Abstract

Introduction Access to dental services is a growing problem for older people in the UK. The aim of this scoping review is to identify the barriers and facilitators influencing older people's ability to access oral healthcare in the UK based on the existing literature.

Methods The scoping review followed the framework proposed by Levac and colleagues (2010). Peer-reviewed literature was retrieved in April 2023 from Web of Science, Medline, PsycInfo and CINAHL for the period 1973-2023. After screening, data were extracted to identify barriers and facilitators mapped to individual, organisational and policy-level factors. The themes generated were used to identify gaps in the literature and policy recommendations.

Results Overall, 27 studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Most studies published were from England; there was a large representation of opinion pieces. The main barriers and facilitators related to cost of services, perceptions of dentistry, availability of services and both the dental and social care workforce.

Conclusion Multiple barriers exist surrounding access to dental care for older people. Various facilitators exist but not all are successful. More research needs to be carried out on older people's access to dental services in the community, particularly for the ‘oldest old' and minority groups.

Key points

-

This study maps the existing evidence surrounding access to oral healthcare for older adults in the UK.

-

The study highlights that many barriers and facilitators to accessing oral healthcare exist but there are gaps in the literature regarding representation of marginalised groups within this population, such as older people living in the devolved nations, the ‘oldest old' (85+) age group, and minority ethnic groups living outside of London.

-

Whilst many barriers and facilitators have not changed in the last 50 years, commissioners and policymakers need to consider how the structure of dental services needs to actively support older people's access-related needs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Within the UK, a significant proportion of people are aged 65 or older.1,2 This is leading to a larger population subgroup who require access to dental services but who may suffer difficulties doing so due to the ageing process. The extent and prevalence of oral diseases is greater in older people. This is a result of multiple factors, such as greater difficulty with self-care practices, dry mouth from polypharmacy and the development of comorbid conditions which influence oral health, such as diabetes.3,4 In addition, as more older people are retaining their teeth into old age, those with heavily restored dentitions require increased maintenance than other population groups and previous generations.5,6 This typically leads to older people facing a greater level of impact of poor oral health on their quality of life, contributing to oral and general frailty and malnutrition.4,7,8,9,10

Access to dental services is an important factor in being able to support older people's oral health. Dental teams may assist with ongoing prevention, symptomatic relief of odontogenic pain, xerostomia and pathological mobility, earlier detection and screening of oral cancer, and provision of dentures.11,12,13 There is limited guidance on oral healthcare for older people in the UK. Guidance that does exist typically focuses on those in care homes, which includes the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines and the Care Quality Commission (CQC) guidance.14,15 However, the care home population only constitutes 3.2% of older people in England and Wales.16 To effectively design healthcare policy and inform commissioning decisions, a clear evidence base needs to be established to highlight comprehensively what is important in accessing oral healthcare.

Many studies have assessed access to oral healthcare for specific groups, such as vulnerable adults, people with mental health issues, those with protected characteristics and those in care homes.17,18,19,20 Scoping reviews have only been undertaken on one aspect of access to oral healthcare. Examples includes the provision of rural geriatric care, teledentistry, and geriatric dental education, and older people's views on accessing oral healthcare.21,22,23,24 To date, however, no studies have been carried out to summarise the barriers and facilitators for all older people.

The aim of this study is to identify the barriers and facilitators influencing older people's ability to access oral healthcare in the UK.

Materials and methods

The objectives of this study were:

-

Review current literature related to accessing oral healthcare for older people in the UK since 1973 and identify the evidence available

-

Identify barriers and facilitators for access and organise them into categories: individual, organisational and policy levels

-

Identify areas for further research, commissioning and policy recommendations for older people in the UK.

A scoping review was considered necessary to map the evidence surrounding access to dental services for all older people. The scoping review followed the enhanced framework from Levac and colleagues which used the stages described by Arksey and O'Malley.25,26 A protocol was drafted and followed to ensure adherence to the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) guidelines.27

Inclusion criteria were as follows:

-

Studies in English language only

-

Any peer-reviewed research or opinion piece evaluating older people's access to oral healthcare, particularly evaluating access to dental services

-

Any appropriate study found post hoc where additional search terms were discovered

-

Studies based in the UK and/or any devolved nation

-

Studies carried out between 1973-2023.

Exclusion criteria were:

-

Studies not carried out in English

-

Studies evaluating only populations under age 60 or where the population is not specified as ‘older people', unless the study involves those caring for, or providing healthcare for, older people

-

Case reports, case series, letters and conference abstracts and proceedings

-

Studies which evaluated oral healthcare or mouth care without describing access to dental services, and studies which did not discuss access to oral healthcare for older people

-

Scoping review protocols

-

Systematic reviews.

Age 60 years was chosen as the age cut-off as some older studies used this to reflect historical retirement ages for women and shorter life expectancies in the UK.28 As the review sought to advise policymakers within the UK, non-UK sources were excluded.

Search terms: (dental OR oral) AND (healthcare OR service*) AND (‘older people*' OR elderly OR senior OR geriatric) AND (challenge OR facilitators OR ‘barrier* and facilitator*' OR hindrance OR access* OR avail* OR enabl* OR motivators). A librarian was consulted for clarification with Boolean operators relevant to each database search. Databases searched were Web of Science (including Medline), PsycINFO and CINAHL.

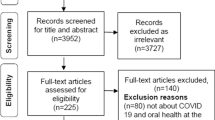

Abstracts and papers were retrieved. The number of studies selected is shown in Fig. 1. Some papers were unobtainable. The study was constrained by time so it could be used to contribute to commissioning decisions about dental services and national survey design. Consequently, there was no hand-searching of reference lists or grey literature. The final search was carried out on 25 April 2023.

Study titles and abstracts were screened for inclusion into the study. Full-text articles were viewed where the study was thought to address access to oral healthcare for older adults but where this was not explicitly discussed in the abstract. Two reviewers then carried out full-text screening of a sample of articles. Figure 1 shows the PRISMA-ScR flowchart of study selection (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: Scoping Review). The results were exported to the reference management software Endnote Online and duplicates removed. The JBI extraction template was used.27 This instrument was piloted by one reviewer. A second reviewer provided feedback and the data extraction form was finalised. Data extraction was carried out by a single reviewer in June 2023, following training from a second reviewer. Data extraction included the following information: title; lead author; year of publication; country; population; setting; age of participants; study type; study aims; key results; facilitators and barriers according to individual/organisational/policy-level; research gaps; and additional notes. Due to the nature of the scoping review, whilst some study limitations were identified, studies were not assessed for quality.29 Results of the barriers and facilitators were categorised into individual, organisational and policy-level factors which are summarised in Table 1 and Table 2. A qualitative thematic analysis was conducted to identify themes which could link barriers or facilitators together into sub-categories: these were agreed by both reviewers.

Using individual, policy-level and organisational factors can identify clear areas where policy and commissioning at both national and community levels can occur, whilst highlighting ways that local factors may also be addressed. Organisational and policy-level factors were compared between studies and used to create specific policy recommendations, in line with other scoping reviews on access to dental care.17,18,19

Results

The initial search of peer-reviewed articles yielded 1,272 papers; the overall number of included studies was 27. The PRISMA flowchart shows the number of included studies (Fig. 1). Most studies were qualitative (n = 10; 37%). Five studies did not specify the age of participants apart from describing them as ‘older adults'. Three studies included adults over the age of 60; for one of these, women were included over age 60 and men were included over age 65, reflecting the sex differences in the legal pensionable age at the time the study was undertaken. Other age ranges given were unspecified (five studies), over 75 (one study), over 63 (one study), and mostly over 85 (one study). The years included in the study ranged from 1984-2021. Of the studies included, eight were opinion pieces, three were mixed-methods studies, ten were qualitative studies and two were quantitative. There was one audit, one service evaluation and one strategy review. Of the English studies, a mixture of regions were represented: London (3), North West (3), North East (3), South East (2) and South West (1). There were two studies from Scotland, one from Wales and none from Northern Ireland. Of the 18 primary studies included, the mean sample size was 636 (range 21-10,600). These samples included a combination of older adults, care home staff, dental workforce and other stakeholders in dentistry. Two studies specifically included an ethnically diverse sample and four studies assessed minority ethnic groups exclusively. Barriers and facilitators are summarised in Tables 1 and 2.

Individual barriers

The main barriers related to cost, dental anxiety, mobility issues, generational attitudes and beliefs about dentistry and dental services. Overall, 17 (63%) papers mentioned cost as a barrier to care.30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46 Cost was a barrier to care either directly or indirectly, including the fear of cost.34,36,37,41,44 Cost was more of a barrier for those living in the community; those in residential homes relied on the family to pay, which was sometimes a barrier.31,46

Dental anxiety

Dental anxiety and past negative experiences of dentistry were barriers to care.38,45,47 Negative experiences included past painful, frightening or unsuccessful treatments, or disliking the dental surgery or dentist's character.34,41,42,47

Loneliness

Six papers discussed living alone, isolation, or lack of social support as being a barrier to care.34,35,43,44,48,49 This was more for adults aged over 85, men, those living alone and those without an escort.34,35,36,41,51 Living in a care home with dementia became a barrier due to the lack of ability to communicate oral health needs.44

Mobility

In total, 11 papers identified mobility as a barrier to attendance, which was from having difficulty leaving the house, being disabled, frail, or unable to use stairs.30,31,32,34,35,36,38,41,45,48,51 Issues existed with not being able to get to the practice due to distance, parking, public transport or other health conditions.33,33,35,37,39,41,48 For those with dementia, the resultant confusion or disorientation from journeying to appointments resulted in care-resistant behaviour.38,39

Generational attitudes

Five studies identified generational attitudes as a barrier which did not change over life.30,33,36,37,44 These included the fear of bothering the dentist, fatalistic attitudes towards oral health in ageing and a preference to manage problems at home.35,37 In total, 13 reports identified lack of perceived need for dental visits as a barrier to accessing care, which related to older people being born when being edentulous was more common, particularly before the NHS.30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,40,41,42,43 Some people believed that dentists were profit-driven and were influenced by social networks, negative media representation of dentistry and lack of knowledge of available services.33,41,47 Some older people considered seeing doctors rather than dentists for mouth problems.31,32,38

Individual facilitators

The main individual facilitators were related to dental beliefs. These included being motivated to attend and seek care, having positive experiences of dentistry and a belief that visits are beneficial and a moral duty.30,32,34,38,41,42

Organisational barriers

Racism and cultural factors

Older people from minority ethnic groups experienced additional challenges to accessing care. These included experiences of racism and hostility from services, lack of knowledge of local services, and not having dentists nearby who could speak the same language.33,37,47 Specific cultural beliefs reinforced the lack of perceived need for dentists, such as that tooth loss was not serious, that treatments could be inappropriate and the fear of being perceived negatively for help-seeking behaviours.37

Dental workforce

The number of dentists carrying out NHS care, community dental services, NHS dental practices and services providing domiciliary care was both varying and inadequate.39,46,52,53 Not all dental practices offered domiciliary appointments, even upon request.41,46 For general dentists, this was due to lack of remuneration, equipment difficulties, anxieties around medical emergencies and personal safety, and not being able to provide quality care in a non-dental setting.30,38,49

Referral pathways and organisational structures

The referral pathways for both domiciliary and community dental services were often complex and included long waiting times.46,52 For in-practice appointments, barriers included a lack of accessible parking, no ground floor surgeries, no wheelchair access and small surgeries which could not accommodate mobility aids.41,49,53 Some dental services did not have any relationship with local care homes, nor did they contact older people for recall visits, yet older people could not book appointments in advance.31,41,43,46,51

Organisational barriers and facilitators

The main facilitators surrounding the organisation of dental services related to increasing the availability of domiciliary, outreach and/or teledentistry appointments,34,38,46 ensuring waiting times were reduced,41 and becoming more wheelchair-friendly.38

Dental practice environment

Dentists' attitudes could create an unfriendly surgery environment which became a barrier to accessing care; a positive, friendly, listener-oriented attitude was considered a facilitator.41,54 One older study identified dentists as not understanding their role in maintaining oral health as part of healthy ageing; a more recent study highlighted aspects of non-verbal communication, such as being rushed.41,51

Health and social care workforce

Workforce issues related to the need to upskill both dentists and the social care workforce around oral health and care for older people, as well as raising awareness and planning services to promote oral health in other sectors and to become more culturally competent, were proposed facilitators.31,35,39,43,44,45,52,53,54,55

Studies highlighted that both formal and informal carers lacked knowledge and held unhelpful attitudes for older people in seeking care.31,35 These were more severe if carers were older, dentally anxious, unpaid, or not regular dental attenders themselves.31 Carers were often busy and had little time to attend dental issues or appointments; where they did, they did not have the required information on medications and exemption charges that the dentist needed to provide care.36,43,43,49,54,56 Care staff sometimes acted as gatekeepers for making appointments when oral health needs of residents was considered unimportant or not a priority, or from a belief that the older person would be unamenable to receiving treatment.31,35,44,46,48,56 They also made inappropriate referrals to doctors for oral issues.46,54

The key organisational facilitators related often to raising the importance of oral health in care homes to improve referrals, including more training for caring staff and implementing oral health assessments.31,35,39,53,54,56,57

Policy-level barriers and facilitators

Policy-level barriers identified were the lack of free dental services for older people,40,41,46 lack of automatic exemption charges,41 lack of adequate remuneration for domiciliary services,44,52 changes to the NHS contract system resulting in privatisation of practices,46,48,57 lack of needs-based workforce planning and service commissioning, especially for domiciliary care,36,38,39 and lack of training of health and social care workers in mouth care.38,53 Policy-level facilitators typically existed as proposed solutions. These included: commissioning services according to need, including care home services,30,31,39,40,41,47,49,53 creating guidelines relevant to older people,38,39,47,54 and improving referral pathways.,39,41,46,49,52 including blending in-surgery with domiciliary appointments,38 and improving referral pathways. They also included upskilling the dental workforce and improving training to manage generational values and communication needs.33,39,41 Seven studies identified the need for collaboration between all aspects of health and social care.38,40,41,46,53,54,57 Ensuring media representations of dentistry were more balanced was also highlighted.41Policy recommendations synthesised from the primary results are shown in Box 1 and Box 2.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to identify and map existing research surrounding access to oral healthcare for older adults to provide policymakers and commissioners with an evidence-base to improve access and surveys for this population subgroup. Whilst not all barriers and facilitators may apply to all older people, the results of the study nevertheless highlighted age-specific factors. Many of the barriers and facilitators overlapped with those experienced by other vulnerable groups, as shown in other studies.18,19,20,21,58,59 This was the first study to limit the search to dental care in the UK whilst extending the time period to encompass the last 50 years.

A key finding was that, over a 50-year period, many of the barriers and facilitators to accessing dental care had not in fact changed. For example, education and workforce issues surrounding training for geriatric dentistry were the same as studies mentioned 20 years previously.48 Almost half of the studies reported the lack of perceived need to see a dentist as a barrier to care. Whilst this may be interpreted as a call to educate older people as to the importance of visiting a dentist, it signifies that there is a discrepancy between older people's health needs and priorities and what the dental profession considers to be important for their health. This highlights the need for dental services to be co-produced by older people with the aim to meet older people's felt needs, rather than only considering normative need.54,59

In the last 50 years, the health and social care landscape has become increasingly dominated by neoliberal marketisation.60 Dental practices in the UK operate as small businesses, which ultimately must be profit-driven to succeed.61 Potential policy-level facilitators for care included the Disability Discrimination Act, which was later replaced by the Equality Act.38,62 However, later studies describe lack of wheelchair access as a continued barrier to attending dental practices physically despite these policies existing.41,46,53 Borreani et al.41,42proposed that the 2006 dental contract would reduce some barriers associated with cost of care. In reality, this led to confusion over the cost of treatment, increasing ‘fear of cost', whilst direct costs persisted as a barrier to attending dental care.41,46 Policymakers must consider how to commission and support dental services to accommodate older people so that practices are not financially disincentivised from seeing this population.

A limitation of the study was due to changes in terminology. One study was retrieved post hoc from the primary reviewer's own research knowledge, despite the original terms being supported by a librarian. Another limitation was that hand-searching and grey literature was not included despite an exploratory search revealing that guidelines do exist surrounding oral healthcare for older adults.1,15,16,63,64,65,66 This is an area which could be explored in the future; yet, notably, much of the existing guidance focuses on those in care homes or with dementia.

This scoping review highlighted multiple gaps in the literature (Box 2). There were not many studies available to assess barriers and facilitators to accessing dental care for people living in the community, particularly for those in the 85+ age group. Few of the studies in this review distinguished between the varying levels of frailty and privilege amongst older people. Studies who did define ‘older people' typically followed national census categories or historic retirement ages, despite the breadth of ages this could encompass.2,66 Furthermore, there was a lack of studies in the last 25 years on minority ethnic groups living outside of London, women and older people living in the devolved nations, especially Northern Ireland. Future studies could identify populations underrepresented in research and stratify cohorts according to age and/or dependency. To further explore barriers experienced by community-dwelling older adults as opposed to care home populations, research could include family members, informal carers and other health and social care professionals.

Multiple studies identified the beliefs and attitudes held by older people towards dentistry, particularly the factors which distinguished an older person from having positive rather than negative perceptions of dentists and oral health. Aspects which were identified but not explored in depth included negative media attention around dentistry, lack of dental health education of older people, culturally hostile healthcare services and dentists' varying attitudes towards older people. Research into these fields could provide insights into the development of more inclusive services.

Conclusion

In conclusion, many barriers and facilitators exist relating to older people's access to dental services. Future research is required to explore specific barriers and facilitators within the diverse subgroup of older people beyond those in care homes. Without addressing older people's needs now, the problem of access is likely to worsen as the ageing population grows.

Data availability

The data are available from the authors upon request.

References

UK Government. What is known about the oral health of older people in England and Wales. 2015. Available at https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/489756/What_is_known_about_the_oral_health_of_older_people.pdf (accessed November 2022).

Office for National Statistics. Population and household estimates, England and Wales: Census 2021. 2022. Available at https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates/bulletins/populationandhouseholdestimatesenglandandwales/census2021 (accessed November 2024).

Alpert P T. Oral Health: The Oral-Systemic Health Connection. Home Health Care Manag Pract 2016; 29: 56-59.

Ramsay S E, Whincup P H, Watt R G et al. Burden of poor oral health in older age: findings from a population-based study of older British men. BMJ Open 2015; 5: e009476.

NHS England. Adult Dental Health Survey 2009 - England Key Findings. 2011. Available at https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/adult-dental-health-survey/adult-dental-health-survey-2009-summary-report-and-thematic-series (accessed July 2024).

Steele J. NHS Dental Services in England - An Independent Review. 2009.

Age UK. State of the nation: older people and malnutrition in the UK today. 2017. Available at https://www.ageuk.org.uk/globalassets/age-uk/documents/programmes/malnutrition-taskforce/mtf_state_of_the_nation.pdf (accessed August 2023).

Tanaka T, Takahashi K, Hirano H et al. Oral Frailty as a Risk Factor for Physical Frailty and Mortality in Community-Dwelling Elderly. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2018; 73: 1661-1667.

Minakuchi S. Philosophy of Oral Hypofunction. Gerodontology 2022; 39: 1-2.

Zenthöfer A, Rammelsberg P, Cabrera T, Schröder J, Hassel A J. Determinants of oral health-related quality of life of the institutionalized elderly. Psychogeriatrics 2014; 14: 247-254.

Thomson W, Ma S. An ageing population poses dental challenges. Singapore Dent J 2014; 35: 3-8.

UK Government. Oral cancer in England: a report on incidence, survival and mortality rates of oral cancer in England, 2012 to 2016. 2020. Available at https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/891699/Oral_cancer_report_170420.pdf (accessed August 2023).

Matear D, Barbaro J. Caregiver puterspectives in oral healthcare in an institutionalised elderly population without access to dental services: a pilot study. J Royal Soc Prom Health 2006; 126: 28-32.

Care Quality Commission. Smiling matters: oral health in care homes. 2019. Available at https://www.cqc.org.uk/publications/major-report/smiling-matters-oral-health-care-care-homes (accessed March 2023).

National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Improving oral health for adults in care homes. 2018. Available at https://www.nice.org.uk/about/nice-communities/social-care/quick-guides/improving-oral-health-for-adults-in-care-homes (accessed March 2023).

Office for National Statistics. Changes in the Older Resident Care Home Population between 2001 and 2011. 2014. Available at https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/ageing/articles/changesintheolderresidentcarehomepopulationbetween2001and2011/2014-08-01 (accessed March 2023).

Slack-Smith L, Hearn L, Scrine C, Durey A. Barriers and enablers for oral health care for people affected by mental health disorders. Aust Dent J 2017; 62: 6-13.

El-Yousfi S, Jones K, White S, Marshman Z. A rapid review of barriers to oral healthcare for vulnerable people. Br Dent J 2019; 227: 143-151.

El-Yousfi S, Jones K, White S, Marshman Z. A rapid review of barriers to oral healthcare for people with protected characteristics. Br Dent J 2020; 228: 853-858.

Göstemeyer G, Baker S R, Schwendicke F. Barriers and facilitators for provision of oral health care in dependent older people: a systematic review. Clin Oral Invest 2019; 23: 979-993.

Legge A R, Latour J M, Nasser M. Older Patients' Views of Oral Health Care and Factors which Facilitate or Obstruct Regular Access to Dental Care-Services: A Qualitative Systematic Review. Community Dent Health 2021; 38: 165-171.

Nilsson A, Young L, Glass B, Lee A. Gerodontology in the dental school curriculum: A scoping review. Gerodontology 2021; 38: 325-337.

Ben-Omran M O, Livinski A A, Kopycka-Kedzierawski D T et al. The use of teledentistry in facilitating oral health for older adults. J Am Dent Assoc 2021; 152: 998-1011.

Chandel T, Alulaiyan M, Farraj M et al. Training and educational programs that support geriatric dental care in rural settings: A scoping review. J Dent Educ 2022; 86: 792-803.

Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005; 8: 19-32.

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien K K. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci 2010; 5: 69.

Joanna Briggs Institute. Appendix 11.1: JBI template source of evidence details, characteristics and results extraction instrument - JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. 2022. Available at https://jbi-global-wiki.refined.site/space/MANUAL/4687579 (accessed November 2022).

Moneyfarm. UK Retirement Age: Learn all you need to know about female and male retirement age in UK. 2024. Available at https://blog.moneyfarm.com/en/pensions/retirement-age-in-the-uk-when-can-you-retire-and-get-your-state-pension/ (accessed July 2023).

Grant M J, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Inf Libr J 2009; 26: 91-108.

Steele L. Provision of dental care for elderly handicapped people. A community dental officer's view. J R Soc Health 1984; 104: 208-209.

Hoad-Reddick G, Grant A A, Griffiths C S. Knowledge of dental services provided: investigations in an elderly population. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1987; 15: 137-140.

Tobias B, Smith J. Barriers to dental care, and associated oral status and treatment needs, in an elderly population living in sheltered accommodation in West Essex. Br Dent J 1987; 163: 293-295.

Diu S, Gelbier S. Oral health screening of elderly people attending a Community Care Centre. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1989; 17: 212-215.

Mattin D, Smith J. The oral health status, dental needs and factors affecting utilisation of dental services in Asians aged 55 years and over, resident in Southampton. Br Dent J 1991; 170: 369-372.

Merelie D L, Heyman B. Dental needs of the elderly in residential care in Newcastle-upon-Tyne and the role of formal carers. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1992; 20: 106-111.

Lester V, Ashley F P, Gibbons D E. Reported dental attendance and perceived barriers to care in frail and functionally dependent older adults. Br Dent J 1998; 184: 285-289.

Kwan S Y, Holmes M A. An exploration of oral health beliefs and attitudes of Chinese in West Yorkshire: a qualitative investigation. Health Educ Res 1999; 14: 453-460.

Fiske J. The delivery of oral care services to elderly people living in a noninstitutionalized setting. J Public Health Dent 2000; 60: 321-325.

Bell M, Davis D, Easterby-Smith V, Ellis J. National Working Group for Older People. Meeting the challenges of oral health for older people: a strategy review. Chapter 4: Dental services access and provision. Gerodontology 2005; 22: 16-22.

Lane E A, Gallagher J E. Role of the Single Assessment Process in the Care of Older People. How Will Primary Dental Care Practitioners be Involved? Prim Dent Care 2006; 13: 130-134.

Borreani E, Wright D, Scambler S, Gallagher J E. Minimising barriers to dental care in older people. BMC Oral Health 2008; 8: 7.

Borreani E, Jones K, Scambler S, Gallagher J E. Informing the debate on oral health care for older people: a qualitative study of older people's views on oral health and oral health care. Gerodontology 2010; 27: 11-18.

Austin R S, Olley R C, Ray-Chaudhuri A, Gallagher J E. Oral Disease Prevention for Older People. Prim Dent Care 2011; 18: 101-106.

Sullivan J. Challenges to oral healthcare for older people in domiciliary settings in the next 20 years: a general dental practitioner's perspective. Prim Dent Care 2012; 19: 123-127.

Beacher N, Sweeney M P. The Francis report - implications for oral care of the elderly. Dent Update 2015; 42: 318-323.

Patel R, Mian M, Robertson C, Pitts N B, Gallagher J E. Crisis in care homes: the dentists don't come. BDJ Open 2021; 7: 20.

Boneham M A, Williams K E, Copeland J R M et al. Elderly people from ethnic minorities in Liverpool: mental illness, unmet need and barriers to service use. Health Soc Care Community 2007; 5: 173-180.

Walls A W, Steele J G. Geriatric oral health issues in the United Kingdom. Int Dent J 2001; 51: 183-187.

Ahmad B, Landes D, Moffatt S. Dental Public Health In Action: Barriers to oral healthcare provision for older people in residential and nursing care homes: A mixed method evaluation and strategy development in County Durham, North East England. Community Dent Health 2018; 35: 136-139.

Aminu A Q. Adult Dental Health Survey 2009: association between oral health outcomes and living arrangements of older adults in the UK. Br Dent J 2019; 227: 115-120.

Hamilton F A, Sarll D W, Grant A A, Worthington H V. Dental care for elderly people by general dental practitioners. Br Dent J 1990; 168: 108-112.

Longhurst R H. Availability of domiciliary dental care for the elderly. Prim Dent Care 2002; 9: 147-150.

Doshi M, Lee L, Keddie M. Effective mouth care for older people living in nursing homes. Nurs Older People 2021; 33: 18-23.

Howells E P, Davies R, Jones V, Morgan M Z. Gwên am Byth: a programme introduced to improve the oral health of older people living in care homes in Wales - from anecdote, through policy into action. Br Dent J 2020; 229: 793-799.

Curtis S A, Scambler S, Manthorpe J, Samsi K, Rooney Y M, Gallagher J E. Everyday experiences of people living with dementia and their carers relating to oral health and dental care. Dementia 2021; 20: 1925-1939.

Sweeney M P, Williams C, Kennedy C, Macpherson L M D, Turner S, Bagg J. Oral health care and status of elderly care home residents in Glasgow. Community Dent Health 2007; 24: 37-42.

White V, Edwards M, Sweeney M, Macpherson L. Provision of oral healthcare and support in care homes in Scotland. J Disabil Oral Health 2009; 10: 99-106.

Prosser G M, Louca C, Radford D R. Potential educational and workforce strategies to meet the oral health challenges of an increasingly older population: a qualitative study. BDJ Open 2022; 8: 6.

Bradshaw J. Taxonomy of social need. In McLachlan G (ed) Problems and Progress in Medical Care. 7th ed. pp 71-82. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1972.

Dutta S J, Knafo S, Lovering I A. Neoliberal failures and the managerial takeover of governance. Rev Int Stud 202; 48: 484-502.

Toon M, Collin V, Whitehead P, Reynolds L. An analysis of stress and burnout in UK general dental practitioners: subdimensions and causes. Br Dent J 2019; DOI: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2019.46.

Government Equalities Office. Equality Act 2010: What do I need to know? Disability quick start guide. 2010. Available at https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a79c79940f0b66d161ae174/disability.pdf (accessed March 2023).

UK Government. Commissioning better oral health for vulnerable older people. 2018. Available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/commissioning-better-oral-health-for-vulnerable-older-people (accessed March 2023).

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Oral health for adults in care homes. 2016. Available at https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng48 (accessed July 2024).

UK Government. Oral health toolkit for adults in care homes. 2020. Available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/adult-oral-health-in-care-homes-toolkit/oral-health-toolkit-for-adults-in-care-homes (accessed July 2023).

Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman. Women's State Pension age: our findings on the Department for Work and Pensions' communication of changes. Available at https://www.ombudsman.org.uk/publications/womens-state-pension-age-our-findings-department-work-and-pensions-communication/background-relating-changes-state-pension-age-women (accessed September 2023).

General Dental Council. Standards For Education. 2015. Available at https://www.gdc-uk.org/docs/default-source/quality-assurance/standards-for-education-%28revised-2015%29.pdf (accessed July 2024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Anna Beaven: conception and design of study, data analysis, interpretation of data, drafting article, agreement for accountability. Zoe Marshman: conception and design of study, critically revising the work, final approval for publication, agreement for accountability

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

No ethical approval was needed for this study as it is a literature review and no human subjects were directly involved.

Rights and permissions

Open Access. This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0.© The Author(s) 2024.

About this article

Cite this article

Beaven, A., Marshman, Z. Barriers and facilitators to accessing oral healthcare for older people in the UK: a scoping review. Br Dent J (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-024-7740-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-024-7740-x

- Springer Nature Limited