Abstract

Understanding public awareness of environmental problems is vital for effectively formulating sustainable policies. This paper aims to investigate the impacts of two perspectives—external air pollution and individual health status—on public awareness by leveraging panel data from two waves of the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) conducted between 2018 and 2020. The model integrates provincial-level PM2.5 concentration indicators and SO2, PMs, and NOx emissions. The results reveal a significantly positive correlation between air pollution and public awareness of environmental problems in China. Additionally, this study examines the impact of self-assessed health shock by categorizing it into worse and better health. The influence of better health is insignificant. Conversely, when individuals experience worse health, they may perceive it as a psychological loss, leading to a significant increase in public awareness of environmental problems. This study provides valuable insights for mitigating air pollution and reinforcing public health in developing countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the growing emphasis on sustainability, there is a heightened focus from both governments and scholars on enhancing public awareness of environmental issues. This awareness forms a crucial foundation for individuals' responses and serves as a primary subjective metric for assessing local ecological performance. While environmental problems encompass various dimensions, aspects of external air pollution, such as visibility, concentration, comparability, and reliability1, are more readily perceived by individuals through environmental information disclosure. For example, a study by Xiang et al.2 further emphasizes the significance of individuals' subjective perceptions of the environment. Many respondents gather visible evidence from physical concentrations near pollution sources3. Individuals primarily rely on their direct experiences to evaluate the severity of environmental problems, and these experiences are often influenced by their individual characteristics. This stands in contrast to relying solely on technological instruments for detecting air pollutants and objectively assessing existing air pollution levels, as conducted by the scientific community4.

However, much remains unknown about the role of air pollution and health status in shaping public awareness of environmental problems in China—two interconnected aspects providing external and internal information. Consequently, this paper aims to bridge this knowledge gap on two fronts: the disclosure of air pollution and individual self-assessed health status. Individual and provincial data are integrated to explore their respective effects on public awareness of environmental problems in China. Recently, smog has posed a critical crisis in China, prompting the government to prioritize environmental pollution control. The real-time monitoring and disclosure of air pollution have increased public awareness of environmental issues5. As a significant environmental challenge, air pollution has become a decisive factor influencing sustainability6. Exposure to polluted air is a substantial risk factor for noncommunicable human diseases7. The annual average population-weighted PM2.5 concentration in China exceeded 52 μg/m3 in 2013, significantly surpassing the air quality standards set by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency8 and the WHO's Air Quality Guidelines (10 μg/m3). In response, the Chinese government implemented comprehensive policies to reduce PM concentrations by 10% within five years to combat air pollution. The population-weighted annual average PM2.5 concentration calculated in this study for 2018 was less than 37 μg/m3, indicating a nearly 29% reduction compared to the 2013 levels and partial alleviation of objective public exposure to air pollution.

Investigating the consistency of the relationship between subjective perceptions and objective air pollution indicators, especially in developing countries, is crucial. This study emphasizes that individual public awareness of environmental problems becomes more pronounced when PM2.5 concentrations are higher in their respective provinces. Robustness analysis further reveals a significant correlation between higher emissions of SO2, PMs, and NOx and individual perceptions of environmental problems. This finding underscores the substantial impact of objectively measured air pollution on subjective perceptions of environmental problems. While previous studies often explored the relationship between national economic development and environmental quality using the Environmental Kuznets Curve, our paper takes a different approach by investigating the interaction between GDP growth and actual air pollution. Moreover, this paper introduces climate productivity indicator to underscore the vital role of environmental protection in the benefits of economic growth. When done efficiently and effectively, the growth of climate productivity reduces individuals' perception of the severity of environmental problems.

Direct experiences shape individuals' perceptions of environmental problems9. Health status undoubtedly plays a significant role10, and the sensitivity of one's physical health directly influences the individual's assessment of the severity of environmental problems11. Validating this, Peng et al.4 demonstrated that higher self-rated health satisfaction corresponds to a lower perceived severity of air pollution. The saying, "As long as you are healthy, you do not give a damn, but as soon as you are sick, you are prepared to sacrifice everything to restore your health"12, encapsulates that health becomes a paramount concern when it is compromised. Therefore, this paper aims to explore whether individuals' perceived changes in health affect their evaluation of environmental pollution and whether different health states, deterioration or improvement, have distinct effects.

The subjective evaluation of individuals' health shocks may impact their perception of environmental problems. The results highlight that the effect is primarily associated with worse health, significantly increasing the perceived severity of environmental problems. In contrast, better health status does not significantly influence individuals’ perceptions, and individuals' self-assessed health status does not notably impact their environmental perceptions. A decrease in individuals' self-assessed health status may represent a psychological loss, significantly heightening their perception of the severity of environmental problems. This phenomenon is more pronounced among those under 40 years of age, indicating that declining health status greatly amplifies the perceived severity of environmental problems, especially among younger individuals.

This paper contributes to research on public awareness of environmental problems in three key aspects. Firstly, in contrast to most studies focusing on individual air pollutants, this research simultaneously estimates the impacts of multiple key air pollutants. The empirical literature on how air pollution affects public perception relies primarily on small-scale survey data from specific residents, necessitating more systematic evidence from representative samples. By doing so, this study provides a comprehensive view of geographically diverse regions with varying levels of air pollution. Secondly, while numerous studies in developed countries suggest a disparity between actual air pollution and perceived air pollution13, this study addresses the unique context of China, where air pollution is one facet of broader environmental problems. It investigates whether provincial-level air pollution influences individual public awareness of environmental problems. Finally, previous research on the perception of environmental problems has predominantly emphasized the influence of poverty and knowledge10. This study strongly emphasizes the impact of subjective health status, revealing the asymmetric effect of health status changes on environmental perception. This aspect deserves more attention in environmental perception research. Given the prevalence of air pollution in developing countries, the insights drawn from this research on China may offer valuable perspectives for other developing nations.

Related literature and research hypotheses

The relationship between objective air pollution and public awareness of environmental problems

In terms of the correlation between actual air pollution and subjective perceptions of environmental problems, existing research has consistently demonstrated a significant connection, primarily focusing on the subjective perception of air pollution problems. The visibility of air pollution and unpleasant odors have been identified as crucial factors shaping public perception, independent of individual characteristics14. Flachsbart et al.15 utilized physical data on air pollutants and meteorological indicators, employing multiple averaging periods to examine the correlation between these data and perceived and expected air quality indicators. Their findings indicated that ozone and visibility levels were more closely related to perceived air quality, among other pollutants, across all periods.

Baseline conditions influence human perception, and individuals form their perceptions based on long-term air quality trends. Oglesby et al.16 discovered that perceived outdoor air quality significantly correlates with the actual measured air quality provided by monitoring stations, increasing with increasing concentrations of suspended particles within specific size ranges17 and dust deposition18. Subjective perceptions of air quality are formed based on broader environmental pollution levels due to atmospheric pollution3,9. Grossberndt et al.19 demonstrated that simulated annual pollution concentrations are associated with individuals' subjective perceptions of air quality; their findings indicate that the spatial pattern of perceived air quality is not entirely random but rather follows, to some extent, the patterns expected due to pollution emissions.

Barwick et al.5 correlated respondents' subjective perceptions of environmental problems with the average PM2.5 concentration in their cities from 2015 to 2016, revealing a robust positive correlation between public awareness of environmental problems and pollution following the implementation of environmental monitoring policies. Peng et al.4 estimated the significant consistency between various objective air pollution indicators and perceived air pollution and found that in China, there is a significant association between public perceptions of air pollution and actual air pollution. Due to the highly tangible and visible nature of air pollution, which often affects human senses, air pollution problems are particularly severe in many parts of China, making the public more sensitive to environmental concerns. People residing in cities with poorer air quality express increased concern about pollution problems, while those in cleaner cities express less concern. Therefore, this paper posits Hypothesis 1 (H1):

Hypothesis 1 (H1) Public awareness of environmental problems significantly correlates with actual air pollution levels. Individuals living in provinces with high air pollution levels may be aware of more serious environmental problems.

The relationship between subjective health status and public awareness of environmental problems

Relying solely on objectively measured air pollution does not automatically translate into individual perceptions of environmental problems, as perception is socially constructed and influenced by personal characteristics. It is embedded with goals, values, and direct experiences related to pollution, such as proximity to pollution sources, physical health, and sensitivity3,11. When pollution, such as smoke or strong odors, is more easily noticeable and its health impacts are more severe, resulting in difficulty breathing or lung pain, respondents are more likely to be able to link health and environmental problems. Individuals with health problems, such as respiratory symptoms, are more likely to be aware of the implications of air quality problems20.

Health shocks include information like health history. When an individual experiences a negative health shock, perceiving a decline in their health compared to the previous year, they tend to be more attuned to external environmental factors. This heightened sensitivity stems from the belief that environmental pollution may have directly contributed to their health deterioration. Furthermore, those who find their health declining often feel a stronger need for clean air, as they rely on it for their well-being and survival.On the other hand, a positive health shock, such as feeling healthier than the previous year, often coincides with higher productivity and greater workforce participation, potentially boosting an individual's income. With this increased financial capability, it becomes easier to counteract the effects of environmental problems by investing in higher-quality environmental services or implementing extra precautionary measures. After experiencing such health gains, individuals tend to overlook the less obvious impacts of environmental issues on their daily routines. They may view themselves as living a healthier and more comfortable life, in which the effects of environmental problems on their quality of life are minimal. Consequently, they might not perceive the seriousness of environmental challenges as acutely as those who are in worse health.Moreover, subjective evaluation of self-assessed health can be influenced by various psychological factors. Some individuals may report lower levels of self-assessed health yet maintain a positive outlook, whereas others who rate their health higher may still express dissatisfaction with their overall quality of life. These disparities in subjective assessments could potentially weaken the observable correlation between self-assessed health and the perception of environmental problems. It is important to note that self-assessed health is a relatively subjective metric, which can be shaped by personal attitudes, life experiences, and access to medical care. Conversely, public awareness of environmental issues is likely to be influenced more heavily by factors such as education, information dissemination, and a sense of social responsibility. Therefore, this paper posits Hypothesis 2 (H2):

Hypothesis 2 (H2) Public awareness of environmental problems significantly correlates with individual health shock; individuals with worse health are aware of more serious environmental problems. In contrast, self-rated health is not significantly associated with an individual's awareness of environmental problems.

Materials and methods

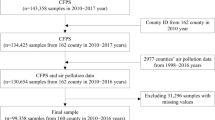

Based on the background and research questions outlined above, the framework of the research content in this article is illustrated in Fig. 1. Traditionally, government policies aimed at improving air quality have relied solely on scientific measurements of air quality outcomes. However, this approach often neglects the subjective factors related to air quality, particularly the perceptions of air users, or public awareness. In order to address this gap, this article advocates for a more holistic approach to policy formulation. It argues that effective policy-making should take into account both objective and subjective factors. By incorporating public awareness as a crucial consideration, policies can be more accurately tailored to address the needs and concerns of the community. By adopting this comprehensive approach, not only can air quality be improved, but it can also have a positive impact on subjective well-being. Enhancing public awareness and involvement in the policy-making process may lead to better outcomes for air quality as well as boost the overall physical fitness and well-being of the population.

Schematic overview of this study. Note: The air pollution figure shows the annual trend in the national concentration of PM2.5 in China from 1998 to 2021. This population-weighted and geographic-mean PM2.5 concentration series is obtained, computed, and calibrated based on the Atmospheric Composition Analysis Group's data collections and corresponding algorithms. See Sect. 3.1 for further details. Figure 1 is created by the corresponding author.

Air quality has emerged as a pivotal indicator of sustainable development. Traditionally, government initiatives aimed at enhancing air quality have relied on monitoring data, offering a targeted and highly significant approach to improving air quality. This paper introduces a novel dimension by incorporating public awareness of air quality and employing diverse measurement approaches. By adopting this investigative method, the government can gain a more comprehensive perspective when crafting policies. The resultant plan has a broader impact, not only contributing to enhanced air quality but also positively influencing the regulatory framework for survival, as well as the physical and mental health of residents. This multifaceted approach represents an innovative aspect of this paper.

Data source

This study aims to deepen the general understanding of public awareness of environmental problems and, within the context of China, investigate the impact of provincial-level air pollution indicators and individual-level characteristic variables on the perception of subjective environmental problems. The individual data used in this paper are derived from the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS), funded by Peking University (source). The CFPS survey is conducted every two years and covers 25 provinces/municipalities/autonomous regions in China. It is a nationally representative survey of Chinese communities, households, and individuals and holds theoretical and practical significance for research in China. The CFPS data collection includes individual attitudes and opinions about environmental problems, enabling the systematic identification of key factors influencing public awareness of environmental problems in China.

The annual provincial PM2.5 concentration data used in this paper are sourced from the Atmospheric Composition Analysis Group. ( Atmospheric Composition Analysis Group, Washington University in St. Louis, https://sites.wustl.edu/acag/datasets/surface-pm2-5.) This dataset is derived from instantaneous data records obtained from the Chinese Ministry of Environmental Protection website. Aerosol optical depth (Aerosol et al., AOD) retrievals from NASA MODIS, MISR, and SeaWiFS instruments are combined with the GEOS-Chem chemical transport model. Based on annual variations between GM (general monitoring) and non-GM observation periods, as detailed in Hammer et al.21, these data are gridded at the finest resolution of 0.01° × 0.01°, allowing users to aggregate the data according to their specific needs. Other provincial-level data, such as per capita GDP, GDP growth rate, sulfur dioxide emissions, nitrogen oxides, and particulate matter, are sourced from the China National Bureau of Statistics.

Variable selection and definition

Dependent variable

This study utilized data from two waves of surveys conducted in 2018 and 2020. The dependent variable, 'Public awareness of environmental problems', is based on responses to the following question: 'How would you rate the severity of the environmental problem in China?' The respondents could choose a rating on a scale from 0 to 10, ranging from 'not exist' to ‘very serious', with higher values indicating a perception of more severe air pollution. Overall, most individuals in the sample believed that China faced environmental problems and could perceive a certain level of severity. The descriptive statistics for these dependent variables in our sample that individuals from 18 to 80 years old are presented in Table 1, with the most common response being 'very severe', accounting for 22.32% of the answers in general. Different regions face distinct environmental challenges, from air pollution in industrialized areas to water scarcity in arid regions. Hence, examining the regional distribution of public awareness of environmental problems in China is vital for developing targeted and effective environmental policies. Table 1 also serves as a valuable tool for understanding these regional differences and for guiding future efforts to raise environmental awareness across the country. It can be seen that compared with residents in the central and western regions, a higher proportion of residents in the eastern region believe that China's environmental problems are very serious, with 23.43% rating it as 10, and a lower proportion of people believe that there are no environmental problems in China, with 4.38% rating it as 0.

Independent variable

The key independent variables employed in this study encompass two levels of variables: (a) provincial-level objective air pollution and (b) individual-level subjective health status.

Air pollution: Vehicle emissions, encompassing a substantial quantity of ultrafine particles with a diameter of less than 2.5 µm (PM2.5), are implicated in cardiovascular and respiratory complications. These particles can persist in the atmosphere for an extended period and traverse long distances, amplifying their impact on human health and air quality. Additionally, the transportation sector serves as a prevalent source of other air pollutants, including sulfur dioxide (SO2), a common byproduct of the combustion of fossil fuels in power generation and heating furnaces, as well as NOx. All these pollutants fall within the category of "criteria air pollutants". This study primarily focused on the particulate matter (PM2.5) indicator, using its annual average value as a proxy for air pollution, as it has become one of the major pollutants in many cities in recent years4. PM2.5 is highly perceptible and visible, often impacting human senses, and is associated with public awareness of environmental problems7. This study matches air pollution data from multiple monitoring points in each province. Weighted estimates are carried out by considering population and geography, ensuring that daily fluctuations in air quality are largely unrelated to the individual characteristics of respondents. This approach helps maintain the randomness of individuals' exposure to air pollution.

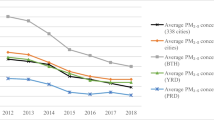

The variable 'Population-Weighted PM2.5' represents the annual concentration of ground-level delicate particulate matter (PM2.5) calibrated using Population Weighted Regression (PWR), while the variable 'Geographic-Mean PM2.5' represents the yearly average concentration of ground-level PM2.5 calibrated using Geographically Weighted Regression (GWR), with units in micrograms per cubic meter (μg/m3). In this study, the PM2.5 concentration is categorized into three intervals based on air quality standards. For instance, PM2.5 ≤ 35 μg/m3 is considered to indicate good air quality in China7, aligning with the first interim target set by the WHO. This standard is 1.4 times the European Union standard, 2.3 times that of Japan and South Korea, and 2.9 times that of Singapore and the United States. The variables pop25, pop35, and pop45 represent the population coverage percentages for PM2.5 concentrations greater than or equal to 25 μg/m3, 35 μg/m3, and 45 μg/m3, respectively. In the robustness checks, the emissions of sulfur dioxide (SO2), particulate matters (PMs) and nitrogen oxides (NOx) are measured per 10,000 tons/10,000 square kilometers (t/km3). In order to have a detailed understanding of the changes in the core indicator of The Variable 'Population Weighted PM2.5' in China, the trend of its changes from 2018 to 2020 is shown in Fig. 2:

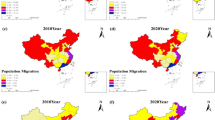

Air pollution indicators based on population-weighted PM2.5 and geographic mean PM2.5 in 2018 and 2020. Note: The first row, from left to right, represents the population-weighted annual average concentration of PM2.5 for the years 2018 and 2020, respectively. The second row, also from left to right, represents the geographic mean annual average concentration of PM2.5 for the same years. A darker color indicates a higher concentration.

As depicted in Fig. 2, from 2018 to 2020, in China, both the population-weighted PM2.5 concentration and the geographic mean PM2.5 concentration indicators exhibited a slight downward trend, albeit not significant. Throughout this period, China's air quality remained largely unchanged and consistently fell within the category of severe pollution. The data suggest that improving air quality is a gradual and long-term process. Current policies focusing solely on-air quality improvement, without considering public awareness, may not be optimal. Therefore, China's policies for air quality improvement should take into account individuals' perceptions of environmental pollution.

Health status: Health shock is measured through responses to the following question: 'How would you rate your current health status compared to a year ago?' Responses are coded as follows: 1 represents 'Worse', 2 represents 'No change', and 3 represents 'Better'. Based on the respondents' answers, two binary variables are created: 'Worse Health' is defined as one if the respondent's answer is 1 and 0 otherwise. Similarly, 'Better Health' is defined as one if the respondent answers 3 and 0 otherwise. Additionally, this study considers self-rated health, assessed based on responses to the following question: 'How would you rate your health status?' where 1 = poor, 2 = fair, 3 = good, 4 = very good, and 5 = excellent. The statistical results of the subjective health status variables are presented in Table 2.

To gain a deeper understanding of the factors influencing individual perceptions of environmental problems, urban social issues are often considered to be correlated with the economic development level of a region. This study introduces a series of individual-level control variables while controlling for provincial-level economic development indicators.

Relative income: This variable is constructed based on individuals' responses to the following question: 'What is your relative income level in your local area?' The ordinal scale ranges from 1 to 5, with higher values indicating a greater perception of relative income. The public awareness of environmental problems studied in this paper is also an important aspect of individual subjective well-being. Meanwhile, the impact of relative income level on subjective well-being (SWB) is a topic of great concern. Boyce et al. (2010)22proposed the income rank hypothesis, stating that an individual's subjective well-being depends not only on their absolute income level but more on their position within the income hierarchy. Absolute income has no direct impact on subjective well-being, whereas the relative income rank when compared to a social reference group plays a significant role. This provides a good explanation for why increasing everyone's income does not necessarily improve everyone's subjective well = being: if an individual's absolute income grows at the same rate as the rest of society, their relative income position remains unchanged, and thus subjective well-being may not improve. Individuals tend to focus more on their status within the income group, making the relative income position within the reference group more important than the absolute one (Clark and Oswald, 199623; Luttmer, 200524). Zhang et al.25 argued that individuals with lower incomes are more vulnerable to the impacts of air pollution. Lo (2014)26 suggests that there exists an inverse relationship between income and their perception of long-term environmental risks related to climate change, genetic modification of crops, and the use of nuclear energy. Compared to high-income individuals, low-income earners perceive the potential environmental consequences of these human interventions as significantly more hazardous. Wealthier individuals, on the other hand, are relatively less concerned about long-term environmental risks. A plausible explanation for this disparity is that material insecurity heightens people's sensitivity to risks and dangers. Generally, higher-income groups have more choices when dealing with environmental problems, such as purchasing air cleaners or even relocating to areas with better environmental conditions. Therefore, as relative income increases, individuals may have a decreasing perception of environmental problems.

Education: The level of education is closely linked to individuals’ ability to understand environmental problems and is measured on a scale ranging from 1 to 8, with the following corresponding categories: 1 for illiterate or semiliterate; 2 for primary school; 3 for junior high school; 4 for senior high school/vocational school/technical school/junior college; 5 for college; 6 for undergraduate; 7 for master's degree; and 8 for doctorate. In general, a higher level of education is expected to influence the subjective perception of environmental-mental problems positively.

Gender: This is a dummy variable, with 0 representing females and 1 representing males. According to Stewart et al. (2021)27, there is a preponderance of males over females in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) disciplines. They discern pronounced gender imbalances in career aspirations and lifestyle preferences, accompanied by subtler distinctions in cognitive abilities—with some advantages favoring men and others women. These disparities become more pronounced as one ventures beyond the norm. Moreover, there is persuasive evidence indicating that these gender variations are not merely societal constructs but also possess a substantial biological or genetic component. Males tend to gravitate towards science, engineering, and technology-related fields, which frequently align with environmental preservation efforts. Furthermore, in certain societies, males may wield greater social and economic influence, thereby enhancing their propensity to engage in environmental policymaking and advocacy. Consequently, this study hypothesizes that males are anticipated to perceive the gravity of environmental issues to a greater extent than females.

Age: To ensure the validity of the respondents' answers, this study restricted the age group to individuals aged between 18 and 80 years. Generally, younger individuals acquire information about environmental problems more easily through social media and online platforms. Zhang et al.7 suggested that young adults react more to air pollution than older individuals. Therefore, it is expected that age will have a negative effect on public awareness of environmental problems. Younger demographics are more likely to be attentive to environmental problems through media such as the internet, making them more sensitive to pollution. Conversely, older groups have fewer mediums to focus on environmental pollution, thus potentially being less sensitive to it. Overall, younger groups may perceive environmental pollution more severely, indicating a significant negative correlation between age and public awareness of environmental problems.

Urban: For the urban‒rural classification variable based on the National Bureau of Statistics data, 0 represents individuals whose permanent residence is in rural areas, while 1 represents those in urban areas. Research by Reeve et al.23 suggests that perceptions of pollution need to be linked to societal processes such as urbanization and industrialization. Urban residents often have higher levels of education and are more likely to receive information about the environment. Therefore, this paper posits that the urban dummy variable should be significantly positively correlated with public awareness of environmental problems.

GDP indicators: Provincial-level economic development is measured by the per capita Gross Domestic Product (GDP, in constant 2018 Chinese yuan) and the annual GDP growth rate of the respondents' respective provinces. To represent climate productivity, a logarithmic transformation is employed as a proxy. Specifically, this index is calculated by taking the logarithm of per capita GDP divided by the annual average population-weighted PM2.5 concentration (ln(GDP/PWeightedPM25)) or the annual average geographic-mean PM2.5 concentration (ln(GDP/GMeanPM25)). From an environmental burden-sharing perspective, higher GDP levels provide society with more resources to address environmental problems. High-income countries typically possess more environmental protection and healthcare infrastructure, allowing for more effective mitigation and resolution of environmental problems. This may lead individuals to perceive environmental problems as less severe because they believe society has taken appropriate measures to address them. From an alternative perspective, high-income communities may be more inclined to invest in green energy, clean production, and sustainable development, which helps alleviate environmental pressures, leading individuals to perceive environmental problems as less severe. Therefore, it is expected that per capita GDP, the GDP growth rate, and climate productivity will have negative effects on public awareness of environmental problems. Table 3 reports the descriptive statistics of all the variables used in our analysis.

Model selection

Since the dependent variable is an ordered discrete variable, we employed an ordered response model. The independent variables are represented by a vector \({X}_{it}\), which influences an individual's subjective perception of the severity of environmental problems. The dependent variable, \({y}_{it}\), reflects an individual's awareness of environmental problems. This approach implies that a latent variable \({{y}_{it}}^{*}\) that should be a mapping of \({y}_{it}\) is used to capture the internal trends in an individual's environmental awareness. We establish the general form of the panel data ordered probit model as follows:

In this equation, \({y}_{it}\) represents the public awareness of environmental problems of individual \(i\) in year \(t\), with the coefficient of interest. We also control for year fixed effects, represented by \({\tau }_{t}\), and random individual effects, represented by \({\text{e}}_{i}\). \(\varepsilon\) represents the random error following a standard normal distribution, accounting for the sum of other unaccounted factors in the model that may affect the dependent variable. Based on the classification of individual public awareness of environmental problems, the range of the continuous variable \({{y}_{it}}^{*}\) is divided into 11 intervals by setting thresholds \({\alpha }_{i}\) (where \({\alpha }_{0}<{\alpha }_{1}<{\alpha }_{2}<{\alpha }_{3}<{\alpha }_{4}<{\alpha }_{5}<{\alpha }_{6}<{\alpha }_{7}<{\alpha }_{8}<{\alpha }_{9}\)):

The probability of \({y}_{it}\) occurring in each interval, i.e., the conditional probability of \({y}_{it}\) to \({X}_{it}\), is calculated by the following equation:

Baseline results

We present the foundational findings regarding the impact of actual air pollution and individual health status on public awareness of environmental problems in Table 4. The outcomes reveal significant positive associations at the 5% level between the measured air pollution levels, including the population-weighted PM2.5 concentration, geographically weighted PM2.5 concentration, and population percentage exceeding 25/35/45 μg/m3. This apparent pattern suggests that individuals residing in provinces with elevated air pollution levels are more likely to perceive a heightened severity of environmental problems in China.

Among individual characteristics, deteriorating health status has a statistically significant positive effect on an individual's public awareness of environmental problems. This implies that individuals with poorer physical conditions are more inclined to perceive environmental problems as more severe. This aligns with our expectation that those who perceive a decline in their health are more likely to attribute this decline, at least partially, to the external environment, resulting in a heightened perception of environmental problems.

In contrast, a negative correlation exists between improved health and public awareness of environmental problems, but this correlation was not statistically significant. This suggests that when experiencing an enhancement in their health, individuals may not necessarily attribute it to the external environment, rendering them less sensitive to environmental problems. Similarly, while self-rated health status correlates positively with public awareness of environmental problems, the relationship is not significant. This indicates that an individual's attention is significantly heightened when their health deteriorates, whereas improvements in health or self-rated health status do not yield a statistically significant impact.

At the individual level, various control variables indicate a significant negative correlation between relative income and public awareness of environmental problems. This finding aligns with the conclusion drawn by Peng et al.4 that individuals with higher incomes tend to exhibit lower levels of awareness regarding air pollution. Individuals in higher self-reported income brackets tend to express less concern about environmental problems. This phenomenon can be attributed to the increased mobility options available to higher-income individuals. They often possess more excellent economic resources to address pollution problems or seek out cleaner living environments. If people perceive the environmental quality in their residence to be unsatisfactory, they are more inclined to contemplate relocating to areas with better environmental conditions.

Moreover, higher levels of education are positively associated with increased public awareness of environmental problems and knowledge. The response to air quality may vary depending on one's level of education. People with higher education levels are more likely to be aware of the implications of air pollution24 For instance, lower education levels may constrain an individual's capacity to access and comprehend information about air quality25,26. Elevated educational attainment typically enhances an individual's awareness of environmental challenges. As individuals progress in their educational levels, they amass a more extensive reservoir of knowledge and gain access to channels for understanding environmental problems. Consequently, they tend to assign greater significance to the severity of environmental problems.

Regarding gender differences in terms of the severity of environmental problems in China, men's attention is more sensitive to environmental problems, which might be related to the distribution of occupations and industries. China's labor market exhibits gender disparities, with men and women having distinct distributions across various industries and professions. Some industries, such as heavy and mining, often have more detrimental environmental impacts, and men tend to be overrepresented in these sectors. Consequently, men may be more likely to directly experience severe environmental problems due to their greater involvement in pollution-related industries.

In addition, younger individuals tend to be more attuned to the seriousness of environmental problems than their older counterparts. Zhang et al.7 provide possible explanations for this phenomenon. Firstly, older individuals may be more accustomed to living in polluted air. Secondly, younger individuals spend more time outdoors than do their elderly counterparts. Thirdly, young people may be more attentive to air quality due to their easy access to smartphones and the internet, which enables them to stay informed about air pollution. Furthermore, our findings indicate gender disparities in response to air pollution, consistent with the findings of Ebenstein et al.27.

Urban areas usually have more developed information channels, including the internet, media, and social networks. This makes it easier for urban residents to access relevant information about environmental issues. In contrast, information access in rural areas may be relatively limited, leading to a lesser understanding of environmental problems. Additionally, urban residents typically have higher levels of education, enabling them to comprehend environmental science and related issues more effectively. Educated individuals are likely to be more concerned about environmental problems and to form a deeper understanding of these issues. The significant positive correlation between the Urban dummy variable and public awareness of environmental problems in our empirical results further confirms this speculation.

Individuals in provinces with higher per capita GDP are more likely to perceive environmental problems as less severe. Regions with higher per capita GDP typically offer a higher standard of living, including better housing, education, healthcare, and social welfare. Individuals in these areas may feel that they live in a relatively comfortable and healthy environment, resulting in lower awareness of environmental problems. They may prioritize improving their quality of life and pursuing economic prosperity over addressing environmental concerns.

Similarly, the growth rate of provincial GDP exhibits a significant negative correlation with individual public awareness of environmental problems. A higher GDP growth rate may be associated with more significant opportunity costs. Individuals may believe that allocating resources to environmental protection could slow economic growth, reducing economic prospects. Consequently, they may be more willing to sacrifice some environmental quality for greater economic growth. The year 2020 dummy variable has a significant negative impact, indicating a decreasing trend in individual public awareness of environmental problems compared to that in 2018. This might be related to an overall improvement in the environment.

Robustness test

Transforming the dependent variable

In this section, we conducted a series of regressions to examine the robustness of our main results. As shown in Fig. 3, the median subjective perception of the severity of environmental problems is 7, and the average level is 6.6. Therefore, in robustness tests, we transformed the dependent variable into a binary variable, using six as the threshold. When an individual's rating of environmental issue severity is less than or equal to 6, binary public awareness of environmental problems is defined as 0. When an individual's rating of environmental issue severity is greater than 6, binary public awareness of environmental problems is defined as 1.

When we transformed the 11-level dependent variable into a binary 0–1 variable, the regression results (see Table 5) were broadly consistent with the baseline regression. These findings indicate that individuals become more aware of environmental problems as air pollution worsens. A significant deterioration in health significantly enhances individuals' awareness of environmental problems, while the effects of improved health and self-rated health status are not statistically significant.

Transforming the independent variable

Another potential estimation issue pertains to choosing proxy variables for air pollution. To address this concern, we replaced the proxy variable for air pollution with the annual average emissions of major air pollutants, including sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, and particulate matter, per unit area for each province. We conducted regression analysis using the logarithmic form rather than the linear form. As shown in Table 6, this alternative approach demonstrates a significant positive correlation between air pollution and a decline in individuals’ awareness of environmental problems and health. However, the effects of improved health and self-rated health status remain statistically insignificant, consistent with the baseline regression results.

Heterogeneity

Regional-level heterogeneity

To delve deeper into the public awareness of environmental issues across various regions in China, this study categorizes China into central and western regions, as well as eastern regions. Subsequently, it performs segmented regression analysis on the public awareness of environmental problems in these distinct regions. The detailed findings are presented in Table 7.

In both the central and western regions and the eastern region, air pollution significantly enhances individuals’ perceptions of environmental problems. A worsening health status also significantly impacts public perception, while improving health status is not significant. Individuals' subjective perceptions of environmental problems exhibit regional heterogeneity. Compared to individuals in the eastern region, individuals living in China's central and western regions tend to be more sensitive to changes in their health status because of their perception of environmental pollution. For individuals residing in China's central and western regions, a decline in their health status leads to a more pronounced awareness of the severity of environmental problems.

The eastern region is generally more prosperous than the central and western regions are, with a higher per capita GDP and more economic opportunities. Due to their higher economic status, individuals in the eastern region often enjoy a higher standard of living and better environmental quality. Consequently, they may be less sensitive to environmental problems, given their greater ability to mitigate the impact of such problems. In contrast, individuals in the central and western regions may rely more on local environmental resources, and their lower economic status may increase their susceptibility to the adverse effects of environmental pollution, thus heightening their concern for environmental problems. These findings are only relatively rough, and additional detailed research awaits further exploration.

Age-level heterogeneity

To delve deeper into the public awareness of environmental issues at the individual level in China, this study divides individuals into two groups: those younger than 40 years old and those 40 years old or older. Subsequently, it conducts segmented regression analysis on the public awareness of environmental problems within these individual groups. The specific results are shown in Table 8.

Across different age groups, air pollution significantly increases public awareness of environmental problems. Differences in the perception of environmental problems exist among various age groups. Among younger individuals, a decline in health significantly enhances their awareness of environmental problems. In other words, for individuals younger than 40 years, a deterioration in health leads to a noticeable increase in their perception of the severity of environmental pollution problems, whereas this effect is not significant for older age groups.

On the one hand, younger people may have easier access to and a better understanding of environmental problems, particularly health and pollution information. They are more likely to use tools such as the internet and social media to gather environmental information, thus helping them to gain a deeper understanding of the severity of environmental problems. This ability to acquire knowledge and information may increase their sensitivity to environmental problems. On the other hand, younger people are often in the early stages of their careers and may be more reliant on employment and economic opportunities. These individuals may be more susceptible to the impact of declining health on their employment and economic prospects, increasing their sensitivity to environmental problems. If their health is threatened, they may be concerned about the potential impact on their economic future, thus paying closer attention to environmental problems, especially health and pollution.

lncome-level heterogeneity

In economic terms, individuals can be classified into five levels based on their subjective perception of income, with levels 1 to 2 considered as the low-income group and levels 3 to 5 as the middle- and high-income group. This classification not only reflects differences in socioeconomic status but also profoundly influences individuals' perception of and response to environmental pollution. Specifically, when considering the relationship between the air pollution index of the province where individuals reside and their perception of environmental pollution, a notable phenomenon emerges: as the air pollution index rises, the perception of environmental pollution generally increases across all income groups. However, there is significant heterogeneity in how changes in individual health status affect environmental pollution perception among different income levels. The specific results are shown in Table 9.

For the low-income group, despite potentially being exposed to more severe environmental pollution, deterioration in health status does not significantly enhance their perception of environmental pollution. This phenomenon can be attributed to multiple factors: firstly, low-income groups often face more pressing survival pressures, with their attention focused more on meeting basic living needs rather than long-term issues such as environmental pollution; secondly, limited by educational resources and information access channels, this group may have insufficient understanding of the health risks associated with environmental pollution; furthermore, lower income levels restrict their options for improving living conditions or adopting protective measures, thereby weakening their sensitivity to environmental pollution to some extent.

Conversely, for the middle- and high-income group, deterioration in health status significantly increases their perception of environmental pollution. This finding can be explained from several aspects: firstly, the middle- and high-income group generally has a higher level of education and stronger information access capabilities, enabling them to more comprehensively understand the complex relationship between environmental pollution and health; secondly, higher income levels grant them more choices, including migrating to areas with better environmental quality and adopting advanced air purification technologies, thereby enhancing their direct experience of the impacts of environmental pollution; finally, with an improvement in quality of life, the middle- and high-income group is more concerned about personal health and quality of life, making environmental pollution, as a potential health threat, a highly relevant issue for them.

Discussion

Mechanism analysis

The interaction coefficient of the air pollution variable with the GDP growth rate is significantly positive, and in this case, the coefficient of the air pollution variable itself becomes nonsignificant (as shown in Table 10). This finding suggests that in provinces with higher levels of air pollution and faster GDP growth, individuals perceive environmental problems more prominently. Higher GDP growth is typically associated with accelerated economic development and industrialization and is often accompanied by increased production activities and resource utilization. This can lead to more severe air pollution, as industrial and manufacturing processes tend to emit pollutants. When GDP growth rates are high, environmental problems may become more prominent, as the expansion of economic activities results in increased pollution. Rapid GDP growth may also lead to heightened government and societal attention to environmental concerns. To mitigate environmental pressure, governments may adopt more proactive environmental policies and stricter regulations. This can increase individuals’ sensitivity to environmental problems, which may increase overall public awareness of environmental problems.

The interaction term between age and the health dummy variable is significantly negative. In contrast, the interaction term between the age variable and the Better Health dummy variable does not significantly impact individuals' public awareness of environmental problems. These findings show that younger individuals experiencing deteriorating health are more likely to experience environmental problems. As individuals age, the risk factors associated with health shocks increase, and older age groups are less likely to attribute their declining health to environmental problems.

Climate productivity

The issue of environmental pollution during economic development has received significant attention from the Chinese government. Efficiency assessments that do not consider environmental costs can incentivize local authorities to prioritize GDP-driven economic development. However, such a growth model is not conducive to sustainable economic development. To address environmental constraints during economic development and maintain harmonious and sustainable development of the economy, resources, and the environment, environmental protection has been a prominent concern for the Chinese government since 20034. Reforms have been implemented for GDP-based assessment standards, and in 2004, the National Bureau of Statistics of China initiated the "climate productivity Accounting" project.

This paper measures "climate productivity" by dividing per capita GDP by an air pollution proxy variable. This represents the positive effects of national economic growth. A higher proportion of Climate productivity in total GDP signifies a greater positive and lower negative impact on economic growth. As shown in the regression results in Table 11, climate productivity significantly reduces individuals' perception of environmental problems. This can be explained from three perspectives.

Firstly, economic growth and environmental improvement, "climate productivity" reflects whether environmental improvements accompany the country's economic growth. If the country implements environmentally friendly policies alongside economic growth, environmental quality will likely improve. This environmental improvement can reduce individuals' perception of environmental problems because they experience a better environment.

Secondly, environmental investment and knowledge: National investments and policies in green economics may increase people's awareness and knowledge of environmental problems. In a more environmentally conscious economy, individuals are likely to have better access to environmental education and information, allowing them to better understand environmental problems' complexities. As a result, they are more likely to approach environmental problems rationally and are less prone to worry.

Thirdly, the standard of living and well-being, economic growth can increase people's living standards and overall well-being. When basic needs are met, individuals may focus on other aspects of life quality, such as the environment. Therefore, in relatively affluent countries, individuals may place greater emphasis on environmental problems and be less affected by their negative consequences. Consequently, an increase in climate productivity is beneficial for alleviating individuals' concerns about environmental problems.

Policy implications

Based on our research, we outline four strategic policy recommendations aimed at fostering heightened environmental awareness, strengthening protection measures, and advancing sustainable development globally. Firstly, tailored environmental education acknowledges the diverse perspectives held by different income groups towards environmental issues. For low-income communities, we advocate for community-centered initiatives and accessible public lectures to ignite their environmental consciousness. Conversely, middle- and high-income segments should be engaged through in-depth professional reports, seminars, and workshops, fostering a deeper comprehension of environmental challenges and fostering a stronger commitment to conservation efforts.

Secondly, intensifying health-related publicity underscores the critical link between environmental pollution and public health, particularly for middle- and high-income demographics. We propose targeted awareness campaigns that educate these groups on the adverse health effects of pollution, empowering them to recognize and mitigate potential health risks associated with environmental degradation.

Thirdly, differentiated protection policies emphasize the need to tailor environmental policies to account for the disparities in perception and impact across income groups. For low-income areas disproportionately affected, stricter regulations must be prioritized to alleviate their environmental burden. Furthermore, we recommend bolstering air quality monitoring systems, implementing tailored regulations in rapidly growing economic regions plagued by severe pollution, integrating environmental costs into Green GDP metrics to promote holistic economic evaluation, and investing in environmental education and advocacy to encourage wider conservation efforts.

Lastly, green economic growth & public participation highlights the importance of nurturing green economic growth by incentivizing sustainable industries and eco-innovation. Concurrently, we underscore the need to establish mechanisms that motivate and facilitate public involvement in environmental protection, including volunteering opportunities, community events, and monitoring initiatives. This collaborative stewardship not only fosters a deeper sense of responsibility but also lays the foundation for a more resilient and environmentally sustainable future.

Conclusion

This paper utilizes Chinese panel data from an ordered probit regression model to investigate the influence of two informational aspects—air pollution and health status—on individuals' public awareness of environmental problems. This inquiry holds significant policy relevance globally, aiming to enhance public scrutiny in environmental protection efforts. Expanding on regional and individual heterogeneity discussions, the study also explores the underlying mechanism and climate productivity index.

First, after accounting for provincial-level economic factors and individual characteristics, this paper establishes the significant consistency between actual air pollution (represented by PM2.5, emissions of sulfur dioxide, particulate matter, and nitrogen oxides) and individuals' subjective perceptions of environmental problems. This underscores the pivotal role of air quality variations across different regions in China in shaping individual perceptions of environmental problems. The study emphasizes the heightened concern for environmental problems in areas with more severe air pollution than developed countries. Furthermore, this phenomenon intensifies as GDP growth rates increase. Regions with more severe air pollution and higher GDP growth rates correspond to individuals perceiving environmental problems as more severe.

Additionally, this study delves into the asymmetric influence of individual health status on the perception of environmental problems. A noteworthy finding is that when an individual's health status deteriorates, his or her perception of the severity of environmental problems significantly increases. However, the impact of improved health status and self-rated health needs further examination for clarity. This finding suggested that there is a close relationship between individual health status and external environmental quality. When individuals experience declining health, they become more sensitive to the severity of environmental problems, particularly in China's central and western regions and among individuals under 40 years of age. Individuals may be more inclined to attribute this to poor environmental quality, as subpar environmental conditions can exacerbate health problems.

This paper significantly contributes to the literature on the public perception of environmental problems. Firstly, large-scale survey data are combined with specific provincial-level data to systematically evaluate the impact of macroeconomic and microeconomic factors on public awareness of environmental problems in China. Secondly, in contrast to potential differences in perceptions among demographic groups that may exist in developing countries, often referred to as saturation effects or baseline-condition effects4, this study reveals heterogeneity in the perception of environmental problems at the regional and individual levels. Thirdly, this paper finds that objective air pollution and subjective health status significantly influence an individual's public awareness of environmental problems. Specifically, changes in health status exhibit asymmetry, with a deterioration significantly increasing individuals' perception of environmental pollution, while an improvement in health status does not significantly impact health status.

This study has several limitations that warrant further in-depth research. Firstly, the research did not consider whether the variables of interest are culturally dependent. Local cultural resources often influence public perceptions, relying heavily on individuals' experiences. Future research could explore the influence of cultural factors and conduct cross-cultural comparisons. Secondly, monitoring stations typically record environmental concentrations at relatively infrequent intervals (Levinson, 2012), while air pollution data are often aggregated over extended periods, such as a year (Ferreira et al., 2013). Consequently, matched air pollution may differ from actual exposure, potentially introducing measurement errors that could bias estimates. Thirdly, this study included only a limited number of individual characteristics. Future research could compare differences across other developing countries. In summary, these limitations provide opportunities for further investigation and analysis.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Grossman, G. M. & Krueger, A. B. Economic growth and the environment. Q. J. Econ. 110(2), 353–377. https://doi.org/10.3386/w4634 (1995).

Xiang, Z., Hasan, A., Mao, D., Saeed, M. K. & Mirza, F. Unraveling the impact of eco-centric leadership and pro-environment behaviors in healthcare organizations: Role of green consciousness. J. Clean. Prod. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.139704 (2023).

Bickerstaff, K. & Walker, G. Public understandings of air pollution: the ‘localisation’of environmental risk. Global Environ. Change 11(2), 133–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-3780(00)00063-7 (2001).

Peng, M., Zhang, H., Evans, R. D., Zhong, X. & Yang, K. Actual air pollution, environmental transparency, and the perception of air pollution in China. J. Environ. Dev. 28(1), 78–105. https://doi.org/10.1177/1070496518821713 (2019).

Barwick, P.J., Li, S., Lin, L., et al. From fog to smog: The value of pollution information. National Bureau of Economic Research (2019).

Vennemo, H., Aunan, K., Lindhjem, H., & Seip, H. M. Environmental pollution in China: Status and trends. https://doi.org/10.1093/reep/rep009 (2009).

Xie, T., Yuan, Y. & Zhang, H. Information, awareness, and mental health: Evidence from air pollution disclosure in China. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeem.2023.102827 (2023).

Zhang, X., Zhang, X. & Chen, X. Happiness in the air: How does a dirty sky affect mental health and subjective well-being?. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 85, 81–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeem.2017.04.001 (2017).

Howel, D., Moffatt, S., Bush, J., Dunn, C. E. & Prince, H. Public views on the links between air pollution and health in Northeast England. Environ. Res. 91(3), 163–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0013-9351(02)00037-3 (2003).

Saksena, S. Public perceptions of urban air pollution risks. Risk Hazards Crisis Public Policy 2(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.2202/1944-4079.1075 (2011).

Bickerstaff, K. & Walker, G. The place (s) of matter: matter out of place–public understandings of air pollution. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 27(1), 45–67. https://doi.org/10.1191/0309132503ph412oa (2003).

Zweifel, P. The Grossman model after 40 years. Eur. J. Health Econ. 13(6), 677–682. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-012-0420-9 (2012).

Schwartz, J. Clearing the air. Regulation 26, 22 (2003).

Malm, W., Kelley, K., Molenar, J. & Daniel, T. Human perception of visual air quality (uniform haze). Atmos. Environ. 15(10–11), 1875–1890. https://doi.org/10.1016/0004-6981(81)90223-7(1981) (1967).

Flachsbart, P. G. & Phillips, S. An index and model of human response to air quality. J. Air Pollut. Control Assoc. 30(7), 759–768. https://doi.org/10.1080/00022470.1980.10465106 (1980).

Oglesby, L. et al. SAPALDIA Team. Validity of annoyance scores for estimating long-term air pollution exposure in epidemiologic studies: The Swiss Study on Air Pollution and Lung Diseases in Adults (SAPALDIA). Am. J. Epidemiol. 152(1), 75–83. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/152.1.75 (2000).

Stalker, W. W. & Robison, C. B. A method for using air pollution measurements and public opinion to establish ambient air quality standards. J. Air Pollut. Control Assoc. 17(3), 142–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/00022470.1967.10468959 (1967).

Schusky, J. Public awareness and concern with air pollution in the St. Louis metropolitan area. J. Air Pollut. Control Assoc. 16(2), 72–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/00022470.1966.10468444 (1966).

Grossberndt, S. et al. Public perception of urban air quality using volunteered geographic information services. Urban Plan. 5(4), 45–58. https://doi.org/10.17645/up.v5i4.3165 (2020).

Maione, M., Mocca, E., Eisfeld, K., Kazepov, Y. & Fuzzi, S. Public perception of air pollution sources across Europe. Ambio 50, 1150–1158. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-020-01450-5 (2021).

Hammer, M. S. et al. Global estimates and long-term trends of fine particulate matter concentrations (1998–2018). Environ. Sci. Technol https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.0c01764 (2020).

Boyce, C. J., Brown, G. D. & Moore, S. C. Money and happiness: Rank of income, not income, affects life satisfaction. Psychol. Sci. 21(4), 471–475 (2010).

Clark, A. E. & Oswald, A. J. Satisfaction and comparison income. J. Public Econ. 61(3), 359–381 (1996).

Luttmer, E. F. Neighbors as negatives: Relative earnings and well-being. Q. J. Econ. 120(3), 963–1002 (2005).

Zhang, X., Zhang, X. & Chen, X. Valuing air quality using happiness data: the case of China. Ecol. Econ. 137, 29–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2017.02.020 (2017).

Lo, A. Y. Negative income effect on perception of long-term environmental risk. Ecol. Econ. 107, 51–58 (2014).

Stewart-Williams, S. & Halsey, L. G. Men, women and STEM: Why the differences and what should be done?. Eur. J. Person. 35(1), 3–39. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890207020962326 (2021).

Reeve, I., Scott, J., Hine, D. W. & Bhullar, N. This is not a burning issue for me": how citizens justify their use of wood heaters in a city with a severe air pollution problem. Energy Policy 57, 204–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2013.01.042 (2013).

Liao, X. et al. Residents’ perception of air quality, pollution sources, and air pollution control in Nanchang. China. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 6(5), 835–841. https://doi.org/10.5094/APR.2015.092 (2015).

Van Donkelaar, A. et al. Regional estimates of chemical composition of fine particulate matter using a combined geoscience-statistical method with information from satellites, models, and monitors. Environ. Sci. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.8b06392 (2019).

J., Li, S., Lin, L., & Zou, E. From fog to smog: The value of pollution information (No. w26541). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://www.nber.org/papers/w26541 (2019).

Ebenstein, A., Lavy, V. & Roth, S. The long-run economic consequences of high-stakes examinations: Evidence from transitory variation in pollution. Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 8(4), 36–65. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.20150213 (2016).

Funding

This research was primarily funded by the China National Funds of Social Science, Key Program Grant Number No.23ATJ002.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the conception and design of the study. C.W.: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Resources, Software, Visualization, Methodology, Original draft preparation, Review & editing. J.C.: Formal analysis, Software, Visualization, Methodology, Review & editing. All the authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, C., Cao, J. Air pollution, health status and public awareness of environmental problems in China. Sci Rep 14, 19861 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69992-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-69992-2

- Springer Nature Limited