Abstract

The postpartum period is a crucial starting point for the delivery of family planning services. To date, there are numerous primary studies in Ethiopia on postpartum contraceptive use and related factors. However, the results of key variables are inconsistent, making it difficult to use the results to advance the service dimensions of postpartum contraceptive use in the country. Therefore, this systematic review and meta-analysis was required to summarize this inconsistency and compile the best available evidence on the impact of maternal educational status, antenatal care and menstrual resumption on postpartum contraceptive use in Ethiopia. PubMed, Google Scholar, Scopus, Science Direct, and the repositories of online research institutes were searched. Data were extracted with Microsoft Excel and analyzed with the statistical software STATA (version 14). Data on the study area, design, population, sample size, and observed frequency were extracted using the Joanna Briggs Institute tool. To obtain the pooled effect size, a meta-analysis was performed using a weighted inverse variance random effects model. Cochran's Q X2 test, and I2 statistics were used to test for heterogeneity, estimate the total quantity, and measure the variability attributed to heterogeneity. A mixed-effects meta-regression analysis was performed to identify possible sources of heterogeneity. To examine publication bias, the Eggers regression test and the Beggs correlation test were used at a p-value threshold of 0.001. Of the 654 articles reviewed, 18 studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in this meta-analysis. Overall, the final analysis includes 11,263 study participants. In Ethiopia, postpartum contraceptive use correlated significantly with maternal educational status (OR = 3.121:95% CI 2.127–4.115), antenatal care follow-up (OR = 3.286; 95% CI 2.353–4.220), and return of the mother's menses (OR = 3.492; 95% CI 1.843–6.615). A uniform meta-regression was performed based on publication year (p = 0.821), sample size (p = 0.989), and city of residence (p = 0.104), which revealed that none of these factors are significant. The use of postpartum contraceptives was found to be better among mothers who are educated, attended antenatal appointments, and resumed their menstrual cycle. Based on our research, we strongly recommended that antenatal care use and maternal educational accessibility need to improve. For family planning professionals, removing barriers to menstruation resumption should be a key priority.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Introduction

Pregnancy and childbirth-related complications are the leading cause of death and morbidity in women of childbearing age1. It is estimated that 295,000 mothers died worldwide in 2017, 94% of which occurred in resource-constrained areas. When the majority of its causes are preventable, Sub-Saharan Africa accounts for about 66% of maternal deaths2. Ethiopia had a pregnancy-related maternal mortality rate of 412 per 100,000 live births3.

Family planning is widely recognized as a crucial strategy to prevent maternal and infant morbidity and mortality4. In countries with high birth rates, promoting family planning can prevent 32% of all maternal deaths and almost 10% of all child deaths5. The prevention of unplanned pregnancies and pregnancies in close succession within the first 12 months after birth is referred to as postpartum family planning (PPFP)6,7,8. This involves starting and using contraceptives in the first year after birth9. However, due to the low use of family planning in the postpartum period, there are 80 million unwanted pregnancies worldwide10. There is a 40% unmet need for family planning among postpartum mothers in sub-Saharan Africa11. Since two-thirds of maternal and neonatal mortality occur in the postpartum period12, timely family planning within one year of delivery can help prevent these adverse effects13,14.

Although 95% of women plan to delay pregnancy by at least two years, postpartum use of modern contraceptives varies significantly between countries, ranging from 73.5% in Zambia to 4% in Pakistan15,16,17. Studies in Ethiopia showed that the postpartum use of modern contraceptives varied between 80.2% in Addis Ababa and 10.2% in Dabat18,19.

There is evidence that around half (47%) of all pregnancies in Ethiopia occur within a short delivery interval of less than 24 months20. Chronic malnutrition, stunted growth, miscarriage, stillbirth, artificial abortion, prematurity, low birth weight, and neonatal and maternal death are all associated with short gestational intervals21,22,23,24,25,26. The World Health Organization (WHO) therefore suggested that there should be 24 months between each subsequent pregnancy27. Short birth intervals28 and low use of contraceptives22 are said to contribute to an increased number of unwanted pregnancies in Ethiopia. According to research, 21% of the births took place at short intervals of less than 24 months; the remaining 35% took place between 24 and 35 months28. The postpartum period is crucial in this situation, particularly for starting contraception and healthy spacing between births29,30,31.

Since 2002, the Ethiopian government has encouraged and expanded the community-based delivery of family planning services to women on their doorstep as part of its health extension program32. Despite these initiatives, there is still a significant (86%) unmet need for contraception in women after childbirth33. Because it enables women to space birth properly, addressing the contraceptive problem in the postpartum period has a positive impact on maternal, newborn, infant, and child health survival34.

The woman's menstruation and resumption of sexual activity, inability to predict fertility resumption, level of education, and utilization of PPFP counseling are some factors influencing postpartum use19,35,36.

Recent meta-analysis studies revealed that the national pooled prevalence of post-partum contraceptive use in Ethiopia ranged from 45.44% to 45.7%37,38.Although the previous meta-analysis studies were conducted in Ethiopia, for the most part they failed to demonstrate an association between important variables and contraceptive use after childbirth. In addition, the results for key variables are inconsistent, making it difficult to apply the results to the promotion of postpartum contraceptive use in the country's service sector. It was necessary to pool this inconsistency and summarize the best available data on the effects of maternal educational status, prenatal care and menstrual resumption on postpartum contraceptive use in Ethiopia. The results of this study will provide program planners and policymakers with scientific evidence for service improvement. In addition, it helps healthcare professionals by providing scientific insights for practice.

Methods

Data synthesis and reporting

We analyzed the data based on a single measurement result (use in postpartum family planning). The results are presented using a forest plot, text, and tables. This systematic review and meta-analysis study was conducted to determine the effects of maternal educational status, antenatal care, and menstrual resumption on the use of postpartum family planning in Ethiopia using the standard PRISMA checklist guideline39 (Supplementary File 1). The protocol of this systematic review and meta-analysis has been registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO), registration number CRD42022357519: Available from: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/displayrecord.php?ID=CRD42022357519.

Search strategy

We considered using adapted PICO questions, i.e., the "PEO" (Population, Exposure, Outcome) format was followed, for explicit presentation of our review question and explicit clarification of the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The following keywords and phrases and/or Medical Subject Headings (MeSH), which were combined using the Boolean operators "OR" and "AND," served as the basis for these queries:

PECO guide

Population.

All postpartum mothers within up to 12 months of delivery.

Exposure.

Maternal educational status, resumption of menses, and antenatal care visit (at least one visit).

Comparison.

No formal education, no antenatal care visit, and no resumption of menses.

Outcome.

Postpartum contraceptive utilization.

We developed the following review question using the above modified PICO format, to identify as many relevant primary studies as possible:

Review question

"What is the effect of maternal educational status, antenatal care, and resumption of menses on postpartum contraceptive use during the postpartum period in Ethiopia?".

Thereafter, primary studies on the effect of maternal educational status, prenatal care, and return of menstruation on the use of family planning after childbirth in Ethiopia were searched using Google Scholar, Science Direct, Scopus, EMBASE, and PubMed using the review questions mentioned above. The Bepress legal repository and the Social Science Research Network (SSRN) were our best sources for finding unpublished articles and papers. Therefore, we retrieved gray literature from the Addis Ababa University institutional research repository. The search was conducted using the following keywords and search terms “Contraception”, “Family planning”, “Contraceptive”, “Utilization”, “Use”, “Postpartum mothers”, “Postpartum period”, “Post-delivery”, “Puerperal period”, “Antenatal care”, “Educational status”, “Literacy”, “Returning of menses”, “Resumption of menses”, and “Ethiopia”. The search terms were used individually and in combination with Boolean operators such as “OR” or “AND”. The search was conducted from June 1, 2022, to July 4, 2022.

Study outcome

The use of family planning services to prevent close and unintended births within the first year after birth is referred to as postpartum contraception40.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Only studies from Ethiopia that examined the prevalence of postpartum use of modern contraceptives and its determinants were included in this review. Research and screenings were conducted for both previously published and unpublished articles. All types of observational studies (cross-sectional studies, case–control studies, and cohort studies) have been discussed in this article. In addition, articles published only in English and for which the full text was available were also included. All studies that had been published in the form of journal articles, master's theses, or dissertations by the time the data analysis was completed were included. Therefore, studies that provided data on the association between postpartum family planning and maternal educational status or the association between postpartum contraceptive use and antenatal care, or the association between menstrual resumption and postpartum contraceptive use were included. We excluded works with duplicate reports, studies with qualitative research designs, and studies from other countries. This study used the COCOPOP (Condition, Context, and Population) framework to assess the adequacy of included articles. The study population (POP) consisted of postpartum women; the condition (CO) was the effect of maternal literacy, prenatal care, and menstrual resumption on the use of modern postpartum contraception, and the context (CO) included only studies conducted in Ethiopia.

Quality assessment

Two authors (NAG and KDT) independently assessed the standard of the studies using the standardized quality assessment checklist of the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI)41. The disagreements raised during the quality assessment were resolved through a discussion led by the third author (MW). Eventually, the dispute was settled and an agreement was reached. The critical analysis checklist contains eight parameters with the options Yes, No, Unclear, and Not Applicable. The parameters address the following questions: (1) Where were the criteria for inclusion in the sample clearly defined? (2) Were the study participants and thus the environment described in detail? (3) Was the exposure measurement result valid and reliable? (4) Were the main objective and standard criteria used to measure the event? (5) Were confounding factors identified? (6) Were strategies given to influence confounding factors? (7) Were the outcomes actually and reliably measured? And (8) Was the statistical analysis appropriate? Studies were considered low-risk if they scored 50% or more on the quality assessment indicators, as indicated in a supplemental file (Supplementary File 2).

Risk of bias assessment

The bias assessment tool developed by Hoy et al.42, which consists of 10 items and measures four bias domains as well as internal and external validity, was used by two authors (NAG and KDT) to independently assess the risk of bias in the included studies. Any disagreements that arose during the risk of bias assessment were resolved through a discussion led by the third author (MW). Eventually, the dispute was settled and an agreement was reached. The first four items (items 1 to 4) assess the presence of selection bias, non-response bias, and external validity. The other six items (items 5–10) assess the presence of a measure of bias, analysis-related bias, and internal validity. Therefore, studies that answered "yes" to eight or more of the ten questions were classified as having a low risk of bias. If studies that received yes to six to seven of the ten questions were classified as moderate risk, studies that received yes to five or fewer of the ten questions were classified as high risk, as reported in a supplemental file (Supplementary File 3).

Data extraction

Microsoft Excel spreadsheet (2016) and STATA software version 14 were used for data extraction and analysis. Visual inspection and double entry were used to assess the accuracy of the data entered into Excel spreadsheets. The data checker visually examines the entries and compares them with the original paper sheets. In a partner read-aloud, one author reads the paper data sheets aloud while the other author reviews the entries. In double entry, the data checker enters the data a second time; the computer compares the first and second entries to make sure they match and also identifies values that are outside the permitted range. Two authors (NAG and MWM) independently extracted all relevant data using a standardized data extraction format from the Joanna Briggs Institute. The disagreements raised during the data extraction were resolved through a discussion led by the third author (KDT). Eventually, the dispute was settled and an agreement was reached. The data automation tool was used due to the lack of a paper form (manual data) in this study. The first author's name, year of publication, study region, study setting, study design, sample size, the unadjusted odd ratio for factors (educational status, antenatal care, and menstrual resumption), and the quality of each paper was extracted.

Data analysis

After extraction of all relevant results in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet, the data were exported to STATA software version 14 for analysis. To obtain a pooled OR, a meta-analysis was performed using a weighted inverse variance random effects model. In addition, a cumulative meta-analysis was performed to illustrate the trend of evidence regarding the impact of maternal educational status, prenatal care, and menstrual resumption on postpartum family planning. To get the publication bias under control, the trim-and-fill approach was adopted by Duval and Tweedies43. To test for heterogeneity, estimate the degree of total/residual heterogeneity, and measure variability due to heterogeneity, Cochran's Q X2 test and I2 statistic were used44. Study area, sample size, and variations in the year of publication were examined for their effects on heterogeneity between studies using a univariate meta-regression analysis45.

Patient and public involvement

The authors (NA and KD) collaborated with public health experts and researchers from previous studies to design the research questions and outcome metrics. Patients and study participants were not involved in the design or analysis of the study as it was a systematic review and meta-analysis based on published data. The results of this study will be shared with patients and study participants through health education about the factors affecting contraceptive use after childbirth and dissemination of key findings through leaflets in the local language.

Results

Search results

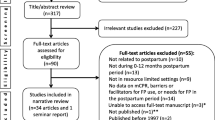

In total, we obtained 654 articles from international online databases (PubMed, Scopus, EMBASE, Science Direct, and Google Scholar) and gray literature from the Addis Ababa University repository. After removing duplicate studies, we received 503 studies that were selected for full title and abstract screening. Of these, 340 studies were excluded based on title and abstract, and the remaining 154 articles were assessed as full-text articles. Subsequently, 136 articles were excluded for other reasons after checking the full text. Finally, 1835,36,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61 studies met the inclusion criteria and were used in this meta-analysis: 8 studies48,50,53,54,55,56,57,58 examined the association between ANC attendance and PPFP use, 9 studies35,36,46,47,48,49,50,51,52 reported the association between maternal educational status and PPFP use, while 12 studies35,36,46,50,51,52,53,57,58,59,60,61 reported the association between menstrual resumption and PPFP use. The PRISMA diagram flowchart for the item selection process is shown in Fig. 1. In this meta-analysis, a study could report more than one outcome measure or related factors.

Study characteristics

As shown in Table 1, 18 studies reported the association between ANC attendance, maternal educational status, menstrual resumption, and postpartum family planning in 11,263 mothers. Of these studies, five were conducted in the Amhara region36,49,51,58,60; five in Southern Nations Nationalities and Peoples (SNNPR) regions36,48,51,58,60, three in the Oromia region52,54,56, two in Tigray region35,55, two in Addis Ababa53,61 and a study is being carried out at national level48. All included studies were conducted using a cross-sectional study design. Fourteen studies were community-based studies, while the remaining four studies were health facility studies. Fifteen studies were conducted in mothers within the previous 12 months, while three studies were conducted in mothers six weeks after delivery. The sample size ranged from 248 to 2304. All studies were assessed using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Quality Assessment Checklist and found to be low risk.

Meta-analysis

Postpartum family planning utilization in Ethiopia

Of the 18 studies included, 9 studies reported the association between maternal educational status and the use of family planning after childbirth in 5951 mothers (Table 1). The pooled odds ratio for maternal educational status was 2.108 (95% CI 1.097–3.710), I2 = 84.4%, p = 0.000 (Fig. 2). There is a funnel plot asymmetry in visual observation (Fig. 3). We also ran Eggers' regression test and Beggs' correlation test, which gave p = 0.049 and p = 0.037, respectively. Since significant publication was found, we performed a Duval and Tweedie trim-and-fill analysis and calculated a new effect size for maternal educational status (OR = 3.121, 95% CI 2.127–4.115), I2 = 90 0.2% after inclusion of imputed studies (i.e. estimated number of missing studies = 4) (Fig. 4). Therefore, mothers with an elementary or higher education were three times more likely to engage in postpartum family planning than mothers with no formal education.

Eight studies reported the association between antenatal visits and the use of family planning after childbirth in 6442 mothers. The pooled odds ratio for antenatal visits was 4.340 (95% CI 3.157–5.966), I2 = 60.8%, P = 0.378 (Fig. 5). The funnel plot shows an asymmetric distribution of the studies (Fig. 6). Because Egger's test (p = 0.024) and Begg's test (p = 0.032) showed significant publication bias, we performed Duval and Tweedie trim-and-fill analysis and calculated a new effect size for visits to the antenatal care (OR = 3.286, 95%). CI 2.353–4.220), I2 = 73.2% after inclusion of imputed articles (i.e. estimated number of missing studies = 5) (Fig. 7). Thus, mothers who had at least one and above antenatal care visit were 3 times more likely to utilize postpartum family planning as compared to mothers who had no antenatal care visit.

Twelve studies in 6059 mothers showed an association between the return of menstruation and the use of family planning after childbirth. The pooled odds ratio for menstrual resumption was 3.492 (95% CI 1.843–6.615), I2 = 93.9%, P = 0.000 (Fig. 8). The funnel chart shows a symmetrical distribution of the studies (Fig. 9). The Egger test (p = 0.312) and the Begg test (p = 0.533) also showed no evidence of publication bias. As a result, the odds of postpartum family planning use were 3.5 times higher among women who had resumption of menses than their counterparts. We also conducted a Univar ate meta-regression by considering the year of publication, sample size, and residence in Ethiopia as covariates to identify the possible sources of heterogeneity, and unfortunately, none was found to be statistically significant (Table 2).

Discussion

Mothers can begin family planning methods in the postpartum period, although this is typically a crucial window to seek family planning services28,62. One of the proposed public health interventions to reduce maternal and child morbidity and mortality rates is postpartum family planning services63,64. The Ethiopian Health Sector Transformation Plan (EHSTP)65 and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)66 on maternal and child health can both be achieved by identifying the factors affecting the availability of postpartum family planning strategies during the postnatal period affect phase. Therefore, the purpose of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to assess the impact of maternal educational status, prenatal care follow-up, and menstrual resumption on postpartum family planning engagement in Ethiopia. The main findings were that the use of family planning after childbirth was significantly associated with maternal educational status, follow-up for prenatal care, and women's resumption of menses after childbirth.

In contrast to mothers who experienced amenorrhea after childbirth, our data showed that mothers who resumed their menstrual cycle were significantly more likely to engage in family planning after childbirth. This is consistent with studies conducted in Malawi, Nepal, India, Malawi, and Nigeria67,68,69 and with Demographic Health Survey analyses from 27 different countries70. Studies with meta-analyses conducted in Ethiopia38 and in low- and middle-income countries70 also supported this judgment. This could be because women feel more vulnerable to unwanted pregnancies after their periods return. As a result, they are more likely to start using postpartum contraceptives. Knowing that a woman will ovulate before her first period after childbirth may also contribute to pregnancy32,71 and provides further support for this conclusion.

We also found that mothers who had at least one prenatal visit were three times more likely to use contraception after childbirth than mothers who did not. This conclusion is consistent with research from Ethiopia38, results from 17 countries for USAID70, Mexico72, India73, and Bangladesh74, results from 17 countries for USAID70, and an Ethiopian meta-analysis study38. This may be because women who received ANC were more likely to have access to information about birth spacing and the risks of a short birth for both mother and child. In addition, antenatal visits provide an opportunity to engage clients and providers in counseling sessions, which helps improve health-focused behaviors and contraceptive use.

Finally, we have shown that maternal educational status is significantly correlated with postpartum family planning use, consistent with other research from India75, Uganda76, Ghana74, and meta-analysis studies from Ethiopia37 countries with low and middle income76. As mothers become more educated, they may be more likely to seek medical care, understand the pros and cons of contraception, and have access to accurate information about fertility and contraception. Therefore, strengthening maternal education helps empower women to make informed decisions about their fertility and promotes the health of mothers and their children.

The PRISMA guidelines for literature searches were used to conduct this meta-analysis. In addition, the Egger statistical regression test and the Begg correlation test were used to calculate publication bias. We used the Joanna Briggs Institute Quality Assessment Checklist. The data may be useful for aspiring researchers, family planning specialists, and healthcare decision-makers as it is the first study of its kind in Ethiopia. Another benefit of this meta-analysis is that it includes both published and unpublished studies. In addition, this study has shortcomings. Because all included studies were observational, there is less solid evidence of a causal relationship. The risk of overlooking relevant research cannot be eliminated, even though we used extensive search tactics and the result may not be nationally representative.

Several analyses show significant differences between studies when using the traditional heterogeneity test approach. A meta-regression analysis was used to carefully analyze the course of heterogeneity. Because the research region, sample size, and year of publication varied, caution should be exercised when interpreting the results. In addition, the dose–response relationship between the frequency of ANC visits and use for postpartum family planning has not been investigated. Research has reported the association between maternal educational status, ANC attendance, and use of family planning after childbirth, however, significant publication bias was also found in these studies. To correct for publication bias and provide an unbiased estimate, we performed a Duval and Tweedie trim-and-fill analysis; however, the result should be interpreted with caution.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we found that mothers who are educated, have attended antenatal care, and have resumed their menstrual cycle are more likely to use postpartum contraception. We strongly advocated for increased access to maternal education and antenatal care follow-up service. Additionally, overcoming menstrual cycle problems is the top priority for family planning providers.

Implications of the findings

The impact of the study on various scientific communities and the general public is as follows it is based on secondary data. Ethiopia and other developing countries have low rates of postpartum contraceptive use. This study suggests that maternal educational level, prenatal care, and the return of menstruation have an impact on postpartum contraceptive use. The results of this study, therefore, encourage researchers to conduct further, more detailed investigations to determine the association between postpartum contraceptive use and other characteristics not considered in this analysis. The third conclusion of this study is that as the use of postpartum family planning services increases, the leading causes of maternal deaths—unintended pregnancies, short-term pregnancies, unsafe abortions, and other maternal morbidity—will decrease.

Data availability

All relevant data are within the Manuscript and its Supporting Information files.

Abbreviations

- OR:

-

Odd ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- PPFP:

-

Postpartum family planning

References

WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, Group WB, Division at UNP. Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2015.2015.

Trends in maternal mortality 2000 to 2017: estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group, and the United Nations Population Division. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO

Central Statistical Agency (CSA) [Ethiopia] and ICF. 2016. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2016. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: CSA and ICF.

World Health Organization. Postnatal Care of the Mother and Newborn (World Health Organization, 2014).

Cleland, J. et al. Family planning: The unfinished agenda. Lancet (London, England) 368(9549), 1810–1827 (2006).

World Health Organization. Programming strategies for postpartum family planning 2013: 9–56.

International Pathfinder. Expanding contraceptive options for postpartum women in Ethiopia: Introducing the postpartum IUD 2016.

USAID, Australian AID, Jhpiego, IPPF, Save the Children, et al. Statement for collective action for postpartum family planning: 1–2.

Sarvamangala, K. & Taranum, A. Menstrual pattern, sexual behavior and contraceptive use among postpartum women in a tertiary care hospital in Davangere. Medica Innov. 2, 61–66 (2013).

Federal Ministry of Health. National Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights (SRHR) Policy. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; 2009. https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/SRHR_an_essential_element_of_UHC_SupplementAndUniversalAccess_27-online.pdf. (Accessed 20 March 2018).

WHO, USAID. Repositioning Family Planning: Guidelines for Advocacy Action. Journal of Reproductive Health. 2010. https://toolkits.Knowledgesuccess.org/sites/default/files/RFP_English.pdf. (Accessed 20 January 2017).

Matisavich, A. & Santos, M. Inequalities in maternal postnatal visits among public and private patients. BMC Public Health 9, 335. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-9-335 (2009).

Mathe, J. K., Kasonia, K. K. & Maliro, A. K. Barriers to adoption of family planning among women in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. Afr. J. Reprod. Health 15, 69–78 (2011).

Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Best practice in postpartum family planning. London England; 2015;1:1–2. https://www.rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/guidelines/best-practice-papers/best-practice-paper-1—postpartum-family-planning.pdf. (Accesed 20 March 2018).

Pasha, O. et al. Postpartum contraceptive use and unmet need for family planning in five low-income countries. Reprod. Health 12(2), S11 (2015).

Borda M, Winfrey W. Postpartum fertility and contraception: an analysis of findings from 17 countries. Baltimore: Jhpiego; 2010.

Rutaremwa, G. et al. Predictors of modern contraceptive use during the postpartum period among women in Uganda: A population-based cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 15(1), 262 (2015).

Gebremedhin, A. Y. et al. Family planning use and its associated factors among women in the extended postpartum period in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Contracept. Reprod. Med. 3(1), 1–8 (2018).

Mengesha, Z. B., Worku, A. G. & Feleke, S. A. Contraceptive adoption in the extended postpartum period is low in Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 15(1), 160 (2015).

US Agency for International Development. Family planning needs during the first two years postpartum in Ethiopia [cited 2017 Mar 31]. https://www.k4health.org/sites/default/files/ethiopia_2011_dhs_reanalysis_for_ppfp_final.pdf.

Cleland, J., Conde-Agudelo, A., Peterson, J., Ross, J. & Tsui, A. Contraception and health. Lancet 380(9837), 149–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60609-6 (2012).

Conde-Agudelo, A., Rosas-Bermudez, A. & Kafury-Goeta, A. C. Maternal morbidity and mortality associated with inter-pregnancy interval. BMJ 321(1255), 721–728 (2000).

DaVanzo, J., Hale, L., Razzaque, A. & Rahman, M. Effects of interpregnancy interval and outcome of the preceding pregnancy on pregnancy outcomes in Matlab, Bangladesh. BJOG 114(9), 1079–1087. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01338.x (2007).

Rutstein SO. Further evidence of the effects of preceding birth intervals on neonatal, infant, and under-five-years mortality and nutritional status in developing countries: evidence from the Demographic and Health Surveys.: Macro International USAID 2008

DaVanzo, J., Hale, L., Razzaque, A. & Rahman, M. Effects of interpregnancy interval and outcome of the preceding pregnancy on pregnancy outcomes in Matlab, Bangladesh. Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 114(9), 1079–1087 (2007).

Wendt, A., Gibbs, C. M., Peters, S. & Hogue, C. J. Impact of increasing inter-pregnancy interval on maternal and infant health. Paediatr. Perinatal Epidemiol. 26, 239–258 (2012).

Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, Ministry of Health. Health Sector Development Programme IV: 2010/11 – 2014/15. Addis Ababa, 2010

Thomas, B., Richard, J. & Mary, S. Efficacy of a New postpartum transition protocol for avoiding pregnancy. Am. Board Fam. Med. 26, 35–44 (2012).

Subhi, R., Ahmed, H. & Mawlood, Z. Spacing effects on maternal-child health. Tikrit Med. J. 17(2), 1–6 (2011).

USAID MCHIP. Family planning needs during the first two years postpartum in Ethiopia. Washington DC: USAID; 2013

Aurellie, B., Elizabeth, E., Ngabo, F., Wesson, J. & Chen, M. Getting to 70%: Barriers to modern contraceptive use for women in Rwanda. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 123, 11–15 (2013).

Barber, L. Family planning advice and postpartum contraceptive use among low-income women in Mexico. Int. Fam. Plan. Perspect. 33(1), 6–12 (2007).

World health organization. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use 4th edn. (World health organization, 2010).

Ellen, K., Christina, I. & Helen, P. Postpartum contraceptive use among adolescent mothers in seven states. J. Adolesc. Health 52(3), 278 (2013).

Abraha, T. H., Teferra, A. S. & Gelagay, A. A. Postpartum modern contraceptive use in northern Ethiopia: Prevalence and associated factors. Epidemiol. Health 39, e2017012 (2017).

Ashebir, W. & Tadesse, T. Associated factors of postpartum modern contraceptive use in Burie District, Amhara Region, Ethiopia. J. Pregnancy https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/6174504 (2020).

Wakuma, B. et al. Postpartum modern contraception utilization and its determinants in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 15(12), e0243776. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0243776 (2020).

Tesfu, T. A. et al. Uptake of postpartum modern family planning and its associated factors among postpartum women in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heliyon 8, e08712 (2022).

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., The PRISMA Group. The preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 6(7), e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed1000097 (2009).

Gaffield, M. E., Egan, S. & Temmerman, M. It’s about time: WHO and partners release programming strategies for postpartum family planning. Glob. Health Sci. Pract. 2(1), 4–9 (2014).

Moola S, Munn Z, Tufanaru C, Aromataris E, Sears K, Sfetcu R, et al. Checklist for analytical cross-sectional studies. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer's Manual. 2017. Available from: JBI critical appraisal checklist for analytical cross-sectional Studies 2017

Hoy, D. et al. Assessing risk of bias in prevalence studies: Modification of an existing tool and evidence of inter-rater agreement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 65(9), 934–939 (2012).

Duval, S. & Tweedie, R. Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics 56, 455–463 (2000).

Higgins, J. P. & Thompson, S. G. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat. Med. 21, 1539–1558 (2002).

Viechtbauer, W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metaphor Package. J. Stat. Softw. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v036.i03 (2010).

Gejo, N. G., Anshebo, A. A. & Dinsa, L. H. Postpartum modern contraceptive use and associated factors in Hossana town. PloS One 14(5), e0217167. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0217167 (2019).

Wassihun, B. et al. Prevalence of postpartum family planning utilization and associated factors among postpartum mothers in Arba Minch town, South Ethiopia. Contracept. Reprod. Med. 6, 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40834-021-00150-z (2021).

Dagnew, G. W. et al. Modern contraceptive use and factors associated with use among postpartum women in Ethiopia; further analysis of the 2016 Ethiopia demographic and health survey data. BMC Public Health 20, 661. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-08802-6 (2020).

Getachew Andualem Belete, Almaz Aklilu Getu and Getahun Belay Gela. Utilization and associated factors of modern contraceptives during the postpartum period among women who gave birth in the last 12 months in injibara town Awi Zone, North-West Ethiopia 2019

Abate, Z. G. & Obsie, G. W. Early postpartum modern family planning utilization and associated factors in Dilla Town, Sothern Ethiopia; 2019. J. Womens Health Gyn. 8, 1–9 (2021).

Mihret, N. et al. Postpartum modern contraceptive utilization and associated factors among women who gave birth in the last 12 months in Addis Zemen, South Gondar, Ethiopia: Community-based cross-sectional study. Int. J. Women’s Health 12, 1241–1251 (2020).

Niguse, S. G. et al. Contraceptive use and associated factors among women in the extended postpartum period in Dello Mena District, Bale Zone, Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Res. Stud. Med. Health Sci. 4(12), 11–24 (2019).

Tafa, L. & Worku, Y. Family planning utilization and associated factors among postpartum women in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. PLoS ONE 16(1), e0245123. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0245123 (2021).

Teka, T. T. et al. Role of antenatal and postnatal care in contraceptive use during the postpartum period in western Ethiopia: A cross sectional study. BMC Res. Notes 11, 581. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-018-3698-6 (2018).

Abraha, T. H. et al. Predictors of postpartum contraceptive use in rural Tigray region, northern Ethiopia: A multilevel analysis. BMC Public Health 18, 1017. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5941-4 (2018).

Bushura Nugussa, Tesfaye Solomon and Hailu Tadelu. Utilization of modern contraceptive methods and associated factors among postpartum women in Ambo rural district, Ethiopia, 2021: A cross-sectional study Posted Date: June 16th, 2022. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-1710384/v1

Mahlet Getachew. Assessment of Postpartum Contraceptive Adoption And Associated Factors In Butajira Health And Demographic Surveillance Site (Hdss), In Southern Ethiopia, June 2015.

Abera, Y., Mengesha, Z. B. & Tessema, G. A. Postpartum contraceptive use in Gondar town, Northwest Ethiopia: A community based cross-sectional study. Women Health https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-015-0178-1 (2015).

MesfinYesgat, Y. et al. Extended post-partum modern contraceptive utilization and associated factors among women in Arba Minch town, Southern Ethiopia. PLoS ONE 17(3), e0265163. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0265163 (2022).

Demie, T. G., Demissew, T., Huluka, T. K., Workineh, D. & Libanos, H. G. Postpartum family planning utilization among postpartum women in public health institutions of Debre Berhan town, Ethiopia. J. Women Health Care https://doi.org/10.4172/2167-0420.1000426 (2018).

Gebremedhin, A. Y., Kebede, Y., Gelagay, A. A. & Habitu, Y. A. Family planning use and its associated factors among women in the extended postpartum period in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Contracept. Reprod. Med. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40834-017-0054-5 (2018).

Jhpiego. Postpartum Intrautraine cContraceptiveDevice (PPIUD) services Family planning intiative. Maryland, USA: Jhpiego; 2010.

McKaig, C. & Chase, R. Postpartum Family Planning Technical Consultation—Meeting Report (JHPIEGO, 2007).

Gaffield, M. E., Egan, S. & Temmerman, M. It’s about time: WHO and partners release programming strategies for postpartum family planning. Glob. Health Sci. Prac. 2(1), 4–9 (2014).

United Nations. The sustainable development goals report, New York. 2016.

Sarvamangala, K. & Taranum, A. Menstrual pattern, sexual behavior and contraceptive use among postpartum women in a tertiary care hospital in Davangere. Med. Innov. 2(2), 175 (2013).

Joshi, A. K. et al. Utilization of family planning methods among postpartum mothers in Kailali district, Nepal. Int. J. Womens Health 12, 487. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S249044 (2020).

Bwazi, C., Maluwa, A., Chimwaza, A. & Pindani, M. Utilization of postpartum family planning services between six and twelve months of delivery at Ntchisi District hospital. Malawi Health https://doi.org/10.4236/health.2014.614205 (2014).

Borda, M. R., Winfrey, W. & McKaig, C. Return to sexual activity and modern family planning use in the extended postpartum period: An analysis of findings from seventeen countries. Afr. J. Reprod. Health 14(4), 72–79 (2010).

Moore, Z. et al. Missed opportunities for family planning: An analysis of pregnancy risk and contraceptive method use among postpartum women in 21 low- and middle-income countries. Contraception 92, 31–39 (2015).

Dev, R. et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of postpartum contraceptive use among women in low- and middle-income countries. Reprod. Health 16, 154 (2019).

Tisha, S., Haque, S. R. & Tabassum, M. Antenatal care, an expediter for postpartum modern contraceptive use. Res. Obstet. Gynecol. 3(2), 22–31 (2015).

Rutaremwa, G. et al. Predictors of modern contraceptive use during the postpartum period among women in Uganda: A population-based cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 15(1), 262. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1611-y (2015).

Apanga, P. A. & Adam, M. A. Factors influencing the uptake of family planning services in the Talensi District, Ghana. Pan Afr. Med. J. https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2015.20.10.5301 (2015).

Ujah, O. I., Ocheke, A. N., Mutihir, J. T., Okopi, J. A. & Ujah, I. A. O. Postpartum contraception: Determinants of intention and methods of use among an obstetric cohort in a tertiary hospital in Jos, North Central Nigeria. Int. J. Reprod. Contracept. Obstet. Gynecol. 6, 5213–5218 (2017).

Rubee Dev, P. K., Feder, M., Unger, J. A., Woods, N. F. & Drake, A. L. A systematic review and meta-analysis of postpartum contraceptive use among women in low- and middle-income countries. Reprod. Health 16, 154 (2019).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.A.G. conceptualized the study: N.A.G. and K.D.: contributed during data extraction and analysis: N.A.G. and K.D.T. wrote result interpretation: N.A.G. and K.D.T., Prepared the first draft: N.A.G., M.W.K., and K.D.T. Revised and finalized the final draft manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gebeyehu, N.A., Tegegne, K.D. & Kassaw, M.W. The effect of maternal educational status, antenatal care and resumption of menses on postpartum contraceptive use in Ethiopia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 13, 12655 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-39719-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-39719-w

- Springer Nature Limited