Abstract

Background

Older adults requiring care often have multiple morbidities that lead to polypharmacy, including the use of potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs), leading to increased medical costs and adverse drug effects. We conducted a cross-sectional study to clarify the actual state of drug prescriptions and the background of polypharmacy and PIMs.

Methods

Using long-term care (LTC) and medical insurance claims data in the Ibaraki Prefecture from April 2018 to March 2019, we included individuals aged ≥ 65 who used LTC services. The number of drugs prescribed for ≥ 14 days and the number of PIMs were counted. A generalized linear model was used to analyze the association between the backgrounds of individuals and the number of drugs; logistic regression analysis was used for the presence of PIMs. PIMs were defined by STOPP-J and Beers Criteria.

Results

Herein, 67,531 older adults who received LTC services were included. The median number of total prescribed medications and PIMs was 7(IQR 5–9) and 1(IQR 0–1), respectively. The main PIMs were loop diuretics/aldosterone antagonists (STOPP-J), long-term use of proton pump inhibitors (Beers Criteria), benzodiazepines/similar hypnotics (STOPP-J and Beers Criteria), and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (STOPP-J and Beers Criteria). Multivariate analysis revealed that the number of medications and presence of PIMs were significantly higher in patients with comorbidities and in those visiting multiple medical institutions. However, patients requiring care level ≥1, nursing home residents, users of short-stay service, and senior daycare were negatively associated with polypharmacy and PIMs.

Conclusions

Polypharmacy and PIMs are frequently observed in older adults who require LTC. This was prominent among individuals with comorbidities and at multiple consulting institutions. Utilization of nursing care facilities may contribute to reducing polypharmacy and PIMs.

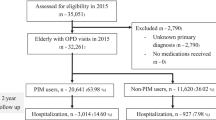

Graphical Abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Introduction

Healthcare in Japan is provided by universal health insurance, which covers 70–90% of medical treatment and medication expenses with an upper limit, keeping patients' out-of-pocket costs low. The long-term care system is based on public long-term care insurance separate from medical insurance. Unlike in the United States, private long-term care insurance is not widely used. Furthermore, contrary to European long-term care systems [1], no cash compensation is provided to informal caregivers such as family members [2]. The primary services include renting assistive devices, home-visit care, daycare, short-stay care, and nursing homes. Individuals requiring care undergo an assessment to receive services corresponding to their level of need irrespective of income level and availability of family caregiving [3].

Older adults requiring long-term care (LTC) often exhibit multiple comorbidities and use multiple medications, as documented in previous studies [4, 5]. Polypharmacy exerts economic pressure on healthcare and leads to an increased risk of hospitalization due to adverse drug events [6,7,8,9]. Medications deemed inappropriate for prescription, particularly for elderly individuals with diminished physical and metabolic capacity, are considered potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) [7].

Exploring the underlying context of these challenges is essential for finding clues to improve polypharmacy and PIMs. Background factors contributing to polypharmacy include age, comorbidities, obesity, and residence in LTC facilities [10,11,12,13]. Recently, polypharmacy and recent hospitalization, a number of prescriptions, cardiovascular diseases, metabolic disorders, and neurogenic motor functional impairments have been associated [14]. Multimorbidity and polypharmacy are risk factors for PIMs [10, 15]. However, previous research has focused mainly on residents of care facilities or small cohorts, necessitating larger-scale analyses using data representing the entire older population requiring care.

We conducted a cross-sectional study using medical and LTC claims insurance data to examine the prevalence and underlying factors of polypharmacy and PIMs in older adults requiring support or care.

Methods

Study design and data source

This cross-sectional study used medical insurance claims data and LTC insurance claims data from Ibaraki Prefecture, Japan, between April 2018 and March 2019. These medical claims data included information regarding citizen health insurance for municipalities (National Health Insurance) and unions for late elderly health insurance. Data regarding other types of health insurance (e.g., insurance for company employees) were not included.

Study population

By cross-referencing with medical claims data, we analyzed a population of individuals aged ≥ 65 years who used LTC insurance services in Ibaraki Prefecture, Japan. Among them, “Roken” (Geriatric Health Services Facilities) and “Integrated Facility for Medical and Long-term Care” residents were excluded from the analysis owing to the bundled payment system for medical services. Their medical costs were included in the LTC insurance. Therefore, the drugs prescribed were not recorded in the medical claims data [16, 17].

Of the 90,351 people identified in the LTC insurance service between April 2018 and March 2019, 9121 were Roken or Integrated Facility for Medical and Long-term Care residents, and 1732 were not certified for requiring LTC; these were excluded from the study population. Among them, 67,531 subscribers to the National Health Insurance services or Medical Insurance for the elderly were extracted.

Measurements

The number of drugs was defined as the number of oral medicines prescribed for ≥ 14 days within three months of the index month. The prescription of five or more medicines was defined as “polypharmacy” [18]. In this study, PIMs, such as sedatives and diuretics, were often prescribed repeatedly for short durations and were focused on orally administered medications prescribed for ≥ 14 days in outpatient settings, excluding those prescribed during hospitalization. The definition of PIMs followed the "Guidelines for Medical Treatment and Its Safety in the Elderly 2015 (STOPP-J)" by the Japan Geriatrics Society [19]. We also conducted the analysis of the PIMs using the Beers Criteria 2023 [7]. Medication counts were indexed from October 2018, and the number of medications prescribed for ≥ 14 days over the following three months was tallied.

Covariates

As background variables for polypharmacy and PIMs, data on age, sex, level of care needed, number of visiting medical institutions, Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) [20], physician home-visits, home-visit nursing, and the LTC facility residence excluding Roken and Integrated Facility for Medical and Long-term Care, as well as senior daycare and short stays, were collected in October 2018. The CCI was calculated based on medical claims data using ICD-10 codes from April 2018 to October 2018, as described in our previous study [21], using the 2011 updated and reweighted version validated in a Japanese national administrative dataset [22]. An overview of the study design is shown in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Statistical analysis

First, we describe the characteristics of the individuals who require support or LTC. We counted the number of orally administered medications prescribed for ≥ 14 days as well as the number of PIMs.

Next, we analyzed the types of frequently prescribed orally administered medications and PIMs. For the relationship between the number of prescribed medications and PIMs and background variables related to LTC services, multivariate analysis was conducted using a generalized linear model with Poisson distribution for the total number of medicines prescribed for ≥ 14 days and a logistic regression analysis for the presence of PIMs. Descriptive statistics for the background variables, medication counts, and multivariate analyses were performed using Stata version 15.0 (Stata Corp LP, College Station, TX, USA). R version 4.2.2 was used to analyze frequently prescribed medication types. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Study participants’ characteristics

The characteristics of the study participants are described in Table 1.

The median age was 87 (82–91, IQR), the median CCI was 2 (1–4, IQR), and the median number of consulting institutions was 2 (1–2, IQR). Table 1 describes the characteristics of the study population and the number of prescribed medicines and PIMs for ≥ 14 days.

The median number of oral medicines prescribed for ≥ 14 days was 7 (4–9, IQR). The number of PIMs was 1 (0–2, IQR), and 66.5% of patients had at least one PIM. The distribution of the number of medicines according to each variable is listed in Supplemental Fig. 2a-k.

Frequently prescribed medicines

Frequently prescribed medications include antihypertensives, laxatives, gastric acid suppressants, diuretics, anti-platelets, analgesics, anxiolytics/hypnotics, anti-dementia drugs, and anti-hyperlipidemics.

The most commonly prescribed PIMs defined by STOPP-J were diuretics (loop-diuretics/spironolactone) and proton pump inhibitors by Beers Criteria, followed by benzodiazepines or benzodiazepine-like hypnotics or anxiolytics and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) by both criteria (Table 2).

Multivariate analysis

Table 3 lists the background factors associated with the total number of prescribed medications for ≥ 14 days. The factors related to the presence of PIMs by STOPP-J are shown in Table 4 and by Beers Criteria in the Supplemental table. Physician home visits and home-visit nursing are associated with an increased number of drugs. Meanwhile, this number decreased for people aged ≥ 85 years. Female sex was associated with the presence of PIMs by both STOPP-J and Beers. CCI ≥ 1 and 2 or more consulting institutions were associated with an increased number of drugs and PIMs (STOPP-J and Beers). Care-level ≥ 1, senior daycare, short-stay service, and nursing home were associated with a decreased number of medicines and PIMs (STOPP-J and Beers). The results of the multivariate analysis are summarized in Fig. 1.

Discussion

The older adults in Ibaraki Prefecture closely mirror the age distribution of the Japanese population; the sample is not precisely representative but is consistent with the situation in Japan. This study is based on LTC claims, and medical insurance claims data, reflecting the reality of medical care for older adults requiring LTC.

By analyzing prescription patterns for older adults requiring LTC, the top five categories were anti-hypertensives, laxatives, gastric acid suppressants, diuretics, and antiplatelet agents. While these findings are generally consistent with previous research conducted among individuals aged ≥ 75 years in Tokyo [23], we found a higher prevalence of laxative and diuretic use in our study population. This may reflect the higher prevalence of constipation and edema due to hypertension and heart failure among older adults who require LTC. Diuretics and anxiolytics/hypnotics are the most common types of PIMs. Diuretics pose the risks of electrolyte imbalance and falls [19, 24,25,26]. Similarly, benzodiazepines or similar anxiolytics/hypnotics carry the risks of delirium and falls and should be avoided.

We analyzed the background of polypharmacy and PIMs. Multivariate analysis suggested that the total number of medications and PIMs was higher among patients with comorbidities and among those from more than one consulting institution. Total medication prescriptions and PIMs decreased among those with care needs levels 1–5 compared to those with support level 1–2. In older adults certified for long-term care (LTC), polypharmacy and rates of potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) are significantly elevated compared to those without LTC certification [27]. Polypharmacy reaches its peak at mild care need levels, while the prevalence of PIMs escalates with increasing levels of care needs [27]. While our findings are consistent with those of previous research, our study analyzed a five times larger number of exclusively certified care-needing individuals, which may enhance its reliability. Nursing home residents are at high risk of polypharmacy [14]. However, a narrative review indicated various attempts to rationalize pharmacotherapy in nursing homes, including medication reviews and multidisciplinary and patient-centered interventions that have shown effectiveness [28]. Admission to a nursing home facilitated the rectification of the living environment and nutritional status, and various interventions by the home staff might have contributed to reducing the number of medications.

In addition to nursing homes, users of day-care and short-stay services exhibited significantly lower rates of polypharmacy and PIMs. Loneliness and social isolation have been associated with polypharmacy [29], and homebound older adults are at high risk of polypharmacy [30]. Additionally, Vyas et al. reported that lonely older individuals often use opioids and benzodiazepines daily [31]. Day-care and short-stay services provide opportunities for interaction with other older adults in the community and interventions from healthcare and medical experts, thereby preventing social isolation. Short-stay services have been associated with improvements in cognitive function [32, 33] and extended periods of living at home [34]. The use of nursing care facilities such as nursing homes, day-care, and short-stay services may contribute to improving polypharmacy and PIMs.

Home-visit nursing and physician home visits were associated with polypharmacy but not with PIMs. Home-visit nursing reportedly reduces hospitalizations among older adults [35]. However, compared with nursing homes, home-visit nursing has been associated with increased medication-related issues [36]. Home-visit nursing users often have high care needs, respiratory or circulatory diseases, and long durations of care [35], rendering them prone to polypharmacy. Home-visiting physicians are responsible for homebound individuals who have difficulty visiting outpatient clinics. Homebound older adults tend to have multiple chronic conditions and require medications [10, 37]. As a result of addressing the medical needs of patients who had not previously received adequate medical care, home-visit nursing and physician home visits may have contributed to an increase in the number of prescribed medications.

This study demonstrated a strong association between CCI, polypharmacy, and PIMs. Komiya et al. reported a significant association between the CCI and polypharmacy in homebound patients and polypharmacy [10]. A systematic review by Jokanovic et al. further reported a substantial correlation between polypharmacy and CCI in LTC facilities [14]. Our results are consistent with those of previous studies.

Universal healthcare coverage and free access are key features of Japan's healthcare system, allowing patients with multiple co-morbidities to consult different specialists and receive high-quality medical care. However, this may lead to an increase in the number of prescriptions and complications associated with medication regimens. Few studies have examined the relationship between polypharmacy and the number of consulting institutions. A single-center study reported the relationship between polypharmacy and the department visited by older adult patients at a medium-sized hospital [38]. We previously reported a correlation between the number of medical institutions visited and polypharmacy through questionnaire-based data collection targeting older adults in a single city in Japan [39].

Based on an analysis of medical and care claims data, our study revealed a significant correlation between the number of medical institutions visited and the total number of medications and PIMs. Careful consideration of the advantages and disadvantages of a free-access system and the need for gatekeepers to oversee patient prescriptions may be necessary.

Our study has several limitations: The data were limited to the National Health Insurance or Medical Insurance for the elderly in the latter stage of life in Ibaraki Prefecture in the Kanto region of Japan. Employee Health Insurance data are unavailable. This study focused exclusively on orally administered medications and excluded topical and injectable formulations. In addition, medications administered weekly or monthly, such as those prescribed once a week or once a month, were omitted, as only drugs prescribed for ≥ 14 days within three months were counted. Further research using nationwide databases is required to analyze the trends and regional differences across Japan. This study was cross-sectional; therefore, outcomes cannot be evaluated based on the factors extracted from it. Misclassification of the CCI is likely because it is based on the diagnoses recorded in medical claims.

In conclusion, most adults aged ≥ 65 years using LTC services were in a state of polypharmacy. Additionally, more than 60% of the patients had one or more PIMs. High CCI scores and a large number of consulting institutions were associated with a higher risk of polypharmacy and PIMs. Conversely, utilization of nursing care facilities, such as nursing homes, senior daycare services, and short-stay services may contribute to reducing polypharmacy and PIM.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets for individual information generated and/or analyzed during the current study, which includes LTC insurance claims data and medical insurance claims data are not publicly available because the local government of Ibaraki Prefecture owns the original data and only approved the secondary use of the data for the current study.

References

Fabbietti P, Santini S, Piccinini F, Giammarchi C, Lamura G. Predictors of deterioration in mental well-being and quality of life among family caregivers and older people with long-term care needs during the COVID-19 pandemic. Healthcare (Basel). 2024;12(3):383.

Miyazaki R. Long-term care and the state-family nexus in italy and japan-the welfare state, care policy and family caregivers. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(3):2027.

Iwagami M, Tamiya N. The long-term care insurance system in Japan: past, present, and future. JMA J. 2019;2(1):67–9.

Andrew MK, Purcell CA, Marshall EG, Varatharasan N, Clarke B, Bowles SK. Polypharmacy and use of potentially inappropriate medications in long-term care facilities: does coordinated primary care make a difference? Int J Pharm Pract. 2018;26(4):318–24.

Hamada S, Iwagami M, Sakata N, Hattori Y, Kidana K, Ishizaki T, et al. Changes in polypharmacy and potentially inappropriate medications in homebound older adults in Japan, 2015–2019: a nationwide study. J Gen Intern Med. 2023;38(16):3517–25.

Chang YP, Huang SK, Tao P, Chien CW. A population-based study on the association between acute renal failure (ARF) and the duration of polypharmacy. BMC Nephrol. 2012;13:96.

By the American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria Update Expert P. American Geriatrics Society 2023 updated AGS Beers Criteria(R) for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2023;71(7):2052–81.

Lalic S, Sluggett JK, Ilomaki J, Wimmer BC, Tan EC, Robson L, et al. Polypharmacy and medication regimen complexity as risk factors for hospitalization among residents of long-term care facilities: a prospective cohort study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17(11):1067 e1-e6.

Abe T, Tamiya N, Kitahara T, Tokuda Y. Polypharmacy as a risk factor for hospital admission among ambulance-transported old-old patients. Acute Med Surg. 2016;3(2):107–13.

Komiya H, Umegaki H, Asai A, Kanda S, Maeda K, Shimojima T, et al. Factors associated with polypharmacy in elderly home-care patients. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2018;18(1):33–41.

O’Dwyer M, Peklar J, McCallion P, McCarron M, Henman MC. Factors associated with polypharmacy and excessive polypharmacy in older people with intellectual disability differ from the general population: a cross-sectional observational nationwide study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(4):e010505.

Slater N, White S, Venables R, Frisher M. Factors associated with polypharmacy in primary care: a cross-sectional analysis of data from The English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA). BMJ Open. 2018;8(3):e020270.

Delara M, Murray L, Jafari B, Bahji A, Goodarzi Z, Kirkham J, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with polypharmacy: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2022;22(1):601.

Jokanovic N, Tan EC, Dooley MJ, Kirkpatrick CM, Bell JS. Prevalence and factors associated with polypharmacy in long-term care facilities: a systematic review. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16(6):535 e1-12.

Lopez-Rodriguez JA, Rogero-Blanco E, Aza-Pascual-Salcedo M, Lopez-Verde F, Pico-Soler V, Leiva-Fernandez F, et al. Potentially inappropriate prescriptions according to explicit and implicit criteria in patients with multimorbidity and polypharmacy. MULTIPAP: A cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2020;15(8):e0237186.

Maruoka H, Hamada S, Hattori Y, Arai K, Arimitsu K, Higashihara K, et al. Changes in chronic disease medications after admission to a Geriatric Health Services Facility: a multi-center prospective cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2023;102(21):e33552.

Hamada S, Kojima T, Sakata N, Ishii S, Tamiya N, Okochi J, et al. Drug costs in long-term care facilities under a per diem bundled payment scheme in Japan. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2019;19(7):667–72.

Masnoon N, Shakib S, Kalisch-Ellett L, Caughey GE. What is polypharmacy? A systematic review of definitions. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(1):230.

Kojima T, Mizukami K, Tomita N, Arai H, Ohrui T, Eto M, et al. Screening Tool for Older Persons’ Appropriate Prescriptions for Japanese: Report of the Japan Geriatrics Society Working Group on “Guidelines for medical treatment and its safety in the elderly.” Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2016;16(9):983–1001.

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–83.

Mori T, Hamada S, Yoshie S, Jeon B, Jin X, Takahashi H, et al. The associations of multimorbidity with the sum of annual medical and long-term care expenditures in Japan. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19(1):69.

Quan H, Li B, Couris CM, Fushimi K, Graham P, Hider P, et al. Updating and validating the Charlson comorbidity index and score for risk adjustment in hospital discharge abstracts using data from 6 countries. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(6):676–82.

Ishizaki T, Mitsutake S, Hamada S, Teramoto C, Shimizu S, Akishita M, et al. Drug prescription patterns and factors associated with polypharmacy in >1 million older adults in Tokyo. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2020;20(4):304–11.

Gurwitz JH, Field TS, Judge J, Rochon P, Harrold LR, Cadoret C, et al. The incidence of adverse drug events in two large academic long-term care facilities. Am J Med. 2005;118(3):251–8.

de Vries M, Seppala LJ, Daams JG, van de Glind EMM, Masud T, van der Velde N, et al. Fall-risk-increasing drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis: I. Cardiovascular Drugs. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2018;19(4):371 e1-e9.

O’Mahony D, Cherubini A, Guiteras AR, Denkinger M, Beuscart JB, Onder G, et al. STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: version 3. Eur Geriatr Med. 2023;14(4):625–32.

Kojima T, Hamaya H, Ishii S, Hattori Y, Akishita M. Association of disability level with polypharmacy and potentially inappropriate medication in community dwelling older people. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2023;106:104873.

Spinewine A, Evrard P, Hughes C. Interventions to optimize medication use in nursing homes: a narrative review. Eur Geriatr Med. 2021;12(3):551–67.

Svensson M, Ekstrom H, Elmstahl S, Rosso A. Association of polypharmacy with occurrence of loneliness and social isolation among older adults. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2024;116:105158.

Cook EA, Duenas M, Harris P. Polypharmacy in the Homebound Population. Clin Geriatr Med. 2022;38(4):685–92.

Vyas MV, Watt JA, Yu AYX, Straus SE, Kapral MK. The association between loneliness and medication use in older adults. Age Ageing. 2021;50(2):587–91.

Chen AC, Epstein AM, Joynt Maddox KE, Grabowski DC, Orav EJ, Barnett ML. Impact of dementia special care units for short-stay nursing home patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2023;72:767–77.

Loomer L, Downer B, Thomas KS. Relationship between Functional Improvement and Cognition in Short-Stay Nursing Home Residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(3):553–7.

Moriyama Y, Tamiya N, Kawamura A, Mayers TD, Noguchi H, Takahashi H. Effect of short-stay service use on stay-at-home duration for elderly with certified care needs: analysis of long-term care insurance claims data in Japan. PLoS One. 2018;13(8):e0203112.

Kashiwagi M, Tamiya N, Sato M, Yano E. Factors associated with the use of home-visit nursing services covered by the long-term care insurance in rural Japan: a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2013;13:1.

Eltaybani S, Kawase K, Kato R, Inagaki A, Li CC, Shinohara M, et al. Effectiveness of home visit nursing on improving mortality, hospitalization, institutionalization, satisfaction, and quality of life among older people: Umbrella review. Geriatr Nurs. 2023;51:330–45.

Kojima T, Mizokami F, Akishita M. Geriatric management of older patients with multimorbidity. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2020;20(12):1105–11.

Nomoto S, Nakanishi Y. Investigation of polypharmacy in late-stage elderly patients visiting a community hospital outpatient unit. Nihon Ronen Igakkai Zasshi. 2011;48(3):276–81.

Suzuki T, Iwagami M, Hamada S, Matsuda T, Tamiya N. Number of consulting medical institutions and risk of polypharmacy in community-dwelling older people under a healthcare system with free access: a cross-sectional study in Japan. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):359.

Acknowledgements

The authors grateful to the members of the Health Service Research Department at the University of Tsukuba and to Editage (www.editage.jp) for English language editing.

Funding

This study was supported by the JSPS KAKENHI (grant number: JP23K09521).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SH designed the study, performed the data analysis, and wrote the paper. JK supported the research and data analysis design and revised the manuscript. MI, SH, MK, and HK revised the manuscript. NT supervised the study and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, University of Tsukuba (approval no.1595–5) approved this study. Individual informed consent was waived because the medical insurance and LTC claims data were anonymized before they were made available to the researchers. All methods were carried out in accordance with the ethical guidelines for medical and biological research involving human subjects in Japan (2023) and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

12877_2024_5296_MOESM2_ESM.pptx

Supplementary Material 2. Supplemental Figure 2 a-k. The distribution of the number of medicines prescribed over 14 days or more

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hagiwara, S., Komiyama, J., Iwagami, M. et al. Polypharmacy and potentially inappropriate medications in older adults who use long-term care services: a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr 24, 696 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-024-05296-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-024-05296-4