Abstract

Many developmental psychologists aspire to conduct research that informs interventions and policies to prevent income-related disparities in child development. Among growing researcher discussion about the value of interventions that target “structural” and resource-related correlates of income inequality and child development (e.g., housing, food, material goods, cash), rather than individual, person-centered correlates (e.g., parenting behaviors), the perspectives of mothers with low incomes may provide important context. 281 mothers with young children and low incomes rated various structural and individual interventions, framed as having minimal costs and entry barriers, for their perceived helpfulness. Analyses were pre-registered. Overall, mothers rated all interventions very highly, though they rated structural interventions as slightly more helpful than individual interventions. Mothers rated interventions they used in the past as less helpful than those they hadn’t previously used. An exploratory qualitative analysis revealed mothers’ desires for supports in other intervention domains beyond those addressed in our survey. Together, mothers’ responses indicated that they did not see individual interventions as inherently unhelpful due to a focus on individual states, knowledge, and skills. Implications for developmental psychology and intervention science are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Introduction

Much developmental psychology research is focused on identifying mechanisms that drive socioeconomic disparities in child development, with the goal of informing intervention science. Parenting has been identified as one particularly important mechanism linking socioeconomic status to child outcomes1. This research has given rise to many interventions targeting mothers of young children with low incomes, often aimed at improving knowledge of child development and engagement in developmentally-supportive parenting behaviors2.

However, recent critiques have argued that this kind of research and the resulting intervention work promote a deficit orientation in which mothers with low incomes are portrayed as inherently lacking the knowledge and skills to support their children’s development3. These arguments highlight that poverty-related disparities in child development are in part driven by larger systemic issues of class- and race-based inequality and suggest that more focus should be directed toward studying and targeting these structural issues to improve outcomes for children facing socioeconomic disadvantage4.

It is unknown how mothers view the helpfulness of individually and structurally directed interventions and whether mothers perceive individual interventions negatively, a possibility given the concerns raised in recent critiques. Thus, this study aimed to provide insight on these issues by gathering the perspectives of mothers with low incomes who are raising young children. Specifically, we collected information on how helpful mothers viewed various individual and structural interventions. Mothers’ perspectives may provide useful context to researchers as they reflect on these complex issues in the context of their own programs of research.

Developmental research and individual-directed interventions

Family income shows robust associations with child outcomes across development5. Disparities are present in early childhood6,7,8,9 and generally widen across the first years of life8,10,11. Many have argued that investments to prevent long-term socioeconomic disparities are most fruitful when made in early childhood12,13. This argument is in part motivated by evidence that the brain is particularly plastic during early childhood14,15. Researchers also expect that improving early skills will result in developmental cascades and dynamic complementarities that produce long-run positive outcomes12,16. While it is important that the field continues to use long-run experimental evaluations to assess the extent to which these expectations are empirically supported17,18,19,20, these expectations have nonetheless given rise to a focus on early childhood as a crucial window for interventions aimed at preventing socioeconomic disparities across the life course.

Towards these ends, developmental psychology has generated theory about the environmental mechanisms through which socioeconomic status might impact development and, subsequently, what experiences interventions should target. Parenting behaviors have been highly studied as an important mechanism linking socioeconomic factors to child development1,21. The Family Stress Theory, for example, asserts that low incomes impose stress on parents and the larger family system, leading to less engagement in developmentally supportive parenting behaviors, with implications for child development22. Indeed, lower socioeconomic status has been associated with increased maternal stress23,24, less maternal engagement in child-directed speech25, and less maternal responsiveness and sensitivity1,21. These parenting behaviors have been associated with lower performance on measures of children’s early cognitive and social-emotional development26,27. Much of this research shares the goal of informing intervention science1.

Indeed, this research has informed the creation of interventions targeting the states, knowledge, and skills of parents with low incomes. Many home visiting programs provide parents with information about child development and developmentally supportive caregiving behaviors2,28,29,30,31,32. Some programs focus on promoting specific parenting behaviors, such as engagement in high-quality child-directed speech33 and shared book reading34. Other interventions explicitly target parental states, such as maternal stress, through therapeutic or mindfulness-based activities35,36,37. Adjacent interventions target money management skills38,39,40, in some cases explicitly to reduce stress through improving cognitive bandwidth.

Deficit orientation and structural factors

Several developmental research groups have raised concern that parent-focused interventions inadvertently promote a deficit message that caregivers with low incomes lack knowledge of child development or parenting skills, thereby insinuating parents are “to blame” for socioeconomic disparities in child outcomes. These arguments have suggested that focusing solely on parents as a lever for reducing socioeconomic disparities in child outcomes overlooks: (1) the many strengths in parenting behaviors that are not captured by traditional measures and measurement contexts, and (2) the role of racist and classist structures, closely tied to socioeconomic status, that contribute to differences in parenting behaviors and child outcomes. In effect, individual-directed interventions can be stigmatizing and undervalue parents’ wealth of knowledge at the expense of research-informed ideals. These concerns have been particularly prominent in the past 5 years3,4,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49. While these dynamics are clearly front-of-mind today, researchers have long been grappling with these issues1.

The first concern is that research on socioeconomic differences, and individual-directed interventions to address these, can easily cast differences in behaviors in terms of deficits, with little consideration of adaptation and strengths. Strengths-based theory suggests that individuals with low incomes may engage in different caregiving behaviors than individuals with socioeconomic advantage, but these differences likely reflect adaptations to context42,50. Such adaptations may confer benefits to children’s development, in the form of “hidden talents,” which have been overlooked in past research51. These arguments often make explicit the connection between socioeconomic status and race, highlighting that families with low incomes are disproportionately Black, Latino, and Indigenous5, driven by historical and present-day discrimination and structural racism. As such, differences in parenting behaviors by socioeconomic status and race may reflect differences in values or practices that are, in fact, positive and meaningful in shaping development41. For example, researchers often describe 'harsher' parenting behaviors as less supportive for child development. However, in the context of racism and classism, these behaviors might equip children for a world in which there are potentially high costs for acting out52. In response to harsher parenting, children may develop protective cognitive and social adaptations that allow them to be more attuned to negative emotionality and threat51. Here, harsher parenting behaviors may serve an important developmental purpose.

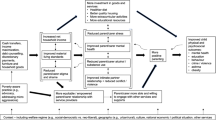

The second major concern is that individual-directed interventions do not adequately address the contextual factors that shape socioeconomic disparities in parenting behaviors and child development. In developmental psychology, dominant theory maintains that multifaceted contextual factors53 and racially and socioeconomically discriminatory structures and systems54,55 shape development and behavior. Such structures and systems can be thought of as “structural factors,” defined as stable, external pressures associated with an individual’s social position43,56. Structural factors may include access to employment and quality education opportunities, food, housing, child-specific material goods, medical care, transportation, as well as physical and environmental safety. Formalized conceptual models have theorized various causal pathways by which structural factors may shape parent and child behaviors and states43,55.

Some scholars have argued that the field should place greater attention on interventions targeting structural factors4,42,43. While individually directed interventions aim to prevent socioeconomic disparities in child development, they do nothing to change contexts of inequality and structural factors that are likely to shape parent and child development when interventions end. Given an inherent focus on context and resources, structural interventions may be less likely to promote a deficit orientation than individual interventions. Similar considerations around the need for more individual versus structural interventions are a recent topic of debate in other disciplines57 and parallel a rich history of research in the field of sociology, where structures are widely implicated in understanding individuals’ behaviors58.

Importantly, while structural-versus-individual perspectives can be interpreted as conflicting, they need not be. Theories on parenting as a mechanism driving socioeconomic disparities in child outcomes often highlight the ways in which structural factors shape parenting and child development1,59,60. Likewise, some critics of the field’s deficit orientation have argued that individual-directed interventions can still be valuable when employed with an explicit strengths-based approach42,43, and that existing structural, resource-based interventions are not all strengths oriented, especially in implementation42. And, certainly, there are new parent-directed interventions that have been developed with the specific intention of employing a strengths-based approach61. Nonetheless, these perspectives raise questions about the role that individual versus structural research and interventions should play in ongoing efforts to prevent socioeconomic disparities in development. As researchers reflect on these issues in the context of their own research, the perspective of mothers with low incomes and young children may provide helpful context.

Mothers’ perspectives

Intentionally incorporating the knowledge and expertise of members of the communities studied in research is a crucial step to progressing psychological research in this area and others42,46,62. Mothers’ perspectives may provide valuable information about the extent to which mothers view individual and structural interventions as potentially helpful. Indeed, it is unknown whether mothers view individually directed interventions negatively and as unhelpful, which is a concern given the issues surrounding deficit orientation.

While, to our knowledge, there is no study that has explicitly asked mothers about their perceptions of individual versus structural interventions in the context of raising young children, there is a vast literature on the perspectives of mothers with low incomes on the experience of interacting with government programs. Two recent studies are particularly relevant. One study involved a metasynthesis of how mothers who participated in various parenting programs viewed their experience63. The authors found that mothers endorsed parenting interventions as useful, but also noted the structural factors that make parenting difficult, and the challenge of keeping up what they had learned in the intervention after it ended. Mothers’ perspectives on the program’s value changed over the course of the intervention itself, suggesting that parents’ experiences of interventions may shape their perceptions of them. In a second study, mothers with young infants living in poverty in New York City were interviewed about their experience accessing public services (targeting structural factors) as new mothers64. The authors found that mothers had a variety of needs related to structural factors such as housing, cash, food, and child care, that existing government programs did not go far enough in addressing. The study suggests that mothers would benefit from more, and better, structural supports.

Current study

The present study gathered the perspectives of mothers with young children and low incomes to answer a series of pre-registered questions about how mothers perceived the helpfulness of individual and structural interventions, specifically for supporting early childhood development. We investigated the following questions with an eye towards identifying descriptive trends and variation in responses: (1) How helpful do mothers anticipate that a wide range of interventions would be for families in circumstances similar to their own? (2) Are there differences in how helpful mothers anticipate that individual and structural interventions will be? (3) Do mothers’ endorsements of intervention helpfulness reflect that the structural versus individual distinction shapes their perspectives? (4) Do mothers’ ratings of anticipated intervention helpfulness differ by whether they have accessed the intervention of interest in the past? (5) What interventions do mothers endorse as most helpful? Additionally, we posed two questions that were not pre-registered: 1) Do family income, maternal perceived stress, and reported material deprivation predict variation in responses? 2) What themes emerge in mothers’ open-ended responses about the most pressing needs they see facing moms with young children? Given the exploratory and descriptive nature of this study, we did not pre-register specific hypotheses. Rather, pre-registration was used to solidify our research questions and analyses prior to examination of the data.

Methods

Study design

Participant recruitment took place through two recruitment streams, both of which were approved by the Institutional Review Board at Teachers College, Columbia University. Research was conducted in accordance with ethical guidelines and regulations. 251 participants were recruited in 2023 through a combination of internal participant databases, community partnerships, and word of mouth (i.e., modality #1). The study was advertised as a study to understand mothers’ thoughts on the helpfulness of various resources and programs. Of note, while the recruitment materials focused on mothers, we did not explicitly ask participants to indicate whether they were the biologically related mother, adoptive mother, step-parent, or another kind of primary caregiver. Individuals were eligible for participation if they reported a household income less than 200% of the Federal Poverty Line (FPL) for their respective family size and that they had a child under the age of five. Informed consent was obtained for all participants. Following consent, participants completed the online study surveys remotely and were compensated for participation. Surveys were provided in English and Spanish.

43 participants were mothers participating in an ongoing longitudinal study of child development (i.e., modality #2). Mothers were recruited for the longitudinal study between 2019 and 2022, during their third trimester of pregnancy. To be included, mothers had to be 18 years of age or older, carrying a singleton with no known neurological or developmental concerns, be at least 25 weeks pregnant, and speak English or Spanish. Mothers participating in the longitudinal study who had incomes less than 200% of the FPL for their family size were prompted to complete the surveys for this study as one component of the larger battery at their next study visit (i.e., 12-, 18-, or 36- months), with a combination of in-person and online remote survey completion. Data collection for the surveys for this study took place in 2022 and 2023. All participants were compensated.

Participants

In total, data were collected from 294 participants. As per the project pre-registration, one participant was excluded due to living outside of the United States and 12 participants were excluded due to ultimately reporting incomes above 220% of the FPL after consenting for participation (see supplement for additional details). To maximize data, participants with incomes between 200 and 220% of the FPL were included in the primary models given no substantive differences in results from models that dropped these individuals (see analytic plan). Of note, one participant ultimately reported that their child was 5.25 years old, which was above the original inclusion criteria of five years old or younger. This participant was included in the primary models and similarly dropped in the robustness checks (see analytic plan), with no differences in the results with their exclusion.

Thus, 281 participants comprised the primary analytic sample (n = 240 from modality #1, n = 41 from modality #2). Table 1 details participant demographics. On average, mothers were around 32 years old (SD = 6.79) and had completed 12–13 years of formal education (SD = 4.48). The average family income was 67% of the FPL (i.e., for a family of 2 adults and 2 children the FPL was $29,678 in 2022). On average, mothers had 2 children (SD = 1.20; range = 1 to 8) with the youngest child 26.2 months old (SD = 17.04 months), though this ranged from a few weeks old to 5.25 years old. 67% of mothers were Hispanic or Latino, 26% of mothers were Black, 18% were White, and 23% indicated “Other Race.” On average, mothers reported perceived stress levels in the ‘moderate’ range (M = 17.35, SD = 7.17; Nedea, 2020). Mothers endorsed nearly 4 indicators of material deprivation on average (SD = 2.79; sample range = 0–13, maximum possible = 14), though the modal response was the endorsement of one indicator. The majority of participants resided in New York City.

Measures

Maternal perceptions of intervention helpfulness

We asked mothers a series of questions to understand how helpful they thought various interventions would be for supporting early child development (see supplement for full list of items). We asked about a range of indivdual- or person-directed and resource- or structurally-directed interventions, hereafter referred to as “Intervention Categories.” Each category captured an important intervention type often discussed as a potential target for efforts to prevent income-related disparities in child development. In determining individual-directed interventions, we focused on interventions described in the literature targeting parent states, knowledge, and skills (see introduction for review). Individual-directed interventions included those that: educate about child development, teach parenting skills, help with money management, and reduce stress/increase wellbeing. In determining structural-directed interventions, we attempted to identify domains that fit the conceptual definition of “structural factors” based on factors that have been explicitly conceptualized as structural in past work 43. Structural-directed interventions included programs that: reduce housing costs, increase access to medical care, increase access to healthy foods, help with understanding and applying for social services, provide child-related items, provide high-quality childcare, and provide unconditional cash to be spent as mothers wish.

Series of Intervention-Related Questions. For each of the 11 Intervention Categories, mothers answered a series of questions. We instructed mothers to report how helpful they thought each intervention would be for helping mothers in similar circumstances to their own in raising their young child ages zero to five years old65. To focus on mothers’ perceptions of intervention helpfulness based on intervention content and to reduce mothers’ consideration of logistical barriers, we framed the interventions as free, close-to-home, and flexible in terms of timing. We randomly selected the order in which the Intervention Categories were presented.

We first asked mothers how helpful they anticipated the Intervention Category would be, and we provided examples of intervention modalities (e.g., How helpful would resources to reduce housing costs be (such as access to a public housing unit or access to housing vouchers)?). Mothers rated helpfulness on a scale of 0 to 4 (0 = Not at All Helpful, 1 = Slightly Helpful, 2 = Somewhat Helpful, 3 = Very Helpful, 4 = Extremely Helpful). In addition to analyzing the ratings for each of the 11 Intervention Categories, we created three scores to capture perceived helpfulness: (1) a Total Helpfulness score, which reflected the sum of helpfulness ratings across the 11 Intervention Categories (range = 0 to 44; α = 0.91), (2) a Structural Intervention Helpfulness score (range = 0 to 4; α = 0.86), and (3) an Individual Intervention Helpfulness score (range = 0 to 4; α = 0.82). These last two scores reflected the average helpfulness ratings for each Intervention Category within the structural and individual domains, respectively (4 categories for structural, 7 categories for individual as detailed above). One mother had missing responses on the 11 Intervention Category helpfulness ratings and was not assigned these scores.

Next, if mothers rated an Intervention Category as at least “Slightly Helpful” (numerical value of 1), we then asked them to rank the helpfulness of specific intervention modalities using the same 0 to 4 scale. For example: How helpful would each of the following programs to reduce housing costs be?: (1) Access to a public housing unit (living in a government-provided public housing unit and paying 30% of your income towards rent); (2) Access to housing vouchers to reduce rent costs (paying 30% of your income towards rent in an approved unit (possibly your own, or at least one that you choose) and the government pays the rest). We asked mothers to rank the helpfulness of 28 modalities across 10 of the 11 Intervention Categories (i.e., 2 to 3 modalities per category; we did not ask about medical-care related modalities). For the purposes of analysis, we set ratings to “Not at All Helpful” (numerical value of 0) for mothers who rated the entire Intervention Category as “Not at All Helpful.”

In the final question in the series we asked mothers whether they had ever used a program or service in each Intervention Category (e.g., Have you ever used a program/service that reduces housing costs?). In addition to analyzing intervention-level responses to this item, we also created a Total Past Use score by summing the number of Intervention Categories for which mothers reported having used an intervention in the past (range = 0–11). Two mothers had missing responses and were not assigned a score.

Stand-Alone Questions. We posed one question about what intervention domains (i.e., structural and/or individual) mothers thought would be helpful in supporting early development. Mothers could select: (1) both individual and structural interventions as helpful, (2) only individual interventions as helpful, (3) only structural interventions as helpful, or 4) neither intervention types as helpful. All of the appropriate Intervention Categories were provided as examples of “individual” and “structural” interventions. All participants who selected “neither” in addition to individual and/or structural interventions were prompted to answer the question again. If they again selected an invalid response, their response was set to missing. Five mothers' responses were missing as a result, in addition to one mother who did not complete the question.

We posed three final questions that prompted mothers to select the most helpful Intervention Category from a list of options. The first question asked mothers to select whether cash to be spent on anything or resources to address a specific cost would be most helpful (e.g., resources for housing, medical, food, child-related expenses, childcare). The second question asked mothers to select the most helpful Intervention Category among all of those that provided resources to address a specific cost. The third question asked mothers to select the most helpful Intervention Category among all of the individual intervention options. In each question, “none” was provided as an option. One mother did not complete these questions.

Prior to asking all of the questions detailed above, we posed one open-ended question: “What do you see as the most pressing need for moms like you in supporting their children's early development? Think about moms with children ages zero to five who have similar circumstances and life experiences as you.” Responses were categorized for the purposes of an exploratory analysis (see supplement for more details). 108 mothers had un-usable responses (nmisinterpreted = 73, nvague = 25, ninvalid = 10, nmissing = 2), leaving responses from 173 mothers for analysis.

Demographic and contextual variables

We collected information on several demographic and contextual variables including: maternal race and ethnicity, maternal age, child age (for youngest child, if multiple), child sex, maternal educational attainment, income-to-needs (ITN) ratios, material deprivation, and perceived stress. ITN ratios were calculated by dividing household family income by the respective poverty threshold for the family’s size. At the time of analysis, the 2023 poverty thresholds were not yet released so the 2022 thresholds were used. To determine household income, mothers were asked to report total income for all adult family members in their household in addition to what bin their income fell within (presented in $10,000 increments). When there was a discrepancy between these two values, mothers were asked to select the most correct representation. If the bin was selected, incomes were set to the median of the bin. Material deprivation was assessed using the Material Deprivation Scale66 and perceived stress was assessed using the Perceived Stress Scale67. The supplement presents additional information on these measures. Table 1 displays the number of observations for each of these variables, with variable missingness due to missing data (nmatedu = 1, nitn = 9, npss = 3 , nmd = 2), implausible data (nmatage = 1), and invalid data (npss = 11, nmd = 29; i.e., participant answered some items but too many items were missing to calculate a score).

Analytic plan

The project’s pre-registration, data, and analytic code can be found at: https://osf.io/udwap. We ran all analyses using Stata 17.0 except from the Confirmatory Factor Analysis, which we ran in Mplus 8.2. First, to understand how helpful mothers anticipated that a wide range of interventions would be for families in circumstances similar to their own, we reviewed descriptive characteristics of the helpfulness ratings for the 11 Intervention Categories, the Total Helpfulness score, and 28 intervention modality ratings. To investigate whether helpfulness perceptions varied by whether mothers had used an intervention in the past, we conducted a pooled regression analysis with econometric fixed effects for each mother. Here, to determine within-mother differences in ratings by past use, helpfulness ratings for each Intervention Category (11 ratings in total) were regressed on an indicator for whether the mother indicated having accessed the program/service within that Intervention Category in the past with standard errors clustered at the mother level.

Next, to understand if there were differences in how helpful mothers anticipated that individual and structural interventions would be, we conducted a t-test to compare differences in endorsement of structural versus individual intervention helpfulness, as reported on the stand-alone question and based on the Individual Intervention Helpfulness and Structural Intervention Helpfulness scores. For the scores, we also performed a Levene’s test to check for differences in variance. We then performed a pooled regression analysis with econometric fixed effects for each mother in which all intervention helpfulness ratings (i.e., 11 ratings per respondent) were regressed on an indicator for whether the intervention was structural or individual and a control variable for each mother, with standard errors clustered at the mother level.

For both this analysis and the analysis focused on past intervention use, the econometric fixed effects approach helps in determining whether differences in ratings function at the within-mother level. Within-mother differences are differences in preferences controlling for whether each mother generally rated interventions as more or less helpful. Indeed, these models limit variation to the within-person level to ultimately determine differences in ratings for each mother from their own average. This is achieved through the control variable entered for each mother. The model aggregates individual within-mother differences to estimate average within-mother differences across all participants. In comparison, differences identified through t-tests could pick up on differences at the within- and/or between-mother level, the latter potentially reflecting a wide variety of endorsement patterns that generate average differences in ratings.

To further probe whether mothers’ helpfulness ratings reflected underlying structural and individual intervention latent factors, we performed a Confirmatory Factor Analysis using the 11 intervention helpfulness items. Finally, to understand which interventions mothers thought were most helpful, we reported on the responses to the three questions addressing which interventions were most helpful.

Robustness tests

Several participants were deemed ineligible to complete the survey due to inaccurate eligibility information (i.e., they reported an income > 200% of the FPL or a child over the age of five years old). As detailed in the pre-registration, all participants with incomes above 220% of the FPL (n = 12) and a youngest child six years or older (n = 0) were excluded. Results were examined both with and without (n = 272) participants with incomes between 200 and 220% of the FPL (n = 8) and children ages five to six (n = 1). Because results were the same across models, the data maximizing sample was used and reported as the primary model. In a non-pre-registered analysis, we also investigated descriptives for an alternate version of the Total Intervention Helpfulness Score which averaged contributing items instead of summing them. Finally, we additionally ran the econometric fixed effects models with both the indicator for intervention type (structural versus individual) and past intervention use to determine the robustness of the models with each variable entered independently.

Exploratory analyses

We conducted two non-pre-registered exploratory analyses. First, we examined the bivariate correlations between several key contextual factors (i.e., ITN, maternal education, perceived stress, and material deprivation) and intervention helpfulness scores (i.e., Total Intervention Helpfulness score, Structural and Individual Intervention Helpfulness scores, and each intervention helpfulness rating) to determine if there were any consistent associations among these variables which could be informative for future confirmatory research. Second, we used deductive and inductive techniques to categorize participants’ responses to the open-ended question about what they saw as the most pressing needs for mothers in supporting their children’s early development (see supplement for details).

Results

Perceptions of intervention helpfulness

We first set out to understand how helpful mothers anticipated a wide range of interventions, framed as free and accessible, would be for mothers in similar circumstances to their own (see Table 2 and Fig. 1). On average, total scores were skewed to the higher end of the of the distribution (M = 35.30, range = 0–44) with a modal response of the maximum score (44) and scores for the middle 50% of the distribution ranging from 32 to 42 (see supplemental Table S1 and Figure S1 for results using alternate scoring; conclusions were the same). This pattern was corroborated by average responses to each of the 11 Intervention Categories (see Fig. 2). Across all 11 categories mothers rated interventions as “Very Helpful” or “Extremely Helpful” on average (M = 2.96–3.44, SD = 0.88–1.19). For all Intervention Categories, the modal rating was “Extremely Helpful,” though responses ranged to “Not at All Helpful” for all categories. On average, the highest ratings were for interventions providing healthy foods (M = 3.44) and child-related goods (M = 3.43) and the lowest rating was for interventions supporting families to access social services (M = 2.96).

Overall Perceptions of Intervention Helpfulness across Intervention Categories. Note. This violin plot depicts ratings of perceived intervention helpfulness across 11 Intervention Categories, summed to create a Total Helpfulness score. The black coordinate indicates the average perceived helpfulness rating, the shaded region indicates the interquartile range, and the pink coordinates indicate each participant’s response. 44 was the maximum score. See additional information in Table 2. n = 280.

Perceptions of Intervention Helpfulness for each Intervention Category. Note. These violin plots depict ratings of perceived intervention helpfulness for each of the 11 Intervention Categories. The black coordinate indicates the average perceived helpfulness rating, the shaded region indicates the interquartile range. Helpfulness ratings ranged from 0 to 4: 0 = not helpful, 1 = slightly helpful, 2 = somewhat helpful, 3 = very helpful, 4 = extremely helpful). See additional information in Table 2. n = 280–281.

Figure 3 and Table 3 display ratings of perceived intervention helpfulness across different intervention modalities. The modal response was “Extremely Helpful” for almost all intervention modalities. Average ratings ranged from 2.58 for home-based childcare to 3.49 for children's books..

Perceptions of Intervention Helpfulness across Intervention Categories and Modalities. Note. These violin plots depict ratings of perceived intervention helpfulness for various intervention modalities within 10 of the 11 intervention categories (participants were not asked to report on helpfulness for different medical-related modalities). The black coordinate indicates the average perceived helpfulness rating, the shaded region indicates the interquartile range. Purple plots are “structural” interventions and yellow plots are “individual” interventions. Helpfulness ratings ranged from 0 to 4: 0 = not helpful, 1 = slightly helpful, 2 = somewhat helpful, 3 = very helpful, 4 = extremely helpful). See additional information in Table 2. n = 280–281.

Past intervention use

Most mothers reported having accessed a program or service in the past that was similar to the respective Intervention Category of focus, with past use endorsements ranging from 48 to 89% across categories (see Table 2). On average, mothers reported having accessed past interventions in about 8 of the 11 categories (SD = 2.73, range = 0–11). A pooled regression analysis with econometric fixed effects for each mother revealed that mothers reported lower anticipated intervention helpfulness for interventions that they had previously used (β= − 0.20, \(\beta\)= − 0.19, SE = 0.04, p < 0.001; see supplemental Table S2).

Individual vs. structural intervention helpfulness

We then ran analyses to understand if there were differences in how helpful mothers indicated interventions would be, based on our a priori distinction of “Individual” and “Structural” domains. We first considered mothers’ responses to a single survey question in which mothers indicated whether they expected that individual interventions, structural interventions, both, or neither would be helpful. 80% reported both, 12% reported structural interventions only, 7% reported individual interventions only, and 1% reported that neither would be helpful. Considered together, 92% of mothers endorsed structural interventions as helpful and 87% of mothers endorsed individual interventions as helpful, a marginally statistically significant difference (t(274) = 1.83, p = 0.07).

We proceeded to test whether there were differences in mothers’ average ratings of individual and structural intervention helpfulness using the Individual Intervention Helpfulness and Structural Intervention Helpfulness scores (see Table 2). Average Structural Intervention Helpfulness and Individual Intervention Helpfulness ratings were highly correlated at r = 0.78 (p < 0.001). Both scores reflected “Very Helpful” to “Extremely Helpful” ratings, though mothers rated structural interventions (M = 3.25) as statistically significantly more helpful than individual interventions (M = 3.14; t(279) = 3.34, p < 0.001). A Levene’s Test indicated that there was less variance in average ratings for structural interventions (SD = 0.79) than individual interventions (SD = 0.88), though this difference was only marginally significant (F(279, 279) = 0.80, p = 0.07). In a subsequent pooled regression analysis with econometric fixed effects for each mother, mothers rated structural interventions as 0.11 units more helpful than individual interventions, which translates to a 0.10 SD difference (SE = 0.03; p = 0.002) and suggests that differences in ratings functioned at the within-mother level (see supplemental Table S2). This difference held with the addition of a control for past intervention use (see supplemental Table S2).

As depicted in Fig. 4, when asked to choose the most helpful source of support considering direct cash versus other resource-based interventions to address specific costs (e.g., housing, food, childcare, etc.), 51% of mothers chose resources and 45% chose cash (4% chose neither). Among all other structural interventions, 43% of mothers chose childcare as most helpful, followed by housing (21%). Among individual-directed interventions, there was greater heterogeneity in responses: 33% chose interventions to increase knowledge of child development, 25% chose stress-reducing interventions, and 24% chose parenting-related interventions.

Interventions that Mothers Indicated as Most Helpful. Note. Mothers were asked to indicate which interventions they thought were most helpful in response to three questions: (1) Which would be most helpful: direct cash support versus other resources? (2) Which would be most helpful among all other resources? (3) Which would be most helpful among all of the individual interventions? For each question, mothers could endorse one response. n = 280.

Probing the “individual” versus “structural” distinction

We subsequently performed a Confirmatory Factor Analysis to determine whether ratings of intervention helpfulness loaded onto two distinct Individual and Structural factors. The model fit the data well (CFI = 0.98, RMSEA = 0.08), and the items loaded onto the two factors well (Individual Factor loadings = 0.74–0.87; Structural Factor loadings = 0.65–0.87; see supplemental Table S3). However, the Structural and Individual Factors were extremely highly correlated (r = 0.95) suggesting that there was high shared variance in ratings of individual and structural interventions.

Exploratory analyses

Associations between contextual factors and intervention helpfulness

In a non-pre-registered analysis, we tested the correlations between contextual factors and anticipated intervention helpfulness (Table S4 and Figure S2 in the supplement). Higher ITN, higher perceived stress, and higher material deprivation, but not educational attainment, were statistically significantly associated with higher total ratings of intervention helpfulness. Overall, these trends were relatively consistent across intervention domains, but varied in magnitude (r ~ 0.10 to 0.30). Interestingly, the correlation between higher ITN and higher intervention helpfulness ratings dropped to near zero and became statistically non-significant (p = 0.88) when participants with a reported ITN of zero (n = 74) were excluded (see supplement for more discussion).

Qualitative analysis on most pressing needs

In the second non-pre-registered analysis, we reviewed mothers’ responses to the open-ended question about the most pressing need facing mothers in supporting early child development (see supplement for more details). Among the 173 participants with valid responses, mothers endorsed interventions targeting parenting (n = 42), child care (n = 40), knowledge of child development (n = 30), maternal mental health and wellbeing (n = 18), cash (n = 12), healthy foods (n = 8), child-related goods (n = 8), medical care (n = 7), support in accessing services (n = 7), housing (n = 4), and money management (n = 1).

Additionally, three major themes emerged that were not captured in our 11 intervention domains. First, 24 mothers noted the need for a greater sense of community and social support, 10 of which specified the desire for support groups with other mothers. For example, two mothers said:

“Emotional support and a sense of community. Realizing that the stress you feel is normal and you aren't going through it alone.”

“More of a support system. Moms are expected to be these strong and independent pillars in the home but no one really checks in to ask how we are doing or feeling.”

Second, 22 mothers indicated the need for more organized activities, programs, and opportunities that provide opportunities for child development and socialization. Mothers said things like:

“Affordable sports activities for children.”

“Economic stability because it could have her in additional classes such as dance, ballet, among others, where she can interact much more, have experiences, have fun and learn from the environment.”

Third, 16 mothers indicated that what they needed most was more time to spend with their children:

“Time with our kids.”

“Most of us mothers do not have the time to care for our children during this stage of growth because we have to work to support our homes financially.”

Discussion

The current study surveyed 281 mothers with low incomes and young children to gather their perspectives on a range of interventions. When mothers imagined the possibility of individual and structural interventions that fit their schedules, were convenient to access, and were affordable or free, they pictured a variety of potentially helpful programs. Mothers’ open-ended responses highlighted that they saw a need for both individual and structural interventions:

“Many mothers lack education regarding early child development… I believe mothers do better when they know better.”

“I believe having free parenting courses or workshops to teach mothers how to deal with certain situations can be very helpful. Educating parents, for instance, on early signs of children with special needs. Also educating parents on ways to support their child's development at home.”

“To be assessed by a professional because it is not easy to be a full time mother and lose our social life.”

"The most pressing need is guaranteed food and shelter."

“Help with money for what the child needs so that more attention can be given to the child.”

While researchers have raised concern that individual interventions promote a deficit perspective of mothers with low incomes, mothers’ ratings of intervention helpfulness suggested that either mothers did not view parent-focused individual interventions as inherently stigmatizing or that they saw them as helpful despite the stigma. Mothers’ positive view of both individual and structural interventions suggested that they did not see individual interventions as unhelpful due to their focus on parent knowledge, behaviors, and states. While the distinction between individual and structural is useful for researchers in conceptualizing the different factors that shape development and can be intervened on, it is important to know that mothers view both intervention domains as potentially helpful.

Though mothers viewed all interventions very highly, mothers rated structural interventions as slightly more helpful than individual interventions. This preference could partially reflect the higher dollar value of structural interventions, which would likely defray costs in areas where mothers are already spending. Similarly, mothers’ preference for services that directly meet specific needs, versus receipt of cash that mothers then must spend, perhaps on the same underlying needs, might reflect some difficulties they experience in accessing these goods (e.g., having money on hand is less useful without good quality options to purchase). It could also, however, reflect that mothers perceived the combined costs of the resource-based services as having a higher dollar value than the $333 or $1000/month direct cash that we asked about earlier in the survey. Interestingly, among all resource-based interventions, mothers rated interventions providing affordable, high-quality child care as the most helpful by far, reflective of this pressing need in New York City where the majority of participants lived68.

More so than the individual versus structural distinction, past intervention use was associated with mothers’ ratings of intervention helpfulness. Mothers reported having used a wide variety of individual and structural interventions, and they rated interventions that they had previously used as less helpful than those they had not used. This pattern could reflect that easier-to-access interventions are seen as less helpful. It could also reflect an underlying causal effect of experiencing something negative when accessing interventions, or that the intervention’s effects on mothers’ lives fell short of expectations. To the former, past research has shown that social services are challenging to access and navigate63. To the latter, while interventions often generate effects, such effects commonly fade in the months and years following interventions18.

Suprisingly, the category with the highest past intervention use was direct cash (89%), and the lowest was access to healthy foods (48%). While SNAP food benefits are considered near-cash benefits, they are administered via a debit card, and it is possible mothers thought of these when reporting receipt of direct cash payments. There are high rates of SNAP participation in New York69. High reports of past receipt of direct cash payments could also reflect mothers’ receipt of COVID-19 stimulus checks, state or federal tax refunds, and/or Paid Family Leave benefits for working mothers in New York City.

Finally, our exploratory qualitative analysis, though limited to a reduced sample with valid responses, revealed that mothers indicated needs that could be targeted through interventions that we did not ask about. Mothers expressed the need for freed up time, greater social support (especially from other mothers), and more organized programs and activities to promote child development and socialization. Other recent qualitative analyses have found aligned endorsement for the needs captured in the latter two categories64,70,71, suggesting two promising areas for future intervention research that were revealed by consulting mothers. While this study was focused explicitly on mothers with low incomes, these qualitative findings inspire the question of whether mothers of all income levels would similarly endorse the helpfulness of various interventions, such as those that improve social supports. This could be another interesting direction for future research.

Limitations

Future research can pursue additional nuance the present study lacks. First, we did not explicitly ask mothers about whether they saw individual-directed interventions as stigmatizing, and instead relied on their ratings of intervention helpfulness as a proxy for their negative or positive feelings towards these interventions. Future qualitative research would be helpful to validate mother’s interpretation of our survey questions and to explore additional approaches to gathering information about how mothers view these issues.

Second, we do not know the specifics of the interventions that mothers envisioned when rating intervention helpfulness. Mothers may have imagined interventions that are very different from those implemented at scale both in terms of accessibility and content. The extent to which imagined interventions are like those implemented in practice could also conceivably vary across interventions and between mothers. Mothers’ ratings of intervention helpfulness did, for example, differ by past intervention use. Whereas for some mothers, the ratings may have measured evaluations of an intervention’s helpfulness grounded in experience, for others, the ratings may have captured perceptions of intervention helpfulness formed without direct intervention exposure. What underlying construct was tapped by the ratings could be a function of mothers’ experience using the intervention and other important factors. Understanding points of discrepancy in imagined versus existing programs that may change mothers’ feelings about intervention helpfulness and likelihood of intervention uptake, and how this may vary intervention-to-intervention and mother-to-mother, is an important area for future research. In the context of intervention implementation at scale, many of the issues we asked mothers not to consider—such as program affordability, convenience, and time involved—will certainly matter and shape mothers’ perceptions of intervention helpfulness.

In attempting to glean the valence of mothers’ feelings about individual and structural interventions, this study did not yield insights about what interventions mothers are likely to use or their ranked preferences in the real-world context of constrained time, energy, and resources. Indeed, under the framework of easy-to-access, affordable interventions, mothers may have been of the mind of endorsing all interventions as helpful. It is possible that in an alternate paradigm of limited resources in which mothers must make choices about which interventions are most helpful, we would see more differentiation by intervention domain. Along these lines, mothers’ responses are not reflective of how helpful interventions will be for mothers of young children with low income in reality. More long-run experimental evaluations of interventions are needed towards these ends72.

There could also be important differences in how mothers think about the helpfulness of interventions for themselves versus for others in similar circumstances to their own, the latter being what we asked about in this study. Perceptions of intervention helpfulness may also vary across different contexts that differ in social service generosity and by individual characteristics such as race, ethnicity, and citizenship status. Of note, 67% of our sample was Hispanic or Latino. Hispanic and Latino individuals make up the largest share of immigrants in NYC (31%) and may face adversities particular to that identity that shape family needs and perceptions of intervention helpfulness71,73,74. Future work could further explore heterogeneity in helpfulness perceptions by individual characteristics.

Conclusion

Mothers endorsed a wide variety of interventions as potentially helpful to parents in supporting their young children’s development under conditions of economic disadvantage. Mothers’ ratings of individual interventions as very helpful suggests that they did not view these interventions as inherently problematic due to their focus on parent states, knowledge, and skills. Or, minimally, that their concerns did not supersede their impression of potential helpfulness. Mothers’ perspectives suggest the importance of continued research and intervention development in both individual and structural areas. Future research might explore the possibility of targeting both individual and structural factors, perhaps within the context of a single intervention, with an intentional strengths-based approach. Longitudinal evaluation of experiments testing intervention efficacy will be crucial for determining whether interventions hold up to their promise of promoting long-run effects that reduce socioeconomic disparities. As researchers continue to engage in this critical area of research, the perspective of mothers with low incomes and young children should be thoughtfully incorporated as they reveal important new directions for research.

Data availability

The pre-registration, data, and analytic code for this project can be found at: https://osf.io/udwap.

References

Hoff, E., Laursen, B. & Tardif, T. In Handbook of parenting: Volume 2 biology and ecology of parenting (ed. Bornstein, M. H.) (Psychology Press, 2019). https://doi.org/10.4324/9781410612144.

Jeong, J., Franchett, E. E., de Oliveira, C. V. R., Rehmani, K. & Yousafzai, A. K. Parenting interventions to promote early child development in the first three years of life: A global systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 18(5), e1003602. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003602 (2021).

Davis, L. P., & Museus, S. D. What is deficit thinking? An analysis of conceptualizations of deficit thinking and implications for scholarly research. NCID Currents. 1(1), 117–130. https://doi.org/10.3998/currents.17387731.0001.110 (2019)

Kuchirko, Y. On differences and deficits: A critique of the theoretical and methodological underpinnings of the word gap. J. Early Child. Lit. 19(4), 533–562. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468798417747029 (2019).

NASEM. A roadmap to reducing child poverty (The National Academies Press, 2019).

Dearing, E., McCartney, K. & Taylor, B. A. Change in family income-to-needs matters more for children with less. Child Dev. 72(6), 1779–1793. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00378 (2001).

Dearing, E., McCartney, K. & Taylor, B. A. Within-child associations between family income and externalizing and internalizing problems. Dev. Psychol. 42(2), 237–252. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.237 (2006).

Noble, K. G. et al. Socioeconomic disparities in neurocognitive development in the first two years of life. Dev. Psychobiol. 57(5), 535–551. https://doi.org/10.1002/dev.21303 (2015).

Romeo, R. R., Flournoy, J. C., McLaughlin, K. A. & Lengua, L. J. Language development as a mechanism linking socioeconomic status to executive functioning development in preschool. Dev. Sci. 25, e13227. https://doi.org/10.1111/desc.13227 (2022).

DiPrete, T. A. & Eirich, G. M. Cumulative advantage as a mechanism for inequality: A review of theoretical and empirical developments. Ann. Rev. Sociol. 32, 271–297. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.32.061604.123127 (2006).

Duncan, G. J., Brooks-Gunn, J. & Klebanov, P. K. Economic deprivation and early childhood development. Child Dev. 65(2), 296–318. https://doi.org/10.2307/1131385 (1994).

Cunha, F. & Heckman, J. The technology of skill formation. Am. Econ. Rev. 97(2), 31–47 (2007).

Shonkoff, J. P., & Phillips, D. A. From neurons to neighborhoods: The science of early child development (National Research Council (U.S.), Ed.). National Academy Press (2000).

Farah, M. J. The neuroscience of socioeconomic status: Correlates, causes, and consequences. Neuron 96(1), 56–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2017.08.034 (2017).

Noble, K. G. & Giebler, M. A. The neuroscience of socioeconomic inequality. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 36, 23–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2020.05.007 (2020).

Masten, A. S. & Cicchetti, D. Developmental cascades. Dev. Psychopathol. 22(3), 491–495. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579410000222 (2010).

Bailey, D. H., Duncan, G. J., Cunha, F., Foorman, B. R. & Yeager, D. S. Persistence and fade-out of educational-intervention effects: Mechanisms and potential solutions. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 21(2), 55–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100620915848 (2020).

Hart, E., Bailey, D., Luo, S., Sengupta, P., & Watts, T. Do intervention impacts on social-emotional skills persist at higher rates than impacts on cognitive skills? A meta-analysis of educational RCTs with follow-up. EdWorkingPaper. https://doi.org/10.26300/7J8S-DY98 (2023)

Park, A. T. & Mackey, A. P. Do younger children benefit more from cognitive and academic interventions? How training studies can provide insights into developmental changes in plasticity. Mind, Brain Educ. 16(1), 24–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/mbe.12304 (2022).

Woodhead, M. When psychology informs public policy. Am. Psychol. 43(6), 443–454 (1988).

Ayoub, M. & Bachir, M. A meta-analysis of the relations between socioeconomic status and parenting practices. Psychol. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1177/00332941231214215 (2023).

Masarik, A. S. & Conger, R. D. Stress and child development: A review of the family stress model. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 13, 85–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.05.008 (2017).

Conger, R. D. et al. Economic pressure in African American families: A replication and extension of the family stress model. Dev. Psychol. 38(2), 179. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.38.2.179 (2002).

Evans, G. W., Boxhill, L. & Pinkava, M. Poverty and maternal responsiveness: The role of maternal stress and social resources. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 32(3), 232–237. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025408089272 (2008).

Dailey, S. & Bergelson, E. Language input to infants of different socioeconomic statuses: A quantitative meta-analysis. Dev. Sci. 25(3), e13192. https://doi.org/10.1111/desc.13192 (2022).

Linver, M. R., Brooks-Gunn, J. & Kohen, D. E. Family processes as pathways from income to young children’s development. Dev. Psychol. 38(5), 719–734. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.38.5.719 (2002).

Rowe, M. L. A longitudinal investigation of the role of quantity and quality of child-directed speech in vocabulary development. Child Dev. 83(5), 1762–1774. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01805.x (2012).

Bernard, K. et al. Enhancing attachment organization among maltreated children: Results of a randomized clinical trial. Child Dev. 83(2), 623–636. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01712.x (2012).

Landry, S. H., Smith, K. E., Swank, P. R. & Guttentag, C. A responsive parenting intervention: The optimal timing across early childhood for impacting maternal behaviors and child outcomes. Dev. Psychol. 44(5), 1335–1353. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013030 (2008).

McCarton, C. M. Results at age 8 years of early intervention for low-birth-weight premature infants. The infant health and development program. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 277(2), 126–132. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.277.2.126 (1997).

Michalopoulos, C., Faucetta, K., Hill, C. J., Portilla, Z. A., Burrell, L., Lee, H., Duggan, A., & Knox, V. Impacts on Family Outcomes of Evidence-Based Early Childhood Home Visiting: Results from the mother and infant home visiting program evaluation. OPRE report. https://www.mdrc.org/sites/default/files/MIHOPE_Impact_Report-Final2.0.pdf (2019).

Ryan, R. M. & Padilla, C. Public policy and family psychology. In APA handbook of contemporary family psychology: Applications and broad impact of family psychology (eds Fiese, B. H. et al.) 639–655 (American Psychological Association, 2019) https://doi.org/10.1037/0000100-039.

Suskind, D. L. et al. A parent-directed language intervention for children of low socioeconomic status: A randomized controlled pilot study. J. Child Lang. 43(2), 366–406. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305000915000033 (2016).

Whitehurst, G. J. et al. A picture book reading intervention in day care and home for children from low-income families. Dev. Psychol. 30(5), 679–689 (1994).

Moore, N. et al. The efficacy of provider-based prenatal interventions to reduce maternal stress: A systematic review. Women’s Health Issues 33(3), 300–311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2023.02.003 (2023).

Song, J., Kim, T. & Ahn, J. A systematic review of psychosocial interventions for women with postpartum stress. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 44(2), 183–192. https://doi.org/10.1111/1552-6909.12541 (2015).

Urizar, G. G. et al. Destined for greatness: A family-based stress management intervention for African-American mothers and their children. Soc. Sci. Med. 280, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114058 (2021).

Cox, J. E. et al. A parenting and life skills intervention for teen mothers: A randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics 143(3), e20182303. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-2303 (2019).

Fuji, K. T., White, N. D., Packard, K. A., Kalkowski, J. C. & Walters, R. W. Effect of a financial education and coaching program for low-income, single mother households on child health outcomes. Healthcare 12(2), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12020127 (2024).

White, N. et al. Improving health through action on economic stability: Results of the finances first randomized controlled trial of financial education and coaching in single mothers of low-income. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 17(3), 424–436. https://doi.org/10.1177/15598276211069537 (2023).

Bruno, E. P. & Iruka, I. U. Reexamining the Carolina Abecedarian Project using an antiracist perspective: Implications for early care and education research. Early Childhood Res. Q. 58, 165–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2021.09.001 (2022).

DeJoseph, M. L. et al. The promise and pitfalls of a strength-based approach to child poverty and neurocognitive development: Implications for policy. Dev. Cognit. Neurosci. 66, 101375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcn.2024.101375 (2024).

Ellwood-Lowe, M. E., Foushee, R. & Srinivasan, M. What causes the word gap? Financial concerns may systematically suppress child-directed speech. Dev. Sci. 25(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/desc.13151 (2021).

Jones, S. C. T., Simon, C. B., Yadeta, K., Patterson, A. & Anderson, R. E. When resilience is not enough: Imagining novel approaches to supporting Black youth navigating racism. Dev. Psychopathol. 35(5), 2132–2140. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579423000986 (2023).

Noble, K. G., Hart, E. R. & Sperber, J. F. Socioeconomic disparities and neuroplasticity: Moving toward adaptation, intersectionality, and inclusion. Am. Psychol. 76(9), 1486–1495. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000934 (2021).

Raver, C. C. & Blair, C. Developmental science aimed at reducing inequality: Maximizing the social impact of research on executive function in context. Infant Child Dev. 29(1), e2175. https://doi.org/10.1002/icd.2175 (2020).

Silverman, D. M., Rosario, R. J., Hernandez, I. A. & Destin, M. The ongoing development of strength-based approaches to people who hold systemically marginalized identities. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 27(3), 255–271. https://doi.org/10.1177/10888683221145243 (2023).

Taylor, E. K., Abdurokhmonova, G. & Romeo, R. R. Socioeconomic status and reading development: Moving from “deficit” to “adaptation” in neurobiological models of experience-dependent learning. Mind, Brain Educ. 17(4), 324–333. https://doi.org/10.1111/mbe.12351 (2023).

Wang, S. et al. Dismantling persistent deficit narratives about the language and literacy of culturally and linguistically minoritized children and youth: Counter-possibilities. Front. Educ. 6, 641796. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.641796 (2021).

Ellis, B. J., Bianchi, J., Griskevicius, V. & Frankenhuis, W. E. Beyond risk and protective factors: An adaptation-based approach to resilience. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 12(4), 561–587. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691617693054 (2017).

Ellis, B. J. et al. Hidden talents in harsh environments. Dev. Psychopathol. 34, 96–113. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579420000887 (2022).

McLoyd, V. C. The impact of economic hardship on Black families and children: Psychological distress, parenting, and socioemotional development. Child Dev. 61(2), 311–346. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02781 (1990).

Bronfenbrenner, U. Ecological systems theory. In Six theories of child development: Revised formulations and current issues (ed. Vasta, R.) 187–249 (Jessica Kingsley Publishers, 1992).

Garcia Coll, C. et al. An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in Minority children. Child Dev. 67(5), 1891. https://doi.org/10.2307/1131600 (1996).

Iruka, I. U. et al. Effects of racism on child development advancing antiracist developmental science. Ann. Rev. Dev. Psychol. 4(1), 109–32. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-devpsych-121020-031339 (2022).

Vasilyeva, N. & Lombrozo, T. Structural thinking about social categories: Evidence from formal explanations, generics, and generalization. Cognition 204, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2020.104383 (2020).

Chater, N. & Loewenstein, G. The i-frame and the s-frame: How focusing on individual-level solutions has led behavioral public policy astray. Behav. Brain Sci. 46, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X22002023 (2023).

Wright Mills, C. (1959). The Sociological Imagination (40th Anniversary Edition, 40th Anniversary Edition). Oxford University Press

Roubinov, D. S. & Boyce, W. T. Parenting and SES: Relative values or enduring principles?. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 15, 162–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.03.001 (2017).

Rowe, M. L. A longitudinal investigation of the role of quantity and quality of child-directed speech in vocabulary development. Child Dev. 83(5), 1762–1774. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01805 (2012).

Baralt, M., Mahoney, A. D. & Brito, N. Háblame Bebé: A phone application intervention to support Hispanic children’s early language environments and bilingualism. Child Lang. Teach. Therapy 36(1), 33–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265659020903779 (2020).

Wallerstein, N. et al. Engage for equity: A long-term study of community-based participatory research and community-engaged research practices and outcomes. Health Educ. Behav. 47(3), 380–390. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198119897075 (2020).

Butler, J., Gregg, L., Calam, R. & Wittkowski, A. Parents’ perceptions and experiences of parenting programmes: A systematic review and metasynthesis of the qualitative literature. Clin. Child Family Psychol. Rev. 23(2), 176–204. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-019-00307-y (2020).

Marti-Castaner, M. et al. Poverty after birth: How mothers experience and navigate U.S. safety net programs to address family needs. J. Child Family Stud. 31(8), 2248–2265. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-022-02322-0 (2022).

Barnes, C. Y., Halpern-Meekin, S., & Hoiting, J. They need more programs for the kids:” Low-income mothers’ views of government amidst economic precarity and burdensome programs. Int. J. Soc. Welfare, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijsw.12641 (2024) .

Pilkauskas, N. V., Currie, J. M. & Garfinkel, I. The great recession, public transfers, and material hardship. Soc. Serv. Rev. 86(3), 401–427. https://doi.org/10.1086/667993 (2012).

Cohen, S. & Williamson, G. Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In The social psychology of health (eds Spacapan, S. & Oskamp, S.) (Sage Publishers, 1988).

Alliance for Quality Education et al. The child care crisis in New York state. https://www.nysenate.gov/sites/default/files/childcaretourreport.pdf. (2021)

Karabatsos, H., Kealey, E., & Dinan, K. SNAPshot of enrollment and participation in the supplemental nutrition assistance program in New York City. https://www.nyc.gov/assets/hra/downloads/pdf/facts/snap/SNAPParticipationNYC.pdf. (2024).

Halpern-Meekin, S. Social poverty: Low-income parents and the struggle for family and community ties (NYU Press, 2019).

Ayon, C. & Kim, S. H. Latino immigrant families and restrictive immigration climate: Perceived experiences with discrimination, threat to family, social exclusion, children’s vulnerability, and related factors. Race Soc. Probl. 9(4), 300–312. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12552-017-9215-z (2017).

Watts, T. W., Bailey, D. H. & Li, C. Aiming further: Addressing the need for high-quality longitudinal research in education. J. Res. Educ. Eff. 12(4), 648–658. https://doi.org/10.1080/19345747.2019.1644692 (2019).

Mayor's Office of Immigrant Affairs. A demographic snapshot: NYC's latinx immigrant population. https://www.nyc.gov/assets/immigrants/downloads/pdf/Hispanic-Immigrant-Fact-Sheet.pdf. (2020).

Barnes, C. Y. & Gennetian, L. A. Experiences of hispanic families with social services in the racially segregated southeast: Views from administrators and workers in north carolina. Race Soc. Probl. 13, 6–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12552-021-09318-3 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This publication was supported by grant funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01HD093707-01 to KGN and R00HD104923 to SVTR), National Science Foundation (DGE-2036197 to ERH), Teachers College, Columbia University to KGN and ERH. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. We thank Tyler Watts for his helpful comments on an earlier version of the manuscript. We thank all families for their participation; and Melina Amarante, Olivia Colon, Pooja Desai, Ana Dueñas-Crespo, Diana Isabel Encinosa, Isabel Kovacs, Elaine Maskus, Dayanara Sanchez, and Ana Leon Santos for their help with data collection.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.R.H., J.F.S., S.V.T.R., and K.G.N. conceptualized of the project. E.R.H. designed the original study materials with feedback from J.F.S., S.V.T.R., S.H.M., A.S., and K.G.N. E.R.H. and P.O.F. collected the data. E.R.H. performed the quantitative analyses. E.R.H., and P.O.F. performed the qualitative analyses with guidance from S.H.M., E.R.H. wrote the initial manuscript text. All authors reviewed, revised, and approved the text.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hart, E.R., Sperber, J.F., Troller-Renfree, S.V. et al. Mothers with low incomes view both individual and structural interventions as potentially helpful for supporting early child development. Sci Rep 14, 18374 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-68762-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-68762-4

- Springer Nature Limited