Abstract

Tuberculosis (TB) preventive treatment (TPT) effectively prevents the progression from TB infection to TB disease. This study explores factors associated with TPT non-completion in Cambodia using 6-years programmatic data (2018–2023) retrieved from the TB Management Information System (TB-MIS). Out of 14,262 individuals with latent TB infection (LTBI) initiated with TPT, 299 (2.1%) did not complete the treatment. Individuals aged between 15–24 and 25–34 years old were more likely to not complete the treatment compared to those aged < 5 years old, with aOR = 1.7, p = 0.034 and aOR = 2.1, p = 0.003, respectively. Individuals initiated with 3-month daily Rifampicin and Isoniazid (3RH) or with 6-month daily Isoniazid (6H) were more likely to not complete the treatment compared to those initiated with 3-month weekly Isoniazid and Rifapentine (3HP), with aOR = 2.6, p < 0.001 and aOR = 7, p < 0.001, respectively. Those who began TPT at referral hospitals were nearly twice as likely to not complete the treatment compared to those who started the treatment at health centers (aOR = 1.95, p = 0.003). To improve TPT completion, strengthen the treatment follow-up among those aged between 15 and 34 years old and initiated TPT at referral hospitals should be prioritized. The national TB program should consider 3HP the first choice of treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Introduction

Latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) is a condition in which a person has been infected with the tuberculosis (TB) bacteria but does not have any symptoms of TB disease1. It is estimated that about 25% of the world’s population is infected with TB2. Tuberculosis preventive treatment (TPT), a course of antibiotics, is an effective intervention for preventing the progression from LTBI to TB disease and it is one of the key interventions recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) to achieve the End TB Strategy targets3. The United Nations High-Level Meeting on Tuberculosis in 2018 set a target to initiate TPT for 30 million people between 2018 and 2022. However, as of 2022, only 15.5 million people, or 52% of the target, had received TPT4.

Non-completion of TB prophylaxis among people with LTBI is influenced by a number of factors. A case control study in Brazil found that drug use, TB treatment default by the index case and drug intolerance were significantly associated with TPT non-completion5. In Portugal, treatment failure of TB infection was associated with those older than 15 years old, born outside Portugal, having a chronic disease, alcohol drinking, intravenous drug user, and using 3RH6. For children and adolescents, failure to complete 9-month TB prophylaxis with isoniazid included those aged 15–18 years old, non-Hispanic participants, development hepatitis, and isoniazid side effects7. Drug side effects, transportation issues and conflicts with working schedule or travel plan were found as factors associated with TPT non-completion among Vietnamese immigrants in Southern California8. In Japan, drug side effects and non-Japanese born LTBI were found as risk factors for LTBI treatment failure9.

Cambodia is a country with a high burden of TB, with an estimated of 320 new cases of TB cases per 100,000 people in 202210. The estimation of LTBI’s proportion in Cambodia is higher than global average11. The National LTBI guidelines in Cambodia prioritizes several high-risk groups for LTBI management. These include people living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) irrespective of CD4 cell count and antiretroviral therapy status, all HIV-negative close contacts of individuals with bacteriologically confirmed pulmonary tuberculosis (TB) following an exposure risk assessment, and immunocompromised persons12. Based on the guideline, the national TB program recommends three TPT regiments including six months of daily Isoniazid (6H), three months of weekly Isoniazid and Rifapentine (3HP), and three months of daily Rifampicin and Isoniazid (3RH)13. Eligibility criteria for TPT include the absence of TB disease and the absence of contraindications (acute and chronic hepatitis, regular and heavy alcohol consumption, and symptoms of peripheral neuropathy)14. Those eligible for TPT are assessed by trained healthcare providers in accordance with the national guideline. TB disease screening are done based on the following TB symptoms: current cough, fever, unexplained weight loss, night sweats, lymph nodes and Pott sign12. If a person exhibited any of these symptoms, further investigations will be done before TPT initiation. TPT is prescribed and monitored by healthcare providers at referral hospitals and at health centers.

Despite efforts by the national TB program, TPT coverage among key target population, such as newly diagnosed HIV positive and household contacts of bacteriologically confirmed pulmonary TB were only 53% and 34% respectively10. In addition to this low TPT initiation, no study has been conducted to understand the magnitude of TPT non-completion and its associated factors. A recent published qualitative research focused only on the challenges in TPT implementation among children15. Given this limited scientific evidence, it is necessary to explore the magnitude and factors associated with TPT non-completion in the country. The aim of this study is to identify factors associated with TPT non-completion in Cambodia using 6-years programmatic data (2018–2023).

Methods

Study design

It was a retrospective analysis of six-years programmatic data between 2018 and 2023, retrieved from TB management information system (TB-MIS). It is a web-based platform developed by the National Center for Tuberculosis and Leprosy Control that captures data across key aspects of TB control, including TPT from public health facilities in the whole country.

Population

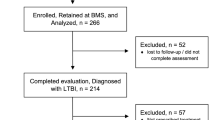

This study included all TPT eligible individuals, irrespective of age. All participants were initiated with a treatment regimen containing any type of TPT. The analysis encompassed data on both individuals who successfully completed the prescribed TPT regimen and those classified as TPT non-completion due to loss to follow-up or discontinuation of the treatment. Those who had not started TPT, died during TPT course, were diagnosed with TB during the TPT course, or were undergoing TPT, were excluded from the study. (Fig. 1).

Data management and statistical analysis

We retrieved programmatic data between 2018 and 2023 from TB-MIS. Sociodemographic data were included such as age, sex, nationality, TPT regimens, and TPT initiation health facilities. Dependent variable is TPT completion status. Those who complete and incomplete TPT regimens were coded as 0 and 1 respectively. Explanatory variables were age in years (< 5, 5–14, 15–24, 25–34, 35–44, 45–54, 55–64, and ≥ 65), sex (male, female), nationality (Cambodian and others), TPT regimens (3HP, 3RH, 6H), and TPT initiation places (health centers or referral hospitals). Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test was computed to describe characteristics of study participants. Bivariate analysis was conducted to assess initial associations between TPT non-completion and explanatory variables. Any p-value < 0.10 identified in bivariate model were included in the multivariate logistic regression analysis. Based on literature reviews, age and sex were automatically included in the regression model, regardless of their significance level. We calculated Odds Ratios (OR) to measure the magnitude of the association between TPT non-completion and explanatory variables. Any explanatory variables with p-value < 0.05 in multivariate model were considered as factors significantly associated with TPT non-completion.

Ethics

This study looked back at existing data from TB-MIS to identify factors associated with TPT non-completion. No patients were directly involved in the study. Instead, researchers at the national tuberculosis program analyzed anonymized data extracted from TB-MIS as part of their routine surveillance and data analysis activities. This research followed the ethical guidelines of the Helsinki Declaration. Since the data was already anonymized, informed consent from individual patients and ethical clearance were not required from the National Ethics Committee for Health Research (NECHR).

Results

In total, 14,262 individuals were included in the analysis, of whom 299 (2.1%) did not complete TPT. As shown in Table 1, 40% of participants was those aged less than 15 years old, and more than half (56.7%) were female. Almost all study population was Cambodian. Among the three TPT regimens, almost half of LTBI cases (47.4%) were initiated with 3RH, followed by 6H (33.5%). The majority of TPT initiation was made at health centers (95.4%).

Factors potentially associated with TPT non-completion were shown in Table 2. In bivariate logistic regression, those aged 25–34 years old, initiated with 3RH and 6H, and initiated TPT at referral hospitals were the factors potentially associated with TPT non-completion.

Multivariate logistic regression is shown in Table 3 to identify factors independently associated with TPT non-completion. The following potential confounders were included in the model: age, sex, treatment regimens, and place of TPT initiation. After adjusting with other potential confounders, the likelihood of TPT non-completion among aged 15–24 and 25–34 years old were higher compared to the reference group (aged < 5 years old), with an adjusted odds ratios (aOR) 1.70 (95% CI 1.04–2.78), p = 0.034 and 2.09 (95% CI 1.29—3.40), p = 0.003, respectively.

TPT regimens were also found to be factors associated with TPT non-completion. Compared to 3HP, the likelihood of TPT non-completions were higher among those initiated with 3RH and 6H, with aOR 2.61 (95% CI 1.53—4.46), p < 0.001 and 7.01 (95% CI 4.19—11.72), p < 0.001, respectively.

Places of TPT initiation also affected TPT completion. LTBI individuals who initiated the treatment at referral hospitals were almost twice more likely to not complete the treatment compared to those initiated TPT at health centers, with aOR 1.95, 95% CI 1.25–3.03, p = 0.003.

Discussion

Based on our best knowledge, this is the first study to explore factors associated with TPT non-completion in Cambodia using programmatic data from the national TB program. The present study found that TPT non-completion was only 2.1%. This proportion is lower than TPT non-completion rates in other studies5,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23.

After adjustment for other confounding variables, individuals aged of 15–34 years were found to be factor associated with TPT non-completion. This finding is consistent with a study in Portugal6. A Systematic review and meta-analysis of TPT adverse events found that incidence of all types of adverse events leading to TPT discontinuation was higher in adults than in children, with proportion of 3.7% and 0.4% respectively. The same review also found that TPT non-completion due to TPT hepatotoxicity was 1.1% in adults, compared to only 0.02% in children24. This failure to complete treatment could also be due to competing obligations from school and family life. Conversely, the stronger focus on TPT completion in younger age groups, particularly those under 5, might be due to increased support from families and healthcare providers. This could be because families are more involved in their children’s treatment, and healthcare professionals might perceive TPT as more critical for younger people with LTBI. This focus may stem from Cambodia’s initial implementation of TPT only for children under 525.

While other studies found women had higher risk of TPT non-completion and vice-versa26,27, our study did not find any sex difference on TPT non-completion. The national TB program should continue this good practice to ensure gender balance in TPT implementation.

Regarding treatment regimens, TPT initiation with 3RH and 6H was found to be associated with increase treatment non-completion, compared to 3HP. This finding is in line with other studies6,28. A study in the United State also found that initiation with longer TPT regimen (9 months of Isoniazid) had lower treatment completion rate than shorter regimens (3HP or four months of Rifampin)29. In Cambodia, three TPT regimens were adopted. 3RH and 6H are the daily treatment regimens for durations of 3 and 6 months respectively whereas 3HP is a 3-month weekly treatment regimen. Compared to 3RH and 6H, 3HP has a lowest pill burden which could be a factor influencing a completed TPT course. This study did not capture adverse events of the three TPT regimens which could potentially affect treatment non-completion. Several studies in other countries have been conducted to investigate adverse events of different TPT regimens. A meta-analysis by Winters N et al. and a systematic review and meta-analysis by Luca Melnychuk et al. found that TPT discontinuation due to treatment-related adverse events was higher among those initiated with 3HP than with 4 months of daily Rifampicin (4R)24,28.

Our research identified a significant association between health facility levels where TPT was initiated and treatment completion rates. People who began TPT at referral hospitals were nearly twice as likely to not complete the treatment compared to those who started at health centers. This finding aligns with observations from other studies exploring healthcare access and completion to treatment regimens. For example, a Ugandan study investigating TPT completion among HIV-positive individuals noted similar trends30. Those initiating treatment at urban facilities demonstrated lower completion rates compared to those starting in rural health centers30. This could be attributed to several factors, including proximity to healthcare facilities as health centers typically represent the most accessible level within the Cambodian healthcare system. This geographical convenience allows for easier follow-up appointments, medication refills, and potentially reduces transportation burdens, all of which contribute to improved adherence31. Furthermore, referral hospitals, while equipped to manage intricate medical cases, might lack of dedicated personnel or targeted programs specifically tailored for TPT management compared to health centers where often deliver more focused healthcare programs, including TPT management. Additionally, social support networks might be stronger in local communities surrounding health centers, fostering better treatment adherence31. Therefore, the national TB program should decentralize TPT initiation, which is in line with WHO recommendations to decentralize TB preventive service32.

While secondary data analysis is convenient and cost-effective, it has some drawbacks. The data may not perfectly address this specific research question. It was collected as part of routine TB program. So, a comprehensive analysis of factors associated with TPT non-completion may be missing. Even though, potential factors such as age, sex, TPT regimens were included in the analysis. Data quality is also a concern as we have limited control over the data’s quality during recording and entering into the system. Despite this, different data quality control mechanisms were applied. Healthcare providers who were responsible for completing data collection forms were trained on LTBI, TPT, data completion, and data entry into TB-MIS. Importantly, TB-MIS was designed to control quality of entered data through several key features. These features include the provision of clear instructions, a logical data entry flow, and drop-down menus to avoid typing errors. In addition, data validation rules were set up in the system to restrict invalid or outliers such as age, weight and so on by limiting the entries to a specific range within a certain minimum and maximum values. Logic to skip was also designed to skip irrelevant questions based on previous answers. To ensure data completeness, the system was built with programs to alert before exiting each question to ensure that each data element was completed. Importantly, a multi-tiered supervisory framework was implemented. Supervisors at national, provincial, and district levels provided routine support to health facilities where data were recorded and entered into the system. This support included verifying the use of appropriate data collection forms, ensuring data completeness, and identifying and correcting errors before data entry. Finally, retrieved data was cleaned and managed before analysis.

This study offers several key strengths, including the use of nationally representative data, although TPT has not been implemented consistently across health facilities within the country. It allows us to draw conclusions about factors associated with TPT non-completion that can be applied to the whole country. This is particularly valuable for informing national public health policies and interventions. Even while generalizability to the whole nation, nationally representative data allows us to examine TPT non-completion within subgroups such as age, treatment regimens, and place of TPT initiation. Overall, using nationally representative data provides a strong foundation for developing effective public health strategies to improve TPT completion rates and tuberculosis control efforts.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study is the first to utilize nationally representative data to identify factors associated with discontinuation of TPT. Individuals aged 15–34 years, those treated with 3RH and 6H regimens, and those who initiated treatment at referral hospitals were more likely to not complete TPT. To improve TPT completion rates, priorities should include strengthening treatment follow-up for young adults aged 15–34 years and tailoring treatment to individual needs. Additionally, the national TB program should consider making the 3HP regimen the first-line treatment option. Furthermore, strengthening treatment follow-up at referral hospitals and exploring the decentralization of TPT initiation to health centers or even the community level should be considered.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Getahun, H., Matteelli, A., Chaisson, R. E. & Raviglione, M. Latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 372(22), 2127–2135 (2015).

Dodd, P. J., Gardiner, E., Coghlan, R. & Seddon, J. A. Burden of childhood tuberculosis in 22 high-burden countries: A mathematical modelling study. Lancet Glob. Health 2(8), e453–e459 (2014).

World Health Organization. Implementing the end TB strategy: the essentials. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015. Report No.: 9241509937.

World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2023 (World Health Organization, 2023).

De Aguiar, R. et al. Factors associated with non-completion of latent tuberculosis infection treatment in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: A non-matched case control study. Pulmonology. 28(5), 350–357 (2022).

Sentís, A. et al. Failure to complete treatment for latent tuberculosis infection in Portugal, 2013–2017: Geographic-, sociodemographic-, and medical-associated factors. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 39(4), 647–656 (2020).

Chang, S.-H., Eitzman, S. R., Nahid, P. & Finelli, M. L. U. Factors associated with failure to complete isoniazid therapy for latent tuberculosis infection in children and adolescents. J. infect. Public Health 7(2), 145–152 (2014).

Nguyen Truax, F. et al. Non-completion of latent tuberculosis infection treatment among Vietnamese immigrants in Southern California: A retrospective study. Public Health Nurs. 37(6), 846–853 (2020).

Sugishita, Y., Goto, C., Sakamoto, T., Sugawara, T. & Ohkusa, Y. Risk factors affecting the failure to complete treatment for patients with latent tuberculosis infection in Tokyo Japan. J. Infect. Chemother. 26(11), 1129–1133 (2020).

World Health Organization. Tuberculosis profile: Cambodia: World Health Organization; 2022 [Available from: https://worldhealthorg.shinyapps.io/tb_profiles/?_inputs_&entity_type=%22country%22&lan=%22EN%22&iso2=%22KH%22

Houben, R. M. & Dodd, P. J. The global burden of latent tuberculosis infection: A re-estimation using mathematical modelling. PLoS Med. 13(10), e1002152 (2016).

The National Center for Tuberculosis and Leprosy Control. Programmatic Management of Latent TB Infection (LTBI): Standard Operating Procedures for LTBI Management and TB Preventative Therapy (TPT). Phnom Penh, Cambodia; (2020).

National Center for Tuberculosis and Leprosy Control (CENAT). Programatic management of latent TB infection (LTBI): Standard operation procedure for LTBI management and TB preventive therapy (TPT). Phnom Penh, Cambodia; (2020).

World Health Organization. WHO operational handbook on tuberculosis: module 1: prevention: tuberculosis preventive treatment. Genera: World Health Organization; 2020. Report No.: 9240002901.

An, Y. et al. They do not have symptoms–why do they need to take medicines? Challenges in tuberculosis preventive treatment among children in Cambodia: A qualitative study. BMC Pulm. Med. 23(1), 1–8 (2023).

Moro, R. N. et al. Factors associated with noncompletion of latent tuberculosis infection treatment: Experience from the PREVENT TB trial in the united states and Canada. Clin. Infect. Dis.. 62(11), 1390–1400 (2016).

Eastment, M. C., McClintock, A. H., McKinney, C. M., Narita, M. & Molnar, A. Factors that influence treatment completion for latent tuberculosis infection. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 30(4), 520–527 (2017).

Malejczyk, K. et al. Factors associated with noncompletion of latent tuberculosis infection treatment in an inner-city population in Edmonton, Alberta. Can. J. Infect. Dis. Med. Microbiol. 25, 281–284 (2014).

Silva, A. et al. Non-completion of latent tuberculous infection treatment among children in Rio de Janeiro State, Brazil. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 20(4), 479–486 (2016).

Trajman, A. et al. Factors associated with treatment adherence in a randomised trial of latent tuberculosis infection treatment. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 14(5), 551–559 (2010).

Cola, J. et al. 2023 Factors associated with non-completion of TB preventive treatment in Brazil. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 27(3), 215–220 (2023).

Hirsch-Moverman, Y., Daftary, A., Franks, J. & Colson, P. Adherence to treatment for latent tuberculosis infection: Systematic review of studies in the US and Canada. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 12(11), 1235–1254 (2008).

Shenoi, S. V. et al. Community-based referral for tuberculosis preventive therapy is effective for treatment completion. PLOS Glob. Public Health 2(12), e0001269 (2022).

Melnychuk, L., Perlman-Arrow, S., Lisboa Bastos, M. & Menzies, D. A systematic review and meta-analysis of tuberculous preventative therapy adverse events. Clin. Infect. Dis.. 77(2), 287–294 (2023).

National Center for Tuberculosis and Leprosy Control (CENAT). Tuberculosis Report 2022. Phnom Penh, Cambodia; 2022.

Priest, D. H., Vossel, L. F. Jr., Sherfy, E. A., Hoy, D. P. & Haley, C. A. Use of intermittent rifampin and pyrazinamide therapy for latent tuberculosis infection in a targeted tuberculin testing program. Clin. Infect. Dis. 39(12), 1764–1771 (2004).

LoBue, P. A. & Moser, K. S. Use of isoniazid for latent tuberculosis infection in a public health clinic. Am. J. Respire. Crit. Care Med. 168(4), 443–447 (2003).

Winters, N. et al. Completion, safety, and efficacy of tuberculosis preventive treatment regimens containing rifampicin or rifapentine: An individual patient data network meta-analysis. Lancet Respir. Med. 11(9), 782–790 (2023).

McClintock, A. H. et al. Treatment completion for latent tuberculosis infection: A retrospective cohort study comparing 9 months of isoniazid, 4 months of rifampin and 3 months of isoniazid and rifapentine. BMC Infect Dis. 17, 1–8 (2017).

Musaazi, J. et al. Increased uptake of tuberculosis preventive therapy (TPT) among people living with HIV following the 100-days accelerated campaign: A retrospective review of routinely collected data at six urban public health facilities in Uganda. PloS One 18(2), e0268935 (2023).

Sandoval, M. et al. Community-based tuberculosis contact management: Caregiver experience and factors promoting adherence to preventive therapy. PLOS Glob. Public Health 3(7), e0001920 (2023).

Organization WH. WHO consolidated guidelines on tuberculosis: module 5: management of tuberculosis in children and adolescents: web annex 3: GRADE evidence to decision tables. 2022.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y. A. performed data acquisition and was responsible for study conception, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript content and writing. K.E.K was responsible for study conception, data interpretation, manuscript content and writing. All authors reviewed and have approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

An, Y., Khun, K.E. Factors associated with incomplete tuberculosis preventive treatment: a retrospective analysis of six-years programmatic data in Cambodia. Sci Rep 14, 18458 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67845-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67845-6

- Springer Nature Limited