Abstract

Background

Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) is a global health concern, causing over 35 million deaths, with 97% occurring in developing nations, particularly impacting Sub-Saharan Africa. While HIV testing is crucial for early treatment and prevention, existing research often focuses on specific groups, neglecting general adult testing rates. This study aims to identify predictors of HIV testing uptake among adults in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Method

Data were obtained from the official Demographic and Health Survey program database, which used a multistage cluster sampling technique to collect the survey data. In this study, a weighted sample of 283,936 adults was included from thirteen Sub-Saharan African countries. Multilevel multivariable logistic regression analysis was employed to identify predictors of HIV testing uptake. Akaike’s information criteria guided model selection. Adjusted odds ratios and corresponding 95% confidence intervals determined significant predictor variables.

Result

Among adults in Sub-Saharan African countries, the prevalence of HIV testing uptake was 65.01% [95% CI (64.84%, 65.17%)]. Influential factors included male sex [AOR: 0.51, 95% CI (0.49,0.53)], varying odds ratios across age groups (20–24 [AOR: 3.3, 95% CI (3.21, 3.46) ], 25–29 [AOR: 4.4, 95% CI (4.23, 4.65)], 30–34 [AOR: 4.6, 95%CI (4.40, 4.87)], 35–39 [AOR: 4.0, 95%CI (3.82, 4.24)], 40–44 [AOR: 3.7, 95%CI (3.50, 3.91)], 45–49 [AOR: 2.7, 95%CI (2.55, 2.87)], 50+ [AOR: 2.7, 95%CI (2.50, 2.92)]), marital status (married [AOR: 3.3, 95%CI (3.16, 3.46)], cohabiting [AOR: 3.1, 95% CI (2.91, 3.28)], widowed/separated/divorced [AOR: 3.4, 95%CI (3.22, 3.63)]), female household headship (AOR: 1.28, 95%CI (1.24, 1.33)), education levels (primary [AOR: 3.9, 95%CI (3.72, 4.07)], secondary [AOR: 5.4, 95%CI (5.16, 5.74)], higher [AOR: 8.0, 95%CI (7.27, 8.71)]), media exposure (AOR: 1.4, 95%CI (1.32, 1.43)), wealth index (middle [AOR: 1.20, 95%CI (1.17, 1.27)], richer [AOR: 1.50, 95%CI (1.45, 1.62)]), Having discriminatory attitudes towards PLWHIV [AOR: 0.4; 95% CI (0.33, 0.37)], had multiple sexual partners [AOR: 1.2; 95% CI (1.11, 1.28)], had comprehensive knowledge about HIV [AOR: 1.6; 95% CI (1.55, 1.67)], rural residence (AOR: 1.4, 95%CI (1.28, 1.45)), and lower community illiteracy (AOR: 1.4, 95%CI (1.31, 1.50)) significantly influenced HIV testing uptake in the region.

Conclusion

This study highlights the need for tailored interventions to address disparities in HIV testing uptake among adults in Sub-Saharan Africa and progress towards the achievement of 95-95-95 targets by 2030. Thus, tailored interventions addressing key factors are crucial for enhancing testing accessibility and emphasizing awareness campaigns, easy service access, and targeted education efforts to improve early diagnosis, treatment, and HIV prevention in the region.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) remains a significant global public health concern, having tragically resulted in more than 35 million deaths to date [1]. Approximately 770,000 and more than 630, 000 individuals lost their lives due to HIV-related causes worldwide in the years 2018 and 2022, respectively [1, 2]. 97% of these occur in developing nations, with Sub-Saharan Africa being the primary region affected by this disease [3]. In addition, according to a recent report, an estimated population of over 39 million individuals was reported to be living with HIV in 2022, with two-thirds of these individuals residing in the World Health Organization (WHO) African Region [4].

HIV testing is a fundamental approach that serves as a crucial initial step in identifying, treating, and preventing the spread of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). It enables individuals to become aware of their HIV status and to seek treatment and/or preventive care [5]. Studies conducted in different regions of the world have reported varying levels of HIV testing uptake coverage. According to a systematic analysis conducted across sixty-nine countries, the HIV testing uptake varies considerably, ranging from 11% in Yemen to 87% in the Netherlands [6]. Similarly, the prevalence of HIV testing among diverse adult populations varies substantially, ranging from 7.6 to 80.9% across African countries [7,8,9,10,11].

Moreover, studies conducted in diverse regions of the world have identified various variables that are significantly associated with HIV testing uptake among adults. For instance factors such as age [11,12,13,14,15,16], marital status [11, 13,14,15], working status [13], educational status [13, 14, 16], gender [13, 15], wealth index [13,14,15,16], residence [11, 13, 14], religion [14, 16], comprehensive knowledge of HIV [11, 14,15,16], stigma towards HIV patients [11, 15], age at first sex [11, 16], risky sexual behavior [11, 15], health insurance coverage [16], and discriminatory attitudes toward HIV patients [16] were reported to significantly impact the uptake of HIV testing among the adult population.

Globally, significant efforts have been made to reduce the rate of HIV transmission and increase the coverage of HIV testing among adults. This includes the introduction of the guidance on provider-initiated HIV testing and counselling in health facilities by WHO and the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) in 2007 [17] and the 90-90-90 agenda by the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) and its partners in 2014 [18].

Despite recognizing the positive outcomes of these efforts [19], there is still a significant amount of work needed to improve the global coverage of HIV testing, as suggested by information from the Global Health Sector Strategy on HIV/AIDS for 2022–2030 [20]. Moreover, even with the suggested HIV testing for all individuals aged 13 to 64 in every healthcare setting [21], there is evidence to suggest that ongoing policy, social, and legal obstacles persist, impeding access to HIV testing and care services for this demographic, especially in developing nations [22].

Studies have been undertaken in different regions across Africa to assess the adoption of HIV testing. However, these studies primarily focused on specific populations, such as men or women exclusively [8,9,10,11,12, 23], limiting their ability to provide a comprehensive understanding of HIV testing behavior. Additionally, while one study included both men and women, it relied on older surveys conducted between 2003 and 2016 [24], potentially affecting the relevance of its findings to current trends. Understanding individual and community-level factors impacting HIV testing rates among adult populations in Sub-Saharan Africa can inform policymakers, aiding the development of more effective testing policies and strategies. Additionally, findings offer vital insights into the progress of Sub-Saharan African countries toward reaching the 2025 global health sector strategy on HIV/AIDS. [20]. Therefore, this study aims to identify such factors, utilizing a mixed-effect analysis of 2015–2022 Demographic and Health Survey data across Sub-Saharan African countries.

Methods

Data source

The data utilized in this study were obtained from the official database website (http://dhsprogram.com) of the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) program. We combined the DHS data from thirteen Sub-Saharan African countries. To include the countries in this study, we considered the survey years from 2015 to 2022. As a result, we identified 27 countries with survey years falling within this period. From this group, the dataset from fourteen countries showed either no observations for the outcome variable (i.e., HIV test) or were incomplete (Benin, Burkina Faso, Chad, Cote d’Ivoire, Gambia, Liberia, Madagascar, Mali, Mauritania, Mozambique, Niger, Nigeria, Tanzania, and Senegal). Ultimately, the analysis included datasets from thirteen countries (Angola, Burundi, Cameroon, Ethiopia, Gabon, Guinea, Malawi, Rwanda, Sierra Leone, South Africa, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe).

Data extraction and management of missing observation

The Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) utilized a standardized approach to gather data concerning fundamental health metrics and sociodemographic factors across all countries encompassed in this study. Since this research focused on the adult population aged 15–64, we initially retrieved records for both males (MR) and females (IR) from all countries, merged the datasets, and omitted those with missing data. Ultimately, the analysis involved a weighted sample of 283, 936 adults in this study. Further details regarding the survey methodology can be accessed online [25].

Study variable

Dependant variable

In this study, the outcome variable was the uptake of HIV testing. In the survey, participants were asked whether they ‘had ever been tested for HIV.’ The response for this variable was binary which coded as “0” for no and “1” for yes.

Independent variables

In this study were divided into individual and community-level categories. Individual-level variables included sex, age, sex of household head, educational attainment, wealth index, media exposure, internet usage, and marital status. The wealth index was reclassified as poor = 0 for households in the poorest and poorer categories, middle = 1, and rich = 2 for households in the rich and richest categories.

Media exposure was derived from variables related to reading newspapers, listening to the radio, and watching television. As a result, individuals in the adult population who read a newspaper, listened to the radio, and watched television less than once and at least once a week were classified as having mass media exposure (coded = 1). Conversely, those who did not engage in these activities were classified as not having mass media exposure (coded = 0).

Discriminatory attitudes towards people living with HIV (PLWHIV) were assessed using two questions: “Should children living with HIV be able to attend school with children who do not have HIV?” and “Would you buy fresh vegetables from a shopkeeper or vendor if you knew that this person had HIV?” Participants who answered “No” to either or both of these questions were considered as having discriminatory attitudes towards PLWHIV.

Participants’ comprehensive knowledge of HIV was computed from six questions related to HIV prevention and misconceptions.The questions included: “Know that using a condom every time they have sex can reduce the risk of getting HIV, know that having just one uninfected faithful partner can reduce the risk of getting HIV, know that a healthy-looking person can have HIV, know that HIV cannot be transmitted by mosquito bites, know that a person cannot become infected by sharing food with a person who has HIV, and know thay a person can not get HIV by witchcraft or supernatural means.” Following the DHS-8 guidelines, participants who answered at least the first five questions correctly were considered to have comprehensive knowledge about HIV and were labeled as “yes,” while those who did not meet this criterion were labeled as “no” [26].

In this study, community-level variables include residence, community poverty levels, community-level illiteracy, and community-level media exposure. These community-level factors(i.e. community poverty levels, community-level illiteracy, and community-level media exposure) were calculated by combining individual-level data at the cluster level, and median values were used to categorize these variables as either “low” or “high.”

Data management and statistical analysis

After obtaining the authorization letter, we accessed the datasets of all countries included in this study from the official database of the DHS program. Subsequently, we utilized STATA Version 17 software to clean the datasets of each country, addressing inconsistent and missing observations. Then, these cleaned datasets were consolidated into a single dataset, and variables of interest were extracted based on existing literature. Furthermore, we applied weighting to the data to address the non-representativeness of the sample and ensure reliable estimates. The descriptive results were presented in the form of frequencies and percentages. A pooled prevalence of HIV testing uptake was estimated by combining data from thirteen countries. This was calculated using a variable titled “had ever been tested for HIV,” coded as “0” for “no” and “1” for “yes.” Participants responding “yes” in the combined dataset were considered a pooled estimate of the outcome variable. In addition, we employed a multilevel multivariable logistic regression analysis to accommodate the hierarchical nature of DHS data and identify determinants of HIV testing uptake. The selection of variables for the multilevel multivariable logistic regression analysis was guided by the results of a binary logistic regression analysis, specifically those with a P-value of less than 0.25. Additionally, to ensure the absence of multicollinearity among the predictor variables, the Generalized Variance Inflation Factor (GVIF) was utilized, with a cut-off value set at 10. Upon examination, the GVIF for all predictor variables in this study fell within the range of 1.05 to 1.55, with a mean of 1.35. This suggests the absence of multicollinearity among the independent variables.

Model building and selection

To conduct the multilevel multivariable logistic regression analysis, we constructed four models targeting the variables of interest. Subsequently, we identified the most suitable model. The initial model (null model) assessed random variability in the intercept and computed the Intra-class Correlation Coefficient (ICC), Median Odds Ratio (MOR), and Proportion Change in Variance (PCV).

Mathematical Null Model:

Where:

Pi = probability of an individual taking up HIV testing based on various variables.

M = overall prevalence of HIV testing uptake expressed on the logistic scale.

EA = area-level residual.

The Intra-class Correlation Coefficient (ICC) represents the proportion of variation in HIV testing uptake between clusters, relative to the total variation.

where VA denotes the community or cluster level variance and Π2/3 = 3.29 is the assumed household variance component.

The Median Odds Ratio (MOR) measures how much HIV testing uptake varies between communities, using the odds ratio (OR) scale. It’s calculated as the median OR between a high-risk and a low-risk community when individuals are randomly chosen from each.

Where VA is a cluster variance.

Proportion Change in Variance (PCV) quantifies the variability of HIV testing uptake explained by successive models.

Where: VA is the variance in the initial model. Vn is the variance in the model with additional terms.

The second model incorporated only community-level explanatory variables to estimate the variance in HIV testing uptake attributable to community characteristics.

Mathematical Model II: Community-Level Effects.

Logit(Pi) = M + β1residece + β2 community illiteracy + β3 community poverty + β4 community media exposure + EA.

Where:

Pi = probability of an individual taking up HIV testing based on various variables.

M = overall prevalence of HIV testing uptake expressed on the logistic scale.

EA = area-level residual.

β1, β2, β3, and β4 are the regression coefficients for community-level variables.

The third model exclusively included individual-level explanatory variables to estimate the variance in HIV testing uptake attributable to individual characteristics.

Mathematical Model III: Individual-Level Effects.

Logit(Pi) = M + β1sex + β2 age + β3 marital status + β4 education +… + β11 HIV knowledge + EA.

Where:

β1…. β11 are the regression coefficients for individual-level variables.

Lastly, the fourth and final model (full model) scrutinized the collective impact of both individual and community-level predictors on the outcome variable.

Mathematical Model IV: Logit regression with both community and individual-level predictors.

Logit(Pi) = M + β1residece + β2 community illiteracy + β3 community poverty + β4 community media exposure + β5 sex + β6 age + β7 marital status + β8 education +… + β15 HIV knowledge + EA.

Where:

β1, β2, β3, and β4 are the regression coefficients for community-level variables.

Β5…. β15 are the regression coefficients for individual-level variables.

In the final analysis, we relied on Akaike’s information criterion (AIC) value to determine the most appropriate model, selecting the model with the lowest AIC value as the best-fitted one. In the multivariable mixed-effects logistic regression analysis, a p-value lower than 0.05 signified the statistical significance of an explanatory variable. Moreover, we employed adjusted odds ratios (AOR) with a 95% confidence interval in the multivariable analysis to pinpoint variables that yielded statistically significant effects on the outcome variable.

Ethical approval

The survey procedures were approved by the ICF Institutional Review Board (IRB) and the host country’s IRB during the initial data collection. Additionally, written informed consent was obtained from each participant at the onset of the data collection period. However, as our study relied on secondary data, permission to access the data (AuthLetter_197479) used was acquired from the Demographic and Health Survey by submitting an online request at http://www.dhsprogram.com. The data accessed were utilized exclusively for this registered study and are publicly available in the program’s official database.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics

Two-thirds (67%) of the respondents of this study were females, 62,847(22%) were within the age group of 15–19 years, 172,968(61%) were from rural residences, and 125,716 (44%) and 99,843 (35%) of respondents were married and never in union respectively. Concerning the educational status of respondents of this study, 56,845.39(20%) had no education and 19,216 (7%) had higher educational attainment. Moreover, 126,708 (45%) and 102, 074(36%) participants in this study were rich and poor concerning their wealth index. 71% (201,132) of respondents in this study, had exposure to media and 228, 629(80%) had never used the internet. Among the study participants, 209,854 (82%) respondents reported having no discriminatory attitude towards PLWHIV, 222,267 (95%) reported having a single sexual partner, and 182,572 (76%) reported having comprehensive knowledge about HIV (Table 1).

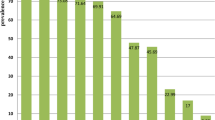

The pooled prevalence of the HIV-testing uptake

The pooled prevalence of HIV testing uptake among the adult population of Sub-Saharan African countries in this study was 65.01% [95% CI (64.84%, 65.17%)]. The highest HIV testing uptake was observed in Uganda 82.51% [95% CI (82.03%, 83.00%)] and the lowest was observed in Guinea 16.08% [95% CI (15.49, 16.67%)] (see Fig. 1).

Model comparison

The Intracluster Correlation Coefficient (ICC) of the null model revealed that 25% of the inconsistency in HIV testing uptake among adults in Sub-Saharan African countries was attributed to differences between clusters, while the remaining 75% of the variability was due to individual differences. Additionally, the Log-likelihood Ratio (LR) test proved to be significant, indicating that a multilevel binary logistic regression model provides a better fit for the data compared to classical regression models.

In the final model, the Proportion Change in Variance (PCV) indicated that 12.8% of the variation in HIV testing uptake within communities could be attributed to both individual and community-level variables. The Median Odds Ratio (MOR) indicated that HIV testing uptake is 2.47 times higher in communities where individuals have higher HIV testing uptake compared to communities where individuals have lower uptake. The Intracluster Correlation Coefficient (ICC) for the full model was 22.33%, indicating that 22.33% of the variation in HIV testing uptake among adults in Sub-Saharan African countries is attributable to differences between communities. The remaining 77.77% of the variation is due to a combination of individual and community-level factors. Moreover, as discussed in the methodology section, the model (i.e. model IV) with the lowest AIC value (301317.7) was selected as the best fit (see Table 2).

Determinants of HIV testing uptake among adult population of sub-saharan African countries

After fitting both individual and community-level variables together in the multilevel multivariable logistic regression, certain associations with HIV testing uptake among Adults were identified. The community-level variables such as residence, community-level illiteracy, and individual-level variables such as sex, age, marital status, educational status, wealth status, the status of media exposure, and household headship were found to be statistically associated with this HIV testing uptake among the adult population.

The likelihood of HIV testing was 49% lower among male adults compared with their counterparts [AOR: 0.51; 95% CI (0.49, 0.53)]. Adults aged 20–24 [AOR: 3.3; 95% CI (3.21, 3.46)], 25–29 [AOR: 4.4; 95% CI (4.23, 4.65)], 30–34 [AOR: 4.6; 95% CI (4.40, 4.87)], 35–39 [AOR: 4.0; 95% CI (3.82, 4.24)], 40–44 [AOR: 3.7; 95% CI (3.50, 3.91)], 45–49 [AOR: 2.7; 95% CI (2.55, 2.87)], and those aged 50 and above [AOR: 2.7; 95% CI (2.50, 2.92)] exhibited higher odds of HIV testing than the 15-19-year-olds.

The likelihood of HIV testing was higher among adults who were married [AOR: 3.3; 95% CI (3.16, 3.46)], living with a partner [AOR: 3.1;95% CI (2.91, 3.28)], and widowed/separated/divorced [AOR: 3.4; 95% CI (3.22, 3.63)] compared to those never in a union. Moreover, a female-headed household had a higher likelihood of undertaking an HIV test compared to with male- head household [AOR: 1.3; 95% CI (1.24, 1.33)]. Furthermore, the likelihood of HIV testing was higher among adults with primary [AOR: 3.9; 95% CI (3.72, 4.07)], secondary [AOR: 5.4; 95% CI (5.16, 5.74)], and higher education levels [AOR: 8.0; 95% CI (7.27, 8.71)] compared to their reference group.

The odds of HIV testing were 1.4 times higher among adults with media exposure [AOR:1.4; 95% CI (1.32, 1.43)] compared to those with no media exposure. Additionally, the likelihood of HIV testing was 20% and 50% higher among adults from middle [AOR: 1.20; 95% CI (1.17, 1.27)] and wealthy [AOR: 1.50; 95% CI (1.45, 1.62)] wealth index households, respectively, compared to their reference group. Compared to individuals with no discriminatory attitudes towards PLWHIV, the odds of HIV testing were 60% lower among those with discriminatory attitudes [AOR: 0.4; 95% CI (0.33, 0.37)]. In this study, the odds of HIV testing uptake were 1.2 and 1.6 times higher among adults who had multiple sexual partners [AOR: 1.2; 95% CI (1.11, 1.28)] and those who had comprehensive knowledge about HIV [AOR: 1.6; 95% CI (1.55, 1.67)], respectively.

Furthermore, the likelihood of HIV testing was notably higher among adults residing in rural areas [AOR: 1.4; 95% CI (1.28, 1.45)] compared to the reference group. Additionally, adults from communities with low illiteracy [AOR: 1.4; 95% CI (1.31, 1.50)] were observed to have a higher likelihood of being tested for HIV compared to those from communities with high illiteracy (see Table 3).

Discussion

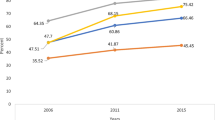

This study aimed to examine the determinants of HIV testing uptake among the adult population of Sub-Saharan Africa, using the DHS dataset from 2015 to 2022. The study identified a pooled prevalence of HIV testing uptake among adults in Sub-Saharan Africa at 65.01% [95% CI (64.84%, 65.17%)]. This figure surpasses rates found in studies conducted in Senegal [27], Ethiopia [28], and East Africa [11], potentially due to differences in study scope and participant demographics. Notably, the former two studies focused on a single country. Additionally, the proportion of HIV testing uptake found in this study was higher than proportions reported by previous studies conducted in Sub-Saharan Africa by Ante-Testard et al. [24]. and Staveteig et al. [29], which may be due to the use of older survey datasets (i.e., 2003–2016) in those studies. The increased prevalence of HIV testing uptake over time could be explained by improved funding programs for HIV [30] and the implementation of new approaches to promote HIV testing [31]. Nevertheless, our findings show lower rates compared to studies conducted in Cambodia [32], Uganda [33], and Kenya [34]. These variations may be attributed to differences in the study population, sample size, and the study period.

Findings from this study indicate a greater likelihood of female-headed household and female participants undergoing HIV testing. This finding is consistent with research conducted in Malaysia [35], Senegal [27], and Zimbabwe [36], all of which similarly reported elevated odds of HIV testing among females. The observed pattern suggests that enhanced access to reproductive health services among females may be a significant contributing factor. Additionally, factors such as targeted health education and awareness-raising initiatives within reproductive health services might further contribute to a greater likelihood of HIV testing uptake among female-headed households and the female population.

The impact of age on the uptake of HIV testing among adults in Sub-Saharan Africa was a significant variable examined in this study. The findings revealed that the likelihood of HIV testing uptake increases with age. This result is supported by corresponding results from previous studies. For instance, research by Erena et al. [5], Lakhe et al. [27], Adugna and Worku [11], and Alem et al. [15] all emphasized higher odds of HIV testing with advancing age. This trend may be associated with evidence indicating an increase in knowledge and awareness about HIV as individuals age [37]. Additionally, it implies greater exposure of aged adults to healthcare systems and health promotion efforts over time.

In this study, compared with an adult population who have no education and are poor, the uptake of HIV testing increases with the increased educational attainment and wealth index. In support of this finding consistent findings have been reported by researchers conducted elsewhere [5, 11, 27]. The possible explanation for this might be due to the vital role of educational attainment in increasing health literacy and understanding the importance of HIV testing and prevention. Likewise, individuals with a better wealth index (i.e. middle and rich) might have better financial resources to afford healthcare costs and reside in an area with a better infrastructure of healthcare.

In line with consistent findings from previous studies in Malawi [9], Kenya [38], Zambia [39], and Ethiopia [5, 40], survey participants who have been in a union have a higher likelihood of being tested for HIV compared to those who have never been in a union. This may be associated with the emphasis on joint health and shared responsibilities within marital relationships. Married individuals often have a strong interest in ensuring the collective well-being of their family unit, thereby demonstrating a greater inclination to engage in proactive health behaviors, including HIV testing.

In our study, we observed that participants who have had exposure to media showed increased odds of undergoing HIV testing compared to their counterparts. These findings align with previous studies conducted by Musheke et al. [41], Lakhe et al. [27], and Molla et al. [28], which also highlighted a higher likelihood of HIV testing uptake among individuals with media exposure. This consistency in results may be attributed to the fact that individuals exposed to media are more likely to access vital information about the significance of HIV testing and actively seek out opportunities to undergo the test.

While individual-level media exposure was associated with HIV testing uptake, community-level non-exposure to media did not show a significant association. This suggests that while media directly influences individual awareness of HIV-related behaviors, other factors, such as socioeconomic inequalities, access to healthcare, and community support networks, likely play a more critical role in determining HIV testing uptake at the community level. This finding underscores the need to address these broader community-level factors to ensure equitable access to HIV testing services [42, 43].

This study found that individuals holding discriminatory attitudes towards people living with HIV (PLWHIV) were less likely to engage in HIV testing. This finding aligns with research conducted in various African countries [16, 44, 45]. The reluctance to test may stem from a fear of social stigma and potential exclusion from socioeconomic activities should they receive a positive HIV test result.

This study indicated that participants who had multiple sexual partners were more likely to have been tested for HIV. This finding aligns with studies conducted by Bekele et al. [46], Mafigiri et al. [47] and Mahande et al. [48]. The increased likelihood of testing among individuals with multiple sexual partners may be attributed to their heightened risk of contracting sexually transmitted infections, including HIV. This heightened risk likely motivates them to become aware of their HIV status.

Besides, consistent with previous researchs [11, 14,15,16], this study found that participants with a comprehensive understanding of HIV were more likely to have been tested for HIV than those with less knowledge. This suggests that individuals with a thorough grasp of HIV recognize the importance of testing, understanding that a positive result enables access to treatment and prevention strategies.

Moreover, in line with previous studies [7, 11, 15], this research discovered that participants from communities with low illiteracy levels have a higher likelihood of undergoing HIV testing compared to those from communities with higher illiteracy rates. This trend could be attributed to the challenges faced by communities with higher illiteracy rates in comprehending the significance of HIV testing and navigating the healthcare system. Additionally, they may encounter obstacles such as restricted access to healthcare facilities, transportation challenges, and financial constraints when compared to their counterparts.

In contrast to previous research [7, 9, 49], our study surprisingly revealed that individuals residing in rural areas showed a higher likelihood of undergoing HIV testing compared to those from urban settings. This unexpected outcome could potentially be linked to the effective implementation of diverse community-based strategies aimed at enhancing HIV testing and counseling uptake in regions with restricted healthcare access [50].

Strengths and limitations

This study utilized a multi-level analysis approach, providing a comprehensive examination of factors influencing testing behavior. Leveraging large and nationally representative datasets enhances the generalizability of the findings to the adult population in Sub-Saharan Africa. Moreover, the research has the potential to guide evidence-based public health policies and interventions geared towards enhancing HIV testing uptake by highlighting key determinants at both individual and community levels. Ultimately, these contributions aim to advance HIV prevention and care efforts in the region.

While this study provides valuable insights, it is essential to acknowledge certain limitations. The research may be constrained by the cross-sectional nature of the data, limiting the ability to establish causal relationships over time. Sampling biases and potential data quality issues could impact the robustness of the findings, potentially leading to inaccuracies in measuring determinants of HIV testing behavior. Furthermore, as HIV testing uptake was self-reported, the data may be susceptible to recall bias and social desirability bias. The research timeframe might not fully capture recent dynamics in HIV testing patterns, potentially affecting the timeliness and relevance of the conclusions.

Conclusion

This study highlights the need for tailored interventions to address disparities in HIV testing uptake among adults in Sub-Saharan Africa and progress towards the achievement of 95-95-95 targets by 2030. Notably, factors at both community and individual levels significantly influenced the likelihood of undergoing HIV testing. Rural residence and lower community-level illiteracy were identified as crucial community determinants associated with increased HIV testing uptake. Individual-level variables such as female gender, age above 20, being married, higher education levels, improved wealth status, media exposure, holding non-discriminatory attitudes towards PLWHIV, having multiple sexual partner, having comprehensive knowledge of HIV, and being a female headed household were identified as positive predictors of higher HIV testing rates among adults in the region. These findings highlight the diverse range of factors impacting HIV testing behavior in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Recommendations

To improve HIV testing accessibility and uptake in the region, tailored interventions addressing the identified determinants are essential. Community-level initiatives should prioritize interventions that enhance health literacy, promote awareness campaigns, and ensure easy access to testing services, particularly in areas with lower uptake rates. At an individual level, targeted initiatives should address specific demographic groups, including: males, individuals under 20 years of age, those never in a union, individuals with no education, those with low wealth status, individuals with no media exposure, individuals with discriminatory attitudes towards PLWHIV, those with limited comprehensive knowledge of HIV, individuals with multiple sexual partners, and male-headed households. Educating these groups about the importance of HIV testing, providing accessible testing facilities, and utilizing media for awareness campaigns can help increase testing rates, facilitate early diagnosis and treatment, and ultimately contribute to the prevention and control of HIV in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Data availability

The raw data set used and analyzed in this study can be accessed from the DHS website (http://www.measuredhs.com).

Abbreviations

- AIC:

-

Akaike’s information criterion

- AOR:

-

Adjusted odds ratio

- COR:

-

Crude odds ratio

- DHS:

-

Demographic and Health Survey

- GVIF:

-

Generalized Variance Inflation Factor

- HIV/AIDS:

-

Human Immunodeficiency Virus /Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome

- HIV:

-

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

- ICC:

-

Intra-class correlation coefficient

- ICF:

-

International Center for Research on Women

- IR:

-

Individual Recode

- IRB:

-

Institutional Review Board

- LR:

-

Log-likelihood Ratio

- MOR:

-

Median Odds Ratio

- MR:

-

Micro Recode

- PCV:

-

Proportional change in variance

- PLWHA:

-

People Living With HIV/AIDS

- PLWHIV:

-

People Living With HIV

- SSA:

-

Sub-Saharan Africa

- STI:

-

Sexually Transmitted Infection

- USAIDS:

-

Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

World Health Organization. HIV/AIDS World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa 2023.

Mahy M et al. HIV estimates through 2018: data for decision-making, 2019, LWW. pp. S203-S211.

Kautako-Kiambi M et al. Voluntary counseling and testing for HIV in rural area of Democratic Republic of the Congo: knowledge, attitude, and practice survey among service users. Journal of Tropical Medicine, 2015. 2015.

World Health Organization. HIV/AIDS Key facts, July 2023. 2023.

Erena AN, Shen G, Lei P. Factors affecting HIV counselling and testing among Ethiopian women aged 15–49. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19(1):1–12.

Bain LE, Nkoke C, Noubiap JJN. UNAIDS 90-90-90 targets to end the AIDS epidemic by 2020 are not realistic: comment on Can the UNAIDS 90-90-90 target be achieved? A systematic analysis of national HIV treatment cascades. BMJ global health, 2017. 2(2).

Worku MG, Tesema GA, Teshale AB. Prevalence and associated factors of HIV testing among reproductive-age women in eastern Africa: multilevel analysis of demographic and health surveys. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1–9.

De Allegri M, et al. Factors affecting the uptake of HIV testing among men: a mixed-methods study in rural Burkina Faso. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(7):e0130216.

Mandiwa C, Namondwe B. Uptake and correlates of HIV testing among men in Malawi: evidence from a national population–based household survey. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19:1–8.

Salima N, Leah E, Stephen L. HIV testing among women of reproductive age exposed to intimate partner violence in Uganda. Open Public Health J, 2018. 11(1).

Adugna DG, Worku MG. HIV testing and associated factors among men (15–64 years) in Eastern Africa: a multilevel analysis using the recent demographic and health survey. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):1–9.

Musonda E, et al. Prevalence of HIV testing uptake among the never-married young men (15–24) in sub-saharan Africa: an analysis of demographic and health survey data (2015–2020). PLoS ONE. 2023;18(10):e0292182.

Nkambule BS, et al. Factors associated with HIV-positive status awareness among adults with long term HIV infection in four countries in the East and Southern Africa region: a multilevel approach. PLOS Global Public Health. 2023;3(12):e0002692.

Zegeye B et al. HIV testing among women of reproductive age in 28 sub-saharan African countries: a multilevel modelling. Int Health, 2023: p. ihad031.

Alem AZ, et al. Determinants of HIV voluntary counseling and testing: a multilevel modelling of the Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey. BMC Womens Health. 2022;22(1):1–10.

Asresie MB, Worku GT, Bekele YA. HIV Testing Uptake Among Ethiopian Rural Men: Evidence from 2016 Ethiopian Demography and Health Survey Data. HIV/AIDS-Research and Palliative Care, 2023: p. 225–34.

Organization WH. Guidance on provider-initiated HIV testing and counselling in health facilities. 2007.

UNAIDS, Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). Fast-track: end-ing the AIDS epidemic by 2030. 2014.

UNAIDS, Global AIDS. Update—Seizing the moment—Tackling entrenched inequalities to end epidemics. Published online. 2020. 2020: p. 384.

World Health Organization. Global health sector strategies on, respectively, HIV, viral hepatitis and sexually transmitted infections for the period 2022–2030. 2022.

Janssen RS. Implementing HIV screening. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(Supplement4):S226–31.

Laurent C. Commentary: HIV testing in low-and middle-income countries: an urgent need for scaling up. public health policy. 34: pp. 17–21.

Tetteh JK, et al. Comprehensive HIV/AIDS knowledge and HIV testing among men in sub-saharan Africa: a multilevel modelling. J Biosoc Sci. 2022;54(6):975–90.

Ante-Testard PA, et al. Temporal trends in socioeconomic inequalities in HIV testing: an analysis of cross-sectional surveys from 16 sub-saharan African countries. Lancet Global Health. 2020;8(6):e808–18.

USAID. Demographic and Health Survey(DHS) Methodology.

Croft TN, Allen CK, Zachary BW et al. Guide to DHS Statistics. Rockville, Maryland, USA: ICF. 2023: p. 13.9.

Lakhe NA, et al. HIV screening in men and women in Senegal: coverage and associated factors; analysis of the 2017 demographic and health survey. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;20(1):1.

Molla G et al. Factors associated with HIV counseling and testing among males and females in Ethiopia: evidence from Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey data. J AIDS Clin Res, 2015. 6(3).

Staveteig S et al. Demographic patterns of HIV testing uptake in sub-Saharan Africa. 2013.

Dieleman JL, et al. Spending on health and HIV/AIDS: domestic health spending and development assistance in 188 countries, 1995–2015. Lancet. 2018;391(10132):1799–829.

Hensen B, et al. Universal voluntary HIV testing in antenatal care settings: a review of the contribution of provider-initiated testing & counselling. Tropical Med Int Health. 2012;17(1):59–70.

Eng CW et al. Recent HIV testing and associated factors among people who use drugs in Cambodia: a national cross-sectional study. BMJ open, 2021. 11(3).

Ssekankya V, et al. Factors influencing utilization of HIV Testing services among Boda-Boda riders in Kabarole District, Southwestern Uganda: a cross-sectional study. Biomed Res Int. 2021;2021:1–8.

Odhiambo F, et al. Factors associated with uptake of voluntary counselling and testing services among BodaBoda operators in Ndhiwa constituency, Western Kenya. Afr J Health Sci. 2012;21:133–42.

Lemin AS, et al. Factors affecting Voluntary HIV Testing among General Adult Population: a cross-sectional study in Sarawak. Malaysia J Family Reproductive Health. 2020;14(1):45.

Takarinda KC, et al. Factors associated with ever being HIV-tested in Zimbabwe: an extended analysis of the Zimbabwe Demographic and Health Survey (2010–2011). PLoS ONE. 2016;11(1):e0147828.

Kasymova S. Awareness and knowledge about HIV/AIDS among women of reproductive age in Tajikistan. AIDS Care. 2020;32(4):518–21.

Karanja JW. Factors Influencing Utilization of Voluntary Counseling and Testing Services among Kenya Ports Authority Employees in Mombasa. Kenya: COHES-JKUAT; 2018.

Heri AB, et al. Changes over time in HIV testing and counselling uptake and associated factors among youth in Zambia: a cross-sectional analysis of demographic and health surveys from 2007 to 2018. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:1–18.

Achia TN, Obayo E. Trends and correlates of HIV testing amongst women: lessons learnt from Kenya. Afr J Prim Health Care Family Med. 2013;5(1):1–10.

Musheke M, et al. A systematic review of qualitative findings on factors enabling and deterring uptake of HIV testing in Sub-saharan Africa. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):1–16.

Jung M, Arya M, Viswanath K. Effect of media use on HIV/AIDS-related knowledge and condom use in sub-saharan Africa: a cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(7):e68359.

Bertrand JT, et al. Systematic review of the effectiveness of mass communication programs to change HIV/AIDS-related behaviors in developing countries. Health Educ Res. 2006;21(4):567–97.

Obermeyer CM, et al. Socio-economic determinants of HIV testing and counselling: a comparative study in four a frican countries. Tropical Med Int Health. 2013;18(9):1110–8.

Ibrahim M, et al. Socio-demographic determinants of HIV counseling and testing uptake among young people in Nigeria. Int J Prev Treat. 2013;2(3):23–31.

Bekele YA, Fekadu GA. Factors associated with HIV testing among young females; further analysis of the 2016 Ethiopian demographic and health survey data. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(2):e0228783.

Mafigiri R, et al. HIV prevalence and uptake of HIV/AIDS services among youths (15–24 years) in fishing and neighboring communities of Kasensero, Rakai District, South Western Uganda. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:1–10.

Mahande MJ, Phimemon RN, Ramadhani HO. Factors associated with changes in uptake of HIV testing among young women (aged 15–24) in Tanzania from 2003 to 2012. Infect Dis Poverty. 2016;5(05):64–75.

Seidu A-A, et al. Women’s healthcare decision-making capacity and HIV testing in sub-saharan Africa: a multi-country analysis of demographic and health surveys. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1–11.

Sharma M, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of community and facility-based HIV testing to address linkage to care gaps in sub-saharan Africa. Nature. 2015;528(7580):S77–85.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge ICF for Granting access to the use of the 2015-2022 Demo-graphic and Health Survey (DHS) data for this study.

Funding

No specific fund was received for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KGS, KUM, and BLS were involved in the conception and design of the study, acquisition, and analysis of data, interpretation of the results, and drafting of the manuscript. AAL, TMT, AHS, BFK, ZAA, HAA, BMF, and YSA substantially participated in the analysis of data, interpreta-tion of the results, and drafting and revising of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript and agreed to take responsibility for the contents of this work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sabo, K.G., Seifu, B.L., Kase, B.F. et al. Factors influencing HIV testing uptake in Sub-Saharan Africa: a comprehensive multi-level analysis using demographic and health survey data (2015–2022). BMC Infect Dis 24, 821 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-024-09695-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-024-09695-1