Abstract

Background

Distinct oral atypical antipsychotics have different effects on autonomic nervous system (ANS) activity. Among them, oral aripiprazole has been linked to dysfunction of the ANS in schizophrenia. Long-acting injectable aripiprazole is a major treatment option for schizophrenia, but the effect of the aripiprazole formulation on ANS activity remains unclear. In this study, we compared ANS activity between oral aripiprazole and aripiprazole once-monthly (AOM) in schizophrenia.

Methods

Of the 122 patients with schizophrenia who participated in this study, 72 received oral aripiprazole and 50 received AOM as monotherapy. We used power spectral analysis of heart rate variability to assess ANS activity.

Results

Patients who received oral aripiprazole showed significantly diminished sympathetic nervous activity compared with those who received AOM. Multiple regression analysis revealed that the aripiprazole formulation significantly influenced sympathetic nervous activity.

Conclusion

Compared with oral aripiprazole, AOM appears to have fewer adverse effects, such as sympathetic nervous dysfunction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

The mortality risk of patients with schizophrenia exceeds that of the general population by two to three times [1], and cardiovascular disease is a major cause of death [2]. Notably, a general association has been found between sudden cardiac death and diminished autonomic nervous system (ANS) activity as well as overall morbidity [3]. Patients with schizophrenia are known to exhibit lower ANS activity compared with general populations [4, 5] and antipsychotic medications can lead to exacerbation of ANS dysfunction [6,7,8]. In previous studies on schizophrenia, we reported the dose-dependent manner by which antipsychotic drugs significantly decrease ANS activity [8] as well as the dissimilar effects of different atypical antipsychotics on ANS activity, specifically that the quetiapine group showed significantly diminished sympathetic and parasympathetic activity compared with the risperidone and aripiprazole groups and significantly lower sympathetic activity relative to olanzapine [9].

Long-acting injectable (LAI) antipsychotics are a useful option for relapse prevention, especially when patients with schizophrenia are nonadherent to their prescribed medication [10,11,12,13,14]. A recent study reported that atypical LAI antipsychotics had the lowest risk of all-cause mortality compared with other types of antipsychotics [15]. In addition, patients receiving atypical LAI antipsychotics had the lowest incidence of cardiovascular death among patients with schizophrenia who were receiving typical LAI antipsychotics, oral typical antipsychotic, or oral atypical antipsychotics [15]. However, the mechanism associated with the advantage of LAI antipsychotics over oral antipsychotics in relation to cardiovascular deaths is still unclear. In particular, the effect of each atypical LAI antipsychotic on ANS activity remains to be investigated. Moreover, few studies have elucidated the differences in ANS activity between the LAI and oral formulations of the same antipsychotic.

We focused on aripiprazole because it is a representative drug for treating schizophrenia and has both oral and LAI formulations. Aripiprazole once-monthly (AOM) is a major LAI antipsychotic prescribed for schizophrenia. Aripiprazole, a second-generation antipsychotic with a high-affinity partial agonist of dopamine D2 receptors and serotonin 5-HT1A receptors and an antagonist of 5-HT2A receptors [16], is efficacious in both the short and long term [17], with a low incidence of side effects (e.g., weight gain and hyperprolactinemia) and metabolic adverse events, except for akathisia [18, 19]. However, even though AOM is a major option in the treatment of schizophrenia, its effects on ANS dysfunction compared with those of oral aripiprazole are unclear and warrant further research.

In this study, we investigated the effects of oral aripiprazole and AOM on ANS activity. We noninvasively evaluated ANS activity by assessing 5-min resting heart rate variability (HRV), which can reflect autonomic nervous imbalance, in line with our previously reported work on the effects of oral atypical antipsychotics on ANS activity and their pharmacogenetic effects on ANS activity in schizophrenia [9, 20, 21]. The reliability, validity, and practicability of HRV have been described [22]. Understanding differences in the effects of oral and LAI aripiprazole on ANS activities could help clinicians decide which formulation to use in patients with schizophrenia.

Methods

Participants

This study used a cross-sectional design in a consecutive sample of 122 Japanese patients with schizophrenia (10 inpatients, 112 outpatients; 51 men, 71 women; mean age ± standard deviation, 43.2 ± 13.5 years) who were treated at Fujisawa Hospital, Asahinooka Hospital, or Yokohama City University Hospital in Japan from June 2016 to August 2019. All patients had received oral aripiprazole as monotherapy or AOM as monotherapy for more than 3 months at the same dosage and without adjustment in the previous 3 months. Fifty-two patients in the oral aripiprazole group and 9 patients in the AOM group were those involved in our previous study [9, 23]. In addition, patients with schizophrenia receiving oral aripiprazole or AOM were newly recruited for the present study. Exclusion criteria were as follows: nonadherence to medication prescribed (evaluated using medical interviews); current or previous cardiovascular, respiratory, neurological, or endocrine illness; and current or previous substance abuse that could obscure diagnosis. Patients taking non-psychotropic medications such as antihypertensive drugs other than laxatives, which do not affect HRV, were excluded. Psychiatrists with sufficient clinical experience made the diagnosis of schizophrenia according to the criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition [24]. They also evaluated patients’ positive, negative, and general signs using a Japanese translation of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS; [25]) to determine symptom severity on the same day as an electrocardiogram (ECG) was recorded.

We collected participants’ clinical information from the medical records and calculated the doses of all psychotropic medications prescribed, including aripiprazole, anticholinergic, and benzodiazepine agents, using conversions to standard equivalents of chlorpromazine, biperiden, and diazepam [26].

This study was approved by respective ethics committees of Fujisawa Hospital, Asahinooka Hospital, and Yokohama City University Hospital and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all participants following a full explanation of the study.

R–R interval power spectral analysis

As described in detail in our previous studies [9, 20, 21, 27], we performed computer-assisted measurement of 5-min resting HRV to noninvasively evaluate ANS activity. Briefly, participants abstained from caffeine consumption and smoking from the time of waking up on the measurement day. All experimental sessions were held between 9 am and noon. After initially resting for at least 10 min, patients were seated for 5 min for the ECG.

In the HRV power spectral analysis, a series of sequential R–R intervals obtained from the 5-min ECG was decomposed via fast Fourier transform into a sum of sinusoidal functions of different amplitudes and frequencies [28]. As in our previous studies [21, 28], spectral power was quantified in the frequency domain by calculating the areas under the curve in the low frequency band (LF; 0.03–0.15 Hz), reflecting both sympathetic and parasympathetic nerve activity; the high-frequency band (HF; 0.15–0.40 Hz), reflecting mainly parasympathetic nerve activity; and the total power band (TP; 0.03–0.40 Hz), reflecting overall ANS activity.

Statistical analysis

We used Student’s t-test to examine differences in clinical characteristics (age, body mass index [BMI], disease duration, aripiprazole dose, anticholinergic agent dose, benzodiazepine agent dose, and PANSS score, and the LF, HF, and TP components of HRV). We used the chi-square test to examine the ratios of males to females, inpatients to outpatients, and smokers to non-smokers. The association of clinical factors with ANS activity was determined using multiple regression analysis, with the LF, HF, and TP components of HRV considered dependent variables, and age, sex, BMI, aripiprazole dose, anticholinergic dose, benzodiazepine dose, and aripiprazole formulation (oral or LAI) considered independent variables possibly affecting ANS activity [7, 29, 30]. After adjusting for these confounders, we examined the relationship between all HRV components and drug formulation. The regression coefficients and their 95% confidence intervals were also calculated. Because the data were skewed, the absolute values of the HRV spectral components were log-transformed before statistical analysis.

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS for Windows version 24 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY), with significance established at p < 0.05.

Results

Demographic and medication data of the participants

Table 1 shows demographic and medication data of the 72 patients receiving oral aripiprazole and the 50 patients receiving AOM (Table 1). There were no significant differences between the two groups in age, sex, duration of illness, BMI, and there were trend-level differences in aripiprazole dose, anticholinergic drug dose, and benzodiazepine dose (Table 1). There were no significant differences between the two groups in PANSS positive score (oral aripiprazole: 14.40 ± 3.51; AOM: 13.66 ± 3.58), PANSS negative score (oral aripiprazole: 19.49 ± 6.21; oral aripiprazole: 17:98 ± 6.07), or PANSS general psychopathology score (oral aripiprazole: 35.04 ± 9.68; AOM: 32.98 ± 9.50).

ANS activities between the oral aripiprazole and AOM groups

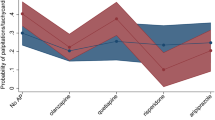

Table 2 shows no significant differences in the TP or HF components between the two groups, but the LF component was significantly lower in patients receiving oral aripiprazole (p = 0.033) (Table 2).

Association between ANS activities and clinical factors, including aripiprazole formulation

Table 3 shows the results of multiple regression analysis. Aripiprazole formulation was significantly associated with the LF component (p = 0.036), but not with the HF component or TP (Table 3). All of the HRV components were significantly associated with age. There were no associations of the spectral components of HRV with the other demographic and clinical factors.

Discussion

This study analyzed the differential effects of oral aripiprazole monotherapy and AOM monotherapy on ANS activity in patients with schizophrenia. Significant differences in HRV were evident between patients receiving oral aripiprazole and those receiving AOM, with lower LF component values seen with oral aripiprazole. These findings suggest that patients taking oral aripiprazole have diminished sympathetic nervous activity, given that the LF component indicates sympathetic and partially vagal modulation. In other words, we found that AOM was associated with less sympathetic nervous system dysfunction compared with oral aripiprazole. Indeed, in our previous small-scale preliminary study, LF component values were lower in patients receiving oral antipsychotics than in those receiving LAIs [23]. Here, with a larger sample size, we obtained the same results in patients treated with aripiprazole monotherapy.

In recent studies, treatment-emergent adverse events resulting in the discontinuation of treatment were found to be similar in type and incidence between AOM and oral aripiprazole, and the safety and tolerability data suggested that both were well tolerated [31, 32]. However, as pointed out by Xiao et al. [31], several studies of psychotropic drugs have demonstrated that the risk of extrapyramidal symptom-related adverse events was lower with LAI antipsychotics than with tablets, due to the stable blood concentrations of drugs with long-acting formulations. The concentration of oral aripiprazole tends to be higher compared with the LAI equivalent [33], and the steady-state peak-to-trough plasma concentration ratios of antipsychotics vary according to drug type, with LAI antipsychotics having lower peak-to-trough blood level variations compared with oral antipsychotics [34, 35]. In addition, the physiochemical properties of aripiprazole lauroxil, which is a LAI prodrug of aripiprazole, result in slow dissolution and an extended pharmacokinetic profile, which affords flexibility in dose and dosing interval [36]. A significant association has been reported and investigated between plasma concentration and an increased risk of adverse events [37,38,39]. Moreover, a reduction in the peak concentration can mitigate the risk of dose-dependent side effects, while an increase in the trough concentration can mitigate the incidence of lack of efficacy due to subtherapeutic drug concentration [40]. We have also reported that antipsychotic drugs affect ANS activity in a dose-dependent manner [8]. Taken together, these factors could explain the advantage of AOM over oral aripiprazole in terms of adverse effects, such as sympathetic nervous system dysfunction.

The estimated bioavailability of AOM has been reported to be almost 48% higher than that of oral aripiprazole [41]. LAI antipsychotics ensure better bioavailability and a more predictable correlation between drug dose and plasma concentrations, allowing lower doses to be prescribed and reducing the risk of side effects [42]. In fact, in previous studies, the incidence of akathisia [31] and neuroleptic malignant syndrome [43] tended to be lower in patients receiving AOM than in those receiving oral aripiprazole. Because no previous studies had compared ANS activity between AOM and oral aripiprazole, we focused on determining whether AOM was associated with less sympathetic nervous system dysfunction than oral aripiprazole in the present study.

Notably, the advantage of AOM over oral aripiprazole in terms of treatment continuation was recently reported in the real-world clinical setting in Japan [44]. Moreover, patients with schizophrenia who were receiving LAIs antipsychotics were found to have a lower risk of death than patients receiving oral antipsychotics [45] and, in one analysis, the lowest incidence of cardiovascular deaths (0.17 per 1000 patient-years) was seen with atypical LAI antipsychotics [15]. We previously reported that decreased ANS activity might be associated with all-cause mortality in patients with schizophrenia [27], so our current finding that AOM was not associated with diminished ANS activity compared with oral aripiprazole might be associated with improved clinical safety as well as improved mortality. We did not investigate the effects of the aripiprazole formulation on treatment discontinuation or the incidence of cardiovascular death in this study and would need to monitor patients over the long term to examine those outcomes.

In multiple regression analysis, a significant association was seen between the aripiprazole formulation and the LF component related to ANS activity. The same association was found for age. However, age was unlikely to have influenced our finding that the aripiprazole formulation had different effects on sympathetic nervous system activity because there were no significant differences in age between the groups (Table 1).

This study has some limitations. First, the cross-sectional design means that causal relationships cannot be determined. Second, ANS activity might have varied due to various factors (e.g., treatment history) before the patients were assigned to the two study groups. Third, the group receiving AOM was small because we did not control for size differences in the patient groups. Fourth, trend-level differences in aripiprazole dose, anticholinergic dose, and benzodiazepine dose between the two groups might have affected the results, although multiple regression analysis showed that the drug formulation was associated with the LF component of HRV after adjusting for other clinical factors. Further studies are needed as confounding factors or small sample size might have affected the results of this study. Fifth, we evaluated drug adherence in oral aripiprazole by means of medical interviews alone. Adherence in the oral aripiprazole group might have affected the comparison between oral aripiprazole and AOM. Sixth, comparison between healthy controls and AOM was not investigated in this study. Finally, we were unable to investigate the serum and brain concentrations of aripiprazole in this study, and thus we did not evaluate the effect of changes in concentrations according to the medication time and dosing frequency of the oral drugs.

Conclusion

In conclusion, AOM was associated with fewer side effects such as sympathetic nervous system dysfunction compared with oral aripiprazole. We need to monitor the course of patients with schizophrenia with diminished ANS activity who are taking aripiprazole, as well as compare the incidence of cardiovascular events more broadly, including cardiovascular deaths, between oral aripiprazole users and AOM users in a larger population. Studies of larger populations are also needed to further clarify the safety of AOM in relation to ANS activity in schizophrenia.

Data Availability

The datasets used and analyzed in this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ANS:

-

autonomic nervous system

- AOM:

-

aripiprazole once-monthly,

- BMI:

-

body mass index

- BPDeq:

-

biperiden equivalent

- CPZeq:

-

chlorpromazine equivalent

- DZPeq:

-

diazepam equivalent

- ECG:

-

electrocardiography

- EPS:

-

extrapyramidal symptoms

- HF:

-

high-frequency

- HRV:

-

heart rate variability

- LAI:

-

long-acting injectable

- LF:

-

low-frequency

- ln:

-

natural log-transformed

- PANSS:

-

Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale

- TP:

-

Total power

References

Walker ER, McGee RE, Druss BG. Mortality in mental disorders and global disease burden implications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(4):334–41.

Olfson M, Gerhard T, Huang C, Crystal S, Stroup TS. Premature mortality among adults with Schizophrenia in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;72(12):1172–81.

Thayer JF, Yamamoto SS, Brosschot JF. The relationship of autonomic imbalance, heart rate variability and cardiovascular disease risk factors. Int J Cardiol. 2010;141(2):122–31.

Clamor A, Lincoln TM, Thayer JF, Koenig J. Resting vagal activity in schizophrenia: meta-analysis of heart rate variability as a potential endophenotype. Br J Psychiatry. 2016;208(1):9–16.

Quintana DS, Westlye LT, Kaufmann T, Rustan OG, Brandt CL, Haatveit B, et al. Reduced heart rate variability in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder compared to healthy controls. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2016;133(1):44–52.

Birkhofer A, Geissendoerfer J, Alger P, Mueller A, Rentrop M, Strubel T, et al. The deceleration capacity – a new measure of heart rate variability evaluated in patients with schizophrenia and antipsychotic treatment. Eur Psychiatry. 2013;28(2):81–6.

Huang WL, Chang LR, Kuo TB, Lin YH, Chen YZ, Yang CC. Impact of antipsychotics and anticholinergics on autonomic modulation in patients with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2013;33(2):170–7.

Iwamoto Y, Kawanishi C, Kishida I, Furuno T, Fujibayashi M, Ishii C et al. Dose-dependent effect of antipsychotic drugs on autonomic nervous system activity in schizophrenia.BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12;199.

Hattori S, Kishida I, Suda A, Miyauchi M, Shiraishi Y, Fujibayashi M, et al. Effects of four atypical antipsychotics on autonomic nervous system activity in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2018;193:134–8.

Kishimoto T, Nitta M, Borenstein M, Kane JM, Correll CU. Long-acting injectable versus oral antipsychotics in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of mirror-image studies. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(10):957–65.

Kishimoto T, Robenzadeh A, Leucht C, Leucht S, Watanabe K, Mimura M, et al. Long-acting injectable vs oral antipsychotics for relapse prevention in schizophrenia: a metaanalysis of randomized trials. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40(1):192–213.

Leucht C, Heres S, Kane JM, Kissling W, Davis JM, Leucht S. Oral versus depot antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia – a critical systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised long-term trials. Schizophr Res. 2011;127(1–3):83–92.

Taipale H, Mehtälä J, Tanskanen A, Tiihonen J. Comparative effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs for rehospitalization in schizophrenia–a nationwide study with 20-year follow-up. Schizophr Bull. 2018;44(6):1381–7.

Tiihonen J, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Majak M, Mehtälä J, Hoti F, Jedenius E, et al. Real-world effectiveness of antipsychotic treatments in a nationwide cohort of 29 823 patients with schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(7):686–93.

Tang CH, Ramcharran D, Yang CW, Chang CC, Chuang PY, Qiu H, et al. A nationwide study of the risk of all-cause, sudden death, and cardiovascular mortality among antipsychotictreated patients with schizophrenia in Taiwan. Schizophr Res. 2021;237:9–19.

Burris KD, Molski TF, Xu C, Ryan E, Tottori K, Kikuchi T, et al. Aripiprazole, a novel antipsychotic, is a high-affinity partial agonist at human dopamine D2 receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;302:381–9.

Tien Y, Huang HP, Liao DL, Huang SC. Dose-response analysis of aripiprazole in patients with schizophrenia in Taiwan. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2022;12:20451253221113238.

Hirose T, Mamiya N, Yamada S, Taguchi M, Kameya T, Kikuchi T. The antipsychotic drug aripiprazole (ABILIFY). Folia Pharmacol Jpn. 2006;128(5):331–45. (Japanese).

Kane JM, Carson WH, Saha AR, McQuade RD, Ingenito GG, Zimbroff DL, et al. Efficacy and safety of Aripiprazole and Haloperidol versus Placebo in patients with Schizophrenia and Schizoaffective Disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(9):763–71.

Hattori S, Suda A, Kishida I, Miyauchi M, Shiraishi Y, Fujibayashi M, et al. Effects of ABCB1 gene polymorphisms on autonomic nervous system activity during atypical antipsychotic treatment in schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18(1):231.

Hattori S, Suda A, Miyauchi M, Shiraishi Y, Saeki T, Fukushima T, et al. The association of genetic polymorphisms in CYP1A2, UGT1A4, and ABCB1 with autonomic nervous system dysfunction in schizophrenia patients treated with olanzapine. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):72.

Moritani T, Kimura T, Hamada T, Nagai N. Electrophysiology and kinesiology for health and disease. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2005;15(3):240–55.

Suda A, Hattori S, Kishida I, Miyauchi M, Shiraishi Y, Fujibayashi M, et al. Effects of long-acting injectable antipsychotics versus oral antipsychotics on autonomic nervous system activity in schizophrenic patients. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2018;14:2361–6.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. fourth ed. Washington, DC: APA; 1994.

Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Ople LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13(2):261–76.

Inada T, Inagaki A. Psychotropic dose equivalence in Japan. Psychiatry Clin Neurosi. 2015;69(8):440–7.

Hattori S, Suda A, Kishida I, Miyauchi M, Shiraishi Y, Fujibayashi M, et al. Association between dysfunction of autonomic nervous system activity and mortality in schizophrenia. Compr Psychiatry. 2018;86:119–22.

Fujibayashi M, Matsumoto T, Kishida I, Kimura T, Ishii C, Ishii N, et al. Autonomic nervous system activity and psychiatric severity in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2009;63(4):538–45.

Chang HA, Chang CC, Tzeng NS, Kuo TB, Lu RB, Huang SY. Cardiac autonomic dysregulation in acute schizophrenia. Acta Nuropsychiatr. 2013;25(3):155–64.

Wang J, Liu YS, Zhu WX, Zhang FQ, Zhou ZH. Olanzapine-induced weight gain plays a key role in the potential cardiovascular risk: evidence from heart rate variability analysis. Sci Rep. 2014;4:7394.

Xiao L, Zhao Q, Li AN, Sun J, Wu B, Wang L, et al. Efficacy and safety of aripiprazole once-monthly versus oral aripiprazole in chinese patients with acute schizophrenia: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, non-inferiority study. Psychopharmacology. 2022 Jan;239(1):243–51.

Such P, Bøg M, Kabra MS, Jørgensen KT, de Jong-Laird AC. Share. A noninterventional cohort study assessing time to all-cause treatment discontinuation after initiation of Aripiprazole once monthly or daily oral atypical antipsychotic treatment in patients with recent-onset Schizophrenia. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2021;23(5):20m02886.

Korell J, Green B, Rae A, Remmerie B, Vermeulen A. Determination of plasma concentration reference ranges for oral aripiprazole, olanzapine, and quetiapine. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;74(5):593–9.

Sheehan JJ, Reilly KR, Fu DJ, Alphs L. Comparison of the peak-to-trough fluctuation in plasma concentration of long-acting injectable antipsychotics and their oral equivalents. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2012;9(7–8):17–23.

Iyo M, Tadokoro S, Kanahara N, Iyo M, Tadokoro S, Kanahara N, et al. Optimal extent of dopamine D2 receptor occupancy by antipsychotics for treatment of dopamine supersensitivity psychosis and late-onset psychosis. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2013;33(3):398–404.

Hard ML, Mills RJ, Sadler BM, Turncliff RZ, Citrome L. Aripiprazole Lauroxil: Pharmacokinetic Profile of this long-acting Injectable antipsychotic in persons with Schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2017;7(3):289–95.

Kakihara S, Yoshimura R, Shinkai K, Matsumoto C, Goto M, Kaji K, et al. Prediction of response to risperidone treatment with respect to plasma concentrations of risperidone, catecholamine metabolites, and polymorphism of cytochrome P450 2D6. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2005;20(2):71–8.

Yoshimura R, Ueda N, Nakamura J. Possible relationship between combined plasma concentrations of risperidone plus 9-hydroxyrisperidone and extrapyramidal symptoms. Neuropsychobiology. 2001;44(3):129–33.

Hart XM, Hiemke C, Eichentopf L, Lense XM, Clement HW, Conca A, et al. Therapeutic reference range for aripiprazole in schizophrenia revised: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Psychopharmacology. 2022;239(11):3377–91.

Wakamatsu A, Aoki K, Sakiyama Y, Ohnishi T, Sugita M. Predicting pharmacokinetic stability by multiple oral administration of atypical antipsychotics. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2013;10(3):23–30.

Wang X, Raoufinia A, Bihorel S, Passarell J, Mallikaarjun S, Phillips L. Population Pharmacokinetic modeling and exposure-response analysis for Aripiprazole once Monthly in subjects with Schizophrenia. Clin Pharmacol Drug Dev. 2022;11(2):150–64.

Graffino M, Montemagni C, Mingrone C, Rocca P. Long acting injectable antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia: a review of literature. (article in italian). Riv Psichiatr. 2014;49:115–23.

Misawa F, Okumura Y, Takeuchi Y, Fujii Y, Takeuchi H. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome associated with long-acting injectable versus oral second-generation antipsychotics: analyses based on a spontaneous reporting system database in Japan. Schizophr Res. 2021;231:42–6.

Iwata N, Inagaki A, Sano H, Niidome K, Kojima Y, Yamada S. Treatment persistence between long-acting injectable versus orally administered aripiprazole among patients with schizophrenia in a real-world clinical setting in Japan. Adv Ther. 2020;37(7):3324–36.

Taipale H, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Alexanderson K, Majak M, Mehtala J, Hoti F, et al. Antipsychotics and mortality in a nationwide cohort of 29,823 patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2018;197:274–80.

Acknowledgements

We thank all research participants for their support in this study.

Funding

This research received no specific funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SH was critically involved in the study design, analyzed and interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript. AS, IK, and AH supervised the entire project and were critically involved in the study design, data analysis, and interpretation. MM, YSh, NN, TFur, TA, CI, NI, TS, and Tadashi F were involved in participant recruitment. MF, NT, and TM were involved in analyzing the data, in particular, heart rate variability by means of power spectral analysis. YSa was involved in the statistical analyses. All authors contributed to and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Fujisawa Hospital, Asahinooka Hospital, and Yokohama City University Hospital, and the study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent after receiving detailed information regarding the study. All participants were deemed capable of ethically and medically consenting to their participation in the research by psychiatric experts.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Hattori, S., Suda, A., Kishida, I. et al. Differences in autonomic nervous system activity between long-acting injectable aripiprazole and oral aripiprazole in schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry 23, 135 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-04617-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-04617-y