Abstract

Background

Worldwide, a significant proportion of head and neck cancers is attributed to the Human papillomavirus (HPV). It is imperative that we acquire a solid understanding of the natural history of this virus in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) development. Our objective was to investigate the role of sexual behaviour in the occurrence of HNSCC in the French West Indies. Additionally, we evaluated the association of high risk of HPV (Hr-HPV) with sexual behaviour in risk of cancer.

Methods

We conducted a population-based case-control study (145 cases and 405 controls). We used logistic regression models to estimate adjusted odds-ratios (OR), and their 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Results

Compared to persons who never practiced oral sex, those who practiced at least occasionally had a lower HNSCC risk. First sexual intercourse after the age of 18 year was associated with a 50% reduction of HNSCC risk, compared to those who began before 15 years. HNSCC risk was significantly reduced by 60% among persons who used condoms at least occasionally. The associations for ever condom use and oral sex were accentuated following the adjustment for high-risk HPV (Hr-HPV). Oral Hr-HPV was associated with several sexual behaviour variables among HNSCC cases. However, none of these variables were significantly associated with oral HPV infections in the population controls.

Conclusion

First intercourse after 18 years, short time interval since last intercourse and ever condom use were inversely associated with HNSCC independently of oral Hr-HPV infection. Sources of transmission other than sexual contact and the interaction between HPV and HIV could also play a role in HNSCC etiology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Head and neck cancer is a public health concern across the world, counting 700,000 new cases every year [1]. This incidence is particularly elevated in Guadeloupe and Martinique which have one of the highest rates among men in Latin America and the Caribbean [1, 2] despite low prevalence of tobacco and alcohol [3]. Oral HPV infection is a prominent risk factor of head and neck cancer.

The incidence of HPV-positive head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) has increased considerably in the past decade [4]. Consequently, to implement effective prevention we require a solid understanding of the natural history of HPV in HNSCC. In spite of the biological similarities to cervical cancer, the etiological pathway in regards to sexual behaviour and oral HPV infection is less clear in HNSCC [5, 6]. Sexual behaviour, including oral sex and other at-risk and promiscuous behaviour have been consistently regarded as plausible drivers of oral HPV infection which in turn provoke HNSCC [7, 8]. We have previously demonstrated a significant association with oral high-risk HPV (Hr-HPV) [9]. Oral Hr-HPV was associated with a two-fold increase in the risk of HNSCC.

However, results from previous studies on sexual behaviour and HNSCC are sometimes conflicting, and few data exist on this topic in populations of African descent [8]. In the current paper we proposed an analysis investigating the association between sexual behaviour and the occurrence of HNSCC in the French West Indies (FWI), and the role of oral Hr-HPV in this association.

Method

Study population, data and specimen collection

We conducted a population-based case-control study in Guadeloupe and Martinique. The study is an extension of a large nationwide case-control study, the ICARE study, which has already been conducted in ten French regions covered by a cancer registry [10]. The study in the FWI used the same protocol and questionnaire, described in detail elsewhere [10, 11], with some adaptations to the local context. Eligible cases were patients residing in the FWI, suffering from a primary, malignant tumour of the oral cavity, pharynx, sinonasal cavities and larynx of any histological type, aged between 18 and 75 years old at diagnosis, newly diagnosed and histologically confirmed between April 1, 2013 and June 30, 2016. Incident cases were identified in collaboration with the population-based cancer registries of Guadeloupe and Martinique which use standardized procedures for the recording of all cancer cases in each of these regions. Our study benefitted from the diverse data sources from the registries in order to flag new cases diagnosed during the study period.

The control group was selected from the general population by random digit dialling, using incidence density sampling method. Controls were frequency matched to the cases by sex, age and region. Additional stratification was used to achieve a distribution by socioeconomic status among the controls comparable to that of the general population.

Cases and controls were interviewed face-to-face with a questionnaire including sociodemographic characteristics, lifetime tobacco and alcohol consumption and sexual behaviour. Participants were also asked to provide a saliva sample, using the Oragene® OG-500 kit (DNA Genotek).

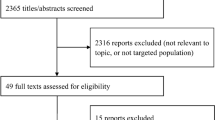

Among the 235 eligible cases, 170 (72.3%) agreed to participate and were interviewed. Among the 497 eligible controls, 405 (81.5%) answered the questionnaire. Among cases and controls with interview data, 114 cases (67.1%) and 311 controls (76.8%) provided a saliva sample. Each subject included in the study gave a written and informed consent. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the French National Institute of Health and Medical Research (IRB INSERM n°01–036) and by the French Data Protection Authority (n° DR-2015-2027).

HPV detection and genotyping

HPV detection in tumours is informative on the involvement of HPV in cancer development. Given the participation of healthy individuals, we resorted to detection of HPV-integrated DNA from saliva samples for both cases and controls. Compared to HPV detection from tumour tissue, the method using saliva still has good specificity [12]. We performed HPV detection using the INNO-LiPA ® kit, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (INNO-LiPA HPV Genotyping Extra; Innogenetics, Ghent, Belgium). The INNO-LiPA HPV genotyping assay allows the detection of the following genotypes: HPV16, HPV18, HPV31, HPV33, HPV35, HPV39, HPV45, HPV51, HPV52, HPV56, HPV58, HPV59, HPV68 (High-risk), HPV26, HPV53, HPV66, HPV70, HPV73, HPV82 (Probable high-risk), HPV06, HPV11, HPV40, HPV42, HPV43, HPV44, HPV54, HPV61, HPV81 (Low-risk), HPV62, HPV67, HPV83, HPV89 (Other). The full details on the method for HPV detection has been described elsewhere [11].

Collection of data on sexual behaviour

Lifetime sexual behavior was ascertained during the face-to-face interviews. The questionnaire included questions pertaining to the number of lifetime sex partners, sexual orientation and whether or not the last sexual intercourse took place in the last 6 months prior to the interview. Participants were asked if they ever performed certain sexual practices and the frequency at which they did them. These sexual practices were condom use, oral sex practice, whether or not the participants had ever received sperm in their mouth. The age at which these acts were last practiced was also noted. Information on having multiple partners, sexual intercourse in exchange for money and sexually transmitted infections (STI) were also collected. Oral sex was defined as the contact between the participant’s mouth and their partner’s genitalia. Having multiple partners was defined as having several sexual partners during the same period. When the frequency of an activity was requested, four responses were possible: just once, sometimes, often, always or almost always. We considered “occasional” behaviour to be “once” or “sometimes”.

Sampling

We restricted the current analysis to squamous cell carcinomas of the oral cavity (International Classification of Diseases 10th revision codes C00.3-C00.9, C02.0-C02.3, C03.0, C03.1, C03.9, C04.1, C04.8, C04.9, C05.0, C06.0-C06.2, C06.8 and C06.9, n = 35), the oropharynx (ICD-10 codes C01.9, C02.4, C05.1, C05.2, C09, C10, C 14.2, n = 58), the hypopharynx (ICD-10 codes C12- C13, n = 19) and the larynx (ICD-10 codes C32, n = 32). Our analysis included 145 cases and 405 controls.

Statistical analysis

The association between sexual behaviour variables and the occurrence of HNSCC, and oral Hr-HPV infection was assessed by estimating odds ratios (ORs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs), using logistic regression models. Regression analyses were adjusted for age, sex and region, tobacco, alcohol and education level. Tobacco was accounted as one variable combining the quantity (the average number of cigarettes per day over one’s lifetime) and the duration of lifetime smoking.

In order to assess the role of Hr-HPV as a mediator in the relationship between sexual behaviour and HNSCC we performed logistic regressions with Hr-HPV as a covariate as well as reproducing the initial analyses by Hr-HPV subgroups (Hr-HPV-negative and Hr-HPV-positive). Oral Hr-HPV status was assessed as Hr-HPV-positive versus Hr-HPV-negative, the latter category grouping HPV-negative and non-high-risk-HPV genotypes. The association of sexual behaviour and head and neck cancer is supposedly mediated by Hr-HPV. We wanted to assess whether the effect of the sexual behaviour could be explained at least partially by Hr-HPV (hypothesised mediator) [13]. Assuming that Hr-HPV is on the causal pathway to head and neck cancer, we considered HPV as a mediator when the association between sexual behaviour and HNSCC dissipated in the Hr-HPV-positive subgroup. Hr-HPV was also regarded as a mediator when the adjustment for Hr-HPV resulted in the loss of the initial significant association.

We also studied the associations between sexual behaviour and oral Hr-HPV infection separately among population controls and HNSCC cases.

Results

Characteristics of the study population

The 55–64 years age group that was most represented in our sample (cases: 42%, controls: 32%). Majority of the study participants were men (cases: 88%, controls:76%). There were more participants from Guadeloupe than Martinique.

Sexual behaviour and head and neck cancer

Last intercourse beyond 6 months preceding the interview was positively associated with the occurrence of HNSCC (Table 1). Having sexual intercourse after the age of 18 year was associated with a 60% risk reduction, compared to those who began before 15 years. Similarly, HNSCC risk was significantly reduced by 50% among persons who used condoms at least occasionally (once, sometimes). After adjustment for main confounding variables, condom users were twice as likely to have engaged in sexual intercourse in the 6 months prior to their interview compared to never condom users (OR = 2.52, 95% CI = 1.51–4.18) (Data not shown). Receiving money for performing sexual intercourse was uncommon in our study, there were only 6 controls who responded “yes”, and represented 1% of the general population. Oral sex, lifetime sex partners, sexual orientation, paying for sex, and having multiple partners were not associated with HNSCC.

We were interested in the role of Hr-HPV in the mediation of the associations between certain sexual behaviours and HNSCC from our analyses (Table 2). The associations observed for age at first intercourse were unchanged after adjusting for Oral Hr-HPV. Stratification was not possible for this variable because of too few subjects in the Hr-HPV-positive group. Nonetheless, the HPV-adjusted ORs for age at first intercourse were similar to that of the Hr-HPV-negative group. The associations for time since last intercourse, ever condom use and oral sex were accentuated following the adjustment for Hr-HPV. In addition, the significant associations between condom use, time since last intercourse and HNSCC appeared only in Hr-HPV-negative HNSCC whereas the association with oral sex remained non-significant regardless of HPV status.

We studied these behaviours more closely. Age at first intercourse remained significantly associated only among persons who never used condoms. Similarly, the significant association disappeared following the adjustment on ever condom use (Table 3). Higher numbers of partners was not associated with HNSCC regardless of oral sex frequency (Table S1).

We were also examined the association between Hr-HPV and HNSCC risk taking into account significant sexual behaviour variables individually and in different combinations as covariates in the multivariate model (Table S2). This helps to verify potential confounding effects between sexual behaviour variables of on HNSCC risk. The introduction of ever condom use, and/or oral sex tended to increase slightly the association between Hr-HPV and HNSCC risk (relative variation = 15–26%) contrarily to age at first sexual intercourse which caused a slight decrease.

Oral HPV and sexual behaviour in population controls and in HNSCC cases

After adjusting for confounding factors, none of the sexual behaviour variables studied in the current paper were significantly associated with oral HPV infections in controls (Table 4).

In contrast, the associations between sexual behaviour and oral Hr-HPV infections were consistently more apparent in HNSCC cases. Cases who had a sexual debut between the ages of 15–18 years were significantly less likely to be positive for Hr-HPV. Non-heterosexuals cases were significantly more likely to have an oral Hr-HPV infection when compared to heterosexuals. Practicing oral sex regularly (often or always) was associated with Hr-HPV positivity when compared to cases who never practiced. Cases were significantly more likely to be positive for Hr-HPV when they had multiple sexual partners simultaneously from more than 5 years preceding the interview.

Discussion

This is the first study addressing sexual behaviour and HNSCC in an Afro-Caribbean population. The data from our study revealed significant associations between age at first intercourse condom use, time since last sexual intercourse, and HNSCC risk. We were also interested in the association between oral Hr-HPV infection and sexual behaviour. we found no clear association among the population controls with any of the sexual behaviour variables studied. Case-to-case comparisons however, yielded evidence that is in favour of an association between risky sexual behaviour and oral Hr-HPV infection.

Oral sex and number of sexual partners [7, 14] were not associated with HPV transmission and HNSCC in our study. However, we highlighted associations with other sexual behaviour indicators. We found a significant protective association between ever condom use and HNSCC, similarly to another case-control study on oropharyngeal cancer [15].

Regarding age at first sexual intercourse, we observed a greater risk of HNSCC among subjects with sexual debut at a younger age compared to a sexual debut after the age of 18. These findings coincided with other studies [15, 16]. The observed association with age at first intercourse disappeared after adjusting for ever condom use, and in subgroup analysis among persons who used condoms regularly (often of always). On the other hand, this significant association was maintained in the subgroup of person who used condoms very inconsistently or not at all; thus, reinforcing the evidence that association between age at sexual debut and HNSCC is mediated by risky sexual habits [17].

We did not find any evidence of associations with sexual behaviour mediated by oral Hr-HPV infections. Indeed, ever condom use was significantly associated with a reduction in HNSCC risk; however, this association was attenuated neither after adjusting for Hr-HPV nor in Hr-HPV-negative subjects alone. Furthermore, the association between condom use and oral Hr-HPV in both control and cases was non-significantly negative. Contrarily to a Canadian study [14], our results allude to a risk reduction by condom use which is independent of oral Hr-HPV infections.

We studied sexual behaviour and oral Hr-HPV infections. On one hand, we did not highlight any clear association in the control group. Although non-significant, oral sex appeared to increase the risk of Hr-HPV infections in population controls which coincided with a previous study [14]. Given the absence of significant association with sexual behaviour and Hr-HPV in population controls, other factors such as fomites or self-inoculation could be considered as means of contamination in the general population [18]. On the other hand, sexual behaviour was consistently associated higher risk of oral Hr-HPV infection among our cases. We adjusted for the main confounding factors but we cannot rule out residual confounding. In particular, we did not have any data on HIV infection. In light of the risky behaviour among cases, the association with oral Hr-HPV and HNSCC may be driven by an HIV infection.

Concerning the link between sexual behaviour and HNSCC, participants who did not have sexual intercourse in the past 6 months were significantly more likely to have HNSCC. There were no studies which looked at this particular variable [8]. However, the lack of sexual intercourse from the last 6 months among cases could have arisen from bodily changes linked to their cancer. These bodily changes could reduce their desire to initiate in sexual intercourse [19]. Moreover, the presence of an STI is also a plausible hypothesis for this association with recent sexual intercourse as it has been shown to reduce sexual risk behaviour [20, 21]. In the FWI, the latter is probable because of high HIV-seropositivity [22]. HIV is known to be associated with greater HPV prevalence and can potentiate the carcinogenic activity of an HPV infection. The greater odds of Hr-HPV infection through sexual behaviour among cases might be explained by HIV induced immunodeficiency [23,24,25,26,27,28].

Our study presents several limitations. Our findings are exposed to the possibility of a recall bias due to the retrospective nature of the case-control design. Furthermore, we had a small sample size and we were not able to perform analyses by anatomical subsite. This also limited stratified analyses by Hr-HPV status. The Hr-HPV-positive subgroup was particularly small. Confidence intervals for this group were wide and in certain instances, estimates were not computed.

In addition, sexual behaviour in the Caribbean is regarded as a taboo [29] and could induce misclassification bias; in particularly, in regards to number of sexual partners. Our sample comprising mainly men, the average number of sexual partners may be more likely to be overestimated [30]. In terms of sexual orientation, homosexuality is thought to be underestimated in our sample because of discrimination faced by this group in the FWI [31]. Furthermore, the use of oral HPV detection to assess the Hr-HPV status may have caused misclassification. Oral HPV detection has been shown to have good specificity but moderate sensitivity for HPV-positive HNSCC tumours [12].

Despite these limitations in HPV detection, our study still provides valid knowledge on the association between sexual behaviour and HNSCC, and also oral HPV infection in this specific population. During our study, we did not collect any information on HIV status which is a factor suspected to modify the natural history of HPV in HNSCC [27]. The link between HNSCC and sexual behaviour could be further explained by HIV considering its high prevalence HIV in the FWI [22]. Selection bias may not be ruled out but is thought to be kept to minimum in the present analysis. There were more missing data in cases than in controls; however, we do not believe that omission of this part of the questionnaire was linked to sexual behaviour. In addition, the questions pertaining to sexual behaviour were at the end of the questionnaire, and cases tended to end the interview prior to those questions more often than controls due to fatigue. 27% of the data for HPV were missing in our sample; hence, this reduced statistical power in our analyses involving HPV. Comparison with cases from the cancer registries showed that our cases in our study had similar distribution for sex, age and cancer sites. Our controls can be considered representative of persons of the general population of similar age and sex. Indeed, a previous study has demonstrated that our method produces an unbiased sample of controls [10]. We also established the representativeness of our population controls after comparing our observed distribution for tobacco, alcohol and sexual behaviour with that of a national health survey [3] and a regional survey [32].

Sexual behaviour is a modifiable risk factor; therefore, there may be additional opportunities to prevent HNSCC in the FWI [33] in light of our new results. A greater understanding of biological mechanisms between HIV and other viral agents in head and neck cancer could inform clinical practice and cancer control policy. These new data can also apply to other Afro-Caribbean populations for which information on this topic is scarce.

Conclusion

This is the first study to investigate the role of sexual behaviour in the occurrence of HNSCC in an Afro-Caribbean population while taking into account oral HPV infections. Despite our study limitations, first intercourse after 18 years, short time intervals since last intercourse and never condom use were inversely associated with HNSCC independently of oral Hr-HPV infection. Oral Hr-HPV infections were associated with riskier sexual behaviour in HNSCC cases but not in population controls. Other sources of contamination such as fomites, as well as HIV infections could play a role in the causal pathway to HNSCC. Further investigation on this topic in the FWI is warranted and special attention should be given to the interaction between viral factors to better substantiate the natural history of HPV in HNSCC thus, providing additional prospects for prevention.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- FWI:

-

French West Indies

- HNSCC:

-

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma

- HPV:

-

Human papillomavirus

- Hr-HPV:

-

High-risk Human papillomavirus

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

References

Ferlay J, Ervik M, Lam F, Colombet M, Mery L, Piñeros M et al. Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer. 2020. http://gco.iarc.fr/today/home. Accessed 23 Aug 2020.

Auguste A, Gathere S, Pinheiro PS, Adebamowo C, Akintola A, Alleyne-Mike K, et al. Heterogeneity in head and neck cancer incidence among black populations from Africa, the Caribbean and the USA: analysis of cancer registry data by the AC3. Cancer Epidemiol. 2021;75:102053.

Auguste A, Dugas J, Menvielle G, Barul C, Richard J-B, Luce D. Social distribution of tobacco smoking, alcohol drinking and obesity in the french West Indies. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:1424.

Chaturvedi AK, Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, Hernandez BY, Xiao W, Kim E, et al. Human papillomavirus and rising Oropharyngeal Cancer incidence in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4294–301.

Alexander ER. Possible etiologies of Cancer of the Cervix Other Than Herpesvirus. Cancer Res. 1973;33:1485–90.

Gillison ML, Alemany L, Snijders PJF, Chaturvedi A, Steinberg BM, Schwartz S, et al. Human Papillomavirus and Diseases of the Upper Airway: Head and Neck Cancer and Respiratory papillomatosis. Vaccine. 2012;30:F34–54.

Farsi NJ, El-Zein M, Gaied H, Lee YCA, Hashibe M, Nicolau B, et al. Sexual behaviours and head and neck cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol. 2015;39:1036–46.

Chancellor JA, Ioannides SJ, Elwood JM. Oral and oropharyngeal cancer and the role of sexual behaviour: a systematic review. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdoe.12255.

Auguste A, Deloumeaux J, Joachim C, Gaete S, Michineau L, Herrmann-Storck C, et al. Joint effect of tobacco, alcohol, and oral HPV infection on head and neck cancer risk in the french West Indies. Cancer Med. 2020;9:6854–63.

Luce D, Stücker I, ICARE Study Group. Investigation of occupational and environmental causes of respiratory cancers (ICARE): a multicenter, population-based case-control study in France. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:928.

Auguste A, Gaëte S, Herrmann-Storck C, Michineau L, Joachim C, Deloumeaux J, et al. Prevalence of oral HPV infection among healthy individuals and head and neck cancer cases in the french West Indies. Cancer Causes Control. 2017;28:1333–40.

Gipson BJ, Robbins HA, Fakhry C, D’Souza G. Sensitivity and specificity of oral HPV detection for HPV-positive head and neck cancer. Oral Oncol. 2018;77:52–6.

Richiardi L, Bellocco R, Zugna D. Mediation analysis in epidemiology: methods, interpretation and bias. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42:1511–9.

Laprise C, Madathil SA, Schlecht NF, Castonguay G, Soulières D, Nguyen-Tan PF, et al. Increased risk of oropharyngeal cancers mediated by oral human papillomavirus infection: results from a canadian study. Head Neck. 2019;41:678–85.

D’Souza G, Kreimer AR, Viscidi R, Pawlita M, Fakhry C, Koch WM, et al. Case-control study of human papillomavirus and oropharyngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1944–56.

Schwartz SM, Daling JR, Doody DR, Wipf GC, Carter JJ, Madeleine MM, et al. Oral cancer risk in relation to sexual history and evidence of human papillomavirus infection. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:1626–36.

Kahn JA, Rosenthal SL, Succop PA, Ho GYF, Burk RD. Mediators of the association between age of first sexual intercourse and subsequent human papillomavirus infection. Pediatrics. 2002;109:E5.

Ryndock EJ, Meyers C. A risk for non-sexual transmission of human papillomavirus? Expert Rev Anti-infective Therapy. 2014;12:1165–70.

Stanton AM, Handy AB, Meston CM. Sexual function in adolescents and young adults diagnosed with cancer: a systematic review. J Cancer Surviv. 2018;12:47–63.

Eaton LA, Kalichman SC. Changes in transmission risk behaviors across stages of HIV Disease among people living with HIV/AIDS. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2009;20:39–49.

Poon CM, Wong NS, Kwan TH, Wong HTH, Chan KCW, Lee SS. Changes of sexual risk behaviors and sexual connections among HIV-positive men who have sex with men along their HIV care continuum. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0209008.

Elenga N, Georger-Sow M-T, Messiaen T, Lamaurie I, Favre I, Nacher M et al. Incidence and Risk Factors for Follow-Up Interruption of HIV-Infected Patients in Guadeloupe. 2013.

Strickler HD, Burk RD, Fazzari M, Anastos K, Minkoff H, Massad LS, et al. Natural history and possible reactivation of human papillomavirus in human immunodeficiency virus-positive women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:577–86.

Massad LS, Ahdieh L, Benning L, Minkoff H, Greenblatt RM, Watts H, et al. Evolution of cervical abnormalities among women with HIV-1: evidence from surveillance cytology in the women’s interagency HIV study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2001;27:432–42.

Kreimer AR, Alberg AJ, Daniel R, Gravitt PE, Viscidi R, Garrett ES, et al. Oral human papillomavirus infection in adults is associated with sexual behavior and HIV serostatus. J Infect Dis. 2004;189:686–98.

Beachler DC, D’Souza G. Oral HPV infection and head and neck cancers in HIV-infected individuals. Curr Opin Oncol. 2013;25:503–10.

Beachler DC, Weber KM, Margolick JB, Strickler HD, Cranston RD, Burk RD, et al. Risk factors for oral HPV infection among a high prevalence population of HIV-positive and at-risk HIV-negative adults. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21:122–33.

Abel S, Najioullah F, Voluménie J-L, Accrombessi L, Carles G, Catherine D, et al. High prevalence of human papillomavirus infection in HIV-infected women living in French Antilles and French Guiana. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0221334.

Sharpe J, Pinto S. The Sweetest Taboo: Studies of Caribbean Sexualities; A Review Essay. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society. 2006;32:247–74.

Smith TW. Discrepancies between men and women in reporting number of sexual partners: a summary from four countries. Soc Biol. 1992;39:203–11.

Chadee D, Joseph C, Peters C, Sankar VS, Nair N, Philip J. Religiosity, and attitudes towards homosexuals in a caribbean environment. Soc Econ Stud. 2013;62:1–28.

Halfen S, Lydié N. Les habitants des Antilles et de la guyane face au VIH/SIDA et à d’autres risques sexuels. Paris: Observatoire régional de santé d’ île-de-France; 2014.

Auguste A, Joachim C, Deloumeaux J, Gaete S, Michineau L, Herrmann-Storck C, et al. Head and neck cancer risk factors in the french West Indies. BMC Cancer. 2021;21:1071.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our clinical research associates Lucina Lipau and Audrey Pomier for their help in data collection.

Funding

This study was funded by the French National Cancer Institute (Institut National du Cancer) [grant number: not applicable] and the Cancéropôle Ile-de-France [grant number: not applicable]. The funding bodies had no involvement in the preparation of this article. Aviane Auguste was supported by a grant from the “Ligue contre le Cancer, comité d’Ille-et-Vilaine” for this work [grant number: not applicable].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JD, CJ, SG, SD, and DL participated in the study concept and design, and collected the data. AA, LM, and DL conducted the quality control of data. AA, SG, CH, and DL participated in the interpretation of data. AA and DL performed cleaning of final dataset, statistical analysis, and prepared the manuscript draft. All authors participated in manuscript editing, review, and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All methods were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was provided by all participants in the study and all data recorded was anonymised prior to analysis. Ethics approval was granted to this study by the French Data Protection Authority (CNIL, Commission Nationale de l’Informatique et des Libertés) no. DR-2015-2027; IRB INSERM no. 01–036.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Data sharing statement

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available since personal health data underlying the findings are protected by the French Data Protection Act. Data are however are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Additional file 1:

Sex behaviour HNC_BMC. Table S1: Number of lifetime sexual partners stratified by oral sex frequency. Table S2: The effect of Hr-HPV on HNSCC risk after adjusting for age at first intercourse, condom use and oral sex

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Auguste, A., Gaete, S., Michineau, L. et al. Association between sexual behaviour and head and neck cancer in the French West Indies: a case-control study based on an Afro-Caribbean population. BMC Cancer 23, 407 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-023-10870-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-023-10870-x