Abstract

Background

Foetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD) is the leading preventable cause of nongenetic mental disability. Given the patient care pathway, the General Practitioner (GP) is in the front line of prevention and identification of FASD. Acknowledging the importance of the prevalence of FASD, general practitioners are in the front line both for the detection and diagnosis of FASD and for the message of prevention to women of childbearing age as well as for the follow-up.

Objectives

The main objective of the scoping review was to propose a reference for interventions that can be implemented by a GP with women of childbearing age, their partners and patients with FASD. The final aim of this review is to contribute to the improvement of knowledge and quality of care of patients with FASD.

Methods

A scoping review was performed using databases of peer-reviewed articles following PRISMA guidelines. The search strategy was based on the selection and consultation of articles on five digital resources. The advanced search of these publications was established using the keywords for different variations of FASD: "fetal alcohol syndrome," "fetal alcohol spectrum disorder," "general medicine," "primary care," "primary care"; searched in French and English.

Results

Twenty-three articles meeting the search criteria were selected. The interventions of GPs in the management of patients with FASD are multiple: prevention, identification, diagnosis, follow-up, education, and the role of coordinator for patients, their families, and pregnant women and their partners. FASD seems still underdiagnosed.

Conclusion

The interventions of GPs in the management of patients with FASD are comprehensive: prevention, identification, diagnosis, follow-up, education, and the role of coordinator for patients, their families, and pregnant women and their partners.

Prevention interventions would decrease the incidence of FASD, thereby reducing the incidence of mental retardation, developmental delays, and social, educational and legal issues.

A further study with a cluster randomized trial with a group of primary care practitioners trained in screening for alcohol use during pregnancy would be useful to measure the impact of training on the alcohol use of women of childbearing age and on the clinical status of their children.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Background

The harmful effects of alcohol consumption in the prenatal period have been recognized and studied for half a century [1, 2]. Prenatal alcohol exposure causes a range of disorders of varying severity, including prematurity, intrauterine growth retardation, fetal loss and stillbirth [3].

The most comprehensive category is Fetal Alcohol Syndrome, which includes growth retardation, craniofacial dysmorphia and neurodevelopmental disorders.

Another category is Alcohol-Related Neurodevelopmental Disorder (ARND), which manifests itself in psycho-affective and socialization disorders, with difficulties in social interaction, and adjustment disorders linked to problems of memory, attention or hyperactive behavior.

Finally, the last category includes alcohol-related birth defects (ARBD), such as cardiac and musculoskeletal malformations, complete [4].

Of all the categories that make up FASD, ARND is the most common, and FAS probably represents only 5–7% of FASD.

Fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS) is the first described and best known FASD. It is sometimes considered the most severe form [5]. FAS is the leading cause of congenital nongenetic mental disability and social maladjustment in children. It is entirely preventable [6, 7]. It is the only form of FASD with an International Classification of Diseases (ICD) code: Q86.0 in the ICD-10 and LD2F.00 in the ICD-11 [8]. The diagnosis is primarily clinical (Table 1).

Patients with FAS present a characteristic dysmorphic feature because maternal alcohol use during the first trimester of pregnancy disrupts normal brain and facial development of the fetus.

There are also partial forms of FAS, resulting in learning difficulties and/or impaired social adaptation (school failure, conduct disorders, delinquency, incarceration, marginality and substance abuse in adolescence) [9].

The generic term FASD is used to group all these symptomatic forms in which prenatal alcohol exposure is the primary aetiology.

Confirmation of prenatal alcohol exposure is necessary for the diagnosis of FASD.

"The diagnosis of FASD without FAS thus remains a syndromic diagnosis that associates proven and symptomatic neurocognitive deficits with prenatal alcohol exposure (PAE) in the absence of other detectable neurodevelopmental diseases" [10].

The severity of FASD is linked to the level of brain damage.

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders V (DSM-5) terms are not listed as diagnostic conditions in the defined criteria, although they are useful for classification [11] (Table 2).

The DSM–5 includes the Neurobehavioral Disorder Associated with Prenatal Alcohol Exposure (ND-PAE) regardless of the presence or absence of the physical effects of prenatal alcohol exposure. People who meet the criteria for an FASD diagnosis according to the IOM may also meet the criteria for ND-PAE. Thus, the neurodevelopmental deficits encountered in FASD are not pathognomonic [12]. However, diagnostic guidelines and a 4-digit code have been established that emphasize neurodevelopmental assessment [13,14,15]. The prevalence of FASD is 7.7‰ of births worldwide, with an extrapolation for France of 7,700 cases of births per year. ARND is ten times more common than FAS [16].

FASD is a common medical situation, included in primary care. However FASD remained largely underdiagnosed. Inadequate diagnostic practices might also play a role in prevalence and incidence rates, including miscarriages or stillbirths due to prenatal alcohol consumption [17].

Acknowledging the importance of the prevalence of FASD, general practitioners are in the front line both for the detection and diagnosis of FASD and for the message of prevention to women of childbearing age [18, 19] as well as for the follow-up [20,21,22,23,24]. In contrast to another form of neurodevelopmental disorder, such as autism spectrum disorder, articles published in peer-reviewed journals related to the prevention actions of FASD by the general practitioner have not yet been included in a scoping review [25].

The main objective of the literature review was to identify interventions that can be implemented by a general practitioner with women of childbearing age, their partners and patients with FASD.

Methods

A scoping review was performed using databases of peer-reviewed articles following PRISMA guidelines for writing and reading systematic reviews and meta-analyses [26]

The search strategy was based on the selection and consultation of articles on the digital resources PsycINFO, Medline, PubMed and Cairn, complemented by a search in Google Scholar. The advanced search of these publications was established using the keywords for different variations of FASD: "fetal alcohol syndrome”, "fetal alcohol spectrum disorder”, “family medicine”, "general medicine", "primary care" or "primary care" searched in French and English.

Inclusion criteria:

-

- Articles concerning family medicine, general medicine or primary care published in peer-reviewed journals

-

- Articles concerning FAS or FASD

-

- Articles in French or English

-

- No publication deadline

Noninclusion criteria:

-

- Gray literature (i.e.: books, websites)

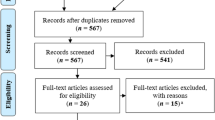

The selection process is summarized in Fig. 1.

The last search date was March 9, 2022.

SL reviewed all article titles and abstracts and selected those eligible for full-text review. MS checked the eligibility of full-text articles. SL and MS discussed the discrepancies to arrive at the final list. Articles were categorized according to the chosen plan for this work: prevention, identification/screening, diagnosis, and management of patients with fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. SL created a data collection form and tested it on three articles.

Their analysis was conducted using unstructured thematic qualitative analysis.

Results

Twenty-three articles meeting the search criteria were selected.

The result of the scoping review process are summarized in Fig. 2.

The results of this scoping review are presented in a tabular form, summarizing the main findings (Table 3). They were further classified into subgroups according to their main theme: prevention, detection-screening, diagnosis, intervention, and therapeutics.

Discussion

The articles agreed that alcohol exposure during pregnancy and its consequences were a major clinical public health problem. Given the front-line role of the general practitioner, they had a primary role in the management of FASD, from prevention to follow-up of affected individuals.

The interventions of the general practitioner were multiple, ranging from prevention (with pregnant women and women of childbearing age), identification, diagnosis, follow-up, education (patient/family/relatives), to coordination of multidisciplinary care (specialized medical, paramedical, social, educational).

The current studies and recommendations were exclusively from English-speaking countries. With regard to this organization, the general practitioner is theoretically the first line of care for people with FASD.

However, several propositions of intervention that can be implemented in general practice have emerged on the basis of the experience of North American and Australian practitioners.

The most relevant screening and diagnostic tools for the prevention and care of patients with fetal alcohol spectrum disorder are grouped together within Additional file 1.

Prevention and detection

As a front-line actor, the general practitioner has a major role in the primary prevention of fetal alcohol syndrome for pregnant women but also for women of childbearing age and their partners. Exposure to alcohol during the early first trimester is the most harmful period for the baby. Prevention before pregnancy is essential, especially since most pregnancies are discovered after 6 weeks of amenorrhea [19]. Women who had already had a child with FASD were a particularly high-risk population and required special support [20, 21, 33]. Prevention programs have shown their effectiveness [27]. This could involve identifying women at risk of drinking alcohol during pregnancy at an early stage and offering them motivational talks about alcohol consumption and appropriate and effective contraception [19].

Early detection and brief intervention around alcohol consumption is to be favored in the general population, but more particularly among women who want to become pregnant and pregnant women. The same applies to the adult population and the elderly, among whom the prevalence of FASD remains high.

To help with this task, the Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder Resource Center at the University Hospital of La Réunion, in collaboration with the Père Favron Foundation, is raising awareness among general practitioners and other healthcare professionals of the warning signs that may indicate a disorder. Figure 3.

Diagnosis

Early diagnosis is important to minimize the consequences for the child [39]. To this end, 4 tools are available to assist in the assessment of alcohol consumption: CRAFFT (for adolescents) [18, 39], the "modified CAGE" (T-ACE) [28], the TWEAK [42] for pregnant or nonpregnant women, the AUDIT (Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test) [39].

The T-ACE is a 4-item questionnaire (Tolerance, Annoyance, Cessation, Awakening) developed specifically for obstetric practice [42]. It deals indirectly with alcohol consumption since it asks about tolerance to the effects of alcohol, the psychological consequences of consumption and the opinion of the entourage on this consumption.

For GP’s daily practice, we would recommend the use of a clinical assessment as promoted within the Canadian Guidelines for diagnosis of FASD across lifespan published in 2016 (update of the 2005 guidelines) incorporating new evidence and improved understanding of FASD diagnosis.

Although from a pathophysiological point of view there are differences between the subtypes of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder, it turns out that in clinical practice it is difficult for general practitioners to identify these differences.

These tools could be made more accessible for general practitioners using an app or online website.

Even if, as in France, there are recommendations on strategies for identifying FASD, these do not take into account the particularities of the practice of the general practitioner [9]. In the long term, it would be useful to propose a guide of international recommendations for general practitioners to make an early diagnosis possible and thus allow a more favorable evolutionary trajectory [18].

Follow-up

A good physician–patient relationship is the key to the effectiveness of care for this population, with a global vision of the issues of these patients (socio-economic, communication, family, notion of non-guilt) [20]. The general practitioner must therefore take into account these different determinants to optimize his relationship with the patient (better adherence to follow-up and better therapeutic alliance).

Education

Therapeutic education is aimed at pregnant women and women of childbearing age [21], at patients with FASD, and at families and close relatives (education concerning alcohol consumption and its impact during pregnancy). Binge drinking is the most common pattern of drinking among pregnant women (more than 4–5 drinks per day) [19]. It results in a spike in blood alcohol levels that have more consequences than the same amount of alcohol consumed over a longer period of time [20]. The general practitioner can assess the risk of binge drinking in pregnant women and women of childbearing age to avoid or reduce its deleterious consequences on the child.

The family has an influential role in modeling adolescent drinking [20]. Special consideration should be given to mothers of children with FASD, as they are at risk of continuing to drink during a new pregnancy [21].

In this same population, the general practitioner must make the family and close relatives aware of the effects of alcohol on pregnancy so that they do not falsely trivialize the consumption of even small amounts of alcohol. This would help to avoid alcohol consumption during pregnancy.

In the case of FASD, the general practitioner should try with the patient's consent to involve the family circle as much as possible: discuss the patient's current situation and involve them in the process of supporting their relative. The family could thus accompany the patient in the care process and support the follow-up.

Education (teaching and awareness) involves all the actors who intervene in the care of the patient with FASD (medical specialists, paramedics including speech therapists [39], police services, social workers) [6], and schools [39]; hence, the coordinating role of general medicine is as follows:

Role of coordinator

The general practitioner, by virtue of his or her skills and functions in the health care system [43], is the most appropriate person in a patient-centred approach to have a global vision to best coordinate the care pathway of patients and their child with FASD (multi-professional and multi-disciplinary medical/paramedical/social/justice care). It would have the role of expert and informant on the appropriate care system for the patient and family [39].

Extending the reflections of the article [39], screening for FASD risk is not yet systematic in general practice. Physicians cite discomfort in discussing the topic, lack of time, inadequate remuneration, fear of stigma, lack of information on how to conduct a discussion about alcohol use, and lack of knowledge about intervention strategies.

Given these remarks, several ideas could address these limitations:

There is a specific quotation (with a specific remuneration) that could be extended to the management of patients with FASD given the complexity and the need for time to carry out this screening/prevention/diagnosis/coordination/follow-up work. Indeed, the feasibility of such complex quality management over a standard consultation time is not feasible. For example, in France, general personnel consults last 16 min on average according to the Direction de la recherche des études de l'évaluation et des statistiques (DREES) of the Ministry of Health [44]. Remuneration in line with the time invested could thus enable doctors to provide quality care to patients with FASD, particularly in regions lacking specialized networks.

In another declarative survey by the DREES [45], 61% of general practitioners indicated that they systematically asked pregnant women about their alcohol consumption, and 77% of general practitioners recommended that their pregnant patients stop drinking altogether during their pregnancy. However, this study showed that 43% considered an occasional drink of alcohol to be an acceptable risk and that for 18%, this level of consumption was safe for pregnancy [45]. In 2017, 65.9% of mothers reported that the physician or midwife who attended them during their last pregnancy informed them of the potential impact of alcohol use on the pregnancy and their child [7]. Only 29.3% of women reported that they had been advised not to drink alcohol during pregnancy [46], yet the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) and the American Congress of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) recommend that all women of childbearing age be educated about alcohol use to prevent its effects on the newborn [21].

The results of this review raise the question of training physicians during their university and postgraduate courses on the complex management of patients exposed to or suffering from FASD. A better knowledge of the subject would improve their ability to deal with it, promote awareness, and allow for better management (screening / prevention / diagnosis / follow-up / coordination / knowledge of the network). University training is probably currently minimized given the prevalence of this clinical situation.

The Canadian experience of an interdisciplinary clinic for diagnosing FASD is an interesting approach [41]. The establishment of a resource center with a team in charge of referral (university hospitals, medical-psychological centers, medical-psychological-pedagogical centers, medical-social institutions, so-called "ordinary" or specialised schools), coordination and follow-up of the care pathway is probably an appropriate response to the issues of prevention and care of people exposed to or affected by FASD.

The general practitioner ideally has a coordinating role in the management of patients with FASD, but given the current context (lack of time in consultation, lack of visibility of available local actors, lack of specific knowledge on the subject) [39], a single platform would make it possible to assist him/her in the orientation and coordination of the management of these patients.

As was done in Canada in 2008, a qualitative study of the feasibility and acceptability of these interventions could explore the point of view of general practitioners in other countries. Knowing the needs and practices of primary care practitioners would allow for more tailored training for the prevention and identification/screening of alcohol risk in pregnant or childbearing women and their partners.

A cluster randomized trial with a group of primary care practitioners trained in screening for alcohol use during pregnancy versus usual care by untrained primary care practitioners would measure the impact of training on the alcohol use of women of childbearing age and the clinical status of their children born in each group.

The limitations of this literature review are the small number of articles selected, the heterogeneity, and the insufficient level of proof of the studies selected. There are certainly prevention and detection actions that have been evaluated but not published in a scientific journal. Access to grey literature is difficult, which limits the completeness necessary for this literature review.

Conclusions

The interventions of GPs in the management of patients with FASD are global: prevention, identification, diagnosis, follow-up, education, and the role of coordinator for patients, their families, and pregnant women and their partners.

Prevention interventions would decrease the incidence of FASD, thereby reducing the incidence of mental retardation, developmental delays, and social, educational and legal issues.

GPs would be better equipped and better informed both on the subject and on the networks to optimize the coordination of these complex pathways, while remaining the main interlocutor.

A further study with a cluster randomized trial with a group of primary care practitioners trained in screening for alcohol use during pregnancy would be useful to measure the impact of training on the alcohol use of women of childbearing age and on the clinical status of their children.

Practical implications

This scoping review highlights the available options for interventions of general practitioners from a global perspective, indicating the importance of clinical tools for everyday practice.

Availability of data and materials

As this is a scoping review, we do not have a personal database. The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AAFP:

-

American Academy of Family Physicians

- ACOG:

-

American Congress of Obstetrics and Gynecology

- DREES:

-

Direction de la recherche des études de l'évaluation et des statistiques

- DSM-5:

-

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders V

- FAS:

-

Fetal Alcohol Syndrome

- FASD:

-

Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder

- GP:

-

General practitioner

- IOM:

-

Institute of Medicine

- ICD:

-

International Classification of Diseases code

- ND-PAE:

-

Neurobehavioral disorder associated with prenatal alcohol exposure

- PAE:

-

Prenatal alcohol exposure

References

Jones KL, Smith DW. Recognition of the fetal alcohol syndrome in early infancy. Lancet. 1973;302(7836):999–1001.

Lemoine P, et al. Les Enfants des parents alcholiques: anomalies observes a propos de 127 cas [The children of alcoholic parents: anomalies observed in 127 cases]. Quert Med. 1968;8:476–82.

Patra J, Bakker R, Irving H, Jaddoe VWV, Malini S, Rehm J. Dose-response relationship between alcohol consumption before and during pregnancy and the risks of low birth weight, preterm birth and small-size-for-gestational age (SGA) – A systematic review and meta-analyses. BJOG. 2011;118(12):1411–21.

Brown JM, Bland R, Jonsson E, Greenshaw AJ. The standardization of diagnostic criteria for fetal alcohol Spectrum disorder (FASD): implications for research, clinical practice and population health. Can J Psychiatry. 2019;64(3):169–76.

INSERM Collective Expertise Centre. Alcohol: Health effects. In: INSERM Collective Expert Reports [Internet]. Paris: Institut national de la santé et de la recherche médicale; 2000. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK7116/. Accessed 21 Aug 2021.

George MA, Hardy C. Addressing FASD in British Columbia, Canada: analysis of funding proposals. J Popul Ther Clin Pharmacol. 2014;21(3):e338-345.

Consommation d’alcool, de tabac ou de cannabis au cours de la grossesse – Académie nationale de médecine | Une institution dans son temps. https://www.academie-medecine.fr/consommation-dalcool-de-tabac-ou-de-cannabis-au-cours-de-la-grossesse/. Accessed 21 Aug 2021.

World Health Organization. ICD-10: international statistical classification of diseases and related health problems: tenth revision. World Health Organization. http://id.who.int/icd/entity/362980699 (2004). Accessed 13 May 2021.

Haute Autorité de Santé. Troubles causés par l’alcoolisation fœtale : repérage https://www.has-sante.fr/jcms/c_1636956/fr/troubles-causes-par-l-alcoolisation-foetale-reperage (2013). Accessed 21 Aug 2021.

Germanaud D, Toutain S. Exposition prénatale à l’alcool et troubles causés par l’alcoolisation fœtale. Contraste. 2017;46:39.

Stratton K, Howe C, Battaglia F. Fetal Alcohol Syndrome: Diagnosis, Epidemiology, Prevention, and Treatment. The Institute of Medicine Report. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1996.

Société canadienne de pédiatrie comité de la santé des P nations des Inuits et des Métis. L’ensemble des troubles causés par l’alcoolisation fœtale : Mise à jour diagnostique. Paediatr Child Health. 2010;15(7):457–8.

Astley SJ. Diagnosing the full spectrum of fetal alcohol-exposed individuals: introducing the 4-digit diagnostic code. Alcohol Alcohol. 2000;35(4):400–10.

Chudley AE. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder: Canadian guidelines for diagnosis. Can Med Assoc J. 2005;172(5_suppl):S1-21.

Cook JL, Green CR, Lilley CM, Anderson SM, Baldwin ME, Chudley AE, et al. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder: a guideline for diagnosis across the lifespan. Can Med Assoc J. 2016;188(3):191–7.

Popova S, Charness ME, Burd L, Crawford A, Hoyme HE, Mukherjee RAS, Riley EP, Elliott EJ. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2023;9(1):11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-023-00420-x. (PMID: 36823161).

Jacobsen B, Lindemann C, Petzina R, Verthein U. The universal and primary prevention of foetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD): a systematic review. Journal of Prevention. 2022;43(3):297–316.

Loock C. Identifying fetal alcohol spectrum disorder in primary care. Can Med Assoc J. 2005;172(5):628–30.

Floyd RL, Ebrahim SH, Boyle CA. Observations from the CDC: Preventing Alcohol-Exposed Pregnancies among Women of Childbearing Age: The Necessity of a Preconceptional Approach. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 1999;8(6):733–6.

Masotti P, Szala-Meneok K, Selby P, Ranford J, Van Koughnett A. Urban FASD interventions: bridging the cultural gap between Aboriginal women and primary care physicians. J FAS Int. 2003;1(17):1–8.

Zoorob R, Snell H, Kihlberg C, Senturias Y. Screening and Brief Intervention for Risky Alcohol Use. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2014;44(4):82–7.

Davis PM, Carr TL, La CB. Needs assessment and current practice of alcohol risk assessment of pregnant women and women of childbearing age by primary health care professionals. Can J Clin Pharmacol J Can Pharmacol Clin. 2008;15(2):e214-222.

Masotti P, Longstaffe S, Gammon H, Isbister J, Maxwell B, Hanlon-Dearman A. Integrating care for individuals with FASD: results from a multi-stakeholder symposium. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15(1):457.

Tough SC, Ediger K, Hicks M, Clarke M. Rural-urban differences in provider practice related to preconception counselling and fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Can J Rural Med. 2008;13(4):180–8.

Sobieski M, Sobieska A, Sekułowicz M, et al. Tools for early screening of autism spectrum disorders in primary health care – a scoping review. BMC Prim Care. 2022;23:46. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-022-01645-7.

Page MJ, Moher D, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, McKenzie JE. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n160.

Rasmussen C, Kully-Martens K, Denys K, Badry D, Henneveld D, Wyper K, et al. The Effectiveness of a Community-Based Intervention Program for Women At-Risk for Giving Birth to a Child with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD). Community Ment Health J. 2012;48(1):12–21.

Floyd RL, Sobell M, Velasquez MM, Ingersoll K, Nettleman M, Sobell L, et al. Preventing Alcohol-Exposed Pregnancies. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(1):1–10.

George MA, Masotti P, MacLeod S, Van Bibber M, Loock C, Fleming M, et al. Bridging the research gap: aboriginal and academic collaboration in FASD prevention. The Healthy Communities Mothers and Children Project. Alaska Med. 2007;49(2_Suppl):139–41.

Peadon E, O’Leary C, Bower C, Elliott E. Impacts of alcohol use in pregnancy–the role of the GP. Aust Fam Physician. 2007;36(11):935–9.

Mendoza R, Morales-Marente E, Palacios MS, Rodríguez-Reinado C, Corrales-Gutiérrez I, García-Algar Ó. Health advice on alcohol consumption in pregnant women in Seville (Spain). Gac Sanit. 2020;34(5):449–58.

Crawford-Williams F, Steen M, Esterman A, Fielder A, Mikocka-Walus A. “If you can have one glass of wine now and then, why are you denying that to a woman with no evidence”: Knowledge and practices of health professionals concerning alcohol consumption during pregnancy. Women Birth. 2015;28(4):329–35.

Clarren SK, Astley SJ. Identification of children with Fetal Alcohol Syndrome and opportunity for referral of their mothers for primary prevention--Washington, 1993-1997. MMWR: Morbidity & Mortality Weekly Report. 1998;47(40):861–64.

Tan CH, Hungerford DW, Denny CH, McKnight-Eily LR. Screening for Alcohol Misuse: Practices Among U.S. Primary Care Providers, DocStyles 2016. Am J Prev Med. 2018;54(2):173–80.

O’Connor MJ, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Tomlinson M, Bill C, LeRoux IM, Stewart J. Screening for fetal alcohol spectrum disorders by nonmedical community workers. J Popul Ther Clin Pharmacol. 2014;21(3):e442-452.

Shanley DC, Hawkins E, Page M, Shelton D, Liu W, Webster H, et al. Protocol for the Yapatjarrathati project: a mixed-method implementation trial of a tiered assessment process for identifying fetal alcohol spectrum disorders in a remote Australian community. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):649.

McFarlane A, Rajani H. Rural FASD diagnostic services model: Lakeland Centre for fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. Can J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;14(3):e301-306.

Washio Y, Frederick J, Archibald A, Bertram N, Crowe JA. Community-I nitiated Pilot Program « My Baby’s Breath » to Reduce Prenatal Alcohol Use. Del Med J. 2017;89(2):46–51.

Hanlon-Dearman A, Green CR, Andrew G, LeBlanc N, Cook JL. Anticipatory Guidance For Children And Adolescents With Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (Fasd): Practice Points For Primary Health Care Providers. J Popul Ther Clin Pharmacol. 2015;22(1):e22–56.

Wagner B, Fitzpatrick JP, Mazzucchelli TG, Symons M, Carmichael Olson H, Jirikowic T, et al. Study protocol for a self-controlled cluster randomised trial of the Alert Program to improve self-regulation and executive function in Australian Aboriginal children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. BMJ Open. 2018;8(3):e021462.

Temple VK, Ives J, Lindsay A. Diagnosing FASD in adults: the development and operation of an adult FASD clinic in Ontario, Canada. J Popul Ther Clin Pharmacol. 2015;22(1):e96-105.

Russell M. New Assessment Tools for Risk Drinking During Pregnancy: T-ACE, TWEAK, and Others. Alcohol Health Res World. 1994;18(1):55–61.

Allen J, Gay B, Crebolder H, Heyrman J, Svab I, Ram P. The European Definition of General Practice/Family Medicine - Short Version Wonca Europe 2005. https://www.woncaeurope.org/page/definition-of-general-practice-family-medicine. Accessed 20 Aug 2022.

La durée des séances des médecins généralistes. DREES. N°481. Avril 2006. https://www.epsilon.insee.fr/jspui/bitstream/1/12653/1/er481.pdf. Accessed 21 Aug 2021.

Andler R, Cogordan C, Pasquereau A, Buyck J-F, Nguyen-Thanh V. The practices of French general practitioners regarding screening and counselling pregnant women for tobacco smoking and alcohol drinking. Int J Public Health. 2018;63(5):631–40.

Blondel B, Coulm B, Bonnet C, Goffinet F, Le Ray C. Trends in perinatal health in metropolitan France from 1995 to 2016: Results from the French National Perinatal Surveys. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2017;46(10):701–13.

Acknowledgements

The corresponding author would like to thank Dr Denis Pouchain for his review of the article.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Sebastien Leruste (SL) conducted the literature review. Michel Spodenkiewicz (MS) led the research and helped write the article. All authors (Bérénice Doray (BD), Thierry Maillard (TM), Christophe Lebon (CL), Catherine Marimoutou (CM)) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Leruste, S., Doray, B., Maillard, T. et al. Scoping review on the role of the family doctor in the prevention and care of patients with foetal alcohol spectrum disorder. BMC Prim. Care 25, 66 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-024-02291-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-024-02291-x