Abstract

Most evidence and experience with mammography screening originate from Western countries, and the optimal prevention strategy for Taiwanese women remains uncertain. Currently, breast cancer susceptibility in Taiwan is primarily stratified by family history, which contrasts with the trend toward personalized screening. Additionally, the high false-positive and false-negative rates (and the resulting compromised positive predictive value) have hindered the widespread adoption of mammography among the general population. Consequently, there is an unmet need to identify breast cancer risk factors to develop a more efficient and tailored screening strategy that minimizes potential harm. This study aimed to identify breast cancer risk factors by analyzing big data, including National Health Insurance claims data, a screening database, a cancer registry from the Health Promotion Administration, and a death registry from census data. Between 2007 and 2017, 189,465 entries were extracted from the cancer registry, representing 133,546 breast cancer cases. The screening database contained 3,806,128 mammography episodes from 2004 to 2014. We identified subjects who had attended at least one screening session between January 2007 and September 2014, matching cancer cases to the registry. Screening intervals were extended by two years to August 2016. After excluding patients with pre-existing breast malignancies, 3,605,758 screening mammography episodes from 2,191,742 invitees were analyzed, resulting in the identification of 38,815 incident breast cancer cases. Multivariate analyses revealed that risk factors for breast cancer diagnosis included a family history of any cancer (odds ratio [OR]: 1.462), number of sisters with breast cancer (OR: 1.058), years of hormone replacement therapy (OR: 1.006), breast symptoms (OR: 3.843), breast examinations within two years (OR: 1.226), prior breast surgery (OR: 1.044), educational level (OR: 1.04), and breast density (OR: 1.096). Protective factors included menopausal status (OR: 0.935), breastfeeding (OR: 0.908), sonography within two years (OR: 0.899), comparison with prior mammography (OR: 0.775), number of mammography screenings (OR: 0.673), and screening via a mobile van (OR: 0.587). The model demonstrated an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) of 0.6766. Among 50,831 breast cancer cases, 47.6% had undergone at least one mammography screening before diagnosis, which was associated with earlier disease stages. Clinically detected breast cancer was an independent risk factor for recurrence-free and overall survival, as well as breast cancer mortality. Big data analysis identified several risk factors for breast cancer development in Taiwanese women and confirmed the efficacy of mammography screening.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common malignancy among women in Taiwan, with over 18,000 newly diagnosed cases annually, including both in situ and invasive cancers1. Mammography is the primary tool for early diagnosis, and the Health Promotion Administration (HPA) of the Taiwanese government currently offers biennial screening to women aged 45–69. For women with a family history of breast cancer, screening begins at age 40 and continues through age 69. Since 2010, the HPA has utilized tobacco health welfare funds to promote the screening of four cancers: cervical, breast, colorectal, and oral. Based on evidence from Western countries, mammography screening can reduce breast cancer mortality by 21–34%2,3,4,5. In Taiwan, the median age for breast cancer diagnosis is 50, and the 5-year survival rate for early-stage breast cancer is as high as 90%6. With early detection and multidisciplinary care, the cure rate is extremely high. Therefore, identifying breast cancer through screening to enable early diagnosis and treatment is crucial for preventive medicine.

Mammography screening plays a crucial role in detecting early, asymptomatic breast cancer. Many early-stage cancers detected through screening are still in situ (stage 0), and most invasive cancers detected are under 2 cm in size and without regional lymph node involvement. Despite its efficacy, most mammography screening results fall within Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) categories 1–3, which are considered relatively low risk7. For cases in BI-RADS category 3, a follow-up imaging test is typically recommended six months later. Those classified as screening-positive (BI-RADS categories 0, 4, and 5) require further confirmatory imaging or tissue biopsy. However, except for BI-RADS category 5, which carries a high likelihood of malignancy, the other categories require further confirmation, and not all lead to a cancer diagnosis. The high sensitivity of mammography contributes to this issue, but its accuracy is less consistent, resulting in a positive predictive value (PPV) of approximately 10%. This means that for every confirmed breast cancer case, approximately nine healthy women are incorrectly identified as suspicious, leading to false-positive results. The American College of Radiology (ACR) provides benchmarks for various performance metrics in mammography, including PPV1 (Positive Predictive Value of Recall). This is the percentage of women recalled for additional imaging (due to an abnormal screening mammogram) who are ultimately diagnosed with breast cancer. The ACR suggests a PPV1 benchmark range of 3–8%8. Additionally, there is a risk of false negatives, where cancer cases go undetected and present as interval cancers between screening rounds.

Mammography screening uptake in Taiwan remains low, with less than 50% of the targeted population participating (approximately 40%)9. The development of a more effective screening method and the reduction of potential harm are urgently needed. Most current evidence on mammography screening comes from Western countries, and the optimal prevention strategy for Taiwanese women remains largely unknown. Family history is currently the sole stratification factor for breast cancer risk, which is insufficient for personalized screening approaches. Thus, there is a critical need to identify risk factors for breast cancer to enable more efficient and individualized screening strategies.

Materials and methods

Overview

This study employed big data analysis to identify risk factors for breast cancer by integrating data from screening databases, cancer registries, and health insurance claims. By linking the cancer registry with the screening database, we determined whether invitees had undergone mammography during the asymptomatic period before their breast cancer diagnosis. A predictive model for breast cancer risk was then constructed. Furthermore, clinical characteristics and treatment outcomes between breast cancer cases with and without prior screening were compared to assess the efficacy of mammography screening in Taiwan.

Data sources

In 1997, the Ministry of Health and Welfare of Taiwan launched the National Health Informatics Project (NHIP) to enhance health information sharing while ensuring data privacy and reducing resource duplication. The Health and Welfare Data Science Center (HWDC) was established to generate data for improving decision-making, academic research, and public health in Taiwan.

For this study, data were sourced from the HWDC, which comprised the Breast Cancer Health Database. This database included newly diagnosed breast cancer cases between 2007 and 2017, linked to health insurance data (ambulatory care expenditures and orders, including HEALTH-83: BC_OPDTO and HEALTH-83: BC_OPDTE), the cancer registration long format (H_BHP_CRFLF), and cause-of-death statistics (H_OST_DEATH). Breast cancer cases were identified based on the following criteria: female sex, ICD-9 or ICD-10 codes starting with “174” or “C50” for primary cancer site, and exclusion of histology codes between 9590 and 9993 (hematological malignancies). All data were anonymized by removing personal identifiers and were reviewed and approved by the relevant authorities.

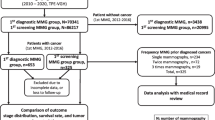

The coding manuals used included the “Taiwan Cancer Registry Coding Manual Long Form Revision 2018 v.3,” the “Cancer Site Specific Factor Coding Manual (Revised December 109),” and the “Breast Cancer Screening Database User Manual”10. Data from the female breast cancer-specific theme databases were collected for the study period. The cancer registration files (2007–2017) and screening mammography data (July 2004–September 2014: H_BHP_BCS) were incorporated, as outlined in Fig. 1.

Breast Cancer index cases

From 2007 to 2017, the cancer registry contained 189,465 entries, which were reduced to 133,546 individual breast cancer cases using the following algorithm: First, entries with only one cancer registry record were retained. For invitees with more than one record, records were separated by laterality, and the record with the latest follow-up was retained. If an invitee had bilateral breast cancers, the record with the latest follow-up for each side was retained. Duplicates were identified and removed using sorting keys, including encrypted ID, cancer site (ICD-O-3), and histology (ICD-O-3). The screening database included 3,806,128 mammography episodes between 2004 and 2014. Using unique IDs, we identified patients who had undergone at least one mammography screening between January 2007 and September 2014. The cancer registry was cross-referenced, with a two-year screening interval extension to August 2016 to align with Taiwan’s biennial screening standards. Figure 1 illustrates the data merging process.

Study cohorts

Two cohorts were established for the study:

Screening cohort: This cohort included all individuals from the screening database. Breast cancer cases identified in the cancer registry following screening were used as events (case = 1) in a logistic regression risk predictive model.

Cancer cohort: This cohort comprised all breast cancer index cases, categorized as either screening-detected or clinically detected, depending on whether screening data could be matched before the cancer diagnosis. The latest screening episode before diagnosis was retained. If the interval between screening and breast cancer diagnosis was ≤ 6 months, the case was considered screening-detected.

Risk factors for breast Cancer development

Explanatory variables derived from the screening database included age, family history of any cancer, family history of breast cancer (number of affected relatives, including mothers, sisters, daughters, grandmothers, and maternal aunts), menopausal status, number of births, age at first childbirth, breastfeeding history, history of oral contraceptive use and hormone replacement therapy, breast lumps, breast palpation and results, mammography within two years, ultrasound within two years, prior breast surgery, educational level, body mass index, type of mammography unit (fixed or mobile), mammographic density, and BI-RADS classifications11. Breast density on mammography was primarily determined through qualitative assessment (BI-RADS), where a radiologist visually assessed the mammogram and categorized breast density into one of four categories (fatty, scattered fibroglandular, heterogeneously dense, and extremely dense) based on the proportion of dense (fibroglandular) tissue to fatty tissue12,13. The screening interval was defined as the period between mammography and either breast cancer diagnosis or the censored date (August 2016).

Outcome variables

For the screening cohort, the outcome variable was breast cancer diagnosis following mammography screening. For the cancer cohort, outcomes were derived from the cancer registry and included age at diagnosis, interval from screening to diagnosis (screening interval), Taiwan Cancer Registry (TCR) case classification, histology, tumor size, regional lymph node status, tumor stage, last contact date, relapse date, vital status, and cause of death14. Site-specific factors included estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) status.

Statistical methods

Univariate logistic regression was conducted using breast cancer status (whether breast cancer was diagnosed after screening) as the dependent variable, regressed against all potential explanatory variables from the screening cohort. Significant variables were then included in a multivariate logistic regression model. Odds ratios (ORs), 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve were reported.

A Cox proportional hazards model was used to analyze the cancer cohort, with survival time (calculated in months) defined as the period from birth to the date of diagnosis or the censored date (August 2016), whichever occurred first. Survival outcomes were compared between screening-detected and clinically detected breast cancers, with hazard ratios (HRs) for recurrence-free and overall survival calculated using competing risk models. All statistical tests were two-sided with a significance level of α = 0.05, and analyses were conducted using SAS/STAT software (version 15.1; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Screening cohort

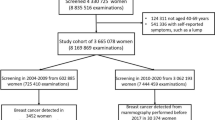

By merging the screening database with the cancer registry, we identified 3,605,758 screening mammography episodes from 2,191,742 invitees, resulting in the identification of 38,815 breast cancer cases. Among the invitees, the age distribution (in years) was as follows: median 53.3, mean 54.3, and standard deviation 6.8. Figure 2 shows a roughly bimodal distribution, consistent with the eligibility criteria for screening (ages 45–69) and the extension to age 40 for those with a family history of breast cancer.

For each invitee, their most recent screening mammography and associated explanatory variables from the screening database were used. Of the invitees, 38.9% (n = 853,543) were screened using a mobile mammography unit, and 61.1% (n = 1,338,199) were screened using a fixed mammography unit. Regarding image acquisition methods, 1.5% (n = 30,974) of mammograms were obtained via film, 26% (n = 565,833) via computed radiography, and 72.5% (n = 2,057,775) via digital radiography.

After excluding cases with pre-existing breast malignancies or those who underwent screening mammography after a breast cancer diagnosis (i.e., negative screening intervals), 2,182,957 invitees remained for further analysis.

Significant explanatory variables from the univariate analysis were selected for the multivariate breast cancer risk prediction model. The multivariate model included 2,182,953 invitees (four were excluded due to incomplete data). Of these, 38,533 breast cancer cases were identified in the cancer registry following screening mammography, resulting in a cancer detection rate of 1.77%. The mean age of those diagnosed with breast cancer was 56.7 years (standard deviation 7.2), which was significantly younger than the healthy invitees at their last screening (mean 59.6 years, standard deviation 7.4; p < 0.0001, two-sample t-test with unequal variances).

Multivariate analyses revealed the following risk factors for breast cancer diagnosis: family history of cancer (particularly the number of affected sisters), years of hormone replacement therapy, breast symptoms, breast examinations within two years, previous breast surgery, educational level, breast density, and age at mammography. Protective factors included menopausal status, number of pregnancies, breastfeeding, sonography within two years, prior mammography, the number of mammography screenings, and screening via a mobile mammography unit. The model’s area under the ROC curve (AUC) was 0.6766. Table 1 provides detailed predictive model information.

Other significant predictors from univariate analysis that did not remain significant in the multivariate model included benign breast disease (OR 1.521), personal history of breast cancer (OR 1.846), mother with breast cancer (OR 1.541), number of affected daughters (OR 1.117), number of affected aunts (OR 1.487), and body mass index (OR 1.015). Notably, grandmother with breast cancer (OR 1.195) and maternal grandmother with breast cancer (OR 1.065), which were risk factors in the univariate analysis, became protective factors when adjusted for other variables (Table 1).

Hazard ratios for the same set of risk factors were reported from the Cox proportional hazards model, with survival time in years defined from birth to a diagnosis of breast cancer or the predefined censored date (August 2016). Supplementary Table 1 details risk parameters, and these hazard ratios were concordant with the odds ratios from the logistic regression model.

Breast cancer cohort

To further explore the impact of screening on breast cancer outcomes, we compared survival between breast cancer patients with and without prior mammography screening. Of the 50,831 breast cancer cases (with 3,176 relapse events after excluding duplicated records, de novo stage IV disease, and missing values in follow-up) identified in the cancer registry, 47.6% (n = 24,207) had undergone at least one mammography screening before their cancer diagnosis. Among these, 62.4% (n = 15,103) had one screening session before diagnosis, 26.7% (n = 6,469) had two screenings, 8.6% (n = 2,076) had three screenings, 1.5% (n = 374) had four screenings, and five breast cancer cases had five mammography screenings before diagnosis. The median time from the last screening to cancer diagnosis was 0.25 years.

Supplementary Table 2 shows the distribution of pathological stages, ER, PR, HER2 status, and grade between screening-detected and clinically detected breast cancer cases. Screening-detected cases were more likely to be diagnosed at earlier stages (stages 0/I), with a higher frequency of ER and PR negativity, HER2 positivity, and grade I/II disease. Clinically detected breast cancer patients were significantly younger than screening-detected cases (mean age 52.1 vs. 56.2; p < 0.0001). Figure 3 illustrates the overall survival across the entire breast cancer cohort and subgroups based on detection mode (screening-detected vs. clinically detected). Supplementary Table 3 provides hazard ratios for overall and relapse-free survival.

Discussion

This study investigated the potential for implementing a personalized breast cancer screening strategy for Taiwanese women by identifying risk factors for breast cancer development through big data analysis. By integrating the screening database, cancer registry, and health insurance claims data, we assessed the real-world efficacy of mammography screening in Taiwan and evaluated the ability of repeated mammography to detect breast cancer earlier. For personalized screening to be realized, breast cancer risk factors must be identified and quantified in an unbiased manner.

Breast cancer remains the most common malignancy among women in Taiwan1. Thanks to advances in early detection and systemic therapy, outcomes have improved dramatically6. Although the age-standardized incidence of breast cancer in Taiwan is about half that of Western countries, it has been rising annually, with peak incidence occurring at a younger age (45–55 years) compared to Western women15,16. Younger women often present with more aggressive disease biology, leading to poorer prognoses and posing challenges for early diagnosis and treatment. The observation that breast cancer incidence might be leveling off in Taiwan compared to Western countries can be partially attributed to demographic differences and variations in screening practices. Taiwan has a smaller proportion of women over 70 compared to Western countries17. Since breast cancer risk increases with age, this demographic difference could contribute to a lower overall incidence in Taiwan. Higher screening coverage in Western countries, especially among older women, is likely to detect more cancers, including some that might be slow-growing or even non-lethal (overdiagnosis)18,19. Taiwan’s breast cancer screening program primarily targets women aged 45–69, potentially missing some cancers in older women18. Therefore, the combination of a younger population and less intensive screening in older age groups could explain, at least in part, the observed trends in breast cancer incidence in Taiwan compared to Western countries. However, other factors such as lifestyle, genetics, and environmental exposures may also play a role.

Currently, mammography is the cornerstone of breast cancer screening. However, screening strategies tailored to the unique characteristics of breast cancer in Taiwanese women have not yet been developed. Much of the evidence supporting mammography screening comes from studies conducted in Western populations, which may not be fully applicable to Taiwanese women. Additionally, using family history as the sole determinant for screening start age contrasts with the trend toward personalized healthcare20. The high false-positive rate of mammography further deters participation, contributing to the limited uptake of this screening method in Taiwan21. Therefore, it is critical to develop more effective screening methods while reducing the harms associated with false-positive and false-negative results22.

For breast cancer screening to be truly personalized, risk factors must be identified and their magnitude understood. Breast cancer is a complex disease influenced by various risk factors, and the presence of a single factor does not guarantee disease development. Understanding the interplay of these factors can help individuals and healthcare professionals identify those at higher risk23,24,25,26. Well-established risk factors for breast cancer include female sex, increasing age, family history, genetics, personal history of breast conditions or prior cancers, hormone exposure, reproductive history, dense breast tissue, and lifestyle factors. In this study, the breast cancer screening database provided comprehensive details on these risk factors, allowing us to link the cancer registry with the screening database to construct a breast cancer risk predictive model with an AUC of 0.6766. This moderate concordance statistic aligns with other models, such as the Gail, Tyrer-Cuzick (IBIS), and Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC) models, which have AUCs between 0.58 and 0.7027,28,29.

Breast symptoms were identified as the most significant predictor of breast cancer development (adjusted OR 3.843, HR 4.223). Mammography screening targets asymptomatic women, and those with breast symptoms should seek medical advice rather than rely solely on screening. However, the presence of breast symptoms during screening significantly increases the risk of subsequent breast cancer diagnosis. This finding highlights the importance of ensuring that symptomatic women receive appropriate diagnostic evaluation rather than using screening services intended for asymptomatic populations30.

Family history of any cancer (excluding pre-existing breast malignancies, which represented 6.2% of the study population) was the second most important predictor of breast cancer development (OR 1.462, HR 1.539). Most risk models incorporate family history of breast cancer, and in our study, both family history and the number of affected sisters (OR 1.058, HR 1.036) remained significant predictors in the multivariate analysis. However, the protective effects observed for grandmothers (both maternal and paternal) with breast cancer (OR 0.746 and 0.773, respectively) suggest potential interactions among family members specific to the Taiwanese population. Both maternal and paternal grandmothers were risk factors in the univariate analysis but became protective in the multivariate model. There might be some unmeasured confounders, such as underreporting of family history regarding grandmothers. Body mass index (BMI), another commonly studied risk factor, did not remain significant in our multivariate analysis despite its established link to postmenopausal breast cancer development31,32,33,34.

Other hormonal risk factors, including menopausal status, number of pregnancies, and breastfeeding, were protective against breast cancer development, while years of hormone replacement therapy (OR 1.006, HR 1.003) posed a small but significant risk. Although these factors were less impactful individually, they contribute to breast cancer risk. Educational level, a proxy for socioeconomic status and healthcare access, was positively associated with breast cancer risk, consistent with findings from recent meta-analyses35. Breast density, a radiological marker of cancer risk, was also identified as a significant predictor. Breast density refers to the proportion of dense tissue (composed of glandular and fibrous tissue) compared to fatty tissue in the breast as seen on mammograms26,36,37. Dense breast tissue can obscure tumors on mammograms and is associated with increased cell proliferation and hormonal activity, both of which elevate cancer risk26,36,37.

Some screening-related variables also influenced breast cancer risk. Women who had undergone breast examinations within two years had a 20% higher risk of breast cancer (OR 1.226, HR 1.107), likely reflecting heightened vigilance among individuals with ongoing breast concerns. Sonography within two years, however, was associated with a reduced risk of breast cancer in our study. Although not typically used for screening, sonography supplements mammography in cases of abnormal findings. Its widespread accessibility through Taiwan’s National Health Insurance makes it a valuable tool in breast cancer surveillance38.

Repeated mammography screenings and screening via mobile mammography units were also associated with reduced cancer risk. The latter finding suggests that mobile screening units, while convenient, may differ in terms of image quality and patient follow-up protocols compared to fixed facilities. Another plausible explanation is that women at increased risk or with symptoms are more likely to attend fixed mammography facilities. Further research is needed to evaluate the performance of mobile versus fixed mammography units to optimize screening outcomes39,40.

In the second part of the study, we compared breast cancer outcomes between patients with and without prior mammography screening. Screening-detected breast cancers were more likely to be diagnosed at earlier stages (0/I) and lower histological grades (I/II). Although screening detected more ER-/PR-negative and HER2-positive breast cancers, the immunohistochemistry (IHC) subtype discrepancy was minimal, and the significance might result from the large sample size. Clinically detected breast cancers occurred in younger patients (mean age 52.1 vs. 56.2; p < 0.0001) and were associated with poorer relapse-free and overall survival outcomes. Figure 3 illustrates the deterioration of survival outcomes as pathological stage advances across the entire cohort and within the screening-detected and clinically detected subgroups. Although Supplementary Table 3 confirmed worse survival for clinically detected cases, lead-time bias cannot be entirely excluded, as the main differences are observed primarily within the first two years (Fig. 3).

While traditional prognostic factors such as IHC subtype, nuclear grade, and stage played significant roles, the impact of mammography screening on breast cancer outcomes was substantial. Clinically detected cancers (without prior screening) were associated with a nearly twofold increased hazard of breast cancer-specific mortality (HR 1.968, 95% CI 1.746–2.219; p < 0.0001). Screening participants may have benefited from preventive health behaviors, resulting in heightened breast awareness and better general health, which may have contributed to improved outcomes41,42. Despite this, overdiagnosis is a real concern, even though screening mammography has demonstrated its effectiveness in reducing breast cancer mortality. While mammography remains an essential tool for early detection, it is important for women to be aware of the potential for overdiagnosis and discuss the benefits and risks with their healthcare providers to make informed decisions about screening.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, because the datasets were secondary, we lacked detailed clinical information beyond the cancer registry and screening database items, such as prescribed medications or laboratory/imaging results. Second, some women may have received diagnostic breast imaging services through the National Health Insurance (NHI) rather than the screening program, preventing a full assessment of the interplay between screening and diagnostic mammography. Third, follow-up diagnostic procedures for women with positive screening results are crucial for successful screening. Further studies are needed to evaluate the diagnostic performance of mammography screening in terms of sensitivity, specificity, and positive predictive value, as well as all relevant American College of Radiology (ACR) medical audit criteria43. Fourth, the predictive performance of breast cancer risk models may be limited without the inclusion of genetic information. Future research incorporating genetic markers, such as single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), could enhance personalized screening strategies44,45. Finally, the “Health-56: H_BHP_BCS” breast cancer screening file only included maternal, but not paternal, aunt family history.

Conclusion

This study successfully employed big data analysis to identify breast cancer risk factors among Taiwanese women and evaluated the efficacy of mammography screening. Future studies incorporating genetic data will likely further refine breast cancer risk prediction and enable more personalized screening strategies.

Data availability

Data for this study were obtained from the Health and Welfare Data Science Center, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Taiwan (URL:// https://dep.mohw.gov.tw/DOS/cp-5119-59201-113.html). All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

References

Cancer Registry Annual Report. Health Promotion Administration, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Taipei, Taiwan, December 2022. (2020) Taiwan.

Duffy, S. W. et al. Mammography screening reduces rates of advanced and fatal breast cancers: Results in 549,091 women. Cancer 126, 2971–2979 (2020).

Christiansen, S. R., Autier, P. & Støvring, H. Change in effectiveness of mammography screening with decreasing breast cancer mortality: A population-based study. Eur. J. Public. Health 32, 630–635 (2022).

Weedon-Fekjær, H., Romundstad, P. R. & Vatten, L. J. Modern mammography screening and breast cancer mortality: Population study. BMJ 348, g3701 (2014).

Møller, M. H., Lousdal, M. L., Kristiansen, I. S. & Støvring, H. Effect of organized mammography screening on breast cancer mortality: A population-based cohort study in Norway. Int. J. Cancer. 144(4), 697–706 (2019).

Health Promotion Administration 2022 Annual Report. Health Promotion Administration, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Taipei, Taiwan, November (2022).

Magny, S. J., Shikhman, R. & Keppke, A. L. Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System. [Updated 2022 Aug 29]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; (2023).

Rosenberg, R. D. et al. Performance benchmarks for screening mammography. Radiology 241(1), 55–66 (2006).

Chang, C. C. et al. The effects of prior mammography screening on the performance of breast Cancer detection in Taiwan. Healthc. (Basel) 10, 1037 (2022).

The Statistics Office of the Ministry of Health and Welfare. Taiwan. The Health and Welfare Database Manual. (2023). URL://dep.mohw.gov.tw/DOS/lp-2503-113-xCat-DOS_dc002.html. Accessed at May-23.

Spak, D. A., Plaxco, J. S., Santiago, L., Dryden, M. J. & Dogan, B. E. BI-RADS® fifth edition: A summary of changes. Diagn. Interv Imaging 98, 179–190 (2017).

Astley, S. M. et al. A comparison of five methods of measuring mammographic density: A case-control study. Breast Cancer Res. 20(1), 10 (2018).

Gweon, H. M., Youk, J. H., Kim, J. A. & Son, E. J. Radiologist assessment of breast density by BI-RADS categories versus fully automated volumetric assessment. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 201(3), 692–697 (2013).

Teichgraeber, D. C., Guirguis, M. S. & Whitman, G. J. Breast Cancer staging: Updates in the AJCC Cancer staging manual, 8th edition, and current challenges for radiologists, from the AJR special series on Cancer staging. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 217, 278–290 (2021).

Lin, C. H. et al. Molecular subtypes of breast cancer emerging in young women in Taiwan: evidence for more than just westernization as a reason for the disease in Asia. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 18, 1807–1814 (2009).

Lin, C. H. et al. Distinct clinicopathological features and prognosis of emerging young-female breast cancer in an East Asian country: A nationwide cancer registry-based study. Oncologist 19, 583–591 (2014).

Chen, Y. C. et al. Forecast of a future leveling of the incidence trends of female breast cancer in Taiwan: An age-period-cohort analysis. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 12481 (2022).

Yao, M. M. et al. Performance measures of 8,169,869 examinations in the National breast Cancer screening program in Taiwan, 2004–2020. BMC Med. 21(1), 497 (2023).

Yen, A. M. et al. Population-Based breast Cancer screening with Risk-Based and universal mammography screening compared with clinical breast examination: A propensity score analysis of 1 429 890 Taiwanese women. JAMA Oncol. 2(7), 915–921 (2016).

Su, S. Y. Nationwide mammographic screening and breast cancer mortality in Taiwan: An interrupted time-series analysis. Breast Cancer. 29, 336–342 (2022).

Han, H. J., Chu, Y. C., Tseng, L. M. & Huang, C. C. Mammography screening and the incidence of interval Cancer in Taiwan: A single institute’s experience. BMC Women’s Health (2023). (accepted).

Myers, E. R. et al. Benefits and harms of breast Cancer screening: A systematic review. JAMA 314, 1615–1634 (2015).

Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Type and timing of menopausal hormone therapy and breast cancer risk: Individual participant meta-analysis of the worldwide epidemiological evidence. Lancet 394, 1159–1168 (2019).

Kotsopoulos, J. et al. Age at menarche and the risk of breast cancer in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. Cancer Causes Control 16, 667–674 (2005).

Phipps, A. I. et al. Reproductive history and oral contraceptive use in relation to risk of triple-negative breast cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 103, 470–477 (2011).

McCormack, V. A. & dos Santos Silva, I. Breast density and parenchymal patterns as markers of breast cancer risk: A meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 15, 1159–1169 (2006).

Gail, M. H. et al. Projecting individualized probabilities of developing breast cancer for white females who are being examined annually. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 81, 1879–1886 (1989).

Tyrer, J., Duffy, S. W. & Cuzick, J. A breast cancer prediction model incorporating Familial and personal risk factors. Stat. Med. 23, 1111–1130 (2004).

Tice, J. A. et al. Using clinical factors and mammographic breast density to estimate breast cancer risk: Development and validation of a new predictive model. Ann. Intern. Med. 148, 337–347 (2008).

Larsen, M., Lilleborge, M., Vigeland, E. & Hofvind, S. Self-reported symptoms among participants in a population-based screening program. Breast 54, 56–61 (2020).

Renehan, A. G., Tyson, M., Egger, M., Heller, R. F. & Zwahlen, M. Body-mass index and incidence of cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. Lancet 371, 569–578 (2008).

World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Continuous Update Project Expert Report 2018. Diet, Nutrition, Physical Activity and Breast Cancer. (2023). URL://www.wcrf.org/dietandcancer/exposures/body-fatness. Accessed at May-30.

Begum, P., Richardson, C. E. & Carmichael, A. R. Obesity in post menopausal women with a family history of breast cancer: Prevalence and risk awareness. Int. Semin Surg. Oncol. 6, 1 (2009).

Gravena, A. A. F. et al. The obesity and the risk of breast Cancer among pre and postmenopausal women. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 19, 2429–2436 (2018).

Dong, J. Y. & Qin, L. Q. Education level and breast cancer incidence: A meta-analysis of cohort studies. Menopause 27, 113–118 (2020).

Boyd, N. F. et al. Mammographic density and the risk and detection of breast cancer. N Engl. J. Med. 356, 227–236 (2007).

Chiarelli, A. M. et al. Influence of patterns of hormone replacement therapy use and mammographic density on breast cancer detection. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 15, 1856–1862 (2006).

Wu, G. H. et al. Taiwan breast Cancer screening group. Evolution of breast cancer screening in countries with intermediate and increasing incidence of breast cancer. J. Med. Screen. 13(Suppl 1), S23–S27 (2006).

YabroffKR, O’Malley, A., Mangan, P. & Mandelblatt, J. Inreach and outreach interventions to improve mammography use. J. Am. Med. Womens Assoc. (1972). 56, 166–173 (2001). 188.

Chien, C. Y. et al. Image quality and performance benchmarks in vehicle and hospital mammography. Clin. Breast Cancer. 20, e358–e365 (2020).

Satoh, M. & Sato, N. Relationship of attitudes toward uncertainty and preventive health behaviors with breast cancer screening participation. BMC Womens Health. 21, 171 (2021).

O’Mahony, M. et al. Interventions for Raising breast cancer awareness in women. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2, CD011396 (2017).

Pan, H. B. et al. The outcome of a quality-controlled mammography screening program: Experience from a population-based study in Taiwan. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. 77, 531–534 (2014).

Sieh, W. et al. Identification of 31 loci for mammographic density phenotypes and their associations with breast cancer risk. Nat. Commun. 11, 5116 (2020).

Hung, C. C., Moi, S. H., Huang, H. I., Hsiao, T. H. & Huang, C. C. Polygenic risk score-based prediction of breast cancer risk in Taiwanese women with dense breast using a retrospective cohort study. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 6324 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors wound like to thank Taiwan Clinical Oncology Research Foundation, Melissa Lee Cancer Foundation and Dr. Morris Chang for their kind help during the study.

Funding

This work was supported in part by VGH-TPE (grant numbers: V110E-005-3, V111E-006-3, V112E-004-3, and V112C-013) and the National Science and Technology Council (grant number: NSTC 111-2314-B-075-063-MY3).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CCH initiated and conceived the study. TPL and YJW participated the study design. BFC, HTY and WPC conducted statistical analyses. LMT approved the submitted manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study protocol was reviewed and received approval from the Institutional Review Board of Taipei Veterans General Hospital (access number: 2021-03-007BC), where informed consent was waived as administrative data were used. All methods were performed in accordance with relevant ethical guidelines and regulations.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, CC., Lu, TP., Wang, YJ. et al. Identifying breast cancer risk factors and evaluating biennial mammography screening efficacy using big data analysis in Taiwan. Sci Rep 15, 16250 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00984-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00984-6

- Springer Nature Limited