Abstract

Background

Many countries have started pursuing tobacco ‘endgame’ goals of creating a ‘tobacco-free’ country by a certain date. Researchers have presented models to attain this goal, including shifting the supply of tobacco to a monopoly-oriented endgame model (MOEM), wherein a state-owned entity controls the supply and distribution of tobacco products. Although not designed to end tobacco use, the Regie in Lebanon exhibits some of the key features identified in MOEM and hence can serve as a practical example from which to draw lessons.

Methods

We comprehensively review previous literature exploring tobacco endgame proposals featuring a MOEM. We distil these propositions into core themes shared between them to guide a deductive analysis of the operations and actions of the Regie to investigate how it aligns (or does not) with the features of the MOEM.

Results

Analysing the endgame proposals featuring MOEM, we generated two main themes: the governance of the organisation; and its operational remit. In line with these themes, the investigation of the Regie led to several reflections on the endgame literature itself, including that it: (i) does not seem to fully appreciate the extent to which the MOEM could end up acting like Transnational Tobacco Companies (TTC); (ii) has only vaguely addressed the implications of political context; and (iii) does not address tobacco growing despite it being an important element of the supply chain.

Conclusion

The implementation of tobacco endgame strategies of any type is now closer than ever. Using the Regie as a practical example allows us to effectively revisit both the potential and the pitfalls of endgame strategies aiming to introduce some form of monopoly and requires a focus on: (i) establishing appropriate governance structures for the organisation; and (ii) adjusting the financial incentives to supress any motivation for the organisation to expand its tobacco market.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Eight countries (Australia, Canada, England, Finland, Ireland, Malaysia, New Zealand, and Scotland) have articulated specific endgame goals as part of their drive to become ‘tobacco-free’ [1,2,3,4,5]. Most of those countries intend to decrease tobacco use and reduce smoking prevalence to below 5% of their population by a predetermined date [2, 6]. While there is no consensus on how to reach these goals [4], scholars have suggested a wide range of possible models to achieve endgame strategies [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. Among the suggested proposals is the creation of monopoly oriented endgame models (MOEM). These feature organisations that have public health mandates to control one or more aspects of the tobacco supply chain, and which exhibit monopoly like features [8, 9, 11, 17,18,19,20,21]. Essentially, this means that production of, and trade in, tobacco products is undertaken in the public interest through a state-run entity.

These models remain largely theoretical as none have yet been applied in practice, so there are many uncertainties about their potential implications [1, 22], which therefore makes it difficult to evaluate them [6, 23, 24]. Consequently there is value in comparing the proposed MOEM to an existing context [3] to be able to assess their potential applicability in real-world settings and accordingly draw lessons for advancing endgame strategies.

While certainly not the same, there are a few state-owned tobacco monopolies (SOTM) that do exist in various markets, which are similar in a number of ways to MOEM because of the monopoly characteristic. The market dynamics between the two organisational structures will be different (especially in regard to tobacco control policies) given that the monopolies exist for different reasons, but their nature as monopolies nevertheless offers a potentially useful point of comparison. As such, it should also be noted that there are a number of other state-owned (or part state-owned) tobacco firms that have less than 100% of the market (see [22, 25]). However, the oligopolistic nature of such firms suggests that the associated market dynamics will be further removed from those of an MOEM and hence they are not the focus of the study herein.

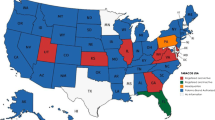

Lebanon, despite the on-going economic crisis, is an upper middle-income country (UMC) [26], and is one of the few countries with an operating SOTM, the Regie Libanaise de Tabacs et Tombacs, or the Regie, as it is commonly called. In this paper we will explore the Regie, as an exemplar SOTM. Within Lebanon, the tobacco market is controlled by the Regie, which is a commercial public institution [27, 28] with exclusive rights to undertake: domestic leaf purchasing of locally grown tobacco; manufacturing and distribution of tobacco products in Lebanon, including export/import activities [29]; and overseeing an anti-smuggling unit [30] (See Fig. 1 for a visual overview of the Regie).

While endgame strategies seem far from the agenda of the Lebanese Government [2], as the Regie is not designed to reduce tobacco use but rather to derive revenue for the government from its manufacture/sale, it exhibits a significant number of the key features that have been identified in MOEM. Thus, the Regie can serve as a practical case to explore some of the opportunities and challenges one could expect if an MOEM was to be adopted.

This paper therefore aims to investigate the extent to which the Regie, as a SOTM, aligns (or does not) with ideas around suggested MOEM. We map the features of the suggested theoretical endgame proposed models featuring MOEM into core themes shared between them. This then guides an exploration of the Regie’s structure, operations, and action relative to these themes in order to draw lessons from the Regie for advancing endgame strategies in a real-world setting and in doing so, also consider lessons for advancing tobacco control in Lebanon. Furthermore, this paper also contributes to the existing literature on state-owned tobacco monopolies, given we are the first to investigate the Regie or any state-owned tobacco monopoly in the context of tobacco endgame strategies.

Methods

To identify endgame literature suggesting MOEM, firstly, we began by reviewing the special issue of Tobacco Control on endgame strategies published in May 2013 [7] and drew on a paper by McDaniel et al. [6], containing a comprehensive list of all endgame proposals up to 2016. Secondly, for possible proposals published from 2016, we searched the PubMed database and Google Scholar using the terms ‘(tobacco AND endgame)’ AND (Monopol* OR state-own* OR state-run* OR state-govern*) and then conducted a ‘snowball’ search to find further relevant articles from those previously identified. The result of the search yielded a total of 38 papers after duplicates were removed. We excluded all endgame proposals that did not propose utilising an MOEM responsible for manufacturing and/or marketing and/or retailing. Overall, we identified a total of 7 proposals [8, 9, 11, 17, 18, 20, 21] that suggest a role for state-owned models of tobacco supply as part of an endgame strategy (Table 1).

Our study did not aim to undertake an in-depth analysis of the endgame proposals or to evaluate them, as other papers in the literature have done so [1,2,3, 6, 10, 15, 32,33,34,35,36,37]. Instead, we aimed to map the different features of the proposals to understand how the authors are proposing to integrate MOEM to advance endgame strategies. We therefore adopted a qualitative thematic analysis using a codebook approach [38, 39] which consists of systemically analysing the endgame proposals to provide a framework for analysing the Regie. Accordingly, we identified two main themes and nine subthemes from the endgame proposals. The generated themes were used deductively to conduct a document analysis (a systematic way to examine and synthetise data collected from documents [40]) to analyse the Regie and investigate how it aligns (or does not) with the features identified as being required for advancing the tobacco endgame. All three authors were involved in the exploration of the endgame literature and coding around them. These codes were discussed, refined, debated, and agreed by all three authors who collectively generated the final themes and sub-themes.

The first author collected and reviewed the wider literature on the Regie and undertook the primary data collection, which was then discussed extensively with the other two authors. The primary data on the Regie was collected by searching its website (https://www.rltt.com.lb). Given the nature and the source of these documents, they were triangulated [41] whenever possible with other document sources such as multiple government departments’ documents and websites [29, 42], the Global Tobacco Industry Interference Index (GTIII) 2020 [43], existing academic literature covering the Regie and/or tobacco control in Lebanon [27, 28, 31, 44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54], and mainstream Lebanese newspapers and online news platforms (such as The Daily Star, Al Akhbar, An Nahar, Al Modon, Al Janoubia). To locate news articles addressing the Regie, a search of the website of those newspapers/online news platforms was conducted via a Google search in both Arabic and English using the Regie as a key word. Inclusion criteria consisted of any articles addressing the two identified themes. The earliest media article identified, extracted, and found to be relevant date back to 2007 and the search extended until early September 2021 [55].

Results

Of the seven identified proposals to suggest the use of an MOEM, the majority [8, 11, 17, 18, 20, 21] suggested regulating the tobacco industry while only one proposal [9] aimed to take over the tobacco industry. In the following sections, we offer an overarching synthesis of the main features suggested by the endgame proposals by theme and then sub-theme. We then compare each theme to data from documents identified on the operation of the Regie to critically analyse the extent to which the Regie’s features align with the relevant ideas around MOEM.

Governance structure

Our analysis consisted of identifying data from the seven proposed endgame proposals with respect to the first theme, governance structure, which we summarise in Table 2 according to the sub-themes of: ownership and control, reporting, and financing. The findings from Table 2 will be referred to in each of the next three sections when comparing the governance of the Regie to the endgames proposals.

Ownership and control

The endgame literature suggests that the proposed MOEM should be under the ownership of the government. The board of directors should contain ‘expert members’ to remain distant from government and political interference, thereby ensuring independence. It did not address how board members or staff are appointed to ensure independence, but it was mentioned [8] there is a need to account for staff integrity. The endgame literature also proposed that the decisions of the MOEM and the TTC need to be monitored by an independent body.

Comparing the Regie to those features, the Regie is owned by the Lebanese government and under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Finance (MOF) [30] which oversees its technical, economic, and financial management. By law [29, 56] the Regie is supervised by an appointed government commissioner and subject to financial audit by the MOF. The government commissioner is the communication liaison between the Regie and different governmental institutions. The Regie is only supposed to directly interact with the MOF twice per year regarding its financial budget [29]. Technically, this means the Regie is expected to maintain distance from the executive government and avoid political interference, an aspect that is broadly in line with the endgame ideas.

In practice, however, this is not the case. Firstly, the board is not as independent as it is supposed to be given the Lebanese political system is based on sectarianism that balances power between the different religions/sects that exist [28, 31, 57]. Hence, within this system, the Regie is under the patronage of the head of the parliament [28] where the general manager, in place since 1993 and appointed as chairman of the administration committee since 2002, is affiliated to the political party of the head of parliament. In addition, since 2016, the MOF has been run by to the same political party [58]. Furthermore, within this sectarian system almost half of all Regie employees are not hired based on merit but simply on the nature of their affiliation, leading to a clientelism relationship (i.e. creating a system of favours and associated loyalty) [28, 31, 59, 60]. Secondly, there are no mechanisms in place to control and hold the Regie and TTC accountable for their actions [61]. Hence holding its employees accountable is difficult as well [62]. Lebanon, a signatory of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) (an international treaty which aims to protect people from the harm of tobacco at social, environmental, economic, and health levels) [63] since 2005 [64], is expected to have its National Tobacco Control Programme (NTCP) [65] within the Ministry of Public Health to monitor and evaluate tobacco industry work (including the Regie) in line with the provisions of Article 5.3 of the FCTC [66] (Guideline 8 in Article 5.3 recommends that SOTM should be treated the same as the tobacco industry [67]). However, since at least early in 2019 and likely considerably earlier, the NTCP is practically inactive, claiming a lack of funds [64]. Furthermore, according to the law, the state commissioner has the right to monitor the Regie’s work and decisions, and even summon and interrogate high-ranking employees. However, if/how they actually monitor the Regie is not clear, with significant corruption and bribery having been reported at the Regie [59]. Indeed, both the state commissioner and the financial auditor’s salaries are paid by the Regie [68], which raises questions with respect to independence.

In the absence of independence, and with close link to a political party, the Regie is not distant from political interference. The GTIII 2020 ranked Lebanon as the fourth worst country on the overall country ranking (with the score deteriorating 1 point from the 2019 report). It scored poorly for: governmental institution and/or officials’ interaction with the tobacco industry (including the Regie) [43]. To illustrate, in 2011 Lebanon passed its first comprehensive tobacco control law [42], which includes imposing regulatory measures on the tobacco industry, and hence the Regie. The tobacco control laws in Lebanon (like other laws) need to be signed-off by more than one ministry, giving each a power of veto. Any tobacco control measures that restrict the operations of the Regie will likely damage its profitability, and hence (negatively) influence the decision of the MOF [53]. See for example, the same for pictorial warning as discussed in the product design section below.

Reporting mechanism

The endgame literature suggests that the proposed MOEM should make its information (meetings, discussions, decisions related to addressing health outcomes, licensing arrangements, price changes, etc.) publicly available through different platforms, as well as/or report to an independent overseeing body to ensure transparency.

Comparing the Regie to the endgame models’ suggestions, the Regie does report on its activities, but in a very similar way to a TTC, who typically produce yearly annual reports and publish on their websites that give an overview of select activities (but with few substantive details). While the Regie does not produce such an annual report, it does have a website (https://www.rltt.com.lb/), which includes similar information. One notable difference is that the website also includes information about the brand-level retail prices set for all shops in Lebanon, which are updated on a regular basis in line with the set market price. However, it seems that the published information on price is more about controlling the market rather than about transparency in its activities, as wholesalers and retailers are required to sell at the recommended retail price. A requirement not always followed (see below section on wholesalers).

Crucially though, the Regie’s financial disclosures are weak. It does not publish information on: the costs of manufacturing local brands; the cost of packaging; the salaries of its employees [46]; the special deals it gets on the price of imported tobacco products from the TTC (thought to be a lower price than other countries in the region) but kept secret at the request of the TTC [54]; the profit margins it earns on tobacco sales of domestic brands; or the profits made on the domestic production of international brands.

Financing

The endgame literature suggests the MOEM should or can be a non-profit institution and proposes how the MOEM could be financed. The different proposals raise concerns with respect to the MOEM’s financial interest in the sale of tobacco that could lead to corruption and/or dependence on revenues. Hence, they propose mechanisms on how to address potential dependence of governments on tobacco revenues.

Unlike the suggested endgame proposals, the Regie is a profit seeking organisation with ‘net profits, losses, and expenses’ directly linked to the public treasury [49]. It aims to expand the Lebanese tobacco market, thus its revenues and profits [30, 69, 70]. As per its general manager/chairman, their aim is to “win (a) place among internationally sustainable pioneer tobacco companies” [71, 72]. Part of the government tax revenue collected from imported tobacco products is used to cover the government Price Support Program (PSP) where the Regie purchases tobacco leaf from tobacco farmers at a given yearly price and specified quantity set by the MOF [49].

As stated above, the endgame proposals raise concerns with respect to financial interests, and an examination of the Regie confirms the need to be concerned. In 2019, the MOF praised the Regie for its 34% revenue increase relative to 2018 [73]. A news article pointed to the occurrence of high levels of corruption within the Regie [74] and another reported bribery of the financial audit of the Regie by the MOF to cover-up the illegal activities of the Regie [59]. Furthermore, a 2009 article reported that the Regie was, as of 2009 (no current data as to whether this procedure still in place), consulting retired employees who received compensation of up to LBP7 million per month per person (then US$4600 as this paper did not account for the financial crisis that Lebanon is currently experiencing since October 2019; all prices are based on the fixed exchange rate pre-October 2019, of LBP1507.5/US$1). The article added that one of those consultants, a former senior employee, was arrested at the behest of the Regie for vested interest related matters.

Also of concern are the financial interests of some of the political elites given their vested interest in the tobacco industry [75,77,78,78]. The TTC bypass the Regie by directly lobbying politicians with respect to tobacco laws [51]. Indeed some member of parliament (MPs) are in close connection with tobacco traders [75], have a stake in the main hospitality sectors in Lebanon and therefore they have an interest in amending the tobacco control law for their financial gain [79, 80]. Hence, some MPs have suggested amending tobacco control legislation to be more lenient on the hospitality sector that offer waterpipe indoors, claiming that the tobacco control law is negatively affecting tourism-related revenue. Similarly, a tobacco advocate reported that MPs have vested interests in preventing tax increase, which could explain why attempts over six years to raise tobacco taxation have always been blocked by self-serving MPs [51, 75].

In addition, the “citizen budget” [81], a publicly available report prepared by the MOF, includes data on the ‘total tax revenue’ from the Regie. By comparing the information on the Regie website in 2020 (net profit LBP268bn) and the data from the citizen budget report (Regie profits of LBP200.2bn) [73], the numbers do not match. A discrepancy that is not reported by or explained in the financial audit of the Regie by the MOF.

The political context is also a barrier towards regulating the Regie’s finances. Back in 1991, a committee to operate the Regie was established within it, without any legal standing or clear job description and on a temporary basis, but it is still in operation today without clear benefit for the Regie administration. A former Minister of Finance reported that it has been costing the state around LBP1bn (US$666.6 million) per year [82]. Despite his request and subsequent requests by other Ministers of Finance to abolish it, the Prime Minister in office has declined under the pretext of having to preserve the political balance sharing system within the public administration [82].

The supply chain operational remit

We also analysed data from the seven endgame proposals with respect to the second theme, operational remit, which are outlined in Table 3 according to the sub-themes of: product design; purchase; promotion; distribution and retailing; and final consumption. The identified data in Table 3 will be referred to in each of the next three section to analyse the Regie’s operation within the supply chain in comparison with the endgames proposals.

Product design

The endgame literature highlights the importance of introducing an MOEM that controls product design to develop less harmful and less addictive products as part of a public health mandate.

The Regie has no strong incentive to implement product design measures that would reduce tobacco-related harm where they generate profits. However, the Regie was successful in lobbying the Minister of Finance to override a decree issued by him in 2013 (while the Minister of Public Health) that banned e-cigarettes and heated tobacco products, and issue a new decree in 2015 that regulates their sale. In 2019, Lebanon moved from a country that banned e-cigarettes and heated tobacco product to a country that sells them in its market [43].

The Regie along with the TTC were successful in advocating the MOF to delay the implementation of textual health-warnings in 2013 [51, 83] and consistently lobbied the MOF to avoid signing the decree for pictorial warnings [84], even though a study conducted among Lebanese youth revealed the perceived effectiveness of pictorial in addressing the health and the negative economic consequences of smoking [52].

Importation/production

The endgame literature suggests that having an MOEM as the sole purchaser of tobacco products from the tobacco industry would allow it to regulate the manufacturers. In addition, the MOEM would be able to prevent the growth of the tobacco market and regulate tobacco prices. The endgame literature does not suggest a means to regulate tobacco growing as part of the tobacco trade. Only Callard et al. [9] mention it at all, and seem to assume it will eventually vanish with the decrease in tobacco consumption.

The Regie is the sole entity in Lebanon able to purchase from and negotiate trade agreements with TTC. Lebanon is one among five countries in the world that devotes more than 1% (3.2%) of its agricultural territory to tobacco farming [46]. The Regie has created an exchange deal with TTC to safeguard the local tobacco leaf growing industry. TTC buy local tobacco leaf and in return the Regie imports manufactured tobacco products to sell in the Lebanese market, buys the Virginia tobacco leaf to manufacture domestic brand cigarettes [49], and in the past few years, locally manufactures some international brands (discussed below).

Internal industry documents indicate that the TTC have used the Lebanese market in the past as an entry point for legally and illegally exporting tobacco products into neighbouring countries, taking advantage of the Lebanese government’s unwillingness or inability to control smuggling in the absence of adequate policies [44, 55]. By the first quarter of 2019, an Oxford Economics report put the illicit tobacco trade in the Lebanese market at 28.1% [85]. However, it is worth noting that this data has been subject to criticism given that the report was funded by the tobacco industry [86], and it has been reported that the TTC consistently over-inflate estimates of illicit trade [87].

The Regie has trade agreement with the TTC but furthermore, it acts towards facilitating their work in Lebanon. To illustrate, in the past few years, the TTC faced complications in the Lebanese market [88] as the sale of the domestic brand Cedars overtook foreign brands [89]. Starting from an agreement with PMI in 2017 [90], and built-on with later agreements with JTI (2018) [91] and BAT (2019) [92], the Regie began to locally produce international brands for domestic consumption and potentially export to neighbouring countries. The suggested reasons for these agreements are to reduce the “deficit in the balance of external payments”, hence alleviate the cost of shipping and customs fees [92, 93], and provide job opportunities for local businesses involved is secondary processing [92]. This change lowered the retail prices for the foreign brands [54] in the Lebanese market and, hence, increased their affordability. By making tobacco products more affordable, the Regie is, in effect, obstructing tobacco control measures.

Promotion

The endgame literature highlights the importance of regulating product promotion. This was mainly related to the power of the MOEM to decide on product design, and what needs to be communicated about the products by the retailers and wholesalers. Borland’s [8] proposal for an MOEM is to takeover the market entirely, which would eliminate any potential commercial incentive.

Turning to Lebanon, direct promotion of tobacco products, via advertising (such as written and audio-visual media) [94, 95] is less prominent [53]. What is problematic is indirect promotion and sponsorship such as CSR activities [94] by both the Regie and the TTC. The Regie has no marketing department but, in 2016, the Regie launched its Sustainable Development plan: "Development Vision for a Brighter Tomorrow”. Since then, it has been conducting CSR activities in line with its set priorities [96]. It has been undertaking activities such as running sports events [43, 97], sponsoring awareness activities around illegal recreational drugs, and financially supporting municipalities while promoting these CSR activities as a means to improve the life of their communities [98]. The Regie even publicly donated a total of US$2.6 million to the Lebanese Army in 2013 and 2021 [99,101,101], and donated US$1 millionM to the government to help address the COVID-19 crisis, which in both cases directly violated the provisions of Article 5.3 of the FCTC [102]. The TTC are likewise involved in indirect advertising in Lebanon. They provide convenience stores with LED illuminated tobacco stands and store branding [47], and are involved in sponsorship activities in co-ordination with the Regie [103]. They also promote their products by distributing free samples and accessories [53, 104], though the involvement of the Regie in this is currently unclear.

Distribution and retailing

The endgame literature suggests having an MOEM that could regulate wholesale distribution and/or retailing, either partially or fully, or even takeover their work in the supply chain. It is also clearly mindful that industry could work toward creating fake shortages and manipulate the price of products in the market. The endgame literature suggests that MOEM could regulate sales in retail stores by controlling store density, location, and selling hours, as well as suggests means to control retailers via anti monopolies laws and support them to transition away from selling tobacco or involve them in cessation programmes.

The Regie plays the role in between the TTC and wholesale distributors, and supplies domestic brands to wholesalers. There are around 800 licensed wholesalers [105] that, in theory, are effectively controlled by the Regie, which has the right to suspend their licenses [106]. The retailers, although licensed by the Regie, are not directly controlled by it, and communication with them is through the wholesalers which makes the retailers largely dependent on the wholesalers for their tobacco supply. Tobacco products are sold in almost every type of shop (including big supermarket, convenience, and grocery shops) [107], and there is no store density control or control over selling hours, unlike in the models proposed in the endgame literature.

However, the Regie does have authority over retail prices, the weekly tobacco supply quota (to control the market), and sets the profit margins for both wholesalers and retailers [49, 89, 108]. In practice this control is quite limited as consumers have complained about retail price manipulation, and the Regie has stated that it is the role of the consumer protection unit within the Ministry of Economy and Trade to monitor the tobacco product price in the market and not the Regie.

The wholesalers seem to have formed a cartel, which controls most of the licenses, including those of other distributors who sign-over the control of the licence through a secret legal agreement. The large ones effectively control the wholesale market [109] and these have direct links with TTC [54, 109] where they can agree to create artificial shortages to increase their profit [109] or promote a particular brand over another, an action that at least one senior Regie employee confirmed being aware of [110]. Furthermore, they have the power to manipulate the retail price. In 2017 a tax increase on tobacco products was discussed by the government, and before any official decision was taken, the wholesalers increased their price for retailers without consulting with the Regie. It took the Regie four days to act (i.e., to increase its price to wholesalers). This delay by the Regie was suggested to have cost the Regie, and hence the Government treasury, LBP1.5bn (US$1million), which was instead captured by the wholesale distributors. It is not clear if the Regie lacks procedures and plans to deal with these wholesalers, or if it is simply disinclined to act due to corruption [109] or to at least safeguard the close relationships between politicians and distributors [54]. To our knowledge, the Regie had never suspended a license to a distributor until August 2021 when the COVID-19 pandemic and economic collapse changed the picture significantly [111]. In the absence of any sanctioning measures by the Regie, when price manipulation occurs, or a fake shortage is created, the retailers have to abide by the wholesalers’ decisions.

Nonetheless, some retailers also take advantage of retail price manipulation by charging prices above those set by the Regie to compensate for their low margin of profit (also set by the Regie). Through informal conversations with retailers, it was reported that illicit tobacco products were being sold alongside licit products. However, the illicit product is mainly sold outside Beirut, where there are fewer customs police.

The Regie, if it wants, and in line with the endgame literature on MOEM, can play a more regulator type of role towards controlling the wholesaler-retailer component of the supply chain. In 2021 during the COVID-19 lockdown, it took a one-time decision, that was described as an 'unprecedented measure', to bypass the wholesale distributors and to directly provide the retailers with tobacco products. The decision was perceived as an action to curb the monopolisation of the market by the wholesale distributors [112].

Final consumption

The endgame literature is supply-side oriented, although protecting consumers from the harm of tobacco is their ultimate target. The proposals suggest that the MOEM should adopt an incremental approach to shifting consumers towards alternative products that are less addictive in order to avoid the further development of a black market and an increase in smuggling. In addition, they raise concerns that countries with relatively permeable borders could face smuggling if they implemented an MOEM [8, 11].

Contrary to the endgame proposals, the Regie’s approach to ‘increase consumer satisfaction’ is to make tobacco products available and affordable in the Lebanese market. The aim of the Regie is far from shifting consumers from the harm of smoking (although it has advocated for the introduction of e-cigarettes in the Lebanese market). In its sustainability report of 2016, preventing youth smoking is only the 8th out of 15 of its sustainability drivers. Preceding it are, in order: ‘combating illicit trade; sustainable agriculture; fighting child labour, consistency of product, development of employees’ skills reduce of energy consumption, consumer satisfaction’. Furthermore, it was in fact removed from the 2017 report which only featured 14 sustainability drivers [96, 113].

Unsurprisingly, Lebanon has some of the highest global rates of tobacco use compared to other middle-income countries [114] and, according to some studies, these are only increasing. For example, in September 2019 it was reported that 34% of men, and 21.2% of women are daily cigarette smokers, and 26.5% and 24.3% are respectively, daily waterpipe smokers [114]. A different study in May 2020 suggested 48.6% of adult men and 21.5% of adult women are cigarette smokers [53]. These high rates of tobacco use are associated with an annual cost of smoking to the Lebanese population of approximately US$326.7 million, equivalent to 1.1% of Lebanese GDP [49].

Discussion

Our paper identified seven endgame proposals featuring MOEM which were mapped against two main themes of structural governance and operational remit. Our findings identified that the endgame proposals underlined the importance of a congruous governance structure for the suggested MOEM as well as the significance of regulating the different segments of the supply chain to address the TTC influence on the supply side. The analysis of the Regie relative to those proposals revealed that the endgame literature did not fully appreciate the extent to which any MOEM could end up acting similar to a TTC. This is a danger emphasised in Article 5.3 of the FCTC, which calls for SOTM to be treated as the tobacco industry. Indeed, the analysis showed how the Regie acts like a TTC in many ways, affecting both its governance and operational remit. Moreover, the endgame literature has only vaguely addressed the implications of political context when establishing an MOEM [8, 11, 21, 115]. The case of the Regie has demonstrated how the MOF and other political elites have been actively involved in obstructing tobacco control measures, and hence that the endgame literature ignores a much-needed requirement for strong political leadership.

Thus, the first pre-condition for the MOEM to be a success, and for Lebanon to advance tobacco control, is to have strong political leadership and support that could enhance the context for policy change [115]. The second pre-condition for the MOEM is to address how to regulate tobacco growing, as farming is currently neglected by the endgame literature although it is it is an important element of the supply chain and could be part of the supply chain for several countries that would eventually adopt MOEM.

In the following discussion we draw out lessons for both MOEM and for Lebanon. Although certain elements of the Regie are context specific, it still holds some valuable lessons for a proposed MOEM.

Lessons learnt for MOEM

Overall, the endgame proposals highlight the crucial significance of having an MOEM with a public health mandate, and preferably also a not-for-profit one too. The case of the Regie illustrates how difficult it would be for an already existing SOTM to adopt a public health mandate given its profit-making objective [22, 116,118,119,119]. The financial issues caused by the COVID-19 pandemic for governments around the world will only have increased the difficulty of shifting to a non-profit making model [120].

Hence, focusing on public health and dropping profit might seem more wishful than practical at this stage. Consequently, to ensure a more plausible approach, endgame proposals need to ensure two specific elements/goals are accounted for when considering an MOEM: an appropriate governance structure and a carefully designed system of financial incentives.

Ensure an appropriate Governance structure

In their narratives, the proposals require the MOEM to be independent from political interference and impose regulatory measures to control the operation of the supply chain and the work of the different stakeholders (manufacturers, distributors, and retailers). The endgame literature also emphasises the importance of monitoring the work of the MOEM. However, the case of the Regie has demonstrated that an appropriate governance structure is challenging within a prevailing SOTM. This is further challenged by the lack of clear accountability mechanisms and a functional regulatory body, which combine to preclude holding the Regie, TTC, and politicians accountable. We note that the endgame proposals did not outline how they could ensure a functional regulatory body; or include clear accountability mechanisms; or how to deal with an MOEM if it begins it behaves similarly to tobacco industry.

Accordingly, for endgame proposals to ensure an appropriate governance structure of the MOEM they need not only to meet their suggested features and characteristics, as summarised in Table 2, but also ensure other actions are met beyond the features in Table 2. Therefore, there is a need to have established a functional independent regulatory agency that works: (i) to create a suitable accountability mechanism for the MOEM; (ii) to ensure when implementing the provision of Article 5.3 of the FCTC [121], they acknowledge the possibility that the MOEM could act similarly as tobacco industry and hence need to be treated as such.

Adjusted financial incentives

The endgame proposals highlight the need to address financial interests to avoid maintaining tobacco sales and acknowledge the need to prevent financial gain. Some proposals suggest earmarking any profit for funding tobacco research, awareness campaigns, and quitting initiatives. The case of the Regie has demonstrated this issue by showing how it acts similarly to the TTC by seeking financial gain. Therefore, the MOEM should: (i) recognise that tobacco taxes can still go to government irrespective of which type of organisation produces tobacco products, and hence only profit related dividends paid to government would need to be avoided; (ii) remain distant and independent of government by limiting its role to providing information to enable taxation, rather than being involved in decision making on taxation.

Further consideration for the endgame literature: Tobacco growing

The investigation of the Regie revealed two issues related to tobacco growing that are of significance to discussions around MOEMs. Firstly, the Regie tends to portray tobacco control as negatively affecting tobacco farming, farmers, and hence supply chain economics, using such arguments as tools to weaken tobacco control in Lebanon while reinforcing the position of TTC [54]. Secondly, the Regie keeps tobacco farmers dependent on tobacco planting by portraying it as a secure source of income [27, 54, 122] and reinforcing this through subsidies. However, unlike the Regie’s claims, tobacco farmers appear willing to shift to other forms of farming if opportunities arise [27, 54], which could allow them to become independent of the politicians, as they would no longer need licensing to execute their work. It is mainly the politicians that control tobacco license distribution and tend to give it to their allies [123].

Hence, any proposal advocating for regulating tobacco growing as part of the operational remit of the suggested MOEM, needs to be aware that, in most cases, totally removing tobacco farming from the supply chain would be extremely difficult. Instead, it needs to be gradually reduced in line with reduction in tobacco use. In other words, farmers can and should be transitioned out of leaf as part of wider tobacco control efforts. Until such a transition can be completed, tobacco farming should be regulated by the same regulatory body (as mentioned above) that regulates the MOEM to avoid adversely impacting tobacco farmer livelihoods. Such regulation might include ensuring tobacco farmers are protected from political interference while also providing them with access to financial support, technical skills training, or markets to sell alternative crops. Such initiatives could be funded by hypothecating profit from the MOEM.

Lessons learnt for Lebanon

Our investigation of the Regie confirmed that endgame strategies are far from the agenda of the Lebanese government. This is mainly related to the lack of priority for public health over financial gain. Nonetheless, within the exploration of the Regie and the endgame strategies for MOEM, there are lessons to be learnt for Lebanon to help it move towards reducing tobacco use consistent with the endgame strategies.

Unlike the simple supply-chain structure illustrated in Fig. 1, the real-world situation of the governance structure and the operational remit of the Regie is much more complex. This is because, in practice, the Regie lacks independence from the government (MOF), the political elites maintain a clientelism relationship with the wholesalers, and the TTCs lobby politicians while bypassing the Regie to establish direct communication with the wholesalers and the retailers. Additionally, a cartel of distributors manipulates the retail price set by the Regie. Figure 2 illustrates these complexities.

Accordingly, in the case of Lebanon, there is a need to address how to ensure an appropriate governance structure and adjust financial incentives.

Ensure proper Governance structure

The main obstacle towards ensuring an appropriate governance structure in the case of the Regie is its political affiliation with, and the interference of, politicians in its work to serve their vested intertest. Therefore, one-way forward is to adapt measures that would break the Regie’s political relationships. The route to achieve this could be by privatising the Regie. However, such an approach is unrealistic at the moment, and would in any case be difficult within the Lebanese sectarian based political system. In addition, the Regie, supported by the TTC, has always opposed such an approach [124]. A recent study [122] also concluded that privatisation would be unlikely and even undesirable given the high level of corruption, lack of sound regulatory measures and transparency that could lead to rapid gain of revenue by the politicians and their partners.

Another route would be to sustain the Regie in its current form but enhance the regulatory role of the NTCP [65]. This seems much more plausible, although to achieve it, the NTCP would have to: (i) put in place accountability mechanisms to hold the Regie accountable for its decisions and to prevent the Regie from jeopardising the public health of the Lebanese population in its drive for profit; (ii) draft guidelines (in line with the provision of Article 5.3 [121]) to prevent government officials from communication with the tobacco industry and any possible collaboration with them [43] and; (iii) enhance its employees professionalism and independence by ensuring proper pay and benefits.

Adjusted financial incentives

Given the Lebanese context of weak governance, economic instability, and endemic corruption [45, 51, 53, 125], not to mention the fact that the Regie generates significant income for the state [122], regulating financial incentives is complex. Hence, one way forward would be to address the dependance of the Lebanese government on the Regie’s revenue. To achieve this there is a need to earmark profits away from government. The MOF would still collect money from tobacco taxes (but not from profit dividends). If this were implemented, it would de-incentivise it from growing its market and potentially it could therefore restrict the work of the Regie.

Furthermore, another means to control financial incentives from the sale of tobacco products could see the Regie taking over the role of the distributor in the supply chain, allowing it to directly communicate with retailers, thereby preventing price manipulation. By doing so it could further restrict outlet locations and numbers, and directly control retail prices as suggested by the endgame literature. Or, in the instance the distributors are kept in the market, the Regie could exert meaningful control over their role though enforcing strict regulation such as stopping their license to break the existing cartel and the vested interests between the distributors, TTC, and politicians.

Conclusion

The implementation of tobacco endgame strategies of any type is now closer than ever. New Zealand is currently considering an action plan based on a wider endgame strategy (i.e. non-MOEM) to achieve its ‘Smokefree 2025 goal’ [126, 127]. This paper examined the features of endgame proposals that would introduce some form of monopoly in order to understand what the suggested MOEM is expected to achieve and to explore the extent to which the various features already exist in the case of the Regie, a pre-existing SOTM in Lebanon.

Using the Regie as a practical example allows us to effectively revisit both the potential and the pitfalls of endgame strategies intending to adopt MOEM or intending to reform a pre-existing SOTM to reduce tobacco use in line with endgame models. Specifically, the Regie as an SOTM could encourage similar countries with an SOTM (particularly those in an LMIC context), and also those with state-owned oligopoly tobacco firms, to consider the suggested lessons and potentially start thinking of the possibility of setting endgame goals. However, countries using the lessons learnt from the Regie should account for its specific context and hence adjust accordingly.

The main limitation of this paper is with respect to the data. Given the scarcity of academic literature related to the Regie, much of the data was collected from the Regie website and local media reports. These data sources might have not been entirely independent and free from bias. However, data triangulation was undertaken whenever possible, and we are confident that our results are broadly reliable. Furthermore, we recognise that we were not able to undertake a multisectoral approach [128], which involves considering multiple sectors (e.g. economy, environment, health), which could have generated additional insights given the cross cutting nature of tobacco in terms of advancing an endgame. Future research might productively undertake such a multisectoral approach to investigate the impact of the wider dynamic of an MOEM approach to a tobacco endgame.

The recommendation for countries considering an MOEM and those for Lebanon are aligned, with the key difference being in the implementation. Possibly in the future, there will be a need to draw further lessons from countries that have already implemented endgame strategies with an MOEM, and hence the need of further studies in this area.

Our choice of the Regie was influenced by our knowledge of the Lebanese tobacco control context and we are aware that Lebanon is far from implementing endgame strategies. Nevertheless, by exploring the Regie, we are contributing to the scarce literature on SOTM, especially as we are the first to consider this organisation in this context as far as we are aware [22]. In addition, we are also contributing to the knowledge of endgame strategies by providing lesson learnt for the possible use of MOEM, thereby enhancing their practicality for real-world use.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- FCTC:

-

Framework Convention on Tobacco Control

- GTIII:

-

Global Tobacco Industry Interference Index

- MOEM:

-

Monopoly-oriented endgame model

- MOF :

-

Ministry of Finance

- MPs:

-

Member of parliament

- NTCP:

-

National Tobacco Control Programme

- SOTM:

-

State-owned tobacco monopoly

- TTC:

-

Transnational Tobacco Companies

References

Malone RE, McDaniel PA, Smith EA. Tobacco control endgames: global initiatives and implications for the UK. 2014.

Moon G, Barnett R, Pearce J, Thompson L, Twigg L. The tobacco endgame: The neglected role of place and environment. Health Place. 2018;53:271–8.

van der Eijk Y. Development of an integrated tobacco endgame strategy. Tob Control. 2015;24(4):336–40.

Malone RE. The race to a tobacco endgame. BMJ Publishing Group Ltd; 2016.

Department of Health and Social Office. Advancing our health: prevention in the 2020s – consultation document 2019 [

McDaniel PA, Smith EA, Malone RE. The tobacco endgame: a qualitative review and synthesis. Tob Control. 2016;25(5):594–604.

Smith EA WK. The tobacco endgame. Tob Control 2013;22(Suppl 1).

Borland R. A strategy for controlling the marketing of tobacco products: a regulated market model. Tob Control. 2003;12(4):374–82.

Callard C, Thompson D, Collishaw N. Transforming the tobacco market: why the supply of cigarettes should be transferred from for-profit corporations to non-profit enterprises with a public health mandate. Tob Control. 2005;14(4):278–83.

Malone RE. Imagining things otherwise: new endgame ideas for tobacco control. Tob Control. 2010;19(5):349–50.

Thomson G, Wilson N, Blakely T, Edwards R. Ending appreciable tobacco use in a nation: using a sinking lid on supply. Tob Control. 2010;19(5):431–5.

Khoo D, Chiam Y, Ng P, Berrick AJ, Koong HN. Phasing-out tobacco: proposal to deny access to tobacco for those born from 2000. Tob Control. 2010;19(5):355–60.

Daynard RA. Doing the unthinkable (and saving millions of lives). Tob Control. 2009;18(1):2–3.

Gilmore AB, Branston JR, Sweanor D. The case for OFSMOKE: how tobacco price regulation is needed to promote the health of markets, government revenue and the public. Tob Control. 2010;19(5):423–30.

Callard CD, Collishaw NE. Supply-side options for an endgame for the tobacco industry. Tob Control. 2013;22(Suppl 1):i10–3.

Warner KE. An endgame for tobacco? Tob Control. 2013;22(Suppl 1):i3-5.

Liberman J. Where to for tobacco regulation: time for new approaches? Drug Alcohol Rev. 2003;22(4):461–9.

Thomson G, Wilson N, Crane J. Rethinking the regulatory framework for tobacco control in New Zealand. N Z Med J. 2005;118(1213):U1405.

Gray N. The future of the cigarette and its market. Lancet (London, England). 2004;364(9430):231–2.

Gray N. Time to change attitudes to tobacco: product regulation over five years? Addiction. 2005;100(5):575–6.

Smith EA, McDaniel PA, Hiilamo H, Malone RE. Policy coherence, integration, and proportionality in tobacco control: Should tobacco sales be limited to government outlets? J Public Health Policy. 2017;38(3):345–58.

Hogg SL, Hill SE, Collin J. State-ownership of tobacco industry: a “fundamental conflict of interest” or a “tremendous opportunity” for tobacco control? Tob Control. 2016;25(4):367–72.

Gilmore AB, Fooks G, McKee M. A review of the impacts of tobacco industry privatisation: Implications for policy. Glob Public Health. 2011;6(6):621–42.

Van der Deen FS, Wilson N, Cleghorn CL, Kvizhinadze G, Cobiac LJ, Nghiem N, et al. Impact of five tobacco endgame strategies on future smoking prevalence, population health and health system costs: two modelling studies to inform the tobacco endgame. Tob Control. 2018;27(3):278–86.

Malan D, Hamilton B. Contradictions and Conflicts: State ownership of tobacco companies and the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. 2020.

World Bank Group. Data set Lebanon 2021.

Bazzi AI. The impact of raw tobacco subsidies on the rural economy and environment in Lebanon opportunities and challenges to income diversification in the caza of Bint Jbeil-by Asma Issa Bazzi 2008.

Salloukh BF. Taif and the Lebanese State: The Political Economy of a Very Sectarian Public Sector. Nationalism and Ethnic Politics. 2019;25(1):43–60.

Lebanese Government. Organizing the government’s control over the Regie Libanaise des Tabacs et Tombacs Decree 151. Beirut, Lebanon Lebanese Government 1959. p. 4.

Regie Libanaise de Tabacs et Tombacs. Who We Are [cited 2021 January 1]. Available from: https://www.rltt.com.lb/Article/1/who-we-are/en.

Akoum I. The political economy of SOE privatization and governance reform in the MENA region. Int Sch Res Notices. 2012;2012.

Edwards R, Russell M, Thomson G, Wilson N, Gifford H. Daring to dream: reactions to tobacco endgame ideas among policy-makers, media and public health practitioners. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(1):1–11.

Edwards R, Peace J, Russell M, Gifford H, Thomson G, Wilson N. Qualitative exploration of public and smoker understanding of, and reactions to, an endgame solution to the tobacco epidemic. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:782.

Wilson N, Thomson GW, Edwards R, Blakely T. Potential advantages and disadvantages of an endgame strategy: a “sinking lid” on tobacco supply. Tob Control. 2013;22(Suppl 1):i18-21.

Thomson G, Edwards R, Wilson N, Blakely T. What are the elements of the tobacco endgame? Tob Control. 2012;21(2):293–5.

Liberman J. The future of tobacco regulation: a response to a proposal for fundamental institutional change. Tob Control. 2006;15(4):333–8.

Bates C. The tobacco endgame: A critique of policy proposals aimed at ending tobacco use. The counterfactual: What's the right thing to do? Analytical advocacy–getting beyond the rhetoric of campaigners. 2015.

Braun V, Clarke V. Can I use TA? Should I use TA? Should I not use TA? Comparing reflexive thematic analysis and other pattern‐based qualitative analytic approaches. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research. 2020.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

Bowen GA. Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qualitative research journal. 2009.

Gray DE. Doing research in the real world: Sage; 2013.

Lebanese Parliament. 174: Tobacco Control and Regulation of Tobacco Products’ Manufacturing. Packaging and Advertising. 2011.

Assunta M. Global Tobacco Industry Interference Index 2020. Bangkok, Thailand: Global Center for Good Governance in Tobacco Control (GGTC); 2020 Nov

Nakkash R, Lee K. Smuggling as the “key to a combined market”: British American Tobacco in Lebanon. Tob Control. 2008;17(5):324–31.

Nakkash R, Lee K. The tobacco industry’s thwarting of marketing restrictions and health warnings in Lebanon. Tob Control. 2009;18(4):310–6.

Chaaban J, Naamani N, Salti N. The economics of tobacco in Lebanon: an estimation of the social costs of tobacco consumption full report. Research and Policy-Making in the Arab World. 2010.

Salloum RG, Nakkash RT, Myers AE, Wood KA, Ribisl KM. Point-of-sale tobacco advertising in Beirut, Lebanon following a national advertising ban. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):1–5.

Maziak W, Nakkash R, Bahelah R, Husseini A, Fanous N, Eissenberg T. Tobacco in the Arab world: old and new epidemics amidst policy paralysis. Health Policy Plan. 2014;29(6):784–94.

Salti N, Chaaban J, Naamani N. The economics of tobacco in Lebanon: an estimation of the social costs of tobacco consumption. Subst Use Misuse. 2014;49(6):735–42.

Salti N, Brouwer E, Verguet S. The health, financial and distributional consequences of increases in the tobacco excise tax among smokers in Lebanon. Soc Sci Med. 2016;170:161–9.

Nakkash RT, Torossian L, El Hajj T, Khalil J, Afifi RA. The passage of tobacco control law 174 in Lebanon: reflections on the problem, policies and politics. Health Policy Plan. 2018;33(5):633–44.

Alaouie H, Afifi RA, Haddad P, Mahfoud Z, Nakkash R. Effectiveness of pictorial health warnings on cigarette packs among Lebanese school and university students. Tob Control. 2015;24(e1):e72-80.

Saleh R, Nakkash R, Harb A, El-Jardali F. Prompting Government Action for Tobacco Control in Lebanon during COVID-19 Pandemic. Beirut, Lebanon: Knowledge to Policy (K2P) Center; 2020 May 19.

kanj H. Tobacco leaf farming in lebanon: why marginalized farmers need a better option. Tobacco control and tobacco farming: separating myth from reality: Anthem Press; 2014.

Abu Zaki R. The tobacco fortune and the lost cigarettes Al Akhbar. 2007.

Lebanese President, Prime Minister. Attaching the Tobacco and Tobacco Control Department to the Ministry of Finance. 1950.

Geha C. Sharing Power and Faking Governance? Lebanese State and Non-State Institutions during the War in Syria. Int Spect. 2019;54(4):125–40.

Naharnet Newsdesk. Report: Amal, Hizbullah Insist on Retaining Finance Portfolio. Naharnet. 2020.

Janoubia. Corruption plagues the "Regie" reserve ... Hundreds were employed and billions were wasted 2019 [Available from: https://janoubia.com/2019/11/14/الفساد-ينخر-محمية-الريجي-توظيف-المئ/.

Lebanese labor Watch. The labor union fasted to break the fast on "sectarian" appointments of the parties. online2017 [cited 2021 march 26]. Available from: https://www.lebaneselw.com/index.php/2018-05-30-00-02-31/item/1081-2017-03-15-10-45-16.

Snan F. Core questionnaire of the reporting instrument of who FCTC Lebanon 2016.

Le Borgne E, Jacobs TJ. Lebanon: Promoting Poverty Reduction and Shared Prosperity: The World Bank; 2016.

Organization WH. WHO framework convention on tobacco control. WHO Regional Office for South-East Asia; 2004.

World Health Organization, National tobacco control program. 2020 - CORE QUESTIONNAIRE OF THE REPORTING INSTRUMENT OF WHO FCTC-Lebanon online World Health Organization; 2020 [cited 2021 May 20 ]. Available from: https://untobaccocontrol.org/impldb/wp-content/uploads/Lebanon_2020_WHOFCTCreport.pdf.

Ministry of Public Health. No Tobacco Control Program [cited 2020 December 22]. Available from: https://www.moph.gov.lb/en/Pages/2/3173/tobacco-program.

Organization WH. WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control: Guidelines for Implementation of Article 5. 3, Articles 8 To 14: World Health Organization; 2013.

World Health Organization. Guidelines for implementation of Article 5.3 of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control on the protection of public health policies with respect to tobacco control from commercial and other vested interests of the tobacco industry. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008.

Lebanese Government. Attaching the supervision of the Department of Tobacco Control to the Ministry of Finance. Beirut, Lebanon Lebanese Government 1650. p. 1.

Regie Libanaise de Tabacs et Tombacs. The Regie’s Ambitions: Are there any contradictions between regional and local ambitions? .. Seklaoui: local manufacturing increases our profits and enhances the support of tobacco 2017 [cited 2020 November 22]. Available from: https://www.rltt.com.lb/Article/207/the-regies-ambitions-are-there-any-contradictions/en.

Regie Libanaise de Tabacs et Tombacs. Khalil during the inauguration of the national conference of combating illicit trade: Cedar without reforms to increase the debt burden online2018 [cited 2020 September 9]. Available from: https://www.rltt.com.lb/Article/288/khalil-during-the-inauguration-of-the-national-con/en.

Regie Libanaise de Tabacs et Tombacs. Vision, Mission and Objectives online [updated 2021; cited 2021 January 1]. Available from: https://www.rltt.com.lb/Article/2/vision-mission-and-objectives/en.

Regie Libanaise de Tabacs et Tombacs. Seklaoui for “Al-Sharek”: Our goal is to be one of the best tobacco companies in the MENA region. [cited 2021 January 2]. Available from: https://www.rltt.com.lb/Article/217/seklaoui-for-al-sharek-our-goal-is-to-be-one-of-th/en.

Regie Libanaise de Tabacs et Tombacs. Wazni Receives the 2019 Profits from the Regie and a $1M. Donation to Bring Students Home and Providing Ventilators 2020 [cited 2020 November 13]. Available from: https://www.rltt.com.lb/Article/427/wazni-receives-the-2019-profits-from-the-regie-and/en.

Akiki V. Regie tenders: higher prices win Al Akhbar. 2017.

The Daily Star. Less three years after Lebanon banned smoking in public places, activists are alarmed and disappointed at the apparent rollback of the country’s tobacco-control legislation[cited 2021 May 20 ]. Available from: http://www.dailystar.com.lb/GetArticleBody.aspx?id=288130&fromgoogle=1.

Elnashra. Kidanian: To make amendments to the law banning smoking in public places 2019 [Available from: https://www.elnashra.com/news/show/1318871/كيدانيان:-لادخال-تعديلات-على-قانون-منع-التدخين-ال.

Haboush J. Four years on, is indoor smoking ban a thing of the past? The Daily Star. 2016.

Nammour K. Smoking, the public place and the republic of special interests: When negotiations reach the point of compromising public health and the principle of equality online2012 [updated 2012; cited 2021 May 26 ]. Available from: https://bit.ly/375qol3.

Weatherbee S. Relaxation of smoking ban draws fire. The Daily Star. 2015.

Bu Majed M. A single tax that reflects positively on the citizen, which is forbidden to adopt to finance the chain. Al Nahar. 2017.

Institut des Finances Basil Fuleihan. Citizen budget 2020. 2020.

Wehbi M. One billion pounds is the cost of a committee “without term of reference”. Al Akhbar. 2009.

Al Kintar B. Safadi for Tobacco Companies: "As you wish". Al Akhbar. 2013.

Nakkash R, Al Kadi L. Support for tobacco control research, dissemination and networking: final technical report. 2014.

Oxford Economics. Levant Illicit Tobacco 2019. 2020.

Sandberg E, Gallagher AW, Alebshehy R. Tobacco industry commissioned reports on illicit tobacco trade in the Eastern Mediterranean Region: how accurate are they? East Mediterr Health J. 2020;26(11):1320–2.

Gallagher AWA, Evans-Reeves KA, Hatchard JL, Gilmore AB. Tobacco industry data on illicit tobacco trade: a systematic review of existing assessments. Tob Control. 2019;28(3):334–45.

Regie Libanaise de Tabacs et Tombacs. Import and Export [cited 2020 November 24]. Available from: https://www.rltt.com.lb/Article/27/import-and-export/en.

Global Data. Cigarettes in Lebanon 2018.

Regie Libanaise de Tabacs et Tombacs. “Regie” signs agreement with “Philip Morris” to manufacture its products in Lebanon 2017 [cited 2021 10 september ]. Available from: https://www.rltt.com.lb/Article/256/regie-signs-agreement-with-philip-morris-to-manufa/en.

regie Libanaise de Tabacs et Tombacs. Seklaoui: Lebanon has become the most important Middle East institution for tobacco production. 2018 [cited 2021 10 September ]. Available from: https://www.rltt.com.lb/Article/304/seklaoui-lebanon-has-become-the-most-important-mid/en.

Regie Libanaise de Tabacs et Tombacs. The Regie signs an agreement with British American Tobacco to produce Kent and Viceroy in Lebanon 2019 [cited 2020 September 14]. Available from: https://www.rltt.com.lb/Article/378/the-regie-signs-an-agreement-with-british-american/en.

Kamh A. "Marlboro" is 100% Lebanese ... the box is for 2,500 L.L 2018 March 10 2021 [cited 2021 March 26 ]. Available from: https://www.lebanondebate.com/news/365274.

Carter SM. Going below the line: creating transportable brands for Australia’s dark market. Tobacco Control. 2003;12(suppl 3):iii87-iii94.

World Health Organization. Banning tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship: what you need to know. World health Organization; 2013.

Regie Libanaise de Tabacs et Tombacs. Sustainable development report 2016 2016

Regie Libanaise de Tabacs et Tombacs. The Sports Committee of Regie Libanaise Des Tabacs Et Tombacs [cited 2020 December 25]. Available from: https://www.rltt.com.lb/Article/73/the-sports-committee-of-regie-libanaise-des-tabacs/en.

Regie Libanaise de Tabacs et Tombacs. Regie offers financial grant for the Akkar town of Majdala online2020 [cited 2021 May 20 ]. Available from: https://www.rltt.com.lb/Article/511/regie-offers-financial-grant-for-the-akkar-town-of/en.

AUB Tobacco Control Research Group. letter to the army commender online 2014 [cited 2021 March 26]. Available from: https://www.aub.edu.lb/tcrg/Documents/lettertoarmycommander.pdf.

Lebanese Government. Acceptance of a donation provided by the Lebanese Tobacco and Tobacco Monopoly for the Ministry of National Defense - the Army. 2015.

Regie Libanaise de Tabacs et Tombacs. A contribution from the Regie Libanaise de Tabacs et Tombacs the Lebanese Army to the Lebanese Army Online2021 [Available from: https://bit.ly/3f6kmFc.

Global Center for Good Governance in Tobacco Control. Handbook on Implementation of WHO FCTC Article 5.3. 2018 september

Regie Libanaise de Tabacs et Tombacs. Scholarships for 150 students of tobacco farmers’ children in Marjeyoun and Nabatieh 2016 [cited 2021 January 15]. Available from: https://www.rltt.com.lb/Article/109/scholarships-for-150-students-of-tobacco-farmers-c/en.

Kintar B. The war of “lighters” between Marlboro and Kent … Tobacco companies continue to violate the smoking law. Green ara 2017.

Al Akhbar. Robbing 1.5 billion pounds in 4 days from smokers نهب. Al Akhbar. 2017.

Regie Libanaise de Tabacs et Tombacs. Acquiring a Wholesale License (New or by Assignment) [cited 2021 March 20]. Available from: https://www.rltt.com.lb/Article/117/acquiring-a-wholesale-license-new-or-by-assignment/en.

Salloum RG, Nakkash RT, Myers AE, Eberth JM, Wood KA. Surveillance of tobacco retail density in Beirut, Lebanon using electronic tablet technology. Tob Induc Dis. 2014;12(1):1–4.

Regie Libanaise de Tabacs et Tombacs. The weekly quota 2020 [cited 2020 December 25 2020]. Available from: https://www.rltt.com.lb/DocumentFiles/hosa15-09-2020-637358416994713665.pdf.

Wehbi M. The cartel of Tobacco Al Akhbar 2010.

Chbeir R, Mikhael M. The Lebanese Cigarettes Industry: An Upgraded Production & New Trends [Internet]: Bloominvest Bank 2018 [cited 2020]. Available from: https://blog.blominvestbank.com/26074/the-lebanese-cigarettes-industry-an-upgraded-production-new-trends/.

National News Agency. Regie to weekly publish prices of local tobacco and asks to report breaches of the pricelist Online: National News Agency,; 2021 [Available from: http://nna-leb.gov.lb/ar/show-news/558270/.

Nahar A. اجراء غير مسبوق تعتمده الريجي للجم ارتفاع اسعار المنتجات التبغية. Al Nahar. 2021 January 30

Regie Libanaise de Tabacs et Tombacs. Sustainable development report 2017–2018. 2019.

Chaaya M, Nakkash R, Saab D, Kadi L, Afifi R. Effect of tobacco control policies on intention to quit smoking cigarettes: A study from Beirut. Lebanon Tob Induc Dis. 2019;17:63.

Cairney P, Mamudu H. The global tobacco control “endgame”: change the policy environment to implement the FCTC. J Public Health Policy. 2014;35(4):506–17.

Pratt A. Can state ownership of the tobacco industry really advance tobacco control? Tob Control. 2016;25(4):365–6.

Burki TK. Tobacco control in France. Lancet Respir Med. 2016;4(6):438–9.

Kuijpers TG, Kunst AE, Willemsen MC. Who calls the shots in tobacco control policy? Policy monopolies of pro and anti-tobacco interest groups across six European countries. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):800.

Higashi H, Khuong TA, Ngo AD, Hill PS. The development of Tobacco Harm Prevention Law in Vietnam: stakeholder tensions over tobacco control legislation in a state owned industry. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2011;6:24.

Natalucci F, Adrian T. IMFBLOG insights&analyisis on economics and finance [Internet]. online International Monetary Fund. 2020. [cited 2021]. Available from: https://blogs.imf.org/2020/04/14/covid-19-crisis-poses-threat-to-financial-stability/.

World Health Organization. Technical resource for country implementation of WHO framework convention on tobacco control article 5.3 on the protection of public health policies with respect to tobacco control from commercial and other vested interests of the tobacco industry online: World Health Organization; 2012 [Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241503730.

Kostanian A. Privatization of Lebanon’s Public Assets: No Miracle Solution to the Crisis. Online: Issam Fares institutes; 2021.

Mtayrak S. “Clientalism” is the key to growing southern tobacco! . Al Akhbar. 2008.

Wehbi M. Tobacco manufacturing is banned on Lebanon Al Akhbar. 2010;2010:24.

Dyke J. Old habits die hard. Executive magazine. 2013.

Ministry of Health. Proposals for a Smokefree Aotearoa 2025 Action Plan: Discussion document. . Wellington: Ministry of Health; 2021.

Edwards R, Wilson N, Thomson G. Blog Tobacco Control [Internet]: Tob Control. 2021. [cited 2021]. Available from: https://blogs.bmj.com/tc/2021/05/05/new-zealand-government-proposes-world-leading-action-plan-to-achieve-smokefree-2025-goal/.

Salunke S, Lal DK. Multisectoral approach for promoting public health. Indian J Public Health. 2017;61(3):163–8.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Lindsay Robertson, Piotr Ozieranski, Mateusz Zatonski for their comments on earlier drafts. The responsibility for any errors remains entirely with the authors.

Funding

HA, JRB, and MJB are supported by Bloomberg Philanthropies Stopping Tobacco Organizations and Products project funding (www.bloomberg.org). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HA conceived the original idea for the paper with input from JRB and MJB. HA researched the Regie and the endgame strategies, and wrote the first draft of the paper, with input and guidance from JRB and MJB. All authors reviewed and agreed on the final draft. “The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.”

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

JRB owns 10 shares in Imperial Brands for research purposes. The shares were a gift from a public health campaigner and are not held for financial gain or benefit. All dividends received are donated to health-related charities, and proceeds from any future share sale or takeover will be similarly donated. Other authors declared no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Alaouie, H., Branston, J.R. & Bloomfield, M.J. The Lebanese Regie state-owned tobacco monopoly: lessons to inform monopoly-focused endgame strategies. BMC Public Health 22, 1632 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-13531-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-13531-z