare professionals were aware of the defibrillator sequence. This finding was lower than in a study conducted in Tanzania in which more than half of HCPs reported knowing the defibrillator sequence (56%) [3]. This may suggest that HCPs in our setting exercise CPR with inadequate capacity to perform advanced life support.

The prevalence of good practice towards CPR among emergency healthcare professionals was 46.3% in the selected emergency hospitals. The finding was lower than a study carried out in Nigeria [28] which found 65.2%. Possible explanations might be because of study tool variation in using the cut points, immediate code debriefing not performed after each resuscitation, and due to their qualification status.

The prevalence of good practice towards CPR among nurses working in three hospitals was lower (29.6%) than in a study done in Tanzania [3]. The possible suggestion might be a lack of continuous and formal training, and data were not reviewed routinely. This is supported by a previous study from the Islamic Republic of Iran similarly stressed the need for continuous and regular training to improve CPR knowledge among emergency staff [19].

Half (51.9%) of participants correctly identified the site of chest compression. In this study, 45.7% of respondents agreed on the steps for the sequence of CPR (Chest compressions, Airway, and Breathing). This finding seeks a series of considerations for the requirement of prerequisite for registration of annual practicing license to ensure strict compliance [28].

In a multivariable regression analysis, data routinely reviewed and frequently participating in mock codes was associated with an increased likelihood of correct performance of CPR (compression rate, compression depth, compression to ventilation ratio).

The accomplishment of the present study was not without limitations. First, the study used a self-administered questionnaire tool that may not be the most effective tool to assess the practical skills or abilities of these healthcare professionals. Second, only nurses and residents from the emergency department are selected. Third, limited literature review assessed in Ethiopia, affects the discussion section to compare with other studies. Finally, this study also used under average (< 50%) quantity to measure poor knowledge and practice that may not measure the exact Cardiopulmonary resuscitation capability of healthcare professionals.

4.1 Concluding and recommendation

In conclusion, the level of knowledge and practice of health professionals towards adult CPR was suboptimal. Having a specialized higher educational level and participating in mock codes showed a positive and significant association with good knowledge, whereas routinely reviewing the data, and participating in mock codes were found to be associated with good practice of the emergency department of health care professionals. Thus, in this study, a specialized functionality and active continuous practice enhances CPR capacity in our setting.

Therefore; healthcare professionals must continuously improve their knowledge and skill in CPR for the sake of their professional specialization and maintaining patient safety. A continuous CPR training program and guidelines should be prepared to improve the knowledge and performance of HCPs to ensure optimal patient outcomes. Supervision should be done continually by health care professional regulatory officials. after training to ensure that health workers follow the recommended guidelines. The hospital committee and emergency department managers should regularly audit CPR practices for cardiac arrest cases. Further analytic studies that investigate how formal and structured education determine the healthcare professional’s CPR capability were suggested. Finally, conducting studies that include appropriate tools to measure the level of skills of professionals by simulation-based or real cardiac arrest cases is recommended.

Data availability

The raw data is available from the corresponding authors on rational request, and the summary data are available on the main document.

Abbreviations

- CPU:

-

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation

- HCP:

-

HealthCare professionals

- BLS:

-

Basic life support

- AED:

-

Automated external defibrillator

References

Myra WM, Soar J, Greif R, Liley H. International consensus on cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care science with treatment recommendations. Circulation. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2021.10.040.

Bonny A, Tibazarwa K, Mbouh S. Epidemiology of sudden cardiac death in cameroon: the first population-based cohort survey in sub-Saharan Africa. Int J Epidemiol. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyx043.

Kaihula WT, Sawe HR, Runyon MS, et al. Assessment of cardiopulmonary resuscitation knowledge and skills among healthcare providers at an urban tertiary referral hospital in Tanzania. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3725-2.

Robert Graham MAM, and Andrea M. Strategies to Improve Cardiac Arrest Survival: A Time to Act Washington, DC: The National Academies ISBNs. REPORT BRIEF. 2015.

Elisabeth EK, Linderoth G, Tofte GM, Lippert F, Folke F. Impact of dispatcher-assisted cardiopulmonary resuscitation on neurologically intact survival in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a systematic review. 2021. Scand J Trauma, Resusc Emerg Med. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13049-021-00875-5.

LE Morley PT, Aickin R, Billi JE, Eigel B, Ferrer JM, et al. Part 2: evidence evaluation and management of conflicts of interest: international consensus on cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care science with treatment recommendations. Circulation. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000271.

Okonta KE, Okoh BA. Theoretical knowledge of cardiopulmonary resuscitation among clinical medical students in the University of Port, Harcourt. Nigeria Afr J Med Health Sci. 2015;14(1):42–6.

Virani SS, Chair AA, Aparicio HJ, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—a report from the American heart association. Circulation. 2021;143:e254–743. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000950.

Wachira B. Characterization of in-hospital cardiac arrest in adult patients at a tertiary hospital in Kenya. Afr J Emerg Med. 2015;5(2):70–4.

Cheng A, Magid DJ, Auerbach M, et al. American heart association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2020;142(16):S551–79. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000903.

Olasveengen TM, Semeraro F, Ristagno G, et al. European resuscitation council guidelines basic life support. Resuscitation. 2021;161(1):98–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2021.02.009.

Khatun R, Chowdhury S, Goni O. Knowledge and attitudes towards cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a cross-sectional survey on health care providers in clinical practice. Health Sci Q. 2021;1(3):87–93. https://doi.org/10.26900/hsq.1.3.01.

de Roux Q, Chalkiass A, Xanthos T, Mongardon N. In-hospital cardiac arrest: evidence and specificities of perioperative cardiac arrest. Criti Care. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-022-04300-w.

Gebre Mersha AT., Egzi AHK, Tawuye HY. Factors associated with knowledge and attitude towards adult cardiopulmonary resuscitation among healthcare professionals at the University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital Northwest Ethiopia: an institutional-based cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-037416.

Raffee LA, Samrah SM, Yousef HNAL, Abeeleh MA. Incidence, characteristics, and survival trend of cardiopulmonary resuscitation following in hospital compared to out of hospital cardiac arrest in Northern Jordan. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2017;21(7):436–41.

Obermeyer Z, Abujaber S, Makar M, et al. Acute care development consortium emergency care in 59 low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Bull World Health Organ. 2015;93(8):577-86G. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.14.148338.

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2020). World Mortality. 2019

Yosha HD, Tadele A, Teklu S, Melese GK. A two-year review of adult emergency department mortality at Tikur Anbesa Specialized Tertiary Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Emerg Med. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12873-021-00429-z.

Poudel M, Bhandar R, Gir R, Chaudhary S, Uprety S, Baral DD. Knowledge and attitude towards basic life support among health care professionals working in emergency of BPKIHS JBPKIHS. J BP Koirala Inst Health Sci. 2019;2(1):18–24. https://doi.org/10.3126/jbpkihs.v2i1.24962.

Papi M, Hakim A, Bahrami H. Relationship between knowledge and skill for basic life support in personnel of emergency medical services, Islamic Republic of Iran. East Mediterr Health J. 2020;26(10):1193–9. https://doi.org/10.26719/emhj.19.018.

Silverplats J, Källested Marie-Louise S, Wagner P, Ravn-Fischer A, Äng B, Strömsöea A. Theoretical knowledge and self-assessed ability to perform cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a survey among 3044 healthcare professionals in Sweden. Eur J Emer Med. 2020;27(5):368–72. https://doi.org/10.1097/MEJ.0000000000000692.

Aranzábal-Alegría G, Verastegui-Díaz A, Quinones-Laveriano DM, et al. Factors influencing the level of knowledge of cardiopulmonary resuscitation in hospitals in Peru. Colomb J Anesthesiol. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rca.2016.12.004.

Irfan B, Zahid I, Sharjeel Khan M, et al. Omar Abdul Aziz Khan4, Shayan Zaidi4, Safia Awan Current state of knowledge of basic life support in health professionals of the largest city in Pakistan: a cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;19(1):865. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4676-y.

Kalhori RP, Najafi M, Foroughinia A, Mahmoodi F. A study of cardiopulmonary resuscitation literacy among the personnel of universities of medical sciences based in Kermanshah and Khuzestan provinces based on the latest 2015 cardiopulmonary resuscitation guidelines. J Edu Health Promot. 2021. https://doi.org/10.4103/jehp.jehp_645_20.

Temesgen AA, Zeleke LB, Assega MA, Sefefe WM, Gebremedhn EG. Health-care providers’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding adult cardiopulmonary resuscitation at debre markos referral hospital, gojjam Northwest Ethiopia. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2021;12(1):647–54.

Mersha AT, Gebre Egzi AHK, Tawuye HY, et al. Factors associated with knowledge and attitude towards adult cardiopulmonary resuscitation among healthcare professionals at the university of Gondar comprehensive specialized hospital, Northwest Ethiopia: an institutional-based cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-037416.

Manono BK, Mutisya A, Chakaya J. Assessment of knowledge and skills of cardiopulmonary resuscitation among health workers at Nakuru County Referral Hospital. Int J Community Med Public Health. 2021;8(7):3224–30. https://doi.org/10.18203/2394-6040.ijcmph20212570.

Alotaibi O, Alamrri F, Almufleh L, Alsougi W. Basic life support: knowledge and attitude among dental students and staff in the college of dentistry, King Saud University. Saudi J Dent Res. 2016;7(1):51–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sjdr.2015.06.001.

Aliyu I, Michael GC, Ibrahim H, Ibrahim ZF, Idris U, Zubayr BM, et al. Practice of cardiopulmonary resuscitation among health care providers in a tertiary health center in a semi-urban setting. J Acute Dis. 2019;8(4):160–4. https://doi.org/10.4103/2221-6189.263709.

Chan JL, Nallamothu BK, Tang Y, et al. Association between hospital resuscitation champion and survival for in-hospital cardiac arrest. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.120.017509.

Veronese J, Wallis L, Rachel AR, Allgaier R, Botha R. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation by emergency medical services in South Africa: barriers to achieving high-quality performance. Afr J Emerg Med. 2018;8(1):6–11.

Kelkay MM, Kassa H, Birhanu Z, et al. A cross-sectional study on knowledge, practice, and associated factors towards basic life support among nurses working in Amhara region referral hospitals, northwest Ethiopia, 2016. Hos Pal Med Int Jnl. 2018;2(2):123–30. https://doi.org/10.15406/hpmij.2018.02.00070.

http://www.aau.edu.et/chs/tikur-anbessa-specialized-hospital/background-of-tikur-anbessa-hospital/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/St._Paul%27s_Hospital_Millennium_Medical_College

Abate H, Mekonnen CH. Knowledge, practice, and associated factors of nurses in pre-hospital emergency care at a tertiary care teaching hospital. Open Access Emerg Med. 2020;12(1):459–69.

Saquib SA, Khoshhal Al-Harthi HM., AA., et al. Knowledge and attitude about basic life support and emergency medical services amongst healthcare interns in university hospitals: a cross-sectional study. Emerg Med Int. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/9342892.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Addis Ababa University for allowing us to conduct this study.Our appreciation goes to Tikur Anbesa Hospital. St. Paul’s Hospital and Yekatit 12 Hospital management committees, staff, and data collectors for their support during the data collection process.

Funding

The study was supported by the Addis Ababa University, College of Health Science. The funding does not have a further role in the design, data collection, analysis, drafting, manuscript, preparation, and publication of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.B. Conceptualization, method development, analysis and wrote the main manuscript draft. Z.M and N.G. Supervising. Review and editing B. K. Data collection, review and editing All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical clearance and approval were obtained from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Addis Ababa University, College of Health Sciences, An Official letter was obtained from the Department of Nursing and Midwifery. Permission was obtained from the clinical director of each study hospital. After explaining the purpose of the study and the possible benefit of the study, permission was obtained from each hospital emergency department. Health professionals offered written informed consent for free study participation according to IRB approved consent procedure. Confidentiality of the participant was anonymously maintained. The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Belay, M., Mengistu, Z., Getahun, N. et al. Health professionals’ cardiopulmonary resuscitation capability at emergency departments in tertiary hospitals, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2022. Discov Med 1, 40 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44337-024-00022-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44337-024-00022-w