Abstract

Background

Worldwide, physical inactivity (PIA) and sedentary behavior (SB) are recognized as significant challenges hindering the achievement of the United Nations (UN) sustainable development goals (SDGs). PIA and SB are responsible for 1.6 million deaths attributed to non-communicable diseases (NCDs). The World Health Organization (WHO) has urged governments to implement interventions informed by behavioral theories aimed at reducing PIA and SB. However, limited attention has been given to the range of theories, techniques, and contextual conditions underlying the design of behavioral theories. To this end, we set out to map these interventions, their levels of action, their mode of delivery, and how extensively they apply behavioral theories, constructs, and techniques.

Methods

Following the scoping review methodology of Arksey and O’Malley (2005), we included peer-reviewed articles on behavioral theories interventions centered on PIA and SB, published between 2010 and 2023 in Arabic, French, and English in four databases (Scopus, Web of Science [WoS], PubMed, and Google Scholar). We adopted a framework thematic analysis based on the upper-level ontology of behavior theories interventions, Behavioral theories taxonomies, and the first version (V1) taxonomy of behavior change techniques(BCTs).

Results

We included 29 studies out of 1,173 that were initially screened/searched. The majority of interventions were individually focused (n = 15). Few studies have addressed interpersonal levels (n = 6) or organizational levels (n = 6). Only two interventions can be described as systemic (i.e., addressing the individual, interpersonal, organizational, and institutional factors)(n = 2). Most behavior change interventions use four theories: The Social cognitive theory (SCT), the socioecological model (SEM), SDT, and the transtheoretical model (TTM). Most behavior change interventions (BCIS) involve goal setting, social support, and action planning with various degrees of theoretical use (intensive [n = 15], moderate [n = 11], or low [n = 3]).

Discussion and conclusion

Our review suggests the need to develop systemic and complementary interventions that entail the micro-, meso- and macro-level barriers to behavioral changes. Theory informed BCI need to integrate synergistic BCTs into models that use micro-, meso- and macro-level theories to determine behavioral change. Future interventions need to appropriately use a mix of behavioral theories and BCTs to address the systemic nature of behavioral change as well as the heterogeneity of contexts and targeted populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Background

Currently, physical inactivity (PIA) and sedentary behavior (SB) are considered global health challenges hampering the achievement of the United Nations' (UN) third sustainable development goal (SDG). PIA and SB are responsible for 1.6 million deaths per year (27% due to diabetes and 20% due to cardiovascular disease [CVD]) [1]. More than 31% of premature deaths attributed to non-communicable diseases (NCDs) occur in physically inactive populations and are responsible for US $54 billion per year of direct care costs and US $14 billion per year of indirect costs (i.e., a loss of productivity) [1].

It is important to differentiate between three unique concepts: physical activity (PA), PIA, and SB. The WHO defines PA as “any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that requires energy expenditure.” The WHO defines PIA as any activity below the threshold of 150 min per week of moderate or vigorous PA. SB is defined as any waking behavior that leads a person to consume 1.5 metabolic equivalents or less (e.g., sitting, reclining, or lying down) [2].

A recent meta-analysis revealed that prolonged SB is associated with an elevated risk of morbidity and mortality from NCDs. This risk can be reduced or even eliminated by engaging in PA. However, if SB is very high (SB time exceeding 7 h) the risk of mortality and morbidity from NCDs is independent of the level of PA [3]. Both PIA and SB carry a high risk of developing an NCD. PIA is a major risk factor for CVD [4], type 2 diabetes [5], high blood pressure [6], cancer [7] and drug use [8]. However, SB is associated with a 30% increase in CVD [9] as well as a 55% increase in the risk of endometrial cancer [10] and elevated blood pressure [11]. These risks are exacerbated when combined with insufficient PA [12]. Thus, interventions aimed at reducing PIA and SB are estimated to reduce the risk of CVD, type 2 diabetes, depression, and cancer by 35%, 40%, and 35%, respectively [1].

In recent years, increased attention has been given to designing combined interventions, targeting both PIA and SB, to appropriately prevent and contribute to the management of NCDs for better health and well-being outcomes [13]. These interventions need to involve behavioral changes and to be informed by behavioral theories according to the WHO and other global health institutions, communities of researchers, practitioners, and policymakers [14,15,16,17].

Behavioral theories and Behavior Change Techniques (BCT)

Behavioral theories explain why, when, and how an individual behavior does (or does not) occur. They highlight that the mechanism of change at play, if targeted, will alter the behavior at the individual, interpersonal, or community level. These mechanisms are central to the design of theory-informed behavior change interventions (BCI) [19], which are complex social adaptive systems (e.g., multiple health behavioral change interventions (BCIs) targeting simultaneously or sequentially two or more health behaviors, that comprise interacting components and sensitivity to context, with emergent intended and unintended effects at different levels: the individual, interpersonal, community (organizational, environmental, national, and global) levels [20,21,22,23].

According to Hayden [24], behavioral theories can be classified into three categories based on their levels of action: 1) Intrapersonal or individual-level theories focus on personal determinants that influence behavior (e.g., knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and motivation). Examples include the health belief model (HBM) (Hoch, Baum 1958; [25], the theory of planned behavior (TPB) [26], and self-determination theory (SDT) [27]. 2) Interpersonal level theories highlight the influence of others in shaping one’s behavior; social cognitive theory (SCT) [28] is the most commonly used interpersonal-level theory. 3) Community-level theories aim to affect or modify the social systems within which actors interact. These social systems include organizations institutions, and public policies, among others. Examples of community-level theories include diffusion of innovation theory (Valente & Rogers, 1995) [29] and the social ecological model (SEM) [30].

In practice, behavioral theories are translated into BCIs; these are implemented through the use of BCTs, which are interactive, reproducible elements of an intervention that facilitate the alteration of the mechanism of change or the causal pathway toward the intended behavioral outcome [31, 32].

Recent research has urged scholars to place more emphasis on understanding how and in which context a BCI addressing PIA or SB will lead to desired or unexpected outcomes and impacts [33]. However, the answer remains elusive. To close this gap, we aimed to map out the different types of BCIs geared toward PIA and SB and their underlying theories and techniques. We focused on mapping out different interventions to reduce PIA and SB and identified the underlying behavioral theories and BCTs used. We also aimed to assess the extent of behavioral theories use in the design of BCIs. Our review will provide decision-makers and behavioral designers with a unique systematic and comprehensive mapping of BCI targeting PA and SB using behavioral change theories, tools, and techniques.

Methods

We adopted the scoping review methodology as defined by Arksey and O’Malley [34] and refined by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) [35].

Specifying the review question

During different research team meetings, we iteratively refined our review question as follows: What are the different behavioral theories and BCTs used in theory-informed interventions focused on PIA and SB? To construct a suitable search strategy, we employed the health behavior, health context, exclusion, models, and theories (BeHEMoth) framework [36, 37] (see Table 1), which is especially relevant for identifying interventions based on behavioral theories. We then followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) reporting guidelines to report the results of our scoping review [38].

We included only interventions addressing PIA and SB or both. We excluded interventions adressing other health behaviors such as,nutrition, smoking, and sleep (see Table 2).

Search strategy

We searched four databases (Scopus, Web of Science [WoS], PubMed, and Google Scholar) (see Supplementary file 1 and Table 2). We manually searched for gray literature on institutional sites and used reference tracking to identify additional papers. We combined search terms for theories (“Logic model” OR “Theory of change” OR “Outcome of change” OR “Program* theory” OR "Program*logic" OR “Logical framework” AND “Behavioral change intervention”) with search terms addressing BCIs: “Behavioral change interventions” AND keywords for “physical activity” OR “sedentary” OR “physical inactivity” OR “exercise” OR “fitness.”

Study selection

The study selection was carried out by two researchers, HK and ZB. We included only empirical studies of interventions addressing SB, PIA, or PA that explicitly used behavioral theories in the context of healthcare. Table 2 guided the definition of our inclusion criteria using the PCC (population, concept, context) framework (JBI) [35]. We included papers published in French, English, and Arabic between January 2010 and November 2023. All study designs were included. We excluded reviews, study protocols, feasibility studies, books, book chapters, commentaries, and letters to editors (See supplementary file 2).

Data charting

Data extraction was guided by, and adapted from the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Review of Interventions for describing the characteristics of interventions [39] (see Table 3). We first extracted data about the general characteristics of the included studies (author, year, country, type of article, study population). Then, we extracted data about the following characteristics of behavioral theories -informed interventions: 1) theories, models or conceptual frameworks; 2) types of interventions; 3) behavioral theories; 4) BCTs; 5) targeted behavior (SB, PIA, PA, or both); and 6) level of intervention (individual, interpersonal, and environmental) (see supplementary file 3).

Data analysis, coding and synthesis

BCI

As we aimed to identify the underlying behavioral theories and BCTs used to inform the design of BCIs, we employed a BCI upper-level ontology [40] that coded different forms of BCIs. This taxonomy provides a helpful model for systematically and uniformly describing the upper-level components of BCIs; this enabled us to describe BCIs based on theory and to create a map of the different contexts, BCI content, mode of delivery, and BCI outcomes (see Table 4 and supplementary file 4).

Mode of delivery

We coded the different modes of delivery using the taxonomy developed by [41].

Behavioral theories

To comprehensively describe the theories used to inform the design of interventions, we used the taxonomy of behavioral theories developed by Michie [19] and we refined it based on Hayden [24]. This taxonomy outlines key behavioral theory constructs (definitions, interest, use, the context of theory development).

We further assessed the intensity and degree of theory use in BCIs (an analysis of how interventions have actually been implemented according to the stated theory) as developed by Michie, 2010 [42] and refined by Bluethmann, 2017 [43] to fit the context of PA. This taxonomy included the following criteria: 1) a theory was mentioned, 2) relevant constructs were targeted, 3) each intervention technique was explicitly linked to at least one theoretical construct, 4) participants were selected or screened based on prespecified criteria (e.g., a construct or predictor), 5) interventions were tailored to different subgroups, 6) at least one construct or theory mentioned in relation to the intervention was measured post-intervention, 7) all measures of theory were presented with some evidence of their reliability, and 8) the results were discussed in relation to the theory.

The most prevalent theories are the transtheoretical model (TTM) of change [44], the TPB [26], SCT [28], information motivation behavior (IMB) [45], the HBM [46], SDT [27], and the health action process approach (HAPA) [19, 47].

Behavioral change techniques (BCTs)

We finally coded the BCTs using the V1 taxonomy [31]. The taxonomy of BCTs synthesizes 93 BCTs classified into 16 domains: 1) goals and planning, 2) feedback and monitoring, 3) social support, 4) shaping knowledge, 5) natural consequences, 6) comparison of behavior, 7) associations, 8) repetition and substitution, 9) comparison of outcomes, 10) rewards and threats, 11) regulation, 12) antecedents, 13) identity, 14) scheduled consequences, 15) self-belief, and 16) covert learning.

Results

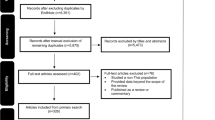

Search results

As indicated in Fig. 1, we identified a total of 1,173 studies during systematic searches in four electronic databases. After removing duplicates (n = 165), we screened 1,027 articles for eligibility. We excluded 945 studies during the title and abstract screening. We extracted and analyzed 82 full-text studies for eligibility and excluded 53 (see the reasons for exclusion in Fig. 1 and Supplementary File 2). We screened the reference lists of the included studies for additional relevant articles (n = 19). We finally included a total of 29 articles.

In the following paragraphs, we describe the general characteristics of the included studies, the features of theory-informed BCIs (the intervention model, behavioral theories, and BCTs), and the extent of theory use in the included studies.

General characteristics of the included studies

Most of the included studies were carried out in high-income countries (n = 23): the US (n = 5) [48,49,50,51,52], the UK (n = 5) [53,54,55,56], Australia (n = 3) [57,58,59], Belgium (n = 3) [60,61,62], the Netherlands (n = 2) [63, 64], Canada (n = 2) [65, 66], Jordan (n = 2) [67, 68], Iran (n = 2) [69, 70], Italy (n = 1) [71], Qatar (n = 1) [72], Portugal (n = 1) [73], Spain (n = 1) [74], and Germany (n = 1) [75].

Intervention duration

The duration of the BCIs varied from six weeks to three years. Most interventions were carried out in a short period, ranging from one to four months (n = 14); others lasted five to six months (n = 7). Only six interventions lasted over twelve months (n = 6) (see Table 5).

Study design, context, and participants

All studies used experimental designs, including randomized controlled trials (n = 13), cluster randomized trials (n = 6), and multisite RCTs (n = 2) and quasi-experimental studies (n = 8). These studies took place in diverse settings and targeted various populations (see Table 5).

Nine studies were conducted in the workplace [50, 56,57,58, 61, 63, 70, 72, 75]. Seven studies reported interventions for people with chronic illnesses, diabetes (n = 3) [65, 69, 71], obesity (n = 1) [48], cardiovascular disease (n = 1) [68], and Parkinson’s disease (n = 1) [64] as well as for survivors of breast cancer (n = 1) [59]. Other studies included different groups such as older adults (n = 4) [52, 55, 66, 76], healthy adults (n = 2) (53. 62), university students (n = 2) [67, 74], and preschool children (n = 2) [51, 54] (see Table 5).

Description of theory based BCI

In our scoping review, we identified 29 articles describing interventions informed by behavioral theories targeting SB and PIA. Among these, fifteen articles aimed to address PIA to meet guideline recommendations, while eleven focused on reducing SB. Three articles combined interventions to reduce SB and increase PA (see Table 6).

In the following, we will describe the content of BCIs, levels of interventions, mode of delivery and reported outcomes (see Table 6).

Content of BCIs

Most BCI interventions adopted educational methods (n = 20) aimed at raising awareness of the importance of meeting PA recommendations and breaking the vicious cycle of SB [18, 48, 51, 53,54,55,56, 59, 62, 64,65,66,67, 69,70,71, 73, 75, 76, 79]. These interventions also included communication strategies (n = 14): motivational interviews (n = 4) [68, 75, 76, 80], and coaching (n = 10) (face-to-face consultations or phone calls) [18, 53, 57, 59, 62, 64, 65, 67, 71, 73]. Social support to implement interventions was used nine times [51, 52, 56, 57, 62, 66, 69, 76, 79], and physical exercise training was used 8 times [52, 54, 64, 66, 70, 71, 73,74,75,76, 80]. Finally, digital interventions (devices, desktops, m-health) were used in most interventions (n = 16)0.2

Levels of interventions

The majority of interventions involved individual-level BCIs (n = 15). Few studies combined the individual level of the interpersonal level (e.g., peer support) (n = 6) [52, 56, 62, 66, 69, 76], and six studies combined the individual level with organizational-level interventions (n = 6) [50, 51, 54, 63, 71, 72]. Only two studies can be described as systemic BCIs addressing the individual, interpersonal, and organizational levels (n = 2) [57, 79] (see Table 6).

Heterogeneity of modes of delivery

The modes of delivery of BCIs were often mixed. BCIs included face-to-face delivery in most cases (n = 24) with single individuals (n = 6) [57, 59, 64, 65, 68, 73] or with groups of people (n = 10) [18, 48, 51, 54, 56, 69,70,71, 74, 76] or a combination of both modes of delivery (n = 8) [52, 53, 55, 58, 62, 66, 67, 75]. The electronic mode of delivery was often employed (n = 15), including messaging (n = 3) [67, 68, 70], computer-based delivery (n = 6) [48, 61, 63, 72, 74, 77], and digital devices (wearable or mobile devices) (n = 13) [18, 48, 50, 53, 58, 59, 61, 63, 65,66,67, 71, 74]. The printing mode of delivery was also utilized less frequently (n = 10).

Reported outcomes

Twenty-five of the 29 interventions mentioned a decrease in PIA and SB, while four studies [18, 54, 65, 74] found no changes in SB or PIA. These four interventions specifically targeted preschool children, school-age students, and adults at risk of diabetes. Four studies reported mixed results and inconclusive evidence. One study showed a significant decline in SB without any change in the level of PA [72] (see Table 6).

Behavioral theories

Our scoping review showed that the authors of the included studies referred to 15 behavioral theories (n = 15) (see Table 7 and Supplementary file 5). Most of the included studies used at least one of the four following theories: SCT (n = 14), SDT (n = 6), the TTM (n = 6), the TPB (n = 6), the SEM (n = 5), and the HBM (n = 5). Most interventions used either a single theory (n = 13) or a combination of two BCTs (n = 12). Only two interventions did not explicitly define the theoretical constructs guiding the development of the BCIs.

The SCT was the most commonly used theory. Five interventions used SCT as a single theory (n = 5) [48, 50, 51, 62, 69], whereas eight employed a combination of other behavioral theories: SDT [65], TPB [6, 68, 65], TTM [64, 65], HBM, SEM [57, 64,65,66, 79], behavioral choice theory [18], and protection motivation theory (PMT) [65]. Interventions rooted in SCT addressed specific psychological and social constructs ranging from one to four constructs per intervention. The most frequently used constructs were self-efficacy, self-regulation, observational learning, and positive reinforcement (see Table 5). SCT was used almost equally to reduce SB and PIA.

PA interventions mostly involved individual behavioral theories (SDT, SRT, TPB, TTM, HAPA), with a focus on reducing the intention-to-action gap. Conversely, the theories employed to reduce SB are primarily interpersonal (SCT, SET, SiS) and environmental (SEM). They seek to make behavior more socially acceptable, encouraging and influencing the behavior of others. Additionally, restructuring the environment is a central component of interventions aimed at reducing SB in the workplace.

Our scoping review showed that most interventions targetted the following individual-level constructs: self-efficacy (n = 16), motivation (n = 10), self-regulation [9], and the interpersonal level illustrated by using subjective norms (n = 5) and basic psychological needs (n = 4). Few studies have addressed environmental factors (e.g., institutional, community, society) (n = 7). The SB interventions used essentially socioecological constructs (n = 4) and enhanced self-efficacy (n = 6), self-regulation (n = 5), and modeling (n = 4). PIA BCI interventions were more centered on individual-level constructs such as motivation (n = 10), intention (n = 5), and controlled volition (n = 6) (see Table 8 and Supplementary file number 2).

Our scoping review revealed some discrepancies in the characteristics of PIA interventions compared with those of SB interventions. The latter were considered systemic interventions based on SCT and SEM. They combined multilayered actions at the macro-level (environmental restructuring), the meso-level (social and peer pressure) and the micro-level (by activating intrapersonal and interpersonal mechanisms of change). In contrast, BCI targeting PIA were mostly focused on the individual level of change by using individual intrapersonal theories (SDT, TTM, TPB, HAPA, and PMT).

Behavior change techniques

All interventions were designed as multicomponent interventions integrating various behavior change techniques (see Table 7).

Our scoping review revealed that the scholars of the included studies used a set of 25 BCTs. On average, six to nine BCTs were used in an intervention (a minimum of 5 and a maximum of 12).

Social support, which is unspecified, was the most commonly used type of BCTs and involved targeting the interpersonal level (social influence) (n = 28), followed by goal setting, targeting the individual level (goal and intention) (n = 24); solving problems and identifying barriers at the individual level (belief capability) (n = 18); instruction on how to perform behavior at the individual level; self-monitoring of behavior (n = 17); feedback on the outcome of behavior at the individual level (n = 14); information about health consequences at the individual level (n = 14); social rewards targeting the interpersonal level (reinforcement and social influence) (n = 9); restructuring the physical environment targeting the environmental level (n = 6); and materiel rewards, targeting the interpersonal level (reinforcement) (n = 4). In our scoping review, most BCTs targeted the interpersonal level and the individual level followed by the environmental level.

Common characteristics of BCI with no modifications to PIA or SB

These interventions were based on educational, self-monitoring and the use of a coaching strategy involving distinct connected devices that targeted adults at risk of metabolic diseases or diabetes type 2) [18, 65] or preschool children, students, and adults at risk of metabolic diseases [54, 74], or a single individual level of behavioral change. They used face-to-face training sessions. Key contextual conditions that prevent the effectiveness of theory-informed interventions include the absence of parental involvement in BCTs targeting children [54], a lack of peer support in interventions involving students [74], and the absence of illness in interventions targeting adults [18, 65].

Description of studies reporting positive changes in PIA and SB

The included studies, mostly carried out in the workplace (n = 9), used a combination of education, training, and communication strategies (motivational interviews or coaching), along with social support and environmental restructuring. The included studies emphasized the importance of systemic-level interventions combining actions at the individual (face-to-face and digital interventions using wearable devices, desktops, and apps) and interpersonal (social support and group interventions) levels with macro-level environmental restructuring. Environmental restructuring encompasses interventions such as installing pedals and workstations, sending email reminders, and even using digital health apps [50, 57, 58, 63, 72]; it also focuses on reinforcing the knowledge and skills of actors and providing social support through group interventions. In contrast, other studies reported that BCIs targeting individuals with chronic diseases (e.g., CVD [68], diabetes [65, 69, 71], Parkinson’s disease [64], obesity [48], and cancer survivors [59] are essentially individually focused and underwent substantive changes in PIA and SB. These studies suggest that patients with NCDs are more committed to education and that coaching interventions intrinsically motivate people to follow PA recommendations [59, 64, 68, 71].

Intensity of theory use

We found heterogeneous use of theory in the implemented interventions. Fifteen interventions involved an intensive degree of theory use (level 3). Eleven interventions entailed moderate levels of theory (Level 2), and three interventions utilized a low level of theory (Level 1) (see Table 9).

Discussion

In sum, our scoping review showed that most interventions used a combination of similar modes of delivery, design, and components (education, training/coaching, regulation, and the use of connected devices), and BCIs were mostly individually focused and based, in most cases, on education and self-monitoring.

Most interventions were focused on individual levels of behavior changes and involved a multitude of intrapersonal behavioral theories and wearable devices for monitoring, using diverse BCTs with a focus on social support and goal setting. Only two studies can be considered systemic level theory informed BCIs addressing both individual intrapersonal drivers (e.g., motivation, attitude, perceived norms, self-efficacy, etc.) combined with interpersonal interventions (group and social support interventions) and macro-level interventions, such as environmental restructuring in the workplace.

Our scoping review indicated that single digital technology-based web apps informed by intrapersonal theories, such as the TPB, self-regulation, and SDT, had no significant effects. Hence, there is a need to combine intrapersonal theories with interpersonal and environmental interventions for better adherence to interventions and the adoption of a desired behavior [81, 82]. Indeed, interventions informed by the HBM, aimed at addressing an individual’s perceptions of PA and increasing one’s level of PA, have shown no significant effect [83].

The relevance of systemic theory informed BCIs stems from the complexity of causal processes underlying SB and PIA, which are considered a consequence of intricate interactions between intertwined levels of structure and agency [16, 18]. PIA and SB are influenced by individual, interpersonal, and organizational and broader contextual factors [84] (Heath et al., 2012). At the individual level, behavior is defined by people’s awareness, cognition, beliefs, and skills. At the interpersonal level, behavior is impacted by the extent to which social support is received from family and friends. At the organizational level, behaviors are constrained by cultural norms and practices in the workplace. At the broader level, behaviors are constrained by contextual factors at the national and global levels, such as legal frameworks, environmental restructuring, political and socioecological factors shaping individuals’ architecture of choice, and their day-to-day decision-making [16, 18].

This suggests the importance of considering the notion of “reciprocal determinism,” which refers to the dynamic interaction between personal social, and environment factors and behavior [24]. The environment plays a significant role in the acquisition of PA behaviors and, consequently, in behavioral change [85]; it can encompass the immediate environment around the individual (one’s parents, workplace, neighbors, and community) as well as the interpersonal environment of the community. As such, PA is conditioned by the individual’s motivation (which can be intrinsic or extrinsic) [86], physical ability, social support, the availability of wearable device pedometers or accelerometers [87] and the existence of an enabling living environment (sport fields, space, resources), and regulatory enabling policies (breaks/leave from work, health insurance) [16].

At the national and global levels, individual behaviors are often constrained or facilitated by national legal contexts and restructuring policies of the built environment, including public transit, green spaces, parks, and recreational facilities [88]. Thus, environmental restructuring can be a good example of the complementarity and synergies of interventions, as shown by Dugdill, who highlighted the relevance of macro-level interventions to alter the workplace, where people spend a great deal of time. Systemic interventions, in line with those used by [89, 90], that combine multiple levels of interventions (individual, interpersonal, and environmental) may have synergistic effects on behavioral changes compared with individually focused interventions (face-to-face and digital interventions).

Our review underscores the importance of environmental restructuring as a complementary intervention to individually focused BCIs. In the workplace, this can include promotion of managers’ leadership such that they serve as role models for employees, as suggested by [91,92,93]. As a consequence, employees may perceive strong social influence and peer pressure, which may increase their self-efficacy and self-regulated behaviors [94]. These interventions seem to foster social identification, social comparison, and socialization mechanisms by increasing individuals’ adherence to BCIs in the workplace [91,92,93].

In addition, at the organizational level, employees’ behaviors are often influenced by organizational policies promoting PA in the workplace [87]. Moreover, the broader context plays a role in shaping the individuals’ behaviors. For instance, Davis [21] reported that behavioral modeling is only effective if individuals see other active people in their social context. Other scholars have shown that a lack of perceived security (crimes, sexual harassment, incivility) may reduce people’s willingness to carry out outdoor PA [95].

Our scoping review indicates that in the context of school BCIs, in line with other findings [96, 97], children may also benefit from systemic interventions by reducing their screen time usage through school policies and receiving individual training sessions to enable them to reduce their SB while also engaging with their parents (interpersonal and social influence) through role modeling. However, more attention is needed to develop systemic BCIs based on multiple-level interventions, such as individual coaching, mentoring, interpersonal social support, and altering the physical and cultural environment [98].

Our scoping review, in line with [82, 94, 99] and [100], has shown the usefulness of SCT in explaining how the training and empowerment of individuals enhance their self-efficacy, self-regulation, their perceived benefits, and risk and control volition, which may prove appropriate in the context of PA and SB interventions.

Our scoping review demonstrated, in line with previous systematic reviews [101], that using a combination of multiple behavioral change techniques is associated with an increased overall effect of the intervention and the adoption of desired behavioral outcomes. Techniques include, for instance, social support, goal setting, and self-monitoring, in line with other studies [102, 103].

Figure 2 shows a tentative integrative framework that incorporates three levels of interventions (environmental, interpersonal, and intrapersonal) and may be useful for helping program designers to build theory informed BCIs on the basis of a multilayered theoretical model. For instance, at the intrapersonal level, one might use the HBM combined with the TTM and SDT. However, at the interpersonal level, program designers might use SCT and behavioral choice theory. At the environmental level, one can use environmental theories such as social influence strategies ( see Fig. 2).

These constructs serve as mechanisms of action at the individual and interpersonal levels. This finding aligns with the results regarding the contribution of SCT and its constructs in predicting and adopting active behavior.

Study limitations and research gaps

In our review, we identified a lack of comprehensive reporting by scholars of key theoretical constructs underlying the design of BCI. We may have missed other relevant literature, as we had to make some trade-offs between comprehensiveness, depth of analysis and feasibility (Arksey, 2005). However, we performed a systematic, comprehensive search of four databases, including Google Scholar, to identify contextually rich gray literature. In addition, two reviewers screened the titles and abstracts, and extracted the data. Our findings also suggest that many theory-informed interventions do not use theoretical constructs appropriately; however, a call for improving the reporting and quality of intervention fidelity is needed while promoting the use of standardized tools such as Michie’s taxonomy of BCIs [40] and BCTs [104].

Our scoping review included only experimental studies that lacked sufficient descriptions of the role of context in shaping the characteristics of interventions and their mechanisms of action. Thus, more attention should be paid to promoting evaluation using context-sensitive methods and approaching theory-based evaluation, realistic evaluation [105], qualitative comparative analysis [106], and contribution analysis [107]. Further research is needed to unpack the black box of behavioral theories -informed interventions by unraveling what works for whom and in what context.

Further studies are also needed to examine the role of individual and digital interventions, which we insufficiently explored in our review. More rigorous systematic and meta-analyses are needed to complement the results of this descriptive, explorative scoping review and to provide evidence of the effectiveness of Theory -informed BCI [85].

Conclusion

Our review offers an innovative approach to systematically categorize behavioral theories interventions using a set of appropriate behavioral theories taxonomies, tools, and techniques, and provides working examples of how these taxonomies can be applied to assess the theory use and the described characteristics of BCT theory-informed interventions. Our study suggests an integrative framework to help program designers develop interventions while implying that specific behavioral theories and BCTs can be used at every level of intervention (the individual, interpersonal and environmental, policy and global levels). In sum, the congruence between behavioral theories, the implementation settings, and the characteristics of the targeted subpopulations needs to be considered when designing behavioral theories interventions to reduce PIA and SB. One size does not fit all. We also recommend, in line with (Noar et al., 2008), that behavioral change practitioners select theories and techniques based on their congruence with participants’characteristics and the nature of the context.

Availability of data and materials

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Abbreviations

- BCI:

-

Behavior Change theory based Intervention

- BCIO:

-

Behavior Change Intervention Ontology

- BCTs:

-

Behavior Change Techniques

- BeHEMoth:

-

Health behavior, health context, exclusion, models and theories

- C Gr:

-

Control group

- HAPA:

-

Health Action Process Approach

- HBM:

-

Health Belief Model

- IMB:

-

Information Motivation Behavior

- Int Gr:

-

Intervention Group

- JBI:

-

Joanna Briggs Institute

- M-RCT:

-

Multi-site Randomized Control Trial

- MoD:

-

Mode of delivery

- NCDs:

-

Non-Communicable Diseases

- PA:

-

Physical Activity

- PIA:

-

Physical Inactivity

- PMT:

-

Protection Motivation Theory

- QES:

-

Quasi-Experimental Study

- RCT:

-

Randomized Control Trial

- SB:

-

Sedentary behavior

- SCT:

-

Social Cognitive Theory

- SDT:

-

Self Determination Theory

- SEM:

-

Social Ecological Model

- SET:

-

Self-Efficacy Theory

- SiSt:

-

Social influence Strategy

- TPB:

-

Theory of Planned Behavior

- TTM:

-

Transtheoretical Model of Change

- V1:

-

First version

- WHO:

-

World Health Organisation

- WoS:

-

Web of Sciences

References

WHO. Global action plan on physical activity 2018–2030: more active people for a healthier world. 2019. Disponible sur: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789241514187. Cité 28 sept 2023

WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour [Internet]. [cité 26 févr 2024]. Disponible sur: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240015128

Wu J, Fu Y, Chen D, Zhang H, Xue E, Shao J, et al. Sedentary behavior patterns and the risk of non-communicable diseases and all-cause mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. Oct2023;146: 104563.

Ricci NA, Cunha AIL. Physical Exercise for Frailty and Cardiovascular Diseases. In: Veronese N, éditeur. Frailty and Cardiovascular Diseases : Research into an Elderly Population [Internet]. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2020 [cité 29 sept 2023]. p. 115‑29. (Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology). Disponible sur: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-33330-0_12

Danaei G, Ding EL, Mozaffarian D, Taylor B, Rehm J, Murray CJL, et al. The preventable causes of death in the United States: comparative risk assessment of dietary, lifestyle, and metabolic risk factors. PLoS Med. 2009;6(4):e1000058.

Diaz KM, Shimbo D. Physical Activity and the Prevention of Hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep déc. 2013;15(6):659–68.

McTiernan A, Friedenreich CM, Katzmarzyk PT, Powell KE, Macko R, Buchner D, et al. Physical Activity in Cancer Prevention and Survival: A Systematic Review. Med Sci Sports Exerc juin. 2019;51(6):1252–61.

MichaelT Bardo, WilsonM Compton. Does physical activity protect against drug abuse vulnerability? Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2015;153:3–13.

Onagbiye S, Guddemi A, Baruwa OJ, Alberti F, Odone A, Ricci H, et al. Association of sedentary time with risk of cardiovascular diseases and cardiovascular mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Preventive Medicine. 2024;179.

Yuan L, Ni J, Lu W, Yan Q, Wan X, Li Z. Association between domain-specific sedentary behaviour and endometrial cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2023;13(6):e069042.

Lee PH, Wong FKY. The association between time spent in sedentary behaviors and blood pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med juin. 2015;45(6):867–80.

Katzmarzyk PT, Powell KE, Jakicic JM, Troiano RP, Piercy K, Tennant B, et al. Sedentary Behavior and Health: Update from the 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee. Med Sci Sports Exerc juin. 2019;51(6):1227–41.

Bull FC, Al-Ansari SS, Biddle S, Borodulin K, Buman MP, Cardon G, et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54(24):1451–62.

Hutchison AJ, Breckon JD, Johnston LH. Physical Activity Behavior Change Interventions Based on the Transtheoretical Model: A Systematic Review. Health Educ Behav. 2009;36(5):829–45.

Finlay A, Evans H, Vincent A, Wittert G, Vandelanotte C, Short CE. Optimising Web-Based Computer-Tailored Physical Activity Interventions for Prostate Cancer Survivors: A Randomised Controlled Trial Examining the Impact of Website Architecture on User Engagement. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(21):7920.

Biddle SJH, Mutrie N, Gorely T. Psychology of Physical Activity: Determinants, Well-Being and Interventions [Internet]. 3e éd. Routledge; 2015 [cité 28 sept 2023]. Disponible sur: https://www.perlego.com/book/2192558/psychology-of-physical-activity-determinants-wellbeing-and-interventions-pdf

Bach Habersaat K, Altieri E. Behavioural Sciences for Better Health: WHO Resolution and Action Framework. Eur J Public Health. 2023;33(Suppl 2):ckad160.463.

Biddle SJH, Edwardson CL, Wilmot EG, Yates T, Gorely T, Bodicoat DH, et al. A Randomised Controlled Trial to Reduce Sedentary Time in Young Adults at Risk of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Project STAND (Sedentary Time ANd Diabetes). PLoS ONE. 2015;10(12): e0143398.

Susan Michie, Robert West, Rona Campbell, Jamie Brown, Heather Gainforth. ABC of Behaviour Change Theories Book - An Essential Resource for Researchers, Policy Makers and Practitioners [Internet]. Silverback Publishing. 2014 [cité 29 sept 2023]. Disponible sur: http://www.behaviourchangetheories.com/

Hagger MS, Cameron LD, Hamilton K, Hankonen N, Lintunen T. The Handbook of Behavior Change. Cambridge University Press; 2020. 730 p.

Davis R, Campbell R, Hildon Z, Hobbs L, Michie S. Theories of behaviour and behaviour change across the social and behavioural sciences: a scoping review. Health Psychology Review. 2015;9(3):323–44.

Bamuya C, Correia JC, Brady EM, Beran D, Harrington D, Damasceno A, et al. Use of the socio-ecological model to explore factors that influence the implementation of a diabetes structured education programme (EXTEND project) inLilongwe, Malawi and Maputo, Mozambique: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1355.

Heino MTJ, Knittle K, Noone C, Hasselman F, Hankonen N. Studying Behaviour Change Mechanisms under Complexity. Behavioral Sciences mai. 2021;11(5):77.

Joanna Hayden. Introduction to health behavior theory [Internet]. THIRDEDITION. Burlington, MA : Jones & Bartlett Learning, [2019; 2019. 747 p. Disponible sur: https://lccn.loc.gov/2017038327

Rosenstock IM, Strecher VJ, Becker MH. The Health Belief Model and HIV Risk Behavior Change. In: DiClemente RJ, Peterson JL, éditeurs. Preventing AIDS: Theories and Methods of Behavioral Interventions [Internet]. Boston, MA: Springer US; 1994 [cité 26 févr 2024]. p. 5‑24. (AIDS Prevention and Mental Health). Disponible sur: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-1193-3_2

Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 1991;50(2):179–211.

Deci EL. Effects of externally mediated rewards on intrinsic motivation. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1971;18(1):105–15.

Bandura A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84(2):191–215.

Valente T. Network models of the diffusion of innovations. Computational & mathematical organization theory. 1 janv. 1995;2:163–4.

Bronfenbrenner U. Developmental Research, Public Policy, and the Ecology of Childhood. Child Dev. 1974;45(1):1–5.

Abraham C, Michie S. A taxonomy of behavior change techniques used in interventions. Health Psychol. 2008;27(3):379–87.

Carey RN, Connell LE, Johnston M, Rothman AJ, de Bruin M, Kelly MP, et al. Behavior Change Techniques and Their Mechanisms of Action: A Synthesis of Links Described in Published Intervention Literature. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2019;53(8):693–707.

Brug J, Oenema A, Ferreira I. Theory, evidence and Intervention Mapping to improve behavior nutrition and physical activity interventions. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2005;2(1):2.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Peters MD, Marnie C, Tricco AC, Pollock D, Munn Z, Alexander L, et al. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI evidence synthesis. 2020;18(10):2119–26.

Carroll C, Booth A. Quality assessment of qualitative evidence for systematic review and synthesis: Is it meaningful, and if so, how should it be performed? Research Synthesis Methods. 2015;6(2):149–54.

Booth A, Carroll C. Systematic searching for theory to inform systematic reviews: is it feasible? Is it desirable? Health Info Libr J. 2015;32(3):220–35.

Andrea C. Tricco, Erin Lillie, Wasifa Zarin, Kelly K. O’Brien, Heather Colquhoun, Danielle Levac, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation | Annals of Internal Medicine. Annals of Internal Medicine [Internet]. 2 oct 2018 [cité 29 sept 2023];169(7). Disponible sur: https://www.acpjournals.org/doi/full/https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Chandler J, Welch VA, Higgins JP, et al. Updated guidance for trusted systematic reviews: a new edition of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;10:ED000142.

Michie S, West R, Finnerty AN, Norris E, Wright AJ, Marques MM, et al. Representation of behaviour change interventions and their evaluation: Development of the Upper Level of the Behaviour Change Intervention Ontology. Wellcome open research [Internet]. 2020 [cité 28 févr 2024];5. Disponible sur: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7868854/

Marques MM, Carey RN, Norris E, Evans F, Finnerty AN, Hastings J, et al. Delivering Behaviour Change Interventions: Development of a Mode of Delivery Ontology. Wellcome Open Res. 2021;5:125.

Michie S, Prestwich A. Are interventions theory-based? Development of a theory coding scheme. Health Psychol. 2010;29(1):1–8.

Bluethmann SM, Bartholomew LK, Murphy CC, Vernon SW. Use of Theory in Behavior Change Interventions: An Analysis of Programs to Increase Physical Activity in Posttreatment Breast Cancer Survivors. Health Educ Behav avr. 2017;44(2):245–53.

Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC, Norcross JC. In Search of How People Change: Applications to Addictive Behaviors. Addictions Nursing Network. 1993;5(1):2–16.

Fisher JD, Fisher WA, Bryan AD, Misovich SJ. Information-motivation-behavioral skills model-based HIV risk behavior change intervention for inner-city high school youth. Health Psychol. 2002;21(2):177–86.

Hochbaum GM. Public Participation in Medical Screening Programs: A Socio-psychological Study. U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Public Health Service, Bureau of State Services, Division of Special Health Services, Tuberculosis Program; 1958. 32 p.

Schwarzer R. Self-efficacy in the adoption and maintenance of health behaviours: Theoretical approaches and a new model. Self-efficacy: Thought control of action. 1992;217:242.

Adams MM, Davis PG, Gill DL. A Hybrid Online Intervention for Reducing Sedentary Behavior in Obese Women. Front Public Health. 2013;1:45.

Browne JD, Boland DM, Baum JT, Ikemiya K, Harris Q, Phillips M, et al. Lifestyle modification using a wearable biometric ring and guided feedback improve sleep and exercise behaviors: A 12-month randomized, placebo-controlled study. Front Phys. 2021;1–15.

Lucas J Carr,Kristina Karvinen,Mallory Peavler,Rebecca Smith,Kayla Cangelosi. Multicomponent intervention to reduce daily sedentary time: a randomised controlled trial | BMJ Open [Internet]. 2013 [cité 13 nov 2022]. Disponible sur: https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/3/10/e003261

Mendoza JA, Baranowski T, Jaramillo S, Fesinmeyer MD, Haaland W, Thompson D, et al. Fit 5 Kids TV Reduction Program for Latino Preschoolers. Am J Prev Med mai. 2016;50(5):584–92.

Yan T, Wilber KH, Aguirre R, Trejo L. Do sedentary older adults benefit from community-based exercise? Results from the Active Start program. Gerontologist déc. 2009;49(6):847–55.

Van Hoye K, Wijtzes AI, Lefevre J, De Baere S, Boen F. Year-round effects of a four-week randomized controlled trial using different types of feedback on employees’ physical activity. BMC Public Health déc. 2018;18(1):492.

O’Dwyer MV, Fairclough SJ, Ridgers ND, Knowles ZR, Foweather L, Stratton G. Effect of a school-based active play intervention on sedentary time and physical activity in preschool children. Health Educ Res déc. 2013;28(6):931–42.

Liu JYW, Yin YH, Kor PPK, Kwan RYC, Lee PH, Chien WT, et al. Effects of an individualised exercise programme plus Behavioural Change Enhancement (BCE) strategies for managing fatigue in frail older adults: a cluster randomised controlled trial. BMC Geriatr. 2023;23(1):370.

Prestwich A, Conner MT, Lawton RJ, Ward JK, Ayres K, McEachan RR. Randomized controlled trial of collaborative implementation intentions targeting working adults’ physical activity. Health Psychol. 2012;31(4):486.

Hadgraft NT, Willenberg L, LaMontagne AD, Malkoski K, Dunstan DW, Healy GN, et al. Reducing occupational sitting: Workers’ perspectives on participation in a multi-component intervention. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2017;14(1):73.

Brakenridge CL, Fjeldsoe BS, Young DC, Winkler EAH, Dunstan DW, Straker LM, et al. Evaluating the effectiveness of organisational-level strategies with or without an activity tracker to reduce office workers’ sitting time: a cluster-randomised trial. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2016;13(1):115.

Lynch BM, Nguyen NH, Moore MM, Reeves MM, Rosenberg DE, Boyle T, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a wearable technology-based intervention for increasing moderate to vigorous physical activity and reducing sedentary behavior in breast cancer survivors: The ACTIVATE Trial. Cancer. 2019;125(16):2846–55.

Van Dyck D, Plaete J, Cardon G, Crombez G, De Bourdeaudhuij I. Effectiveness of the self-regulation eHealth intervention ‘MyPlan1. 0.’on physical activity levels of recently retired Belgian adults: a randomized controlled trial. Health Educ Res. 2016;31(5):653–64.

Cocker KD, Bourdeaudhuij ID, Cardon G, Vandelanotte C. The Effectiveness of a Web-Based Computer-Tailored Intervention on Workplace Sitting: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Med Int Res. 2016;18(5):e5266.

Seghers J, Van Hoecke AS, Schotte A, Opdenacker J, Boen F. The added value of a brief self-efficacy coaching on the effectiveness of a 12-week physical activity program. J Phys Act Health janv. 2014;11(1):18–29.

Van Dantzig S, Geleijnse G, Halteren A. Towards a persuasive mobile application to reduce sedentary behavior. Personal and ubiquitous computing. 1 janv. 2011;17:1237–46.

van Nimwegen M, Speelman AD, Overeem S, van de Warrenburg BP, Smulders K, Dontje ML, et al. Promotion of physical activity and fitness in sedentary patients with Parkinson’s disease: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2013;346:f576.

Plotnikoff RC, Karunamuni N, Courneya KS, Sigal RJ, Johnson JA, Johnson ST. The Alberta Diabetes and Physical Activity Trial (ADAPT): a randomized trial evaluating theory-based interventions to increase physical activity in adults with type 2 diabetes. Ann Behav Med. 2013;45(1):45–56.

Ashe MC, Winters M, Hoppmann CA, Dawes MG, Gardiner PA, Giangregorio LM, et al. “Not just another walking program”: Everyday Activity Supports You (EASY) model—a randomized pilot study for a parallel randomized controlled trial. Pilot and feasibility studies. 2015;1(1):1–12.

Alsaleh E. Is a combination of individual consultations, text message reminders and interaction with a Facebook page more effective than educational sessions for encouraging university students to increase their physical activity levels? Front Public Health. 2023;11:1098953.

Alsaleh E, Windle R, Blake H. Behavioural intervention to increase physical activity in adults with coronary heart disease in Jordan. BMC Public Health déc. 2016;16(1):643.

Shamizadeh T, Jahangiry L, Sarbakhsh P, Ponnet K. Social cognitive theory-based intervention to promote physical activity among prediabetic rural people: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Trials déc. 2019;20(1):98.

Mahmoudi K, Taghipoor A, Tehrani H, Niat HZ, Vahedian-Shahroodi M. Stages of behavior change for physical activity in airport staff: a quasi-experimental study. Invest Educ Enferm févr. 2020;38(1):e02.

Balducci S, Sacchetti M, Haxhi J, Orlando G, Zanuso S, Cardelli P, et al. The Italian Diabetes and Exercise Study 2 (IDES-2): a long-term behavioral intervention for adoption and maintenance of a physically active lifestyle. Trials. 2015;16:569.

Ismail T, Al TD. Design and Evaluation of a Just-in-Time Adaptive Intervention (JITAI) to Reduce Sedentary Behavior at Work: Experimental Study. JMIR Formative Research. 2022;6(1): e34309.

Videira-Silva A, Hetherington-Rauth M, Sardinha LB, Fonseca H. The effect of a physical activity consultation in the management of adolescent excess weight: Results from a non-randomized controlled trial. Clin Obes déc. 2021;11(6): e12484.

Corella C, Zaragoza J, Julián JA, Rodríguez-Ontiveros VH, Medrano CT, Plaza I, et al. Improving physical activity levels and psychological variables on university students in the contemplation stage. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(22):4368.

Krebs S, Wurst R, Göhner W, Fuchs R. Effects of a workplace physical activity intervention on cognitive determinants of physical activity: a randomized controlled trial. Psychology & Health. 2021;36(6):629–48.

Yeom HA, Fleury J. A Motivational Physical Activity Intervention for Improving Mobility in Older Korean Americans. West J Nurs Res juill. 2014;36(6):713–31.

Lucas J Carr,Kristina Karvinen,Mallory Peavler,Rebecca Smith,Kayla Cangelosi. Multicomponent intervention to reduce daily sedentary time: a randomised controlled trial \textbar BMJ Open [Internet]. 2013 [cité 13 nov 2022]. Disponible sur: https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/3/10/e003261

De Cocker K, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Cardon G, Vandelanotte C. The effectiveness of a web-based computer-tailored intervention on workplace sitting: a randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18(5):e96.

Brakenridge CL, Fjeldsoe BS, Young DC, Winkler EAH, Dunstan DW, Straker LM, et al. Organizational-Level Strategies With or Without an Activity Tracker to Reduce Office Workers’ Sitting Time: Rationale and Study Design of a Pilot Cluster-Randomized Trial. JMIR Res Protoc. 2016;5(2):e73.

Liu Y, Li Z, Li N, An H, Zhang L, Liu X, et al. Effects of passive smoking on severe nausea and vomiting of pregnancy among urban Chinese nonsmoking women. Heliyon. 2023;9(4):e15294.

Black N, Mullan B, Sharpe L. Computer-delivered interventions for reducing alcohol consumption: meta-analysis and meta-regression using behaviour change techniques and theory. Health Psychol Rev sept. 2016;10(3):341–57.

Hobby J, Crowley J, Barnes K, Mitchell L, Parkinson J, Ball L. Effectiveness of interventions to improve health behaviours of health professionals: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2022;12(9):e058955.

Khodaveisi M, Azizpour B, Jadidi A, Mohammadi Y. Education based on the health belief model to improve the level of physical activity. Phys Act Nutr déc. 2021;25(4):17–23.

Heath GW, Parra DC, Sarmiento OL, Andersen LB, Owen N, Goenka S, et al. Evidence-based intervention in physical activity: lessons from around the world. Lancet. 2012;380(9838):272–81.

Prestwich A, Webb TL, Conner M. Using theory to develop and test interventions to promote changes in health behaviour: evidence, issues, and recommendations. Curr Opin Psychol. Oct2015;1(5):1–5.

Drouka A, Brikou D, Causeret C, Al Ali Al Malla N, Sibalo S, Ávila C, et al. Effectiveness of School-Based Interventions in Europe for Promoting Healthy Lifestyle Behaviors in Children. Children. 2023;10(10):1676.

Michishita R, Jiang Y, Ariyoshi D, Yoshida M, Moriyama H, Yamato H. The practice of active rest by workplace units improves personal relationships, mental health, and physical activity among workers. J Occup Health. 2017;59(2):122–30.

Rissel C, Curac N, Greenaway M, Bauman A. Physical Activity Associated with Public Transport Use—A Review and Modelling of Potential Benefits. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2012;9(7):2454–78.

Sun Y, Wang A, Yu S, Hagger MS, Chen X, Fong SSM, et al. A blended intervention to promote physical activity, health and work productivity among office employees using intervention mapping: a study protocol for a cluster-randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):994.

Erbe D, Eichert HC, Riper H, Ebert DD. Blending Face-to-Face and Internet-Based Interventions for the Treatment of Mental Disorders in Adults: Systematic Review. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19(9):e306.

Geaney F, Kelly C, Greiner BA, Harrington JM, Perry IJ, Beirne P. The effectiveness of workplace dietary modification interventions: a systematic review. Prev Med. 2013;57(5):438–47.

Gardner B. A review and analysis of the use of ‘habit’ in understanding, predicting and influencing health-related behaviour. Health Psychol Rev. 2015;9(3):277–95.

MacDonald B, Gibson AM, Janssen X, Kirk A. A mixed methods evaluation of a digital intervention to improve sedentary behaviour across multiple workplace settings. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(12):4538.

Bauman AE, Sallis JF, Dzewaltowski DA, Owen N. Toward a better understanding of the influences on physical activity: the role of determinants, correlates, causal variables, mediators, moderators, and confounders. Am J Prev Med août. 2002;23(2 Suppl):5–14.

Lambert EV, Kolbe-Alexander T, Adlakha D, Oyeyemi A, Anokye NK, Goenka S, et al. Making the case for ‘physical activity security’: the 2020 WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour from a Global South perspective. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54(24):1447–8.

Jones M, Defever E, Letsinger A, Steele J, Mackintosh KA. A mixed-studies systematic review and meta-analysis of school-based interventions to promote physical activity and/or reduce sedentary time in children. J Sport Health Sci janv. 2020;9(1):3–17.

Azevedo LB, van Sluijs EMF, Moore HJ, Hesketh K. Determinants of change in accelerometer-assessed sedentary behaviour in children 0 to 6 years of age: A systematic review. Obes Rev. Oct2019;20(10):1441–64.

Trost SG, Owen N, Bauman AE, Sallis JF, Brown W. Correlates of adults’ participation in physical activity: review and update. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002;34(12):1996–2001.

Lindner H, Menzies D, Kelly J, Taylor S, Shearer M. Coaching for behaviour change in chronic disease: a review of the literature and the implications for coaching as a self-management intervention. Aust J Prim Health. 2003;9(3):177–85.

Timm A, Kragelund Nielsen K, Joenck L, Husted Jensen N, Jensen DM, Norgaard O, et al. Strategies to promote health behaviors in parents with small children-A systematic review and realist synthesis of behavioral interventions. Obes Rev janv. 2022;23(1): e13359.

Black N, Johnston M, Michie S, Hartmann-Boyce J, West R, Viechtbauer W, et al. Behaviour change techniques associated with smoking cessation in intervention and comparator groups of randomized controlled trials: a systematic review and meta-regression. Addiction. 2020;115(11):2008–20.

Wright C, Barnett A, Campbell KL, Kelly JT, Hamilton K. Behaviour change theories and techniques used to inform nutrition interventions for adults undergoing bariatric surgery: A systematic review. Nutr Diet févr. 2022;79(1):110–28.

Hailey V, Rojas-Garcia A, Kassianos AP. A systematic review of behaviour change techniques used in interventions to increase physical activity among breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer mars. 2022;29(2):193–208.

Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, Abraham C, Francis J, Hardeman W, et al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med août. 2013;46(1):81–95.

Pawson R, Tilley N. An introduction to scientific realist evaluation. Evaluation for the 21st century: A handbook. 1997;1997:405‑18.

Ragin CC. Qualitative comparative analysis using fuzzy sets (fsQCA). Configurational comparative methods: Qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) and related techniques. 2009;87–122.

Mayne J. Contribution analysis: An approach to exploring cause and effect. mai 2008 [cité 28 févr 2024]; Disponible sur: https://hdl.handle.net/10568/70124

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H. E. K: PhD candidate, conceptualization, screening, data extraction, formal analysis, writing–original draft preparation, visualization. Z.B, ORCID: 0000–0002-0115-682X; PhD supervisor, contributed to the conceptualization, building of the search strategy, title and abstract screening, methodological support, revisions of different drafts and supervision. SV B, ORCID: 0000–0003-2074–0359 critically revised the final version of the manuscript. A K, PhD supervisor, critically revised the latest version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

El Kirat, H., van Belle, S., Khattabi, A. et al. Behavioral change interventions, theories, and techniques to reduce physical inactivity and sedentary behavior in the general population: a scoping review. BMC Public Health 24, 2099 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-19600-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-19600-9