Abstract

Background

Bumetanide is a selective NKCC1 chloride importer antagonist which is being repurposed as a mechanism-based treatment for neurodevelopmental disorders (NDDs). Due to their specific actions, these kinds of interventions will only be effective in particular subsets of patients. To anticipate stratified application, we recently completed three bumetanide trials each focusing on different stratification strategies with the additional objective of deriving the most optimal endpoints. Here we publish the protocol of the post-trial access combined cohort study to confirm previous effects and stratification strategies in the trial cohorts and in new participants.

Method/design

Participants of the three previous cohorts and a new cohort will be subjected to 6 months bumetanide treatment using multiple baseline Single Case Experimental Designs. The primary outcome is the change, relative to baseline, in a set of patient reported outcome measures focused on direct and indirect effects of sensory processing difficulties. Secondary outcome measures include the conventional questionnaires ‘social responsiveness scale’, ‘repetitive behavior scale’, ‘sensory profile’ and ‘aberrant behavior scale’. Resting-state EEG measurements will be performed at several time-points including at Tmax after the first administration. Assessment of cognitive endpoints will be conducted using the novel Emma Tool box, an in-house designed battery of computerized tests to measure neurocognitive functions in children.

Discussion

This study aims to replicate previously shown effects of bumetanide in NDD subpopulations, validate a recently proposed treatment prediction effect methodology and refine endpoint measurements.

Trial registration

EudraCT: 2020–002196-35, registered 16 November 2020, https://www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu/ctr-search/trial/2020-002196-35/NL

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Neurodevelopmental disorders (NDDs) are heterogeneous conditions grouped by the DSM-5 as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism spectrum disorder (ASD), intellectual disability and learning disorders [1]. The more severe forms often require medicinal interventions but options are currently restricted to symptom suppressing medication. Whereas for ADHD multiple stimulant drugs are registered, for ASD no medication is registered to improve the core defining features but drugs are often prescribed to mitigate associated symptoms such as depression, hyperactivity and irritability.

The advent of genetic animal models of neurodevelopmental conditions has led to the identification of possible mechanism-based treatments, most notably for ASD. One of the most studied options is selective Na+-K+-2Cl− (NKCC1) antagonist bumetanide. Bumetanide is a registered loop diuretic that has been used for almost 50 years in adults and children with a variety of nephrological and cardiac conditions. Bumetanide has a mild side effect profile with diuretic effects such as electrolyte imbalance and hypokalemia that can be safely monitored when kidney function is normal [2, 3]. Blocking NKCC1 chloride import in the brain can lower chloride concentrations and potentially reinstate GABAergic inhibition. In normal development a developmental sequence occurs around birth, which is characterized by dramatic decrease in chloride concentration in neuronal cells. This maturational downregulation of chloride levels causes a shift in the so-called polarity of GABAergic transmission from excitatory (depolarizing) to inhibitory (hyperpolarizing): as referred to as the GABA-shift. The GABA shift is mediated predominantly by a change in the expression of two chloride co-transporters: the Na-K-2Cl cotransporter isoform 1 (NKCC1) importer and K-Cl cotransporter isoform 2 (KCC2) exporter [4, 5], hence the potential for bumetanide to restore inhibitory GABA signaling. Since GABAergic inhibition has an important role in maintaining E/I balance for proper neuronal growth, and synapse and circuit development, alterations in polarity may have wide-ranging consequences. Indeed, in model studies for ASD [6,7,8], epilepsy [9], Rett syndrome [10] and Down syndrome [11], the GABA shift was found to be abolished and excitatory effects of GABAergic signaling were established.

These findings lead to the initiation of bumetanide trials in ASD and several genetic disorders, with varying results [6,7,8]. This is in our opinion, in part the result of ignoring etiological heterogeneity of NDDs, which is likely to result in mechanism-based options not fulfilling a one-size-fits application (as opposed to symptom suppressing treatments). As such, we argue that these treatments will only be effective in a subset of patients with NDDs [2, 12]. Accordingly, we developed a set of trials testing different behavioral neurophysiological and genetic stratifications to evaluate efficacy across different diagnostic classes and to develop strategies for more successful application:

‘Bumetanide for autism medication and biomarker study’ (BAMBI), to replicate effectiveness in ASD on core symptomology and to develop electro-encephalogram (EEG) and cognitive stratification and prediction markers.

‘Bumetanide for the autism spectrum clinical effectiveness trial’ (BASCET), to test effectiveness in a cohort stratified by the presence of sensory reactivity problems across NDDs (ASD, ADHD, epilepsy).

‘Bumetanide for ameliorate tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) hyper-excitable behaviors’ (BATSCH)’, an open label trial in children stratified by a genetic disorder with previously suggested efficacy of bumetanide.

In these trials, we evaluated multiple outcome levels including: behavior, cognition and neurophysiological changes using questionnaires, neurocognitive testing and resting-state EEG and event-related (ERP) markers, see Tables 1 and 2. The resting-state EEG markers focused on measuring effects on excitation-inhibition (E/I) ratios in line with the putative effect of bumetanide on GABAergic transmission [13]. The main findings included: 1) A superior effect of bumetanide on repetitive behavior in ASD (BAMBI) and TSC (BATSCH) [14, 15], 2) A significant effect of bumetanide on aberrant behaviors across disorders (BASCET and BATSCH), and 3) Enhanced power and excitation-inhibition ratios [13] only in the bumetanide treated group in the BAMBI trial. From the EEG effects, we developed an initial prediction algorithm by incorporating EEG biomarkers and clinical severity scores (RBS-r) [16].

Another important observation was the consistent improvement of several symptoms not captured by the conventional outcome scales. For instance, symptoms such as fatigue, irritability, energy and sleeping problems seemed responsive to bumetanide. To evaluate these symptoms, we have recently developed a ‘patient reported outcome’ (PRO) set that we chose as the primary endpoint in this post cohort study to serve as a potential more personalized method of outcome measuring (van Andel under review).

Here we present the follow-up trial protocol developed to replicate previous bumetanide effects, improve clinical endpoint selection and to validate the treatment prediction algorithm.

Methods/design

The Bumetanide for developmental disorders (BUDDI) study is a post-trial access cohort using Single-Case Experimental Designs (SCEDs) testing bumetanide treatment during 6 months. This type of N-of-1 design is most appropriate for our post-trial access cohort as 1) N-of-1 designs involving placebo treatment periods may not be tolerated, as many participants have already participated in placebo-controlled experiments (i.e. BAMBI, BASCET) and 2) the washout data of BAMBI and BASCET trials suggested prolonged effects of bumetanide treatments, which cause difficulty in placebo versus treatment cross-over designs due to carry over effects. The study will be performed at the N=You neurodevelopmental Precision Center at the Emma Children’s Hospital in the Amsterdam University Medical Center (AUMC), the Netherlands. SCEDs are preferred over the conventional post-trial access design (open label), because of the goals of more individualized effect measurements and improvement of clinical end point selection.

Design

We will use multiple baseline SCEDs (MBD) in which the intervention (bumetanide) is introduced sequentially to different patients with a baseline period ranging from 2 to 12 weeks. The rationale for this multiple baseline is that apart from clinical and response heterogeneity across individuals also symptoms per patient vary over time. In an MBD the variation in the baseline period (A phase) is compared to the variation during the intervention (B phase) on an individual level (i.e. the participant serves as his/her own control). Evidence of such an AB designs is based on demonstrating that the change in behavior only occurs during intervention.

Study population

All participants that participated in the previous studies, as well as a new cohort with matching inclusion and exclusion criteria are eligible for this post-trial access study. See Table 3.

Recruitment and screening

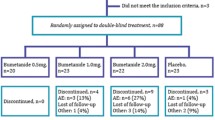

All previous participants of the BAMBI, BASCET and BATSCH trials will be contacted and informed about this post-trial access study. If interested and eligible, previous participants will receive verbal and written information about the study. We estimate that 50% of the patients that were enrolled in the three previous bumetanide trials will be eligible and motivated to be enrolled in the present study (i.e., 75 patients in total).

Participants of the new cohort will be recruited from the patient population referred to the N=You neurodevelopmental Precision Center at the Emma Children’s Hospital in the AUMC.

Intervention and preparation of study drugs

The intervention constitutes of bumetanide tablets. Bumetanide will be provided at a starting dose of 0.5 mg twice daily and will be increased to the therapeutic dosage of 1.0 mg twice daily at day 7 if there are no signs of dehydration in all participants. In case of limited effects and side-effects and a weight > 45 kg dosage can be increased to 1.5 twice daily. Dose reductions to manage side effects will be allowed at any time. Tablets will be obtained via the research pharmacy of AUMC. Re-labeling will be prepared and applied according to local regulatory requirements (GMP annex 13 guidelines). Participants are instructed to return unused tablets to allow monitoring of drug adherence.

Randomization

A randomization list of 115 baseline periods (2–12 weeks, with an equal distribution between the 11 intervals) is generated using the statistical program SPS. Upon signing informed consent, the participant receives the baseline period corresponding with the next open slot on the list.

Outcomes and measurements

Primary outcome

The primary outcome is a set of patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) containing questions directly or indirectly related to sensory processing difficulties, which will be filled in by caretakers. We chose this outcome over more conventional outcome measures for three reasons. 1) it allows for more personalized method of outcome measuring, 2) the PROMs are selected based on the symptoms not captured by conventional outcome scales (see background), 3) A prerequisite for the primary outcome of a SCED is the frequent and repeated measurement of the target behavior in every phase to address the variability in that behavior during the baseline and the intervention phase. The selected PROM-set asks the respondent to reflect upon the last 7 days, whereas conventional questionnaires often ask for reflection upon a longer time scale, making them less suitable for a SCED design.

The effects on PROMs will be compared to main conventional endpoints used in the original trials (social responsiveness scale, second edition (SRS-2) [17], repetitive behavior scale revised (RBS-r) [18], aberrant behavior scale (ABC) [19] and sensory profile – Dutch version (SP-NL) [20]) as well as accompanying measurements of EEG and neurocognition to further establish effects on brain activity and functioning and to validate predictive markers of treatment response. Individual results will be aggregated to evaluate bumetanide efficacy on a group level.

Secondary outcomes

The secondary outcome measures are divided over three domains: the behavioral, the functional and the translational domain (see Table 4).

Behavioral domain

The behavioral domain focuses on clinical outcomes and constitutes of four questionnaires to evaluate core symptomatology. The scales used are consistent with those used in the previous trials: The SRS-2, RBS-r, ABC and SP-NL.

In addition, these questionnaires will be used to validate how well the PROM set captures classically defined core symptomatology.

Functional domain

The functional domain contains neurocognitive and neurophysiological measures. We will use the Emma Tool box, an in-house designed battery of computerized tests, to measure neurocognitive functions in children. Measures will be obtained at 3 time points (baseline and after three and 6 months of treatment). Individual change in domain scores will be analyzed.

We will perform resting state electroencephalography (EEG) to assess neurophysiological functioning. EEG will be recorded by using the 128 channels Magstim/EGI system. EEG data will be processed offline using the Neurophysiological biomarker toolbox (http://www.nbtwiki.net/). Similar to our previous trials we selected five biomarker algorithms that have proven sensitive to the ratio of excitation and inhibition in computational models of neuronal networks generating alpha-band oscillations to quantify EEG. These biomarkers include: Relative and absolute power, central frequency, detrended fluctuation analysis and excitation/inhibition ratio. EEGs will be obtained at baseline, Tmax (1,5 h after first dose) and shall be repeated on a monthly basis.

Translational domain

The translational domain focusses on methods for future translation of (emerging) disease mechanisms and the development of more personalized therapies.

One entry point for personalized therapies are studies in animal models with causal genetic variants for NDDs. Hence, we will perform genetic testing via whole exome sequencing.

In addition, induced pluripotent stem-cell (iPSC) based model systems provide the opportunity to examine disease mechanisms in patient-own neurons and provide the opportunity to test personalized treatment options. Accordingly, we will perform assays with iPSC derived neuronal models.

Safety procedures

Safety will be assessed by the research team under supervision of a child psychiatrist and if necessary, a pediatric nephrologist. The assessment includes checks for the use of other medications, side effects and adverse events. In addition, physical examinations and blood and urine laboratory tests will be performed. See appendix 1 for a schematic overview of the examinations.

Oral potassium supplementation at a dose of 0.25 mmol/kg twice daily will be prescribed via custom pharmacy to all participants in order to avoid hypokalemia. Additionally, adjustments in the dosage of bumetanide are allowed to manage hypokalemia and/or side effects.

Statistics

Power calculations

Without using any kind of data simulation, we estimate that 50% of the patients that were enrolled in the three previous bumetanide randomized controlled trials (RCTs) will be eligible and motivated to be enrolled in the present study (i.e. 75 patients). To estimate sample size requirements and type I and II error magnitudes of a statistical test in a SCED design, the outcome measure that is assessed on the most frequent basis should be used, in our case the PROMs. Since this measure has not been included in the previous RCTs conducted in our patient cohort, we cannot rely on effect size estimates for this particular outcome. As such, due to availability we based the power computations on outcome measures used in the BAMBI study. Specifically, we established the minimal sample size required to detect a significant effect on the secondary BAMBI outcome, improvement on repetitive behavior scale, on which previously, a significant effect was observed.

For this purpose we used an online tool suitable for multiple baseline single case designs [21]. The tool tests a statistically significant effect using a non-parametric, randomization test (see Data Analysis) and the following inputs: effect size to be estimated, number of permutations, number of patients, number of outcome measurements.

In a randomization test, an effect estimate is obtained by drawing a large number of samples from a “randomization distribution”. To overcome the computational difficulties arising from drawing all the possible samples, using Monte Carlo sampling we approximate as accurately as possible the result we would get when drawing all samples. To ensure a compromise between accuracy and computational feasibility, our power simulation uses repeated draws, namely 5 Monte Carlo chains, each drawing 100 samples.

We tested whether, given the current experimental setup, we are able to detect an effect comparable in size to the one obtained in the BAMBI study. For RBS-r, the outcome variable previously shown to be significantly impacted, the effect size of the treatment was estimated to be d = 0.373 (80% C.I. 0.225–0.529), using Cohen’s d for dependent samples. The simulations showed that an effect size d = 0.4 can be detected with a relatively high power (0.71 when N = 40 and 0.73 when N = 50), in the absence of autocorrelation. In practice, measurements which are close in time are related, thus outcome scores at one time point can predict scores at another time point (autocorrelation or serial dependence). With larger sample sizes (N = 60), the power to detect the same effect remains fairly high (0.69) even in the presence of low-medium (r = 0.3) autocorrelation.

Thus, N = 40 is an acceptable minimum sample size to be able to detect the BAMBI effect in a no-autocorrelation scenario and N = 60, a minimum sample size in the presence of low-to-medium autocorrelation. As we intend to enroll a minimum of 75 patients from previous cohorts and a minimum of 40 patients in the new cohort, we expect to have sufficient power to detect a comparable treatment effect.

Data analysis

For the data analysis visual inspection of the data and statistical inference using (interrupted) time series analysis and randomization tests will be performed.

Visual inspection using 2SD-band method

First, the PROMs will be plotted as its own time-series for visual inspection using the 2-SD band method, as described in Hoogeboom et al. [22]. The 2-SD band will be calculated from the baseline data and graphed from the baseline through the intervention and post-intervention phase. If two or more successive data points in the intervention or post-intervention phase fall outside the 2 SDs bandwidth, the result will be considered significant on an individual basis. As autocorrelation can bias the visual inspection, we will check our data in each phase for serial dependence using the lag-1 method. If data are found to be significantly correlated, we will transform the data using a moving-average transformation.

Parametric methods: (interrupted) time series

Single subject measurements are graphed over time in a series based on which we can predict measurements at future time points for that subject.

Due to repeated measurements, the series may exhibit patterns such as autocorrelation, seasonality and trends not explained by the intervention (non-stationarity). Failing to account for said patterns can lead to erroneous effect predictions. Based on visual inspection of the series and residuals, special regression models “ARIMA” (AR auto-regressive, I integrated, MA moving-average) can be tailored to account for said patterns and get more accurate predictions. To obtain group effects, the single-case effect predictions will be aggregated using meta-analysis.

Given our study design we are interested in comparing the (predicted) outcome evolution based on the baseline measurements, to the (observed) evolution based on post- intervention measurements. To that aim we use interrupted time series analysis (ITSA), an extension of classical time series analysis [23].

Non-parametric methods: randomization tests

If the SCED involves a small number of participants, parametric assumptions of data normality and homogeneity of variance might not be met, in which case, tests which do not make parametric assumptions might be more suitable, i.e. Koehler and Levin’s randomization test [24].

The null hypothesis of the randomization test is that, for all possible permutations, the mean difference between baseline and intervention is the same.

Selection bias

There is a likelihood of (patient-induced) selection bias, as it is more likely that previous participants from the responder groups will participate in this post trial access study. Accordingly, there will probably be a larger group of responders than non- responders.

We propose two methods to address this: controlling for covariates associated with selection (modelling-based) and inverse probability weighting. In the first approach, we will include a covariate describing previous responder status and check for significance. The second approach involves computing the probability of selection for each responder category and assigning a weight to each subgroup inverse to the selection probability.

Minimal clinically important difference (MCID)

Another aspect we wish to address is what constitutes a (non)responder. To determine the MCID for our target outcome scales, we intend to use comparisons of care-taker assessments in parent-to-parent conversations (anchor-based method).

Development of new predictors

The newly developed prediction algorithm based on EEG and clinical features will be evaluated and further developed [16]. Analyses will be performed using both regression analyses and supervised machine learning.

Discussion

In conclusion, the BUDDI post trial access study will offer the opportunity to replicate individual and stratified group level effects of bumetanide, to improve clinical endpoint selection and to validate an EEG based treatment prediction algorithm. Forthcoming findings may enhance the applicability of bumetanide in heterogeneous NDD populations.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ABC:

-

Aberrant behavior scale

- ADHD:

-

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

- ASD:

-

Autism spectrum disorder

- BAMBI:

-

Bumetanide for autism medication and biomarker study

- BASCET:

-

Bumetanide for the autism spectrum clinical effectiveness trial

- BATSCH:

-

Bumetanide for ameliorate tuberous sclerosis complex hyper-excitable behavior

- BRIEF:

-

Behavior rating inventory of executive function

- BUDDI:

-

Bumetanide for developmental disorders

- EEG:

-

Electro-enchephalogram

- EQ-5D-5L:

-

5-level EuroQoL 5-dimensional questionnaire

- EQ-5D-Y:

-

5-level EuroQoL 5-dimensional questionnaire, youth version

- ERP:

-

Event-related potential

- HSP:

-

Highly sensitive child or parent scale

- iPCQ:

-

Productivity cost questionnaire

- iPSC:

-

Induced pluripotent stem cell

- KCC2:

-

K-Cl cotransporter isoform 2

- MBD:

-

Multiple baseline SCEDs

- MCID:

-

Minimal clinically important difference

- NDDs:

-

Neurodevelopmental disorders

- NKCC1:

-

Na-K-2Cl cotransporter isoform 1

- pedsQL:

-

Pediatric quality of life inventory

- PROM:

-

Patient reported outcome measure

- PROMIS:

-

Patient reported outcome measurement information system

- QoL:

-

Quality of life

- RBS-r:

-

Repetitive behavior scale revised

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

- rsEEG:

-

Resting state electro-encephalogram

- SCED:

-

Single-case experimental design

- SP-NL:

-

Sensory profile. Dutch version

- SP-SC:

-

Sensory profile, school companion

- SRS-2:

-

Social responsiveness scale, second edition

- TAND:

-

Tuberous sclerosis associated neuropsychiatric disorders

- TiC-P:

-

Trimbos/iMTA questionnaire for Costs associated with Psychiatric Illness

- TRF:

-

Teacher report form

- TSC:

-

Tuberous sclerosis complex

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). https://doi.org/ezproxy.frederick.edu/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.

Schulte JT, Wierenga CJ, Bruining H. Chloride transporters and GABA polarity in developmental, neurological and psychiatric conditions. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2018;90:260–71.

Kharod SC, Kang SK, Kadam SD. Off-label use of bumetanide for brain disorders: an overview. Front Neurosci. 2019;13:310.

Ben-Ari Y, Khalilov I, Kahle KT, Cherubini E. The GABA excitatory/inhibitory shift in brain maturation and neurological disorders. Neuroscientist. 2012;18(5):467–86.

Ben-Ari Y. Excitatory actions of gaba during development: the nature of the nurture. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3(9):728–39.

Lemonnier E, Degrez C, Phelep M, Tyzio R, Josse F, Grandgeorge M, et al. A randomised controlled trial of bumetanide in the treatment of autism in children. Transl Psychiatry. 2012;2:e202.

Lemonnier E, Villeneuve N, Sonie S, Serret S, Rosier A, Roue M, et al. Effects of bumetanide on neurobehavioral function in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Transl Psychiatry. 2017;7(3):e1056.

Zhang L, Huang CC, Dai Y, Luo Q, Ji Y, Wang K, et al. Symptom improvement in children with autism spectrum disorder following bumetanide administration is associated with decreased GABA/glutamate ratios. Transl Psychiatry. 2020;10(1):9.

Nardou R, Yamamoto S, Chazal G, Bhar A, Ferrand N, Dulac O, et al. Neuronal chloride accumulation and excitatory GABA underlie aggravation of neonatal epileptiform activities by phenobarbital. Brain. 2011;134(Pt 4):987–1002.

Marchetto MC, Carromeu C, Acab A, Yu D, Yeo GW, Mu Y, et al. A model for neural development and treatment of Rett syndrome using human induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell. 2010;143(4):527–39.

Deidda G, Parrini M, Naskar S, Bozarth IF, Contestabile A, Cancedda L. Reversing excitatory GABAAR signaling restores synaptic plasticity and memory in a mouse model of Down syndrome. Nat Med. 2015;21(4):318-26.

Bruining H, Passtoors L, Goriounova N, Jansen F, Hakvoort B, de Jonge M, et al. Paradoxical benzodiazepine response: a rationale for bumetanide in neurodevelopmental disorders? Pediatrics. 2015;136(2):e539–43.

Bruining H, Hardstone R, Juarez-Martinez EL, Sprengers J, Avramiea AE, Simpraga S, et al. Measurement of excitation-inhibition ratio in autism spectrum disorder using critical brain dynamics. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):9195.

van Andel DM, Sprengers JJ, Oranje B, Scheepers FE, Jansen FE, Bruining H. Effects of bumetanide on neurodevelopmental impairments in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex: an open-label pilot study. Mol Autism. 2020;11(1):30.

Sprengers JJ, van Andel DM, Zuithoff NPA, Keijzer-Veen MG, Schulp AJA, Scheepers FE, et al. Bumetanide for Core Symptoms of Autism Spectrum Disorder (BAMBI): A Single Center, Double-Blinded, Participant-Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Phase-2 Superiority Trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2021;60(7):865-876.

Juarez-Martinez EL, Sprengers JJ, Cristian G, Oranje B, van Andel DM, Avramiea AE, et al. Prediction of behavioral improvement through resting-state EEG and clinical severity in a randomized controlled trial testing bumetanide in autism spectrum disorder. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging. 2021;S2451-9022(21):00251–2.

Constantino J. Social responsiveness scale. 2nd ed; 2012.

Lam KS, Aman MG. The repetitive behavior scale-revised: independent validation in individuals with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2007;37(5):855–66.

Aman MG, Singh NN, Stewart AW, Field CJ. The aberrant behavior checklist: a behavior rating scale for the assessment of treatment effects. Am J Ment Defic. 1985;89(5):485–91.

Ermer J, Dunn W. The sensory profile: a discriminant analysis of children with and without disabilities. Am J Occup Ther. 1998;52(4):283–90.

Bouwmeester CJ. Single Case Designs. https://architecta.shinyapps.io/SingleCaseDesignsv02/ 2020.

Hoogeboom TJ, Kwakkenbos L, Rietveld L, den Broeder AA, de Bie RA, van den Ende CH. Feasibility and potential effectiveness of a non-pharmacological multidisciplinary care programme for persons with generalised osteoarthritis: a randomised, multiple-baseline single-case study. BMJ Open. 2012;2(4):e001161.

Jandoc R, Burden AM, Mamdani M, Levesque LE, Cadarette SM. Interrupted time series analysis in drug utilization research is increasing: systematic review and recommendations. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015;68(8):950–6.

Koehler MJ, Lehrer R. Designing a hypermedia tool for learning about children’s mathematical cognition. J Educ Comput Res. 1998;18(2):123–45.

Acknowledgements

not applicable.

Funding

This study is a continuation of the aforementioned bumetanide trials for which we previously received funding form ZonMW (Goed gebruik geneesmiddelen) and the Hersenstichting (Sooner better treatment program). In addition, we received funding from the Dutch national research agenda (in Dutch: nationale wetenschapsagenda, NWA-ORC) which will support the cost to develop the iPSC experiments. The funding bodies played no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GC and GJVDW were major contributors in writing the ‘statistics’ section of the manuscript, LG, JR, EH, MV and HB were major contributors in the ‘outcomes and measurements’ section and LG and HB were major contributors in writing the remaining sections of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the study protocol and read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

This study protocol has been reviewed and approved by the medical ethics committee of Utrecht, The Netherlands (‘Medisch ethische toetsingscommisie (METC) Utrecht’) (reference number NL73520.041.20) and has been registered at the Eudra CT database (EudraCT: 2020–002196-35). A protocol revision chronology and a trial registration data set are provided in appendices II and III respectively. Participants and their parents/guardians will receive verbal and written information about the study. Separate information sheets and consent forms are available for parents/guardians, children below the age of 12, children aged 12 to 16 and adolescents above the age of 16. The coordinating or principal investigator will obtain written informed consent from all participants before inclusion. Parents/guardians provide written informed consent for children below the age of 12. Children and adolescents above the age of 12 provide their own written informed consent, combined with written informed consent by the parent/guardian in case the participant is below the age of 16 years.

Monitoring will be conducted by the clinical research bureau (CRB) of the VUmc. The CRB is an independent party that monitors all WMO research at the VUmc. Study monitors will visit the study site at regular intervals to monitor the execution of the study. Monitors will have access to all documents that are needed to perform their task according to the ICH-GCP guidelines. Monitors will check whether requirements to conduct the study are met and study procedures are followed correctly, and will check the study site’s documentation, the participants’ source data, eCRF entries, and the correct maintenance of the Investigator Site File. Investigators will permit trial-related monitoring, audits, ERB reviews and regulatory inspections, providing direct access to source data and study documents.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

HB is shareholder of Aspect Neuroprofiles BV, which provides EEG-analysis services for clinical trials. All other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Schematic overview of assessments

Below a schematic overview of assessments and safety procedures can be found.

Baseline parameters include: physical examination, extended blood analysis and urine analysis.

Blood analysis includes: sodium, potassium, chloride, uric acid, urea, creatinine, glucose, estimated glomerular filtration rate and total protein; The extended blood analysis includes alanine transaminase, asparate transaminase, gamma-glutamyltransferase, alkaline phosphatase and whole blood count.

Urine analysis includes: osmolarity, sodium, potassium, chloride, calcium, protein, creatinine, uric acid, microalbuminuria.

Physical examination includes: general appearance, weight, height, sitting and standing blood pressure, pulse rate and inspection of the skin, mouth and pharynx.

Appendix 2

Protocol revision chronology

Protocol version: 5.

Protocol amendment number: 2.

Issue date: 16-04-2021.

Author(s): H. Bruining, C. Van der Wit, B. Stunnenberg, M. Konings, A. Bouts, J Ramautar, G. Cristian, L. Geertjens.

Revision chronology:

Date | Protocol version |

|---|---|

Protocol version 3, 20-08-2020 | Original protocol |

Protocol version 4, 29-01-2021 | Version 4, Amendment 01 Primary reason for amendment: implementation of standard potassium supplementation |

Protocol version 5, 16-04-2021 | Version 5: Amendment 02 Primary reason for amendment: Inclusion of a new cohort |

*only protocol versions approved by the medical ethical committee are included in the revision chronology | |

Appendix 3

Table 5

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Geertjens, L., Cristian, G., Haspels, E. et al. Single-case experimental designs for bumetanide across neurodevelopmental disorders: BUDDI protocol. BMC Psychiatry 22, 452 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-022-04033-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-022-04033-8