Abstract

Background

Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis is a rare entity which can be a result from autoimmune diseases, caused by various medications and infections.

Case presentation

We herein present the case of a 62-year-old male patient who presented with fatigue and was found to have severe anemia, impaired renal function, and nephrotic syndrome. A renal biopsy revealed membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (MPGN) of the immune complex type with activation of the classical complement pathway. Further investigations led to the diagnosis of a chronic Coxiella burnetii-infection (Q fever), likely acquired during cycling trips in a region known for intensive sheep farming. Additionally, the patient was found to have a post endocarditic destructive bicuspid aortic valve caused by this pathogen. Treatment with hydroxychloroquine and doxycycline was administered for a duration of 24 months. The aortic valve was replaced successfully and the patient recovered completely.

Conclusions

Early detection and targeted treatment of this life-threatening disease is crucial for complete recovery of the patient.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (MPGN) is a pattern of glomerular injury which can be divided in two groups based on the immunofluorescence/immunohistochemical findings [1]. The current classification defines a complement-dominant subgroup, called C3 glomerulopathy, and an immunoglobulin dominant subgroup, with or without complement, called immune complex type. When MPGN is characterized by an immunoglobulin-positive pattern, regardless of the presence of complement, evaluation for chronic infection, autoimmune disease, and monoclonal gammopathy should be done [2]. The first two of these can lead to antigenemia, circulating immune complexes, and immune complex deposition in glomeruli [3]. Antigen–antibody immune complexes result from chronic infections and autoimmune diseases can be associated with elevated levels of circulating immune complexes. Glomerular deposition in case of monoclonal gammopathies are caused by paraproteinemias.

Case presentation

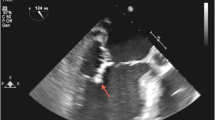

A 62-year-old male patient presented to the hospital with a six-month history of fatigue and malaise. On examination, the patient was well-oriented but was ill-looking. His vitals included a temperature of 36 °C, heart rate of 102 beats per minute, blood pressure of 145/96 mm Hg, and saturation of 98% in room air. Laboratory investigations revealed severe anemia (hemoglobin: 6.4 g/dL), normal C-reactive protein (0.5 mg/dL), and impaired renal function (estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR): 13 mL/min/1.73 m2). Clinically, the patient exhibited features of nephrotic syndrome with a urine albumin to creatinine ratio (UACR) of 8.2 g/g creatinine and hematuria. The patient reported extensive cycling trips in the northwestern region of Germany, known for intensive sheep farming. To further investigate the underlying cause of the nephrotic syndrome, a renal biopsy was performed, which confirmed membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (MPGN) of the immune complex type with activation of the classical complement pathway (Fig. 1). As part of the differential diagnostic workup, an echocardiogram was performed, revealing a post-endocarditic destructive bicuspid aortic valve. In accordance to these findings, no fresh vegetations were detected and blood cultures remained negative.

Morphological findings of the renal biopsy: A Periodic acid Schiff stained sections revealed a membranoproliferative pattern of glomerulonephritis with lobulation of the glomerular tuft, mesangial and endocapillary hypercellularity and double contours of the basement membrane. B Electron microscopy shows abundant electron dense deposits (asterisks) between the basement membrane and newly formed membranes. C Immunohistochemical staining for immunoglobulin G with strong positivity compared to only mild immunohistochemical positivity for complement C3 (D). C1q also showed a strong immunohistochemical staining (Supplementary Fig. 1)

Serological testing confirmed a chronic infection with Coxiella burnetii (C. burnetii) by using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) with the following results: IgG phase I: 1:8192; IgM phase I: 1:128; IgG phase II: 1:16,000; IgM phase II: 1:256. These findings were consistent with chronic Q fever, which was likely acquired during the patient's contact with sheep farming. The complement C3c level was in the normal range of 0.99 g/L (0.9 – 1.7). There was no evidence of hepatitis B, C, or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Antinuclear antibodies were nonspecifically positive with a titre of 1:1280. Double stranded DNA (dsDNA) antibodies, extractable nuclear antigen (ENA) and cryoglobulins were negative. The patient was started on a treatment regimen consisting of hydroxychloroquine (3 × 200 mg/day) and doxycycline (2 × 100 mg/day) for a duration of 24 months.

In regards to the bicuspid stenotic aortic valve, the patient underwent aortic valve replacement and recovered very well after a rehabilitation period of 8 weeks.

The patient was advised to undergo regular monitoring, including therapeutic drug level measurements, ophthalmologic examinations, and serological tests at quarterly intervals. This was essential to ensure appropriate medication dosing, monitor for potential ocular side effects, and assess treatment response.

The patient exhibited complete clinical recovery and showed considerably improved kidney function with an eGFR of 43 mL/min/1.73 m2 and a UACR of 90 mg/g two years after the initial presentation.

Discussion and conclusions

We herein describe a rare case of an immune-complex-mediated MPGN resulting from a C. burnetii endocarditis of a bicuspid aortic valve.

C. burnetii is a bacterium causing Q fever, a worldwide occurring zoonotic disease. It is an obligate intracellular, pleomorphic, Gram-negative bacterium with high infectivity and worldwide distribution. The main reservoir for human infection consists of farm animals such as sheep, cattle, and goats [4]. Moreover, Celina et al. postulated ticks as a potential risk factor for coxiellosis in livestock [5].

Humans get infected through inhalation of C. burnetii contaminated aerosols expelled by infected animal feces, urine, milk, and birth products [5]. Hence, farm and abattoir workers are exposed to an increased risk of infection. Although a majority of patients stays misdiagnosed or asymptomatic, clinical symptoms can vary from fever, respiratory distress, fatigue, arthralgia, hepatitis, pericarditis, myocarditis, endocarditis, pancreatitis, neurological disorder, skin rash, and others [6].

Life-threatening courses have been primarily described in chronic Q fever with endocarditis [7]. Since people with preexisting valvular heart disease, like the patient reported here, have a considerably increased risk of endocarditis, serological testing for C. burnetii is recommended when blood cultures are negative [8, 9].

Among patients with valvular defects who suffer from Q fever, about 40% develop endocarditis, especially in case of prosthetic valves [10]. But even in native valve diseases, the susceptibility for endocarditis seems to be higher with bicuspid aortic valves compared to secundum atrial septal defect, patent ductus arteriosus, and pulmonary valve stenosis [11].

Infection-related MPGN patterns can be found in various viral and bacterial infections [12, 13]. Bacterial-related immune-complex MPGN have been described in infections including staphylococcus, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, streptococci, Propionibacterium acnes, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, brucella, C. burnetii, nocardia, and meningococcus [1]. In deed only a few cases are known which describe MPGN induced by C. burnetii endocarditis [14,15,16].

A constant light microscopy finding in previous case reports with Q fever and glomerulonephritis is mesangial expansion and glomerular hypercellularity (either mesangial or endocapillary) [15]. Histological changes that are typical for MPGN have been rarely described in Q fever. In our case light microscopy revealed lobulated glomeruli with mesangial proliferation and double contours of the capillary wall as hallmarks of MPGN. Immunohistochemistry showed granular IgG depositions along the capillary walls and the mesangium. Corresponding electron dense subendothelial deposits were detected by electron microscopy. A recently published case by Leclerc et al. described a patient with chronic Q fever and an MPGN with a full house pattern on immunofluorescence with positivity for IgA, IgM, IgG, C3, C1q, kappa and lambda as occasionally found in lupus nephritis [15]. Interestingly, tests for antinuclear and antiphospholipid antibodies showed negative results in their study. In line with these data, the antinuclear antibodies in our study also showed only nonspecific positivity.

Based on the current understanding of the pathological mechanisms, the association between chronic endocarditis caused by C. burnetii and the development of MPGN lies in the persistent antibody formation. These antibodies are produced due to chronic inflammation and deposit as immune precipitates in the glomerulus. An antigen–antibody reaction with glomerular structures has not been described in this context so far.

Previous reports on renal disease in chronic Q fever described proteinuria values in a range from 0.7–4.0 g/d. In our case, urinalysis showed a considerably higher UACR of 8.2 g/g creatinine.

To the best of our knowledge this is the first case of a patient with the coincidence of a chronic C. burnetii-infected native bicuspid aortic valve and a severe MPGN with a UACR of 8.2 g/g creatinine.

This case highlights a C. burnetii-infection causing the destruction of a bicuspid aortic valve and the induction of an immune-complex mediated MPGN. It underscores the importance of considering rare infectious etiologies in patients with blood culture-negative fever, unexplained acute kidney injury and a stay in a high-risk environment. Early recognition and appropriate treatment are crucial for optimizing patient outcomes in such complex cases.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- C. burnetii:

-

Coxiella burnetiid

- ds-DNA:

-

Double stranded DNA

- eGFR:

-

Estimated glomerular filtration rate

- ENA:

-

Extractable nuclear antigen

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- Ig:

-

Immunoglobulin

- MPGN:

-

Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis

- Q fever:

-

Query fever

- UACR:

-

Urine albumin to creatinine ratio

References

Sethi S, Fervenza FC. Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis–a new look at an old entity. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(12):1119–31.

Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes Glomerular Diseases Work G. KDIGO 2021 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Glomerular Diseases. Kidney Int. 2021;100(4S):S1–S276.

Fervenza FC, Sethi S, Glassock RJ. Idiopathic membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis: does it exist? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27(12):4288–94.

Pouquet M, Bareille N, Guatteo R, Moret L, Beaudeau F. Coxiella burnetii infection in humans: to what extent do cattle in infected areas free from small ruminants play a role? Epidemiol Infect. 2020;148:e232.

Celina SS, Cerny J. Coxiella burnetii in ticks, livestock, pets and wildlife: A mini-review. Front Vet Sci. 2022;9:1068129.

Christodoulou M, Malli F, Tsaras K, Billinis C, Papagiannis D. A Narrative Review of Q Fever in Europe. Cureus. 2023;15(4):e38031.

Grey V, Simos P, Runnegar N, Eisemann J. Case report: a missed case of chronic Q fever infective endocarditis demonstrating the ongoing diagnostic challenges. Access Microbiol. 2023;5(11):000628.v3.

Bozza S, Graziani A, Borghi M, Marini D, Duranti M, Camilloni B. Case report: Coxiella burnetii endocarditis in the absence of evident exposure. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023;10:1220205.

Delgado V, Ajmone Marsan N, de Waha S, Bonaros N, Brida M, Burri H, et al. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of endocarditis. Eur Heart J. 2023;44(39):3948–4042.

Fenollar F, Fournier PE, Carrieri MP, Habib G, Messana T, Raoult D. Risks factors and prevention of Q fever endocarditis. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33(3):312–6.

Kuijpers JM, Koolbergen DR, Groenink M, Peels KCH, Reichert CLA, Post MC, et al. Incidence, risk factors, and predictors of infective endocarditis in adult congenital heart disease: focus on the use of prosthetic material. Eur Heart J. 2017;38(26):2048–56.

Wajid S, Farrukh L, Rosenberg L, Faiz M, Singh G. Systemic Haemophilus parainfluenzae Infection Manifesting With Endocarditis and Membranoproliferative Glomerulonephritis. Cureus. 2023;15(6):e41086.

Guo S, Kapp ME, Beltran DM, Cardona CY, Caster DJ, Reichel RR, et al. Spectrum of Kidney Diseases in Patients With Hepatitis C Virus Infection. Am J Clin Pathol. 2021;156(3):399–408.

Vacher-Coponat H, Dussol B, Raoult D, Casanova P, Berland Y. Proliferative glomerulonephritis revealing chronic Q fever. Am J Nephrol. 1996;16(2):159–61.

Leclerc S, Royal V, Dufresne SF, Mondesert B, Laurin LP. Membranoproliferative Glomerulonephritis in a Patient With Chronic Q Fever. Kidney Int Rep. 2020;5(12):2393–8.

Dathan JR, Heyworth MF. Glomerulonephritis associated with Coxiella burnetii endocarditis. Br Med J. 1975;1(5954):376–7.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

We report received no funding for writing this case report.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ML and GT collected the clinical data. ML treated the patient. TW prepared the pathology specimens and performed the pathological diagnosis. ML, GT and SR contributed to the interpretation of the patient’s clinical course. GT and SR wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the preparation of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

We informed the patient that we would protect his personal information and privacy in reporting this case, and we obtained his written informed consent. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Loyen, M., Wiech, T., Reuter, S. et al. Case report: membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis associated with Q fever causing chronic endocarditis. BMC Nephrol 25, 291 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-024-03694-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-024-03694-9