Abstract

Traditional medicinal plants remain vital healthcare resources for rural communities, particularly in areas with limited access to modern medical services. This study documents and quantitatively analyzes the ethnobotanical use of medicinal plants in Meketewa District, northwestern Ethiopia. Ethnobotanical data were collected from 360 informants (20 key informants and 340 general informants) across five kebeles (Sub-Districts) representing different agroecological zones. Data were analyzed using preference ranking, direct matrix ranking (DMR), informant consensus factor (ICF), fidelity level (FL), Jaccard similarity index (JSI), Rahman’s similarity index (RSI), t-tests, and one-way ANOVA. The distribution of indigenous medicinal plant knowledge was significantly influenced by agroecology and socio-demographic factors, including age, gender, education, and knowledge experience. A total of 76 medicinal plant species belonging to 46 families were documented, with Fabaceae as the dominant family (7.9%) and herbs as the most common growth form (38.16%). Most species were used for human ailments (63.2%), while 9.2% were used for livestock and 27.6% for both. Natural forests were the primary source of medicinal plants (61.84%). Crushing was the dominant preparation method (38.4%), and oral administration was the most common route (47.7%). The use of additives, antidotes, and localized dosage systems reflects advanced therapeutic knowledge. Rhamnus prinoides was the most preferred species for treating human tonsillitis, whereas Euphorbia abyssinica was widely used for livestock swelling. High ICF values (up to 0.92) indicated strong informant agreement, while JSI (2.29–45.19%) and RSI (0.00–16.67%) reflected largely localized ethnomedicinal knowledge; similarly, high fidelity levels for Asparagus africanus var. puberulus (83.3%), Rhamnus prinoides (75%), and Cucumis ficifolius and Euphorbia abyssinica (73.3%) underscore strong cultural consensus and priority for phytochemical validation. Olea europaea subsp. cuspidata was the highest-ranked multipurpose species but faces increasing anthropogenic threats. These findings emphasize the need for in situ and ex situ conservation and further phytochemical and pharmacological validation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Traditional plant-based remedies serve as primary healthcare for approximately 70% of the global population, with even greater reliance in Africa due to cultural preferences and economic constraints1,2. The World Health Organization (WHO) recognizes this vital role and actively promotes integrating traditional medicine into modern healthcare systems, acknowledging its substantial contributions to disease management and population well-being3. This is crucial particularly in regions where conventional medical services remain inaccessible or unaffordable4. In Africa, traditional healing practices maintain profound socio-cultural significance in holistic health approaches that integrate physical, spiritual, psychological, and social well-being5. This accumulated wisdom, developed through centuries of careful observation and experimentation, has indeed significantly informed ethnobotanical wisdom for future drug discovery6. However, contemporary challenges of rapid socio-economic transformation, environmental degradation, globalization, and oral knowledge transmission now jeopardize the continuity of these ancient practices5, making documentation and preservation imperative.

Herbal medicines are vital in therapeutic applications, yet concerns about their safety, efficacy, and quality persist, primarily due to the lack of strong regulatory frameworks compared to modern pharmaceuticals7. In Africa, while there is a rich tradition of herbal medicine and public knowledge of its use, inadequate legal structures hinders the formal integration of these practices into healthcare systems. This gap is particularly evident in regions with rich biodiversity, such as Ethiopia, which has established a regulatory framework through Proclamation 1112 of 2019, to oversee traditional herbal medicines8. Nevertheless, the effectiveness of these regulations remains uncertain, as no comprehensive regional assessment of their implementation has been conducted to date.

Ethiopia has remarkable biodiversity and a long history of traditional healing, with 80% of the human and 90% of the livestock population depending on plant-based medicines, especially in rural areas with limited healthcare infrastructure9,10. The connection between this dependence and the regulatory framework is crucial; despite the widespread use of herbal medicines, numerous medicinal species and their associated traditional knowledge face escalating threats from overharvesting and deforestation10,11, leading to irreversible local extinctions. Meketewa District, in northwestern Ethiopia, is characterized by Dry Evergreen Afromontane Forest vegetation type and three distinct agroecological zones. These include the Kolla (lowlands, 500–1500 m.a.s.l, 75%), Woyna Dega (midlands, 1500–2500 m.a.s.l., 15%), and Dega (highlands, 2500–3200 m.a.s.l., 10%), each of which supports distinct plant communities and medicinal plant resources12. This diversity significantly enriches the local ethnobotanical landscape, yet without adequate regulatory oversight, the sustainability of these resources is at risk.

The convergence of limited healthcare infrastructure, scarce medical resources, economic constraints to modern treatments, and deep-rooted reliance on traditional healers in Meketewa District established an ideal setting for ethnobotanical research. This situation is compounded by the regulatory challenges discussed earlier, as the lack of comprehensive oversight may exacerbate the community’s reliance on traditional remedies. According to local health records (Meketewa District Health Office report, 2024), tuberculosis, typhoid, salmonellosis, malaria, diarrhea, and upper respiratory tract infections represented the most prevalent human ailments. Similarly, livestock health data (Meketewa District Agricultural Office report, 2024) identified pasteurellosis (both ovine and bovine), anthrax, and various parasitic infections as the dominant veterinary health problems. This dual burden of human and animal disease prevalence, coupled with constrained access to conventional medicine, underscored the community’s continued dependence on plant-based remedies and the urgent need to document this traditional healthcare system. In light of the threats to biodiversity and traditional knowledge mentioned earlier, there is need to document this traditional healthcare system. Therefore, this study aimed to (i) systematically document medicinal plants and associated indigenous knowledge; (ii) analyze ecological and socio-demographic factors influencing traditional medicinal knowledge; (iii) conduct a comparative analysis with existing Ethiopian studies to reveal novel findings and cross-cultural variations in medicinal plant use.

Methodology

Description of the study area

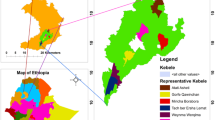

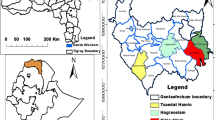

The study was conducted in Meketewa District, South Gondar Zone, Amhara National Regional State, Ethiopia, approximately 752 km northwestern of Addis Ababa. Geographically, it is located between 11°54’0”–12°12’0"N latitude and 38°8’0”–38°28’0"E longitude (Fig. 1). The District covered a total area of 62,356 hectares, with farmland (15,575 ha), forest (14,526 ha), grassland (20,433 ha), and other land uses (11,822 ha). The population (2024) was 81,700 (41,509 males; 40,191 females), predominantly practicing mixed crop-livestock farming. Major crops included wheat, teff, sorghum, maize, and pea. Orthodox Christianity was the dominant religion (97.56%), followed by Islam (2.44%).

Climatic data for the Meketewa District (2010 to 2024) was retrieved from the NASA POWER Data Access Viewer (DAV). Analysis performed using R software (version 4.3.3) revealed a mean annual temperature of 21.5 °C and a mean annual precipitation of 1462 mm, characterized by a unimodal distribution (Fig. 2). Additionally, the annual minimum and maximum temperatures were 13.8 °C and 30.2 °C, respectively.

Reconnaissance survey and site selection

Based on a reconnaissance survey conducted from October 10 to 20, 2024, five out of twelve kebeles (sub-District) in the Meketewa District were selected for a study. This selection, representing 42% of the total kebeles (sub-District), was made using a stratified sampling method based on agroecology. The selection criteria included accessibility, availability of sufficient vegetation as a reservoir of medicinal plants, and the presence of traditional healers, particularly key informants. These criteria were determined in consultation with District leaders and community elders to ensure a thorough representation of the District’s ecological and sociocultural diversity, which would enable an in-depth investigation of indigenous knowledge related to traditional medicine.

Sample size determination and informant selection

The sample size was determined using Cochran’s formula13:\(\:\:n=\frac{N}{1+N\left({e}^{2}\right)}\), where n is the sample size, N is the total number of households in selected Kebeles (sub-Districts), and e is the margin error (0.05)2 at 95% confidence level. The number of informants from each Kebele (sub-District) was determined using the formula: number of households in one kebele (sub-District)/total number of households in all kebeles) x total sample size. A total of 360 (340 general informants, 20 key informants), were selected with a gender distribution of 211 men and 149 women (Table 1). General informants were selected through random sampling, while key informants were chosen via purposive sampling based on recommendations from local leaders and the community elders. Key informants were selected based on their extensive knowledge and experience with traditional medicinal practices. Typically, these individuals are local healers, herbalists, or community elders who possess unique insights into the use and cultural significance of medicinal plants. In contrast, general participants were selected from the local community without specific qualifications in ethnomedicine. This distinction is crucial as it shapes the depth of information gathered.

Data collection and voucher specimen identification

This study was conducted in accordance with relevant institutional, national, and international guidelines and legislation. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Prior permission for the collection of plant materials was obtained from the Meketewa District Administration Office and the respective kebele (Sub-District) leaders. Ethnobotanical data were collected through established protocols using semi-structured interviews, focus group discussions (FGDs), and guided field walks14,15. Each FGD included 12 informants (6 men and 6 women), organized by gender to facilitate open communication and address gender-specific perspectives16. The fieldwork employed equipment such as Questionnaire sheets, field guide, GPS, polyethylene bags, plant presses, data sheets, secateurs, a camera, and a hand lens. During guided field walks, plant voucher specimens were actively collected for the purpose of this study. Each specimen was numbered, pressed, and dried, and identified by senior botanists Getinet Masresha (Ph.D.) and Endale Adamu (Ph.D.) using the Flora of Ethiopia and Eritrea. Pressed specimens were deposited at Debre Tabor University Herbarium with assigned voucher numbers FK01 to FK76 (See supplementary files 1–3). The scientific names of the medicinal plants were thoroughly verified using two reputable world flora databases: World Flora Online (https://www.worldfloraonline.org/) and Plants of the World Online|Kew Science (POWO) (https://powo.science.kew.org/). This verification process ensured that the names were accurate and up-to-date, aligning with current taxonomic standards. Each species was cross-referenced in both databases to confirm its accepted nomenclature, synonyms, and distribution, thereby reinforcing the reliability of the information presented in our study. This rigorous approach provides a solid foundation for our findings and enhances the overall credibility of the research. To enhance data validity and reliability, a triangulation technique was applied17, incorporating multiple data collection methods to cross-validate findings and mitigate bias.

Data analyses

Basic ethnobotanical data were analyzed and presented in graphs and tables. Mean comparisons of indigenous and local knowledge on medicinal plants across various socio-demographic and socio-economic factors were conducted using SPSS version 25. Two-tailed independent samples t-tests identified differences between two categorical parameters, while one-way ANOVA assessed variances among three or more categorical variables. Post hoc analyses, including Tukey’s Honest Significant Difference (HSD) and Least Significant Difference (LSD) tests, examined specific group differences within variables with multiple categorical levels. Additionally, preference ranking, direct matrix ranking, informant consensus factor, the Jaccard similarity index (JSI), and Rahman’s Similarity Index (RSI) were employed for quantitative analyses of the ethnobotanical data.

Preference ranking

The preference ranking exercise was conducted with ten key informants to assess the cultural significance of five selected medicinal plants, following standard ethnobotanical methods15. Each informant independently ranked the plants on a scale of 1 (least preferred) to 5 (most preferred) based on two key criteria: their personal experience with each plant’s therapeutic effectiveness and their perception of its importance within the community. The total scores for each plant were then summed to determine the overall ranking.

Direct matrix ranking (DMR)

DMR, following15,18, was used to identify medicinal plants under the greatest pressure and their respective threats. Ten key informants evaluated five multipurpose medicinal plants across six use categories (material culture, construction, firewood, charcoal, fence, and medicine). Informants assigned the following values for each use categories (5 = best, 4 = very good, 3 = good, 2 = less used, 1 = least used, 0 = not used). Subsequently, the values assigned to each use category and species were averaged and ranked accordingly.

Informant consensus factor (ICF)

Reported human and livestock ailments were categorized with modifications based on the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision (ICD-11)19. To evaluate the level of agreement among informants, the Informant Consensus Factor (ICF) was calculated for each disease category. The ICF, which ranges from 0 to 1, measures the degree of consensus among informants regarding the medicinal use of plants for specific ailments. A value near 0 indicates a lack of agreement, suggesting diverse opinions or knowledge. Conversely, a value approaching 1 shows strong consensus, emphasizing the cultural importance and perceived effectiveness of certain plants in traditional medicine for both human and animal health. The formula used was: \(\:\text{I}\text{C}\text{F}=\frac{\text{n}\text{u}\text{r}-\text{n}\text{t}}{\text{n}\text{u}\text{r}-1}\), where nur is the total number of use citations within a disease category, and nt is the number of plant species cited for that category15.

Index of fidelity FL

Index of fidelity (FL) was used to determine relative healing potential of medicinal plants using the formula20: \(\:\text{F}\text{L}=\frac{\text{I}\text{P}}{\text{I}\text{U}}\) × 100, where, IP= the number of informants who independently cited the importance of a species for treating a particular disease, and IU = the total number of informants who reported the plant for any given diseases.

Jaccard’s similarity index

Jaccard’s similarity index (JSI%) was employed to compare the medicinal plant composition similarity or dissimilarity utilized in this study with previous research works. This analysis focused on the percentages of quoted species. The calculation for Jaccard’s similarity index followed21,22. \(\:\text{J}\text{S}\text{I}\left(\text{\%}\right)=(\frac{c}{a+b-c}\)) × 100, where a = number of species only in the current study, b = number of species only in previous study, and c = number of common species in the current study and previous studies.

Rahman’s similarity index

The Rahman’s Similarity Index (RSI) is a valuable metric for evaluating the cross-cultural similarities in indigenous knowledge between different communities23. This index helps to illuminate how communities engage with their natural environment and the cultural importance they place on certain plants. The RSI is calculated as a percentage using the formula: \(\:\text{R}\text{S}\text{I}=\frac{\text{N}\text{d}}{\text{N}\text{a}+\text{N}\text{b}+\text{N}\text{c}-\text{N}\text{d}}\:\times\:100\). In this formula, Na represents the number of unique species in community A, Nb is the number of unique species in community B, Nc is the total number of species common to both communities, and Nd is the number of common species used for treating similar ailments in both communities. The values of Nc and Nd must be greater than or equal to zero, which ensures a valid comparison of shared medicinal plant knowledge.

Results

Factors influencing traditional medicinal plant knowledge

Statistical analysis revealed significant variations (p < 0.05) in traditional medicinal plant knowledge scores, defined as the total number of medicinal plant species and their associated uses correctly reported by each informant, across different socio-demographic and ecological parameters (Table 2). Agroecological patterns showed lowland informants possessed significantly greater knowledge (10.40 ± 3.8) than midland (9.04 ± 3.5) and highland (8.90 ± 3.4) communities (F = 6.98, p = 0.001). Expertise level substantially influenced knowledge retention, with key informants demonstrating markedly higher understanding (18.65 ± 2.3) than general informants (9.19 ± 3.0) (F = 191.36, p = 0.000). Gender-based analysis showed that men (n = 211) had significantly higher medicinal plant knowledge scores (10.27 ± 3.9), reflecting the average number of medicinal plant species and uses reported, than women (n = 149; 8.95 ± 3.1) (F = 11.58, p = 0.001). Age stratification revealed elderly informants (≥ 60 years, n = 93) maintained the most comprehensive knowledge (12.54 ± 3.9), followed by middle-aged (40–59 years, 9.07 ± 2.5) and younger (20–39 years, 8.5 ± 3.4) participants (F = 47.40, p = 0.000). Educational status also significantly affected knowledge preservation, with illiterate individuals demonstrating higher knowledge levels (10.12 ± 3.6) than literate participants (7.33 ± 3.1) (F = 27.67, p = 0.000).

Medicinal plant diversity

The study identified 76 medicinal plants belonging to 74 genera and 46 families, with the Fabaceae family was the dominant one at 7.9% (n = 6), followed by Asteraceae, Lamiaceae, and Solanaceae at 6.6% each (n = 5) (See supplementary files 1–3). Of these plants, 48 (63.2%) were utilized exclusively for human ailments, 7 (9.2%) for livestock, and 21 (27.6%) for both (Fig. 3A). The majority were sourced from wild habitats (61.84%, n = 47), with 31.58% (n = 24) from home gardens and a small proportion (6.58%, n = 5) from both sources ((Fig. 3B). Growth form analysis showed herbaceous species predominated (38.16%, n = 29), followed by shrubs (35.53%, n = 27), trees (17.11%, n = 13), and climbers (9.21%, n = 7) ( (Fig. 3C).

Plant parts, preparation, and rout of administration

The study revealed distinct patterns in the utilization of medicinal plant parts. Leaves were the most frequently used (45.03%, n = 68), followed by roots (28.48%, n = 43) and seeds (8.61%, n = 13). Stem bark accounted for 7.28% (n = 11) of preparations, while other plant parts including stems (3.31%, n = 5), latex (3.97%, n = 6), fruits (2.65%, n = 4), and bulbs (0.66%, n = 1) were less commonly employed (Fig. 4A). A strong preference was observed for fresh plant materials (72.8%, n = 110) over dried preparations (25.2%, n = 38). Only a small proportion of remedies (2%, n = 3) utilized in both fresh and dried (Fig. 4B).

Regarding preparation methods, crushing was the most prevalent technique (38.4%, n = 58), followed by grinding (13.9%, n = 21) and squeezing (11.3%, n = 17), while other methods such as direct use (2%, n = 3), smoking (3.3%, n = 5), and latex extraction (5.3%, n = 8) were less frequent (Fig. 4C). Rare preparation techniques included burning (0.7%, n = 1), pounding (0.7%, n = 1), smelling (0.7%, n = 1), and heating (1.3%, n = 2). In terms of administration routes, oral intake was the most common (47.7%, n = 72), followed by dermal application (31.8%, n = 48). Nasal administration accounted for 9.9% (n = 15), while optical (5.3%, n = 8), tying (2%, n = 3), and other methods (2.6%, n = 4) were less frequently used (Fig. 4D).

Additives, antidotes, side effects and dosage for remedy preparation

Additives like honey, butter, sugar, and milk were commonly used to enhance medicinal remedies. Honey not only improved taste but also acted as a preservative, while butter served as a base for topical applications. Sugar made bitter remedies more palatable, and milk facilitated the delivery of active compounds. Occasionally, salt and local beer (tella) was used for their antiseptic or solvent properties.

However, some remedies caused adverse effects, necessitating the use of antidotes. For example, coffee was administered to counteract vomiting induced by Calpurnia aurea subsp. indica root, while local beer helped reduce inflammation after treatment with Clematis hirsuta. In cases of skin irritation from Clematis hirsuta combined with salt, infant urine was used to wash the skin, effectively neutralizing discomfort.

Certain treatments led to side effects such as skin irritation, burning sensations, or nausea. For instance, Calotropis procera latex caused skin peeling; Capsicum annuum induced a burning sensation on wounds, and Cucumis ficifolius root triggered vomiting. Additionally, Clematis hirsuta and Euclea racemosa subsp. schimperi were associated with inflammation.

Traditional healers utilized locally recognized measurement units for preparing remedies. Liquid preparations were often measured in practical volumes like cups (e.g., “one coffee cup”), cans, or liters (e.g., Aloe debrana root infusion). For solid plant materials such as leaves, buds, and fruits, practitioners typically employed countable units (e.g., “three seeds” of Linum usitatissimum) or approximate measures like handfuls. Some treatments specified prolonged administration periods, such as the consumption of Phytolacca dodecandra root during pregnancy, reflecting the community’s comprehensive approach to herbal medicine.

Ethnobotanical indices of human and livestock medicinal plants

Preference ranking

The preference ranking results for medicinal plants treating human tonsillitis revealed distinct community preferences, with Rhamnus prinoides ranking first (total score = 44), demonstrating its highest cultural importance and perceived efficacy among the five medicinal plants (Table 3). Jasminum grandiflorum closely followed (score = 43, 2nd ), while Euclea racemosa subsp. schimperi (score = 23, 3rd ) and Cucumis ficifolius (score = 22, 4th ) showed moderate preference. Ximenia americana ranked lowest (score = 18, 5th ), suggesting relatively lesser use or perceived effectiveness.

The preference ranking results for medicinal plants treating livestock swelling revealed distinct community preferences, with Euphorbia abyssinica ranking first (total score = 31), demonstrating its highest cultural importance and perceived efficacy among the four medicinal plants (Table 4). Calotropis procera closely followed (score = 29, 2nd ), while Ricinus communis (score = 21, 3rd ) showed moderate preference. Clematis hirsuta ranked lowest (score = 19, 4th), suggesting relatively lesser use or perceived effectiveness for this specific ailment. The findings reflect local ethnoveterinary knowledge and practical plant selection for managing livestock health conditions.

Informant consensus factor (ICF)

The Informant Consensus Factor (ICF) values ranged from 0 to 0.92 (Table 5). The highest ICF values were for respiratory diseases (ICF = 0.92), infectious/parasitic conditions (ICF = 0.88), and injuries/poisonings (ICF = 0.86), respectively. Moderate consensus appeared for nervous system disorders (ICF = 0.85) and general symptoms (ICF = 0.84), while lower but still notable agreement occurred for digestive (ICF = 0.79) and musculoskeletal conditions (ICF = 0.73). The weakest consensus emerged for circulatory disorders (ICF = 0.67), and there was no agreement for the treatment of sexual health issues, as indicated by an ICF of zero for gonorrhea.

Direct matrix ranking

The DMR analysis of six multipurpose medicinal plant species revealed distinct utility patterns, with Olea europaea subsp. cuspidata ranking first followed by Croton macrostachyus, and Carissa spinarum (Table 6). The ranking exercise also identified firewood harvesting, construction purposes and charcoal production as the most intensive utilization categories, representing the primary anthropogenic pressures on these medicinal plant resources.

Fidelity level (FL)

The fidelity level analysis revealed strong informant consensus for several key medicinal plants, indicating their cultural and therapeutic importance (FL > 50%) (Table 7). Asparagus africanus var. puberulus had the highest FL (83.3%), reflecting consistent use across multiple human and livestock ailments, including evil eye, scorpion bite, abdominal pain, wounds, and fasciolosis. Rhamnus prinoides also showed high fidelity (75%) for treating tonsillitis, while Cucumis ficifolius and Euphorbia abyssinica (73.3%), Clematis hirsuta (72%), and Calotropis procera (71.4%) demonstrated strong agreement for specific ailments such as anthrax, livestock swelling, tumors, rheumatism, and hemorrhoids. Allium sativum exhibited moderate fidelity (60%) for common cold, reflecting broader but less specific use, and Ricinus communis showed the lowest FL (50%), indicating more generalized application across different conditions rather than specialization for a single ailment. These high FL values highlight plants with well-established traditional use and prioritize them for future phytochemical and pharmacological investigation.

Jaccard’s similarity index (JSI)

The Jaccard Similarity Index (JSI) analysis of medicinal plant composition in Meketewa District, when compared with previous studies, revealed a range of 2.29% to 45.19% (Table 8). The highest similarities were observed with Raya Kobo (JSI = 45.19%), Sedie Muja (JSI = 27.05%), and Hulet Eju Enese (JSI = 24.37%). In contrast, the lowest similarities were recorded with South Omo (JSI = 3.05%), Berbere (JSI = 2.82%), and Wonago (JSI = 2.29%).

Rahman’s similarity index (RSI)

The cross-cultural comparison of Rahman’s similarity index for medicinal plants in the current study with previous studies revealed a range of similarity values from 0.00% to 16.67% (Table 9). The highest similarity was observed between the current study and Raya Kobo (RSI = 16.67%), followed by Addi Arkay (RSI = 11.29%) and Sedie Muja (RSI = 11.11%). Conversely, the lowest similarity indices were found between Kilte Awulaelo (RSI = 0.57%), Heban-Arsi (RSI = 0.56%), and Wonago (RSI = 0.00%).

Novel ethnobotanical findings

Previously unreported ethnobotanical practices in this study were documented. These included the use of Achyranthes aspera leaves for treating Herpes Zoster (the leaves were chewed and swallowed) and the application of Arisaema schimperianum roots tied around the neck to manage febrile illnesses. Mechanical application methods were also recorded, such as inserting three Linum usitatissimum (flax) seeds directly into the eye to remove foreign bodies. Culturally unique practices included remedies for the evil eye, involving the inhalation of Asparagus africanus var. puberulus in combination with Allium sativum (garlic) and Ruta graveolens (rue). Additionally, veterinary applications were noted, such as the use of Ricinus communis (castor) leaves to repair broken cattle horns to prevent worm infestation.

Discussions

Factors influencing traditional medicinal plant knowledge

The study revealed several key patterns in the distribution of traditional medicinal plant knowledge across different demographic and ecological contexts. Notably, communities in lowland areas demonstrated more extensive knowledge compared to those in midland and highland regions, primarily due to greater biodiversity, vulnerability to many infectious diseases, and easier access to medicinal plants in these ecosystems. These findings were consistent with both empirical observations of ecology’s influence on traditional knowledge and the theoretical framework of ecological determinism, which explained medicinal knowledge development as an adaptive response to environmental pressures and health need10,51.

Furthermore, the analysis identified that key informants maintained substantially more detailed understanding of medicinal plant knowledge than general informants. This concentration of expertise underscored the sophisticated nature of traditional medicinal plant knowledge and its vulnerability; as such knowledge risked being lost without proper transmission mechanisms52. Moreover, the observed age-related differences, where elders possessed more comprehensive knowledge than younger generations, supported concerns about the ongoing erosion of traditional knowledge in contemporary societies53. In addition, gender differences in knowledge levels emerged as another significant finding, consistent with documented patterns of gendered knowledge distribution in ethnobotanical studies54. Interestingly, the study revealed that illiterate informants demonstrated greater medicinal plant knowledge than their literate counterparts. This finding aligned with previous research emphasizing the importance of oral transmission pathways in traditional knowledge preservation42,55,56. Illiterate individuals typically acquired and retained ethnobotanical knowledge through direct, experiential learning and cultural immersion, which appeared to foster deeper retention of practical plant, uses55. In contrast, literate informants often prioritized formal education and modern healthcare systems, which may have reduced their engagement with traditional medicinal practices9. Thus, this paradox necessitated innovative approaches to education that respected and incorporated indigenous knowledge systems rather than displacing them.

Medicinal plant diversity

The documentation of 76 medicinal plants in this study highlighted the significance of traditional knowledge and practices for the local healthcare system. Compared to previous reports, this figure is higher than those recorded in Aleta-Chuko (n = 47)26, Damot Woyde (n = 51)30, Diguna Fango (n = 45)32, Gera (n = 63)35, South Omo (n = 59)46 and Wonago (n = 58)49; and lower in Ada’a (n = 112)16, Mana Angetu (n = 212)41, Ganta Afeshum (n = 153)34. These comparisons highlighted the variability in medicinal plant diversity across different regions in Ethiopia, suggesting that ecological factors and cultural practices significantly influenced the richness of traditional medicinal knowledge. The predominance of Fabaceae as the most utilized medicinal plant family in this study aligns with findings from other Ethiopian ethnobotanical research57,58. This recurrent pattern was attributed to the ecological adaptability of the species, cultural significance, therapeutic potential, and the ease of harvesting and processing within local medicinal practices10,59.

Traditional medicinal plant use in this community predominantly served human healthcare, with significant dual applications for both human and veterinary medicine. This finding was aligned with58,60,61. The pronounced focus on human health likely stems from multiple factors including disease burden, healthcare accessibility, and cultural valuation of human versus animal wellbeing62. Notably, the substantial overlaps in human and veterinary remedies demonstrate the integrated nature of traditional healthcare systems in agrarian societies, where human and animal health is often addressed through similar botanical approaches16. Harvesting medicinal plants primarily from wild habitats or natural forests in this study highlighted the need for conservation efforts. Similar patterns were documented in other studies, where the reliance on wild resources raised significant concerns about sustainability and biodiversity loss10,63. The growth forms of the identified plants further indicated a community preference for herbaceous species, in line with findings from42,64, which were easier to access and utilize. This preference contrasted with findings from some East African studies, where shrubs were more commonly used due to their drought resistance and year-round availability, making them reliable resources for medicinal use65.

Plant parts, preparation, and rout of administration

The results of this study revealed significant patterns in the utilization of medicinal plant parts within the community, with a predominant use of leaves suggesting a well-established preference for this plant part aligned with1,58 in Ethiopia and elsewhere66,67. The could be due to their rich concentration of diverse secondary metabolites, abundant and renewable parts of medicinal plants, making them easier to harvest sustainably without killing the plant, ease of preparation in forms of infusions, decoctions, and powders68,69. The community’s strong preference for using fresh plant materials in traditional medicine preparations reflected a widespread belief in their superior efficacy as it was also reported in previous studies1,59. This enhanced potency was attributed to the preservation of volatile and water-soluble constituents, which could degrade or diminish during drying59. Oral intake was the primary route of administration in the study area, consistent with previous studies28,70, likely due to the facilitated systemic absorption of medicinal compounds, aligning with the widespread use of decoctions, infusions, and fresh plant juices across diverse cultures.

Additives, antidotes, side effects and dosage for remedy preparation

The preparation and administration of traditional remedies in this study reveal a sophisticated system of pharmacological knowledge, reflecting both practical adaptations and potential risks. The use of additives like honey, butter, and milk aligns with global ethnopharmacological practices, where these substances enhance palatability, bioavailability, and preservation of active compounds26,71. Honey’s dual role as a sweetener and antimicrobial agent and butter’s function as a lipid-soluble carrier for topical applications72,73, demonstrate the empirical understanding of drug delivery systems in traditional medicine.

The documented antidote protocols, such as using coffee to counteract vomiting from Calpurnia aurea, underscore an advanced awareness of plant toxicity and therapeutic modulation. Similar antidote traditions have been reported in other cultures, suggesting the universal development of detoxification strategies in traditional pharmacopeias74,75. However, the frequent side effects (e.g., skin irritation from Calotropis procera latex) highlight safety concerns that warrant further toxicological evaluation, particularly for plants with known cytotoxic compounds71. The standardized measurement systems using cups, handfuls, or countable units in our study revealed a pragmatic approach to dosage standardization, bridging the gap between traditional knowledge and reproducible formulations76. Prolonged administration periods, such as the use of Phytolacca dodecandra during pregnancy, raise important questions about chronic toxicity and teratogenicity that demand scientific validation77.

Ethnobotanical indices of human and livestock medicinal plants

The preference ranking results reveal distinct patterns in how communities prioritize medicinal plants for specific ailments, reflecting deep-rooted ethnobotanical knowledge and perceived efficacy. Rhamnus prinoides and Euphorbia abyssinica emerged as the most valued species for human tonsillitis and livestock swelling, respectively, underscoring their cultural significance and therapeutic reliability a pattern consistent with other Ethiopian studies where these species are similarly prioritized60,75,78. In contrast, the lower ranking of Ximenia americana and Clematis hirsuta suggests context-specific variations in plant utility, diverging from reports in pastoral regions where these species hold greater prominence79. It has documented uses for treating wounds, eye infections, and uvulitis but varies in prominence across regions80.

The high informant consensus factor (ICF) for respiratory and infectious diseases highlights remarkable consistency in traditional treatment approaches for these conditions, mirroring findings from comparable studies in Ethiopia1. However, the absence of consensus (ICF = 0) for gonorrhea treatments contrasts sharply with research in southern Ethiopia, where well-established remedies exist81, suggesting either knowledge erosion or cultural reticence in discussing sexual health. The multipurpose utility ranking exposes critical conservation challenges, with Olea europaea and Croton macrostachyus facing intense anthropogenic pressure a trend alarmingly consistent across Ethiopian highlands78. The predominant use for firewood and construction aligns with findings from similar agroecological zones82, though the current study reveals more severe exploitation rates, signaling escalating resource scarcity.

The high fidelity level values observed for several medicinal plant species in this study reflect a strong cultural consensus on their therapeutic importance, highlighting their central role in local healthcare practices. These patterns are consistent with other Ethiopian ethnobotanical studies, where certain taxa, including Rhamnus prinoides and Cucumis ficifolius, were reported to have high informant agreement for specific ailments, indicating well-established traditional usage and potential bioactivity recognized by local communities61,83. Similar trends have been observed across diverse Ethiopian Districts, where culturally prioritized species have been identified as key candidates for further phytochemical and pharmacological investigation, as well as targeted conservation initiatives16,84.

Jaccard’s Similarity Index (JI) provided valuable insights into the composition of medicinal plants used across different regions, highlighting both shared knowledge and specific medicinal plant species85. In the current study, the highest similarity was observed with Raya Kobo43, Sedie Muja36, and Hulet Eju Enese37, indicating an ecological similarity linked to plant diversity and traditional practices among these communities. Conversely, the low similarities with South Omo45, Berbere28, and Wonago49 reflected significant variations in local ecological factors and cultural practice that shaped the use of medicinal plants. Rahman’s similarity index (RSI) further emphasized the localized nature of medicinal plant knowledge by comparing cross-cultural practices85. The highest similarity values were recorded with Raya Kobo43, followed by Addi Arkay16 and Sedie Muja36, implying that neighboring communities shared a common heritage in their medicinal practices. In contrast, the lower similarity indices with Kilte Awulaelo38, Heban-Arsi36, and Wonago49 highlighted that geographically distant and isolated communities developed unique medicinal strategies. These findings underscored the importance of documenting and preserving traditional knowledge, which not only contributed to biodiversity conservation but also enhanced the integration of traditional and modern healthcare systems, ensuring sustainable health practices within diverse cultural context.

Novel ethnobotanical findings

This study unveils novel ethnobotanical practices, including the use of Achyranthes aspera leaves for treating Herpes Zoster, despite being previously reported for conditions such as tonsillitis, eye infections, anthrax, urinary retention, snake bites, and wounds60. Additionally, the use of Arisaema schimperianum roots for managing febrile illnesses was a novel finding, although it has been reported for other conditions like birth difficulties86, abdominal pain87, and Gastrointestinal disorder88. Unique mechanical applications, such as Linum usitatissimum seeds for removing ocular foreign bodies, also emerge as a novel report in this study, even though the plant has been noted for its anti-cancer, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and digestive health benefits89, as well as its use for constipation, cholesterol, diabetes, and kidney issues90. Culturally specific remedies for the evil eye, involving Asparagus africanus var. puberulus in combination with Allium sativum and Ruta graveolens, were novel to our study, despite previous reports of these plants for uses such as hematuria, hemorrhoids, malaria, leishmaniasis, bilharziasis, syphilis, gonorrhea, and relief from pain, rheumatism, and chronic gout91. Finally, the use of Ricinus communis (castor) leaves to repair broken cattle horns and prevent worm infestation was another novel finding, although this plant has been documented for various medicinal uses, including abdominal disorders, arthritis, backache, muscle aches, bilharziasis, chronic headache, constipation, expulsion of the placenta, gallbladder pain, menstrual cramps, rheumatism, sleeplessness, and insomnia92.

Conclusions and recommendations

This study documented the ethnobotanical knowledge of the Meketewa District, identifying 76 medicinal plants used for human and livestock ailments, reflecting a complementary healthcare system across species. Knowledge distribution was influenced by agroecology, gender, age, and literacy, with elders and key informants serving as important knowledge sources, highlighting the potential value of targeted knowledge-preservation programs. The reliance on wild-harvested materials, particularly roots and multipurpose trees such as Olea europaea subsp. cuspidata, raises sustainability concerns, underscoring the need to explore cultivated alternatives and structured conservation initiatives.

High fidelity level values for species such as Asparagus africanus, Rhamnus prinoides, Cucumis ficifolius, and Euphorbia abyssinica demonstrate strong cultural consensus on their therapeutic importance, identifying these species as priority candidates for phytochemical and pharmacological validation. The frequent use of fresh plant materials, with crushing as the primary preparation method and oral administration as the most common route, reflects traditional strategies to maximize therapeutic potential, while the use of additives and antidotes indicates advanced traditional pharmacological knowledge. High preference ranking for species such as Rhamnus prinoides (used for human tonsillitis) and Euphorbia abyssinica (used for livestock swelling) reinforces their cultural significance and suitability for further scientific study. Novel applications, including the use of Achyranthes aspera for Herpes Zoster, expand the ethnobotanical record and highlight opportunities for future research. Variability in JSI and RSI values highlights both shared and unique elements of regional ethnobotanical knowledge, supporting continued documentation efforts.

We recommend the implementation of community-based conservation programs that integrate both in situ approaches, such as the protection of natural forests, and ex situ strategies, including homegardens, to safeguard threatened medicinal plant species. In addition, future phytochemical and pharmacological investigations, encompassing both in vitro and in vivo studies, are strongly encouraged to scientifically validate the efficacy and safety of these medicinal plants.

Limitations of this study

The findings of this study are based on self-reported information obtained from informants, which may be subject to recall bias and variations in individual knowledge and experience. Additionally, the efficacy and safety of the documented medicinal plant remedies were not experimentally assessed; therefore, all reported therapeutic uses are based solely on traditional knowledge and informant consensus rather than empirical biochemical or pharmacological evidence.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are presented in the tables and figures within the manuscript and supplementary file.

References

Alemu, M. et al. Ethnobotanical study of traditional medicinal plants used by the local people in Habru District, North Wollo Zone, Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 20, 4 (2024).

Majeed, M. Evidence-based medicinal plant products for the health care of world population. Ann. Phytomed. 6, 1–4 (2017).

Zhang, Q., Sharan, A., Espinosa, S. A., Gallego-Perez, D. & Weeks, J. The path toward integration of traditional and complementary medicine into health systems globally: The World Health Organization report on the implementation of the 2014–2023 strategy. Medicine 25, 869–871 (2019).

Park, Y. L. & Canaway, R. Integrating traditional and complementary medicine with national healthcare systems for universal health coverage in Asia and the Western Pacific. Health Syst. Reform. 5, 24–31 (2019).

Ouma, A. Intergenerational learning processes of traditional medicinal knowledge and socio-spatial transformation dynamics. Front. Sociol. 7, 661992 (2022).

Banerjee, S. Introduction to ethnobotany and traditional medicine. In Traditional Resources and Tools for Modern Drug Discovery Ethnomedicine and Pharmacology. 1–30. (Springer, 2024).

Ekor, M. The growing use of herbal medicines: Issues relating to adverse reactions and challenges in monitoring safety. Front. Pharmacol. 4, 177 (2014).

Suleman, S. et al. Pharmaceutical regulatory framework in Ethiopia: A critical evaluation of its legal basis and implementation. Front. Pharmacol. 4, 177 (2014).

Awoke, A., Siyum, Y., Awoke, D., Gebremedhin, H. & Tadesse, A. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants and their threats in Yeki District, Southwestern Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 20, 107 (2024).

Derso, Y. D. et al. Composition, medicinal values, and threats of plants used in Indigenous medicine in Jawi District, Ethiopia: Implications for conservation and sustainable use. Sci. Rep. 14, 23638 (2024).

Alemu, M. M. Indigenous and medicinal uses of plants in Nech Sar National Park, Ethiopia. Open. Access. Libr. J. 4, 1 (2017).

Bekele-Tesemma, A. Useful trees and shrubs for Ethiopia. Identification, propagation and management for 17 agroclimatic zones. (2007).

Cochran, W. G. Sampling Techniques (Wiley, 1977).

Alexiades, M. N. Collecting ethnobotanical data: An introduction to basic concepts and techniques. Adv. Econ. Bot. 10, 53–94 (1996).

Martin, G. J. Ethnobotany: A Methods Manual. (Routledge, 2010).

Misganaw, W., Masresha, G., Alemu, A. & Lulekal, E. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used to treat human and livestock ailments in addi Arkay District, Northwest Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 21, 31 (2025).

Khakurel, D., Uprety, Y., Łuczaj, Ł. & Rajbhandary, S. Foods from the wild: Local knowledge, use pattern and distribution in Western Nepal. PLoS One. 16, e0258905 (2021).

Cotton, C. M. Ethnobotany: Principles and Applications. (1996).

World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics (ICD-11). (World Health Organization, 2018).

Balick, M. & Cox, A. Plants that Heal; People and Culture: The Science of Ethno Botany. (1996).

Jaccard, P. Lois de distribution florale dans la zone alpine. Bull. Soc. Vaudoise Sci. Nat. 38, 69–130 (1902).

Kayani, S. et al. Ethnobotany of medicinal plants among the communities of alpine and sub-alpine regions of Pakistan. J. Ethnopharmacol. 164, 186–202 (2015).

Rahman Iu, Hart, R. et al. Sm, Alqarawi, Aa, Alsubeie Ms, Bussmann, Rw. A new ethnobiological similarity index for the evaluation of novel use reports. Appl. Eco Environ. Res. 17, 4–5 (2019).

Tahir, M., Gebremichael, L., Beyene, T. & Van Damme, P. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in Adwa District, central zone of Tigray regional state, Northern Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 17, 1–13 (2021).

Gebre, T. & Chinthapalli, B. Ethnobotanical study of the traditional use and maintenance of medicinal plants by the people of Aleta-Chuko Woreda, South Ethiopia. Phcog J. 13 (2021).

Yimam, M., Yimer, S. M. & Beressa, T. B. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used in Artuma Fursi District, Amhara regional state, Ethiopia. Trop. Med. Health. 50, 85 (2022).

Megersa, M. & Tamrat, N. Medicinal plants used to treat human and livestock ailments in basona werana District, north shewa zone, amhara region, Ethiopia. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2022, 5242033 (2022).

Jima, T. T. & Megersa, M. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used to treat human diseases in Berbere District, Bale Zone of Oromia Regional State, South East Ethiopia. Altern. Med. 2018, 8602945 (2018).

Megersa, M. & Woldetsadik, S. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used by local communities of Damot Woyde District, Wolaita Zone, Southern Ethiopia. Nusant Biosci. 14, 1 (2022).

Getaneh, S. & Girma, Z. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in Debre Libanos Wereda, Central Ethiopia. Afr. J. Plant. Sci. 8, 366–379 (2014).

Wendimu, A., Tekalign, W. & Asfaw, B. A survey of traditional medicinal plants used to treat common human and livestock ailments from Diguna Fango District, Wolaita, Southern Ethiopia. Nord. J. Bot. 39 (2021).

Birhan, Y. S., Kitaw, S. L., Alemayehu, Y. A. & Mengesha, N. M. Medicinal plants with traditional healthcare importance to manage human and livestock ailments in Enemay District, Amhara Region, Ethiopia. Acta Ecol. Sin. 43, 382–399 (2023).

Kidane, L., Gebremedhin, G. & Beyene, T. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in Ganta Afeshum District, eastern zone of Tigray, northern Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 14, 1–19 (2018).

Gonfa, N., Tulu, D., Hundera, K. & Raga, D. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants, its utilization, and conservation by Indigenous people of Gera District, Ethiopia. Cogent Food Agric. 6, 1852716 (2020).

Tefera, B. N. & Kim, Y. D. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in the Hawassa Zuria District, Sidama zone, Southern Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 15, 1–21 (2019).

Nuro, G., Tolossa, K., Arage, M. & Giday, M. Medicinal plants diversity among the oromo community in heban-arsi district of Ethiopia used to manage human and livestock ailments. Front. Pharmacol. 15, 1455126 (2024).

Abebe, B. A. & Chane Teferi, S. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used to treat human and livestock ailments in Hulet Eju Enese Woreda, east Gojjam zone of Amhara region, Ethiopia. Altern. Med. 2021, 6668541 (2021).

Teklay, A., Abera, B. & Giday, M. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used in Kilte Awulaelo District, Tigray region of Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 9, 1–23 (2013).

Bekalo, T. H., Woodmatas, S. D. & Woldemariam, Z. A. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used by local people in the lowlands of Konta special Woreda, southern nations, nationalities and peoples regional state, Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 5, 26 (2009).

Lulekal, E., Kelbessa, E., Bekele, T. & Yineger, H. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in Mana Angetu District, southeastern Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 4, 1–10 (2008).

Mengesha, G. G. Ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants used in treating human and livestock health problems in Mandura Woreda of Benishangul Gumuz, Ethiopia. Adv. Med. Plant. Res. 4, 11–26 (2016).

Girma, Z., Abdela, G. & Awas, T. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plant species in Nensebo District, south-eastern Ethiopia. Res. Appl. 24, 1–25 (2022).

Osman, A., Sbhatu, D. B. & Giday, M. Medicinal plants used to manage human and livestock ailments in Raya Kobo District of Amhara Regional State, Ethiopia. Altern. Med. 2020, 1329170 (2020).

Araya, S., Abera, B. & Giday, M. Study of plants traditionally used in public and animal health management in Seharti Samre District, Southern Tigray, Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 11, 1–25 (2015).

Tolossa, K. et al. Ethno-medicinal study of plants used for treatment of human and livestock ailments by traditional healers in South Omo, Southern Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 9, 1–15 (2013).

Lulesa, F., Alemu, S., Kassa, Z. & Awoke, A. Ethnobotanical investigation of medicinal plants utilized by Indigenous communities in the Fofa and Toaba sub-districts of the Yem Zone, Central Ethiopian region. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 21, 1–50 (2025).

Bogale, M., Sasikumar, J. & Egigu, M. C. An ethnomedicinal study in Tulo District, West Hararghe zone, Oromia region, Ethiopia. Heliyon 9 (2023).

Mesfin, F., Demissew, S. & Teklehaymanot, T. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in Wonago Woreda, SNNPR, Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 5, 1–18 (2009).

Teklehaymanot, T. An ethnobotanical survey of medicinal and edible plants of Yalo Woreda in Afar regional state, Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 13, 1–26 (2017).

Kefalew, A., Asfaw, Z. & Kelbessa, E. Ethnobotany of medicinal plants in Ada’a District, East Shewa zone of Oromia regional state, Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 11, 1–28 (2015).

Molares, S., Ciampagna, M. L. & Ladio, A. H. Digestive plants in a Mapuche community of the Patagonian steppe: Multidimensional variables that affect their knowledge and use. (2023).

d’Avigdor, E., Wohlmuth, H., Asfaw, Z. & Awas, T. The current status of knowledge of herbal medicine and medicinal plants in Fiche, Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 10 (1), 38 (2014).

Athayde, S., Silva-Lugo, J., Schmink, M. & Heckenberger, M. The same, but different: Indigenous knowledge retention, erosion, and innovation in the Brazilian Amazon. Hum. Ecol. 45, 533–544 (2017).

Gomes, C. D. et al. Gender influences on local botanical knowledge: A Northeast Brazil study. Ethnobot. Res. Appl. 28, 1–8 (2024).

Giday, M., Asfaw, Z., Woldu, Z. & Teklehaymanot, T. Medicinal plant knowledge of the bench ethnic group of Ethiopia: An ethnobotanical investigation. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 5, 34 (2009).

Nuro, G. B., Tolossa, K. & Giday, M. Medicinal plants used by oromo community in Kofale District, West-Arsi zone, oromia regional state, Ethiopia. J Exp. Pharmacol. 81–109 (2024).

Kidane, L., Gebremedhin, G. & Beyene, T. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in Ganta Afeshum District, Eastern zone of Tigray, northern Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 14, 64 (2018).

Tefera, B. N. & Kim, Y-D. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in the Hawassa Zuria District, Sidama zone, Southern Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 15, 25 (2019).

Tadesse, D., Lulekal, E. & Masresha, G. Ethnopharmacological study of traditional medicinal plants used by the people in Metema District, Northwestern Ethiopia. Front. Pharmacol. 16, 1535822 (2025).

Teklay, A., Abera, B. & Giday, M. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used in Kilte Awulaelo District, Tigray region of Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 9, 65 (2013).

Tahir, M., Gebremichael, L., Beyene, T. & Van Damme, P. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in Adwa District, central zone of Tigray regional state, northern Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 17, 71 (2021).

Nigussie, S. et al. Practice of traditional medicine and associated factors among residents in Eastern Ethiopia: A community-based cross-sectional study. Front. Public. Health. 10, 915722 (2022).

Abera, B. Medicinal plants used in traditional medicine by oromo people, Ghimbi District, Southwest Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 10, 40 (2014).

Mesfin, F., Demissew, S. & Teklehaymanot, T. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in Wonago Woreda, SNNPR, Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 5, 28 (2009).

Alebie, G. & Mehamed, A. An ethno-botanical study of medicinal plants in Jigjiga town, capital city of Somali regional state of Ethiopia. Int. J. Herb. Med. 4, 168–175 (2016).

Ssenku, J. E. et al. Medicinal plant use, conservation, and the associated traditional knowledge in rural communities in Eastern Uganda. Trop. Med. Health. 50, 39 (2022).

Aziz, M. A. et al. Traditional uses of medicinal plants practiced by the indigenous communities at Mohmand Agency, FATA, Pakistan. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 14, 2 (2018).

Alzobaidi, N., Quasimi, H., Emad, N. A., Alhalmi, A. & Naqvi, M. Bioactive compounds and traditional herbal medicine: Promising approaches for the treatment of dementia. Degener. Neurol. Neuromuscul. Dis. 1–14 (2021).

Agidew, M. G. Phytochemical analysis of some selected traditional medicinal plants in Ethiopia. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 46, 87 (2022).

Teklehaymanot, T. An ethnobotanical survey of medicinal and edible plants of Yalo Woreda in Afar regional state, Ethiopia. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 13, 40 (2017).

Beressa, T. B. et al. Ethnobotanical study of traditional medicinal plants used to treat human ailments in West Shewa community, Oromia, Ethiopia. Front. Pharmacol. 15, 1369480 (2024).

Albaridi, N.A. Antibacterial potency of honey. Int. J. Microbiol. 2019, 2464507 (2019).

Kebede, F. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used to treat human ailment in Guduru District of Oromia Regional State, Ethiopia. J. Pharmacogn. Phytother. (2018).

Omara, T. Plants used in antivenom therapy in rural Kenya: ethnobotany and future perspectives. J. Toxicol. 2020, 1828521 (2020).

Hankiso, M. et al. Ethnoveterinary medicinal plants and their utilization by the people of Soro District, Hadiya zone, southern Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 20, 21 (2024).

Abebe, W. Traditional pharmaceutical practice in Gondar region, northwestern Ethiopia. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1, 11 (1984).

Izzo, A. A., Hoon-Kim, S., Radhakrishnan, R. & Williamson, E. M. A critical approach to evaluating clinical efficacy, adverse events and drug interactions of herbal remedies. Res 30, 691–700 (2016).

Asfaw, A. et al. Medicinal plants used to treat livestock ailments in Ensaro District, North Shewa Zone, Amhara regional state, Ethiopia. BMC Vet. Res. 18, 235 (2022).

Tadesse, D. & Lulekal, Masresha, G. Ethnopharmacological study of traditional medicinal plants used by the people in Metema District, northwestern Ethiopia. Front. Pharmacol. 16 (2025).

Mohamed, K. & Feyissa, T. In vitro propagation of Ximenia americana L. from shoot tip explants: A multipurpose medicinal plant. SINET: Ethiop. J. Sci. 43, 1–10 (2020).

Jima, T. T. & Megersa, M. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used to treat human diseases in Berbere District, Bale Zone of Oromia Regional State, South East Ethiopia. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2018 (2018).

Bahru, T., Kidane, B. & Tolessa, A. Prioritization and selection of high fuelwood producing plant species at Boset District, Central Ethiopia: An ethnobotanical approach. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 17, 51 (2021).

Chekole, G. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used against human ailments in Gubalafto District, Northern Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 13, 55 (2017).

Tadesse, T. & Teka, A. Ethnobotanical study on medicinal plants used by the local communities of Ameya District, Oromia Regional State, Ethiopia. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. (2023). (2023).

Khan, S. M. A new ethnobiological similarity index for the evaluation of novel use reports. Appl Ecol. Environ. Res (2019).

Amsalu, N., Bezie, Y., Fentahun, M., Alemayehu, A. & Amsalu, G. Use and conservation of medicinal plants by indigenous people of Gozamin Wereda, East Gojjam Zone of Amhara region, Ethiopia: An ethnobotanical approach. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2018, 2973513 (2018).

Enyew, A., Asfaw, Z., Kelbessa, E. & Nagappan, R. Ethnobotanical study of traditional medicinal plants in and around Fiche District, Central Ethiopia. Curr. Res. J. Biol. Sci. 6, 154–167 (2014).

Alemneh, D. Ethnobotanical study of ethno-veterinary medicinal plants in YilmanaDensa and quarit districts, West Gojjam Zone, Amhara Region, Ethiopia. Ethnobot Res. Appl. 22, 1–16 (2021).

Akter, Y. et al. A comprehensive review on Linum usitatissimum medicinal plant: Its phytochemistry, pharmacology, and ethnomedicinal uses. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 21, 2801–2834 (2021).

Goyal, A., Sharma, V., Upadhyay, N., Gill, S. & Sihag, M. Flax and flaxseed oil: an ancient medicine & modern functional food. J. Food Sci. Technol. 51, 1633–1653 (2014).

Hassan, H., Ahmadu, A. A. & Hassan, A. S. Analgesic and anti-inflammatory activities of asparagus Africanus root extract. Afr. J. Tradit Complement. Altern. Med. 5, 27–31 (2007).

Khan Marwat, S. et al. Review - Ricinus cmmunis - Ethnomedicinal uses and pharmacological activities. Pak J. Pharm. Sci. 30, 1815–1827 (2017).

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thank the Meketewa community members and key informants for generously sharing their invaluable knowledge of medicinal plants used for human and livestock healthcare. We are grateful to Dr. Getinet Masresha for his expert botanical identification of plant specimens. We also acknowledge the local authorities and community elders for their invaluable support and guidance during data collection.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FK led data collection, analysis, and manuscript writing, while EA supervised fieldwork and plant identification. WM contributed to analyses, interpreting results, and manuscript writing. KG managed data curation. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the Biology Department of Debre Tabor University and permissions from the Meketewa District administrative offices before data collection. All informants were informed about the study’s objectives and provided verbal consent prior to participation.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kassawmar, F., Adamu, E., Misganaw, W. et al. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in Meketewa District, northwestern Ethiopia. Sci Rep 16, 2841 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33571-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-33571-w

- Springer Nature Limited