Abstract

Two-dimensional topological semimetals are typically characterized by the vorticity of gapless points, and can be classified according to the band representations. However, the topological properties involving the distribution of the Berry curvature in the entire Brillouin zone are often overlooked. In this study, we investigate a two-band two-dimensional topological semimetal protected by C4zT magnetic symmetry, exhibiting a two-fold band degeneracy at the Γ(0, 0) and M(π, π) points. Due to the presence of C4zT symmetry, the Brillouin zone is divided into two patches characterized by half-quantized Berry curvature fluxes with opposite signs. In multi-band case, the half-quantization deviates, indicating the fragile nature. The semimetal presents counter-propagating half-edge channels, accompanied by power-law decaying and oscillating edge currents. The band topology leads to unconventional Landau levels featuring anisotropic edge modes. Each massless Dirac cone, associated with the half-quantized Berry curvature flux, exhibits an integer quantum Hall conductance. Additionally, we calculate the local orbital magnetization with open boundary conditions in both the x and y directions. This reveals isolated magnetization islands, highlighting an experimentally observable magnetic phenomenon in this topological semimetal.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The field of two-dimensional semimetals has flourished following the successful realization of graphene1,2, which hosts band degeneracy at K and K’ points with linear dispersion. Alongside the rapidly developing field of topological quantum materials, various two-dimensional semimetals have been discovered, including Weyl semimetals3,4,5,6,7,8,9, Dirac semimetals10,11,12,13,14,15, double Weyl semimetals16,17, and triply degenerate semimetals18,19. In recent years, topological quantum chemistry has been developed which can help us well classify and rapidly search the semimetal materials20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27. These semimetals exhibit a wealth of intriguing properties2,28,29,30,31, such as ultrahigh mobility, unconventional Landau levels, magneto-optical response, and weak anti-localization. In these studies, the topological nature of the semimetals is characterized by vorticity - the Berry phase around the degeneracy point - while disregarding the high-energy spectrum away from the degeneracy point.

Considering the gauge field of the entire Brillouin zone (BZ) leads to important and interesting physics. Recent findings have shown that a semimetal featuring a single massless Dirac cone exhibits a parity anomaly32,33,34,35, characterized by the half-quantized Hall conductance obtained through integrating the Berry curvature of occupied states across the complete BZ. In contrast to the single massive Dirac cone36,37,38,39,40, which also exhibits half-quantized Hall conductance but is not accessible in lattice materials, the two-dimensional semimetal with a single massless Dirac cone can be synthesized in real materials41,42,43,44,45,46,47 to realize the parity anomaly in condensed matter. This half-quantized Hall conductance is protected by the emergent time-reversal symmetry near the Fermi surface34, rather than the global crystalline symmetries. This raises an interesting question: whether there exists a crystalline symmetry-protected two-dimensional semimetal that hosts nontrivial topological properties and physical phenomena when considering the whole BZ.

In this manuscript, we propose a class of two-dimensional topological semimetals that harbor two massless Dirac cones at high-symmetry points, protected by the C4zT magnetic symmetry. The Berry curvature distribution in the BZ satisfies the C4zT symmetry, leading to a partitioning of the BZ into two patches with half-quantized Berry curvature fluxes exhibiting opposite signs. The half-quantization is robust for the general multi-band case as long as the two bands near the Fermi energy are well separated from other bands, reflecting the fragile topology of the half-quantized Berry curvature flux. The band topology gives rise to counter-propagating half channels along the edge. Upon introducing a nearest neighbor hopping term and subsequent separation of the two massless Dirac points in energy, an emergence of power-law decaying edge current is observed. In the presence of a magnetic field, each cone associates with the half-quantized Berry curvature flux and contributes to integer quantum Hall transport, depending on the direction of the open boundary. This demonstrates a significant distinction from graphene. Interestingly, we find that the zero Hall conductivity plateau exhibits an anisotropic edge conducting channel, which can serve as a magnetically controlled switch for electronic conduction. Another effect of the band topology is the C4zT-respecting pattern of orbital magnetization islands in a square sample, providing insight into macroscopic magnetic phenomena beyond those induced by spin correlations.

Results

Model and edge effect

The C4zT symmetry has been studied in higher-order topological insulators and superconductors48,49,50. A Z4 invariant has also been proposed in the insulator phase51. On the contrary, we concentrate on the C4zT symmetry preserved topological semimetal phase in this paper. First, we construct a two-dimensional, two-band model that violates time-reversal symmetry (denoted as T) and breaks the out-of-plane four-fold rotation symmetry (denoted by C4z). However, this model preserves the combined magnetic symmetry of C4zT as well as the two-fold rotation symmetry C2z, where C2z is the square of C4zT and given by \({({C}_{4z}T)}^{2}\). In a spin-one-half system, the operation \({C}_{2z}^{2}\) is defined such that \({C}_{2z}^{2}=-1\). At the high-symmetry points in the Brillouin zone, specifically at Γ(0, 0) and M(π, π), the eigenvalues are ± i. These eigenvalues are interchanged when subjected to the magnetic symmetry operation C4zT. As a direct consequence of this symmetry, a two-fold degeneracy arises at both the Γ and M points. The simplest form of the Hamiltonian that captures this physics, written in momentum space, is as follows:

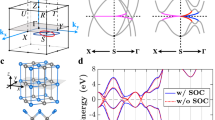

where the Pauli matrices are denoted by σi (for i = x, y, z), representing the spin space, and αz and α∥ are the spin-orbital coupling parameters. The symmetry operators are defined as \({C}_{4z}T={e}^{-i\frac{\pi }{4}{\sigma }_{z}}i{\sigma }_{y}K\) and \({C}_{2z}={\left({C}_{4z}T\right)}^{2}=i{\sigma }_{z}\). The energy spectra of the model are given by \({E}_{\pm }^{2}=4{\alpha }_{z}^{2}{\left(\cos {k}_{x}-\cos {k}_{y}\right)}^{2}+4{\alpha }_{\parallel }^{2}\left({\sin }^{2}{k}_{x}+{\sin }^{2}{k}_{y}\right)\), which are gapless at the high-symmetry points Γ and M. In Fig. 1a, the energy spectra are illustrated with the parameters αz/α∥ = 0.3. Unlike graphene, which features band crossings at the K and \({K}^{{\prime} }\) valleys, the band crossings in our model occur at Γ and M. The gapless Dirac cone at Γ is described by the effective Hamiltonian (see Methods for detail)

where σ± = (σx ± iσy)/2 and v = αz/2 here. The cone at M is described by −Heff(k). This form of low-energy model is enforced by C4zT symmetry, and the σz term makes it distinct from conventional Dirac fermions, such as those in graphene, and topological insulator surface states. The Berry curvature thus is nonzero in the Brillouin zone (BZ) and results in the nontrivial edge effects, as we will calculate and show in the following. Integrating the Berry curvature over the BZ yields the Hall conductance, which, however, vanishes due to the C4zT symmetry.

a Bandstructure of the topological semimetal as described by Eq. (1), with αz = 0.3α∥. Inevitable band crossings are observed at the high-symmetry points: Γ (kx = 0, ky = 0) and M (kx = π, ky = π). b Distribution of Berry curvature in the momentum space, showing the Brillouin zone (BZ) partitioned into two distinct patches with opposite signs of half-quantized Berry curvature flux. X0 and Y0 are momentum points related by C4zT. There must be a Berry curvature vanishing point on the line connecting them. Hence, when X0 and Y0 are moving on the black solid line, one can obtain a Berry curvature vanishing curve connecting Γ and M. c Deviation of the Berry curvature flux from \(\pm \frac{1}{2}\) within each patch, computed using a Nk × Nk mesh in the BZ. d Illustrative mapping of the semi-Bloch sphere for each region, where arrows indicate the gauge field arising from a monopole encased by the Bloch sphere. The top and bottom maps correspond to patches with \({C}_{+}=\frac{1}{2}\) and \({C}_{-}=-\frac{1}{2}\), respectively.

Notably, the inversion of the Berry curvature imposed by the C4zT symmetry leads to the existence of a boundary where the Berry curvature is zero. This can be understood in the following manner, as illustrated in the top right corner of Fig. 1(b). The momentum on the high-symmetry line Γ−X can be represented by X0 = (κ, 0), without loss of generality we can assume Ωn(X0) ≠ 0. For a system possessing C4zT symmetry, we have the relation SH(k)S−1 = H(Dk), where \(S=U{{\mathcal{K}}}\) represents the matrix form of C4zT symmetry in the inner space, with U as a unitary matrix and \({{\mathcal{K}}}\) as the complex conjugation operator, Dk is the transformed wave vector k under C4zT. For an eigen wavefunction \(\left| {u}_{n}({{\boldsymbol{k}}})\right\rangle\), where the Hamiltonian H(k) acts as \(H({{\boldsymbol{k}}})\left| {\psi }_{n}({{\boldsymbol{k}}})\right\rangle ={E}_{n}({{\boldsymbol{k}}})\left| {\psi }_{n}({{\boldsymbol{k}}})\right\rangle\), the eigenstates at k and − C4zk are related by the symmetry operation \(S\left| {\psi }_{n}({{\bf{k}}})\right\rangle ={e}^{i{\phi }_{n}({{\bf{k}}})}\left| \psi (D{{\bf{k}}})\right\rangle\). This relation allows us to demonstrate that Ωn(X0) = −Ωn(Y0) with Y0 = DX0 = (0, κ), highlighting the impact of the C4zT symmetry. Specifically, the momentum X0 on the high-symmetry line Γ−X is transformed to Y0 on the high-symmetry line Γ−Y, with the sign of the Berry curvature reversed. Notably, under C4zT, X→Y and Ωn(X) = −Ωn(Y). In the Brillouin zone, the Berry curvature is a continuous function. According to the Intermediate Value Theorem, there must be at least one point along the curve connecting X0 and Y0 where the Berry curvature equals zero. By moving X0 from Γ to X to M (the solid line in Fig. 1b), we identify a series of points that form a Berry curvature vanishing line, \({{{\mathcal{C}}}}_{\Gamma {{\bf{M}}}}\), connecting Γ and M (the dashed line). Furthermore, considering \({{{\mathcal{C}}}}_{\Gamma {{\bf{M}}}}\) along with its transformations \(D{{{\mathcal{C}}}}_{\Gamma {{\bf{M}}}}\), \({D}^{2}{{{\mathcal{C}}}}_{\Gamma {{\bf{M}}}},{D}^{-1}{{{\mathcal{C}}}}_{\Gamma {{\bf{M}}}}\) divides the Brillouin zone into two distinct patches as depicted in Fig. 1b, with the Berry curvature flux C± respectively. In the model described by Eq. (1), this boundary corresponds to the high-symmetry lines M110 and M1−10, which exhibit mirror symmetry. It is important to mention that mirror symmetry is not generally necessary for the division of the BZ. The Berry curvature flux is integrated as follows:

where the matrix element \({[{v}_{i}]}_{nm}=\langle {\psi }_{n}(k)| {\partial }_{{k}_{i}}H| {\psi }_{m}(k)\rangle\) represents the velocity operator, and \(\left| {\psi }_{m}(k)\right\rangle\) is the Bloch state. The patches with positive and negative Berry curvature are labeled as R+ and R−, respectively. It has been found that the Chern numbers within these patches are \({C}_{\pm }=\pm \frac{1}{2}\), which we refer to as half-quantized Berry curvature flux. The sum of these Chern numbers results in a vanishing total Chern number C = C+ + C− = 0, while their difference yields an integer C+ − C− = 1. In Fig. 1c, we numerically demonstrate that the precision of half-quantization improves with an increased density of the k-mesh in momentum space. This finding highlights that the C4zT symmetry-protected semimetal exhibits an unconventional band topology, distinct from other two-dimensional semimetals.

The half-quantization of the Berry curvature flux is associated with the vanishing of Berry curvature at the boundaries of the patches, as discussed in ref. 32. To analyze the topology of each region independently, singularities can be removed by excluding the Dirac point. The Hamiltonian in Eq. (1) is expressed as d(k) ⋅ σ. Consequently, the vector d(k) in each region manifests a mapping from the disk (kx, ky) to the Bloch sphere, defined by the equation \({\hat{d}}_{x}^{2}+{\hat{d}}_{y}^{2}+{\hat{d}}_{z}^{2}=1\), where \(\hat{d}={{\bf{d}}}/| {{\bf{d}}}|\). The Berry curvature is given by \(\Omega (k)={\sum }_{i,j}{\epsilon }^{ij}\hat{d}\cdot ({\partial }_{{k}_{i}}\hat{d}\times {\partial }_{{k}_{j}}\hat{d})\). At the boundary, the vanishing of Berry curvature, i.e., dz = 0, implies that the mapping on the boundary is confined to the equator of the Bloch sphere, as illustrated in Fig. 1d. This results in the winding number for this region on the Bloch sphere being half-quantized: \(W=\frac{1}{8\pi }\int\,{d}^{2}k\,{\epsilon }^{ij}\hat{d}\cdot ({\partial }_{{k}_{i}}\hat{d}\times {\partial }_{{k}_{j}}\hat{d})=N/2\), where N is an integer, and \(\hat{d}\) is a unit vector representing the spin texture, as discussed in52. This leads to the half-quantized Berry curvature flux within the two patches. In Methods, we also prove such half-quantization by integrating the Berry curvature of low low-energy effective model. It manifests that the half-quantized Berry curvature flux is a universal property of the C4zT protected topological semimetal.

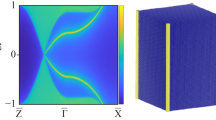

The interplay between the massless Dirac cone and the half-quantized Berry curvature flux may lead to intriguing boundary phenomena. Figure 2(a) illustrates that the edge’s projected Brillouin zone (BZ) accommodates a pair of massless Dirac cones, alongside a pair of massive Dirac cones with opposite masses. This arrangement gives rise to counter-propagating conductive channels at the edge, as depicted in Fig. 2b, c. In the construction of the ribbon sample, both the y-direction (Fig. 2b) and x-direction (Fig. 2c) with width L are considered, and the local density of states (LDOS) near the edge is computed. Due to C4zT symmetry, the results are analogous, prompting the focus on Fig. 2c, which exposes the right and left propagating conductive channels near the kx = 0 and π valleys, respectively. This behavior indicates the existence of a valley-resolved edge current in the ribbon. We define the valley edge current as

where 〈vx〉 is the expectation value of the velocity operator \({v}_{x}=\frac{\partial {H}_{0}({k}_{x})}{\partial {k}_{x}}\), and VΓ,M denotes the integration taken over the vicinity of kx = 0 and π valleys, respectively, with a momentum cutoff kc. In Fig. 2(d), we showcase the valley edge current’s dependence on the chemical potential μ, and the derivative \(\partial {J}_{edge}^{V}/\partial \mu\) which is quantized to be one-half in units of e2/h. The result underscores the presence of a half-edge counter-propagating conducting channel and elucidates that under an external electric field along the x-direction, electrons from the two valleys will transform into each other.

a Projection of the massless and massive Dirac cones onto the x and y boundaries, with yellow indicating patches of positive Berry curvature and blue representing negative Berry curvature. b Local density of states (LDOS) near the x = L edge, where brighter colors highlight the presence of net conducting channels. c LDOS in the vicinity of the y = 0 edge. d Variation of the valley edge current \({J}_{{{\rm{edge}}}}^{V}(\mu )\), shown with blue circles (the red line below is the fitting line of the numerical results), and its derivative \(\partial {J}_{{{\rm{edge}}}}^{V}/\partial \mu\), depicted by the yellow line, as a function of the chemical potential μ. The momentum cutoff kc = 0.15 is taken in the calculation of the valley edge current.

The equilibrium current on the ribbon vanishes everywhere due to the counteraction between the counter-propagating channels. However, we can introduce the nearest neighbor hopping term to energetically offset the Dirac cones:

where σ0 is the two-dimensional identity matrix. This term does not break the magnetic symmetry C4zT, and the enforced band crossing remains intact. Considering a ribbon structure with 0 < y < Ly, we investigate the equilibrium electron current distribution in this model. Figure 3(a) exhibits the LDOS near the y = 0 edge, where the Dirac cones at kx = 0 and π are shifted to E = 4t and − 4t, respectively. The current along the x-axis Jx(y) is computed as:

where \(\left| {\psi }_{n,{k}_{x}}(y)\right\rangle\) is the eigenstate of \(H={H}_{0}+{H}^{{\prime} }\) with the energy \({\epsilon }_{n,{k}_{x}}\), and vx = ∂H(kx)/∂kx. The results, illustrated in Fig. 3(b) with blue circles, demonstrate that the current becomes nonzero and oscillates with y when t ≠ 0. The integral of the edge current Jx(y) along the half-length of the system, from y = 0 to \(y=\frac{L}{2}\), given by \(\int_{0}^{\frac{L}{2}}{J}_{x}(y)\,dy\), is zero. This result is in agreement with the total Chern number of the system being zero. The spatial dependence of the current can be analytically captured by the expression \({J}_{F}={J}_{\Gamma }^{U}+{J}_{\Gamma }^{D}+{J}_{M}^{U}+{J}_{M}^{D}\) with

where \({E}_{F}^{\Gamma }=\mu -4t\) and \({E}_{F}^{M}=\mu +4t\) denote the effective Fermi levels for the Dirac cones at the Γ and M points, respectively. yU/D represents the position of the upper edge yU = 0 and lower edge yD = Ly of the ribbon. Y0(z) is the zeroth-order second kind Bessel function. The fitting results, shown in Fig. 3b with yellow lines, align well with the numerical data. Using the asymptotic form of the Bessel function \({Y}_{0}(z)=\sqrt{\frac{2}{\pi z}}\sin \left(z-\frac{\pi }{4}\right)\) for large z, it is revealed that the current decays from the edge as \({J}_{x}(y)\propto {\sum }_{\Gamma /M}{y}^{-3/2}\frac{| {E}_{F}^{\Gamma /M}| }{2}\cos \left(\left| \frac{{E}_{F}^{\Gamma /M}}{{\alpha }_{| | }}\right| y-\frac{3\pi }{4}\right)\). The oscillatory behavior is the result of two superimposed oscillations with wavelengths \(2\pi \left| \frac{{\alpha }_{| | }}{{E}_{F}^{M}}\right|\) and \(2\pi \left| \frac{{\alpha }_{| | }}{{E}_{F}^{\Gamma }}\right|\), respectively, corresponding to the edge current behaviors in parity anomaly semimetal33. Our previous work highlighted the fingerprint of a parity anomaly semimetal, characterized by the power-law decay of the equilibrium current from the edge as ~y−3/2. In the current model, we can conclude that the equilibrium current distribution Jx(y) away from the edge is a superposition of the behaviors from two parity anomaly semimetals with corresponding effective Fermi levels \({E}_{F}^{\Gamma }\) and \({E}_{F}^{M}\).

a LDOS for the ribbon near the y = 0 edge, depicting the energy split of gapless Dirac cones at Γ and M points with t = 0.1α∥. b Current density distribution Jx(y) across the ribbon for varying parameters t/α∥ = 0.1, 0.2 and μ/α∥ = 0, 0.1. Numerical calculations are represented by blue circles, while the analytical fits using Eq. (7) are shown with yellow lines.

Landau levels

The influence of half-quantized Berry curvature flux on the Landau levels is significant in the context of an external magnetic field. For context, we first review the Landau levels in graphene, characterized by two gapless Dirac cones with negligible Berry curvature. In the presence of a magnetic field B, the Landau-level energies for graphene are given by \({E}_{n}=\,{\mbox{sgn}}\,(n)\sqrt{2e\hslash {v}_{F}^{2}| n| B}\) where n = 0, ±1, ± 2, … denotes the Landau-level index2. The zeroth Landau level is shared by both Dirac cones, and the total Hall conductance is quantized as (2m + 1)e2/h. Thus, the average Hall conductance contributed by each Dirac cone is (2m + 1)e2/2h. With open boundary conditions, the corresponding chiral edge states can be visualized as conduits for Hall current. The zeroth Landau level in graphene is special because it is precisely at the Dirac point and is shared between the K and \({K}^{{\prime} }\) valleys. This valley degeneracy means that the edge states associated with the zeroth Landau level are not valley-polarized; they have contributions from both valleys.

Conversely, in a C4zT semimetal subjected to a magnetic field, the Dirac cone affected by the half-quantized Berry curvature flux manifests an integer quantum Hall conductance. This unique property enables the resolution of edge states by valley, a feature absent in graphene. In Fig. 4(a–c), we calculate the Landau levels with open boundary conditions along the \(\hat{y}\) axis and periodic conditions along the \(\hat{x}\) axis. Fig. 4(e, f) presents the results with open boundary conditions along the \(\hat{x}\) axis and periodic along the \(\hat{y}\) axis. The magnetic field is oriented along the \(\hat{z}\) axis, with a vector potential \(\overrightarrow{A}=B(-y,0,0)\).

a–c Landau-level spectra for a ribbon oriented along the \(\hat{x}\) direction and d–f for a ribbon oriented along the \(\hat{y}\) direction, with parameters set as αz = 0.3α∥ and eB/ℏ = 0.01α∥. a Sketch of the ribbon along the \(\hat{x}\) direction. b Landau levels at t = 0, exhibiting Hall conductivity plateaus at ±1, ± 3, ⋯ . Colors denote the expectation of the location of states, with blue and yellow circles indicating edge states localized at the y = 0 and Ly boundaries, respectively. c Landau levels at t = 0.02α∥, showing Hall conductivity plateaus at 0, ±1, ±2, ⋯ , and the absence of edge states, implying \({N}_{x}^{V}=0\) in the zero Hall plateau. d Sketch of the ribbon the ribbon along the \(\hat{y}\) direction, showing a pair of edge states (blue and red arrows) on each boundary flowing in oppositedirection. e Landau levels at t = 0, with Hall conductivity plateaus at ±1, ±3, ⋯ . Colors indicate the expected location of states, with blue and yellow circles marking edge states on the x = 0 and Lx boundaries, respectively. f The emergence of a pair of edge states at each boundary flowing in opposite directions, denoted as \({N}_{y}^{V}=1\), as illustrated in d.

Incorporating the Peierls substitution, the Hamiltonian becomes \({H}_{0}({k}_{x}+\frac{e}{\hslash }By,-i{\partial }_{y})\). Numerical calculations for eB/ℏ = 0.01α∣∣ with t = 0 are depicted in Fig. 4(b), where the Landau levels and edge states from both Dirac cones are evident. We observe that the bulk Landau levels are flat and exhibit no dispersion with

Landau levels bend upwards or downwards as the guiding center position approaches the edge of the sample, forming the edge states. The bending direction of the zeroth Landau level is determined by the chirality of the massless Dirac fermions at the Γ and M points, as well as which pair of time-reversal invariant momenta (TRIM) from the two-dimensional Brillouin zone are projected onto the same TRIM point at the edge. The edge states localized at the y = 0 boundary are marked in blue, while those at the y = Ly boundary are shown in yellow. The results in Fig. 4e correspond to the scenario with open boundaries along the \(\hat{x}\) axis. Notably, in Fig. 4b, the zeroth Landau-level dispersions associated with the Dirac points at Γ and M bend upwards and downwards, respectively, whereas in Fig. 4e, they exhibit the opposite behavior, underscoring the anisotropic nature of the zeroth Landau level. When the chemical potential lies between the n = 0 and n = 1 Landau levels, the Hall conductance is quantized at +1. According to the boundary-bulk correspondence principle, this quantized Hall conductance indicates the existence of chiral edge states in systems with open boundary conditions. However, the specific edge state manifestation can differ based on the termination: for instance, the edge state along the \(\hat{y}\) terminal may originate from the Dirac cone at point Γ, while the edge state along the \(\hat{x}\) terminal may be linked to the Dirac cone at point M. Consider the Dirac cone at point Γ as an example. When the ribbon is oriented along the \(\hat{x}\) direction, it is projected onto the same point as the X = (π, 0) point, which possesses a topological number of C+ = +1/2. Conversely, when the ribbon extends along the \(\hat{y}\) direction, the projection aligns with the Y = (0, π) point, associated with a topological number of C− = −1/2. As a result, the edge states of the zeroth Landau level display opposite bending directions for different terminations. In the case of a particular termination, the zeroth Landau level, as well as its associated forward and backward-propagating edge states, are exclusive to a single valley. This differs markedly from the situation in a zigzag-edged graphene ribbon, where the zeroth Landau level is shared between the two Dirac cones with the forward-propagating edge state originating from one valley and the backward-propagating edge state from the other.

Introduction of the perturbation \({H}^{{\prime} }\) lifts the degeneracy of the two gapless Dirac cones, leading to a shift in the bulk Landau levels described by

where α = + for the Dirac cone at Γ and α = − for the cone at M. In this scenario, since the two gapless Dirac cones are shifted in opposite directions, the Hall conductance becomes zero when the chemical potential lies within the energy range − 4∣t∣ < EF < 4∣t∣. Illustrated in Fig. 4 panels (c) and (f), the Landau levels for t = 0.02α∥ exhibit distinct characteristics under two separate open boundary conditions: within the energy range −4∣t∣ < EF < 4∣t∣, a pair of helical edge states emerge along the \(\hat{x}\) boundary, whereas the \(\hat{y}\) boundary shows an absence of states. To characterize this nontrivial state, we define the valley conducting channel as

where #Γ and #M denote the number of edge states at the Dirac cones at Γ and M, respectively, and i = x, y indicates the propagation direction along \(\hat{x}\) or \(\hat{y}\). Figure 4a and d schematically present the edge states for t = 0.02α∥, corresponding to \({N}_{x}^{V}=0\) and \({N}_{y}^{V}=1\), respectively, highlighting the anisotropy of the conducting edge channels.

If we consider t < 0, the Landau levels for the Dirac cones at Γ and M shift in opposite directions. Consequently, the ribbon oriented along the \(\hat{x}\) direction is gapless, whereas the ribbon along the \(\hat{y}\) direction is gapped. This leads to the emergence of edge states with zero quantum Hall conductance exclusively at the \(\hat{y}\) terminal, contrasting with the scenario for t > 0. The valley conducting channel then becomes \({N}_{x}^{V}=1,{N}_{y}^{V}=0\). As a result, in the range −4∣t∣ < EF < 4∣t∣, the system exhibits zero Hall conductance but consistently presents edge states on either the \(\hat{x}\) or \(\hat{y}\) terminal, depending on the sign of t. The edge transport is expected to exhibit robustness against long-range disorder. This is due to the fact that the backscattering channels localized at the identical edge are situated at the opposing valley. Consequently, such backscattering is expected to be significantly diminished by the presence of long-range disorder.

The existence of edge channels also strongly depends on the sign of the magnetic field B. Setting eB/ℏ = − 0.01α∥, while keeping other parameters unchanged, alters the outcomes compared to those in Fig. 4; the \(\hat{y}\) terminal becomes gapless, whereas the \(\hat{x}\) terminal is gapped. The pronounced anisotropy of the conducting channels suggests the potential for a magnetic field-controlled switch, as depicted in Fig. 5. A voltage is applied between electrodes 1 and 2, between which the electronic current is dependent on the orientation of the magnetic field. When the magnetic field is directed upward, two pairs of conducting channels connect electrodes 1 and 2. The current I12 is nonzero and calculated from the Landauer-Büttiker formula53 as I12 = 2e/h(μ1 − μ2), in which μ1,2 are the chemical potentials at electrodes 1 and 2. Conversely, when the magnetic field is directed downward, charge transport through electrodes 1 and 2 is inhibited. This magnetic-controlled transport signature epitomizes the anisotropy of the Landau levels in the C4zT semimetal. Moreover, due to the influence of spin–orbit coupling, the spin polarization of the conducting channels on opposite edges is antiparallel, adhering to C2z symmetry. Such spin-polarized charge currents at the edge can also be detected by attaching a material with strong spin–orbit coupling to the edge. This setup can be utilized to measure the inverse spin Hall effect within that material54.

The voltage V12 is applied between electrodes 1 and 2, and the resulting charge current I12 is dependent on the orientation of magnetic field. a When Bz > 0, two pairs of conducting channels connect electrodes 1 and 2, leading to nonzero current. b Conversely, when Bz < 0, the conducting channels between electrodes 1 and 2 are shut down, causing the current to vanish. The yellow and green arrows indicate the flowing directions of the channels, and the red arrows indicate the spin orientation within the channels.

Orbital magnetization island

The nontrivial edge current, discussed in “Model and edge effect" subsection, can induce orbital magnetization. We delve into the orbital effects in semimetals by calculating the orbital magnetization. For electrons confined to the xy plane, the out-of-plane local orbital magnetization is given by \(M=\frac{e}{2c}{{\bf{r}}}\times {{\bf{v}}}\), where r is the position vector and \({{\bf{v}}}=\frac{i}{\hslash }[H,{{\bf{r}}}]\) represents the velocity operator. Employing the ground-state projector \({{\mathcal{P}}}={\sum }_{{\epsilon }_{n} < \mu }\left| {\psi }_{n}\right\rangle \left\langle {\psi }_{n}\right|\) and its complement \({{\mathcal{Q}}}=1-{{\mathcal{P}}}\), the local orbital magnetization is formulated as55,56,57:

We perform the calculations for a sample with dimensions Nx × Ny = 60 × 60 as depicted in Fig. 6a for t = 0.1α∥, μ = 0 and Fig. 6c for t = 0.1α∥, μ = 0.1α∥. The sample is partitioned into four quadrants by C4zT symmetry, with magnetization nullifying at the quadrant boundaries. The magnetization peaks at the edges and exhibits an oscillatory decay into the bulk, mirroring the ribbon’s equilibrium current oscillations. Consequently, magnetization forms discrete islands where the local orbital magnetic moments are uniformly aligned within each island, but adjacent islands exhibit opposing orientations. The island size correlates with the equilibrium current’s oscillation wavelength in the ribbon, approximately \(2\pi \left| \frac{{\alpha }_{\parallel }}{{E}_{F}^{\Gamma /M}}\right|\). We present the magnetization along the central axis x = Ny/2 in Fig. 6b and (d) with a violet line. Additionally, we utilize the equilibrium current from Fig. 3b to compute the average magnetization through the relation \(M(y)=-\frac{2\pi }{c}\int_{{R}_{U/D}}^{y}{J}_{x}({y}^{{\prime} })d{y}^{{\prime} }\). These findings are illustrated in Fig. 6b and d with a red line. By applying the current expression JF from Eq. (7), we derive the analytical form of the magnetization as \({M}_{F}={M}_{\Gamma }^{U}+{M}_{\Gamma }^{D}+{M}_{M}^{U}+{M}_{M}^{D}\) with

where \({G}_{pq}^{mn}\left[\left.\begin{array}{c}{a}_{1},\cdots \,,{a}_{n},{a}_{n+1}\cdots \,,{a}_{p}\\ {b}_{1},\cdots \,,{b}_{m},{b}_{m+1}\cdots \,,{b}_{q}\end{array}\right| \xi ,s\right]\) denotes the Meijer G-function, with ξ defined as \(\xi =\left| \frac{{E}_{F}^{\Gamma /M}}{{\alpha }_{\parallel }}\left(y-{R}_{U/D}\right)\right|\). The analytic magnetization results, MF, are superimposed in Fig. 6(b) and (d) with a blue line for comparison with the numerical data, showing good agreement except near the edge.

a Orbital magnetization Mz(x, y) for a 60 × 60 square lattice with t = 0.1α∥ and μ = 0. The dot size and color denote the magnitude of magnetization in units of e/ℏc at each lattice site. The magnetization pattern exhibits C4zT symmetry and features isolated islands approximately \(2\pi \left\vert {\alpha }_{\parallel }/{E}_{F}^{\Gamma /M}\right\vert\) in size. b Orbital magnetization profile along x = Ny/2 indicated by the dashed line in a, with the violet line representing numerical data from a, the red line representing integration of the equilibrium current from the ribbon in Fig. 3(b), and the blue line corresponding to the expression for MF from Eq. (12). c Orbital magnetization for t = 0.1α∥ and μ = 0.1α∥. d The same as b, but with parameters t = 0.1α∥ and μ = 0.1α∥ corresponding to c.

The formation of orbital magnetization islands is a distinctive feature in topological semimetals with C4zT symmetry, indicative of the intricate interplay between nontrivial Berry curvature in the bulk and the oscillatory equilibrium current under open boundary conditions. Unlike magnetic domains that arise from spin correlations, these orbital magnetization islands originate from the electrons’ cyclic motion. The magnetic fields generated by these islands can be detected using a nanoscale superconducting quantum interference device (SQUID), as reported by58.

Filling-enforced magnetic semimetals

Although above studies are based on a two-band model, the conclusions are general for multi-bands when the crossing two bands are separated from other bands and the filling Fermi energy is near the Dirac point. In this section, we focus on the four-band Hamiltonian constrained by C4zT symmetry. We consider a system with two different atoms, A and B, in each unit cell. The C4zT symmetry operation transforms the annihilation operators as follows:

where \({\psi }_{i{{\bf{r}}}}={[{c}_{i,\uparrow ,{{\bf{r}}}},{c}_{i,\downarrow ,{{\bf{r}}}}]}^{T}\) with i = A, B represents the two-component spinor for atom i at site r. The transformation matrix \({U}_{{C}_{4z}T}={e}^{i\frac{\pi }{4}{\sigma }_{z}}i{\sigma }_{y}\) represents the C4zT symmetry in the spinor representation. resultant two-fold rotational symmetry \({C}_{2z}={({C}_{4z}T)}^{2}\) transforms the annihilation operators as:

with \({U}_{{C}_{2z}}=-i{\sigma }_{z}\). The intra-unit cell Hamiltonian which can be expressed as

with \({\Psi }_{{{\bf{r}}}}={[{\psi }_{A,{{\bf{r}}}},{\psi }_{B,{{\bf{r}}}}]}^{T}\). The two symmetry constraints given by C2z and C4zT are

where the Pauli matrices τ act on the subspace spanned by atoms A and B. These conditions restrict the intra-unit cell Hamiltonian as

with U0 and Uz being the real numbers, and λ0 a complex number. We next consider the nearest neighbor inter-unit cell hopping which can be expressed as

where ex and ey are the basis vectors of the square lattice, and Hx and Hy are the hopping matrices along two directions. Under the given symmetries, we have

The allowed form for the inter-unit cell hopping matrices are

with \({\gamma }_{0/z}^{AA},{\gamma }_{0/z}^{BB}\),\({\gamma }_{x/y}^{AA}\), \({\gamma }_{x/y}^{BB}\) being real, and \({\gamma }_{0,x,y,z}^{AB}\) the complex parameters. The full Hamiltonian is given by \(\hat{H}={\hat{H}}_{{{\rm{intra}}}}+{\hat{H}}_{{{\rm{inter}}}}\).We construct a basis of Bloch waves using the Fourier transformation: \({\Psi }_{{{\bf{k}}}}^{{\dagger} }=\frac{1}{\sqrt{N}}{\sum }_{{{\bf{r}}}}{e}^{i{{\bf{k}}}\cdot {{\bf{r}}}}{\Psi }_{{{\bf{r}}}}^{{\dagger} }\) where N is the number of the unit cells. The Hamiltonian in the momentum space is expressed as \(\hat{H}={\sum }_{{{\bf{k}}}}{\Psi }_{{{\bf{k}}}}^{{\dagger} }H({{\bf{k}}}){\Psi }_{{{\bf{k}}}}\) with

As indicated in Eq. (17), the presence of C4zT symmetry, allows for internal time-reversal symmetry breaking at one atomic site, while requiring time-reversed counterparts at other locations within the unit cell. The simplest example of this is a two-site antiferromagnet, where the up spins on A sites are the time-reverses of the down spins on B sites. Then, the system comprises four bands. We then introduce a strong antiferromagnetic potential, assumed to dominate over other hopping and energy terms, effectively splitting the system into two two-band systems. In the 1/4 filling, it is a C4zT topological semimetal with two Dirac cones near the Fermi energy. Figure 7a shows the bandstructure with Uz = 2.5. (b) shows the Berry curvature distribution of the lowest band, in which a BZ is partitioned into two patches with Berry curvature flux C+ and C−, respectively. The flux is nearly half-quantized with the increasing of Uz, which is the consequence that the strong Uz pushes the higher two bands far away, as shown in Fig. 7c. Such a result demonstrates the fragile nature59 of the half-quantized Berry curvature flux. In the open ribbon along x-direction, the local density of states near the y = 0 edge is calculated by

with \({G}^{R}({k}_{x},E)={\sum }_{n}\frac{\left| {\psi }_{n}({k}_{x})\right\rangle \left\langle {\psi }_{n}({k}_{x})\right| }{E+i{0}_{+}-{E}_{n}({k}_{x})}\). The result is shown in Fig. 7 (d), which reveals the right and left propagating conducting channels near kx = 0 and π valleys, respectively. Figure 7 (e) shows the valley edge current depending on the chemical potential μ, and the derivation \(\partial {J}_{edge}^{V}/\partial \mu\). Coincident with the two-band model, \(\partial {J}_{edge}^{V}/\partial \mu\) is quantized to be one-half, demonstrating the half-edge counter-propagating conducting channel. Furthermore, we calculate the Landau levels in Fig. 7f, which exhibits the behavior as the same as the two-band model. These results indicate that the nontrivial edge properties and Landau physics are general for C4zT topological semimetals. Hence, one can adjust the filling factor of the C4zT insulators to obtain such an interesting filling-enforced semimetal phase.

a The bandstructure with Uz = 2.5. Other parameters are set as \({U}_{0}=0,{\lambda }_{0}=0.1+0.2i,{\gamma }_{0}^{AA}=-0.2,{\gamma }_{x}^{AA}=0.1\), \({\gamma }_{y}^{AA}=0.05,{\gamma }_{z}^{AA}=0.1,{\gamma }_{0}^{BB}=0.2\), \({\gamma }_{x}^{BB}=0.2,{\gamma }_{y}^{BB}=0.03,{\gamma }_{z}^{BB}=0.1\), and \({\gamma }_{0}^{AB}=0.1+0.2i,{\gamma }_{x}^{AB}=0.3+0.1i,{\gamma }_{y}^{AB}=0.1-0.2i\), \({\gamma }_{z}^{AB}=0.2-0.3i\). b The Berry curvature distribution of the lowest band in the momentum space. A Brillouin zone is partitioned into two patches with Berry curvature flux C+ and C−, respectively. c Blue line is the dependence of C+ on Uz. With the increasing of Uz, C+ approaches 1/2 rapidly. 400 × 400 momentum points are used in the calculation. Red line is the dependence of ΔE (the gap between the lower two bands and the higher two bands) on Uz. d Local density of states near the y = 0 edge, where brighter colors highlight the presence of net conducting channels. e Variation of the valley edge current \({J}_{edge}^{V}(\mu )\), shown with blue circles (the red line below is the fitting line of the numerical results), and its derivative \(\partial {J}_{edge}^{V}/\partial \mu\), depicted by the yellow line, as a function of the chemical potential μ. The momentum cutoff kc is taken as 0.15. f Landau levels in a ribbon along x-direction with eB/ℏ = 0.01. Colors denote the expectation of the location of states, with blue and yellow circles indicating edge states localized at the y = 0 and Ly boundaries, respectively.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this work uncovers a topological semimetal phase marked by a half-quantized Berry curvature flux within the Brillouin zone (BZ). This phase is distinguished by two massless Dirac cones, upheld by C4zT symmetry, and exhibits nontrivial topological features in the energy bands. These characteristics give rise to counter-propagating half-edge channels and power-law decaying oscillatory edge currents. Consequently, the equilibrium current fosters the formation of orbital magnetization islands, which paves the way for innovative explorations in the field of magnetism. When exposed to an external magnetic field, the semimetal manifests exceptional Landau-level dynamics, including integer quantum Hall effects localized in each massless Dirac cone, alongside anisotropic behaviors in the zeroth Landau level. Furthermore, the system displays conductivity along one edge while maintaining insulation along the perpendicular edge, suggesting its potential as a magnetic field-controlled switch for conductive pathways.

The theoretical framework presented here is pertinent to a spectrum of materials belonging to the \(P{4}^{{\prime} }\) magnetic symmetry group. This envisioned topological semimetal phase could also be emulated in electrical circuits, which have recently emerged as a versatile platform for materializing a variety of topological quantum states that are otherwise challenging to realize in actual materials60,61,62,63,64, encompassing Chern insulators65,66, four-dimensional topological insulators67,68, Weyl semimetals69,70,71, and quantum anomalous semimetals32,42. In such circuits, a systematic arrangement of inductors (L) and capacitors (C) constructs a network of LC resonators. The circuit Laplacian mirrors the tight-binding Hamiltonian, where the tunable effective hopping parameters can be manipulated to mimic the models described in Eq. (1) and (5). The distinctive edge channels and currents can thus be probed by injecting an external current signal into the topological circuit.

Methods

The low-energy effective model of the gapless Dirac cone

In the vicinity of the C4zT-invariant points Γ and M, the system exhibits a gapless structure. We now analyze the unconventional Dirac node structure associated with C4zT symmetry and its unique boundary effect. In general, the low-energy k ⋅ p Hamiltonian takes the form H(k) = f(k)σ+ + f*(k)σ− + g(k)σz, where σ± = (σx ± iσy)/2. Here, f and g are complex and real functions of k = (kx, ky), respectively, resulting from the Hermiticity of H. Since we are interested in the gapless bandstructure in the vicinity of node points Γ and M, we can expand f and g to leading order as \(f({k}_{+},{k}_{-})={\alpha }_{\parallel }{k}_{+}^{p}{k}_{-}^{q},g({k}_{+},{k}_{-})={v}^{{\prime} }{k}_{+}^{r}{k}_{-}^{s}+H.c.\) where \({\alpha }_{\parallel },v{\prime} \in {\mathbb{C}}\) and p, q, r, s are non-negative integers, k± = kx ± iky. Now, we consider the symmetry constraints imposed by C4zT, SH(k)S−1 = H(Dk). The C4zT symmetry can be represented by the operator \(S={e}^{-i\frac{\pi }{4}{\sigma }_{z}}i{\sigma }_{y}K\), which puts a constraint on f and g as if(k) = f(Dk) and −g(k) = g(Dk). At the lowest nonvanishing order of k, we find f(k) = α∥k− and \(g({{\bf{k}}})={v}^{{\prime} }{k}_{+}^{2}+{v}^{{\prime} * }{k}_{-}^{2}\). The resulting gapless Hamiltonian in a C4zT metal can be expressed as

The g(k) term is allowed by the symmetry and marks a distinction from conventional Dirac fermions, such as those in graphene, and topological insulator surface states. We next explore the effects of the g(k) term on boundary behaviors by solving this continuum model in a finite strip geometry of the width L, with the periodic boundary condition in the y-direction and an open boundary condition in the x-direction. Here, ky is a good quantum number, but kx is replaced by kx = − i∂/∂x. For ky = 0, the eigenvalue equation is:

with \({\alpha }_{z}=2{{\rm{Re}}}{v}^{{\prime} }\). Using a trial function \(\Psi (x)={[{\psi }_{A},{\psi }_{B}]}^{{{\rm{T}}}}{e}^{i\xi x}\), solving this eigenvalue equation yields four root \({\xi }_{\pm }^{2}=\frac{-| {\alpha }_{\parallel }^{2}| \pm \sqrt{| {\alpha }_{\parallel }^{4}| +4{\varepsilon }^{2}{\alpha }_{z}^{2}}}{2{\alpha }_{z}^{2}}\). The general solution for Ψ is now a superposition of these four solutions \(\Psi ={\sum }_{s,\zeta = \pm }{c}_{\zeta s}{[-\zeta {\alpha }_{\parallel }{\xi }_{s},{\alpha }_{z}{\xi }_{s}^{2}-\varepsilon ]}^{{{\rm{T}}}}{e}^{i\zeta {\xi }_{s}x}\) with the coefficients cζs determined by the boundary conditions Ψ(0) = Ψ(L) = 0. This leads to the eigenequation:

The nontrivial solution for the coefficients cζs leads to a secular equation

In the limit αz → 0, such that \({\xi }_{1}\approx \frac{\varepsilon }{\alpha },{\xi }_{2}\to \infty\),the secular equation simplies to \(\cos \frac{\varepsilon L}{| {\alpha }_{\parallel }| }=0,\) yielding the eigenenergies as \({\varepsilon }_{n}=| {\alpha }_{\parallel }| \frac{\pi }{L}(\frac{1}{2}+n)\). The corresponding eigenfunctions can be determined by substituting these eigenenergies back into the eigenequation (24) and applying normalization. The energy dispersion is obtained by projecting the leading ky -dependent term in the Hamiltonian, \((-{\alpha }_{\parallel }{\sigma }_{+}+{\alpha }_{\parallel }^{* }{\sigma }_{-})i{k}_{y}\) onto Ψn. This procedure results in the following expression for the energy dispersion: \({\varepsilon }_{n}({k}_{y})=| {\alpha }_{\parallel }| \sqrt{{k}_{y}^{2}+{[\frac{\pi }{L}(\frac{1}{2}+n)]}^{2}}\) which shows good consistency with numerical results. The corresponding eigenfunctions are given by:

with \(\cos ({\kappa }_{n})={{\rm{sgn}}}({\alpha }_{z})\frac{| {\alpha }_{\parallel }| {k}_{y}}{{\varepsilon }_{n}({k}_{y})}\). We can calculate the average displacement relative to the center of the ribbon for each state: \(\langle {\Psi }_{n{k}_{y}}| (\frac{x}{L}-\frac{1}{2})| {\Psi }_{n{k}_{y}}\rangle ={{\rm{sgn}}}({\alpha }_{z})\frac{| {\alpha }_{\parallel }| {k}_{y}}{{\varepsilon }_{n}({k}_{y})}\frac{2}{{\pi }^{2}{(2n+1)}^{2}}\), which is proportional to the propagation velocity of each mode, \(\frac{| {\alpha }_{\parallel }| {k}_{y}}{{\varepsilon }_{n}({k}_{y})}\), and is also determined by the sign of αz. This result implies that for positive αz, down-propagating states are located in the left half of the ribbon and up-propagating states in the right half. Conversely, for negative αz, the average displacement of the states is reversed. Since αz is the opposite for Γ and M points From Eq. (1), the local density of states (LDOS) exhibits contrasting behaviors at these points.

The Berry curvature Ω(k, θ) in polar coordinate k = (k, θ) for the model described in Eq. (23) can be evaluated as

The lines where the Berry curvature vanishes are defined by the condition \(\cos (2\theta +{{\rm{Arg}}}v)=0\). This condition results in two vertical lines, defined by the angles: \({\theta }_{\pm }=\pm \frac{\pi }{4}-\frac{1}{2}{{\rm{Arg}}}v\), which divide the Brilloun zone around the gapless point into four patches. As the radial integral of Berry curvature can be calculated as \(\int\,dkk\Omega (k,\theta )=\frac{1}{4\pi }{{\rm{sgn}}}[\cos (2\theta +{{\rm{Arg}}}v)]\), the integral over each patches, which sweep through a π/2 polar angle, equals \(\frac{1}{8}\) with the sign determined by \({{\rm{sgn}}}[\cos (2\theta +{{\rm{Arg}}}v)]\). Finally, considering the presence of two such gapless node points in the full Brillounin zone (namely, at the Γ and M points), the integral of the Berry curvature over the two regions divided by the Berry curvature vanishing line exhibits half-quantization.

Data availability

The data that support this paper are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The computer codes used in this paper are accessible from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Novoselov, K. S. et al. Electric field effect in atomically thin carbon films. Science 306, 666 (2004).

Neto, A. H. C., Guinea, F., Peres, N. M. R., Novoselov, K. S. & Geim, A. K. The electronic properties of graphene. Rev. Mod. Phys. 81, 109 (2009).

Malko, D., Neiss, C., Vines, F. & Gorling, A. Competition for graphene: graphynes with direction-dependent Dirac cones. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 086804 (2012).

Zhou, X. F. et al. Semimetallic two-dimensional boron allotrope with massless Dirac fermions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 085502 (2014).

Young, S. M. & Kane, C. L. Dirac semimetals in two dimensions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 126803 (2015).

Liu, G. et al. Multiple Dirac points and hydrogenation-induced magnetism of germanene layer on Al (111) surface. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 6, 4936 (2015).

Lu, Y. et al. Multiple unpinned Dirac points in group-Va single-layers with phosphorene structure. npj Comput. Mater. 2, 16011 (2016).

You, J. Y. et al. Two-dimensional Weyl half-semimetal and tunable quantum anomalous Hall effect. Phys. Rev. B 100, 064408 (2019).

Wu, D. et al. Phase-controlled van der Waals growth of wafer-scale 2D MoTe2 layers for integrated high-sensitivity broadband infrared photodetection. Light Sci. Appl. 12, 5 (2023).

Guan, S. et al. Two-dimensional spin-orbit Dirac point in monolayer HfGeTe. Phys. Rev. Mater. 1, 054003 (2017).

Wang, J. Antiferromagnetic Dirac semimetals in two dimensions. Phys. Rev. B 95, 115138 (2017).

Young, S. M. & Wieder, B. J. Filling-enforced magnetic Dirac semimetals in two dimensions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 186401 (2017).

Damljanovic, V., Popov, I. & Gajic, R. Fortune teller fermions in two-dimensional materials. Nanoscale 9, 19337 (2017).

Kowalczyk, P. J. et al. Realization of symmetry-enforced two-dimensional Dirac fermions in nonsymmorphic α-bismuthene. ACS Nano 14, 1888 (2020).

Jin, Y. et al. Two-dimensional Dirac semimetals without inversion symmetry. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 116402 (2020).

Zhu, L. et al. Blue phosphorene oxide: strain-tunable quantum phase transitions and novel 2D emergent fermions. Nano Lett. 16, 6548 (2016).

Hua, C. et al. Tunable topological energy bands in 2D dialkali-metal monoxides. Adv. Sci. 7, 1901939 (2020).

Shen, R., Shao, L. B., Wang, B. & Xing, D. Y. Single Dirac cone with a flat band touching on line-centered-square optical lattices. Phys. Rev. B 81, 041410(R) (2010).

Paavilainen, S. et al. Coexisting honeycomb and kagome characteristics in the electronic band structure of molecular graphene. Nano Lett. 16, 3519 (2016).

Slager, R. J. et al. The space group classification of topological band-insulators. Nat. Phys. 9, 98–102 (2013).

Bradlyn, B. et al. Topological quantum chemistry. Nature 547, 298–305 (2017).

Kruthoff, J. et al. Topological classification of crystalline insulators through band structure combinatorics. Phys. Rev. X 7, 041069 (2017).

Vergniory, M. G. et al. A complete catalogue of high-quality topological materials. Nature 566, 480–485 (2019).

Bouhon, A., Black-Schaffer, A. M. & Slager, R. J. Wilson loop approach to fragile topology of split elementary band representations and topological crystalline insulators with time-reversal symmetry. Phys. Rev. B 100, 195135 (2019).

Tang, F. et al. Comprehensive search for topological materials using symmetry indicators. Nature 566, 486–489 (2019).

Zhang, T. et al. Catalogue of topological electronic materials. Nature 566, 475–479 (2019).

Bernevig, B. A., Felser, C. & Beidenkopf, H. Progress and prospects in magnetic topological materials. Nature 603, 41–51 (2022).

Nomura, K., Koshino, M. & Ryu, S. Topological delocalization of two-dimensional massless Dirac fermions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 146806 (2007).

Yu, Z. M., Yao, Y. & Yang, S. A. Predicted unusual magnetoresponse in type-II Weyl semimetals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 077202 (2016).

Udagawa, M. & Bergholtz, E. Field-selective anomaly and chiral mode reversal in type-II Weyl materials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 086401 (2016).

Feng, X. L., Zhu, J. J., Wu, W. K. & Yang, S. A. Two-dimensional topological semimetals. Chin. Phys. B 30, 107304 (2021).

Fu, B., Zou, J. Y., Hu, Z. A., Wang, H. W. & Shen, S. Q. Quantum anomalous semimetals. npj Quant. Mater. 7, 94 (2022).

Zou, J. Y., Fu, B., Wang, H. W., Hu, Z. A. & Shen, S. Q. Half-quantized Hall effect and power law decay of edge-current distribution. Phys. Rev. B 105, L201106 (2022).

Zou, J. Y. et al. Half-quantized hall effect at the parity-invariant fermi surface. Phys. Rev. B 107, 125153 (2023).

Wang, H. W., Fu, B. & Shen, S. Q. Recent progress of transport theory in Dirac quantum materials. Acta Phys. Sin. 72, 177303 (2023).

Fradkin, E., Dagotto, E. & Boyanovsky, D. Physical realization of the parity anomaly in condensed matter physics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 57, 2967 (1986).

Haldane, F. D. M. Model for a Quantum Hall effect without landau levels: condensed-matter realization of the parity anomaly. Phys. Rev. Lett. 61, 2015 (1988).

Schakel, A. M. J. Relativistic quantum Hall effect. Phys. Rev. D. 43, 1428 (1991).

Qi, X.-L., Hughes, T. L. & Zhang, S.-C. Topological field theory of time-reversal invariant insulators. Phys. Rev. B 78, 195424 (2008).

Böttcher, J., Tutschku, C., Molenkamp, L. W. & Hankiewicz, E. M. Survival of the quantum anomalous hall effect in orbital magnetic fields as a consequence of the parity anomaly. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 226602 (2019).

Liu, G.-G. et al. Observation of an unpaired photonic Dirac point. Nat. Commun. 11, 1873 (2020).

Yang, H., Song. L., Cao, Y. & Yan, P. Realization of Wilson fermions in topolectrical circuits. Commun. Phys. 6, 211 (2023).

Leykam, D., Rechtsman, M. C. & Chong, Y. D. Anomalous topological phases and unpaired Dirac cones in photonic floquet topological insulators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 013902 (2016).

Hu, H., Tong, W.-Y., Shen, Y.-H., Wan, X. & Duan, C.-G. Concepts of the half-valley-metal and quantum anomalous valley Hall effect. npj Comput. Mater. 6, 129 (2020).

Lu, R. et al. Half-magnetic topological insulator with magnetization induced Dirac gap at a selected surface. Phys. Rev. X 11, 011039 (2021).

Mogi, M. et al. Experimental signature of the parity anomaly in a semi-magnetic topological insulator. Nat. Phys. 18, 390 (2022).

Beenakker, C. Anomalous quantum anomalous Hall effect. J. Club Condens. Matter Phys. https://doi.org/10.36471/JCCM_October_2022_02 (2022).

Schindler, F. et al. Higher-order topological insulators. Sci. Adv. 4, eaat0346 (2018).

Wang, Y. X., Lin, M. & Hughes, T. L. Weak-pairing higher order topological superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 98, 165144 (2018).

Ghorashi, S. A. A., Hughes, T. L. & Rossi, E. Vortex and surface phase transitions in superconducting higher-order topological insulators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 037001 (2020).

Day, I. A., Varentcova, A., Varjas, D. & Akhmerov, A. R. Pfaffian invariant identifies magnetic obstructed atomic insulators. SciPost Phys. 15, 114 (2023).

Bernevig, B. A. and Hughes, T. L. Topological Insulators and Topological Superconductors (Princeton University Press, Princeton, 2013).

Datta, S. Electronic Transport in Mesoscopic Systems (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1995).

Morimoto, T., Furusaki, A. & Nagaosa, N. Charge and spin transport in edge channels of a ν = 0 quantum Hall system on the surface of topological insulators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 146803 (2015).

Bianco, R. & Resta, R. Orbital magnetization as a local property. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 087202 (2013).

Bianco, R. & Resta, R. Mapping topological order in coordinate space. Phys. Rev. B 84, 241106(R) (2011).

Tran, D. T., Dauphin, A., Goldman, N. & Gaspard, P. opological Hofstadter insulators in a two-dimensional quasicrystal. Phys. Rev. B 91, 085125 (2015).

Uri, A. et al. Nanoscale imaging of equilibrium quantum Hall edge currents and of the magnetic monopole response in graphene. Nat. Phys. 16, 164 (2020).

Po, H. C., Watanabe, H. & Vishwanath, A. Fragile topology and Wannier obstructions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 126402 (2018).

Ningyuan, J., Owens, C., Sommer, A., Schuster, D. & Simon, J. Time- and site-resolved dynamics in a topological circuit. Phys. Rev. X 5, 021031 (2015).

Albert, V. V., Glazman, L. I. & Jiang, L. Topological properties of linear circuit lattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 173902 (2015).

Zhao, E. Topological circuits of inductors and capacitors. Ann. Phys. 399, 289 (2018).

Lee, C. H. et al. Topolectrical circuits. Commun. Phys. 1, 39 (2018).

Helbig, T. et al. Band structure engineering and reconstruction in electric circuit networks. Phys. Rev. B 99, 161114(R) (2019).

Hofmann, T., Helbig, T., Lee, C. H., Greiter, M. & Thomale, R. Chiral voltage propagation and calibration in a topolectrical chern circuit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 247702 (2019).

Wang, Z. et al. Realization in circuits of a Chern state with an arbitrary Chern number. Phys. Rev. B 107, L201101 (2023).

Wang, Y., Price, H. M., Zhang, B. L. & Chong, Y. D. Circuit implementation of a four-dimensional topological insulator. Nat. Commun. 11, 2356 (2020).

Yu, R., Zhao, Y. X. & Schnyder, A. P. 4D spinless topological insulator in a periodic electric circuit. Natl Sci. Rev. 7, 1288 (2020).

Lu, Y. et al. Probing the Berry curvature and Fermi arcs of a Weyl circuit. Phys. Rev. B 99, 020302(R) (2019).

Rafi-Ul-Islam, S. M., Bin Siu, Z. & Jalil, M. B. A. Topoelectrical circuit realization of a Weyl semimetal heterojunction. Commun. Phys. 3, 72 (2020).

Rafi-Ul-Islam, S. M., Bin Siu, Z., Sun, C. & Jalil, M. B. A. Realization of Weyl semimetal phases in topoelectrical circuits. N. J. Phys. 22, 023025 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Huan-Wen Wang for the helpful discussion. The work was supported by the Scientific Research Starting Foundation of Huazhong University of Science and Technology (Grant No. 3034132103), Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation No. 2024A1515010430 and 2023A1515140008, the Research Grants Council, University Grants Committee, Hong Kong under Grant Nos. C7012-21G and No. 17301823;

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.Y.Z., B.F., and S.Q.S. initiated the presented idea. J.Y.Z. performed the calculations. All authors discussed the results and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zou, JY., Fu, B. & Shen, SQ. Topological properties of C4zT-symmetric semimetals. Commun Phys 7, 275 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-024-01767-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-024-01767-7

- Springer Nature Limited