Abstract

Background: Patient self-advocacy plays a crucial role in improving cancer patients’ quality of life, but there is no validated instrument to assess this concept among Chinese head and neck cancer patients. This study aimed to cross-culturally translate the Patient Self-Advocacy Scale (PSAS) and evaluate its psychometric properties using classical test theory and item response theory. Methods: The PSAS underwent cross-cultural adaptation based on Brislin’s translation model and a cross-sectional survey of 302 head and neck cancer patients at a tertiary hospital in Tianjin was conducted from November 2023 to August 2024. Classical test theory was used for item analysis and validation of reliability (internal consistency, test-retest reliability) and validity (content validity, construct validity). Item response theory was applied to evaluate model fit, reliability, item difficulty, and measurement invariance. Results: Classical test theory analysis demonstrated good item discrimination with item-total correlations ranging from 0.776 to 0.942 and critical ratios from 13.269 to 33.170 (p < 0.05), as well as good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.942 for the total scale) and test-retest reliability (ICC = 0.840 for the total scale, p < 0.001). I-CVI values ranged from 0.80 to 1.00, with an S-CVI of 0.95. The three-factor model demonstrated good fit (χ2/df = 2.595, RMSEA = 0.090, SRMR = 0.072, CFI = 0.966, IFI = 0.966, TLI = 0.956). Rasch analysis indicated a good model fit and reliability (person/item separation index > 1.5, person/item reliability coefficient > 0.9). The Wright map showed good matching between item difficulty and person ability. Differential item functioning (DIF) analysis revealed no significant differences across gender. Conclusion: The Chinese version of PSAS demonstrates satisfactory psychometric properties among head and neck cancer patients and provides healthcare providers with a tool to assess patients’ self-advocacy, potentially facilitating patient-centered care and self-management in clinical practice and improving patients’ health and quality of life outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Head and neck cancer (HNC), encompassing malignancies in the upper aerodigestive tract1, represents the sixth most common cancer type globally, with GLOBOCAN 2022 data indicating 947,211 annual cases accounting for 4.74% of global cancer incidence2. In China, the HNC burden has shown a consistent increase, with new cases rising from 135,100 in 2015 to 145,600 in 2022, constituting 15.37% of global cases3,4. The therapeutic modalities for HNC encompass chemotherapy, radiotherapy, surgery, and immunotherapy-based approaches, which can be administered either as monotherapy or in various combinations1,5. While advances in contemporary therapeutic modalities have markedly improved five-year survival rates among HNC patients6,7, these improvements have introduced novel challenges regarding patients’ quality of life. Due to the unique anatomical complexity of the head and neck region, therapeutic interventions inevitably impact critical functions, including respiration, deglutition, and verbal communication. HNC survivors frequently experience multiple symptom burdens, including xerostomia, pain, and fatigue, while simultaneously confronting challenges related to altered body image8, compromised intimate relationships9, and occupational reintegration difficulties10. These challenges often precipitate psychological distress, manifesting as anxiety, depression, and suffering11,12. Collectively, these treatment-associated toxicities have profound implications, substantially impacting the quality of life13, diminishing treatment adherence14, and potentially compromising survival outcomes.

Current interventional strategies aimed at enhancing the quality of life among HNC survivors predominantly emphasize external support mechanisms, such as health education and symptom surveillance15,16, while insufficient attention is given to patient autonomy and active engagement17. In contrast, evidence demonstrates that patient-centered care, enhanced participation in medical decision-making, and effective self-management yield superior outcomes in improving cancer survivors’ quality of life compared to singular external support approaches18,19. However, Chinese HNC patients face distinct challenges in implementing these approaches. The disease predominantly affects middle-aged or elderly individuals and those with lower socioeconomic status20, who typically have limited health literacy21, impeding their ability to comprehend medical information and communicate healthcare needs effectively22. Moreover, deeply influenced by Chinese cultural traditions and healthcare systems23,24, these patients typically demonstrate high deference to medical professionals and passively accept medical decisions. Under these circumstances, patients’ limited engagement in their care may render “patient-centered care” superficial or even counterproductive, where increased provider efforts paradoxically result in heightened patient passivity and dependence. Therefore, enhancing HNC patients’ ability to voice for themselves is crucial for optimizing their healthcare outcomes.

Self-advocacy effectively addresses these challenges. It refers to patients’ confidence and ability to protect their interests when facing life-threatening diseases, encompassing skills like information seeking, question asking, expressing preferences, and protecting personal rights25,26,27. Research shows that patients with higher self-advocacy capabilities actively acquire disease knowledge, communicate effectively with healthcare providers, and participate in treatment decisions, improving treatment adherence and satisfaction28,29. Through self-advocacy, patients enhance self-care responsibility, adopt health-promoting behaviors, alleviate symptoms, and reduce psychological distress30,31. It also helps rebuild social roles, increase participation, and reduce isolation32,33.

The Patient Self-Advocacy Scale (PSAS) is one of the important tools for assessing this capability. It was developed by E. Brashers and Stephen M. Haas25 in 1999. Brashers validated the scale’s reliability and validity in samples of AIDS patients and general adults, with a Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.78. The PSAS has demonstrated good applicability among patients in the United States and Iran34,35 but has not been translated into Chinese and validated. Therefore, this study aims to translate the PSAS into Chinese and conduct a psychometric evaluation using Classical Test Theory (CTT) and Item Response Theory (IRT) to provide a reliable instrument for assessing self-advocacy levels among Chinese HNC patients and potentially contributing to the improvement of patients’ quality of life.

Methods

Study design and sample

A cross-sectional study was conducted at the Department of Maxillofacial and Otolaryngological Oncology, Tianjin Medical University Cancer Institute and Hospital from November 2023 to August 2024. The inclusion criteria were: (1) histopathologically diagnosed with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma1 ; (2) clear consciousness with basic reading comprehension and verbal expression abilities sufficient to complete questionnaires; and (3) age ≥ 18 years. The exclusion criteria were: (1) non-primary head and neck cancer; (2) concurrent malignancies at other sites; and (3) psychiatric disorders or cognitive impairment. The exclusion criteria included: (1) voluntary withdrawal during the survey and (2) failure to complete the required survey responses for any reason.

According to Roscoe’s criterion, the sample size should be ten times the total number of items in the questionnaire36,37, with an additional 10% added to account for potential missing data. In this study, the questionnaire consisted of 12 items, resulting in a minimum required sample size of 132. However, considering that confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) requires a sample size greater than 200 38 and that exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and CFA require different samples, a larger sample size was needed. Thus, to ensure more robust results, a total of 302 patients with HNC were recruited, and all collected questionnaires were deemed valid. The sample was randomly divided using a computer-generated sequence into two subsets: EFA (n = 102) and CFA (n = 200), while the complete dataset of 302 participants was utilized for all other analyses including item analysis, reliability testing, and IRT analyses. A total of 20 participants who voluntarily left contact information underwent a remeasurement after a 2-week interval to assess test-retest reliability.

Instruments

Patient information form

A demographic and clinical information form was used to collect data including gender, age, educational level, marital status, employment status, place of residence, and living arrangements. Clinical data included cancer type, disease duration, and treatment modalities.

The PSAS

The measurement instrument was developed by Brashers and Haas25. It consists of three dimensions: increased illness education, increased assertiveness in physician communication, and mindful nonadherence. The scale comprises 12 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale. Total scores range from 12 to 60, with higher scores indicating stronger self-advocacy capabilities. This questionnaire is self-administered by the patients.

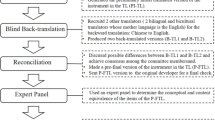

Translation and Cross-cultural adaptation of the PSAS

After obtaining permission from Professor Stephen M. Haas, we conducted the translation and cross-cultural adaptation following Brislin’s guidelines39 (Fig. 1). The majority of participants indicated that the questionnaire had an appropriate number of items, was easy to comprehend, and required 5–10 min to complete. Based on these results, the Chinese version of PSAS (PSAS-C) was finalized.

Data analysis

Participant characteristics

Descriptive statistics were conducted and demographics between EFA and CFA groups were compared through Chi-square and rank-sum tests (p < 0.05) using SPSS 26.0.

CTT-based analysis of psychometric properties

Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics version 26.0 and AMOS version 28.0. The psychometric evaluation included the following aspects: Item discrimination was evaluated through item-total correlation analysis, and items with correlation coefficients below 0.4 were eliminated40. The Critical Ratio method split participants into high-scoring (top 27%) and low-scoring (bottom 27%) groups based on total scores, with independent t-tests comparing groups (p < 0.05)41. For content validity, five experts rated item relevance on a 4-point Likert scale. The Item-level CVI (I-CVI) calculation involved the proportion of experts giving ratings of 3 or 4 per item, while Scale-level CVI (S-CVI) represented the average of all I-CVIs. Acceptable validity thresholds were I-CVI ≥ 0.78 and S-CVI/Ave ≥ 0.90 42,43. Factor analysis appropriateness was assessed through the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure (KMO > 0.6) and Bartlett’s test of sphericity (p < 0.01)44. The PSAS-C structural validity was evaluated using both EFA and CFA. EFA employed Principal Component Analysis with Promax rotation, requiring factor loadings ≥ 0.400 45. CFA used maximum likelihood estimation, with acceptable model fit indices defined as χ2/df < 5, Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) ≤ 0.08, and Incremental Fit Index (IFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), Comparative Fit Index (CFI) ≥ 0.90 43,46. Reliability was evaluated through two approaches: internal consistency using Cronbach’s α (acceptable at ≥ 0.70) and test-retest reliability using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) calculated with a two-way mixed-effects model with absolute agreement definition and single measurement (acceptable at ≥ 0.50)47.

IRT-based analysis of psychometric properties

Model Selection: The Rasch model, as an IRT model, estimates response probability based on a person’s ability and item difficulty parameters on a logit scale. Unlike CTT, these parameters operate independently of other factors48. The Rating Scale Model (RSM)49, an extension of the Rasch model for Likert-type scales, provides parameter invariance, sample-independent item calibration, and item-specific measurement error estimation.

Rasch analysis was performed using Winsteps 3.6.6. The analysis tested structural validity by examining whether the data met the assumptions of unidimensionality and local independence, which was done using a statistical method called Principal Component Analysis of Residuals (PCAR). The first dimension needed to explain > 40% of the total variance, with the first contrast < 15% 50. Local independence was assessed by inter-item residual correlations (values < 0.7 indicating adequacy)51. Model fit adequacy used Outfit and Infit Mean Square values, with 0.50 to 1.50 indicating acceptable fit52, while point-measure correlations between 0.4 and 0.8 indicated acceptable item-dimension relationships. Measurement consistency was evaluated through reliability and separation indices. Person Reliability Index (PRI) and Item Reliability Index (IRI) assessed internal consistency, with values > 0.70 classified as acceptable53. Item Separation Index (ISI) and Person Separation Index (PSI) examined item difficulty hierarchy and respondent classification capacity, with values > 1.5 considered adequate54. Wright maps visualized person abilities and item difficulties distribution on the same logit scale. Differential Item Functioning (DIF) analysis examined item interpretation across demographic variables, including gender, age group, and long-term residence. DIF was considered significant when DIF contrast exceeded 0.5 logits, and the Mantel-Haenszel test showed p < 0.05 55.

Results

Participant characteristics

The study included 302 participants with a mean age of 58.19 ± 8.30 years, comprising 227 males (75.2%) and 75 females (24.8%). The median PSAS-C total score was 34.00 (23.75, 42.00). The demographic characteristics of both the EFA and CFA groups are presented in Table 1. All the variables were comparable between both groups (p > 0.05).

Validity and reliability testing using CTT

Item analysis

Item-total correlations ranged from 0.776 to 0.942. CR values between high-scoring (top 27%) and low-scoring groups (bottom 27%) ranged from 13.269 to 33.170, with significant differences for all items (p < 0.05) (Table 2).

Content validity

The PSAS-C demonstrated item-level content validity index (I-CVI) values ranging from 0.80 to 1.00 and a scale-level content validity index (S-CVI) of 0.95.

Structural validity

The KMO value (0.908) and Bartlett’s test (χ2 =1239.048, p < 0.01) supported factor analysis. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted using principal component analysis as the extraction method with oblique rotation, which identified three factors:: Increased illness education (Items 1–4), Increased assertiveness in physician communication (Items 5–7), and Mindful nonadherence (Items 8–12), with factor loadings ranging from 0.418 to 0.978 (Table 3).

Confirmatory factor analysis of the three-factor model using maximum likelihood estimation showed the following fit indices: χ2/df = 2.595, RMSEA = 0.090, SRMR = 0.072, CFI = 0.966, IFI = 0.966, and TLI = 0.956. Although the RMSEA slightly exceeded 0.08, it remained acceptable (≤ 0.10). The standardized factor loadings for the three-factor model are illustrated in Fig. 2.

Reliability

The Cronbach’s α coefficient of the PSAS-C was 0.942 for the total scale and 0.922, 0.932, and 0.908 for the three dimensions. The two-week test-retest reliability showed an ICC of 0.840 for the total scale and 0.913, 0.703, and 0.815 for the three dimensions (Table 4).

Validity and reliability testing using IRT

Unidimensionality and local independence

The PSAS-C data met two key assumptions of Rasch analysis. Principal component analysis of standardized residuals showed that the first dimension extracted by the Rasch model explained 71.2% of the variance, with the first contrast accounting for 8.1%. Among the 66 item pairs, only Items 3 and 4 showed local dependency, with a correlation of 0.74 (> 0.70). This local dependency was theoretically explicable, as both items assessed patients’ cognitive awareness of their health status.

Rasch model fit

All items except Item 1 (Outfit MNSQ = 1.65, Infit MNSQ = 1.63) showed an excellent fit to the Rasch model. The point-measure correlations ranged from 0.68 to 0.83, indicating good item discrimination (Table 5).

Reliability

The PSAS-C demonstrated an item reliability of 0.99 with a separation index of 12.98, indicating excellent consistency among items. The person reliability was 0.91 with a separation index of 3.16, suggesting the scale could effectively distinguish different levels of respondents.

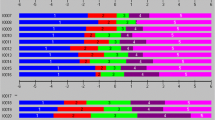

Item measure and map

Wright map showed that item difficulties ranged from − 2 to 2 logits with normal distribution. Person abilities ranged from − 5 to 4 logits. Mean item difficulty and person ability difference was < 1 logit, indicating good person-item matching (Fig. 3).

Wright Person-Item Rasch Map for the PSAS-C (n = 302). The Wright map demonstrates item difficulty and person ability distribution. The right side shows the distribution of items, with the most difficult items at the top and the least difficult at the bottom. The left side represents respondents′measured abilities, from the most capable at the top to the least capable at the bottom. The symbol “#” represents 3 persons, and “.” represents 1–2 persons.

Differential item functioning

DIF analysis across genders, age groups, and long-term residence locations showed no significant differences. The absolute DIF contrast values ranged from 0.000 to 0.330 (p values ranged from 0.1588 to 0.9944) for gender, from 0.000 to 0.510 (p values ranged from 0.1408 to 0.9946) for age groups, and from 0.000 to 0.630 (p values ranged from 0.1320 to 0.9591) for residence locations. No items met the significance criteria (absolute DIF contrast > 0.5 logits and Mantel-Haenszel p < 0.05), indicating consistent item functioning across demographic groups for respondents with equivalent ability levels.

Discussion

HNC patients face complex challenges, and patient self-advocacy provides a new perspective for improving their health outcomes. The application of the PSAS has the potential to realize patient self-management and patient-centered care concepts, thereby enhancing patients’ quality of life. This is the first PSAS validation study conducted in the East Asian region. The study employed both Classical Test Theory (CTT) and Item Response Theory (IRT), which represent two different but complementary measurement frameworks, to ensure robust psychometric properties.

The mean score of PSAS-C was 33.59 ± 12.32, which is lower than that reported in U.S. populations (39.63 ± 6.37)34. This discrepancy may be attributed to two characteristics of the U.S. cohort: a higher proportion of participants with advanced education (50.8% with a bachelor’s degree or above), which may enhance their ability to advocate for themselves, and the inclusion of breast cancer patients (30.8%). Compared to HNC patients, breast cancer patients typically have greater access to support services and educational resources.

Furthermore, in terms of psychometric evaluation results, the PSAS-C demonstrated excellent psychometric properties with high reliability, good content validity, and structural validity. Content validity indices (I-CVI and S-CVI/Ave) met recommended standards42. The scale showed higher internal consistency and test-retest reliability than previous American and Iranian studies34,35. Factor analyses confirmed the original three-factor structure. Before conducting Rasch analysis, we examined whether the scale satisfied unidimensionality and local independence assumptions. Interestingly, the total scale satisfied the unidimensionality assumption, and this difference stems from the two methods’ different theoretical foundations and assumptions rather than indicating problems with the scale’s structural validity and stability. Through Rasch analysis, the PSAS-C showed a good fit except for Item 1’s insufficient fit, which assesses patients’ basic attitudes toward understanding illness and treatment plans. As most patients agree with this view, the item poorly differentiates self-advocacy levels. This misfit is acceptable, given its conceptual importance and other psychometric properties. The scale showed reasonable difficulty distribution and measurement fairness across demographic groups.

Beyond the basic psychometric properties, notable differences emerged in the factor structure: Item 8 (“If my physician prescribes something I don’t understand or agree with, I question it”) shifted from Factor 2 to Factor 3. This change might reflect China’s unique healthcare context. With the progression of healthcare system marketization, patients’ perception of healthcare providers has become discordant, creating conflict between their traditional implicit reverence for medical professionals and providers’ “profit-driven image”23,24. During self-advocacy, patients rarely question medical orders from a professional perspective due to respect for medical authority but demonstrate higher sensitivity and willingness to question when medical costs are involved. This suggests that patients’ motivation to question medical orders stems more from economic considerations than confidence levels, which warrants careful interpretation of Item 8 in practical applications of the scale.

The main limitations of this study include single-hospital recruitment affecting sample representativeness and the absence of a gold standard for self-advocacy assessment in China preventing criterion-related validity analysis. Future studies should address these limitations through multi-center recruitment and establishing criterion validity.

Future research needs to address several key challenges to promote patient self-advocacy. First, assessing healthcare providers’ acceptance of patient self-advocacy and establishing provider-patient trust, as healthcare providers may resist patient self-advocacy due to concerns about consultation time extension and perceived threats to their professional authority25. Second, it is essential to longitudinally evaluate patient self-advocacy across disease trajectories, as patients’ advocacy needs and capabilities vary at different stages of illness. For example, newly diagnosed patients often struggle with medical decision-making due to the complexity of information and emotional distress, whereas patients with advanced or recurrent cancer may encounter additional challenges, such as symptom burden or diminished confidence in their ability to self-advocate31. Third, exploring strategies to balance individual advocacy with family-centered decision-making in the context of traditional values. Chinese culture emphasizes family as the core social unit where members are interdependent and share responsibilities56. Family members serve as key stakeholders with deep involvement in major medical decisions. Although this familial model may lead to lower PSAS scores, it does not necessarily reflect patients’ lack of willingness or capacity for self-advocacy.

Conclusion

The PSAS-C demonstrates good validity, reliability, and objectivity. The scale shows good operability and feasibility with its concise items, simple scoring method, and moderate difficulty level. It accurately measures self-advocacy levels among Chinese HNC patients, providing healthcare providers with a scientific assessment tool.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to privacy concerns and confidentiality agreements with study participants but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CFA:

-

Confirmatory factor analysis

- CFI:

-

Comparative fit index

- CR :

-

Critical ratio

- CTT:

-

Classical test theory

- CVI:

-

Content validity index

- DIF:

-

Differential item functioning

- EFA:

-

Exploratory factor analysis

- HNC:

-

Head and neck cancer

- ICC:

-

Intraclass correlation coefficient

- IFI:

-

Incremental fit index

- IRI:

-

Item reliability index

- IRT:

-

Item response theory

- ISI:

-

Item separation index

- KMO:

-

Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure

- MNSQ:

-

Mean square

- PCAR:

-

Principal component analysis of residuals

- PRI:

-

Person reliability index

- PSAS:

-

Patient Self-Advocacy Scale

- PSAS-C:

-

Chinese Version of the Patient Self-Advocacy Scale

- PSI:

-

Person separation index

- RSM:

-

Rating scale model

- RMSEA:

-

Root mean square error of approximation

- SRMR:

-

Standardized root mean square residual

- S-CVI:

-

Scale-level content validity index

- TLI:

-

Tucker-Lewis index

References

Caudell, J. J. et al. NCCN Guidelines® insights: head and neck cancers, version 1.2022. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Network: JNCCN. 20, 224–234. https://doi.org/10.6004/jnccn.2022.0016 (2022).

Bray, F. et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. Cancer J. Clin. 74, 229–263. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21834 (2024).

Han, B. et al. Cancer incidence and mortality in China, 2022. J. Natl. Cancer Cent. 4, 47–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jncc.2024.01.006 (2024).

Chen, W. et al. Cancer statistics in China, 2015. Cancer J. Clin. 66, 115–132. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21338 (2016).

Bhatia, A. & Burtness, B. Treating head and neck Cancer in the age of immunotherapy: A 2023 update. Drugs 83, 217–248. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-023-01835-2 (2023).

Hashim, D., Genden, E., Posner, M., Hashibe, M. & Boffetta, P. Head and neck cancer prevention: from primary prevention to impact of clinicians on reducing burden. Annals Oncology: Official J. Eur. Soc. Med. Oncol. 30, 744–756. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdz084 (2019).

Baudrexl, J. et al. Sex-specific Real-World 5-year overall survival rates for (Radio)chemotherapy, targeted therapy, and combinations in patients with head and neck Cancer. Anticancer Res. 44, 267–286. https://doi.org/10.21873/anticanres.16810 (2024).

Henry, M. et al. Body image concerns in patients with head and neck cancer: A longitudinal study. Front. Psychol. 13, 816587. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.816587 (2022).

Regeer, J. et al. Sexuality and intimacy after head and neck cancer treatment: an explorative prospective pilot study. Dent. Med. Probl. 59, 323–332. https://doi.org/10.17219/dmp/148156 (2022).

Yu, J., Smith, J., Marwah, R. & Edkins, O. Return to work in patients with head and neck cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Head Neck. 44, 2904–2924. https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.27197 (2022).

Mäkitie, A. A. et al. Psychological factors related to treatment outcomes in head and neck Cancer. Adv. Therapy. 41, 3489–3519. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-024-02945-3 (2024).

Macias, D. et al. Association between Observer-Rated disfigurement and body Image-Related distress among head and neck Cancer survivors. JAMA otolaryngology– Head Neck Surg. 148, 688–689. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoto.2022.0822 (2022).

Carrillo, J. F., Carrillo, L. C., Ramirez-Ortega, M. C., Ochoa-Carrillo, F. J. & Oñate-Ocaña, L. F. The impact of treatment on quality of life of patients with head and neck cancer and its association with prognosis. Eur. J. Surg. Oncology: J. Eur. Soc. Surg. Oncol. Br. Association Surg. Oncol. 42, 1614–1621. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2016.05.037 (2016).

Miller, J. L. & Evers, J. Barriers to adherence to Cancer treatments among head and neck Cancer patients. J. Adv. Practitioner Oncol. 13, 515–523. https://doi.org/10.6004/jadpro.2022.13.5.5 (2022).

Margalit, D. N. et al. Interventions for head and neck cancer survivors: systematic review. Head Neck. 44, 2579–2599. https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.27142 (2022).

Nayak, S. G., George, A., Sharan, K., Nayak, B. S. & Salins, N. Interventions to improve quality of life in patients with head and neck cancers receiving radiation therapy: a scoping review. Supportive Care Cancer: Official J. Multinational Association Supportive Care Cancer. 32, 31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-023-08197-1 (2023).

Crowder, S. L., Najam, N., Sarma, K. P., Fiese, B. H. & Arthur, A. E. Quality of life, coping strategies, and supportive care needs in head and neck cancer survivors: a qualitative study. Supportive Care Cancer: Official J. Multinational Association Supportive Care Cancer. 29, 4349–4356. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05981-1 (2021).

Jovanovic, N., Doyle, P. C. & Theurer, J. A. Supporting patient autonomy in shared decision making for individuals with head and neck Cancer. Am. J. Speech-Language Pathol. 31, 1588–1600. https://doi.org/10.1044/2022_AJSLP-21-00339 (2022).

Elkefi, S. & Asan, O. The impact of Patient-Centered care on Cancer patients’ QOC, Self-Efficacy, and trust towards Doctors: analysis of a National survey. J. Patient Experience. 10, 23743735231151533. https://doi.org/10.1177/23743735231151533 (2023).

Guo, K. et al. Epidemiological trends of head and neck cancer: A population-based study. Biomed. Res. Int. 2021 (1738932). https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/1738932 (2021).

Li, Z., Tian, Y., Gong, Z. & Qian, L. Health literacy and regional heterogeneities in China: A Population-Based study. Front. Public. Health. 9, 603325. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.603325 (2021).

Xiao, L. et al. The effect of health literacy on patient’s perceived shared decision-making among Chinese cancer patients. Psycho-Oncology 31, 70–77. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5777 (2022).

Lyu, Y., Xu, Q. & Liu, J. Exploring the medical decision-making patterns and influencing factors among the general Chinese public: a binary logistic regression analysis. BMC Public. Health. 24, 887. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-18338-8 (2024).

Mi, J., Du, X., Aili, Y., Li, M. & Liu, Y. Unveiling patient trust in physicians across China: insights from a nationwide Cross-Sectional study. Risk Manage. Healthc. Policy. 17, 1039–1052. https://doi.org/10.2147/RMHP.S456585 (2024).

Brashers, D. E., Haas, S. M. & Neidig, J. L. The patient self-advocacy scale: measuring patient involvement in health care decision-making interactions. Health Commun. 11, 97–121. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327027hc1102_1 (1999).

Hagan, T. L. & Donovan, H. S. Self-advocacy and cancer: a concept analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 69, 2348–2359. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.12084 (2013).

Thomas, T. H., Donovan, H. S., Rosenzweig, M. Q., Bender, C. M. & Schenker, Y. A conceptual framework of Self-advocacy in women with Cancer. ANS Adv. Nurs. Sci. 44, E1–E13. https://doi.org/10.1097/ANS.0000000000000342 (2021).

Thomas, T. H., Vetterly, S., Kaselitz, E. B., Doswell, W. & Braxter, B. Self-Advocacy among black women during the perinatal period: prevalence and relationship to patient experiences. Birth (Berkeley Calif). https://doi.org/10.1111/birt.12885 (2024).

Jonikas, J. A. et al. Improving propensity for patient self-advocacy through wellness recovery action planning: results of a randomized controlled trial. Commun. Ment. Health J. 49, 260–269. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-011-9475-9 (2013).

Xi, N. et al. Mediating role of self-advocacy in the correlation between depression and health-related quality of life among elderly patients with diabetes mellitus. Panminerva Med. 66, 332–334. https://doi.org/10.23736/S0031-0808.23.04963-7 (2024).

Thomas, T. H., Taylor, S., Rosenzweig, M., Schenker, Y. & Bender, C. Self-advocacy behaviors and needs in women with advanced cancer: assessment and differences by patient characteristics. Int. J. Behav. Med. 30, 211–220. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-022-10085-7 (2023).

Daniels, J. et al. Building self-advocacy in HIV care: the use of role-play to examine healthcare access for HIV-positive MSM in rural South Africa. Global Health Promotion. 28, 32–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/1757975920974008 (2021).

Fenn, K. & Scior, K. The psychological and social impact of self-advocacy group membership on people with intellectual disabilities: A literature review. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabilities: JARID. 32, 1349–1358. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12638 (2019).

Cj, H. K. Measurement of self-advocacy in cancer patients and survivors. Supp. Care Cancer 16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-008-0442-0 (2008).

Vahdat, S., Hamzehgardeshi, L., Hamzehgardeshi, Z. & Hessam, S. Psychometric properties of the patient Self-Advocacy scale: the Persian version. Iran. J. Med. Sci. 40, 349–355 (2015).

Roscoe, J. T. Fundamental Research Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences. 2d ed. xvii. 483 (illustrations 24 cmHolt) (Rinehart and Winston, 1975).

Subhaktiyasa, P. G. et al. Tri Hita Karana and Organizational Culture in Society 5.0: Effect on Adaptability, Consistency, Involvement, and Mission. Vol. 9. 1–10 (2024).

Chen, Q. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Chinese version of the malocclusion impact scale for early childhood (MIS-EC/C). Health Qual. Life Outcomes. 21, 131. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-023-02213-y (2023).

Jones, L., Phillips, Z. & Jaceldo An adaptation of Brislin’s translation model for cross-cultural research. Nurs. Res. 50, 300–304 (2001).

Kraemer, H. C. Correlation coefficients in medical research: from product moment correlation to the odds ratio. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 15, 525–545. https://doi.org/10.1177/0962280206070650 (2006).

Yang, L. et al. Development and validation of the missed intensive nursing care scale. BMC Nurs. 23, 165. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-024-01805-3 (2024).

Polit, D. F., Beck, C. T. & Owen, S. V. Is the CVI an acceptable indicator of content validity? Appraisal and recommendations. Res. Nurs. Health. 30, 459–467. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.20199 (2007).

Zhang, D. et al. Psychometric properties of the coronavirus anxiety scale based on classical test theory (CTT) and item response theory (IRT) models among Chinese front-line healthcare workers. BMC Psychol. 11, 224. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-023-01251-x (2023).

Thompson, B. & Daniel, L. G. Factor analytic evidence for the construct validity of scores: A historical overview and some guidelines. Educational Psychol. Meas. 56, 197–208 (1996).

Hair, J. F. J., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E. & Tatham, R. L. Mutivariate data analysis. Technometrics 31 (2006).

Hu, L. & Bentler, P. M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 6, 1–55 (1999).

Koo, T. K. & Li, M. Y. A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. J. Chiropr. Med. 15, 155–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcm.2016.02.012 (2016).

Boone, W. J., Staver, J. R. & Yale, M. S. Rasch Analysis in the Human Sciences (Springer Netherlands, 2014).

Andrich, D. A rating formulation for ordered response categories. Psychometrika 43, 561–573. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02293814 (1978).

Embretson, S. E. & Reise, S. P. Item Response Theory for Psychologists (Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2000)

González-de Paz, L. et al. A Rasch analysis of patients’ opinions of primary health care professionals’ ethical behaviour with respect to communication issues. Fam. Pract. 32, 237–243. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmu073 (2015).

Bond, T. G. & Fox, C. M. Applying the Rasch Model 0 edn (Psychology, 2013).

Lau, S. C. L., Baum, C. M., Connor, L. T. & Chang, C. H. Psychometric properties of the center for epidemiologic studies depression (CES-D) scale in stroke survivors. Top. Stroke Rehabil. 30, 253–262. https://doi.org/10.1080/10749357.2022.2026280 (2023).

Lee, E. H., Lee, Y. W. & Kang, H. J. Psychometric properties of the revised diabetes knowledge test using Rasch analysis. Patient Educ. Couns. 105, 851–857. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2021.07.013 (2022).

Rouquette, A., Hardouin, J. B., Vanhaesebrouck, A., Sébille, V. & Coste, J. Differential item functioning (DIF) in composite health measurement scale: recommendations for characterizing DIF with meaningful consequences within the Rasch model framework. PloS One. 14, e0215073. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0215073 (2019).

Meng, M., Li, X., Zhao, J. & Hao, Y. When Western concept Meets Eastern culture: exploring the impact of confucianism on shared decision-making in China. Asia-Pacific J. Oncol. Nurs. 11, 100586. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apjon.2024.100586 (2024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BS made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work, and supervised the study. JC and JW contributed to the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, and drafted the work. AY contributed to the acquisition and analysis of data. JC contributed to the design of the work and supervision. ZZ substantively revised the work. All authors approved the submitted version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tianjin Medical University. Reporting of data was based on the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before conducting the cross-sectional survey.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cui, J., Wang, J., Yue, A. et al. Psychometric evaluation of the Chinese version of the Patient Self-Advocacy Scale using classical test theory and item response theory. Sci Rep 15, 6871 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91129-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-91129-2

- Springer Nature Limited