Abstract

Introduction

Head lice infestation remains a persistent public health concern among primary school children in resource-limited settings, affecting their well-being and academic performance. Despite previous studies, there is no consistent evidence on the prevalence and factors associated with head lice infestation. This study aimed to determine the prevalence and factors related to head lice infestation among primary school children in low and middle-income countries.

Methods

This review was conducted by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses 2020 guidelines. Relevant electronic databases, including PubMed, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, Science Direct, AJOL, and Google Scholar, were used to retrieve articles. The study included only published articles written in English languages between December 01, 2014 to January 31, 2024 for studies reporting the prevalence of head lice infestation or associated factors among primary school children in low- and middle-income countries. This review has been registered on PROSPERO with Prospero registration number CRD42024506959. The heterogeneity of the data was evaluated using the I2 statistic. A meta-analysis was conducted using STATA 17 software, with a 95% confidence interval. Publication bias was evaluated using funnel plots and statistical tests, such as Egger’s and Beggs’s tests, to identify publication biases in the included studies. Meta-regression was also carried out to assess the source of publication of publication bias.

Results

The review included 39 studies involving 105,383 primary school children. The pooled prevalence of head lice infestation among primary school children in low- and middle-income countries was 19.96% (95% CI; 13.97, 25.95). This review also found out that being a girl was 3.71 times (AOR = 3.71; 95% CI: 1.22–11.26) more likely to have head lice infestation as compared to boys, while children with a previous history of infestation were 4.51 times (AOR = 4.51; 95% CI: 2.31–8.83) more likely to have head lice infestation as compared to their counterparts.

Conclusion

The overall prevalence of head lice infestation among primary school children in low- and middle-income countries was found to be high. Female gender, children who had a previous history of infestation, and family size were significant predictors of head lice infestation. As a result, policymakers and program administrators should focus on the identified determinants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lice have been living off of humans as parasites for thousands of years and vary depending on where they are located on the host’s body [1]. There are three types of sucking lice that commonly infest humans: the head louse, known scientifically as Pediculus humanus capitis, the body louse, also known as Pediculus humanus corporis, and the pubic louse, often referred to as the “crab” louse or Pthirus pubis [2]. Body lice transmit bacterial diseases such as epidemic typhus, trench fever, and relapsing fever to humans [1, 3, 4]. Children are more commonly affected by head lice, while body lice infestations are more frequently found in homeless shelters and migrant camps [5].

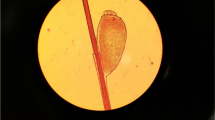

Pediculus humanus capitis is a common parasite that causes head lice infestation [6]. Head lice are small, wingless insects that feed on human blood and reside on the scalp. They are about 2 mm to 4 mm in length and have six legs [7]. It is primarily transmitted when people have close contact with each other, specifically through their hair [8, 9]. Children who are infested with head lice typically have fewer than 20 mature lice and often have less than 10. These lice can live for 3 to 4 weeks if not treated [10, 11]. Head lice thrive near the scalp as it offers them nourishment, heat, protection, and hydration [10]. It feeds on blood every 3 to 6 h by injecting saliva. After mating, the female louse can lay five or six eggs per day for 30 days, attaching them to the hair near the scalp [11]. After 9 to 10 days, the eggs hatch and turn into nymphs, which then molt multiple times within the next 9 to 15 days to reach the stage of adult head lice [12]. The hatched empty eggshells remain on the hair but are not a source of infestation. The female adult has a lifespan of around one month and lays around 300 eggs [13]. These eggs are deposited at the bottom of hair strands [14]. Nymphs and adult head lice can survive for only 1 to 2 days away from the human host [15].

The diagnosis of Pediculus humanus capitis involves identifying adult lice, nymphs, or eggs on the hair or scalp of the affected person [16]. The eggs are oval-shaped and typically yellow or white, with an average size of 0.8 mm by 0.3 mm [17]. At the end of the egg, there is a vault-like structure called the operculum [18]. Most people do not experience severe symptoms, some may suffer from itching, which can disrupt sleep and concentration. Excessive scratching can also lead to skin infections and swollen lymph nodes [19]. In addition, it can cause psychological and social issues, as well as academic difficulties in children [20].

Head lice are common and easily spread infestations that often affect school-aged children [21]. Different prevalence’s of head lice infestation have been documented in children globally, including 67.5% in Ethiopia [22], 26.6% in Jordan [23], and 23.2% in Thailand [24]. It remains a persistent public health concern among primary school children in low and middle-income countries (LMICs), significantly impacting the well-being and academic performance of this vulnerable population [25].

Head lice infestation is a common and persistent health issue among primary school children in low and middle-income countries (LMICs). Despite several studies conducted in low- and middle-income countries, there is no consistent evidence regarding the prevalence of head lice infestation and its associated factors The existing literature on the prevalence of head lice infestation in primary school children within LMICs is fragmented and often lacks comprehensive data [26]. However, there is a dearth of consolidated evidence regarding the various determinants such as socio-economic status, hygiene practices, educational settings, and access to healthcare services that contribute to the prevalence of head lice among primary school children in LMICs [27].

Therefore, this study aimed to determine the overall prevalence of head lice infestation and associated factors in low- and middle-income countries through a systematic review and meta-analysis. The purpose of this research is to gain a thorough understanding of the prevalence of head lice infestation among primary school children in low- and middle-income countries, as well as the factors that contribute to it. By examining and analyzing existing literature, this study aims to provide valuable information that can be used to develop effective public health policies and interventions.

Methods and materials

Search strategy

This systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines. A systematic search was conducted across major electronic databases, including PubMed, Web of Science, Science Direct, Cochrane Library, Google Scholar, and direct Google were used to search articles. A combination of MeSH terms and keywords related to head lice infestation, prevalence, associated factors, and primary school children in LMICs was used to identify relevant studies.

The search used a mix of Medical Subject Heading terms and words found in titles, abstracts, and full texts. The language structure for PubMed look was as follows: (“Pediculus humanus capitis” OR “Pediculus capitis” OR “Pediculi” OR “Pediculosis capitis” OR “head louse infestation” OR “head lice infestation” OR “head louse” OR (head AND mite) OR “head lice” OR (head AND lice) OR “skin disorder” OR “skin disease”) AND (“primary school student” OR “primary school” OR “school-aged children” OR “elementary school student” OR “school children” OR “school child”) AND 2014/12/01: 2024/02/31. The study protocol for this systematic review and metanalysis has been registered in the PROSPERO database under the registration number CRD42024506959.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

Cross-sectional studies published in peer-reviewed journals between December 01, 2014 to January 31, 2024 were included. Only studies conducted in low and middle-income countries focused on primary school children were considered.

Exclusion criteria

Studies with insufficient data, those not meeting quality assessment criteria, and non-original research articles (e.g., reviews, editorials) were excluded. Additionally, qualitative studies and studies that used experimental, cohort, and case-control study designs were excluded. Moreover, articles that were not fully accessible were excluded after attempting to contact the authors via email at least twice.

Study selection

Three independent reviewers (AMD, ETF, LWL) conducted the initial screening based on titles and abstracts for full-text review eligibility. Relevant data, including prevalence rates, associated factors, study design, sample size, and geographical location, were systematically extracted using a standardized data extraction form.

Quality assessment

The data quality was assessed using Joanna Briggs Institute’s (JBI’s) critical appraisal checklist for those included studies. The methodological quality of the included studies was assessed by three reviewers (NGW, MGM, MH) using standardized tools appropriate for cross-sectional studies, considering aspects such as study design, sample size, and reporting quality. The risk of bias within individual studies was evaluated, and potential biases were considered during data synthesis. This methodological approach aimed to provide a rigorous and transparent process for synthesizing evidence on the prevalence of head lice infestation and associated factors among primary school children in low and middle-income countries. Whenever necessary, another reviewer (TED) was involved and any discrepancy was resolved through discussion and consensus. Those studies with scores of 5 or more in JBI criteria were considered to have good quality and were included in the review [28].

Operational definition

In the fiscal year 2024, low-income economies are defined as those with a Gross National Income (GNI) per person of $1,135 or less. Lower middle-income economies have a GNI per person between $1,136 and $4,465. Upper middle-income economies have a GNI per person between $4,466 and $13,845, and high-income economies have a GNI per person of $13,846 or more [29]. In this review, we classified countries with low and lower-middle incomes as low-income countries and those with upper middle incomes as middle-income countries for the purpose of the study.

Data synthesis

Data were managed using reference management software, and rigorous procedures were followed to ensure accuracy and consistency. The results of the systematic review and meta-analysis were reported by PRISMA guidelines. Random-effects meta-analysis was performed using Stata 17 statistical software because heterogeneity I² statistics among studies was above 50% indicating substantial heterogeneity. Subgroup analyses were conducted based on geographical regions to explore potential sources of heterogeneity. Publication bias was evaluated using funnel plots and statistical tests, such as Egger’s and Begg’s tests, to identify potential biases in the included studies. Meta-regression was also carried out to explore and assess the potential sources of heterogeneity and publication bias.

Results

Selection of eligible studies

This systematic review and meta-analysis have been reported by the PRISMA 2020 statements. Initially, 1261 articles related to head lice infestation and/or associated factors were found. Of these, 583 duplicates and 510 articles by title and abstract were removed. After a thorough review, 87 articles were deemed irrelevant and excluded from the analysis. Ultimately, 39 articles were found to be suitable for the review and were included in the analysis (Fig. 1).

Characteristics of included studies

A total of 39 studies with a total sample of 103,902 primary school children were included in this systematic review and meta-analysis. All the studies in this review were conducted using a cross-sectional study design and were published between December 01, 2014 to January 31, 2024. Among the 39 studies included, 27 were carried out in the Middle East and North Africa [30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55]. Out of the total number of studies, 33 included both male and female participants [31,32,33,34, 36,37,38,39,40, 43,44,45, 47,48,49,50,51, 53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68] while 6 studies were among female primary school children [30, 35, 41, 42, 46, 52]. The prevalence of head lice infestation ranges from 0.58% in Côte d’Ivoire [47] to 67.3% in Iran [42] among included studies (Table 1).

Pooled prevalence of head lice infestation

The pooled prevalence of head lice infestation among primary school children in low- and middle-income countries was found to be 19.96% (95% CI; 13.97, 25.95) (Fig. 2).

Subgroup analysis

Subgroup analysis was carried out based on geographical regions. Accordingly, the prevalence of head lice infestation among primary school children was found to be 24.30% (95% CI: 14.91– 33.69) in middle-income countries whereas it was 18.03% (95% CI: 10.48–25.59) in low-income countries (Fig. 3).

Factors associated with head lice infestation among primary school children

Gender, previous history of infestation and family size were found to be statistically significant factors associated with head lice infestation.

Gender

Based on 5 included studies [53, 58, 59, 61, 66], the odds of head lice infestation among girls was 3.71 (AOR = 3.71; 95% CI; 1.22, 11.26) times higher as compared to boys (Fig. 4).

Previous history of head lice infestation

Based on 5 included studies [46, 47, 52, 53, 59], children who had a previous history of head lice infestation were 2.51(AOR = 2.51: 95% CI; 2.31, 8.83) times more likely to have head lice infestation as compared to children who had no previous history of infestation (Fig. 5).

Family size

Based on two included studies conducted in Iran found that the number of family members is significantly associated with the likelihood of children having head lice infestation. Children from larger families, with 4 or more members, were more likely to have head lice compared to children from smaller families with 3 members [46, 50].

Publication bias assessment and sensitivity analysis

The researchers checked for publication bias by visually inspecting a funnel plot, as well as using statistical tests. Accordingly, Both Egger’s and Beggs tests indicated the presence of publication bias in the pooled prevalence of head lice infestation among primary school children (Eggers test; P value = 0.001 and Beggs test; P value = 0.01) and the funnel plot was asymmetrical (Fig. 6). Moreover, meta-regression was performed to identify the source of heterogeneity by considering publication year, sample size, income category, and study population. None of the variables displayed a significant source of variation as shown below (Table 2).

Sensitivity analysis

The result of sensitivity analyses revealed that none of the studies had a significant influence on the pooled prevalence of headlice infestation (Fig. 7).

Discussion

Primary school children, typically between the ages of 6 and 12 years, are at the highest risk of getting head lice [69]. Despite efforts made to decrease the occurrence of head lice infestation among primary school children, it is still estimated that 19% of school children worldwide are affected [70]. This review aimed to assess the overall prevalence and factors contributing to head lice infestation among primary school children.

Based on this systematic review and meta-analysis, the pooled prevalence of head lice infestation among primary school children in low and middle-income countries was found to be 19.96% (95% CI; 13.97, 25.95). This finding was comparable to a previous similar study conducted in worldwide prevalence of 19% [70], 20.4% in Southern Jordan [71], and 15.1% in Thailand [72]. However, the current finding of this study was higher than the previous systematic review conducted in Iran, which reported a percentage of 7.2% [73], 2.1% in Korea [74], and 2.01 in Poland [75]. It was lower as compared to 26.6% in Jordan [76], 44.3% in Norway [77], 49.35% in Brazil [78], 34.7% in Estonia [79]. This difference might be due to socioeconomic conditions, cultural practices, access to healthcare, and hygiene standards of respondents in the study area [80,81,82].

This systematic review and meta-analysis also revealed that being female gender and having a previous history of headlice infestation had a statistically significant association with head lice infestation. Females were found to be significantly more likely to have head lice infestation compared to males, with a 3.71 times higher likelihood. This aligns with a previous global analysis that found girls were infested 2.5 times more often than boys [70]. This finding was also consistent with a study conducted in Turkey which revealed that girls were 3.1 times more likely to have head lice infestation than boys [83].

A previous similar study conducted in Kuwait also revealed that a significant infestation rate was found in girls (50.4%) in comparison to boys (37.5%) [84]. A study conducted in Saudi Arabia also confirmed that girls have a higher rate of lice infestation [85]. Another study conducted in Greece found that girls are more likely than boys to have pediculosis capitis [86]. The possible explanation for this could be due possibly because their long hair provides a suitable environment for lice survival and reproduction while boys are less susceptible to lice infestation as their hair is regularly cut, which helps remove lice eggs and control the problem [77]. Another reason could be that girls tend to have closer contact in small gatherings due to gender-related behavioral differences [87].

This review also found out that the history of children who had a previous history of infestation was 4.51 times more likely to have a head lice infestation. This finding was also consistent with a study conducted in Thailand which states that having a history of head lice infestations were 3.99 times more likely to have head lice infestation [72]. This implies that children who have had head lice before are more likely to get infested again because they are more likely to come into contact with lice in places where close interaction is common, like schools or daycares. Another possible explanation is that a previous head lice infestation was not treated properly, some lice or eggs may have survived and caused a new infestation. children and their caregivers may not have taken enough precautions to prevent reinfestation, such as avoiding close contact or regularly checking for lice. Additionally, sharing personal items like combs or hats can also contribute to the spread of lice among children who have had previous infestations.

Consequently, this systematic review and meta-analysis also revealed that the number of family members is significantly associated with the likelihood of children having head lice infestation. Children from larger families, consisting of 4 or more members, have a higher chance of experiencing head lice infestation compared to children from smaller families with only 3 members. This finding is supported by another study conducted in Spain [88]. This implies that the likelihood of head lice infestation increases when there is another infected member in the household, and having other children in the same living space also increases the likelihood of infestation, especially among children from larger families compared to those from smaller families [86, 89,90,91].

Limitation of study

The systematic review and meta-analysis followed the Prospero 2020 guideline but did not include studies published in languages other than English. Additionally, only articles published in peer-reviewed journals from December 01, 2014 to January 31, 2024 were included.

Conclusion

The overall prevalence of head lice infestation among primary school children was found to be high in low and middle-income countries. Females gender, children who had a previous history of infestation and larger family size were more likely to have head lice infestation. A comprehensive approach is needed to tackle the high occurrence of head lice infestation among primary school children in low and middle-income nations. Efficient and lasting strategies need to be created to reduce the prevalence of head lice infestation in primary school children, with particular attention given to girls and children who have previously experienced head lice infestations.

Data availability

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplemental information.

Abbreviations

- AOR:

-

Adjusted odds ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- GNI:

-

Gross national income

- LMIC:

-

Low- and Middle-Income Countries

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses

References

Light JE, Toups MA, Reed DL. What’s in a name: the taxonomic status of human head and body lice. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2008;47(3):1203–16.

Pratt HD, Smith J. Arthropods of public health importance1988.

Raoult D, Birtles RJ, Montoya M, Perez E, Tissot-Dupont H, Roux V, et al. Survey of three bacterial louse-associated diseases among rural andean communities in Peru: prevalence of epidemic typhus, trench fever, and relapsing fever. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29(2):434–6.

Bonilla DL, Kabeya H, Henn J, Kramer VL, Kosoy MY. Bartonella quintana in body lice and head lice from homeless persons, San Francisco, California, USA. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2009;15(6):912.

Gratz NG. Emerging and resurging vector-borne diseases. Ann Rev Entomol. 1999;44(1):51–75.

Galassi FG, Fronza G, Toloza AC, Picollo MI, González-Audino P. Response of Pediculus humanus capitis (Phthiraptera: Pediculidae) to volatiles of whole and individual components of the human scalp. J Med Entomol. 2018;55(3):527–33.

Roberts RJ. Head lice. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(21):1645–50.

Frankowski BL, Weiner LB, Health CS. Diseases CoI. Head lice Pediatr. 2002;110(3):638–43.

Speare R, Cahill C, Thomas G. Head lice on pillows, and strategies to make a small risk even less. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42(8):626–9.

Meinking TL, Infestations. Curr Probl Dermatol. 1999;11(3):73–118.

Jones KN, English JC. Review of common therapeutic options in the United States for the treatment of pediculosis capitis. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36(11):1355–61.

LICE TOH. Head lice infestations: A clinical update. 2008.

Lehane M, Lehane M. The blood-sucking insect groups. Biology Blood-Sucking Insects. 1991:193–247.

Amanzougaghene N, Fenollar F, Raoult D, Mediannikov O. Where are we with human lice? A review of the current state of knowledge. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2020;9:474.

Burkhart CN. Fomite transmission with head lice: a continuing controversy. Lancet. 2003;361(9352):99–100.

Álvarez-Fernández BE, Valero MA, Nogueda-Torres B, Morales-Suárez-Varela MM. Embryonic Development of Pediculus humanus capitis: morphological update and proposal of New External markers for the differentiation between early, medium, and Late Eggs. Acta Parasitol. 2023;68(2):334–43.

Laguna MF, Risau-Gusman S. Of lice and math: using models to understand and control populations of head lice. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(7):e21848.

Burkhart C, Burkhart C, Gunning W, Arbogast J. Scanning electron microscopy of human head louse (Anoplura: Pediculidae) egg and its clinical ramifications. J Med Entomol. 1999;36(4):454–6.

Mumcuoglu KY, Klaus S, Kafka D, Teiler M, Miller J. Clinical observations related to head lice infestation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25(2):248–51.

Doroodgar A, Sadr F, Sayyah M, Doroodgar M, Tashakkor Z, Doroodgar M. Prevalence and associated factors of head lice infestation among primary schoolchildren in city of Aran and Bidgol (Esfahan Province, Iran), 2008. Payesh (Health Monitor). 2011;10(4):439–47.

Gratz NG, Organization WH. Human lice: Their prevalence, control and resistance to insecticides: A review 1985–1997. 1997.

Dagne H, Biya AA, Tirfie A, Yallew WW, Dagnew B. Prevalence of pediculosis capitis and associated factors among schoolchildren in Woreta town, northwest Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes. 2019;12:1–6.

Al Bashtawy M, Hasna F. Pediculosis capitis among primary-school children in Mafraq Governorate, Jordan. EMHJ-Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal, 18 (1), 43–48, 2012. 2012.

Rassami W, Soonwera M. Epidemiology of pediculosis capitis among schoolchildren in the eastern area of Bangkok, Thailand. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2012;2(11):901–4.

Elson L, Wiese S, Feldmeier H, Fillinger U. Prevalence, intensity and risk factors of tungiasis in Kilifi County, Kenya II: results from a school-based observational study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13(5):e0007326.

Vahabi A, Shemshad K, Sayyadi M, Biglarian A, Vahabi B, Sayyad S, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of Pediculus (humanus) capitis (Anoplura: Pediculidae), in primary schools in Sanandaj City, Kurdistan Province, Iran. Trop Biomed. 2012;29(2):207–11.

Abbasi E, Daliri S, Yazdani Z, Mohseni S, Mohammadyan G, Hosseini SNS et al. Evaluation of resistance of human head lice to pyrethroid insecticides: a meta-analysis study. Heliyon. 2023;9(6).

Masresha SA, Alen GD, Kidie AA, Dessie AA, Dejene TMJSR. First line antiretroviral treatment failure and its association with drug substitution and sex among children in Ethiopia: systematic review and meta-analysis. 2022;12(1):18294.

World Bank Country. and Lending Groups. 2024.

Haghi FM, Golchin M, Yousefi M, Hosseini M, Parsi B. Prevalence of pediculosis and associated risk factors in the girls primary school in Azadshahr City, Golestan Province, 2012–2013. Iran J Health Sci. 2014;2(2):63–8.

Raheem AE, El Sherbiny TA, Elgameel NA, El-Sayed A, Moustafa GA, Shahen N. Epidemiological comparative study of pediculosis capitis among primary school children in Fayoum and Minofiya governorates, Egypt. J Community Health. 2015;40(2):222–6.

Dehghanzadeh R, Asghari-Jafarabadi M, Salimian S, Asl Hashemi A, Khayatzadeh S. Impact of family ownerships, individual hygiene, and residential environments on the prevalence of pediculosis capitis among schoolchildren in urban and rural areas of northwest of Iran. Parasitol Res. 2015;114(11):4295–303.

El Magrabi NM, El Houfey AA, Mahmoud SR. Screening for prevalence and associated risk factors of head lice among primary school student in Assiut City. Adv Environ Biology. 2015;9(8):87–95.

Abbas B, Fatemeh N, Mahdi S, Zahra DE, Effat A, Faranak F, CLINICAL AND EPIDEMIOLOGICAL STUDY OF PEDICULOSIS, PEDICULUS HUMANUS CAPITIC (HEAD LICE INFESTATION). IN PRIMARY SCHOOL PUPILS, SAVOJBOLAGH COUNTY, ALBORZ PROVINCE, IRAN. Eur J Biomedical. 2016;3(3):60–4.

Alborzi M, Shekarriz-Foumani R. The prevalence of Pediculus capitis among primary schools of Shahriar County, Tehran province, Iran, 2014. Novelty Biomed. 2016;4(1):24–7.

Kassiri H, Esteghali E. Prevalence rate and risk factors of pediculus capitis among primary school children in Iran. Archives Pediatr Infect Dis. 2016;4(1).

Kassiri H, Gatifi A. The frequency of head lice, health practices and its associated factors in primary schools in Khorramshahr, Iran. Health Scope. 2016;5(4).

Nazari M, Goudarztalejerdi R, Payman MA. Pediculosis capitis among primary and middle school children in Asadabad, Iran: an epidemiological study. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2016;6(4):367–70.

El-Sayed MM, Toama MA, Abdelshafy AS, Esawy AM, El-Naggar SA. Prevalence of pediculosis capitis among primary school students at Sharkia Governorate by using dermoscopy. Egypt J Dermatology Venerology. 2017;37(2):33–42.

Majidi S, Farahmandfard MA, Solhjoo K, Mosallanezhad H, Arjomand M. The prevalence of pediculosis capitis and its associated risk factors in primary school students in Jahrom, 2016. Pars J Med Sci. 2017;15:50–6.

Sanei-Dehkordi A, Soleimani-Ahmadi M, Zare M, Madani A, Jamshidzadeh A. Head Lice Infestation (Pediculosis) and associated factors among primary school girls in Sirik County, Southern Iran. Int J Pediatr. 2017;5(12):6301–9.

Soleimani-Ahmadi M, Jaberhashemi SA, Zare M, Sanei-Dehkordi A. Prevalence of head lice infestation and pediculicidal effect of permethrine shampoo in primary school girls in a low-income area in southeast of Iran. BMC Dermatol. 2017;17(1):1–6.

Khamaiseh A. Head Lice among Governmental Primary School Students in Southern Jordan: prevalence and risk factors. J Global Infect Dis. 2018;10(1):11–5.

Nategh A, Eslam M-A, Davoud A, Roghayeh S, Akbar G, Hassan B, et al. Prevalence of head lice infestation (pediculosis capitis) among primary school students in the Meshkin Shahr of Ardabil province. Am J Pediatr. 2018;4(4):94–9.

Nejati J, Keyhani A, Kareshk AT, Mahmoudvand H, Saghafipour A, Khoraminasab M, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of pediculosis in primary school children in South West of Iran. Iran J Public Health. 2018;47(12):1923.

Saghafipour A, Zahraei-Ramazani A, Vatandoost H, Mozaffari E, Rezaei F, KaramiJooshin M. Prevalence and risk factors associated with head louse (Pediculus humanus capitis) among primary school girls in Qom province, Central Iran. Int J Pediatr. 2018;6(4):7553–62.

Ghofleh Maramazi H, Sharififard M, Jahanifard E, Maraghi E, Mahmoodi Sourestani M, Saki Malehi A, et al. Pediculosis humanus capitis prevalence as a health problem in girl’s elementary schools, southwest of Iran (2017–2018). J Res Health Sci. 2019;19(2):e00446.

Basha MA, El Moselhy HM, El Mowafy WS. Pediculosis among school children in a primary school in Millij Village, Menoufia Governorate. Menoufia Med J. 2020;33(1):248.

Haama AA. Epidemiology and molecular aspect of pediculosis among primary school children in Sulaimani Province Kurdistan-Iraq. Kurdistan J Appl Res. 2020:1–9.

Norouzi R, Jafari S, Meshkati H, Amiri FB, Siyadatpanah A. Prevalence of Pediculus capitis Infestation among Primary School students in East Azerbaijan Province, Iran (2018–2019). Med Lab J. 2021;15(1).

Zahirnia A, Aminpoor MA, Nasirian H. Impact and trend of factors affecting the prevalence of head lice (Pediculus capitis) infestation in primary school students. Chulalongkorn Med J. 2021;65(4):359–68.

Bekri G, Shaghaghi A. Prevalence of Pediculus humanus capitis and associated risk factors among elementary school-aged girls in Paveh, West Iran. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2022;16(9):1506–11.

Hama-Karim YH, Azize PM, Ali SI, Ezzaddin SA. Epidemiological Study of Pediculosis among primary School children in Sulaimani Governorate, Kurdistan Region of Iraq. J Arthropod Borne Dis. 2022;16(1):72–83.

Sepehri M, Jafari Z. Prevalence and Associated factors of Head Lice (pediculosis capitis) among primary School students in Varzaqan Villages, Northwest of Iran. Zahedan J Res Med Sci. 2022;24(1).

Abd RG. Study of the prevalence of head lice infestation among school students and its effect on some blood tests, and a statement of the effect of five types of treatment on eliminating lice in Salah Al-Din Governorate. J Adv Educ Sci. 2023;3(2):69–74.

Karimah A, Hidayah RMN, Dahlan A. Prevalence and predisposing factors of pediculosis capitis on elementary school students at Jatinangor. Althea Med J. 2016;3(2):254–8.

Khidhir KN, Mahmood CK, Ali WK. Prevalence of infestation with head lice Pediculus humanus capitis (De Geer) in primary schoolchildren in the centre of Erbil city, Kurdistan region, Iraq. Pakistan Entomol. 2017;39(2):1–4.

Tohit NFM, Rampal L, Mun-Sann L. Prevalence and predictors of pediculosis capitis among primary school children in Hulu Langat, Selangor. Med J Malaysia. 2017;72(1):12–7.

Moradiasl E, Habibzadeh S, Rafinejad J, Abazari M, Ahari SS, Saghafipour A, et al. Risk factors Associated with Head lice (Pediculosis) infestation among Elementary School students in Meshkinshahr County, North West of Iran. Int J Pediatr (Mashhad). 2018;6(3):7383–92.

Amelia L, Anwar C, Wardiansah W. Association of sociodemographic, knowledge, attitude and practice with Pediculosis capitis. Bioscientia Medicina: Journal of Biomedicine and Translational Research. 2019;3(1):51–63.

Djohan V, Angora K, Miezan S, Bédia A, Konaté A, Vanga-Bosson A et al. Parasite Epidemiol Control. 2020.

Ibrahim HMS, Mohamed HOA. Prevalence and associated factors of Pediculus humanus capitis infestation among primary schoolchildren in Sebha, Libya. J Pure Appl Sci. 2020;19(5):132–8.

Lintong F. Prevalence and risk factors for Head Lice Infestation at Kaima Sunday school children, Kauditan District, and North Minahasa Regency. Sch J App Med Sci. 2021;10:1581–3.

Ftattet NH, Gloos FA. Head lice (Pediculus humanus capitis) infestation and the role of health education in limiting its spread among children at primary-school in Misurata, Libya. J Med Sci. 2022;17(1):21–6.

Rasheed FM, Al-Nasiri FS. Investigation of prevalence of infestation with head lice and some factors affecting on them in infected people in Kirkuk city, Iraq. Tikrit J Pure Sci. 2022;26(3):1–6.

Souza AB, Morais PC, Dorea J, Fonseca ABM, Nakashima FT, Correa LL, et al. Pediculosis knowledge among schoolchildren parents and its relation with head lice prevalence. Acad Bras Cienc. 2022;94(2):e20210337.

Ozden O, Timur I, Acma HE, Simsekli D, Gulerman B, Kurt O. Assessment of the prevalence of Head Lice Infestation and Parents’ attitudes towards its management: a School-based Epidemiological Study in Istanbul, Turkiye. Turkiye Parazitol Derg. 2023;47(2):112–6.

Bamaga OA, Alharazi T, Al-Abd N. Prevalence and risk factors of Pediculus capitis among primary schools children in Al-Mukalla city, Hadhramout Governorate, Yemen: a school-based cross-sectional study. Hadhramout Univ J Nat Appl Sci. 2021;18(2).

Burgess I. Head lice–developing a practical approach. Practitioner. 1998;242(1583):126–9.

Hatam-Nahavandi K, Ahmadpour E, Pashazadeh F, Dezhkam A, Zarean M, Rafiei-Sefiddashti R, et al. Pediculosis capitis among school-age students worldwide as an emerging public health concern: a systematic review and meta-analysis of past five decades. Parasitol Res. 2020;119:3125–43.

Khamaiseh AM. Head lice among governmental primary school students in southern Jordan: prevalence and risk factors. J Global Infect Dis. 2018;10(1):11.

Ruankham W, Winyangkul P, Bunchu N. Prevalence and factors of head lice infestation among primary school students in Northern Thailand. Asian Pac J Trop Disease. 2016;6(10):778–82.

Akbari M, Sheikhi S, Rafinejad J, Akbari MR, Pakzad I, Abdi F, et al. Prevalence of Pediculosis among Primary School-aged students in Iran: an updated comprehensive systematic review and Meta-analysis. J Med Entomol. 2022;59(6):1861–79.

Ryoo S, Hong S, Chang T, Shin H, Park JY, Lee J et al. Prevalence of head louse infestation among primary schoolchildren in the Republic of Korea: nationwide observation of trends in 2011–2019. Parasites, Hosts and Diseases. 2023;61(1):53.

Bartosik K, Zając Z, Kulisz J. Head pediculosis in schoolchildren in the eastern region of the European Union. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2015;22(4).

Mohammed A. Head lice infestation in schoolchildren and related factors in Mafraq governorate, Jordan. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51(2):168–72.

Birkemoe T, Lindstedt HH, Ottesen P, Soleng A, Næss Ø, Rukke BA. Head lice predictors and infestation dynamics among primary school children in Norway. Fam Pract. 2016;33(1):23–9.

Valero MA, Haidamak J, Santos TCO, Pruss IC, Bisson A, Santosdo Rosario C, et al. Pediculosis capitis risk factors in schoolchildren: hair thickness and hair length. Acta Trop. 2024;249:107075.

Kutman A, Parm Ü, Tamm A-L, Hüneva B, Jesin D. Estonian parents’ awareness of pediculosis and its occurrence in their children. Medicina. 2022;58(12):1773.

Davarpanah MA, Kazerouni AR, Rahmati H, Neirami RN, Bakhtiary H, Sadeghi M. The prevalence of Pediculus capitis among the middle schoolchildren in Fars Province, southern Iran. Caspian J Intern Med. 2013;4(1):607.

Lapeere H, Brochez L, Verhaeghe E, Vander Stichele RH, Remon J-P, Lambert J, et al. Efficacy of products to remove eggs of Pediculus humanus capitis (Phthiraptera: Pediculidae) from the human hair. J Med Entomol. 2014;51(2):400–7.

Kamiabi F, Nakhaei FH. Prevalence of Pediculosis capitis and determination of risk factors in primary-school children in Kerman. EMHJ-Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal, 11 (5–6), 988–992, 2005. 2005.

Karakus M, Arici A, Ozensoy Toz S, Ozbel Y. Prevalence of head lice in two socio-economically different schools in the center of Izmir City. Turk TurkiyeParazitolDerg. 2014;38:32–6.

Henedi A, Salisu S, Asem A, Alsannan B. Prevalence of head lice infestation and its associated factors among children in kindergarten and primary schools in Kuwait. Int J Appl Nat Sci. 2019;8(3):2319–4022.

AL-Megrin WA. Assessment of the prevalence of pediculosis capitis among primary school girls in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Res J Environ Sci. 2015;9(4):193.

Soultana V, Euthumia P, Antonios M, Angeliki RS. Prevalence of pediculosis capitis among schoolchildren in Greece and risk factors: a questionnaire survey. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26(6):701–5.

Friebel G, Lalanne M, Richter B, Schwardmann P, Seabright P. Gender differences in social interactions. J Econ Behav Organ. 2021;186:33–45.

Morales-Suarez-Varela M, Álvarez-Fernández BE, Peraita-Costa I, Llopis-Morales A, Valero MA. Pediculosis humanus capitis in 6–7 years old schoolchildren in Valencia, Spain. Cent Eur J Public Health. 2023;31(2):144–50.

Willems S, Lapeere H, Haedens N, Pasteels I, Naeyaert J-M, De Maeseneer J. The importance of socio-economic status and individual characteristics on the prevalence of head lice in schoolchildren. Eur J Dermatology. 2005;15(5):387–92.

Motovali-Emami M, Aflatoonian MR, Fekri A, Yazdi M. Epidemiological aspects of pediculosis capitis and treatment evaluation in primary-school children in Iran. Pakistan J Biol Sciences: PJBS. 2008;11(2):260–4.

Rukke BA, Birkemoe T, Soleng A, Lindstedt HH, Ottesen P. Head lice prevalence among households in Norway: importance of spatial variables and individual and household characteristics. Parasitology. 2011;138(10):1296–304.

Funding

No funding was provided for this research from any public, commercial, or not-for-profit organizations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AMD, MH, ETF, LWL, NGW, MGM, DE and TED developed the protocol and were involved in the design, selection of the study, data extraction, and statistical analysis. AMD, ETF, MGT, AA, ETF, NKW, and DE were involved in data extraction and quality assessment. AMD, MM, MH and TED were developing the initial drafts of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final draft of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Delie, A.M., Melese, M., Limenh, L.W. et al. Prevalence and associated factors of head lice infestation among primary school children in low- and middle-income countries: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 24, 2181 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-19712-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-19712-2