Abstract

Dietary phytoestrogens have been suggested to provide protection against numerous age-related diseases. However, their effects on biological aging remain unclear. In this study, we cross-sectionally investigated the relationship between urinary phytoestrogen levels and indicators of biological aging using data from 7,981 adults who participated in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2010. Urinary concentrations of six phytoestrogens, including four isoflavones and two enterolignans, were measured using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)-tandem mass spectrometry (MS) or HPLC-atmospheric pressure photoionization-tandem MS, and standardized using urinary creatinine. Three indicators of biological age (BA), namely the Klemera-Doubal method biological age (KDM-BA), phenotypic age (PA), and homeostatic dysregulation (HD), were derived from 12 clinical biomarkers, advanced-BAs were calculated to quantify the differences between individuals’ BAs and chronological age, and individuals with all positive advanced-BAs were defined as accelerated-aging. Weighted linear regression analysis showed that after adjusting for demographic and lifestyle factors and history of chronic diseases, elevated urinary total phytoestrogen and enterolignans were significantly associated with less advanced-KDM, advanced-PA, and advanced-HD, whereas elevated urinary isoflavones was significantly associated with less advanced-KDM and advanced-PA but not with advanced-HD. Weighted logistic regression showed that higher urinary levels of total phytoestrogen (highest Q4 vs. lowest Q1: OR = 0.60, 95%CI: 0.44, 0.80; P-trend = 0.002) and enterolignans (Q4 vs. Q1: OR = 0.59, 95%CI: 0.45, 0.76; P-trend < 0.001) were significantly associated with lower odds of accelerated-aging, but this was not significant for isoflavones (Q4 vs. Q1: OR = 0.78, 95%CI: 0.60, 1.08; P-trend = 0.05). Subgroup analyses showed that negative associations were attenuated in non-overweight/obese participants and current cigarette smokers. In conclusion, higher levels of urinary phytoestrogens are related to markers of slower biological aging, suggesting an anti-aging effect of higher dietary phytoestrogen consumption, which warrants further investigations in longitudinal or interventional settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Aging is a leading risk factor for most of the major chronic diseases and deaths. Rapid population aging has become a major public health burden worldwide1. At the biological level, aging is the result of the accumulation of molecular and cellular damage over time, which leads to a gradual decline in physical and mental functions and an increased risk of diseases and death2. Influenced by a multitude of factors such as genetics, environment, and lifestyle, the process of aging varies significantly among individuals of the same age3,4. Accordingly, biological ages (BAs), which are biomarkers designed to quantify the rate of aging and predict healthspan and lifespan, are more accurate aging indicators than chronological age (CA)5,6, and have been proposed as ideal endpoint measures for assessing the efficacy of interventions intended to slow down the aging process and extend lifespan6. Numerous BA measures have been developed6. Among them, the Klemera-Doubal method biological age (KDM-BA)7, the phenotypic age (PA)8, and the homeostatic dysregulation (HD)9 represent a major category of BAs that are algorithmized based on clinical biomarkers of multiple systems and reflect aging process at whole body level6. These BA measures have been shown to be reliable predictors for age-related diseases, disability, and mortality6,10,11,12,13.

Phytoestrogens are a group of naturally occurring compounds in plants that have a chemical structure similar to that of estrogen. Isoflavones and lignans are the two main classes of phytoestrogens found in foods, such as soybeans, flaxseeds, and legumes. Owing to their structural similarity to human estrogen, phytoestrogens can interact with estrogen receptor and exert estrogenic or anti-estrogenic effects14. Phytoestrogens also possess antioxidative, anti-inflammatory, and pro-autophagic properties14,15, making them potential dietary components with lifespan extension effects by targeting the hallmarks of aging15. Population studies have shown that a higher intake of phytoestrogens is associated with a reduced risk of age-related diseases, including type II diabetes16, hypertension17, coronary heart disease18,19, and some types of cancers20, as well as all-cause mortality21,22,23,24,25 and mortality from cardiovascular disease22 and cancer21,22. However, the relationship between phytoestrogen consumption and biological aging remains unclear.

In a cross-sectional study among Italian adults, higher dietary polyphenol antioxidant content score was associated with delayed biological aging, however, none of polyphenol subclasses, including isoflavones and lignans, were found to be related to biological aging26. The study was limited by the fact that the food frequency questionnaire used to assess dietary intake might not fully capture the intake of these classes of compounds. The lignan or isoflavone content of food may differ substantially depending on factors such as variety, crop season, geographical location, and processing techniques27. Furthermore, the gut microbiota is extensively involved in phytoestrogen metabolism28, and interindividual variations in the gut microbiota may significantly affect the bioavailability of dietary phytoestrogens14. Conjugated isoflavones in food can be converted to equol and O-desmethylangolensin (O-DMA) by gut bacteria, dietary lignans are converted to enterolignans [enterodiol (END) and enterolactone (ENL)] before they can be efficiently absorbed28, and these bacterial metabolites have been shown to be more active than their parental compounds in modulating cell processes29. Therefore, further investigations using biomarkers of bioavailable phytoestrogen exposure are warranted to examine their effects on biological aging.

Circulating phytoestrogens are mainly excreted in the urine via the kidneys, making urinary phytoestrogen concentrations ideal indicators for internal exposure. Urinary phytoestrogens have also been shown to correlate with dietary intake estimated using food questionnaires and have been widely used as biomarkers of dietary intake30,31. In this study, we used urinary phytoestrogen levels as indicators of bioavailable phytoestrogens and examined the relationship between total phytoestrogen, isoflavones, and enterolignans (lignan metabolites by gut microbiota) and three measures of BA based on the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data from 1999 to 2010. We hypothesized that higher urinary phytoestrogen levels would be associated with a less advanced biological age in this population.

Materials and methods

Study design and population

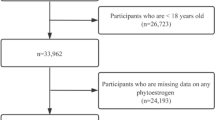

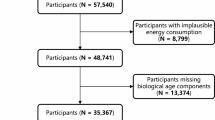

Data were obtained from six cycles of the NHANES (1999–2000, 2001–2002, 2003–2004, 2005–2006, 2007–2008, and 2009–2010) because urinary phytoestrogen concentrations were measured only in these cycles. The NHANES was conducted biannually by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) to assess the health and nutritional status of a representative sample of the non-institutionalized United States population. The survey used a multistage, complex, stratified probability sampling design that oversampled minorities and older adults, thereby providing excellent external validity. The NHANES study protocol was approved by the NCHS Ethics Review Board (protocol #98 − 12, #2005-06, #2011-17, and #2018-01), all participants provided written informed consent, and all procedures were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and other ethical principles. NHANES data were made public by the NCHS for statistical reporting and analysis (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/policy/data-user-agreement.html). The participant selection process used in this study is illustrated in Fig. 1. A total of 62,160 participants enrolled in the NHANES 1999–2010 completed a personal interview and health examination. Urinary samples were collected from 1/3 of the participants aged ≥ 6 years who were randomly selected from the total sample (n = 16,542), with subsample weights calculated to account for the probability of being selected into the subsample and additional nonresponse. Among them, 9,563 participants aged ≥ 20 years with valid urinary phytoestrogen levels were selected for BA calculation. After excluding 1,240 participants with missing biological age components, 8, 323 participants with valid urinary phytoestrogen measurements and BAs were included. After excluding 342 pregnant women to avoid possible modulation of BA by pregnancy, the final study population was 7,981, representing a total of 171,328,305 adults in the US aged ≥ 20 years.

Biological aging

Eleven blood biomarkers (albumin, alkaline phosphatase, C-reactive protein, total cholesterol, creatinine, glycosylated hemoglobin, blood urea nitrogen, uric acid, lymphocyte percentage, mean cell volume, and white blood cell count) and systolic blood pressure were used to construct the BAs. Details on blood collection and biomarker measurements are available on the NHANES website (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm).

Three BA measures, namely KDM-BA, PA, and HD, were calculated in accordance with protocols published by Kwon et al., using the “_nhanes” function of the R package BioAge (http://github.com/dayoonkwon/Bio_Age)12. The KDM-BA algorithm was derived from a series of regressions of each biomarker on CA in a reference population7. The PA algorithm was derived from multivariate analyses of each biomarker on mortality hazard based on a reference population, and the resulting PA reflected the CA of an individual with the same mortality risk in the reference population8. The reference population for KDM-BA and PA estimation was NHANES III nonpregnant participants aged 30–75 years12. HD was computed as the Mahalanobis distance for biomarkers relative to a young and healthy reference population. The individual’s HD value indicated a difference in their physiological status from the reference, which was NHANES III non-pregnant participants aged 20–30 years9,12. As HD had a skewed distribution in the sample, it was log-transformed for further analysis.

Advanced-KDM, advanced-PA, and advanced-HD were used to quantify the variations in biological aging. Advanced-KDM and advanced-PA were generated by subtracting CA from KDM-BA and PA, respectively, and represent the discrepancies between the calculated BAs and CA12. Because the HD algorithm did not incorporate CA information, advanced-HD (age-adjusted HD) was computed from the standardized residuals of the regression of CA on log-transformed HD, which represented the distance an individual’s actual HD deviated from the predicted HD at his age32,33. A positive value of advanced-KDM, advanced-PA, or advanced-HD) indicates accelerated aging and increased risk of disease, disability, and mortality, whereas a negative value indicates a delayed biological aging process and reduced risk of disease, disability, and mortality12.

Because KDM-BA, PA, and HD were differentially associated with CA and an individual could present different biological aging statuses defined by these BA measures, we further categorized participants who were in the status of accelerated aging in all three BA measures (all positive advanced-BAs) as accelerated-aging, otherwise non-accelerated-aging.

Urinary phytoestrogens

Spot urine samples were collected from participants at a mobile examination center, urine vials were processed, and stored under appropriate freezing conditions until they were shipped to laboratories for analysis. After enzymaitc deconjugation of the glucuronidated phytoestrogens, phytoestrogens were than separated from other urine components by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and total concentrations of six phytoestrogens, including four isoflavones [daidzein, O-Desmethylangolensin (O-DMA), equol, and genistein] and two enterolignans [enterodiol (END) and enterolactone (ENL)] were determined by HPLC-tandem mass spectrometry in the survey 1999–2004 and by HPLC atmospheric pressure photoionization-tandem mass spectrometry in the survey 2005–2010 34. The limit of detection for six phytoestrogens ranged from 0.04 ng/mL (END) to 0.4 ng/mL (Daidzein). A crossover study comparing samples analyzed by the two assays showed a high correlation coefficient (r > 0.99), with a regression slope approximately equal to 1 and an intercept close to 0 35. The concentrations of the total phytoestrogens, isoflavones, and enterolignans were obtained by summing the values (in ng/mL) of the individual phytoestrogens. Urinary concentrations of creatinine (in mg/mL) were measured on a Beckman CX3 using a Jaffe rate reaction prior to 2007 and on the Roche ModP using an enzymatic method from 2007 and were adjusted for comparison as recommended36. All concentrations of urinary phytoestrogens were standardized by dividing by creatinine and expressed as ng/mg creatinine37.

Covariates

Covariates, including, sex, ethnicity (non-Hispanic Whites, non-Hispanic Blacks, Mexican Americans, and others), educational level (less than high school graduate, high school graduate, and some college, college graduate, and higher), poverty income ratio (PIR), cigarette smoking (non-smoker, former smoker, and current smoker), alcohol consumption (non-drinker, former drinker, moderate drinker, and heavy drinker), physical activity, Health Eating Index-2015 (HEI-2015), history of chronic diseases, and menopausal status for women, were obtained through questionnaires, examinations, and laboratory tests. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as the body weight divided by the height squared (kg/m2). Participants who smoked fewer than 100 cigarettes during their lifetime were defined as non-smokers, participants who had smoked more than 100 cigarettes and smoked at the time of the interview were considered current smokers, and those who smoked more than 100 cigarettes but had quit smoking for more than 6 months were former smokers. Alcohol drinking status was categorized as non-drinker (less than 12 drinks in a lifetime), former drinkers (more than 12 drinks in a lifetime but no drinking in the past 12 months), moderate drinkers (less than 3 drinks per day for men and 2 drinks per day for women), and heavy drinkers (3 drinks and more for men and 2 drinks and more for women). Daily physical activity levels were calculated based on the time and metabolic equivalent of the task (MET) for each activity. HEI-2015 was calculated based on the dietary interview data using the R package dietaryindex (https://github.com/jamesjiadazhan/dietaryindex)38. Participants who were diagnosed by a doctor as having a high blood pressure, were currently taking antihypertensive medications, or had a systolic blood pressure ≥ 130 mmHg/diastolic blood pressure ≥ 80 mmHg were categorized as having hypertension. Participants who were diagnosed with diabetes by a doctor, were currently taking insulin or diabetes medication, or had an abnormal blood biomarker (HbA1c level ≥ 6·5%, fasting plasma glucose level ≥ 126 mg/dL, or oral glucose tolerance test level ≥ 200 mg/dL) were defined as having diabetes. Participants who were told by a doctor to have high blood lipid levels, were currently taking lipid-lowering medication, or had an abnormal lipid profile (HDL cholesterol < 40 mg/dL, LDL cholesterol ≥ 110 mg/dL, or triglyceride ≥ 150 mg/dL) were categorized as having dyslipidemia. Other medical conditions, including chronic bronchitis, hepatopathy, kidney disease, cardiovascular disease (heart failure, coronary heart disease, angina pectoris, and heart attack), stroke, and cancer were defined based on self-reported diagnoses.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted by accounting for a complex survey design including sample weights, clustering, and stratification34. A specific sample weight for phytoestrogen (laboratory subsample B) was generated from the six 2-year cycles for the complete dataset so that the results are representative of the United States population34. For descriptive analysis, continuous variables were presented as weighted means (standard errors [SEs]), and categorical variables were presented as weighted proportions (SEs) in percentages, except for urinary levels of phytoestrogens, which were expressed as creatinine-adjusted medians (interquartile range [IQR]). The creatinine-adjusted phytoestrogen levels were log-transformed to normalize the distribution in the regression analyses.

Weighted multivariable linear regression models were constructed to examine the association between urinary levels of total phytoestrogens, isoflavones, enterolignans, and individual phytoestrogens and the three measures of advanced-BAs, and linear regression coefficients and 95% confidence intervals (β, 95% CI) were reported. The models were initially adjusted for sex, ethnicity, education level, and PIR (Model 1); further adjusted for cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, physical activity levels, and HEI-2015 (Model 2); and further adjusted for history of chronic medical conditions in the fully adjusted model (Model 3). Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs for accelerated-aging according to urinary phytoestrogen levels (as continuous values or quartile levels) were estimated using weighted logistic regression analysis in the fully adjusted model, and P-trend values were estimated using quartiles as continuous values. To examine the interaction effects between urinary phytoestrogen levels and demographic/lifestyle factors, interaction terms between the factors and phytoestrogen quartiles were generated and fitted to the fully adjusted model. Subgroup analyses were performed to examine whether demographic and lifestyle factors modulate the association between phytoestrogens and biological aging.

For sensitivity analyses, we limited OR estimation to participants without any reported chronic medical conditions to exclude possible effects of these diseases on the biological aging process and to participants whose urinary phytoestrogen levels were between 5% and 95% of the full sample to avoid outlier effects. Finally, we performed a series of OR estimations by excluding one cycle of data each time, to examine the consistency of the associations.

All analyses were performed using the R software (version 4.4.1). A two-sided P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Result

The demographic characteristics, BA, advanced-BA, and urine phytoestrogen levels of the 7,981 participants are shown in Table 1. The weighted mean age was 46.6 years, and weighted proportions for those aged < 55 years and ≥ 55 years were 69.3% and 30.7%, respectively. The weighted proportion of men was 49.5%, and most participants were non-Hispanic whites (72.3%). The median urinary total phytoestrogen level was 0.69 (IQR: 0.32, 1.42) ng/mg creatinine. Among the six phytoestrogens measured in the urine, the levels of enterolignans were much higher than those of isoflavones (median level, enterolignans vs. isoflavones: 0.44 ng/mg creatinine vs. 0.10 ng/mg creatinine); ENL was the most dominant, and O-DMA had the lowest level (Table 1). Significant inter-correlations existed among the phytoestrogens (r ranged from 0.09 to 0.83), except between END and genistein (Table S1). Participants in the higher quartiles of total urinary phytoestrogen had higher urinary concentrations of isoflavones, enterolignans, and all individual phytoestrogens. They tended to be older, had fewer men, more non-Hispanic whites, higher education levels, higher PIR, lower BMI, fewer current smokers and heavy drinkers, lower levels of physical activity, higher HEI-2015 scores, and a higher prevalence of dyslipidemia, CVD, and a history of cancers (Table 1). Meanwhile, participants in the higher quartiles tended to have less advanced-KDM, advanced-PA, and advanced-HD, and had a lower proportion of accelerated-aging (Table 1).

After adjusting for sex, race, education, and PIR (Model 1), urinary levels of total phytoestrogen and enterolignans were significantly and inversely associated with advanced-KDM, advanced-PA, and advanced-HD, which remained consistent after further adjustment for BMI, cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, physical activity levels, HEI-2015 scores (Model 2), and chronic medical conditions (Model 3, fully-adjusted model) (Table 2). In the fully-adjusted model, elevated urinary levels of total phytoestrogen and enterolignans were significantly (all P < 0.001) associated with less advanced-KDM (total phytoestrogen: β = -0.42, 95%CI: -0.55, -0.28; enterolignans: β = -0.32, 95%CI: -0.42, -0.21), advanced-PA (total phytoestrogen: β = -0.33, 95%CI: -0.43, -0.24; enterolignans: β = -0.25, 95%CI: -0.33, -0.17), and advanced-HD (total phytoestrogen: β = -0.04, 95%CI: -0.05, -0.02; enterolignans: β = -0.03, 95%CI: -0.04, -0.02). Elevated urinary isoflavone levels were significantly associated with less advanced-KDM (β = -0.12, 95%CI: -0.21, -0.03; P = 0.007) and advanced-PA (β = -0.12, 95%CI: -0.18, -0.05; P < 0.001) in the fully adjusted models; however, the associations between urinary isoflavone and advanced-HD were not significant in any model (Table 2). When individual phytoestrogens were analyzed, similar negative associations with advanced-BAs were found for most phytoestrogens (Table S2).

Weighted logistic regression analyses were conducted to examine the association between urinary phytoestrogen levels and accelerated-aging after adjusting for covariates (Table 3). As continuous values, total phytoestrogen (OR = 0.83, 95%CI: 0.77, 0.90; P < 0.001), isoflavones (OR = 0.93, 95%CI: 0.88, 1.00; P = 0.04), and enterolignans (OR = 0.88, 95%CI: 0.83, 0.93, P < 0.001) were inversely associated with the odds of accelerated-aging. When compared with the lowest quartiles, significantly lower odds of accelerated-aging were found only for the highest quartiles of total phytoestrogen (Q4 vs. Q1: OR = 0.60, 95%CI: 0.44, 0.80; P = 0.001) and enterolignans (Q4 vs. Q1: OR = 0.59, 95%CI: 0.45, 0.76; P < 0.001), but not for isoflavones (Q4 vs. Q1: OR = 0.78, 95%CI: 0.60, 1.03; P = 0.08), although negative trends were observed for all three indicators of urinary phytoestrogen (total phytoestrogen, P-trend = 0.002; isoflavones, P-trend = 0.05; and enterolignans, P-trend < 0.001).

Subgroup analyses were performed to examine the association between urinary phytoestrogens and accelerated-aging in the different subpopulations (Fig. 2 and Table S3). Similar lowered odds of accelerated-aging by elevated urinary levels of toatal phytoestrofen and enterolignans were observed across sexes, age groups, ethnicities, and alcohol drinking status. However, BMI and cigarette smoking modulated these associations, as the highest levels of urinary phytoestrogen and enterolignans were significantly associated with lower odds of accelerated-aging in overweight/obese individuals and non-current smokers but not in non-overweight/obese people and current smokers (Fig. 2). In contrast, significant trends (P-trend < 0.05) of a negative association between isoflavones and accelerated-aging were found only in women, younger individuals, and ethnicities other than non-Hispanic whites (Fig. 2). Furthermore, significant interaction effects were observed between total phytoestrogen and ethnicity (P-interaction = 0.007) and between isoflavones and age (P-interaction = 0.02).

For sensitivity analyses, associations between accelerated-aging and urinary total phytoestrogen, isoflavones, and enterolignans were examined after excluding participants with possible outliers in phytoestrogen measures and in participants without any chronic medical conditions. Similarly, total phytoestrogen and enterolignans were negatively related to the odds of accelerated-aging (all P-trend < 0.05), while the association between isoflavones and accelerated-aging was insignificant (Table S4). Furthermore, the relationship between accelerated-aging and phytoestrogens remained consistent when any survey cycle was removed from the analyses (Supplementary Figure S1).

Discussion

Although numerous studies have reported that higher dietary phytoestrogen intake is associated with a lower risk of age-related diseases, disease-specific mortality, and total mortality, the effects of phytoestrogens on the aging process are poorly understood. In this cross-sectional study of the representative US adults, we used urinary phytoestrogens as biomarkers for dietary exposure and found that urinary levels of isoflavones, enterolignans, and total phytoestrogens were inversely associated with three measures of advanced biological age. Higher levels of total phytoestrogen and enterolignans were associated with lower odds of accelerated aging, and the associations were consistent across sexes, age groups, and ethnicities but differed by BMI and cigarette smoking. Our results highlight the potential effects of phytoestrogens as anti-aging components in the human diet and suggest the importance of phytoestrogen and phytoestrogen-rich food intake in promoting healthy aging and extending healthspan and lifespan.

KDM-BA, PA, and HD, three BA metrics used in this study belong to the category of composite BA, which measures general biological integrity and systemic aging in whole body levels6. Although derived from the same set of biomarkers, they used different algorithms and predicted biological age based on different references; KDM-BA and PA predict BAs based on CA and mortality of the reference population, respectively, and HD on the physiological status of a young and healthy population11,12. Three BAs were highly correlated, so were advanced-BAs, which quantify the differences between BAs and CA12. An individual can differ in the three BA measures, reflecting different aspects of the aging process. Therefore, we defined an accelerated-aging status, which was accelerated biological aging indicated in all three advanced-BA measures. The consistency in the negative associations between urinary phytoestrogen and the three advanced-BAs, as well as the negative association between urinary phytoestrogen and accelerated-aging, suggests the anti-aging potential of phytoestrogens in the human body. Considering that urinary phytoestrogen levels have been recognized as biomarkers for dietary phytoestrogen consumption30,31, these results suggest that the dietary consumption of phytoestrogens or phytoestrogen-rich foods might delay the aging process. However, it should also be noted that aging is a complicated process involving multiple tissues and systems, and studies using other systemic aging indicators or cellular-level indicators are needed to confirm the effect of phytoestrogens on the aging process.

As two major types of phytoestrogens in the human diet, isoflavones are rich in soybeans, soy products, and other legumes, lignans are widely found in many fiber-rich foods such as fruits, vegetables, cereals, and flaxseeds39,40. Studies have reported various intake levels of dietary isoflavones and lignans across different regions and countries, and populations in Western countries have a higher intake of lignans and a much lower intake of isoflavones than Asian populations40. As biomarkers for dietary exposure, the urinary levels of isoflavones (daidzein, genistein, O-DMA, and equol) were significantly lower than those of enterolignans (END and ENL) in the NHANES population, reflecting the relatively lower consumption of soy products in the United States40. This might explain why urinary enterolignans were more consistently and significantly related to the advanced-BA measures and had a more substantial impact on biological aging than urinary isoflavones. Several studies analyzing NHANES data have also reported more significant associations between urinary enterolignans and other biological indicators, such as blood HDL and triglycerides41, inflammatory markers41, metabolic syndrome42, cardiometabolic risk factors43, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease44. However, the weakly negative associations between isoflavones and biological aging found in this study warrant further investigation among populations with high isoflavone intake.

Logistic regression analyses showed that urinary total phytoestrogen and enterolignans were associated with lower odds of accelerated-aging, which was further supported by a sensitivity analysis that was limited to participants without any chronic medical conditions to exclude the potential deleterious effects of diseases on the aging process. In the subgroup analyses, we found that significant negative associations between total phytoestrogen/enterolignans and accelerated-aging remained consistent across sexes, age groups, and ethnicities. These results suggested that the anti-aging effect is an intrinsic feature of phytoestrogens. In contrast, negative associations became insignificant in current smokers, which was consistent with a previous study examining the relationship between dietary flavonoid intake and biological aging using NHANES data, which also reported that the significant inverse association between dietary flavonoid intake and advanced biological aging was weakened by smoking45. It has been suggested that cigarette smoking accelerates aging by increasing oxidative stress and systemic inflammation46. The attenuated inverse associations suggest a possible antioxidant/anti-inflammatory mechanism of these compounds in combatting the aging process47. At the levels detected in the urine, systemic phytoestrogen levels were not able to counteract cigarette smoking-induced oxidative and inflammatory damage that has detrimental effects on the aging process. In subgroup analyses, we also found significant inverse associations among both heavy and non-heavy drinkers, in overweight/obese but not non-overweight/obese participants, which should be confirmed in population studies and mechanical investigations.

Previous studies have reported that a higher intake of polyphenols26 and flavonoids45, classes of compounds including major phytoestrogens, were associated with the delayed aging process. However, when subclasses were analyzed, neither dietary isoflavones nor lignans were found to be significantly associated with accelerated or deaccelerated aging26. In contrast, our results showed that elevated levels of urinary isoflavones and enterolignans were significantly associated with less advanced biological age. Dietary phytoestrogens undergo extensive metabolism during digestion and absorption, which can be affected by food properties, the food matrix, processing, and gut bacteria40,48. Particularly, metabolites of gut bacteria, such as equol, O-DMA, and enterolignans, have been suggested to be more active than their parental compounds in modulating cellular process14. For example, it was reported that equol, but not its precursors daidzein and genistein, was inversely associated with type 2 diabetes risk in Chinese adults49, and it was more efficient than daidzein for bone formation in growing female rats50. Enterolignans, including END and ENL, are the major forms of dietary lignan that can be efficiently absorbed. Therefore, urinary phytoestrogens, which are directly related to their circulating levels, may be better indicators of internal exposure to these bioactive molecules, and may be more accurate in assessing the health impacts of dietary components.

The mechanisms underlying the potential protective effects of phytoestrogens on aging remain to be investigated. Phytoestrogens may exert estrogenic, antioxidative, and anti-inflammatory effects on aging pathways and modulate aging processes directly or via bacterial metabolites14. Urinary phytoestrogen levels may also act as surrogate markers for better adherence to a healthy diet, which is usually plant-based and has higher contents of phytoestrogens and other health-beneficial components27,51. The possible confounding effect of healthy diets on the association between urinary phytoestrogen levels and biological aging might not be fully controlled by the HEI-2015 scores. Furthermore, higher urinary phytoestrogens may also be indicators of a healthier gut microbiota. Cross-talk between dietary phytoestrogens and gut microbiota may have profound effects on urinary phytoestrogen levels, as healthy gut microbiota facilitates the metabolism and promote the absorption of bioactive metabolites52; dietary phytoestrogens, in the other hand, may promote the development of healthy gut microbiota53, which has been shown to extend lifespan in animal models54.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report relating phytoestrogens to biological aging in a representative sample from the United States. The results were strengthened by the integration of the three BA measures and sensitivity analysis in relatively healthy participants to exclude the possible modulating effect of age-related diseases. This study has several limitations. First, random spot urine samples were used to quantify the phytoestrogen exposure. Temporal variations in urinary phytoestrogen concentrations might not be fully adjusted using urinary creatinine concentrations, although sensitivity analysis excluding potential outliers might partially compensate for this limitation. Second, the cross-sectional design limited the causality inference. Urinary concentrations at one time point might not represent long-term exposure, and the reciprocal causal relationship between accelerated aging and lower urinary phytoestrogen, which might indicate a less healthy diet, could not be excluded. Longitudinal studies are needed to further investigate the effects of phytoestrogens on biological aging and age-related outcomes. Third, because of the high correlation among different phytoestrogens in the urine, we only analyzed the effects of total phytoestrogen, isoflavones, and enterolignans on BAs, and the specific compounds that had the most significant anti-aging effects could not be determined. Fourth, as blood biochemistry-derived BA indicators, KDM-BA, PA, and HD reflect the status of whole-body aging or general biological integrity5, the effect of phytoestrogens on the aging process across multiple systems and at cellular levels could not be determined and should be further investigated using additional BA metrics. Fifth, different types and levels of urinary phytoestrogens exist across populations, owing to differences in dietary intake. The findings from the US population in this study should be further verified in populations with different patterns of phytoestrogen intake, particularly in Asian populations with higher intake of isoflavones. Finally, due to the lack of quantified relationship between urinary phytoestrogen concentrations and dietary intake, the translating interpretation of the findings for dietary recommendations might be limited.

Conclusions

In this cross-sectional study among a representative US population, we showed that elevated levels of urinary phytoestrogens are related to less advanced biological aging. These findings suggest that a higher consumption of phytoestrogen-rich food might slow the aging process and be a feasible approach for promoting health and extending the lifespan.

Data availability

The data of this study were obtained from NHANES which are publicly available at https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/continuousnhanes/default.aspx.

References

World Population Prospects Online Edition. (United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, 2022). (2022).

Lopez-Otin, C., Blasco, M. A., Partridge, L., Serrano, M. & Kroemer, G. The hallmarks of aging. Cell 153, 1194–1217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.039 (2013).

Fitzgerald, K. N., Campbell, T., Makarem, S. & Hodges, R. Potential reversal of biological age in women following an 8-week methylation-supportive diet and lifestyle program: A case series. Aging (Albany NY). 15, 1833–1839. https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.204602 (2023).

Poganik, J. R. et al. Biological age is increased by stress and restored upon recovery. Cell Metab 35, 807–820 e805, (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2023.03.015

Diebel, L. W. M. & Rockwood, K. Determination of Biological Age: geriatric Assessment vs Biological biomarkers. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 23, 104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11912-021-01097-9 (2021).

Lohman, T., Bains, G., Berk, L. & Lohman, E. Predictors of biological age: The implications for wellness and aging research. Gerontol. Geriatr. Med. 7, 23337214211046419. https://doi.org/10.1177/23337214211046419 (2021).

Klemera, P. & Doubal, S. A new approach to the concept and computation of biological age. Mech. Ageing Dev. 127, 240–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mad.2005.10.004 (2006).

Levine, M. E. et al. An epigenetic biomarker of aging for lifespan and healthspan. Aging (Albany NY). 10, 573–591. https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.101414 (2018).

Cohen, A. A. et al. A novel statistical approach shows evidence for multi-system physiological dysregulation during aging. Mech. Ageing Dev. 134, 110–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mad.2013.01.004 (2013).

Belsky, D. W. et al. Eleven telomere, epigenetic clock, and biomarker-composite quantifications of biological aging: do they measure the same thing? Am. J. Epidemiol. 187, 1220–1230. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwx346 (2018).

Bafei, S. E. C. & Shen, C. Biomarkers selection and mathematical modeling in biological age estimation. NPJ Aging. 9, 13. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41514-023-00110-8 (2023).

Kwon, D. & Belsky, D. W. A toolkit for quantification of biological age from blood chemistry and organ function test data: BioAge. Geroscience 43, 2795–2808, (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-021-00480-5

Li, X. et al. Longitudinal trajectories, correlations and mortality associations of nine biological ages across 20-years follow-up. Elife 9 https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.51507 (2020).

Canivenc-Lavier, M. C. & Bennetau-Pelissero, C. Phytoestrogens Health Eff. Nutrients 15, doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15020317 (2023).

Mas-Bargues, C., Borras, C. & Vina, J. Genistein, a tool for geroscience. Mech. Ageing Dev. 204, 111665. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mad.2022.111665 (2022).

Xia, M., Chen, Y., Li, W. & Qian, C. Lignan intake and risk of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes: A meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 74, 501–509. https://doi.org/10.1080/09637486.2023.2220985 (2023).

Godos, J., Bergante, S., Satriano, A., Pluchinotta, F. R. & Marranzano, M. Dietary phytoestrogen intake is inversely associated with hypertension in a cohort of adults living in the mediterranean area. Molecules 23 https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules23020368 (2018).

Ma, L. et al. Isoflavone intake and the risk of coronary heart disease in US men and women: Results from 3 prospective cohort studies. Circulation 141, 1127–1137. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.041306 (2020).

Hu, Y. et al. Lignan intake and risk of coronary heart disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 78, 666–678. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2021.05.049 (2021).

Micek, A. et al. Dietary phytoestrogens and biomarkers of their intake in relation to cancer survival and recurrence: A comprehensive systematic review with meta-analysis. Nutr. Rev. 79, 42–65. https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuaa043 (2020).

Milder, I. E. et al. Intakes of 4 dietary lignans and cause-specific and all-cause mortality in the Zutphen elderly study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 84, 400–405. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/84.1.400 (2006).

Zamora-Ros, R. et al. Dietary flavonoid and lignan intake and mortality in a Spanish cohort. Epidemiology 24, 726–733. https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0b013e31829d5902 (2013).

Katagiri, R. et al. Association of soy and fermented soy product intake with total and cause specific mortality: Prospective cohort study. BMJ 368, m34. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m34 (2020).

Nakamoto, M. et al. Intake of isoflavones reduces the risk of all-cause mortality in middle-aged Japanese. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 75, 1781–1791. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41430-021-00890-w (2021).

Chen, Z. et al. Dietary phytoestrogens and total and cause-specific mortality: Results from 2 prospective cohort studies. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 117, 130–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajcnut.2022.10.019 (2023).

Esposito, S. et al. Dietary polyphenol intake is associated with biological aging, a novel predictor of cardiovascular disease: Cross-sectional findings from the Moli-Sani study. Nutrients 13 https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13051701 (2021).

Lampe, J. W. Isoflavonoid and lignan phytoestrogens as dietary biomarkers. J. Nutr. 133 (Suppl 3), 956S–964S. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/133.3.956S (2003).

Seyed Hameed, A. S., Rawat, P. S., Meng, X. & Liu, W. Biotransformation of dietary phytoestrogens by gut microbes: A review on bidirectional interaction between phytoestrogen metabolism and gut microbiota. Biotechnol. Adv. 43, 107576. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biotechadv.2020.107576 (2020).

Chen, X., Pan, S., Li, F., Xu, X. & Xing, H. Plant-derived bioactive compounds and potential health benefits: Involvement of the gut microbiota and its metabolic activity. Biomolecules 12 https://doi.org/10.3390/biom12121871 (2022).

Lampe, J. W. et al. Urinary isoflavonoid and lignan excretion on a Western diet: Relation to soy, vegetable, and fruit intake. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 8, 699–707 (1999).

Hutchins, A. M., Lampe, J. W., Martini, M. C., Campbell, D. R. & Slavin, J. L. Vegetables, fruits, and legumes: Effect on urinary isoflavonoid phytoestrogen and lignan excretion. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 95, 769–774. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-8223(95)00214-6 (1995).

Lian, F. et al. Effect of vegetable consumption on the association between peripheral leucocyte telomere length and hypertension: A case-control study. BMJ open. 5, e009305. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009305 (2015).

Willett, W. C. Nutritional Epidemiology 2nd edn (Oxford Oxford University, 1998).

Johnson, C. L., Paulose-Ram, R. & Ogden, C. L. National health and nutrition examination survey: Analytic guidelines, 1999–2010. National center for health statistics. Vital Health Stat. 2 2, 1–24 (2013).

CDC. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2007–2008 Data Documentation, Codebook, and Frequencies - Phytoestrogens - Urine (PHYTO_E), (2012). https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Data/Nhanes/Public/2007/DataFiles/PHYTO_E.htm

CDC. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2007–2008 Data Documentation, Codebook, and FrequenciesNational Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2005–2006 Data Documentation, Codebook, and Frequencies - Albumin & Creatinine - Urine (ALB_CR_E), (2009). htmhttps://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/2005–2006/ALB_CR_D.htm

Barr, D. B. et al. Urinary creatinine concentrations in the U.S. population: Implications for urinary biologic monitoring measurements. Environ. Health Perspect. 113, 192–200. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.7337 (2005).

Zhan, J. J. et al. Dietaryindex: a user-friendly and versatile R package for standardizing dietary pattern analysis in epidemiological and clinical studies. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 120, 1165–1174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajcnut.2024.08.021 (2024).

Kuhnle, G. G. et al. Phytoestrogen content of beverages, nuts, seeds, and oils. J. Agric. Food Chem. 56, 7311–7315. https://doi.org/10.1021/jf801534g (2008).

Viggiani, M. T., Polimeno, L., Di Leo, A. & Barone, M. Phytoestrogens: Dietary Intake, Bioavailability, and protective mechanisms against colorectal neoproliferative lesions. Nutrients 11 https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11081709 (2019).

Eichholzer, M. et al. Urinary lignans and inflammatory markers in the US national health and nutrition examination survey (NHANES) 1999–2004 and 2005–2008. Cancer Causes Control. 25, 395–403. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-014-0340-3 (2014).

Struja, T., Richard, A., Linseisen, J., Eichholzer, M. & Rohrmann, S. The association between urinary phytoestrogen excretion and components of the metabolic syndrome in NHANES. Eur. J. Nutr. 53, 1371–1381. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-013-0639-y (2014).

Frankenfeld, C. L. Cardiometabolic risk factors are associated with high urinary enterolactone concentration, independent of urinary enterodiol concentration and dietary fiber intake in adults. J. Nutr. 144, 1445–1453. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.114.190512 (2014).

Xiong, G. et al. Associations of urinary phytoestrogen concentrations with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease among adults. J. Healthc. Eng. 2022 (4912961). https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/4912961 (2022).

Xing, W. et al. Dietary flavonoids intake contributes to delay biological aging process: Analysis from NHANES dataset. J. Transl Med. 21, 492. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-023-04321-1 (2023).

Lu, W. H. Effect of modifiable lifestyle factors on biological aging. JAR Life. 13, 88–92. https://doi.org/10.14283/jarlife.2024.13 (2024).

Patra, S. et al. A review on phytoestrogens: Current status and future direction. Phytother Res. 37, 3097–3120. https://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.7861 (2023).

Stojanov, S. & Kreft, S. Gut microbiota and the metabolism of phytoestrogens. Revista Brasileira De Farmacognosia-Brazilian J. Pharmacognosy. 30, 145–154. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43450-020-00049-x (2020).

Dong, H. L. et al. Urinary equol, but not daidzein and genistein, was inversely associated with the risk of type 2 diabetes in Chinese adults. Eur. J. Nutr. 59, 719–728. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-019-01939-0 (2020).

Tousen, Y., Ishiwata, H., Ishimi, Y., Ikegami, S. & Equol A metabolite of Daidzein, is more efficient than Daidzein for bone formation in growing female rats. Phytother Res. 29, 1349–1354. https://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.5387 (2015).

Wu, X. et al. Correlations of urinary phytoestrogen excretion with lifestyle factors and dietary intakes among middle-aged and elderly Chinese women. Int. J. Mol. Epidemiol. Genet. 3, 18–29 (2012).

Gaya, P., Medina, M., Sanchez-Jimenez, A. & Landete, J. M. Phytoestrogen Metabolism by adult human gut microbiota. Molecules 21 https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules21081034 (2016).

Baldi, S. et al. Interplay between lignans and gut microbiota: Nutritional, functional and methodological aspects. Molecules 28 https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28010343 (2023).

Ling, Z., Liu, X., Cheng, Y., Yan, X. & Wu, S. Gut microbiota and aging. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 62, 3509–3534. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2020.1867054 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to the staff and members of the National Center for Health Statistics at the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) as well as all the the NHANES participants.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Concept and design: JW and FL. Data extraction: JW, MG, YP, YC, and QC. Analysis and interpretation of data: JW, MG, YP, YC, and SH. Drafting of article: JW, QC, and FL. Review and Editing: XY, XX, and XF. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Data for this study were sourced from datasets available to the public with the approval of the NCHS Ethics Review Board (protocol #98 − 12, #2005-06, #2011-17, and #2018-01), and all procedures were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and other ethical principles.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, J., Cao, Q., Gao, M. et al. Elevated urinary phytoestrogens are associated with delayed biological aging: a cross-sectional analysis of NHANES data. Sci Rep 15, 8587 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88872-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88872-x

- Springer Nature Limited

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Urinary phytoestrogen metabolites are associated with a reduced risk of hyperuricemia

Clinical Rheumatology (2026)