Abstract

Background

The importance of optimal postoperative glycemic control in cardiac patients remains unclear. Various glycemic targets have been prescribed to reduce wound infection and overall mortality rates.

Aim of the work: To assess glucose control, as determined by time in range (TIR), in patients with glycemic targets of 6.0 to 8.1 mmol/L, and to determine factors related to poor control.

Methods

This prospective descriptive study evaluated 227 consecutive patients, 100 with and 127 without diabetes, after cardiac surgery. Patients received insulin to target glucose concentrations of 6.0 to 8.1 mmol/L. Data analyzed included patient age, gender, race, Euro score, cardiopulmonary bypass time (CPB), aortic cross clamp time (ACC), length of ventilation, stay in the intensive care unit (ICU) and stay in the hospital. Patients were divided into two groups, those who maintained > 80% and < 80% TIR. Outcome variables were compared in diabetics and non-diabetics.

Results

Patients with >80% and <80% TIR were matched in age, sex, gender, and Euro score. Failure to maintain target glycemia was significantly more frequent in diabetics (p = 0.001), in patients with glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) > 8% (p = 0.0001), and in patients taking dopamine (p = 0.04) and adrenaline (p = 0.05). Times of CPB and ACC, length of stay in the ICU and ventilation were significantly higher in patients with TIR <80% than >80%. Rates of hypoglycemia, acute kidney injury, and in-hospital mortality were similar in the two groups, although the incidence of wound infection was higher in patients with TIR <80%. Both diabetics and non-diabetics with low TIR had poorer outcomes, as shown by length of stay and POAF. No significant differences were found between the two ethnic groups (Arabs and Asians).

Conclusion

Patients with >80% TIR, whether or not diabetics, had better outcomes than those with <80% TIR, as determined by wound infection, lengths of ventilation and ICU stay. Additionally, they were not subject to frequent hypoglycemic events. Preoperatively high HbA1C is likely a good predictor of poor glycemic control.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Tracking adherence to insulin infusion protocols and the use of standard metrics are key to maintaining glucose control. Control practices after cardiac surgery were shown to reduce mediastinitis [1]. Poor perioperative control of blood glucose concentration may be associated with poorer outcomes in patients undergoing cardiac surgery [2].

Tight glucose control has been reported to improve acute outcomes in hospitalized diabetic patients, including risks of infection and death [3, 4]. Tight glucose control, through continuous intravenous injection of insulin, was also found to reduce mediastinitis and mortality rates, as well as costs and length of hospital stay, in diabetic patients after cardiac surgery [2–5]. Other advantages of tight glucose control in cardiac surgery patients include reductions in the rates of postoperative atrial fibrillation (POAF) and ischemia [5].

Although maintaining normoglycemia between 4.4 and 6.1 mmol/L using intensive insulin therapy reduced mortality in the surgical intensive care unit (ICU), as well as organ complications associated with critical illness, tight insulin control was also associated with frequent hypoglycemic episodes [6]. Moreover, a recent study showed that intensive insulin therapy (6.1–8.3 mmol/L) yielded superior outcomes when compared with less intense control targeting higher glucose concentrations [7].

Cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) has been shown to affect glucose control, with controlling blood glucose being difficult during cardiac surgery [8]. Tight blood glucose control during CPB was not easily achieved owing to the exacerbation of insulin resistance. In addition [9], an investigation of blood glucose homeostasis derangement showed that glucose levels were increased and insulin levels decreased during hypothermic CPB [9].

Insulin resistance has been associated with increased levels of inflammatory cytokines in critically ill patients. Concomitant insulin resistance plus hypothermia may be aggravated by insulin adherence to the plastic material included in the extracorporeal circuit, by glucose administration in cardioplegia solution, and by the steroids that may be used to reduce inflammatory responses to CPB. Blood glucose concentrations tend to increase after rewarming, as do levels of catecholamines, glucagon, and growth hormone [10]. The underlying molecular mechanisms of this insulin resistance are not fully understood, although transmembrane protein defects are thought to play a role [11].

Ethnic differences in insulin sensitivity have been associated with variations in body fat. South Asian adolescents are more insulin resistant, with more body fat, than white European adolescents, which may contribute to the higher risk in the former of developing type 2 diabetes [12]. Detrimental effects of hyperglycemia may affect critically ill non-diabetic and diabetic patients. The harmful effects of intensive hyperglycemic control are still considered speculative [13], and the three domains of glycemic control hyperglycemia, hypoglycemia and glucose variability could affect outcomes in critically ill patients [14]. This study therefore evaluated patient outcomes after implementation of a validated insulin protocol [15], by assessing time in range (TIR) to investigate factors related to poor glucose control.

Methods

This prospective, descriptive, single-center study with purposive sampling evaluated 227 consecutive patients, 100 with and 127 without diabetes, after cardiac surgery. Patients who received insulin for at least 12 h were eligible. The study was performed from September 2012 to August 2013 in the 12-bed cardiothoracic ICU of Hamad Medical Corporation. The study was approved by the ethics committee of Hamad Medical Corporation (reference number 13156/13), which waived the requirement for informed consent, since no specific intervention was performed and blood sampling was part of routine care to control blood glucose post-operatively.

Mean blood glucose (BG) concentration was measured during infusion of 1.0 unit/mL of insulin at a rate sufficient to maintain a target glucose concentration of 6.0–8.1 mmol/L. Arterial blood was sampled every 1 h during the first 6–12 h after surgery, with capillary blood samples obtained by finger stick thereafter. BG concentrations were measured using the Accu-Check Inform II point-of-care meters (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). A quality control program was maintained to assess nurses’ compliance with and interpretation of the protocol. Nurses recorded BG concentrations, measurement times and insulin infusion rates on a daily ICU chart.

The main objective of this study was to investigate glucose control, using TIR 80% as the threshold, and factors associated with poor control. Total time of insulin infusion (A) and the period of time being within the target range (B) were measured in each patient during insulin infusion, with TIR calculated as B/A*100. Patients were divided into two groups based on successful maintenance of TIR, with Groups I and II consisting of individuals with TIRs >80% and <80%, respectively. Hypoglycemia was defined as BG <4 mmol/L and severe hypoglycemia as BG <2.2 mmol/L.

Factors assessed at admission to the ICU included age, sex, race, medical diseases, drugs, type of surgery, anesthesia time, CPB time, aortic cross clamp (ACC) time, use of inotropes and vasopressors, Euro SCORE, statin therapy, length of mechanical ventilation, and stay in the ICU and the hospital. Complications and outcomes, including acute kidney injury (AKI), POAF, infection, stroke, wound infection, and death, were recorded for each patient. Data were retrieved using Dendrite Clinical Systems (London, UK). Outcomes were compared in subgroups of diabetics and non-diabetics, and factors associated with poor glycemic control were analyzed. ICU stay was dichotomized as ≤48 hours and >48 hours.

Statistical analysis

Normally distributed continuous variables are reported as mean ± SD, non-normally distributed continuous variables as median and range, and categorical variables as frequency and percentage. Normally and non-normally distributed continuous variables were compared using Student’s t-tests and Mann–Whitney U tests, respectively, and categorical variables using Chi squared tests. A two-sided P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Variables influencing TIR in our and previous analyses were assessed by multivariate regression analysis. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Version 16 software (SPSS Inc. Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

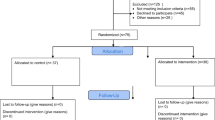

Of the 260 patients screened, 227 were enrolled; the remaining 33 patients were excluded because they were infused with insulin for < 12 h. The study population consisted mostly of males and had a mean age of 54.3 ± 10.8 years (Table 1); in addition, 43.1% of the patients were diabetics, and 59.3% were hypertensive. There was a higher proportion of Asians than Arabs in the studied population. The majority of patients underwent CABG surgery (Tables 1 and 2).

Patients were divided into two groups based on their success in maintaining target BG concentration. Group I consisted of patients with TIR >80% and Group II of patients with TIR < 80% (Table 3). The two groups were well matched in age, gender, BMI, association with hypertension, and Euro score. Non-diabetics showed better BG control than diabetics (Table 3). There were no significant differences between ethnic groups. Basal creatinine and EF% were similar in Groups I and II. HbA1C was significantly higher in Group II. Patients taking dopamine and adrenaline had poorer BG control, as were patients who underwent CABG. In contrast, patients who underwent valvular surgeries were more likely to have better BG control.

Table 4 summarizes the clinical outcomes in these patients. ACC and total anesthesia time were significantly higher in Group II, as were lengths of ICU and hospital stay and duration of mechanical ventilation. The percentages of patients with new POAF and wound infection were significantly higher in Group II, as was the rate of overall in-hospital mortality. Multivariate analysis showed that diabetes was the only independent predicator of poor glycemic control (Table 5). Variables affecting TIR were included in the multivariate model (Table 6). Comparisons of outcome variables in subgroups of diabetics and non-diabetics showed that TIR <80% was associated with longer lengths of stay and higher POAF frequency in both diabetics and non-diabetics (Tables 7 and 8). Moreover, multivariate analysis showed that TIR <80% was significantly associated with longer ICU stay (Table 9).

Discussion

The main findings of this study were that patients with higher TIR had better postoperative outcomes, whether they were non-diabetics or diabetics, and that a BG range of 6.0–8.1 mmol/L was safe in the studied population. In addition, HbA1C was found to predict poor glycemic control, ethnicity was unrelated to poor control and hourly sampling of BG after cardiac surgery is useful in patient monitoring.

Adverse outcomes in surgical patients may be due to hyperglycemia [16, 17], and insulin therapy in the ICU has yielded diverse outcomes [6, 18]. Based on mortality, morbidity, and long-term survival benefits, the guidelines of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons recommended a glycemic control target of 6.1–8.0 mmol/L glucose after cardiac surgery [19]. More recently, moderate glycemic control after cardiac surgery showed better outcomes [20], and the literature relating to intensity of BG control in CV surgery patients is somewhat conflicted [21].

Diabetics comprised 43.1% of the patients in our study, compared with 13% and 20% in the Leuven and NICE-SUGAR studies, respectively. Diabetes is highly prevalent in populations, along with greater insulin resistance [22]. Using TIR to classify patients, we found that maintaining target TIR was more difficult in diabetics than in non-diabetics, confirming previous results showing that out of range glycemia was more prevalent in diabetics [23]. Although we hypothesized that poor control would be related to ethnicity, we found that both Asians and Arabs were equally distributed in both TIR groups.

Our finding, that use of dopamine or adrenaline was associated with poor glycemic control, is in good agreement with findings showing that higher BG levels were associated with adrenaline use [5]. Intensive glycemic management may be required in non-diabetic patients infused with high doses of catecholamines [24]. However, catecholamine infusion may be responsible for hyperglycemia in ICU patients [25].

We found that the frequency of poor glycemic control was higher in patients who underwent CABG than in those who underwent valvular surgery, a finding that may be due to the higher preoperative rate of diabetes in CABG patients. CABG was found to be more closely associated with hyperglycemia than was valvular surgery, as were wound infections (93% versus 4%) [3]. We found, however, that the acute nature of surgery was similar in both groups.

Prediction of poor glycemic control

Although potential predictors of poor glycemic control, such as baseline creatinine concentration and EF%, were similar in our patient groups, HbA1C concentration was significantly higher in Group II. High HbA1c after CABG may be associated with higher short- and long-term mortality rates [26].

Hyperglycemia associated with CPB may be due to the insulin resistance that accompanies surgical intervention, resulting in poorer patient outcomes [27]. Although we found that CPB time was higher in Group II, the difference was not statistically significant. In contrast, ACC and total anesthesia time were significantly higher in Group II. Although insulin secretion is not impaired during cardiac surgery, insulin signaling cascade in target organs is reduced, and inotropes needed during weaning from CPB affect glucose levels [27]. CPB has been shown to affect glucose control [8], with increases in inflammatory cytokines during cardiac surgery enhancing insulin resistance [10].

Postoperative parameters and complications

Lengths of stay in the ICU and hospital, as well as duration of mechanical ventilation, were all significantly higher in Group II, as well as in both non-diabetics and diabetics with low TIR. These results were consistent with findings showing that moderate glycemic control (6.6–10.0 mmol/L) in diabetic CABG patients was associated with minimal morbidity and mortality [28]. Moderate glycemic control (6.1–8.0 mmol/L) after cardiac surgery was found to reduce the duration of ventilation [29]. A 3-mmol/L increase in BG was found to be an independent predictor of deep sternal wound infection, length of stay in the hospital and mortality rate. In addition, new POAF events, blood transfusion and low cardiac output syndrome were found to correlate significantly [30], suggesting that reducing BG below 10 mmol/L appears to be an ideal goal. Maintaining BG below this concentration was associated with reductions in mortality and morbidity, whereas aggressive glycemic control (4.4–6.1 mmol/L) did not offer a superior advantage [31].

Complications related to poor glycemic control are challenging for health care practitioners. For example, we found that the occurrence of acute kidney injury (AKI) tended to be higher in Group II, similar to results showing that glycemic control after cardiac surgery was significantly associated with a reduced risk of AKI [32]. The rate of POAF events was also significantly higher in Group II, similar to findings showing that proper glycemic control could reduce the incidence of POAF after CABG, from 30% to 18% (39% risk reduction; p = 0.042) [29], and may reduce the rate of POAF-associated mortality [33]. In addition, a prospective randomized study found no differences in the rates of POAF events and wound infection between aggressive (5.0–6.6 mmol/L) and moderate (6.6–10.0 mmol/L) glycemic control [34]. We found that the rate of wound infection was significantly higher in Group II, similar to findings showing that the rate of wound infection was reduced from 2.6% to 1.0% following glycemic control for 18 months [35].

Wound infections after cardiac surgery may be reduced by antimicrobial prophylaxis, control of preoperative BG concentration, and staple avoidance in patients with a normal BMI [36]. Preoperative screening for diabetes may reduce the rates of these postoperative morbidities associated with surgical site infections [3]. We found that the rates of hypoglycemic events were similarly low in both groups, with two patients in each group experiencing hypoglycemia.

The overall in-hospital mortality rate was higher in Group II than in Group I (3.7% versus 1.2%). Outcomes may be improved by enhancing TIR in ICU settings, especially when hypoglycemia can be avoided. We found that both diabetics and non-diabetics with low TIR had similar outcomes, suggesting that diabetics with greater numbers of comorbidities may have poorer outcomes. Moreover, diabetics may benefit from higher target glucose concentrations [14].

Strengths and limitations

Utilization of the TIR as a distinguishing factor may have clinical advantages. The relatively low rate of hypoglycemia in our study may have been due to the frequency of blood sampling (hourly during the first 6 h). This high sampling rate should not confer an extra burden on the nursing staff, as arterial sampling is required for early assessment of these patients. The optimum sampling frequency has not yet been determined, although sampling every 1–2 h is common in many studies [15, 37]. The early postoperative period is usually associated with stress from the use of inotropes, as well as bleeding, predisposing to early difficulties in glucose control. This study was limited by being performed at a single center, as well as by an inability to occlude the glucose variability.

Conclusion

Patients with >80% TIR 6.0-8.1 mmol/L, whether diabetics or non-diabetics, had better outcomes than those with <80% TIR 6.0-8.1 mmol/L. The former group had a lower rate of wound infection, shorter duration of ventilation and shorter stay in the ICU. Moreover, strict glycemic control did not increase the occurrence of hypoglycemic events. Preoperatively high HbA1C appears a more likely predictor of poor glycemic control. Ethnicity had no effect on glucose control.

Recommendations and future directions

-

1)

Attempt to enhance TIR in ICU population

-

2)

HbA1C screening for all patients before cardiac surgeries.

-

3)

Hourly sampling of blood glucose

-

4)

Considering glucose variability in similar studies

Key messages

-

1)

Power of TIR to predict outcome after cardiac surgeries.

-

2)

Safety of 6.0-8.1 mmol/L target BG.

-

3)

Reduced complication in the adequately controlled group

-

4)

Power of HbA1C to predict poor control

-

5)

Ethnicity is not predictive of poor control among the studied population

-

6)

Value of hourly sampling of BG soon after cardiac surgery

Consent

The ethics review panel waived informed consent for all patients enrolled in the study. However, all study data were maintained anonymously.

Abbreviations

- ACC:

-

Aortic cross clamp

- AKI:

-

Acute kidney injury

- BG:

-

Blood glucose

- CABG:

-

Coronary artery bypass graft

- CAD:

-

Coronary artery disease

- CPB:

-

Cardiopulmonary bypass

- HbA1c:

-

Glycated hemoglobin

- POAF:

-

Postoperative atrial fibrillation

- TIR:

-

Time in range.

References

Carr JM, Sellke FW, Fey M, Doyle MJ, Krempin JA, de la Torre R, Liddicoat JR: Implementing tight glucose control after coronary artery bypass surgery.Ann Thorac Surg 2005,80(3):902–9. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.03.105

Ouattara A, Lecomte P, Le Manach Y, Landi M, Jacqueminet S, Platonov I, Bonnet N, Riou B, Coriat P: Poor intraoperative blood glucose control is associated with a worsened hospital outcome after cardiac surgery in diabetic patients.Anesthesiology 2005,103(4):687–94. 10.1097/00000542-200510000-00006

Latham R, Lancaster AD, Covington JF, Pirolo JS, Thomas CS: The association of diabetes and glucose control with surgical site infections among cardiothoracic surgery patients.Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2001, 22:607–12. 10.1086/501830

Lazar HL, Chipkin SR, Fitzgerald CA, Bao Y, Cabral H, Apstein CS: Tight glycemic control in diabetic coronary artery bypass graft patients improves perioperative outcomes and decreases recurrent ischemic events.Circulation 2004, 109:1497–502. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000121747.71054.79

Furnary AP, Gao G, Grunkemeier GL, Wu Y, Zerr KJ, Bookin SO, Starr A: Continuous insulin infusion reduces mortality in patients with diabetes undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting.J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2003, 125:1007–21. 10.1067/mtc.2003.181

van den Berghe G, Wouters P, Weekers F, Verwaest C, Bruyninckx F, Schetz M, Bouillon R: Intensive insulin therapy in the critically ill patients.N Engl J Med 2001, 345:1359–67. 10.1056/NEJMoa011300

Giakoumidakis K, Eltheni R, Patelarou E, Theologou S, Patris V, Michopanou N, Mikropoulos T, Brokalaki H: Effects of intensive glycemic control on outcomes of cardiac surgery.Heart Lung 2013,42(2):146–51. 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2012.12.007

Chaney MA, Nikolov MP, Blakeman BP, Bakhos M: Attempting to maintain normoglycemia during cardiopulmonary bypass with insulin may initiate postoperative hypoglycemia.Anesth Analg 1999, 89:1091–5. 10.1213/00000539-199911000-00004

Lehot JJ, Piriz H, Villard J, Cohen R, Guidollet J: Glucose homeostasis. Comparison between hypothermic and normothermic cardiopulmonary bypass.Chest 1992, 102:106–11. 10.1378/chest.102.1.106

Wasmuth HE, Kunz D, Graf J, Stanzel S, Purucker EA, Koch A, Lammert F: Hyperglycemia at admission to the intensive care unit is associated with elevated serum concentrations of interleukin-6 and reduced ex vivo secretion of tumor necrosis factor-alpha.Crit Care Med 2004, 32:1109–14. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000124873.05080.78

Macheda M, Rogers S, Best JD: Molecular and cellular regulation of glucose transporter (GLUT) proteins in cancer [Review].J Cell Physiol 2005, 202:654–62. 10.1002/jcp.20166

Ehtisham S, Crabtree N, Clark P, Shaw N, Barrett T: Ethnic differences in insulin resistance and body composition in United Kingdom adolescents.J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005,90(7):3963–9. Epub 2005 Apr 19 10.1210/jc.2004-2001

Krinsley JS, Meyfroidt G, Van den Berghe G, Egi M, Bellomo R: The impact of premorbid diabetic status on the relationship between the three domains of glycemic control and mortality in critically ill patients.Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2012,15(2):151–60. 10.1097/MCO.0b013e32834f0009

Krinsley JS, Egi M, Kiss A, Devendra AN, Schuetz P, Maurer PM, Bellomo R: Diabetic status and the relation of the three domains of glycemic control to mortality in critically ill patients: an international multicenter cohort study.Crit Care 2013,17(2):R37. 10.1186/cc12547

Moghissi E: Hospital management of diabetes: beyond the sliding scale.Cleve Clin J Med 2004,71(10):801–8. 10.3949/ccjm.71.10.801

Krinsley JS: Association between hyperglycemia and increased hospital mortality in a heterogeneous population of critically ill patients.Mayo Clin Proc 2003, 78:1471. 10.4065/78.12.1471

Falciglia M, Freyberg RW, Almenoff PL, D’Alessio DA, Render ML: Hyperglycemia-related mortality in critically ill patients varies with admission diagnosis.Crit Care Med 2009, 37:3001. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181b083f7

The NICE-SUGAR study investigators: Intensive versus conventional glucose control in critically ill patients.NEJM 2009, 360:1283–97.

Lazar HL, McDonnell M, Chipkin SR, Furnary AP, Engelman RM, Sadhu AR, Bridges CR, Haan CK, Svedjeholm R, Taegtmeyer H, Shemin RJ: Society of thoracic surgeons blood glucose guideline task force. The society of thoracic surgeons practice guideline series: blood glucose management during adult cardiac surgery.Ann Thorac Surg 2009,87(2):663–9. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.11.011

Hargraves JD: Glycemic control in cardiac surgery: implementing an evidence-based insulin infusion protocol.Am J Crit Care 2014,23(3):250–8. 10.4037/ajcc2014236

Pezzella AT, Holmes SD, Pritchard G, Speir AM, Ad N: Impact of perioperative glycemic control strategy on patient survival after coronary bypass surgery.Annal Thorac Surg 2014,98(4):1281–5. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.05.067

Ramachandran A, Snehalatha C, Shetty AS, Nanditha A: Trends in prevalence of diabetes in Asian countries.World J Diabetes 2012,3(6):110. 10.4239/wjd.v3.i6.110

Gauthier L, Ferguson J, Dubé AI, Nguyen PVQ, Beauchesne MF, Boutin JM: Assessment of quality of glycemic control in intensive care patients treated with an insulin infusion at a teaching hospital.Can J Diabetes 2014,38(2):139–43. 10.1016/j.jcjd.2014.01.012

Rady MY, Johnson DJ, Patel BM, Larson JS, Helmers RA: Influence of individual characteristics on outcome of glycemic control in intensive care unit patients with or without diabetes mellitus.In Mayo Clinic Proc 2005,80(12):1558–67. 10.4065/80.12.1558

Whitcomb BA, Pradhan EK, Pittas AG, Roghmann MC, Perencevich EN: Impact of admission hyperglycemia on hospital mortality in various intensive care unit populations.Crit Care Med 2005, 33:2272–7.

Halkos ME, Lattouf OM, Puskas JD, Kilgo P, Cooper WA, Morris CD, Thourani VH: Elevated preoperative hemoglobin A1c level is associated with reduced long-term survival after coronary artery bypass surgery.Ann Thorac Surg 2008,86(5):1431–7. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.06.078

Doenst T, Wijeysundera D, Karkouti K, Zechner C, Maganti M, Rao V, Borger MA: Hyperglycemia during cardiopulmonary bypass is an independent risk factor for mortality in patients undergoing cardiac surgery.J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2005,130(4):1144-e1.

Bhamidipati CM, LaPar DJ, Stukenborg GJ, Morrison CC, Kern JA, Kron IL, Ailawadi G: Superiority of moderate control of hyperglycemia to tight control in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting.J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2011,141(2):543–51. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.10.005

Leibowitz G, Raizman E, Brezis M, Glaser B, Raz I, Shapira O: Effects of moderate intensity glycemic control after cardiac surgery.Ann Thorac Surg 2010,90(6):1825–32. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.07.063

Furnary AP, Wu Y, Bookin SO: Effect of hyperglycemia and continuous intravenous insulin infusions on outcomes of cardiac surgical procedures: the Portland diabetic project.Endocr Pract 2004, 10:21–33. 10.4158/EP.10.S2.21

Lazar HL: Glycemic control during coronary artery bypass graft surgery.ISRN Cardiol 2012, 2012:292490.

Azevedo JR, Azevedo RP, Lucena LC, Costa ND, Silva WS: Impact of glycemic control on the incidence of acute kidney injury in critically ill patients: a comparison of two strategies using the RIFLE criteria.Clinics 2010,65(8):769–73.

Haga KK, McClymont KL, Clarke S, Grounds RS, Ng KY, Glyde DW, Alston RP: The effect of tight glycaemic control, during and after cardiac surgery, on patient mortality and morbidity: a systematic review and meta-analysis.J Cardiothorac Surg 2011, 6:3. 10.1186/1749-8090-6-3

Lazar HL, McDonnell MM, Chipkin S, Fitzgerald C, Bliss C, Cabral H: Effects of aggressive versus moderate glycemic control on clinical outcomes in diabetic coronary artery bypass graft patients.Ann Surg 2011,254(3):458–64. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31822c5d78

Kramer R, Groom R, Weldner D, Gallant P, Heyl B, Knapp R, Arnold A: Glycemic control and reduction of deep sternal wound infection rates: a multidisciplinary approach.Arch Surg 2008,143(5):451–6. 10.1001/archsurg.143.5.451

Trick WE, Scheckler WE, Tokars JI, Jones KC, Reppen ML, Smith EM, Jarvis WR: Modifiable risk factors associated with deep sternal site infection after coronary artery bypass grafting.J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2000,119(1):108–14. 10.1016/S0022-5223(00)70224-8

Jacobi J, Bircher N, Krinsley J, Agus M, Braithwaite SS, Deutschman C, Schunemann H: Guidelines for the use of an insulin infusionfor the management of hyperglycemia in critically ill patients.Crit Care Med 2012, 40:3251e76.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2253/15/14/prepub

Acknowledgments

This work would not have been possible without the kind support and help of many individuals and our organization. The authors thank all members of the Cardiothoracic surgery department, Heart Hospital, of Hamad Medical Corporation, Qatar, for providing necessary information regarding the project and for support. The authors also thank the members of the medical research department of Hamad Medical Corporation for their support throughout this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

ASO wrote the manuscript, designed the study and submitted the manuscript. AS, MA and YE collected data. SM provided support in the initial study design and in writing the manuscript. RS performed statistical analyses. AKT, as chair of the intensive care department, provided general support. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Omar, A.S., Salama, A., Allam, M. et al. Association of time in blood glucose range with outcomes following cardiac surgery. BMC Anesthesiol 15, 14 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2253-15-14

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2253-15-14