Abstract

Background

There is a serious public health concern regarding the emergence of carbapenem-resistant Escherichia coli (CREC). The purpose of this study is to identify the molecular characterization and risk factors of CREC in Fujian province, China.

Methods

A total of 48 CREC isolates were collected from various clinical samples. The strains were identified using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF/MS). Susceptibility to antibiotics was determined by the standard broth microdilution method. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was used to screen common drug resistance genes. Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) was used to type isolates. RT-qPCR was used to detect gene expression of acrA, acrB, and tolC. Conjugation assays were used to analyze the transferability of plasmids carrying mcr-1 or blaNDM. Risk factors for CREC infection were identified by logistic regression analysis.

Results

48 CREC strains were collected, with 81.25% producing carbapenemase (CP-CREC), and 18.75% were not producing carbapenemase (no-CP-CREC). They belonged to 21 sequence type (STs) and five unknown STs. Perianal swabs were the main sample type, with 25 patients found to have hematological malignancies. All isolates of CP-CREC were found to contain blaNDM (blaNDM−5 (n = 32), blaNDM−1 (n = 5), blaNDM−4 (n = 1), and blaNDM−13 (n = 1)), among which one isolate co-existence blaNDM−5 and blaOXA−48. Two blaNDM-positive strains, specifically blaNDM−5 and blaNDM−4, were found to co-habor mcr-1 with ST617. Conjugation assays confirmed that blaNDM−1, blaNDM−13, and most blaNDM−5(68.75%, 22/32) could be transferred between E. coli strains. Four of the 9 non-CP-CREC isolates had deletions in ompC and ompF with blaCTX−M production, while the other five showed high expression of acrA, acrB, and tolC. Antibiotics usage, antifungal treatment, detection of other pathogens (prior to CREC infection), and respiratory disease were identified as independent risk factors for CREC infection. The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve for the scoring system was 0.937. Youden’s index, with sensitivity and specificity of 0.96 and 0.78, was maximal when 2 points were scored.

Conclusions

In CP-CREC, carbapenem resistance is caused primarily by multiple types of blaNDM, while non-CP-CREC is caused by loss of porin protein or high expression of efflux pumps coupled with carrying blaCTX−M. CREC isolates were highly diverse in terms of ST, with a total of 21 STs identified. Here, we first describe a clinical strain of CREC from China both mcr-1 and blaNDM −4 with ST617. An easy-to-use scoring system was developed to diagnose CREC infections.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Escherichia coli (E.coli) is an opportunistic pathogen that can cause various infections, including UTIs, meningitis, bacteriemia, pneumonia, surgical site infections, and sepsis. Carbapenem antibiotics are highly effective against a variety of infections caused by extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing and multidrug-resistant (MDR) gram-negative bacteria. Carbapenem-resistant E.coli (CREC) is becoming more common due to the widespread use of carbapenem antibiotics. A survey conducted in Europe found that 19% of E. coli strains were classified as CREC from 2013 to 2014 [1]. The China Antimicrobial Surveillance Network (CHINET) reported that the isolation rates of CREC ranged from 0.7 to 1.9% from 2016 to 2023.

Antibiotic resistance is a global issue [2], with limited new antibiotics available to treat bacterial infections. According to the WHO, MDR pathogens, also known as ‘superbugs’, are a significant global threat, causing millions of deaths annually [3]. Carbapenems are crucial antibiotics used as a last resort for serious infections. Carbapenem resistance is mediated either by intrinsic mechanisms (such as coupled efflux pumps, AmpC overexpression, and porin loss) or by development of a carbapenemase [4]. First, transmissible carbapenemases are categorized into three classes: class A (serine carbapenemases, such as blaKPC), class B (metallo-β-lactamases, such as blaIMP, blaVIM, and blaNDM) and class D (blaOXA, such as blaOXA−23 and blaOXA−48) [5]. Second, in E. coli, AcrAB-TolC is the primary efflux pump. Research has found that AcrAB-TolC is linked to resistance against aminoglycosides, carbapenems, and other antibiotics [6]. Shiela Chetri et al., found a new link between ertapenem resistance and AcrA overexpression, as well as an increase in AcrB expression in E. coli under imipenem stress [7]. However, Howard T. H. Saw et al., found that efflux inhibitors may not enhance carbapenem effectiveness but instead could boost resistance in carbapenemase-producing organisms [8]. Lastly, a lack of certain outer membrane proteins (such as OmpF and OmpC) in E. coli can impact its response to carbapenem antibiotics. Yigit et al. [9]. found that changes in the outer membrane proteins OmpF and OmpC in Enterobacter strain 810 led to resistance to imipenem and decreased susceptibility to meropenem and cefepime.

CREC is a major clinical concern due to its resistance to all beta-lactam antibiotics and multiple resistance determinants, which limit treatment options. Polymyxin B is a last resort for treating multidrug resistant bacteria infections. A plasmid-mediated colistin mcr-1 resistance gene was found by China in 2015 [10]. Since then nine derivatives (mcr-2 to mcr-10) have been found in humans, animals, foods, and other sources [11]. While mcr is less common in clinical strains than in animal isolates, more reports of colistin-resistant carbapenemase-producing bacteria with combinations of blaNDM or blaKPC and mcr [12].

It has been shown that venous catheterization, exposure to penicillin and broad-spectrum cephalosporins, a longer hospital stay, presence of a urinary catheter, and intubation are independent risk factors for carbapenem-resistant Enterobacter cloacae infection [13, 14]. Limited data are available on the prevalence and mechanisms of CREC isolates from China. The risk factors for CRE infection have been examined in several studies [15], however, few studies have specifically assessed the risk factors for CREC acquisition.

Monitoring drug resistance in bacteria and understanding carbapenem resistance mechanisms can help improve antibiotic prescription guidelines and infection control strategies. This study analyzed the clinical and bacterial molecular characteristics of patients with CREC infections from 2021 to 2023 in order to identify risk factors. On the basis of the risk factors identified, we attempted to develop a scoring system to detect patients at-risk for CREC infection who have E. oli.

Materials and methods

Bacteria Isolates identification and clinical data collection

CREC isolates were obtained from Fujian Medical University Union Hospital (Fuzhou, China) between March 2021 and September 2023. The isolates were obtained from a variety of clinical specimens. We excluded duplicate isolates of the same species and specimen type from the same patient during the same year. For the defined CREC isolates, we evaluated susceptibility using broth microdilution and disk diffusion, interpreting the results using the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) breakpoints. Resistances to imipenem (4 µg/ml or 19 mm), meropenem (4 µg/ml or 19 mm), or ertapenem (4 µg/ml or 18 mm) were defined as CRECs. All E. coli isolates from patients meeting the inclusion criteria of the study were stored in the laboratory at -80 ◦C in cryovials containing 20% glycerol and nutrient broth for further analysis. MALDI-TOF/MS was used to identify the bacterial species of the collected isolates using Bruker Biotyper™ system (Bruker Daltonics Inc., Billerica, Massachusetts). The clinical data used in this study were retrospectively analyzed.

Resistance and virulence genes confirmation

Analyzing the gene sequence of carbapenemase confirmed the detection of carbapenemase genes (blaNDM, blaIMP, blaVIM, blaKPC, blaSME, blaGIM, blaSIM, blaIMI, blaOXA-48‐like, blaGES, and blaOXA‐181). We conducted PCR assays to detect other antibiotic-resistant genes. The presence of resistance genes includes ESBLs (blaCTX−M−1−like, blaCTX−M−2−like, blaCTX−M−8−like, blaCTX−M−9−like, and blaCTX−M−10−like ), non-ESBL genes (TEM and SHV), fluoroquinolones (qnrS, qnrA, qnrB, qepA, and gyrA), sulfonamides (sul1), tetracyclines (tetA), streptomycin (strA), aminoglycosides (ant3, aac6-IB, aac3-II, armA, and rmtB), and porin-related genes (OmpC and OmpF). Genetic analysis of virulence genes: the following 9 virulence genes (i.e. TraT, papC, afaC, iucD, hylA, ecpA, fimH, ompT, and iutA) were examined by PCR in all strains. The sequence of primers is shown in Tables S1 and S2. Sequencing of positively amplified products was performed using the Sanger sequencing method, and a comparison was made with the NCBI BLAST database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/).

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

We measured the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of antibiotics as follows: cephalosporins (cefepime, ceftazidime), β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations (cefoperazone-sulbactam, piperacillin-tazobactam), carbapenems (imipenem, meropenem), aminoglycosides (tobramycin, amikacin), tetracycline (minocycline, tigecycline), fluoroquinolones (ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin), trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole, aztreonam, and polymyxin B using the standard broth microdilution method according to CLSI. In all cases except for tigecycline, antibiotic susceptibilities were based on the CLSI document standard. FDA standards were used to determine the breakpoint for tigecycline (susceptible: MIC ≤ 2 mg/L; resistant: MIC ≥ 8 mg/L). As controls, E. coli ATCC 25,922 and P.aeruginosa ATCC 27,853 were used.

Multilocus sequence typing

We performed MLST by PCR amplification and sequencing 7 housekeeping genes: adk, fumC, gyrB, icd, mdh, purA, and recA for E. coli. The sequence of primers is shown in Table S3. The MLST database (www.mlst.net) assigned STs.

Transcriptional analysis real-time quantitative PCR

We extracted and transcribed RNA as described previously [16]. RT-qPCR was used to estimate relative gene expression of acrA, acrB, and tolC using the primer sets in Table S4. As a normalized standard, we used the 16 S rRNA gene as the normalized method. The obtained values were then normalized against those from carbapenem antibiotics susceptible strains.

Transferability of plasmids carrying mcr-1 and bla NDM

We studied the transferability of mcr-1 or blaNDM using EC600 (which has rifampicin resistance) as the recipient bacteria. A total of 600µL of recipient bacteria (EC600) and 200µL of donor bacteria were mixed and cultured in an incubator at 37 °C for about 18 h. Double-resistant MH plates containing polymyxin B or meropenem and rifampicin were used to culture suspected donor, recipient, and mixed bacteria. As a determination method, only mixed bacteria grew colonies on the double-resistant plate, while neither the recipient bacteria nor the donor bacteria did. Transconjugants expressing mcr-1 or blaNDM were confirmed by PCR.

Clinical data collection

For this study, 48 CREC isolates were collected from 48 patients. Due to missing data for 2 of the case patients, 46 cases were included in our study. The study defined a case as a patient from whom CREC was isolated in any clinical culture. At least 48 h after admission, patients with isolated CSEC from a clinical culture were considered controls. Controls were recruited in a 2:1 ratio to cases. The study matched cases and controls based on age, clinical manifestations, pathogens, hospital wards, date of admission, and other relevant factors. Cases and controls could only be included once in each study. The clinical medical record system was used to collect demographic and clinical data.

Several factors were examined as possible risk factors for the emergence of CREC, including antibiotic use (such as aminoglycosides, β-lactams, carbapenems, cephalosporins, quinolones, and polymyxin B), and invasive surgery. As well as the ECOG scores, the presence of multiple infections including in the lungs, urinary tract, blood, and abdominal cavity, was examined. We collected data on disease diagnoses, age, hospital ward, hospitalizations, outcome, invasive operation (such as PICC, catheter, and so on), co-morbidities (hypertension, diabetes, solid tumor, surgical history, cardiac diseases, disease of the urinary system, liver disease, respiratory disease, and digestive system disease) and sample origin data for all CREC isolates at the same time.

Statistical analysis

IBM SPSS ver. 21.0 statistical software (IBM Co., Armonk, NY) was used to analyze the data. In order to analyze categorical variables, frequency tables (n, %) and descriptive statistics (mean, median, standard deviation) were used. Logistic regression (Backward LR) was used for risk factor analysis (univariate and multivariate). Statistical significance was determined by the P value < 0.05.

Results

Clinical and microbiological characteristics

In this study, the detection rates of CREC from 2021 to 2023 were 3.0%, 2.8%, and 3.82%, respectively. 48 CREC isolates were collected from March 2021 to September 2023. With an age range of 3–98 years, the mean age of the patients was 46.14 years. 25 (52.08%) patients were diagnosed with hematological malignancies, 7 (18.6%) with urological malignancy, 4 (8.33%) with lung conditions, 3 (6.25%) with liver-related diseases, 3 (6.25%) with urinary-related diseases, 2 (4.16%) with acute pancreatitis, 2 (4.16%) with acute pancreatitis surgical wound infection, and 5 (10.42%) with other disease (cervical malignancy, osteoporosis and so on). Among the specimens, perianal swab (n = 12,25%), urine (n = 10, 20.83%), drainage fluid (n = 7, 14.58%), stool (n = 7, 14.558%), secretors (n = 5, 10.42%), blood (n = 4,8.33%), and sputum (n = 3, 6.25%) were procured. Of the 48 carbapenem-resistant cases, 81.25% (39/48) produced carbapenemase (carbapenemase-producing CREC, CP-CREC), while 18.75% (9/48) did not produce carbapenemase (non carbapenemase-producing CREC, non-CP-CREC). Furthermore, ESBL production was observed in 87.5% (42/48) of the isolates.

Resistance genes and virulence genes profile

A further test was performed to determine whether the CREC strains carried genes for carbapenemase. It was observed that 64.58% (31/48) of isolates carried blaNDM−5 with the higher prevalence of blaNDM−1 (10.42%, 5/48), while blaNDM−4 and blaNDM−13 were detected in 3.8% (1/48) of strains, respectively. One of 48 isolates had two carbapenem-resistance genes (blaNDM−5 and blaOXA−48) present simultaneously. We screened all the CREC strains for the presence of mcr-1, mcr-2, mcr-3, mcr-8, and mcr-9 genes.Two strains carried mcr-1 but not the other mcr genes, which coexist with blaNDM.

Moreover, bacteria also possess genes encoding resistance to antibiotics such as beta-lactams, sulfonamides, streptomycin, aminoglycosides, quinolones, and tetracycline. Among the ESBL-resistance genes positive strains (39/48,81.25%), 25 carried the blaCTXM−10, 15 carried the blaCTXM−1, 12 carried the blaCTXM−9 gene, and 7 carried the blaCTXM−9. 33.3% (16/48) of isolates had blaCTX−M and TEM genes simultaneously, along with 2.08% (1/48) of isolates that had both blaCTX−M and SHV genes. In total, 40 aminoglycoside resistance gene-positive CREC isolates were PCR positive for ant3 (10 isolate), ant3 plus aac3-II (10 isolates), aac3-II (8 isolates), aac3-II plus aac6-IB (3 isolates), ant3 plus rmtB (2 isolates), ant3, aac3-II plus rmtB (2 isolates), ant3 plus aac6-IB (2 isolates), aac6-IB, aac3-II plus rmtB (2 isolates), ant3, aac3-II, rmtB plus aac6-IB (1 isolates), ant3, aac3-II, armA plus aac6-IB (1 isolates), aac6-IB and aac3-II (1 isolates), ant3, aac6-IB and aac3-II (1 isolates), aac6-IB (1 isolates), ant3 and aac3-II (1 isolates).

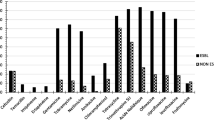

In total, 4 quinolone resistance genes were found, including 20 strains carrying gyrA (41.67%), 5 strains carrying qnrS (10.42%), 10 strains carrying both gyrA and qnrS (20.83%), 3 strains carrying both gyrA and qepA (6.25%), 1 strain carrying qnrS, gyrA, and qepA (2.08%), and 1 strain carrying qnrS, qnrB, and gyrA (2.08%). In addition, the tetA, sul1 and strA genes were detected in 38, 20, and 13 isolates, respectively (Table 1; Fig. 1).

It was found that the most prevalent virulence-associated gene was fimH (93.75%, 45/48), followed by ecpA (89.6%, 43/48), traT (60.4%,29/48), iucD (45.8%, 22/48), ompT (35.4%,17/48), afaC (4.2%,2/48), papC (2.1%,1/48) (Fig. 2).

CTX-M type ESBLs were found in all non-CP-CREC. Of the 9 non-CP-CREC isolates, 44.44% (n = 4) showed deletion in ompC and ompF porin-encoding genes (Table 2). The other five non-CP-CREC without pore-protein deletion had high expression of the efflux pumps genes acrA, acrB, and tolC (Fig. 3).

Genetic profiling and antimicrobial susceptibility analysis

In order to understand the genetic variability of the CREC, MLST was conducted. In total, 48 CREC belonged to 21 STs and five unknown STs (untypable). As shown in Table 1, the most common ST was ST410 (n = 9), followed by ST5229 (n = 4), ST38 (n = 3), ST405 (n = 3), ST648 (n = 3), ST617 (n = 2), ST10 (n = 2), ST155 (n = 2), ST69(n = 2), and ST617 (n = 2), and then by single ST isolates, including ST58, ST539, ST641, ST88, ST156, ST167, ST44, ST457, ST1730, ST297, ST361, and ST48 (Table 1).

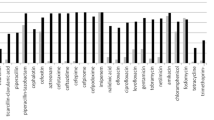

All CREC isolates showed a high-level resistance to carbapenems, with 100% resistance to cephalosporins, including cefazolin, ceftazidime, ceftriaxone, and cefepime. Other antimicrobials showed irregular susceptibility and resistance, such as piperacillin-tazobactam (97.9%), ciprofloxacin (95.8%), levofloxacin (87.5%), sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim (85.4%), gentamicin (76.2%), aztreonam (62.5%), and tobramycin (50%), whereas the highest susceptibility was recorded for polymyxin B (4.17%) (Fig. 4).

Susceptibility of CREC isolates to different antimicrobial agents. Note: CFZ: cefazolin; PMB, polymyxin B; SXT, Trimethoprim-Sulfamethoxazole; CRO, Ceftriaxone; IPM, imipenem; TZP, piperacillin-tazobactam; CIP, ciprofloxacin; LEV, levofloxacin; GEN, gentamicin; ATM, aztreonam; TOB, tobramycin; AMK, amikacin

Results of transferability of plasmids carrying mcr-1 or bla NDM

Conjugation assays confirmed that blaNDM−1, blaNDM−13, and most blaNDM−5 (68.75%, 22/32) could be transferred between E. coli strains, with an observed transfer frequency ranging from 4.19 × 10^−1 to 1.80 × 10^−4. The antibiotic susceptibility testing results showed that the transconjugants, confirmed by PCR and sequencing, were resistant to imipenem (4 mg/L). It was found that the blaNDM−4 gene carried on the plasmid in strain CREC339 could not be transferred to EC600. The plasmid carrying the mcr-1 gene from strains CREC055 and CREC339, as well as the plasmid carrying the blaNDM−5 gene from 10 CREC strains, were unsuccessfully transferred to the recipient.

Risk factors for CREC infection

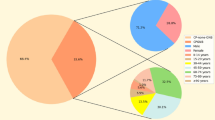

Due to incomplete case data, two patients detected by CREC infection were excluded. A comparison of the risk factors for acquiring CREC between CREC and CSEC groups is presented in Table 3, based on univariate and multivariate analyses. Using univariate conditional logistic regression analysis, it was demonstrated that hospital stay (> 30days), hospitalizations (> 3times), PICC, exposure to antibiotic agents (cephalosporin, aminoglycosides, fluoroquinolones, carbapenems, and antifungal agents), detection other pathogens (prior to CREC infection), surgical history, and respiratory disease were all risk factors for CREC infection. The multivariate conditional logistic regression analysis demonstrated that antibiotic usage (P = 0.004), antifungal use (P = 0.017), detection of other pathogens (prior to CREC infection) (P = 0.000), and respiratory disease (P = 0.016) were identified as independent risk factors for CREC infection (Table 3). After identifying these risk factors, we evaluated whether they could be used as scores to identify CREC infection. A point was assigned to each risk factor, resulting in a total score ranging from zero to four. For the purpose of determining the cutoff value for identifying cases with CREC infection, we performed receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis (Fig. 5). ROC analysis indicated high accuracy, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.937. Table 4 shows the sensitivity and specificity of each score. Youden’s index, with sensitivity and specificity values of 0.96 and 0.78, was maximal when 2 points were scored.

Discussion

It is important to know the key traits of CREC strains, such as antibiotic resistance and virulence, in order to effectively control their transmission. As far as we are aware, few studies have evaluated the risk factors for CREC infection. We aimed to investigate the molecular characterization of CREC and assess the potential risk factors for hospital-acquired CREC infection from matched case-control studies. In this study, the detection rate of CREC was generally stable at around 3.0% from 2021 to 2022, execpt for 2023. We suspect that the relative increase in the detection rate in 2023 may be related to infections co-occurring after the novel coronavirus infection.

The production of blaNDM is the major mechanism of CREC. Notable variations in carbapenemase production were observed among strains from different countries and regions. Greek and Israeli strains primarily produce carbapenemase class A KPC [17], while class D OXA-48 is most common in Europe, particularly in Spain and France [18]. NDM-producing enterobacteriaceae are primarily found in the Iran [19], Indian subcontinent [20], and China [21]. However, in Anhui Province of China, 89.4% of CREC isolates had blaKPC−2 [22]. BlaNDM was the main carbapenemase found in CREC, with blaNDM−5 being the most common variant in China [23]. In this study, the resistance gene screening indicated that the blaNDM−5 subtype was the most prevalent, followed by blaNDM−1, blaNDM−4, and blaNDM−13. These findings suggest that the predominant mechanism of carbapenem resistance in E. coli is the production of NDM-type carbapenemases. This is consistent with the literature report. There have been reports that blaNDM is carried on plasmids with a variety of replicon types [24]. In addition, our study confirmed that the majority of blaNDM (71.80%, 28/39) could be transferred between E. coli strains. Therefore, monitoring these strains should be increased to prevent the spread of resistance between strains.

Moreover, our study identified one CREC strain with ST617 carrying blaNDM−4 and mcr-1, as well as one CREC strain carrying blaNDM−5 and mcr-1. In previous studies, blaNDM−5 and mcr-1-producing E. coli were isolated from food animals in eastern China [24]. In spite of the fact that the two patients in this study were not engaged in animal husbandry, because they lived in a rural area, they might have been in contact with poultry. Additionally, this study had a few limitations. We did not obtain transconjugants that harbor mcr-1 and either blaNDM−5 or blaNDM−4. Whether blaNDM and mcr-1 can be transmitted from animals to the two patient is unclear. Further studies on the sequencing and transferability of mcr-1 and blaNDM plasmids are needed. As far as we know, the presence of both mcr-1 and blaNDM−4 in CREC has not been reported in China from patients, but it was found in a study in North Lebanon [25]. Our study represents the first reported case of clinical CREC from China harboring both mcr-1 and blaNDM−4, with ST617. Therefore, it is crucial to be aware of the potential spread of drug-resistant plasmids between animals and humans through the food chain.

According to previous studies, NDM-producing E. coli cover a wide range of sequence types, with ST167, ST410, and ST617 being found in several countries (Korea, India, South Africa, Japan, the USA, and Switzerland) [26]. A multicentre study in China found that ST167 was the most common clonal lineage of NDM-producing E. coli, followed by ST410 [27]. The most frequent ST was ST405 in CREC in Lebanon [28]. Out of 214 E. coli isolates, 16 were carbapenem resistant, with the blaNDM−5 gene as the main carbapenemase-encoding gene and ST1656 as the main ST type [29]. While our findings revealed that among the 39 strains of NDM-producing E. coli, there were 21 different sequence types, with ST410 being the most abundant, followed by ST5229. This is inconsistent with previous reports. According to our knowledge, E. coli ST5229 has been reported less frequently in China; however, in integrated and conventional farms in Korea, ST5229 was the most common ST, followed by ST101 and then ST10 [30]. Therefore, vigilant monitoring of clinical CREC transmission, along with other resistance genes is imperative.

In addition, we analyzed the remaining 9 non-CP-CREC strains and found that 7 of these strains were isolated from perianal swabs. The non-CP-CREC strains in this study included ST405 and ST38, which were exclusive to these strains. Non-CP-CREC exhibited high levels of resistance to ETP but demonstrated lower levels of resistance to MEM and IMP. Non-CP-CREC strains showed a 44.4% deletion of the ompC or ompF genes, and 100% produced blaCTX−M−10, suggesting that blaCTX−M−10 and membrane porin may be involved in carbapenem resistance. Research has found that the loss of OmpC is critically important for the phenotypic development of ertapenem-resistant and meropenem-susceptible strains, along with the expression of blaCTX−M [31]. In this study, the other 5 non-CP-CREC strains with ompC and ompF expression had high expressions of efflux pump genes acrA, acrB, and tolC. The study shows that there is a strong correlation between ertapenem resistance and AcrA over-expression [32]. BlaCTX−M−10 and the high expression of efflux pumps may contribute to the drug resistance mechanisms of these 5 strains, but further research is needed to determine the specific mechanism involved.

In addition to analyzing the molecular characteristics of CREC, we further analyzed the risk factors of CREC infection. A previous report found that CREC were mainly isolated from urine samples of NDM-producing E.coli around the world [33], rather than from perianal swabs in this study. Perhaps this is due to the fact that most of the patients in this study were hematology patients. The univariate analyses revealed 13 variables that were significantly different between the case (CREC) and control (CSEC) groups, all of which were associated with the CREC infection. PICC seems to be specific to this population since other risk factors are consistent with other reports [34]. This may be related to the high proportion of patients with blood diseases in this study.

Clinical case data suggest that most patients in the CREC group had received antibiotics before the CREC infection was detected, while only a minority had received antibiotics in the CSEC group. It may be because of this that CREC strains frequently harbor resistance genes to various classes of antibiotics. There were 26 strains with resistance genes for carbapenemase, aminoglycoside, quinolone, sulfonamide, and tetracycline; and six strains with resistance genes for carbapenems, aminoglycosides, quinolones, sulfonamides, and tetracycline. As a result, most CREC isolates showed high levels of resistance to carbapenems, cephalosporins, β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitors, aminoglycosides, and fluoroquinolones, except for amikacin and polymyxin B. It poses a major challenge for clinical treatments of CREC infection. To our knowledge, in addition to inhibiting bacterial growth, the combined use of multiple antimicrobial regimens could also lead to mutations and drug resistance because selective antibiotics can exert pressure on the microbiome [35, 36], especially with the exposure to broad-spectrum antibiotics, such as aminoglycosides and carbapenems, which have been attributed to the emergence of CREC. Due to this, instead of using broad spectrum antibiotics to prevent in-hospital mortality from rising CREC infections, we applied antibiotics according to the results of antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

Our study shows that antibiotics usage, antifungal treatment, detection of other pathogens (prior to CREC infection), and respiratory disease were identified as independent risk factors for CREC infection. Unlike other studies, respiratory disease was shown to be an independent risk factor in this study. Studies have found that if respiratory disease is the underlying illness, it may protect against CRKP infection [37], whereas if it is a comorbidity, it may have the opposite effect [38]. The different genotypes carried by strains and the population differences may be important factors in determining whether respiratory diseases are independent risk factors. In addition, our results show that patients with CREC infection have a higher ECOG score and a worse prognosis than those with CSEC infection. Therefore, it is necessary to build predictive models to quickly identify CREC infections. In this study, a scoring system was developed that assigns points based on four independent risk factors. It seems that the system is accurate, with an AUROC of 0.937, and a maximal Youden’s index of 2 points was obtained. A score system like this may be useful for identifying patients at risk of infection with CREC. To prevent the spread of CREC, more rigorous infection control measures must be implemented, such as antibiotic stewardship and timely investigation of epidemiology data.

The present study is subject to certain limitations. Firstly, although we tested numerous drug resistance genes in the strains, we did not conduct whole-genome sequencing. This omission resulted in a lack of plasmid data and hindered our ability to identify other uncommon resistance mechanisms. Future research will address this limitation by exploring the genetic characteristics of resistance genes, including their chromosomal or plasmid locations, homology characteristics, and insights into the evolutionary and developmental patterns of the strains over the three-year period. In addition, this study has a small sample size and is conducted at a single center. There is still a need to confirm these findings in multicenter, large-sample, randomized controlled trials.

Conclusion

Our study found that CREC isolates were resistant to most antibiotics, primarily due to NDM-related mechanisms. The isolates exhibited high sequence type diversity, with ST410 being the most common, followed by ST5229. Notably, we first describe a clinical CREC strain carrying both mcr-1 and blaNDM−4 from China. Vigilance is crucial to prevent the spread of drug-resistant plasmids from animals to humans through the food chain. Antibiotic usage, antifungal treatment, detection of other pathogens (prior to CREC infection), and respiratory disease were identified as independent risk factors for CREC infection. Using the results, we developed a simple scoring system to identify CREC infections with the sensitivity of 96% and specificity of 78% when scores are ≥ 2 points.This indicated the monitoring of this isolate should be enhanced.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- E.coli :

-

Escherichia coli

- CREC:

-

Carbapenem-resistant E.coli

- non-CP-CREC:

-

Non carbapenemase-producing CREC

- CP-CREC:

-

Carbapenemase-producing CREC

- CSEC:

-

Carbapenem sensitive Escherichia coli

- ESBLs:

-

Extended-spectrumβ-lactamases

- PMQR:

-

Plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance

- MLST:

-

Multilocus sequence typing

- STs:

-

Sequence type

- CHINET:

-

China Antimicrobial Surveillance Network

- PICC:

-

Peripherally inserted central catheter

- MIC:

-

Minimum inhibitory concentration

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

References

Hajo G, Corinna G, Barbara A, et al. Occurrence of carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli in the European survey of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (EuSCAPE): a prospective, multinational study. Lancet Infect Dis. 17(2):1–18.

Niamh C, Louise OC, Bláthnaid M, et al. Hospital effluent: a reservoir for carbapenemase-producing enterobacterales? Sci Total Environ. 2019;672:618–24

David EB, Steven B, David S, et al. Antimicrobial resistance and the role of vaccines. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115:51.

Elena S, Monika M, Carlos JT-C, et al. Molecular surveillance of carbapenemase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa at three medical centres in Cologne, Germany. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2020;8:1–8.

Shigeyuki N, Mari M, Kiyoko T, et al. Detection of IMP metallo-β-lactamase in carbapenem-nonsusceptible Enterobacteriaceae and non-glucose-fermenting gram-negative rods by immunochromatography assay. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51(6):1762–8.

Hiroshi N, Jean-Marie P. Broad-specificity efflux pumps and their role in multidrug resistance of Gram-negative bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2011;36(2):340–63.

Shiela C, Deepshikha B, Deepjyoti P, et al. AcrAB-TolC efflux pump system plays a role in carbapenem non-susceptibility in Escherichia coli. BMC Microbiol. 2019;19(1):1–9.

Howard THS, Mark AW, Shazad M, et al. Inactivation or inhibition of AcrAB-TolC increases resistance of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae to carbapenems. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016;71(6):1510–9.

Yigit H, Anderson G, Biddle J, et al. Carbapenem resistance in a clinical isolate of Enterobacter aerogenes is associated with decreased expression of OmpF and OmpC porin analogs. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46(12):3817–22.

Liu Y, Wang Y, Walsh T, et al. Emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mechanism MCR-1 in animals and human beings in China: a microbiological and molecular biological study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16(2):161–8.

Kigen C, Muraya A, Wachira J, et al. The first report of the mobile colistin resistance gene, mcr-10.1, in Kenya and a novel mutation in the gene (S244T) in a colistin-resistant clinical isolate. Microbiol Spectr. 2024;12(2):e01855–23.

Fan R, Li C, Duan R, et al. Retrospective screening and analysis of mcr-1 and blaNDM in Gram-negative Bacteria in China, 2010–2019. Front Microbiol. 2020;11(121):1–8.

Yuansu J, Xiaojiong J, Yun XJIDR. Risk factors with the development of infection with tigecycline- and carbapenem-resistant Enterobacter cloacae. Infect Drug Resist. 2019;12:667–74.

Nobuyuki T, Aki H, Akane M, et al. Molecular epidemiological analysis and risk factors for acquisition of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacter cloacae complex in a Japanese university hospital. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2019;8(126):1–10.

Fang P, Gao K, Yang J, et al. Clinical characteristics and risk factors for neonatal bloodstream infection due to carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: a single-centre Chinese retrospective study. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2024;37:28–36.

Xu X, Zhu R, Lian S, et al. Risk factors and molecular mechanism of Polymyxin B Resistance in Carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from a Tertiary Hospital in Fujian, China. Infect Drug Resist. 2022;15:7485–94.

Grundmann H, Glasner C, Albiger B, et al. Occurrence of carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli in the European survey of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (EuSCAPE): a prospective, multinational study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17(2):153–63.

Huang J, Lv C, Li M, et al. Carbapenem-resistant Escherichia coli exhibit diverse spatiotemporal epidemiological characteristics across the globe. Commun Biol. 2024;7(1):51.

Haeili M, Barmudeh S, Omrani M, et al. Whole-genome sequence analysis of clinically isolated carbapenem resistant Escherichia coli from Iran. BMC Microbiol. 2023;23(1):49.

Dortet L, Poirel L, Nordmann PJBR. I. Worldwide dissemination of the NDM-type carbapenemases in Gram-negative bacteria. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:249856.

Huang H, Dong N, Shu L, et al. Colistin-resistance gene mcr in clinical carbapenem-resistant strains in China, 2014–2019. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9(1):237–45.

Hameed M, Chen Y, Wang Y, et al. Epidemiological characterization of Colistin and Carbapenem Resistant Enterobacteriaceae in a Tertiary: A Hospital from Anhui Province. Infect Drug Resist. 2021;14:1325–33.

Zhang Y, Wang Q, Yin Y, et al. Epidemiology of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae infections: report from the China CRE Network. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2018;62(2):e01882–17.

Jiangang M, Wei Z, Jing W, et al. Large-scale studies on antimicrobial resistance and molecular characterization of Escherichia coli from food animals in developed areas of Eastern China. Microbiol Spectr. 2022;10(4):e02015–22.

Al-Bayssari C, Nawfal Dagher T, El Hamoui S, et al. Carbapenem and colistin-resistant bacteria in North Lebanon: coexistence of mcr-1 and NDM-4 genes in Escherichia coli. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2021;15(7):934–42.

Peterhans S, Stevens M, Nüesch-Inderbinen M, et al. First report of a bla-harbouring Escherichia coli ST167 isolated from a wound infection in a dog in Switzerland. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2018;15:226–7.

Zhang R, Liu L, Zhou H, et al. Nationwide surveillance of clinical carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) strains in China. EBio Med. 2017;19:98–106.

Dagher C, Salloum T, Alousi S, et al. Molecular characterization of Carbapenem resistant Escherichia coli recovered from a tertiary hospital in Lebanon. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(9):e0203323.

Ding Y, Zhuang H, Zhou J, et al. Epidemiology and genetic characteristics of Carbapenem-Resistant Escherichia coli in Chinese Intensive Care Unit analyzed by whole-genome sequencing: a prospective observational study. Microbiol Spectr. 2023;11(2):e04010–22.

Kwang Won S, Kyung-Hyo D, Chang Min J, et al. Comparative genetic characterisation of third-generation cephalosporin-resistant Escherichia coli isolated from integrated and conventional pig farm in Korea. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2023;34(0):74–82.

Cody AB, Raymond B Sarahmb, et al. Diverse role of blaCTX-M and Porins in Mediating Ertapenem Resistance among Carbapenem-Resistant enterobacterales. Antibiot (Basel). 2024;13(2):1–19.

Chetri S, Bhowmik D. AcrAB-TolC efflux pump system plays a role in carbapenem non-susceptibility in Escherichia coli. BMC Microbiol. 2019;19(1):210.

Masoud D, Somayeh Y, Bahareh H, et al. Frequency distribution, genotypes and prevalent sequence types of New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli among clinical isolates around the world: a review. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2019;19:284–93.

Xia C, Ximao W, Zhiping J, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales (CRE) infection among hematological malignancies patients with CRE intestinal colonization. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2023;22(1):1–10.

Milena M, Renee M, Michaelm A, et al. Correlations of antibiotic use and carbapenem resistance in enterobacteriaceae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57(10):5131–33.

Ping Y, Yunbo C, Saiping J, et al. Association between antibiotic consumption and the rate of carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacteria from China based on 153 tertiary hospitals data in 2014. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2018;7(137):1–7.

Bing Z, Yingxin D. Molecular epidemiology and risk factors of Carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae infections in Eastern China. Front Microbiol. 2017;8(1061):1061–72.

L M D C AL, K S N, et al. Nosocomial infections with metallo-beta-lactamase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa: molecular epidemiology, risk factors, clinical features and outcomes. J Hosp Infect. 2014;87(4):234–40.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by Fujian Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (2021J05047).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study design: Yingping Cao and Xiaohong Xu. Study conduct: Siyan Lian, Chang Liu and Meili Cai. Data collection: Siyan Lian and Chang Liu. Data analysis: Meili Cai and Xiaohong Xu. Data interpretation: Chang Liu and Meili Cai. Drafting manuscript: Xiaohong Xu. Revising manuscript content: Yingping Cao and Xiaohong Xu. Approving the final version of the manuscript: Yingping Cao and Xiaohong Xu. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Medical Ethics Committee of Fujian Medical University Union Hospital (2024KY077) thoroughly reviewed and granted approval for all procedures pertaining to human subjects, including individuals, medical records, human samples, and clinical isolates, in this study. We affirm that the execution of this study adhered to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lian, S., Liu, C., Cai, M. et al. Risk factors and molecular characterization of carbapenem resistant Escherichia coli recovered from a tertiary hospital in Fujian, China from 2021 to 2023. BMC Microbiol 24, 374 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-024-03525-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-024-03525-9