Abstract

Globally, cancer is the second leading cause of death, with a growing burden also observed in Kazakhstan. This study evaluates the burden of common cancers in Almaty, Kazakhstan's major city, from 2017 to 2021, utilizing data from the Information System of the Ministry of Health. In Kazakhstan, most common cancers among men include lung, stomach, and prostate cancer, while breast, cervical, and colorectal cancers are predominant among women. Employing measures like disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), we found that selected cancer types accounted for a total DALY burden of 25,016.60 in 2021, with mortality contributing more than disability (95.2% vs. 4.7%) with the ratio of non-fatal to fatal outcomes being 1.4 times higher in women than in men. The share of non-fatal burden (YLD) proportion within DALYs increased for almost all selected cancer types, except stomach and cervical cancer over the observed period in Almaty. Despite the overall increase in cancer burden observed during the time period, a downward trend in specific cancers suggests the efficacy of implemented cancer control strategies. Comparison with global trends highlights the significance of targeted interventions. This analysis underscores the need for continuous comprehensive cancer control strategies in Almaty and Kazakhstan, including vaccination against human papillomavirus, stomach cancer screening programs, and increased cancer awareness initiatives.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The disability-adjusted life year (DALY) was introduced by the World Bank in 1993 to assess the worldwide burden of disease and help in prioritizing the development of health policies1. The DALY is a quantitative measure that combines both death (measured in years of life lost owing to premature mortality [YLL]) and disability (measured in years lived with disability [YLD]) over a specific period of time. Thus, the main aim of the burden of disease concept is to make disease and death comparable on a unified scale, which is the YLL, allowing for ranking of the impacts of different diseases on population health. To this end, adjustments are made when calculating YLD using disability weights (DW) to weight disease in populations according to level of severity.

Cancer has become the second most common cause of death worldwide2, estimated at over 18.1 million new cases (without non-melanoma skin cancer) and nearly 10.0 million cancer-related deaths in 20203. This makes cancer the main obstacle to increasing life expectancy in all countries worldwide4. The burden of malignant diseases continues to increase globally. A 47% rise in cancer incidence is projected on a global scale by 2040, with most of this increase in transitioning countries owing to population growth and aging3. The most prevalent types of malignant neoplasm are breast, lung, colorectal, prostate, stomach, and cervical cancers5. Kazakhstan belongs to the countries with a high-middle Socio-Demographic index (SDI) (0.723 in 2019) and is in the early stages of demographic aging with an increasing proportion of older people in the age structure of the country's population (7.1% in 2009 and 8.3% in 2023) and city residents (56.1% in 2009 and up to 61.2% in 2023)6,7. Kazakhstan is a country with a relatively young population with high under age 25 fertility rate of 0.867 (over 60% higher than in average in high-middle SDI group of countries, which in year 2019 was 0.537)8. At the same time, the socio-economic and cultural landscape of Kazakhstan is characterized by significant differences between urban and rural areas and by a multi-ethnic population, both being related with varying health outcomes and unequal access to health services.

Quantifying the burden of cancer is an important tool for cancer control policies, resource allocation, and health system planning9,10. The high share of YLL in the burden of most cancer types points to the need for prioritizing resources toward prevention, early detection, and health care to increase survival in patients with cancer. However, an increasing share of YLD indicates improved early detection and better survival. This would bring the focus of health care to improve quality of life among patients with cancer, to avoid progression and to achieve cure in some cases.

One example of the escalating impact of the cancer burden involves malignancies of the respiratory tract11. According to the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study, tracheal, bronchus, and lung cancer (i.e., lung cancer) rank among the 20 leading causes of DALYs globally, rising from the 20th position in 2000 (32,285,637.30 DALYs) to the 14th position in 2019 (45,857,963.50 DALYs)10. However, there has been a similar rise in the DALYs for nearly all types of cancer globally, excluding stomach cancer, liver cancer secondary to hepatitis B, Hodgkin lymphoma, and leukemia, demonstrating an increasing burden of cancer in both developed and developing countries. In Kazakhstan, the DALYs for lung cancer ranked 13th (99,097.82) in 2000 and shifted to 9th (118,130.34) place in 2019. After lung cancer, the most notable rise in DALYs is observed in colorectal, breast, and pancreatic cancers11.

In 2019, according to the GBD study, all diseases and injuries in Kazakhstan amounted to 5.8 million DALYs, of which approximately 600,000 were associated with malignant neoplasms. Compared with countries in the Central Asia region (9.5%), the proportion of DALYs associated with cancer in Kazakhstan (10,4%) is slightly higher than that in Uzbekistan (7.7%), Kyrgyzstan (7.6%), and Tajikistan (6.7%) and is lower than that in other neighboring countries (Azerbaijan 11.5%, Armenia 15.8%, Mongolia 14.6%)12.

During 2021 in Kazakhstan, of 32,572 registered new cases of cancer, the most common types were breast (15.4%), lung (11.1%), stomach (7.9%), cervical (5.5%), lymphatic and hematopoietic (5.3%), colon (5.2%), and rectal (4.9%) cancers. Cancer of the lung, stomach, and prostate were the leading pathologies in the male population whereas breast, cervical and colorectal cancer predominated among women. According to the oncological registry of the Republic of Kazakhstan, in 2021 the city of Almaty exhibited a lower incidence and mortality rates for lung, stomach, rectal, and cervical cancers compared with the national averages across Kazakhstan. Conversely, analogous indicators for breast cancer, colorectal cancer, and prostate cancer surpassed the nationwide averages13.

To our knowledge, no studies have been conducted to assess DALYs attributed to cancer on a regional level in Kazakhstan. Therefore, the objective of our study was to assess the prevalence, mortality, and DALYs associated with the most frequent types of cancer based on the best available national data sources in the largest city of Kazakhstan, namely, Almaty. The results were compared with existing estimates for other capitals or large cities in high-, middle-, and low-income countries to better assess the cancer epidemiology in Kazakhstan.

Methods

This study was conducted in Almaty, the most populous city in Kazakhstan, which had approximately 2 million inhabitants as of 2021. The study was roughly based on the GBD study methodology11. This study was carried out as part of the project CATINCA (Capacities and Infrastructures for Health Policy Development). The burden associated with the most prevalent cancer types in both sexes was determined using data from annual reports of the oncological service of the Republic of Kazakhstan from 2017 to 202113. The burden of cancer was assessed using the DALY indicator, which is the sum of YLD and YLL14. This indicator reflects the loss of life years owing to non-fatal and fatal consequences of disease15.

Types of cancer

This study included six types of cancer with the corresponding International Classification of Disease Tenth Revision codes, corresponding to the GBD study: cancer of the trachea, bronchus, and lung (i.e., lung cancer, C33–C34.9), colorectal cancer (C18–C21.9), stomach cancer (C16–C16.9), breast cancer (C50–C50.9), cervical cancer (C53–C53.9), and prostate cancer (C61–C61.9). In 2017, the most common cancer types by incidence in Kazakhstan for both sexes were breast, lung, colorectal, stomach, cervical, and prostate cancers13. These cancers (except stomach cancer) are also among the most common cancers in Europe. Colon cancer and rectal cancer are recorded separately in the oncological register of Kazakhstan and were combined into one group for the calculations. At the same time, rectal cancer and anal cancer were combined (C19–C21) and included in the colorectal cancer group. Breast cancer in men is generally rare; therefore, only women were included in the calculations. Isolated cases of cervical cancer in men were also recorded in the data and assigned to women.

Population data and standardization

Population data for Almaty were taken from public sources, namely, the Agency for Strategic Planning and Reforms of the Republic of Kazakhstan and the Bureau of National Statistics website, based on the national population census, the most recent of which took place in 2009 and 202116. The population of Almaty ranged from 1,553,267 in 2017 to 1,977,258 people in 2021, making up between 8.5 and 10.5% of the total population of Kazakhstan. The direct method of standardization was applied using the GBD 2019 World Standard Population17.

Mortality data and YLL calculation

Data from the Information System of the Ministry of Health (ISMH) of the Republic of Kazakhstan on the incidence and mortality for selected types of cancer were provided upon request by the Republican Center for Electronic Health (RCEZ) of the Ministry of Health, where data are collected on numerous public health indicators, including the oncological registry of Almaty. Upon request, aggregated cancer mortality data were provided, broken down by disease code, age group, sex, and year of death in the city of Almaty. There were 18 age groups in total, in 5-year intervals from age 0 to 85 years and older. Because mortality data were only provided from 2017 onward, all calculations were for the period from 2017 to 2021. Mortality data provided by the RCEZ were reconciled with annual reports from the oncological service of the Republic of Kazakhstan. The match between the two sources was 98–99% over the different years.

Using YLL, the disease-specific impact of mortality on population health is measured, considering the age of deceased individuals. Thus, the YLL reflects the burden of disease in terms of the statistically identified number of potential years of life not lived, and therefore, the number of life years lost owing to mortality. In the present YLL calculation, the GBD 2017 standard life expectancy table was used, which was derived from the minimum observed mortality risk within each 5-year age category across national populations worldwide exceeding 5 million inhabitants (the so-called aspirational life expectancy). The GBD tables provide one uniform life expectancy for both sexes18. Life expectancy corresponding to the midpoint of the 5-year age range was used to calculate age-specific YLL. YLL for all cancers for each sex and by age were calculated using the formula:

where I is the age group, D is the number of deaths, and RLE is residual life expectancy.

GBD standard life expectancies allow for comparisons of YLL between countries. However, the actual life expectancy in the Republic of Kazakhstan, and thus, the realistic number of YLL, are considerably lower. Comparisons of GBD life table life expectancy estimations by the World Health Organization (WHO), based on national Kazakh vital statistics, can be seen in Supplementary Fig. 1.

In line with the current GBD methodology and the WHO, we did not discount future unlived years and we did not weight according to age19.

Prevalence data and YLD calculation

As in the GBD study we used 10-year-prevalence as the basis to calculate YLD. However, we used Kazakh registry data in order to directly estimate the 10-year prevalence20. Prevalence data for this study were also obtained from the ISMH at individual level in the form of a list of patients diagnosed with cancer, with the date of birth, disease code, date of diagnosis, and date of death when applicable. The 10-year-prevalence was calculated for the reference years 2017–2021. This meant that patients diagnosed within 10 years before one of these reference years and who were still alive in the reference year were considered prevalent cases and categorized by age group, sex, and cancer type. Cancer prevalence also included patients in terminal stages who died from the disease within the reference year. For these cases, it was assumed that death occurred in the middle of the year, thereby incorporating 6 months into the YLD estimations. The received data did not contain information about treatment and therefore did not allow for estimation of the frequencies of different severity grades in the diseased population. According to the GBD methodology, many cancers exhibit at least four categories of sequelae: diagnosis and primary therapy; controlled; metastatic; and terminal phases with specific variations for the controlled phase such as colostomy for colorectal cancer, mastectomy for breast cancer, infertility for cervical and prostate cancer; and others20. For this study, the prevalence of each cancer sequela in Kazakhstan was sourced from the GBD 2017 study, stratified by sex and age21. To check the sensitivity of GBD sequelae in the final results for some types of cancer (except cervical cancer and stomach cancer), we used age- and sex-specific severity distributions from the German Burden of Disease Study22,23. The respective distribution of sequelae was applied to the population with disease from national Kazakh data. YLD for each sequela were calculated using the following formula:

where i is the age group, x is the cancer sequela, PS is the 10-year prevalence of cancer sequela, and DWS is the disability weight (DW) for cancer sequela.

DWs for each health state were derived from the GBD 2013 study, which were calculated using various methods, including expert and general population surveys (Supplementary Table S1)24. The sum of YLD for all sequelae represents the final estimate of YLD associated with each type of cancer.

To conduct a comparative analysis of DALY rates for specific cancer types in Almaty, we examined analogous metrics from major cities in Germany and Scotland, as well as from Mexico and Indonesia. This analysis also encompassed comprehensive data for the entirety of Kazakhstan and the broader Central Asian region, to which Kazakhstan is integral. We decided to make a comparison between different major cities of the world. Our sample included Glasgow and Berlin, for which data are readily available in public national databases. We also randomly selected the cities of Mexico City and Jakarta, with similar SDIs to Kazakhstan (0.732 and 0.802, respectively) for which we extracted data from the GBD 2019 study results tool. Data for Berlin were also available from the German Burden of Disease study, for which we had data with age distribution. YLL data from the German Burden of Disease Study (BURDEN 2020) on Berlin, the largest German city, were recalculated for the present study using the GBD study life expectancy estimates.

Results

Morbidity and mortality

In 2021, the city of Almaty reported a total of 2018 newly diagnosed cases and 921 recorded deaths attributed to stomach, lung, colorectal, breast, prostate, and cervical cancers. The most prevalent cancers observed were prostate and colorectal cancers in men and breast and cervical cancers in women. The highest mortality rates were associated with lung and stomach cancer in men and breast and colorectal cancer in women (Table 1).

When comparing indicators in 2017 and 2021, a decrease in the crude and age-standardized rates of prevalence and mortality was observed for nearly all types of cancer. Exceptions were noted for stomach cancer in men, where both crude and standardized mortality rates showed an increase by 5.5% and 2.6%, respectively. Additionally, for colorectal cancer in men, an increase in crude 10-year prevalence rates (by 5.0%) was observed, accompanied by a decrease in standardized rates by − 2.0%. The most notable difference between 2017 and 2021 was found in women, revealing a substantial rise in both the crude and standardized 10-year prevalence rates for lung cancer, by 15.9% and 0.41%, respectively.

Absolute numbers and age-standardized rates for DALY

Absolute DALYs

Cancers of specified types accounted for a total of 25,016.70 DALYs in Almaty during 2021, with a distribution of 95.2% attributed to YLL and 4.7% to YLD. Among these, the most substantial burden was linked to lung and stomach cancers in men and to breast and colorectal cancers in women (Fig. 1). The total DALYs attributed to the selected cancer types in 2021 amounted to 14,270.90 DALYs in women and 10,745.80 DALYs in men.

Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) according to sex for each selected cancer type with proportions of years lived with disability (YLD) and years of life lost owing to premature death (YLL) in Almaty, 2021. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), delineated in this figure for Almaty in 2021, encompass both the years lived with disability (YLD, represented in orange) and the years of life lost to premature mortality (YLL, depicted in purple), with these metrics disaggregated by sex for selected cancer types.

Relative changes in DALYs between 2017 and 2021

The burden associated with the selected cancers rose from 22,105.70 DALYs in 2017 to 25,016.60 in 2021, representing a 13.2% relative increase (Table 2). Among the selected cancer types, the most noticeable rise in absolute DALYs was observed for stomach cancer in in men (+ 30.7%) and women (+ 40.2%). This observed rise was primarily attributable to population growth. In contrast, age-standardized DALYs for these cancer types declined in total from 2,015.80 to 1,609.80 per 100,000 individuals, a notable reduction of 16.0% primarily attributed to YLL.

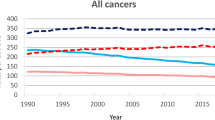

Over the course of 4 years, the age-standardized DALY rate per 100,000 increased only for stomach cancer in men; for all other cancer types, a decrease in the rate was noted in both men and women (Fig. 2). The most substantial reduction was found in prostate cancer among men, and lung and breast cancer among women. Notably, this decline was more closely associated with a decrease in YLL (− 36.0% for prostate cancer and − 40.6% for lung cancer in women) than in YLD (Supplementary Table S2).

Age-standardized disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) rates for certain types of cancer in men (left) and women (right) from 2017 to 2021 in Almaty. This figure shows trends in age-standardized disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) rates per 100.000 population among men and women in Almaty over the 5-year period, 2017 to 2021, for lung, stomach, colorectal, prostate, breast, and cervical cancers.

Ranking

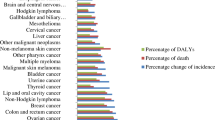

In 2017, the most substantial burdens affecting both sexes were for lung cancer, followed by breast, colorectal, stomach, cervical, and prostate cancer. In 2021, breast cancer was in the leading position, followed by lung, stomach, colorectal, cervical, and prostate cancer. Figure 3 presents a comparative ranking of selected cancers in Almaty by age-standardized DALY rates per 100,000 population, for both men and women, spanning from 2017 to 2021. The lung cancer rank decreased by one position whereas breast cancer ascended by a single position within the observed period. All other cancer types maintained their respective standings, with prostate cancer exhibiting the most pronounced reduction in DALY rates.

Ranking of selected cancers based on age-standardized disability-adjusted life year (DALY) rates in both sexes between 2017 and 2021. This figure shows comparative rankings of selected cancers based on age-standardized disability-adjusted life year (DALY) rates in Almaty for both sexes, compared with 2017 and 2021. Changes in ratings are indicated by color coding: red indicates an escalation in ranking, green signifies a decline, and yellow means no change. The accompanying percentages and brackets represent the relative change in age-standardized DALYs between two years for each cancer type.

The largest cancer burden among men exhibited no change in 2017 and 2021 and was primarily attributed to lung cancer, followed by stomach, colorectal, and prostate cancer.

The foremost contributors to DALYs among women remained consistent in both 2017 and 2021. These were breast cancer, followed by colorectal cancer and cervical cancer. In 2017, the fourth and fifth positions among the selected cancer types were for lung and stomach cancer, respectively. In 2021, there was a reversal in these rankings, with stomach cancer surpassing lung cancer among women in Almaty. The primary cancer burden among women in both 2017 and 2021 was owing to breast cancer, followed by colorectal, cervical, lung, and stomach cancers. Notably, in 2021, the absolute DALYs for stomach cancer exceeded those of lung cancer in women (Supplementary Figs. S1 and S2).

YLD and YLL proportions

The proportion of YLD in the total DALYs differed depending on the type of cancer, with minimal values observed for stomach cancer (2.4%) and lung cancer (3.3%) and maximum proportions noted for breast cancer (6.7%) and prostate cancer (8.4%) in 2021. In women, the proportion of total YLD (for all observed cancers) constituted 5.6% whereas in men, YLD for the selected types of cancer accounted for 3.4%, with the difference in the ratio of non-fatal to fatal consequences (YLD:YLL) being 1.4 times higher in women. In the case of neoplasms affecting both sexes, including lung, colorectal, and stomach cancers, the ratio of YLD:DALYs was also 1.4 times higher than in men. Between 2017 and 2021, a relative reduction in the YLL proportion was apparent for prostate cancer (− 2.9%), breast cancer (− 0.8%), lung cancer (− 0.7%), and colorectal cancer (− 0.3%). Conversely, there was a slight relative increase in the YLL proportion for cervical and stomach cancer (+ 0.2% and + 0.2%, respectively) (Fig. 4).

Contribution to disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) of years lived with disability (YLD) and years of life lost owing to premature death (YLL) by cancer type and sex in 2017 and 2021, Almaty. This figure shows the proportional contribution of years lived with disability (YLD, shown in orange) and years of life lost due to premature death (YLL, shown in purple) to total disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for each specific case by cancer type and sex in Almaty for lung, breast, colorectal, stomach, cervical and prostate cancer, reflecting temporal changes in disease burden over the period 2017–2021.

Age distribution of DALY by cancer type

DALYs per 100,000 people for the selected cancer types in both sexes remained relatively low until age 35 years, beyond which a gradual increase was observed (Fig. 4). Among men, the highest rates were identified in the age group 65–74 years for lung and stomach cancer and 75–84 years for colorectal cancer and prostate cancer. For women, the age ranges at which the highest DALY rates per 100,000 were observed were for breast cancer, with a first peak occurring at age 45–54 years and a second peak at age 65–74 years.

Cervical cancer displayed a peak in the DALY rates in the age group 45–54 years, with a slight decline observed in the age group 65–74 years. Both stomach and lung cancer demonstrated their highest DALY rates in the age group 65–74 years. However, colorectal cancer rates began to ascend notably from the age group 55–64 years, reaching their peak in the age group 75–84 years (see Fig. 5).

Sensitivity analysis: YLD for Almaty based on German severity distribution

Owing to the absence of Kazakh data on the frequency of sequelae, two sources were used for the DALY calculations, estimations from the GBD study for Kazakhstan and data from the German Burden of Disease study22,25. In the German study, data were available for breast, colorectal, lung, and prostate cancers. Upon applying the German severity distribution to the 2021 Almaty data, breast cancer resulted in 647.0 YLD, marking a 37% increase compared with the 407.9 YLD calculated using Kazakhstan's severity distribution from the GBD study. A comparable trend was evident in the cases of prostate cancer (+ 25.8%), colorectal cancer in men (+ 18.3%), and colorectal cancer in women (+ 14.2%). Conversely, when applying the German severity distribution data to calculate the YLD for lung cancer in men, the figures were lower than those calculated using the GBD study's severity distribution data, with a difference of − 21.1%; for lung cancer in women, a difference of − 4.2% was observed. In the distribution of different stages of breast cancer within the German and GBD studies, a disparity was observed in the controlled phase, with and without mastectomy. Within the German data, the proportion of these two stages was relatively balanced within the disease structure, accounting for 47% and 39%, respectively. The GBD data for Kazakhstan depicted the controlled phase without mastectomy as predominating over all other stages, constituting 81%, whereas the phase with mastectomy comprised 12%. In the computation of DALYs, the relative discrepancy in total DALYs between the GBD and German severity distribution varied from − 0.5% to + 3.8%, given that the predominant component of the DALY metric is YLL. For more detailed results, refer to Supplementary Table S2.

Comparative analysis of DALYs in Almaty and other metropolitan areas

We compared DALY rates per 100,000 population in Almaty with similar indicators from studies conducted in major cities of Germany and Scotland, as well as using open data from the GBD study for all of Kazakhstan, Mexico City and Jakarta, as well as Central Asian regions, which include Kazakhstan25,26,27. Overall, the DALY rates based on national data for Almaty were similar to the GBD rates for Jakarta and Mexico City whereas the rates for Glasgow and Berlin derived from national studies tended to be much higher. Almaty generally showed lower DALY rates for colorectal and prostate cancers in men and breast and lung cancers in women, as compared with other locations. Exceptions to the observed trends were discernible in the age-standardized DALY rates for stomach cancer in Almaty, which surpassed those in Glasgow and Jakarta for both sexes and exceeded those for men in Mexico City. Moreover, for the male population of Almaty, DALY rates for lung cancer were elevated in comparison with their counterparts in Mexico City; concurrently, women in Almaty exhibited higher DALY rates for cervical cancer relative to those in Jakarta. Upon comparing DALY rates for Almaty derived from our research with data for Kazakhstan from the GBD study, Almaty presented lower DALY rates for all cancer types across both sexes.

When comparing DALY rates for Almaty in our study and those for all of Kazakhstan from the GBD study, lower rates were observed in Almaty for all cancer types in both sexes. A more detailed presentation of age-standardized DALY rates per 100,000 for the specified regions is provided in Table 3.

To explore age differences between cities, using Berlin and Almaty as examples, the DALY rates attributed to lung, breast, colorectal, and prostate cancers among both men and women were compared for 2020. The burden of these cancer types in Berlin exceeded that of Almaty, particularly in the older age groups. DALY rates for colorectal and prostate cancer in men aged 85+ years were lower in Almaty compared with those in Berlin, by 20 and six times, respectively, with a similar trend in women for colorectal cancer (by four times) and breast cancer (by 10 times). In younger age groups, the differences were minimal or absent in these cities (Supplementary Fig. S2).

Discussion

In this study, we examined the burden of breast, lung, stomach, colorectal, cervical, and prostate cancers in Almaty, Kazakhstan from 2017 to 2021. In 2021, the total burden for selected cancers in Almaty was 25,023.60 DALYs, primarily attributed to death rather than disability. The largest burden was seen in men for lung and stomach cancer; in women, breast and colorectal cancer had the largest burden. Non-fatal burden (YLD) proportion in DALY increased for almost all selected cancer types, except stomach and cervical cancer over the observed period in Almaty. The non-fatal to fatal burden ratio for all selected cancer types was higher in women than in men, meaning that the proportion of total YLD in the total DALYs was 1.6 times higher for women. Men's cancer burden peaked at ages 65–84 years whereas women had two peaks at ages 45–54 years (breast and cervical cancers) and 65–84 years (breast, colorectal, stomach, and lung cancers).

Between 2017 and 2021 in Almaty, the age-standardized prevalence and mortality rates showed a decrease for most cancer types in both men and women. The only exceptions were a 2.6% increase in stomach cancer mortality in men and a slight increase in lung cancer prevalence in women (0.41%). Age-standardized DALY rates exhibited a decline for nearly all cancers in both sexes, averaging 20%, with the exception of stomach cancer in men. The increase in lung cancer prevalence in women is contributing to a rise in YLDs, which accounted for only 5% of DALYs in 2021. Along with a substantial decrease in age-standardized mortality and YLLs, this is leading to a decrease in age-standardized DALY rates. Notably, previous studies reported a decrease in stomach cancer mortality in Almaty from 2009 to 2018. In our study, we noted a gradual decrease from 2017 to 2020, followed by an increase in mortality from 2020 to 202128. This could potentially be related to the COVID-19 pandemic, which may have impacted access to health care, although rates for other cancers did not show an increase. In 2021, Almaty's stomach cancer incidence rates, although slightly higher, were comparable to the global average (ASIR globally in 2020 is 15.8 per 100,000 for men and 7.0 per 100,000 for women). However, stomach cancer mortality rates for men in Almaty exceeded the global average (14.8 in Almaty vs. 11.0 per 100,000 worldwide). Notably, the highest incidence and mortality rates are in East Asian countries, where the mortality rate for men reaches 21.1 per 100,000 and 8.8 per 100,000 for women29. Stomach cancer remains a significant global health concern, ranking fifth in incidence and fourth in mortality worldwide. In Kazakhstan, it ranks second in both morbidity and mortality among men, and fifth and fourth, respectively, among women. The incidence rate is 13.7 per 100,000, and the mortality rate is 9.3 per 100,000 for both sexes, which are higher than the global averages of 9.2 and 6.1, respectively3. Given these disparities, it is imperative to implement initiatives to control stomach cancer in Almaty and Kazakhstan in general, including primary prevention through the eradication of Helicobacter pylori, especially in people with chronic gastritis or a family history of stomach cancer, as well as the reduction of other risk factors such as excessive salt intake, smoking, obesity, and alcohol consumption30. Early detection through the introduction of endoscopic screening is of great importance because it has the potential to reduce mortality by up to 40% in Asian populations31. Further research is necessary to investigate the specific risk factors for stomach cancer in Kazakhstan. An increase in lung cancer prevalence in women aligns with the global trend linked to the rise in smoking among women since the 1960s. In Kazakhstan, tobacco consumption in women increased from 4.5% to 10.1% between 2014 and 2021. This rise may be due to the growing popularity of vaping devices, often perceived as safer than traditional tobacco products32. The 2021 assessment of DALYs in Almaty showed that breast and lung cancer accounted for the largest burden in both sexes, followed by stomach and colorectal cancer. These data on the cancer burden in Almaty differ from global average trends, where lung cancer typically holds the top position, followed by colorectal and stomach cancer. Notably, the prevalence of these cancers is generally higher in countries with a higher SDI, except for cervical cancer, which is more prevalent in low-SDI countries11.

The DALY ranks of the selected cancer types in Almaty also differed from those in Kazakhstan as a whole, according to GBD data. In Kazakhstan, cervical cancer overtakes colorectal cancer among women whereas in Almaty colorectal cancer ranks second and cervical cancer ranks third21. Comparing the GDB study data obtained for Almaty with data for the whole of Kazakhstan, it can also be noted that the DALY rates for stomach cancer in Almaty did not show the decrease observed in Kazakhstan, which emphasizes that greater attention is needed to the prevention of stomach cancer. For breast cancer, colorectal cancer, and lung cancer in Kazakhstan, based on the GBD study, there is an increase in rank and a decrease in DALYs; in our study, with the same increase in rank, there was a sharper decrease in DALYs, highlighting better survival. In this regard, it is important to note that to assess and discuss the full picture, it is important to also evaluate national data. In Almaty during 2017–2021, men's rankings by absolute DALYs remained stable whereas among women, lung cancer dropped one position and stomach cancer rose one position. Whereas direct comparisons with global rankings are challenging owing to differences in time periods and the limited scope of cancer types in our study, it is informative to note that, globally from 1990 to 2016, the lung cancer DALY rank remained unchanged from the first position. Stomach cancer dropped from second to third place whereas colorectal and breast cancer showed no change; cervical cancer declined by two positions, and prostate cancer ascended one position20. The age-specific DALY rates per 100,000 population in Almaty for colorectal, breast, and prostate cancers in the age group 85 years and older were markedly lower compared with those observed in Berlin for the same age category. A similar pattern was observed in a study of DALYs associated with acute myocardial infarction in Kazakhstan in comparison with patients in Portugal, where the highest burden was also found in the older age group33. This difference between countries can be explained by variations in health care systems, the mode of detection, patient survival, and access to medical care. Also, sociodemographic and cultural factors, such as the age composition (proportion of the older population) in the two cities had a role, and the care system and social support for older people differ34. Data collection and quality may also contribute to the observed differences.

The proportions of YLD and YLL in DALYs in Almaty exhibited similarities to global averages from the GBD study for breast and stomach cancers. The proportion of YLL in Almaty was slightly higher than the proportion of YLL globally for prostate cancer (92% share of YLL in Almaty vs. 91% globally) and colorectal cancer (96% in Almaty vs. 95% globally); this was lower for cervical cancer (93% in Almaty vs. 96% globally) and lung cancer (97% in Almaty vs. 99% globally)8. For cancers such as cervical, breast and colorectal cancer, early diagnosis and therapy have a significant impact on disease outcome, potentially increasing YLD at the expense of YLL owing to improved and longer patient survival. Kazakhstan has implemented national screening programs for cervical and breast cancers since 2008 and for colorectal cancer since 2011, potentially explaining the higher YLD rates associated with cervical cancer compared to the global average. In our study, the proportion of the non-fatal burden (YLD) within the total DALY increased for nearly all selected cancer types in Almaty during the observed period, with the exception of stomach and cervical cancers.

The effectiveness of cancer screening programs has been assessed in several studies. From 2009 to 2018, the incidence of breast cancer in Kazakhstan rose from 39.5 per 100,000 to 49.6 ± 0.70 per 100,000 in 2018. However, the proportion of locally advanced and advanced cancer stages decreased, with stage III cases dropping from 22.2 to 8.6% and stage IV cases from 6.4 to 3.6%35. Population mammography screening was carried out for women from 50 to 69 years of age, and in 2018 extended for women from 40 to 70 years of age. Up to 30% of breast cancer cases are detected through screening, with 90–95% of these being in the early stages. Breast cancer mortality rates have declined from 16.5 per 100,000 in 2009 to 13.6 per 100,000 in 2020. Although more time is needed to fully assess the effectiveness of screening programs, the data described over the past decade suggest that the observed increase in breast cancer incidence, along with the decrease in mortality and advanced-stage cases can tentatively be attributed to the impact of ongoing screening efforts and increased screening coverage36. New cases of cervical cancer are more prevalent in developing countries, where early diagnosis and prevention programs are limited. In Kazakhstan, cervical cancer is also a significant public health issue, with incidence rates considerably higher than those in developed countries. Population-based cytological screening was only introduced in 2008. Initially, cervical cancer screening was conducted using the conventional Pap test every 5 years for women aged 30–60. In 2017, the screening interval was shortened to 4 years, and the target age range was extended to include women up to 70 years old. Between 2008 and 2016, cervical cancer screening coverage decreased from 75.6 to 46.2% in 2012. However, after implementing an active invitation strategy in 2019, coverage increased to 83.2%. This change was accompanied by a rise in the detection of high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL) from 0.06 to 0.43% among women undergoing cervical cancer screening. Since 2008, the incidence of cervical cancer has increased from 17.1 to 18.7 per 100,000 women, although there is a downward trend in mortality, which has decreased from 7.7 to 6.2 per 100,000 women over 12 years37. Despite improvements in screening coverage and the detection of precancerous lesions, cervical cancer morbidity and mortality rates remain relatively high. It is important to note that primary prevention through human papillomavirus vaccination for cervical cancer has not been introduced in Kazakhstan. Previously, in 2014, HPV vaccination was launched as a pilot project in four sub-national regions. However, the program was halted in 2017 due to extensive media coverage about the potential or perceived side effects of the vaccine, leading to widespread parental refusal38. A national vaccination program is planned for the third quarter of 2024. In Kazakhstan, colorectal screening is conducted using immune analysis of fecal occult blood for individuals aged 50–70 and total colonoscopy if fecal test results are positive, with a screening interval of 2 years. Coverage of the target population varied from 78.4% in 2012 to 53.1% in 2020. Screening efforts increased the incidence of colorectal cancer from 15.5 in 2011 to 16.5 per 100,000 in 2020, while reducing mortality from 9.3 to 8.0 per 100,000 over the same period39. Between 2004 and 2018, the incidence rates for stages I and II colorectal cancer doubled from 35 to 67.4%, while stage IV cases decreased from 19.3 to 13.1%, and stage III cases from 45.7 to 19.5%39.

Previously, Kazakhstan conducted screening programs for prostate, stomach, and liver cancer from 2013 to 2018. However, prostate cancer screening was discontinued owing to limited effectiveness and global debate about its contribution to mortality. Consequently, the introduction of prostate cancer screening led to increased morbidity rates without a corresponding decrease in mortality. Nevertheless, the 5-year survival rate gradually improved from 55.7% in 2013 to 62.2% in 201940. Currently, screening for prostate cancer is only available for rural residents aged 55–75 years41. Since 2013, stomach cancer screening in the form of gastroscopy was gradually introduced in Kazakhstan, which was discontinued in 2018. In some regional studies, the results of the screening program showed a low detection rate of stomach and esophageal cancer during gastroscopy and amounted to only 8.7% of all identified primary cancer cases42. However, other studies showed that from 2009 to 2018, the detection of early stages of cancer (I and II) increased from 24.5 to 41.3%43. From 2013 to 2018, liver cancer screening in Kazakhstan was conducted by measuring alpha-fetoprotein levels in blood serum and performing liver ultrasound examinations among patients with liver cirrhosis of both sexes. The annual age-standardized incidence rate was 5.7 ± 0.1 (mean ± SE) per 100,000 for 2005–201944. An analysis of this program's effectiveness in one region revealed low detection rates and low cost-effectiveness45. These findings may be attributed to the complexities of liver cancer screening, such as identifying appropriate risk groups, accurately diagnosing liver cirrhosis, ensuring test accuracy, and managing patients with abnormal screening results.

Our study found an increasing burden of stomach cancer and a high prevalence of cervical cancer in Almaty, while globally efforts have reduced the burden of these cancers through improved screening and prevention strategies. Cervical cancer remains one of the most common cancers among women in Almaty, highlighting the need to strengthen HPV screening and vaccination programs.

As a comprehensive measure of health that covers the burden of both fatal and non-fatal outcomes of cancers, the DALY estimates in this study can be used as a complementary and comprehensive tool for assessing population health to inform health policies and interventions. Such comprehensive assessments are scarce in Almaty as well as in the wider context of Kazakhstan and the Central Asian region. Given Kazakhstan's ongoing epidemiologic transition, the development of cancer control strategies will become increasingly important. This study used direct calculations based on cancer registry data. The DALY calculation method used in this study has the potential to be adopted for routine annual assessment of health status, interventions, and implementation of new prevention and treatment measures in the future among patients with cancer. In general, the use of national data sources opens up the possibility of basing burden of disease calculations less on modeling than in the GBD study and more on real-world data. The results can thus be better interpreted and the data quality assessed against the background of existing health care provision and systems of data collection. This also offers the possibility of sub-national analyses based on real variance in the available data; thus, the analysis could be extended to other disease groups.

Despite the strengths of this study, there are some limitations. The data collection period coincided with the COVID-19 pandemic in Kazakhstan, leading to a decline in cancer detection (from 194.7 in 2019 to 172.1 in 2020 and 191.3 per 100,000 people in 2021) and constraints on accessing treatment. This may have resulted in underestimation of the cancer burden in 2020 and 2021, necessitating further research to evaluate the pandemic's long-term impact on the national cancer burden13. The YLL calculation was based on life expectancy from the GBD study, which is much higher than that in Kazakhstan. Therefore, the final YLL and consequently the DALYs, as well as the share of YLL versus YLD, may be overestimated. The database of cancer cases we used did not contain information about treatment, and therefore, the sequelae of the disease. Instead, we used sequelae prevalence from the GBD database and the German Burden of Disease study. Sensitivity analysis showed a considerable impact of different severity distributions on the YLD calculations; however, this had hardly any effect on the DALYs owing to predominance of the YLL in assessing the burden of disease for cancer. Notwithstanding, the real distribution of severity in Kazakhstan and Almaty is unclear. Although the GBD study relies on modeling and not on national data, it is unclear to what extent the German distributions are transferable. Epidemiological and clinical data, which refer to the severity of disease, are therefore of particular importance for burden of disease calculations at national level. In future studies, it would be beneficial to have reliable Kazakh data available on the prevalence of cancer sequelae to provide more accurate results. In this study, we used a method to calculate YLD based on 10-year prevalence data; however, the results may differ if incidence data were applied. Although various sources have compared these two approaches and found no significant differences, future research would benefit from comparing these methods in the context of Kazakhstan46. In this study, we identified data limitations that precluded the use of a longer follow-up period to assess disease trends.

Conclusion

This was the first study to assess the burden of the five most common types of cancer in the city of Almaty, Kazakhstan from 2017 to 2021. DALYs owing to these types of cancer are steadily increasing; however, morbidity and mortality rates per 100,000 tend to decrease, which indicates the effectiveness of preventive measures and management in patients with cancer. Future studies should focus on improving evaluation of the cancer burden and advancing estimation techniques in Almaty and across Kazakhstan. Critical strategies for cancer control must encompass the initiation of primary preventive measures against cervical cancer, including human papillomavirus vaccination, and the implementation of stomach cancer screening. Enhancing current prevention programs and treatment approaches, along with raising awareness about cancer and its risk factors among the Kazakhstani population, are also crucial steps.

Data availability

The data sets created and/or examined in this study are not publicly available due to restrictions imposed by the Republican Center for Electronic Health under the Ministry of Health of the Republic of Kazakhstan. The data can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Bryant, J. H., Harrison, P. F. & Health, I. of M. (US) B. on I. World Development Report 1993: Investing in Health (1996).

World Health Organization (WHO). Global Health Estimates 2020: Deaths by Cause, Age, Sex, by Country and by Region, 2000–2019. https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/mortality-and-global-health-estimates/ghe-leading-causes-of-death

Sung, H., Ferlay, J. & Siegel, R. L. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer. J. Clin. 71, 209–249 (2021).

Bray, F. et al. The ever-increasing importance of cancer as a leading cause of premature death worldwide. Cancer 127, 3029–3030 (2021).

World Health Organization. International Agency for Research on Cancer. Cancer Today. https://gco.iarc.fr/today/online-analysis-map

Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 (GBD 2019) Socio-Demographic Index (SDI) 1950–2019 | GHDx. https://ghdx.healthdata.org/record/ihme-data/gbd-2019-socio-demographic-index-sdi-1950-2019

Interactive dashboards - Agency for Strategic planning and reforms of the Republic of Kazakhstan Bureau of National statistics. https://stat.gov.kz/en/instuments/dashboards/28507/

Global Burden of Disease Study 2021 (GBD 2021) Fertility Estimates 1950–2021 and Forecasts 2022–2100 | GHDx. https://ghdx.healthdata.org/record/ihme-data/global-burden-disease-study-2021-gbd-2021-fertility-1950-2100

Ebrahimi, H. et al. Global, regional, and national burden of respiratory tract cancers and associated risk factors from 1990 to 2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Respir. Med. 9, 1030–1049 (2021).

Yan, X. X. et al. Estimating disability-adjusted life years for breast cancer and the impact of screening in female populations in China, 2015–2030: An exploratory prevalence-based analysis applying local weights. Popul. Health Metr. 20, 1–11 (2022).

Fitzmaurice, C. et al. Global, regional, and national cancer incidence, mortality, years of life lost, years lived with disability, and disability-adjusted life-years for 32 cancer groups, 1990 to 2015: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study. JAMA Oncol. 3, 524 (2017).

World Health Organization (WHO). Global health estimates: Leading causes of DALYs. https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/mortality-and-global-health-estimates/global-health-estimates-leading-causes-of-dalys (2024).

The Ministry of Health of the Republic of Kazakhstan. Indicators of the oncology service of the Republic of Kazakhstan, 2021. 2022 [cited 2023 Jul 18]; Available from: https://onco.kz/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/pokazateli_2021.pdf

Murray, C. et al. (eds) The global burden of disease. A comprehensive assessment of mortality and disability from diseases, injuries, and risk factors in 1990 and projected to 2020 8–10 (World Health Organization, 1996).

Murray, C. J. L. & Lopez, A. D. Progress and directions in refining the global burden of disease approach: A response to Williams. Health Econ. 9, 69–82 (2000).

Demographic Statistics of the Republic of Kazakhstan. https://stat.gov.kz/official/industry/61/statistic/6

Abbafati, C. et al. Global age-sex-specific fertility, mortality, healthy life expectancy (HALE), and population estimates in 204 countries and territories, 1950–2019: A comprehensive demographic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 396, 1160–1203 (2020).

Roth, G. A. et al. Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 392, 1736–1788 (2018).

Mathers, C. et al. Global Health Estimates Technical Paper. http://www.who.int/gho/mortality_burden_disease/en/index.html (2000).

Fitzmaurice, C. et al. Global, regional, and national cancer incidence, mortality, years of life lost, years lived with disability, and disability-adjusted life-years for 29 cancer groups, 1990 to 2017: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study. JAMA Oncol. 5, 1749–1768 (2019).

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, Global Health Data Exchange. GBD Results. https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/

Rommel, A. et al. BURDEN 2020-Burden of disease in Germany at the national and regional level. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz [Internet] 61, 1159–1166. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30083946/

Porst, M. et al. The burden of disease in Germany at the national and regional level: Results in terms of disability-adjusted life years (DALY) from the BURDEN 2020 Study. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 119, 785 (2022).

Vos, T. et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 386, 743–800 (2015).

Burden 2020—RKI [Internet]. [cited 2023 Dec 18]. Available from: https://www.daly.rki.de/

Scottish Burden of Disease. https://scotland.shinyapps.io/phs-local-trends-scottish-burden-diseases/

Dicker, D. et al. Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality and life expectancy, 1950–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet (London, England) 392, 1684–1735 (2018).

Igissinov, N. et al. Trend in gastric cancer mortality in Kazakhstan. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 23, 3779 (2022).

Morgan, E. et al. The current and future incidence and mortality of gastric cancer in 185 countries, 2020–40: A population-based modelling study. eClinicalMedicine 47, 101404 (2022).

Iwu, C. D. & Iwu-Jaja, C. J. Gastric cancer epidemiology: Current trend and future direction. Hygiene 3, 256–268 (2023).

Zhang, X. et al. Endoscopic screening in Asian countries is associated with reduced gastric cancer mortality: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Gastroenterology 155, 347-354.e9 (2018).

Glushkova, N. et al. Prevalence of smoking various tobacco types in the Kazakhstani adult population in 2021: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 20, 1509 (2023).

Zhakhina, G. et al. Incidence, mortality and disability-adjusted life years of acute myocardial infarction in Kazakhstan: Data from unified national electronic healthcare system 2014–2019. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 10, 1127320 (2023).

Li, H. Y. et al. Global, regional and national burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease over a 30-year period: Estimates from the 1990 to 2019 Global Burden of Disease Study. Respirology 28, 29–36 (2023).

Igissinov, N. S., Toguzbayeva, A. Y., Igissinova, G. S. & Bilyalova, Z. A. Evaluation changes in indicators of oncological service in breast cancer in Kazakhstan. Medicine 1–2, 16–20 (2020).

Shatkovskaya, O., Kaidarova, D., Dushimova, Z., Sagi, M. & Abdrakhmanov, R. Trends in incidence, molecular diagnostics, and treatment of patients with breast cancer in Kazakhstan, 2014–2019. Oncol. Radiol. Kazakhstana 62, 16–23 (2022).

Kaidarova, D., Zhylkaidarova, A., Dushimova, Z. & Bolatbekova, R. Screening for cervical cancer in Kazakhstan. J. Glob. Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1200/jgo.18.65600 (2018).

Kaidarova, D. et al. Implementation of HPV vaccination pilot project in Kazakhstan: Successes and challenges. J. Clin. Oncol. 37, e13056 (2019).

Kaidarova, D., Jumanov, A., Zhylkaidarova, A. & Shayakhmetova, D. Colorectal cancer screening results in the regions of Kazakhstan with different levels of cancer prevalence. J. Clin. Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2022.40.4_suppl.062 (2022).

Umurzakov, K. T. et al. Epidemiological characteristics of male reproductive cancers in the Republic of Kazakhstan: Ten-year trends. Iran J. Public Health 51, 1807 (2022).

Civil Code of the Republic of Kazakhstan, https://adilet.zan.kz/rus/docs/K940001000_

Smailova, D. S. et al. Data analysis of a pilot screening program for the early detection of esophageal and gastric cancers: Retrospective study. Vestn. Ross. Akad. Meditsinskikh Nauk 74, 405–412 (2019).

Taszhanov, R. et al. Evaluation changes in indicators of oncological service in gastric cancer in Kazakhstan. J. Med. https://doi.org/10.31082/1728-452X-2020-211-212-1-2-16-20 (2020).

Igissin, N. et al. Liver cancer incidence in Kazakhstan: Fifteen-year retrospective study. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 25, 1763–1775 (2024).

Mussina, D. S., Bekbolatova, M. A. & Kazizova, G. S. Estimation of efficiency of the national screening program on early detection of liver cancer in pavlodar region. https://doi.org/10.31082/1728-452X-2018-191-5-7-11 (2018).

Gorasso, V. et al. The non-fatal burden of cancer in Belgium, 2004–2019: A nationwide registry-based study. BMC Cancer 22, 58 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to the staff of the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation and their collaborators for making data publicly accessible. We thank Analisa Avila, MPH, ELS, of Edanz (http://www.edanz.com/ac) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Funding

The analyses were funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research as part of the project “Capacities and infrastructures for health policy development—strengthening information systems for summary measures of population health” (funding reference: 01DK21017).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.K., A.R., K.K-S., D.K., N.G. designed the study. F.K., A.R., A.W., K.K-S., O.Sh, N.G. analyzed the data and performed the calculations and analyses. F.K., A.R., A.W., K.K-S., G.D., I.Zh., N.G. drafted the initial manuscript. All authors reviewed the drafted manuscript for critical content. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Since the study had retrospective nature the need of informed consent was waived by Ethics Committee of the Kazakhstan Medical University Higher School of Public Health (No: 138 of 31.05.2021). All methods were carried out in compliance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kassymbekova, F., Glushkova, N., Dunenova, G. et al. Burden of major cancer types in Almaty, Kazakhstan. Sci Rep 14, 20536 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71449-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71449-5

- Springer Nature Limited